IOWA VISION

Philanthropy Impact page 17

News & Events page 18

Noteworthy page 22

Philanthropy Impact page 17

News & Events page 18

Noteworthy page 22

Eye Clinic Visits by Service Area

VISITS BY SERVICE AREA FY2021

TOTAL: 72,753

VISITS BY SERVICE AREA FY2022

TOTAL: 75,139

Where do our patients come from?

PATIENT VISITS BY STATE FY2022

TOTAL: 38,486

ALBERTA, CANADA 3

BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA 1

SASKATCHEWAN, CANADA 1

PUERTO RICO 1

VIRGIN ISLANDS 1

A 27-year-old man from Galesburg, Illinois came to the University of Iowa Glaucoma Clinic in 1986 seeking surgery for his glaucoma. He recognized that the few people with glaucoma in his family who were not blind had undergone surgery, and he knew he needed help if he was to keep his sight. The man had juvenile open angle glaucoma (JOAG), which is characterized by very high eye pressures at a very young age (teens to twenties) and is not typically responsive to drop treatment. Another unique characteristic of JOAG is that it is a dominantly inherited disease. This inherited type of glaucoma was what had caused so many of this man’s family members to lose their sight. The man had surgery, which has preserved the vision in one of his eyes.

A year later, when the man came in for a follow-up, Dr. Wallace Alward was the new head of the Glaucoma Service and Dr. Edwin Stone was a resident. Dr. Stone had a Ph.D. in molecular genetics, and Drs. Alward and Stone began delving into the man’s family. They started the arduous process of tracking down as many family members as they could. By 1993 they had studied 134 members of this man’s extended family. From this research they were able to link this genetic defect to an area on chromosome one. This was the first time a genetic link to glaucoma had ever been found.

But this was just the first step, Alward explained: “The linkage just meant that there’s a gene somewhere on the long arm of chromosome one. Identifying the gene itself took until 1997. I was just a small part of that—I was the guy tracking down the families. Dr. Stone, [Dr. Val] Sheffield, and [Dr. John] Fingert were the ones who did the bench work in the lab.” After four years, with the help of a cast of world-class researchers, they’d finally pinpointed the affected gene. The gene is called myocilin, which was the first, and still the most important, gene related to glaucoma. The findings were first reported in the journal Science

and is the 13th most cited paper in history with the word “glaucoma” in the title.

While the identification of the myocilin gene was a huge step and helped diagnose JOAG before any symptoms occurred, the family of the man from Galesburg was still only able to use the standard therapies that lowered the eye pressure but did not specifically address the underlying problem. Further complicating this, many of the surgical treatments for glaucoma aren’t designed for, and aren’t as effective in, patients under the age of 40—let alone in their teens or younger.

As Alward continued to see and treat members of this family, his own daughter, Dr. Erin Boese, joined the glaucoma faculty at Iowa. As a part of the glaucoma team, Boese began working with the next generation of the family Alward got to know in the 1980s through his genetics studies. Boese sought to capitalize on the decades of research her father and others had done. Not only were they able to now diagnose JOAG at a very early age, they also had found out that myocilin

“Genes” continues on page 4

“Genes” continues from page 3

mutations specifically affected just one area of the eye, the trabecular meshwork. The trabecular meshwork is the small mesh-like structure covering the natural drain of the eye that gets clogged from the myocilin mutation. Knowing this information, Boese and her team asked the question, “if the trabecular meshwork is where the problem is, what happens if we take it out all together?”

It was around this time that a new surgery called gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy (GATT) was developed. This surgery removes the entire trabecular meshwork covering Schlemm canal (the vein-like structure that drains the clear aqueous fluid from the eye), similar to removing a clogged screen from house’s gutters. Compared to traditional surgical approaches, GATT has the advantage of being much less invasive with fewer risks. Although GATT had never been used to treat JOAG from myocilin mutations, Boese quickly saw the potential and began speaking with members of the affected family about this surgical option. Boese says the history her father has had with these families was essential when discussing GATT surgery for the youngest generation. “I wasn’t starting from square one. The relationship [Alward] had built with these families really helped them trust us as we took these next important steps. It’d be one thing to sign yourself up for a surgery that hasn’t been done specifically for this disease. I think it’s another thing entirely when it’s your kid.”

To date Boese has now performed GATT surgery on 8 eyes of 4 young patients, all under the age of 18 years. To date, the surgery has been remarkably effective. Prior to surgery, all of these children had poorly controlled eye pressures despite being on every medication available. Now, all are well controlled, and 7 of the 8 eyes are off of medications entirely. To put this into perspective, their affected parents have an average of 2.8 glaucoma surgeries per eye, and despite this, more than half are legally blind.

It all started 36 years ago with the man who first walked into the glaucoma clinic with the unusual request for glaucoma surgery. Now three of his young family members are directly benefiting from the story that has unfolded since. Thanks to the advancements in genetics, research, and surgery, these young patients are looking towards a brighter future. “GATT is the first genetically-driven surgery that we’ve had for glaucoma,” Boese said. “It is amazing that we now have the ability to individualize treatment based on a single genetic mutation.”

The P. J. Leinfelder award was inaugurated in 1982 by alumni who wished to pay tribute to Dr. Leinfelder — scholar, teacher, and physician. Dr. Leinfelder served on the staff of the Department of Ophthalmology from 1936 to 1978. A faculty committee presents awards each year to the resident and fellow physicians who have made significant contributions in preparing and delivering seminars.

Resident Winner: Aaron Dotson, MD

Prototype Corneal Cufflink Plug for Emergent Management of Non-Traumatic Corneal Perforations

Fellow Winner: Edward Linton, MD

A New Diagnostic Sign of Carotid-Cavernous Fistula Using Laser Speckle Flowgraphy

Resident education has been a focus of the Department of Ophthalmology since it became its own department at Iowa, with Dr. Cecil Starling O’Brien as the first Chair of the Department in 1925. At the time, O’Brien’s threeyear residency program accepted one resident per year. Today the Residency Program has expanded to accept six residents per year. One result of O’Brien’s focus on resident education was the creation of morning rounds, which continues today—although with a slightly different look since it became less feasible to go from bed to bed as the number of residents, fellows and faculty expanded.

Another change that came about, and demonstrated the department’s continued focus on resident education, was the creation of the Residency Program Director position. Before Dr. Keith Carter became the first Residency Program Director in 1990, the Residency Program was one of the many responsibilities of the Chair of the

Department. Carter led the program into the modern era including major changes in structure and curriculum. After Carter became the Department Chair on January 1, 2006, Dr. Tom Oetting took over as the second Residency Program Director.

As Oetting stepped into the role of Residency Program Director, he inherited one of the most highly regarded programs in the country. Oetting sought to build significant relationships with students and to understand what would provide the most value for residents as they prepared to make an impact on the world of ophthalmology. Oetting developed a structured surgical curriculum that included simulation, parts of cases and formative feedback. Oetting developed a simulation facility at the VA that residents use in their early years which has led to less complications in early cases [1]. Over the years this approach caught on and is now the standard for residency surgical training in the United States. In part because of his leadership in surgical education Oetting received the inaugural ASCRS educator of the year award in 2021.

In 2015 Carter and Oetting led a national effort to update residency training. Their AAO/ACGME white paper proposed many changes including an integrated internship [2]. Quick to adopt their own recommendation the Iowa program created our current joint internship with the internal medicine program. The integrated internship adds significant ophthalmology training in the internship that complements the rest of the residency. “The reason it’s such a big deal is that one-fourth

“Residency Program” continues on page 6

“Residency Program” continues from page 5

of the training during residency is the internship, and we wanted some control over that time,” Oetting explained. He added that our relationship with the Iowa Internal Medicine service has been outstanding. Now all US programs are mandated to have integrated or joint internships – Iowa’s program got a great head start.

The residency program continues to evolve and grow to this day. This past year Oetting passed the torch of Residency Program Director to Dr. Pavlina Kemp. Kemp came to this role after being awarded the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Secretariat Award for her world-class work in clinical education in 2020 and Carver College of Medicine M3 Teacher of the Year in 2021. She also just won the Women in Ophthalmology Educator of the Year award in 2022. When asked what drew her to this role, Kemp said, “I’ve always wanted to be involved in education from the start. I really value the education and the mentorship that I received here at Iowa and being able to give back to this program is a big motivator for me. Advocating for the residents and being a part of their growth as ophthalmologists is very rewarding.”

There are things that Kemp is planning for the program that will continue to add value for residents: “We’re working towards what’s essentially a mini fellowship or advanced elective in certain fields where residents are able to tailor their residency to whichever career they’ve chosen. Whether their future practice environment requires them to do plastics procedures, to see children or have expertise in another sub-specialty, we want to focus on preparing our residents for their own unique careers. I think that’s a huge opportunity.”

References:

1. Rogers GM, Oetting TA, Lee AG, Grignon C, Greenlee E, Johnson AT, Beaver HA, Carter K. Impact of a structured surgical curriculum on ophthalmic resident cataract surgery complication rates. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009 Nov;35(11):1956-60.

2. Oetting TA, Alfonso EC, Arnold A, Cantor LB, Carter K, Cruz OA, Feldon S, Mondino B, Parke DW 2nd, Pershing S, Uhler T, Volpe NJ. Integrating the Internship into Ophthalmology Residency Programs: Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology American Academy of Ophthalmology White Paper. Ophthalmology. 2016 Sep;123(9):2037-41.

Our ophthalmology resident physicians recently participated in performing no-cost cataract surgeries for four patients seen by the Iowa City Free Medical Clinic. Faculty members supervised the procedures during “Operation HawkEyeSight,” which was made possible by a Carver College of Medicine grant intended to address health care disparities in our community.

Operation HawkEyeSight 2022 by the numbers:

11 (+1 surgery day) clinics

142 Patient visits

42 Patients with Maestro photos (84 eyes)

4 Cataract surgeries performed

598 Maestro photos taken

$0 Cost to patients

The Diversity Visiting Student Scholarship, a new initiative started in 2022 by UIHC’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Commitee, is awarded to extraordinary students from underrepresented backgrounds. Adetayo Oladele-Ajose was a recipient of this scholarship when she did a rotation at the University of Iowa and now, she’s an incoming ophthalmology resident. She shares her journey to ophthalmology and how the scholarship impacted her.

I was born in the South Bronx and my family is originally from Nigeria. We moved to rural Iowa when I was young—my father was trained as an internist but was grandfathered into an emergency medicine physician and my mother is a physical therapist turned healthcare administrator.

They recognized the need for healthcare in rural Iowa and moved there to help meet the need. It was an interesting experience growing up in Iowa. I matriculated to the University of Iowa for college where I was a track athlete for several years before moving into the advocacy space. After college, I worked for two years at Cerner as a consultant and later as a technical support analyst. During this time, I applied and soon entered medical school. I am currently a medical student at the Jacobs School of Medicine in Buffalo, New York, where I continue to work on advocacy and DEI projects as well as research in retina.

I initially became interested in ophthalmology because of an uncle with low vision from some untreated congenital ophthalmic condition. He had limited access to care while growing up in rural Nigeria. As a child, I would tell my uncle “I’m going to bring your eyesight back.” This was my first introduction to ophthalmology, but I became passionate about joining this specialty when my sister was diagnosed with Stargardt disease (Stargardt disease is an inherited form of macular degeneration causing central vision loss). Currently, my research focuses on developing a biostatistical approach to finding areas of accessibility in Rhodopsin mRNA for post-transcriptional knockdown in retinopathies associated with overproduction of metabolic debris, like what is seen in Stargardt disease.

My time at Iowa was unparalleled. I can confidently say that this was my favorite rotation in all of medical school. I spent the month rotating with neuro-ophthalmology and with Dr. Kemp on pediatric ophthalmology. Everyone was so accommodating and kind. For example, in the middle of rotation, my grandmother passed away suddenly. Dr. Kemp insisted that I take all the time I needed to process as well as go down to Texas to be with family for the funeral. The folks in neuro-ophthalmology I was rotating with also wrote me a letter of condolence that I still have to this day. I felt so cared for as a human in that moment and it sticks with me to this day. Additionally, I had the opportunity to give a grand rounds presentation during my rotation. I remember all the residents sat in the front row and asked insightful questions that made for a great discussion. On some rotations, you can be treated as less than just because you don’t have the full knowledge set yet. At Iowa, I was treated like a junior colleague and encouraged to learn and ask questions. Overall Iowa was the place where I learned the most and became confident in my exam skills. After the rotation, I had to rank Iowa as number one in my residency search!

“Adetayo Oladele-Ajose” continues from page 7

How did the scholarship support you?

It covered traveling to Iowa, application expenses, having the extra expense of paying two rents, the cost of driving cross country—all these things start to accumulate. In general, applying for rotations can start to feel like it’s less about merit and more about having the resources to actually do it. It was reassuring and gave me peace of mind to have the scholarship and know that I didn’t have to worry about these costs while at Iowa.

What did you take back from your experience that has been helpful to you?

Everyone was really helpful. Grand rounds occurred daily, which reinforced to me how important it is to be constantly learning, whether that be reviewing important points or learning something new. This is something that is unique to Iowa and is done in a way that doesn’t feel overwhelming. In addition, Dr. Kemp and many others offered to review my application. They gave me helpful feedback on my personal statement and helped me to tell my story in a way that was true to my voice.

What is the next step in your journey?

My next step is moving to Iowa! I had four months off, during which I did interviews, traveled around, and took online medical Spanish classes. Now I’m back on rotations and am making sure that I have a robust medical knowledge base to do well in residency. I also have some interesting things that are coming up—I will be presenting at ARVO and am also working on a project through a social justice fellowship. My project is based on how feelings of imposter syndrome may actually partially or wholly contribute to a hostile workplace environment telling you you’re not good enough. I’d like to develop a “hostile workplace scale” and see if validated interventions can successfully make a difference in the incidence and prevalence of imposter syndrome.

What does impact mean to you and how do you hope to make your impact?

Sometimes people think that having a seat at the table or hiring a diverse group of faces is enough to make an impact without thinking about the environment that you may be pulling people into. It’s one thing to hire diverse people, and it’s another thing to cede power to historically marginalized voices. It’s important to not only be mindful of, but also disrupt existing power dynamics to make spaces safe for all voices to speak up and provide actual and impactful decision-making power.

Another aspect of impact is having tangible resources and sponsorship. Examples of this are the Diversity Visiting Student scholarship, the Minority Ophthalmology Mentoring (MOM), and Rabb-Vennable. For example, through Rabb Vennable, I was able to attend the National Medical Association (NMA) meeting, where I made great connections to leaders in our community, and through MOM, I was given access to innumerable online resources and mentors who have provided priceless guidance and insight.

My goal is to have others from under-represented populations see that there are people who look and speak like them not only sitting at the table, but also leading and making pivotal decisions.

If you’d like to learn more about DEI at Iowa visit this link: https://gme.medicine.uiowa.edu/ophthalmologyresidency/about-residency/diversity-equity-and-inclusion

Rupak Bhuyan, MD (Vitreoretinal Surgery) Residency, New York Eye & Ear Infirmary at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

Salma Dawoud, MD (Neuro-Ophthalmology) Residency, University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences

Beau Fenner, MD (Inherited Retinal Disease)

Medical Retina Fellowship, Singapore National Eye Centre; Residency, Singapore National Eye Centre

Natasha Gautam, MBBS (Neuro-Ophthalmology)

Peds Ophthalmology Fellowship, Ann & Robert Lurie Childrens Hospital, Chicago, IL; Glaucoma Fellowship, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India; Residency, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India

Farzad Jamshidi, MD, PhD (Vitreoretinal Surgery) Residency, Dean McGee Eye Institute, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, OK

Guneet Mann, MBBS, MS (Pediatric Ophthalmology and Adult Strabismus)

Medical Retina Fellowship, Duke University, Durham, NC; Comprehensive Ophthalmology Fellowship, Grewal Eye Institute, Chandigarh, India

Araniko Pandey, MBBS (Ophthalmic Genetics)

Medical Retina and Uveitis Fellowship, Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology, Nepal; Residency, Tribhuvan University Ophthalmology, Nepal

Sean Rivera, MD (Glaucoma) Residency, University of Minnesota

Emily Witsberger, MD (Cornea and External Disease) Residency, Mayo Clinic; Internship, Mayo Clinic

Brandon Baksh, MD MD, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

Patrick Donegan, MD MD, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Matthew Hunt, MD MD, Washington University School of Medicine St. Louis

Matthew Meyer, MD MD, University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine

Samuel Tadros, MD MD, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine

Jonathan Trejo, MD MD, University of Washington School of Medicine

Andrea L. Blitzer, MD (Cornea) Cornea Faculty

New York University, New York, NY

R. Chris Bowen, MD (Retina)

Ocular Oncology and Vitreoretinal Faculty

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL

Razek Georges Coussa, MD (Retina)

Assistant Professor and Vitreoretinal Surgeon Dean McGee Eye Institute, Oklahoma City, OK

Adriana Rodriguez Leon, MD (Neuro-Ophthalmology)

Clinical Research Fellow

Neuro-Ophthalmology

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA

Edward Linton, MD (Neuro-Ophthalmology)

Clinical Research Fellow

Neuro-Ophthalmology

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA

Chirantan Mukhopadhyay, MD, MS (Medical Retina) Medical Retina Specialist

NorthShore University Health System, Chicago, IL

Tyler Quist, MD (Glaucoma)

Eye Associates of Colorado Springs

Colorado Springs, CO

Karam A. Alawa, MD Glaucoma Fellowship

Mass Eye & Ear

Boston, MA

Justine (Liang) Cheng, MD Vitreoretinal Fellowship

Oregon Health and Science University

Portland, OR

Salma A. Dawoud, MD

Neuro-Ophthalmology Fellowship

University of Iowa

Iowa City, IA

Ryan J. Diel, MD

Meadows Eye

Las Vegas, NV

David A. Ramirez, MD

Pediatric Ophthalmology Fellowship

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, PA

When Gabi Von Roedern was in high school, her optometrist said something wasn’t right with her eyes. Not only was her vision imperfect, but her eyes were dry and red all the time.

“I was told, ‘You’re overwearing your contact lenses, or it’s the very beginning of something else,’” she recalls.

But contact lens hygiene wasn’t the issue. Von Roedern had keratoconus, an eye condition where the normally round, dome-shaped cornea becomes weak and irregular. People with keratoconus have distorted, blurry, or double vision and are sensitive to light. They may also see halos when driving at night, or what Von Roedern describes as seeing fireworks around any headlight.

She got lucky, in a way. She was a graduate student at the University of Iowa studying German history when she finally decided to explore the “something else” that could be wrong with her eyes. She landed in the

office of Christine Sindt, OD, FAAO, clinical professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences in the UI Carver College of Medicine, who has been studying keratoconus for more than 20 years. Sindt has created a revolutionary, extremely customized contact lens for patients with keratoconus and other eye diseases.

“All of these people who were previously told to go home and be blind now have another option,” Sindt says.

Keratoconus is classified as a rare disease, though how many people have it is still not understood. The condition is not well known, and eye problems are often attributed to something else, as it was for Von Roedern until she was in graduate school.

“We used to think it was one in 2,000 people, but we now think it’s possibly one in 200,” Sindt says of the frequency of the disease. That doesn’t mean there’s a sudden rise in cases. Keratoconus is being discovered more often, mostly because of the popularity of laser eye surgery. With more corneas being examined—and the equipment to do it in more optometrists’ offices—more cases are being found. That and other technological advances in optometry equipment mean “we now have the ability to diagnose it and the ability to find it in its early stages,” Sindt says.

Diagnosis can now happen even before the patient notices any vision changes, says Marcus Noyes, OD, FAAO, FSLS, UI clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences. He met Sindt at a conference while a student and was fascinated by her research, which eventually led him to apply for a job at Iowa.

“In the last 10 years, the technology for determining keratoconus has gone through the roof,” he says.

1 in 200

Keratoconus can be genetic (Von Roedern has a cousin with the disease), but it often shows up in people who rub their eyes frequently. That’s because constant, aggressive rubbing weakens the collagen of the eye. Without strong collagen, the structure of the cornea degrades because collagen can “bend and stretch and snap just like the fiber of jeans,” Sindt says.

Patients have traditionally had two treatment options. They can undergo collagen cross-linking, a procedure where riboflavin B2 is put on the surface of the cornea and absorbed by collagen fiber.

When exposed to a specific wavelength of ultraviolet light, the cornea bonds and sticks those collagen fibers together.

“It doesn’t make the disease better, but it prevents the disease from getting worse,” Sindt says, which is why early detection is crucial.

“If you could catch keratoconus when it barely affects vision, that’s far better than if you catch it down the road when it severely affects how people see,” she says. Patients can also undergo a corneal transplant, which comes with its own risks.

“It’s not just cornea rejection or failure, but these patients are more likely to develop glaucoma, inflammation, and a whole host of other problems,” Sindt says. “Many times, patients will sit in my chair and think a corneal transplant is a cure, but it really takes one disease and effectively gives you another.”

Sindt knew there had to be a better answer and thought about a worn-out knee on a pair of jeans. She wanted to create a solution that’s “just like a patch.”

“It’s not going to create a new pair of jeans, but you can still wear them with the patch,” she says.

That started a 20-year journey to figure out how to create a kind of clear eye patch—a new contact lens. First, she went into the health sciences library and started reading old books on how to fit contact lenses and how the first

“Keratoconus” continues on page 12

The University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine has been granted an Unrestricted Grant by Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB) in the amount of $115,000 a year to support eye research conducted by the Department of Ophthalmology. This funding has been awarded based on a thorough review of criteria, including the department’s research activities, laboratory environment, and clinical and scientific staff, as evaluated by RPB’s renowned Scientific Advisory Panel. These funds provide flexibility in developing and expanding eye research programs, and opportunities for creative planning that go beyond the scope of restricted project grants.

“Funding from RBP is essential to advancing several important projects taking place at the University of Iowa,” Department Chair, Keith Carter, MD, said. “This type of research is ultimately what leads us to effective treatments in the clinic.”

The UI Carver College of Medicine holds one of the 30 RPB Unrestricted Grants awarded nationwide. More information about RPB grant programs and awards at rpbusa.org.

“Keratoconus” continues from page 11

lenses were developed and manufactured. She also started collecting boxes of old lenses, which she keeps in her office.

“We think of the contact lens industry as being around forever, but we’re in generation 2.5 of the technology,” she says.

That also meant many contact lens pioneers were still alive, so she interviewed them about their process. Image

Sindt collected boxes of old lenses as she was learning to develop and manufacture customizable contacts. “They used to put plaster on people’s eyes to create 3D impressions,” she notes.

That outdated approach led Sindt to the UI College of Dentistry and Dental Clinics. Faculty and staff taught her about impression materials and compounds used for teeth, which prompted her to call companies that make impression compound materials.

She also got help from the dental college’s prosthodontics department and used their high-resolution scanner. She talked to chemists about what she wanted to do and what would work and be safe to put on an eye.

While working on a study project on immune cell complexes in the cornea, she got in contact with a company that did 3D analysis. After the study was over, she continued to work with them on making 3D images of the eye.

She then partnered with a Tippie College of Business master’s class on creating a business plan for what would become EyePrint Prosthetics, which she launched in 2015. Via 3D imaging and a Food and Drug Administrationapproved ocular compound and insertion tray, EyePrint can create lenses that “are whatever the shape of the person’s eye is,” Sindt says.

“Because of the unique shape of the lenses, it allows me to do things that other lenses might not be able to do. The optics don’t have to be in the center of the lens. I can move the optics to whatever the patient is looking through. I can be really narrow on what the prescription is.”

The company is based in a suburb of Denver but works with a network of optometrists around the country who create the impressions and send that information back to EyePrint to make and ship lenses.

Noyes recently worked with a 50-year-old patient who never knew he had keratoconus. With just a demo lens, his vision went to 20/20.

“He asked why no one told him about this before,” he says. “It’s just not commonly used, and the condition is still rare, but we’re getting the word out there.”

Von Roedern was fit for her first EyePrint lenses in 2016. “They sharpened up my vision and helped with light sensitivity,” she says. “I’m very functional and happy with my lenses.”

She has not undergone cross-linking because the lenses have corrected her vision to the point where she doesn’t need it.

The experience was so positive that she also became an EyePrint employee. After finishing her master’s degree, Von Roedern moved back to Colorado, where she’s from, right at the time EyePrint was setting up their headquarters.

“I’d probably been at EyePrint for six months when [Sindt] came to visit. She said she’d never seen my eyes so white. They were just red and angry all the time before,” Von Roedern says. “It’s really changed my life.”

By Jen A. Miller

Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy (FECD) is a complex genetic disease that affects 6.1 million Americans over the age of 40 and causes endothelial cells, which form a thin layer on the inside of the cornea, to die. Without any available medical therapies to treat or slow the progression of FECD, the only option is replacing the layer of endothelial cells with a cornea transplant.

In 2016, Dr. Mark Greiner was researching ways to improve the quality of corneal transplants by maintaining the viability of the endothelial cells of donor corneas. On average, within the first six months after a cornea transplant, nearly one-third of the endothelial cells die from the trauma of removal, storage and transplantation. Dr. Greiner began investigating ways to stabilize donor corneas while awaiting transplantation. “One of the things that we really focused in on was the preservation medium. After removal from the donor, the transplant tissue gets put into corneal storage medium. It’s an FDA approved solution.” During their research, Dr. Greiner and his team at Iowa Lions Eye Bank discovered that ubiquinol (the active form of coenzyme Q10) allows endothelial cells to function better and gives them a better chance to survive the transplantation process.

The problem then became how to get ubiquinol into the solution. Ubiquinol is highly insoluble in water, in addition to being a highly unstable and reactive molecule. To get a more stable and soluble molecule, Dr. Greiner reached out Dr. Aliasger Salem, head of the Pharmaceutical Sciences and Experimental Therapeutics division in the College of Pharmacy.

Dr. Salem immediately saw the potential in applying basic research techniques to solve clinical problems through collaboration. It was through this partnership that Dr. Salem’s and Dr. Greiner’s labs began working together and publishing their results describing the application of a soluble formulation of ubiquinol for protecting corneal transplant tissue, “but also potentially for use as an eyedrop for corneal diseases.” Greiner went on to explain: “There’s currently no medical therapy to prevent the progression of the Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy,” which is why FECD is the leading cause of cornea transplants. But there’s great potential for treating FECD with topically applied drugs, such as antioxidants like ubiquinol and rho kinase inhibitors like ripasudil, without the need for a cornea transplant.

All this work led to Dr. Greiner and Dr. Salem applying for and receiving a grant from the National Eye Institute to research and develop ways to make rho kinase inhibitors more effective and available in medical treatments that prevent the progression of FECD. The investigative team is studying rho kinase inhibitors first because of their usefulness in endothelial wound healing and FECD, and has already submitted additional grants to study novel pharmacotherapeutics. The hope is that this collaboration will lead to the first drug therapy to treat FECD directly without a corneal transplant. “We’re trying to put me out of business as a surgeon,” Dr. Greiner joked.

1. Youssef W. Naguib, Sanjib Saha, Jessica M. Skeie, Timothy Acri, Kareem Ebeid, Somaya Abdel-rahman, Sandeep Kesh, Gregory A. Schmidt, Darryl Y. Nishimura, Jeffrey A. Banas, Min Zhu, Mark A. Greiner, Aliasger K. Salem, Solubilized ubiquinol for preserving corneal function. Biomaterials, Volume 275, 2021, 120842, ISSN 0142-9612

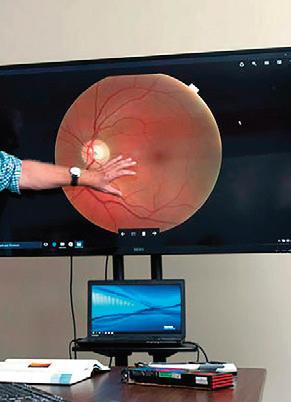

When Michael Abramoff, MD, PhD , was an ophthalmology resident, he found himself spending a lot of his time with patients doing annual diabetic retinopathy exams, only to confirm they didn’t have the disease and telling them to come back in a year. Conversely, he’d also see patients who were already experiencing symptoms of diabetic retinopathy, but to effectively treat this disease and prevent blindness, it needs to be diagnosed before the patient begins experiencing symptoms. There needed to be a way to test for diabetic retinopathy that increased productivity for providers and increased access for patients.

“In my view, the central problems in healthcare—ever increasing cost, and persistent health inequity—is because of a productivity gap,” Abramoff said. In other fields outside of healthcare, Abramoff explained, productivity has been relentlessly increasing due to “innovations such as mechanization and automation.” Even with increases in technology, like digital health records, healthcare is still heavily dependent on physicians doing most of the same manual, diagnostic tasks that they have been doing for the better part of a century.

With a background in ophthalmology and computer science, Abramoff wasn’t satisfied with the status quo. “I theorized that we could automate healthcare tasks using technology, especially in the case of chronic diseases, such as image-based diagnosis, that would improve productivity,” Abramoff said. But he also saw the benefits of this type of automation for underserved populations. “Bringing care to where the patient already visits, such as primary care and retail or laboratory clinics rather than the patient coming to the care, such as a specialist’s office,” Abramoff explained, “would increase access for patients that may never have been seen otherwise.”

The idea of using machine learning to diagnose diseases wasn’t something that just occurred to Abramoff—he had been thinking of ways to create and use this technology for decades. In the 1980s he was designing machine learning algorithms using neural networks. Through his residency he began to see specific uses for, what is now called, “autonomous diagnostic artificial intelligence.” In his PhD work, Abramoff began laying the groundwork for diagnostic AI in healthcare and eventually he began a decade’s long process of working with the FDA and other regulators to “measure how ethical principles are being met by an AI, ensure safety, efficacy and equity, and mitigate racial and ethnic bias by designing AI the right way—clarifying what the best clinical trials are, and what AI should be compared to in order to prove its safety and efficacy.” The goal was the make sure this autonomous machine learning AI, which after all makes medical decisions by itself, has high safety and minimal racial and other undesired bias.

This work led to Abramoff inventing a general machine learning approach that uses so-called “disease biomarkers” to build biomarker specific detectors that in combination now have higher accuracy, avoid the introduction of racial bias, and can determine when any of the detectors are incorrect. This “ethical framework for the creation of AI in healthcare” was the foundation on which Abramoff would begin to build AI diagnostic devices that could autonomously diagnose diabetic retinopathy.

To meet his goals, Abramoff formed a company called Digital Diagnostics. Today the automated diabetic retinopathy diagnostic solution he had envisioned years ago is a fully developed device called IDx-DR. This new technology was authorized in 2018 by the FDA for use in clinical care. As a testament to the efficacy of the IDx-DR, it’s become part of the American Diabetes Association’s “Standard of Diabetes Care” to detect diabetic retinopathy

and help prevent blindness. Just this year, Abramoff was awarded a U.S. patent for this new technology, which covers the “diagnosis of a disease condition using an automated diagnostic model.” This applies to any diagnostic device that uses AI to learn from example images, which applies well beyond eye care. Currently Abramoff’s diagnostic devices are being used in over 20 health care systems around the country. It feels safe to say that Abramoff has proven that intelligent diagnostic platforms can be deployed safely and responsibly to improve patient outcomes, while increasing healthcare productivity and patient access.

“Bringing care to where the patient already visits, such as primary care and retail or laboratory clinics rather than the patient coming to the care, such as a specialist’s office would increase access for patients that may never have been seen otherwise.”

MICHAEL ABRAMOFF, MD, PHD

Most highly cited with University of Iowa first author:

M. D. Abràmoff, B. Cunningham, B. Patel, M. B. Eydelman, T. Leng, T. Sakamoto, B. Blodi, S. M. Grenon, R. M. Wolf, A. K. Manrai, J. M. Ko, M. F. Chiang, D. Char, M. Blumenkranz, E. Chew, M. Chiang, M. Eydelman, D. Myung, J. S. Schuman, C. Shields, K. A. Goldman, R. Wolf, J. L. Gassee, D. Roman, S. Satel, D. Fong, D. Rhew, H. Wei and M. Willingham. Foundational Considerations for Artificial Intelligence Using Ophthalmic Images. Ophthalmology 2022;129(2): e14-e32. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.08.023

S. R. Russell, A. V. Drack, A. V. Cideciyan, S. G. Jacobson, B. P. Leroy, C. Van Cauwenbergh, A. C. Ho, A. V. Dumitrescu, I. C. Han, M. Martin, W. L. Pfeifer, E. H. Sohn, J. Walshire, A. V. Garafalo, A. K. Krishnan, C. A. Powers, A. Sumaroka, A. J. Roman, E. Vanhonsebrouck, E. Jones, F. Nerinckx, J. De Zaeytijd, R. W. J. Collin, C. Hoyng, P. Adamson, M. E. Cheetham, M. R. Schwartz, W. den Hollander, F. Asmus, G. Platenburg, D. Rodman and A. Girach. Intravitreal antisense oligonucleotide sepofarsen in Leber congenital amaurosis type 10: a phase 1b/2 trial. Nat Med 2022;28(5): 1014-1021. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01755-w

A. P. Voigt, N. K. Mullin, K. Mulfaul, L. P. Lozano, L. A. Wiley,

M. J. Flamme-Wiese, E. A. Boese, I. C. Han, T. E. Scheetz, E. M. Stone, B. A. Tucker and R. F. Mullins. Choroidal Endothelial and Macrophage Gene Expression in Atrophic and Neovascular Macular Degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 2022;31(14): 2406-2423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddac043

R. G. Coussa, E. M. Binkley, M. E. Wilkinson, J. L. Andorf, B. A. Tucker, R. F. Mullins, E. H. Sohn, L. A. Yannuzzi, E. M. Stone and I. C. Han. Predominance of hyperopia in autosomal dominant Best vitelliform macular dystrophy. Br J Ophthalmol 2022;106(4): 522527. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317763

E. M. Binkley, M. R. Tamplin, A. H. Vitale, H. C. Boldt, R. H. Kardon and I. M. Grumbach. Longitudinal optical coherence tomography angiography (OCT-A) in a patient with radiation retinopathy following plaque brachytherapy for uveal melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2022;26(101508). doi: 10.1016/j. ajoc.2022.101508

Most highly cited with any University of Iowa author:

M. D. Abràmoff, B. Cunningham, B. Patel, M. B. Eydelman, T. Leng, T. Sakamoto, B. Blodi, S. M. Grenon, R. M. Wolf, A. K. Manrai, J. M. Ko, M. F. Chiang, D. Char, M. Blumenkranz, E. Chew, M. Chiang, M. Eydelman, D. Myung, J. S. Schuman, C. Shields, K. A. Goldman, R. Wolf, J. L. Gassee, D. Roman, S. Satel, D. Fong, D. Rhew, H. Wei and M. Willingham. Foundational Considerations for Artificial Intelligence Using Ophthalmic Images. Ophthalmology 2022;129(2): e14-e32. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.08.023

C. M. McDowell, K. Kizhatil, M. H. Elliott, D. R. Overby, J. van Batenburg-Sherwood, J. C. Millar, M. H. Kuehn, G. Zode, T. S. Acott, M. G. Anderson, S. K. Bhattacharya, J. A. Bertrand, T. Borras, D. E. Bovenkamp, L. Cheng, J. Danias, M. L. De Ieso, Y. Du, J. A. Faralli, R. Fuchshofer, P. S. Ganapathy, H. Gong, S. Herberg, H. Hernandez, P. Humphries, S. W. M. John, P. L. Kaufman, K. E. Keller, M. J. Kelley, R. A. Kelly, D. Krizaj, A. Kumar, B. C. Leonard, R. L. Lieberman, P. Liton, Y. Liu, K. C. Liu, N. N. Lopez, W. Mao, T. Mavlyutov, F. McDonnell, G. J. McLellan, P. Mzyk, A. Nartey, L. R. Pasquale, G. C. Patel, P. P. Pattabiraman, D. M. Peters, V. Raghunathan, P. V. Rao, N. Rayana, U. Raychaudhuri, E. Reina-Torres, R. Ren, D. Rhee, U. R. Chowdhury, J. R. Samples, E. G. Samples, N. Sharif, J. S. Schuman, V. C. Sheffield, C. H. Stevenson, A. Soundararajan, P. Subramanian, C. K. Sugali, Y. Sun, C. B. Toris, K. Y. Torrejon, A. Vahabikashi, J. A. Vranka, T. Wang, C. E. Willoughby, C. Xin, H. Yun, H. F. Zhang, M. P. Fautsch, E. R. Tamm, A. F. Clark, C. R. Ethier and W. D. Stamer. Consensus Recommendation for Mouse Models of Ocular Hypertension to Study Aqueous Humor Outflow and Its Mechanisms. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2022;63(2): 12. doi: 10.1167/iovs.63.2.12

K. M. Miller, T. A. Oetting, J. P. Tweeten, K. Carter, B. S. Lee, S. Lin, A. A. Nanji, N. H. Shorstein and D. C. Musch. Cataract in the Adult Eye Preferred Practice Pattern. Ophthalmology 2022;129(1): p1p126. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.10.006

H. K. Gill, R. L. Niederer, E. M. Shriver, L. K. Gordon, A. L. Coleman and H. V. Danesh-Meyer. An Eye on Gender Equality: A Review of the Evolving Role and Representation of Women in Ophthalmology. Am J Ophthalmol 2022;236(232-240). doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.07.006

B. Chandra, M. L. Tung, Y. Hsu, T. Scheetz and V. C. Sheffield Retinal ciliopathies through the lens of Bardet-Biedl Syndrome: Past, present and future. Prog Retin Eye Res 2022;89(101035). doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2021.101035

Chick Weiner, the author of 12 books on independent living and managing disabilities, does not remember a time that she was not involved in disability rights work. As young child in the Great Depression, she has clear memories of her grandmother pulling out raffle tickets from her purse to raise funds for the Beth Abraham Home, an institution that supported people who had suffered permanent disabilities congenitally or from injuries, polio or other diseases.

She was already involved in documenting and working with people with disabilities when early one Saturday morning she received a phone call that instantly made the struggle for the rights of the disabled a personal and intimate matter. The person on the other end told her that her only sibling, Simi, had been in a very serious car crash and had been airlifted to a nearby hospital. She survived, but was left paraplegic. One year later, Simi was released from the hospital in the care of her mother and Chick. In time, with this family-led support and her own inner resilience, Simi would regain purpose and direction, earn a doctorate, and become a prominent disability rights activist.

After witnessing the challenges her sister faced and in reentering life, Chick redoubled her efforts and became a fulltime activist working for disability rights. She published, No Apologies/A Guide to Living With a Disability. In addition, she established the polio information center with polio survivor and fellow activist Harriet Bell.

By the early 1970s, she was a lead advocate for state and federal legislation including the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which would forbid organizations and employers from excluding or denying individuals with disabilities an equal opportunity to receive benefits and services. When President George H.W. Bush signed the bill into law, she was there. Later this law would become a signature piece of American legislation—the Americans with Disabilities Act.

In her late fifties, Chick started experiencing vision issues. After she and her late husband Richard moved to Miami Beach, she sought care from a Miami area ophthalmologist who diagnosed her with macular degeneration, one of the leading causes of blindness in the

world. She understood that as the condition progressed, it would eventually lead to further vision loss. She now found herself joining the ranks of the disabled.

As someone who is driven to action, she was determined to do whatever was in her power to work towards finding a cure for macular degeneration. As Chick entered her nineties, she found a new mission- to identify and support the most promising research and treatments to restore vision. She aimed to partner with the best in the world, dedicated to solving this problem. It did not take her long to find the Institute of Vision Research (IVR) at the University of Iowa. Thoroughly impressed by the caliber of research, the unique culture, and mission driven team, the Institute was unlike anything else she had ever seen before. Chick was so confident she had found the right place that she chose to generously provide significant philanthropic support, without ever setting foot on campus throughout this process. Luckily, in this day and age it was easy enough for Chick to “meet” and talk with Dr. Ed Stone, Dr. Rob Mullins, and Dr. Budd Tucker from her home in Miami Beach. When asked what made her take up this mission as her own, Chick explained, “I wanted to find a place that was taking on the ‘big problems’ and could do the most good for the world. I’m confident I have found that in the Institute for Vision Research.”

TOTAL GIVING FOR FY2022

$15,223,739

FOUNDATIONS $1,834,209

CORPORATIONS $2,476,748

NON-ALUMNUS $7,509,889

ALUMNI $3,267,318

ORGANIZATIONS $135,575

It was with great sadness that we learned of Dr. Sohan Singh Hayreh’s passing this fall. He and his wife, Shelagh, decided to venture out for the first time in three years. They went to Maine, where the youngest of their two sons and their grandchildren reside. Unfortunately, he contracted COVID, and despite vaccination and booster, the viral infection led to respiratory failure. Dr. Hayreh was on a ventilator and life support for the last week, and despite heroic medical efforts, he went into multi-organ failure and succumbed to the effects of the virus.

To learn more about how philanthropic support helps advance the work of the University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences and UI Institute for Vision Research, please contact:

Katie Sturgell

Senior Director of Development Institute for Vision Research

Katie.sturgell@foriowa.org

319-467-3756

Frank Descourouez

Associate Director of Development

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences

Frank.descourouez@foriowa.org

319-467-3672

Jedd Spidell

Assistant Director of Development

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences

jedd.spidell@foriowa.org

319-467-3342

The University of Iowa Center for Advancement

P.O. Box 4550, Iowa City, IA 52244-4550

319-335-3305 or 800-648-6973

The UI acknowledges the University of Iowa Center for Advancement as the preferred channel for private contributions that benefit all areas of the university. For more information or to donate in support of the eye program, visit the secure website at Givetoiowa.org/eye

As an authority on ocular and optic nerve circulation, vascular disorders of the eye, and giant cell arteritis, Dr. Hayreh made extensive contributions to basic, experimental, and clinical ophthalmology. The research he conducted during this time and as a lecturer in Clinical Ophthalmology at the Institute of Ophthalmology and Moorfields Eye Hospital in London would make him a pioneer in the field of fluorescein angiography.

In 1972 Dr. F.C. Blodi invited him to join the faculty at the University of lowa as a professor and the Director of the Ocular Vascular Clinic and Ocular Vascular Research. After 14 years at the University of lowa, Dr. Hayreh was awarded the degree of Doctor of Science (Medicine) by the University of London in 1987. This degree was awarded for his published research work which was judged as “original” and “of high standard such as would give a candidate an authoritative standing in Ophthalmology and in his particular field of research (Ocular Circulation in Health and Disease; Optic Nerve Disorders)” and containing “seminal publications which have led to extensions or developments by others.” In 1999, he assumed emeritus status at lowa and devoted himself full-time to his research.

The impact Dr. Hayreh made on the ophthalmic community as well as the many lives he touched is truly immeasurable. Those of us who were lucky enough to know him personally, felt his warmth, caring demeanor, and humor.

It is with great sadness that we learned of the recent passing of H. Stanley Thompson, MD. Dr. Thompson became a part of department in 1967 when, after his residency at Iowa, outgoing department head, Dr. Alson E. Braley, and incoming head, Dr. Frederick C. Blodi, hired him to direct the neuro-ophthalmology unit, which now bears his name. His interest in the workings of the pupil, under the mentorship of Irene Loewenfeld PhD, began a new era of pupillary research in Iowa City and made Iowa known around the world as a place where unusual pupillary problems can be solved. “Our department benefitted immensely from Dr. Thompson’s contributions to the field of neuro-ophthalmology—in particular making the pupil relevant,” said Keith Carter, MD, the current chair of the department. Explaining Dr. Thompson’s impact on the world of neuro-ophthalmology, Michael Wall, MD said, “he will forever be a pillar of neuro-ophthalmology for his major contributions on clinical pupillary disorders—especially his work on the relative afferent pupillary defect.”

Throughout his three decades at Iowa, he taught and mentored countless residents, fellows, and faculty— including current faculty members, Dr. Wall and Randy Kardon, MD, PhD. “He was one of the main reasons that I decided on neuro-ophthalmology—and he trained so many of us as fellows, residents, and medical students over the years with great kindness, humor and passion,” Dr. Kardon said. Despite being a pioneer and major contributor to the field of neuro-ophthalmology, Dr. Thompson never took himself too seriously. “He was an outstanding teacher and punctuated his lessons with subtle self-effacing humor,” Dr. Wall explained. “One of my favorite sayings was, after discussing a case for about 20 minutes and going in circles, he would say: ‘There is something to be learned from this, I am just not sure what.’” When presented with impromptu teaching moments, Dr. Thompson was also known to sketch out his ideas on paper napkins in lieu of a chalkboard.

But Dr. Thompson’s legacy goes beyond his professional impact: “He was a terrific mentor and teacher but most importantly he was a true gentleman,” Dr. Carter said. Dr. Kardon recalled the personal connection that Dr. Thompson formed with those in the department: “There were so many great memories over the years—especially the Thompson ‘corn parties’ at their farm each fall with potluck dinners, volleyball, softball, bicycle obstacle courses, and bringing in the corn from the field for dinner.” Wallace Alward, MD added, “His corn parties were an integral part of our culture, and his dry wit rescued many an endless faculty meeting.” Dr. Wall also remembers how special Dr. Thompson was and the lasting impact he will have on the department on top of his academic contributions: “most of all he was a gentle, caring human being and a role model for all of us.”

We will greatly miss Dr. Thompson but his legacy at Iowa will continue. One way you can help carry on this legacy is to visit the link below, which will take you to a neuro-ophthalmology fund in Dr. Thompson’s honor. This fund supports the neuro-ophthalmology unit and neuroophthalmology research at Iowa.

givetoiowa.org/stanthompson

“He will forever be a pillar of neuro-ophthalmology for his major contributions on clinical pupillary disorders—especially his work on the relative afferent pupillary defect.”

MICHAEL WALL, MD

Michael Abramoff, MD, PhD

• Gold Fellow, Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO)

• AI Champion Award 2022, Artificial Intelligence in Medicine (AIMed)

Elaine Binkley, MD

• 2022 Patient’s choice provider (top 10% Press Gainey score nationally)

Keith Carter, MD, FACS

• Special Recognition Award from the Board of Trustees of the AAO for the Minority Ophthalmology Mentoring (MOM) Program

• EnergEYES Award from the Young Ophthalmology Committee

Randy Kardon, MD, PhD

• 2021 Heidelberg Engineering

2021 XTREME research award for innovative research in diagnosis and assessment of optic nerve edema using multimodel analysis

• 2022 Impact Scholar Award (h-index=64) Carver College of Medicine Faculty Scholar Recognition

Pavlina Kemp, MD

• Women in Ophthalmology (WIO)

Educators Award – AAO 2022

• Teacher of the Year, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine (2021)

• AUPO/AAO Award for Excellence in Medical Student Education Nominee (2022)

• Patients’ Choice Award. Top 10% in the Nation on Press-Ganey Survey (2022)

Sophia Chung, MD

• 2021 NANOS Merit Award

John Fingert, MD, PhD

• Named Gold Fellow of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (FARVO) at the annual ARVO meeting this year.

• Appointed to the Scientific Advisory Board for Research to Prevent Blindness

• Invited Lecturer in the Knapp Symposium at the American Ophthalmological Society

• Top 5 paper presentation at the American Glaucoma Society annual meeting

Jaclyn Haugsdal, MD

• GME Excellence in Clinical Coaching Award – GME Leadership Symposium

Robert Mullins, PhD

• Rob Mullins was recognized on the UIHC’s Wall of Scholarship: The Wall of Scholarship acknowledges current UI Carver College of Medicine faculty who are first or senior authors of published research articles that have made a significant impact on a particular field of science or medicine.

• Named Gold Fellow of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (FARVO) at the annual ARVO meeting this year.

Thomas Oetting, MD

• GME Leadership Impact Award — GME Leadership Symposium

• American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 2020 Educator Award, 7/2021

• Newsweek Top Ophthalmologists in the United States, 7/2021

• CRST 12 Top Mentors, 12/2021

• Castle Connolly’s Top Doctors, 2022

• American Academy of Ophthalmology, Secretariat Award, 2022

• Newsweek Americas Best Eye Doctors, 9/2022

Chau Pham, MD

• Inducted into the American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in May 2022 during the ASOPRS Spring Meeting

Andrew Pouw, MD

• Mentoring for Advancement of Physician-Scientists (MAPS) Award from the American Glaucoma Society (AGS)

• Recognized as THRIVE @ Carver Fellow

Nathaniel Sears, MD

• Named Perimetry (Visual Field) Medical Director (December 2022)

Christine Sindt, OD (and Jody Troyer, CRA)

• Creative Design and Process Award - GPLI at the 2022 Global Specialty Lens Symposium

• Grand Prize Anterior Segment image - American Academy of Optometry

Milan Sonka, PhD

• Named to National Academy of Inventors

Edwin Stone, MD, PhD

• Retina Research Foundation Award of Merit in Retina Research– 2022 Retina Society Meeting

• Gold Impact Scholar: Carver College of Medicine Impact Scholars are selected based on the Hirsch index, also known as the H-index, which represents the number of research papers a faculty member has published, and the papers’ impact as determined by how many times they have been cited by other scientists and scholars in subsequent research articles.

Budd Tucker, PhD

• Cogan Award: The annual award recognizes a researcher age 45 or younger who has made important research contributions in ophthalmology and visual science, and who shows substantial promise for future contributions.

• Elected Vice President of the Americas of the International Society for Eye Research (ISER)

After a sliver of steel went through Larry Molyneux’s right eye, the 68-year-old What Cheer, Iowa, man wasn’t sure he’d be able to keep the eye, let alone ever see again. But thanks to an artificial iris implant done by surgeons at University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics using new technology—as well as a bit of fate that prevented the steel from damaging the optic nerve—Molyneux can not only see, but his injured eye looks like it was never injured at all.

Although artificial iris implants have been around for decades, until recently only a handful of places across the country were able to perform the procedure. It wasn’t until 2018 that the first iris prosthesis was approved for use in the United States.

Molyneux is the first patient in Iowa to receive this new, human-like silicone prosthetic iris.

“This is a significant advance in technology,” says Christopher Sales, MD, MPH, an ophthalmologist and surgeon at UI Hospitals & Clinics who performed Molyneux’s surgery. “Early implants didn’t look human— they helped with vision but significantly affected the appearance of the patient’s eye.”

The new human-like silicone implant is custom made using images of the patient’s healthy iris. Once manufactured it is a carbon copy of the healthy eye. Because of its silicone flexibility, surgeons are able to implant the iris through an incision roughly one-tenth of an inch long and with very little suturing.

“That’s not to say it’s an easy surgery; I’m folding an iris that is about the size of a cornea, which is about four times the size of the incision,” Sales says. “It’s tough to do, but it’s really beneficial for the patient. It’s a minimally invasive surgery with a faster recovery time.”

Molyneux was helping his nephews change tracks on a bulldozer in early February 2021 when he felt something hit his eye. He typically wears a pair of reading glasses when doing close work, but the inside of the machine shop was getting warm and his glasses kept slipping off his nose.

“I finally just took them off my nose and it wasn’t 10 seconds later a piece of steel came up and went right into my eye,” he says. He remembers the sting of pain but didn’t know yet that the steel was inside his eye.

His nephews loaded him into a truck and planned to take him to a local hospital, but when the truck hit a snowdrift Molyneux’s view of the world turned red.

“I turned to my nephew and told him I felt like I was looking through a window pane covered in blood,” Molyneux says.

“Iris Repair” continues on page 26

“I’m not going to tell you it’s perfect, but I went through a year of not being able to see out of that eye. And now I I can do a lot more than I could before.”

LARRY MOLYNEUX

Heather and Leon Hospodarsky’s son, Brady, was 2 years old when he brought home a manilla envelope from daycare. Inside were the results of a vision screening conducted by local Lions Club volunteers through Iowa KidSight, a statewide program based at the University of Iowa.

The test identified a potential deficiency in Brady’s vision and recommended a follow-up with an eye care professional. A local eye doctor soon confirmed their son had amblyopia, a condition commonly known as “lazy eye,” which can occur in young children when their neural pathways fail to develop.

Brady was legally blind in his left eye, limiting his depth perception and peripheral vision. Yet his parents were unaware until the KidSight screening. For the next several years, Brady’s doctor had him wear a patch periodically over his stronger eye to force his left eye to strengthen.

“With amblyopia, you have a window of time to correct the vision while the nerve pathways are developing,” Heather Hospodarsky says. “Brady was given time to correct his vision through KidSight that he wouldn’t have had otherwise.”

Since 2000, Iowa KidSight volunteers have helped thousands of children like Brady in each of the state’s 99 counties through a partnership between Lions Club of Iowa and the UI Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Sciences. Lions Club volunteers visit local daycares and preschools where they perform the free, voluntary vision screenings using specialized digital cameras. The images are then interpreted by a UI ophthalmology specialist for issues like farsightedness, nearsightedness, cataracts, muscle imbalances, and astigmatisms.

Of the 50,000 Iowa children that KidSight screens on average per year, about 5 percent are flagged for potential vision problems and referred to an eye doctor. The program has identified nearly 40,000 children with vision issues over the past 22 years. In some cases, it has detected problems that—if left untreated—could result in permanent vision loss, says Lori Short, program manager for Iowa KidSight.

“The great thing about this program is that it helps asymptomatic kids,” says Short. “Almost every single letter we get back from parents starts with, ‘I had no idea that my kid wasn’t seeing that well.’”

John Stoll, an Iowa City Noon Lions Club member who coordinates the KidSight program for Johnson County, estimates he’s screened nearly 10,000 children to date. One of the first kids he tested was his own grandson at a daycare in North Liberty. “That’s all they needed to do to get me hooked on it,” says Stoll, a retired loan officer who jokes that he now works for high fives and hugs from the kids.

Stoll still remembers one combative boy whom he chased around a daycare room during a screening with his camera. When the boy hid under a table, Stoll laid on the floor to snap a quick image. He was glad he did—the results showed that the child’s vision was poor, and he was eventually fitted for glasses. The next year when Stoll returned to the daycare, the director told him the difference in the boy’s behavior was night and day.

“They were literally days away from kicking the kid out of daycare because they couldn’t control him,” Stoll says. “He couldn’t see anything without putting it to his face—that’s the reason he was fighting anybody and everybody. He got his glasses and became the model daycare child.”

The Hospodarskys likewise count themselves among KidSight’s many success stories thanks to early intervention. Today, Brady is a high school freshman who, with the help of his contacts, has near-perfect vision. He enjoys golfing with his father and grandpa, and he plans to play for his high school golf team this spring in Alburnett, Iowa. This past fall, the family participated in the annual Whirlpool Suppliers Tournament in Amana—a golf fundraiser that brought in more than $23,000 for Iowa KidSight.

“We’re incredibly grateful for the KidSight program, the volunteers who make it happen, and those who contribute financially,” Heather Hospodarsky says. “We want to help give back too and spread the word about the program.”

Iowa KidSight is a joint project of the Lions Clubs of Iowa and the Department of Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences at the University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital, dedicated to enhancing the early detection and treatment of vision impairments in young children (target population 6 months of age through kindergarten) in Iowa communities through screening and public education.

KidSight 2022 by the numbers:

• 42,097 Children Screened

• 3,089 Screening Sessions

• 2,056 Children Referred

• 3.15 Minutes Per Child

• 121 Iowa Lion Volunteers Trained to Conduct Vision Screenings

• 2210 Volunteer Hours Spent Screening Children

• <$10 For less than $10 per child, vision capabilities can be saved!

A total of 927 Iowa donors provided corneal transplant tissue for 687 recipients in 2022. Additional gifted corneas were used for research and educational purposes to advance knowledge of blindness-causing diseases and transplantation techniques.

Only 58.47 percent of those who donated corneal tissue were registered donors. The average donor age was 62; the youngest donor was 3 years old, and the oldest donor was 101.

“Iris Repair” continues from page 23

They altered their route and headed to UI Hospitals & Clinics where within hours surgery was done first to repair the injury to the eye and remove the steel. Surgeons discovered the steel had narrowly missed the optic nerve, which meant Molyneux could possibly regain vision in that eye. First, though, the wound would need to heal, which meant his iris would remain damaged, compromising his vision.

The iris is the colored part of the eye surrounding the pupil, the small black opening that lets light in. The pupil is controlled by the muscles in the iris — when the pupil is wider more light gets in; when it’s smaller, less light is allowed in. The eye needs an aperture — a pupil — to block most of the light to which the eye is exposed. Without the iris, too much light comes in. When there is damage to the iris, or there is no iris, the pupil can’t function as it should and too much light is allowed through the eye.

Molyneux’s damaged iris was barely visible, and his pupil was very large.

“A good analogy is like trying to have a conversation in a loud coffee shop,” Sales explains, “there’s just too much noise. The same is true of light – when there’s too much ‘noise’ vision is poor and there is light sensitivity.”

With Humanoptics the artificial iris looks real, unlike previous models that appeared almost robotic. The Humanoptics model is also flexible, allowing it to pass through a much smaller incision and allow for faster healing.

For the patient, Sales says, the biggest benefit is being able to walk outside without the glare of high-intensity light.

In the year that passed between Molyneux’s initial repair surgery and getting his iris implant, he tried everything to keep the light out of his eye. He used patches, towels, bandages, and more, to no avail. He had to stop working with his nephews because he couldn’t be outside. Having lost his depth perception and his innate sense of level, operating a bulldozer and walking on uneven terrain also was difficult.

Molyneux received his iris implant in September 2022. He noticed an immediate difference.

“Since the surgery, I can now be out in daylight without dark glasses and that eye doesn’t bother me any more than the other eye,” he says. “On a scale of 1 to 10, my vision before the surgery was a 1 or 2. Now it’s probably a 6 or 7, and we can get it better with some glasses.”

His vision is better, too. Before surgery he said he could see a difference between light and dark and could make out shapes. Now, he says, he can read and write with ease, and watch his grandchildren play. Walking, working, operating equipment, and even relaxing have all improved significantly.

“I’m not going to tell you it’s perfect, but I went through a year of not being able to see out of that eye, I learned to walk with one eye open,” he says. “And now I can see. I have peripheral vision. I can do a lot more than I could before.”

That’s the outcome Sales was hoping for.

“This is one of the most gratifying surgeries I get to do,” he says. “Until you put in a prosthetic, these people are really sensitive to light, they can’t be outside on a bright day. And then you do the surgery and take the patch off the next day and they’re amazed, it’s a whole lot better. And it really is amazing.”

Sales acknowledges he would never have been able to perform Molyneux’s surgery had it not been for the ophthalmologists at UI Hospitals & Clinics who came before him. Thomas Oetting, MD, MS, and A. Tim Johnson, MD PhD, were involved in clinical trials for earlier iris prosthetic devices.

“They helped pave the way,” says Sales. “That’s one of the great parts of working at an academic medical center; we can provide patients with access to the latest advances in research and technology that can make a meaningful difference in their quality of life.”

By Molly RossiterThe University of Iowa edged up in the rankings of top eye programs according to Ophthalmology Times®. The specialty publication’s 2022 Best Programs Survey has UI up to #2 in residency education and #4 in clinical care. UI also continues to score high in the best overall program and vision research categories, ranking #5 and #9 respectively. The results are based on a survey sent by Ophthalmology Times® to chairpersons and residency directors of ophthalmology programs across the US.

More information about the survey and results: https://bit.ly/3jnPipo

IOWA VISION is published for alumni, colleagues, and friends of the University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.

Editor-in-Chief

Keith D. Carter, MD, FACS

Editors

Matt Browning, MFA Caroline Allen, MLIS

Design Benson & Hepker Design

Photography

Kelsey Hunold and other University of Iowa Health Care sources

Contributors

Jen A. Miller and Molly Rossiter (University of Iowa Health Care Marketing and Communications), Josh O’Leary (UI Center for Advancement)

Please direct comments and inquiries to Matt Browning

319-384-8529 matthew-browning@ uiowa.edu

Lisa Frank’s “Interocular Lens” presented by Nicole Radunzel, CRA, Ophthalmic Photographer. The image was awarded second place in the Eye as Art category in the 2022 Ophthalmic Photographers Society Scientiic Exhibit at the AAO 2022 Meeting and Expo. The digitally manipulated photograph of a displaced IOL was inspired by the design style of Lisa Frank.

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences

University of Iowa Health Care 200 Hawkins Drive, 11136 PFP Iowa City, IA 52242-1091

319-356-2852

319-356-0363 (fax) iowaeyecare@uiowa.edu

Appointment scheduling: 319-356-2852 – Adult 319-356-2859 – Pediatric

UI Health Access for the general public: 800-777-8442

UI Consult for referring providers: 800-322-8442

Department news, events, and information: medicine.uiowa.edu/eye

200 Hawkins Drive, 11136 PFP Iowa City, IA 52242

• Register for the Iowa Eye Annual Meeting & Alumni Reunion

• What: The Iowa Eye Annual Meeting is a chance to hear from some of the top eye doctors in the country speaking on relevant topics, earn CME credit, and reconnect with old friends and colleagues

• Where: University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

• When: June 9-10, 2023

Registration Link: https://2023-iowa-eye-association-dues. cheddarup.com