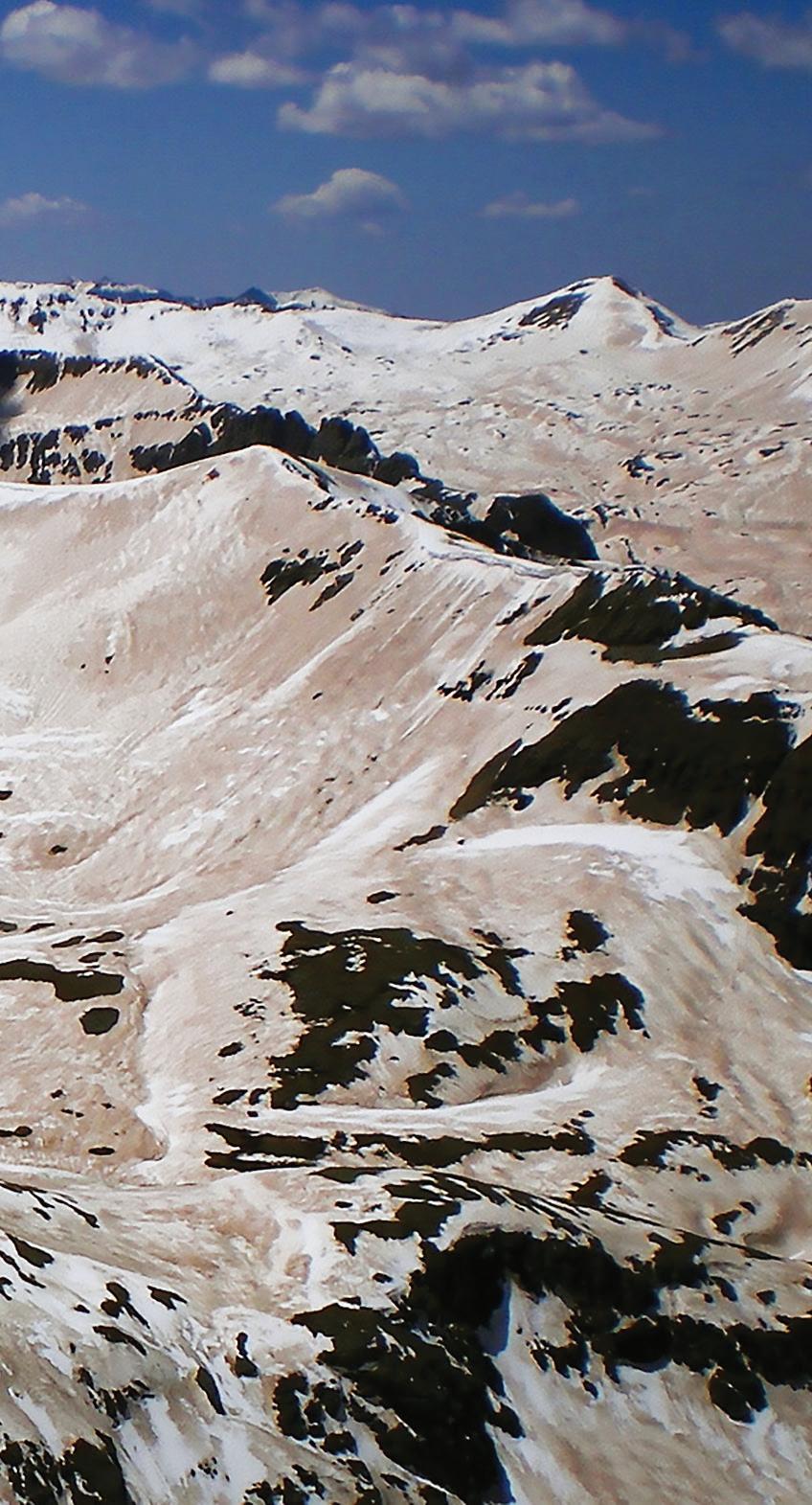

THE SNOW ISSUE

How The Powder On Colorado's Peaks Affects Water Decisions Downstream

Each year, all eyes fall on Colorado’s snowpack, the state’s largest “reservoir,” as irrigators, boaters, utility managers, and others wonder how that snow will translate into summer streamflows. As the climate has become more variable, the amount of snow that falls and the accuracy of such forecasts are more critical than ever, leading to a renaissance in new data, modeling, and research, and a surge in cloud seeding. These hands-on efforts should help Coloradans really know their snow!

After a healthy season of snowfall in the mountains, researchers are working to figure out what's happening to the disappearing runoff.

Scientists and water managers are gaining new insights into the factors influencing snow accumulation, and also finding better ways to measure it. The aim is improved runoff forecasting and ultimately better, more precise water management.

BY KELLY BASTONERunoff forecasts don’t always match reality, and big snow years can yield low streamflows. What’s causing the gap between deep winter snows and low summer flows? (Hint! Many factors are at play, but weather is key.)

BY ALLEN BESTColoradans and downstream states take matters into their own hands with cloud seeding, a weather modification effort to boost snowfall.

BY ELIZABETH MILLERWater news from across Colorado: Beyond Powder

As Colorado ski resorts gear up for a warmer future with more snowmaking, Eldora hopes to expand reservoir storage. Getting Clarity

The Colorado health department offers nearly $86 million to help small and disadvantaged Colorado communities remove PFAS from their drinking water. Around The State Quick updates from Colorado's major watersheds.

Celebrate the impact of WEco’s members.

As this magazine hits the printer, I will be traveling with our Programs Director, Sabrina Scherma, from Leadville to Pueblo Reservoir, and various sites in between, to scout for WEco’s 2024 River Basin Tour.

This year we’re featuring the Upper Arkansas River Basin, including its history, natural and built infrastructure, water management challenges, current and future priorities and projects, and more.

This will be the seventh river basin tour I’ve had a hand in planning for WEco. We use the scouting trip to visit each of our tour stops and meet with the people who will be our hosts. We check the quality of the roads, confirm that the timing for our draft itinerary works, and evaluate how far people will have to walk—and over what kind of terrain. We consider the narrative and how the story of one site connects to the next.

This is our method for fine tuning so that, come June, our tour participants have an incredible learning experience. If you haven’t been on one of our tours before, consider joining us June 4-5. Registration is currently open on our website.

Getting out into the field for these scouting trips, and, eventually, the tour itself, has afforded me the opportunity to see vast swaths of Colorado’s diverse landscape and to meet incredible people. I return recharged and invigorated about the state we live in, the resources we’re working to protect, and the collaborative projects underway—all of which we weave together in the information and programming we reflect back out into the community. It’s rewarding work.

To celebrate that work, and to recognize the members, donors, volunteers, and board and staff members who make it possible, we just released our 2022-2023 annual report. (Find it online at wateredco.org/reports). The report highlights WEco’s impact, sharing the many ways we are putting our mission into motion to achieve the vision of a vibrant, sustainable and water-aware Colorado. Read about everything from Water Leaders to the Water Educator Network, the Water ’22 campaign, news and publications, and more.

Planning tours and producing annual reports isn’t all we’ve been up to. We concluded our 2024 legislative session outreach with two 201-level water workshops at the Capitol in March and April. And now we’re pulling together a similar educational session geared toward county commissioners at the Colorado Counties, Inc., conference in late May.

In addition to our regular programs, WEco does a lot of work that our usual audiences don’t necessarily see. In the past month, we’ve helped to inform new educational displays going up at CSU Spur’s Hydro building, met with staff from the German Embassy seeking to understand water in the West, and participated in the inaugural Water Workforce Summit convened by the Colorado Water Center.

As water grows increasingly scarce and pressured, it’s becoming top of mind for more Coloradans, whether policy makers, educators, students, or business leaders. WEco’s work is in demand, and we’re counting on your sustained support and participation!

STAFF

Jayla Poppleton

Executive Director

Sabrina Scherma

Programs Director

John Carpenter Operations Manager

Tess Koskovich

Marketing, Communications and Outreach Manager

Suzy Hiskey

Administrative and Programs Assistant

Jerd Smith

Fresh Water News Editor

Caitlin Coleman Publications and Digital Resources Managing Editor

Dana Smith

Headwaters Art Director

Lisa Darling President

Dulcinea Hanuschak

Vice President

Brian Werner

Secretary

Alan Matlosz

Treasurer

Cary Baird

Perry Cabot

Nick Colglazier

Nathan Fey

David Graf

Eric Hecox

Matt Heimerich

Julie Kallenberger

David LaFrance

Dan Luecke

Karen McCormick

Leann Noga

Peter Ortego

Dylan Roberts

Monika Rock

Kelly Romero-Heaney

Ana Ruiz

Elizabeth Schoder

Don Shawcroft

Chris Treese

Katie Weeman

THE MISSION of Water Education Colorado is to ensure Coloradans are informed on water issues and equipped to make decisions that guide our state to a sustainable water future. WEco is a non-advocacy organization committed to providing educational opportunities that consider diverse perspectives and facilitate dialogue in order to advance the conversation about water.

HEADWATERS magazine is published three times each year by Water Education Colorado. Its goals are to raise awareness of current water issues, and to provide opportunities for engagement and further learning.

THANK YOU to all who assisted in the development of this issue. Headwaters’ reputation for balance and accuracy in reporting is achieved through rigorous consultation with experts and an extensive peer review process, helping to make it Colorado’s leading publication on water.

© Copyright 2024 by the Colorado Foundation for Water Education DBA Water Education Colorado. ISSN: 1546-0584

CSU Spur, Hydro/The Shop, 4777 National Western Drive, Denver, CO 80216 (303) 377-4433

We're excited to announce that WEco's Annual River Basin Tour will feature the Upper Arkansas River Basin in 2024! We'll be spending two days in the field, seeing an exciting mix of natural features and infrastructure projects between Leadville and Pueblo, ranging from transmountain diversions to hydropower facilities, a fish hatchery, a fen research site, a whitewater park, wildfire mitigation work, and much more. Join 55 other participants, from lawmakers, to water managers, attorneys, engineers and members of the public, to learn about the history, water management practices, and challenges of this river basin. Registration opened in early April. Don’t wait to reserve your spot on the bus. We hope to see you on the tour! Visit wateredco.org/tours to register.

Water Education Colorado welcomed Tess Koskovich as our new and first-ever Marketing, Communications, and Outreach Manager in January. Tess grew up in Sedalia, Colorado, and comes to us from the University of Denver (DU), where she has held a variety of roles over the past five years ranging from HR to Operations, and where she received her master's degree earlier last year in Communication

Management. Most recently she worked as the manager of customer experience in the DU financial division. In addition to her master's degree, Tess earned a bachelor's degree in Communication and Event Planning from Metropolitan State University. Outside of work, you'll find Tess enjoying everything "Colorado" –skiing, hiking, camping, and sharing cooking adventures with her husband.

From Forecast To Flow: KNOW YOUR SNOW WEBINAR RECORDING AVAILABLE

Each year, mid-April is about when snowpack peaks for the Rocky Mountains. But what will that mean for the rivers come May, June and July? And why have recent forecasts consistently overestimated the snow-to-flow connection? During a webinar on April 11, WEco and the Colorado River District partnered to explore these questions and to bring this snow-focused Spring 2024 issue of Headwaters magazine to life. Watch the recording at wateredco.org/webinars.

We enjoy the snow, it’s there to play in but it’s also a part of a commitment to other people … and critical to agriculture to be efficient and able to continue.

We spoke with Don, a member of the WEco Board of Trustees and a rancher in the San Luis Valley, about snowpack, snowmelt and runoff, how ranchers plan for it, and what Coloradans should consider when trying to understand what happens downstream. Read more on the blog at watereducationcolorado.org.

Few things are as exciting as waking up to a fresh snowfall, then perhaps venturing outside in the quiet where the snow dampens other sounds and more weatheraverse people are still huddling indoors. I hope that our young son, Ronan, will experience the same snow magic as he gets older.

But in reporting on this issue of Headwaters magazine, I imagine the many water users who look at snowpack and streamflow data and forecasts daily to inform operational decisions experience a more extreme emotional rollercoaster. They, along with many of our readers, must feel next-level exhilaration in big snow years,

and, conversely, deep concern during belownormal years or when high snow readings unexpectedly result in low river flows. Read about the factors that can contribute to a mismatch between snow measurements and streamflow in “The Mystery of Disappearing Snowpack,” page 22.

There’s a lot riding on the accuracy of snow forecasts—important decisions such as how much water to store in a reservoir or release downstream and which crops to plant. Coloradans have long recognized this, collecting critical data using SNOTEL stations since the 1930s. Patty Rettig with the Water Resources Archive at Colorado State University recently shared some documentation backing up our long history with snow. In an April 16, 1945 meeting of the Colorado River Water Forecast Committee, Ralph Parshall, who served as chairman at the time, said the following:

"I am not sure that all of us actually recognize and appreciate what the snow means to the prosperity of our Western country. We can well imagine that if the Colorado River were to cease flowing it would not be difficult to realize the seriousness of such a situation. Much then depends upon the mountain snow cover … for the prosperity of the West, these problems concern our Committee." (Keep

advanced. The need for water—and snow— has led to weather modification efforts, in which water providers, with the help of funding available through Colorado and other downstream states in the Colorado River Basin, give clouds a little help, spurring them to release snow. Read more about cloud seeding in “Let It Snow,” page 28.

At the same time, the decisions riding on snow data and forecasting are driving research and new forecasting models. But for actionable decisions, water managers still rely on a small selection of standard tools— think SNOTEL data, streamflow projections like those from the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center, plus some newer methods such as Airborne Snow Observatories, Inc. (ASO) flights. Learn about the research, the evolving snow measurement tools available, and how they are used in “Understanding Snow,” page 13.

In another 80 years, snow may be more scarce and less predictable, but I can’t imagine that it will be any less valuable. Will today’s research and innovation lead to big advancements in understanding

You may begin to notice some subtle design changes in Headwaters magazine. That’s because we’re working with a wonderful new art director, Dana Smith. She brings more than 20 years of experience in design and art direction to Headwaters, having worked on publications such as 5280, 5280 Home, Outside magazine, and others. We were drawn to her creative, clean and modern design and her sweet personality. We’re looking forward to seeing Dana push Headwaters and our other publications to new heights. Welcome Dana!

This is a remembrance of Chas Chamberlin. I suspect you did not know him.

I also suspect he would not be on board with Water Education Colorado and Fresh Water News honoring him in this way. But that would have been just another of the spirited arguments we had over some 20 years of working together.

He died suddenly the day after Christmas last year, leaving a huge hole in the lives of his beautiful wife and three grown children as well as his three grandchildren, his many friends, and his colleagues here at WEco and Fresh Water News.

For nearly a decade, he was the visual force behind Headwaters magazine, Fresh Water News, and WEco’s Citizen’s Guide (now Community Guide) series. The graphics and maps WEco and Fresh Water News have become known for were of his creation, as were the gorgeous front covers and pages that made up the magazine and guides.

He was an artist and an early adopter of digital art, creating electronic imagery that is common now, but that was little known more than 20 years ago.

It was in the news arena, however, that he made his living. He came to the Rocky

Mountain News after stints helping shape the images of such other papers as the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Detroit Free Press.

He could work for hours and hours on end, a habit he said he picked up peeling potatoes on a U.S. Navy ship. Throw any new piece of design, mapping or graphic software into his lap and he would have it mastered within minutes, or so it seemed.

Toss out an idea, and almost as quickly, it was transformed into an elegant graphic or map that, when added to a water story, made it easy for anyone to grasp.

In 2002, as a catastrophic drought gripped the state, I began covering water at the Rocky Mountain News. Chas had recently started

working there. I was out on the White River in Rio Blanco County reporting on a group of ranchers who had volunteered to give up their right to divert water temporarily so that Colorado Parks and Wildlife could pass some of its stored water down past the ranchers’ diversion points, helping stop a looming fish die-off. The effort succeeded only because the ranchers generously agreed to participate. From the field, I called my editors and said, “I need a map of this irrigation system, but I don’t know if we can get the data and get something designed in time to meet deadline.” I should not have been concerned. When I drove back to Denver a day later, the irrigation system, precisely located, drawn and properly labeled, showed up on a map that we published with the story, giving thousands of readers the ability not just to read a narrative, but to better understand the on-the-ground context and logistical intricacies of what the ranchers and the state were doing to save the fish.

It was classic Chas Chamberlin. He set a high bar for hard work, creativity and excellence. And he did so with thoughtfulness, kindness, and good humor. It was a true honor and privilege to have worked with him. He will be deeply missed.

Jerd Smith, Fresh Water News Editor

How one Colorado ski resort is prepping for a changing climateBY SHANNON MULLANE

Eldora Mountain Ski Resort is eyeing new water storage sites in Boulder and Gilpin counties as it plans for more ski runs and a drier future.

Eldora isn’t the only ski resort in Colorado that’s in need of more water to make snow, and to operate toilets, water fountains and restaurant kitchens. Ski resorts make up a tiny slice of Colorado’s overall water use, but they’ll likely need to boost their supply by about 41% by 2050, according to state estimates.

“We know that climate change is real, and we’ve got to anticipate having some lowweather years where we need more water storage just to stay in business,” said Brent Tregaskis, the resort’s general manager. “That’s a big part of my motivation, is to be prepared for the future.”

In December, Eldora started the vetting process in water court for its hoped-for storage expansion—a proposal to turn three natural depressions into storage ponds and expand three existing reservoirs. If water court approves, the resort could access up to 197 acre-feet of additional storage for a total of around 517 acre-feet, according to Eldora. The new water rights would be very junior, with a priority date of 2023 or 2024.

In response, some concerned citizens and nearby communities are watching Eldora’s proposal closely. The environmental group Save The World’s Rivers called for more transparency and community engagement to ensure that the area’s watershed is protected.

The Water Users Association of District No. 6—which comprises the majority of senior water rights holders in the Boulder Creek basin, like Boulder County, Lafayette and large agricultural diverters—primarily wants to make sure no downstream diverters

are adversely impacted. And residents in the nearby town of Nederland have raised questions about environmental impacts, said Miranda Fisher, town and zoning administrator for Nederland.

“We’re all sourcing from the same stream, and so it’s really important that we understand what they’re doing, and of course when the time comes, that they understand what we’re doing,” Fisher says.

Eldora Mountain Resort, located 21 miles west of Boulder, offers 680 acres of terrain. The resort wants more water primarily to make more snow. Snowmaking— which typically involves pumping water from ponds through machines that spew out snow onto the slopes—has been vital for resorts since the 1980s as a way to guarantee good runs even when snow storms are few and far between.

Throughout Colorado, resorts collectively used about 5,620 acre-feet of water per year to make snow as of 2015, according to the Colorado Water Conservation Board. By 2050, that use

is expected to increase to 7,950 acrefeet per year.

Cities, towns and industries like the ski industry will also face water shortages by 2050. Statewide, the gap could be up to 740,000 acre-feet in dry years, according to the 2023 Colorado Water Plan.

For snowmaking, resorts need dependable water supplies in dry years — and for that water to be usable in the winter, resorts need storage.

“The name of the game was storage. That’s the bottom line,” said Glenn Porzak, a water lawyer who has worked with resorts for more than 30 years to corral water rights and develop storage.

This story originally appeared in The Colorado Sun, a partner to Water Education Colorado in publishing Fresh Water News to cover water stories of critical importance to Colorado and the West.

Shannon Mullane writes about the Colorado River Basin and Western water issues for The Colorado Sun.

For snowmaking, resorts need dependable water supplies in dry years—and for that water to be usable in the winter, resorts need storage.

Colorado communities are finding funds to get rid of “forever chemicals” in their drinking waterBY JERD SMITH

Nearly $86 million in federal funding to help Colorado communities with the daunting task of removing so-called “forever chemicals” from their drinking water systems has begun flowing this spring, but whether it will go far enough to do all the cleanup work remains unclear.

Small Colorado communities are scrambling to find ways to remove the toxic PFAS compounds that wash into water from such things as Teflon, firefighting foam, and waterproof cosmetics.

Thanks to the infusion of federal money this year, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment is offering grants to help with cleanup costs. But word of the Emerging Contaminants in Small and Disadvantaged Communities Grant Program, as it is known, has been slow to spread, Colorado public health officials said. That’s, in part, because the problem is still being understood and remedies are still being studied.

“Emerging contaminant funding is relatively new. Many communities are still determining if they have a project they may need to request funding for,” state health department spokesman John Michael said in an email.

Just four communities had applied as of late March 2024: South Adams Water and Sanitation District in Commerce City; City of La Junta; Louviers Water and Sanitation District in Douglas County; and Wigwam Mutual Water Company in Fountain.

Each year for the next five years, the state will offer two rounds of grants, with millions of dollars committed. The next grant cycle opens in July, according to Michael.

And on April 10, 2024, the EPA finalized the first PFAS drinking water treatment

standard, which requires utilities to remove certain chemicals at levels above 4 parts per trillion. Prior to this, federal oversight of the contaminants was advisory, meaning utilities were not technically required to remove them. The advisory rule was set at 70 parts per trillion.

Still, many water providers have been testing and monitoring for the compounds for several years. But for small communities lacking such resources, the costs and stakes are high.

The South Adams County Water and Sanitation District, which serves Commerce City and unincorporated parts of Adams County, has been hard-hit by PFAS contamination in its groundwater wells.

Where the toxins have come from isn’t entirely known, but sources could include firefighting foam used nearby at a firefighting academy owned by the City of Denver.

When PFAS was first detected in 2018, the Adams County district shut down its most contaminated wells, built an expensive filtration system, and bought water from Denver Water to dilute its water sources enough so that PFAS could no longer be detected.

It also built a cutting-edge testing lab, so that it can know within 24 hours whether its extensive treatment system is working and respond immediately if it is not.

But that isn’t enough. This year it will begin building a new $80 million treatment

In April, the EPA finalized the first PFAS drinking water treatment standard, which requires utilities to remove certain chemicals at levels above 4 parts per trillion.

plant, $30 million of which will come from the new state grant program. It has also been approved for a special $30 million loan from the Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority. It is still pursuing additional funding to minimize the amount it will have to seek from its customers to help cover the costs, according to Abel Moreno, the district’s manager.

“It’s absolutely critical that we find another source of funding,” Moreno says. “We don’t believe the contamination was caused by our ratepayers, and we do not believe they should be asked to pay for it.”

This story originally appeared in Fresh Water News, an initiative of Water Education Colorado currently being published in collaboration with The Colorado Sun. Read Fresh Water News online at watereducationcolorado.org.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News.

Public opposition is flaring around a silver and gold milling project near Leadville. CJK Milling Company purchased the old Leadville Mill and has applied to the Colorado Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety to permit a new venture in which the company hopes to use chemicals to extract bits of gold and silver from old tailings and slag piles around Leadville. Some residents have organized into a group called Concerned Citizens For Lake County (CC4LC) and are opposing the proposal. CC4LC says it is concerned about the use of toxic cyanide at the mill, which is located in a drainage that flows to the Arkansas River.

Fresh Water News reports that the Colorado River District, together with a group of West Slope governments and water providers, aims to raise $98.5 million to purchase and protect water rights associated with the Shoshone Hydropower Plant in Glenwood Canyon. Shoshone’s water rights, currently owned by Xcel Energy, are some of the oldest and largest rights on the mainstem of the Colorado River in Colorado. The river district, with the aim of ensuring water security into the future, signed an agreement in December 2023 to purchase the water rights and lease them back to Xcel. Per the agreement, the river district now must assemble funding and complete legal steps to buy the water by the end of 2027.

Crested Butte News reports that planned new developments around Crested Butte could overly stress wastewater infrastructure. A memo from the Mt. Crested Butte Water and Sanitation District and consultant HDR flagged that the main sewer line through Crested Butte is near

maximum capacity and, at certain times of the year, will be unable to support any new large developments. Infrastructure will need to be replaced before additional development should be approved, the memo says. The developers say they are willing to work with the district to resolve the issue.

One small reservoir, Mexican Reservoir, will be enlarged this summer, thanks to a Colorado Water Conservation Board Water Supply Reserve Fund Grant for $265,000, approved during the CWCB board meeting on March 13. Spicer Ranches owns Mexican Reservoir, which it will enlarge to hold an additional 200 acre-feet of water, enough to irrigate 70 more acres of forage on top of the 65 acres that the ranch currently irrigates. The project should be complete by October 31. “One of the [North Platte Basin Roundtable’s] Basin Implementation Plan imperatives is to increase storage in the basin and this goes toward that in a small way,” said CWCB board member Barbara Vasquez during the March meeting.

Fresh Water News reports that a handful of growers in the San Luis Valley are preserving their lands and protecting sandhill crane food sources through conservation easements with Colorado Open Lands’ Gain for Cranes program. The program ties water rights to conserved land, protecting the farms and the birds’ habitat. The birds, which once depended wholly on wetlands, aren’t considered threatened, but water issues in the valley and changes in crops are putting pressure on their habitat.

Fresh Water News reports that Colorado lawmakers approved a resolution in

March, asking Congress to fund repairs to the deteriorating Pine River Indian Irrigation Project in southwestern Colorado. The federal water system is decades behind on maintenance, putting water delivery at risk for farmers and ranchers on the Southern Ute Reservation and in La Plata County.

Fresh Water News reports that Nebraska is moving quickly to build a major canal, known as the Perkins County Canal, that will take water from the South Platte River and deliver it to new storage reservoirs in western Nebraska. With $628 million in cash from its state legislature, Nebraska has begun early design work and is holding public meetings outlining potential routes for the canal and reservoirs. Nebraska intends to complete design and start construction bidding in three years and finish the project seven to nine years later. Colorado water regulators say they will carefully monitor the project and plan to meet regularly with Nebraska’s team.

A new funding mechanism called the Yampa Ripple Effect allows more widespread business support of the Yampa River. The Ripple Effect aims to empower shoppers at local businesses to “round up” to the next dollar and make a small donation toward the Yampa River Fund, supporting projects that enhance river flows, infrastructure, restoration, education efforts and more. While the Yampa Ripple Effect is new, a handful of local businesses are already participating.

Caitlin Coleman

CAN WE BETTER PREDICT THE BEHAVIOR OF SPRING SNOWMELT?

With winter snowpack ranking as Colorado’s largest reservoir—and its least understood—scientists and water managers are developing new insights into the factors influencing snow accumulation and runoff. The upshot? Communities get invaluable glimpses into water futures affecting farmers, recreationists, aquatic wildlife, and everyone else.

BY KELLY BASTONE

Every April 1, when most Americans are plotting April Fool’s pranks, water managers across Colorado fixate on the season’s streamflow forecasts. Initial predictions are released as early as January, but April 1 reigns as the most pivotal forecasting date because it’s late enough in the spring to mark the snowpack’s peak but early enough that runoff hasn’t started. It’s also early enough that irrigators and water managers can use these predictions to plan ahead. So for many, April 1 is considered the day when they find out how much water they will likely have that summer and when it will arrive. It’s like learning the balance of your bank account— because for this state’s farmers, cities, river outfitters and others, water is akin to wealth. And most of Colorado’s water starts as snow.

The blanket of frozen water crystals that covers our high country from November through May ranks as the state’s largest water reservoir by volume. And that melting snow has tremendous influence over our summertime streamflow patterns: Snowmelt runoff provides as much as 80% of Colorado’s annual surface water supply.

So assessing the snowpack and how it will feed Colorado’s streams, rivers and lakes

gives people a glimpse into the future. Food producers choose which crops to plant based on expected water deliveries, recreational guides may tweak their scheduled trips and staffing levels to suit projected water levels, and dam operators decide how to budget their releases to fortify reservoirs and regulate downstream flows.

At the Colorado-Big Thompson Project—which is operated by Northern Water and comprised of 12 reservoirs and 35 miles of tunnels that deliver water to communities and farms along the northern Front Range—managers use snowpack data to predict how much water they will need to tap from West Slope sources, and how much they can provide to their municipal and agricultural shareholders on the plains. Streamflow forecasts guide managers in making allocations, which tell Broomfield, Boulder, Fort Collins and other cities whether they will have excess water available to lease back to farmers. And with ample snowmelt in ditches and canals, farmers might opt to plant thirstier crops that offer a higher profit margin.

“Snow [data] also tells us how to move water through the system,” explains Northern Water spokesperson Jeff Stahla. Last winter, for example, snow monitoring confirmed that Lake Granby would fill by natural means, so

For this state's farmers, cities, river outfitters and others, water is akin to wealth. And most of Colorado's water starts as snow.

water managers never turned on the pumps that draw water to Lake Granby from Windy Gap Reservoir. “That allowed us to avoid the unnecessary cost of pumping,” says Stahla.

But measuring snowpack and translating that to predicted runoff volume isn’t easy.

The challenge stems, in part, from Colorado’s high elevations and dramatic terrain, which create significant variations in precipitation patterns across relatively short distances. The same storm that deposits a scant inch of snow on my driveway in Steamboat Springs may dump two feet of powder on the summit that rises nearly 4,000 vertical feet

above my home. It’s hard to account for all those variations in accumulation.

Yet the current boom in snowpack monitoring and modeling technologies is already providing water managers with a better crystal ball. And with a sharper view into the summer’s water supplies, planners can make every drop count for both residents and the environment.

In 1903, Enos Mills, the naturalist and mountain guide who was instrumental in creating Rocky Mountain National Park, became Colorado’s first snow observer, skiing or snowshoeing into the high country and reporting on snow and forest conditions.

Monitoring grew more formalized in the 1930s, when the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) began to create “snow course” sites where observers manually collected snow samples and calculated their water content.

These days, the NRCS continues to employ some of those snow courses but also uses automated Snowpack Telemetry (SNOTEL) stations equipped with “snow pillows” that calculate snow water equivalent (SWE), or the amount of water contained in snowpack. These broad, 10-foot diameter bladders are filled with liquid antifreeze and buried level with the ground, so that the weight of falling snow exerts pressure on the antifreeze, which is then measured and converted into SWE. Typically located in sheltered forest clearings on flat ground between 8,500 and 11,600 feet in elevation, SNOTEL sites look like buried alien landings

with variously shaped metal towers reaching out of the snow to measure conditions such as temperature, wind, precipitation and snow depth.

Such stations feed a data set that’s prized for its longevity. The record measuring snowpack and its moisture content now extends for nearly 100 years in some locations, providing historical averages that lend valuable context to the current year’s snowpack. Water users and managers rely on station data and the resulting forecasts to anticipate operations for the coming spring and summer.

But the measurements from SNOTEL stations and snow courses, while hugely valuable, only reveal so much about the state’s snow and how it may melt into waterways. They’re like scattered individual pixels in a big picture that forecasters and water managers would prefer to see in its entirety, at as high a resolution as possible. That’s especially true because most of Colorado’s water managers now struggle to consistently deliver desired water quantities to all stakeholders. “When you have less, you’d better know more, because every drop counts,” explains climate researcher and consultant Jeff Lukas.

Not only are water managers operating on ever-smaller margins of error, but they’re also experiencing greater climate variability from year to year. “Even if there’s no shift in the mean, the variance is getting bigger, and the year-to-year swing is getting bigger,” explains Jeff Deems. Deems helped NASA employ LiDAR sensors, or Light Detection and Ranging, for snow depth mapping, before co-founding

How

three water managers are using snowpack data to make smarter decisions

TAYLOR WINCHELL

“Forecasting is a tough game,” chuckles Taylor Winchell, a climate adaptation specialist for Denver Water. Denver Water makes use of a comprehensive network of SNOTEL sites that provide a continuous stream of data on each location’s snow water equivalent (SWE). The utility’s staff consult these daily to track snowpack and estimate how runoff will feed the watersheds and reservoirs that supply their 1.5 million customers. ¶ Once the snow around those SNOTEL stations melts, Denver Water staff have few ways to know how much water remains on the state’s highest summits. But in 2019, the utility started using Airborne Snow Observatories (ASO) across the Blue River watershed. One flight assessed peak snowpack, while a later flight calculated what remained after the SNOTEL sites had gone dry. That second flight indicated that there was more snow remaining at high elevations than was suspected. So Denver Water increased outflows from Dillon Reservoir to make room for extra water, avoiding downstream flooding. ¶ “Having this information about the volume of water in the snowpack is invaluable in decision making,” he says. “It tells us how we can better manage our water resources in any given year.” ¶ Still on his wish list is a reliable forecast for future seasonal precipitation. For now, Winchell repeats, “Predicting the future is never easy.” –KB

Airborne Snow Observatories, Inc. (ASO), a relatively new player on the snowpack monitoring, modeling and forecasting scene. Indeed, snowpack research and data gathering is surging. The NRCS is updating its SNOTEL stations and forecast models. Other entities, such as the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and ASO, have launched new monitoring options and related predictions. Advances are being made with research too, as lasers, artificial intelligence, satellite imagery, and cosmic ray neutron sensors all provide novel ways of assessing the volume and release patterns of Colorado’s largest reservoir. “We’re in a really exciting period right now,” says Deems, describing a revolution of snowpack assessment that’s generating new ideas, new sensor technologies, new runoff models, and new ways of collaborating over the emerging paradigms.

Until 2013, two agencies, NRCS and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, collaborated to produce unified runoff forecasts at locations across the Colorado River Basin and the eastern half of the Great Basin. NRCS processed the data from its SNOTEL stations into a statistical regression model that predicted the current season’s runoff based on past years’ snowpack amounts and runoff. NOAA fed NRCS data a more complex forecast model that assessed the processes acting upon the snow, such as temperature and snowmelt rate, and offered a prediction for the coming spring. The agencies compared their two forecasts and offered the public a single monthly forecast for each location from January 1 through June 1.

But starting in the 2013 water season, the agencies began publishing their own independent projections, marking the beginning of data multiplicity in streamflow forecasting. “We realized that we were washing out some important information from both our models, so we stopped issuing one single number,” says Paul Miller, hydrologist for NOAA’s Colorado Basin River Forecast Center. “The vast majority of the time, [NRCS and NOAA] issue very similar forecasts, but having more than one source gives users a greater degree of confidence,” Miller explains. Even when those forecasts don’t align, having multiple predictions helps users better prepare for runoff.

Both agencies have continued to refine their forecast models using the latest capability in computation. NRCS hopes to expand the SNOTEL network in Colorado over the next three years with a handful of new locations that impact multiple large watersheds.

NRCS also continues to update its

SNOTEL stations. For the first time, this past winter from 2023 to 2024, three sites featured an expanded suite of sensors that include solar radiation and snowpack temperature. Says NRCS snow survey supervisor Brian Domonkos, “By beefing up these sensors, we’re watching more than just SWE but also impacts to it.” Understanding the factors that cause snow to melt and sublimate, turning directly into a gas, at different rates is now a major focus of snowpack monitoring.

Senator Beck Basin is a perennially cold, treeless cirque in the headwaters of the San Miguel, Uncompahgre and Animas rivers. This is Jeff Derry’s field office: He frequently drives up Red Mountain Pass and treks to study plots located above 12,000 feet. Here, an array of air, snow and radiation sensors record factors that influence snow’s behavior once it reaches the ground. But as executive director of the Silverton-based Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies, Derry also seeks information that instruments can’t record automatically. As snowmelt season approaches, Derry digs pits in the snow to scrutinize layers of dust that have become a common snowpack feature in southwest Colorado. Wind pat-

80% of Colorado’s annual surface water supply is provided by snowmelt.

terns carry this dust out of neighboring Utah and Arizona and deposit it on the sky-kissing summits of the San Juans (and commonly on mountain ranges located across Colorado). When sun hits the dark-colored dust, it accelerates snowmelt—so Derry regularly slices into the layer cake to give water managers a prediction on when they’re likely to see related surges in runoff. Using dust on snow data from satellites as well as Derry’s in-field observations, NOAA’s Colorado Basin River Forecast Center tweaks its streamflow forecast model to account for the dust influence. Reservoir operators use Derry’s information to know when and how fast water will come

“I’m not someone who thrives on adrenaline,” admits Susan Behery, a hydraulic engineer with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Yet as operator of Navajo Dam, located on the San Juan River in northern New Mexico, Behery places high-stakes bets on water that would test any gambler’s nerve. ¶ Every spring, she decides when and how much water to release from Navajo Reservoir to accommodate winter snowmelt and summer monsoons. Sending too much water through the dam could result in flooding downstream. Yet endangered aquatic species below Navajo Dam require specific flow benchmarks that vary from 2,500 cubic feet per second (cfs) to 10,000 cfs. Meanwhile, Behery must meet delivery obligations to the Navajo Nation and Jicarilla Apache Nation. And Behery can’t execute quick strategy changes: She must provide two weeks’ notice of discharge fluctuations to give water users time to prepare for flows. ¶ Her basin is particularly affected by dust deposition, so Behery works closely with the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies to predict how dust will impact runoff timing into Navajo Reservoir and the Animas River, a tributary of the San Juan. Only by timing peak releases through Navajo Dam with peak flows on the Animas can Behery hit the flow targets required by endangered species’ recovery programs. In 2019, Behery used insights into dust-accelerated snowmelt timing to meet all her flow targets for endangered species and achieved a major win for their recovery programs. ¶ Behery is also following developments in soil moisture monitoring. “Everything runs off earlier with dust, and the sooner the snow goes away, the drier the soil becomes,” she notes. –KB

down the mountain and impact the resources that they manage.

These snow scientists and water managers are craving insights into storm and moisture trends that don’t always follow historical patterns. Dust, for example, has become more prevalent in Colorado’s snowpack as increasing human disturbances on desert soils loosen particles to prevailing winds. Dry soils in the mountain watersheds themselves are also influencing runoff volume. Extended periods of drought have left soils thirstier than they used to be, so they soak up more snowmelt and return less water to streams.

The monitoring equipment installed at various locations across Senator Beck Basin helps to quantify such unknowns. It’s an extraordinary site which, until the recent uptick in snow study, was one of just two sites in the West—the only site in the Upper Colorado River Basin—that collected the entire energy budget of the snowpack. This means that it measures all the variables, such as solar radiation and wind speed, that alter the snow after it has fallen. “Until very recently, we were the only high-elevation study basin collecting this data in Colorado,” says Derry.

The Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies has been doing this work for almost two decades: In 2004, the center received a grant from the National Science Foundation to purchase

instruments and conduct groundbreaking research into the effects of dust on snow that are now well established. But Derry continues to monitor dust deposition and analyze the snow’s reflective power, known as albedo, so he can relay that data to regional forecasters.

Although Senator Beck Basin is best known for its dust studies, the site also hosts snow researchers that test new instrumentation and monitoring approaches. The Durango-based Mountain Studies Institute, for example, initiated a new “snowtography” study this winter in an effort to understand how forest structures influence snowpack. Located in the trees adjacent to Senator Beck Basin, the instruments measure factors such as soil moisture, wind and ablation (snow loss) to observe how the forest canopy affects snow accumulation in open clearings, semi-forested areas, and dense stands.

Given the prevalence of beetle kill, wildfire and other changes to Colorado’s forests, Derry says, “We need to account for how that influences snow and soil moisture in the high country.”

Senator Beck Basin is also the location for a new USGS monitoring site—one of 14 new sites across the Upper Colorado River Basin

Colorado’s high elevations and dramatic terrain create significant variations in precipitation patterns, making snow surveying a challenge.

that the USGS installed for full operation this past winter. It’s one focus of the agency’s national effort to establish Next Generation Water Observing Systems (NGWOS) that provide high-res temporal and spatial data for complex water environments.

“We’re not trying to replace the monitoring that SNOTEL does,” says USGS research hydrologist Graham Sexstone. Instead, he explains, the USGS is striving to expand upon that system with stations situated in places where SNOTEL hasn’t traditionally operated—such as extremely high and unusually low elevations. Instead of positioning them in sheltered locations designed to measure snow-

fall, USGS monitoring sites occupy zones that are subject to wind redistribution, sun-exposed meltoff, and other physical factors influencing snow and the “snow to flow” equation. Says Sexstone, “We’re trying to represent conditions that we don’t already have a lot of data for.”

Each site is equipped with new sensors to measure SWE, snow depth, blowing snow, soil moisture, meteorological variables, and more. USGS staff also visit each site periodically with a sled-based ground-penetrating radar unit to measure the snow depth, and to fly a LiDAR-equipped drone to track changes in snow depth. Researchers also physically dig snow pits at the sites to compare those findings against station sensor data.

By using new sensor technology and monitoring zones that have either been lower or higher than the SNOTELs' reach, the USGS hopes to give forecasters insight into marginal—but potentially influential—aspects of the snowpack. “When factors influence places where SNOTEL sites can’t be, you miss anomalies,” explains consultant Jeff Lukas.

Lukas remembers how, in April 2010, when SNOTEL sites in Summit County did not capture the full extent of the disproportionately large alpine snowpack sitting above the sites, the magnitude of peak runoff in early June wasn’t well anticipated. Faced with surprisingly large flows pouring into an already-full Dillon Reservoir, Denver Water sent an unplanned slug of water to flow through the Roberts Tunnel to the South Platte River in order to avoid flooding downstream of Dillon. “Even if they don‘t happen very often, those near-crises are unnerving,” continues Lukas.

The USGS’ new monitoring efforts should provide more data points, and more warning, of such situations. Their data is fed into computational models that water managers use to crunch the numbers and predict when and how much water will enter area streams. Modeling turns discrete data points into real-world scenarios that irrigators, reservoir managers, cities and water utilities, and others can interpret and plan for. But as SNOTEL stations collect increasingly sophisticated data, that information is outpacing some models’ ability to digest and translate the data into forecasts.

Theoretically, the growth in snow monitoring data will make forecasting better, says Lukas, “if you have more detailed information about the snow and are able to translate that into information about runoff.” Models must be adapted for the new data sets that emerging research provides, and those evolutions can take time.

Yet even with more information and an expanded suite of sensors in more locations than ever before, point stations still represent just one pixel point in a vast and varying land-

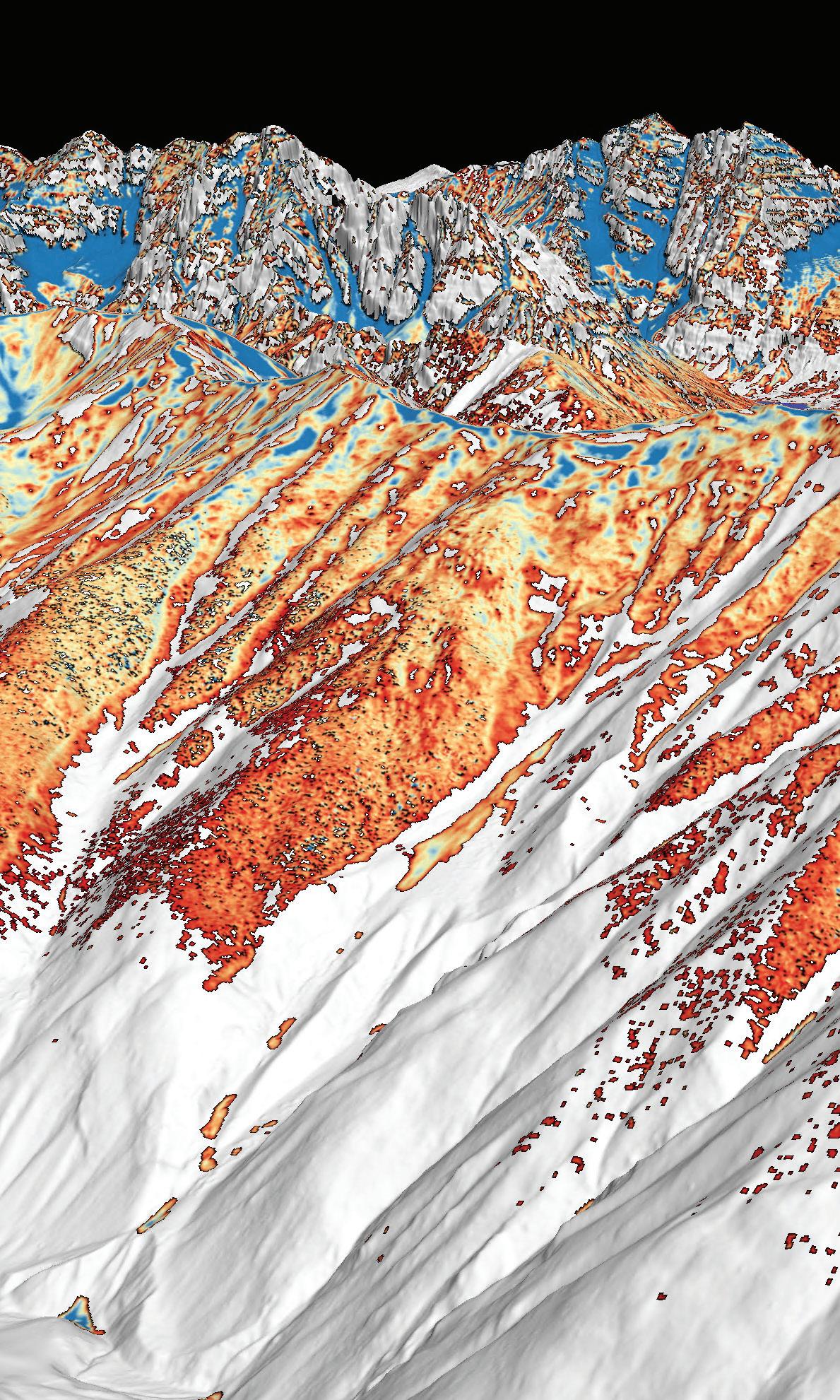

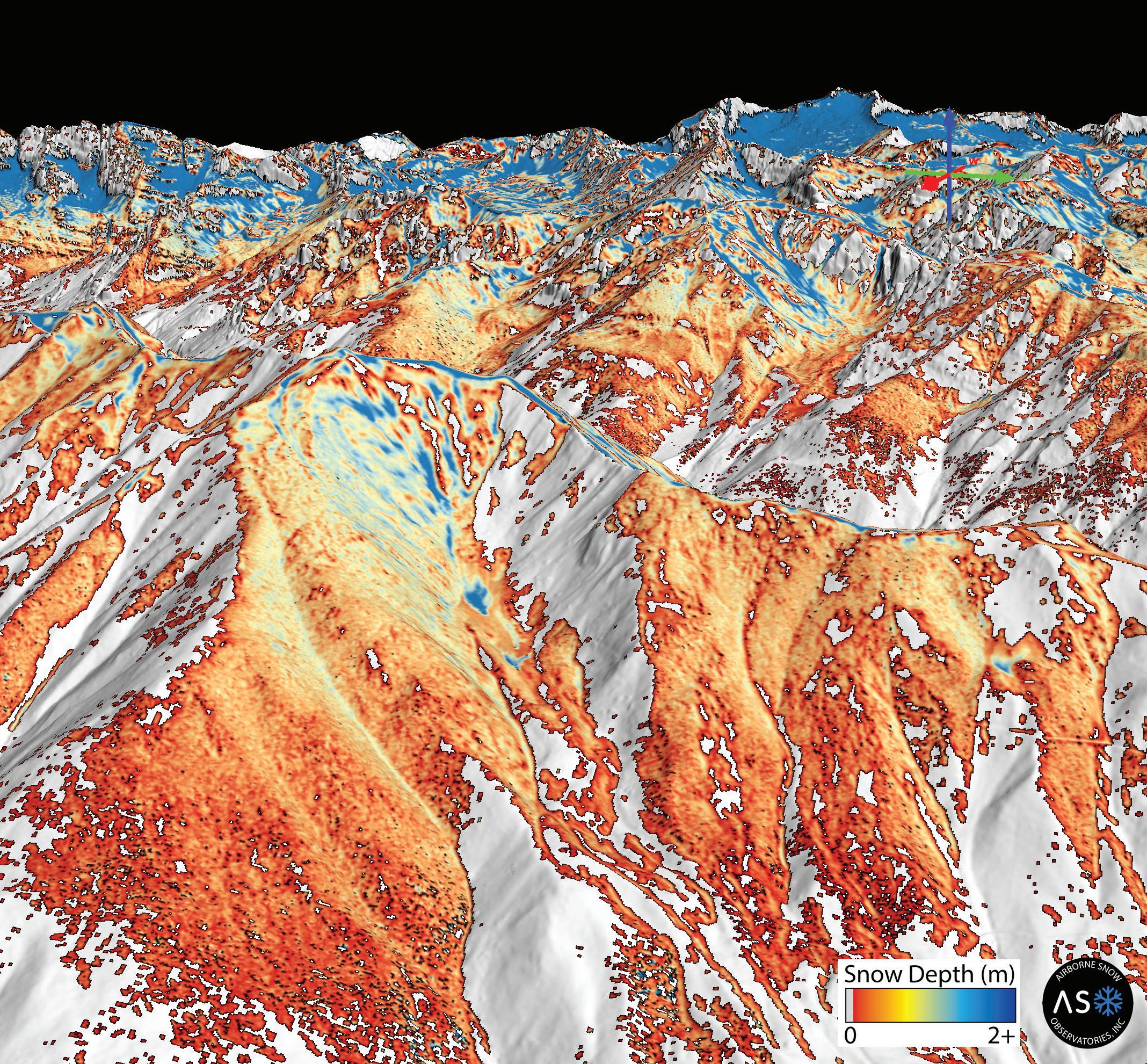

scape of snow. That’s why water managers are extremely excited about a new option that may prove to be a forecasting game-changer: Called Airborne Snow Observatories (ASO), the flyover technology promises to provide Coloradans with their first big-picture, high-resolution view of the snowpack and highly accurate estimates of the water volume contained there.

Colorado holds the distinction of having hosted the first-ever ASO flight, from Grand Junction in 2013, when the technology was under development at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. But it was California that first seized upon ASO’s potential to transform snowpack forecasting: That state’s Department of Water Resources has been commissioning flights over almost the entire Sierra Nevada range and Shasta River Basin since 2013. ASO data has helped California agricultural irrigators and aquatic wildlife managers budget their water and brace for anomalies. Now, the technology is here in Colorado.

“It’s the first operational advance in snow water equivalent monitoring since SNOTEL,” says ASO co-founder Jeff Deems. The flights read the terrain using two scanning technologies: A LiDAR laser maps the elevation when it’s dry and again when it’s covered with snow in order to measure snow depth, and an imaging spectrometer photographs the invisible wavelengths of light that indicate varying textures and impurities on the snow surface (and up to a foot below it). “When you know how much snow is there, and what color it is because of dust or other impacts to solar radiation, you can better quantify runoff,” Deems explains. And unlike point stations, ASO provides a spatially continuous picture over all aspects and elevations to provide the high-resolution portrait that water managers have yearned for.

In California, February 2022 ASO flights over the Feather River Basin documented just half the snow that had been suggested by point stations. By March, the ASO team documented that half of that already meager snowpack had melted off. “We triple-checked the data, but it ended up being correct because 60% of that watershed had burned within five years, and the soot from the standing dead trees had melted out the snow as the sun angles got higher,” Deems explains. That variability wouldn’t have been caught or predicted by existing melt models. So although ASO ended up being the bearer of bad news, “bad news early is better than bad news late,” he concludes. Advance warning gives communities the power to adapt to changing conditions.

The Rio Grande originates in Colorado's San Juan Mountains but flows for 200 miles through New Mexico and Texas to the Gulf of Mexico. To ensure fair distribution of its water, the three states signed the Rio Grande Compact of 1938. Today, Craig Cotten makes sure that Colorado complies. As division engineer for Colorado’s Rio Grande Basin, Cotten determines how much water to send to New Mexico. “Our obligation is based upon the estimates of the amount of water we think we’ll have through the system,” Cotten says. That amount is largely determined by runoff. ¶ Cotten consults three different forecasts to project how melting snow may affect flows. “Ideally, all three forecasts would be similar," but they aren't always, says Cotten. In such years, he relies on anecdotes from snowmobilers and others to decide which forecast to trust. If the forecast underrepresents the available water, Cotten may owe more water than expected because the compact obligation increases with flows. That would force him to curtail delivery to irrigators. Irrigators also complain about over-delivery to New Mexico. Says Cotten, “That water comes out of their ditch, and they could have used it if I hadn’t sent it away.” ¶ Sophisticated data helps him hit targets. Last year, Colorado owed 300,000 acre-feet of Rio Grande water to New Mexico, and the actual delivery came within 200 acre-feet of the target. “Usually, we aim for within 10,000 acre-feet,” Cotten says. His staff used data to adjust irrigators' curtailments daily. That let them hit the bullseye, which Cotten says is “pretty amazing. It’s as close as we’ve ever gotten.” –KB

Measuring snowpack alone doesn’t result in predictions about when and how it will melt into streams, rivers and reservoirs. To generate such forecasts, scientists design computational models that manipulate monitoring data into likely runoff scenarios. Some models use 30-year indices of the snowpack and its typical behavior to provide statistical simulations. Other, physically based models represent the energy and mass fluctuations from sun, wind, and natural processes. Here are the traditional and emerging forecast models that water managers consult to glimpse the future.

A streamflow forecast summary map, published April 1, 2024 by the Natural Resources Conservation Service. Numbers represent forecasted flows as a percentage of median.

Since the early 1990s, the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) has used a statistical model that correlates snowpack amounts to the runoff patterns typically observed under those conditions. But certain factors, such as dust deposition and charred trees post-wildfire, can reduce the accuracy of those forecasts. So in spring 2024, NRCS is launching a brand-new model called M4 (Multi Modal Machine Learning Meta System) that uses artificial intelligence to leverage six different modeling types into one averaged forecast. It still relies on regression analysis, the statistical method that informed the original NRCS model. But the power of AI to manipulate multiple model types has improved M4’s skill by 5% to 10%, according to NRCS tests using historical simulations. Says NRCS snow

survey supervisor Brian Domonkos, “The prevalence of machine learning has opened doors that weren’t available 20 years ago.”

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) operates four River Forecast Centers that issue runoff predictions for Colorado. All plug NRCS and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) data into a temperature-index model that digests various parameters, such as temperature, snow accumulation, soil moisture, and rate of snowmelt, and issues a range of forecast values. Called the Sacramento Soil Moisture Accounting Model, the tool infers how dry or moist the area is and produces forecasts based on elevation and basin. At some point in the long-term future, says hydrologist Paul Miller, NOAA might consider

swapping out elevation-based forecasts for a distributed model capable of breaking down regions into gridded zones that could better represent the high-definition data provided by Airborne Snow Observatories, Inc. (ASO). But for now, says Miller, “Our model is set up to handle multiple parameters really well.”

The NRCS and NOAA are no longer the only runoff models available: A growing number of entities are developing additional models that can account for complex spatial patterns, such as sublimation and wind redistribution of snow, or incorporate spatial data from ASO. The USGS is using SnowModel, a spatially distributed, processbased tool that simulates snow accumulation and melt. The National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and ASO are relying on a process-based model called iSnowbal to convert LiDAR-measured snow depth data into snow water equivalent (SWE). The National Water Center (a division of NOAA) is working to develop another runoff forecast model. Yet the proliferation isn’t excessive, says Graham Sexstone, who worked on the USGS Snow to Flow initiative of expanded snow monitoring and modeling. “There is a real strength in using multiple models, especially if we can coordinate efforts by running different models over similar domains,” Sexstone says. “All models have uncertainty. That makes comparisons between models very valuable.” –KB

In Colorado, ASO flights have been providing water managers with SWE data since 2013, and surveys have grown in scope each year. For winter 2023-24, ASO has been surveying 6,200 square miles of watershed. The flights encompass the Upper Colorado River above Windy Gap, the Blue River, Clear Creek north through through the South Platte and into the main fork of the Poudre River, the Roaring Fork, the Upper Gunnison, the Conejos, the Dolores, and the Yampa and Elk rivers.

Funding for these efforts comes from individual water providers, such as Northern Water and Denver Water, as well as the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) and a growing number of local, state and federal partners. These partners have been collaborat-

ing and funding the program through what’s known as the Colorado Airborne Snowpack Measurement (CASM) workgroup since 2019.

The technology is so expensive that individual communities and regions often can’t afford to commission their own flights. However, the benefits are great—and, says Deems, they’re well worth the cost. He points to a 2019 success in California’s Kings River Basin where ASO data saved stakeholders approximately $100 million in avoided water lease costs to meet water delivery obligations.

Colorado is already seeing its own gains. Last winter’s ASO flights across the Fraser River watershed provided Denver Water with better-than-ever data on how much snow remained on that region’s mountains. Using that knowledge, the utility was able to meet its needs while leaving more water in the Fraser River. The higher resolution snowpack data gave Denver Water the confidence to make localized decisions that benefitted the whole system.

“Previously we relied on only one SNOTEL site and one streamflow forecast point when determining how to manage that system of 30 diversion points,” explains Denver Water spokesperson Todd Hartman.

But ASO data convinced Denver Water that it could safely bypass unusual quantities into an upstream section of the Fraser River. Says Deems, “It provided more surety of operations for the diverter, while also benefiting communities by keeping water in the stream that wouldn’t otherwise be there.”

Yet to be solved is how ASO data will fit into existing forecasting models, if at all. Most current operational models can’t readily handle the spatial data produced by ASO, which also offers its own standalone runoff forecast. Plus, ASO mapping is most helpful when paired with measurements collected in the field.

“ASO leverages the SNOTEL measurements to confirm the measurements they get from the plane,” says Taylor Winchell, climate adaptation specialist for Denver Water. He embraces multiple insights into the snowpack as a net gain rather than an either-or choice. “Working in tandem [with the SNOTEL network] will paint the better picture moving forward.”

In Colorado, ASO and the CASM group got a boost in 2021 thanks to a Water Supply Reserve Fund grant via the CWCB, which facilitated a project to answer participants’ questions and identify a sustainable, longterm funding mechanism for facilitating ASO statewide. Those administrative pathways have not yet been finalized, but Winchell is already excited about what ASO offers. “Colloquially, we refer to the snowpack as

our largest reservoir, but historically, we haven’t had an accurate volume estimate of that reservoir,” he explains. Lake Mead, Lake Powell, Dillon Reservoir—all these bodies of water represent known quantities. ASO stands to unlock that number for Colorado’s snow.

Despite the recent proliferation of data describing Colorado’s snowpack, researchers and water managers still wish for more insight. Meanwhile climate change challenges runoff forecasters with quickly shifting norms.

“You can’t look at the snowpack’s percentage of normal and say, that’s the runoff we should expect. There’s a correlation, but the percentages don’t quite align,” explains Lukas. Warming trends make that relationship even more approximate because the recent climatic baselines used in forecasts always lag behind the real-time warming. Continues Lukas, “One challenge for forecasting in the future is making sure to incorporate up-to-date temperatures and their effects on snowpack, both with sublimation and runoff.”

NOAA has looked at swapping out historical records (from 1991, as an example) for temperature data that’s more in line with recent observations. But that hasn’t proven to be a magic bullet when accounting for climate change, says Paul Miller of NOAA’s Colorado Basin River Forecast Center. “Interestingly, the impact to our model was not as great as we expected,” he explains. “Temperature affected the runoff timing [making it earlier] but not magnitude, because we weren’t able to adjust evaporation to increase along with temperature,” he says. Making those dynamic temperature adjustments to modeled evaporation requires reconfiguring how evaporation is calculated in the model. With those adjustments now underway, Miller expects to publish findings within the coming year.

In some ways, snowpack represents the low-hanging fruit of water resources: Measuring its water content requires no insights into the future, as weather forecasting does. “It’s just sitting there,” says Deems. “If we know the snowpack really well, we can confine the uncertainties to harder-to-measure things, like future precipitation.” H

A freelance writer living in Steamboat Springs, Kelly Bastone covers water, conservation and the outdoors for publications including Outside, AFAR, 5280, Backpacker, Field & Stream, and others. She is a regular contributor to Headwaters magazine.

When deep winter snows result in low summer flows, and spring streamflow forecasts don't accurately predict river conditions, what's causing these gaps?

Coloradans are on the case, seeking answers and more accurate streamflow forecasting.

BY ALLEN BEST

Ranchers in Colorado’s Yampa River Valley traditionally measured the severity of winters by snow accumulation on their stock fences. Plentiful accumulation put the snow at the top wire, making it a three-wire winter. Four wires are now the norm on stock fences. No matter. By early March 2023, those wires at the foot of Rabbit Ears Pass were covered too. The Yampa Valley was sublimely white. It was a winter like the old days.

As expected, runoff was big and thrashing. Creeks tumbling through Steamboat Springs in May spilled over their banks. Downstream 75 miles, the Yampa River at Maybell peaked on May 18 at 16,500 cubic feet per second, more than 200% the average peak streamflow at that gauging station.

What happened afterward was very different. By July, the Yampa’s meager flows in Steamboat so concerned water managers that they nearly closed the warming river to recreationists in order to protect fish.

That big snowpack that resulted in headhigh snowbanks along the streets in Steamboat? It produced a big runoff. But thievery had also occurred. Who or what absconded with the water? And how?

This mystery was not entirely new. April 1 snow depth in the Yampa and most of Colorado’s river basins has rarely correlated perfectly with runoff. Whether spring weather turns wetter and cooler or hotter and drier can alter the runoff dynamics. “There is always that component of what the temperature and precipitation regimes are from April 1 through July,” says Karl Wetlaufer, a hydrologist and assistant supervisor at the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), the federal agency that delivers the longest-running and most-used runoff forecasts. “They really drive a lot of what those forecast errors end up being.”

Then, too, the traditional methods for measuring snowpack have fallen short. Data from snow telemetry (SNOTEL) sites, is collected automatically from stations across Colorado. But those stations are relatively few compared to the complex geography. One station provides insights about one station, not a whole hillside or mountain.

A climate that has turned warmer and some say weirder during the last 10 to 20 years has some water managers wanting new tools. Whether in the San Luis Valley or the Yampa River Valley, what lies on the ground on April 1 remains the best predictor of river flows come July, August and September.

Water managers, from ranchers and farmers to reservoir operators and city staff, though, want improved models and data that more completely reveal the complexity of what is happening. They want to better understand why a huge snowpack can, by July and August, be such a dud.

Patrick Stanko, at his ranch four miles downstream from Steamboat Springs, has been puzzling over changes since he was a boy in the 1970s and 1980s. Summers have become hotter, winters less cold. Snow is gone sooner.

“The big snow banks of winter just disappear,” says Stanko. Water disappearing into the atmosphere is not a new process. But higher temperatures exacerbate it, whether that loss is to sublimation, where snow transforms directly into a gas, or evaporation, where snow melts and that water enters the atmosphere as a gas.

Milk Creek, which flows through the ranch that has been in his family since 1909, has become intermittent in its flows. Late-season grasses that his 100 head of cattle graze have become sparser with lessening summer rains.

Most striking are cracks in the ground that Stanko has noticed in recent years. He believes they have something to do with the shifted

summer dynamics—dynamics that have implications into the next year’s runoff.

“We don’t get the rains that we used to get,” he says. “You used to be able to set your clock by the monsoon that would come.”

Haying in the Yampa River and other high country locations traditionally began in July or early August. Rain storms arrived almost simultaneously. If the rain forced ranchers to leave the grasses to dry, it was also helpful. Stanko says hay is best with 10% to 14% moisture content. Now, the timothy hay, brome grass and dryland alfalfa he grows on his 600 acres is often too dry after being cooked by hot winds.

Drying soils in fall have implications for spring runoff—the soils want their share of water first. That can bite into the total runoff, particularly in dry winters. Rainstorms in September have the reverse effect.

The 2024 Climate Change in Colorado report confirms many of Stanko's observed changes. For example, summer precipitation has decreased 20% across northwest Colorado in the 21st century as compared to 1951-2000. Models suggest drier summers may become the norm—even with increased winter precipitation.

And warming has made the atmosphere thirstier. Evaporative demand is another name for this thirst. Warm air can hold more moisture than cool air. If nothing else changes, warmer

temperatures boost evaporative demand.

The Climate Change in Colorado report, which was commissioned by the Colorado Water Conservation Board, cites a measure of evaporative demand called potential evapotranspiration (PET). It refers to the amount of water that would be evaporated or sublimated from the snow, soil, crops, and ecosystem if sufficient water was available. Between 1980 and 2022, PET increased 5% during Colorado’s growing season. When the ground holds less moisture, more of the sun’s energy heats the land’s surface and the atmosphere above it instead of evaporating moisture. This drives faster warming and lowers humidity.

Since 2000, streamflow across Colorado’s major river basins has been 2% to 19% less compared to the half-century before. Modeling studies have attributed up to half the declines to warming temperatures. And declining streamflows heightens the need to make the most of available flows.

The story of dry conditions and low streamflows echoes 250 miles to the south in the San Luis Valley. There, water appropriation dates are older, elevations a little higher, and mid-summer temperatures a trifle toastier. Fifteen of the 20 hottest daily maximum temperatures recorded

in Alamosa, including several in 2023, have occurred in the 21st century.

Snowfall in the San Juan Mountains largely determines how much alfalfa Cleave Simpson can grow on his farm south of Alamosa. The farm has water rights from 1879, but that isn’t senior enough to ensure reliable water deliveries, says Simpson, who is a Colorado state senator in addition to being a farmer and general manager of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District. State officials make adjustments to the water that can be diverted. “They do that every day,” says Simpson. “All in an effort to deliver to the state line as close as is possible the amount that we’re required to deliver.”

The Rio Grande Compact specifies how much water Colorado must deliver to downstream states. Depending on the year’s flows, Colorado sends between 35% and 70% of the Rio Grande’s water downstream. To ensure those deliveries, water managers must carefully calibrate flows they expect against demand from irrigators. Like those on the Yampa, water managers have wanted new ways of forecasting flows. “Because the old ways just aren’t working that well,” explains Craig Cotten, Colorado’s Division 3 water engineer, who leads administration in the Rio Grande Basin with the Colorado Division of Water Resources.

The old ways use primarily snow telemetry (SNOTEL) data, which is automatically collected from stations across the state. That data is used to project flows using what Cotten describes as a “fairly simple regression analysis.” In other words, if X amount of snow in the past produced Y amount of water, then

the same formula should hold today. But in the early 2000s, Cotten began to see that in some years, streamflow forecasts were not as accurate as he would have liked, he says.

What changed? Bark beetle infestations, by stripping trees of needles and exposing more snow to sunlight, altered runoff. So did wildfires, which in 2013 scarred 113,000 acres in Rio Grande headwaters areas. “That changed the dynamics of the forest system and how it related to the snowpack melting and running into the streams,” says Cotten. Dust-on-snow events work the same way. Dust blown from distant deserts accumulates on snow, drastically reducing the albedo, or reflectivity. The warmed snow melts more rapidly.

Overall flows have trended down. Flows on the Rio Grande at a gauging station near Del Norte, upstream from most diversions, averaged 8% less from 2000 through 2022 than during the preceding 50 years.

Snowpack in the Rio Grande’s headwaters in the San Juan Mountains was above average in 2019 and again in 2023, Cotten points out. But late-summer seasonal flows were below average. “Even in a good year, our farms and ranches struggle in the late season because we have below-average streamflow at that time.” And always, there's the need to meet compact obligations, a task that Cotten says has become harder because of tightening water supplies. With stretched water supplies, accuracy in forecasting is increasingly important. A new tool, the high-resolution LiDAR of Airborne Snow Observatories (ASO) has meant better data on the amount of water contained in

snowpack, and has improved runoff projections. Through ASO, a plane flies over entire watersheds or basins, collecting snow-depth data. Flights in 2024 include the Conejos River—of help to Cotten—and the Yampa and Elk rivers, among others.

“Whether it’s a county commissioner, a dam operator, or maybe Craig Cotten or another division engineer, their challenge is that they’ve got a forecast of runoff, timing and volume,” says Jeff Deems, a snow scientist and part-owner of ASO. “They need to operate their headgates, their allocation, their dam, et cetera, while recognizing that their forecast is uncertain and that there’s a range of outcomes that could be undesirable. They need to make the best decision possible under that uncertain framework.”

ASO claims it can achieve 98% accuracy in forecasting the amount of water contained in snow, known as the snow water equivalent, or SWE, across large areas. Water managers across Colorado, with the help of state funding, are contracting with ASO to collect data and boost their forecasting.

“It opens up understanding of different physical processes related to the snowpack that otherwise we may not understand very well,” says Angus Goodbody of ASO. Goodbody is a forecast hydrologist with the NRCS.

While this data is invaluable to many water managers, NRCS can’t yet use ASO data in its modeling. But NRCS, too, is rolling out a new forecast system this winter. Goodbody describes the forecasting tools as improving incrementally. By using various forecasting

It is rare that a watershed’s April 1 snowpack and forecasted runoff, when expressed as "percent of normal," match each other. In fact, they often differ by 10+ percentage points. This is because the runoff forecasts consider more factors than just the snowpack, such as soil moisture and total precipitation. In forecast models, snowpack itself is also represented in a more sophisticated way than a single basin-wide number like percent of normal.

There’s another, more subtle, reason for discrepancies between snowpack and runoff forecast numbers: The “normals” used to communicate them are calculated in different ways. Snow water equivalent (SWE) is typically shown as the percent of the long-term (30-year) median, while forecasted runoff is shown as the percent of the long-term average, or mean.

The median is used as the normal for SWE because it is less influenced by a few outlier high-snowpack years. In this situation—called positive skewness in the data—the average would give an inflated impression of the snowpack outcome that is typical or likely for the location.

Runoff data may also show positive skewness, but to a lesser degree than with SWE. Still, the average runoff at any given gauge in Colorado is almost always higher than the median. This means that the observed or forecasted runoff when expressed as the percent of average will be lower than if it were expressed as the percent of median.

For most gauges, this difference is a few percentage points, but it can be much larger. For example, for the Gunnison River near Gunnison, the NOAA Colorado Basin River Forecast Center’s official April 1 forecast for most-probable April-July 2024 runoff volume is 350,000 acre-feet. This forecasted volume is 100% of the average, but 111% of the median.

For comparison, the SWE on April 1 in the basin above the Gunnison gauge was 105% of average, but 117% of the median.

tools and models to analyze data, NRCS aims to mitigate “the vulnerability of any one of those models on their own,” he says.

New tools have also topped Andy Rossi’s wish list for the Yampa. From the Steamboat Springs office of the Upper Yampa Water Conservancy District, where he has been the district’s general manager since 2020, Rossi directs operations of the district’s two upstream reservoirs, Stagecoach and Yamcolo, which provide water to ranches and municipalities, including Steamboat Springs.

When he started working for the Upper Yampa district as an engineer in 2009, runoff forecasts were “becoming more and more unreliable and really difficult for us to get our arms around what was going on in the basin,” Rossi explains.

Temperature records for the Yampa Basin were very good. Soil moisture records? Not so much. Runoff predictions from past years mentioned soil moisture but relied solely on models. “There was no direct measurement of soil moisture going into our forecasting,” Rossi says. He decided the Yampa Valley needed to begin collecting data about soil moisture and atmospheric processes in order to see if and how soil moisture factors into runoff. Were dry soils sapping runoff, preventing it from reaching rivers? The puzzle was missing pieces. Integrating more non-snow data into runoff projections might improve forecasts.

A partnership began to coalesce in 2018 between the Yampa Valley Sustainability Council, Colorado Mountain College, and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography’s Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes. Guided by a team of 15, the collaboration yielded a pilot soil moisture and weather monitoring station in September 2022 near Stagecoach Reservoir. In 2023, with aid from the Colorado Water Conservation Board and the Colorado River District, two additional stations were installed in the basin. The team in early 2024 was working on six more stations upstream of Craig. The stations collect continuous soil moisture measurements and data on meteorological conditions with the goal of sharing that data so that stakeholders can make management choices about changing water supplies.

The aim, in part, was to generate new and valuable data that wasn’t being collected elsewhere, says the sustainability council’s Madison Muxworthy, the project manager. “We didn’t want to duplicate existing efforts, such as SNOTEL stations,” she says.

The sustainability council has collaborated with the NRCS to install more soil moisture

sensors at SNOTEL stations to go along with snowpack, precipitation and temperature data. The team will install four stations this summer and two more in 2025.

It’s still too soon to know the results of this monitoring. Measurements obtained from these new stations may reveal shortterm changes, but other insights may require 10 to 20 years of data.

A similar network of soil moisture stations already exists in Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley. There, 10 stations have been installed in an elevation band of 5,880 feet from Glenwood Springs to above 12,000 feet at Independence Pass. All stations have sensors to monitor soil moisture at depths of 5, 20 and 50 centimeters, and monitor soil temperature at 20 centimeters deep. They also record air temperature, relative humidity, rainfall, and more, recording measurements at least hourly.

This network was created by the Aspen Global Change Institute in response to local interest in measuring soil moisture in the Roaring Fork watershed. In 2012, as bark beetles proliferated, scientists at a small meeting on forest health identified soil moisture as a critical, understudied component of ecosystem vitality. With more than a decade of measurements, the data may help answer questions about hydrology and ecology in mountain systems.