6 minute read

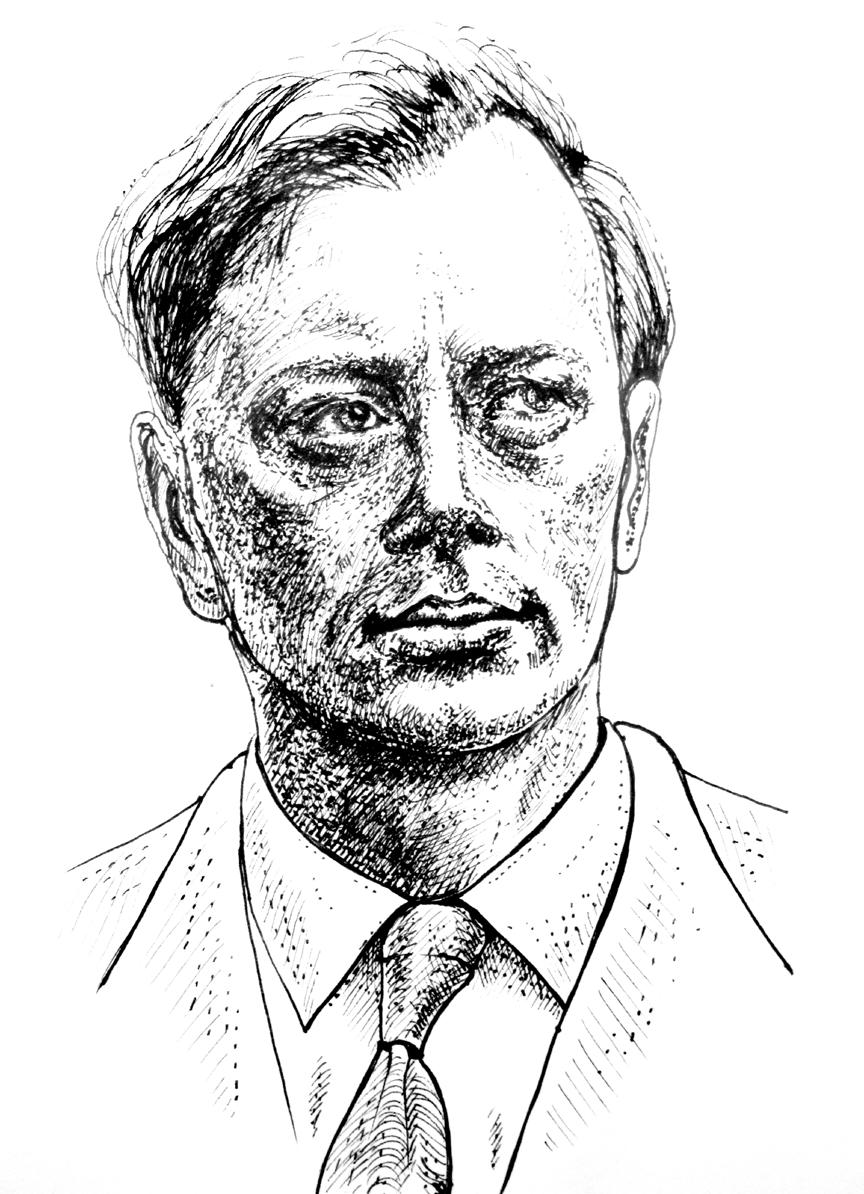

MICHAEL SLEIGH

As the SEB celebrates its 100th anniversary this year, our science writer Alex Evans had the pleasure of talking with someone that first became involved with the SEB almost 70 years ago, biologist and former council member, Michael Sleigh.

Hello Michael! The major focus of your research career has been on protists, how did you become interested in this field of study?

I have indeed worked with protists through much of my career. The reason is that they provide excellent, accessible and often easily cultured examples for research on cilia and flagella. These organelles have been my central interest from my first publication in 1956 to my latest collaborative work published in 2022, and in a majority of the 180 publications between. My attention has been focused on how these organelles achieve their functions in movement of fluids for such purposes as locomotion, feeding or cleansing of surfaces. The subjects of my research have been animals of many invertebrate groups and vertebrates, including humans. Human diseases which result from defects in ciliary function include cystic fibrosis and a family of genetic abnormalities that result in male infertility and impaired clearance of mucus from the lungs, and I have made research contributions in studies on both of these types of disease.

What have been some of your proudest accomplishments in your research career?

Looking back, I am proud of my first book The Biology of Cilia and Flagella, published in 1962 and summarising what was known then. This was timely, for in the next 10 years, electron microscopy revealed many new details and research on biochemistry and physiology of cilia flourished, so that in 1974 I was able to call on many experts, including Irene Manton, to contribute chapters to an update entitled Cilia and Flagella. I am also proud of another monograph The Biology of Protozoa (1973), which was widened and updated as Protozoa and other Protists in 1980, both of which have been used in teaching in Europe as well as across the English-speaking world. In another area, I am proud of an article that I coordinated in The Lancet (1981), publicising the name primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) for the family of genetic diseases affecting human ciliary function; there are now PCD units in a number of hospitals in the UK, meeting each year. From 1970 to 1973, I served as a Symposium Convenor and arranged and edited two symposia on subjects chosen by a Symposium Committee. The SEB Council organised a dinner for the first Honorary Members in November, 1964. At this dinner, Lancelot Hogben gave a speech about the origins and early history of the Society. The Council felt that the contents of this speech should be recorded for posterity and James Sutcliffe, the Botanical Secretary, persuaded Hogben to write it up for publication in a Society booklet. To accompany this account of the origin of the SEB, I wrote an account of the history of the SEB up to that time, and the two were published together in 1966 in the first SEB history booklet. This was reprinted in 1973 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Society with additions to bring it up to date. including Southampton, concerned with diagnosis of these diseases. This article arose from a meeting in the USA where several different names were being used in discussions about these diseases, first described under the name Kartagener syndrome. My request for agreement about a single name led to me being commissioned to canvas opinion about the name that commanded the largest support from relevant scientists and clinicians.

What are your earliest memories of the SEB, and which was the first event you remember attending?

My first memory of the SEB dates from a conference in Bristol in April 1954. A number of foreign biologists, mostly from Denmark, had been invited to a local symposium on cell physiology in Bristol in the previous week with funding from the Colston Research Society, founded in memory of the Bristol educational and social philanthropist (yes, the one whose statue was toppled into the harbour). Some of these visiting biologists stayed on in Bristol to join in an international meeting of the SEB and, along with other PhD students, I was recruited to help with local arrangements and made friendships that lasted many years. That was a memorable year, for in September 1954, I attended a SEB symposium in Leeds entitled ‘Fibrous Proteins and their Biological Significance’, which provided valuable background for understanding cilia.

Since first joining, which positions and responsibilities have you held in the SEB Council?

I was elected to the SEB Council in 1964 and was persuaded to stand for election as Zoological Secretary in the following year alongside the Botanical Secretary. In those days, the joint secretaries were the principal organisers of SEB activities, supported by a Treasurer who had some secretarial help from the Institute of Biology to deal with membership matters, and a Council of 18 members each serving 3 years. All three of the principal officers were full-time academics running SEB affairs in their spare time, arranging three ordinary conferences and one symposium

Are you still active within the SEB or any other scientific societies?

After my 10 years as an officer of the SEB, I moved on to take a more active role in protistological societies at the national, European and international level, at the expense of being active in the SEB, apart from presenting papers at SEB symposia. In a related area, I served for a term as a director of the Company of Biologists and I am still a member of the Company. I was also elected to the councils of first the Marine Biological Association and then the Freshwater Biological Association in recognition of contributions to research in those areas. After retiring from the staff of the University of Southampton, I was invited to be the Managing Editor of the European Journal of Protistology and held that post from 2000 to 2010. I was awarded the Reichenow Medal of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Protozoologie in 2001.

For you, what are some of the biggest changes that the SEB has undergone over the years?

The SEB has totally changed in the 50 years since I retired from an active role in SEB administration. To a large extent this reflects the changes that have taken place in universities during that time. In 1945, there were about 12 universities in England that were able to award their own degrees and a handful of university colleges that prepared students for degrees of London or another university. In the post-war years, these university colleges became independent and were joined by a selection of new universities such as Sussex, East Anglia and York. The Robbins expansion of higher education enormously increased the numbers of staff and postgraduates in universities and research institutes who might be interested in membership of the SEB, and these have increased further more recently. This has required a transformation from the small, amateur, part-time administration with no salaried staff during my active service in the SEB to what appears to me to be a much larger and more professional organisation today.

Do you have a favourite or particularly memorable SEB conference or symposium?

I think that my favourite SEB conference was a symposium on the effects of pressure on organisms because it brought together scientists from many disciplines to explain how increased pressure, such as that experienced at depth in aquatic habitats, affects living organisms because the pressure doubles for every 10 m of depth beneath the water surface.

Outside of your research career, what else do you enjoy doing?

I have always been a field naturalist and days on the beach and studying stream life during my first field course with an expert and enthusiastic teacher convinced me to study Biology at university. I am still involved in conservation work with a local group, providing expertise in identifying plants and animals found in freshwater samples, but not able to provide manual support any more. After retiring from the university I moved to live in a village at the fringe of the New Forest and a former colleague who also lived in the village persuaded me to join the village History Society. This proved to be unexpectedly interesting and has led me to research in a different direction.

I am now the acknowledged expert on the history of our agricultural village from its mention in the will of King Alfred in 870 through to it providing the home for Florence Nightingale up to the time she went to the Crimea. Since our retirements, my wife and I have enjoyed travelling to a large number of countries that had not featured in earlier research and conference visits.

Thank you, Michael