10 minute read

Mark Adams

Mark Adams wrote these words in 1991 after thirty-five successful years of designing tapestries—more than a hundred in total—that were thoroughly modern in both form and subject. An unusually versatile artist, Adams, who trained as a painter at Syracuse University and with Abstract Expressionist Hans Hofmann, worked in tapestry, mosaic, prints, and stained glass, as well as several forms of painting, creating works of art both large and small that ran the gamut from realism to abstraction. But it was in tapestry that he had his earliest success, and they remain among his most important works of art.

Tapestry, with its architectural scale, long figurative tradition, and idiosyncratic use of color, first drew Adams’s attention in the late 1940s, when he saw both the medieval tapestries at the Cloisters in New York and an exhibition catalogue of modern French tapestry. Adams’s continuing interest in representational art, despite his training in abstraction, his desire to work in large scale, his interest in religious subjects, and a Matisse retrospective he saw at the Philadelphia Museum of Art that expanded his understanding of the effects color and form could have on spatial dynamics undoubtedly contributed to his interest in designing tapestries himself.

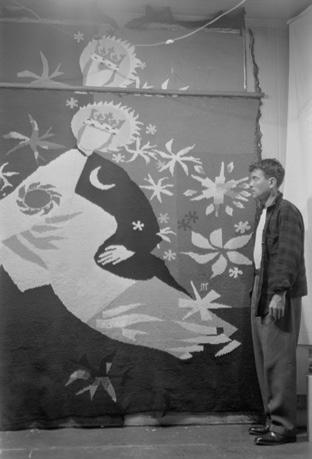

To learn how, Adams apprenticed himself in 1955 to Jean Lurçat, widely regarded as the architect of modern French tapestry. Lurçat, also a painter, had reinvigorated traditional Aubusson weaving by reintroducing some key features of medieval tapestry:

1. Use a robust coarse weave. 2. Use a simplified palette of color. 3. Build the design on strong value contrasts. 4. Use shading that is unique to weaving.

In so doing, Lurçat strove to divorce tapestry design from its adherence to painterly aesthetics, which he and many others blamed for the medium’s centuries-long decline. He went so far as to refuse to paint his design cartoons (the full-size designs from which tapestries are woven), instead drawing the outlines and indicating colors by number. Adams, who spent four months studying with Lurçat in France, preferred to fully paint his Melissa Leventon

…[T]he hardest part of tapestry making is creating a design so appropriate for tapestry that it would not be successful in any other medium.

—Mark Adams

opposite: 23. Beth Van Hoesen (1926 – 2010)

Mark Adams (Study for Watercolor), 1980

own design cartoons, noting that he had to see the colors; he couldn’t simply carry them in his head. He also sometimes used Matisse-like paper cutouts in developing the design. Still, he adopted or adapted much else of what Lurçat taught him. The most valuable lesson he learned was the one that, as a colorist, he had the most trouble accepting and integrating into his work: what matters most in tapestry is not color, which inevitably fades, but value relationships between light and dark.

The 1950s was an odd time for an American painter to pursue a career in tapestry design. Tapestry had been a popular decoration for grand homes and public buildings in the U.S. in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries. Antique European examples were enthusiastically collected by the well-to-do and there was sufficient interest in new weavings executed in traditional style to support, for a time, three domestic tapestry design studios, each employing its own, mostly French-trained weavers. All three were closed by 1934, victims of the Depression and the 1930s shift in taste to modernism in architecture and interior decoration. Modernists favored abstract textiles that emphasized structure and texture over surface design and were more likely to be inspired by architecture than art. Both the look and philosophy of modernist American textiles were strongly influenced by the European designer-craftsmen—Anni Albers, Trude Guermonprez, Marianne Strengell, and others—who came to the U.S. fleeing persecution or looking for opportunity, and who ended up working as heads of their own studios, consultants to industry, and/or teachers in a host of craft-based programs in colleges and universities. Along with American counterparts such as designer-weaver Dorothy Wright Liebes, they inculcated a generation of Americans in the belief that crafts such as weaving were of particular value in service to industrial production, and that good design sprang from craftsmanship and experimentation with materials and technique.

By the early 1960s, the model of the designer-craftsman in service to industry had begun to give way to the model of the artist-craftsman making unique, often processoriented works as art. In textiles, now known as fiber art, artists began to concentrate on off-loom and other non-traditional techniques. California, Adams’s adopted home, which offered academic craft programs at a number of college campuses statewide, an active community of resident artist-craftsmen, and ample opportunities for exhibition, was particularly fertile ground for fiber.

Adams, however, was not an artist-craftsman; his professional associates were other Bay Area figurative painters and printmakers such as Wayne Thiebaud, Gordon Cook, and Adams’s wife, Beth Van Hoesen; and he seems largely to have worked apart from the contemporary American fiber mainstream. He had acquired basic training in tapestry weaving at the Ecole National d’Art Decoratif in Aubusson in 1955 but plainly from the desire to better understand how tapestry weaving affected design, and not in the expectation of weaving his own work. In his view, “…the time it takes to excel in weaving is time

lost in growth as an artist/designer,” a position that separated him from most others working in contemporary textiles in the U.S. and may have deprived him of some of the critical attention his tapestries should otherwise have commanded. He participated in few designer-craftsman group shows, mainly in the 1960s, but he is missing from most of the books written about contemporary American art textiles from the 1970s on. He did show at the two Tapestry Biennales in Lausanne over which Lurçat presided, entering Great Wing, a big, beautiful detail view of a befeathered wing in glowing colors inspired by the Cloisters tapestries and the medieval Apocalypse tapestry series in Angers, in 1962 and Flight of Angels, a more abstract treatment of the wing theme, in 1965. His 1967 Biennale entry was not accepted and there is no record of Adams applying again. Perhaps he felt out of step with the Biennale’s direction: as time passed the festival increasingly favored the artist-made, abstract, experimental pieces that were coming to dominate the American and influential Eastern European fiber scenes.

Adams’s paramount interest in tapestry was design and he believed that great design resulted not from weaving but from drawing. Adams drew regularly, likening it to the discipline of practicing scales on the piano. Drawing, he felt, was one of the most fundamental forms of human communication; staying proficient let him access and develop his wellspring of ideas, connect deeply with his subject, reach out to his audience, and offered him the possibility of creating not just good works of art but great ones. Adams practiced designing cartoons as well; one exercise, called “Ten Tapestries in Ten Days,” involved starting and finishing one four-foot by five-foot design cartoon daily for ten days and on the eleventh day assessing the results and choosing which, if any, to continue to develop for eventual weaving. Artist-weaver Constance Hunt, who tried the exercise after Adams recommended it, found it “very intense”; it challenged and stretched her, enabling her to dig deeper conceptually than before. While Adams did not articulate this as the point of the exercise, presumably he found it of similar benefit.

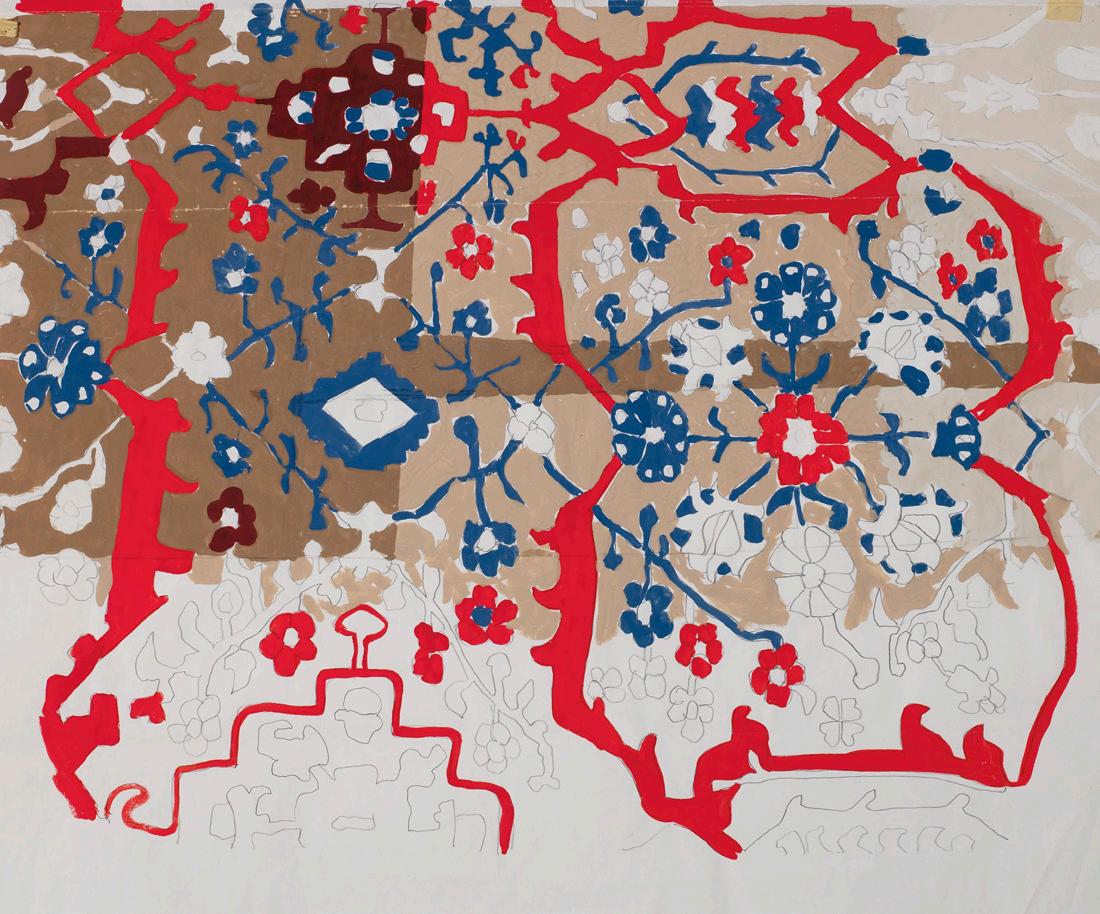

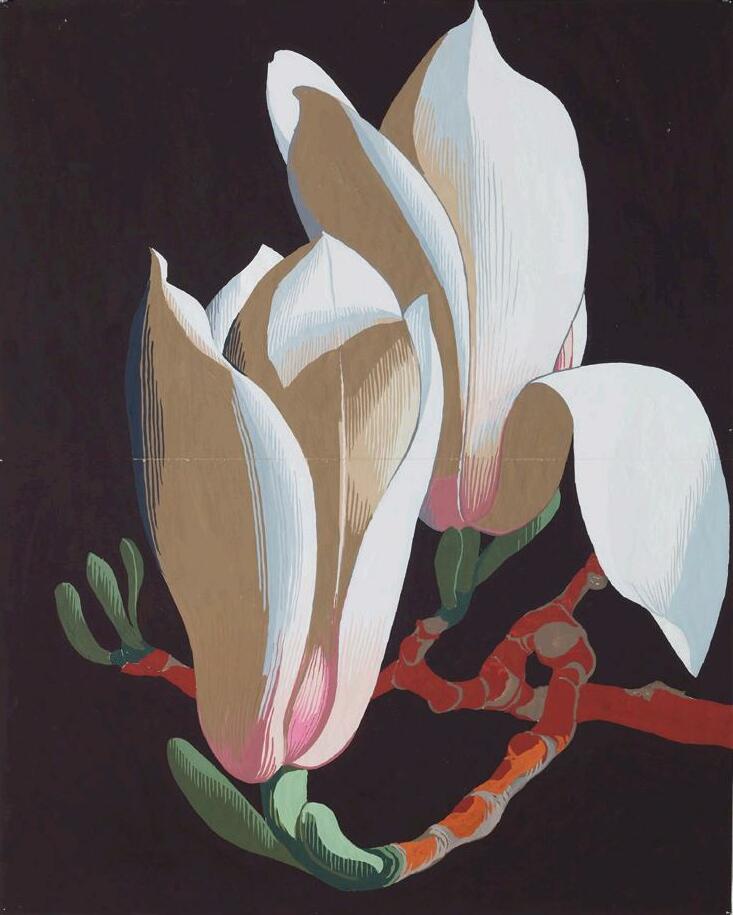

For Adams, a successful tapestry was one that worked with, not against, its two-dimensional, mural nature and which simultaneously communicated visually and connected emotionally with the viewer. Tapestry lends itself to grandeur but Adams’s subjects are modern and often familiar, drawn from the world around him and rendered without borders; a vase of petunias or a glass of water on a table, a bunch of grapes, or, more exotically, a lotus flower seen on vacation in Sumatra or a Hawaiian sunset. His religious imagery is also simplified, perhaps in pursuit of the emotional directness he admired in medieval tapestries and that he wished to capture. His fondness for portraying subjects in close-up may have been another way of connecting emotionally with the viewer; the scale of the imagery is larger-than-life but its effect is intimate. Adams believed tapestry needed firmly delineated shapes, line, and pattern that could combine to produce a sense of shallow depth and textural richness; many of his tapestries feature layers of

pattern but he resolutely steered them away from the delicate shading and shadowing he used to render similar subjects in paint. Most important perhaps is color: he had the ability to translate paint colors into wool and deftly used hachures to modulate between adjacent hues. Following Lurçat’s dictum of limiting the palette, he used only about fifty shades, but they easily sufficed to evoke place, atmosphere, mood, and time of day. Mature works such as the important Garden triptych (1981 – 1983) commissioned by the San Francisco Airport Commission and recently returned to public view at the San Francisco International Airport, show him at the height of his powers: Pond in Golden Gate Park, the first of the three panels, features a stand of white iris before a carpet of small pink and red flowers. Dark trees behind, silhouetted against a fading pink and yellow sunset, signal that night is falling, but the trees’ reflection in the pond and the hachures mediating between treetops and sky give the impression of a few rays of light still glinting through the branches. The scene’s surface is busy and multilayered, but the effect is both visually exciting and invitingly still.

The assurance of Adams’s later tapestries is due both to his mastery of all these design elements and his involvement in their execution. Until the late 1970s, his tapestries were woven in Aubusson, usually by Paul Avignon, whom he had met in 1955. Adams seems to have shared Lurçat’s conviction that only the artist should make aesthetic decisions about a tapestry but in practical terms the distance between Aubusson and San Francisco made it impossible for him to direct Avignon’s aesthetic choices or explore alternatives. Describing the process, he commented wryly, “I would just send it [the design cartoon] over there in a tube and they would send the tapestry back in a tube.” He was understandably delighted when a local option developed through a demonstration weaving staged in 1976 as part of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s exhibition Five Centuries of Tapestry. Nine volunteers, many of them students at San Francisco State University, under the direction of third-generation tapestry weaver Jean-Pierre Larochette, wove a small Adams tapestry using yarn supplied by Avignon. The project ultimately spawned the San Francisco Tapestry Workshop (SFTW), founded by Larochette and three of the demonstration weavers—Phoebe McAfee, Ernestine Bianchi, and Ruth Tannenbaum (Scheuer). The SFTW began operations as a professional tapestry atelier and school in October 1977. With the sole exception of the twenty-four-foot In Celebration of Cabeza de Vaca, too large for the San Francisco looms, Adams never again had a tapestry woven in France.

From the outset, the SFTW took a different aesthetic approach to executing Adams’s designs. Larochette recommended to Adams a “…more design-oriented sequence of hatchings…” and a slightly broader palette for more nuanced, less starkly modern results. Instead of custom-dyeing the yarn as Avignon did, the SFTW blended commercially dyed yarns of different but similar tones—a process known as mélange—until the desired shade was achieved. Adams retained the final say on how he wanted each tapestry to

look—he approved all color samples and weaver Rudi Richardson noted that if Adams was not happy with a portion of the weaving they would redo it—but being able to see a tapestry in progress and discuss it with the weavers must have added enormously to his understanding of what was possible. He could also adjust the design cartoon while the tapestry was being made if he chose. At the SFTW, Adams worked most often with McAfee and Richardson, and solely with them after they struck out on their own in 1981. Experience settled the three into an easy, collaborative working relationship; Adams was happy to have their input and confident in their ability to realize his designs to his satisfaction.

After a fifteen-year boom, the early 1990s saw a period of decline in tapestry—indeed, in contemporary fiber in general—likely sparked by an economic recession as well as changes in fashion. Adams’s tapestry commissions dried up and he did not care to have additional uncommissioned pieces woven; although he continued to create design cartoons, his last new tapestry, Lilith, came off the loom in 1991, nearly fifteen years before his death. Adams, hewing to his own, idiosyncratic path, mastered his medium in a way few of his contemporaries could match and in so doing developed a truly modern, American style for this most traditional of European textile forms.

Melissa Leventon

former curator of textiles, fine arts museums of san francisco, california, and principal of curatrix