5 minute read

BICYCLES IN FRONTIER ALASKA

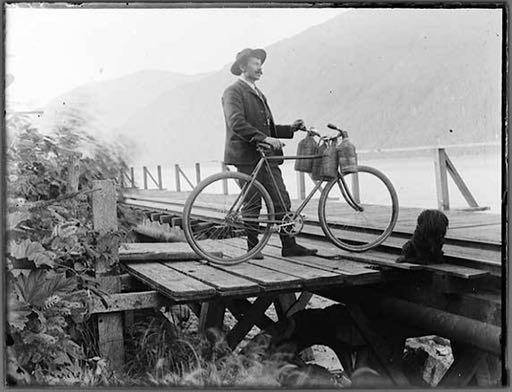

Man with a bicycle on the dock at Yakutat, Alaska, circa 1920.

[Fhoki Kayamori Photographs, Alaska State Library Historical Collections. ASL-P55-293]

Bicycles in Frontier Alaska

Advertisement

(overheard by Ed Jesson, near Circle City, 1900)

In 1896 Edward Jesson came to Alaska to prospect for gold, and made his first locations at Hope and Sunrise on Turnagain Arm, on the northern shore of the Kenai Peninsula. When news of the big strike at Dawson City arrived, he pulled up his stakes and headed for Seattle, outfitted himself properly for the adventure ahead, and went to the new diggings via Skagway, White Pass, and down the Yukon River. Things didn’t pan out in the gold fields, and by 1899 he was running a store, post office, and wood-cutting camp known as Star, where the 70-Mile River empties into the Yukon, about 120 miles downriver from Dawson. Then the stampede to Nome began. All that winter Ed Jesson watched the parade of men and dogs struggling down the river on their way to Nome, and by March he had decided there had to be an easier way to travel. He opted to go by bicycle, and bought one from the A.C. store in Dawson for $150 in gold.

Jesson kept a detailed diary of his month-long ride, which ended when he arrived in Nome on March 29, 1900, and it would prove to be one of the most fascinating personal accounts from the Gold Rush era (available to read online, see Resources page 48).

Jesson wrote of his departure, “The day I left Dawson, March 2, 1900, was clear and crisp, 30 degrees below zero. I was dressed in a flannel shirt, heavy fleece-lined overalls, a heavy mackinaw coat, a drill parka, two pairs of heavy woolen socks and felt high-top shoes, a fur cap that I pulled down over my ears, a fur nosepiece, plus fur gauntlet gloves. “On the handlebars of the bicycle I strapped a large fur robe. Fastened to the springs, back of the seat, was a canvas sack containing a heavy shirt, socks, underwear, a diary in waterproof covering, pencils and several blocks of sulfur matches. In my pockets I carried a penknife and a watch.”

In 1900 the Seattle newspaper Argus noted the increasing sales of bicycles to the Klondike prospectors. “It is not generally known, perhaps that the Klondike trade, which has done so much for Seattle, extends to the bicycle business. Local dealers report that the success of cyclists on the trail has caused this branch of their trade to change from a mere experiment to a steady growing demand. No less than a dozen wheels have been sold by dealers in this city for Dawson in the past two weeks. It is said that in March the trail is in such condition as to make travelling by wheel practical. Scarcely a steamer sails for the North that does not carry bicycles. The Dawson Bicycle Club will doubtless be heard from soon.”

Part of the reason for the growing popularity of bicycles in the north country was explained by author John Firth in Yukon Sport: An Illustrated Encyclopedia: “Keeping a team of sled dogs alive in the frozen north required an enormous expenditure of time, resources and money. While folks thought Ed Jesson was crazy, especially since he owned a good dog team, he countered that he didn’t have to cook dog food for the bicycle at night, and on especially good days he could cover one hundred miles: three or four times farther than a dogsled.”

The bicyclists followed the tracks packed down by the sled dog teams, their narrow tires fitting perfectly into the grooves cut by the sled runners. Ed Jesson wrote, “The sleds had scraped most of the snow off the [icy trail], and left it in fine condition for the wheel as the rubber tire stuck to this trail very well and all I had to do was look out for the icy cracks, which were very numerous.”

Another prospector, Max Hirschberg, left Dawson to travel down the Yukon River to Nome at almost the same time as Edward Jesson. He celebrated his 20th birthday on the long ride, arriving in Nome in May, more than a month after Jesson. Hirschberg nearly died during his journey when he broke through the ice while crossing a river and almost drowned. Crossing the frozen Norton Sound near the end of his journey, his bicycle chain broke, so he ingeniously positioned a stick inside the back of his coat, forming a sail of sorts, and let the brisk wind push him across the ice of the Sound.

Hauling mail and freight over Valdez summit.

[A. J. Johnson photo. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsc-01569]

In 1906 John A. Clark crossed Thompson Pass with a bicycle on the way to Fairbanks from Valdez, and he wryly wrote in his diary: “The steepness of the trail, and the freshly fallen and wind-blown snow made it impossible to attempt to ride the bicycles, so all we could do was take them on our backs and start up in the face of the gale… A man with a bicycle on his back is not only classed as a pedestrian, but as a fool.”

A Signal Corps messenger (?) at Donnelly Telegraph Station, ca. 1915.

[Alaska State Library, U.S. Military Telegraph Stations In Alaska, ca. 1910-1925. ASL-PCA-314]

After problems on the Delta River, John Clark, who would later become a Fairbanks attorney specializing in mining and corporation law, gave up his bicycle and continued his trip via stage. He wrote a manuscript of his journey titled 'From Valdez to Fairbanks in 1906 by Bicycle, Blizzard, and Strategy,' stored in the library of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, and excerpted in Herbert L. Heller’s book, 'Sourdough Sagas: The Journals, Memoirs, Tales and Recollections of the Earliest Alaska Gold Miners, 1883-1923.' New York: New York World Publishing, 1967).

Wild journeys over mountain passes and down the Yukon River were exciting, but they were hardly the only use of bicycles in early Alaska. Many old vintage photographs include bicycles, whether they are being ridden, pushed along, or just leaning against trees, poles, buildings, and other stationary objects. Bicycles were a popular method of transportation in frontier Alaska, for both summer and winter use.

Postcard of a group at the waterfront, Tanana, 1912-1914. Note the bicycle.

[Univ. of AK Fairbanks, Rivenburg Album, UAF-1994-70-395]

In an article for the Alaska Historical Society, historian Terrence Cole wrote, “Though some people think of the bicycle as a toy, like a skateboard or a Frisbee, in the 1890s the two-wheeler was the technological wonder of the day. In magazines there were serious scientific articles about why bicycles would replace the horse, and miiltary experts like General A. W. Greely, the Arctic explorer for whom Fort Greely is named, thought that in the future, high-speed Army communications would be carried long distances by men on bicycles.”

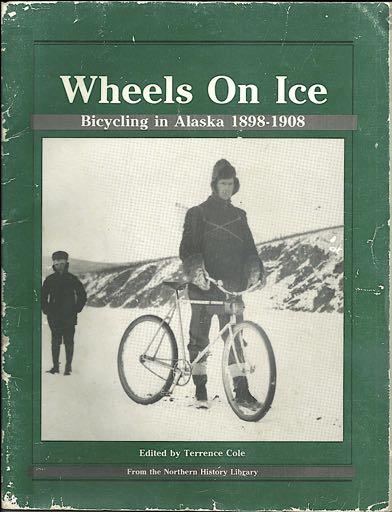

Terrence Cole wrote 'Wheels on Ice: Bicycling in Alaska 1898-1908' (Alaska Northwest Pub. Co., 1985), a slim 64-page collection of five stories of bicycle trips in Alaska, including Jesson’s account of his trip down the Yukon River to Nome. ~•~

Out of print, but available in many libraries, see Resources, page 48.