14 minute read

CHAPTER IV (THE VISION REALISED!!)

DRAW CLOSE, dear FRIENDS, and LISTEN (Amazed and Inspired)

To the PREVIOUSLY-UNTOLD

Advertisement

STORY of a Viibrant, Eclecctiic c grooup of ARTISTIIC GENNIUSESS, Bound togetther as a COMMUNITY of Friends and Equals in the city of BRISTOLL, E Enngland.

THE STORY SO FAR…

(ALASTAIR SHUTTLEWORTH: CREATOR & EDITOR)

…iscomplicated, beingcomprisedofmany differentprojectsandvoicesoverthe pastdecade.Asitevadesastraightforwardnarrative,thisstorywillbetoldthrough a series of ever-intertwining interviews with the characters involved. This fourth groupcanberoughlycontextualisedlikeso

This publication was created in 2017 to promote a dramatic, inspiring new moment in Bristol’s underground and avant-garde music, which – through perceived failings in the British music industry – had gone largely overlooked on the national stage.

Today, the city finds itself in altered standing. Many once-overlooked artists from these pages have carved out larger audiences for themselves. Amidst these recent breakthroughs, the industry is increasingly attentive and receptive to this city’s new music, which finds itself more regularly featured across national publications and radio. While The Bristol Germ can’t take credit for these developments, they constitute the realisation of a vision set down and preserved in its pages With this, it is time to bring this project to a close.

It has been a privilege to write on this city’s music community. I am deeply grateful to this publications’ interviewees, illustrators and stockists, as well as anyone who has ever come to, played, or worked on one of our live showcases. I especially thank the past and future readers of these four instalments, with hopes that this bizarre, bracing music brings them at least part of what it has brought me.

Our first instalment TheNobleCrusadeBegins!! ’ explored the sudden wave of projects that electrified Bristol’s musical landscape from the early 2010s. New Ground’sAcquired!!brought this exploration up to date with a wider look at the city’s emerging projects. The Nation’s Eyes Turn!! focused on this moment’s gradual attainment of wider interest One month after its publication, the UK went into lockdown at the outset of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Picking up in a much-changed landscape, The Vision Realised!! features many artists who are carving out a place for themselves beyond the city, such as Sarahsson, Ishmael Ensemble, Grove, DAMEFRISØR, Robbie & Mona, Tara Clerkin Trio, Viridian Ensemble and Fever 103. We hear from new forces in Bristol’s live scene such as Strange Brew and Illegal Data, as well as longstanding projects COIMS and ThisisDA who, amidst this change, are making their finest work

Enjoy reading, friends. Thank you for everything.

THIS ILLUSTRATED

Music

MAGAZINE Documents and Promotes this exciting new moment in underground and avant-garde music, driven by a community of artists creating world-beating records and shows, united by a fierce DIY ethic. This document is comprised of IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS with the Cast of Characters driving this epoch, ORIGINAL ARTWORK by the city’s best illustrators, and FOUR MANIFESTOS outlining iniquities which influenced this magazine ENJOY, ABSORB, BE ENLIGHTENED.

LIST OF F IMMMORRTALS (INDEX)

Sarahsson

Ishmael Ensemble

Grove

(Manifesto 13: The Present)

DAMEFRISØR

Tara Clerkin Trio

Fever 103

(Manifesto 14: Selfish Mechanics)

Strange Brew

COIMS

Robbie & Mona

(Manifeesto 15: Change)

Viridian Ensemble

ThisisDA

Illegal Data

(Manifesto 16: Conclusions)

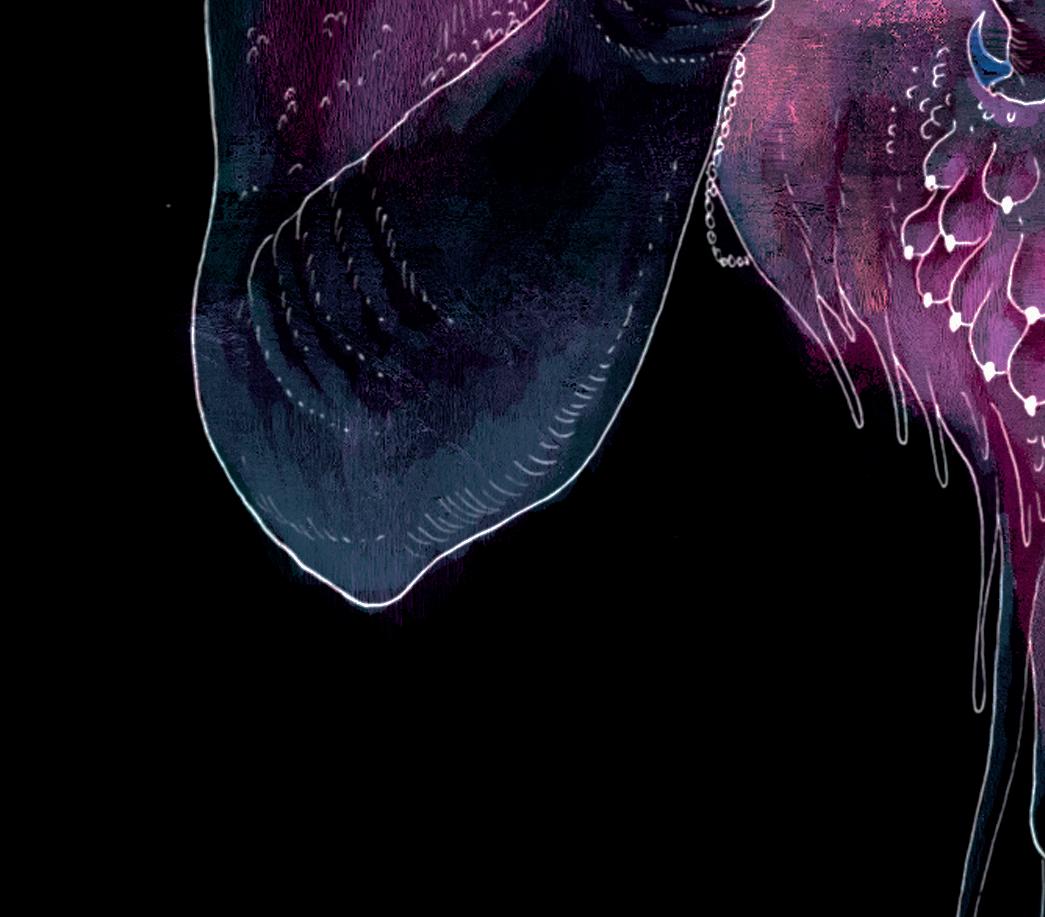

COMPOSER & PRODUCER SARAHSSON

Combining classical music, industrial electronica and hand-built instruments, Sarahsson’s wildly unpredictable debut album The Horgenaith has marked her out amongst the city’s most thrilling new experimentalists Released via Illegal Data, the album explores femininity, the natural world and bodily transformation via ankle-breaking changes in mood and texture How do you see the album’s constant state of musical transformation as relating to its themes?

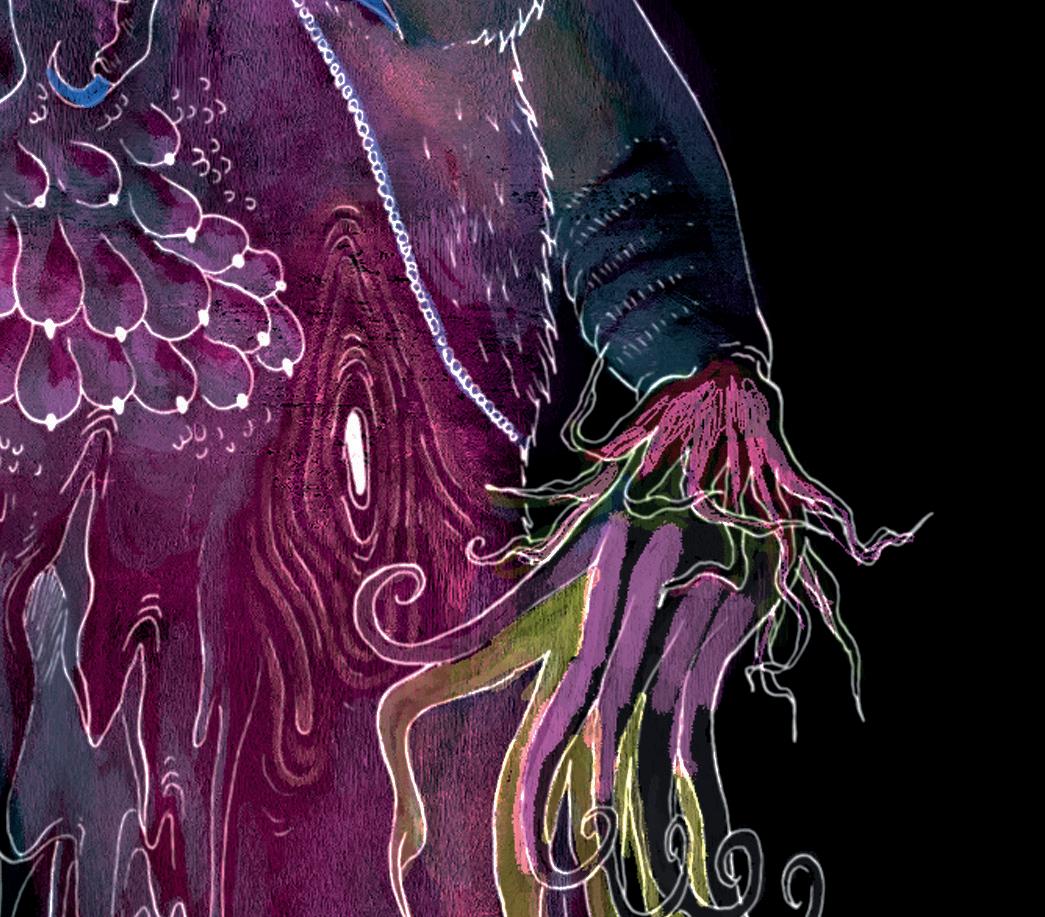

Sarahsson: A fickle nature is something assigned, often accusatively, to women. There’s the expectation to embody as many opposing female archetypes as possible, whilst masculinity remains an incorruptible monolith. There’s also archaic ideas of femininity as some distant concept that can’t be understood, and of women as closer to nature. I was very inspired by mythological stories from The Mabinogion and Homer’s Odyssey,where femininity constantly flits from demureness to murderous jealousy. Blodeuwedd was fabricated from flowers by a wizard (again linking women to the natural world), with the purpose of being the wife to a cursed man who she later cheats on and tries to kill. I’m enjoying toying with these notions and digesting them.

The relationship between the body and nature is a very comforting metaphor for me. I imagine my recent fourth wisdom tooth as a tectonic plate shuffling all the others around, my hair as foliage, and the redistribution of body fat from taking oestrogen as a cave system being carved out by water flow. It’s not just a metaphor though: bodies are environments made up of many disparate organisms, and we make up a larger body as organisms ourselves.

I first saw you perform at The Bristol Germ’s stage for Dot To Dot Festival 2019, alongside Bad Tracking, Lynks, Organchrist and others What do you recall of that set, and how would you describe your shows?

S: It was still quite new to me then! I remember I was surrendering wholly to this unbridled energy for the first time, which often meant that I didn’t remember large portions of performances, and frequently injured myself. I remember deep-throating a rose, playing a track from Barbie As The Princess & The Pauper (which is still a favourite), and how striking the other performances were too! I think people really responded to the chaotic nature of those shows, and I’m glad I let myself do it: it was a necessary outlet, and I also know some of my limits now.

Perhaps in response to that fullthrottle style, I’ve broadened the energetic cadence of the shows a bit. I’m starting to really enjoy the more ambient, music-focused concerts, but still adore the violence of hammering a blood-filled piano to pieces. The nature is always theatrical: whether that be in subtle hand movements and expressions, or peeling latex skin off and making out with a strobe light. It’s fun how different they end up being each time, from lack of rehearsals.

The Horgenaith ’ s opening track ‘Ancient Dildo Intro’ moves from a gritty industrial soundscape (strewn with animalistic sucking sounds) into a gorgeous piano prelude This might be seen to gesture towards the album’s counterpoised tropes of soaring melodic pieces and dark, visceral electronica How do you see these two sides of the record as relating to each other, in an album concerned with the human body?

S: For me there is a significant feeling of balance in each track. Within the clashing tonalities, scraping and blasting, there is harmony in how the gentle and the intense interact and complement each other. I use the word ‘beautiful’ a lot to counterweight ‘grotesque’ simply because they’re signifiers of certain imagery, but truthfully they’re one and the same.

This is sort of the nature of opposites in a non-binary, Kybalion-esque way: "Like and unlike are the same; opposites are identical in nature, but different in degree; extremes meet; all truths are but half-truths; all paradoxes may be reconciled.” Rot and dirt can inspire disgust, but mould and soil evoke fertility and can be incredibly colourful. I’ve always been fascinated by that dynamic, especially within the body. I sometimes pretend it all stems from not being passed through a stone circle as a baby (unlike my siblings), which led to all sorts of illnesses, infections and infestations over the years: witnessing parts of myself decay and become a home to something else. Understanding my body as a machinic eco-system helped me rationalise that, whilst fostering a small obsession with the four humours.

These wet, animalistic sounds of sucking, rustling and heavy breathing loom large in the album – most clearly in ‘Perennium (Reprise)’ How did you go about recording them, and how do you see them as serving the album thematically?

S: I really just spent a week going full ‘messy foley artist’. I used courgettes and gourds to get those fleshy thuds, snapped pieces of wood to mimic bones twisting, and then tomatoes and a waterlogged sponge for the really juicy bits. They serve different purposes at different times I think: of course they echo the themes in various ways, but primarily sound effects are a super direct way to tell a story through sound.

A very early title for the album was Throat Centre , partially inspired by the chakra point associated with truthful expression. I was also very interested in how an open throat looks a little like a phalaenopsis orchid, and what the sexual connotations of that relationship could be. ‘Ancient Dildo Intro’ was kind of an extension of that, teamed with lyrics straight from a Wikipedia article about early human sex toys, in which the throat snaps.

‘Perennium’ also follows this device of flora-fauna hybridisation, the word itself being a portmanteau of perennial (describing a plant that lives for several growing seasons) and perineum (the skin between the genitals and anus). It tells a story about my relationship with the piano, trying to escape boundaries and reach a freer, more improvisational style. Soon I am sucked back into the institutional structure of classical music, and forced to destroy the piano which, in turn, destroys me. The melody is from a much earlier track of the same name about feeling ungrateful and ashamed after a breakup, so it’s already heavy with these uncomfortable, guilty emotions that I wanted to acknowledge in order to move on. It made sense to me that the piano should be filled with blood and viscera (since we had become each other), so I wanted to make it extremely gory and increasingly shocking until our self-destruction tears us from reality and all that’s left is the booming of the abyss.

This invites reflection on the album’s broader interest in gore and body horror This is most evident in penultimate track ‘Swallow’, which features a poem by Buoys Buoys Buoys describing someone being swallowed whole. What can you tell me about the role of horror in The Horgenaith?

S: I scared easily as a kid, but was also obsessed with that feeling. A lot of the films and TV shows I watched growing up were fantasies from the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s (Willow,She,IndianaJonesetc.). They all included at least one horrifying practicaleffects transformation scene, which I’d watch over and over.

I also used to get really bad sleep paralysis when I was young, with recurring nightmares and an astoundingly vivid ‘dream universe’ that I can still remember in great detail: being slowly turned into an embryo, being consumed by mouths in the floor and cushions, my insides liquifying and pouring out of holes in my skin. I’m obviously now a huge fan of David Cronenberg and John Carpenter, as well as of artists like Junji Ito, and within a lot of their most grotesque and twisted works is the fear of losing oneself or succumbing to something else inside you – it’s pure destrudo . There’s a wonderful stage direction for the final shot of Ari Aster’s Midsommar when Dani finally smiles, which says “it is horrible and it is beautiful.” I had a similar feeling at the end of SaintMaudtoo. They both remind me of the ‘biblically accurate angels’ phenomenon: rejecting their typical depiction as Botticelli-esque humanoids and embracing their original descriptions as huge, terrifying masses of eyes and wings.

The poem Buoys Buoys Buoys wrote actually references several stories involving a whale or large fish swallowing someone (Jonah and the Whale, Moby Dick , James Bartley) and the original inspiration for the collaboration came from a fascination with vorarephilia: sexual fantasies of swallowing someone or being swallowed. After the chaos of battling with the monster and being thrown around in a maelstrom, the protagonist finds comfort being held in a giant, benevolent stomach before his inevitable dissolution. I’ve almost made a companion of fear, or faced it with curiosity and sublimated it… almost.

The album employs an instrument called a Daxophone, which you created with the assistance of fellow Bristol artist Jemima Coulter What can you tell me about the creation of this instrument, and its place in The Horgenaith?

S: The inventor Hans Reichel had left instructions on how to build a Daxophone. I discovered his music through Oneohtrix Point Never’s track ‘No Good’ and became instantly fixated. Saffron Records’ ‘Springboard’ scheme awarded me some funding to realise the album, and I’d always wanted to build my own instruments so started looking for hardwood dealers in the UK - I also dreamed of replicating the Baschet brothers’ voice leaf but it proved too ambitious for now.

I was interested in the parallels between carving this curved form – each millimetre of difference affecting the resulting sound in totally unpredictable ways – and starting on hormone replacement therapy with an idea of what’s supposed to happen but taking a bit of a leap of faith into the unknown.

It took several weeks of visits to Jemima, each time filling the air with a rich, reddish-brown cloud, and the accompanying meaty smell of the snakewood’s Australian home.

Occasionally we’d vice one of the wooden tongues and scrape something along one edge to test the tonality I did eventually bring in a violin bow, but forgot rosin so ended up using some very sappy pine offcuts to provide some friction on the hairs. It’s hard to say that it sounded nice once it was finished, but there was a real ‘what have I created’ moment in the music studio with Jemima.

It’s essentially a wooden strip held onto a hollow block. As you bow the strip it vibrates and is picked up by two piezo mics inside the block, and then you can alter the pitch by dampening the tongue with a solid parabolic block. If you add a hole in the tongue then dampen it, this creates a formant filter effect: it sounds like a really breathy voice. I was mainly excited to see how extreme and intense a sound I could create, but now I want to discover its tender side.

The album is principally instrumental –employing instrumentation from your background in orchestral music (piano, tenor horn) alongside synthesised sounds of your own creation. However, there is also an important choral element to your work, which in ‘Tonsil Pearls’ supports the album’s sole lead performance in your natural, undistorted voice. What can you tell me about this song lyrically, and the role of your voice in The Horgenaith?

S: It’s interesting that you describe the album as instrumental. I suppose truthfully it is, but I’d always considered it a lyrical album - though perhaps only in contrast to my existing releases. I consider ‘Tonsil Pearls’ my first attempt at writing something like a pop song, but after eight months of production the structure had become too fragile to fit all the lyrics I’d written. A lot of the words are consequently hidden within textures as whispered percussion or polyphonic vocal atmospheres.

In classic trans fashion, it’s a song about transformation – realising that the woes we suffer belong to our oppressors (and even to them are hand-me-downs), and that we are all infinite wellsprings of energy.

I think the reason I describe The Horgenaith as a lyrical album is because there’s a ‘voice’ in nearly every element of it: each live instrument and synthesised sound have their own vocabularies, which become conduits for emotion.

The Slovenian philosopher Mladen Dolar talks about the voice tying language to the body: forming the intersection of the two, but not belonging to either. It doesn’t fit the body, so it escapes – leaving the body behind. With this in mind, a lot of the processes behind making the album were experiments in what I consider my body, language and my voice. In the metaphor of body as earth, does my voice flow atop and off the edge of me, or is it mined from within me? Instruments, software and even field recordings can become extensions, bypassing a primitive tongue, through which the soul is translated.

One of The Horgenaith ’ s most memorable moments comes in closing track ‘Cladonia Hymnal’ – the triumphant closing melody is first heard on what sounds like a child’s wind-up music box, before being repeated in a towering synth outro What can you tell me about the idea behind this ‘music box’ section?

S: I’ve talked before about this incredibly specific feeling that I’m trying to reach in some of my music, and ‘Cladonia Hymnal’ is probably the closest effort so far: this bittersweet, smiling-through-tears moment you get at the end of a hyperemotional film, or after a dream that felt like a whole lifetime. It’s like saying “goodbye” and “thank you” and “ sorry ” and “I love you” all at the same time.

The music box I used is one I’ve had since I was born, that plays ‘The Yellow Submarine’ I arranged each note into a sound font to play my own melodies with. In the background there are also ghosts of older tracks of mine which fit the same chord sequence, including ‘Old Comforts Which No Longer Serve Me’ and one of the soundtracks I made for Neith Nyer’s runway shows: like a climactic Hollywood finale, where old characters reappear to send off the protagonist.

Prior to this, there was only one other comparable Sarahsson release – the one-off track ‘Old Comforts Which No Longer Serve Me’ from Illegal Data’s second compilation in 2021 This gestured towards some of the musical ideas in The Horgenaith : there are dance sensibilities, a choral section, and a synth outro similar to that of ‘Cladonia Hymnal’. What can you tell me about that one-off track, and how you see The Horgenaithas relating to it?

S: As the title proclaims, I was trying to move away from things which had protected me at one point but had begun to stagnate, such as making myself appear more masculine, and shutting down at the slightest hint of stress. I was particularly trying to break this recurring pattern of overthinking and paralysis when faced with creative opportunity, so it was a real purging of many things. It made sense to use ideas and techniques that I’d been ruminating on, but couldn’t let go of: things which were satisfying but maybe felt lazy to me at the time, just to get them out of my system so I could move on to something else.

I guess the spell worked slightly differently than I expected, because I ended up finding more room to explore inside those corners, and it provided a taste of where I would be heading more than a vestige of what I was leaving behind.

The Horgenaith was released via Bristol label and club-night Illegal Data, whose shows you have performed at previously. What can you tell me about Illegal Data, and the community around them?

S: The boys! I’m so grateful for the friendship we’ve formed. They both put all their energy and generosity and knowledge into everything they do, and I admire them both a lot. They’ve got some incredible artists on the roster I thoroughly recommend listening to You can tell they’re just so enthusiastic about good music. They started putting on events in 2018, and have since kept a very stable theme of ‘anything that could be considered club music’ – be that footwork, witch house, mákina, grime or ethereal trance

The first time we met, they’d invited me to join a line-up with aggressive hard techno, emo rave, hip-hop and hardcore. It proved Bristol as somewhere uniquely open: it seemed wild to me that there was a community of people who specifically enjoyed hearing lots of very different music in one night, but it’s a real thing here. That melting-pot attitude is what leads to the hybridisation that’s kept Bristol one of the most sonically interesting places for decades.

I understand you are originally from Exeter, then lived in London for a time before settling in Bristol What can you tell me about your musical journey prior to moving to this city, and in what ways do you think Sarahsson has been influenced by the artistic community in Bristol?

S: Exeter provided me with a fairly traditional musical upbringing: I had piano lessons from a young age, joined a children’s orchestra, then was introduced to dance music through the free party scene London provided a view into queer nightlife, but was mainly a social endeavour: I had no time to make music working 50-hour weeks to survive. Bristol brought those two together, and magnified the gaps between them. I was lucky that my parents’ taste was broad and fairly interesting too I will always remember long car journeys with Tom Waits’ Rain Dogs playing, or pretending to vomit while my Dad blasted Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie . That really sparked my curiosity in music.

It really is such a wonderful feeling to be a part of this community. Everyone is doing such different things and we’re all cheerleading each other because it’s all so exciting. You can feel that everyone is invested in this energy: always fascinated, always discovering, and it’s also really playful. It can become easy to take music too seriously, especially in certain genres, so it’s very refreshing to be surrounded by people who are at once sincere and silly. That environment is completely necessary for Sarahsson’s existence.