5 minute read

Riverfall and other works

PAINTING & LANDSCAPE: EXTENDING THE DIALOGUE

CLEA H NOTAR

Advertisement

As was so pointedly illustrated by much of the performance work and ideas of Joseph Beuys, contemporary culture has become characterised by the mediation of science and technology to such an extent that we have had to invent for ourselves or discover in other cultures, rituals with which we can re-experience nature; by which we can free it from ideology. This return to an integrated state constitutes a hope against the threat posed to nature by a Western culture of hyper-consumerism and hyper-fragmentation. In this context the role of the landscape artist has become more urgently political just as the reappropriation of our environment as an objectified and reified image has become a politicised act. The history of Western landscape painting is littered with the representation of nature as a backdrop for portraits of power; the land having been reduced to a sigh of the power of patriarchal man to tame and possess. Images which acknowledge a plurality of possible origins, representations and states of reception, are images which imply integration and equilibrium, ideas which stand opposed to hierarchy and property ownership. Alan Rankle’s painting is concerned with the ‘disruption of tradition rather than its abandonment’. It is born from a studied practice and an empathetic and receptive immersion with his subject matter; our natural environment. At the age of sixteen, as a student at Rochdale College, Alan Rankle developed an early interest in Chinese painting and poetry. He also encountered and was inspired by the ideas of John Cage, through a guest lecturer at Rochdale, a Black Mountain student. At Goldsmiths’ College Rankle wrote his BA thesis on the Origin and Development of Early Chinese Landscape Art. At this time landscape work was being translated into acts of land art and earth work by Christo, Robert Smithson and Richard Long amongst others. A commitment to landscape painting would have been highly unfashionable at the time – the iconoclastic art stance within the iconoclastic art world. Rankle remains active in both the tradition of landscape painting and the burgeoning movement of installation and performance, all the while continuing to explore the ideas and culture of both the East and West.

It was during a six year period in Yorkshire, where Rankle produced the Endless River Landscapes, a series which were his first major group of works to relate the precepts of Chinese painting to the Western naturalistic tradition of landscape painting. It was here, too, that Rankle first concentrated solely on the medium of painting. Using oils, pastels and watercolours, he created small scale studies which were painted, en plein air; simultaneously continuing and commenting on the tradition of the landscape painter literally painting in the field.

The image is one which fits a mythopeic vision of the Romantic nineteenth century landscape painter out in the great – bourgeois – expanse of the English countryside, however it is also one which, when viewed with a disruptive ironic humour, comments on that particular ‘way of seeing’ the artist and the art’s subject matter. For this stage in Rankle’s work was also a deferential nod towards and practice of, landscape painting, which Western innovators in colour, form and approach, such as Whistler, Monet and Hitchens (the latter with whose work and ideas Rankle shows a certain affinity) practised as part of a search, not only to express a voice particular to their time, but also to discover a more dialogic approach to landscape painting, such as the one inherent in Chinese painting.

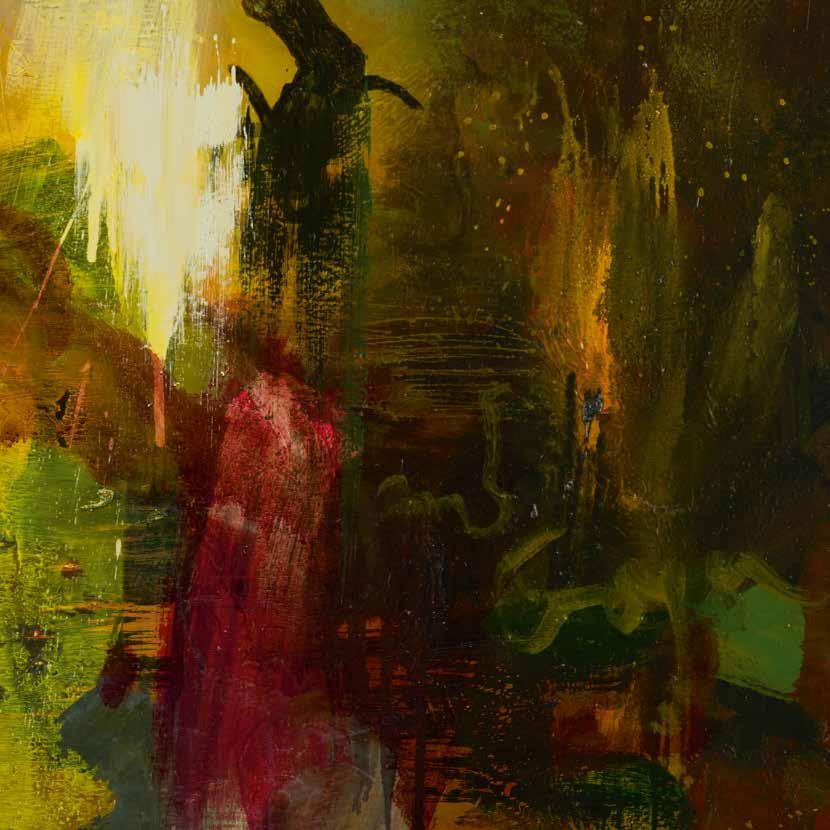

Dialogue is the key to Rankle’s work. His paintings – and his ongoing involvement and commitment to art which is available to and active within the community – encourage the expansion of views, not to mystify or solidify knowledge. If his work draws a veil, it draws a visible one in order to call attention to itself; a veil of gold leaf on copper or dripping paint; of glazed and scumbled layers over heavily wrought textures, deliberately offsetting the conventional tensions of surface and space, illusion and reality in the structure of the painting. It disrupts and interrupts itself in order to disrupt and interrupt the tradition of ‘fine’ art and landscape painting, to pry open the restrictive and reductive approach to viewing art and to the artist’s viewing of his or her subject matter.

The experience of Alan Rankle’s paintings is one which includes and reflects back upon the viewer, just as subject matter is included and reflected back upon. This absolute integration of the works in their environment, be it in a gallery, in a specific architectural space, or in public, is what ultimately gives them their optimism – like a double-sided mirror through which we can both see ourselves and pass through to the other side to see what lies beyond – and their dynamism – the potential born from the dialectics of discourse to spark transformation.

It’s Not Dark Yet I

2017

Pigmented ink, Conté, acrylic,

on paper 47x31cm Reprinted from Painting and Landscape: Extending the Dialogue, exhibition catalogue, Southampton City Art Gallery, 1993

PASTORAL COLLATERAL

In an interview with Anna McNay about his Pastoral Collateral series the artist stated:

‘I wanted to relate ideas about historical, idealised, pastoral landscape in art to the grim reality of the environmental crisis that we are in, which isn’t just an environmental crisis anymore, it’s a totally impregnated social and political crisis heading towards disaster. Considering the historical origins of the genre in relation to my own paintings, I wanted to convey the irony implicit in how the 19th century Romantic movement, with its emphasis on the idyllic natural world of an imaginary past, was sponsored by people who, having made gigantic fortunes out of the Industrial Revolution by building their empires on the slave trade and the criminal use of the Enclosures Acts forcing the poor from their traditional peasant homes to work in their factories and mills, also laid the foundations of environmental pollution on a catastrophic scale’.

Turner and other artists were commissioned by the barons of the Industrial Revolution to take the Grand Tour and pick up ideas from artists such as Claude Lorrain, Titian, Dughet and Poussin, who were themselves employed to evoke the fantasy of a golden age, a sort of Narnia in Ancient Greece and Rome, where people talked to animals and fucked gods.

While you can’t look at any period of history without seeing similar scenarios, where the art is created for the tyrants and oppressors, this dichotomy of the landscape of Romance is particularly and acutely about the subject that I’ve been interested and involved in. It’s impossible to work in landscape art without it being a political act, and I thought let’s put this right up front. So that’s the title.’

Extract from an Interview with Anna McNay for International Times, 2018