8 minute read

Relational Wellness: Addressing Conflict in the Professional and Personal Lives of Dental Professionals

By Shahram “Sean” Shekib, JD, DDS, FAGD, and Martin Applebaum, JD, MA

One of your patients, Alice Smith, is very unhappy. You have performed several procedures on Alice over the years, and more work is needed. Two weeks ago, you restored her tooth No. 19 with a crown. Alice came in three days later, complaining of pain. After examining the No. 19 crown and radiograph, you told her that there was just some inflammation, and you gave her medication to ease the discomfort. You let her know that she should be fine in a week.

Alice has now come back with the crown you made in her hand, wearing another crown in her mouth made by a different dentist that she also says doesn’t fit right. Looking at the other dentist’s work, you see that the crown is very poorly made — the contacts are wide open, and the bite is high. You also fear that there is new damage to Alice’s teeth and gums.

Alice — angry, frustrated and upset — has come to demand her money back for a crown that she says you did not do right. Yes, one of your patients is unhappy, and now you are also unhappy and perhaps quite stressed and frustrated over Alice’s accusations and demands.

How Do You Handle Conflict?

Conflicts like this arise as a matter of course in the professional lives of dentists and their staff (and sometimes between dentists and their staff, as well as between dentists in their partnerships). Conflict also arises in our personal lives, taking myriad forms: a car accident or other civil complaint; decisions regarding the care of an elderly loved one or the disposition of their estate; a divorce or child custody issue; a dispute between neighbors or with a landlord; and many other situations that may come up.

How do you handle conflict when it comes your way? Do you react heatedly? Do you obsess over what happened? Do you just give in? Or do you simply turn off? Does how you react to conflict address it, avoid it or aggravate it? Does your response to conflict lead to pragmatic solutions that are satisfactory to all? Or does it lead to your reputation being impugned and cast you down the long, winding and emotionally draining road of costly litigation?

Your health and wellness — and that of others you encounter — may depend on how you respond to conflict. As trained mediators practicing in a wide range of areas, we have developed a deep expertise in conflict resolution. And we would like to share some tips with you.

First, what exactly do mediators do? Mediation is a voluntary process in which trained, neutral professionals facilitate conversations between the participants in a dispute, empowering the participants to come to their own resolution of the issues. Mediators do not act like judges or arbitrators who decide the issues as they see fit; rather, the participants fashion their own outcome. The mediation process is also confidential. What is said in mediation stays in mediation, and this creates a safe and open space for discussion.

How Do Mediators Facilitate Discussion of the Issues?

First, the mediator restates to each participant what they have said. This simple technique has the effect of ensuring that each participant feels heard. It also allows each participant to hear what others have to say from a fresh voice, since very often people in conflict have difficulty listening to one another.

Next, the mediator reframes and summarizes what each participant has said, bringing the focus down to the underlying values, needs and interests that are driving the conflict. For example, in a noise complaint, what does sound mean to each participant? Well, the downstairs neighbor may want quiet enjoyment of their apartment while the upstairs neighbor may want the freedom to express themselves, perhaps by playing music.

Then, once issues are addressed at this level (quiet vs. freedom, in our example), the participants are encouraged to brainstorm solutions to their deeply held concerns. In our noise complaint, perhaps the time of day the music is played can be adjusted, or the location in the apartment where it is played can be changed, or a carpet can be put down. Or the sound may not be the real issue at all, with something personal coming between the neighbors — and this too may be uncovered and addressed.

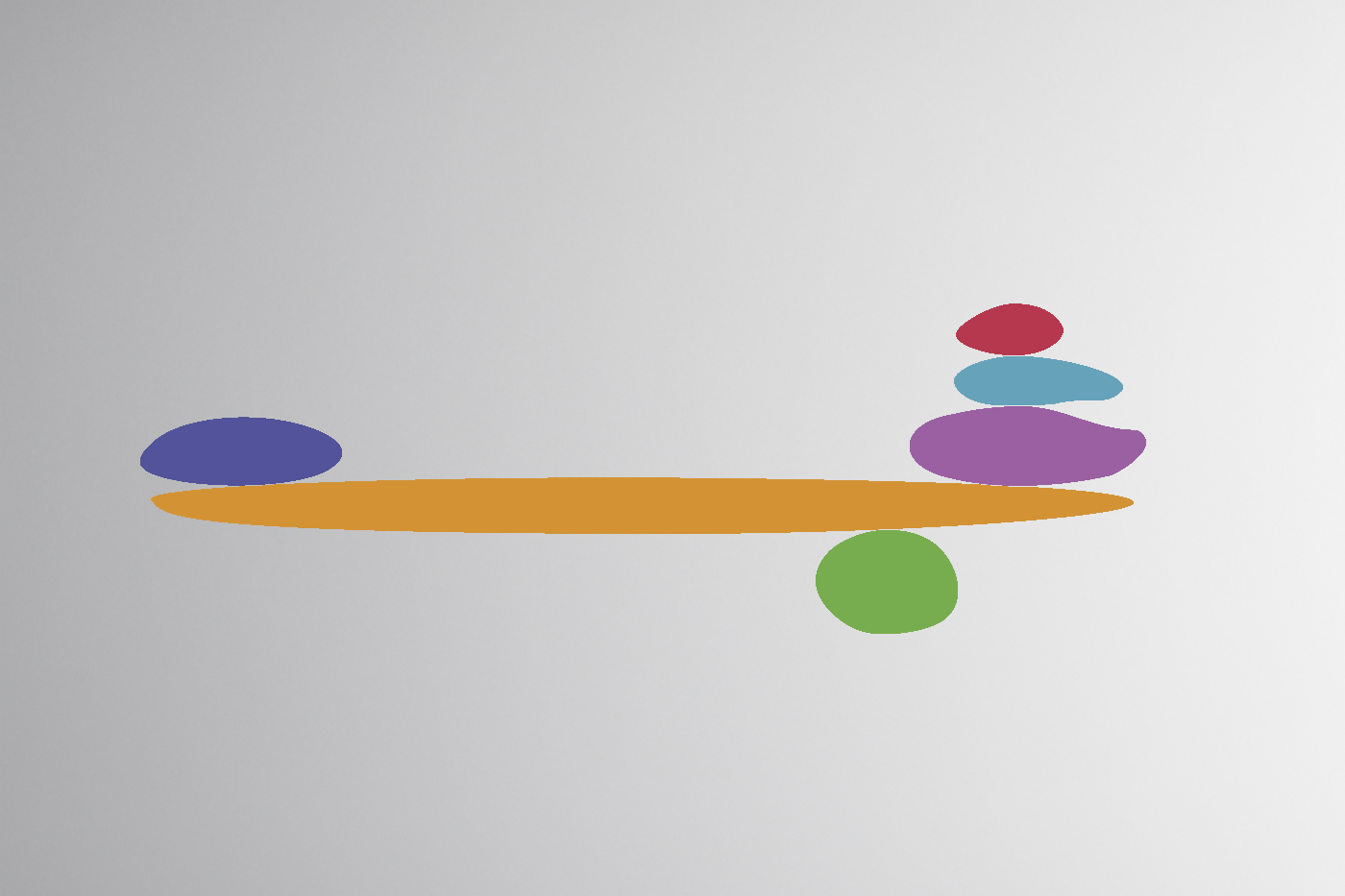

These techniques create openness and empathy between the participants so that they may listen past their positions to what lies below — to their values, needs and interests. This is where resolution of the conflict will take place, with participants crafting their own viable resolution by mutually fashioning win-win responses to participant needs.

Finally, to create security between the participants, a mediated agreement may be written that memorializes the resolution and serves as proof.

The mediation process is typically initiated in either of two ways. In private mediation, those in conflict may agree on their own to retain a neutral mediation firm to facilitate the voluntary process. In presumptive mediation, a court may mandate that the parties in dispute first try to resolve the issue through mediation before a trial may proceed, though they are free to withdraw at any point and return to the litigation process. Participants, if they are represented, may choose to have their attorneys attend the mediation with them or not.

Mediating Everyday Disputes

Having undertaken hundreds of mediations, we have compiled nine takeaways that dentists can use in their professional and personal lives for everyday disputes:

See conflict not as a bitter fight between adversaries, but as an opportunity to creatively work through often-difficult issues in order to reach workable solutions and find mutual understanding.

Breathe. Don’t get caught up in reactivity to another’s words and demeanor. Be mindful of your feelings, your biases, how your shoulders tighten, etc. Noticing your mental and physical reactivity, you are already beginning to distance yourself from them so that you can listen and respond with greater clarity. Your calm spaciousness sets the table for all. It is hard for others to maintain anger and defensiveness when none comes back at them.

Listen to what others have to say. Please take care. There are different kinds of listening. Don’t just listen to win the argument; instead, listen empathetically, trying to understand where the other person is coming from and how they ended up where they are. Also listen below the speakers’ positions to the values, interests and needs that matter to them — that is where mutual understanding lies.

Use restating, reframing and summarizing techniques that acknowledge the person you are speaking with so that they will relax and listen. Use the same techniques described above that the professionals use. Scientific studies indicate that anger can dissipate after only 90 seconds, so employing these “slowing down” techniques calms down the person you are speaking with and may make them less defensive.

Frame consideration of the problem in terms of underlying interests/needs/values. Goals may differ, but often the values underlying the problem (e.g., quiet vs. freedom) are values both sides can understand as worthwhile.

In discussions, avoid attack and accusation, and use “I” phrases (e.g., “I feel”) instead of “you” phrases (e.g., “you did”). Blaming causes people to shut down and put up walls in defensiveness. Try to move matters forward in deeds and words.

Place the conflict within the context of your venture’s purpose. Let the other person know the best of your intentions and what you do as a professional and who you are as a person.

Brainstorm. This involves carefully listening to both the facts and the values inherent in the situation in order to work together to generate creative, win-win solutions.

Remember relationship. Where there is a positive shared history, place the dispute within its larger context. Where there is no strong relationship, envision how you wish it to be going forward.

These simple mediation and meditation techniques can help turn what would otherwise be painful and unproductive conflicts into opportunities to meet the needs of all those involved in positive and skillful ways. And where conflict is complex or entrenched, please consider mediation as a beneficial alternative to more adversarial dispute resolution processes.

In conflict, you can only make yourself and those around you fulfilled and at ease by doing so together. But the people around you need your help. Why not take the lead and become a healer of conflict?

Shahram “Sean” Shekib, JD, DDS, FAGD, FICD, FAADS, FPFA, FACD, is the immediate past president of the New York State AGD and has also received his Juris Doctor from Mitchell Hamline School of Law. Serving as a member of the peer review committee of the Second District Dental Society, Shekib helped to resolve disputes between healthcare providers and patients and, in the course of obtaining his legal degree, has become a certified mediator.

Martin Applebaum, MA, JD, graduated from Georgetown Law Center. Looking to get to the heart of the matter of conflict, he took up the practice of mediation and has since mediated over 300 cases in areas involving family issues, contract and business disputes, and other matters. Applebaum frequently presents seminars on mediation and mediation techniques. To comment on this article, email impact@agd.org.