Uit verre streken

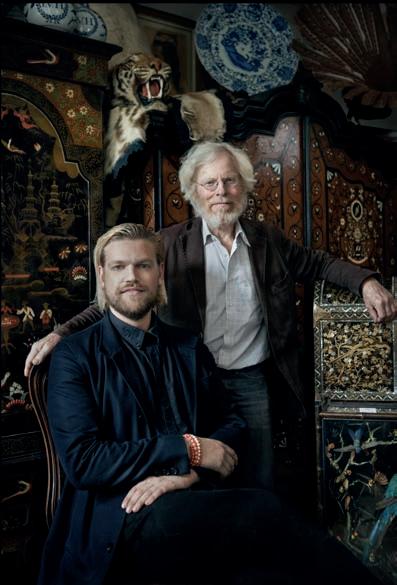

Guus Röell & Dickie Zebregs

Guus Röell & Dickie Zebregs

Uit verre streken from distant shores

“We sell Stories, not Fairytales.”

Amsterdam & Maastricht, Tefaf 2023

“We sell Stories, not Fairytales.”

Amsterdam & Maastricht, Tefaf 2023

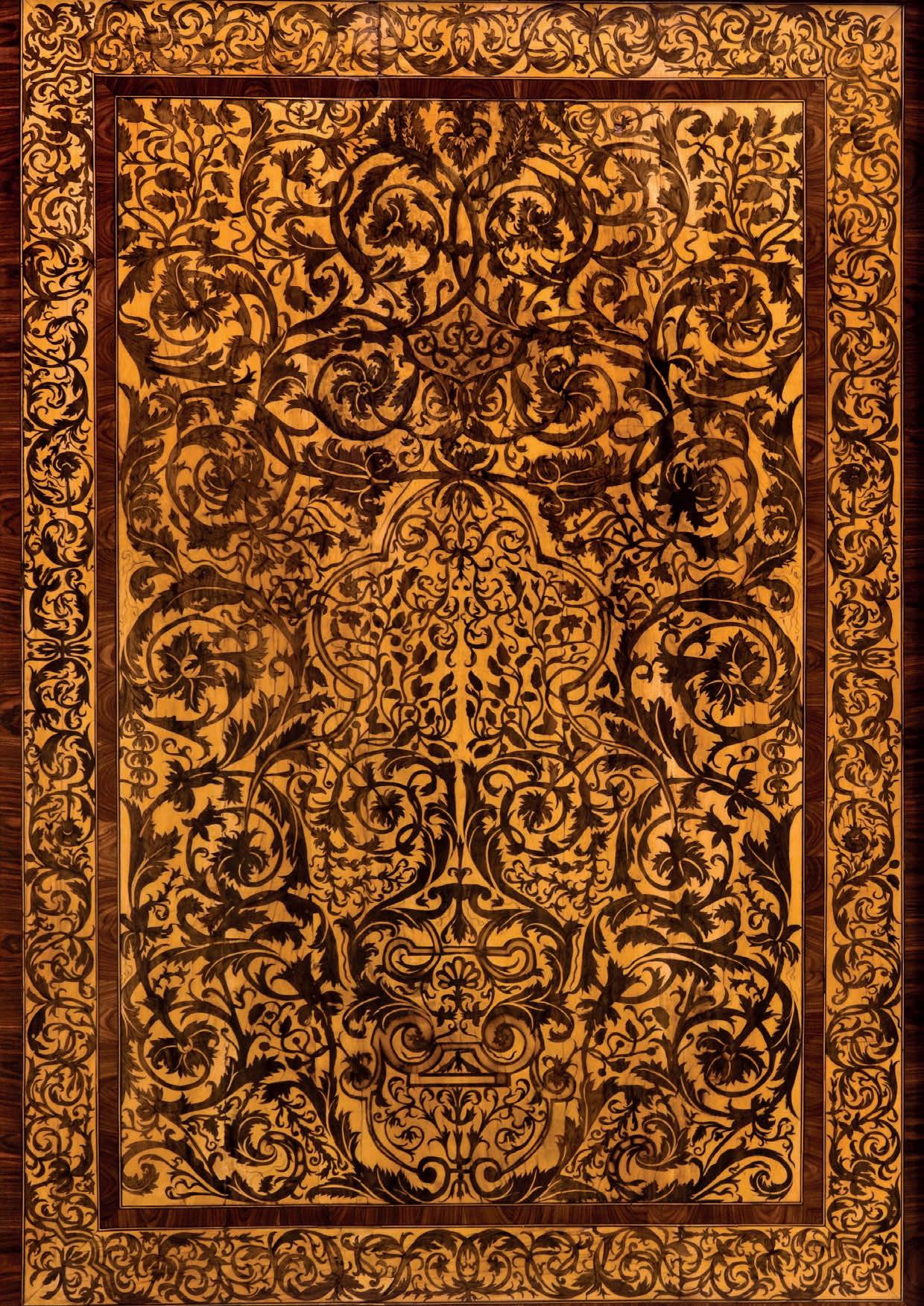

1. Charles Frederick de Brocktorff (1775–1850)

‘Camelopard – a present from the Pacha of Egypt to the King – at Malta on its way to England’

Signed and dated C.F. de Brocktorff. / 1827. lower right, inscribed as titled in the painted margins lower centre

Pencil and watercolour heightened with gold paint and gum arabic on paper, 36.8 x 27.9 cm

A gift so majestic, it made kings blush, and a gift so grand, it would startle Europe into a craze. Pasha Muhammad Ali of Egypt (1805-1848) did it in 1827: he sent to Europe three magical spotted, horned creatures, each with a neck reaching the skies and legs as long as a house is high. One giraffe to King Charles X of France, one to Francis I of Austria and the most fabled one to King George IV of England. A curious sight for Europeans, who had not seen such a beast since the Medici giraffe in 1487.

The English giraffe arrived in London by ship on August 11th, 1827, and was housed in the menagerie of King George IV, who is credited with establishing a private zoo at the Sandpit Gate of Windsor Great Park. His menagerie consisted of such exotic creatures as “wapiti, sambur, zebus, gnus, quaggas, Corine antelopes, llamas, wild swine, emus, ostriches, parrots, and waterfowl. There was also an ‘enormous tortoise’.” The showpiece of his collection, however, was the female Nubian giraffe, also called ‘Camelopard’ by the English. He was so worried about it, that he cared more about the creature, and forgot to govern his own state.

The state of the giraffe was indeed the talk of the town because from the beginning there was trouble. An artist commissioned to paint the English giraffe’s portrait now noticed that its lower limbs seemed deformed by injuries. Investigation revealed that on the stage of its journey from Sennar to Cairo on the back of a camel, the wounds had been caused because its legs were lashed together under the camel’s body. After two years, it became very debilitated from those early wounds and exercise became painful and problematic. Someone came up with a plan to keep the animal moving, and a gigantic triangle on wheels was constructed in which “the creature was somehow secured each day and trundled round her paddock, the hooves just touching the ground.” Despite this kind treatment, giraffes are accustomed to Africa’s warm and open savannah, not the cold and wet confines of a British zoo. Hence, two years after its arrival in England, the giraffe died, having grown only 45 centimetres in captivity. King George IV, obsessed with his giraffe, was terribly distraught over its death and commissioned the taxidermist John Gould to stuff his recently deceased pet. “The stuffer to the Zoological Society, Mr Gould, has had the performing of his duty... Soon after the Giraffe expired, De Ville, the modelist, was ordered down to Windsor, by His Majesty, and took a cast of the animal. From this cast a wooden form was manufactured, on which the skin of the animal is now placed, and which preserves its beauty to an extraordinary degree.” (The Times, April 15, 1830)

2.

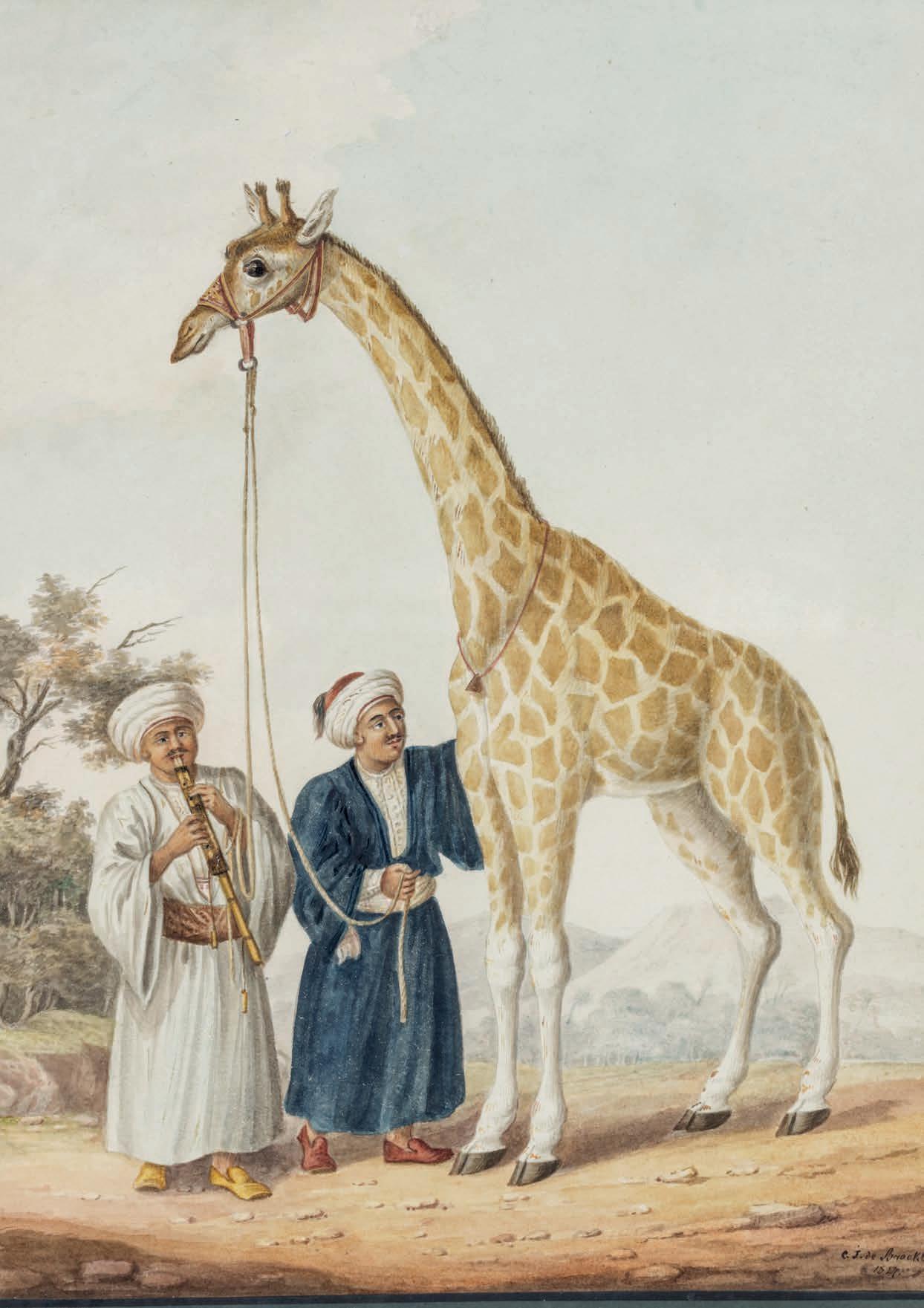

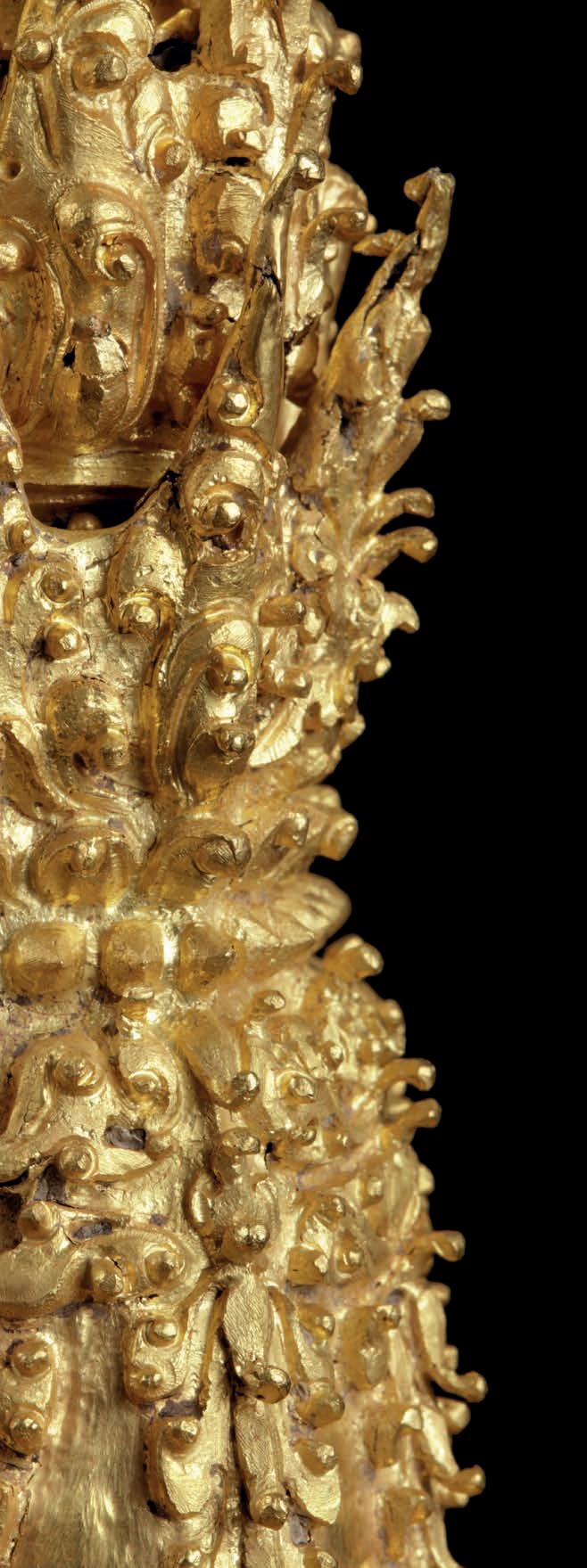

A superb bejewelled gem-set repoussé silver Ottoman miquelet flintlock rifle Ottoman Empire, Turkey, 19th century

The octagonal watered steel 8-faceted barrel and is damascened at the muzzle and breech with gold arabesques, with a lock with similar gold decoration dated 1038AH (1628 CE). The full stock is entirely covered in silver repoussé with floral scrolls, showing traces of gilding, decorated with two crescent moon appliques and centrally a star applique inset with cabochon-cut rubies, spinels, beryls, and emeralds.

L. 107.5 cm / L. 72.3 cm (barrel)

Provenance:

- Collection William Randolph Hearst, New York

- Private collection, New York

- Auction Parke-Bernet Galleries Inc., New York, 25 November 1953, lot 27 (ill.)

- Private collection, United States

A famous related example is the bejewelled gun, wrongly attributed as being made for Ottoman sultan Mahmud I (r. 17301754) in the collection of The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore (access. no. 51.84). The Baltimore gun, however, conceals compartments for a dazzlingly adorned dagger like the one included with this gun - and a set of writing instruments.

However, to get to these, one has to open the hinged door bearing the diamondencrusted insignia or tughra of Mahmud I and the date AH 1145 (1732/33 CE). This date and the date on the gun present should not be read as the year when it was made but rather as a tribute to the past, a mistake often made by European scholars. Though in other cultures, honouring previous rulers or periods by using their name or insignia on art is very typical. The Ottoman empire evolved around the capital and only provided for its royal court. In their turn, the Sultans could gift these exuberant gifts to local rulers, such as the Khedive of Egypt, a local Shah, the Dey of Algiers or Tunis. Unfortunately, only some have survived the test of time since (probably when the Ottoman empire fell). Choosing a silver or gold coin over a silver or gold gun is more attractive, and most were melted down. Another closely related gun, a miquelet pistol, can be found in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum in New York (access no. 23.232.9), and another comparable 18th century one can be found in Robert Elgoods The Arms of Greece and Her Balkan Neighbours in the Ottoman Period, p. 34.

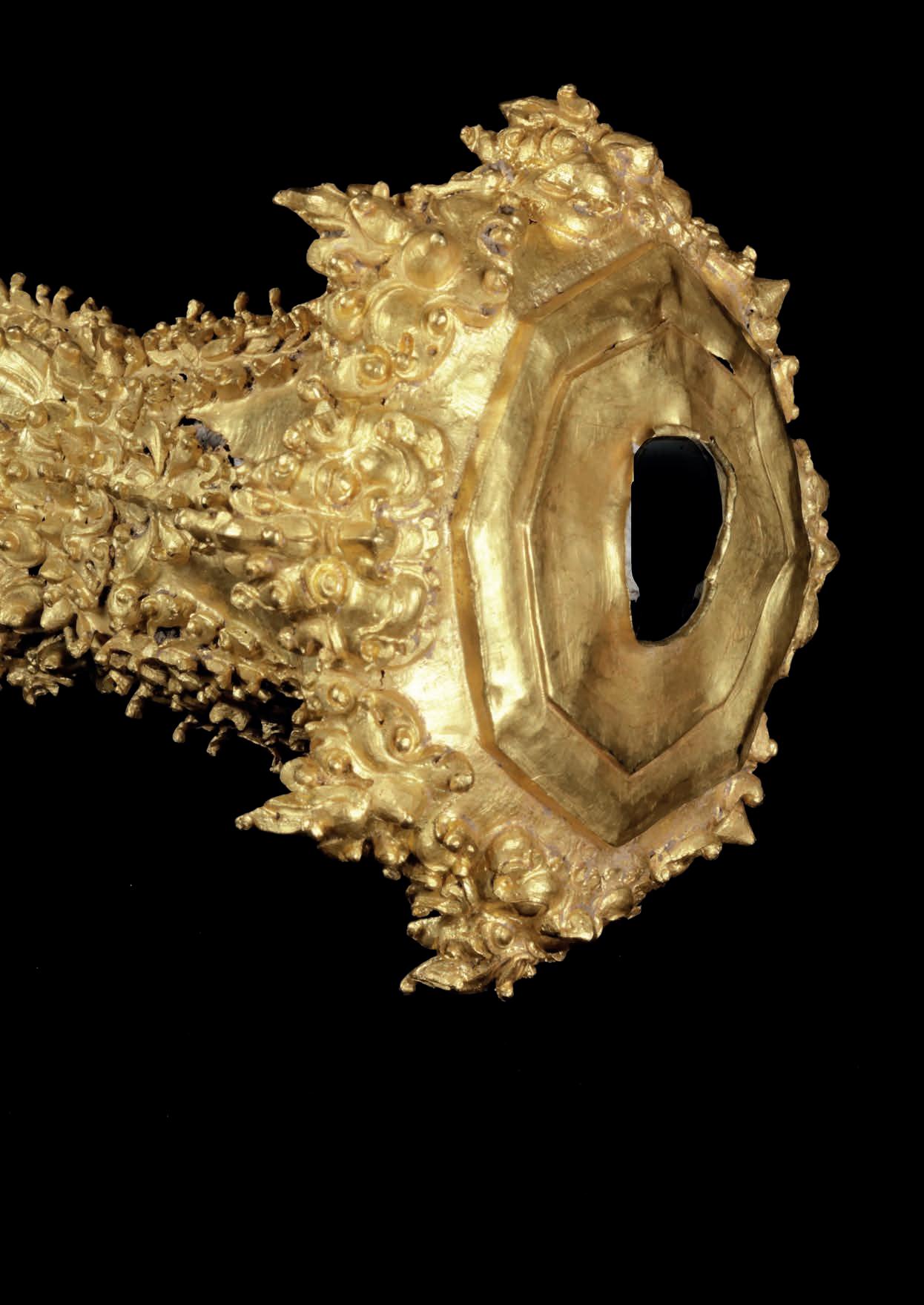

Ottoman hançer

Ottoman Empire, Turkey, 19th century

The dagger’s hilt is carved from a single block of pale nephrite jade with an ethereal, luminescent glow. Eye-shaped garnets and emeralds are inset over the grip in a symmetrical arrangement using the kundan technique and evoking tiny blossoms, with a vibrant, fully open matching floral design at the top. The Damascus steel blade is slightly curved in an elegant line and of superior quality. The robust, engraved, fuller, reinforced by double grooves, rises boldly from a central, leafy design in gold on both sides of the blade. The scabbard has, just beneath the locket, a natural bright blue star sapphire (confirmed by using a digital microscope). The silver shows traces of gold inlay and has mounts exuberantly decorated with roses of numerous sparkling rubies, emeralds, spinels, and beryls.

L. 48 cm / L. 29.5 cm (blade)

Provenance:

Runjeet Singh ltd., London

This opulent hançer, or dagger, represents a fine example of this weapon type and is well preserved. These ceremonial weapons are known to have been presented to Edward VII and are preserved in the Royal Collection Trust today. Similar daggers, such as some with calligraphic inscriptions, can be seen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (access. no. 36.25.994) and the British Museum (access no. 1878,1230.902). Blades like the one present are tempered in such a way as to display distinctive motifs of banding and mottling, which are reminiscent of flowing water. In addition, they are resistant to shattering and can be honed to a sharp, resilient edge. For a comparable dagger, see: Alexander, Islamic Arms and Armor in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 79.

Literature:

- Robert Elgood, The Arms of Greece and Her Balkan Neighbours in the Ottoman Period, Thames and Hudson, London, 2009. p. 34 (ill.)

- David Alexander, Stuart W. Pyhrr, & Will Kwiatkowski, Islamic Arms and Armor in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015, pp. 203–205 (ill.)

4.

A shagreen covered and patridgewood (Andira inermis) veneered coffre fort or Captain’s chest with elaborate gilt brass mounts

France or England, late 17th /early 18th century

The use of shagreen, or sting-ray leather, dates back to the 2nd century CE China, and later Japan, where it was used in weapons for grip. The earliest known use for decorative purposes was in the form of furniture during the 16th century. Portuguese traders, being part of the greatest naval force in the world, imported Japanese Namban lacquer coffers adorned with shagreen, gold and mother-of-pearl. This, however was short-lived as the Dutch began to rule the seas and monopolized trade with Japan, and thus the trade in shagreen.

Throughout the late 17th and early 18th century English and Dutch craftsmen ordered the novelty material to cover decorative items such as boxes, knife skins and shaving kits. It was regarded as one of the most luxurious materials used on objects, making the present coffre fort, probably owned by a high official or nobleman, priceless.

5.

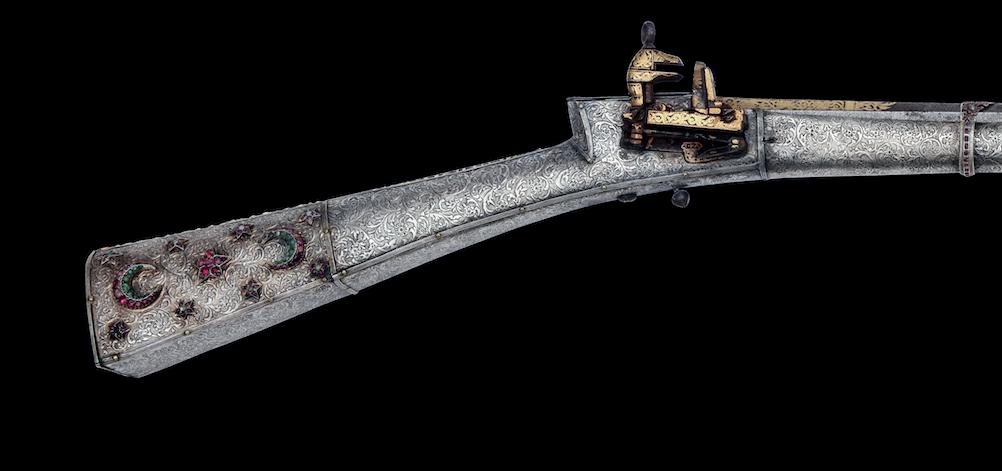

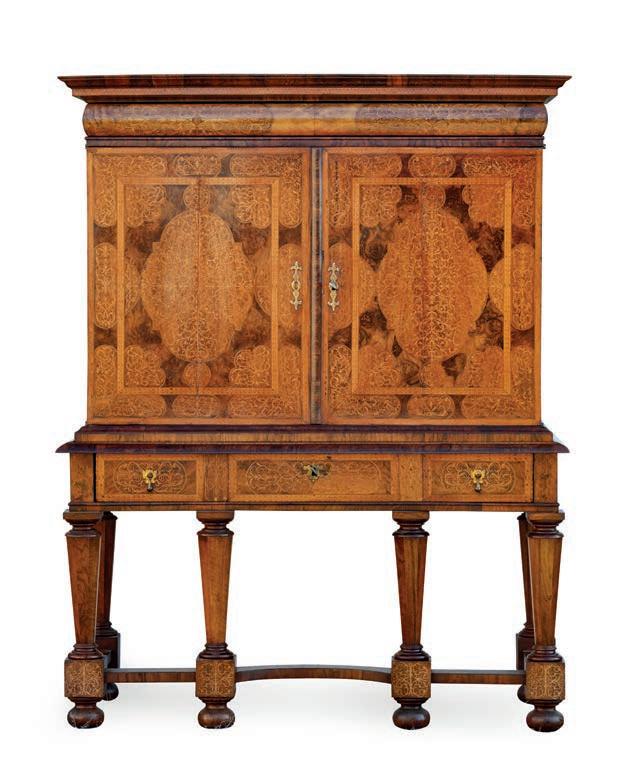

A magnificent Dutch marquetry cabinet on stand, by Jan van Mekeren (1658-1733) possibly made for William III and Mary of England

Amsterdam, circa 1687

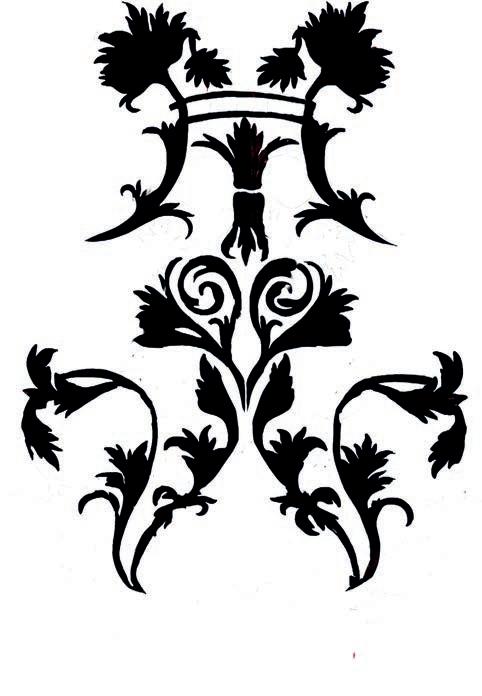

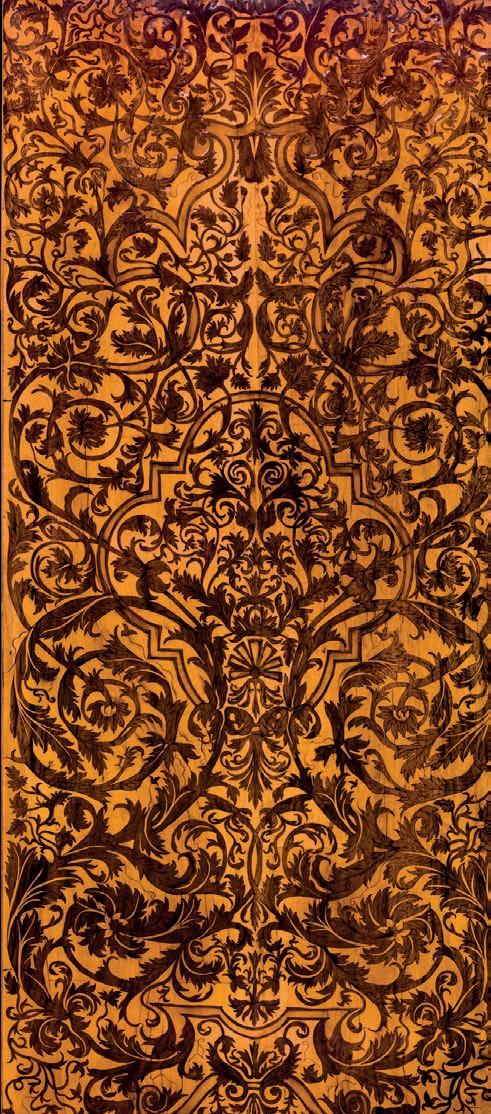

The oak cabinet is decorated with ‘arabesque’ or ‘seaweed’ marquetry in Turkish walnut (Juglans regia) on a holly (Ilex aquifolium) font, surrounded by a kingwood (Dalbergia cearensis) border. The top has a modest rectangular cornice of a frieze over two doors revealing the interior fitted with four shelves and five drawers. The inside of the doors and the drawer fronts are veneered with plain cedar (probably Cedrus atlantica). The stand has a frieze drawer and is raised on six S-shaped legs, joined by shaped stretchers and raised on turned ball feet. The entire cabinet, from the cornice to the stretchers, is covered in marquetry.

H. 209 x W. 178 x D. 67 cm

Provenance:

King William & Queen Mary of England or their very close circle, thence by descent (possibly) Noble collection, England

Literature:

Monique Riccardi-Cubitt, Art of the Cabinet, Thames & Hudson, London, 1992, ill. p. 96 (as English, c. 1695)

The stellar feature of this cabinet is the fine marquetry, which shows scrolling vines, plants, and fruits, clearly recognisable but abstract. The latter’s design was not chosen randomly, for it is filled with symbolism specific to the marriage between William of Orange and Mary Stuart. The letters M and W can be found above each other on each side of the cabinet, with vines and leaves forming a heart in between, praised on each side by a narcissus (a spring flower symbol of new beginnings), placed within a giant thistle. W is in the centre of the cartouche, but M is not. When the M is noticed, one will also see the thistle. Further, the well-known symbols for the House of Orange, recognisable by many in the Netherlands, have prominent places on the cabinet, such as the Appeltjes van Oranje, which are oranges and their blossom (recognisable because it is the only plant bearing fruit and blossom at the same time); roses for England, olive branches, a symbol of peace and stability (a result of the alliance between England and Holland); thistles (the symbol of the House of - Mary - Stuart, and Scotland); mistletoe, growing in pairs of

branches and leaves (stands for being a couple) and is evergreen (for eternity); hazelnuts for fertility; and sunflowers for the transitoriness of/ and kinship. There is, even more iconography, but intended for a specific spectator, possibly even William and Mary. The eagles, which stand for sharp insight and high ideals, pick wheat that could stand for life after death, reminding the spectator that however high one’s ideals are, life is limited. Furthermore, a heart shape within two laurel wreaths can be seen at the top centre of the doors, which could stand for the victory of love as the result of the marital alliance. Finally, the acorns (fruits of endurance and power), combined with blackberries, remind the spectator that there is always a limit (to this same power).

The daffodils beneath M love W on each side of the cabinet contribute to the exciting possibility of this cabinet’s royal provenance as they also symbolise ten years of marriage. Could this cabinet have been a gift by Mary to William to decorate Huis Honselaarsdijk when they celebrated their anniversary in 1687? The

presumed date of this cabinet certainly

Today we can’t comprehend that 17thcentury people would immediately understand the symbolism. However, sources prove that myths and symbolism were part of education and shared knowledge, at least amongst the literate and educated upper class. With the intricate decoration, a cabinet like this would be a good enough conversation piece for William’s and Mary’s status. After all, a generic one with just a geometric motif was for ordinary people. On the other hand, a cabinet with custom-made iconography would be most entertaining to guests in a candle-lit drawing room. You can imagine a company chatting about the different flowers and their meanings. Another argument for the symbolism being not hidden is a bureau in the Royal Collection Trust, which Gerrit Jensen delivered (in whose studio Van Mekeren worked) in 1690 to William and Mary. The decoration holds the same flora and symbolism as this cabinet, the only difference being a clear monogram with a crown above. The symbolic plants and flowers are just as present on the cabinet, but with a monogram, showing that they were not hidden on both pieces. There is also a gueridon known, not documented, but by repute in the United Kingdom, with the same decoration.

Now the essential feature of the cabinet is something never seen on Dutch period furniture before. It is something that - if not mentioned here - many would not even notice. When taking a few steps back, the scrolling vines, plants and flowers will combine, revealing a ferocious but proud Dutch crowned lion’s head on each door glaring back at the spectator.

All these symbols, together with the lion and eagles, are seen on the portrait of the young William III by Jan Davidsz de Heem and Jan Vermeer van Utrecht and on an engraving by Pieter van Gunst after Jean Henri Brandon and the designer seems to have used this image for the decoration of this cabinet. Even more plants with their meanings can be identified, as well as combinations that were intended to

be made, which could reveal even more spectator-specific meanings. Unfortunately, much of the meaning of the 17th century and earlier symbols has been lost or has yet to be studied.

Jan van Mekeren had six children with his wife, Maria. He had intended for his first son Fikko, born in 1693, to succeed him as a cabinetmaker, but unfortunately, Fikko died in 1731. After Jan’s death in 1733, the wood trade was continued by his daughter-in-law, but there was no one able to continue his cabinet-making business. Despite a 1624 regulation stipulating members of the Amsterdam cabinetmaker’s guild who offered their wares for sale in the guild’s shop, furniture makers in 17th and 18th century Holland hardly marked their work. However, thanks to the inventory after Jan’s death, there is a good list of his workpieces with thorough descriptions, prices, and the names of his clientele. The estate included many finished and unfinished pieces of furniture, an extensive collection of cabinet woods, and, most interesting, a long list of claims with names of the debtors and the amounts due. Most debtors were well-known Amsterdam patricians.

This cabinet is officially the eighth documented cabinet entirely attributed to, and thus by, Jan van Mekeren. The cabinet’s construction is nearly identical to that of the Van Mekeren Cabinet already in our collection, but also to that of the cabinet in the Rijksmuseum. The construction of the

Musée

‘Flower Garland with Portrait of William III of Orange, 10 years old’

Portrait by Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606–1683/1684) & garland by Jan Vermeer van Utrecht (1630-?)

‘Flower Garland with Portrait of William III of Orange, 10 years old’

Portrait by Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606–1683/1684) & garland by Jan Vermeer van Utrecht (1630-?)

doors is still original and identical to that of the Rijksmuseum. Furthermore, some parts of the marquetry design on the doors and the central marquetry at the front and sides of the frieze are the same as the design on other cabinets by Van Mekeren. Two other cabinets of similar form to the present one are known, which can be found at the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. The other is in the National Trust Kingston Lacy, United Kingdom. However, the construction has not been studied, and the marquetry differs - although it is of the same quality.

Van Mekeren stayed in London around 1682, presumably to master the art of marquetry. There he is mentioned as an employee of Gerrit Bream, another Dutchman who worked as a furniture maker and marqueteur. It is almost certain that Van Mekeren learned from and worked for Gerrit Jensen (1667-1715), England’s

most famous furniture maker. The influence of Jensen is visible in the cabinet present since the marquetry is still in a somewhat English style. Together with the form of the stand, it is an argument for the dating of this cabinet and the possibility of it being one of the earliest works by Van Mekeren. Remarkably, the other two cabinets mentioned earlier have the same stand but differ in marquetry. The Fabergé cabinet shows a more ‘seaweed’ marquetry closely related to the Jensen workshop manner, and the Kingston Lacy cabinet a bolder marquetry closer to Dutch fashion. The cabinet presented here is right in between and therefore shows a certain tranquillity in the composition. Arguably, these cabinets were made shortly after one another after his arrival around 1686-87 and show Van Mekeren losing the influence of Jensen. The Fabergé cabinet was probably made

6.

A charming collector’s cabinet by Gerrit Jensen

London, late 17th century

H. 163 cm x W. 127 x D. 53 cm

From our collection, now on view and available in our Amsterdam gallery.

7.

The ‘Blommenkast’ floral marquetry cabinet-on-stand by Jan van Mekeren (1658-1733)

Amsterdam, circa 1700

H. 206 x W. 171 x D. 61 cm

From our collection, now on view and available in our Amsterdam gallery.

The sides of the cabinet with on the right the thistle with the initials M W in the centre highlighted.

The sides of the cabinet with on the right the thistle with the initials M W in the centre highlighted.

right after Van Mekeren’s return to the Netherlands, possibly even with Jensen’s marquetry brought with him as a head start. Because of this ‘Jensen’ style marquetry, we can assume it was made in 1687, just after he returned to Amsterdam and was registered with the cabinetmaker’s guild.

Van Mekeren struggled with some difficulties he encountered while making this cabinet. However, that would be most strange for a master kistemaker who could create such complex furniture. The marquetry sometimes does not fit the design properly, and the S-shaped legs can be perceived as slightly awkward, leaving a small space between the cabinet and the wall behind it. Furthermore, the marquetry on the legs ends on plain veneer at the stretcher at some points. The possibility of the legs having been turned later has been ruled out by inspecting the construction and (lack of) traces of restoration and the lack of plain veneer at the backs of the legs that are out of sight.

The most noteworthy of all faults can be seen on the sides of the cabinet. On the side of the doors, the marquetry is cut off by the plain veneer border, which makes it asymmetrical. The reason is that the door breaking the frame when opened was not considered while designing the side. This points out the possibility of Van Mekeren using a design. Recently, when looking for a design, one can consult the Decorative Art Fund collection of the Rijksmuseum. Unfortunately, a specific design for this cabinet is not present, but they all point towards Daniël Marot (1660/1661-1752), the personal designer to Mary and her close circle. Could it be that he granted her wish and designed a cabinet? It would point out that Van Mekeren - who didn’t solve the problem - did not struggle in designing but rather struggled with the cabinet designer.

Therefore, Marot and Mary would be aware of the symbolism, which can be found in the famous Amalia Cabinet by Willem de Rots dating from 1652-1657, ordered by Amalia van Solms and now in the Rijksmuseum (BK-2005-19). Perhaps Mary was inspired by this cabinet when she saw it in the Netherlands. We can for sure say that Marot knew the cabinet since he was a nephew of Willem de Rots.

Sources:

Adam Bowett & Laurie Lindey, “Looking for Gerrit Jensen” in: Furniture History, Vol. LIII (2017), pp. 27–50

Lunsingh Scheurleer, ‘Jan van Mekeren, een Amsterdamsche meubelmaker uit het einde der 17de en begin der 18de eeuw’ in: Oud-Holland 58 (1941), p. 178

Wichers Hoeth, ‘Jan van Mekeren’s gesticht “De Eendracht”’ in: Jaarboek Amstelodamum 39 (1942), p. 109-129

Turpin, ‘Floral Marquetry in late seventeenth-century England and Holland’ in: Leids Kunsthistorisch

Jaarboek 13 (2003), p. 207-230

Jongh, Portretten van echt en trouw: huwelijk en gezin in de Nederlandse kunst van de zeventiende eeuw, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, 1986, no. 33, 38, 39 & 56

Yvette Bruijnen, ‘Sophia Anna van Pipenpoy geschilderd door Wybrand de Geest’ in: Rijksmuseum Bulletin (2006), 54, no. 4, pp. 358-369

James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, Routledge, Oxfordshire, 2014

8.

A mammoth ivory figure of an African Amor Flanders or South Germany, 17th century

On an oblong base, his head facing upwards, the ivory with a nice patina.

H. 17.3 cm

This figure in ivory seems to be full of iconological meanings. With the bow and arrows it is an Amor but since the bow, the quiver of arrows and one single arrow are laying on the ground together with a shield, they may symbolize unsuccesfull or fended off love. The Amor playing with his penis and blowing a whirligig together may be symbols of the fickleness and transitoriness of love. The chain with cross around his neck is a Roman Catholic symbol and may point to a Catholic country of origin, perhaps South Germany or Flanders.

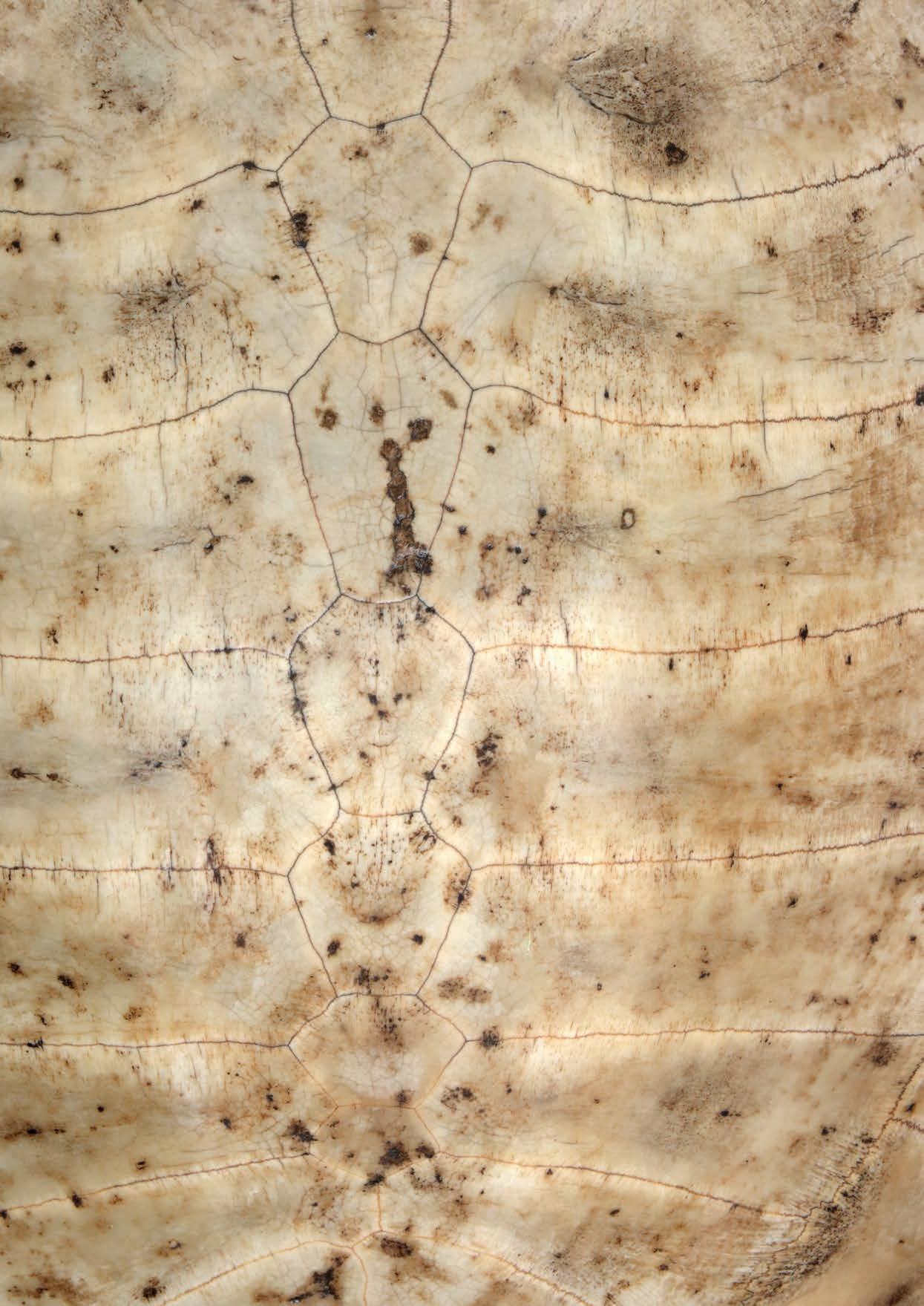

9. A unusual carved painted, gilt and gem-set tortoise carapace resembling the mythical Cosmic or World-bearing Turtle

Probably Germany, late 19th century

L. 32 x W. 26 x H. 20 cm

Provenance: Private collection, Munich

Following the natural forms of the carapace, the artist carved medals all around and painted a surprising portrait gallery depicting the different peoples of the world, amongst them Maori, Sinhalese, Chinese, Tartars, Papuans American Indigenous, Inuit, Persians, Europeans and many more. On the upper part of the shell, coats-ofarms belonging to China, The United States, Chile, Uruguay, Colombia, and Persia. Furthermore, the shell is decorated with miniature copies of famous Romantic paintings, and images of nature and men and with geometric patterns in polychrome and gold. An approximate globe map sits on the final, slightly rounded part of the shell.

In 19th century Germany, the Romantic wholesome idea of the mythical Worldbearing turtle, appropriated from American Indigenous, Chinese and Hindu Mythology, was still very alive and an attractive thought. In the Wunderkammer, the criteria which governed the selection of objects, rarity and strangeness served to blur the boundaries and create a direct synthesis between the three kingdoms of ‘Exotica’, ‘naturalia’ and ‘artificialia’. As a whole, this meticulously decorated carapace is a formidable example of everything above.

10.

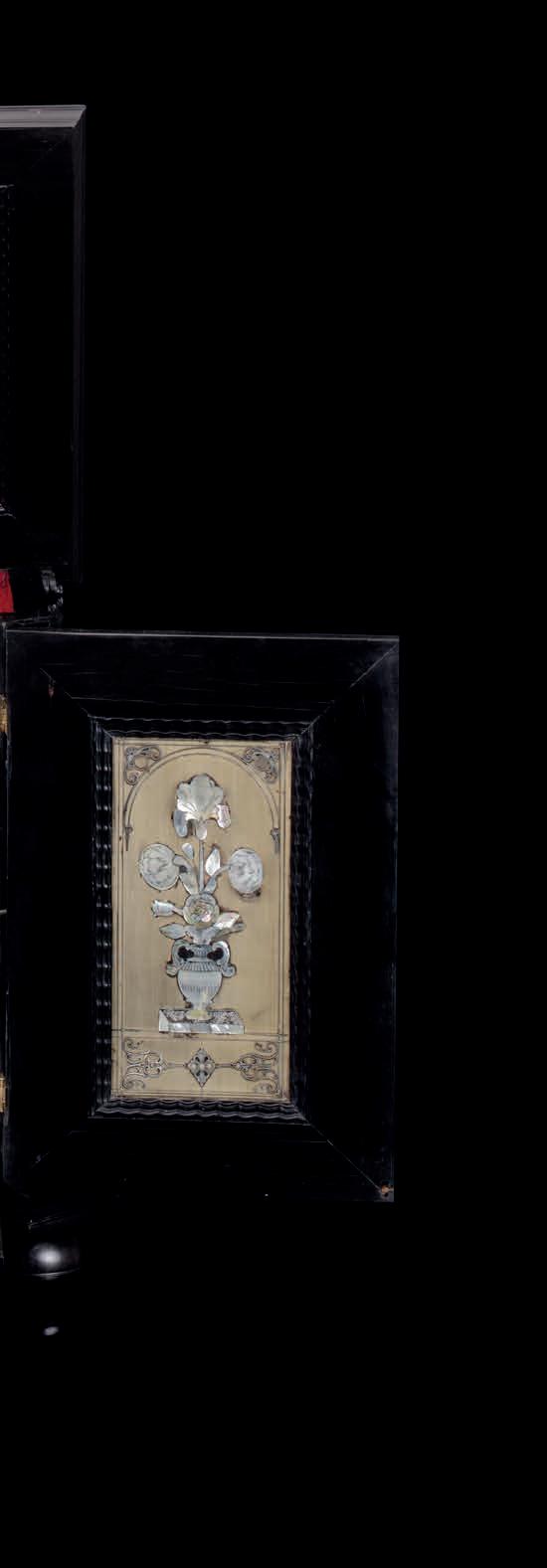

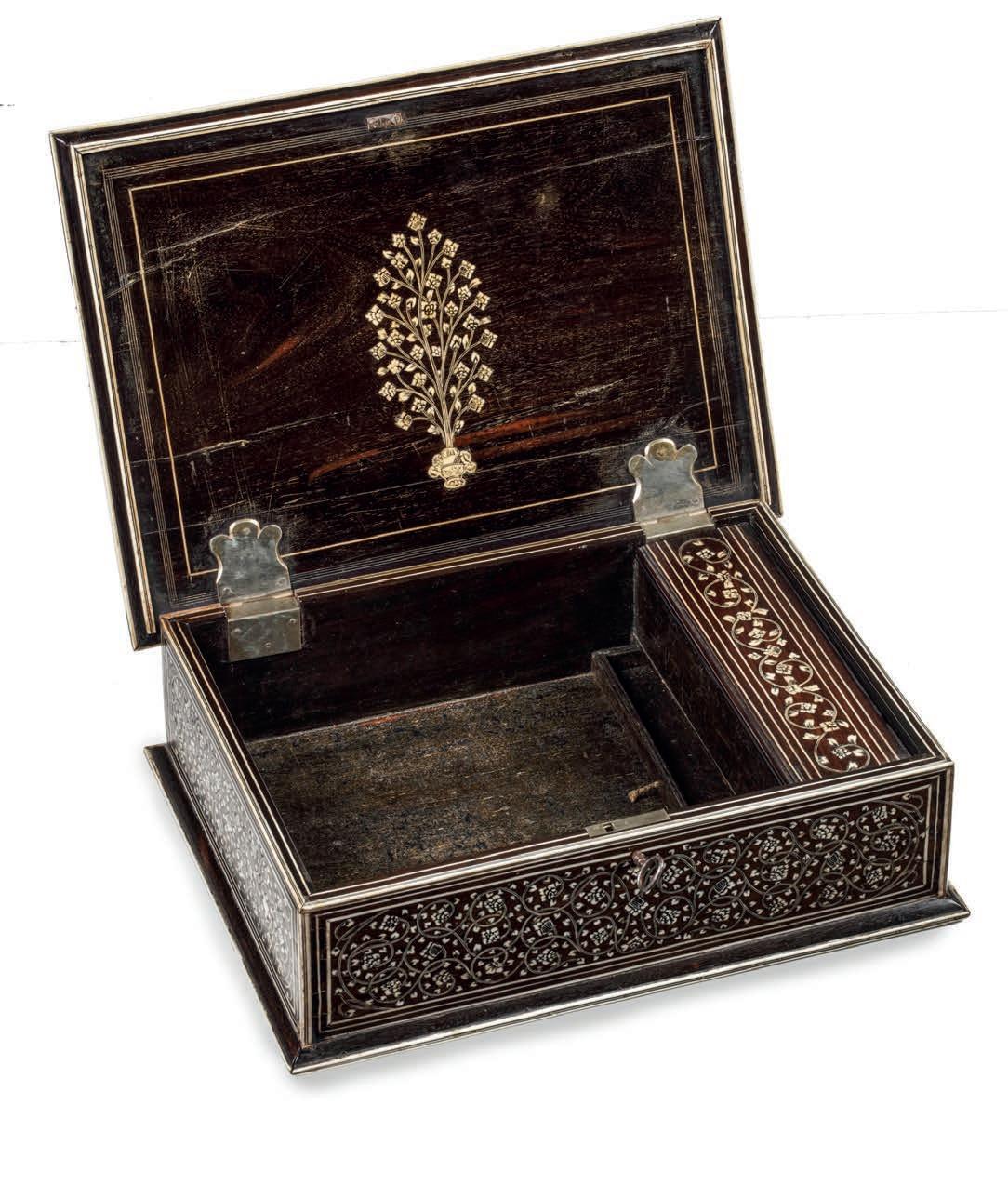

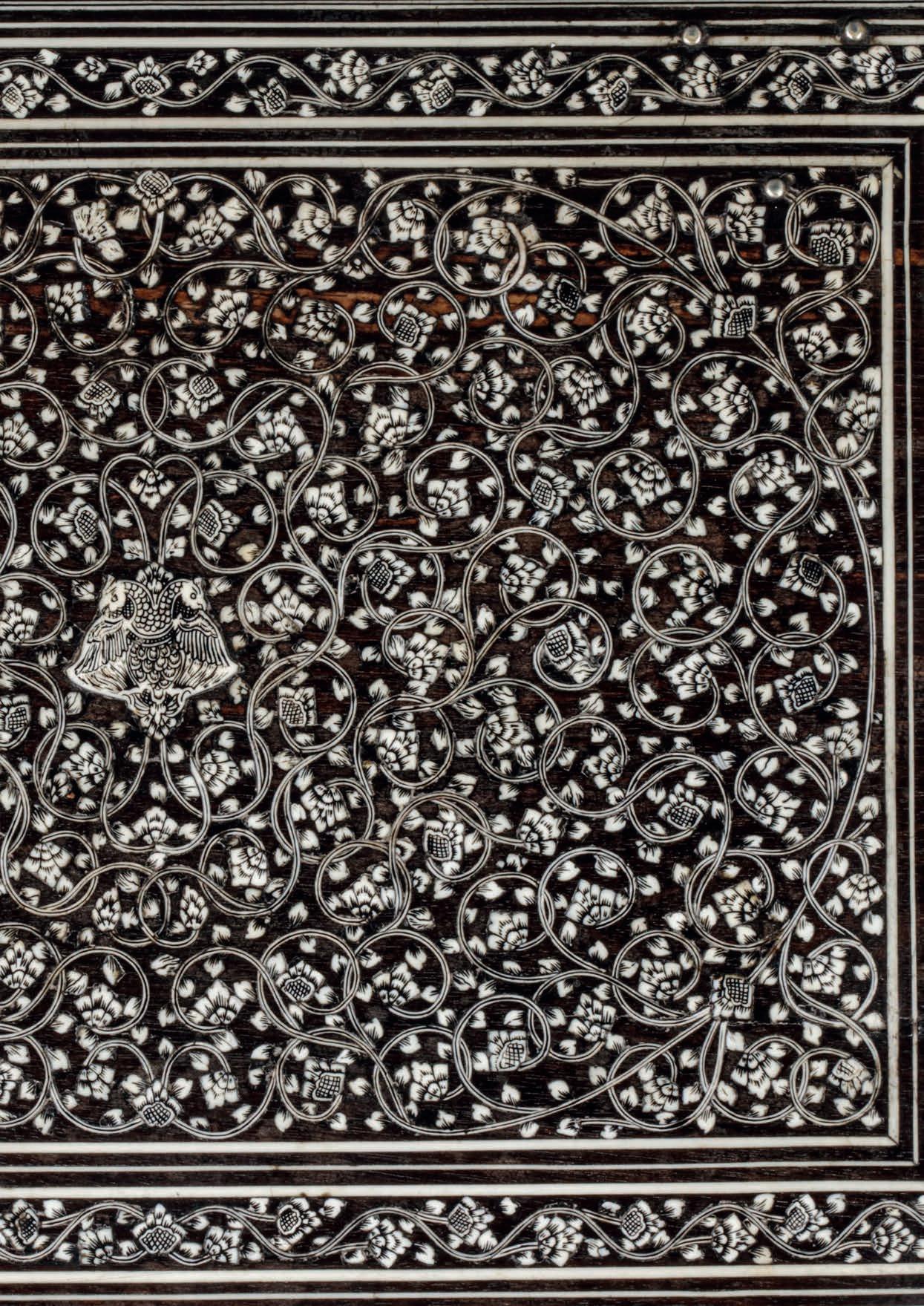

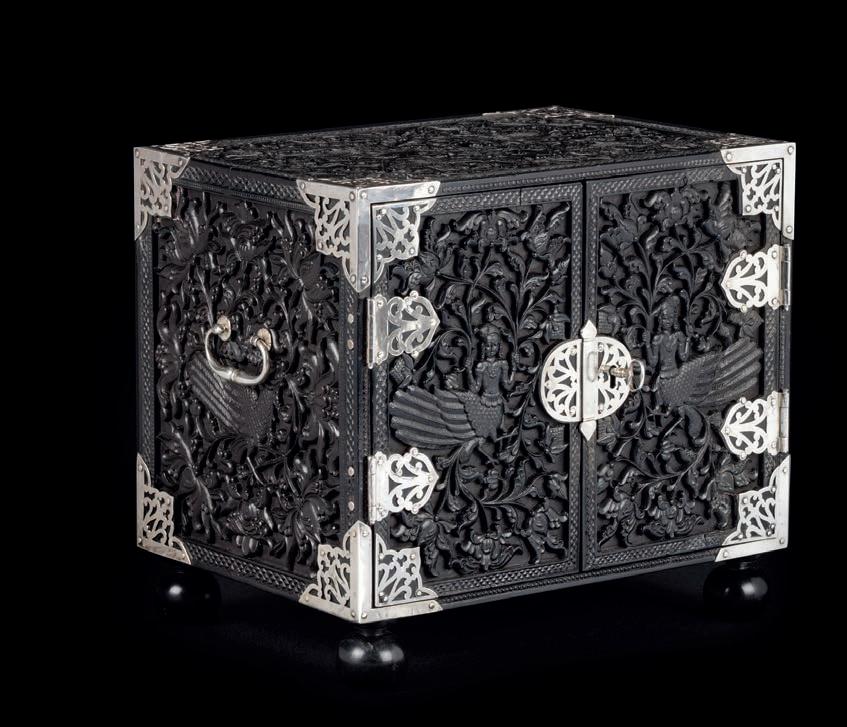

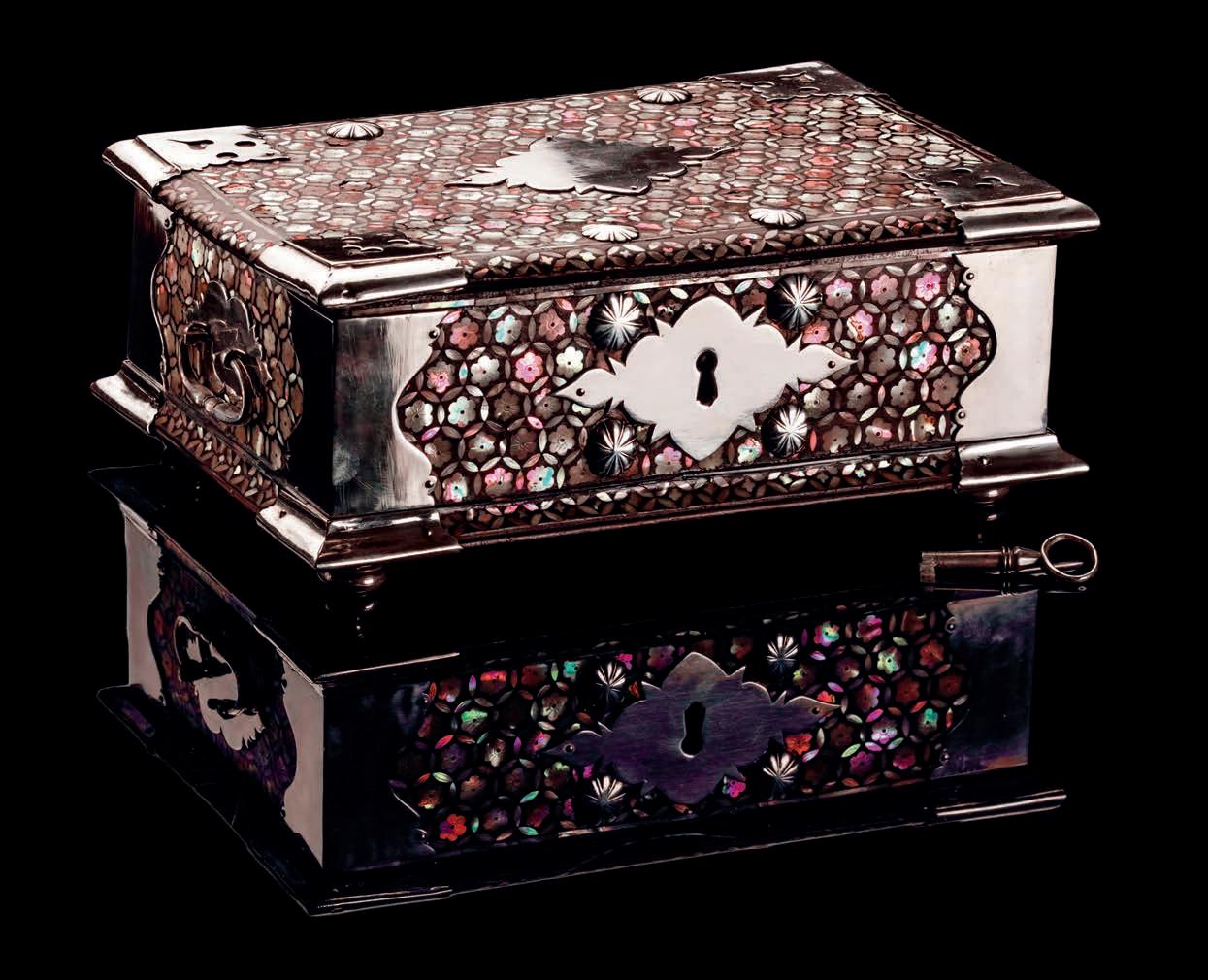

A fine ebony and pen-engraved mother-of-pearl and lacquer inlaid baleen collector’s cabinet by or attributed to Herman Doomer (1595-1650) and Jean Bellekin (c. 1597 - 1636)

Northern Netherlands, probably Amsterdam, circa 16301635

The overall ebony veneered cabinet on four bun feet, supporting ebony Termini in the form of a massive ebony three-horned faun with ionic capital, the front two diagonally placed, the back pair facing outwards. The two doors with yellow or gilt copper mounts reveal a magnificent interior of a long folly panel resembling three top drawers, a central painting on copper flanked by four small drawers, under which a long bottom drawer, all above a retractable games board. Each drawer, with a gold or gilt filigree puller, and both the interiors of the doors are decorated with a slat of uncoloured baleen overall inlaid with pen-engraved mother-of-pearl and silver-thread in ‘kwab’ or auricular design (for comparable design see: the fence of the choir in the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam after a design by Johannes Lutma, 1645).

The top panel at the front, which can be lifted when the top of the cabinet is open, reveals a secret drawer. The left part of the front shows a hunting bird of prey with its catch surrounded by foliage, sitting on rockwork which consists of lacquer finely inlaid with all sorts of sparkling (semi)-precious stones, metals, and other materials. The scene continues at the right panel with another bird of prey, but without a catch. Finally, the central panel shows two mother-of-pearl half-dragon half-bird figures or gryphons facing each other, fronted by a yellow or gilt copper auricular-style metalwork applique.

The centre has a pair of small drawers decorated with floral motifs on eac side, the top right drawer holding an original inkwell which is rare for the period, and a secret drawer at the back. The extended bottom drawer shows a deer hunting scene, with on the left the hunter and his dog and on the right panel, the deer chased by more dogs. The central panel shows a cartouche flanked by two birds or phoenixes. The slats on the interior of the main doors show flower sprays with tulips, lilies, ranunculus, and peonies. In the very centre of the cabinet is a painting depicting Judith and Holofernes, identified as from the Northern Netherlands and dated around 1630-1640 by Dr Fred G. Meijer. It falls to the front, revealing that the back of it is painted in a black-and-white checkered pattern, which is continued in ebony and marine ivory or bone on the bottom of the four-sided mirrored interior it reveals. The ceiling, suspended by four heavy gilt-metal columns, is inlaid with presumably palisander, African padouk, ebony, oak and marine ivory or bone. This complete interior comes out when a handle to the ceiling is pulled, revealing another identical, but now square, mirrored interior with three secret drawers at the back. The lid at the top of the cabinet, with three mirrored and inlaid baleen panels on the inside, opens to a compartment lined in red leather. The very top has a sliding panel, also revealing a possibly original red-leather lined interior.

Provenance: Private collection,

The attribution of this cabinet to Herman Doomer and Jean Bellekin was made by observing the high-quality carving and engravings and comparing the different attributed works of art by these artists in museums and literature. Several small cabinets and a few large armoires by Herman Doomer are known, among which are the famous cabinets in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. One of which was recently acquired by the museum. Prof. dr. Reinier Baarsen, now Curator Emeritus Decorative Arts and Furniture of that same museum, has argued, in his article Herman Doomer, Ebony Worker in Amsterdam in The Burlington Magazine (November 1996), that Doomer had a very successful career, as can be concluded from the portraits Doomer and his wife had painted by their friend Rembrandt van Rijn. However, Baarsen attributes only four cabinets and one picture frame to Doomer. Baarsen, in little more than one sentence, later eliminates a substantial group of highquality ebony furniture. An important change in the view of works by Doomer was a collector’s cabinet purchased by the Metropolitan Museum in New York (2011.181), which was acquired in 2011 and not known to Baarsen when he wrote his article in 1996. It is the first argument that Doomer created a larger number of these and probably other furniture forms. The finely engraved mother-of-pearl flowers on this cabinet are very similar - if not identical - to those on the large Rijksmuseum cabinets. The veneer on the inside was undoubtedly the final argument to attribute it to Doomer. Interestingly, some of the ripple mouldings and the engraved mother-of-pearl flowers and birds are nearly identical to our cabinet. Another cabinet, privately restored by Iskander Breebaart (senior restorer at the Rijksmuseum), can also almost certainly be attributed to the master himself because of the same reasons the Metropolitan cabinet was attributed. However, the ripple mouldings were completely renewed by him since they were replaced by plain veneer when (probably) a few fell off and got lost over time (leaving only four originals). (1 & 2)

Doomer’s ripple mouldings on cabinets are recognised by the wave ending in a straight line in the corners. This implies that these mouldings were made with the frame’s dimensions in mind, as seen in the Metropolitan cabinet and in the Rijksmuseum. Nevertheless, this is not an argument to not attribute other works to the master since the first Rijksmuseum cabinet shows neat ripple mouldings

to the bottom of the cabinet but not ending in a straight line in the corners. When one considers Doomer making custom mouldings is an argument, the cabinet present with perfect corner solutions should be by him. Similar corner solutions, but not ending in a straight line, can be found in one of the two cabinets by Doomer in the Boijmans-Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam (Div. M 90 b & M 17 a-d ). Remarkably, when studying 17th-century cabinets from the Northern Netherlands, Germany, and Antwerp (since they are often misattributed), Doomer is the only cabinetmaker who ever thought of an eye-pleasing solution

Doomer Armoire Collection Rijksmuseum (inv. no. BK-1975-81)for the corners. (3) Some other arguments for the attribution are the massive gilt brass columns in the interior, which are in other cabinets always made of wood, the fine openwork hinges, lockplate and applique in the ‘Lutma’ style, the excellent ebony veneer, finely carved figures, the door-hinges not hidden and pointing outwards, the drawers being made of solid African padouk (like in the Met-cabinet), the front termini that are placed diagonally to those at the back which is very Doomeresque and the cabinet itself in the base made of snakewood or another hardwood. Another strong argument for the attribution to Doomer is using unworked baleen. No other examples of the use of this material in works of art are known besides this cabinet. However, there is a significant exception: a picture frame in the Amsterdam Deutzenhofje regentenkamer, which was recently attributed to Doomer and will be published soon.

The Paerlemoersneyder Van Seters can attribute an ebony chessboard to Jean Bellekin by the signatures below three of the four portraits of Roman Emperors (Jean signs with IB and Jan with Jan Bellekin/ Belkien). In the chessboard, a small motherof-pearl shield is signed as well. Jean can be regarded as the ‘editor’ of the chessboard here. Still, the Guild would not let him create things in ebony, so an ebonist or cabinetmaker must have helped him. Van Seters argues that the maker must be Willem Albertse Deutgens, who made ebony frames for pearl shell-engraver Dirck van Rijswijck. His argument is Deutgens having “drie paerlemoeder ronties gesneden van Jan Belquin” in his estate when he died in 1659. Remarkably enough, in the estate of Herman Doomer, several mother-of-pearl engravings by Jean Bellekin were listed too. It is, therefore, possible that Doomer was the ebonist supplying the chessboard. The latter is further strengthened by the fact that the ebony cabinet in the Rijksmuseum, which has proven to be by Doomer but not signed by him, has mother-of-pearl engraved inlays and signed by Bellekin. A closer look at the inlays on the chessboard and those of the kunstkabinet presented here reveal that the mother-of-pearl figural inlays are nearly identical to each other, especially the hunter, dog, and deer. One cannot conclude differently that the motherof-pearl engravings on this cabinet are by Jean Bellekin. The engraved plaques on the Metropolitan cabinet are identical to those of our cabinet but, in these cases, depict birds and flowers. (4)

When observing the different carvings on one piece of furniture presumed to be by Doomer

or on different ones, the quality of the engraving fluctuates a lot. However, for any artist, it is easier to work on a grand scale than on a small miniature scale (perhaps a reason why our termini figures are less detailed than the almost 30 cm figures of the Rijksmuseum cabinets). On the chessboard, the portraits of Roman emperors are highly sophisticated, while the smaller engravings of animals are beautiful but could be better. In the past, it was presented as a fact that Doomer operated on his own, and Bellekin did so too. Perhaps they did so in the large, magnificent pieces as those in the Rijksmuseum.

Nevertheless, this would make these two workmen exceptional in Amsterdam since all craftsmen had apprentices working in their workshops. Rembrandt portrayed Doomer and his wife, and one cannot presume him to be so successful while he worked on his own and finished merely a few pieces a year. It is perfectly possible that some of the more ‘generic’ works of art (although superb) were made under the supervision of the meester Kistemaker, or in Bellekin’s case meester paerlemoersneyder

The cabinet presented here is unusual in many aspects. First, the imagery on the panels and the painting are rarely seen on such table cabinets. The hunting scenes on the drawers are an unconventional choice - especially in engraved mother-of-pearl. The immediate question one asks is why the vases with flowers on the doors were not continued in a floral motif on the drawers. It is possibly the first argument that the decoration was not randomly picked but might have a meaning.

Using the story of Judith and Holofernes as a central painting in a kunstkabinet is highly unusual, too, especially in combination with flowers and hunting scenes rather than with other biblical stories. Since the picture is identified as from the northern Netherlands, it is also remarkable that the scene was chosen. Judith slaying Holofernes in the first half of the 17th century symbolised the Catholic fight against the Protestants and Ottomans. Judith refers to the pious, and Holofernes, the barbaric Assyrian, to the Protestants and Turks. Could the owner of the cabinet have (secretly) been a Catholic? (5)

Finally, the most remarkable feature of this cabinet: is the use of uncoloured whale baleen. The use of (whale) tooth marine ivory or bone instead of elephant ivory, which was more common at the time and must be pointed out, especially in combination with the unworked baleen. Ivory was used in high-end furniture such as cabinets by Herman Doomer (see: Rijksmuseum BK-1975-81) and Willem de Rots (see: Rijksmuseum BK-2005-19), under which this cabinet can be placed, but also in furniture produced in larger quantities such as the Antwerp kunstkabinetjes.

Now if there is something all art historical research tells us, it is that whenever there is something out of the ordinary in a decoration scheme, it was done on purpose by the artist or has a meaning for the patron. Could the cabinet have something to do with whale hunting? After all, the hunting scenes are placed directly on baleen. The latter was clearly to be identified as such by the spectator and not blackened to resemble ebony. Whale hunting, or the whaling industry, was prominent in Dutch society of the 17th century and

even was an essential part of the economy. However, what could be the connection between Judith, Holofernes, and whaling?

It could be that the person ordering this cabinet was a Catholic. However, since he was free to be Catholic in Amsterdam, why would he criticise the city where he gathered his fortune? Could it be possible that a Catholic, who certainly knew the meaning of the story of Judith was a symbol of the fight against Protestantism through the counterreformation, commissioned this depiction on his cabinet since he fought a Holofernes or a Goliath for all that matters? To answer that question, one must investigate the history of the whaling industry of the Netherlands, to be more precise the Noordsche Compagnie.

The Noordsche or Northern Company was a Dutch whaling trade cartel, founded by several cities in the Netherlands in 1614 and operating until 1642. Soon after its founding, it became entangled in territorial conflicts with England, Denmark, France, and other groups within the Netherlands. However, vast fortunes were made in the industry, with prominent wealthy figures such as the founders Nicquet and Hinlopen. The company was dissolved in 1642. The company had started receiving intense competition from Dutch interlopers and Danish whalers. Whaling was slowly privatised, and private traders finally pushed the cartel aside.

This could be a battle between David, Judith, Goliath, and Holofernes. The young nouveau riche battled the old wealthy, established merchants. It certainly would not be the first time that a young wealthy Amsterdam merchant would show off his newly gathered fortunes in the form of a life-size portrait or exuberant furniture. However, who could have been the Catholic nouveau merchant who became riche in the whaling industry?

On the other side, the curious cabinet could be made exactly what it was intended for: keeping curiosities. It would be filled with rare objects of artificial and natural origins. The use of baleen, mother-of-pearl, hunting (for rare things) and a rare image of Judith and Holofernes would comply with the use of it.

Literature:

1) Reinier Baarsen, “Herman Doomer, Ebony Worker in Amsterdam” in: The Burlington Magazine, November 1996, Vol. 138, No. 1124, pp. 739- 749

(2) The Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art, “Recent Acquisitions, A Selection: 2010–2012” in: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Fall 2012, v. 70, no. 2 (ill.)

(3) W.H. van Seters, “Oud-Nederlandse Parelmoerkunst: Het werk van de leden der familie Belquin, parelmoergraveurs en schilders in de 17eeeuw, in: Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ), 1958, Vol. 9, pp. 173-238

(4) Iskander Breebaart & Gert van Gergen,“Pressed baleen and fan-shaped ripple mouldings by Herman Doomer”in: Proceedings 11th International Symposium on Wood and Furniture Conservation, Amsterdam, 9-10 November 2012, pp. 62-74

(5)(R. WardBissell, “Artemisia Gentileschi-A New Documented Chronology” in:The Art Bulletin.50, 1968, pp. 153-168

“Departure of the Pilgrim Fathers from to join the ‘Speedwell’, Delftshaven, July 1620”

Oil on panel (single sheet of oak), H. 44.7 x W. 58.1 cm

Provenance:

The Duke of Marlborough Collection, Blenheim Palace (according to a label on the reverse); Collection of the Anglo-American painter George Henry Boughton (1833-1905), London/New York, by 1895; (presumably) by descent to his wife Katherine Louise Boughton née Cullen (18451919); Collection of the ambassador James John Van Alen (1848-1923), Newport, Rhode Island; by descent to his wife Margaret Louise Van Alen Brugiére née Post (1876-1969); her deceased sale, Christie’s London, 5 December 1969, lot 61 (as Flemish School 17th century); Bought by the consortium of dealers Herbert Terry-Engell, London (advertised in Apollo, May 1970), Hermann Abels, Cologne, and Evert Douwes, Amsterdam (as by Adam van Breen and as depicting the Pilgrim Fathers with the Mayflower); Purchased from the latter, 26 October 1972, by a Swiss private collector

Literature: - Not in the Blenheim Palace collection catalogue of 1862 (by George Scharf)

- Harper’s Weekly, Vol. XXXIX, no. 1994 (March 9, 1895), p. 228 (ill.)

- Joseph Dillaway Sawyer and William Elliot Griffis, History of the Pilgrims and Puritans. Their ancestry and descendants, basis of Americanization, New York 1922, ill. p. 248 (as the Departure of the Speedwell from Delfshaven)

- F. Ziner, The Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony, New York 1961, p. 53

- L.W. Cowie, The Pilgrim Fathers, London 1970, pp. 50-51 (as the Departure of the Speedwell from Delfshaven), pp. 50-51 & cover (ill.)

- Nick Bunker, Making haste from Babylon. The Mayflower Pilgrims and Their World. A new History, New York, 2010, cover (ill.)

- Laura Hamilton Waxman, Why did the Pilgrims come to the New World? And other Questions about the Plymouth Colony, Minneapolis, 2010, p. 15 (ill.)

- Otto Nelemans, Lost in interpretation. De zoektocht naar een verloren titel van een schilderij van Adam Willaerts (1577-1664), Utrecht, 2020, p. 17, fig. 19 (as by Adam van Breen)

Exhibited:

- Terry-Engell Gallery, London, Twenty-Five important Dutch and Flemish Master Paintings, no. 2 (as by Adam van Breen and with ‘illegible signature)

- Abels Gemälde-Galerie, Cologne, Niederländische Gemälde von 15401700, 15 April – 31 May 1972, ill. cat. p. 7 (as by Adam van Breen and reported as being signed)

The present picture is part of the collective memory of all those interested in the early history of the United States, as it is reproduced in many publications dealing with the Pilgrim Fathers and their exodus to the New World. In 1608, a group of about hundred deeply religious Calvinists, refusing to subordinate themselves to the ordinance of the Anglican church, set sail from Nottinghamshire to escape persecution under James I. Their leader, the elderman William Brewster, chose to set course to the Dutch Republic, known for its religious tolerance. After a short stay in Amsterdam they settled in the city of Leiden, where they moved into some small houses, also known as the Wevershuisjes, close to the Pieterskerk church. Even though they were allowed to have their own sermons and to live life according to their principals, the group were weighed down by poor circumstances. Besides, their leaders feared assimilation with lesser orthodox puritans within the Leiden community.

From 1617 the idea emerged to emigrate to the ‘New World’. Here they would eventually start a society in compliance with their strict interpretation of the Bible. The

ship ‘Speedwell’ was equipped to transport a selection of members from the group, and the departure took place from Delfshaven as soon as July 1620. The painting shows the ship and its passengers in advance of their long journey, probably at the very moment they take off for a Day of Solemn Humiliation, existing out of fasting and Bible lecture. In all their actions, the colonists coordinated with God to be assured of His approval.

The intention for the ‘Speedwell’ had been to join the ship ‘Mayflower’ off the coast of Southampton, from where the two ships with pilgrims would continue in convoy. Unfortunately, the ‘Speedwell’ proved unfit for the transatlantic journey as a leak had occurred. Therefore, the crew of the Dutch ship went on board of the ‘Mayflower’. After some detours the puritans arrived in Massachusetts where they established Plymouth Colony. At the very beginning the inexperienced settlers met with the friendliness of the local native Americans, who supported them in their basic needs.

Until this day the story of the Pilgrim Fathers is a central theme in the history and culture of the United Sates. It has been calculated that there may be as many as 35 million living descendants of the Pilgrims worldwide. The settlers in Plymouth Colony are credited with organizing the first Thanksgiving Day, which would have derived from the October 3rd-celebrations in Leiden, honouring the Relief of that city.

A citizen of Leiden and later bailiff of the neighbouring village of Rijnsburg, the painter Cornelis Liefrinck lived in the Mandemakerssteeg, not far from the Pieterskerk. He was the son of a painter-cartographer from Antwerp, Hans Liefrinck II, a specialist in the maritime genre, who must have been Adam Willaerts master during the latter’s sojourn in Leiden. As Otto Nelemans has observed, the figure of the markententser walking a dog in the left foreground of our picture, also appears in Willaerts’ painting of ‘The Departure of the Pilgrim Fathers from Delfshaven’ in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (access.no. 2020.408).

Cornelis Liefrinck, in turn, may be credited with being Willem van de Velde the Elder’s master. The Van de Velde family inhabited a house in the very same alley as the Liefrinck’s did. Apart from that, in 1621, the young Willem and his father joined their neighbour as a representative of the city’s militia on a mission to Grave in Brabant. The operation is the subject of a series of three etchings by Liefrinck junior, dating from 1622. The idiosyncratic rendering of the masts in one of these prints is remarkably equal to our picture. The staffage - most particularly the dog - compares well to Liefrinck’s signed picture in the Lakenhal, Leiden (inv.no. S 3533).

A shisham wood (Dalbergia sissoo) and American walnut ( Juglans nigra) coffer with iron and brass mounts, previously owned by settler Anneken Jans Bogardus (1604/1605-1663)

North America, New Amsterdam (New York), circa 1633, the lock inscribed ANNEKEN JANS B A1633

The slightly trapezoid-shaped sisham wood coffer with American walnut carved escutcheon, iron hinges and handles, a Dutch mechanism lock, in which 17th-century Swedish copper was used. Inside, at the top left side of the interior, the typical small-lidded compartment, found in practically all VOC chests. The present compartment, a late 19th/early 20th-century replacement of the original one, is made of American oak (Quercus alba) with northern pitch pine (Tsuga canadensis) lid.

The lock bears the inscription ‘Anneken Jans. B A1633.’ B probably stands for Beverwijck (present-day Albany), where Anneken Jans lived A(nno) 1633.

H. 49.2 x W. 112 x D. 46.8 cm

Provenance:

Mr. & Ms. Van Hanxleden Houwert Van Silfhout

Van Hanxleden Houwert was a wealthy dealer in colonial goods in the Netherlands in the late 19th century.

The chest, because of its style and the wood used, probably is from the Indian Malabar Coast or Persia/Shiraz, before 1633. Originally the chest probably had an additional central hinge (traces to be found inside the lid) ending in a hasp hanging over a metal backplate with a protruding ring (traces of which can be seen inside the chest), secured by a padlock. This was the usual way chests from the Malabar Coast were locked. The Dutch always replaced the padlock by an internal Dutch mechanism chest lock.

It has a wooden lockplate carved in American walnut (Juglans nigra) in the New Netherlands in the auricular or ‘kwab’ style, popular at the time. A xylological analysis of the wood, provided by the CIRAM institute, of the 17thcentury lockplate has shown it is American walnut (Juglans nigra).

All parts of the brass lock, analysed by the Conservation Laboratories of the Rijksmuseum with stereomicroscope and XRF-analysis, proved to have originated from the Falun mine in Sweden, which dominated the European copper market during the mid-17th century. Brass based on Swedish copper also made its way to the New World and was found among the scrap discovered during an excavation of an early 17th-century site in Jamestown (Carter C. Hudgins, ‘Articles of Exchange or Ingredients of New World Metallurgy’ in: Early American Studies 3, no. 1, 2005, pp. 32-64).

The engraving of the text first set up with a scriber, clearly shows signs of wear predating some repairs to the lock, and according to researchers Ellen van Bork, Tamar Davidowitz and Arie Pappot of the Conservation Laboratorium of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam seem to be old and authentic.

Anneken Jans, also known as Anneken Jans-Bogardus, was born 1604/1605 in Norway, Fleckerøy, Vest Agder, daughter of Jan (Roelofsz. ?) and Trijn Jonas, who later was to become the first midwife for the WIC, the Dutch West India Company, in New Amsterdam. At a young age Anneken and her family moved to Amsterdam. Anneken married Roeloff Jansz (1601/1602-1637) on April 18th, 1623, a Norwegian seaman. The couple certainly were not afraid to take risks. As one of the very first Dutch settlers Anneken and Roeloff in 1630 sailed to Nieuw Amsterdam with a contract to work for three years for the wealthy Amsterdam jewellery merchant Kiliaen Rensselaer, a governor of the West India Company in Amsterdam, who was granted by the WIC, as a patroonship, vast lands encompassing all of present-day Albany, Rensselaer counties, and part of Columbia and Greene counties. On May 24th, 1630, Anneken, Roeloff, their three daughters, together with Anneken’s mother and sister, arrived at Fort Orange and settled in the small village of Beverwijck. Roeloff was paid 72 guilders a year as a farmer of the Laets Burg Farm along the Hudson River near Normanskill Creek, and was appointed schepen, alderman, of Beverwijck. In the meantime, Anneken and her sister and mother set up a (illegal) retail business. The couple had two more daughters and a son, and the family interacted daily with local Native Americans. Incidentally, their first daughter, Sara, later became a translator for the New Netherlands director-general, Peter Stuyvesant, in negotiations with the local tribes.

On Sara Roelofse, the daughter of Anneke, here called Kierstede, was written by Van Rensselaer: “… the Dutch women had become well acquainted with the wild people who surrounded them and were on friendly terms with them. Madame Kierstede was particularly kind to them, and as she spoke their language fluently, she was a great favourite among them, and it was owing to her encouragement that the savages ventured within the city walls to barter their wares. For their better accommodation and protection, Madame Kierstede had a large shed erected in her backyard, and under its shelter, there was always a number of squaws who came and went as if in their own village, and plied their industries of basket and broom-making, stringing wampum and sewant, and spinning after their primitive mode; and on market-days, they were able to dispose of their products, protected by their benefactress, Madame Kierstede (Van Rensselaer 1898 :26).”

Whether Anneke Jans had enslaved people is unknown, but her daughter certainly did.

Sara’s will, dated July 1692 and written in Dutch, has many points of interest. After the preliminary formalities, she stated:

“Now I will before anything else to my daughter Blandina, of this city, a negro boy , Hans. To my son Luycas Kierstede, my Indian, named Ande. To my daughter Catharine Kierstede, a negress, named Susannah. To my son in-law, Jacobus Kip, husband of my said daughter Catharine, my negro, Sarah, in consideration of great trouble in settling the accounts of my late husband, Cornelius Van Borsum,

‘The Anneke Jans Chest.’

in Esopus and elsewhere. To my son Jochem Kierstede, a little negro, called Maria, during his life, and then to Sarah, the eldest daughter of my daughter Rachel Kierstede by her husband, Ytie Kierstede. To my son Johanes Kierstede, a negro boy, Peter. I leave to my daughter Anna Van Borsum, by my former husband, Cornelius Van Borsum, on account of her simplicity, my small house and kitchen, and lot situate in this city, between the land of Jacob Marits and my bake house, with this express condition, that she shall not be permitted to dispose of the same by will or otherwise, but to be hers for life and then to the heirs mentioned in this will.”

New Amsterdam probably couldn’t have become so successful without enslaved people, and Anneke, as well as Sarah, needed the help of enslaved people. However, the burials of Europeans and enslaved African people in the Amsterdam colony in Delaware showed that both had as much stress on bones and joints that probably the European worked as hard as the African while building the society. Which, of course, does not change the view on slavery and owning one another.

However, the farm of Anneke Jans wasn’t very successful at first, and in 1634 the family moved to Manhattan and worked in the Dutch West Indian Company’s Bouwerie, or farm, in the section of Manhattan now known as ‘The Bowery.’ In 1637 the industrious Roeloff was given a grant for a 62-acre farm of his own near the site where later the World Trade Center would be standing. Here he built a small house on the farm for his mother-in-law, the colony’s midwife. That same year Roeloff suddenly died. Anneken and Roeloff had five daughters and one son, all baptized Lutheran. Anneken, now with six children, no money and apparently in debt to Rensselaer, was acquitted her debts by Rensselaer, and continued to work her own farm. A year later, 1638, Anneken married reverend Everhardus Bogardus (ca. 1607-1647), the second ‘dominee’ to be sent by the West India Company to the New Netherlands. Bogardus was a well-read Dutch Re-formed clergyman, with whom Anneke had another four sons (one of their grandsons, Everardus Bogardus (1675-ca. 1725), was to become a famous Dutch New York silversmith). The couple lived on Anneken’s 62-acre farm which came to be known as ‘Dominee’s Bouwerie’. Reverend Bogardus was orthodox, considering himself the guardian of the public morals, even though he himself had quite an alcohol problem. He had frequent quarrels with the New Netherlands magistrates often denouncing them from the pulpit. They didn’t like that, and Bogardus was charged with drunkenness, meddling with other men’s affairs, and using bad language. In September 1647, leaving behind his wife Anneken and his four sons, Bogardus sailed on the ‘Princes’ for Amsterdam to defend himself from the charges brought against him. He drowned when the ‘Princes’ was wrecked on September 29, 1647, off the coast of Wales. Anneken, widowed for the second time at the age of 42, had nine children to support and still was cash-poor but land-rich, having three farms; in Beverwijck (Albany), Manhattan and an 82-acre farm on Long Island, called ‘Dominee’s Hoek’, she inherited from her husband dominee Bogardus. She sold the Long Island farm and moved back to Beverwijck (Albany), where she had a house built on land adjacent to the property owned by her son from her first marriage. As

her children married and moved out, she gave each of them a bed and a cow as a wedding present.

In 1659 the widow Anneken Bogardus had to appear in court because she had shown her ankles in public! She was saved by a friend who declared that, when Anneken had to walk through the mud, she had lifted her skirts only to keep them clean. Fortunately, she was acquitted.

Anneken died in 1663 after living another sixteen years in Beverwijck. Her will stipulated that the estate be divided equally among her seven surviving children. The children sold her Albany house to Dirk Wessels ten Broeck for the substantial sum of 1.000 guilders. After Colonel Richard Nicolls had taken possession of New Amsterdam in 1664 for the Brits, all property-holders were required to obtain new titles for their lands. Anneken’s heirs secured a new patent for the farm of 62 acres on Manhattan from Governor Nicolls on March 27, 1667. On March 1671, the farm was sold to Governor Lovelace for a ‘valuable consideration’. All of Anneken’s heirs signed the deed of transfer, except the widow and child of Cornelius Bogardus, one of Anneken’s sons who had died in 1666. That omission was to cause a lot of subsequent legal problems. In 1674 the Duke of York (the later King James I) confiscated ‘Dominee’s Bowery’ and it was turned over to the British

crown. In 1705 Queen Anne granted the farm to the Trinity Church. Descendants of Cornelius Bogardus (whose wife and son had not signed the deed) later claimed parts of the Trinity Church’s farm, because their ancestors hadn’t agreed to the sale. This resulted in the most famous and protracted lawsuit over Manhattan landownership that dragged on well into the 20th century. In the end all ended in the Church’s favour.

The Albany Institute of History and Art has exhibited another chest, brought to New Amsterdam in 1633 by dominee Bogardus as it was impossible to travel without a chest in those days. However, the whereabouts and the authenticity of this chest are unknown.

West Indian Company vessels arriving in New Amsterdam were laden with goods from Holland, such as building materials (bricks and tiles), and all kinds of household goods such as furniture, textiles from East India, carpets from Turkey, oriental ceramics, Dutch Delftware, silver, tin, and copper objects. Possibly the present coffer arrived with a Dutch ship in 1633 and was bought then by Anneken Jans, amongst other goods for her private retail business. She had her name inscribed on the lock, presumably because she intended to keep the chest to store her own belongings.

Anneken Jans-Bogardus is now famous as the almost mythical ancestress of the Dutch community in the United States. Six of her children had numerous offspring, forming a ‘Nederlandse’, anti-British, anti-royalist, Dutch Reformed community. Anneken became the object of an unbridled creation of legends, making her even a daughter of William of Orange, the Vader des Vaderlands, and leader of the Dutch in their revolt against Spain. These legends still form a strong bond for the multitude of descendants of Anneken Jans. Bogardus in the United States.

Presumed portrait of Anneken Jans, 17th century Private collection, USA

Presumed portrait of Anneken Jans, 17th century Private collection, USA

13.

A Peruvian silver plaque with hammered decoration of ‘ The Marriage of Beatriz

Clara Coya and Martin de Loyola’ Peru, 1st half 17th century

Depicting the famous couple surrounded by a feline, dog, monkey, parrot, flowers, child and a servant holding an umbrella, the plaque trapezeshaped.

Royal Governor Martin de Loyola and Inca

Princess Beatriz Coya were assumed to be the first married couple in Peru between two persons, each from a different royal lineage, one of the Conqueror and the other of the Conquered. The couple can be identified by a set of very distinguishable iconography in the art history of South America.

They are the South American equivalent of Romeo and Juliette as their marriage was forbidden, but one night they met and married in secrecy. However, the Catholic church embraced the story at the end of the 17th century to gain more followers among the Peruvian indigenous.

Large paintings depicting the legend were hung in churches, and the marriage story became common knowledge. The silver depiction presented here is possibly the earliest depiction of the story. It is part of wedding attire, worn as a breastplate by the shaman or close relatives of

the man and woman.

Mr Ramón Mujica Pinilla, Curator to the Gold Museum Peru and member of the National Academy of History of Peru, has seen the plaque and determined it to be from the first half of the 17th century.

The Dutch institute for Gold and Silver in Gouda has analysed silver in four places. First, they state that the alloy of the plaque is very high in silver and has a small percentage of copper, tin and gold. However consistent in the alloy, the percentages of it are not consistent all over the plaque, which points out that the plaque probably was made from scrap silver that could not be heated enough for a complete mix. The technique and absence of other metals in the alloy point towards the given date. The fourth analysis is that of the restoration flap to the back, which has a pure alloy as well, and the inspection of it by Mr Mujica proved it is an old restoration.

Provenance:

- Collected by a KLM (Royal Dutch Airways) pilot in the 1970s - Amsterdam antiques trade

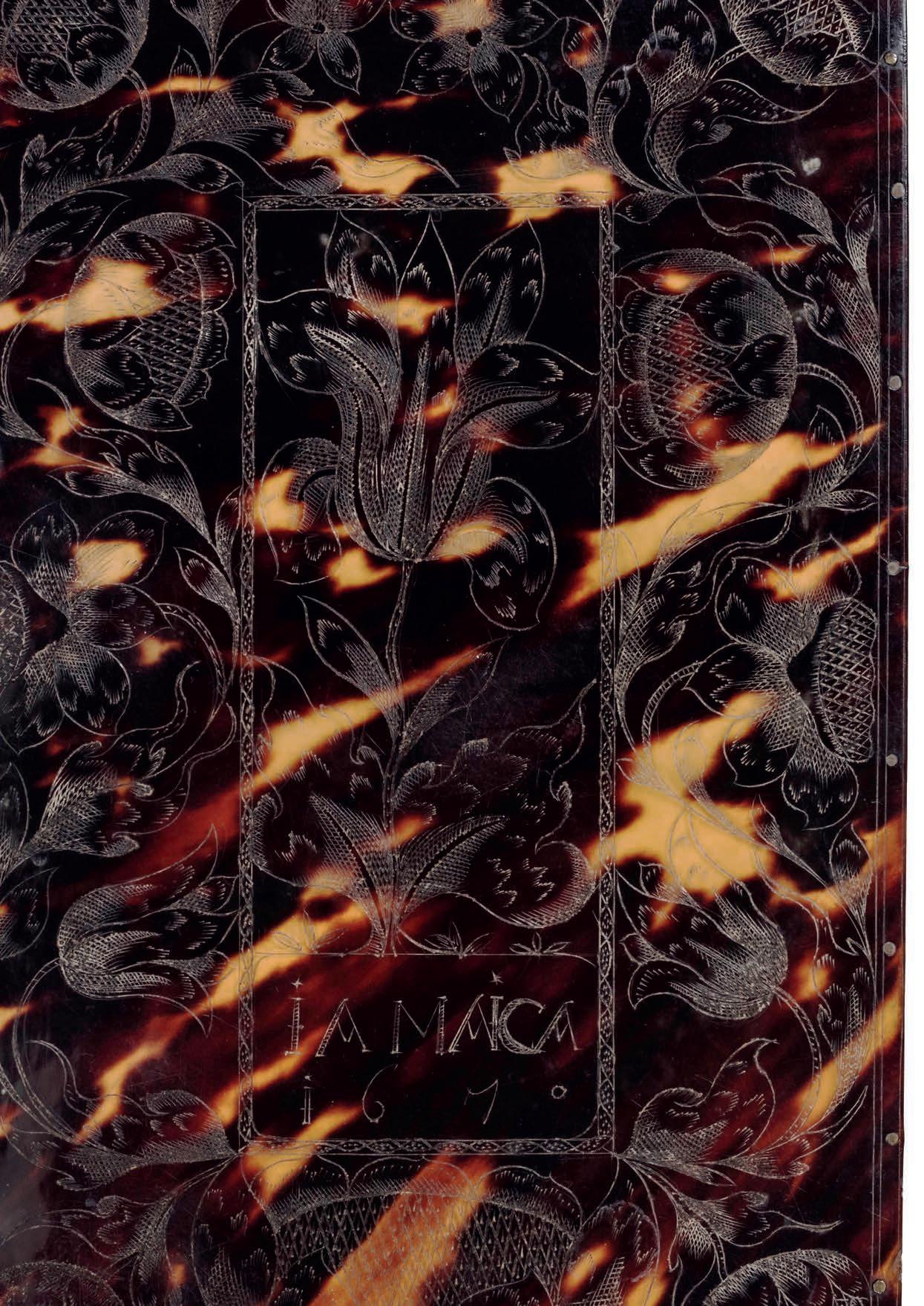

14. A Jamaican engraved tortoiseshell comb-case with two combs

Former British Jamaica, circa 1670, inscribed and dated ‘Sarah Henly, JAMAICA 1670’, probably by Paul Bennett of Port Royal

The case of rectangular form, one side with a central panel depicting an indigenous tropical flower, beneath the wording ‘Sarah Henly’ within an undulating indigenous flower border, the reverse with a similar panel with the wording ‘JAMAICA 1670’ within a matching border. The case with an original silver clasp encasing one double-sided fine comb and one singlesided coarse comb, each engraved with various indigenous flower heads and scrolling foliate motifs.

H. 19.5 x W. 12.5 x D. 0.6 cm

Provenance:

After England’s conquest of Jamaica from the Spanish colonist in 1655, Port Royal developed into a large city and the thriving commercial centre of (the then archipelago) Jamaica. However, this all ended when a massive earthquake devastated the city and swept two thirds it under the sea in 1692. Combs made of various materials such as ivory, wood and horn, were quite common in medieval and early modern England and a well-known status symbol. These tortoiseshell combs are objects created from familiar forms to reflect new cultural structures in a quickly changing society.

Taken home after the ‘colonial adventure’ as mementoes of Jamaica, they proved their owner’s worldliness and newly gathered fortunes by being a perfect balance between the ‘exotic’ and the familiar, thus being a tool to obtain a higher social status upon arrival. The narrow-toothed comb probably was intended for extracting lice and the wide-toothed comb for fixing wigs but was perhaps not to be used, but to be placed in a kunstkammer or some room alike.

The Institute of Jamaica in London has eleven tortoiseshell combs, one large box with combs and one powder box. The first comb for the Institute of Jamaica in London was purchased by members of the West India Committee in 1923. It was described by H.M.Cundall in the West India Committee Circular (1923) as “probably one of the earliest art objects made in the British West Indies displaying European influence.” The tortoiseshell works in the Jamaica Institute’s collection are thought to be from the hands of two craftsmen working in Port Royal between circa 1671-1684 and 1688- 1692, respectively. The present case with combs, dated 1670, is the earliest recorded, dated example and is linked to the first group. Philip Hart, in his article Tortoiseshell Comb Cases, for the Jamaica Journal (November 1983), reveals that recent research found an

Englishman called Paul Bennett, in Port Royal, listed in 1673 as a comb maker. Therefore it’s likely that Bennett was the maker of this first group and an apprentice or assistant of him was the maker of the second group. Other works supposedly by Paul Bennett include the Sir Cuthbert Grundly comb-case, dated 1672, a round powder box lid and comb case in a private U.S. collection, dated 1677, and the ‘Lady Smith’ casket, which is considered the artist’s masterpiece.

The Hawksbill Turtle’s shell was a widely used material and can be regarded as plastic avant la lettre, having the ability to bend when heated. These turtles were common in the oceans until hunted down almost to extinction, only to be (successfully) protected in the 20th century. This set is a beautiful but poignant expression of a painful cultural moment. Bought with wealth generated by enslaved Africans, it embodies the English appreciation of Jamaica’s glorious natural history and the simultaneous savaging of it.

For a comparable circular powder box with a domed lid inlaid with a few pieces of mother-of-pearl, three silver mouldings around the box and the lid, and engravings of indigenous flower heads and scrolling foliate motifs, see: Uit Verre Streken, June 2012, no. 4.

Literature: Philip Hart, ‘Tortoiseshell Comb Cases: a 17th century Jamaican Craft’ in: Jamaica Journal, the quarterly journal of the Institute of Jamaica, Vol 16, No 3 (August 1983)

15.

An Amazon indigenous wamara wood Macana war-club Southern-Guyana or Northern Brazil, Wapitxana group of the Aruak peoples, 18th century, possibly earlier H. 43 cm

The deep patina of the club present, and the residue on the part where it was held, attest to its great age. This unusually large Macana is decorated with several incised whitened anthropomorphic and human figures, a decoration only found on one other documented club in the British Museum (inv.no. Am1910,-.456), which is illustrated in: Hjalmar Stolpe, Amazon Indian designs from Brazilian and Guianan wood carvings, New York, Dover Publ., 1974. Among the earliest objects to reach Europe in the 17th century from Guyana are ‘four wooden clubs and five hammocks’ that entered the Tradescant collection and are now in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

An early description of these war-clubs in Dutch Guyana, based on observations made from the years 1772 to 1777, is stated in the famous book Narrative of a five year expedition against the revolted Negroes of Surinam in Guiana on the Wild Coast of South America from the year 1772 to 1777 by the author Captain John Gabriël Stedman (1744-1797),: “I must not forget that every Indian carries a club, which they call apootoo, for their defence. These clubs are made of the heaviest wood in the forest; they are about eighteen inches long, flat at both ends, and square, but heavier at one end than the other.”

Literature:

Hjalmar Stolpe, Amazon Indian designs from Brazilian and Guianan wood carvings, New York, Dover Publ., 1974

We are grateful to our dear friend Mr. Peter van Drumpt for his assistance in writing this catalogue entry.

16.

A Rikbaktsa Amazon indigenous feather and hair headdress Brazil, Mato Grosso, Rio Juruena & Rio Sangue, collected in the 1950s-1960s

H. 65 cm (incl. stand)

The headband is made of cotton fabric, densely covered with small tufts of feathers that were incorporated during weaving, with 21 long threads with continuing tufts and feather bundles at the ends. On the band, the tufts of feathers are placed in a banded arrangement, with black Hokko bird or Great curassow (Crax rubra) feathers alternated with feathers of the Scarlet macaw (Ara macao) and the Ariel toucan (Ramphastos ariel). Placed below the 21 threads are 29 long Scarlet macaw and Yellow-breasted blue macaw (Ara ararauna) tail feathers, each with a bunch of colourful feathers tied to the tips. Locks of black human hair are suspended from the sides of the band at the ears of the wearer.

Provenance:

Collection of an anthropologist, Ireland (collected in the 1950s-1960s)

Literature:

- Gisela Völger & Ursula Dyckerhoff et al., Federarbeiten der Indianer Südamerikas aus der Studiensammlung Horst Antes, Oktagon Verlag, Stuttgart, 1995, no. 223

- Real Jard’n Botánico, Arte Plumario de Brasil, Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana, Comisión Quinto Centenario, 1988, p. 10, fig. 215

The Rikbaktsa people live in the continuous Indigenous Lands Erikbaktsa (1968), Japu’ra (1986) and Do Escondido (1998), in the Amazon rainforest in Brazil, Mato Grosso, and around Rio Juruena & Rio Sangue.

This group’s self-denomination – Rikbaktsa –means ‘the human beings’. Rik means person, human being; bak reinforces the meaning, and tsa is the suffix for the plural form. In the region they are called Canoeiros (Canoe

People), in reference to their ability in the use of canoes, or, less commonly, Orelhas de Pau (Wooden Ears), due to the use of large plugs made of wood to decorate their stretched earlobes.

Since the 17th century Rikbaktsa lands have been visited by Europeans, and both have always been hostile towards each other. By repute, the Rikbaktsa always were at war with the neighbouring tribes, being known as fierce warriors. Ages of European oppression and exploitation diminished the population numbers, but in the 1970s there was a change in the approach of the missionaries towards the Indigenous, recognizing their right to their own culture. Since the end of the 1970s the Rikbaktsa have struggled to regain control over part of their traditional lands. In 1985 they managed to recover the area known as Japu’ra and continued their effort to get back the Escondido region, which was finally demarcated in 1998. However, it is still occupied by miners, timber companies and colonization companies.

Part of the revenue will be donated to the Rikbaktsa for conservation and protection of their rightful lands.

17.

A sailor’s polished Giant Amazon Arrau River Turtle (Pdocnemis expansa) shell England, 19th century

H. 68.5 x W. 58 cm

This is the shell of an Arrau Turtle or Giant Amazon River Turtle. These creatures are not white, as one would expect from the colour of this specimen. Upon return, European sailors would stock up on live turtles in their ships and try to keep them alive for as long as possible. Quite brilliant because the turtle would be fresh and could feed over a hundred men. In their spare time, the sailors would start polishing a shell, layer after layer, until it was white and would sell it as albino in the English harbour of arrival.

18.

A splendid Portuguese-colonial Brazilian silver ewer and basin Rio de Janeiro, circa 1780, with an unidentified maker’s mark HSC, and town mark R for Rio de Janeiro

L. 53 x W. 39 x H. 4 cm / Weight: 2480 grams (basin)

H. 30 x W. 12 cm / Weight: 2040 grams (ewer)

The quality of this ewer and basin, both in form and in chiselling and engraving truly is exceptional. They probably are by the same maker as a very similar ewer in the Catedral São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro, and an ewer and basin, in the Mosteiro de São Bento, a monastery in Rio - both unmarked and dated second half 18th century. The most obvious difference is the handle which in these two ewers is in the form of a dragon instead of a woman. Brazilian silver, even very large pieces, mainly when ordered by the church, is very seldomly marked, and so far, no research into Brazilian silver marks has been conducted. The use of these handwashing basins and ewers at the table was a welcome requirement due to the frequent absence of cutlery.

Literature:

- Humberto M. Franceshi, O Of’cio da Prata no Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 1988, p. 182-185

- Manuel Gonçalves Vidal, Marcas de Contrastes e Ourives Portugueses, Lisbon, 1974

19.

French School (early 19th century)

‘Henri Christophe, Henri I, King of Haiti’

With old label reading Portrait de l’Empereur d’Haiti Oil on canvas, H. 57.8 x W. 43.8 cm

Provenance:

John Charles Frear, New York

His sale, Christie’s New York, 20 October 1988, lot 164

Sale, Christie’s, South Kensington, 9 October 2012, lot 319C Private collection, France

Depicted here is probably Henri Christophe (1767-1820), a key leader in the Haitian Revolution and the only monarch of the Kingdom of Haiti. Christophe was of Bambara ethnicity in West Africa. Beginning with the uprising of enslaved Africans of 1791, he rose to power in the ranks of the Haitian revolutionary military. The revolution succeeded in gaining independence from France in 1804. In 1805 he took part under Jean-Jacques Dessalines in capturing Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) against French forces who acquired the colony from Spain in the Treaty of Basel. Soon after, he was promoted to colonel and admiral in contemporary sources, according to his title ‘Almirante de Marina’.

After Dessalines was assassinated, Christophe retreated to the Plainedu-Nord and created a separate government. On 17 February 1807, he was elected president of the State of Haiti, as he named that area. Alexandre Pétion was elected president in the south. On 26 March 1811, Christophe created a kingdom in the north and was proclaimed Henry I, King of Haiti. He also created a nobility and named his legitimate son Jacques-Victor Henry as prince and heir.

On 18 June 1809, British ships HMS Latona and HMS Cherub captured the French flagship Félicité, which had left Guadeloupe in company with another frigate sailing to France with colonial produce. The frigate escaped through superior sailing despite Cherub having conducted a long chase. Félicité was captured and seized, and the British sold the vessel to Henri Christophe’s State of Haiti the next month. The Haitians renamed her Améthyste. The French had their flagship seized and their colony lost, which was painful. The ship in the back is shown as a spill of victory behind the king. It is based on an engraving by Thomas-Charles Naudet (1773-1810) depicting the battle of Cap Français (Cap Haitiën) in 1802, titled Prise du Cap Français par l’Armée Française, sous le commandement du Général Le Clerc ; le 15 et 20 Pluviose, An 10. Paris. Prints like this would be spread and collected amongst the French. This battle in the north of Haiti was precisely where Henri Christophe defeated the French and freed the country from slavery. The king points at a drawing of a ship with a pair of compasses, a symbol of Henri laying the foundations for the Haitian Navy. The portrait is distinguished from a generic ‘orientalizing’ portrait of an African prince or Pirate by the French flag, a prominent feature in the painting. Many French would immediately recognize it as the seized flagship with their enemy proudly depicted in front of it.

Richard Evans (1784-1871) made the only official portraits of Henri and his son Prince Jacques-Victor-Henri Christophe in circa 1816. They are depicted as a military men focussing on his achievements in the revolution and not as a monarch. Grand socioeconomic ambitions characterized Christophe’s rule, and he used a despotic hand to achieve them. However, Christophe, who was illiterate, was deeply committed to public education and its ability to transform Haitian society. He saw it as a tool to combat racial prejudice internationally by allowing Haitians to reach their potential and showcase to a prejudiced world an enlightened Black nation.

Christophe (portrayed in the style of Reynolds and Lawrence) desired to visualize his rule through a known language borrowed from English taste - in further rejection of the French. Accordingly, he sent them to other heads of state as advertisements for his enlightened government and abolition. At the same time, caricatures started to appear in Europe, delegitimizing his rule and strongly contradicting this appearance.

King Henri I is known for constructing Citadel Henry, now known as Citadelle Laferrière, the Sans-Souci Palace, the royal chapel of Milot, and numerous other palaces. Under his policies of corvée, or forced labour bordering on slavery, the Kingdom earned revenues from agricultural production, primarily sugar; but the Haitian people resented the system. He agreed with Great Britain to respect its Caribbean colonies in exchange for their warnings to his government of any French naval activity threatening Haiti. In 1820, unpopular, ill and fearing a coup, he committed suicide. Jacques-Victor, his son and heir, was assassinated ten days later.

Why the king is depicted wearing a page costume, which enslaved black servants were often made to wear in Europe, remains unclear. However, it is possible that a French painter made this painting and drew his inspiration from his poor knowledge about the appearance of black people. Could Henri have ordered this portrait right after his naval victory before he formed his enlightened plans, or is he depicted as an illegitimate pirate king?

Sources:

D’az Calcaño, “Richard Evans, Portraits of the Caribbean’s first Black king and prince,” in: Smarthistory, May 12, 2022

Sullivan Robles, “A Black King in the Caribbean” in: Solving Social Issues through Multicultural Experiences: 20th Conference Monograph Series, NAAAS & Affiliates, Scarborough, 2012

Conerly, “’Your Majesty’s Friend’: Foreign Alliances in the Reign of Henri Christophe,” MA diss., University of New Orleans, 2013 Bailey, The Palace of Sans-Souci in Milot, Haiti, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin, 2017

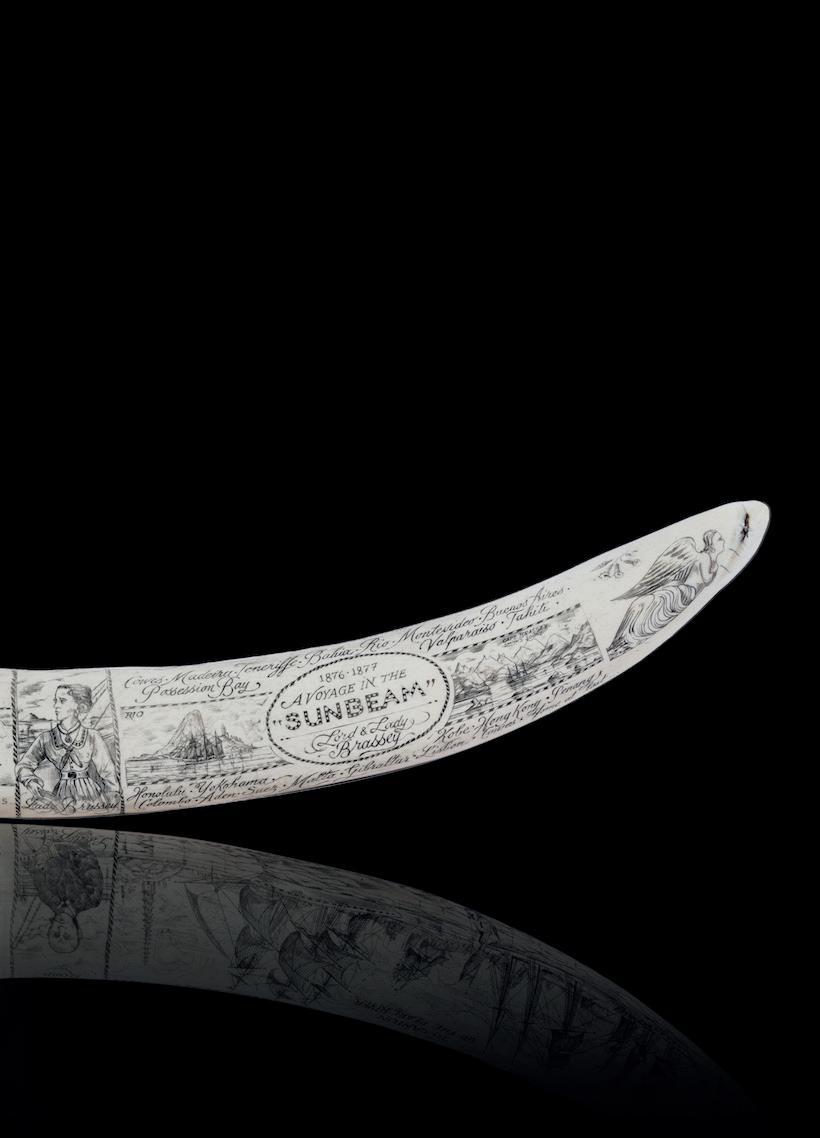

20. A ‘Scrimshaw’ elephant ivory tusk depicting ‘The Voyage in the Sunbeam’ Circa 1877

L. 65 x W. 12 x D. 8 cm

Provenance: Christie’s London, 10 November 1994, lot 60 Private collection, United Kingdom With Martyn Gregory ltd., London

Depicted here is the Voyage in the Sunbeam, the famous voyage Lady Anna ‘Annie’ Baroness Brassey (1839-1887) her husband Thomas Earl Brassey (1836-1918) and their five children undertook in 1876 and 1877. They boarded their luxury yacht Sunbeam and travelled the world. A full account of their journey via amongst others South America, Hawaii, Japan, China and Sri Lanka was first published in 1878 as “Around the World in the Yacht ‘Sunbeam’, our Home in the Ocean for Eleven Months” written by Lady Brassey. The novel comprises fantastic stories of a longlost world. Amongst them their visit to the Maharaja of Jahore who “… gave me some splendid Malay silk sarongs, grown, made and woven

in his kingdom, a pair of tusks of an elephant shot within a mile of the house…” according to Brassey.

After their travels, they welcomed King Kalākaua of Hawaii in July 1881 who had been greatly pleased with her description of his kingdom. He was entertained at Normanhurst Castle and invested Lady Brassey with the Royal Order of Kapiolani.

The illustrations in the book are after etchings by the Honourable A.Y. Gingham, who worked for Brassey aboard the Sunbeam. We can safely assume that he was given this tusk by Lady Brassey, after she received a pair from the Maharaja, to engrave the voyage on this elephant tusk, thus making it a rare literary relic.

21.

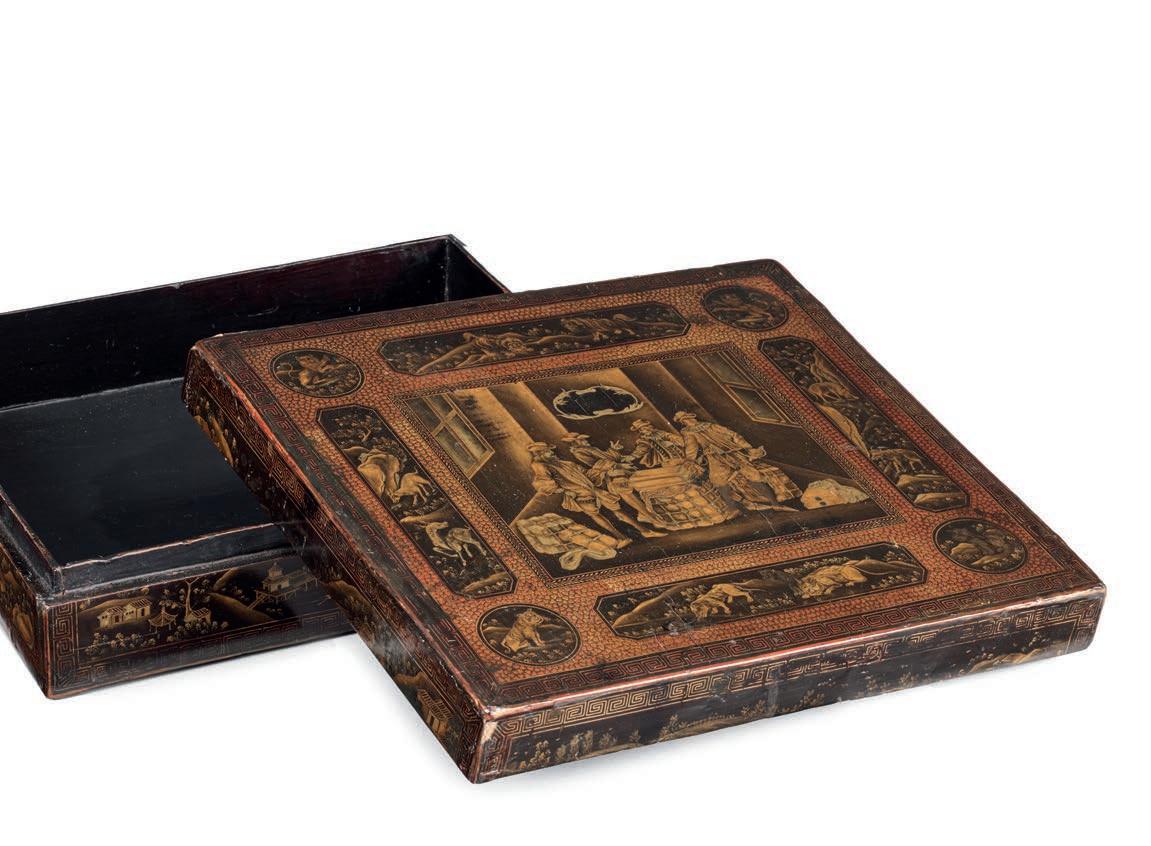

A Persian export lacquer Chinoiserie box for the Dutch market depicting Leiden cloth-traders

Persia (Iran), Qajar, 19th century

H. 7.6 x W. 28.8 x D. 25.5 cm

Provenance: Private collection, United States

This simple, rectangular lacquer box offers a most curious mixture of cultural influences that skilfully masks its likely point of origin. The dichromatic composition in black and gold immediately strikes us as being East-Asian, especially when discovering the distinctly Chinese landscapes and junks – with a single Dutch 17th -century VOC three-masteron the sides of the box. However, careful inspection reveals that all the motifs are oil painted rather than using the EastAsian technique of sprinkling gold powder into unhardened lacquer, ruling out China or Japan. Further studying the beautifully spirit-varnished lid, we can distinguish four unmistakably European traders who are in conclave about a large batch of neatly folded cloth. Are we then looking at a European-made Chinoiserie lacquer box?

Chinoiserie designs did occur in European lacquer workshops in the 19th century (the Adt factory in Saarbrücken and Forbach is known to have produced such items) influences of Islamic/Persian lacquerware were limited to early Venetian lacquer of the 16th and very early 17th century – which this box certainly isn’t – ruling out European lacquer.