5 minute read

Views from the Salmonier Park boardwalk

Visitors appreciate the park’s work to foster local wildlife

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY DARCY RHYNO

It’s home to many animals, but Salmonier Nature Park in Eastern Newfoundland isn’t a zoo. As the main facility for the Newfoundland and Labrador Wildlife Rehabilitation Program, its goal is to care for and release injured and orphaned animals back into the wild.

“They know the best way to benefit the animals,” says visitor Aaron Power, who first came to the park as a kid. Now, the park’s unique characteristics draw his family here once or twice a year. Power is a teacher in a middle school near St. John’s, so he also leads school trips.

“It was a good day,” he says of his most recent visit with his two kids. “We saw just about all the animals, some of which we hadn’t seen before, such as the woodchuck.” Sometimes, they don’t see many animals. In those cases, he says, it’s more of a nature walk on the three-kilometre trail. “If people are aware of what the park is used for, they’re more appreciative when not seeing all the animals all the time.”

The park opened in 1978 as an environmental education centre. Today, its priorities are wildlife rehabilitation, research, environmental monitoring, animal welfare, and education. Of the park’s 40,000 annual visitors, 5,000 are Newfoundland kids learning about the island’s flora, fauna, and ecosystems.

Setting off along the boardwalk, I follow the trail through dense thickets of young firs and open, mature forest bearded in moss and lichen. Across the shaded expanse beneath them, woodland plants like bunchberry and fern spread in carpets of green. As I walk through these shaded groves, I look for the park’s wildlife.

The first enclosure, designed more to protect the animals than to confine them, houses a lynx, but there’s no sign of it. The shy cat could be snoozing inside its house or recovering from injury. Other animals just happen to live around here. Settled in a patch of fresh grass, a snowshoe hare nibbles green shoots. It must feel safe living near predators like the lynx because it doesn’t flee when I lean over the railing to take its picture.

Further along the boardwalk, I find enclosures for mink, peregrine falcon, and woodchuck. “It was the first time we’d seen the woodchuck,” says Power.

“The kids were impressed by its shape, much plumper than they expected. It came out of its hole and nibbled some lettuce. They found that fun.”

Other animals live in wide open spaces. When the boardwalk leads over a marsh to a babbling brook, I spot bald eagles, their white heads glowing against the greenery. They don’t fly away because they can’t. One has a broken wing, so it will live out the rest of its life here, surveying its private wilderness and catching the odd frog and trout from the stream.

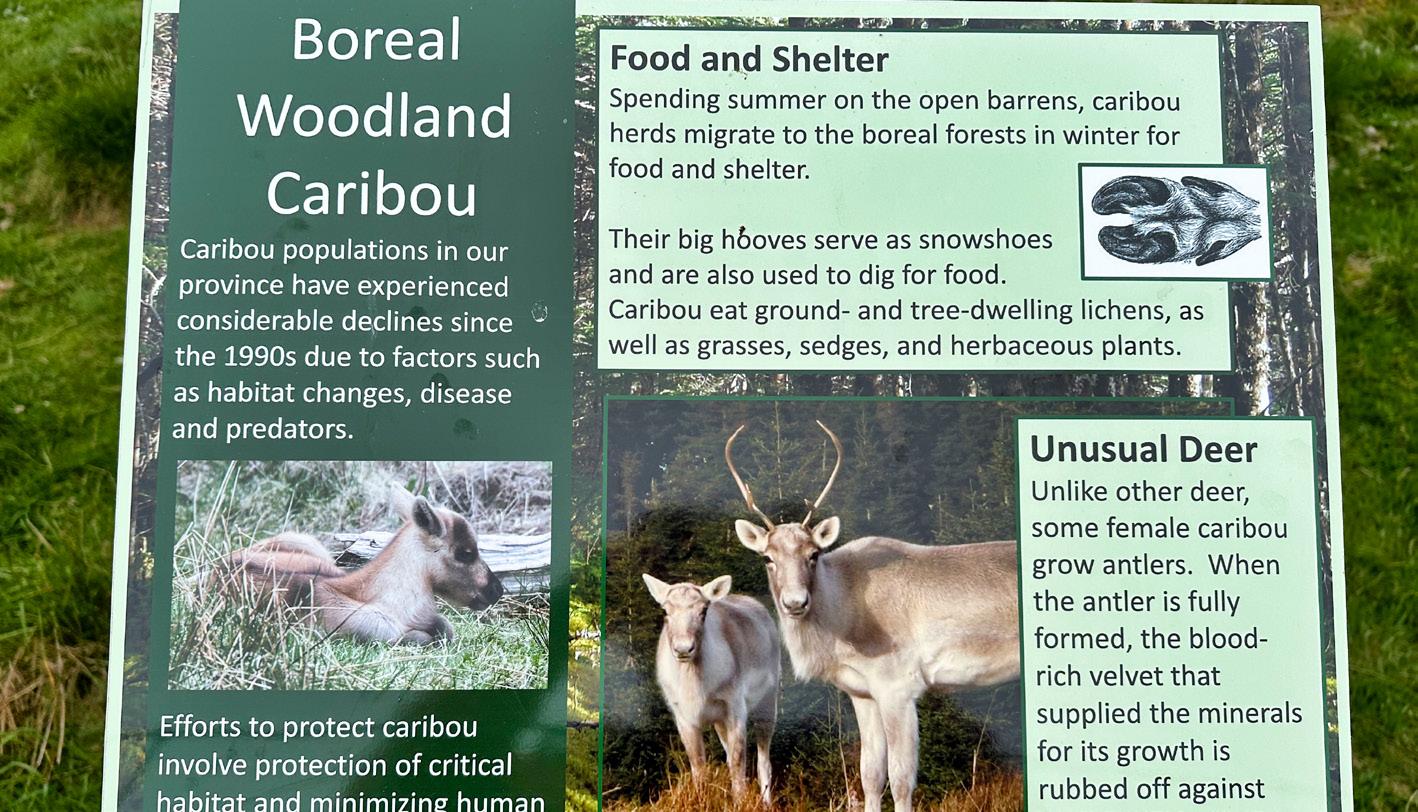

The largest animals are near the end of the trail. In enclosures so large I can’t see where the fencing ends, I spot a moose standing in the open. In the next, two woodland caribou lay in a grassy field, their antlers covered in soft velvet, slowly chewing their cud. It’s a privilege to be in their company, seeing them as relaxed as in the wild, and yet well cared for.

Salmonier has always taken its caregiver role seriously. Park staff were involved in the recovery of the Newfoundland marten. About the size of a cat, it looks like a cross between a mink and a weasel. Its round brown ears are set against a distinguishing orange patch on its throat. The marten that lives at Salmonier is from a captive breeding program.

“We’ve seen the Newfoundland marten before,” says Power, “and it was particularly active. It was going up the fence and really running around, putting on a bit of a show.”

In 1996, with about 300 individuals left, the National Committee for the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada declared the Newfoundland marten an endangered species. By 1999, a first litter was born at the park. Some were released at Terra Nova National Park, and biologists are now seeing marten living beyond its borders. At last count, they number 556 island-wide, a total that removed them from the endangered list.

Just before the end of the trail, two juvenile Canada jays flit out of the trees to land on the boardwalk railing for a closer look at me. In youthful black rather than the more formal white, grey, and black plumage of adulthood, they seem fearless, as if to communicate that this is their woods, and I’m just some exotic creature from a faraway place, on display to satisfy their curiosity.

Southwestern Sweet Potato Soup

This flavourful soup by Chef Barrie Hall makes a nice starter for a trout dinner at the Wilds Resort in Salmonier, N.L.

Ingredients

¼ cup (60 mL) vegetable oil

2 large onions

4 garlic cloves, minced

4 cups (1L) vegetable stock

2 large sweet potatoes, washed, peeled and diced

1 chipotle pepper

¼ tsp (1 mL) cinnamon

1 tsp (5 mL) cumin

A dash of adobe sauce

Instructions

Place large stock pot over medium-high heat. Heat the oil and add onions. Stir occasionally, allowing onions to become golden brown. Add garlic and continue stirring. Add broth and turn pot up to high. Once broth comes to a boil, add remaining ingredients, turning heat back to medium. Add a dash of adobe sauce, if you have it. Let soup simmer, stirring occasionally. Once potatoes soften, carefully blend soup using immersion blender. Garnish with sour cream or yogurt.