3 minute read

THE AMERICAN FRIENDS OF MUSÉE DE MONTMARTRE

WERE HONORED TO PARTICIPATE IN A PRIVATE VIRTUAL SALON WITH FIN DE SIÈCLE EXPERT, PHILLIP DENNIS CATE

Montmartre at the Fin de Siècle: The Birth of Modern Art

Advertisement

HOSTED BY PHILLIP DENNIS CATE

WEDNESDAY,MAY 11, 2022

12PM EST

Attendees learned about the hidden world of Montmartre’s artists: the cafés and cabarets they frequented, the story behind the Chat Noir, and how their world became the turn of the century center of Western art and culture.

Phillip Dennis Cate is a widely published specialist of 19th century French art whose expertise covers Montmartre, sculpture, and Japonism. He has organized programs for international institutions such as The Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg; The Russian National Library, St. Petersburg; The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; The National Museum of Japanese Art, Tokyo; and The Imperial Household, Tokyo. Previously the Director of the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum in New Jersey and a Curator of Special Exhibitions and Consultant for the Collection and Renovation of the Musée de Montmartre in Paris. Cate now works as an independent curator and critic.

The Storied Nature of

Montmartre

Sophie Evans explores the past and present dualities of the Montmartre cityscape.

“For the ground floor belongs to the fashionable; the poets, musicians, and painters prefer the third floor, where the piano moans, the violins sing, sonnets burst forth in resonant fireworks…

The second floor, between heaven and earth, between the bourgeois customers on the ground floor and the empyrean artists on the third, is where the journal Le Chat noir is edited.” So wrote Émile Goudeau in 1886, five years after Rodolphe Salis invited him and his group, The Hydropathes, to be the first artists and writers in residence at his new cabaret. The layered coexistence Goudeau describes applies equally well to the entire Montmartre neighborhood.

We can project the three stories of Le Chat Noir onto the natural landscape of Paris, where climbing the hill, “la Butte,” equates to mounting the cabaret’s stairs. With each step, Belle Époque artists left behind the bourgeois of Paris’ ground floor in exchange for the studios, cafés, theaters, restaurants, and cabarets that made up the Montmartre heavens.

On la Butte of today, those stories have been inverted. The world of the artists exists beneath a top layer dominated by tourists and residents – our era’s version of “the fashionable.” Maps of present day Montmartre attempt to present this storied nature, meticulously marking memorial alongside the quotidian. There is the atelier of Fernand Cormon at 10 Rue Constance, where Toulouse-Lautrec studied painting in 1882; the attic room at 6 Rue Cortot, where Erik Satie composed Les Gymnopédies in 1882; the Lapin Agile cabaret at

22 Rue des Saules, bought by Aristide Bruant in 1903; and, of course, the Musée de Montmartre at 12 Rue Cortot, where Auguste Renoir, Maurice Utrillo, Suzanne Valadon, and Raoul Dufy all had studios.

Street signs bearing names of past and present allow visitors and Montmartrians alike to navigate the neighborhood in the layer of their choosing. Establishments have dual identities: what they once were and what they are now. 22 Rue des Saules, for instance, was previously À Ma Campagne, and it is there that Lautrec drank copious amounts of absinthe. 18 Rue des Saules was Aux Billards En Bois before it became La Bonne Franquette of today. It is there that Renoir painted La Balançoire and also where Lautrec met up with Van Gogh (and drank copious amounts of absinthe). In other cases, names stay the same, but the nature of the place changes. There is a Chat Noir on the Boulevard de Rochechouart, but it is more tourist-trap than true cabaret. We might, therefore, think of the maps and of Montmartre itself as a type of palimpsest. Instead of a manuscript featuring layers of primary sources, we have a neighborhood exhibiting layers of establishments over time. In either case, the layers have been bound by a common location that allows them to relate to one another. Looking at Montmartre as a palimpsest allows us to explore a place whose past continues into the present. Number 12 is itself a microcosm of this phenomenon, at once a former studio and a museum, whose material extends far beyond the lives of its former inhabitants. We might also think of the Musée as the modern equivalent of Goudeau’s second floor: a space somewhere between heaven and earth that presents the artists’ world to the outsider. While Montmartre’s maps and signs aid in navigating this world, it is only through the Musée that we can first gain entry.

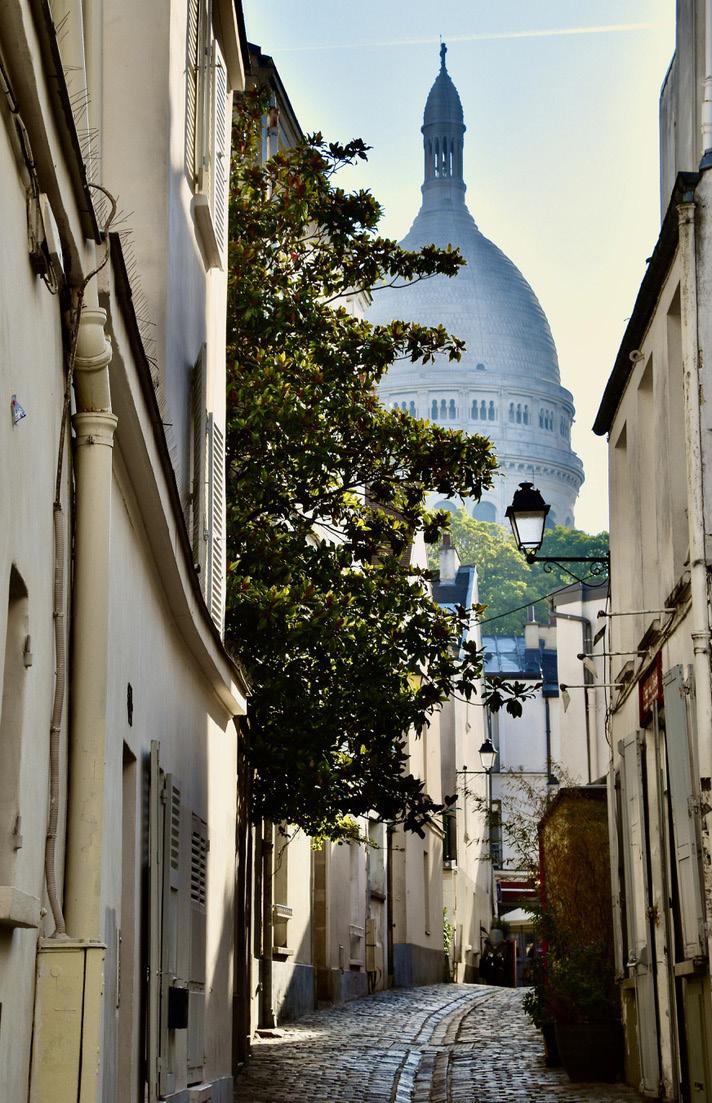

On the Left and Right, we see the Rue Cortot as it is today and as Maurice Utrillo painted it over 100 years ago. Below, we find the Sacré-Coeur, as captured by Utrillo in 1944 and by a tourist in 2021. Present day images courtesy of The Modern Postcard.