2 minute read

Back cover: Paula Modersohn-Becker, detail of cat

from Making Modernism

51

Marianne Werefkin Twins, 1909 Tempera on paper, 27.5 x 36.5 cm Fondazione Marianne Werefkin, Museo Comunale d’Arte Moderna, Ascona. Inv. no. FMW 0-0-13

113

52

Marianne Werefkin At the Café, 1909 Tempera, pencil and grease pencil on paper on cardboard, 54 x 72.2 cm Fondazione Marianne Werefkin, Museo Comunale d’Arte Moderna, Ascona. Inv. no. FMW 0-0-14

53

Marianne Werefkin, The Dancer Alexander Sacharoff, 1909 Tempera on paper on cardboard, 73.5 x 55 cm Fondazione Marianne Werefkin, Museo Comunale d’Arte Moderna, Ascona. Inv. no. FMW 0-0-15

Spiritual in Art (1912) was an important text for Van Heemskerck, she was generally critical of attempts by modernists to set down rigid views on painting in words, feeling that this could curtail the ‘deep, glorious spontaneity of art’ as she wrote to Herwarth Walden in 1915.3 Van Heemskerck did welcome the interest of Willem Zeylmans van Emmichoven, who, in addition to his work as a doctor, followed the principles of anthroposophy and wrote on art; he dedicated essays to Van Heemskerck, one evoking the state of ‘enchantment’ he felt her works reflected.4

Van Heemskerck exhibited with Der Sturm every year from 1913 until her death, and corresponded regularly with Walden, who, alongside Nell, became one of her greatest supporters. In 1914 Der Sturm showed a double exhibition of works by Marianne Werefkin and Van Heemskerck (see pages 34–41) and in 1915 the German Expressionist poet Adolf Behne (1885–1948), a long-established critic and contributor to Walden’s associated journal, Der Sturm, included reference to her work in his book Towards a New Art. By 1916 Behne had purchased five of Van Heemskerck’s paintings. She also made a series of Expressionist woodcuts specifically for publication in the journal, representing motifs such as windmills and sailing boats, albeit in a highly stylised way, with a strong emphasis on visual rhythm.

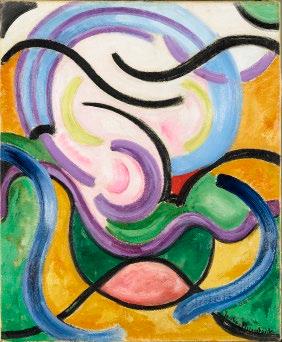

Her use of the title ‘Composition’ or ‘Picture’ (‘Bild’) for an array of paintings indicates her allegiance to abstraction. Although the arrangements of her paintings do sometimes stem from observable motifs, the dominance of shape, colour and texture – such as in the trembling, thunderous vibrations of Composition (1917–20; cat. 66) or the fluid, sinuous strokes of Composition No. 84 (Portrait of a Child) (1918; cat. 65) – means the paintings are not restrained by any sense of perspectival recession or scale, the visual sensations fully autonomous.

From around 1916 Van Heemskerck pursued mosaic, stained-glass painting and window design, finding in these mediums a way to engage with architecture, to design compositions on a larger, immersive scale, and to unite colour and light. In 1920 she produced ambitious works for the windows of a private villa in Wassenaar, a suburb of The Hague, including a continuous composition across eight stained-glass panels. Some of her glass pieces were exhibited with Der Sturm (although Walden did not encourage this direction in her work), while others were designed for public sites in Amsterdam, such as the stairwell of the naval barracks (now destroyed) and a new health centre.

Van Heemskerck died unexpectedly of angina at the age of 47. In the same year, Willem Zeylmans van Emmichoven dedicated his doctoral thesis ‘The Effects of Colours on Emotions’ to the artist.

65

Jacoba van Heemskerck Composition No. 84 (Portrait of a Child), 1918 Oil on canvas, 46.5 x 38.5 cm Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague. Inv. no. 0332252