ISSUE NO.6 OCTOBER 2022 ISSN 2719-6739

SECOND THOUGHTS

EDITOR IN CHIEF

& PROOFREADING

The views and opinions expressed throughout our magazine, social media, websites, or any medium of information we send out are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Second Thoughts student club. Any content provided by the authors and graphic designers is their own opinion and is not intended to malign anyone else’s opinion or beliefs.

Yousif Al-Naddaf Dominika

Piotr Miszczuk Sanaz

Maria

Aleksandra

Jagoda Szmytkowska Katarzyna Szyszka Jan

Modesta Gorol @mosdesta.gorol Sanaz

Dominika Front EDITING

Front

Nouri

Sawicka

Socha

Ziętara Helena Żegnałek

Check out our illustrators’ social media! Jan Bodzioch @yanbodon

Nouri @ sanaznouri_art

by Laura Makuch

were chosen at random, because their source was, after all, my brain, and god only knows what had been brewing in my subconscious at the time of concocting this game. There remain many variables I couldn’t influence, however, I hope to have provided a small glimpse into the vast tangled web of associations that forms in our brains when we hear the word “water”. So if you want to play before you find out what my respondents replied, here’s my quick word association game for you to warm up:

COW (milk), WINDOW++ (bird), BUS (wheels), WATER…

— should be easy enough!

Cow, window, bus, water… Avatar: The Last Airbender.

Standing in the confocal microscope room after having spent the morning capturing respiratory syncytial viruses in bronchial epithelial cells — this is what Felipe thinks of when he hears the word “water”. Avatar: The Last Airbender is a widely popular animated television series set in a fictional world where some people can manipulate one of the four elements – water, earth, fire, air – or, in the case of the avatar, all four. Every element, of course, has its advantages. While fire benders can create fire, air and some form of earth or metal are present everywhere. On the other hand, water is a bit harder to come by; but then again, human beings consist mainly of water, so that opens up the discussion of being able to control human bodies. If he had to choose, Felipe would want to earthbend, a solid choice. He often wonders what it would be like to have some kind of supernatural

power, nothing uncommon for a dreamy, imaginative Pisces. Unfortunately, even being a water sign doesn’t protect you from seasickness. Still, water holds a special place in Felipe’s heart. From marine life (such as, to quote him, “super cool turtles”) to the calming quality of bodies of water, the sentiment can be distilled into one simple thought – water is life.

Cow, window, bus, water… Hydration.

Hydration is essential, isn’t it? So rich in meanings, symbols, and purposes, water has always fascinated Jay. Fire, its opposite element, doesn’t possess that same charm. Fire signifies heat and warmth but also destruction. It can be all-consuming, yet very fleeting, put out in an instant. Fire can kill and so can water. What Jay finds so intriguing about water is how it can kill in all its physical forms. Whether frozen, cold, boiling or even lukewarm (drowning) water can be lethal. A small gasp escapes me as I try to wrap my head around what she just said. We circle back; despite this slightly morbid turn, we did start out with hydration. Selfcare comes to mind. It might sound quite cliché, but drinking water, moisturizing your skin, and taking care of yourself on the most essential of levels can work wonders for your well-being.

Cow, window, bus, water… Potable.

Ah! Finally, a social justice warrior? Unfortunately, my conversation with Tomek was cut short before I had a chance to find out. The day before we had watched “Shark Tales” and laughed at the silly fish cracking a joke about selling bottled water in the depths of the ocean. Before I could think about this too much, our minds soon

2

drifted to more pressing questions like, how did they make that fish look exactly like Will Smith? Thinking about it now, bottled water does seem like an enormous scam. According to an article by Anaele Pelisson for The Independent from 2020, nearly half the water in water bottles is actually tap water (Nestle and Pepsi even had to alter their labels to clarify this). The mere production of water is wasteful, as claimed by the author of the article: “A recent study from the International Bottled Water Association found that North American companies use 1.39 liters of water to make one liter of the bottled stuff”. Having consumed the water, we then contribute to the ever-growing Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This one example is enough to illustrate the absolute absurdity of the concept of bottled water. Of course, I don’t mean to shame anyone for buying a bottle of water. The problem is, as always, systemic. What are we supposed to do when tap water is polluted and undrinkable? Or when there is no tap to begin with? The way I see it, blaming the individual consumer is not the way to go. Blaming capitalism and critically analyzing the systems we’ve built, however, is the right choice.

Cow, window, bus, water… Bacteria.

In an interesting turn of events, when asked to elaborate on this association, Konrad said it was what he’d said before that made him think of bacteria. After I said bus, he said puddle. That puddle made him think of contamination in water, hence, bacteria. He himself has luckily been spared from catching a

waterborne disease, although he did come close once at the “Rainbow” festival. When a bunch of hippies decide to camp near a river, it can sometimes end in a mass outbreak of dysentery (as not to slander the good name of hippies: This would probably have happened to anyone on a campground with no sanitary facilities). Despite this close encounter with a water disease, one of Konrad’s main associations remains hygiene. Pragmatic and practical as always, the first connections in his brain are the actual uses of water, not its symbolism. Water is a part of his daily routine, he tells me, you use it to wash yourself, you drink it while exercising, you can swim in it, and so forth.

Water is a topic rich in associations, symbolism, and meaning and my little game was only a prelude to this Second Thoughts edition. If you want to find out more about The Shape of Water, read Jakub Frączek’s review. Maybe gender fluidity or the navy and foreign trade are more your jam? Weronika Kubik and Marek Kobryń come to your rescue. Or rather you’re a fan of Stranger Things (well, except the last season)? Whatever the case, there’s something in it for everyone!

4 Contents: 1 Leader | Laura Makuch 6 Microplastics: “White Blanket Debris” And More? | Natallia Valadzko 10 Water, Music, and Transformation in The Ninth Wave by Kate Bush | Dorota Osińska 13 The Ebb and Flow of Gender Fluidity | Weronika Kubik 17 What The Shape of Water Gave Me | Jakub Frączek 20 Drip, Plop, Splash, and Crush | Katarzyna Szyszka 26 A downpour of pleasantries | Maciej Kościanek 27 A short history of a certain arms race | Marek Kobryń 29 The Lament of the Reeds | Konrad Zaręba 31 Come Hell or High Water | Sara Bonk 33 Dry Summer: This is how we go out | Samet Eray Karakaş 35 Was the alliance between Australia and the United States inevitable? | Marek Kobryń

5

I can’t finish thi-

Microplastics: “White Blanket Debris” And More?

Natallia Valadzko

Natallia Valadzko

These are the opening lines of Evelyn Reilly’s poetry collection Styrofoam published by Roof Books in 2009. It is a mesmerizing case of ecopoetics that explores the multitude of plastic polymers and the environmental dangers they pose. Reilly draws parallels between artists and scientists, especially with respect to how plasticity – of materials or the human brain –has been greatly celebrated. While neuroplasticity may stand for many forms of creativity, the plasticity of thermoplastics has made a ton of life-changing applications possible in distinct areas of life. The more evidence – first-hand and scientific – comes to light, the more we acknowledge the detrimental environmental effects of “our infinite plasticity prosperity plentitude” (to use Reilly’s words).

But what about us as subjects? Styrofoam additionally expresses the wariness that extends to the artistic and intellectual traditions that may have been cultivating

environmentally destructive orientations. The poet uses a mode of collage and citations that range from Ezra Pound and Herman Melville to articles from Wikipedia and the Food and Chemical Toxicology journal to reflect on the relationship between humans and nature, or matter in general.

Nowadays, we see consumers and manufacturers attempt to cut down on single-use plastics and find sustainable alternatives, and yet the question Reilly asks in the beginning could not be more relevant, especially if more answers sound like this: Answer: It is a misconception that materials biodegrade in a meaningful timeframe

Answer: Thought to be composters landfills are actually vast mummifiers [of waste]

Indeed, the notorious disproportionate time of use and decomposition of plastics may seem tragically ridiculous. Plastic packaging may prove useful for mere hours and then be destined for deathlessness by ending up in a landfill— a “mummifier of waste”.

6

“Answer: Styrofoam deathlessness Question: How long does it take?”

The mention of being outside “a meaningful timeframe” can make one think of the concept of hyperobjects. It is roughly defined as objects or events which exist in such temporal and spatial distribution that they evade human conception. That is why an important aspect of hyperobjects is that they are bound to outlive current biological and social forms (think: us!). Morton, who coined the term, gives examples of global warming, Styrofoam, and radioactive plutonium. You really need a distorted sense of time in order to wrap your mind around the life and (non-)death of thermoplastics, which, on top of that, are scattered all around the world in vast quantities. The unfathomable reality of plastics, radioactive materials or climate change may be hard to grasp as it keeps eluding us; the fact of the matter remains that it is the reality that has been affecting our biosphere, down to the cellular makeup of living beings. Although plastic islands in the ocean are a serious and undoubtedly horrifying problem, they are visible to the naked eye. What about the things we cannot see? Shouldn’t we be even more terrified when the basis for concern bypasses perception but would not stop the consequences? What I mean is… microplastics. As the name suggests, they are tiny plastic particles, which come in different shapes and sizes, and are mostly indiscernible to the human eye (officially, less than five millimeters in diameter). Where do they come from? Primary microplastics are particles designed for commercial use, for example, cosmetics and microfibers shed from clothing. Secondary microplastics are a result of the breakdown of larger plastic items, such as water bottles. As per an estimation made by oceanographers in 2015, there were between 15 and 51 trillion microplastic particles floating in surface waters

globally. Interestingly enough, littering or irresponsible waste disposal is not the only one to blame for such terrifying numbers. Storms, water runoff, and winds can carry both plastic objects and microplastics into the oceans and local bodies of water. Or another reminder that nothing “really” stays the same: plastic specks shear off from car tires on roads and synthetic microfibers shed from clothing when machine-washed. In short, in recent decades researchers have discovered microplastics everywhere: deep underwater, in Arctic snow and Antarctic ice, in marine animals, drinking water and even cells; floating in the air or falling with rain over cities. This ubiquity of microplastics means we might be inhaling or eating plastic at any time from any source.

Everyone breathes in and ingests a bit of dust and sand, and we are not certain if adding some plastic specks will harm us. This uncertainty has fueled an already quite extensive body of research into the several ‘hows’ in connection to microplastics. For instance, scientists are interested in “how much”. In other words, working together with regulatory institutions, they want to quantify the danger to human health by, for example, measuring microplastic concentrations in drinking water. Another ‘how’ is aimed at uncovering the effects of microplastics on animals and humans. How do specks of plastic affect us once inside? Here are just a few tentative suggestions because more research needs to be conducted. As there exist nanoplastics so tiny that they can end up in cells and tissues, it is likely that they may cause irritation or lung tissue inflammation leading to cancer. Similar to the mechanics and consequences of air pollution, these specks may build up in airways and lungs, which is linked to the damage of respiratory systems. In addition, as seen in marine animals, serious but not

7

immediately evident harm can be done by swallowing plastic with no nutritional value resulting in animals not eating enough. One study concluded that turtle hatchlings, only a few weeks old, did not die directly ‘because of’ ingesting microplastics but because of the insufficient speed of growth. Moreover, zooplankton is said to grow more slowly and reproduce less in the presence of microplastics. This, in turn, can travel up the food chain and affect other animal populations, posing dire threats to biodiversity and even feeding the world’s population.

One final point is devoted to the challenges of such research. In marine studies, for instance, labs have used microplastics of sizes and shapes that are different from the aquatic environment. There has been an over-reliance on sphere-shaped polystyrene at higher concentrations, while the more accurate sample would also include fibres and fragments; not to mention the ever-soelusive nanoplastics. This brings us to yet another obstacle: looking at particles larger than 700 µm already requires tremendous effort, then what can be said about analyzing an even smaller range? And finally, as most studies are in vitro studies, it is still unclear how to extrapolate the impact of microplastics on tissues to potential health issues in whole animal organisms.

In the end, let’s hark back to the quote in the title: “white blanket debris”. Reilly mentioned that the collection is haunted by Coleridge’s “the Rhyme of the Ancient

Mariner” and “The Whiteness of the Whale” from Moby Dick. The echoes of death, whiteness, and the sublime abound across all the poems. The death of an albatross is complemented by the mention of the killing of a humpback whale by a cruise ship. Additionally, if for Melville’s contemporaries whiteness was so disturbing and eerie that it “struck panic to the soul”, then one could only imagine the horror of being amidst “the white blanket debris” of plastic islands. Yet, these allusions do not extend the traditions by which they were inspired; instead, there is caution around Romantic and Transcendentalist ways of thinking. With ecopoetics she hopes to find the language to break free of “the mesmerizing spell of the transcendent”. Her anti-sublime stance is about moving past the deified nature and the attempts to separate from this world, go further or higher. Even space debris (or “the extra-terrain garbage” in one of the poems) floating in space is the result of a human’s desire to escape earthly existence. In contrast, ecopoetics or simply environmentally conscious thinking would stay attached to the earth and focus on the (inter-)connections between species and their surroundings. So, to reiterate, both scientists and artists deal with manipulation of matter: modeling and remodeling thermoplastics, on the one hand, and assembling and reassembling the components of certain world order, on the other. It means that we have to not only find more sustainable solutions to

8

current environmental crises but also rethink our fascination with cheap but deathless plasticity of chemical production, fast fashion and a cornucopian view that technology (and not protection and regulation) would “solve” all environmental problems.

One of the responses to the current ecological events has been named eco-anxiety or even eco-grief; and perhaps fighting that kind of despair is becoming harder and harder with each devastating

headline. In Styrofoam there is also a certain degree of elegiac grief but, most importantly, there is a call to bear unwavering witness. By witnessing all the harm to the environment, we do not turn away from the clash of the “white blanket debris” and the endangered polar bears. We bear witness. We keep looking and looking at ecosystems being altered right in front of our eyes, look for (micro)plastics and their repercussions, look after what is right here, on earth, globally and locally.

Water, Music, and Transformation in The Ninth Wave by Kate Bush

Dorota Osińska

As a lost teenager, I was constantly looking for cultural manifestations of water. My old but long-lasting fascination made me explore this trope for months. Finally, I encountered Kate Bush – a British singer and songwriter – and her 1985 album, Hounds of Love, with its second part called The Ninth Wave. Now, Hounds of Love is experiencing its renaissance. A song from that album, “Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God)” was used in season four of Stranger Things’ soundtrack – I couldn’t have known it was going to happen because I wrote this text a month before the season’s release. But I’m really glad that Kate Bush’s songs have become incredibly popular, widely beloved, and generally appreciated by younger generations of viewers and listeners. Indeed, “we’re letting the weirdness in” (as she put it in “Leave it Open” from The Dreaming) into the mainstream. And it’s wonderful!

Although Stranger Things used Bush’s music to capitalise on nostalgia for the eighties, her music still continues to communicate something intimate and deeply empathetic. Not only do the protagonists of her songs look at political issues (“Army Dreamers,” “Breathing”) but they also deal with existential crises (“Suspended in Gaffa”, “Sat in Your Lap”), love (“The Wedding List”, “All the Love”, “Houdini”), and womanhood (“This Woman’s Work”, “The Sensual World”). Yet, the most captivating element in her works remains the theme of water. Despite its coldness and rawness, it offers comfort and an uncanny sense of overwhelming embrace.

Hounds of Love conveys the complexities of transformation weaved into watery imagery. After the commercial failure of its predecessor, The Dreaming (1982), Bush retreated to her studio in the countryside and investigated what would happen if a woman got lost in the water. Hounds of Love consists of two parts: the first half deals with different facets of love – fear of love, miscommunication in relationships, parental love, and affirmation of nature. Although the whole album represents a masterclass in storytelling, the water imagery reverberates only in the second part of the record, demonstrating a harrowing vision of being in the water.

The other half of the album, The Ninth Wave, tells a strange, nearly cinematic story of an individual transformation through, in, and because of water. It opens with the imagery of a girl floating alone at night in the ocean. The first song, “And Dream of Sheep”, shows her fear of the ocean depths and of not being found. She is fighting the urge to fall asleep (“I’d tune into some friendly voices/Talking ‘bout stupid things/I can’t be left to my imagination”), and lingering in the intermediate state between life and death (“Like poppies, heavy with seed/They take me deeper and deeper”). However, the exhaustion overtakes her and water lulls her into slumber. Death seems better than the constant struggle for survival in the cold harsh sea.

Water slowly reveals its destructive tendencies in “Under Ice,” where it traps the protagonist and discloses the oppressive

10

realisation of her drowning. In the Classic Albums Interview aired in 1992, Bush mentioned that “it’s the idea of seeing themselves under the ice in the river, [...] [realising that] “my god, it’s me,” [...] “it’s me under the ice!”. This terrifying awareness shifts in “Waking the Witch” into the fantasy of a witch trial. It begins with a series of callings trying to save the girl from succumbing to deadly waters. “Waking the Witch” makes a reference to historical hunts during which an accused woman underwent ‘swimming’, a test that would determine if she was a witch. Yet, the nightmarish vision of the soul’s judgement is interrupted by a helicopter that rescues the girl from the ocean.

Being in the water for too long, sensory deprivation starts kick in and the girl loses all sense of where, when, and who. Appearing as a ghost in the next song, “Watching You Without Me”, the girl tries to communicate with her family again and again. The blipping Morse code for SOS and the distorted voice on the record – “Listen to me!/Talk to me!/Help me! – convey a desperate need for connection and its ultimate breach. They cannot hear her entering the house, nor can they hear her leaving it. Identifying herself as a ghost and watching her beloved anxiously waiting for her, the character floats between this world and the other. She laments that “[she] should have been home hours ago/But [she’s] not here” and she cannot let them know what has happened to her. Here, water is a dividing element in both the physical and psychological sense as it triggers the descent into one’s head, heart, and imagination.

Despite its bleak beginning, The Ninth Wave also offers glimmers of hope. As “Jig of Life” illustrates, with the recognition of

darkness, uncertainty, and terror comes a reassuring push-and-pull fight for life that explodes into a dancey jig. The singing persona is an older heroine who scolds the protagonist in the water for giving up and convinces her younger self that it is not her destiny to drown (“C’mon and let me live, girl!”). In the context of the previous songs, the protagonist survived the trials of death and is ready to look out for what the future holds for her. A similar life-affirmation that water provides is also present in “Hello Earth”, the penultimate song of the album, where the ocean’s magnitude overwhelms the girl. As Bush admitted in an interview with Richard Skinner: “and the idea of [the character] looking down at the Earth and seeing these storms forming over America and moving around the globe, and they have this like huge fantastically overseeing view of everything, everything is in total perspective. And way, way down there somewhere there’s this little dot in the ocean that is them.” In that sense, the vastness of water makes her notice the vulnerability of her life.

Although water is absolutely terrifying, the horrors of death, life, and rebirth she experienced are universal and even essential to see beyond one’s narcissism. An individual, in the face of the water, is just a little speck of dust. Nevertheless, the realisation is not infinitely depressing but rather a comforting one. The final track, “The Morning Fog”, is a paean of how water – the transformative force that is neither inherently good nor intrinsically bad – made her appreciate her loved ones. Ultimately, without descending into the depths of the water, she would not

11

have experienced the light of love and relief, changing the tragic into the beautiful. While in “Hello Earth,” the woman is drifting into space being overwhelmed by the enormity of the experience, “The Morning Fog” shows her being grounded by the situation she faced, learning the lesson of love, not bitterness: “I’m falling/And I’d love to hold you now/I’ll kiss the ground/I’ll tell my mother/I’ll tell my father/ I’ll tell my loved ones/I’ll tell my brothers/How much I love them.”

Bush’s album skilfully frames water symbolically, historically and pop-culturally: the art of musical storytelling is accompanied by the symbolic dissection of the trope of water. With a peculiar blend of empathy, darkness, and gratitude, The Ninth Wave serves as an intriguing example of how mutability should not be perceived as a dangerous force but

as a positive, or even a necessary one. Water is dangerous; there is no doubt about that, but without its transformative qualities, there would be no maturation of the individual. Since antiquity, the abyss of water has been a symbol of wisdom – mysterious, unfathomable, yet regenerative in its nature. Paradoxically, the threat that water poses functions as a catalyst for maturation.

As the beginning of The Ninth Wave depicts, the destructive potential of water reveals what is indeed important for the individual trapped in dire straits, which is the connection to other human beings. The nightmarish experience of being alone in the cold dark waters changes into the tale of appreciation of the people we love, communicating the life-affirming message: despite the tragedy, keep going.

12

The Ebb and Flow of Gender Fluidity

Though gender is usually defined as a person’s individual identity of fitting somewhere along the male-female spectrum, in a socio-cultural context, it is understood as a set of characteristics, roles, and behaviors which do not necessarily correspond to a person’s biological sex. Identifying with a particular gender generates certain societal expectations, or even harmful stereotypes, dealing with which can be a daunting task. Sometimes gender can be like water – ebb and flow in an unrestrained manner, changing forms and directions. So what if a person does not feel connected to one specific point on the gender spectrum? Well, it might be a sign that they are genderfluid.

Gender fluidity is an identity which falls under the non-binary umbrella, meaning that genderfluid people do not see themselves as strictly male or female. Moreover, their gender identity and expression are not static, but change over time. These changes occur only in identity, only in expression, or in both areas simultaneously. As for the frequency of the fluctuations, there is no set pattern – they can happen every few months, once a fortnight, or even from day to day. To somebody whose gender is fixed, such recurrent changes may seem rather confusing, but how does it look from the perspective of a person who experiences them firsthand? What made them question their gender identity?

community. This also proves to be of great importance on the road to self-discovery for many people, especially those who live in more conservative countries, where access to queer-centered media is limited. For example, at the moment of writing this article, the Polish LGBTQIA+ community has access to only one printed magazine concerned with queer issues, Replika, and one bookstore focused on queer literature –Księgarnia Stonewall located in Poznań.

Finding a term that describes one’s gender is by no means the solution to all the troubles. It can raise even more questions, as well as cause confusion or anxiety, if a

According to the annual report prepared by Transgender Europe, in 2021 alone, as many as 375 non-cisgender people had been murdered. Compared to another report drawn by the same organization based on 2020 data in that matter, 12 cases have been reported, indicating an increase of 3025%.

It is important to note that these numbers represent only reported deaths, while the total number of gender-diverse lives that were taken is possibly much higher. Apart from these extreme, tragic cases, many queer people deal with verbal and physical violence on a daily basis.

It can be assumed that at least a part

actually realized that even the closest people in my life feel the need to put me in a box of being a woman, and that I don’t fully fit in it.”

Still, figuring out one’s gender identity more often than not leads to changes which are difficult to conceal: new outfits, fanciful hairstyles, braver make-up looks. Generally speaking, the realization of who you really are comes with an unparalleled sense of confidence and freedom, as well as with the courage to express yourself in ways that seemed daunting before. Many queer people choose to challenge the gender stereotypes with their style. Jay stated that their gender expression changed drastically after they embraced their gender fluidity. One aspect of this transformation that was particularly meaningful and liberating was shaving off all her hair because they had wanted to do it ever since they had been a young teenager but were afraid of what people would say. To prove the point about the healing influence of refusing to conform to gender stereotypes enforced by the society, they recalled how their androgenous, buzzcut-rocking self altered the way people looked at them, and how welcome this attention turned out to be. Additionally, there were the people close to her who greeted the change with an enthusiastic attitude and unwavering support. Luckily, many people approach diversity with fascination and love rather than with fear and hate.

It is important to remember, however, that not everyone has good intentions –something most women and queer people are painfully aware of. As soon as you are perceived as “the weaker sex” or your gender expression differs from “the norm”, you can never feel completely safe in public

places. While some people are simply trying to take advantage of and hurt their fellow humans, the hostility displayed by others can be attributed to the lack of education and exposure to members of the queer community. In Poland, the insufficient representation of the LGBTQIA+ community, especially of the identities encompassed by the non-binary umbrella, is largely caused by the irrational fear of the “rainbow propaganda” displayed by the conservative part of the Polish society. The criticism of the majority of the government and attacks of the right-wing groups prevent fair queer representation in media and public spaces from becoming widely accepted. Fortunately, non-governmental organizations, such as Miłość Nie Wyklucza, Grupa Stonewall, Kampania Przeciw Homofobii, and several others, are fighting for the rights of queer people in Poland. On top of that, every June many cities host Pride Parades, the biggest of them being Parada Równości (‘the Equality Parade’) in Warsaw.

These efforts are met with the backlash of the conservative Poles. It seems that the idea behind trying to silence the LGBTQIA+ community is that if people will not see queerness, they will not question the boxes that we are all put into, but… “The thing is they do. They do question their identity even though they don’t see queer representation because they feel that something is wrong, that something is different,” commented Jay. “I didn’t question my gender identity nor my sexuality for the first 18 years of my life, or 20 even. So maybe if I had seen some people who didn’t really fit into one or the other category, I would’ve found myself earlier.

15

I had no clue that I could identify with something else.” One can not stress enough the importance of truthful, inclusive representation. Many people who are not cisgender and heterosexual struggle with self-acceptance and with fear of being rejected by those around them. Seeing someone like them in the media or in public would show them that there is nothing wrong with them, that they deserve love and respect just like everyone else. It is crucial especially when it comes to young people, as they are less prepared to deal with these struggles on their own. According to the report published by Kampania Przeciw Homofobii, 28.4% of queer people display symptoms of depression. The most alarming data pertains to the ones that are the future of our society – among the respondents under 18 years of age, 49.6% suffer from depression and 69.4% reported experiencing suicidal thoughts.

The situation of the LGBTQIA+ community in Poland is not good,

but as long as we do not give up and keep up the hard work, there is hope that things will improve. The people who identify as non-cisgender are in a particularly difficult situation, as they are strongly under-represented and have to constantly struggle against harmful gender stereotypes. Therefore, it is pivotal to give a platform to gender-diverse voices, such as Jay. When asked if they would like to share any parting words with those who are just starting to explore their gender identity and expression, Jay had some simple yet valuable advice: “Just take your time and don’t worry about it too much. Also, if you choose to identify with some label, you don’t have to stick to it throughout your whole life. Everything changes, your gender identity can change. Take it easy and give yourself a lot of time.” As the generations of queer people before us, we have to be proud of who we are and persevere in our fight for a more just, tolerant world.

16

What The Shape of Water Gave Me

Jakub Frączek

Directed by Guillermo Del Toro, The Shape of Water tells the story of a mute cleaner, Elisa Esposito, who falls in love with a humanoid amphibian creature and tries to save it from the American government. Their tale is narrated by Elisa’s friend, Giles, who has difficulties finding a job and fitting in society due to his sexuality. Without a doubt, the film was polarising – many of its critics accused it of being too literal and outright repulsive because of the nature of the main romance. However, the fans praised the stunning visuals, impressive score, overall atmosphere, and exploration of the theme of likeable misfits who try to help one another face the brutal reality. Regardless of the contrasting opinions, the movie is undoubtedly made with love for cinema. It is full of references, tropes, motifs, and ideas that deserve to be discussed. In terms of analysis, the amount of angles is unlimited; from the obvious nods towards the Creature from the Black Lagoon and classical monster movies, through the reinterpretation of the fairy tale genre, to simply being a heartfelt story about being the “other” in our society.

It is easy to misinterpret the role of water in the story or reduce it only to the representation of the Amphibian Man. Yet, as it can be expected from a movie by Del Toro, every nuance has been polished to perfection. The eponymous water is omnipresent, framing the world even through small details and adding another remarkable layer to the story.

In an interview, Del Toro himself claimed the Amphibian Man as the shape of water. Having that in mind, water can be defined with regard to this godlike creature who lives in parts of the Amazon which are unknown to our civilization. Devoid of prejudice, it is a place of primal, natural freedom. This is directly contrasted with the man-made world, which is full of constraints and short on regard for those on the margin.

Stuck between these two worlds is the main character, Elisa. Though physically she is a part of the human world, the film from the very beginning gracefully indicates that she hardly fits in. The first scene shows Elisa’s room as if it was underwater, with her and her stuff floating loosely. In the next scene, the camera follows our protagonist through her daily routine, including boiling eggs or masturbation in the bathtub.

Since one’s dreams, desires, and sexual activities are considered intimate, especially given the story is set in the 1960s, it can be argued she has a special connection with the free-flowing water.

It is important to note how Elisa keeps track of time with the help of an egg timer. Since eggs are what Elisa gives to the Amphibian Man to establish their relationship – and shots of the eggs reflect the shots of her in the bathroom – eggs represent their relationship and its sexual nature. Their boiling shows how Elisa’s feelings are changing and how she doesn’t think of the creature only as a friend. Finally, it makes perfect sense for

17

18

when he interrogates and tortures Bob, one of the scientists in the lab with a friendly approach towards the creature. Strickland’s true psychotic nature takes over his usually calm persona and he ssutains catharsis by way of water. He symbolises our world, which is a world of fear, discrimination and hate, where people like him can gain whatever they want. In such a place, the Amphibian Man would be unable to survive, both literally and metaphorically. The creature is too good, too trusting, and too understanding to be able to live in the human world. Similarly, Elisa has to discover that she has much more in common with what’s underwater than what’s above it. One may say that The Shape of Water is a “fish out of water” story, or rather a “human out of water” story.

All of those indications would not be half as powerful without the tremendous work of the cinematography crew and the score. The usage of blues and greens as the dominant lenses of the film gives it an underwater feeling, simultaneously grounding it in the world and reminding us that it is a fairy tale with water as the focal point. Yet, it never feels unreal or disingenuous. The picture is complemented by the music composed by Alexandre Desplat. This Oscar-winning score tries to capture the sound and feeling of warm water through wave sounds and the usage of

flutes and accordions. This results in lengthy, blurred melodies which sound like they can be heard from a distance or under the water. As Desplat himself said: water is the driving force of the movie.

A fair number of people put the movie’s simplicity against it. In a review for New York Vulture, David Edelstein called it “a complacent movie, too comfortable with itself to generate real dramatic tension”, while Armond White argued the main romance is “pervy, ridiculous, and humourless”. I do believe, however, that its power lies in its simplicity and corniness. At its very core, The Shape of Water is not overly intellectual – its focus is not on a tightly written plot or ethos deconstructing. It is an adult fairy tale made for anyone who feels like they do not belong. No matter the reason, it assures you that you will never be alone and that you can find someone who will care about you, even in the strangest of places. It remains one of my favourite movies, which showed my 18-year-old self how beautiful art can be. Without bitterness or pessimism, The Shape of Water is a melodrama full of emotions, which reinvented my understanding of the medium and strengthened my deep affection for cinema. And I am more than grateful that in the cynical world we live in, Guillermo Del Toro is still dedicated to making movies that are shameless, earnest and unafraid to go underwater and tell their own story.

19

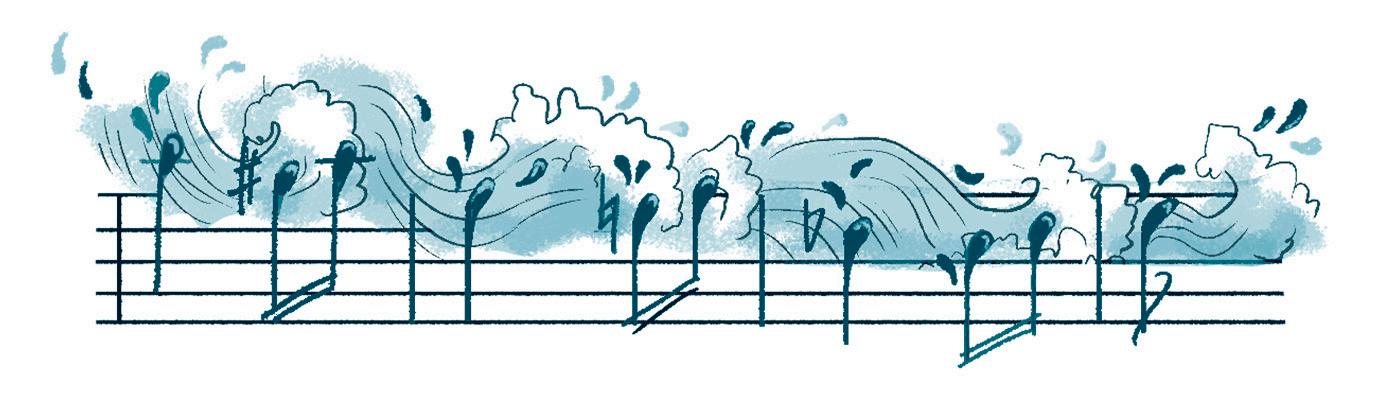

Drip, Plop, Splash, and Crush

This article has its own official playlist, scan the QR code to listen:

Understanding music in terms of water is a prevalent cognitive metaphor in many languages. We like to say about music that it flows, washes over, and we’ve compared it to a wave long before we knew it physically is one. At the same time, the evocative power of music to paint images, depict phenomena, convey feelings, and render impressions makes it one of the few universal art fields, or even communication media. So, here is a conundrum for you: if we commonly conceive of music as water, how can water be portrayed by means of music?

Household chores

Think about Disney’s 1940 music anthology Fantasia, specifically the segment with Mickey Mouse as the sorcerer’s apprentice, getting into trouble with the sounds of Paul Dukas’ symphonic scherzo. The musical piece, strictly based on Goethe’s ballad “Der Zauberlehrling” is a fine example of program music – a type of instrumental music that strives to render an extra-musical narrative. Here is the sorcerer’s apprentice, left alone in his master’s workshop and tired of performing chores. He enchants a broom to get water in his stead, realising only too late that he does not know how to stop it. Desperate, he chops the broom with an axe, only to find out that each splint continues to fetch water on its own, quickly flooding the workshop. When the situation seems hopeless, the master comes back, puts an end to the spell and scolds the young magician.

Fascinating as it is, we don’t have the time to unpack all of Dukas’ brilliant ideas and his mastery over the musical imagery in L’Apprenti Sorcier, but the depiction of water alone is a testimony to it. The stream

Katarzyna Szyszka

of water pouring out from the bucket seems almost tangible to the audience due to the musical motif repeated throughout the scherzo by flutes and strings: a longer note, followed by two shorter ones, ending on another longer followed by two shorter, etc., with the melody descending gradually, like water being spilled from the bucket in waves.

As the water is rising and the apprentice begins to panic, the rhythmic values get shorter, producing the effect of acceleration, and the musical passages start going not only down but also up, suggesting a shift in the water’s movement – from a stream to waves flowing around the workshop.

The transitions between the passages going up and down become less and less frequent, imitating the growing size of the waves, which take longer and longer to change the direction of their movement. The tide rises higher and higher, with an occasional crash of clash cymbals signalling the wave crashing against the walls of the workshop.

20

When the broom’s splints take up the work again, the pace accelerates and the musical figures representing water increasingly overlap. Upon the master’s return, there is a sudden silence, after which the strings reassume their initial motif. This time, it sounds as if the water was receding and draining away.

effect comes from a music figure akin to basso ostinato; a bass line repeated as the basis of a piece. Chopin’s rainy ostinato comes in the form of a single note repeated in a monotonous rhythm throughout the piece, its pitch changing only as required by the harmony. In the calmer initial and final fragments, the single note is quiet, connoting the innocent, if not a slightly irritating sound of dripping.

It would seem that the quality of water that Dukas exploits the most is movement. But it is not only in L’Apprenti Sorcier that classical music shows off its potential to depict this and other aspects of the element of water. If you are curious about the other ways in which composers conjure up the most aquatic sounds, let me invite you to a subjective review of a few more iconic and very wet music pieces.

Precipitation

Rainfall is one of the classical composers’ beloved water themes, and not without a reason. The phenomenon produces a wide range of noises on its own, making its musical imitation a work of a keen listener and skilled artisan, rather than that of an imaginative inventor or demiurge. But its diversity results in a wonderful rainbow of contrived sound effects.

Fryderyk Chopin’s “Raindrop” piano prelude, allegedly dubbed so by the composer himself in the notes of one of his students, was created as a “translation of nature’s harmonies” – a musical interpretation of the persistent sound of rain droplets. The

In the turbulent middle fragment, the trickle turns into a deluge. The ostinato, amplified by the louder dynamics and the addition of an octave, comes to the fore, taking over the melody, backed up by strong bass chords.

Claude Debussy, master of water music, is the composer of a beautiful rainstorm piece as the third movement of his piano suite Estampes. Jardins sous la pluie, or Gardens in the Rain, presents a garden in a Norman town during a downpour. The feeling of restlessness of the torrent bathing the garden comes from the constancy of very quick downward or oscillatory passages pervading the composition. When the highest sound in a passage is a two-note chord, its clarity and brilliance are brought out, imitating specks of light caught in the water streams, or the splatter made by the raindrops falling onto the garden foliage.

21

Chromatic and whole-tone scales interlace with the harmony. As these symmetrical harmonic systems lack tonality (a sense of directionality and presence of a central note – tonic), their use produces the effect of an endless musical pattern that does not lead anywhere and whose end is arbitrary, brought about by a set of circumstances rather than by its inner logic – much like the rain itself.

To end on a high note, we’ll conclude this part with Antonio Vivaldi’s portrayal of a hailstorm in his most famous group of violin concertos. Le quattro Stagioni were published with accompanying sonnets, possibly written by the composer himself. The lines that go with the final movement of the third concert, Summer, read:

Alas, what’s more, his fears are justified: the heavens thunder loud with hail-filled rain, cutting the heads from stalks of wheat and grain.

(trans. Armand D’Angour)

The depiction of the cataclysm, foreshadowed by sudden bursts of sound in the previous movement, combines the elements described in the earlier mentioned pieces – a cavalcade of downward passages and an ostinato. The former takes the form of scales being repeated, passing from one instrument part to another, feigning the falling of hailstones, while the latter is played by all the other instruments, creating a booming sound of the stones hitting the ground. The effect is amplified by chords played by the harpsichord on the first measure of each bar.

The minor scale of the piece makes it sound dark and grim, and its periodic structure (divided into short symmetrical units) is underlined by general pauses between particular phrases, magnifying the dramatic effect.

Courses and reservoirs

While the rain might be more evanescent and elusive as an inspiration, rivers, lakes, and seas provide a solid, stable model for the composers to draw musical ideas from. The currents, tides, ebbs and flows all find their way into the sound landscape, like in An der schönen, blauen Donau by Johann Strauss II, where the flow of the river is transformed into an elegant triple time and swaying rhythm of waltz.

Another famous river music is Bedřich Smetana’s symphonic poem Vltava. The piece belongs to a set of compositions titled Má vlast (My Fatherland) – a work of 19th-century nationalistic music, depicting various elements in Bohemian history, countryside, and legendarium. The

22

recurring motif of the river itself in the poem, although kept in triple metre, so tempting for composers for its gentle rocking motion, differs from Strauss’s elegance and lightness – the breadth of its phrase suggests a more stately and proud character of the Vltava River.

Its course is painted with sounds in stages, starting from two rippling mountain springs depicted by two lively, winding melodic lines played by flute and clarinet.

The springs then turn into a stream, and finally, a river, winding through the country and eventually disappearing into another river. Vltava’s course is rendered through a procession of miniature scenes: hunters portrayed by a horn melody, a peasant wedding resounding in the folk polka rhythm, water nymphs bathing in the moonlight, depicted as a tangle of playful melodies played by woodwinds against a dreamy backdrop of strings, and finally, the sound of a regal hymn symbolising the Vyšehrad in Prague.

Moving on to a bigger body of water, and a bigger composition, we reach La mer –another work by Debussy, captioned “three symphonic sketches for orchestra”. Striving to break free from the bluntness of direct musical onomatopoeias, the composer captures impressions instead, painting the

sea in the morning hours, its play of the waves, and the dialogue between the wind and the waves. The phrases creating the surface layer are constantly interrupted, giving in to the inner tide – harmony and rhythm. Their colour and harmonic progression are more important than their pitch and the melody it creates, giving the work its impressionistic character and reflecting the fickle character of the sea. The tone depth and ambitus (the range between the highest and lowest note), in turn, show its abyss and expanse. The composition was also inspired, among others, by Japonisme. The cover of the score’s first edition was based on Hokusai’s woodblock print The Great Wave off Kanagawa, and the tonality of the piece is extended by the heavy use of atonal, exotic-sounding scales.

Frolics and visions

I hope you still have room for dessert. On the menu: compositions revolving around the idea of games, playthings, fables, and dreams. Full freedom of expression and imagination running wild included in the price. Enjoy your meal!

Debussy (again!) plays skilfully with sounds that evoke such appearances. One example is the piano prelude La cathédrale engloutie (Sunken Cathedral), based on a Breton myth, in which a sunken cathedral rises from the sea on clear mornings when the water is transparent. According to the legend, one can then hear chanting, organ, and bells ringing. Apart from rendering these sounds, the prelude emanates

23

The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Hokusai

grandiosity, and the progressions of octaves or chords, on which its structure is based, can be interpreted as a portrayal of both the cathedral and the depths and clearness of the sea waters.

The sound of harp is also evoked by swift single-note arched figuration, resembling the shimmer and sparkle of water.

Also, in Reflets dans l’eau (Reflections in the Water) from the piano suite Images, the musical material depicting the reflected imagery is accompanied by figures representing water itself; arching passages of chords create the impression of water surface, rippled by circles slowly drifting out.

Shimmering appears also in Maurice Ravel’s repertoire. Ondine, the first movement of the piano suite Gaspard de la nuit, is based on a poem about water nymph Undine, who, through singing, seduces the observer into visiting her kingdom at the bottom of a lake. The nymph’s song resounds to the colourful sounds of water falling, flowing, and cascading. They are explicit in the trill-like figuration alternating between fast repetitions of a single note and a chord, opening the piece.

A similar effect is produced by arpeggios – broken chords, whose notes are played quickly, one by one (the term stems from the Italian word for harp playing).

Again, the arched passages entangling the main melody resemble the effervescent and light-catching qualities of water.

Another aquatic composition by Ravel is the miniature Jeux d’eau (Water Games), possibly inspired by the poem “Fête d’eaux” by Ravel’s friend Henri de Régnier. A line from the poem was inscribed by Régnier on Ravel’s manuscript, at the composer’s request: “river god laughing at the water that tickles him”. In the miniature, Ravel uses a wide range of

24

the piano’s register, presenting water depths, as well as rising mist. The opening passages accelerate now and again, resembling water being spilled or whirled.

The free, improvisational figurations, rich in ornaments like trills and glissando (a glide from one pitch to another) give the piece a water-like brilliance.

The glittering wave-like background is joined sporadically by a glissando played on the glass harmonica – an instrument rumoured to “plunge” musicians and their listeners “into a nagging depression and hence into a dark and melancholy mood” (at least according to musicologist Johann Rochlitz in the periodical Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung).

Fast repetitions of single notes or whole phrases are like dripping droplets, similar to Chopin’s “Raindrop” prelude

The last and potentially most evocative composition is Camille Saint-Saëns’ Aquarium, part of the illustrative chamber suite Le Carnaval des animaux (The Carnival of the Animals). The melody played by the flute and strings is accompanied by glissando-like runs and arpeggios played in two different rhythm patterns on two pianos.

The unusual instrument’s bright and magical timbre gives the piece its unique sound, imitating the water microcosm.

25

A downpour of pleasantries

It’s always raining. It’s cloudy. And if you go out, an umbrella is mandatory. People who have never experienced life in Great Britain may think that the weather there is terrible. Is it true, however? Not necessarily. The weather is as diverse as the country’s culture and dialects. Hence, if you are planning to visit Great Britain, you need not worry about the weather so much.

Looking at the map of the UK, we may deduce that the weather is generally wetter on the west than on the east coast. The Gulf Stream brings warm water from the Caribbean to North West Europe. Many mountains on the west coast of Britain cause westerly winds to rise, which cools the air and consequently contributes to the formation of clouds. Thus, the west of Britain is more likely to receive rainfall as opposed to the east.

When moving to Britain, or simply coming there on holiday, you should indeed prepare yourself for a slightly different aura. The English climate is quite temperate, much more so than, for example, that in Poland. This means that winter in Britain is relatively warm, thanks to the Gulf Stream. During winter the average temperature is a little over 0oC, whilst it hovers around

18oC in summer, making it not as rainy as many people would think. You may expect to experience “four seasons in one day” but of course it may be grey and gloomy, plus it rains at times, just as in any other European country.

Similar to how local weather clichés are not totally accurate, neither is the assumption that the ordinary Englishmen only talk about the weather. It is a question of culture. When it comes to icebreakers in Europe, usually the only form of fulfilling this courteous duty is through shaking hands and introducing oneself. The Englishman, however, will also ask the other person how they are and soon after receive a wellworn answer: “I’m OK.” The next step is making small talk. At this point, the weather comes to the rescue as simply another exchange of courtesies.

Some people love this weather, others hate it. The Met Office, which monitors and forecasts the weather for the UK, suggests that there are eleven distinct weather regions in Britain. This makes the UK an exciting and fascinating place to explore. It may be unpredictable, but at least it is never boring!

26

Maciej Kościanek

A short history of a certain arms race

Marek Kobryń

It might be surprising, but Germany, as a united country, entered the international scene only in January 1871. Wilhelm I of Prussia was crowned emperor Wilhelm I of Germany after the victorious war with France, waged by a coalition of German states under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia. (To humiliate France further, the coronation took place in Versailles.) Despite this, the architect of the German unification, Otto von Bismarck, was not a staunch supporter of war as a successful instrument in resolving international disputes.

Though German unification is believed

to be Bismarck’s crowning achievement, he also managed to isolate France, preventing it from forming dangerous alliances, and maintaining good relations with Britain, notably after 1882, when the British occupation of Egypt was met with outrage from France. During the Berlin Conference two years later, Germany was given some colonial territory in Africa. However, in 1888 a new figure ascended the German Imperial throne – Wilhelm II, grandson of Wilhelm I. A nationalist, militarist, and imperialist, he was, from the start, bent on giving Germany its “rightful place in the sun”. He sacked Bismarck and appointed Alfred von Tirpitz the Secretary of the Navy. Even though after the victorious war against France Germany had the biggest army in Europe, its navy was significantly smaller and not fit for a country aspiring to be seen as an empire. Tirpitz devised a plan to change that and challenge Britain’s dominion over the world’s oceans.

Since the very beginning of the 18th century, the British navy has been the greatest in the world. In time, the British government even invented the "two-power standard" policy, according to which Britain should have more ships than the second two greatest naval powers combined. The royal navy was the essential building block of the Empire, enabling Great Britain to control a quarter of the globe’s landmass. Britain was not keen on losing its position to the newly created German Empire and thus, started to look closely at Germany’s actions.

Tirpitz’s plan was not to beat the British in the number of ships. The British fleet was dispersed worldwide to maintain the Empire, while Germany could concentrate only on the North Sea. The idea was to make Britain fear defeat at German hands in this region, as the mere possibility would mean that its position elsewhere in the world was threatened, too.

27

Between 1898 and 1912, Germany passed several Naval Acts to increase the build-up of ships. Their aggressive policy was not discouraged by the construction of HMS Dreadnought. This British next-generation battleship was significantly faster and had more firepower than any battleship possessed by any country at that time. In 1906, HMS Dreadnought effectively rendered the entire German fleet obsolete. Despite this, two years later Germany ordered six dreadnoughts, while Britain planned to add only four to the one already afloat.

Driven by the need to maintain their naval supremacy (a policy very much supported by the British public), the British government in the person of Winston Churchill – the first lord of Admiralty at that time – announced the “two to one” program. Britain was simply to build two dreadnoughts for every dreadnought constructed by the German Empire. Tirpitz’s idea of forcing the British Empire to concessions to Germany in colonial matters backfired, dragging Germany’s economy, already heavily burdened with sustaining the most significant army in Europe, into an even more expensive naval arms race. Even worse for the German economy was the fact that the new German fleet was mainly to be used as a scarecrow against Britain rather than

a force to make Germany’s trade with its colonies more prosperous. Good relations with Britain, maintained since Bismarck had supported the British occupation of Egypt, came to an abrupt end. Britain, to the detriment of Germany, decided to strengthen its relations with France by signing the Entente Cordiale alliance in 1904 – an agreement that laid the foundation for the future coalition during the Great War.

Due to the rising threat posed by Russia, which had signed a military agreement with France, effectively rendering the German Empire surrounded by potential enemies, the German ruling class realized that one could have either the most outstanding army or navy in Europe, but not both. In 1912, Germany withdrew from the naval arms race after an unsuccessful attempt to create an alliance with Britain. Eventually, the British “two-power standard” was upheld, and in 1914 Britain had a total of 29 dreadnoughts, while the combined navies of France and Germany had among themselves 27 dreadnoughts. During World War I, the German battleship fleet posed no challenge to the combined strength of Britain and France. Ironically, the German plan to contest Britain’s domination on seas contributed to the downfall of the German Empire.

28

The Lament of the Reeds

Acorus Calamus, better known as sweet flag or muskrat root, is a species of water reed found com monly throughout North Ameri can wetlands. Although histori cally it was valued for its medical properties, today it is nothing more than an ordinary weed. And yet so mehow, this inconspicuous plant, with its long saber-like leaves, has made its mark on literary history.

In 1860 Walt Whitman, one of the greatest Ame rican poets, pu blished a sequence of poems entitled Calamus, now fa mous for its brave affirmation of ho mosexual love. There is no consen sus among scholars on why Whitman chose the name of a water reed for this particular sequ ence; however, the most popular theory traces the word Calamus to its ancient Greek origins, Kalamos (Κάλαμος, “reed”), and the myth from which it derives.

Kalamos and Karpos were two young boys in love. One day, as they were having a swimming con test in the Maeander River, Karpos drowned. In despair, incapable of living without his beloved, Kala

Konrad Zaręba

Konrad Zaręba

mos committed suicide by drow ning himself in the same river. He was then transformed by gods into reeds growing on the banks, whose rustling in the wind is an immor talized lament of a boy who lost his lover.

Another ancient story which is curiously similar to the myth of Kalamos and Karpos is the story of Roman emperor Hadrian and his lover Antinous. During one of their many travels thro ugh the Roman Em pire, while they were going up the Nile, Antinous fell into the river and drowned. Heartbroken, Had rian wanted to com memorate his belo ved and ordered the city to be built at the place of his death. He began the process of deification, intent on including Antinous into the pantheon of Roman gods. He also chose the blue lotus (Nymphea nouchali), a water plant growing all over the banks of the Nile, as a symbol of his deified lover, who se divine beauty was henceforth immortalized by a delicate flower native to the river that claimed his life.

The similarities between the

29

myth of Kalamos and the story of Antinous are striking; a lover drowned in the river, great sor row, and a water plant that beco mes the symbol of undying love. The water imagery prevalent throughout both stories is equ ally prominent in Whitman’s Calamus. There are pond-wa ters, beaches of the sea, shining and flowing waters, cool waters, the living sea, the bayous of the Mississippi, and many more. The connection between Whit man’s “manly love of comrades” and his reverence for all the wa ters of the world echoes the sto ries of those tender lovers who, by a twist of fate, became one with the river.

Whitman’s poems resem ble those stories frozen in the moment of absolute pleasure that preceded the tragedy, and maybe that is precisely what they are. Appreciation of love and desire of a man lying na ked somewhere along the ri ver, who gazes at the currents, completely content in the mo ment. But contrary to his an cient predecessors, he is fully aware of the imminent tragedy. In Whitman’s case, it is not the death of the loved one but the realisation of the painful reali ty of the homophobic society in which he lives. And yet, he so mehow always seems unbothe red, entirely at peace with him

self and the world around him. For him, sexuality is as fluid as a flowing river, and emotions are as wayward as a roaring sea. He perceives love and comrade ry as a life force akin to water without which everything wo uld perish. Maybe that is why he chooses Calamus to be “the token of comrades” but only for, as he puts it, “them that love as I myself am capable of loving”. In one moment, a common wa ter reed becomes the sacred symbol of homosexuality, and Whitman becomes a wise sage who opens the eyes of his re aders to a simple yet often over looked idea. Time itself is like a river, and every single person becomes a part of the current at some point. Our experiences ripple through time like a sto ne thrown into the water, beco ming a small part of the larger picture. Past events echo one another, constantly influencing the future, and it is up to us to find strength in this endless cycle of experiences just like Whitman found it.

One question then arises. Is the poetry of Walt Whitman an echo of the story of ancient lovers, or can we hear the story of Whitman echoed in the ru stling of the reeds among voices of Kalamos, Karpos, Hadrian, Antinous, and all those who da red to love differently?

30

Come Hell or High Water

Sara Bonk

On 13 June, 2022, southwestern Montana was hit with a historic flood that left swaths of the area devastated. This was a complete turnaround from the previous year when the same area was partially evacuated due to a devastating wildfire season that threate ned to consume everything in its path. One of the towns affected by this turn of events was the gateway town of Red Lodge. Abo ut one hour north of Yellowstone National Park, Red Lodge relies heavily on tourism to survive the months until the local ski hill opens, or until the next summer comes when to urists flock to the small town once again. For the flood to have oc curred so early into the tourist season, it left the town’s already fragile po st-COVID-19 econo my devastated. Residents who live in the areas hammered by the flood recall being awoken before dawn in order to evacu ate, with some having to fight their way out of alrea dy heavily flooded homes. By the early afternoon, whole houses were either completely flooded or even washed away by the normally docile creek. The aftermath of the flood was so severe that the governor of Montana, Greg Gianforte, declared a sta te of emergency, with President Joe Biden promising FEMA funds to the damaged are as. Red Lodge was not the only area to be affected though, as other gateway towns of Yellowstone, such as Gardiner, Cooke City, and other nearby towns, was either left com

pletely isolated due to washed out roads, or had to be airlifted out to safety. Yellowstone National Park was also shut down for a week due to the flood originating from within the borders of the iconic park. Sadly, townspeople were not the only ones that were distressed. Due to the unpredicta ble nature of the flood, many campers in the nearby sites were also trapped in the mo untains after whole roads and bridges were washed away. In order to bring these people to safety, the Montana Forest Servi ce called in extra help through the National Guard with even the Army coming to town to help. Once the floodwaters went down, and the displaced residents were able to get back into their ho uses, activists took to the streets in order to help those in need. Hundreds of volunteers from as far as the nearest city of Billings (about an hour away down in The Valley) flooded Red Lodge lug ging buckets, tool kits, or just sim ply offering to help with any kind of manu al labour. Basements that were previously submerged to the ceiling with muddy water were now being cleared out in a matter of ho urs. It would not be possible if it were not for the people who helped lug bucket after buc ket of mud and sand, all the while hauling out ruined furniture and destroyed walls. Others simply offered food, water, and even rooms for those who were displaced and had nowhere else to stay. This show of solidari

31

ty within the town’s com munity brought up the well-known phrase of “come hell or high water”, and perfectly encapsulates the year that Red Lodge residents had to handle. Today, many homes are still enduring the renovation process or being comple tely rebuilt. Roads are slowly but surely being restored, and the town continues to ensure that it is open and ready to take in the last stragglers of the tourist season. Even though it might take years for Red Lodge to completely recover, the town re mains optimistic, believing that the hell and the water have passed for good.

32

Dry Summer: This is how we go out

Samet Eray Karakaş

Metin Erksan’s Dry Summer (1963) is one of the few Turkish movies that achieved international success. It is also one of the first movies that revolves around water shortages, a problem humanity is likely to expe rience even more in the future. I be lieve Dry Summer gives an insight into the times when oil wars are en tirely replaced by wars for water.

The movie is set in the village of İzmir, Turkey. Knowing that the summer will be rather dry, Osman (Erol Taş) decides to hoard water on his lands – he builds a barrier in the canal to prevent water from flo wing into other farmers’ lands. Un fortunately, the only water source used for irrigation springs from his territory. Without it, other farmers would not have a chance to work the land. They desperately appeal to law, but it turns out to be a futile attempt;

the property and all it comprises be longs to Osman.

The situation is further compli cated by Osman’s obsessive interest in his brother Hasan’s (Ulvi Doğan) beloved wife, Bahar (Hülya Koçyiğit). Blinded by greed, Osman wants the water and Bahar for himself. To this end, there is nothing he would not do, which makes him a truly me morable villain. Another reason for Osman’s unforgettable wickedness is Erol Taş’s brilliant acting; it is not surprising that he is renowned as one of the most well-known “bad guys” of Turkish cinema.

The imagery of the film constan tly emphasises the title of the mo vie, as most of the scenes conjure up extreme temperatures. In one such scene, the farmers, after Osman cuts off the water supply, try to cultivate their lands among blazing VVVfires.

What is striking about this scene is its infer nal visuals; the farmers look like tormented souls in hell. This atmosphere, which would be easier created through the use of vivid co lours, is presented in black and whi te with such a skill that one can see the intensity of the fi res and almost feel the heat. It comes as no surprise that Dry Summer won the Golden Bear award at the 14th Berlin Internatio nal Film Festival in 1964.

Dry Summer is definitely worth watching because it is so relevant in today’s world. The way in which farmers resort to violence when the re is no water supply to cultivate their lands

is terrifying; given that there is a finite amo unt of water in the world, similar catastro phic incidents may arise in the future. Only then can we all empathise with Osman. After all, one of the reasons why he stops sha ring his reserves is that he thinks the summer will be exceptionally dry; in other words, he has to save himself first. This motiva tion of Osman con fronts partnership with the urge to survive amid scar ce water resources. Considering clima te change and glo bal population gro wth, the issues Dry Summer explores may foreshadow the downfall of humanity.

Was the alliance between Australia and the United States inevitable?

Marek Kobryń

Marek Kobryń

On the 15th of September 2021, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States announced the creation of AUKUS: a new alliance of these powers in the Indo-Pacific region. This event caused international tur moil because of one of the coalition’s points – the Australian purchase of U.S. submari nes, which meant breaking the contract for the sale of 12 submarines signed with France back in 2016.

From the European point of view, the alliance between Australia and the United States is hardly sing and should not be the for breaking a contract one NATO member in favor of another. But from the perspective of Austra lia’s foreign policy history, forming AUKUS was its most crucial decision in this field since the end of World War II, and one that has already spar ked a reaction from the People’s Republic of China (PCR). This su mmer, China announced a new agreement with the Solomon Is lands, according to which the So lomons allowed China to build a military base on its territory. The signing of the agreement raised concerns in Australia, with the Solomon Islands be ing situated around 2,000 ki lometers (not all that far on the Pacific scale) from the Au stralian coast. Some politicians from the Land Down Under have put forward similar ar guments concerning this new alliance to those presented by Russia before the outbreak

of the war in Ukraine, namely that China is threatening Australian national security by creating a close alliance with the country in the immediate vicinity of Australia.

The situation wasn’t always so grim. In the 90s, Prime Minister Paul Keating wanted Australia to become an Asian country focu sing its energies on both its immediate ne ighborhood and the Indo-Pacific region on the whole. Since its opening to the interna tional market, Australia has been very keen on doing business with China, which is the source of a certain paradox in Australian foreign policy. On principle, China is not opposed to doing business with Australia –mainly because, contrary to the United States, the PRC is not blessed with rich deposits of energy resources. For the last thirty years, it has been importing Australian gas and coal in large quantities, building a solid fo undation for good relations be tween the two countries. In the early 2000s Australia even an nounced a partial withdra wal from the QUAD alliance with the United States, India, and Japan. Currently, about a million citizens of Chine se descent live in Australia, and Chinese students have been welcomed into Australian uni versities with open arms for se veral years. Everything was po inting toward the loosening of the relationship between the U.S. and Australia.

So what convinced Austra lia to restrengthen its rela tions with the U.S. instead of China? Severe problems oc curred in the relations be

35

tween China and Australia during the out break of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. Both countries accused each other of unfair bu siness practices and breaking pandemic re strictions. Tariffs imposed by China on Au stralian products were an additional nail in the coffin, causing the Australian Treasury to lose billions of dollars.

In his speech announcing the creation of AUKUS, Scott Morrison invoked common values between Australia, the United King dom, and the United States. Common valu es they might have, but another reason for Australia to sign up for the alliance was to protect its trade routes. Here comes the afo rementioned paradox: despite the deterio ration of their relations, China remains the most considerable Australian trade partner, so Australia’s deal with the U.S., and against China, is meant to protect its trade routes with the PCR.

But why is forming AUKUS seen as chal lenging China’s position in the region? It is, after all, not a military alliance like NATO, whose primary purpose was to thwart the position of the second superpower in the world at that time. The devil, as always, is in the details. The AUKUS agreement specifies

that Australia will buy 12 American subma rines with atomic drive and the technology to construct them, which will take place in Australia rather than in the U.S. This means that Australia will have the capability of ven turing into Chinese waters unopposed, both due to the atomic drive technology, enabling the submarines to be submerged indefini tely, and China’s poor submarine detection technology, leaving much to be desired in comparison to the American equivalent. These circumstances make the situation particularly humiliating for France, which built the submarines ordered by Australia based on a submarine with atomic drive spe cially altered for conventional diesel-electric drive according to Australian specifications. Neither Australia, the U.S., nor the United Kingdom tried to notify France in advance about the submarine contract’s cancella tion. The truth is that France no longer has a position comparable to the U.S. in the In do-Pacific region. This does not mean, howe ver, that it should be treated with disregard. Especially with China striking back, Austra lia and the U.S. will soon need all the help they can get.

36

37 Next in Second Thoughts: The Shift Send your text till 30th Nov 2022!

Natallia Valadzko

Natallia Valadzko

Konrad Zaręba

Konrad Zaręba

Marek Kobryń

Marek Kobryń