2 minute read

ORO Editions

from The Shape of Land

9-2

Robert Smithson. The Pumping Derrick. “The Monuments of Passaic,” Artforum (December 1967).

[Robert Smithson; © Holt/Smithson Foundation / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY]

9-3

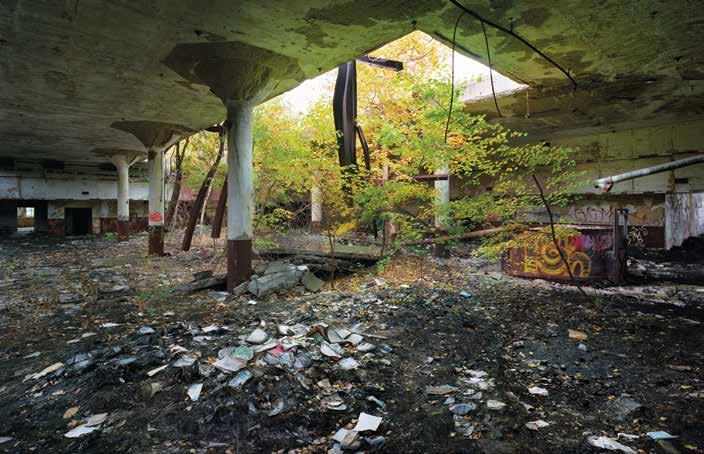

Andrew Moore. Birches Growing in Decayed Books

Detroit Public Library Book Depository, 2010.

[© Andrew Moore, from Detroit Disassembled]

With the shift from a production economy to a serviceoriented consumer economy, the abandoned sites of industry and disused infrastructure have become the new ground of our public realm. Parks built on the sites of empty blast furnaces; abandoned quarries; or decommissioned rails and railyards, landfills, and ports have generated a renewed fascination with industrial sites. Much has been written about the current “ruin craze,” which has sparked a voyeuristic interest in industrial heritage in ghost towns and waste sites, from Fukushima to Detroit.6 Ruins have become aestheticized and stripped of social context as sites for “ruin tourism,” destinations that today attract outsiders with no stake or interest in the city a trend derisively termed “ruin porn.”7 A new postindustrial aesthetic has come into focus, largely as viewed through the photographer’s lens.8

Many of the images of urban decay that feed this aesthetic draw upon romantic notions of inevitability, showing images of empty lots reverting to fields or trees sprouting in abandoned buildings [9-3]. Nature seems to be reclaiming the city as a powerful yet external force that exists beyond human life and history.

The conversion of these sites to public use has required landscape architects to think and work in new ways, transforming landscapearchitectural practice as well as its theories.9 To what extent do recent designs play to prevailing landscape conventions, such as the picturesque or the sublime, or even ruin porn and how do they challenge them? Geographer Matthew Gandy has argued that “urban wastelands unsettle the familiar terrain of cultural landscapes, designed spaces, and the organizational logic of modernity.”10 In response to these conditions an alternate aesthetic is emerging from recent postindustrial landscape projects marked by their engagement with terrain. Rather than focusing on the Romantic imagery of ruin, the key element in the remediation of these sites is the earth itself: disturbed, eroded, toxic soils; or oozing trash. In his 1973 essay “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape,” Smithson underscored the primacy of the earth: “a consciousness of mud and realms of sedimentation is necessary in order to understand the landscape as it exists.”11 He and other land artists working on reclamation sites in the 1960s and 1970s used earth as a sculptural medium to express a range of themes that ranged from disruption, devastation, and entropy (Smithson), to earth as “a thing in itself” used to support living systems (Helen and Newton Harrison).12

10-11

Studio AKKA

Grounds of the White Mansion. Bled, Slovenia, 2010. Topography enhanced by leveling.

[Peter Koštrun]

10-12

Studio AKKA

Grounds of the White Mansion. The sway of topography capped by a narrow platform directing the view.

[Peter Koštrun]