12 minute read

The First Written Accounts

from Tattooed History

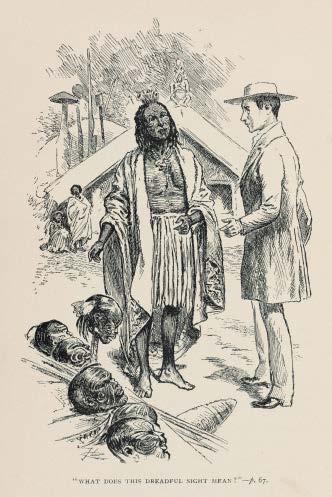

Samuel Leigh was a Wesleyan missionary in New South Wales and became an acolyte of Marsden. He spent a month in the Bay of Islands in 1819. Leigh entered a village and saw twelve heads displayed along a path. Leigh asked the chief why the heads had been displayed in this manner:

“Because I expected you to buy them!” “Buy them!” said Mr. Leigh, with considerable vehemence, “I buy spars, pigs, and flax, but not the heads of men.” On returning through the same village in the evening, he perceived that the heads had been removed. On meeting the chief, he inquired why he had removed the heads. “Because,” he observed, “you did not like to see them, and wished that you might not see any more. But the captain of the next ship will, in all probability, purchase them.”9

Leigh’s experience of being offered mokomokai by a chief is further evidence of how active the trade in heads had become by that time, when they were already being sold at auction in London.10

NEW SOUTH WALES AS A TRANSIT POINT Because of its excellent harbor and other resources, Sydney soon became a transit point for trade in mokomokai between New Zealand and Europe and North America. “Verax,” another Sydney newspaper correspondent, reported seeing two Maori heads on display at a Sydney residence in 1812, which were priced at twenty guineas each:

In passing through George Street in this town a few days since, my attention was suddenly arrested by a very extraordinary sort of bundle under the arm of a man who was passing me on the footpath. [. . .] I called to and asked him what the handkerchief under his arm contained; judge my astonishment and horror, Sir, at beholding a human head, with long black hair, in a state of perfect preservation. [. . .] As soon as I had recovered myself, I asked the man if what he showed me was really a human head; with perfect indifference as to my feelings and consternation, the man replied it was the head of a New Zealander, which he had purchased from a person lately arrived from that country, and that he was going to dispose of it for two guineas to a gentleman who was about to embark for England. I remember, about 7 or 8 years ago, to have seen in a private house in this town two human heads of the same kind, tattooed and ornamented in a manner customary among the natives of the higher classes in New Zealand, and so far as my recollection serves me, I think they were valued at twenty guineas each head. [. . .] If the import of human heads from New Zealand be so far countenanced and encouraged that the price shall fall, in the course of seven years, from 20 guineas to 2 guineas each, the inference must be, that human heads, having become by

The first of these heads that I remember to have been brought up was by a wild fellow of the name of Tucker, in 1811, who got it by plunder; and so tenacious were the natives at that time of these heads, that a whole boat’s crew were nearly cut off for the crime of this villain, which was not known until he exposed the head for sale in Sydney. The crew had an hour before the sacrilege committed by Tucker, been upon the most friendly footing with the natives; when suddenly an alarm burst out, and had the vessel not immediately got away, a hundred war canoes would have boarded her at once. This man has since been killed at New Zealand.6

Since records from this early period of contact are sparse and incomplete, there were almost certainly many other such instances of mokomokai being acquired by non-Maori of which no records remain. Those recorded instances that exist reveal a variety of tactics on the part of outsiders. In 1819 a chief was so eager to obtain an axe that he promised his own head to Marsden:

An old chief with a very long beard and his face tattooed all over had accompanied us from where we slept last night. He wanted an axe very much. At last he said if we would give him an axe he would give us his head. Nothing is held in so much veneration by the natives as the head of their chief. I asked him who should have the axe when I had got his head. He replied I might give it to his son. At length he said, “Perhaps you will trust me a little time, and when I die you shall have my head.” I promised him he should have an axe, and he gave me two mats in order to secure one.7

Though Marsden was apparently unwilling to enter into this particular arrangement, he was later accused by a subordinate, the Reverend John Gare Butler, of purchasing two heads.8 Marsden refuted these allegations and their accuracy is uncertain.

1

fig. 1 From Anne E. Keeling, What He did For Convicts and Cannibals; Some Account of the Life and Work of the Rev. Samuel Leigh (1896).

EXHIBITING MOKOMOKAI FOR PROFIT IN EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITAIN

ANCESTRAL REMAINS AND THE EARLIEST MUSEUMS The mokomokai displayed in Britain at the beginning of the nineteenth century were the forerunners of later permanent displays in museums and other institutions. These first exhibits typically included indigenous remains mixed in with ethnographic artifacts and natural history specimens gathered from non-Western sources.1 As late as the mid-twentieth century they were instrumental in supporting now discredited racist theories such as phrenology and eugenics.2 One of the most tangible results of the age of discovery was the arrival into Europe of vast quantities of natural history specimens and artifacts from newly explored parts of the world. Initially these objects mainly attracted the interest of gentlemen scholars such as Hans Sloane and Joseph Banks, and even royalty, who maintained so-called cabinets of curiosities to impress those privileged enough to see them.3 However, soon such exotica began to be presented to wider audiences.

Ashton Lever’s passion for acquiring exotic foreign objects led to him opening the Holophusicon in London in 1775.4 Unlike the British Museum to which it was favorably compared, Lever’s museum lacked government support and, as such, was to be the precursor, over the next few decades, of several similar, though usually less ambitious, establishments. After running into financial difficulties, the contents of what was later to be known as the Leverian Museum were sold at a sixty-day-long auction in 1806.5 There is no record that any mokomokai were among the contents of the sale.6

The dispersal of the contents of the Leverian Museum added to the stream of objects arriving into Britain and coincided with the establishment of several other so-called museums. Some of these were simply private collections to which the general public was not admitted, but others were open to the public and charged admission to anyone curious to see their contents. An example of the latter was the ambitiously named “Museum Humfredianum” or “Humphrey’s Grand Museum,” which contained the extensive ethnographic collection of George Humphrey. The contents of this museum were sold in 1779, but Humphrey continued to collect and sold another large collection to the University of Gottingen in 1782.7 Most of his stock comprised natural history specimens, but there were also Pacific artifacts—most likely from Cook’s voyages.

The earliest public displays of mokomokai in Europe were in privately owned premises established for profit. Probably the best-known example was William Bullock’s

CHAPTER IV

1

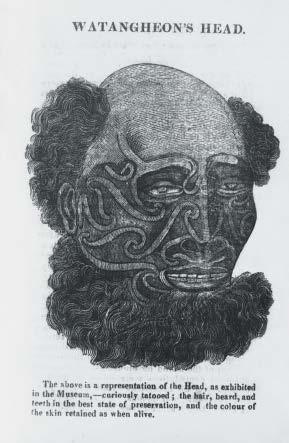

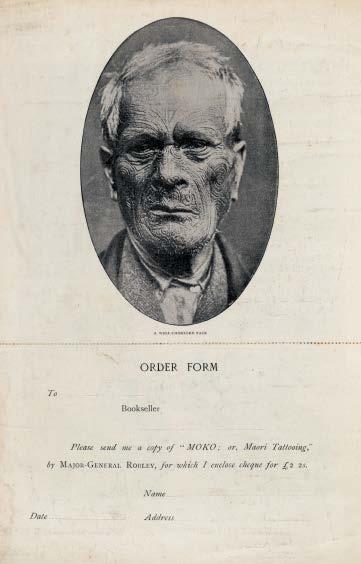

fig. 1 From Narrative of the Massacre of the Crew of the Ship Boyd, etc. [National Library of Australia, F4115-facsimile, n.d.] Museum, Engraving. 6½ by 4½ in., Published by G. S. Reddell, 1818, £2 10s.”12 George S. Reddell was for several years the owner of the Royal Museum in London, which was located in various premises between 1810 and perhaps as late as 1822. Reddell was a sword maker and engraver, as well as a friend of the poet John Keats.13 The present whereabouts of this engraving is unknown, but since Reddell was an engraver, it was presumably by his hand. It would also appear that by 1818 this mokomokai was exhibited at the Royal Museum in London. Possibly, the earliest sale of a mokomokai at a British auction occurred on November 8, 1820.14 Reddell’s sale of his museum’s stock extended over several years. On March 19, 1821, a notice of sale appeared in the Morning Chronicle, and the auctioneer was a Mr. C. Dubois, who was King’s successor at the well-known Covent Garden auction premises.15 During the same period that Reddell’s museum was in business, another, probably similar establishment existed in the port city of Liverpool. The Royal Liverpool Museum seems to have been established some time before 1812 and was situated at 1 Church Street. It was originally owned by the silversmith John Mumford, who died in 1812. After his death, his descendants ran into financial difficulties and it was taken over by John Kind. An 1815 catalogue lists the contents of the museum as including objects from Africa and the Pacific but no mokomokai are listed.16

The Liverpool Mercury of June 14, 1822, announced an exhibition at the Liverpool Museum that included the “head of Watangheon [. . .] one of the principal perpetrators of the massacre of the ill-fated ship’s crew, the Boyd,” along with a painting of the massacre.17 Another advertisement for the exhibition appears in The Kaleidoscope; or Literary and Scientific Mirror of November 5, 1822.18 It is not entirely clear whether the head on display in Liverpool in 1822 was owned by Mr. Kind or whether he had merely borrowed it, but given that Reddell was actively selling off the contents of his London premises around that time, a sale to Kind is a possibility.

An undated anonymous pamphlet titled Narrative of the Massacre of the Crew of the Ship Boyd, at New Zealand, by Cannibals, Embellished with a Representation of the Real Head of Watangheon, the Principal Murderer, and a Frontispiece, copied from the Grand Painting exhibited in the Royal Liverpool Museum (“The Narrative”) includes a crude image of a mokomokai and was presumably produced to coincide with the 1822 Liverpool exhibition.19 It is also likely that Reddell’s 1818 engraving is the exact image appearing in The Narrative, especially given that it was labeled with exactly the same language used in the 1822 advertisements for the Liverpool exhibition. The Narrative was probably produced sometime between 1818 and 1822. This also means

Egyptian Hall. Bullock was a jeweler-silversmith with a keen interest in natural history. His passion led him to acquire objects from ships arriving in Liverpool, where he held his first public exhibition in 1795.8 Bullock acquired objects from the South Pacific at the Leverian Museum sale in 1806. In 1809 he moved his enterprise to London where it was initially called the Liverpool Museum. By 1812 his London premises, now described as the London Museum, took the form of a building in the style of an Egyptian temple, and became known as the Egyptian Hall. After failing in attempts to interest the British Museum or any similar institution in their purchase, Bullock sold his collections at auction in 1819.9 The sale took twenty-six days and was the largest of its kind since the Leverian sale in 1806. Most of Bullock’s ethnographic objects went to the Berlin Museum. There is no record of mokomokai among the several Maori and Hawaiian objects offered with Cook voyage provenance but since Bullock did not publish details of all the items on offer it is possible that one or more was included.

After his successful 1819 sale, Bullock became a full-time auctioneer. Around the same time other entrepreneurs began to organize overtly commercial displays of exotic foreign objects.10 The broadsheets and handbills issued by the proprietors of these establishments were to contain some of the earliest known detailed illustrations of mokomokai. There was an incentive to produce crude banners and handbills since newspaper advertisements were subject to tax. Richard Altick writes of these enterprises as follows:

The conditions of the exhibition business being what they were—fiercely competitive, with a long tradition of hyperbolic language and almost routine misrepresentation or suppression of facts—ordinary business ethics were at a deep discount. [. . .] In handbills and placards, however, the showmen threw off whatever restraints may have governed their statements in the Times and the Athenaeum. There they drew upon every trick of the trade as well as every font of type in the printer’s cases: the declaration of the exhibit’s rarity or strict uniqueness [. . .] the grave protestation of the exhibit’s genuineness.”11

Since these individuals were primarily motivated by profit, through charging admission or selling objects on display, and the nature of many of their premises was little more than glorified junk shops, any claims made about the nature of what they possessed, or its provenance, must be treated with suspicion.

THE “HEAD OF WATANGHEON” (TE ARA)—A HOAX OF THE BOYD? The 1934 Catalogue of the Books, Maps and Pictures relating to Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific comprised the vast library of the renowned collector and ethnologist James Edge Partington (1854–1930). Among the listed items (Number 1490) is: “The Head of Watangheon, a Chieftain of New Zealand, one of the Principal Perpetrators of the Massacre of the Ill-fated Ship’s Crew, the Boyd [. . .] now exhibited at the Royal

Appendix 2

5 CONTINENTS EDITIONS

ART DIRECTION Annarita De Sanctis

EDITORIAL COORDINATION Elena Carotti in collaboration with Lucia Moretti

EDITING Charles Gute

COLOUR SEPARATION Maurizio Brivio, Milan

All rights reserved © 2021 – Robert Kirkwood Paterson For the present edition © 2021 – 5 Continents Editions S.r.l.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-88-7439-965-9

Distributed by ACC Art Books throughout the world, excluding Italy. Distributed in Italy and Switzerland by Messaggerie Libri S.p.A.

www.fivecontinentseditions.com

Printed and bound in Italy in June 2021 by Tecnostampa – Pigini Group Printing Division, Loreto – Trevi for 5 Continents Editions, Milan PHOTO CREDITS The following images were photographed by Goran Basaric´ : Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: 5 and 7 Chapter 2: 1 Chapter 3: 1, 2, 4 and 6 Chapter 5: 5 and 7 Chapter 6: 7 Chapter 7: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8 and 9 Chapter 8: 1–5 Chapter 9: 7 and 11 Appendices: 1–5

The following images were photographed by Brian Carlson: Chapter 2: 2 Chapter 6: 1

While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders for this publication, any enquiries should be directed to the Publisher.