8 minute read

20

Imaginuity

OCTOBER 5, 2019 • 8:00 PM Rachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall and Arts Center

Advertisement

OCTOBER 6, 2019 • 3:00 PM George Washington Masonic Memorial

James Ross, conductor

Rita Sloan, piano ∙ Alan Richardson, cello ∙ Nicholas Tavani, violin

PROGRAM

Prelude to Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

Wagner

Triple Concerto, Op. 56

Beethoven

Rita Sloan, piano ∙ Alan Richardson, cello ∙ Nicholas Tavani, violin

Tidbit #1

- INTERMISSION -

Lione Semiatin

Imaginary Symphony

I. William Walton: Symphony No. 1 (1st mvt.) II. Amy Beach: Gaelic Symphony (2nd mvt.) III. Ethel Smyth: “On the Cliffs of Cornwall” from The Wreckers IV. Arthur Honegger: Symphony No. 3 (3rd mvt.)

Prelude to Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Richard Wagner’s music drama Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Master Singers of Nuremberg) holds a special place in the hearts of opera lovers— particularly Germans with an inherited sense of the great old tradition of the original “Master Singers.” As the only comedy among Wagner’s later works, the opera is a heart-tugging combination of nostalgia, formality, lightheartedness and romance; it’s also a great example of the creative use of a technique developed by Wagner and used by composers to this day: the leitmotiv.

Anyone familiar with the Star Wars series of films can probably bring to mind the music heard each time Darth Vader makes an entrance, or the rebellion is spoken of, or Princess Leia appears on screen. By connecting characters and ideas to musical themes or gestures, Star Wars composer John Williams is using Wagner’s leitmotiv technique to bring cohesiveness to the story line and “lead” the viewer to understand the “motives” of the character.

The real Master Singers were at their peak in Germany around the time of the Reformation. An actual historical figure of the time, Hans Sachs, is depicted in Wagner’s comedy surrounding a singing competition. The leitmotiv heard at the opening of the Prelude depicts the formalities of the culture and its artistic expression. As the Prelude continues, we are introduced to characters and story lines through their musical signatures.

In a moment of brilliant culmination, Wagner brings back six of the opera’s most important leitmotivs simultaneously in the Prelude’s recapitulation. We hear how the harmonic, melodic and rhythmic characters of each leitmotiv, and thus each character and element of the story, relate to each other. A glorious coda brings the Prelude to a satisfying conclusion.

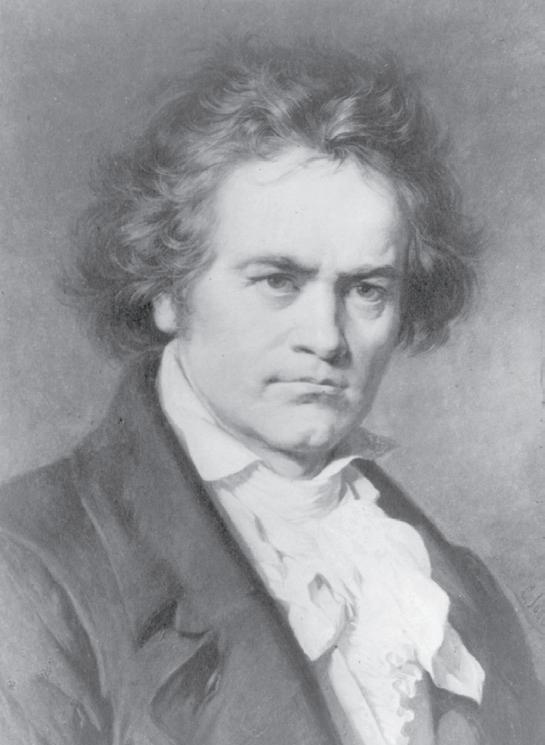

Concerto for Violin, Cello and Piano in major, Opus 56 “Triple Concerto”

Ludwig van Beethoven (c.1770-1827)

In the classic and romantic eras, composers associated certain keys, or tonal centers, with certain colors and characters. For example, Joseph Haydn’s final London Symphony is written in D major—a key in which the violins and trumpets sound especially bright and invigorating.

For his one and only concerto for multiple solo instruments, Beethoven chose C major—the same key as his Waldstein Sonata for piano, a work sharing space in Beethoven’s compositional mind in the year 1804. Both works are “pianistic” in nature, and the key of C favors the white notes of the piano, allowing certain technical effects like glissandi that would be impossible in other keys. It is also neutral in color for the three instruments, and since Beethoven seems to have had his young student and patron Archduke Rudolph in mind when he wrote the concerto, perhaps Beethoven thought it would give the less-experienced soloist a small technical advantage.

In 1804 the composer was boldly entering what we refer to as his middle period of composition. After establishing his credentials as a youthful upstart among his Viennese audiences, Beethoven began stretching familiar forms and styles, almost single-handedly launching the Romantic musical era.

The concerto’s broad, overarching first allegro movement is full of memorable melodies, introduced in the substantial orchestral introduction and picked up first by the cello, then passed among the solo instruments like a conversation. We immediately see and hear how Beethoven solves one of the trickiest technical challenges of writing

for such a diverse collection of solo instruments—balance. When the soloists are playing, the orchestra is playing with reduced forces, allowing the soloists space to become the prominent voices.

After this vigorous opening movement of symphonic scope, listeners will find respite in the second movement titled Largo. Beethoven uses the tempo indication largo rarely; in this case the quiet orchestration and slow pulse serve as background to allow the soloists to interact with each other in chamber music fashion.

The finale, teasingly brought forth by the soloists in a clever transition from the Largo, is entitled Rondo alla Pollaca, or Rondo in the style of a polonaise. A dance in 3/4 time, it has a particular “held back” feel, almost like a minuet danced in heavy boots. The soloists take turns presenting and developing the melodies, with opportunities for virtuoso fireworks and interplay. With typical Beethovenian sense of humor that would have tickled contemporaneous listeners, the composer switches into 2/4 time before a rousing coda.

Lionel Semiatin (1917-2015)

Tidbit #1

Rarely does one come across a work composed within the sounds of battle, close to the front lines. Rarer still is to find a personal connection to such a work.

U.S. Army Corporal Lionel Semiatin, father of ASO violist Gene Pohl, found a moment of respite from the fighting and movement in Normandy just days after the D-Day landings in June of 1944. He took the opportunity to jot down some musical thoughts, eventually turning his ideas into Tidbit #1. The character of the music, perhaps surprisingly, is lively and uplifting—described by ASO Music Director James Ross as “a kind of love letter to the positive spirit of the country he was missing.”

Imaginary Symphony

The Imaginary Symphony is a collection of works assembled by ASO Music Director James Ross. The first movement of William Walton’s first symphony is dark, intense and unrelenting. Full of passion, Walton seems to be struggling to work through deeply internal anxiety and agitation. This emotional tour de force is justly regarded to be among the most important British symphonic works of the 20th century.

Amy Beach’s Gaelic Symphony of 1896 was the first symphonic work of an American woman ever to be published and performed. Her husband limited her activities both as performer and composer, insisting— as would be typical for the time—that she perform her social duties befitting the wife of an important societal figure. The “Siciliana” refers to a rhythmic style in a lilting 6/8, reminiscent of the oar movements of the boatmen of Sicily. The Scottish feel of the work is never lost; in the context of Maestro Ross’s “Imaginary Symphony,” the movement provides a moment of respite after the turgid opening movement from William Walton’s symphony.

Ethel Smyth was a remarkably prolific composer. An acquaintance of Dvořák, Grieg, Tchaikovsky, Brahms and Clara Schumann, Smyth served time in prison for activities surrounding the suffragette movement in Britain in 1912. She had passionate relationships with suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst and, later in life, with Virginia Woolf. Smyth’s works were subject to criticism often unfairly aimed at her female nature. “On the Cliffs of Cornwall” is a work full of truly virtuosic writing. One hears French influence, a bit of Ralph Vaughan Williams, even Richard Strauss—but always in Smyth’s own singular voice.

19 Swiss composer Arthur Honegger spent the years of World War II trapped in occupied France. He dabbled with the French Resistance but was never caught; the Nazis did little to interfere with his life. He became profoundly depressed by the war. His Symphony No. 3 is dedicated to reflecting on the nature of this relentless, seemingly inevitable human endeavor and its pointless tragedy. The finale, Dona Nobis Pacem (Grant us peace), begins with a remarkable march evoking approaching armies; it comes to a close in quiet, peaceful reflection on lives wasted, lives lost.

Nowadays, conductors are rarely composers. But we are certainly the most personal advocates for other composer’s works. Now and then, it happens that we conductors stumble across pieces or parts of pieces that just call out for greater recognition. And now and then, we discover an inner compulsion to compose programs as freely as composers choose notes. The “Imaginary Symphony” is a fulfillment of both urges.

The four works chosen by me to contribute to this symphony are all parts of larger pieces that would be difficult to perform in full with an orchestra like our Alexandria Symphony—difficult since it is not clear how many of you would rush to attend a concert with a full half program devoted exclusively to any one of them. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be heard.

The Walton First, Honegger Third, and Amy Beach Gaelic Symphonies are all fine works in their own right, as is Ethel Smyth’s opera The Wreckers. But these chosen movements are among the finest moments of pieces that are otherwise mildly misfit for our modern concert life. The titanic power of Walton’s first movement, composed just a few years before World War II, seemed in my brain to find a fitting counter-balance in the final cataclysmic movement of Honegger’s “Liturgique” (entitled Dona Nobis Pacem), which was composed amidst the devastation directly following the end of that war.

Although written some decades earlier, the works of Amy Beach and Ethel Smyth present respectively pastoral and unsettling depictions of the potential loss (both human and environmental) of warring. By excerpting some of the strongest movements from these existing works, creating both a sort of musical grab bag and a new symphonic narrative of my own devising, I hope to shed deserved light on some composers and pieces that have lain unfairly absent from our concert halls and that may animate you to search out and discover the full works from which they come. If deemed successful advocacy, I can’t promise this will be the last “Imaginary Symphony” I create...