5 minute read

Preface – NEIL McKENDRICK

from The Bordeaux Club

Much of this literary interest in him stemmed from (indeed was often directly provoked by) his adventurous private life. His sex life alone was varied and often quite complicated. It rivalled that of our other titled member, Lord Walston, for complexity, if not for publicity.

Sadly, the many thousands of words on the wine he and we drank, which were faithfully and extensively recorded in his diaries, are not available to us because they are currently embargoed in the University Library until ‘the death of the youngest grandchild of Her Late Majesty the Queen’. The prohibition is partly because of indiscretions about the royal family, a result of his close friendship with Princess Margaret, but also because his diaries are interwoven with details of his private life and his friendships with both men and women, which he felt would be embarrassing to publish in their lifetimes.

Indeed, much of the early controversy about Jack’s life was a direct result of his alarmingly provocative love life. The two brilliant fictional portraits of him by William Cooper – one in the hugely well-received Scenes from Provincial Life (1950) and one in the equally highly praised The Struggles of Albert Woods (1952) – were both written in revenge by Cooper after Jack seduced (just for the fun of it, he said) one of Cooper’s lovers. They were devastatingly accurate insights into Plumb’s character. But the truth is that the story of Jack Plumb’s life needed very little fictional embellishment to make it unusually interesting.

Jack Plumb’s life began on one of the lowest rungs of the social ladder and ended among those on the highest. It started in a humble red-brick two-up-two-down terrace house in the back streets of Leicester. It ended among the smart set of London and New York and as a friend of the English aristocracy and a familiar of the royal family – invited to stay as a guest of the late Queen at Sandringham, invited to the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer, and frequently invited to spend holidays with Princess Margaret on the Caribbean island of Mustique.

If his life was a spectacular example of social mobility, he also enjoyed an equally remarkable rise up the career ladder, which ended with him as master of Christ’s College, with a knighthood, a Cambridge professorship and a fellowship of the British Academy, among many other accolades recognizing his academic distinction. He finished his career as a multi-millionaire, able to give away millions as a result of the huge royalties earned by his writing.

1

His political sympathies changed as dramatically as his financial fortunes. In the 1930s, he was an ardent communist sympathizer; in the 1960s, he was an almost besotted supporter of Harold Wilson and the Labour Party; by the 1980s, he had moved so far to the right that he often criticized his new heroes, Thatcher and Tebbit, as being ‘timid pinkoes’. When confronted with the appalled reactions of his old liberal friends, he smugly replied: ‘There’s no rage like the rage of the convert.’

His teaching career in Cambridge started as someone not thought grand or distinguished enough to teach Christ’s undergraduates and finished as the acclaimed mentor of probably the most remarkable stable of successful students and colleagues from any single college in either Oxford or Cambridge.

His war service, spent in code-breaking secrecy at Bletchley Park in Hut 4 and Hut 6, started in a scruffy anonymous wartime lodging and ended up in the house of the Rothschilds, where he spent his evenings drinking their finest First Growth clarets.

His writing career was so delayed that he was nearly 40 when he produced his first significant book, but so productive that over the next 25 years he published 44 books bearing his name as either editor or sole author. He was at the same time a hugely prolific journalist in both Britain and the United States. By then he had earned the reputation of being one of the most widely read living historians as well as one of the most well rewarded.

It was not only as a teacher and a writer that he excelled. It must have been a pleasing irony to him in his mature years that the aspiring writer who had had his first literary efforts rejected by editors and publishers alike should eventually come to control a dazzling portfolio of editorial appointments himself. Those appointments led to a huge array of significant publications with an impressive cast of distinguished authors and publishers.

As a result, he was able to enjoy an affluent lifestyle far beyond that of the average don. These were the years when he relished a pleasure-loving

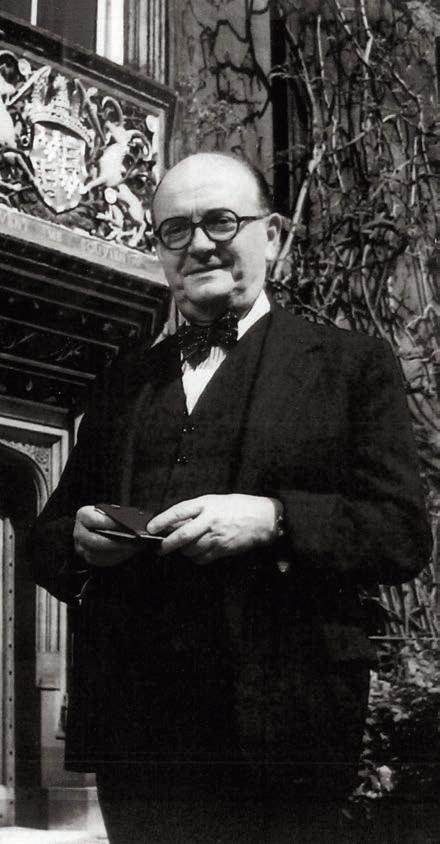

Professor Sir John ‘Jack’ Plumb

The many faces of Jack Plumb: as a research fellow at King’s College, Cambridge (1); with his protégé, a youthful Neil McKendrick (2); in an uncharacteristically benign pose as the Master of Christ’s College, Cambridge (3); and in later life with distinctive felt hat and cane in the garden of Hugh Johnson’s home, Saling Hall (4).

Sir John Plumb

NOVEMBER 13TH 1989, CHRIST’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE Sir John Plumb (host), Neil McKendrick, Michael Broadbent,

Harry Walston, John Jenkins – Harry Waugh was unable to attend and Dr Ingham of Christ’s College was invited to take his place

The first course was thought to be excellent by all but our host, who had apparently ordered something else. The partridge was unanimously agreed to be perfect. The cheese ramekins ware agreed by all to be a disaster – so peppery as to be inedible to anyone reared west of Bombay. The pears in red wine were perfect despite being described on the menu as La Tarte aux Pruneaux!

Everyone approved of the Dom Pérignon – good nose, good colour, good taste = good champagne.

The Corton-Charlemagne was a fine old white burgundy – a quality wine with a remarkably beautiful nose.

The clarets: the ’76 Mouton had few admirers – the dominant impression being of a curiously thin wine, excessively dry and tanninridden. What fruit there was seemed unlikely ever to escape the clutches of the tannin.

The next three clarets were magnificent. They were all so indisputably first class that it was largely a matter of taste which one put first. I put the Haut-Brion ’53 first, the Pétrus second and the Margaux third, but the general view was that, although the Haut-Brion must be first, the Margaux beat the Pétrus. I did not know at that stage that I would be asked to produce some minutes, so my notes were as economical as they were ecstatic – ‘Margaux – fabulous; Haut-Brion – amazing; Pétrus – a superb surprise’. The surprise about the Pétrus was mainly that a 1950 could be so good, but it was also encouraging (after some of our recent problems with English bottling) that this Avery-bottled Pétrus should be such a glorious success.