13 minute read

FROM FAIREY WITH LOVE

by All At Sea

Last month we reflected on the very beginning of the Fairey story and followed the twists and turns that led us to the 1948 Olympic regatta at Torquay and growing export success. We take up the story again as the boat builder navigated the heady days of the 1960s.

Thankfully, the austere years of the 1950s were giving way to a new decade of hope in the ‘60s and Faireys were right at the forefront of the growth in consumerism.

Advertisement

Their first venture into the world of powerboats produced an instant classic, the 23ft Fairey Huntress. Initially the design was based on the thinking of American designer Ray Hunt, who was a leader in the development of the ‘deepvee’ hull form.

Even with the combined experience of Faireys and Hunt, the first iteration of this boat as an open launch was something of a failure, as it utilised a heavy metal centreplate, similar to that on a sailing dinghy. At speed, water was forced up through the plate case under pressure and risked flooding the cockpit.

Once the plate had been dispensed with, a cabin was added and the Huntress was developed showing that the hull had amazing sea- keeping qualities.

The Name’s Fairey… From the outset there was a need for a bigger twin engined version of the boat and Fairey’s in-house designer, Alan Burnard, soon developed a second classic, the Huntsman 28, and in the first ever Cowes to Torquay powerboat race in 1961 Charles Currey nursed his boat Diesel Huntsman all the way down channel to successfully complete the course and take a number of prizes, including third overall.

The two boats received an extra media boost when they were used in the 1963 James Bond film, From Russia with Love, starring Sean Connery.

For the purposes of filming, the waters around the west coast of Scotland were pressed into service, doubling as an area of the Adriatic. With a Fairey team on board, a number of Huntress and Huntsman all played their part in the film. The rack to hold a number of extra fuel drums (which would play a big, if improbable part in Bond’s escape) were prefabricated at the Hamble yard and tested a number of times out on Southampton Water to check that they would all roll off the stern of the boat without assistance.

For the scenes in which the ‘baddies’ in their pursing boats got destroyed, the close call scenes involved large underwater sacks of petroleum jelly that could be remotely detonated, but there were some close calls and when the boats returned from Scotland, the first task was to rub down and repaint the blistered hulls. a wet ride in a seaway. Designer Alan Burnard addressed this problem with not one but two beautiful boats, the 33ft Swordsman and a stretched Huntsman 31, though the latter was an all-new hull that employed Burnard’s beautifully curved bow.

These and other newcomers would swell the Fairey range further, but Fairey had also been looking to break into new markets for commercial craft. One project was to build ships’ lifeboats with a hot-moulded hull, with considerable investment going into the construction of a new mould and the preparation

The location of the Fairey Factory made it a great marker for the mouth of the Hamble and here it is put into perspective with a hot moulded Fairey Firefly, the first boat to go into mass production at Hamble Point. Image: David Henshall for the rigorous and exhaustive tests demanded by the Board of Trade.

The new Fairey Lifeboat passed all of these with flying colours, only to find that, just as with the leisure market, shipping companies were now showing a marked preference for the low maintenance of GRP construction.

The prototype Lifeboat hull would become something of a fixture around the Hamble and the Solent as it was pressed into service as the ’workboat’ for the factory, whilst the ‘waste nothing’ mindset saw the lifeboat hull mould reused as the basis for the Fairey Fisherman motor sailor.

Until now all of the boat construction had been centred around the traditional hot moulding process, but in time Fairey would move with the times and look to start the move to GRP construction, with the resulting boats, such as the Fantôme and Spearfish, quickly being marked out as the next in line for ‘modern classic’ status.

Commercial focus Although the Fairey range from Hamble would continue to be a success, elsewhere far larger problems in other divisions would see the parent company falling into financial troubles, and in 1975 the Fairey Group ended up in Administration.

The marine arm continued, albeit with a much stronger focus on commercial craft, an area that Fairey were already active in, as their boats were in service with a number of Police Forces as fast patrol boats. Fairey powerboats were

In the end the nations of northern Europe would probably working on both sides of the come together to defeat the Barbary Pirate menace, law, as Hamble produced at least one and when an Anglo-Dutch fleet shelled Algiers ‘special’, which had a fantail exit for the thousands of slaves would finally be released. exhaust that reduced the characteristic

Image: Everett Collection/Shutterstock ‘burble’ of the twin diesels to no more than a murmur as the boat came back into the Hamble River at six knots.

What the boat was used for nobody knew, though from fuel usage plus departure and arrival back times, nighttime trips to the back of the Island seemed the logical conclusion!

Military ties The new look Faireys would also reconnect strongly with the military, though much of the work was for the export market. Breaking away from the traditional thinking of naming Fairey boats after their old aircraft, the Dagger was a military version of the stretched Swordsman 37, with a number of extra features, such as a reinforced foredeck to take a machine gun mount. With a big military trade fair scheduled for

A Modern Classic... Just like the E-Type, an icon that shares many of the same performance and aesthetic values, the Fairey powerboat, from the Huntress, through the Huntsman, Swordfish on to the Spearfish and the Fantome are today rightly considered true classics. Yet, just as with the E-Type, many of these boats hail from the 1960s and are now requiring keel up restorations and increased maintenance, yet at the same time, even with the best of modern upgrades, are still very much examples of the thinking, albeit some of the best thinking, that was available at the time. The idea, therefore, of building on the original concepts that fused ‘form and function’ in harmony, creating new boats, using state-of-the-art construction techniques, could well see boats such as the latest Spearfish 32, from builders Supermarine, at their Northshore Shipyard on Chichester Harbour, becoming a true modern classic. Following on from our historical overview of the Fairey story, here at All at Sea we have been following the All images: Andrew Wisemanexciting developments as work on the Spearfish 32 has moved from completion to on-the-water testing, and we will be reporting in more detail very soon.

Portsmouth, the boat was prepared, then taken out into the Solent for a photoshoot, only to run into problems as she returned into the Hamble River. They were met by the Harbourmaster who was adamant that armed vessels were not allowed past the Hamble Spit Buoy and that “you cannot bring that gun in here”!

In the end a temporary compromise was reached that saw the gun bundled up in wrapping, which simply made it look even more like a whaling harpoon gun!

With the markets in Africa, the Middle and Far East open for business, Fairey went even bigger with a 62ft patrol boat, the Tracker, which had the hull laid up in GRP at the Fairey site at East Cowes, for the new Fairey Marine was expanding by acquisition. Care had to be taken, with mock-up guns made on site, that could quickly be removed when in the river, as the Tracker could be even more heavily armed than the Dagger.

Aluminium calling Just as GRP had replaced wood, the commercial market was now turning increasingly towards aluminium construction, which Fairey followed with their tie-up with the Allday Aluminium Company. This brought another big success, but hardly a boat noted for its looks or charm as the 25ft Combat Support Boat was a blunt nosed workboat/tug with angular lines and a boxy wheelhouse. Hundreds were made, with yet more made under licence in the US, with the ‘CSB’ even ending up in the war zone of the Falklands.

Not the prettiest boat, the CSB was well mannered afloat and for the skillful helm, huge fun to drive as the powerful engine was connected to a ducted water jet drive. You could go from full ahead directly to full astern, at which point the boat would all but stand on its bow, though care had to be taken to not get caught playing this trick.

A less successful venture was a prototype aluminium fast landing craft, which somehow ended up with the rudder mounted centrally in the tunnel between the two main hull sponsons. On its first test afloat, it was found that it was possible to make a 180° turn within the Hamble river, as long as you were turning to starboard, it was high tide and there was no one in the way. The same exercise but with a turn to port nearly ended up proving expensive!

Far more successful was the construction of the floating bridge chain ferry that links East with West Cowes. Taking just 16 months to build and costing just over £250,000 there are many on the Island who would love to see the ‘old’ Fairey built bridge back again, given the ongoing litany of issues with the latest version.

Farewell to Fairey Sadly, despite all these successes, the global outlook was changing, with the UK in particular moving from a manufacturing to a service based economy. Fairey struggled on through the recession of the early 1980s, before the axe finally fell with the sale of the Hamble point site.

It would be remiss, though, to think of Fairey at Hamble as ‘just another boatyard’ as they were far more than that, for they were in the vanguard of the changes that would enable easy access to the water. Before the concept of the marina took off in the UK, Fairey ran the famed Boat Park, where customers’ boats were kept ashore on specially constructed trailers.

All the owner had to do was give an hour or so notice (conveniently the time it took to get to Hamble from London) and the boat would already be in the water and tied up alongside the pontoon, ready for the owner to step aboard and motor away. At the end of the weekend, boats were left back on the pontoon for the team to bring back ashore on to the trailers, ready for the following weekend.

With the ebb tide sluicing across the main slipway, to watch the Boat Park team in action was poetry in motion, but with the arrival of marinas on the river, at Port Hamble then Hamble Point, the Boat Park would soon be consigned to history, along with the rest of the amazing story of Faireys on the Hamble.

Highly desirable That should be the end of the story, but the Fairey hot moulded hulls seem to be almost bulletproof in their construction (an early test was to take a 12ft Firefly hull and bury it in the mud in the creek that ran beside the factory. After being there for a year it was taken out, hosed off and looked as good as new!).

Incredibly, despite not commanding the central space any more around the pool at the London Boat Show, the Fairey brand seems stronger now than ever. The hulls might be strong, but the topsides may not be so good (Faireys were plagued at one point by the poor quality marine ply that was used in making the superstructure).

The Fairey Powerboats, led by the Swordsman, have the looks, the rarity factor and that head turning WOW that ensures that they are more desirable than ever, with well restored examples attracting the top end of premium prices.

Those classic Fairey names would not, though, leave the Hamble quietly and without a final reminder of their presence. With the Hamble Point site sold, all vestiges of Faireys were being cleared away, with much just being dumped in skips. But, on an early morning of low water springs, the old moulds, thick with the glue of repeated mouldings, were dragged down on to Hamble Spit and set alight.

Although they burnt furiously and were soon nothing more than ashes, the smoke from the fire was seen to be drifting across the river mouth, which soon attracted the attention of an irate Harbourmaster, but when it came to delivering the reprimand, there was no one left on site to complain to.

After decades as a dominant force in naval aviation, in dinghy sailing and powerboats of all ilks, Fairey Marine was no more. If you would like to read the first part of the Fairey story, back issues of All at Sea are available to read for free at allatsea.co.uk/all-at-sea-the-paper.

JOIN THE CLUB The Fairey Owners Club welcomes new members, including owners of similar craft and model makers. There are events, a forum, Fairey information, links and much more. faireyownersclub.co.uk

CORRECTION In last month’s Fairey article we referred to a 33ft Fairey Swordfish when in fact it was the Swordsman 33. We would also like to clarify that Atalanta Clifford was not married to Sir Richard Fairey, but to his elder son - also named Richard. It was simply a coincidence that Richard married Atalanta, as the Atalanta sailing cruiser already existed and had been named after the Atalanta flying boat that Fairey built in 1923.

As Fairey started to lose ground in the powerboat scene, they were already diversifying into the world of commercial and military boats. Team Fairey out in the Solent with the Interceptor, a multi-role high speed utility landing craft and a 20m Tracker. Image: Fairey Marine

In the days before the arrival of the marina, owners could keep their boats ashore, ready to be trailered into the water at little more than an hour’s notice on the famed Fairey Marine Boat Park. Image: David Henshall Fairey Marine were not just feeding the market, in many ways they were helping create it. Other developments were happening in parallel, such as the ready availability of early generation ‘4x4s’ such as the Land Rover, so marketing that shared the connection between the two companies was an obvious move forward. Image: Currey Archives

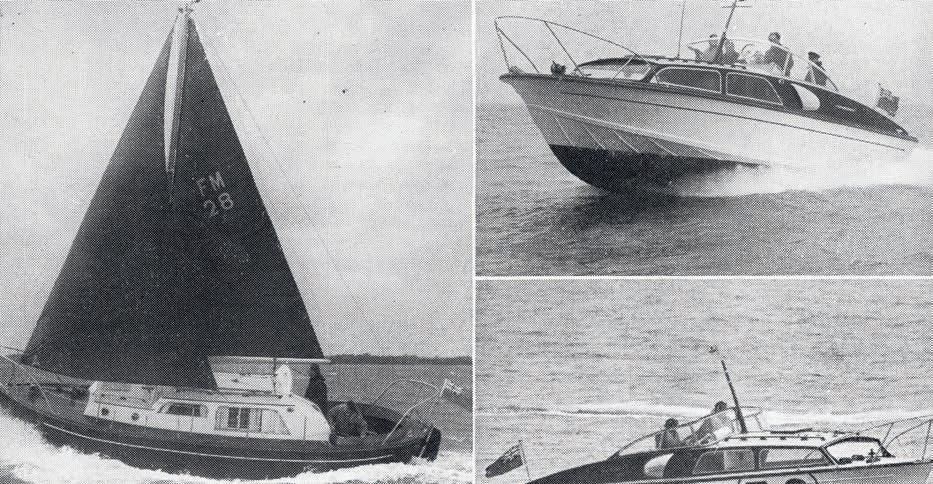

In the race to stay in the leisure powerboat market, the Fairey design team worked to come up with a range of even more attractive boats and in doing so created yet more truly classic hull forms. Image: David Henshall

Marketing photos from Fairey Marine, showing the diverse nature of their range, from powerboats to raceboats to the rugged Fairey Fisherman motor-sailor, which was based on a development of a ship’s lifeboat hull. Image: Fairey Marine The rise of Fairey Marine took place in the chill of the Cold War, when Russia was portrayed as a malign influence in books and films such as the James Bond film ‘From Russia with Love’. The climax of the film was a sea chase, with Bond and the Bond girl finally escaping in a Fairey powerboat. Image: Fairey Marine