19 minute read

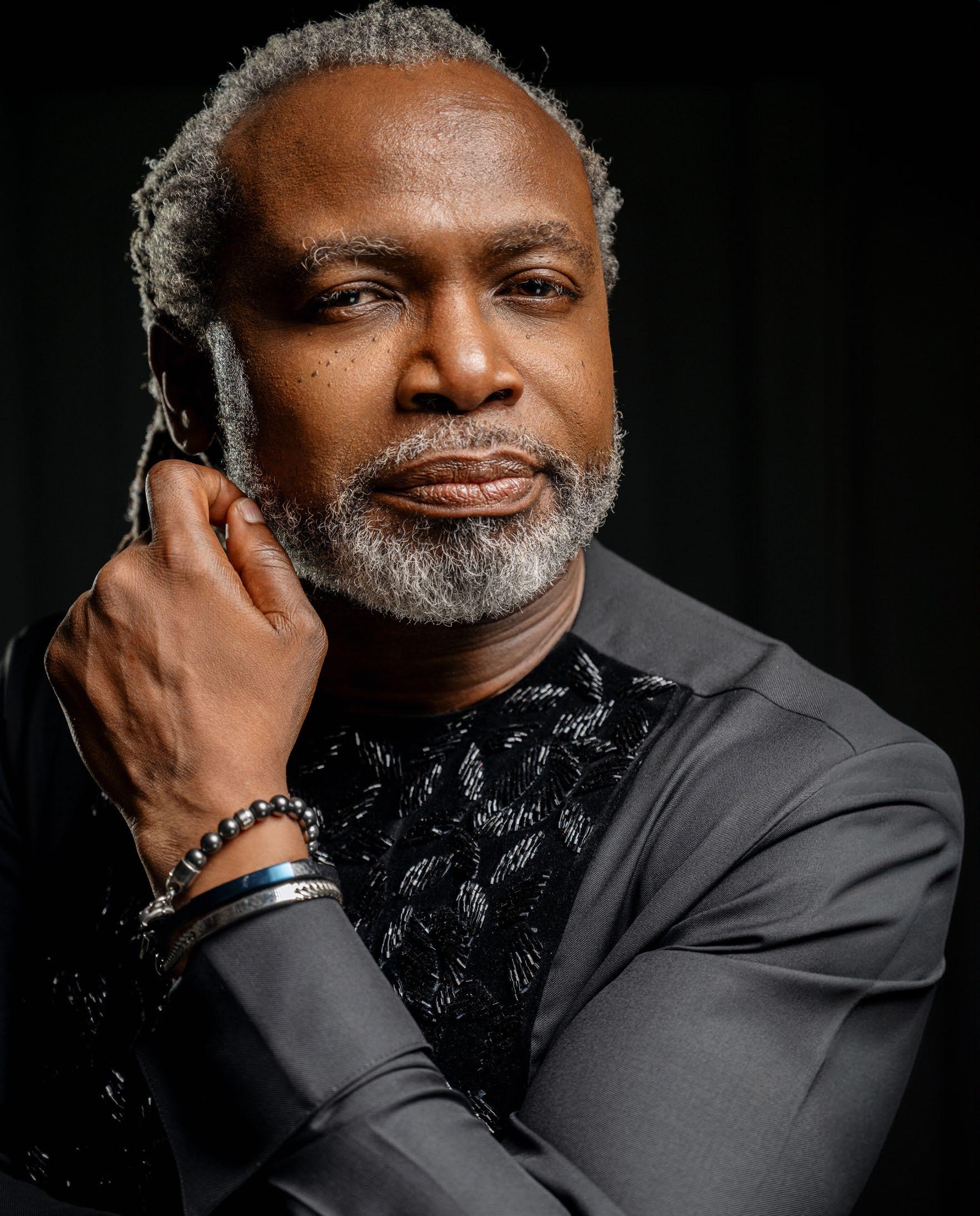

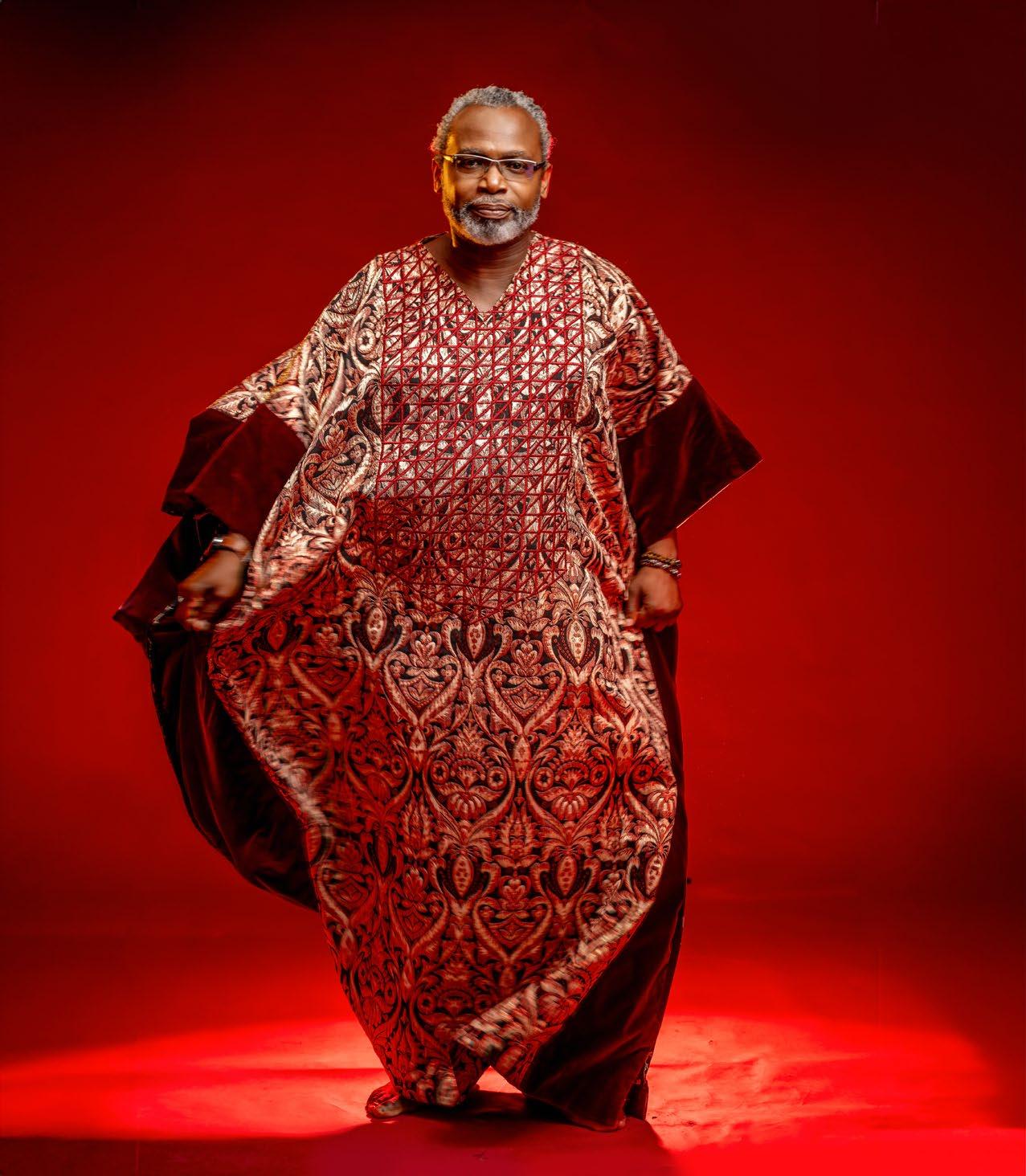

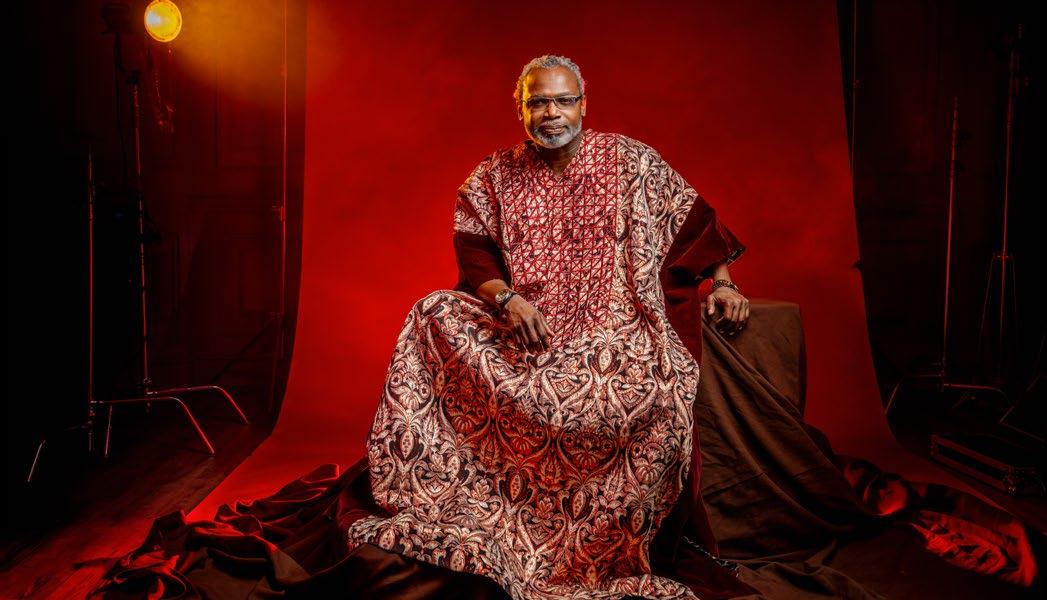

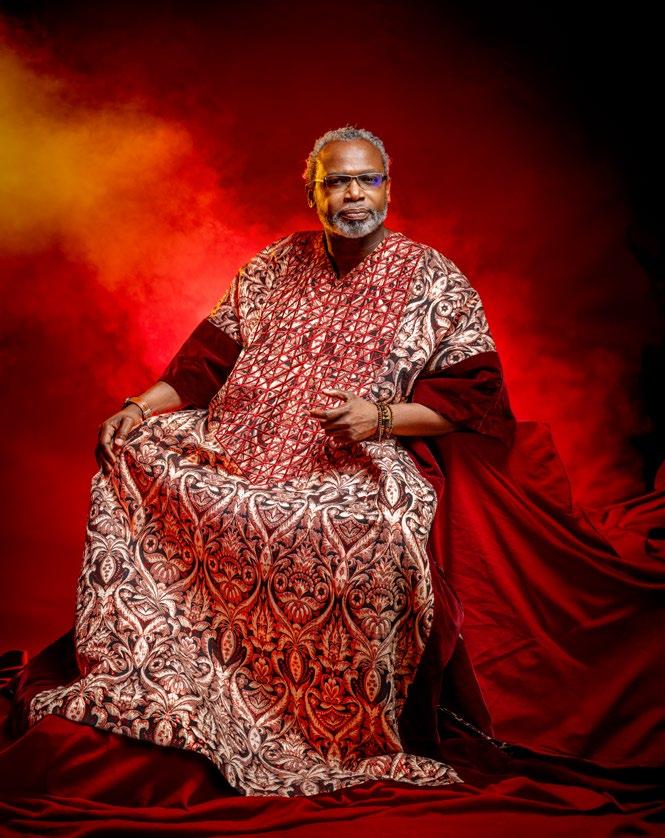

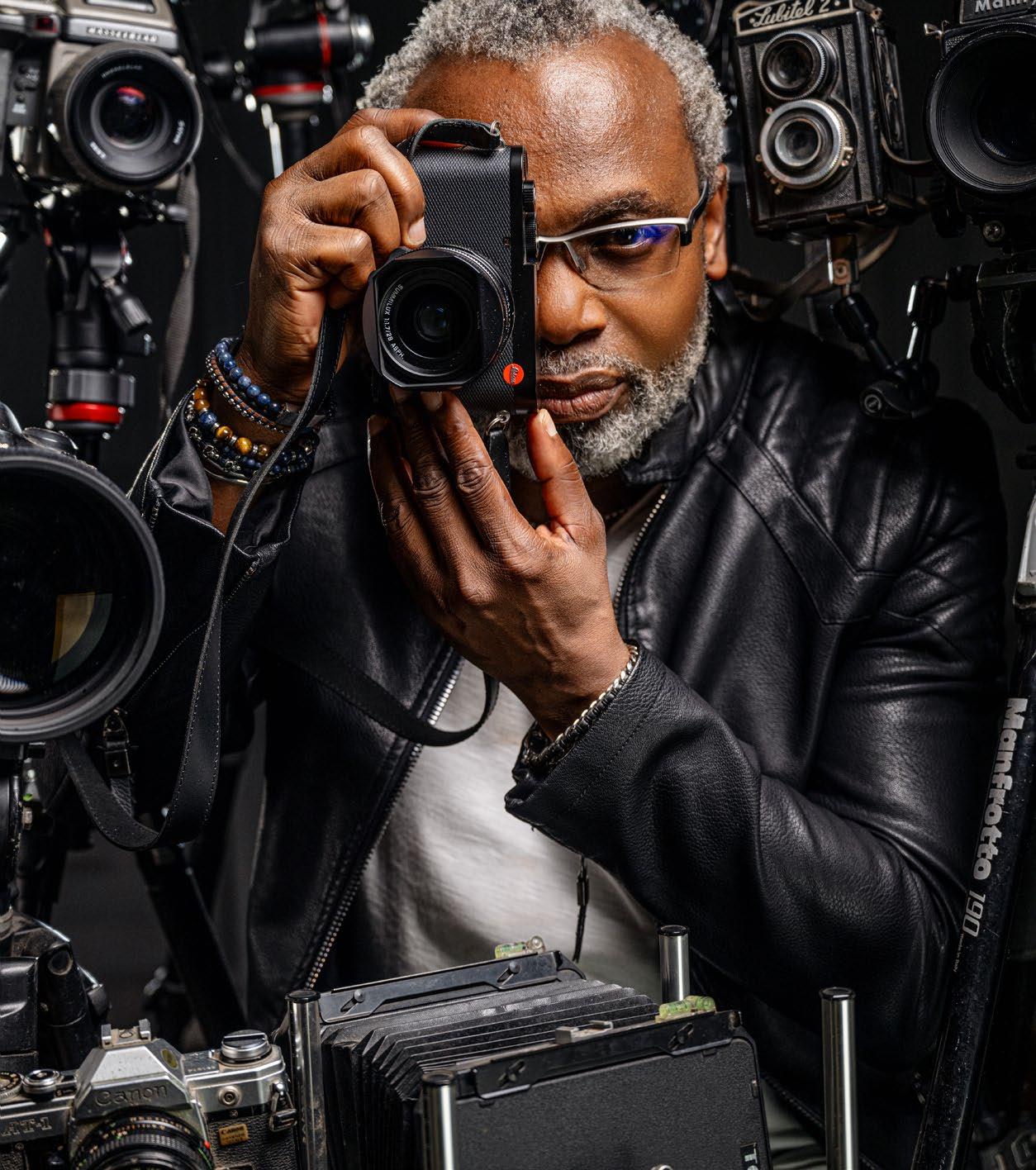

KELECHI AMADI-OBI: THE TIMELESS CREATIVE AFICIONADO

from DTNOW JULY 23

by dtnow.ng

BY OLAMIDE OLAREWAJU

Kelechi Amadi-Obi lights up the room, and I am not talking about his lights or lenses. He probably has one of the warmest auras I have ever come across.

Advertisement

He is an artist, an award winning creative photographer, and the publisher of Style Mania magazine, among other things. Many people may not know he was an artist who morphed into photography, and it’s interesting how this happened; he used to go to a specific bus stop to paint, and over time he kept getting disturbed and distracted - once people saw what he was doing out in the open, they wanted him to paint one thing or another, disrupting his process. So he chose to photograph instead and then return home to paint the pictures, but then photography took over.

At 53, KAO is a force in the creative industry; he’s especially loved in the fashion industry. There was a time when no lookbook was complete unless KAO shot it. This effortless and ever-evolving creative has photographed almost any celebrity, millionaire, you name it. He is truly timeless, if you ask me, because of his ability to reinvent himself.

You are currently known as the highest paid photographer in Nigeria (if not Africa)

As an artist and award winning household name in the industry and internationally for decades amongst various accolades after studying law, how have you been able to stay for this long? What, in your opinion, has helped make your name a force?

The first thing is that I have a passion for the visual arts. Right from childhood, I've always been obsessed with making images, starting with drawing Spiderman and the Incredible Hulk. I was obsessed with comic characters. And then, as I grew, I decided I was going to be an artist because it's what I love doing, even though the whole idea of studying law is another story altogether. But eventually, when I started experimenting with photography, I fell in love with that medium, and what has kept me going is that I have a philosophy. I believe that life is a journey, and the only arrival is death, so it is an unending journey. And for me, it's most important that the process of the journey itself is the life. So there is no point in my trajectory where I consider that I have arrived. I'm constantly navigating the next location I'm going to get to, in which case I remain a student in this very dynamic, constantly changing terrain of the creative arts. I enjoy the process of learning new things, so I would say that that is what has kept my art fresh. Because it changes, and that is also what has kept my enthusiasm fresh, because I'm still the same person who was drawing Spider Man and the Incredible Hulk as I am now. I'm just taking photos. Curiosity becomes the source through which I advance.

You’ve taken some iconic photos, your works have been featured home and abroad, and back home, you curate experiences at your booth during fashion week and create cool shots exclusively. What inspires you to create at any point?

The first time Heineken came to Nigeria during one of those fashion weeks, I think they had T-Pain coming to Nigeria then, and they said to me, “Kelechi, we would like you to do something for us for Fashion Week; we will like you to shoot the red carpet. I said no; I don’t do the red carpet. I'm a fashion photographer; I do portraits, and then I thought about it, and it occurred to me that the concept of the photo shoot as a performance, as a means of entertainment in itself, came to me. And I said, You know what, guys? I will build a set. It's Fashion Week, so people are going to be peacocking anyway, they're going to be flamboyantly dressed. So I'll just put them in my set and we'll make nice pictures, and I'll give them the pictures as I'm making them, and you'll get traction. They said that was a brilliant idea, and we did it. That was a while back, but it was such a resounding success that they kept commissioning me to date every day, and now it has become a thing. You know, people have an event, and people queue for it because it was fun. The thing is, it's a bit crazy because, with the number of people that come to Fashion Week, you can't possibly photograph everybody. So it had to be those who I chose to photograph. People line up and say, No, you don't need to line up. You know, there's no line. You know, it's who I choose, a bit quite arrogant, *laughs* But I had fun because then I would look through the crowd and I'd find a collaborator. But the thing is, the process of photographing them becomes entertainment for those who are watching, and then they see the person in front of them and the outcome on my iPad. So it's beautiful. You know, a win win situation that we got.

What inspires you to create day-to-day?

I remember an iconic shot of yours where the model was all dressed and standing on a public bus in a very busy area. You have some iconic shots. What inspires you to shoot things like these —how do you even get the idea?

It's interesting when I shoot, especially when I'm shooting fashion. When I'm trying to do some personal work, it gives me a little more leeway as opposed to when I'm shooting advertising. So I work in a different way when I'm shooting fashion or my own project. When I'm shooting my own project, I'm in search of failure. So I put obstacles in my way so that I would be compelled to react to those obstacles. And each time I react to those obstacles, it's like getting to a new place where you've never been; that is when you truly discover. So the design of my work and the visuality of it are things that I have mastered over the years. Those are just technicalities, so when you have all those technicalities in your head, you relax and flow with what life brings to you. I believe that life is a combination of design and accidents. So you plan something, then accidents happen, and then you revolve around those accidents. It is those accidents that then create the iconic images. So it is being fearless and saying, I may fail, but let's just go for it. So I say, oh, we're going to do a shoot right in the middle of town, I don't know what I'm going to see, I'm not 100% sure. So I'm in traffic, and I noticed this road at the Ikeja bus stop. You know those roads where you have a line of buses, and if you're a normal car and you enter that road, you know you've entered “one chance”. You wait for all the buses to load, the road is already that bad. I was like, ‘beautiful’!. So I stop a bus guy and say I'm going to use your car; take N5000. We just stay on top of the car. People are too captivated watching us shoot. The road was already too slow in the first place, so they just chilled, and that worked perfectly. And then I have this row of buses and all the tapestry of colours and I set out trying to shoot fashion in the midst of commerce because it's fashion. It's almost all the products you see in the background, shoes, tshirts, jeans. It's fashion. It's our own fashion; it's our own high street in a crazy kind of way. So I'm always in search of the new and not afraid to fail. The thing is this, how are you going to create something that has never been seen before if you have seen it before. So you must venture into an environment where things will happen that you've never seen,and then subconsciously, all the other inspirations that have come through art and looking at other people's work come into play, and all the elements come into play to also create a visual impact. So I’m letting accidents happen, but I'm also using my technical knowledge to create visual impact, so that's how it happens. But what is also happening is that I seek to create something different from what is within my environment. So no matter how beautiful another photographer's work is, especially around Nigeria or West Africa, I would then consciously decide to move away from what he's doing in order to maintain authenticity within that space. So that is how I've been able to keep my work fresh. It's a struggle, sometimes you succeed, sometimes you don't.

Creatives usually get their inspiration one way or another. Some when they sleep, some when they have a sip of wine, and then some when they're having conversations with people. Apart from being in photography, I know you're very creative; you come up with extraordinary things. How does it come to you? Do you sleep over it? You know whatever it is you put together creatively? Does it talk to you before you decide to?

Inspiration, like I would say, is for amateurs. We're creative, but we're also professionals. So whether we have inspiration or not, we must work. So I find that a lot of my inspiration comes from doing so when I say oh. I'm having a creative block. There's nothing like that. “Hello. Can you come to the studio? Let's do a shoot. So what's the shoot about? I don't know. Just come. once I have a model in front of my camera. One thing leads to another, you know? So inspiration, of course, can come from, oh, you have a hunch, or sometimes when I move away from photography and I start reading literature, ideas start to flow, You know, sometimes I start to paint when I'm painting. All the photography ideas now just come out, you know, so I move away from that. But most times all the inspiration comes from doing it—searching, moving, and doing something. That's really my main source of inspiration.

In this digital era where there are phones that can work in place of camera, apps that can do the smoothest edits, an era where photographers are having to compete with iPhone photographers, you still hold your own. What is your secret?

The truth is this, what is happening with the apps, with AI and social media, and just a complete explosion of technology that helps you make imagery. What is happening is that the craft of it, the toil of it, is becoming more convenient; it’s becoming easier. What will make you stand out is the humanity of who you are. You need to grasp your humanity and understand who you truly are. What is your essence? That is the part where I don't know if technology can come near it. It is your soul, and that is what makes you an artist. So those who will lose their jobs are those who are constantly trying to tell other people's stories the way those other people want them to be told. So for artists who want to survive, they must have a voice. It goes beyond making imagery. It's about who you are. It's about what you know. They say the artist must mirror his environment, But then how will you mirror your environment if you're opaque? If you have not absorbed the light, you may then reflect it back. So you must read avidly. You must be knowledgeable. You must embrace wisdom so that when you express yourself, it becomes your opinion. So for me, the whole proliferation of photography, phones, video and the AI and all that means that you must go deep and hold on to your humanity, improve your intellect, and improve yourself so that when you speak through your imagery, people can see the difference.

Photography, like any other creative sector in Nigeria, seems to have become saturated. What do you think makes you/your work unique in this almost crowded industry? I always try to advise young photographers, and what I pray for them is to have the courage to be themselves. Because if you're yourself, then you're already unique. But a lot of people don't have the courage to be themselves. They want to be someone else. I want to be like Kelechi. I want to be like TY I want to be like Big H. I want to be like Emmanuel Oyeleke, and they deny themselves. The more you deny yourself, the more you try to be like somebody else, the more you are judged by that person's parameters. So I said I didn't want to be the best photographer. By saying I want to be the best, I must judge myself by somebody who is considered to be the best, thereby putting myself under that person. I want to be the most authentic Kelechi Amadi-Obi that I can be. Nobody can compete, and that is what I keep struggling to do. And that is how I remain unique because creativity is so relative. You see, when people say the best, I say, What do you mean by best? Creativity is so relative.

What do you think the new crop of photographers can do better to improve their craft?

To improve your craft, the first thing you need to do is do the work. First, decide that this is what you truly want to do. Because for me, that is crucial. A lot of people are not sure, and if what motivates you to do it is money, then you are on a long thing. I'm sorry; you know you're on the wrong track because, at first, you're not going to be good enough for somebody to pay you. So if people are not paying you, you will lose steam, and you won't be able to practice enough to get good enough for people to pay you. So the first thing you need to do is say, This is what I like to do; this is what I want to do, whether I'm paid or not. So that passion would drive you through the process of mastery. By the time you start to master it, you're on another journey. So at the end of the day, in your first years, you know you're going to copy a lot of people, but find that time to start learning who you are. And start having the confidence to speak. But that confidence comes from mastery. So what

I say is this. To succeed, do good work and show it.

What would you say has been your biggest challenge in this industry so far? One of the biggest challenges I have with the photography industry is the lack of synergy between photographers. I think we have to find a way to synergize the industry. As for me, I'm a man with a machete in the middle of a jungle, so I make my own path, and somehow I survive. It’s good. But I look behind me, and I see that people struggle, so the biggest challenge is that the young photographers are not sort of collaborating with each other. So we need to find an environment where everybody sort of collaborates; people need to know, and then we can turn it into a better profession with a lot more synergy. Let's say, This is how much this is, what this is, how much this is, and what, so that people don't undercut each other. You know, those are some of the challenges. There are copyright issues. I mean, that's always a challenge. People can just copy your stuff; what can you do? You have to just move on and create more.

Sometimes I decide to make things very difficult to copy. It's like my photo set with the booth; to be able to do that set alone, it's going to cost you a million to set it up. So if you don't have a client that is willing to pay you from six million upwards, you're going at a loss, so the entry level for that becomes difficult. Sometimes I make it more difficult by going up the mountain to do a fashion shoot, for instance. If you want to copy, you have to be able to travel and go to that mountain to do the shoot. So sometimes that's how we solve it at the end of the day. It's a bit of a compliment; the person who is copying you psychologically has gone behind you. In that way, I like to see things from a positive angle. Whatever other problem we have—no lights, no this, no that— It's the usual thing that everybody has, not just in Nigeria but all over the world?

How did you get into photography?

Photography came upon me really because I was an artist. I was going to paint. I was coming to Lagos for law school in 1993. After law school, I went to stay with my aunt in Surulere. I took over the corridor, where we cut vegetables. I would tell them to leave the corridor because I want to paint. That's how I started, and I read these books that said, If you want to make a drawing, you have to experience it. You have to be there, and you have to see it and smell it. You have to become one with the environment you're in before you can paint. Lagos is crazy. I just started painting bus stops, so I would take my sketchpad and sit down in front of bus stops and start to sketch. Some people wouldn't mind their business; they would stop and start making comments and would sit with me and talk to me about their brother, who is an artist. It was distracting, so I thought that maybe I should get a camera and then photograph the bus stop and then go back to my studio and do a study. So I started doing that; I started taking photographs of my locations, and the better they photographed, the better my paintings. Photography and my painting started, and then I got interested in painting human beings.

I've been photographing people and got obsessed with the nude—the female nude, you know—and started taking all these nude photos. Then that was when I started studying light in a more detailed way and understanding exposure and all these things. And then I started making friends with all these photographers, Uche James, Don Barbar. I used to go to Uche’s dark room to process my films and prints, and then all those reference photos I was making for my paintings got people looking at them and asking if they were for sale. That was how I got into photography.

Then I got invited to an exhibition of Nigerian photography, the International Exhibition Abroad. I was like, Oh, these days I've been painting. Nobody has invited me to an international exhibition. So that was how I went to Mali in 2000, to exhibit at the Bay, and from there I came back. We formed a group called Depth of Field myself, along with James Hero and TY Bello. And we started exhibiting all over the world. So photography came to me like that. I was still a painter. Mind you, I wasn't making money from photography, but I was exhibiting all over the world with Depth of Field. I went to Brussels from Mali. They invited me to Milan; I had an exhibition in Milan; went to Brussels; went to France; went to Nuremberg in Germany; and then went to New York. London was crazy.

So photography came upon me like a thief in the night. The first advertising shoot I did was for British American Tobacco, which was like the biggest paying advertising company in those days. We're allowed to advertise. So that's how I started with photography, but I started enjoying it because photography is quite different from painting.

Do you remember a shoot that has remained a marvel to you? Your most unforgettable moment shooting, your most memorable shot? There are a lot of them. I remember saying, I'm tired of looking at Vogue, and I told my editor, Let's go to Paris. We're going to shoot the next editorial on the streets of Paris. And we packed our bags and went to France, and we went to shoot at the Moulin Rouge and all those places. And that was crazy. It was in the winter, and my model then was Ojy Okpe. And we had to wear these Nigerian outfits. And I remember that it was freezing. I couldn't even press the shutter; my hand was frozen, and I was pitying her, and then the police came to stop us at the Louvre. The police came and told us to leave. But that was a crazy shoot!

And then, right in that same edition, we flew back to Nigeria, and we decided to go to Obudu and do our fashion shoot right in the middle of the carnival. So while the carnival was going on, we would drag our model, stop the crew, and say, “Hey, OK, all of you will be dancing”, and then we should do crazy things like that. So those kinds of shoots were quite exciting for me. You know, I went to Obudu Cattle Ranch with Oluchi, and we shot. We used to do a lot of those kinds of crazy things. Recently, I did a shoot at Ado Awaye Lake for a perfume, and that was great. I had fun doing that. Things like that excite me. I like those kinds of challenges where you are left at the mercy of the elements.

Recently, I went around the whole country to shoot the amazing Nigeria project. I went to the most amazing landscapes. We went up. It was fun, you know, to hike up and try to capture nature. So there are just too many things going on.

What do you make of the new AI that is slowly taking over photography?

AI is one of those things that has come along Just the way we just found ourselves looking at the Internet, a cataclysmic change has come upon us. And the question is this. Whenever this happens, it's what we call rapid change, and how does it affect me? I've always been a futurist. So I look at things and see where they're going, and I try to understand how I fit in. I've gone through photography through several of those kinds of cataclysmic changes, from shooting film to digital to social media, and right now we're experiencing that. Yes, it has affected my work drastically. I'm learning very fast to understand it. The good thing about it is that everyone is new. So nobody can claim they have 10 years of experience with AI. So it depends on those who have focus, those who understand, and those who can visualize how it can be done. What is AI? It's cloud computing—computers that can do all sorts of things and can teach themselves what has happened to our photo editing, for instance. Now you can do generative imaging, if you understand what I mean. It's difficult to even explain how it's changing my work. I'm taking my old work and rejigging it with AI. AI is threatening to make people lose their jobs in terms of editing because I have an AI app now that completely does the editing like a human being. It does it in seconds, and then it can batch edit 20 images in two seconds. Something that would take people like three or four days to do. So I see it as one of those things. But whenever this thing comes along, people start to say, Oh my goodness, you know, when the calculator came along, they said all the children would be dumb; they will never do much again. But here we are. When television came, they said radio was finished, but here we are. When the telephone came, they said photographers were dead. Here we are. The question is, what do you do with it? So I'm learning, you know, my journey, chatgpt. I need to understand how it works. Just like a knife, you can use it to cut vegetables or somebody's throat. It depends on how you want to be and what side of the divide you want to be in.

With all the technology and advanced technology that you mentioned, we talked about AI and everything around the world. What do you think is the next big thing in photography? Do you think we'll still be using these cameras? Will they be outdated? Do you think we should introduce things to capture people's moments? There's something going on. Craft itself—the process of creating—is being taken over by AI I can see it. Illustrators are losing their jobs. You know, AI is generating images through word prompting, and it's developing so fast that it's unbelievable. So it will get to a point where you can't tell the difference between an image that was made by a photographer, an image that was generated by AI. But there is something that technology cannot replace; it is what has been generated through your soul, your humanity, and who you are. It takes years to mature, and it's a combination of organic electricity, DNA, and all sorts of things, and I do not see technology taking that over. So what I believe is that for one to survive, one needs to be able to adapt to all these, move closer to who you are, and dig deeper into your originality as a person. That means you need to feed your own computer and try to find what makes you different. As this happened, I started coming. I started to tell myself,Kelechi, you must lay yourself bare. You must understand who Kelechi is and sell that. But if you spend the rest of your life being a tool for fewer advertisers and clients who want to give you money, then you have no opinion. Then the real Kelechi does not come out. That one that is just helping people make images is dispensable. I can take it over. But the opinion and the ability of Kelechi to have an idea are all inside me, so the more I speak through my inner self, the more I affirm my existence. The more I deny it and try to copy, the more I will take care of my job, and then do you think that this camera that we used to capture will be replaced? Cameras are a function of technology that will always be replaced. They will constantly change. The tools we used to edit will always be replaced. That is going to change, you know, but the camera is really just capturing light, and it hasn't changed too much, only the convenience of it. So after capturing the light, AI then decides to do other things with it, which is interesting.