OUP is proud to put both teacher and student wellbeing at the heart of our educational offering. From professional development courses to grab-and-go resources created with experts and thought leaders, OUP strives to make wellbeing simple in a busy work climate.

87% of teachers in a recent Oxford University Press (OUP) Educational Research Forum survey said that support for students’ mental health and wellbeing was a priority for their school.

Explore our easy-to-navigate hub and integrate wellbeing into everyday learning with free resources, information, and products for teachers all around the world.

Scan the QR code to browse our hub and see how Oxford’s wellbeing offering can transform your school today.

By Ochan Kusuma-Powell and Kendall Zoller

By Ochan Kusuma-Powell and Kendall Zoller

Imagine if all schools were designed specifically for the students they serve. How might they be different from the way they are now? We suspect the differences might be evident beyond the confines of the classroom and extend to the way adults relate to one another as they work together. When a school is designed for its students, it creates an inclusive culture where every member of the community feels known, loved, safe, and successful.

When a team experiences synergy, it develops a collective spirit that propels the group forward. This collective spirit contributes to a sense of community, where everyone feels included and valued. Each person’s participation is necessary for the success of the whole, and they find deeper meaning in their work because of that spirit. What would it take to create and sustain such a culture? What liberatory courage would it take

to dismantle existing systems that are getting in the way? It would require adaptive thinking to create what has been elusive up to this point in time. This article will explore the importance of developing a sense of inclusion, how teams can arrive at this synergy, and why it is crucial for creating a successful school culture.

Many of us can remember a time when we were excluded and the social pain associated with it. Our social status in the moment meant what we said, felt or thought made no difference, and might even have been a hindrance to the group. Under such difficult conditions, learning is negatively impacted. Unlike physical pain, social pain is re-lived again and again because this kind of pain preferentially engages the affective pain system (Lieberman, 2013). Rejection does not

encourage contribution or thinking.

In contrast, an inclusive environment is one where everyone feels welcomed, respected and valued, regardless of differences in background or experience. Members of the community have equal access to opportunities, resources and benefits. Barriers that would have prevented people from participating fully and contributing to the work of the organization have been removed. Being inclusive means embracing diversity, seeking out differences in opinion, and recognizing the unique talents and perspectives that others bring to the table. Inclusion frees people to achieve their personal best. Being inclusive requires us to examine our own privilege and recognize how others might not have access to the same opportunities. When we are able to perceive how others don’t have access, we can see how to remove barriers.

We define inclusion as the extent to which members of a group or community feel known, loved, safe and successful: acknowledged, cared for, secure and accomplished. These dimensions are easily recognized as essential to human well-being and provide the environment necessary for collaboration. They are also scalable across multiple and diverse stakeholder groups, including all members of a school community: ranging from students and teachers to non-teaching professionals and parents. When these dimensions are prioritized and integrated, they create a culture of acceptance and inclusion. When an individual feels included, they experience these four dimensions in the following ways:

People in the organization recognize and value me

• People know who I am

• I matter and feel respected – I enjoy status within the organization

• Others listen to me when I speak

• What I say counts – I have voice

By design, many, if not most, communities are homogeneous and exclusive in nature. We gather in like-groups and develop activities around our similarities. Without challenging what or how we act in life, we will not easily perceive the groups that have no access to our rituals and traditions, nor access to their own rituals and traditions. There is a paradox inherent in inclusion: in biological terms, we are wired to seek similarity. In social situations, privilege goes to those most like the group in power. Despite this, our frontal lobes contain a moral filter that seeks fairness and equity independent of similarities. This makes the road to inclusion an arduous path. To become more sensitive to the effects of privilege, we must first acknowledge its existence. Otherwise, we remain blind to its impact and may feel our success is due solely to our own merits.

In an illustration of white privilege, Kendall was offered the post of

People in the organization care about me

• They are interested in my growth and development

• I can be my authentic, best self

• I am accepted for who I am

• Others show me personal regard – I feel appreciated and valued

People engage with me without judgment

• I can take risks and others will not be judgmental towards me

• I can make mistakes and be forgiven

• I am not bullied

• Others are careful and conscious of not committing micro-aggressions against me or others

I find meaning in the work I do

• I am encouraged to be self-directed

• Even as I work towards the organization’s success, I also have my own, personal goals

• I have a sense of achievement about my work – I can grow and learn in this environment

• My values are aligned with the values of the organization – they are a good fit

Science Coordinator in a district of 55,000 students, even though he was a new teacher with only 17 months of classroom teaching experience. 164 other, more experienced science teachers were bypassed. Kendall’s race, gender and physical appearance – white, male, and over six feet tall – likely played a role in his selection. In an example of exclusion, Ochan was often the only person of color on the list of invited guests to receptions honoring incoming diplomats or noteworthy scholars – in countries where the majority of the population was non-white. In these instances, she experienced being treated like wait staff when other invited guests asked her to

refresh their drinks. Her exclusion, due to outward appearances, immediately placed her in the ‘outgroup’.

When people feel valued and respected, they are more likely to be engaged and motivated in their work, leading to greater innovation and creativity. However, creating an inclusive culture isn’t always easy, and requires intentional effort. Beyond examining our own biases and cultural assumptions, we need to actively seek out and value different perspectives and voices so that individuals feel safe to express themselves and their ideas without fear of discrimination or marginalization. Being deliberately inclusive is the right thing to do because it contributes to the dignity of humanity. It is challenging because it asks each of us to cross boundaries into the unknown or partially known, to bring to the table those from other cultures and traditions, and those from groups unlike our own.

In a survey, we asked stakeholders: To what extent do you feel included? To what extent do you feel known, loved, safe and successful? Before the COVID pandemic, we conducted a study on schools and organizations that had taken on training in developing collaborative skills through the Adaptive Schools framework (Garmston & Wellman, 2016). We also interviewed the authors of the original work, heads of school, a UN agency director, and other groups we had collaborated with. Survey results included administrators, teachers, nonteaching professionals, students, and parents. We asked stakeholders to tell us what it was ►

that contributed to their sense of membership within their organization: how did they know they were known, loved, safe, and successful in their communities? The consensus was that relationship-building is key to making everyone feel known, together with a strong focus on diversity and common core values. People also felt appreciated and heard, in a culture of collaboration, trust, and equity.

To foster a culture of inclusivity, we believe that communicative intelligence and systems are crucial. Communicative intelligence involves using skills such as empathy, active listening, and recovery to communicate effectively and authentically. Systems refer to the structures, boundaries, and practices that support relationship-building and equity. Leaders play a key role in designing these systems to ensure that everyone has a place, purpose, and freedom to be themselves. Ultimately, our goal is to create liberatory systems that promote equity and selfactualization, grounded in humanized pedagogies that recognize the importance of identity and intersectionality. By building strong relationships and fostering inclusivity through communication and

systems, we can help everyone in the community feel known, loved, safe, and successful.

The following story exemplifies the importance of building strong relationships necessary to navigate adaptive challenges.

Recognizing the downward shift in student numbers after Covid, the Board of Directors of a European international school knew they had to trim the budget. They decided to cut the school’s learning support program for students with intensive learning needs, which had only been in operation for four years. When the new head of school arrived in July for the next academic year, he was greeted

with letters of protest from the US Embassy, the United Nations, from many teachers and parents - who felt that, while expensive, the program had captured the spirit and hearts of the community. It was now something they were proud of. On the other hand, there were also letters offering support for the decision to put a stop to the program. These stakeholders realized it was a lot of work and their own enthusiasm for it had waned; such a program would require extensive support that might not be sustainable.

At this point, the new head of school realized this was an adaptive challenge facing the school – there were conflicting values represented in the school and community. Part of the community valued a program designed to meet the

needs of students. Another part of the community valued fiscal conservatism while also acknowledging the additional work burden some were anticipating. The head made the decision to spend the bulk of his first year studying the issue from all sides. He held focus group meetings and spoke to as many community members as possible. He built relationships to gather data and to learn what issues were at the heart of the intensive needs program. At the end of the second term, the new head had arrived at a decision. He was going to recommend to the Board to reverse their previous decision and keep the intensive needs program. He recognized the program stood for hope, symbolizing what was good about the community. It was what students in the school needed and deserved. The path was laid out.

This challenge required more than a simple technical solution of policy and implementation. The entire community would need to find common values and the inclusion of a variety of stakeholders. The head moved to develop a shared language and a place for perspectives to be heard. Using meeting protocols that ensured equity of voice and safety in the

To foster a culture of inclusivity, we believe that communicative intelligence and systems are crucial.

form of expression without judgment, the community could focus on students and joy in their work. The conversation had shifted. Stakeholders had unified around a common goal with common values.

Creating a culture of feeling known, loved, safe and successful requires intention. It is the work of building, supporting, and developing relationships for the times when conflicts arise, as in this case. The urgency we all face in such a challenge has two facets: one facet is to recognize that, while we might be in the midst of turmoil, we need to act now because relationships are being harmed, factions are forming, the community is fracturing and students are not being served. The second facet is to develop agility: we never know when the beast of conflict will emerge, and if we have strong relationships in place in a culture of being known, loved, safe, and successful, the pathway is often easier, more respectful, and less harm is done.

In his 2019 book How to be an Antiracist, Kendi asserts it is insufficient to be not racist; to fight racism one must work actively to be an antiracist. The insertion of the prefix ‘anti’ suggests that racist structures can only be dismantled through deliberate action. Similarly, Tulshyan (2022) writes that inclusion is not a passive act, and requires intentionality in our inclusion of others. It is an act of liberation. It is not sufficient merely to believe that every member should feel known, loved, safe, and successful. It requires continuous action by taking a liberatory stance that eliminates elements of systems that block inclusion. We now offer examples from three

contexts: self, teams and system.

At the self or individual level, effective communication involves actively listening and using skills such as paraphrasing, pausing, assigning of attributes, and getting into rapport. While these skills sound simple, they are often challenging to implement in the moment, especially when the existing relationship is weak or damaged.

Moving to the team level, the same communication skills are essential to create a safe and inclusive environment for all team members. Building relationships is critical to achieving psychological safety, particularly as we don’t usually get to choose who we work with and differences and conflicts will arise in complex human systems. For many of us, building relationships is a simple task when those we work with enjoy a deep mutuality. The challenge lies in relationships that are not strong, where differences might be significant and where values clash. Adaptive inclusion involves forging relationships towards common goals in an ecology that balances the everpresent tension between collaboration and autonomy.

At the systems level, there are two areas of focus. First, it’s important to examine critically the rituals and practices

References

to determine who is and isn’t included, to ensure that all voices are heard. In what ways are current systems meeting or not meeting the needs of all students in the school? Second, practices of gathering, including meetings and professional development events, can play a crucial role in building a positive and inclusive culture. Routines and practices around meetings can serve to develop a group to this end. In HeartSpace (Issa Lahera & Zoller, 2020), the authors offer a framework for organizing meetings and work time to create conditions for individual and collective growth and accomplishment. The authors further assert that:

‘People need each other and need to have positive relationships in order to get things done. There is not enough time to complete everything that needs to be done. Challenges arise without there being a mechanism in place to address them. HeartSpace creates a positive culture of adaptivity. Positive cultures only happen by design and these practices are the design’ (p1).

Creating an adaptive and inclusive culture that fosters a sense of belonging and enables everyone to thrive requires personal commitment to relationshipbuilding and a liberatory stance in systems analysis. This is a continuous process that begins with relationships, and is essential for everyone to feel known, loved, safe, and successful. ◆

Ochan Kusuma-Powell, EdD has had a lifelong interest in developing inclusive schools and currently serves as a consultant to international schools in the areas of coaching, collaboration and inclusion.

✉ powell@eduxfrontiers.org

Kendall Zoller, EdD is an author and global consultant on communication, facilitation, and leadership.

✉ kvzoller@sierra-training.com

•Garmston B & Wellman B (2016) The adaptive school: A sourcebook for developing collaborative groups (3rd ed.). Washington DC: Rowman & Littlefield.

•Issa Lahera A & Zoller K (2020) HeartSpace: Practices and rituals to awaken, emerge, evolve, and flourish at work and in life. Burlington, ON: Word & Deed.

•Kendi I (2019) How to be an Antiracist. New York, NY: One World.

•Lieberman M D (2014) Social: Why our brains are wired to connect. New York, NY: Crown.

•Tulshyan R (2022) Inclusion on Purpose: An intersectional approach to creating a culture of belonging at work. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

As described in Challenges Faced By Women Who Lead, Part One: Four Themes from Interviews with Women in School Leadership, published in the Spring 2022 issue of this magazine, in the Spring of 2020 I interviewed over 70 successful female leaders, in international schools as well as in some public and private schools around the world, to seek their personal stories and insights on the challenges and realities facing women in leadership in education. Those interviews highlighted many of the unique challenges that women face pursuing a leadership role in schools – and their stories can help aspiring leaders recognize that the path to leadership may share some common experiences and barriers for those who do not fit the stereotypical view of ‘a leader’.

The first article focused on four major themes that emerged from these interviews:

• unconscious bias and daily microaggressions;

• physical expectations;

• linguistic expectations; and

• cultural expectations of ‘leaders’. In this article, I will highlight some specific stories regarding four more areas of challenges which emerged from these interviews, including:

• perception (or reality) of lack of opportunities for women;

• exclusive networking practices among ‘traditional leaders’;

• impostor syndrome and double standards; and

• availability of mentorship and guidance. All the direct quotes included below are excerpts from the Women Who Lead Interview Series (Cofino, 2020).

Many interviewees mentioned the widespread perception that there

are limited opportunities for women leaders, and several pointed to the lack of visible role models as contributing to this perception. This is particularly noticeable in the international school environment, where leadership teams tend to be very male-dominated. Katrina Charles, International Baccalaureate Diploma Coordinator at the American School of Doha, highlighted that it’s difficult to find women, particularly strong women, within leadership. Within her career she has often been ‘the only woman on the senior leadership team; or the only woman, ethnic minority; or the only member of an ethnic minority on a leadership team’.

Ultimately, pursuing a leadership pathway in an environment where, as Nadine Richards, then High School Principal at the American School of Dubai, noted, ‘the glass ceiling still exists’, is an ongoing challenge. As she pointed out, ‘it’s been an historical factor and things just don’t change overnight’. While we may perceive (and hope) that there are more women in senior leadership positions, making this a reality continues to be a slow and long term process.

Madeleine Heide highlighted that, although we may see more women in lower leadership positions, the gap widens when you begin applying for a Head of School position, and ‘women have to work harder to successfully secure a position at the very top level of our schools’. Madeleine recalled that she was interviewed for 15 different positions and was rejected. Because it’s not that common for a woman to be Head of School, she could feel them ‘wondering as they are looking at you “Can you lead?”.’ Women, and particularly women of color, have to prove themselves over and over again to be viewed as successful leaders.

This combination of lack of visibility of strong, successful women leaders, alongside the societal expectations of leaders and the all-too-prevalent belief that there are limited positions for women, can lead to women feeling as if they are isolatedly competing with each other for positions, rather than supporting each other.

The disproportionate representation of white male leaders of a specific age becomes even more visible in upper level networking opportunities. In my conversation with Nicole Schmidt, High School Principal of the American International School Johannesburg, she shared her experience of walking into one of the cocktail events during leadership recruiting fairs and seeing almost exclusively older white men. As Nicole stated: ‘There’s a bubble around access and the engagement and conversations that happen in those social circles are not particularly welcoming unless you’re in that clique. If you don’t know how to play that game, it’s hard to

break in.’ Seeing a very homogeneous group moving from one senior leadership position to another makes it very challenging for anyone who doesn’t ‘fit the mold’ to become part of that exclusive group.

As Junlah Madalinski pointed out, getting a foot in the door for a leadership position is often overly reliant on who you know. It’s very common to hear that ‘you need a network’ or ‘you need to put yourself out there’, but if you don’t yet have that social currency, as a newer leader it can be so much more difficult. Junlah also noted that because the international school community is so homogenous, it’s even harder for women of color to make those supportive social connections that will help them leverage a network.

Many women mentioned feeling so unsure of themselves that they might end up sabotaging their job search before it began. Rachel Caldwell recognized that she has had bouts of impostor syndrome throughout her career, facing feelings of self-doubt and inadequacy, in particular when looking at job descriptions. Despite being confident that she met the majority of the requirements, she still wouldn’t apply, even though she saw her male counterparts applying when they seemed to have fewer of the required skills and still being successful.

Taking over an internal position at a school can also bring up discouraging doubts. Fiona Reynolds, then Deputy Head of School at the American School of Bombay in India, talked about impostor syndrome as ►

although we may see more women in lower leadership positions, the gap widens when you begin applying for a Head of School position

being a struggle where we’re ‘faking it and we’re not sure if we’re making it’. When she had the opportunity to be the acting Head of School, she became so stressed that the idea of taking on the role was physically making her suffer. She realized that if she could be brave enough to be who she is, rather than worrying about filling the shoes of the previous Head, then she could be successful.

Catriona Moran, Head of School at Saigon South International School in Vietnam, shared a number of stories of being perceived as being ‘too nice’ to be effective in a leadership role. She shared a particularly fascinating story about being the lead administrator for the design of a construction project. ‘One meeting there were 20 people in the room (19 males, and I was 8 months pregnant). Any time a decision needed to be made, the others looked to my male colleague –even though I was making the decisions.’ As she points out, there is a perception that women might not be able to step up and make, and then communicate, hard decisions.

Junlah Madalinski pointed out that ‘Mentorship is critical and crucial, but it is a privilege. For women of color in educational leadership, it’s not something that is afforded to us. Especially if we’re seeking out mentors who are also women of color, especially if we’re seeking out heads who are actively doing social justice work.’ This often makes it challenging for women of color to find a mentor within the international school community. Clarissa Sayson has faced the same challenges, noting that there have been limited opportunities to connect with women leaders in the early stages in her career. In fact, she said ‘It’s only been in the last five years that I’ve been able to look to female leaders.’ It will likely remain challenging for many women

to find mentors who look like them until there is more equal representation at the very top levels of school leadership. Although things are slowly changing, it is still a struggle for many women to find mentors who look like them, who share similar life and professional experiences. The reality is that for those who need it most, finding a mentor is likely the hardest.

Sharing these stories is the first step in better understanding the real-life experiences of women pursuing a leadership role in schools. If you would like to hear more from all of the women I interviewed, you can find video clips of all of their stories in Women Who Lead. As aspiring leaders and those who support growing leaders, recognizing these lived experiences can help us begin to develop strategies to counter these obstacles. In addition, just knowing that you’re not alone might be crucial in helping you feel more confident in taking the next steps towards your dream job.

Kim Cofino is Founder and CEO of Eduro Learning: https://edurolearning.com. ✉ kim@edurolearning.comReferences

•Cofino K (2020). Women Who Lead Interviews. [Video Course]. https://edurolearning.com/women

There is a perception that women might not be able to step up and make, and then communicate, hard decisions

Cambridge Primary Insight is a child and teacher-friendly assessment tool, designed to empower teachers to build a strong foundation and unlock the potential of primary children aged 5-11. By using an adaptive baseline assessment across five key developmental areas, you get invaluable insight in an instant.

Are you ready to measure potential?

Scan the QR code to find out more:

One of the many joys of working in an international school is the opportunity to meet and work with people from different cultural backgrounds. It may be the staff, the students, the parents or the people we meet when socialising. At a time when much of the world feels polarised, international schools allow us to be diverse and inclusive with those we meet and work with on a daily basis. For a school leader, the challenge is to create and maintain a unified school culture that encompasses all those within it. Typically, the school culture is identifiable and felt throughout the school, through the community. However, when a school experiences a localised crisis within its community, individuals tend to revert to home culture experience, and different

expectations and demands may be made upon the school.

Critical incidents may be defined as unexpected or unforeseen situations. They may involve or lead to emotional trauma, severe injury, or the death of a student or staff member. Incidents may cause institutional embarrassment or reputational harm, leading to a decline in student numbers or temporary school closure. As the number of international schools continues to rise, it is not a matter of if an incident will occur, but when. Incidents themselves may not constitute a crisis but the manner in which they are dealt with, and communicated, may lead to a crisis within the school community.

During the Covid pandemic I conducted extensive research throughout the wider ASEAN region. Specifically, I surveyed more than 120 leaders from international schools and carried out individual interviews with nearly 20 leaders from 13 different countries. Through this research, I gained insight into how these leaders dealt with a total of 250 diverse critical incidents, and how these incidents affected both themselves and their school communities. While the nature of critical incidents cannot be predicted or prevented by knowing their specifics, the way they are responded to is crucial. The incidents themselves are therefore less important than the response they receive.

International schools often promote and aspire to attributes such as multicultural awareness, global citizenship and international mindedness. However, when a critical incident occurs and emotions run high, people tend to fall back on their native cultural norms and values, potentially losing their multicultural awareness and mindedness. International school leaders therefore need to be aware of this tendency (even for themselves) and remain attentive to the cultural expectations of others during such incidents. Culture may be a significant factor in determining the effectiveness of the response to critical incidents, and the ability of the community to overcome the incident. Cultural dexterity – also referred to as cultural agility or as having cultural intelligence – may be crucial, referring as it does to the ability effectively to navigate and adapt to multiple cultural contexts, arising from a deep understanding and appreciation of the cultural norms, values, beliefs and behaviours of others.

Following a critical incident, it is common for individuals and groups within a school community to display different levels of cultural understanding. Parents, students, staff and even school owners will have varying degrees of exposure to different cultures and will often rely on their own cultural background to navigate a perceived crisis. As a result, some may exhibit a sense of cultural arrogance with respect to their own beliefs, and justifications for them, potentially ignoring or undervaluing the beliefs of

others. Cultural ignorance may well be present among members of the community, and to varying degrees. Such lack of cultural awareness may lead to misunderstandings, conflicts and, more often in an international context, a barrier to effective communication. Some members of the community will show cultural empathy, and a desire to understand others’ perspectives. In most cases cultural empathy is supportive, but it can lead to some individuals championing the cause for others, leading to unrealistic expectations of the international school. Some members of the community may

English), or the use of multiple languages to match those of their community. Each choice has its own pros and cons.

Using a single language can provide consistency and facilitate faster communication between different members of the community. However, it may also create a cultural bias towards those who are proficient in that language, leading to feelings of exclusion and confusion among those who are not. Using multiple languages can promote inclusivity and create a more diverse and vibrant community. Multi-language communication also has its challenges

simply show cultural tolerance and not question decisions and outcomes.

It is essential for international school leaders to recognise these differences and endeavour to communicate clearly a sense of the school’s own cultural awareness and sensitivity within all members of the community. Language is a crucial aspect of culture and plays a vital role in the school’s communications. In a multilingual setting, language management is necessary to change the cultural arrogance of a situation to one of cultural empathy. International school leaders must consider their choice of language, whether it is a single language (typically

in terms of logistics, accuracy and intended meaning for all members of the community. Ultimately, international school leaders must be aware of the cultural expectations of all members of their community and manage language effectively in order to promote cultural inclusivity. Following an incident they must be able to provide direction that benefits everyone, regardless of their cultural background or language proficiency, if they are to build a school community that is understanding and supportive of the school’s actions.

As an international school leader, developing cultural dexterity is crucial in today’s interconnected and diverse world. Cultural dexterity involves understanding and appreciating the different perspectives and beliefs of students, staff, parents and school owners from diverse cultural backgrounds. Developing cultural dexterity helps leaders to navigate the complex cultural landscapes of their schools and to manage cultural conflicts more effectively. It can enable clearer communication and build trust and rapport with members of their community – and, therefore, help to prevent an incident from becoming a crisis.

✉ ianfoyles@gmail.com

Using multiple languages can promote inclusivity and create a more diverse and vibrant community

By Vanessa Miller and Margareta Tripsa

By Vanessa Miller and Margareta Tripsa

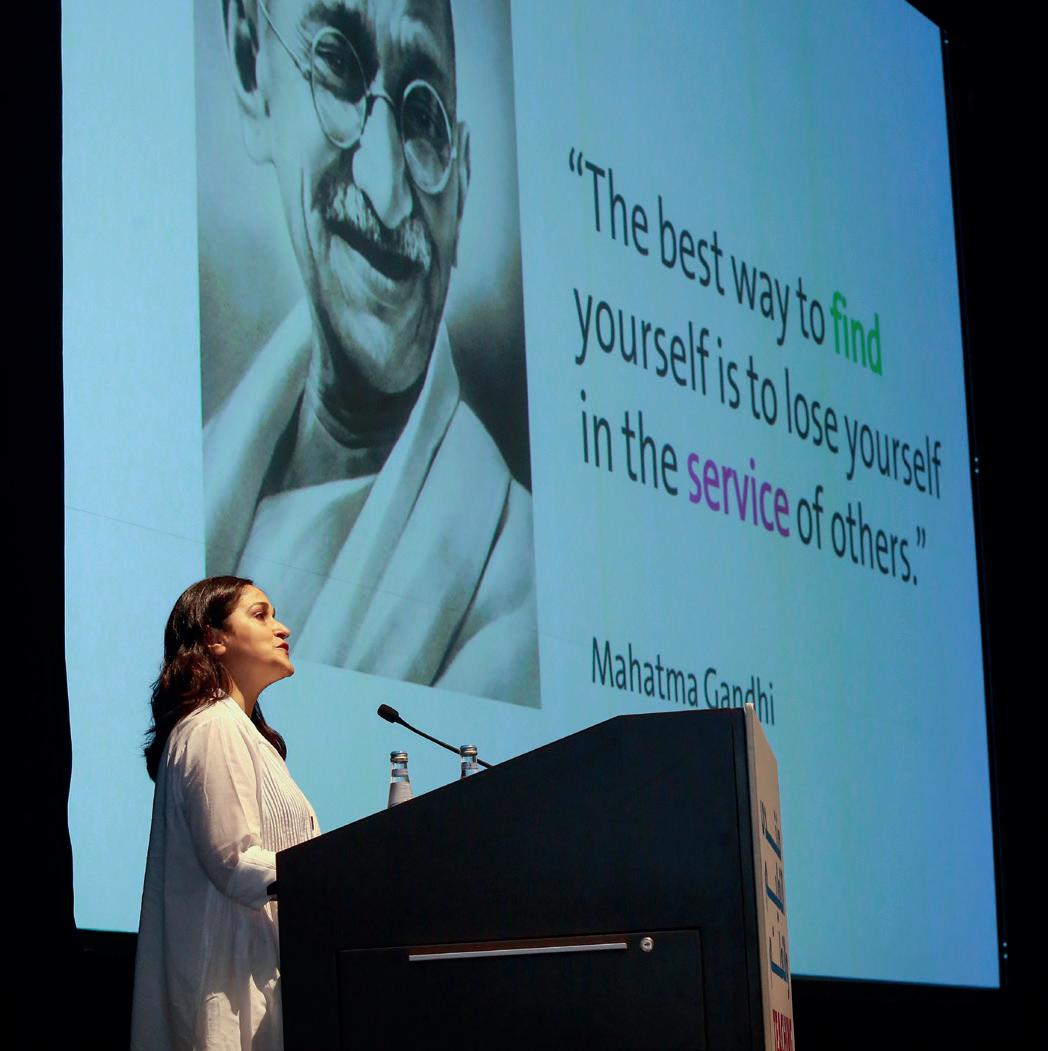

Amidst the bustling energy and eager anticipation of a professional conference, educators from all corners of the globe come together collectively to pursue growth, development, and innovation in their field. Conferences provide opportunities for re-energizing, networking, and interacting with thought leaders. In the words of Stephen Covey (1990), a conference is an opportunity to ‘sharpen the saw’. Participating in conferences and workshops is a common experience for many educators, yet how often do we have the opportunity to consider the making of these professional learning experiences? For the professional learning designer, a conference also provides many opportunities: opportunities to catalyze change, create collective understanding, and nudge educators to consider new approaches.

The Teaching and Learning Forum, hosted by Qatar Foundation’s Education Development Institute, is an annual professional learning conference for local and international educators. During the Teaching and Learning Forum 2022, educators from Qatar Foundation, local and global organizations, keynotes, accelerators, and educational leaders from Qatar and across the world shared innovative approaches to service learning. The 2022 Forum theme chosen by the directors of Qatar Foundation’s schools targeted an identified common need: service learning. In selecting this theme, school leaders hoped to spark a conversation around best practices as well as to connect educators with relevant and potential partner organizations. The first step in creating a professional learning conference is creating a call to action – transforming a critical area for exploration, such as service learning, into an invitation for educators, potential workshop leaders, and keynote speakers. The Education Development Institute pinned the 2022 Teaching and Learning Forum theme as ‘Learning in Service and Action: Creating meaningful connections, developing local and global learning communities’.

The ultimate goal of the conference was to inspire change and provide educators with innovative approaches to service learning, striving to create opportunities

for learners to address societal, ecological, and community needs both locally and globally through authentic experiences. Change and innovation are related. Change is continuous when a growth mindset supports it. Many factors influence change, including fostering a disposition for constant learning. ‘Innovation’ is derived from the Latin verb ‘innovare’, which means to renew. Innovation can refer to something new or to a change made to an existing product, idea, or field. Innovation is really about responding to change creatively. Innovation adds value by applying novel solutions to meaningful problems. According to the Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) Theory, developed by E M Rogers in 1962, the speed of diffusing innovation is dictated by the time required to progress through the five different adopter categories: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. To promote change, the Teaching and Learning Forum organizers brought together ‘innovator’ keynote speakers, accelerators categorized as early adopters, and the educators in the audience – who fall into the full range of DOI categories. To achieve the ambitious goal of inspiring educators, thirteen local organizations and eleven global organizations participated in the forum alongside 40 educators serving as presenters. Additionally, because the forum was hybrid, several presenters contributed to the event from Bangladesh, Belgium, Canada, South Africa, Australia, the United States, and Kenya.

In terms of assessing professional learning, conferences and forums tend to receive relatively low ratings. Assessing newly acquired understandings of participants, their skills, or the impact on their learners due to professional learning is challenging. Guskey’s five levels of evaluating professional learning (2011) provide a comprehensive framework for assessing the effectiveness of professional learning engagements. At Level 1, Participants’ Reactions, the focus is gauging attendees’

immediate responses or reactions to the training. Level 2, Participants’ Learning, assesses the extent to which participants have acquired the intended knowledge, skills, and competencies. Level 3, Organization Support and Change, examines how the organization has provided participants with the necessary support and resources to apply their new learning. Level 4, Use of New Knowledge and Skills, assesses the practical application of acquired competencies, while Level 5, Student Learning Outcomes, evaluates the ultimate impact of the professional learning they engaged with on students’ achievement. So, what can organizers of conferences or forums do to enhance the potential impact?

Constructing principles derived from the conference theme enhances the impact of conferences and forums. Defining principles for an education conference can provide a range of benefits for the organizers, participants, and the broader educational community. Defining principles clarifies the conference’s vision and focus. Clearly stated principles guide decision-making processes during conference planning, from selecting speakers and panelists to choosing session topics and formats. They serve as a reference point to maintain consistency and coherence throughout the conference, ensuring that all sessions and presentations align with the overarching goals and themes. Moreover, establishing principles can help organizers measure the impact of the conference by providing benchmarks against which to measure outcomes, such as increased knowledge or changes in practice within the educational community. Therefore, the organizers formulated six principles that support service learning, as shown in the table. The meaning of each principle was clearly articulated to ensure shared meaning for all educators. Defining the principles of service learning helped ensure that it would be carried out in a meaningful, cohesive, and effective way that benefited both students and communities. ►

Change and innovation are related. Change is continuous when a growth mindset supports it.

Agency One can make a positive change in the world through consciously enacting deeply rooted values.

Belonging Meaningful relationships strengthen local and global communities and ecosystems.

Empathy Valuing all living things and understanding the struggles of others is a catalyst for change.

Mobilization Creating meaningful connections and networks increases resources and capacity to problem-solve and enact change.

Privilege Analyzing the advantages and disadvantages for individuals and groups within a social/ ecological system reveals pathways for change.

Courage Accepting responsibility to tackle complex problems together.

connect with organizations around the topic of service learning.

According to the feedback survey, when asked about learning that occurred as a result of attending the forum sessions on service learning 95% of the 647 respondents agreed that they acquired learning as a result of attending the forum. When asked about the extent to which the forum inspired them to apply the principles of service learning in their context, 99% of the respondents reported that they felt inspired to apply the principles of service learning. The reported numbers demonstrate that the conference impacted participants’ willingness to engage in service learning as a result of attending the conference.

The organizers worked with the accelerators and presenters to ensure they designed interactive sessions that encouraged participants to engage with the content and with their peers. This included group discussions, Q&A sessions, or hands-on workshops.

The logistics of the conference provided ample time and space for attendees to connect and collaborate. This included designated networking breaks, roundtable discussions, or social events that foster interaction.

The organizers ensured the conference was accessible to a range of diverse participants, including monolingual attendees, by offering accommodations such as live translations, captioning, and bilingual sessions. Additionally, the organizers included diverse speakers and panelists to foster an inclusive environment.

Connecting the conference’s content to specific school initiatives and context enhances the potential impact. Service as action is foundational to the International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma Programme through Creativity, Activity, Service (CAS) activities and other inquiry projects.

The conference purposefully highlighted connections with service learning in IB. CAS coordinators participated as champions of service learning, as early adopters, and therefore as resources for other educators. Education institutions need to capitalize on their early adopters and work with them to sustain innovation. Typically, conferences and forums generate short-term change. Long-term change happens when the new learning is assimilated and integrated into the current knowledge and skills of the individual. It could also be supported by coaching mentoring practices, by promoting agency and by giving individuals voice and choice.

Another tool for enhancing impact was to provide resources to the conference participants even after the forum was over, and in order to make it easier for the audience to access various service learning communities for their students, a Mobilization Guide that listed the organizations represented at the Teaching and Learning Forum was created. The Mobilization Guide helped educators

The 2022 Teaching and Learning Forum successfully brought together educators from around the world to engage in meaningful conversations and explore innovative approaches to service learning. By focusing on clearly defined principles, active participation, networking opportunities, accessibility, inclusivity, and leveraging early adopters, the forum created a lasting impact on participants. The overwhelmingly positive feedback received from attendees highlights the effectiveness of this approach in inspiring change and empowering educators to integrate service learning into their classrooms.

The forum also demonstrated the value of creating post-conference resources, such as the Mobilization Guide, to support educators’ continued growth and collaboration after the event. This holistic approach to professional learning enriched the conference experience and increased the likelihood of long-term change and implementation of service learning in educational institutions. ◆

•Covey S R (1990) The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People : restoring the character ethic. London: Simon and Schuster.

•Guskey T R (2011) Evaluation : critical to professional development. Principal Matters. (87): 44–48.

•Rogers E M (2003) Diffusion of Innovations. (5th ed) London: Simon and Schuster.

CAS Coordinators participated as champions of service learning, as early adopters, and therefore as resources for other educators

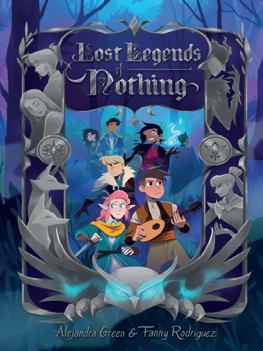

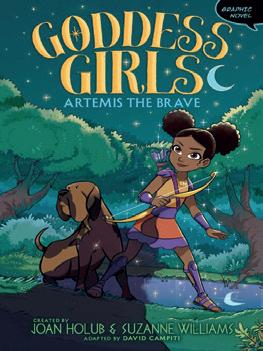

The Sora student reading app offers an extensive catalog that spans the interests and reading levels of every student, and includes titles in over 100 languages. With ebooks for visual learners, audiobooks for auditory learning and diverse subject matter, Sora helps makes sure every child feels included and empowered.

Ilove being a teacher. It is, without doubt, the very best job in the world. No two days are ever the same, there is always something new to learn, and there is always someone who will bring a smile to your day. Yes, there are days when things don’t go right. Yes, there are days when I feel frustrated, but still – the love of my profession remains. It has been like this, for me, for over 20 years. But would I still feel this way if I had remained teaching within a national state system? The sad likelihood is that I might have burned out and be doing something else by now.

I know a growing number of former teachers in the UK who have fallen out of love with the profession. You may know some too; teachers for whom the very thought of continuing (or returning) to work in schools has them reaching for the Prozac. There are record numbers of vacancies in schools, and government recruitment targets

are routinely missed; only 59% of the target for initial teacher training was achieved last year (UK Parliament Education Committee, 2023).

Meanwhile, there seems to be a growing symbiosis between the burgeoning numbers of teachers leaving UK schools and the ever-expanding international schools market. Just as the number of teachers leaving UK schools grows, there is a growing number of schools overseas that are ready to welcome them with open arms. The international school sector has expanded at an almost unbelievable rate since the turn of the century, and it is clear that a large number of teachers moving to work in these schools are UK-trained, looking beyond national borders to reap their rewards.

My recent doctoral research indicated that some UK-trained teachers in international schools are what I call ‘pragmatic idealists’: professional educators who have navigated their way into positions of privilege by trading their personal, professional and cultural capital within a global marketplace. These are people who have an affinity with learning and teaching, who have a passion for their job and wish to develop their career in the best way possible, but who also wish to enjoy a good quality of life outside of their professional interests.

There are international teachers around the world who enjoy a much-improved quality of life as a direct result of their decision to move overseas. Such teachers are aware of the sacrifices they must make in being away from their families and home nations, but nonetheless choose to remain working in international schools due to an improved sense of

I love being a teacher. It is, without doubt, the very best job in the world

personal and professional freedom and wellbeing. The canvas upon which an international school teacher can paint is vast –literally as big as the planet – and the restrictions and limitations placed upon their classroom practice by meddlesome directives and oblique political agendas are not present. One international school teacher I interviewed stated: ‘I remember my last year in the UK: I think that every single day I had a new initiative, either from the local authority, from curriculum, or from the government to deal with’.

Teachers working in international schools may enjoy an improved income, along with a level of privilege and social status that they were unable to achieve back home, no matter how hard they worked. Some academics argue that such privilege is precarious; any teacher who was left homeless and jobless after recent high-profile crises such as the war in Ukraine or the global pandemic would certainly agree with them. However, I believe there is a silent majority of international school teachers who – regardless of their initial motives for moving into the field – are actively developing their careers, playing to their strengths and enjoying a level of personal and professional freedom unknown to them in their home nation.

There is a body of work that suggests teachers in international schools are driven by motivating factors such as a desire to travel and see the world, or to ‘ride the gravy train’ of working in highly paid jobs in the emerging markets of the world; my research indicates that such incentives are not the greatest or most significant factors. The teachers in my study were fully cognisant of the economic benefits and opportunities for travel and exploration that their international career had given them, but more important to them was the freedom to teach. These educators genuinely love their work, and have an affinity with education that could be considered a vocation. All spoke with passion about professional opportunities within their daily practice: to diversify rather than being pigeonholed within one area; to try new things in their classrooms without fear; to hone skills over a number of years without being branded a ‘coasting teacher’.

Whilst some international school teachers may unwittingly fall into a life of precarious privilege and subsequently become trapped in the gilded cage of that privilege, the teachers I listened to were very clear about their professional commitment and personal freedom. The majority believed that the reduction of scrutiny and administrative workload allowed them

to sustain a professional approach whilst still having time for themselves and their families and friends. One teacher described how her years spent teaching in the UK had been ‘work to the brim and I don’t mind that... I love being [busy], but I don’t think it’s sustainable’. As described by Fiona Rogers in the Autumn 2022 issue of this magazine, feedback from teachers in international schools regarding their job satisfaction and personal wellbeing is overwhelmingly positive.

It seems to me that there are lessons to be learned here: lessons for international school leaders who wish to recruit and retain the best teachers for their schools, and lessons for home nation policy-makers who wish to address the recruitment and retention crisis in their schools. Tinkering with curriculum content and wresting control of training provision is unlikely to address the shortfall. What is needed in the first instance is a long hard look at why so many talented and inspirational teachers are leaving the UK for a career in the international school sector. The answers might not be particularly comforting, but once recognised, they will surely help to inform a strategy that can make real and lasting positive change. ◆

References

•Rogers F (2022) Teacher Wellbeing and Perceptions of International School Experience. International School. Autumn 2022. pp 38-39.

•UK Parliament Education Committee (2023) Education Committee launches new enquiry into teacher recruitment, training and retention. https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/203/ education-committee/news/194283/education-committee-launchesnew-inquiry-into-teacher-recruitment-training-and-retention/

It’s a common feeling. We are faced with a task, a problem to solve, a daunting todo list. We roll up our sleeves. We want to ‘tackle’ the problem, ‘do’ the to-do’s and get down to work. John Dewey (1938) recognised this very human tendency as problematic when he wrote ’The crucial education problem is that of procuring the postponement of immediate action on desire until observation and judgement have intervened’.

We frequently see evidence in our classrooms of the mind’s desire to run ahead to the solution as quickly as possible, whether this is driven by the excitement of actually finding an answer to the problem, or by the desire to finish and move on to more exciting activities, or by the sense of frustration some feel when asked to slow down and engage with complexity.

Daniel Kahneman famously illustrated the ways in which humans have developed different types of thinking appropriate to different contexts. What he calls System 1 thinking is fast, associative, intuitive and cognitively easy. It uses the most recent ideas that we

have been exposed to, our memories of what has worked before, and is essential for navigating our complex world as it automatises much of our decision-making. It is the type of thinking that allows us to arrive at work without remembering anything about the drive itself. System 2 thinking instead is deliberative, slow and comes at cognitive cost. For some, it is the type of excruciating thinking involved in assembling IKEA furniture.

When we use the design cycle, we are actually being asked to use both systems.

In the empathising phase, we are seeking to step into the shoes of as many people as we can who may have a point

of view on the issue we are looking at. We are practising deep, active listening, without judgement or hidden objectives – we aren’t just waiting for the person to stop talking so we can get on with our own ideas. We create space, put assumptions on hold. It’s a phase where curiosity is at the forefront and we are looking for expansion and divergent viewpoints. The information gathered, which is necessarily not ‘the way I see things’, needs to be integrated slowly, in a deliberative, System 2 type of way.

Sanders and Strappers (2008) help us visualise what, in the design process model, we could call the empathising stage. They describe this moment with the very technically termed ‘fuzzy front end’, illustrating a non-linear, exploratory phase (see figure on next page).

The defi ning phase of the design cycle pulls the experiences and learning from the empathising stage into focus.

Daniel Kahneman famously illustrated the ways in which humans have developed different types of thinking appropriate to different contexts.

The question that we are seeking to answer is formulated. This is followed by another moment of expansion with the ideating phase. When we ideate, we generate new ideas creatively, often using intuition and association: System 1 type thinking. Sometimes these sessions are bubbling over with ideas. They come fast and furious – the whiteboard is full – the stickies are overlapping on the table. Yet, we are simultaneously asked to withhold judgement and stop our minds from grabbing onto a solution and running with it. In Dewey’s terms, we are postponing immediate action.

What makes design-based education authentic and meaningful, however, is not the techniques and strategies that we scaffold to support different types of thinking, but the question, which is at the heart of the design process. Empathising only teaches us something if it takes us out of our own mind and into that of another. Ideating only becomes meaningful when we are trying to find an answer to a question that matters, and touches our worlds.

An example of the shift away from what I would call an Andy Warhol can-of-soup approach to design-based education occurred recently in a primary classroom in The Netherlands. The ‘students’ in this case were two student-

teachers who were working in two Year 4 classrooms, and were required to design a teaching resource during their internships for their teacher training program. For reasons of efficiency, they came to the situation with a design question in mind (skipping, for the reasons outlined above, any authentic empathising).

Their question was: How might we create a classroom tool to support mathematics learning in a primary classroom? They soon realised that this question wasn’t helpful in getting them anywhere, and accepted that System 2 thinking was required. Through the process of empathising – with the ►

What makes design-based education authentic and meaningful, however, is not the techniques and strategies that we scaffold to support different types of thinking, but the question, which is at the heart of the design process.

classroom teacher, language specialists, the students and the parents – they recognised that there was a pressing need for a group of students who had recently arrived in the class, had very limited knowledge of the language of instruction, and were unable to connect their prior mathematical knowledge to their current learning in order to take forward their understanding of measurement and conversion. The design question became: How might we create a classroom tool to support learning about measurement and conversion for children with varying language levels in a play-based, scaffolded and inclusive way in a Year 4 classroom?

The final product was a series of coloured boxes (see photo) which contained everyday objects corresponding to different units of measurement. Students learned the names of the objects, and conducted treasure hunts in the classroom, at home and outside, to develop mathematical skills of metric conversion and literacy skills focused on the objects and the unit names. The point of the example is not the product, but the process. Authentic learning through design-based education relies on engagement with the context we find ourselves in and a willingness to allow for the ‘fuzzy front end’ in all of its open-ended unpredictability. Understanding the ways in which our thinking systems can help or hinder the phases of the design process is one way of ‘keeping it real’.

References

• Dewey J (1938) Experience and Education. London: Macmillan.

• Kahneman D (2011) Thinking: Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

• Sanders E B-N and Strappers P J (2008) Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. Co-Design: International Journal of Co-Creation in Design and the Arts. 4(1): 5–18.

Dr Debra Williams-Gualandi is Programme Manager of the International Teacher Education Programme (ITEPS/ITESS/MITE) at NHLStenden University of Applied Sciences, The Netherlands.

✉ debra.williams.gualandi@nhlstenden.com

STANDARD LISTING

45,000+ independent & international professionals

15,000 social media reach accross six channels

Included in weekly jobs newsletter

FEATURED

Standard listing PLUS

Featured listing at the top of the Careers Section

Advertising alongside relevant content throughout the site

School Management Plus is the leading print, digital and social content platform, for leaders, educators and professionals within the independent and international education sector worldwide.

Our readership spans every stakeholder within fee paying education worldwide from Heads, Governors, Bursars, Admissions, Marketing, Development, Fundraising and Educators – to catering, facilities and sports. Our jobs & careers center is the natural meeting point for those already in the sector, aspiring to join it, or hiring from within it.

office@schoolmanagementplus.com

PREMIUM

Featured listing PLUS Free listing if the vacancy is not filled

Included on magazine digital distribution to 150,000 readers

Included in school directory

Listing experience hosted on Kampus24

UNLIMITED

Premium listing PLUS Unlimited job listings throughout the year to our audience

Newsletter presence every month for your school

Exposure and features on your school in main careers section

Print adverts for your listings each term

Listing experience hosted on Kampus24

The rst 100 schools to sign up will receive 20% o a year’s unlimited package

• Social following of 15k across 6 channels

• 60% annual growth in web tra c

• Core readership of Heads, Senior Leaders, Heads of Department, Bursars and Finance managers, Marketing and Admissions, and Development across the sector

This article discusses the transformation in teaching and learning arising from the rapid pace of technological developments in recent times. This transformation is driven by the quest to develop new ways of learning and augment the classroom environment by including new technologies and methods. The enormous growth in digital technology and the impact of the global pandemic has propelled profound changes in the way education is viewed, imposing the need to examine the trends that influence classroom practices, new emerging skills, and the potential of human resources to meet the challenges of living and working in the present times. Additionally, learners across the world have become increasingly reliant on social networking technologies to connect, collaborate, and create new learning experiences which stressed the need for the learning environments to undergo a change and integrate new technologies in teaching and learning.

Personalised learning is a developing approach that focuses on customising instructional and academic support to offer an exclusive learning experience based on the individual needs, strengths, interests and skills of each learner. The central tenet of this approach underpins diversity, inclusion and differentiation with a focus on developing learners’ autonomy and individualised learning path. The key focus, therefore, is on the instructional approach, lesson content and activities, the pace of learning which draws upon individual learners’ skills and interests. Personalised learning changes the role of the learner in the classroom from being a passive recipient of knowledge imparted by the teacher to becoming an active participant in co-constructing their learning. This active participation in the learning process is based on the understanding that students will be self-directed, motivated and highly engaged. Research and conversations recognise the benefits of personalised learning approaches for student motivation, and support to maximise learners’ potential which has resulted in enhanced learning outcomes, self-confidence and selfesteem for the learners.

The last decade has witnessed an escalated trend in the amount of published data on both the organisational and personal front. This includes large organisational datasets to provide performance indicators, and access to personal data through different social networking sites. This trend has also carried innumerable opportunities and promises to improvise, measure, and evaluate the learning processes in educational settings (Retalis et al, 2006; Johnson et al, 2011). The term ‘learning analytics’ in educational settings is used quite often in the monitoring and assessment of students’ progress, the prediction of future performance, and the identification of potential problem areas in learning using student performance data (Johnson et al, 2011).

Academic progress, attitudes, and behaviour of the learners are now tracked using large datasets in educational settings that enable identifying sources of assistance and interpreting learners’ context. This application of learning analytics has grown rapidly in educational settings in the last decade, a notable example being the focus on research in personalising learning environments to improve the quality and efficiency of the learning processes (Manouselis et al, 2010).

Research and new technological developments provide innumerable opportunities for offering personalised instruction in present times. The significant progress made by the adaptive learning models in education in recent times makes it possible to personalise instruction and encourage self-paced and self-directed learning. The adaptive learning system supports the personalised learning process. The term adaptive is defined as ‘able to change, when necessary, in order to deal with different situations’ (Fröschl, 2005: 11). The adaptive learning system is tailored to facilitate interaction between learners and computers. This provides individual tutoring and support for learners, an area which can be challenging for the teachers when there are large numbers of students in a classroom and an enormous number of administrative tasks for teachers to complete. An adaptive learning platform identifies student strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in knowledge through diagnostic tests, formative assessment and structures appropriate for support and scaffolding. This results in effective support for teachers as data analytics provide insight into individual students’ progress which in turn enables teachers to adjust feedback, assignments and teaching content in order to extend more effective and personalised support. It also offers the potential to play a key role in addressing educational access issues in regions where there is a paucity of qualified staff or in scenarios such as the recent pandemic.

The recent pandemic and shift to online learning has further reinforced the necessity to consider a broad range of learning characteristics, such as student

autonomy, self-regulation, motivation and active engagement, which is feasible in a technologically personalised learning environment. However, several factors obstruct the implementation of personalised approaches, some of which include access to adequate technology infrastructure, the readiness of the teachers, student motivation and engagement, access and inequalities in learning opportunities, quality content, student-friendly instructional aids, online assessment models and tools for customising assessment tasks in relation to the ability of the learners. As Anthony Seldon

and OladimejiAbidoye have remarked in their book titled The Fourth Education Revolution, Will Artificial Intelligence Liberate or Infantilize Humanity?, ‘The “Holy Grail” would be for every student to have the benefits of personalised tuition for at least part of every lesson, which would ensure that their own needs were individually addressed, and then to have time for group work, when the student can offer contributions and listen to those made by fellow students and by the teacher’ (2018: 73).

While at implementation level, technology-enhanced personalised learning may be obstructed due to contextual challenges, lack of affordances, infrastructural and resource support and absence of initiatives, yet it offers promising potential and an encouraging opportunity to augment learning environments. While envisioning the implementation of these new approaches, the ethical implications of the governance of personal data must be carefully considered by different stakeholders. ◆

Naaz Kirmani is an International Baccalaureate Educator and full-time PhD student at the University of Bath, UK. ✉ nfkk20@bath.ac.uk

• Fröschl C (2005) User modeling and user profiling in adaptive e-learning systems. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238685545_ User_Modeling_and_User_Profiling_in_Adaptive_E-learning_Systems [Accessed 9 November 2022].

• Johnson L, Smith R, Willis H, Levine A and Haywood K (2010) The 2011 Horizon Report. New Media Consortium. Available from: https://eric. ed.gov/?id=ED515956 [Accessed 8 November 2022].

• Manouselis N, Drachsler H, Vuorikari R, Hummel H and Koper R (2010) Recommender Systems in technology enhanced learning. Recommender Systems Handbook. Available from: https://www.ise.bgu.ac.il/faculty/liorr/ recsyshb/chLearning.pdf [Accessed 6 December 2022].

• Retalis S, Papasalouros A, Psaromilogkos Y, Siscos S and Kargidis T (2006) Towards networked learning analytics – a concept and a tool. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291980910_Towards_networked_ learning_analytics_-_A_concept_and_a_tool [Accessed 24 November 2022].

• Seldon A and Abidoye O (2018) The Fourth Education Revolution – Will Artificial Intelligence Liberate or Infantilise Humanity? Buckingham: University of Buckingham Press.

By John Haakon Gould

By John Haakon Gould

The IB Diploma curriculum comprises 6 subject groups, along with the Extended Essay (EE), Theory of Knowledge (TOK), and Creativity, Activity, Service (CAS): three elements collectively known as ‘The Core’. A dictionary definition of ‘core’ is the part of something that is central to its existence or character. It is clear throughout the programme’s standards and practices, as well as subject briefs, that the IB intends for these core elements to be seamlessly integrated for students to ultimately fulfill the broader IB mission of ‘developing inquiring, knowledgeable, and caring learners who help to create a better and more peaceful world’.

This article will focus on CAS, and its process of self-discovery that helps students counterbalance academic rigor with personal and interpersonal

growth across three ‘strands’. Students will use their creativity to produce an interpretative or original product (Creativity), engage in physical activity to cultivate healthy habits (Activity), and meaningfully collaborate with their communities to effect positive change (Service). Additional guidance is also given on how students may demonstrate the intended learning outcomes.

At Shanghai Community International School (SCIS), CAS is the culmination of a student’s experiential learning journey through the growing and robust programs of Action (IB Primary Years Programme) and Service As Action (IB Middle Years Programme). These foundations include our approach of Flexible Frameworks for Service Learning, as described in the Spring 2022 issue of this magazine.

Still, the purpose of CAS runs deeper. While the IB provides overall guidance as to the ‘aims’ and ‘nature’ of the program, each individual student ultimately

develops their own ‘Why’. In this article we’ll look more closely at how purpose is developed, using subheadings in red and verbatim quotes that arise from SCIS CAS student input, and paying close attention to how each of the seven intended outcomes (in green) may be achieved.

As stated by John Dewey, ‘We don’t learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience’. Before the audible collective groan of uploading to a Learning Management System (LMS), or quantitative inquiries like ‘How many do I need?’, this is about personalizing the process. Knowing oneself as a person with clear areas of strength and progress is a critical beginning point in CAS. Ji Yun was not only conscious of her linguistic and artistic talents for her project that coincided with her interest in Arts Therapy, but she also demonstrated

openness and vulnerability in sharing her original or cover poetry and music with others through videos and a social media account: ‘I developed my guitar and piano skills. I analyzed lyrics and a range of prose. I explored blending Korean and English into my creations. The comments and feedback motivated me to practice and improve, and overall had me deeply reflect on my identity and whether I live a life of “love”, which is the most important value for me.’

During students’ formative years, adults in their lives may make the majority of day-to-day decisions. It’s also a time when their identities are malleable and fluid. Demonstrating the ability to initiate and plan a CAS experience comes with its own set of obstacles. For larger projects, being able to recognize the benefits of working collaboratively is a way to address this range of challenges. ‘Our CAS project involved directly working with World Champion Boxer Michele Aboro’, a group of students said. ‘It was incredible to arrange an event for our community centered on gender equality, which included a movie discussion, meditation session, and basic boxing fundamentals. We learned a lot about event planning. When it came to marketing or agenda creation, we needed to draw on each other’s skills. We needed to communicate while avoiding micromanagement. Finally, it was about leaving room for spontaneity, as here is where memorable moments happen.’

‘CAS is about harmony’, says Noemie. That word, harmony, is profound and has multiple meanings across cultures and fields. The concept of various parts bringing wholeness can be considered as a significant revelation. ‘All three strands contain skills that are developed

in different ways. Whether it’s the freedom of flowing creativity, engaging in social responsibility, or the endorphins from physical movement; this balance is important.’ In terms of balance across the strands, each student’s portfolio may seem different. However, one unifying goal is the ability to demonstrate commitment and perseverance in whatever experiences are undertaken. ‘Setting goals, tracking progress, and action planning

required dedication. Managing my time became an area of growth as I worked on how to balance my passion project of developing a clothing brand, taking part in sports teams, and attending servicerelated conferences, among other things.’

Trust the students. Building opportunities for their voices to be heard can instill confidence and strengthen the community. Sharing experience of transition can be an especially opportune time for a collective reflection on how challenges have been undertaken, and new skills were developed in the process. ‘Although we’ve only experienced one year in the DP, our CAS Project was to directly interact with the Grade 10’s and share our personal stories’, Ashika and Yee Shin begin. ‘We wanted it to be practical, but also give the message across that as students, we’re always looking out for one another. Create that bond’. The planning ►

Sharing experience of transition can be an especially opportune time for a collective reflection on how challenges have been undertaken, and new skills were developed in the process.

of this experience was a way for students, coordinators, and teachers to collaborate in a meaningful way.

Mental health is undeniably a global concern; nonetheless, one could wonder how we might connect with it in an honest and meaningful way. At the April 2023 ACAMIS Spring Leadership Conference, keynote speaker Dr Jane Larson (Executive Director of the Council of International Schools) underlined the importance of education for wellbeing and flourishing by citing substantial research. She also asked how schools include student voice.

‘This topic has always been important, especially for young people. The pandemic brought the importance of this issue to the forefront even more’, states Suhani C. It became clear that a network was vital, but what objectives would it serve? She continues by saying ‘Triple A, a student mental health group initiative, really started as a way to connect; not only with each other – but also ourselves. It’s grown into a team of 25 student ambassadors

from all over the world. Incrementally, we’ve begun to pilot smaller projects at our own schools and report to each other the struggles and successes that we’ve faced’.

We are curious to see how this legacy project evolves, whether through collaboration with ongoing whole-school programs like #SCISDragonfit or by providing a safe space for dialogue.

In a recent TES Article the IB Director General, Olli-Pekka Heinonen, states ‘International schools can play a big role in solving global problems – but to wield this power they must embed themselves in their local culture ... Acknowledge the value of each individual, and respect that we are all equal in our uniqueness ... Learn the richness of different views in making better decisions.’ One should also note that direct service, including volunteering, brings about a myriad of ethical choices and decisions. While mistakes may occur and are learning opportunities in and of themselves, we at SCIS take pride in modeling what

this means in terms of reducing harm in international school service learning. Creating a school culture of service and international mindedness has been lengthy, incremental, and intentional. Before externalizing in the community, there is an emphasis on analyzing impact and action on campus. A recent community connection with a local Chinese School has placed cultural context in the center when carrying out a language exchange. ‘Power and privilege are factors to consider if you’re going to volunteer’, the students concur. ‘These are significant areas. Also, what drives you? Are you helping others out of a selfless motive?’

This period in a high schooler’s life can be stressful to say the least. It cannot be overstated that CAS is also supposed to be fun. Catherine Price, a prominent lecturer and science journalist, defines fun as ‘a feeling – not an activity ... It is the junction of playfulness, connection, and flow ... One must eliminate distractions, increase face-to-face human interaction, and make it a priority.’ Advisors can remind students of this not only informally, but also at interviews, throughout the program. The interviews themselves can be framed in ways that inspire conversation, such as choice boards, presentations, and ‘socials’ to reflect on both the achievement of the outcomes and the joy experienced. CAS requires collective effort in supporting the individual’s journey of becoming a well-rounded citizen of tomorrow. ◆

• Heinonen O-P (2023) Why international schools must embrace their local communities. TES. 25 January 2023. https://www.tes. com/magazine/analysis/specialist-sector/ how-international-schools-embrace-localcommunities-baccalaureate

• Price C (2022) Why having fun is the secret to a healthier life. TED Talk. https://www.ted.com/ talks/catherine_price_why_having_fun_is_the_ secret_to_a_healthier_life/no-comments

Discover the power of White Rose Education, your go-to resource for all your maths and science curriculum resources and training at primary and secondary level. Explore effective teaching strategies crafted by specialist teachers. Engage, challenge, and inspire your students with our innovative approaches.

Access a comprehensive library of British curriculum-aligned materials, including schemes of learning, worksheets, and teaching slides.

Enhance your skills with expert-led training through multiple mediums; including faceto-face training, webinars and our on-demand videos which help you perfect your skills in the classroom.

“High quality and ready to use in the classroom” Lorenza Elli, Primary Maths Specialist, Concordia School, Paris.

What motivates us to adapt or differentiate learning to create equity in our classrooms?

The inclusive education context that we experience every day is likely to differ across the diverse contexts of international schools. As national systems and accrediting agencies seek policy and practice that promote diversity, equity and justice in education, inclusion is the term that we use to describe and foster this practice.