6 minute read

A Resilient Thought

4A RESILIENT THOUGHT

By: Tom Reynolds, PE, Silman

Before I started to write this article, I actually Googled “Can you write an article in the first person?” The results were mixed; most said it depends on the editor or the tone of the publication. Well, this publication encourages free thinking, deep thought, and new and exciting ways to approach a challenge (in my humble opinion). I’m going for it – I think it makes for a compelling story.

I’m sitting on the train as I write this, returning from a day trip to Washington, D.C. About two hours ago, I sent my nine-year-old son a picture of the U.S. Capitol Building. My first thought as I took the picture (aside from observing the police barriers surrounding it at street level) was that it is set way up high from the ground level. The setting of the building on its perch led me to think about how resilient the structure would be during a major climate event (I’m an “enginerd” – we like this stuff). Juxtapose that siting with the ever-present need for designers to create buildings that serve the public’s need and can withstand the effects of a permanently evolving climate and you have one potential solution to a serious problem.

The problem is the word “resiliency;” it’s become a buzzword in the AEC industry, but its significance is much greater. Designing for resilience is a real and important part of the approach to any new and existing structures, especially in the coastal and low-lying areas of the Northeast. Climate events, not just past but in the very near future, have caused and will continue to cause flooding and major damage in coastal and inland areas throughout New York State. The example I’m going to present likely isn’t the first or last time you’ll read about a solution of this kind, but it may prove unique and adaptable to similar challenges. Complex problems often have straightforward solutions. I’m a huge fan of the K.I.S.S (Keep It Simple, Stupid) principle - it was one of the first things that Robert Silman, founder of the firm I work for, taught me. I find that frequently the easiest solutions can solve the greatest number of problems and are often cost effective and buildable. The siting of new and existing buildings has become a key part of the process, especially considering the ever-changing building code-prescribed flood elevations embedded in current design standards. One way to make an existing structure adaptable to climate change, or develop a new building, is to raise it. When you start from scratch at the beginning of the design process, this can be a simpler part of the process; you can build the building on stilts or work with landscape architects and civil engineers to raise the building grade above the design flood elevation. What do you do if it’s an existing building? What do you do if the current ground-floor slab is multiple feet below the code-prescribed design flood elevation? You raise it. Raising an existing building isn’t a new concept—a stroll around Breezy Point in Queens or through any neighborhood on the east end of Long Island would showcase many existing and in-construction residences raised above the current design flood elevation, most likely out of necessity after the effects of Hurricane Sandy in 2012. What about raising a public building, with an existing concrete joist-framed roof and an existing

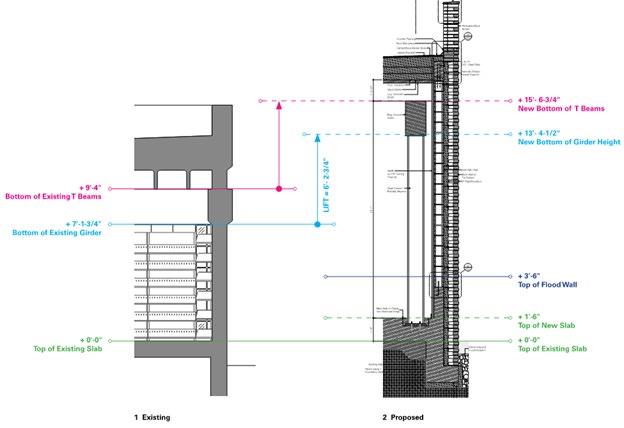

Figure 1: Existing slab and roof framing with proposed new slab elevation and raised roof slab. Credit: LEVENBETTS

ground-floor slab below the design flood elevation? There is a one-story public building in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn that sits within an AE flood zone, with a ground-floor slab that is 3’-6” feet below the design flood elevation set by FEMA and the New York City Building Code. The public use of the building requires it to be dry-floodproofed (meaning the designers need to create a waterproof box and divert potential flood waters away from the interior of the structure). The brutalist approach is to build concrete walls around the building with the top of the wall at the design flood elevation and to create a bunker so that no water gets inside; the problem is no light gets inside either and as a result, no one wants to go inside the building at all (and this is why engineers need architects). I believe that the solution is to raise the ground-floor slab and the existing roof. Raising the ground-floor slab is a bit of misnomer; holding down the hydrostatic pressure from flood loads so that the building doesn’t float away with a whole lot of additional concrete would be far more accurate. Simply put, the design team proposed adding a new, much heavier slab at the ground floor to push floodwater back down when it tries to push up from under the existing slab. Figure 1 above shows the trickier part of the equation. As noted above, the design flood elevation and proposed top of the exterior flood wall is 3’-6” above the top of the existing slab which would leave less than 4’ of space from the top of the exterior flood wall to the underside of the existing girders, as well as less than 6’-0” from the top of the new slab to the underside of the existing framing, neither of which are desirable. The designers proposed raising the existing roof by 6’-2 ¾” to create the necessary head clearance in the interior and the desired aesthetic on the exterior. The result is a flood-resilient structure that provides the light and access required by the Red Hook constituents who will use and fund upgrades to the existing building.

continued on page 20

Figure 2: Rendering of the exterior of the dry-floodproofed building. Note the flood wall at the base of the exterior window at the center of the picture. Credit: LEVENBETTS

Simple solutions can still be elegant (claims the engineer). The rendering shown in Figure 2 above (the project isn’t built yet) shows what the renovated, flood-resilient building will look like. The casual observer would never know the gymnastics the design team went through so that this building could remain functional after a severe climate event. Building designers are faced with similar challenges every day; the solution presented here isn’t ground-breaking, but it is cost-effective, buildable, and is one straightforward way to create resiliency in a range of building types. l Thomas Reynolds, received his BS in Civil Engineering from Manhattan College and has been a structural engineer at Silman since 2005. Tom has worked on some of Silman’s most high profile projects including the Krause Gateway Center, the Laboratory Medicine Building for MSKCC and multiple public works projects throughout New York City.

EXCEPTIONAL SPACES START WITH QUALITY

Designed to exceed industry performance standards, Marvin windows and doors bring a sense of comfort into every room, and our thoughtful features and unsurpassed design flexibility will support you in your efforts to create that exceptional space and truly inspiring experience.

Discover the possibilities at marvin.com.