4 minute read

A Critical History

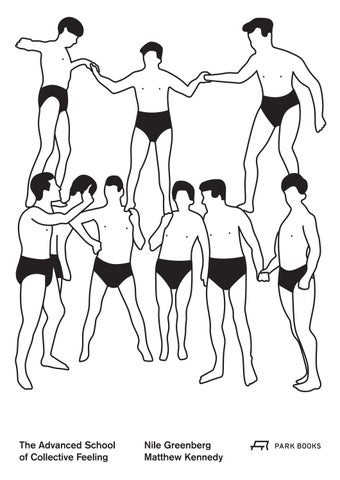

“Gret Palucca’s dances, Rudolf von Laban’s motion choirs, and Bess Mensendieck’s functional gymnastics have surpassed the aesthetic eroticism of the painted nude. The stadium has carried the day against the art museum, just as bodily reality has taken the place of beautiful illusion. Sport unifies the individual with the masses. Sport is becoming the advanced school of collective feeling.”

In 1926, just a year before he was appointed as head of the newly established architecture department at the Bauhaus, the Swiss-born architect Hannes Meyer published an essay, “The New World.” This utopian portrayal of social and technological progress was, in effect, a manifesto for the nascent radical-functionalist, anti-aesthetic design philosophy he would later dub Die neue Baulehre—“the new way to build.” One of Meyer’s more ecstatic observations addressed the emergence of a new and distinctly modern fascination with sport, a phenomenon he believed had already superseded art as the driving force of mass culture. He asserted that this triumph—of physicality over representation, of collectivity over elitism, of empiricism over formalism—was evidenced by the popularity of the German physician Mensendieck’s system of therapeutic gymnastics, the Hungarian dance instructor von Laban’s applied theories of human movement, and the progressive choreography of Bauhaus associate Palucca.

The Bauhaus had a well documented culture of sport, made iconic by images like T. Lux Feininger’s 1927 photo, “Jump Over the Bauhaus.” This fascination with physical culture carried over into contemporary projects by the architectural faculty, most notably Gropius and Marcel Breuer (more on this later), though the school itself was conspicuous in its lack of a gymnasium.

“Each age demands its own form. It is our mission to give the new world a new shape with the means of today. But our knowledge of the past is a burden that weighs upon us, and inherent in our advanced education are impediments tragically barring us from new paths. The unqualified affirmation of the present age presupposes the ruthless denial of the past.”

Meyer was chosen to succeed Walter Gropius as director of the Bauhaus in 1928. Soon after this promotion, he began work on the design of the ADGB Trade Union School in Bernau. His scheme prominently featured a gymnasium outfitted with modern fitness equipment, as well as a running track encircling a pond on the grounds. It is clear from his writings that Meyer considered the integration of physical culture into everyday life to be one of the crucial tasks of modern architecture—his belief in its collectivizing potential led him to describe it as “the advanced school of collective feeling.” But, in fact, there is little to suggest that the gymnasium of the ADGB School differed much from the gymnasia that had first begun to take shape at the beginning of the 19th century. Many of these were, in effect, indoor variations of the so-called Turnplatz, an open-air facility opened in Berlin in 1811 by the German “father of gymnastics,” Friedrich Jahn. Jahn had served in the Prus- precondition of a modern Germany, capable of withstanding the aggression of its neighbors. apparently accepted this received ideal without question, though it was over a century in the making, and rooted in an ethnically and culturally specific, and thus inherently exclusionary philosophy. Put plainly, the objects around which modern physical culture was built in the 1920’s were far from universal, having originally been developed for the perfection of a militarized, male German body. Despite the apparent contradiction, the design of these objects has been more or less untouched in the century since. However problematic we may now recognize this to be, the modern movement’s presumption of objectivity regarding the modernist body ensured that it would reverberate far beyond the spaces physical culture, from the biometric diagrams and building standards of Ernst Neufert’s Bauentwurfslehre, first published in 1936, to prevailing ideas about the modern domestic interior flourishing throughout the world.

Jahn’s nationalist philosophy, sparked by the geopolitical conditions of early-19th century Europe, has made him a controversial historical figure, alternately cited as an inspiration for the Third Reich’s ethnocentrism, or lionized as a key figure in the earliest stirrings of modern physical culture. He is widely credited for the invention and popularization of the pommelhorse, the horizontal and parallel bars, and gymnastic rings. Early photographs of the ADGB gymnasium clearly depict the inclusion of all of these objects, and it is here that we find one of the most problematic aspects of Meyer’s collectivist vision. “A ruthless denial of the past,” he insisted, is necessary to ensure a radically collective new society, but in his hurry to move forward, it appears that Meyer failed to register that he had taken as a point of a departure an unexamined ideal of the modernist body.

Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

11 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

12 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

13 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

14 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

15 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

16 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

17 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

18 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

19 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York:

Publishing Entity, 1924.

20 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

21 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

22 Lastname, Firstname.

Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

23 Lastname, Firstname.

Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

24 Lastname, Firstname.

Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

25 Lastname, Firstname.

Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

29 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

30 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

31 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

32 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

33 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

34 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

26

Lastname, Firstname.

Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

27 Lastname, Firstname.

Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

35 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

36 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

28

Lastname, Firstname.

Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

37 Lastname, Firstname. Title Here Title. New York: Publishing Entity, 1924.

38 Lastname, Firstname.