10 minute read

12 Perception and Symmetry

from Archivos 08 Symmetry

by anna font

Reiser + Umemoto, O-14. Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2010

Invariant, equivalent, identical, uniform, easy, efficient: these are a few of the qualities associated with symmetry. What unites them are the themes of consistency and utility. Symmetry is stable. Symmetry is useful. Thus, it should come as no surprise that these qualities and the symmetrical figures and operations that embody them are present— sometimes overtly and sometimes covertly—in contemporary architecture.

Advertisement

Disappearing

As the proceeding chapters have documented, while its definition and reputation has waxed and waned, symmetry has had a constant presence in architectural thought and design. Sometimes symmetry is so pervasive that it seems to disappear. The ability of symmetry to hide in plain sight has also been recognized by scholars who study the physiology and psychology of vision.1 They have found that it is so predictable and so easily perceived that symmetrical figures require less effort to detect than asymmetrical ones. As art historian Ernst Gombrich noticed, once recognized symmetry provides no new information for the eye’s “break-spotter” to engage, and so it fades into the perceptual background.2 As with William and Gregory Bateson’s biological analysis, optic symmetry is an indication that something is missing.

The mathematician and psychologist Michael Layton has studied how people respond to the objects they encounter in their perceptual environment. Using empirical methods to observe people’s vision and behavior, and group theory to study the logic of regular and irregular form, he has concluded that symmetry is a device for erasing memory.3 He maintains that while asymmetries are perceived as being transformed over time from an originally symmetrical state, the processing of symmetrical form does not. This is because symmetry is understood as being in a permanently fixed state. In other words, it has no history, and as such, there can be no memory of where it came from.4

In contrast, asymmetric figures do have a history, and our perceptual apparatus retraces the steps that they took from their original symmetrical configuration. For example, when we see a rotated parallelogram, our mind subconsciously rotates it, straightens it into a rectangle, and then shrinks it into a square. In Layton’s words, “the mind extracts the past history that produced a shape—i.e., the sequence of causal forces that produced the shape.”5 Once we get to the square the process stops. We don´t (subconsciously) inquire as to where the square came from. According to Layton’s research, we accept it as having always being that way.

Following Layton and Gombrich, symmetrical form has the paradoxical quality of being easily recognizable yet easily forgettable. It is so efficient at communicating its unchanging nature that it does not demand our full attention to understand it. It is precisely the capacity to be both recognizable and unchanging that may help explain the intentional re-emergence of symmetry in contemporary architecture. In an age where differences, complexity, and variation can so easily be produced and reproduced, symmetry’s stability and simplicity appears as a rare and useful commodity.

There are at least two ways in which symmetry is deployed today. One uses it as a figural limit that contains and contrasts itself with otherwise loosely organized shapes and spaces. The other sees symmetry less as a mode of organization than as a self-conscious sign that provides projects with an immediately recognizable, yet still elusive identity. While both modes can be found in a variety of practices, the former is more often found in those whose intricate forms are made using digital design software, while the latter strategy is more graphic and can be seen in what could be called the postdigital or neo-postmodern work.

Tension

The competition drawings for Foreign Office Architects’s Yokohama Port Terminal (1995-2002) show a series of smooth, undifferentiated interior spaces and exterior forms. Along with the diagram depicting multiple circulation loops, they are all asymmetrical. Renderings and models of the exterior, however, reveal a bilaterally symmetric condition along the building’s long axis. Looking at the project’s plans and sections, this symmetry is even more prominent, albeit with a series of breaks within it. The cross sections also reveal an underlying reflective symmetry, with slight changes in the center point from one section to the next. In other words, the line of symmetry moves or changes to accommodate specific spatial and programmatic needs.6 If one were to look at each section individually, one might conclude that the building is quite static. However, if one looks at them as a series, the history of the project emerges. In short, while one experiences a sequence of locally asymmetrical spaces, they are made possible by an underlying symmetrical structure.

The axial symmetry that one finds in these sections comes out of a solution to a construction problem, or rather to a spatial-construction problem.7 Making the cross sections symmetrical, but with different profiles, allowed the otherwise fluid forms to be easily built up from a kit of (relatively) simple, symmetrical elements. Here symmetry provides the stable armature in which fluid and complex spaces and experiences emerge. In other words, while symmetry is present in the physical and organizational structure, experientially it disappears.

The office of Young & Ayata also juxtaposes symmetry and asymmetry, but they use symmetry in a more direct way. In both their elegant conceptual drawings and their designs for buildings a symmetrical figure is often used to create a fixed border, in which clarity is not subsequently eroded or transformed despite it being filled with an intricate assortment of forms, spaces, and programs. Projects like the Dalseong Gymnasium (2014), the Busan Opera House (2011), and the Bauhaus Museum (2015) establish a clear relationship between symmetry and asymmetry. The drawings for the Dalseong Gymnasium show a pronounced contrast between the reflective symmetry of the perimeter and main spaces and the formless impression on the landscape. In plan, the reflectively symmetric entry portals and the almost symmetric circulation paths are juxtaposed with the seemingly formless outdoor spaces and the reflected ceiling plan.

An observation Young & Ayata make about their drawings applies equally to their architecture: “Symmetry is used here to fix and stabilize the figural representation (…) The figures bend and layer, sometimes twitch and wiggle under their symmetrical pinning (…) although the global gestalt is one of pure symmetry, as one looks at the images longer it becomes clear that there is no element that is purely symmetrical.”8

Symmetry serves to frame and control, not eliminate, the random. However, unlike FOA’s Yokohama Terminal, where the symmetry is hidden in the structure, Young & Ayata forcibly foreground the visual and tactile encounter with it. The tension between parts that are easily recognizable—and thus quickly fade to the background—and the more active ones that demand one’s attention illustrates once more Layton’s and Gombrich’s analysis of the inherently dialectic relationship between symmetric and asymmetric form.

Recognition

Another trend in contemporary architecture is the use of immediately identifiable architectural tropes, including symmetry, which, combined in unexpected ways, produce uncanny effects. MOS has designed a number of houses that aggregate symmetrical parts to create figural effects at once graphic and ambiguous. For example, the gable-ended modules used in the design of their Element House (2014) in New Mexico appear as bloated versions of a child’s drawing of a house.9 The combination of this well-known profile with the unexpectedly puffy sensibility—created by the thick structurally insulated panel construction system—makes for an oddly cartoonish effect. The modules are triangular in plan and, when aggregated, produce a combination of rotationally symmetrical patterns at the center of the organization and irregularly shaped appendages at its edges. Given its modularity and its clear iconographic agenda, the effect is surprisingly chaotic and disorienting. Despite the local symmetries, there is no clear hierarchy and no one place to focus one’s attention. And, in Layton’s terms, although the modules are always in a symmetrical relationship with their neighbors, the overall configuration allows one to easily image the sequence of events that produced the overall asymmetry.

One also finds multiple symmetries present in their design for a House 10: House with a Courtyard (2017). Pairs of reflectively symmetrical wings flank three sides of a square courtyard. The single leg on the fourth side appears poised to have its missing limb added at any moment. As a group, the linear organized legs have been slightly rotated relative to the courtyard, creating an unexpectedly irregular relationship between the two major compositional components. There is a tension between symmetry and asymmetry in the elevations as well. The gable-roofed wings terminate in a symmetric, iconic shape that says “I am a house.” But, there are five of these, each with a different orientation, so that no two can be seen frontally at any time, undermining any simple axial reading and making it surprisingly difficult to find a focal point on the three facades. While no two sides of the house are the same, there is seemingly no hierarchy between them. Again, even though multiple symmetries are present, their relative arrangement to one another creates a global asymmetric condition that allows one to easily imagine the “history” of the project’s formation process.

The symmetry in the Cut/Fill housing proposal (2016) by Central Standard Office Design is more easily detected. The design diagrams reveal the sequence of operations that turned five typical Chicago housing lots into a 4 x 4 grid that are subsequently sheared in plan and section to produce a scheme that is rotationally symmetric in two and three dimensions.10 Each of the quadrants is symmetrically subdivided into four more zones. Each zone accommodates four L-shaped buildings. Each of the sixteen “houses” has a pitched roof on one side and a vaulted roof on the other, with an optically ambiguous roof connecting the two. The combination of easily recognizable references—“this is a gable;” “this is a vault;” “this is a house;” or “this is symmetrical”—is combined with a massing strategy and color scheme that blurs the line between sold and void, and between one unit and another. There is enough symmetry to make it appear stable, but enough asymmetry to allow one to see the design’s history. As in any good symmetrical figure, identity and invariance are equally and ambiguously present.

Conclusion

The presence of symmetry in the work of these diverse contemporary practices presented illustrates the lasting and elastic qualities of symmetry, and is evidence of its continued relevance, or more accurately, of its usefulness. Whether helping to integrate a structural idea with a spatial one, providing a stable background for exuberant compositions, or giving graphic cover for otherwise complex objects, symmetry is still an effective architectural device. As documented, symmetry may not have the status or the job that it once had—in math, in science, or in architecture—but it does continue to do work. The question is how does it remain relevant. Is it because it is both an abstract idea and a literal organizer of matter? Is it because it can connect mental with physical processes? Is it because it is easy to use and recognize? Yes, yes, and yes. Symmetry may be sometimes simple, but it is also surprisingly plural. As such, in architecture, and elsewhere, it will continue to transform while remaining invariant. This is the symmetrical paradox: symmetry changes and symmetry endures.

1 Ernst Gombrich, The Sense of Order: A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Art (London: Phaidon, 1979). Michael Leyton, Symmetry, Causality, Mind (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992). Michael Leyton, A Generative Theory of Shape (Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2001). Michael Leyton, Process Grammar: The Basis of Morphology (Berlin: Springer, 2012). J. J. Gibson, The Perception of the Visual World (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950). Rudolf Arnheim, Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974) [1954]. Rudolf Arnheim, The Dynamics of Architectural Form (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977). 2 Gombrich, The Sense of Order, 121. 3 Michael Leyton, “Group Theory and Architecture,” Nexus Network Journal vol. 3 no. 2, (2001), 43-45. 4 Ibid. 5 Ibid., 44. 6 Foreign Office Architects, “National Glass Center, Sunderland/ Redevelopment of Cartuja Island, Seville/Yokohama Port Terminal,” AA Files no. 29 (summer, 1995), 7-21, in Albert Ferrer (ed.), The Yokohama Project: Foreign Office Architects (Barcelona: Actar, 2002). 7 Alejandro Zaera Polo, “Roller Coaster Construction,” Verb: Processing no. 1 (2001), 12-18. 8 Young & Ayata, “Symmetry Series” (2013). Accessed at http://www. young-ayata.com/funnyhairysymmetry 9 Mos Architects, “Element House,” Log 29 (Fall, 2013), 66-75. 10 Kelly Bair, “Cut/Fill,” MAS Content 29 (Spring, 2016). Accessed at http://www.mascontext.com/issues/29-bold-spring-16/cutfill/

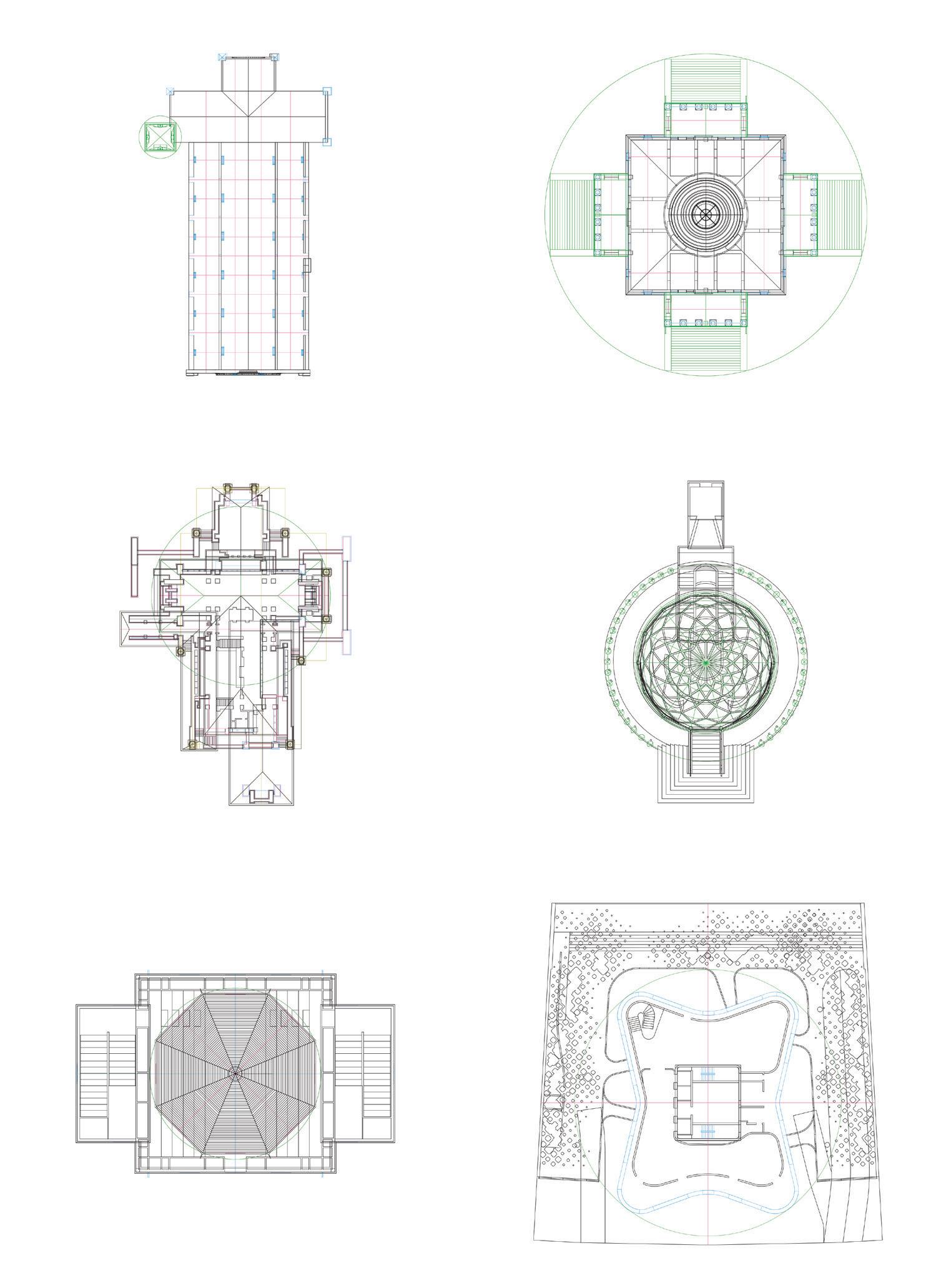

Matrix of symmetry analysis. Plans of projects with mirror reflections, translations, rotations and glide reflections. From left to right and top to bottom: Maison Carrée, Pazzi Chapel, Santa Maria Novella, Villa Capra, Barrière de la Villete, Altes Museum, Darwin D. Martin House, Glass Pavilion, Villa Savoye, Crown Hall, Teatro del Mondo, O-14