15 minute read

Volunteering in Central America and Cambodia: For the Big-Hearted, Not the Faint of Heart

A synopsis of this article appeared in the print version of AGD Impact. Below is the full version.

By Carl D. Werts, DDS, FAGD

Carl D. Werts, DDS, FAGD, began his journey into dental mission work in 2008, after a 25+ year career practicing general dentistry. When the economic downturn left him with spare time, he visited a patient working with the homeless in Los Angeles, which led him to volunteer at LA Christian Health Centers. It was there that Werts learned oral surgery, focusing on extractions, and discovered his passion for helping underserved communities. His mission work expanded to international trips, starting with China and later to Central America.

In 2018, he joined the Cambodian Health Professionals Association. Werts enjoys the challenges these trips to Cambodia present, such as limited resources and unfamiliar environments, but finds great fulfillment in providing dental care to those in desperate need. Werts’ experiences have deepened his commitment to giving back. For him, the personal rewards of these trips are immeasurable, driven by gratitude from the patients he serves.

How did you start going on mission trips?

I started practicing in 1980. For the first 25+ years, I only did general dentistry and referred out all specialties. In 2008, as the economy tanked and an office crisis hit, I found myself with days that had no patients scheduled. I had to do something with my time.

I visited a patient who worked with the homeless community of skid row in Los Angeles, helping them get into their own single-room apartments. As he helped them get back on their feet, I asked about their dental care. He didn’t have an answer but referred me to LA Christian Health Centers. Out of curiosity, I visited and was immediately asked when I could start. “Next week?” I said, and was told, “Oh, and by the way, we mostly do extractions.”

“I haven’t done an extraction in 25 years.”

“Well, you’re going to learn how.”

Learn, I did. I also learned that I enjoyed doing oral surgery, but I needed to take courses to get better. This began a journey that expanded my abilities in dentistry to the point where I could handle almost anything — at the drop of a hat. Working in downtown Los Angeles, you never knew who your next patient would be. This is something I enjoy doing, and I have continued to volunteer once a month at either skid row or a satellite clinic in Boyle Heights. It’s now been 16 years, and it keeps life in perspective, treating those less fortunate.

One of the AGD courses I attended was taught by Dr. Karl Koerner on oral surgery for the general practitioner. During his lecture, he showed slides from a dental mission he arranges each year to China. The services they provided were what I had just become proficient in, so I inquired, volunteered and was accepted to the team.

I previously had a high-altitude mountaineering career and had traveled to far (and high) places around the globe. I had not been to China, so that was an additional bonus. It was a great trip. The team bonded as new best friends, the patients were extremely appreciative, and it was a wonderful way to experience travel far from the tourist perspective.

A few years later, I joined an organization called Los Médicos Voladores, “The Flying Doctors” (LMV). They primarily do clinic trips to Baja California, Mexico, but once a year, they go to Central America, usually Guatemala. I hadn’t been to Central America, so it seemed like another great opportunity to see a new part of the world. My first trip was in 2016, and it has become an annual mission.

One of the LMV team members was a psychiatrist, and over several years, she told me about another mission she does annually — to Cambodia, with the Cambodian Health Professionals Association of America (CHPAA). In 2018, I decided to go. I applied and, with her recommendation and my Guatemala experience, was accepted to the team. The mission is large — about 125 volunteers from all over the U.S. — and all phases of medical care are offered, within the scope of what a foreign medical mission can provide. We are matched by a team of health professionals and volunteers from Cambodia. CHPAA is well-known and has full support from the government.

Visiting Cambodia was an extremely eye-opening experience. Our mission goes to the poorest provinces, changing locations each year. Anyone over 50 years old is a survivor of the Killing Fields under the tyranny of dictator Pol Pot in the 1970s. They have endured unfathomable loss and hardship. The leaders and founders of CHPAA are doctors who survived, escaped to Thailand and later came to the U.S. for their medical training. After having their own careers, they now give back to their people through medical mission work.

These are purely humanitarian missions — there are no political or religious affiliations. To go on these missions, you must have a strong desire to give back. We take time out of our professional lives, pay for our own airfare, and cover the costs of hotels, meals and transportation. All other mission expenses are covered by donations and fundraising. It’s an amazing group of individuals, all with big hearts. This is the reward of these trips: to be a team member with such wonderful people.

I’ve gone to Cambodia in 2018, 2019, 2023 and 2024, and I’ll be returning for the next mission in 2025. Over this time, I’ve gone from being a volunteer dentist in a small group of U.S. dentists, working alongside Cambodian dental students and their instructors, to organizing the dental department and expanding the team to 25 dentists, hygienists and dental students. Our goal is to teach and share our knowledge and skills, but we also treat many patients, with extractions being the primary service.

How are the trips organized?

These organized trips take place annually, with many additional members in supporting roles.

The China trip is primarily organized by Dr. Koerner in conjunction with Latter-Day Saints (LDS) Missions. While it’s not required to be a member of the Mormon church to participate, there are also trips to Africa where membership in the LDS Dentist Association is necessary.

The Guatemala trip is organized by LMV, which was formed 50 years ago when doctors and pilots got together to help remote Mexican villages. The Guatemala mission has grown immensely since then. For Guatemala, there is a leader who has been organizing the trip for about 12 years. We apply through him, and he takes care of the logistics. There is a core group of members who go each year, and we have become good friends, looking forward to seeing each other like returning to summer camp.

For Cambodia, CHPAA is highly organized with several executive committees. They’ve been going to Cambodia for 15 years, and, although each trip is unique with different challenges (since we change provinces each year), the general logistics remain the same.

How many people go at a time?

For the China trip, we were a group of 18 from the U.S., and this was exclusively a dental mission, with a plastic surgeon to perform cleft palate surgeries. We worked at a dental school/hospital, with more than 60 local counterparts, including dentists, dental students, nurses and translators.

For Guatemala, our group typically consists of about 25 people from the U.S., plus medical colleagues from Guatemala and El Salvador. We receive local support, and the organizing group has recently included Rotarians in Guatemala.

For Cambodia, around 125 volunteers fly over from the U.S. each year. Locally, we receive support from another 125-150 volunteers from Cambodia. For the upcoming mission, we requested 15 local dental students to join the team, and we received 130 applications!

Where have you traveled?

In Guatemala, we usually meet in Antigua, a lovely colonial town, though it has become quite touristy in recent years. For missions, we stay in Quetzaltenango (“Xela”) and head out to a clinic in Tierra Colorada Baja. This region is home to indigenous Mayan descendants, for whom the government provides little help. Most live on a few dollars a day, and their colorful, handmade clothing tells the story of where they’re from. It feels like a different world, yet it’s only a 4 ½-hour flight away.

We work at a small local health clinic. Word of the mission spreads via banners and word of mouth, increasing the number of patients throughout the week. The clinic setup involves using outdoor spaces for waiting and check-ins, with makeshift rooms set up with curtains for privacy. For a medical examination table, we make do with what is available. A table with a foam pad works just fine.

The facility already had a “dental clinic,” which consisted of two dental chairs, one with no light. The other’s up/down function was broken, so it was too low to stand, too high to sit. It was a very small room, and the local dentist worked with me. She was fast with extractions, so she did most, and I did most of the restorative care since I could set my space up to just do that.

As for conditions: It was at some altitude, so the mornings were cool, but there was a skylight overhead, and the midday sun baked us through the glass. This is a premise of mission work: Prepare to be very uncomfortable.

We went to this clinic for three years, and, each year, another structure was built on the property with the original clinic eventually slated to be closed.

In 2019, after conflict with our counterparts in Guatemala, we chose to work in Santa Ana, El Salvador. The local medical team consisted of Salvadoran students who had graduated in Guatemala. Our original mission site had to be changed at the last minute due to political changes, but, after a social media campaign, the new president’s wife stepped in to resolve the issue.

Instead of a clinic, we were now at a school. For the dental team, it was just me and a local dentist who worked with me to pre-plan and rent equipment for the dental clinic. She also arranged for four government dentists to join us for the week, as it is their job to provide dental services in outlying areas.

Normally, dental hygiene students from Northern Arizona University join the team, but because the U.S. State Department labeled El Salvador a travel risk, they were not allowed to come. Dental hygiene is a key part of the LMV missions because, for most of these people, it is the first time they've ever had their teeth cleaned. For this mission, I brought along some volunteers, gave them five minutes of dental hygiene training on how to use a Cavitron, let them practice on me, and then sent them to work. No matter what they did, the patients would be in better condition than when they arrived. If they caused any pain, the patients would let us know.

The local government dentists simply set up tables, and the patients laid flat, without complaint. There was no suction, and patients did sit-ups to spit into a wastebasket. The dentists had no lights, no loupes — just their materials, instruments and portable units to run the drills. When one person finished and got up, the next patient lay down, staring at the ceiling with their mouth open.

All of this work is done without X-rays. Diagnoses are made through visual exams and a few questions. Often, the patients tell us what they want done: extraction or filling? Does it hurt on its own, or only when eating? We do the best we can in the circumstances, which is a tremendous help to these patients.

After the pandemic, we returned to Guatemala, but to a different location — Retalhuleu, in northwest Guatemala. The location is a rural clinic. When rooms were available, some of us got a room, while others set up in larger spaces with curtain dividers. When we arrive, we’re assigned a space and must quickly figure out how to turn it into a clinic. For dental work, we had a classroom, and our dental chairs were plastic chairs against a wall — or, as on the most recent mission, we used a gurney. The hygienists were downstairs, and they used regular hospital beds for their patients. It was uncomfortable, but workable. We split the team so a dental group could go out to rural schools to treat children. They used lawn loungers.

As for comfort, it doesn’t exist. This area is much more tropical and humid. Afternoon thunderstorms with heavy rain are the norm. We had fans, but still, you sweat profusely. On the final day of my last mission this year, I was by myself because my dentist teammate had to leave a day early. There was a snafu on the number of patients allowed in, and they kept coming. It was supposed to be a shorter day, but from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., I was stuck with a constant flow of patients — 35 patients for 65 extractions, with a 10-minute meal break at 6 p.m. These patients had waited for hours, and it was not an option that they would not be seen and treated.

As I mentioned, for Cambodia, each year we go to a different province. On these missions, we also set up a satellite clinic, dividing the teams to provide care in even more remote villages. The setting could be a clinic, hospital, or, as in the last mission, we took over a school. Cambodia in January is very hot and humid, and profuse sweating is always the case.

Over the years, CHPAA has accumulated portable dental chairs and instruments. We’re able to buy supplies in advance, and we also reach out to U.S. companies for donations. With teams of 20 to 25, leadership is essential to manage the controlled chaos. Every mission is different, and nearly every day brings new challenges. It takes flexibility, problem-solving on the fly, and the management of individuals to keep everyone focused on the mission’s goal: to provide as much care as possible to the greatest number of people in just one week.

What drives you to perform this work?

These are not staff trips; I go on these missions alone. Many people express interest in volunteering but drop out once they hear the details: the working conditions, the scope of the work and the fact that we pay to go.

I spent many years traveling and climbing for personal pleasure and challenges. While those trips were expensive and time-consuming, I now find it far more rewarding to give without expecting anything in return. Beginning with skid row, I developed a range of skills that I’m both proficient at and enjoy doing. It’s even more rewarding when monetary exchange isn’t involved — to help others in a meaningful way, for the sake of helping, is something I find deeply satisfying.

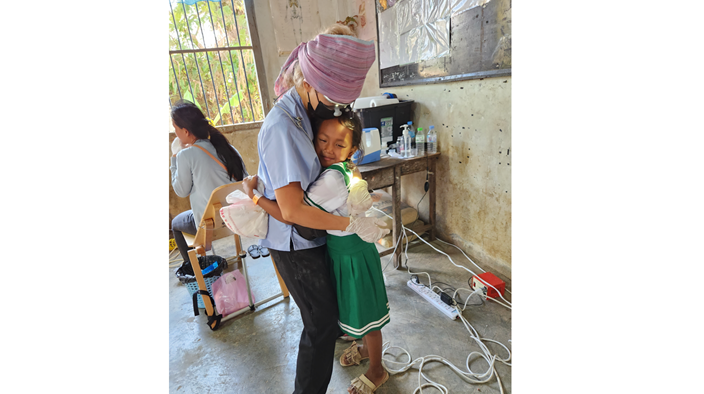

For those who join these missions, it’s a highly selective group of individuals who go to such lengths to help others who are neglected by the world. Our reward is the appreciation we receive from the people we help. The bond we share with fellow volunteers is also a huge reward.

What has been your most rewarding experience?

The ultimate reward came in Guatemala when we worked with a clinic employee who cleaned the clinic daily. She had many decayed teeth, obviously black. She feared she would be losing most of these teeth, but I could tell this was the type of decay that is shallow. I was given the green light to take care of her over the other patients, and, sitting down for two hours, I was able to restore 13 teeth. Her normal, beautiful smile returned. Looking in the mirror, she was dumbfounded and could not believe what she was seeing. She ended up sobbing in my arms, so thankful for what I had done for her. The joy she gave me is something no amount of money can buy.

What are some challenges you face?

The first challenge is accepting the realities of working in third-world countries where things rarely go as expected. You need to be flexible, constantly adapt to changing conditions and rely on minimal resources. If you don’t have the personality or stamina for that, these missions may not be for you.

Another challenge is the climate. Guatemala and Cambodia are hot and humid, and you sweat profusely. But, as the days go on, you adapt, and the excitement of the work outweighs the discomfort.

Additionally, there are instances when people try to exploit the missions for personal gain, or team members can create conflicts. It’s unfortunate, but these challenges are part of the experience. We are considered the “rich Westerners,” and even though we are giving of ourselves, our time and money, we are targets to be taken advantage of. Dentists should always be careful and stay vigilant.

And, unfortunately, although people who go on missions are special, on a few of the trips, team members show up with their own agendas. They feel they know better than the ones who regularly go, and work against the team rather than with us.

In Summary

What stands out most to me from these missions is the kindness and generosity of every team member. We leave our families, take time out of our careers and travel to the other side of the world to give of ourselves to those less fortunate. In return, each patient gives us their love and gratitude. Relieving pain and infection when no other options are available is incredibly rewarding. This is why we return year after year.

Carl D. Werts, DDS, FAGD, owns a practice in Glendale, California.