THE MAGAZINE FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATORS IN PARTNERSHIP WITH International SCHOOL MAGAZINE Spring 2024 | schoolmanagementplus.com MANAGEMENT plus SCHOOL PART OF ADMISSIONS GOVERNORS FINANCE HEADS DEVELOPMENT The Importance of Resilience

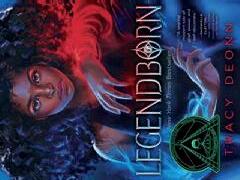

Support students' emotional wellbeing with ebooks and audiobooks

It has never been easier to give students a way to discover their love of reading. Give your school the power to deliver the right books to every student with the award-winning Sora digital reading platform.

With Sora, you can handpick titles from the industry's best catalogue of ebooks and audiobooks for students at every grade level and across all subjects to meet their reading and learning needs.

And it’s 100% digital. So books can be read anytime, anywhere, on every device.

Visit DiscoverSora.com/global to see why over 61,000 schools have partnered with Sora.

Mary Hayden

Jeff Thompson editor@is-mag.com www.is-mag.com

Steve Spriggs steve@williamclarence.com

259241 bryony.morris@fellowsmedia.com

Jacob Holmes

jacob.holmes@fellowsmedia.com 01242 259249

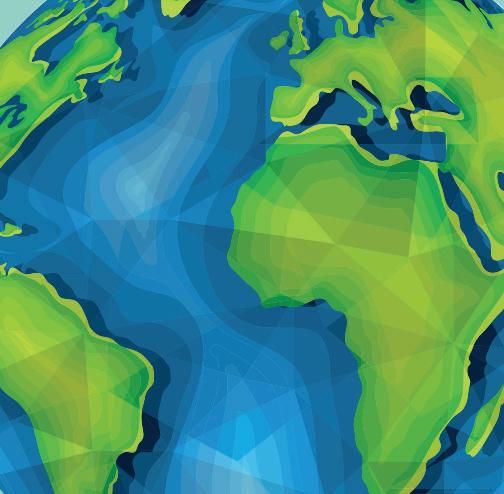

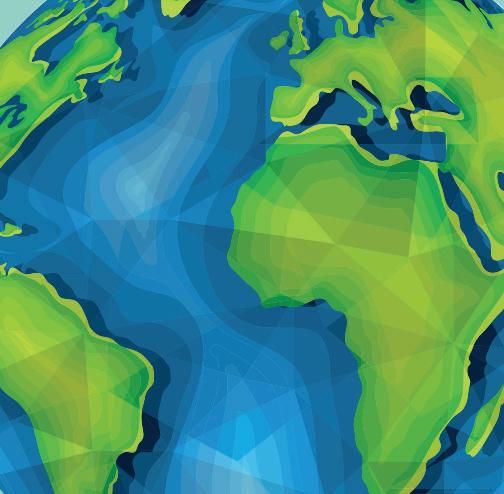

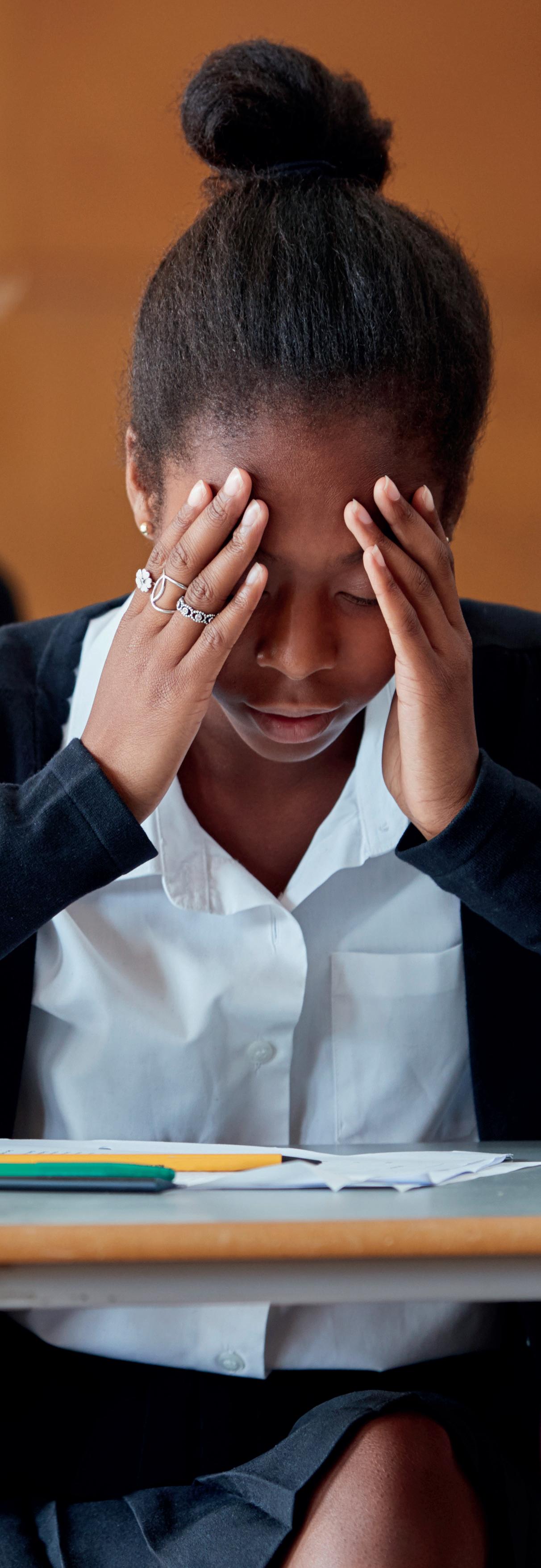

Contents 22 Intelligence on Demand. How AI Challenges Educators Paul Juscha From the Schools 26 Educated and Educators International School of Billund 32 Navigating Motherhood in an International School: Striking a Balance amid Cultural Differences Heather Meyer and Hailey Meyer 34 The Importance of Resilience Kieran Pearson 36 Beyond Character Education: Integrating Skills from the Inner Development Goals into the English Classroom Allison Finn Yemez Book review 39 Teachers! How Not to Kill the Spirit in Your ADHD Kids. Instead, Understand their Brains and Turbo-charge our Future Leaders & Winners. By Sarah Templeton Reviewed by Sally Hewlett 5 Changing Times and Moving On Mary Hayden and Jeff Thompson Features 6 What’s in a Name? ‘Artificial Intelligence’ is a contentious term and its future in international schools should be too Callum Philbin 9 A Plea for Courage in International Education Leadership Stephen Codrington 12 Creating a Culture of Professional Growth and Inquiry Ann Lautrette Leading, Teaching and Learning 14 Building Successful School Culture Part 2: The School Professional Culture Arena George Scorgie 16 Reflections on Learning and Teaching: Who Are School Assessments Really For? Cherry Atkinson 19 Resisting the ‘Best Possible Self’ Narrative Within a Teacher Education Programme Natalie Shaw On the Cover The Importance of Resilience Kieran Pearson Page 34 34 The Importance of Resilience 16 Reflections on Learning and Teaching THE MAGAZINE FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATORS EDITORS

DIRECTOR

MANAGING

& PRINT

Media Ltd

ADVERTISING

DESIGN

Fellows

The Gallery, Southam Lane, Cheltenham GL52 3PB 01242

part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means. International School is an independent magazine. The views expressed in signed articles do not necessarily represent those of the magazine. The magazine cannot accept any responsibility for products and services advertised within it. Part of the Independent School Management Plus Group schoolmanagementplus.com Spring 2024 International School 36 Beyond Character Education Spring 2024 | International School | 3

No

CPSQ Measure what matters for academic success

For students aged 14 to 19

The Cambridge Personal Styles Questionnaire (CPSQ) provides insight into how students approach tasks and relate to others: their ‘personal styles’. Research has found these styles contribute to educational progress and work effectiveness.

Instant insight

Gain invaluable understanding of your students in just one lesson.

Focus and tailor

Personalise student mentoring programmes.

See a more holistic picture

Get additional context to students’ academic performance.

Build students’ self-awareness

Motivate student interest in personal development.

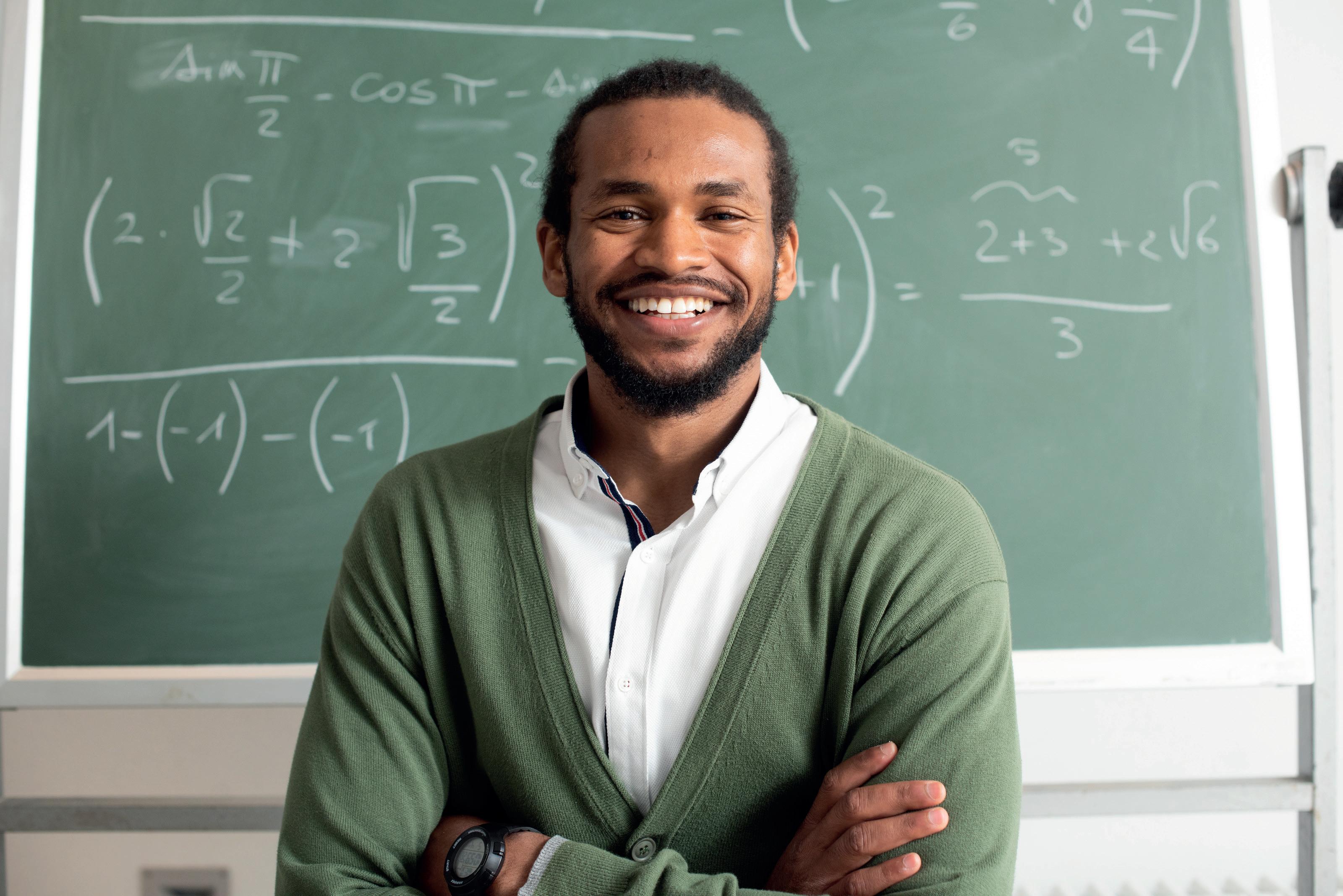

www.cem.org/cpsq

Understand hidden barriers

Identify students in need of extra support.

Scan for more information

Special

Changing Times and Moving On

Mary Hayden and Je Thompson

In the ten years since we began editing International School magazine, with William Clarence from 2020 and for the previous seven years with John Catt Educational, the international school context in which the magazine is set has seen many changes: not only in number, but notably in nature. Ten years ago, it was becoming clear that the growth in this sector was not only due to an increase in numbers of international schools of the type with which many had previously been familiar: largely catering for globally-mobile expatriate professional families for whom schools in the national system to which they temporarily relocated were not suitable for their children (often for reasons of language). As was becoming increasingly evident the growth was also, and perhaps majorly, in numbers of a different type of international school all together: those intended for the children of host country national families for whom, in some contexts, an English-medium education leading to internationallyrecognised pre-university qualifications could be perceived as providing a competitive edge, and a potential passport to prestigious western universities and well-remunerated employment in the global labour market.

The oft-cited ISC Research (2018) statistic of a shift from 1989 – when international school student populations constituted approximately 80% expatriates and 20% host country nationals – to a complete aboutturn by 2018 provides a clear illustration of just how much the sector has been changing, with more recent growth appearing to continue in the same direction. Our own proposal in 2013 of a rather unimaginatively labelled A, B, C categorisation of international schools (‘traditional’ schools catering for expatriates, ideologically-

...we wish to express our gratitude to all we have worked with for their encouragement and support

driven schools such as the United World Colleges, and more recently emerging schools catering for host country nationals respectively) was out of date almost as soon as it was published, with further subsets of types arising in the short period since. The so-called Chinese ‘internationalised’ schools, and the ‘satellite’ schools/ colleges appearing around the world as off-shoots of prestigious and well-established schools particularly in the UK and North America, are just two of the new and interesting forms of international school in this increasingly recognised form of education, which has also spawned

a new field of educational research.

Reference

No less significant has been the changing wider context in which international schools operate. In just ten years there have been enormous changes in the range of issues to which international schools are needing to respond, including but not limited to the climate emergency, the impact of colonisation and moves to decolonise the education process, increased tensions and war in a number of flashpoints globally, mass immigration, huge growth in the use of social media, the very notion of truth and its representation – and, not least, the opportunities and threats presented by Artificial Intelligence.

As our time as joint editors of International School comes to an end, with the decision by William Clarence to take the magazine forward in a different format, we wish to express our gratitude to all we have worked with for their encouragement and support over the past decade. Throughout the shifting sands of those years, we have been privileged to work with large numbers of international school teachers, leaders and others with interests in this area who have been willing to share examples of good practice, ideas for change, reflections on the challenges of the day, and provocative proposals to stimulate debate, as well as providing helpful feedback and suggestions. It has also been our pleasure to work with publishing colleagues who have brought their expertise to the production of a high quality and attractive publication that encourages readers to take time to learn from the ideas and experiences of others. We are confident that International School in its new iteration will continue to attract high quality articles from teachers and leaders in international schools worldwide. As we move forward into increasingly uncertain times, the sharing of ideas and providing of mutual support for those facing similar challenges will be no less important than it has been to date. We wish our colleagues at William Clarence every success in the development of International School as a forum for the sharing of ideas, discussion and debate in this important context. ◆

• ISC Research (2018) International School Market Research and Trends. Faringdon: ISC Research.

• Hayden M C and J J Thompson (2013) International Schools: antecedents, current issues and metaphors for the future, in R Pearce (ed) International Education and Schools: moving beyond the first 40 years, London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Special

Spring 2024 | International School | 5

What’s in a name?

‘Artificial Intelligence’ is a contentious term, and its future in international schools should be too

By Callum Philbin

International schools are bringing in responsive use policies around ‘Artificial Intelligence’ faster than ChatGPT can write a student’s essay or the teacher’s feedback. But you don’t need a largelanguage model (LLM) to produce homogenous platitudes; schools are lining up to present policies and frameworks that all use similar rhetoric: AI can enhance teaching and learning, we have serious misgivings, but you lead and we follow because what else can we do?

None of this is to dismiss the difficult circumstances that students, teachers and school leaders find themselves in. LLM-based technologies do challenge our education systems and ask fundamental questions of what we do as educators inside and outside of the classroom. Fundamental questions that require our leadership, like: what is intelligence? When we tease out a question like that, we might not feel as comfortable describing the current manifestations of ‘generative-AI’ in our school policies as ‘intelligent’, or even ‘artificial’ for that matter.

The concept of artificial beings with intelligence or consciousness has existed in human culture for thousands of years across various mythologies. However, our contemporary use of the term originates from computer scientist John McCarthy’s 1956 summer school in Dartmouth College, USA (Council of Europe, 2023). He developed the term to distance himself from Norbert Weiner’s neologism of ‘cybernetics’ because, as anyone familiar with academia knows, pettiness between researchers is boundless, and a new showy term is a great way to get funding. Fast forward through AI summers and winters (periods when researchers get funding and periods when they don’t) to our

contemporary moment of advances in robotics, speech and facial recognition, and natural language processing. The techniques and algorithms that led to developments in machine learning and deep learning for these breakthroughs in the 2010s didn’t come from new ‘changemakers’ and ‘thought leaders’, but from research in the 1980s, the change being that companies now had massive amounts of data to draw from based on the prevalent surveillance model of many modern technology companies, as well as the new infrastructure (data centers) to process it (Crawford, 2021). The advent of LLMs is

just as debatable. Human intelligence is a vast and complex concept, whereas the ‘intelligence’ in AI is premised on statistical logic reinforced with human training. The original conception of AI from McCarthy viewed computers as like minds, and vice versa. If you read Freud, you will see him comparing humans to steam engines. The problem is bodies are not steam engines, and minds are not computers. Intelligence has many definitions to capture its complexity, but it usually encompasses emotional understanding. The truth is that ‘artificial intelligence’ is nothing like human intelligence. This is not to say pattern-

Educators are the true disruptors.

The future of our planet depends on that...

a part of this story, the technology behind the sub-field of ‘generative-AI’, software that creates text, images and computer code that mimic some human capabilities (Visual Storytelling Team and Murgia, 2023).

Of course, LLMs find patterns and present text to mimic human capabilities based on data appropriated from real human beings. Writers, artists, musicians, academics, and other professionals and creatives have produced text from their own labour that is then offered to users of LLMs through the statistical, pattern-finding machine (some trained with outsourced labour in Kenya at less than $2 dollars an hour). ‘Non-artificial’ or ‘pattern-matching’ intelligence does not have the same mysticism, but it is at least accurate. The ‘intelligence’ part is

matching and statistical prediction are not useful. It is to say that the term has a shaky premise and brings idealised notions that can hide what it does and its ramifications for the world. Thankfully, international educators have a deep understanding of the complexities of intelligence, and they are well represented in the focus on a strengths-based model within the growing neurodiversity movement.

The use of algorithms is not a new phenomenon in international education. When the International Baccalaureate cancelled its final examinations because of the pandemic, algorithms were used to ‘predict’ results (Asher-Schapiro, 2020) with at best … mixed results. Teacher-estimated grades, student assignment scores and historical results were fed into an opaque

6 | International School | Spring 2024 Features

statistical formula to determine final grades for students. Gulson et al’s Algorithms of Education (2022) offers an extensive overview of how algorithms and AI have transformed educational governance around the world through datafication, the process of ascertaining quantitative data about students to measure educational outcomes. New modes of seeing, but also new modes of educational accountability and, at times, performativity. All conversations about AI use in schools need to begin with transparent and difficult conversations about how algorithms are used in the present.

None of these criticisms are to say that new technologies should not be used at all. The value of creating opportunities for inclusive learning through augmentative communication tools or for tailoring content for individual needs and abilities is clear. But to explore how (and when and why) we use pattern-matching software or other forms of machine learning or deep learning, we need to start by confronting the AI hype and offering our own vision for the future, not the one offered by ‘Open for business AI’. Starting with the technology and its role in enhancing learning would be the wrong place to start; better to begin with what we want to develop as educators, and how we can confront our global challenges.

Stephen Taylor’s article in the Summer 2023 edition of this magazine called on educators and students to be ‘explorers’, but from the common techno-optimist

premise that an ‘AI future’ equals human progress in efficiency, economic growth and well-being (p35). He acknowledges ‘challenges’, but the more dystopian concerns of AI being contrary to human values seem to be missing. I would rather we were ‘leaders’ instead of ‘explorers’, challenging the narratives around AI and reimagining what schools can be with our own vision for transforming the world.

Mark Weiser wrote that ‘the most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it’ (1991). As international educators we should confront the deception of the name AI and its premise before these technologies disappear into the realities of our schools.

Educators are the true disruptors. The future of our planet depends on that: whether it be confronting inequalities, war or climate change. Leave tech visionaries to disrupt everything except the market and our deep global inequities. Let’s ask uncomfortable questions about if, and if so to what extent, we want to embed technologies in the classroom. Let’s work with students, and together play a leading role in the future of international schools, which will probably have less to do with technological integration, and more to do with the major societal transformations necessary for a sustainable future. Let’s demystify AI, see it as contentious and, as educators, seize our own vision for the future. ◆

References

• Asher-Schapiro A (2020) Global Exam Grading Algorithm Under Fire for Suspected Bias. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/usglobal-tech-education-analysis-trfn/global-examgrading-algorithm-under-fire-for-suspected-biasidUSKCN24M29L

• Council of Europe (2024) History of Artificial Intelligence. Available at: https://www.coe.int/en/ web/artificial-intelligence/history-of-ai

• Crawford K (2022) Atlas of AI. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

• Gulson K N, Sellar S and Webb P T (2022) Algorithms of Education. How Datafication and Artificial Intelligence Shape Policy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

• Taylor S (2023) AI in Education: We are all Explorers. International School. Summer 23 Edition. Available at: https://www. schoolmanagementplus.com/publications/ international-school-magazine/internationalschool-magazine-summer-2023/

• Visual Storytelling Team and Murgia M (2023) Generative AI Exists Because of the Transformer. Financial Times. 12 September 2023. Available at: https://ig.ft.com/generative-ai/

• Weiser M (1991) The Computer for the 21st Century. Scientific American. 265(3): 94. Available from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/ article/the-computer-for-the-21st-century/

Dr Callum Philbin is a Lecturer and Researcher in International Education with International Teacher Education, NHL Stenden University of Applied Sciences in The Netherlands.

✉ callum.philbin@gmail.com

Spring 2024 | International School | 7

Safer School, Better Behaviour

With CPI training you can:

Empower educators

Support student success

Promote emotional wellbeing

Improve behaviour response

Scan or click QR Code to learn more about our training programmes.

Classroom Culture™ Training

Verbal Intervention™ Training

Breaking Up Fights™ Training

Safety Intervention™ Training

Schedule a conversation with a CPI representative today to learn how you can build a positive school climate.

Phone: + 44 (0) 161 929 9777

Email: C ContactUs@crisisprevention.com

8 | International School | Spring 2024 Features

FOLLOW US ON CPI International Headquarters Building 2 Brooklands Place • Brooklands Road • Sale • Manchester • M33 3SD • United Kingdom © 2024 CPI. All rights reserved. pivotal behaviour training

A Plea for Courage in International Education Leadership

by Stephen Codrington

For at least 2,500 years, courage has been seen as a virtue. The ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu is said to have written ‘Because of great love, one is courageous’. At about the same time, the famous Greek philosopher, Aristotle, viewed courage as the marker of moral excellence, noting that it was the virtue which moderates our instincts toward recklessness on one hand and cowardice on the other. Aristotle believed that a courageous person fears only those things that are worthy of fear. In other words, courage means discerning and thus knowing what to fear, and then responding appropriately to that fear.

The brilliant British TV comedy series ‘Yes Minister’ took a different, much more pragmatic and cynical view of courage. When Sir Humphrey Appleby (as Permanent Secretary for the Department of Administrative Affairs) thought his minister was about to make a big error, he would raise one eyebrow and say ‘that would be a courageous decision, minister’. In Sir Humphrey Appleby’s world, courage was not a virtue; it was a severe risk.

It seems that courage may be going out of fashion in international education. At face value, schools seemed far more innovative and open to courageous experimentation in the 1960s, 1970s

and 1980s. These days the general rule seems to be to play safe, achieving the often-mediocre outcomes set by external bureaucrats which are measured by standardised testing and dreary, excessively quantitative questionnaires whose principal justification is so-called ‘accountability’. At its best, international school accreditation has the potential to encourage creativity, and yet according to many school leaders with whom I work, it more commonly seems to direct schools towards risk-averse conservative compliance that is more directed to please lawyers than parents, students, and teachers.

Of course, courage should not be reckless; it needs to be based on sound research and experience. One of my ‘heroes’ in education is the brilliant German educator, Kurt Hahn, who was instrumental in establishing the United World Colleges, the Duke of Edinburgh Award, Outward Bound, Round Square, Gordonstoun School in Scotland, Schule Schloss Salem in Germany (in partnership with Prince Max von Baden) and, indirectly, the International Baccalaureate (IB).

In a speech in 1965, Kurt Hahn spoke about achieving the right balance between sound experience and experimentation in these words: ‘To make my

Spring 2024 | International School | 9 Features

▲

meaning clearer I will recall a conversation, which the late founder – the real founder of the Salem School –Prince Max of Baden had with a visitor. His enthusiastic guest asked him the following question: ‘what are you proudest of in your beautiful schools?’ He said, ‘I am proudest of the fact that if you go the length and breadth of the schools, you will find nothing original in them. It is stolen from everywhere, from the British public schools (you call them private schools), from the Boy Scouts, from Plato, from Goethe’. Then the enthusiastic guest turned to him and said, ‘But oughtn’t you to aim at being original?’ Then Prince Max rather abruptly answered, ‘Well, you know, it is in education like in medicine, you must harvest the wisdom of the thousand years. If you ever came across a surgeon who wants to take out your appendix in the most original manner possible, I would strongly advise you to go to another surgeon.’ (From Kurt Hahn’s Address at the Founding Day Ceremony of the Athenian School, 21 November 1965 Danville, California).

One of Kurt Hahn’s (many) enduring legacies is the global network of 18 United World Colleges (UWCs), regarded by many as the gold standard of international education today. The UWC movement was established in 1962 with the opening of Atlantic College in Wales, initially to build peace at the height of the Cold War by bringing together 16-18 year olds from around the world (and from both sides of the Iron Curtain) to live together and study together, and to build bridges of understanding. The concept was arguably more than courageous – it was audacious! The selection of students was (and still is) conducted on the basis of merit, with the majority receiving either full or partial scholarships raised through National Committees worldwide.

It is difficult to find at work today examples of the type of courage that established the UWCs – the courage to build a world-wide network of schools based on a set of philosophical ideals, independent of students’ ability to pay. There are rare exceptions, and their rarity makes them notable. For example, a remarkable multicultural school where I serve as Board Chair, Djarragun College in Australia, was established more recently according to an altruistic philosophy not unlike that of the UWCs. Seeking to overcome discrimination, lack of opportunity, disempowerment, unemployment and erosion of culture, the school provides subsidised education for disadvantaged Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students from some 55 different First Nations. Many of these students have no alternative access to education because of their remote location, poverty, family situations, violence or, quite commonly, a combination of several (or all) of these factors.

For me as an educator, it is disappointing that schools such as the United World Colleges or Djarragun College are such rare exceptions in today’s educational world. In my eyes, they are role models for what international education should be – visionary, courage-based, beacons of hope and opportunity that transform young lives and their communities.

Literature suggests that courage is required of soldiers, athletes, corporate leaders, and (notwithstanding Sir Humphrey Appleby’s machinations) a few rare politicians. However, courage is rarely mentioned as a positive attribute of school leaders or their governing boards. This seems to be an absurd omission. It is hard to imagine any school leader or board getting through a month, let alone a year, without having to make decisions that

...by playing it safe, by unconsciously giving away our power, by dimming our radiance, by not recognising there is always so much more waiting for us on the other side of fear’.

Features

demand courage. More often than not, however, such decision-making requires the courage to make important but necessary decisions that will distress some constituents. In some extreme cases (which are increasing in frequency in some places), it may include the courage to deal with physical violence, verbal attacks, character assassination, social media rumour-mongering, or direct challenges to the school’s essential mission, purpose or identity. In the context of the host societies in which international schools operate, courage for school leaders and boards may also include standing up to societal pressures when these conflict with the school’s firm values position or mission.

It also takes immense courage to be humble, especially in multicultural environments where values and practices may conflict. This is especially so for those who lead international schools as they must find the courage to admit that they are not always right. Similarly, it takes courage for school board members to admit that they can’t always anticipate every possibility, that they can’t solve every problem, that they can’t control every variable, that they can’t always be congenial, and that they will make mistakes. It takes courage to admit these things to others, and even more courage to admit them to yourself.

In a 2020 article for Harvard Business School, Matt Gavin wrote ‘A deep and abiding sense of courage is a quality that separates good leaders from great ones. Research shows that professionals who demonstrate courage in the workplace not only perform at a higher level, but influence their peers to act with bravery and drive organizational success’. In my mind, this highlights the importance of school leaders and boards working effectively in close, creative, courageous partnership. Neither the United World Colleges nor Djarragun College could ever have become successful without close working relationships between governance and management, working together towards shared, unified goals with the courage to stay focussed on achieving their ambitious goals in the face of significant obstacles and powerful opposition.

Of course, irrespective of the amount of courage an individual possesses, not everyone is in the position of courageously starting an international network of schools or a school which focuses on closing the gap between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous communities. How, then, should a school leader (and the board) exercise courage as they guide the everyday operations of a typical international school? Some suggestions are as follows:

1. Lead passionately by example

Leaders are people that others follow. People follow leaders they respect, and respect flows from ‘walking the talk’. In other words, staff and students respect those who show servant leadership by only asking

others to do what they would be prepared to do themselves. Leading by example also requires passion if the leadership is to be effective. Passion flows easily when someone is committed to their objectives and believes sincerely in their importance. It follows from this that authenticity is required to lead by example and exude infectious passion.

2. Think strategically

Every action taken in a school – courageous or not – should be strategically coherent in enhancing the school’s mission (enduring purpose), vision (strategic priorities) and values (ethical position). A missiondriven strategic plan provides an excellent foundation for coherent, focussed, courageous decision-making.

3. Take ‘acceptable’ risks

The word ‘acceptable’ is not intended to be a weasel word here. Different school communities, school leaders and school boards vary in their risk appetites, whether the risk is financial, strategic, operational or philosophical. Courage means taking well-considered actions right up to the limit of risk acceptability, but not beyond – that is what is meant by ‘acceptable’ risks.

I love a quote by the US writer, Elaine Welteroth, in her 2019 book More than Enough: ‘I realised that if we aren’t vigilant, we can move through our entire lives feeling smaller than we actually are – by playing it safe, by unconsciously giving away our power, by dimming our radiance, by not recognising there is always so much more waiting for us on the other side of fear’. Those words – living on the other side of fear – would be a great motto for international school leaders and their boards as they work together to chart an exciting strategically-focussed future for the school in a way that honours its history, mission, purpose, vision, values, ethos, and philosophy. Courage is a not a legal requirement of school leadership or board governance, but it is an immense help in making leadership and governance more effective. ◆

References

•Gavin M (2020) 3 Examples of Courageous Leaders & Lessons You Can Learn from Them. Harvard Business School Online. 10 March 2020. Available from https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/ courageous-leaders

• Welteroth E (2019) More Than Enough: Claiming Space for Who You Are (No Matter What They Say). London: Ebury Press.

Stephen Codrington is Founder and President of Optimal School Governance, a specialist consultancy that supports school leaders and boards globally. He previously served as the Head of five IB schools in four countries over a period of 25 years.

✉ stephen@optimalschool.com

Spring 2024 | International School | 11 Features

Creating a Culture of Professional Growth and Inquiry

by Ann Lautrette

One of the simultaneous joys and frustrations of the teaching profession is that no-one really has the answer to what makes a perfect lesson, or what change will suddenly make every student reach their potential. There are many theories, and there are many professional development opportunities for teachers and schools on the hunt for that particular holy grail. Educational researchers, consultants and gurus bring much to understanding what makes great teaching and learning, but many teachers have a sense that these people are no longer really in the classroom, and are not under immediate pressure to bring the best out of themselves and their students in the face of a rapidly changing and increasingly unstable world.

Schools can take many approaches to professional development for teachers: from a top-down ‘we’re bringing in such and such an expert this week’, to a selfdesigned ‘I’m going to go on this course because I’m interested in x’ model. Both of these extremes, however, rely on an individual teacher learning something new, implementing a change in their practice, evaluating thoroughly the impact of that change, and determining whether to stick or twist. All with no real time to do it.

Practically, what happens is that a new initiative is touted by leadership or by an expert on a professional development day, teachers either roll their eyes and catch up on emails, or get excited in the moment, endeavour to try something new in their classroom on Monday, and forget all about it as soon as little Jonathan starts underlining his titles without a ruler …. again. Or, maybe the latest golden nugget makes it into the teacher’s practice and embeds itself there with no real evaluation of any data which shows if it is actually making a difference. Meaningful professional development starts with teachers themselves, but requires a strategic approach to creating a learning culture where teachers are safe to hypothesise, experiment, measure success, reflect, evaluate and plan new change. This cyclical professional inquiry model takes some time to build but results in rich conversations amongst colleagues, ownership of professional growth and development, and direct impact on student learning.

In Action – Context

Imagine a secondary school where the main strategic focus is assessment; specifically moving towards a culture where its students can be said to be

‘assessment-capable’. In simple terms, students know where they are, where they can go, and how to get there. If the school believes that this is the best way to help students achieve their potential and go on to a future in which they can evaluate their own strengths and assess their own needs, identify actions they can take and reflect on the success or otherwise of those actions, then it doesn’t make sense to see teacher professional development as a top-down influx of ‘expert’ initiatives restricted to an in-service day. Instead, the school can create a culture where teachers understand that they are the experts, in the privileged position of being able to test out what works to improve student learning in every single lesson. As a bonus, the school also moves away from the notion that performance management is an external evaluation of how well you are teaching in one given moment, and towards an evaluation of how well you are able to practise the business of teaching in a reflective cycle of inquiry into what has real impact.

So, how can a school make this change? What follows are my proposals for a sequence of steps to take.

Step 1: Ask ‘what do we expect from teachers in our school?’

Before teachers can be empowered to take meaningful control of their own professional learning and growth, the school needs a framework which essentially defines quality teaching and learning, as well as a strategic direction.

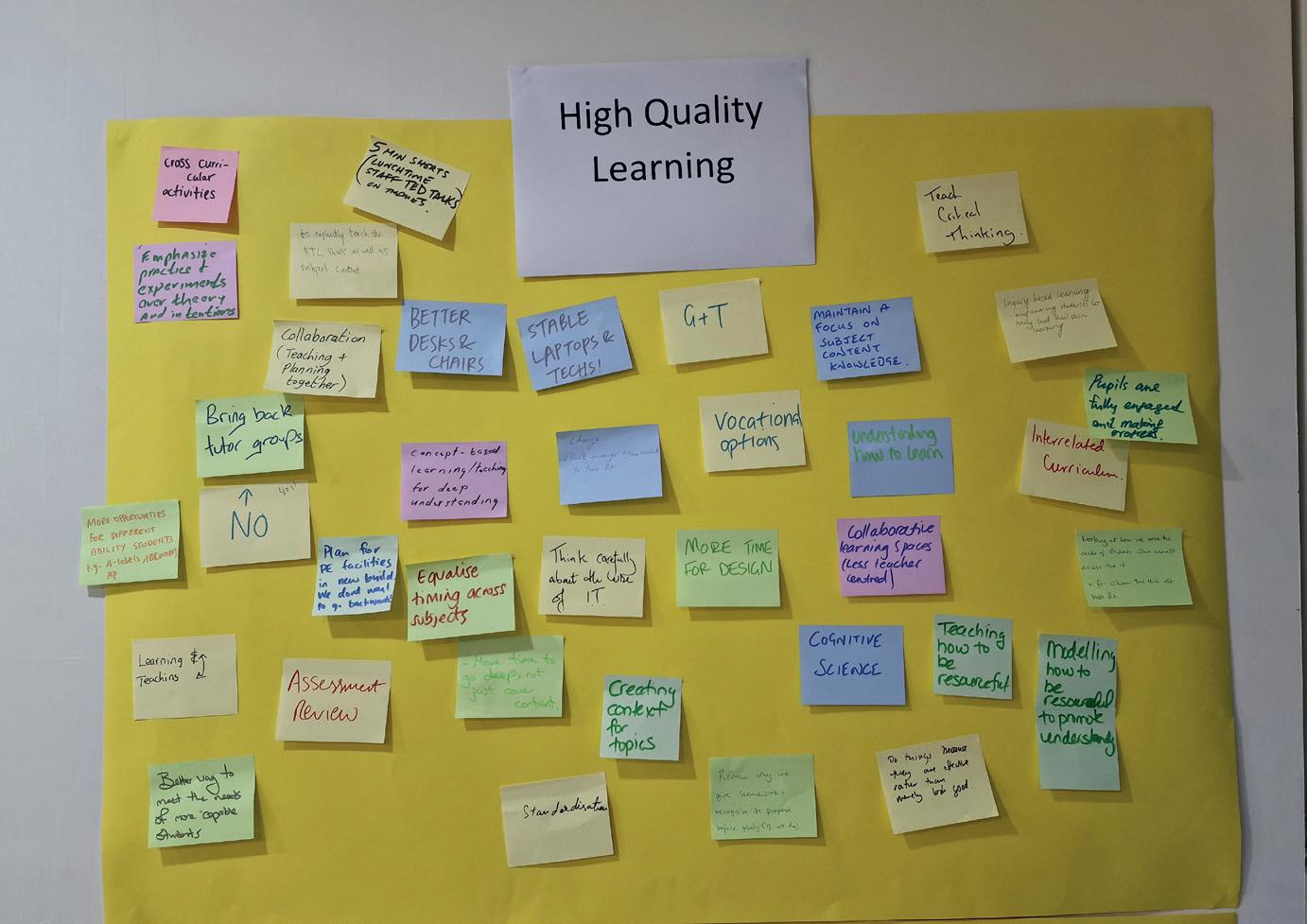

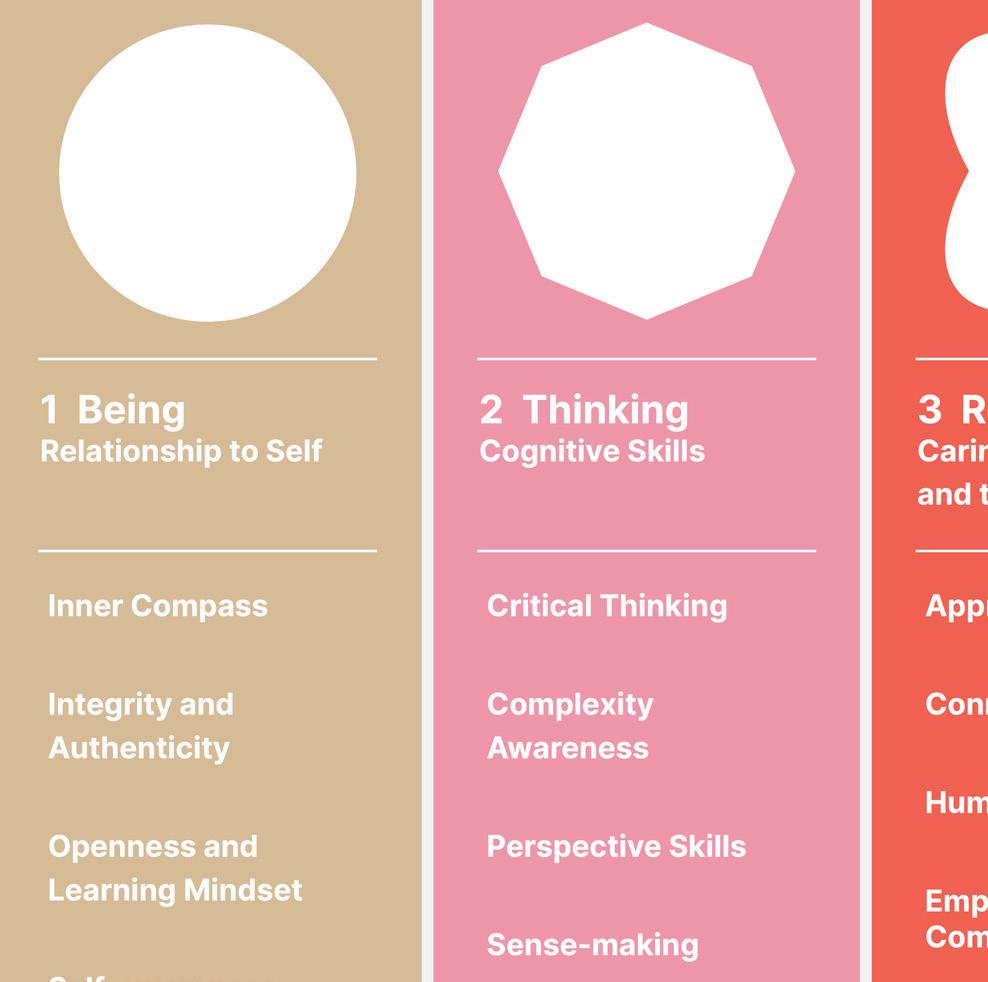

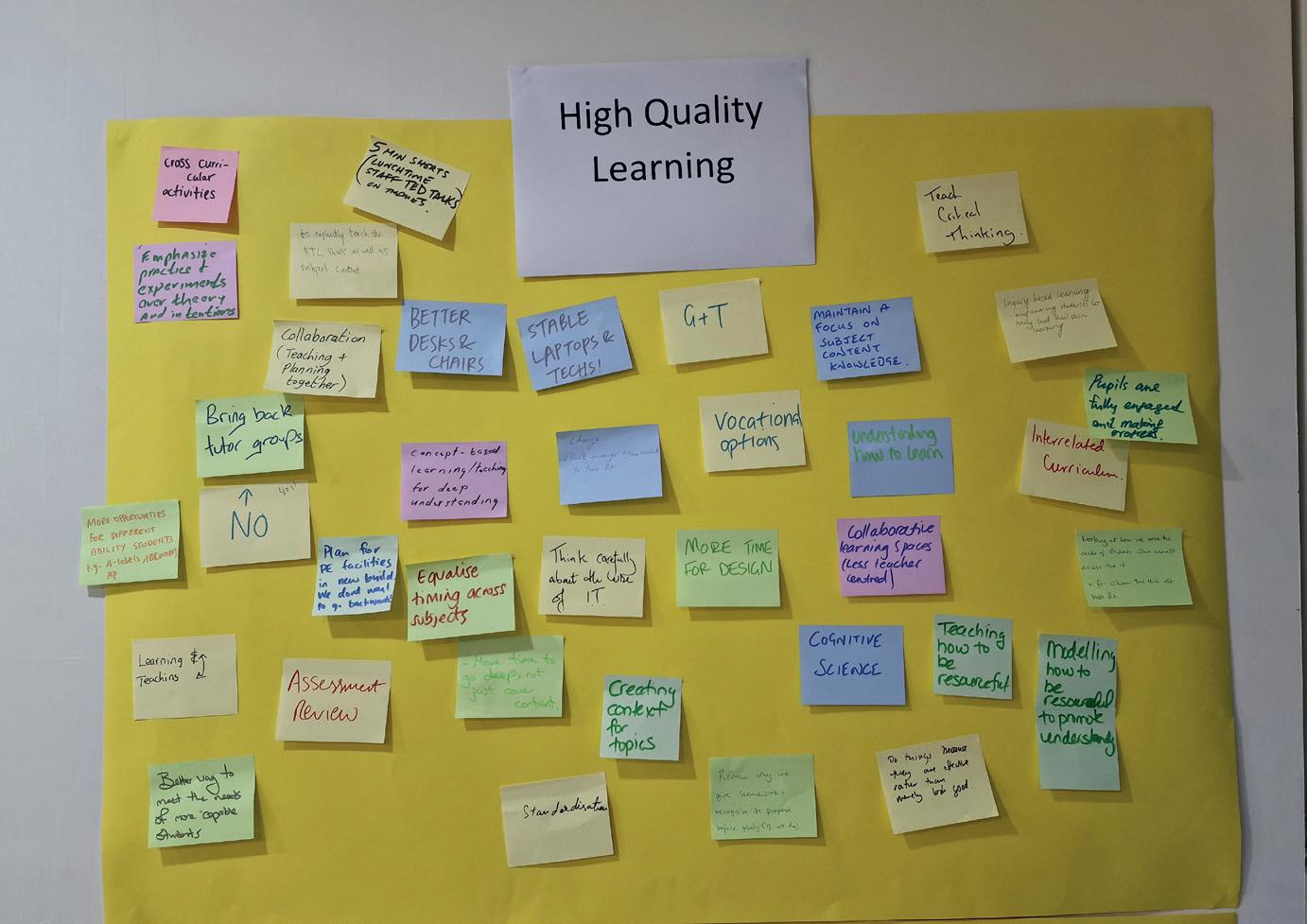

(See ‘High Quality Learning’ photo).

Step 2: Ask ‘what is the school trying to improve?’

The school has already identified that assessment practices need to be improved, and much work has already gone into addressing the problems of summative assessment overload for students, the need for embedded assessment for learning, peer and self-assessment practices,

12 | International School | Spring 2024 Features

and the role of feedback. As with any strategic direction, departments and individual teachers may move at different paces within an overall improvement of assessment practices. Departments have differing needs and starting points, as do individual teachers, and so it becomes vital to engage teams and individuals in a process of self-assessment, planning and reflection.

Step 3: Ask ‘what is each department trying to improve?’

Within an overall strategic approach to improving assessment, each department should identify one key area for development. Following the work of Steve Barkley (https://barkleypd.com/), this area for development is best framed as a hypothesis. For example, within a school focus on assessment, a department may want to improve feedback practices and so would hypothesise as to the impact of doing so. The department growth plan should include the actions the department and individual teachers will take in testing out this hypothesis, as well as how the success, or otherwise, of implementation will be measured.

Step 4: Ask ‘what is each teacher trying to improve?’

Within a whole-school focus on assessment, and a departmental focus on feedback, what am I going to do as an individual teacher? To answer this question as a teacher I would choose a class and define my individual hypothesis connected with the departmental hypothesis. This hypothesis would create the focus of my professional growth over a full school year. As an English teacher, for example, I might hypothesise that if students record and revisit feedback over time, they will build their understanding of their individual goals and targets, and this will allow for increased progress. Because my hypothesis has grown out of the department hypothesis which grows out of the school strategic plan or focus, as a teacher I have not only a shared sense of contribution to the overall development of the team but also the opportunity for individual growth. Once I have identified a focus area I will need to plan for the specific actions I will take in my classroom to test out and measure my hypothesis.

Step 5: From planning to action: intradepartmental peer-to-peer support

In creating a culture of professional inquiry, teacher-to-teacher support is a powerful step in the implementation of actions and particularly in gathering evidence of impact. Teachers can be paired within their departments and asked to identify ways in which the hypothesis could be tested. One such way is to observe a class period where each teacher is actively focused on the testing of their hypothesis. The peer observer can act as a sort of ‘research assistant’ to the teacher, whereby the teacher defines the focus of the observation and the methods of evidence collection. This could entail observing, or talking to, specific students during the lesson, interviewing students post-lesson, reviewing lesson materials and so on. The aim is not for the peer to evaluate the success of the lesson from an observer’s standpoint, but rather to support the teacher in assessing the success, or otherwise, of their hypothesis.

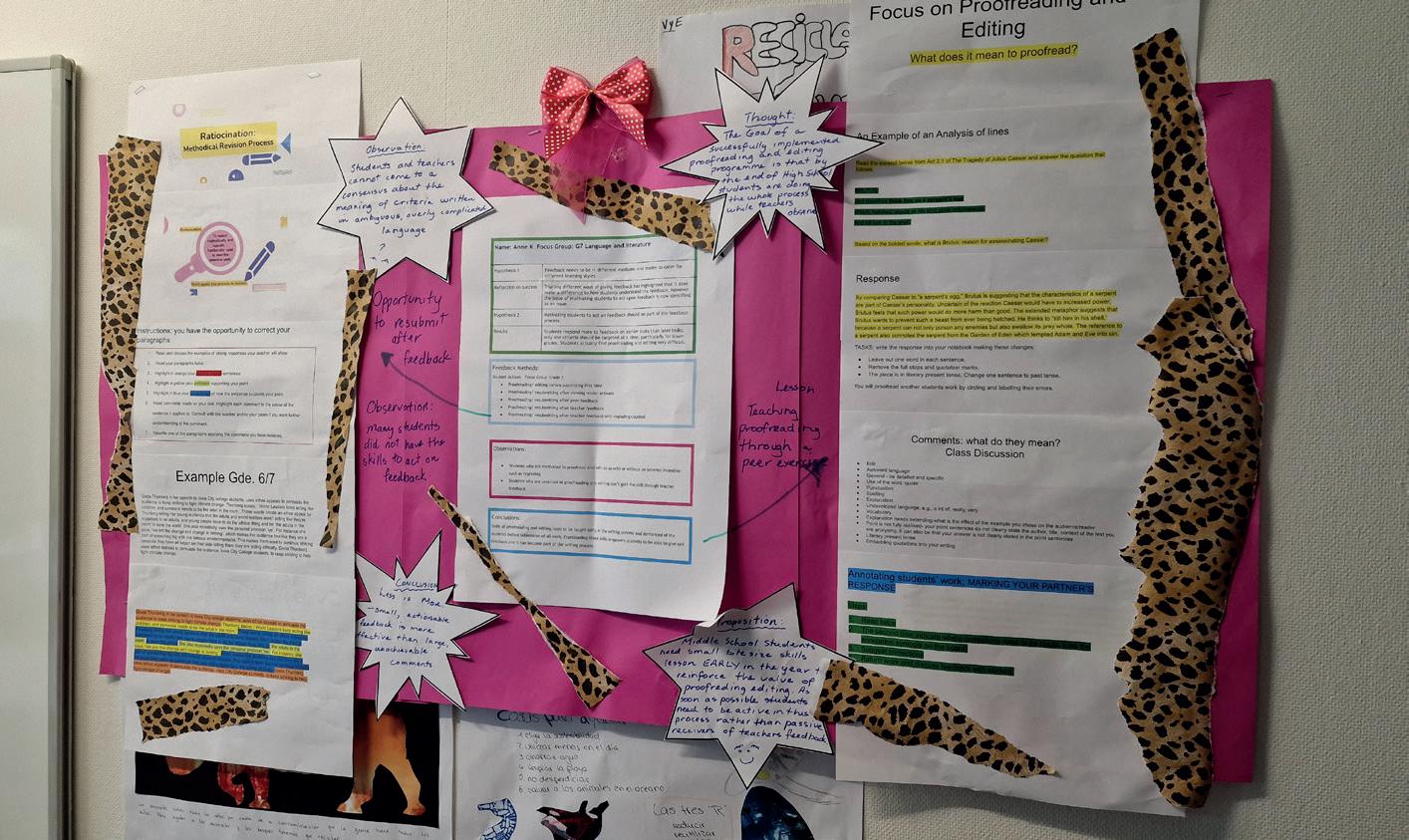

Step 6: A community approach to growth

Before beginning a new professional growth cycle it is important to celebrate the successes of department teams and to allow them to share their team, and individual, learning. Senior leaders should ensure that an opportunity is created for each department to present their planning, implementation and evaluation of success with regards to their departmental hypothesis. This approach brings the teams together in their collective efforts, but also

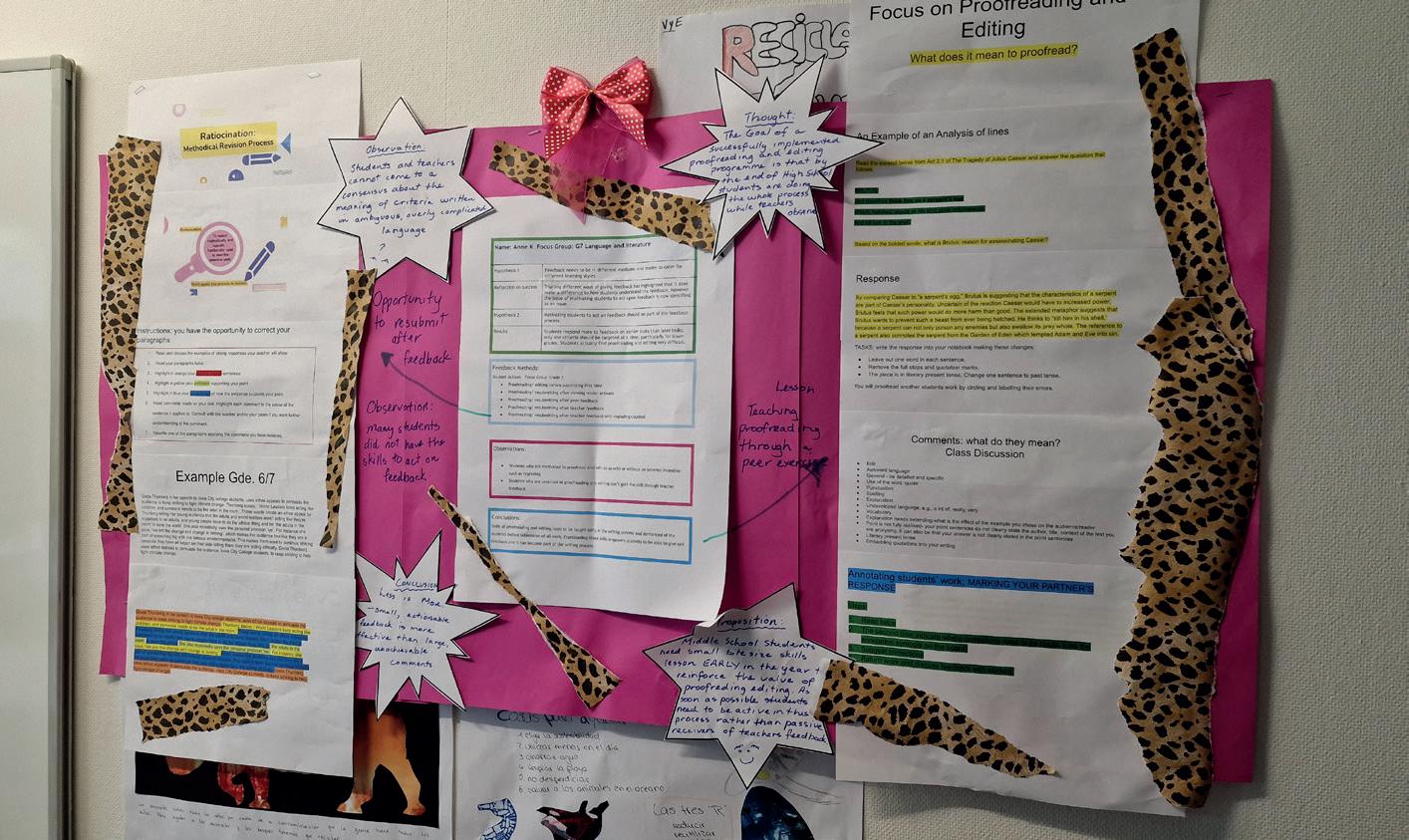

allows each team to learn from others and potentially adapt approaches as a school moves into a new cycle of development. Sharing collective growth is invaluable in creating a culture of professional inquiry. (See photo above).

Reflection and Evaluation

Many schools already recognise the advantages for teachers of moving towards a peer-supported professional growth model rather than the traditional appraisal model. For students, the advantages of innovation in the classroom are many. Firstly, students see teachers modelling lifelong learning. Teachers who are empowered to hypothesise and take risks are more likely to be innovative and creative in their response to student needs. However, this model does need to be built on established trusting relationships, and so the school needs to be confident in the ability of its teachers, in the resilience of its student body, and in the support of the parent community. A rigid hierarchical school structure, for example, may not lend itself well to such an approach. A school in this position may first want to evaluate and change the structures and practices which don’t support a culture of professional growth before rebuilding with a model such as this.◆

Ann Lautrette is Deputy Head of the British Secondary and High School Section at Taipei European School, Taiwan ✉ ann.lautrette@tes.tp.edu.tw

Spring 2024 | International School | 13 Features

Building Successful School Culture

Part 2: The School Professional Culture Arena

By George Scorgie

This article, part two of a series on school culture building (see the Winter 2023 issue of this magazine for part one), explores how school leaders in the international sphere can build and maintain a cohesive and positive school culture, and embed their school mission and vision into every aspect of school life.

The first part of this series introduced a model of culture building called the Cultural Core Framework (CCF). The CCF sees school culture as forming in four distinct but interdependent social and professional arenas:

• School Professional Culture Arena: beliefs about the professional identity and culture of the school;

• School Professional Practice Arena: policies, processes and actions involved in the daily operations of the school;

• Non-School, Social & Residential Arena: practices and approaches taking place outside the classroom and in the residential programs if applicable;

• School Social Cultural Arena: beliefs and understandings of school identity and culture held by the school community outside the classroom.

In each of these arenas there are a number of strategies school leaders can utilise to help them guide identity, culture, and practice across the school. This article examines the first of these, the School Professional Culture Arena: the area where each individual’s identity, ideas, and ways of doing and knowing interact. It is a cultural arena of both personal and professional interaction. How we see ourselves and how we understand the identity of the school informs how we act, and the Professional Culture Arena represents the space where these intersect.

Before exploring the approaches school leaders can utilise to shape the School Professional Culture Arena, it’s vital to note that at the centre of the Cultural Core Framework, connecting all aspects of school culture building, are school leaders, whose role it is to embed school identity, mission and vision into the daily experiences, routines and practices of their school. This is called Mission Focused Leadership. The first step must therefore be to define what the mission is. With most desks in many international schools globally now filled by local students,

perhaps the most fundamental of the questions defining a school’s identity may include ‘are we a local school with an international curriculum, or are we an international school in [insert location here]?’. Culture is as much comprised of what is purposefully excluded as of what is explicitly included, so the answer to this question is important as it forms the bedrock of identity, informs the privileging of language, contextualises parent expectations, guides teaching, learning and assessment, helps define collaboration, and informs how students may be expected to behave. Answering the question as to who we are as a school is vital in providing the foundational structures of school culture. Beyond this, a clearly defined identity and purpose also feeds into the process of cultural priming – how the school physical space reflects the culture: anything from art work to classroom posters, the language used at school events or in school publications, the

Leading, Teaching and Learning | International School | Spring 2024

holidays celebrated and so on. It may seem trivial, but exposure to cultural symbols in workplaces has been shown to have an effect on shaping the cultural behaviours of individuals (Fu et al, 2016).

Once armed with an unambiguous understanding of school identity, there are three key strategies school leaders can use to embed this in the school’s professional culture arena:

it’s the culturally erosive message they send to everyone else that they can do it their way and get away with it. This is especially the case with more visible transgressions: chronic lateness or leaving early, missing deadlines, being public with criticism or dissent around organisational policies and practices and so on. Richard Caffyn (2018) describes these individuals

they can actively manage teachers in their department before the need for more formal arrangements such as probation extensions that may be put in place by senior leaders. In this way, Mission Focused Leadership is not just the remit of senior leaders; it involves the initiatives, ideas and innovations of each level of school leadership.

How we see ourselves and how we understand the identity of the school informs how we act...

The first strategy is to enculture new staff members during their orientation. New staff inductions are invariably busy and, from the perspective of new staff, are often overwhelming. This is not to say that all the information presented isn’t important, just to say that at the most basic level, the burning questions each new staff member have are: what is my job?; where will I be doing it?; how would you like me to do it?; what systems do I really need to know to be ready for when my students arrive in a few days? These questions also sit at the core of school professional culture, so a simple, yet very effective, strategy is to be explicit with the answers to these. Orientation and onboarding are not times to be ambiguous: they are, perhaps, the most critical time to be explicit on questions about who we are, how we do things, and who we most definitely are not. Successful school cultures are actively curated, and this must begin from the very first day new staff are on campus.

and groups as vampires as they slowly but surely fragment culture and suck the life out of the school. It becomes vital that school leaders actively reduce the shadows in which vampires can hide, confront vampires directly if need be, and be active with management strategies that reduce the collective pebbles in the school’s collective shoes.

The reason for the above explicitness links to the second strategy: accountability to organisational cultural expectations. The mantra for accountability is that it is the pebble in your shoe that causes the most annoyance. In this case, it isn’t the actions of the individuals in question who may be the greatest cause of cultural disharmony,

References

The third key strategy is to genuinely empower teachers and middle leaders to make organisational change. Effective culture building, as part of effective leadership is, as Gurr (2015) noted, a layered process that needs to involve the building of leadership in others. This not only includes middle leaders as important stakeholders in school transformation, it also means schools can leverage the understandings and ideas of their often diverse staffing and middle leadership body (Gardner-McTaggart, 2018). Culture building cannot be top down: school senior leaders must set clear goalposts and define clear boundaries, then empower middle leaders to embed these. This includes involving cultural stakeholders such as heads of department in recruiting, policy reviews and so on, and providing them with structures so

This is not to say that creating a cohesive and shared professional culture is an easy task. On the contrary, it necessarily involves the willingness and strategies to have what many may frame as difficult conversations. What is clear, however, is that schools where the bedrocks of identity remain undefined, the processes of onboarding are not precise, and accountability is perceived as inconsistent, often develop multiple professional cultures operating simultaneously. The interaction of these cultures often lies at the heart of corrosive professional conflicts, serving only to further reinforce parochialism on all sides.

With the School Professional Cultural Arena providing the scaffolding around which culture is shaped, the next article in this series will examine the manifestation of this as the policies, practices, and everyday actions and interactions in the School Professional Practice Arena. ◆

✉

• Caffyn R (2018) ‘The Shadows Are Many ...’. Vampirism in International School Leadership: Problems and Potential in Cultural, Political, and Psycho-Social Borderlands. Peabody Journal of Education. 93(5): 500-517.

• Fu J H-Y, Zhang Z-X, Li F & Leung Y K (2016) Opening the Mind. Journal of Cross–Cultural Psychology. 47(10): 1361-1372.

• Gardner-McTaggart A (2018) International schools: leadership reviewed. Journal of Research in International Education. 17(2): 148-163.

• Gurr D (2015) A Model of Successful School Leadership from the International Successful School Principalship Project. Societies. 5(1): 136-150.

• Scorgie G (2021) School Culture, Leadership and Language Development in a Chinese-International School [Doctoral Thesis, Charles Sturt University] Available at: https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/en/publications/school-culture-leadership-and-language-development-in-a-chinese-i

Spring 2024 International School Leading, Teaching and Learning | | 15

Dr George Scorgie is Deputy Head (Pastoral) & Head of Boarding at Trident College, Zambia.

georgescorgie@gmail.com

Reflections on Learning and Teaching:

Who Are School Assessments Really For?

By Cherry Atkinson

Targets. Progress. Value-added. Attainment levels. Stretch and challenge. Intervention and support. I would be shocked to my core if you could show me one teacher who has not been in a meeting where these concepts have been discussed at great length.

We are living in an age where there is increasing accountability across all service industries, and where ‘feedback’ is requested for every service – even visiting a public toilet! The idea is that, ostensibly, feedback improves performance. It provides an indication of what the service is getting right and what it needs to work on. That all sounds fine; it’s important to say thank you to people who are going a good job, and to be able to complain if the service is poor.

However, there is an unspoken element here, where you are not just required to do your job well – it becomes necessary to prove that you are doing your job well. This mindset has crept into every aspect of the labour market, and teaching is no exception. Whether you work in the state sector, independent sector or the international sector, you will be appraised regularly, and a significant part of that appraisal will be the progress and performance of your students. As of course it should be. It stands

it becomes necessary to prove that you are doing your job well

to reason that the ultimate goal of any teacher should be to help their students to progress. But what should that progress look like?

The easiest way to show educational progress is through numbers. Data. Movement along a scale or continuum. The easiest way to get that data is to test, score and grade. There has been a slow but steady shift towards assessment-led teaching, which I believe has been driven by the need for schools to prove that

they’re doing a good job. School leaders and classroom teachers are conscious that the people paying their wages want to see progress, and in the independent and international sectors that means parents. The parents are the customers, and the customer is always right. This is quite often reflected in practice through a curriculum based around assessment opportunities. Weekly, fortnightly, monthly or termly grades can be instantly shared with parents, and numbers can be crunched by data managers. It would take a bold and supremely confident senior leader to try and buck this trend, but what we are seeing more and more frequently in the classroom is an increased number of anxious children who ask: Is this going to be graded? Will this be in the test?

Rather than enabling children to take delight in the acquisition of knowledge and experience, the heavy focus on proving progress seems to be sucking the joy out of learning. Think about the last book you read, or a documentary you might have watched recently: would you have enjoyed it in the same way if you knew there was going to be a test on it afterwards? Children are under pressure from all sides, and perhaps what they need is some respite from the relentless assessment regime of their daily school experience, where they must feel that their worth is weighed, measured and judged on an alarmingly regular basis by most of the authority figures in their lives. Children the world over are experiencing mental health issues – many of which are rooted in educational pressures (Keane, 2023; PA Media, 2023), but there is no indication that things are going to change any time soon. Education that is focused on testing must surely be a major contributor to anxiety in children and yet here we are, blithely continuing down a path that could be setting them up for an adult life riddled with mental health problems – all in the name of ticking a box to say that we deserve to be paid.

What I would like to see, in a utopian world where such things might happen, is the development of schools where children can just be children while they are children. I would like to see children being guided towards a love of learning and exploration, discovery, wonder and creativity. It’s going to be hard to unlock the genius of future generations if we insist on teaching them that the only way of being deemed ‘clever’ or ‘smart’ is to pass a test, or gain a certain level in an exam. There are countries in the world where ‘educational competition is downplayed’ (Pellisier, 2023), but they are small islands of anomalous practice in an ocean of assessmentheavy national and international systems.

Just as the shift towards assessment-led teaching has been incremental, the further shift towards enjoyment-led learning

could take place through small but manageable increments. I want to make an earnest plea for school leaders and education policy makers to consider that perhaps reducing the assessment burden might be a more effective way of supporting staff and student wellbeing than putting on yoga classes after school, or teaching deep-breathing techniques during a lunch break. This will require some brave decision-making, and some very firm and frank discussions with parents, but the benefits could be enormous. The shift away from assessment-led teaching would require school leaders and policy-makers to place more confidence in teachers’ professional judgement, which is where my utopian dream begins to fall apart. Whilst most teachers I know (and certainly all those who are worth their salt) can tell you within a couple of weeks of meeting a class what their students’ abilities are, that does not translate too well on a spreadsheet as ‘evidence’. Those same teachers can easily tell you who is ‘top’, ‘middle’ or ‘bottom’ in their class; testing merely confirms what can be judged professionally (and discreetly), but it cements that position in a child’s mind and adds a level of pressure that brings joy to no-one.

If we want to instil a love of learning in our young people and foster their creative talents rather than point them off towards a world of anxiety and poor mental health, it is vital that we at least start a conversation about the actual value of testing –who is it for? Does it really help the students in our care, or is it predominantly a way for teachers to satisfy their paymasters? What the customer wants and what the customer’s children need are perhaps two very different things. ◆

References

• Keane D (2023) Exam Stress is Putting Students’ Mental Health at Risk, says UCL Research. Available from https://www.standard.co.uk/news/health/examstress-teenagers-children-mental-health-risk-ucl-research-b1100111.html

• PA Media (2023) Head Teachers Express Concern Over SATs Amid Claims a Paper Left Pupils ‘In Tears’. Available from https://www.theguardian.com/ education/2023/may/11/headteachers-express-concern-over-sats-amidclaims-a-paper-left-pupils-in-tears

• Pellisier H (2023) The Finnish Miracle. Available from https://www.greatschools. org/gk/articles/finland-education/

Cherry Atkinson is currently working as Head of Individuals and Societies at an IB international school in The Bahamas.

✉ cherryatkinson@hotmail.com

Spring 2024 | International School | 17 Leading, Teaching and Learning

Onscreen Assessment

Choice for you and your students

Offering students the choice to sit either onscreen or paper exams ensures the best possible outcomes, preparing them for the workplace and further education. We have been delivering onscreen exams since 2022 and have seen students reacting positively at the opportunity to take their high-stakes exams onscreen.

Students love it!

93%* of students told us that they use devices outside of school activities on most days or every day and 86%* use them for projects and assignments at home on most days or every day.

Students say:

We used a lot of online apps to help us get used to using a computer like we would in the exam and that really helped, it also made me feel a lot more confident about taking the exam online.

Isabel Clare Cattell - Student at Qatar International School

Teachers love it!

With easy onboarding for schools, support for staff and invigilators and great benefits for students it’s easy to understand why we have seen the number of schools adopting onscreen assessment triple for this current exam season.

We live in a technological world now and education is moving in a particular direction that would suggest that exams will be online. We wanted to be one of the leaders in the country.

Michael Merrick, Associate Head of Secondary, Qatar International School

It’s been a fantastic experience for us as a school, but also for our students who were absolutely delighted to work in a way that they felt most comfortable with.

Wayne Ridgeway, British School of Bahrain

By 2026 we will have 14 International GCSE and International A Level subjects available with more subjects being added.

* Post assessment student survey July 2023

To find out more and register your interest visit

www.pearson.com/international/oa

18 | International School | Spring 2024 Leading, Teaching and Learning

Resisting the ‘Best Possible Self’ Narrative Within a Teacher Education Programme

by Natalie Shaw

Ateam of colleagues on the ITEPS (International Teacher Education for Primary Schools) Bachelor of Education (BEd) programme at NHL Stenden University in the Netherlands recently approached me with the request to teach an introductory session on meditation and mindfulness to our new first-year cohort. As a passionate teachereducator, actively practising meditator, and qualified practitioner in vormingsonderwijs (a world view teaching approach offered at primary schools in the Netherlands: Franken & Betram-Troost, 2022), I actively embrace the opportunity to share my praxis with students. Yet at the same time, whenever I teach meditation, I am concerned about the ways in which students may engage with this subject matter.

In this article, based on professional practice and reflection as well as personal contemplation, I will connect my concern about my students’ response to this introductory meditation session to the ways in which students engage with setting professional development goals. I will use two approaches to shed light on both activities: the neoliberal view, wherein meditation, mindfulness, and goal-setting are viewed as a personal project of selfimprovement (Brito et al, 2021; Reveley, 2016; Reveley, 2013), and the more critical view, in which both activities may offer a pathway towards counteracting the premises of the consumer-capitalist society and act as forces for change (Scherer & Waistell, 2017; Reveley, 2013). From the outset, I wish to make clear that, like everyone in education, I am caught in the sticky threads of the current

system’s prevalent, growth-oriented selfoptimisation logic. With the help of others, I actively try to cut loose from these as best I can. In doing so, I appreciate the solidarity and inspiration of colleagues near and far who are working on the same project.

Neoliberalism’s glittering mirage of a ‘best possible self’

Within a neoliberal perspective, meditation and professional goal-setting emerge as endeavours with the ultimate aim of personal improvement, adding to a rich personal portfolio of marketable skills. My colleagues and I encounter this version of ‘cognitive capitalism’ (Reveley, 2013: 539) in the pernicious formulation of a ‘best possible self’ which students frequently profess to strive towards when formulating professional development goals. In doing so, they echo the message of popular media (see, for instance, Niemiec, 2013). Yet not only in popular discourses can the idea of a best possible self be found; it also manifests in academic publications (Boselie et al, 2023; Heekerens & Eid, 2020; and critically Reveley, 2013).

Within this approach, learning to meditate and to increase one’s mindfulness may emerge as a further tool for ‘an effective manipulation to temporarily improve optimism and affect’ (Boselie et al, 2023). As early as 2005, the New York Times reported efforts to teach meditation in schools as a ‘possible antidote to rising anxiety, violence and depression among students’ (Micucci, 2005).

As teachers, we may appear in dire need of an optimistic outlook: we practise our craft within systems increasingly dominated

by data-driven quests for ever-optimised excellence and efficiency (Department for Education, 2017; Schleicher, 2019). In both education and the wider world, we witness processes of unravelling. From having policy dictate our pedagogy (for an analysis of the way Ofsted now defines the concept of play for Early Childhood educators, see Wood, 2019) to the mounting effects of extractivisim, injustice, and climate emergency, optimism may not be a ready response most of us would be able to summon. Reaching for an antidote, as the rather superficial application of mindfulness may offer us, may appear tempting as a means to avoid asking the deeper and more difficult questions – for example, tracing the root causes of the mounting mental health crises beyond the realm of the personal.

Meditation and mindfulness of a neoliberal ilk appear to have us covered in providing a ready tool for personal change, effectively distracting us from acknowledging the need for systemic shifts within our profession as well as society at large. ‘Social problems’ appear as ‘private concerns rooted in individual biology, mentality and behaviour’ (Nehring & Frawley, 2020: 1184). If we fall victim to this siren call, however, we may be foregoing the transformative potential of deeply feeling the dismay, grief, and outrage that should be our response to the many

Spring 2024 | International School | 19 Leading, Teaching and Learning

injustices and violations witnessed in the world of which we are inextricably a part (Macy, 2021). In resorting to ‘psychological imaginations’ (Nehring & Frawley, 2020: 1184), we jettison the possibilities that lie in collectively asking deeper, probing, and difficult questions about the origins of the mental distress that meditation and mindfulness profess to allay.

As to my imminent meditation and mindfulness introduction, I am consequently concerned that students might share meditation and mindfulness practices with children in domesticating ways, in line with current practice in many schools. An uncritical mindset may frame these practices as handy, 5-minute engagements to quieten the children sufficiently to engage in the next learning task with improved concentration, leading to ever-greater subject mastery within an ever-narrowing curriculum and approach to schooling. Ergas terms this approach ‘mindfulness in education’ (Ergas, 2019: 340; my italics), in contrast to the more transformatively oriented ‘mindfulness of education’ (Ergas, 2019: 340, my italics).

Even in schools that may wish to strive against the technocratic application of mindfulness in education, oftentimes there is a singular time chosen for a mindfulness focus, for example at the beginning of the day. Yet the remainder of the day then passes in breathless pursuit of utilising the available instruction time ever more efficiently. Students in our degree course, returning from teaching practice, report that both play time and snack time suffer such optimising efforts. What will children take away: the fact that they learnt some

calming breathing techniques for 3 minutes in the morning, or the fast pace and resulting feeling of being overwhelmed that governs the vast majority of their time spent in school?

In an extension of the self-improvement project approach, meditation may be welcomed in schools as a further element of the children’s set of social-emotional skills (Reveley, 2013; for an interesting critique of the Western-centric approach to social-emotional learning see You, 2023) and used to foster ever more ‘effective’ learning according to the inherently neoliberal efficiency logic.

Hand-in-hand with the neoliberal enthusiasm for embarking on what within our faculty we occasionally term ‘personal DIY projects’ goes a consumerist readiness to acquire ‘technologies of the self’ (Foucault 1982, in Leggett, 2022: 262). Our students frequently draw on an abundantly available technological tool library for their mindfulness projects: meditation apps, podcasts that purportedly foster improved sleep, and online selforganisation planners. After all, mindfulness is an undeniable market, leading to the moniker ‘McMindfulness’ as coined by Purser (2019).

Cunningly, it works in vicious cycles: the very products acquired to assist in the meditation and mindfulness project themselves command the users’ attention (Chayne, 2022; Purser, 2019), leading to the ever-increasing experience of a lack of attention and focus. Impatient with what is consequently perceived as a personal failing in one’s mindfulness aspirations, students may then fall ready victim to ever more consumerism as a way to alleviate the feelings of dissatisfaction about ‘getting nowhere’.

A further characteristic of this mindset is the solipsistic aspect that, in our experience, renders each student the perceived lone driver of their personal self-improvement project. Occasionally, students tend to lean on peers for feedback and support, particularly if moments of doing so are structurally built into the programme. Yet ultimately, students rarely embrace the true interwovenness of learning and the ways in which the opportunities for personal and professional evolving can be explored and shared with others. If encouraged and challenged to do so, however, students

may find that the very moment of being addressed by the other may lead to deeper learning than any self-propelled tinkering in the margins (Biesta, 2022).

Gesturing towards a more critical engagement

An alternative, and my personally preferred, approach towards meditation is one that recognises it as a deeply culturally rooted practice that is embedded in complex Buddhist philosophy and worldview. Central to this is the attempt to interrogate the ultimate source of human suffering (Hanh, 2015). This in turn will point the meditator towards a contemplation of the inherent futility of attaching oneself to all phenomena that are naturally transient in nature, as their loss will unfailingly lead to suffering.

Meditation also enables the practitioner to sit, literally and figuratively, with the uncomfortable emotions and thoughts that arise. There is no best possible, nebulous self out there that elusively yet tantalisingly hovers just beyond reach, yet ready to manifest if the practitioner tries hard enough. The disappointment that may be felt when this desired mirage fails to materialise may all too easily be poured into acquiring the next distraction, entertainment, or gadget –unless meditation is used with the intent to allow for a critical questioning of the dissatisfaction, boredom, and doubts of self-worth that may propel us towards the next act of consumerism. Learning to be with uncomfortable feelings, thoughts and situations is also a vital basis for having the difficult conversations that education needs to address in the pursuit of challenging racism, sexism and colonialism, amongst others (Dadvand et al, 2022).

Further, core meditation practices encourage the practitioner to reflect upon a key tenet of Buddhist philosophy: the concepts of non-duality and interbeing (Hanh, 2015). Sometimes visualised with the image of a multi-faceted web, the idea of humans as solipsistic, independent creatures in need of no-one else is challenged even in the very simple, beginner-level contemplation of all that is present in a generic food item or cup of tea: from the weather conditions that allowed the growth of the tea plants to the resources that went into creating the cup itself, the transportation of

20 | International School | Spring 2024 Leading, Teaching and Learning

2023)

both tea and cup so they end up in the practitioner’s hands, to the water as a main ingredient and sustenance of life. Invariably, this leads practitioners to contemplating the entanglements between objects previously viewed as ‘things’, and can give rise to a profound appreciation of the interdependence that is a hallmark of deep ecology thinking.

The thought of interdependence leads to a further fundamental idea underpinning Buddhist practice: it is vital to seek support from those who share our path in life through the community that surrounds us. In a podcast episode, Buddhist practitioner Brother Pháp Hũu (Hũu & Cofino, 2021) describes the practice of voicing aspirations at the beginning of the Rains Retreat, a traditional period of contemplation established in the time of the historical Buddha. Each member approaches the community with a goal they have in mind, formed through careful mutual encouragement and the practice of providing thoughtful feedback to one another. The community is then asked to support each member, transforming personal aspiration into mutual, shared endeavour.

From this, I wonder whether we may use this idea to unsettle and thereby invigorate students’ approach to personal goal-setting. Rather than formulating these independently, can we invite students to see these as learning adventures that are not solitary paths, but that unfold in a web of events, places, objects and others that may all be called upon to support, to give shape, to redirect if necessary?

Concluding thoughts and aspirations

From what I have shared, I would like to suggest a few ways of moving forward as examples in my own practice. I frame these as my own aspirations, and hope that my colleagues and other human and nonhuman actors on my path will emerge as parts of an interdependent web that holds me in attempting to address them.

When teaching about meditation, I will try to invite students to think critically about

Dr Natalie Shaw is an ITEPS lecturer and Year 2 Coordinator at NHL Stenden University, the Netherlands.

✉ natalie.shaw@nhlstenden.com

current trends in education and adjacent disciplines, their own position towards these, and not to shy away from the complexity of engaging.

When supporting goal setting, I will try to reflect on the process with the students to break out of solipsistic self-improvement narratives and into the rich, messy, multi-

References

faceted world of learning with, from, together with others and the world of which we are a part.

And, as Zen master Thich Nath Hanh responded when asked how not to despair about the state of affairs and the small contribution we may potentially make: you tried. And ultimately, that is enough. ◆

• Biesta G (2022) World-centred Education: a View for the Present. London: Routledge.

• Boselie J L M, Vancleef L M G, van Hooren S & Peters M L (2023) The effectiveness and equivalence of different versions of a brief online Best Possible Self (BPS) manipulation to temporary increase optimism and affect. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 79.

• Brito R, Joseph S & Sellman E (2021) Exploring mindfulness in/as education from a Heideggerian perspective. Journal of Philosophy of Education. 55(2): 302-313.

• Chayne K (Host) (2022, April 26) Reclaiming our capacities for deep thinking and intimate engagement. (No. 354) [Audio podcast episode]. Available from https://greendreamer.com/podcast/johann-hari-stolen-focus

• Dadvand B, Cahill H & Zembylas M (2022) Engaging with difficult knowledge in teaching in post-truth era: from theory to practice within diverse disciplinary areas. Pedagogy, Culture & Society. 30(3): 285-293.

• Department for Education (2017) Teaching Excellence and Student Outcomes Framework Specification London: Department for Education. Available from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/ uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/658490/Teaching_Excellence_and_Student_Outcomes_ Framework_Specification.pdf

• Ergas O (2019) Mindfulness in, as, and of education: three roles of mindfulness in education. Journal of Philosophy of Education. 53(2): 340-358.

• Franken L & Betram-Troost G (2022) Passive Freedom of Education: Educational choice in Flanders and The Netherlands. Religions. 13(1).

• Hanh T N (2015) The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching (3rd ed.) Harmony Publishing.

• Heekerens J B & Eid M (2020) Inducing Positive Affect and Positive Future Expectations Using the Bestpossible Self-intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 16(3): 322-347.

• Hũu Br P & Cofino J (Hosts) (2021, September 24) Slow Down, Rest, and Heal: The Spirit of the Rains Retreat (No 7) [Audio podcast episode]. Available from https://plumvillage.org/podcast/slow-down-restand-heal-the-spirit-of-the-rains-retreat#hypertranscript=NaN,NaN

• Leggett W (2022) Can mindfulness really change the world? The political character of meditative practices. Critical Policy Studies. 16(3): 261-278.

• Macy J (2021) World as Lover, World as Self. Parallax Press.

• Micucci D (2005, February 15) International Education: Meditation helps students. New York Times. Available from https://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/15/style/international-education-meditation-helps-students.html

• Nehring D & Frawley A (2020) Mindfulness and the ‘psychological imagination’. Sociology of Health & Illness. 42(5): 1184–1201.

• Niemiec R M (2013) What Is Your Best Possible Self? Available from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/ blog/what-matters-most/201303/what-is-your-best-possible-self

• Purser R (2019) McMindfulness: How mindfulness became the new capitalist spirituality. Watkins Publishing.

• Reveley J (2016) Neoliberal Meditations: How mindfulness training medicalizes education and responsibilizes young people. Policy Futures in Education. 14(4): 497–511.

• Reveley J (2013) Enhancing the Educational Subject: cognitive capitalism, positive psychology and well-being training in schools. Policy Futures in Education. 11(5): 538-548.

• Scherer B & Waistell J (2017) Incorporating mindfulness: questioning capitalism. Journal of Management Spirituality & Religion. 15(2): 123-140.

• Schleicher A (2016) Teaching Excellence Through Professional Learning and Policy Reform. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Available from https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education teaching-excellence-through-professional-learning-and-policy-reform_9789264252059-en#page3

• Wood E (2019) Unbalanced and Unbalancing Acts in the Early Years Foundation Stage: a critical discourse analysis of policy-led evidence on teaching and play from the Office for Standards in Education in England (Ofsted). Education 3-13. 47(7): 784-795.

• You Y (2023) Learn to Become a Unique Interrelated Person: an alternative of social-emotional learning drawing on Confucianism and Daoism. Educational Philosophy and Theory. 55(4): 519-530.

Spring 2024 | International School | 21 Leading, Teaching and Learning

Intelligence on Demand How AI Challenges Educators

By Paul Juscha

Artificial Intelligence (AI) poses new challenges in many aspects of life, while simultaneously offering possibilities that were unimaginable until recently. In today’s era of rapid technological advancement, AI plays an increasingly significant role in our daily lives. From self-driving cars and intelligent assistants to advanced diagnostic systems in healthcare, AI has the potential to revolutionize various aspects of our society. The opportunities presented by the use of AI are impressive, ranging from increased efficiency in various industries to addressing complex challenges in different areas of our lives. However, this emerging technology also faces a range of challenges, from ethical concerns to potential impacts on the job market and education.

These two facets of AI – its possibilities and its challenges – require closer examination to develop a comprehensive understanding of the impact of this groundbreaking technology on our society and, particularly, on education. It has been over a year since ChatGPT, an AI solution that operates based on natural language, became a part of our lives. Since then, many processes at school have been set in motion, and traditional methods, approaches, and assessment criteria considered effective in teaching and learning need to be reconsidered, replaced, or revolutionized.

While students used to conduct their own research and perform the often-perceived tedious and timeconsuming writing tasks, many of these processes may now be outsourced to AI. This makes sense and can focus the learning process on essential tasks, giving students a certain delegation function where they stand above the details and the teacher’s assignments. Who needs to copy homework from the top student when there’s AI that can complete excellent assignments without demanding anything in return? This leads to the emergence of a modern and digitized student who seemingly has access to any personalized knowledge in the universe – knowledge on demand. What was once reserved for streaming music, movies, series, and podcasts is now available for knowledge and individual work and learning assignments. Why should a student memorize something when they can access information any time? Why should a student sit down and write a poem about diversity when they only need to input the prompt?