6 minute read

RETRO DESSERTS REBORN

Although we are always longing for the newest and trendiest desserts, it’s the old time favorites that never disappoint. Dust off your family recipes and bring back some vintage favorites to share for the holidays. Here is a blast from the past with a few retro desserts.

Ambrosia

A spin on a traditional fruit salad, ambrosia brings a little sweetness to the mix. Ink Foods brings this old favorite back to life by combining fruit cocktail, pineapple, mandarin oranges, marshmallows, nuts and coconut to make a fresh spin on this retro dish.

GROCERY LIST:

8-ounce package of cream cheese

2 cups sour cream

1 cup fruit cocktail, canned

1 cup fresh pineapple, chopped

1 cup mandarin oranges

2 cups marshmallows shredded coconut, garnish chopped walnuts, garnish maraschino cherry, garnish

DIRECTIONS:

Allow cream cheese to come to room temperature before mixing with sour cream; stir until smooth.

Drain juice from fruit cocktail and mix in the chopped pineapple and mandarin oranges before adding to cream cheese mixture.

Once fruit and cream cheese is combined, gently stir in marshmallows. Spoon into serving dishes and top with shredded coconut, chopped walnuts and a maraschino cherry.

Refrigerate until ready to serve.

BAKED ALASKA

A classic ice cream bomb layered over a cake flavor of your choice makes this an all-time favorite. Keeping the ice cream frozen will be the key to covering the top in meringue and baking before serving.

JELLO MOLD

An American classic, Jello can be found in a vast amount of old-time desserts, including a classic Jello mold. With so many flavor options for every season, this recipe must be brought back to stay. Combining peaches, peach Jello and condensed milk is the perfect way to start.

They are, at least theoretically, the grandchildren of the Greatest Generation.

They’ve witnessed bloodshed and shouldered responsibilities unfathomable to even the most sympathetic civilians. They were not drafted, but chose lives of sacrifice, relinquishing the relative security and unimpeded educational opportunities enjoyed by most of their peers.

Veterans are struggling. Those we interviewed can rattle off stats (backed by the Department of Veterans Affairs): A million servicemen have been diagnosed with at least one mental illness, 22 veter- ans per day take their own lives, 63,000 are homeless on any given night.

While so many are suffering, many also are working hard to build-up their families, communities, careers and fellow vets.

Like their World War II predecessors, this generation’s legacy will be as much about their contributions after war as their bravery in combat.

It is that post-war purpose — in addition to the love and support of family and community — that keeps these Lake Highlands veterans alive and, despite some personal battles, thriving.

“I wasn’t carrying out the most dangerous duties. That was the 19 and 20 year olds, a lot of the time. I saw a few explosions and sniper fights. But they were in the middle of it everyday.”

Jeff King

Full story, page 30

Jeremy Marx’s unit endured such bad luck, they dubbed themselves The Voodoo Platoon.

If a helicopter crash in Afghanistan didn’t take them, a car wreck or suicide often did, Marx says. He is able to say this sort of thing without obvious emotion, but the keepsakes around his Lake Highlands home expose his heartache.

He’s pulling memorabilia from drawers and cabinets when he stops and furrows his brow.

“Where are Jason’s dog tags?”

He disappears from the room.

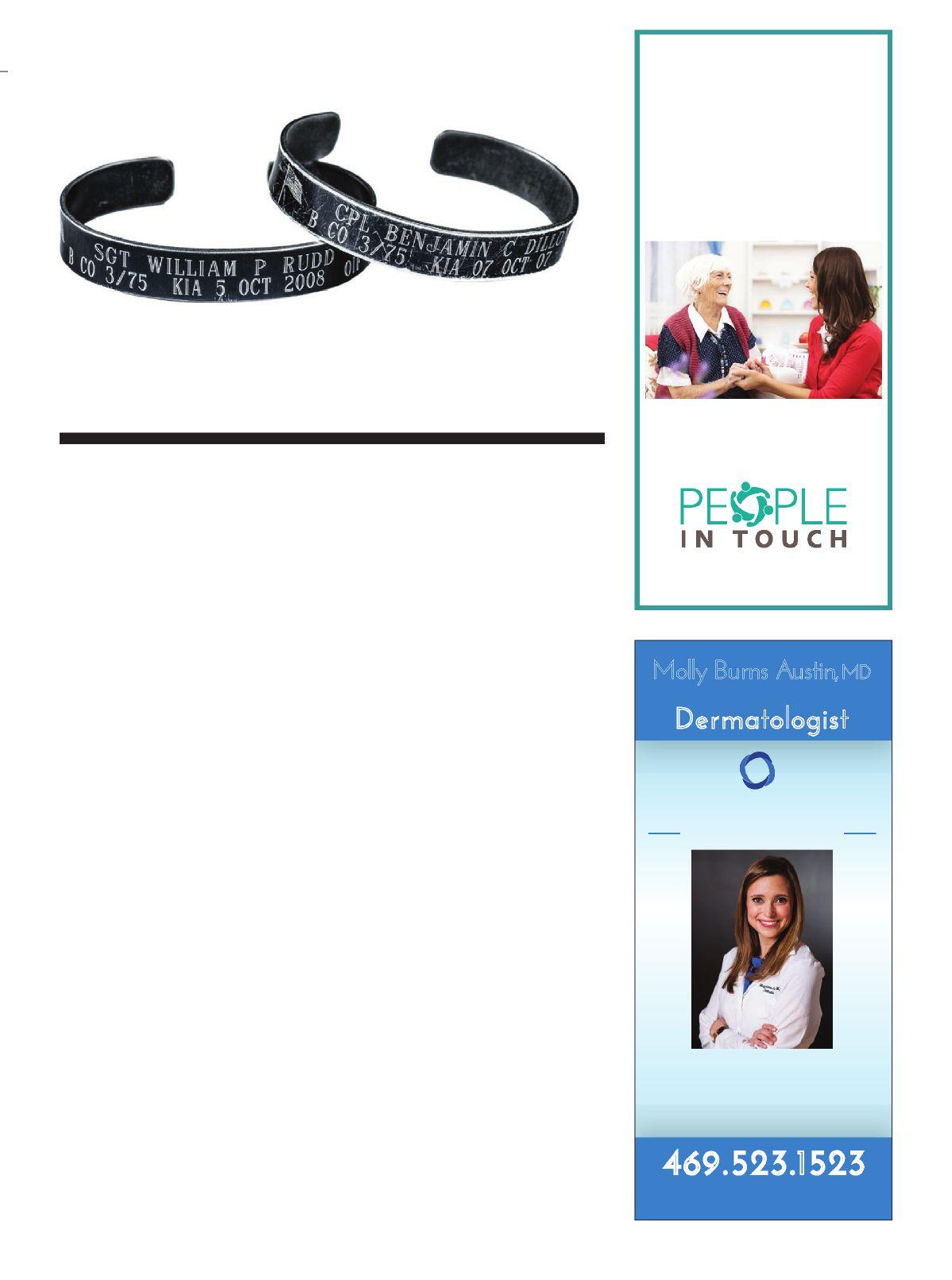

“Some things got lost in the move,” Jeremy’s wife, Jessi, offers, by way of explanation. A few minutes later, she seems relieved when Jeremy returns clutching a chain attached to an ID that displays the name Jason Santora. Jeremy places it alongside two bracelets with William Rudd and Ben Dillion’s names, birthdates and Killed In Action (KIA) dates respectively etched into them.

They are mementos from a few of the many buddies Jeremy has lost since becoming an Army Ranger and medic in 2004.

The men he fought with were his brothers, but Jeremy wound up in the same platoon as his biological younger sibling, Bryce (now an investment fund analyst in New York City), a rarity.

Jeremy is four years older, but his preparation, which included advanced training for Army medics, the Ranger indoctrination program and Special Operations Combat Medical School, took substantially longer. So the brothers were assigned to the 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment right around the same time.

It was interesting, recalls Jeremy. For one thing, it meant filling untold hours with a person with whom he’d already lived most of his life. “You spend every waking moment together. I got married around that time, and for the first three years, I spent more time with those guys than with my wife.”

Also, it can be difficult to be responsible for the health-care of people you love. It’s why doctors don’t operate on family members.

“It was hard enough treating the guys in my platoon, who were like brothers.”

Still, the brothers deployed together several times.

Bryce knows the situation weighed on his brother. “I was the younger brother for one. I also was the guy kicking in doors. I mean, we were in the same place, but I am sure he, as a medic, thought about it more.” It was nice to have someone there to vent to when things grew stressful, Bryce adds.

One night in Afghanistan Jeremy received word that a soldier was shot in the face. The wounded man was initially unrecognizable. Could it be Bryce? It wasn’t, though Bryce says he was nearby and will never forget it.

“I specifically remember the sound of Jeremy’s voice as he worked on our buddy. You could hear the anxiety in his voice.”

Their regiment regularly pursued and frequently obliterated high-value targets, and they were officially commended for their efforts. But they earned nicknames (they had multiple) like Bad Luck Detail.

Their hairiest tour featured a storm of gunfire, IED explosions, the death of a squad leader — and that was the first week.

“I treated 35-40 casualties in less than 100 days,” Jeremy recalls.

The wellbeing of his brother taxing him, Jeremy finally asked to be moved to a different section of the unit.

Jeremy enlisted after he graduated from Lake Highlands High School in 2002. He received a Falcon Foundation Scholarship and enrolled in the Air Force Academy. But after the 2004 death of Pat Tillman, who famously quit the NFL to join the war, Jeremy dropped everything to sign up.

There was a sense of urgency, he explains. He did not know the war would go on another decade, plus.

In between deployments, Jeremy married Jessi, and their daughter, Caden, was born. Having a baby made deployment harder, Jessi says. “I grew up in a military family, so I knew what to expect, but when you have a child saying, ‘Where’s Daddy?” it makes it a little harder.”

Later in his Army Ranger medic career, Jeremy began experiencing back pain. Doctors diagnosed degenerative disc disease. During his last couple of deployments, he worked in an administrative role.

Today, after scoring in the 91st percentile on his MCAT, he is preparing to enter medical school, where he plans to focus on traumatic medicine.

“I still have ideas, once I am board certified, of going back overseas,” he says.

He recounts the night one of his fellow Rangers was killed — after treating a profusely bloody torso wound, Jeremy got the man to the hospital.

“I remember handing him off to the surgeon. I think I could be that guy who saves the injured soldier,” he says. “I could see myself working in a war zone hospital.”

Jeremy says his faith keeps him sane in the wake of so much suffering. So do the strong relationships he formed in the service.

“The Rangers I’ve become close to will be friends for life,” he says.

Jeremy and Bryce were fortunate to have the support of family and community, they say. It allowed them to come home and live productive, meaningful lives and help others.

Jeremy’s greatest fear is that those who died will be forgotten.

“There are more names than I can list right now — we lost a lot. Guys died in combat. Others came home — some committed suicide, one died in a car wreck,” he says, adding that the same qualities that drive a person to service might also steer them toward destructive situations. “I wonder if they will be remembered.” he says. He gestures to his collection of keepsakes. “I keep these things so I will remember what happened. I want people to remember.”