25 minute read

A Mt. Baker Circumnavigation Jeff List

A Mt. Baker Circumnavigation

Story and Photos by Jeff List

Advertisement

As I stumbled down the rocky Swift Creek Trail in the dark, every side creek, ravine, and small gully was simply gushing—all tumbling into Swift Creek in the valley bottom below. Soon I would have to ford this creek at a notorious crossing, and my apprehension was on the rise—was it my imagination or did Swift Creek sound louder every time I passed a feeder stream? felt kind of lost until my son suggested I do a circumnavigation of our local active volcano, Mt. Baker. It immediately sounded like a good idea. I’ve always liked circumnavigations. I’d completed the Wonderland Trail around Mt. Rainier several times, negotiated the partially

I was 22 hours into a circumnavigation of Mt. Baker and I just couldn’t entertain the thought of turning around and climbing 4,000 feet back up to Artist’s Point to bail. But luckily it got light just before arriving at the ford, and making no effort to find the best place to cross, I just plunged right in and nearly found myself swimming across a deep pool. I crawled out on the far bank. Sweet! The last major unknown was behind me!

When the Hardrock Hundred Endurance Run that I had been training for was abruptly cancelled in June, I had Skyline Divide

off trail loop around Mt. Adams, and had been working on a loop around Mt. Olympus for six years and counting. My kind of circumnavigation is entirely on foot (no skis, no bike), with no glacier travel and no rock scrambling harder than a moderate class 3. In other words, reasonable for solo travel within my own personal comfort limits. Had such a Mt. Baker circumnavigation been done before? Extensive internet searching and talking to knowledgeable locals turned up only one previous effort. In 2007 David Hess and Doug Shepard completed a very difficult loop in a total of 25 days, 11 hours, which included a two-week break to recuperate from the tremendous beatdown they endured. The aesthetics of their route seemed to dictate very little trail or forest road, staying as close to the glaciers as possible while traversing an endless series of devil’s club-choked gullies, extremely steep slopes, and difficult river fords.

I didn’t want to suffer nearly as much as Hess and Shepard, and I definitely didn’t want it to take as long, but could it be done more easily? I had spent countless hours on the computer with resources Hess and Shepard never had, and had made six trips to the mountain to piece it together. My route would be a compromise between Hess and Shepard’s aesthetically pure route that traversed mostly just below the glaciers and a route

that might drop down to major roads to avoid sections not connected by trail. Recon days focused on the off-trail sections where I would have to climb or descend 4000 feet between forest and alpine, as well as alpine traverses where the slope maps promised a challenge. Almost miraculously, every recon trip was an amazing success. I encountered no particularly tough bushwhacking, no significant devil’s club, and there had always been a fairly easy way to thread through the cliff bands and steep gullies once I learned the lay of the land. I could hardly believe it—the game was on!

Although there were still three major alpine cross-country sections I hadn’t previewed, I took a chance that it would all work out and started the circumnavigation clockwise from the Ridley Creek Trailhead at 6:08 a.m. on July 20, 2019, heading up the switchbacks of Forest Service (FS) Road 38. At the end of the drivable road, I took an unofficial, very steep trail straight up to treeline on what I call Rankin Ridge (because it’s next to Rankin Creek). Finding this trail during a recon day had been one of the many unexpected gifts of the route—Hess and Shepard had Circumnavigation Route

suffered a difficult bushwhack to reach treeline here. I then traversed northeast uphill and cross-country through heather meadows and talus slopes to the edge of a small glacier coming down from Seward Peak, part of the looming Black Buttes extinct volcano range. A most spectacular spot! From here I had about three or four miles of alpine crosscountry travel, unpreviewed. Terra Incognita. First, I had to get down a steep snow slope with some rocky runout, which was a little tricky with the snow still frozen from a cold night (I didn’t bring crampons). With some care I was soon traversing a huge bowl directly under the Black Buttes. Crossing the outwash of the Thunder Glacier, I came across a piece of riveted aluminum, which likely washed down from the remains of a Navy plane that crashed into the glacier in 1943, killing six, but hadn’t

Stay Where the Birds Are! Semiahmoo.com

Photo by Eric Ellingson

March 20, 21 & 22, 2020 B L A I N E • B I R C H B AY • S E M I A H M O O WASHINGTON

Join Us! Observe a spectacular variety of birds along the Northwest coast of the Pacifi c Flyway!

For more information about lodging and activities, visit www.BlaineChamber.com Contact Info: 360-220-7663 or wingsownw@gmail.com

been found until 51 years later when the glacier finally gave it up.

I jogged down the only paved part of the loop, 3.7 miles on FS-39, Glacier Creek Rd, and exited at abandoned FS3940. I would have loved to eliminate this paved part of the route, but the options were limited by some very rough topography between the Heliotrope Ridge Trail and Chowder Ridge, and a potentially dangerous ford of Glacier Creek. Hess and Shepard took about 12 hours (not including a night’s sleep) to travel about four miles between the Heliotrope Ridge trail and Chowder Ridge, while my route took about five hours and covered eight miles. Twice the distance, but way easier.

After bushwhacking up to the base of Chowder Ridge and traversing the Deadhorse Creek valley over to the Cougar Divide, I was back on trail again! Or at least abandoned trail. The Cougar Divide Trail is going back to nature now that the long access road to the trailhead (FS-33) is closed. It’s still not hard to follow, but without any maintenance, it Headwaters of Wells Creek, below Coleman Pinnacle

won’t be long before it’s another lost trail. The Cougar Divide Trail is not quite as scenic as the nearby Skyline Divide Trail, but still has fantastic views of Mt. Baker from another angle, and it would be a shame to lose it.

At the Cougar Divide Trailhead, I had a seven-mile road walk down abandoned FS-33, still mostly a good dirt road but soon to be overgrown and covered by blowdowns and slides if it isn’t maintained. The huge switchbacks on FS-33 could possibility be shortcutted through the woods, but without previewing it I couldn’t risk encountering tough bushwhacking. At the bottom of FS-33 I crossed a bridge over Bar Creek, impassible to vehicles due to a washedout ramp on one end, and ended my road walk near the base of Lasiocarpa Ridge.

My off-trail route up Lasiocarpa Ridge started with a short brushy climb to gain the ridge, but for most of the next 2000 vertical feet, the going was amazingly easy through an old-growth forest with little ground cover. It did get extremely steep in parts, but at those points animals helped me out with nice switchbacked trails.

It got dark during the steep climb through the big trees, and my plan to get back on trail before nightfall was way off target. Two glowing eyes ahead gave me a momentary adrenaline rush but it was just a deer.

The knife edge crux is a 10-foot scramble down broken rock through tree branches, right next to a full- on cliff. I was definitely grateful that I’d previewed this part so I wasn’t fumbling around in the dark here. This is another spot where the route could have easily failed, but nope, another lucky passage. Soon after the knife edge, the route broke into heather meadows, and there’s nothing as welcome as seeing your first heather after a long uphill bushwhack!

After a bit of side-hill scrambling over large talus and moderate gullies, the route now opened to a traverse of the upper Wells Creek Basin, just as the waning moon rose over Ptarmigan Ridge. On the recon hike there had been a low overcast and now it was pretty dark, but the moon was bright enough see what a grand place it is. I look forward to really seeing it someday. I hadn’t previewed the connection between Wells Creek basin and the Ptarmigan Ridge Trail, but it turned out to be pretty easy even by headlamp, and I had now done all the off-trail sections I hadn’t previewed, another big step! From the Ptarmigan Ridge Trail, Mt. Baker glowed in the moonlight behind me, showing yet another of its many faces.

The Ptarmigan Ridge and Chain Lakes Trails took me past sleepy Artist’s Point, and the Wild Goose and Lake Ann Trails put me on the Swift Creek Trail, which can be terribly bushy but by luck had just been cleared. After a bit of unnecessary worry about water levels, I welcomed the daylight, now past the last route uncertainty, to rest at the Swift Creek Ford, and ended this long trail segment at the Baker Hot Springs parking area.

From there, I had a seven-mile walk on unpaved and pretty deserted Forest Service roads, with a 20-minute nap at an irresistible spot bathed by early morning sunlight, to arrive at the Boulder Ridge Trailhead. The many large blowdowns on the Boulder Ridge Trail had just been cleared—what, was there a whole team of unseen people clearing my circumnav route just ahead of me?! It had been foggy during the

• July 20-21, 2019 • Time: 38 hours, 13 min, 32 sec. • Mode of travel: solo, • Unsupported Distance: 71.6 miles • Vertical Gain: 22,753 feet • Calories consumed: 5,400 • Sleep: 20 minutes • Footwear/tech gear: Inov-8 Mudclaw G 260 shoes, two Whippet poles • Surface traveled: 41% Trail, 31% Road (3.7 miles paved), 28% Off-trail

recon, so at the top of the trail I got my first view of Mt. Baker’s twin peaks, the Boulder Glacier, and the route ahead. The first obstacle upon leaving the trail was getting across Boulder Creek. During the recon I had forded immediately without difficulty, despite a waterfall about 100 feet downstream. But on the circumnavigation the creek

was running too high to cross safely here. Later I compared photos from the recon and the circumnavigation, and the creek was running at exactly the same level! I guess 30 hours of tough mountain travel can influence risk assessment. But I had checked out easier fording spots upstream during the recon, anticipating a problem here, and I was on my way after crossing Boulder Creek without much trouble.

After another fairly easy contourfollowing traverse, I hit the climber’s trail for the Squak Glacier route up Mt. Baker. I had no map, either paper or on my phone, that showed how the climber’s trail connected to the Scott Paul Trail, but I knew it did and I just kept following it down until it connected. This cost me about a mile and maybe 400 feet of extra elevation gain, but I didn’t care—I was happy to be home free on trails now.

After seven more miles on the Scott Paul, Park Butte, Bell Pass, and Ridley Creek Trails, I finished the circumnavigation just before dark. It was sort of a surreal experience to walk up to my truck from the opposite direction than I had left it the day before, having looped all the way around Mt. Baker. Although it took over 38 hours, it was far easier than I could have hoped when I started the project. But I was still beat and the night was spent crashed in the back of my truck. In the morning I headed down to the Acme Diner for blueberry pancakes – but they’re closed on Mondays. ANW

I’m not going to make my full GPS track publicly available. Anyone wanting to do a Mt. Baker circumnavigation should figure out their own exact route and have solid off-trail experience.

This article is a shortened version of my original account which can be viewed at: https://sites.google.com/site/jeffstrailroutes/ Home/mt-baker-circumnavigation

For Your Next Adventure, Pick Up Some

BAGELS Light enough to carry with you, hearty enough to keep you going!

Bloom

Therapeu�c and Prenatal Massage

lymphatic

fertility prenatal

Mon-Fri: 7:00 am – 4:00 pm Sat: 7:30 am – 4:00 pm • Sun: 8:00 am – 3:00 pm 360.676.5288 1319 Railroad Ave, Downtown Bellingham NOW ACCEPTING VISA/MC

Specializing in fer�lity, prenatal lympha�c and therapeu�c massage in downtown Bellingham.

bloommassagebellingham.com 360.820.0334

Jenny Reid, LMT Melissa Herbst, LMT Ticker Ba-Aye, LMT

Notes from the Story by Abby Sussman and August Allen Photos by August Allen Arctic Circle Trail

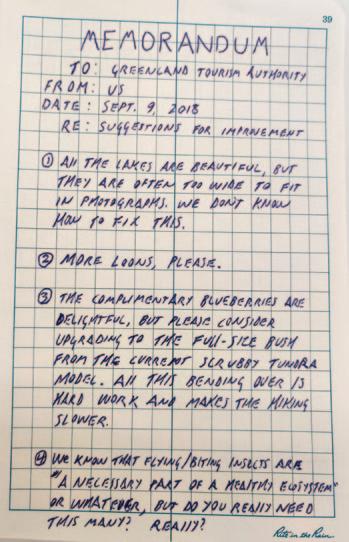

The Arctic Circle Trail (ACT) is a hundred-mile overland trek from the airport town of Kangerlussuaq to the fishing village of Sisimiut in west Greenland. It traverses from the edge of the Greenland ice sheet to the outer coast over a rolling landscape of Arctic tundra. We hiked it in August 2018.

Here are a few notes from our journal on the trip. running under a natural ice bridge, as well as exposing some beautifully tortured granite bedrock. Wary arctic hares browse around while we pack up. How on earth did two Americans from the Pacific Northwest find themselves at this unlikely place? A bit of background: A series of connections and coincidences connected us with shortterm jobs at a remote research facility on the top of the ice sheet. We worked at Summit Station for just a month, an unusual contract that finished in mid

Day 1 (by Gus)

After a long day of preparation and logistical comedy, we score a bumpy shuttle ride out of Kanger, up a long sandy road to the edge of the ice. Our first camp is near the massive ice wall of the Russells Glacier, actually the toe of a relatively miniscule offshoot of the unimaginably huge Greenland ice sheet. We cook rice and lentils under a stunning pink 11 p.m. sunset. We take several hours in the morning to explore this unique spot before properly beginning our hike. The retreating edge of the glacier is in constant flux. It has created a waterfall August, before the high-latitude weather turned and made adventures like this decidedly chillier propositions. Since the company provided travel from the States, we were able to afford a trip that is made cost-prohibitive to many by limited and The rule of thumb in Greenland is that if you can see the water, it is safe to drink

pricey flights to and from Greenland.

After several hours of rainy hiking away from the ice, we encounter our first muskox. A herd of seven, with two calves. The wooly ungulates eye us from the top of a hill, but allow a good look before they wander away. These holdovers from the ice age are an important part of the local economy. Their inner wool, called qiviut, is one of the softest, warmest natural fibers found anywhere. Apparel knit from qiviut is highly prized. Locals and international sport hunters also take muskox for meat. We hear it tastes like bison. Observing these gentle creatures with their hanging shaggy coats and upturned horns, suckling their young, grazing on lichen and sparring with each other, suggests a portrait of ancient Greenlandic tundra from long before humans arrived here from northern Canada.

The route transitions from sandy road to the thick tundra mat which soaks my (theoretically waterproof) shoes and makes our progress slow. At the end of the day we ascend to a high point on the ridge and set up the tent. We watch sheets of rain obscure the terrain in all directions while Abby cooks

pasta over the PocketRocket. Our dessert is the same every night–we have arrived at the height of blueberry season. At 5 a.m. we can no longer ignore the bright sun lighting up the tent, so we rouse ourselves with coffee and half

Day 4 (by Abby)

As someone who reliably needs to stumble out of the tent for a midnight pee, the starry night sky is a new and welcome experience from the 24-hour daylight of the last few weeks. Gus is happy that I shake him to take a look, even if it means momentarily allowing the frigid arctic air to invade his sleeping bag. At this time of year the daylight shrinks by about 20 minutes each day, so today we get sundown at 10 p.m. and sunrise at 3:30 a.m. heartedly tend to packing up. This isn’t our first long trip together, so we easily navigate the tasking without much need A bachelor group of muskox tolerates each other’s company

BOARD?

wE havE all kiNDs.

kitE, surF, wakE, FOil aND

paDDleBOarDs - wE’vE eveN

gOt wEtsuits, aCCessOries

aND sO MuCh MOrE!

for discussion–one of the pleasures of having a steady adventure companion.

The morning’s hike follows the south shore of Amitsorsuaq, a 12-mile-long lake, with banded cliffs on the far side reflected perfectly in the clearest water either of us have seen anywhere. We stop for lunch at the Canoe Center, a long-agoabandoned business venture with an impressive collection of jettisoned empty fuel canisters stashed away by other hikers. Trash removal is unfortunately a problem at all of the ACT huts. The guidebook mentions that canoes are sometimes available for use here, but we

360 775 2741 / kitEpaDDlesurF.COM

2620 N. HarBOr lOOp DR. #18, BelliNghaM WA, 98225

Cascade River House Relaxation and Tranquility at the Gateway to North Cascades National Park.

Enjoy a vacation home and luxury trailer on the wild & scenic Cascade River! World-class fishing, white water kayaking, rafting/floating, hiking, climbing and bird watching. Now Offering Outdoor Equipment Rentals!

Book Your North Cascades National Park Vacation Now! 360.873.4240 www.cascaderiverhouse.com

don’t find any.

I pull together a lunch of powdered peanut butter and crumbles of Danish dark bread, now a staple for us. We eat under a blue sky, but eye ominous clouds across the lake. We navigate through boggy territory at the lake outflow through a long narrow valley, ending our day on the shore of the never-ending lake Tasersuaq. That evening, a juvenile arctic fox circles our camp to investigate the smell of our tortellini before making pawprints down the beach away from us.

Day 5 (by Abby)

Paddy Dillon is a prolific author of trekking guidebooks describing routes all over the world

An early start lets us leap-frog a British hiking club of about 12 members as they break down their camp at a beach just over the next bluff. With that crowd behind us for good, we climb towards a series of rocky outcrops that top out at about 1200 feet, the high point on the route. We suffer a stiff wind for a panoramic view of Tasersuaq before dipping down into a valley of small, interconnected lakes, terrain which feels like the subalpine of our home mountains, the North Cascades. We find ourselves overlooking the wide valley of the Itinneq River, and we need to choose between camping early and pushing hard to ford the river and move out of the lowland to the next hut. We elect to push; it’s sunny now and it might not be tomorrow. The river is waist-deep and icy, but the crossing proves simple and our travel underwear benefits from the rinse.

We end our

day walking along a small rocky ridge that leads us to the head of a fjord before gaining the last of the day’s elevation. Arriving at Eqalugaarniarfik Hut (Sound it out: Ee-Qua-Loo-Gar-NeeArr-Fik), we find a cast of characters packed like sardines in the bunks of the cozy space. Among them is none other than Paddy Dillon, the British author of the one and only Englishlanguage guidebook on the Arctic Circle Trail. He is back in Greenland after ten years to make updates. Our copy of his book is the Kindle edition, so he regrettably can’t sign it. He waxes about trekking on the Faroe Islands, the Azores, Malta. He may like to talk even more than he likes to walk. The ACT doesn’t see nearly the volume of traffic we have experienced on the trails in the U.S. We have seen estimates of perhaps 1,500 users per year, which seems plausible. This is the peak of the season, however, and the huts show the strain of relatively heavy traffic. Even in winter, the route sees use by dog mushers, so the huts are frequented year-round. There are no pit toilets or outhouses. Hikers are expected to bury their waste. Used toilet paper is a particularly pernicious issue; we suspect it’s largely left by winter users who are simply unable to bury it properly in the frozen ground. We find nearly all the huts to be just a little

gross, so we mostly avoid them and pitch our tent in more private locations. On this evening however, we elect to cook our instant mashed potatoes and lentils indoors, and engage in a little human conversation. Being out of the rain is a pleasant respite. Day 9 (by Gus)

The Best Campsite Ever™, a flat rock platform with an indescribable view of nearly the entire fjord a thousand feet below us. I spread out all of our soggy gear (nearly everything we’re carrying) to dry in the sun while Abby makes us tea using rainwater from a hollow in the rock. As the sun threatens to set we

Hard rain traps us in the tent overnight for a solid 12 hours. When we finally emerge, the whole world is a soggy mess and there is fresh snow on the tops of the hills no more than a few hundred feet above us. The trail is so muddy that I abandon my hiking shoes entirely and slog the four-ish miles to the end of the valley in my Crocs. My feet go numb several times, but the stream crossings are greatly simplified.

Gaining a rise at the bottom of the valley gives a sweeping view of Kangerluarsuk Tulleq fjord. Sparse seaside cabins dot the far shore, the first sign of non-recreational human occupation since Kangerlussuaq.

The route follows the south shore of the fjord by traversing a steep and rocky hillside. Difficult stretches of mud make for slow going even here, where one might expect the steep terrain to allow good drainage. Toward the end of the day we ascend a gulley, passing the best waterfall on the trail since the cascade at the edge of the ice sheet, a lifetime ago. Near the top of the climb, we leave the trail and bump over a couple of rock ribs, where we locate

POETRY FROM THE WILD

Everything Moistens With Love by Jim Bertolino

Somewhere the proposition that heals with a caress of eagle feather,

that pulls a mountain range through the wing-bone of a wren to let it blossom.

Look for the endless forms of the one thing: sunflower as cougar’s eye, glacier, underwater spider with its bubble of air, slow river of snail, spiral nebula – the way everything moistens with love, hastens with fire.

Listen to the shrill piping of silica inside the high Douglas Fir. Hear everywhere the electron’s Bright chirp, and the deep hum Of the Earth calling you home.

Sweeping views of tundra make the landscape “feel” high to our mid-latitude sensibilities, belying a low true elevation. No point on the ACT is above 1300 feet.

cook our last trail meal: Tortellini with sun-dried tomatoes, with red sauce from a tube of tomato paste. Day 10 (by Abby) As on any good trek, seeing signs that we’re nearing the end brings both a relief and a bit of sadness: our Greenlandic adventure is nearly over. The route descends through the narrow head of a valley and passes a single chair lift strung out on a bare hillside. There is no road here so we imagine an incongruous scene of snow machines, tracked vehicles, and dogsleds parked at the bottom of the ski hill while locals snowplow and slalom in the dark winter.

BUILDING CONFIDENCE Girls on the Run For girls in grades 3 rd

- 5 th Season begins March 23 rd

. Register today!

www.gatoverde.com 360-220-3215

• Multi Day Adventures • Sunset Cruises • Day Trips

Low Guilt Wildlife Viewing Aboard a Quiet, Sustainable Vessel!

Gift Certificates Available

The ACT stretches from the ice cap to Baffin Bay

In typical Arctic fashion, sled dogs are chained to small hutches on the outskirts of Sisimiut. We hear their racket from a distance before we see a single building. We walk through a small city of them lounging in the sunshine. A bark from one sets off a chorus and it is clear that nobody can ever sneak into Sisimiut from this direction. The valley finally opens to overlook brightlypainted buildings clustered on rocky hills surrounding a natural protected port filled with ships, leading out to shining Baffin Bay.

After ten days of muddy trails, river crossings, caribou, foxes, and few other humans, it is startling and not entirely comfortable to find ourselves on a busy street corner scratching our heads over our enormous trail map as we consult the tiny road inset for the way to a hotel. We eye restaurants advertising meal specials to hikers on our way through town. We are ignored entirely by the local Greenlanders, and receive only sideways glances from European tourists milling around in colored jackets; red from one cruise ship, yellow from another. The Seaman’s Hotel has exactly one tiny room left, with one twin bed and a bathroom shared down the hall. They wouldn’t normally rent this to a couple, but we cajole the clerk into wheeling a second bed in for us. We sip instant coffee and munch french fries in the cafeteria while they prepare the room, revelling in the simple joys of pack-free people-watching, indoor plumbing, and that ineffable satisfaction of an unlikely plan successfully executed. ANW

Check out an extended gallery of August Allen’s Greenland photography at AdventuresNW.com

Lighten Up - Tips for Beating the Winter Blues VITAL SIGNS

By Sarah Laing, B.Sc. Nutrition

This winter has been one of the rainiest I can remember since I moved to the PNW 15 years ago, and although the rushing waterfalls and lush greenery don’t hurt the eyes, being socked-in can come with challenges when it comes to your health. There are a few things in particular that can help steer us to a healthier and more positive place, one being the power of the ‘parkscription’ trend. Getting out into the incredible nature we have in our backyard never fails to make a gloomy day seem a little brighter,

not to mention the physical health benefits derived from going for a hike or hitting the mountain. We know that chemicals like serotonin, dopamine and vitamin D have something to do with it, but for me, the benefits don’t stop there. Getting outdoors also tends to prompt me to choose moodboosting foods such as lean protein, dark leafy greens, walnuts and kimchi, and instills a sense of accomplishment that might otherwise be replaced with low self esteem, a key marker of Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD). Whatever your activity of choice, getting a regular dose of the outdoors is one of the best natural remedies.