Thy Neighbor or

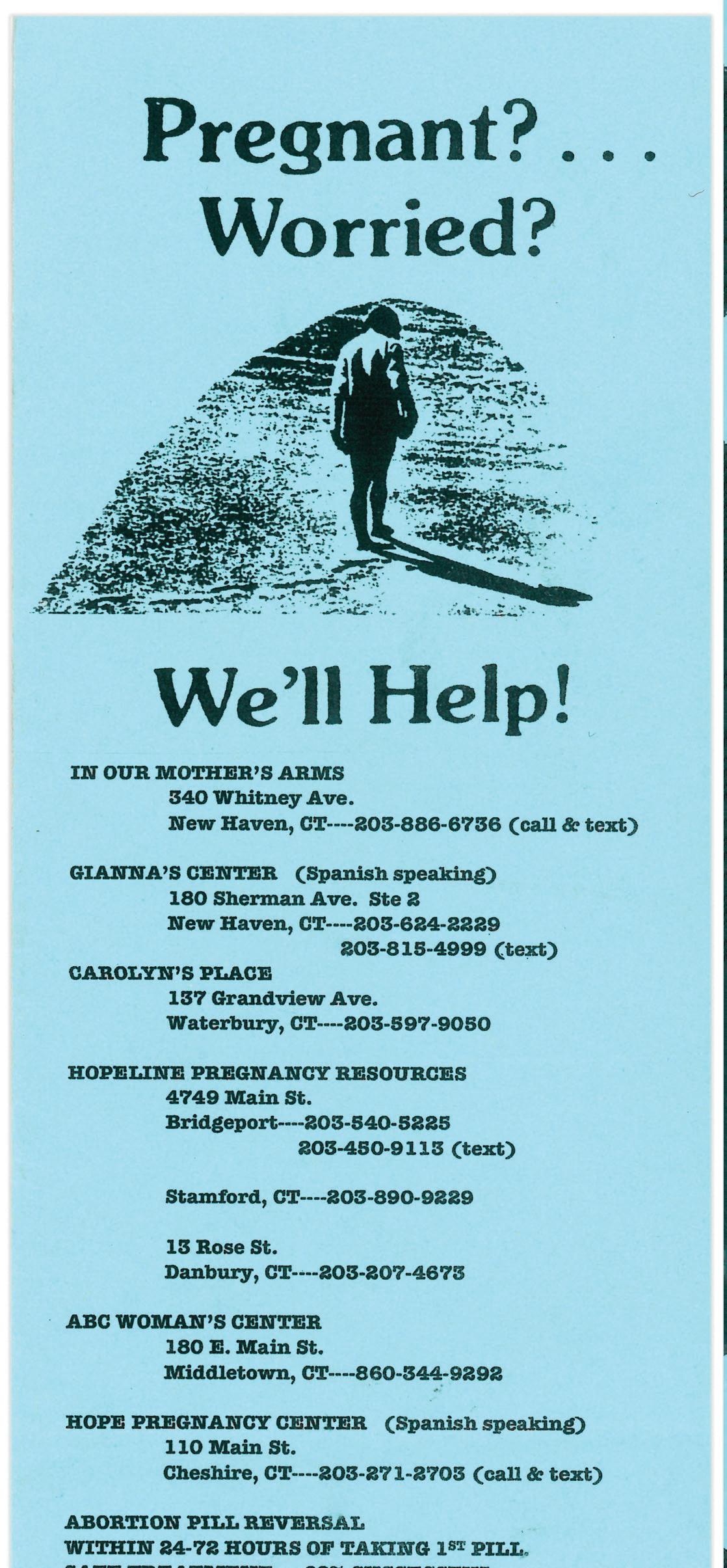

mission to provide free services to pregnant clients—and end abortion. A look from the inside, and the sidewalk, at In Our Blessed Mother’s Arms.

Teacher pay in New Haven, building a religion from A to Z, and the Sweet Dreams Society.

The Magazine About Yale and New Haven Volume 55, Issue 2 November 2022

Inside

AND A CROSSWORD TOO!

The New Journal, founded in 1967, is a studentrun magazine that publishes investigative journalism and creative nonfiction about Yale and New Haven. We produce five issues a year that include both long-form and short features, profiles, essays, reviews, poetry, and art. Email us at thenewjournal@gmail.com to join our writers’ panlist and get updates on future ways to get involved. We’re always excited to welcome new writers to our community. You can check out past issues of The New Journal at our website https://www.thenewjournalatyale.com

Editors-in-Chief Nicole Dirks

Dereen Shirnekhi

Executive Editor Jesse Goodman Managing Editor J.D. Wright

Associate Editors

Amal Biskin Abbey Kim

Meg Buzbee Yosef Malka Jabez Choi Cleo Maloney

Lazo Gitchos Paola Santos

Ella Goldblum Kylie Volavongsa Yonatan Greenberg

Senior Editors

Beasie Goddu Madison Hahamy Alexandra Galloway Zachary Groz

Copy Editors

Marie Bong Edie Lipsey Adrian Elizalde Lukas Trelease Rafaela Kottou Yingying Zhao

Creative Director Kevin Chen

Design Editors

Meg Buzbee Charlotte Rica Camille Chang Karela Palazio Photography Lukas Flippo

Members & Directors: Emily Bazelon • Peter Cooper • Jonathan Dach • Kathrin Lassila • Eric Rutkow • Elizabeth Sledge • Jim Sleeper • Fred Strebeigh • Aliyya Swaby

Advisors: Neela Banerjee • Richard Bradley • Susan Braudy • Lincoln Caplan • Jay Carney • Andy Court • Joshua Civin • Richard Conniff • Ruth Conniff • Elisha Cooper • Susan Dominus • David Greenberg • Daniel Kurtz-Phelan • Laura Pappano • Jennifer Pitts • Julia Preston • Lauren Rawbin • David Slifka • John Swansburg • Anya Kamenetz • Steven Weisman • Daniel Yergin

Friends: Nicole Allan • Margaret Bauer • Mark Badger and Laura Heymann • Anson M. Beard • Susan Braudy • Julia Calagiovanni • Elisha Cooper • Haley Cohen • Peter Cooper • Andy Court • The Elizabethan Club • Leslie Dach • David Freeman and Judith Gingold • Paul Haigney and Tracey Roberts • Bob Lamm • James Liberman • Alka Mansukhani • Benjamin Mueller • Sophia Nguyen

• Valerie Nierenberg • Morris Panner • Jennifer Pitts • R. Anthony Reese • Eric Rutkow • Lainie Rutkow • Laura Saavedra and David Buckley

• Anne-Marie Slaughter • Elizabeth Sledge • Caroline Smith • Gabriel Snyder • Elizabeth Steig

• Aliyya Swaby • John Jeremiah Sullivan • Daphne and David Sydney • Kristian and Margarita Whiteleather • Blake Townsend Wilson • Daniel Yergin • William Yuen * Donated twice. Thank you!

2

Join us!

Thank you to our donors. Neela Banerjee* Anson M. Beard James Carney Andrew Court Romy Drucker Jeffrey Foster David Gerber David Greenberg* Matthew Hamel Makiko Harunari James Lowe Chaitanya Mehra Ben Mueller Sarah Nutman Peter Phleger Jeffrey Pollock Adriane Quinlan Gabriel Snyder Fred Strebeigh Arya Sundaram Stuart Weinzimer Steven Weisman Suzanne Wittebort by the BESTMAGAZINESTUDENT IN THE COUNTRY SocietyofProfessional Journalists NamedThe since 1967

Kylie Volavongsa

4

points of departure

Chloe Nguyen visits the Neville Wisdom design studio on Broadway, where local artists gather. Camille Chang examines Loose Leaf and the boba-ification New Haven.

cover feature

Thy Neighbor

A New Haven family center is on a mission to provide free services to pregnant clients—and end abortion. A look from the inside, and the sidewalk, at In Our Blessed Mother’s Arms.

feature

Building a religion from A to Z

After uncovering the World Mission Society Church of God’s presence on Yale’s campus, two writers take a closer look at the religious organization that has been accused by former members of being a cult.

critical angle

Barred Waters

As local activists and legislators attempt to make Connecticut’s beaches more accessible, a writer reflects on her coastal childhood in California.

snapshots Wading for Hope

As sea levels rise, New Haven is seeing an increase in flooding that carries sewage and diseases with it. The Urban Resources Initiative is working to implement the infrastructure to change that.

Those Who Stay

New Haven Public School teachers are leaving for nearby districts with higher wages. It’s not easy to make the choice to stay.

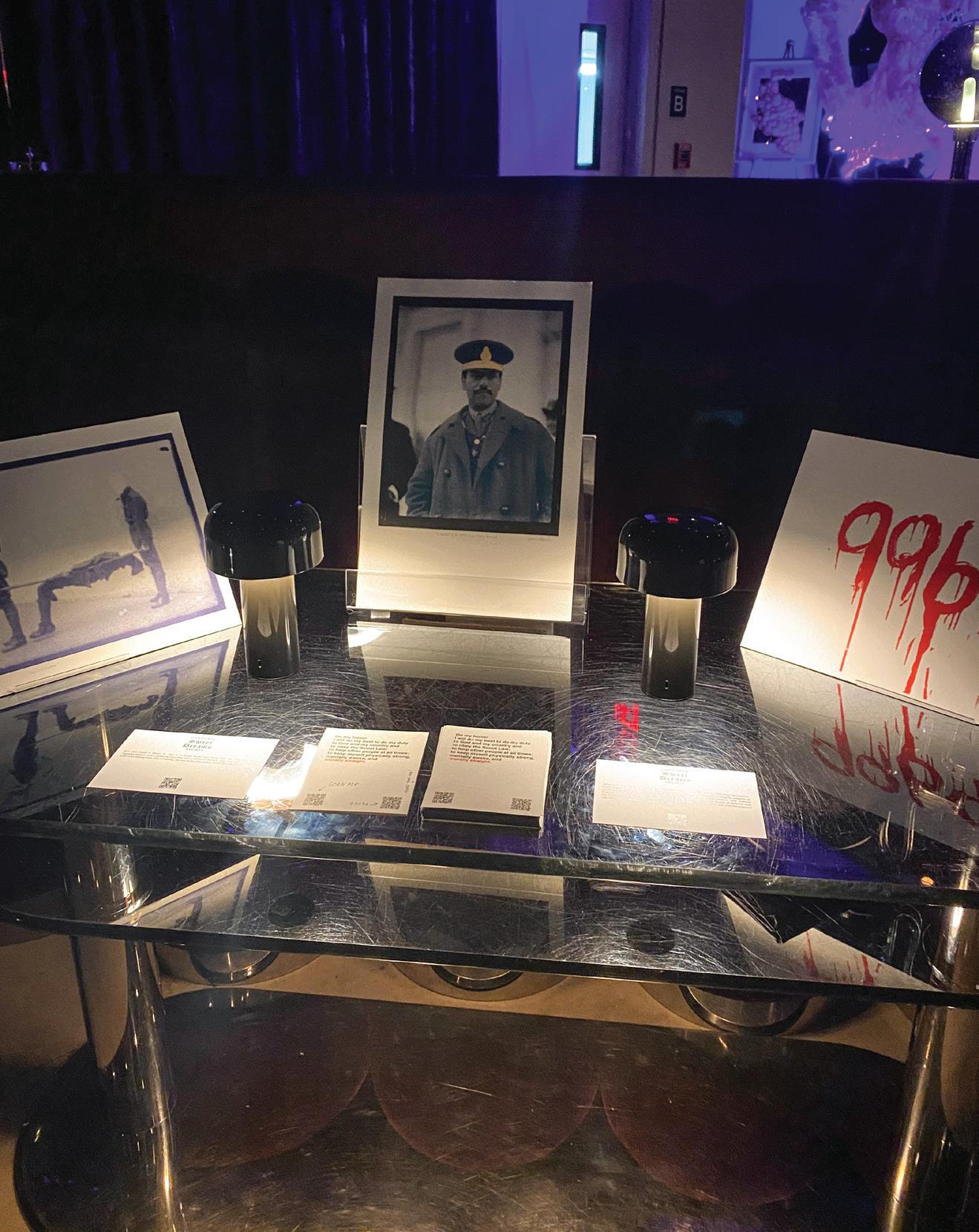

Hotel Dreaming

Between the walls of the Graduate Hotel lives a hidden artists’ society. poems

Ella Goldblum Jools Fu Paola Santos Netanel Schwartz

Paradise in Miniature Lachrymose in Chinatown

God is not dead, God is just a loser Friday night Premonition On My Father’s

Funeral

all else

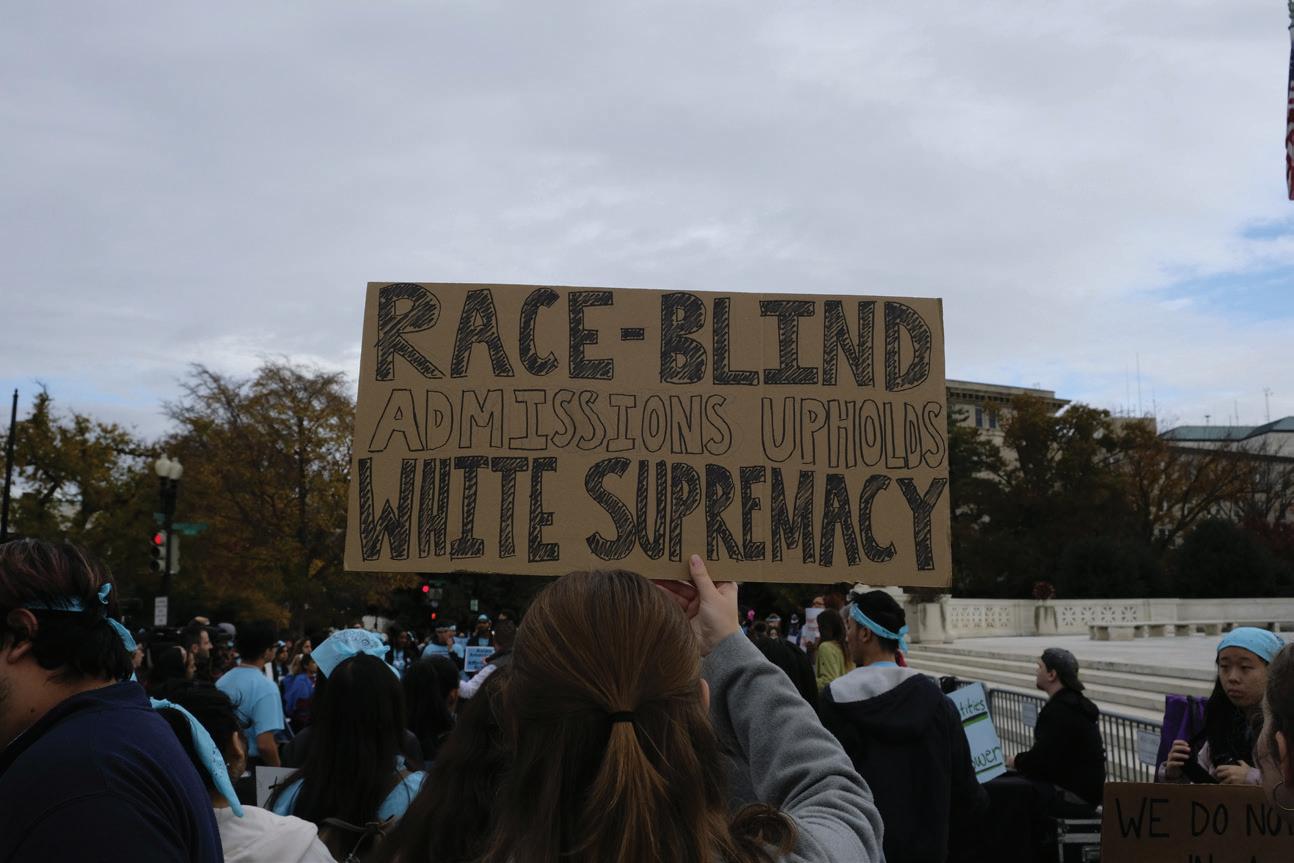

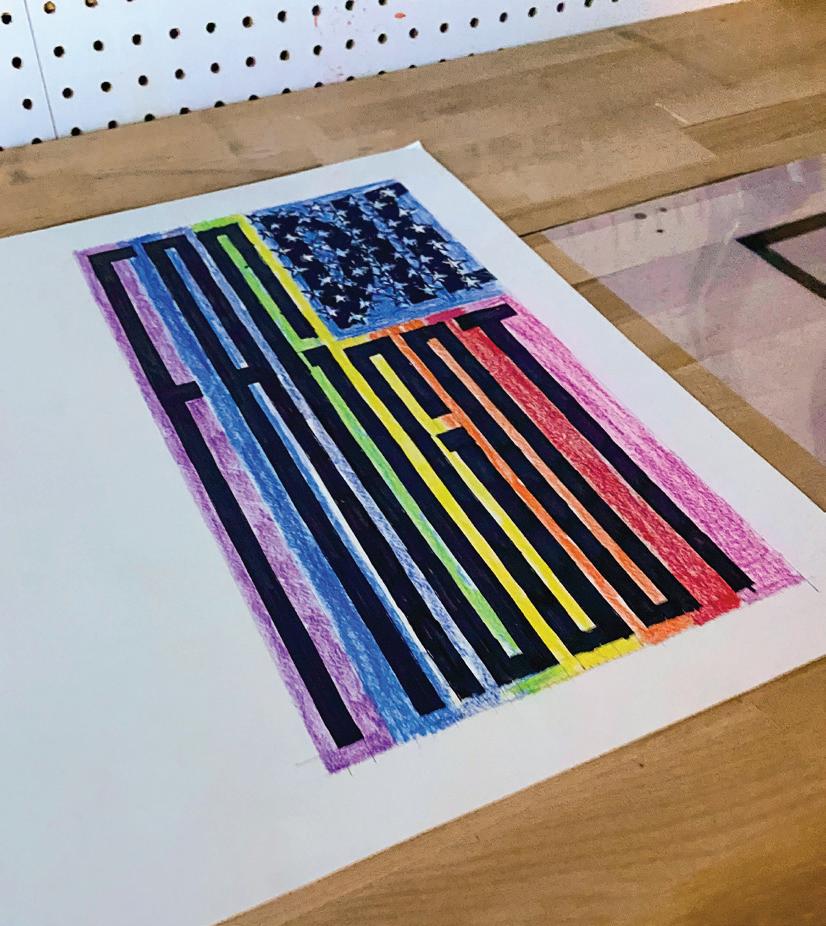

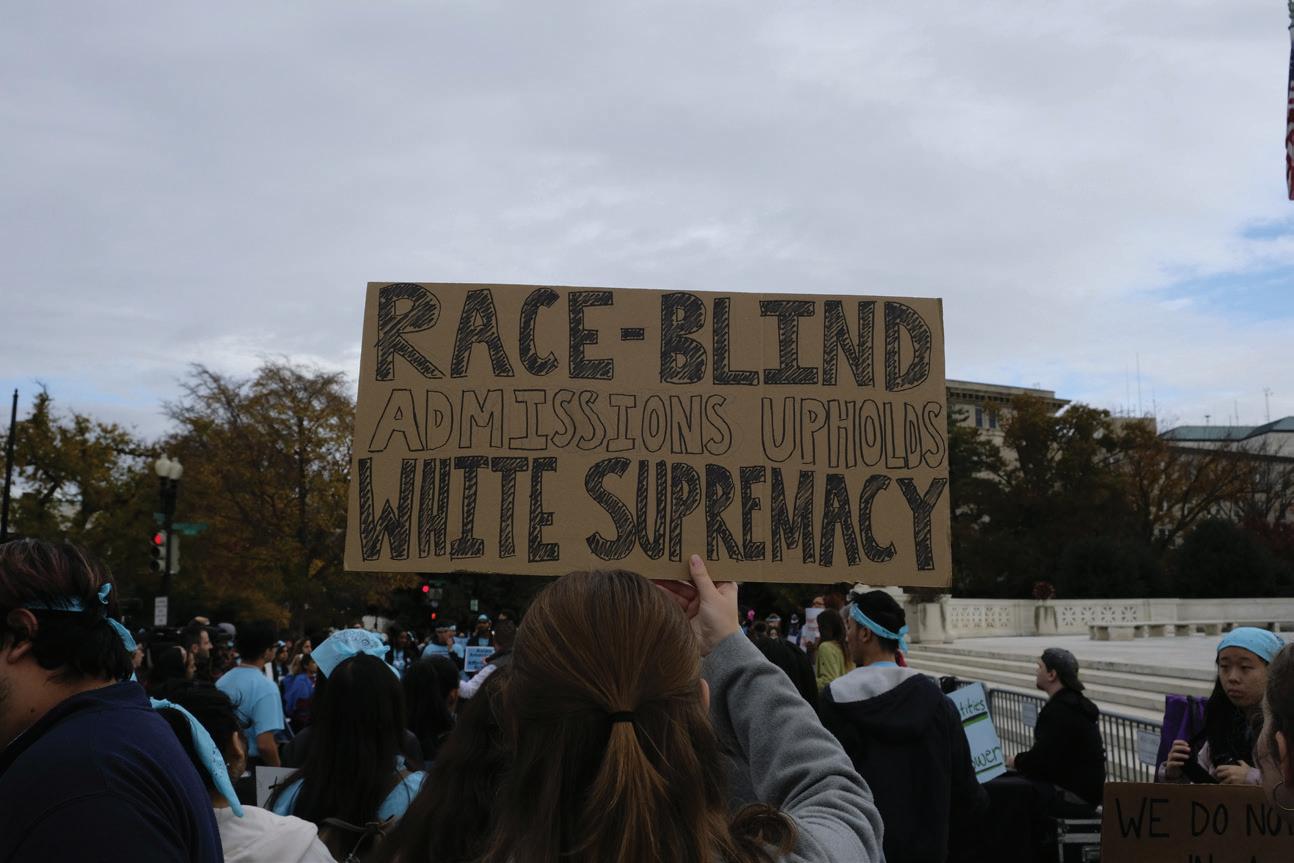

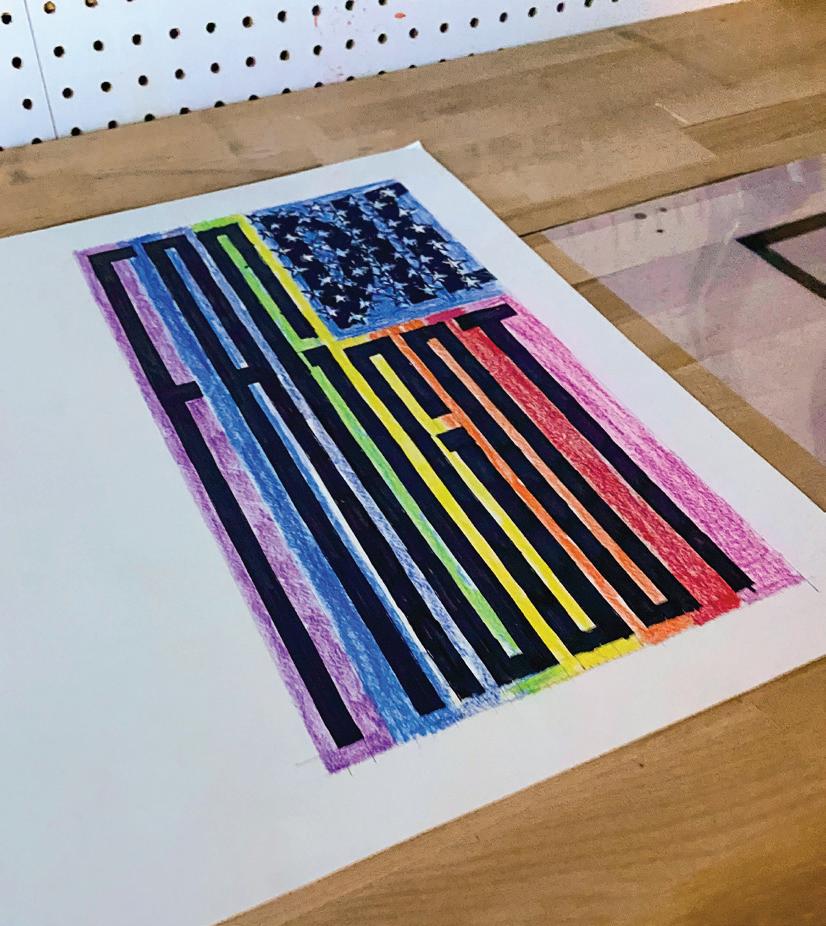

The Farm, aside , by Simon Billings, page 62. Affirmative Action rally, photos , by Rachel Shin, page 46. Getting Symbolic, crossword , by Jesse Goodman, page 63.

3

Nicole Dirks

Paola Santos

Hanwen Zhang Caroline Reed

Volume 55, Issue 2 November 2022 The Magazine About Yale and New Haven

Miranda Jeyaretnam

and Sarah Cook 32 20 48 8 14 56 13 47

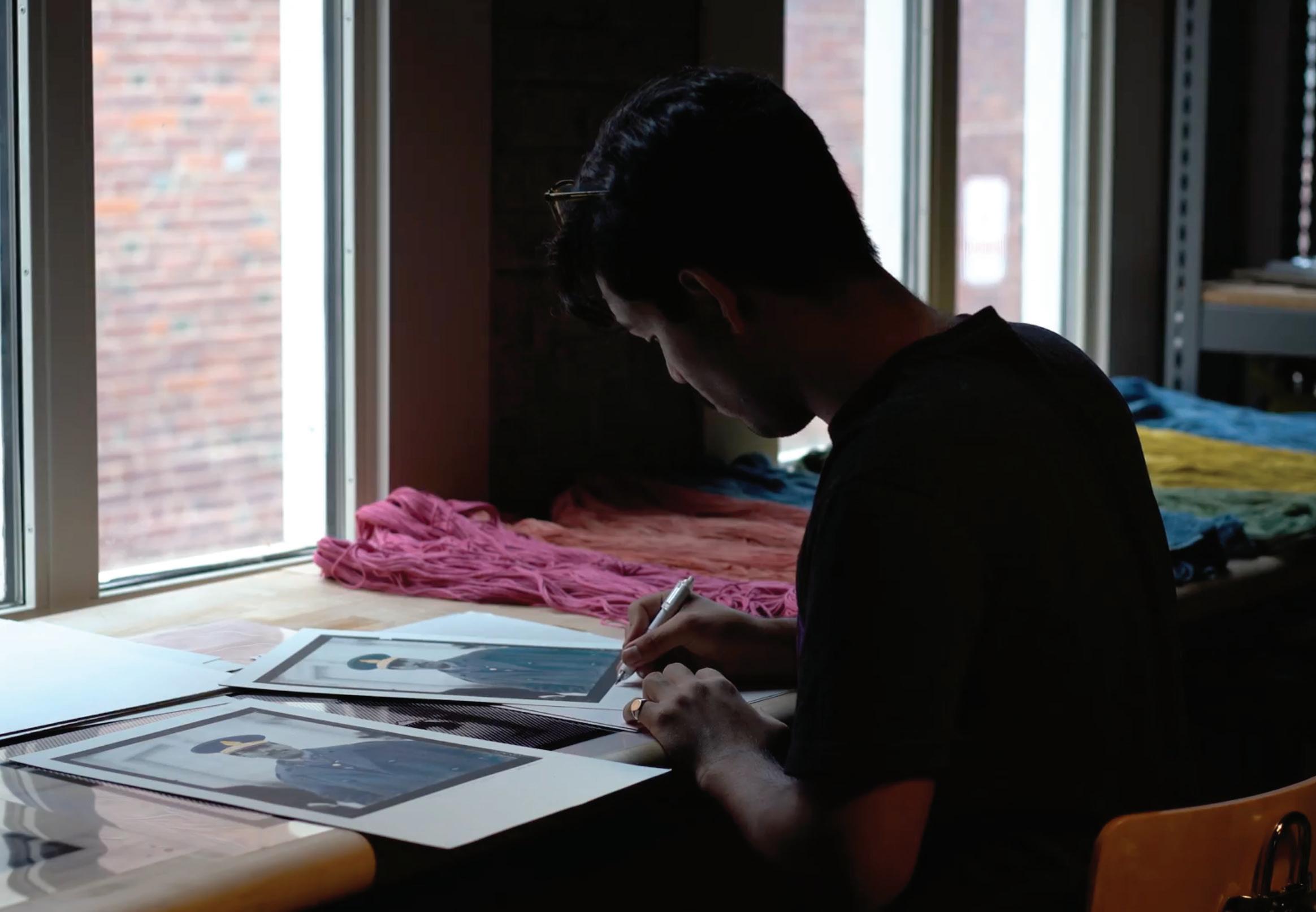

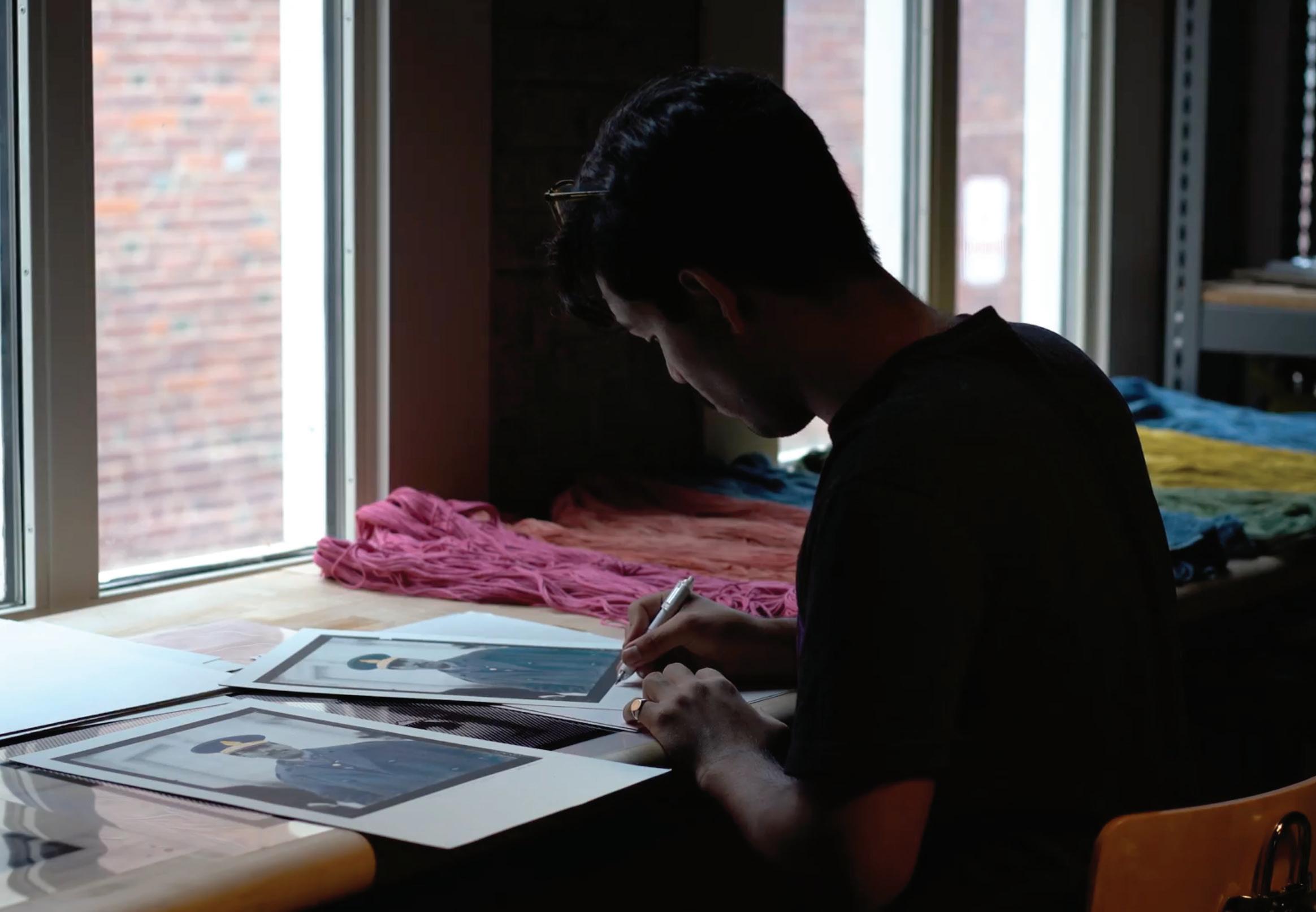

Studio Haven

“You see the Apple Store, you see L.L.Bean, then you see a black ass store, it’s painted black, it looks creepy as fuck from the outside. It’s kinda like a candy shop, it’s enticing, you’ve gotta look in there,” said Palayo Mais, a multimedia artist from New Haven and a regular at the Neville Wisdom Fashion Design Studio.

I spoke with Palayo soon after my first visit to the Neville Wisdom studio. Before then, I hadn’t spent much time perusing the Broadway conglomerates, and the name “Neville Wisdom” did little to elucidate the purpose of this enigmatic store. From the words “WHERE ARE YOUR CLOTHES MADE ?” written in big black letters in the tinted storefront window, decorated with mannequins sporting cocktail dresses and streetwear, I could only guess it was another one of Broadway’s many highpriced clothing boutiques.

What I didn’t know at first was that behind the dressy storefront, undercover in a sea of corporate strongholds, resides the Neville Wisdom Fashion Design Studio, a nucleus and safe haven for creatives throughout the city. Its leading creator and businessperson Dwayne Moore Jr. invited me to see the space myself.

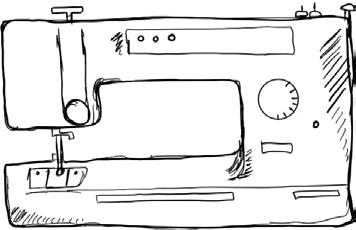

Dwayne’s relationship with Neville Wisdom, after whom the store is named, is tightly knit, sewn with years of built trust and patience. In just about five years, Dwayne went from serendipitously wandering into Neville’s studio to recently becoming a partner at the business. Starting out as an apprentice to Neville, Dwayne developed skills he can put to practice as part of the studio’s business and as part of his own brand. Together, Neville and Dwayne’s income is largely made of clothing alterations and commissions.

As Dwayne now continues to take a more administrative role, Neville Wisdom transitions into retirement. I couldn’t reach Neville himself for this article, as he was on a boat in the Caribbean and had lost his phone.

Dwayne gave me a look inside what he describes as his second home.

“This is the space that keeps [the studio] alive for the most part,” Dwayne said as he led me to the back half of the studio. Behind the storefront mannequins is a regiment of industrial sewing machines and an artillery of fabrics, much of it accumulated thanks to the community of local donors that Neville himself has established throughout his career. Overlooking the studio is a fivefoot tall multimedia portrait of Neville, with a black and white base and colorful cloth embellishments. Even further back, through a narrow hallway overtaken by old sewing experiments and works in progress is the store’s photography space. In this studio, shower thoughts become inventive clothing lines, gallery additions, and new prints.

built. Some days Palayo leaves with armfuls of clothes from Dwayne’s personal line. One time, Dwayne gave Palayo a spare camera to help with his photography endeavors. Palayo can spend hours at the studio, where he and Dwayne will work in the hum of sewing machines and R&B, reflecting on each other’s projects, lives, and anything else that comes to mind. To Palayo, the studio is a sanctuary, a place grounded in creativity and camaraderie that has been conducive to his growth as an individual and artist.

Dwayne and I flipped through catalogs and portfolios of local New Haven artists whose books were proudly displayed on the store’s shelves. Meanwhile, he told me about a well-meaning customer who had reminded him of the trials he would experience, especially as a Black artist and businessman. Sharing racial identity, the customer had told Dwayne to be wary of the personalities he would meet given his business and given its location. “You sound like my mom,” Dwayne had laughed, dismissing the concern. Negative attention, if any, is hardly an issue to him because the individuals that naturally gravitate toward the Neville Wisdom studio are the types of people he’d want to associate with anyway.

“What pulls people in is the window and the ‘Made in New Haven’ sign,” Dwayne tells me. “I think that’s in part why people come in here, because it feels out of place.” That is, among the surrounding chain stores that boast bright curated facades and imported goods, Neville Wisdom sticks out.

The Neville Wisdom studio is a playground for anyone with a vision. Those interested, like Palayo, pay a fee to use the space consistently, but all visitors are welcome. Drawn to the unique handmade pieces that Dwayne documented online, Palayo brought himself through the doors of the Neville Wisdom studio to discover what he described as a “bat cave.”

Palayo has found solidarity in the community Neville and Dwayne have

“The way the front is set up, it’s as if only the people I think I would engage with come in here. I feel like looking at this place you have to be open to wanna even come in.” As many new faces as he sees, Dwayne feels a strong sense of community at the studio, between New Haven being his home and the storefront drawing in like-minded people. “You’re already curious,” he said. “I like to talk to curious minds.” Dwayne told me that the first time he landed outside Neville Wisdom’s door he was reading a book called Curious Minds, and we marveled at the full-circle moment.

A few times in our conversation, Dwayne shifted his attention to helping another studio regular perfect a waistband on a pair of shorts. The fabric he was working with was one of his own designs, a quadriptych featuring the band Kiss. In the closing hours we spent talking, a handful of visitors leaked in and out of the studio, some customers and local creators looking to take their ideas through the finish line. In the Neville Wisdom studio, the storefront and the design studio exist in symbiosis.

To Dwayne, his responsibilities in the studio are not a clock-in, clock-out

4 November 2022 TheNewJournal Points of Departure

illustrations by Meg Buzbee

ordeal—they’re lifestyle, an extension of his being. In his eyes, the studio is as much a workshop as it is a home. “Some nights I’ll just sleep on that couch right over there,” Dwayne gestured to the satin couch where my coat and tote bag were resting.

By many standards, New Haven is not the ideal spot for exercising creative visions. Palayo believes that the art traffic in New Haven is “nonexistent,” as a product of the population and the lack of diversity. In New Haven, the culture does not seem to demand novelty like other larger cities, where the movement of people isn’t defined by a monopolizing private institution. Meanwhile, Dwayne sees the market differently, “It can feel small, but I think I’d feel smaller in any

other city to be fair. It’s about connecting with the people who you think resonate with you. It depends on how you look at it for sure.”

“[My] favorite part [is] how open it is. In a literal sense and also how people perceive it when they walk in. I think I like that so much because I’ve experienced that exclusivity from people not wanting to teach me,” Dwayne reflected on the studio’s function in the community. “The fashion industry seems so exclusive, but we’re more than welcome to anyone that wants to be a part of this.”

The Neville Wisdom Fashion Design Studio has taken a new shape over the years, especially as a result of the pandemic, and will continue to do

so with the changing leadership, which Dwayne believes he can use to draw a youthful perspective and energy into the studio. The diversity of people and opinions is what he believes will reignite the space. “I don’t see it going away or moving, as much as we downsize,” Dwayne asserts, “It says a lot about the usefulness to the community.” The studio is one-of-a-kind, a place providing people of all backgrounds and interests with a community that hardly says no and relentlessly gives. “In the industry you serve the person you work for, and the space,” Dwayne explained. “This space serves me.” ∎

—Chloe Nguyen is a first year in Saybrook College.

When I asked her how she came to own a Loose Leaf, she told me about her business philosophies, about eating spoonfuls of red bean as a child, about working fourteen hours a day when starting FroyoWorld, about her family and her life.

Warm Balls, Hot Commodity

Before school started, before the packs of twelve-person first-year friend groups started menacing campus, before twelve-packs of Bud Light began to litter High Street, I met Lisa Satavu. I walked into the Loose Leaf on Whitney Avenue on a tepid August day, sweating lightly. Satavu had her two children in tow, ages 7 and 2. We sat down at a table, all four of us. I sipped a Banana Foster Milk nervously, glancing at the small heart sharpied on the lid.

Satavu and her husband Marcus own and operate a vast array of businesses in Connecticut. Yale students before my time might remember FroyoWorld frozen yogurt shops in the spots where the Loose Leaf locations on High Street and Whitney Avenue currently stand. It was Lisa and her brothers that first started what is now a successful, New England-wide chain of frozen yogurt shops. Satavu and her husband also own all Saladcraft and Pokémoto locations in New Haven.

Satavu had been a teacher before she delved into the food industry. “My brothers were always the business guys,” she said. After ten years of teaching, she decided to join her brothers in managing their FroyoWorlds. But Satavu said that Froyoworld, in New Haven at least, had run its course by the time the boba industry started to gain mainstream traction in 2019 and 2020.

“With time, things change, just like fashion, just like the interests of people,” Satavu said. “Granted, everything starts first on the West Coast, but at least in our sense, we felt like Yale is kind of the heart of the East Coast, with all the newest attractions and cultural foods. So that’s why we wanted to bring Loose Leaf here.”

So, like students from across the country arriving in droves to the East Coast, many for the first time, Loose Leaf seems to be another wide-eyed West Coast transplant, finding its footing in New Haven, Connecticut.

I wrapped up my conversation with Satavu. I was under the impression that I was the one interviewing her, but after the twenty minutes I spent speaking to her, she offered me a job. A week later, I was a “bobarista.” . . .

I

n The Book of Tea, published in 1906, the aesthete and art critic Okakura Kakuzō detailed the birth, history, and beauty of making a simple cup of tea. Of primary importance to him was the rare harmony of Eastern and Western cultures in their enjoyment of tea. “Humanity has so far met in a tea-cup,” he wrote.

“In the liquid amber,” he wrote, “within the ivory-porcelain, the initiated may touch the sweet reticence of Confucius, the piquancy of Laotse, and the ethereal aroma of Sakyamuni himself.” Okakura saw tea-making as a religion in and of itself, drawing in philosophies from Buddhism and Daoism.

I wonder what Okakura would think of a typical summer afternoon in the bustling kitchen of a Loose Leaf Boba shop. Drinks sling with the efficiency of hospital triage, bobaphiles coming and going, still more young people chatting around mouthfuls of the “real tea, real ingredients, and real milk” that Loose Leaf’s website advertises.

Everything takes on a rosy pink tinge in the light of the iconic Loose

5 TheNewJournal November 2022 Points of Departure

illustrations by adam zapatka

Leaf neon signs. “With my besteas,” they proclaim. “Don’t teas’ me!” At the table next to me, two boys talk about their summer consulting internships and their upcoming YSIG (Yale Student Investment Group) interviews. Everyone is drinking boba.

The tapioca balls, introduced to the United States in the late nineteen-eighties by Taiwanese immigrants, go by a whole host of monikers in both English and Mandarin. There’s the “bubble” in bubble tea, tapioca pearls, boba, etcetera etcetera. I heard a rumor that the word “波霸” (romanized, literally “bo” and “ba”) stemmed from Taiwanese slang for boobs. I texted my dad the question: “Does 波霸 actually mean breasts in Taiwanese slang?”

“Actually, big breasts,” he replied.

So in its very nature, a kind of original sin, perhaps boba is deeply unserious. Squishy, often warm, globular and toothsome—on every Loose Leaf cup is the same phrase printed in small font: “Caution: Little Warm Balls.” While Okakura Kakuzo thought that East and West might be unified in tea, boba itself, in its spherical glory, might be a complete foil to the seriousness of the tea ceremony of East Asian traditions.

Originally sequestered in Taiwanese American, and then Asian American, communities, boba has quickly spread to major cities over the past five years, and it’s now firmly rooted in New Haven. Vivi Bubble Tea on Chapel, a branch of the nationwide chain, opened in 2016. Whale Tea on Whitney Avenue opened in 2019. The two Loose Leaf locations opened in 2021 and 2022. Now, seeing students toting the characteristic tall, clear cup and black boba-compatible straw is commonplace.

Many young Asian Americans raised on the West Coast, myself included, grew up drinking boba, brightly colored and distinctly flavored, in chain stores like Tea Station and Lollicup. Back then, drinking boba was weird. It was a foreign drink, and the pearls were a textural and geometric shock. Years later, everyone is drinking boba, from California to Connecticut.

Loose Leaf, like so many other national boba chains, began on the West Coast. As the sun was going down on a scorching California day, I met Thomas Liu and Jasmine Yip, the founders of Loose Leaf, at their Los Angeles Melrose location. We spoke under a faux-fresco mural of The Last Supper starring Bernie Sanders, Cardi B, Kurt Cobain, Trevor Noah, Oprah Winfrey, and Ellen DeGeneres, drinking pale beige cups of boba.

Liu grew up in the San Gabriel Valley, a predominantly Asian suburb of Southern California, just twenty miles shy of the city of Los Angeles. “It was Asians on top of Asians,” he said. “There was a boba shop on every corner.”

The complicated cultural makeup of his family, the majority of which moved to Vietnam from China after the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, informs his interest in the food industry. It informs the menu choices at Loose Leaf, too: offerings range from drinks incorporating pandan, a green Southeast Asian leaf that tastes like vanilla and coconut, to the “POG Agua Fresca,” inspired by Mexican roadside beverage stands.

But both Yip and Liu never shook the idea that boba’s shape, texture, and name were something to laugh at. Jasmine said that their brand is based on the idea that humor, like food, bridges

wide gaps. Loose Leaf’s voicemail directs you to place an online order at “warmballs.com.”

“Everything you do, just enjoy your life,” Yip said. “Customers who have a sense of humor will see you like you’re real people.”

I look up at Jesus-Bernie painted onto the wall, his arms spread open as if proselytizing, and Judas-Oprah grasping a cup of boba in her traitorous hand. Sense of humor, indeed.

Paul Freedman, a serious, glasseswearing man surrounded by shelves of colorful books, is a Professor of History and a Medievalist specializing in Catalonian and cuisine history. Standing among the last bastions of non-boba drinkers, he believes that consuming culture, such as media and food, is a misguided way to understand people.

“I don’t think that gastronomy is a path toward understanding,” he told me when I interviewed him. “People your age have been taught a lot of pieties in high school ‘Oh, if we just eat a lot of Vietnamese food, we’re gonna understand a lot more about Vietnam’ is in that category of comforting pieties.”

I thought back to reading about the religious history and ceremonies surrounding tea culture in Japan and China. I wonder if the way that tea has evolved has required an evolution of the way we worship it, that drinking boba tea requires a repetition of “comforting pieties” to be palatable.

However, many boba shop owners that I interviewed espoused the idea that boba actually can in fact bridge gaps between people and serve as an introduction to Asian culture and foods. Lisa Satavu is one of them.

“Coming with friends, trying all

6 November 2022 TheNewJournal Points of Departure

Kevin Chen / The New Journal

these flavors, their vision gets a little bit more open about certain things,” she said.

In Whale Tea on Whitney Avenue, couples sipped each other’s drinks and groups of friends studied the complex menu together as I spoke with Jessie Cheung ’24. Cheung is familiar with how boba functions both as a business and a social setting. She is from Dallas, where her family opened Texas’s first ViVi Bubble Tea franchise. They have since helped establish three ViVi stores across the state. Cheung points to a rising interest in East Asian food and culture, sometimes referred to as the Hallyu Wave, as one reason for the rise in boba consumption.

“Asian culture is now so much more prolific, especially with the popularity of Korean culture,” Cheung said. “So a lot of people have been starting to engage with boba because it’s so easy. It’s like, instead of getting a coffee, which

is a very American thing, you can just get a drink.”

It is boba’s ambiguous identity as an “Asian” drink, now mutated into something unquestionably American, that makes it so interesting to me. While boba is now “easy” to consume, (convenient and ubiquitous and, God forbid, “trendy”) it contains so much baggage. Some Asian-Americans have started using the phrase “lunchbox moment” to describe the times when we opened our lunch boxes full of kimchi and gyoza and curry and fried rice and glass noodles, and were met with caterwauls of “It stinks!” or “Ew, what is that?” Drinking boba in the presence of people who didn’t know what it was used to be a textbook lunchbox moment. Now, everyone is drinking boba.

My friend Shane Zhang ’25, remembers getting boba with his friends almost every Friday in high school. When

he drank boba, he said, it was a way of enjoying a quasi-Asian drink that was palatable to non-Asian friends.

“It’s like I’m Colossus of Rhodes—I straddle two worlds,” he said. “My balls hang in the balance.”

I thought of the mythical statue at Rhodes, presiding over intercultural trade and commerce, and about boba, trapped between cultures today. As a cultural export, as a marker of the migration of people and labor from Asia, boba does hang in the balance. Not quite one world, not quite the other.

In many ways, Loose Leaf’s marketing and naming seems to be a perfect example of the evolution of what the concept of “tea” means, from Asia to America, from 1906 to 2022, through a twisting gyre of time and space, to end up in the plastic plant wall of a Loose Leaf in New Haven, Connecticut.

Boba, when it first came to the U.S., was categorized by the artificial powders, colors, and flavors that Loose Leaf now disavows. While perhaps the moralizing question of authenticity—whether or not the evolution of boba has been a “good” or “bad” thing—is unimportant, what is notable is understanding its journey: as a commodity, the vast distance it has traveled; as a cultural practice and tradition, the long span of time it has endured. My feelings about boba are complicated—it feels good to know that American people are accepting of a drink with Taiwanese origins, that they would be willing to try a beverage with pandan in it. But I think about telling myself comforting pieties in the acceptance of boba’s popularity, that I might just have to accept the fact that I will feel conflicted about white people drinking boba, unaware of its larger history, for the rest of my life.

During my brief tenure at Loose Leaf, I had to remake many drinks. I would pour out the drink in the sink, milks of all colors swirling down the drain, down into the belly of the hidden sewer system. The boba would be left behind, sticky balls clumping up at the drain. I had to stick my hand directly into the ballish void to force them down the drain, which was always a slightly repulsive but nonetheless deeply satisfying feeling.

I remember my fists full of boba, cupping humanity’s tapioca in my teacup of a hand. Then I squished them down. ∎

—Camille Chang is a sophomore in Silliman College.

7 TheNewJournal November 2022 Points of Departure

Small spherical spill at Loose Leaf High St. sometime in October, with a mysterious sugar trail leading into the distance.

Camille Chang / The New Journal

Wading for Hope

By Hanwen Zhang

In John Cavaliere’s shaky iPhone recording of a late-summer rainstorm in 2021, a manhole cover at the intersection of West Rock and Whalley Avenue has blown off, and become a spewing, 2-foot-high fountain. Water— mired to an unsettling blackness—roils and sloshes against the side of his porch. The cars that manage to pass flash their emergency blinkers as they squelch through the flood, tires half submerged in the filthy mix of sewage and runoff. Raindrops streak slantwise through the frame. The water is unstoppable; the water is everywhere.

Cavaliere, owner of the antique shop Lyric Hall, has lived through violent floods for the past ten years. He has plenty of footage to show for it—videos of him trekking down the stairs in the middle of the night to find a pool of grayish water at calf-level in the basement, lapping at wooden chair legs and picture frames. Along with the video clips, which he keeps in the hopes of showing the city officials, he’s typed up the measurements of every flood on a sheet of printer paper. “On May 7, 2011 there was 3 feet. On August 15, 2012,

there was 4 feet, 2 inches,” he reads. The numbers only grow, tending in the same direction as the sea levels in Long Island sound. “In July 2021, 6 feet, 5 inches. In September 2021, that was almost 7 feet.”

He sets the folded sheet on the wooden end table near the display window. The two of us are standing in Cavaliere’s small, one-story shop; it’s October, 2022. There’s a deep sigh. “[The floods have] taken out the HVAC [Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning] systems, the heating [and] air conditioning systems, so many times I can’t keep up.” Cavaliere, who refurbishes old artwork and repairs gilded picture frames for a living, used to keep his workshop in the basement, until repeated flooding events forced him to relocate to the main floor. His gilt molds and picture frames now lie sprawled across a storefront table. He tries not to think of all the antiques and artworks he’s lost over the years.

Today, the store has no heating. Instead, Cavaliere uses a cast-iron wood stove squatting in the center of the room. He took the furnace out of the basement years ago, fearing that a flood might reach his home’s electrical panels. If any

electrical panels got submerged and he accidentally stepped into the water, he explained, “I could get electrocuted.”

Cavaliere and his fellow Westville residents have watched these sewage overflows increase in frequency against a trend of rising sea levels and intensifying storms. They’ve sent dozens of emails to state and local officials, which all go either largely unanswered or forwarded to other representatives. Just last month he sent a sample of floodwater from near the basement stairway to Baron Analytical Laboratories. The results came back the next day, concluding that fecal coliforms in the water “were too high to accurately count.” When the water dries, streets and sidewalks are left with toxic residue and bacteria. “In other words, you know, we could get E. coli, Hepatitis A, typhoid from all these microbes.”

Flooding has upended Cavaliere’s life. “It does something to you all these times,” he said. “It’s traumatic.”

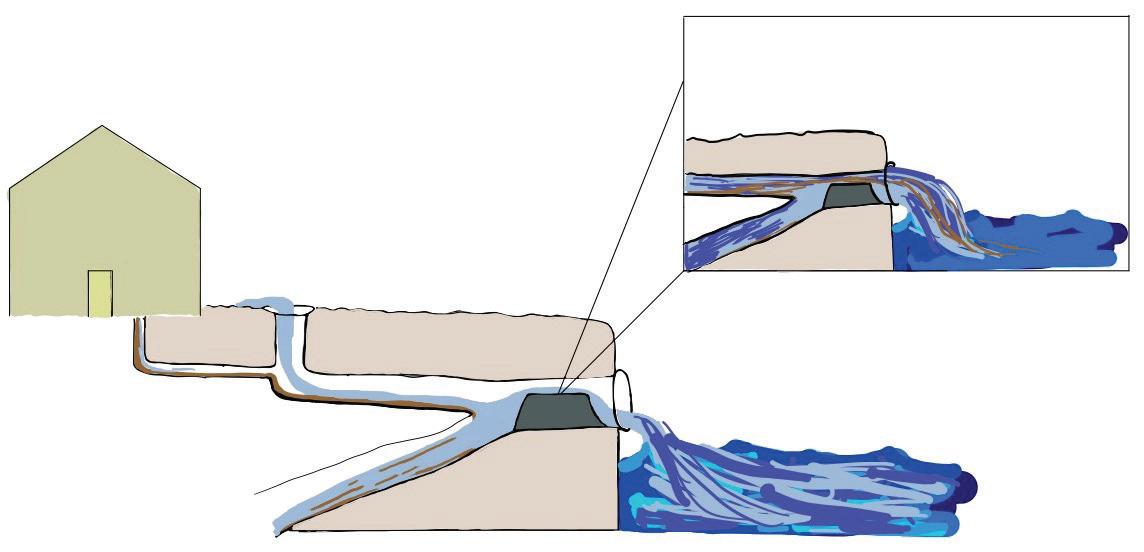

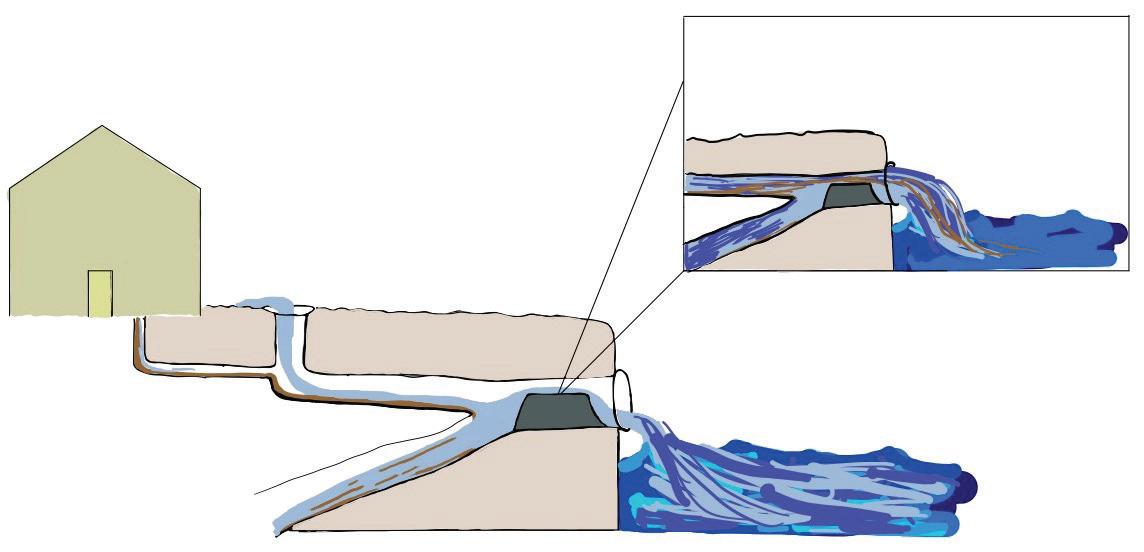

Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) is common in cities with older wastewater infrastructure, according to Colleen Murphy-Dunning, director of

8 November 2022 TheNewJournal

As sea levels rise, New Haven is seeing an increase in flooding that carries sewage and diseases with it. The Urban Resources Initiative is working to implement the infrastructure to change that.

Snapshot

the Urban Resources Initiative (URI). Most infrastructure built throughout the mid-to-late 1800s was designed with a single sewage pipe. Waste from toilets and bathtubs would combine with stormwater runoff and be transported to the processing facilities in East Shore.

The single pipe design quickly retired in the years following the 1970 Clean Water Act, after officials realized that it was causing waste to be directly discharged into the rivers. During heavy rainstorms when the water volume exceeded carrying capacity, the single pipe system would resort to an “outfall”—a safety valve that expelled untreated sewage straight into the rivers. Cities like New Haven had been washing feces directly to the Long Island Sound. Under the Clean Water Act, this wastewater system would be legally required to improve.

At least, it was supposed to be. Despite the intentions of the Clean Water Act, New Haven has been slow to develop its infrastructure. Most of the city’s historic neighborhoods—downtown, Wooster Square, Dixwell, Westville—continue to use the

combined sewer system.

There are more immediate consequences to the single pipe system than feces in the rivers. Faced with more sewage than it can handle, enough pressure builds up to pop manhole covers off and send its contents spilling all over the street. “It’s pretty nasty,” Chris Ozyck, URI’s associate director, said as we drove down Front Street in his pickup. He pointed out the townhouse complexes on the slope to our right, where stormwater often rushes down and overwhelms the pipes. As it moves downhill, the sewage-runoff mixture often gets backed up near low-lying areas and floods the streets.

Like most historic urban areas, not all of New Haven’s 555 mile-long sewage system is the same. Most streets constructed farther from downtown now use two pipes—one which specializes in collecting runoff stormwater from the catch-basins, and another that connects to each home’s sewage system. Doing so prevents the sewage flooding from happening.

The situation in Newhallville, a neighborhood in New Haven’s Ward 22,

is one such instance of this. Though Ozyck told me that some basements in the neighborhood had been flooding, the culprit seems to be purely runoff for now. Most of Newhallville’s streets have two sewer pipes, which has so far spared its residents of the feces-laden horrors. Hunter Irwin, a local resident on Shelton Avenue, moved here for his job at Yale-New Haven Hospital during the beginning of the pandemic and has braved three years of unrelenting storms. He admitted that runoff stormwater can still be a problem—it collects on the curbside and the empty lot across the street, especially during late summer thunderstorms—but so far, it hasn’t been much of a concern.

Dawn Henning, a New Haven city engineer, said that the city has been working steadily to outfit older districts with separate sewer pipes. That’s where URI has stepped in. As part of an effort to divert excess runoff from entering the sewage pipes, the nonprofit applied for grant funding and accepted contracts with the city government to install bioswales–trenches filled with shrubs and vegetation that receive runoff

9 TheNewJournal November 2022 Layout by Meg Buzbee

Hanwen Zhang / The New Journal

With water levels rising, the observation deck at the end of Clifton Street in Fair Haven is crumbling into the sound.

During heavy rain

Under normal conditions

water–in the most flood-vulnerable corners of New Haven. Since 2014, Ozyck and his crew have installed almost four hundred of them across the city.

On a Friday afternoon in October, he and I visited the very first bioswale in New Haven, just outside the Berzelius secret society on Trumbull Street. The rain from the night before collected in tiny puddles by the curbside. The lower leaves of the bioswale’s inkberries and daylilies glistened with water droplets. The soil in the swale felt cool and damp to touch, a sign that the plants in the bioswale had been busy filtering away

the runoff. The idea was to return rainwater back into the soil, where it would be taken up by street trees and absorbed into the water table.

“It’s mimicking what nature wants to happen with water, which is that it should go through soils and down and recharge the subsurface water light table,” Murphy-Dunning said. In the process, the soil ends up cleaning the water in ways that traditional treatment plants do not. The bioswale’s success on Trumbull exceeded their initial expectations: by naturally filtering the run-off, it managed to save a street that had long suffered from chronic flooding.

Climate change has only intensified these sewage overflow events. “The more we experience sea level rise and just higher and higher levels in the harbor, the more that reduces the capacity of our storm system and . . . the more we see that flooding,” said Henning.

Global warming’s effects are beginning to be felt in a city that sits right along the water’s edge. “There were a series of storms that happened [in] 2010 through 2015, in addition to hurricanes Sandy and Irene, that were really intense [and] had high return frequencies,” said Henning. During that time, ten- and twenty-five-year storms swept through the city almost yearly. That hasn’t improved: storms that are statistically only suppposed to occur once every five to ten years are hitting New Haven annually, explained Henning.

Streets like Quinnipiac Avenue and

neighborhoods like Fair Haven have already started eroding. “What used to be a fifty-year storm is now a ten-year storm,” said Ozyck. In other words, a storm with a severity seen only once every fifty years is now occurring in every ten. On Front Street, he showed me homes facing the Quinnipiac River with partial-underground basements that—like Lyric Hall—have experienced a significant uptick in flooding. From the end of Clifton Street, we saw a building partially sinking into the river. The guardrail of the outlook we stood on was just inches away from touching the water itself. Rising sea levels, Ozyck said, has only increased the odds of flooding. Water from the riverbanks will naturally spill onto the streets during an intense rain event, stressing the already aged parts of the city’s sewage system and threatening to make overflows of Westville’s kind dramatically more frequent.

Part of preventing these sewage outpourings will therefore require protecting the city from floods. Single sewer pipes like those in Westville are beginning to overflow with greater regularity as ever-intensifying flood events strain their capacity. Less flooding, then, would mean less overflow. After Hurricane Sandy and Irene hit in 2011, the engineering department received grants from the state and federal government for future flood protection. One of them, the Community Development Block Grant, awarded $4 million to studying green infrastructure development in the Long Wharf area. The research, which

10 November 2022 TheNewJournal Snapshot

OUTFALL TO RIVER

COMBINED SEWER OVERFLOW

TO TREATMENT PLANT

Diagram of a combined sewer system.

During heavy rainstorms, the single pipe system expels untreated sewage straight into the rivers.

Hanwen Zhang / The New Journal

Illustration by Meg Buzbee

John Cavaliere shows me photos of prior flood damage at Lyric Hall.

Storm drain

Sewage

Dam

Henning was responsible for, explored potential green solutions.

Long Wharf, which is directly beside the Long Island Sound, is currently one of the areas most vulnerable to flooding. The first phase of their proposed FEMAgrant project will expand Long Wharf’s current drainage capacity by constructing a 10-foot diameter pipe from the police station out to the harbor. Another project, led by the Army Corps of Engineers, has plans to build a flood wall along the sea-facing I-95 and install a pump station. In plans to protect the city from sea level rise roughly half a meter higher than the national average by 2050. Combined, the total costs work out to roughly $195.8 million.

The completion dates of both projects remain uncertain. The tunnel proposal is currently under review, which Henning admitted “can take a while.” After the agreement, she expects another six months for permitting and two years of construction. The flood wall awaits two years of design and a three- to four-year construction period.

Bioswales, meanwhile, have provided a faster—and possibly more

efficient—short-term solution for the city. “Green infrastructure is much less disruptive to install,” Murphy-Dunning said. One of the greatest challenges to updating the single-sewer system is its cost and labor: adding another pipe calls for digging up the entire road, creating a trench, and connecting the newly-laid pipe to every curbside catch-basin. By collecting runoff on the streets, bioswales help ease the strain on the existing singlepipe sewage system.

Murphy recognized the importance of the city’s current flood-protection projects, but she also brought up the importance of managing its existing impervious surfaces. Man-made materials, such as asphalt, increase the odds of flooding by preventing runoff from entering the ground. And while larger drainage pipes will certainly help, the flooding will only return if the city continues to develop over existing green spaces at the rate it currently is.

Henning tells me that the city itself has no jurisdiction over combined sewage. The engineering department only oversees storm drainage; the sanitary system is managed instead by the

greater New Haven Water Pollution Control Authority, a quasi-private entity that has its own long-term control plans. However, Henning did note that “they are under consent order by the [Environmental Protection Agency] to manage the two-year six-hour storm and to have essentially no overflows.”

As it waits for approval on its landmark projects, the city has continued to take steps towards flood resilience. Some of its smaller projects include replacing hundred-year-old clay pipes and cleaning curbside catch-basins.

With grant funding used up, bioswale construction has stopped. Its maintenance remains in the hands of

11 TheNewJournal November 2022

Snapshot

Cavaliere and his fellow Westville residents have watched these sewage overflows increase in frequency against a trend of rising sea levels and intensifying storms.

John Cavaliere recently installed a water valve, which will prevent sewage from overflowing in the event of a flood.

Hanwen Zhang / The New Journal

URI. During our meeting Ozyck pulled his truck over to the side of Grove Street, walked out, and tugged out a mat of browning red oak leaves from the bottom. Bioswales have to be constantly monitored and maintained to function properly, he said. Repairing broken guardrails, granite edging, and removing yard-waste is a months-long project for the nonprofit.

“I think we try to work on all scales,” Henning said. She looks forward to running studies using a geographic imaging system that will help the city capture more data. For areas like Westville’s Whalley Avenue and Forest Road, she noted that “we’re kind of in the study phase of the flooding.”

And while larger drainage pipes will certainly help, the flooding will only return if the city continues to develop over existing green spaces at the rate it currently is.

Getting the resources and making sure there is enough to go around will take time. Making sure every neighborhood receives the funding they need, however, is easier said than done. “We get this investment for downtown, but how does it appear in some other part of the city . . . ? It’s tough,” she said.

On September 6th, 2022, New Haven received 4 inches of rain in six hours—a month’s worth of precipitation packed into the span of a day. Rainwater streamed down streets, bogging cars and school buses. At Yale, Bass Library flooded; Benjamin Franklin’s dining halls seeped water; and the floor of basement butteries grew slick.

That day, in the basement of Lyric Hall, Cavaliere recorded 9 inches.

As a densifying urban area, New Haven faces a unique set of challenges. The city has to contend with runoff along concrete surfaces and rising sea levels, bearing the brunt of both inland and coastal flooding. “We’re kind of getting it from all angles,” said Henning.

Back at Lyric Hall, it is mid-October and not quite yet the tail of fall. Sunlight

sifts past the balcony, through the windows, onto the refurbished Persian carpet at the shop’s entrance, like any other day. The only traces of last month’s flood might be the basement’s faint mustiness as Cavaliere shows me the ball valve he installed. Closing it would shut the pipe that leads to the street sewer main and keep sewage from backing up into the toilet. Now, he explained, the plan is to apply for grant funding that would lift his storefront an additional two feet and waterproof the building’s warped foundations.

The back of the house is paintpeeled and sagging. Recently, though, a friend had helped repair the side of the basement. Cavaliere looked out at the pool of golden leaves across the street. Despite all the challenges he has experienced, he’s still hopeful: “It’s a miracle that I’ve managed to survive all this but I think it’s because I just feel so loved by the community and I love my community, and I am doing exactly what I want to do in my life.” ∎

—Hanwen Zhang is a junior in Benjamin Franklin College.

12

Snapshot

Edgewood Park’s former soccer field has returned to marshland, flooding regularly every summer.

Hanwen Zhang / The New Journal

Paradise in Miniature

That’s what Julia once called our neighborhood, half-joking. We sit in the air-conditioned Starbucks and she says, heaven is a place on Earth, Starbucks is a place on Earth, and I finish her sentence: so Heaven is Starbucks. Now we’re laughing, of course ironic about neoliberal bliss but there’s a part of us that means it, wants to languish in these velvet chairs forever. Julia recounts to me the story of Job, all that was given and taken away by God. We talk about her gamer ex-boyfriend who is wasting his brief store of potential. She ended things and misses him. We are both so greedy, I tell her on the park bench now, devouring cold peanut noodles from the to-go container. We hear an organ from the church service, priest’s deep voice, body of wafer, blood of wine. We rush to the door and peer in, noses pressed to the stained glass, anthropologists of this neighborhood and its ambient humidity. We hold each other’s hands and wait to ascend, to be let in, knowing we’re Jewish and we’re stoned and we won’t, we fucking won’t.

—Ella Goldblum

Lachrymose for Chinatown

E. says it looks nothing like it used to—the robustness and the feel of it is gone. We walk slowly from block to block glowing under the moonlight and the dripping neon silhouettes of storefronts, of provision, and of humanity. It’s been effaced, it’s been erased, it’s been eradicated. A small space, already designated for a people, sequestered further and further—a nation condensed into a city condensed into a town condensed into a district condensed into a small boat rocking endlessly on an uneven and cruel ocean, waiting to topple and capsize. Squashed in between a trendy French bistro and an upscale ‘dirtbag’ bar is the stall we grab dinner at. The aunty firmly places our fried dumplings in a styrofoam box with chopsticks—E. tells me that the aunty likes me, but there’s not a hint of kindness in her eyes, how could there be? It’s too much to ask someone to be kind when all they’ve known is violence. As we plop the steaming jiaozhi in our mouths, E. points out a mural of pigeons playing mahjong. Their feathers are bright and multi-colored. How do they hold the tiles? How do wings, tools of migration and transit, grab a hold of something in this world? There’s another one across the street of a lion dance, the lion’s head swallowing a hongbao as a diverse group of onlookers clap in joy. The lion, a symbol of dominion and masculinity in the west, is representative of community here. We bounce from mural to mural until it leads into an alleyway. White people are spilling out of a bar into the street, their faces are split open in drunken smiles. We’ve stopped in front of a mural of Sun-Wukong, the Monkey God. When I was a child, the only way I could even stand to learn Chinese was through the tales of his mythical journey. He is faded—his golden fur melted to jaundice and Jingu Bang looks small next to the large truck parked next to him. On his face, someone’s pasted a Grateful Dead sticker. There’s a slight pause in her body as E. stares, calculating this vandalism. The white people are growing wilder, their shouts definitely reaching the tops of shop houses, waking those inside trying to sleep. E. reaches up, grabs the edge of the sticker, and violently peels it off, revealing his gleaming face and that mischievous grin still smiling . . .

13

—Jools Fu

Those Who Stay

New Haven Public School teachers are leaving for nearby districts with higher wages.

November 2022 TheNewJournal 14

It’s not easy to make the choice to stay.

Leslie Blatteau speaking at the March For Our Classrooms rally in March, 2022.

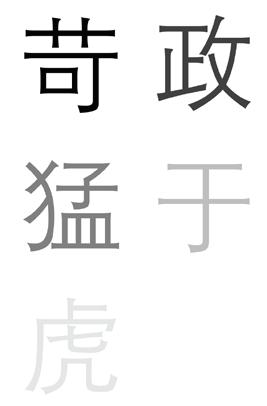

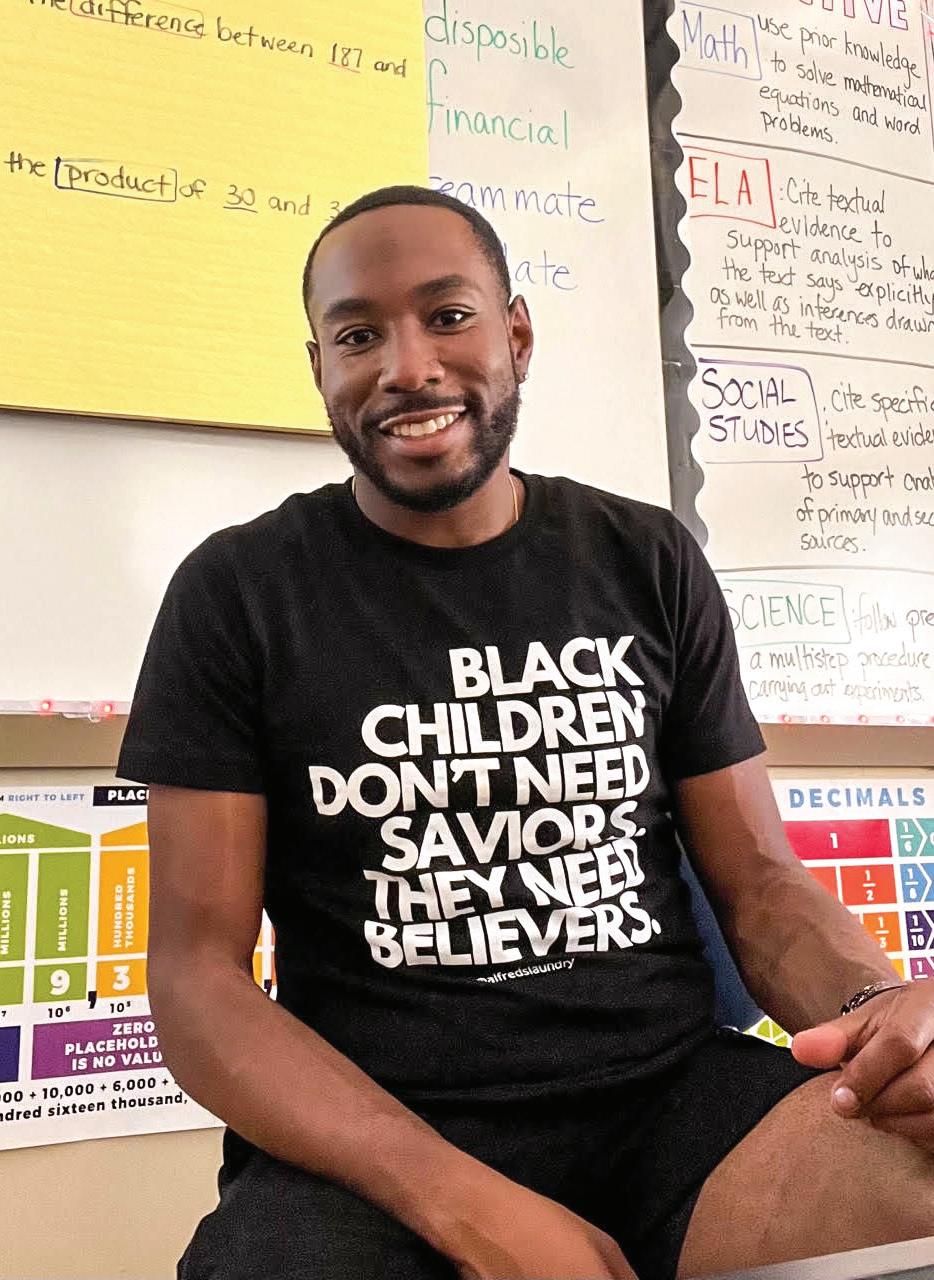

Da’Jhon Jett in his classroom.

Snapshot

Image courtesy of AFT-CT

By Caroline Reed

It’s 8:35 on a weekday morning, and students are filing into the Augusta Lewis Troup school in New Haven. Visible through the glass face of the building, clusters of middle-schoolers chat unhurriedly. Backpacked students bottleneck at the school’s front doors and spill out onto the wide stretch of pavement outside.

Sixth-grade teacher Da’Jhon Jett has been preparing in his classroom since 7:15 this morning. Today, his three gifted and talented students—students who read well above a sixth-grade level—might finish independent work early. Jett hopes that they’ll use the advanced books, purchased with his own money, to occupy themselves while he teaches four of his other students to identify the letters of the alphabet. Of his twenty-one students, four are learning English as a second language. Four are working on letter identification, and six need more special education support than they currently receive. Jett is not trained as a teacher of special education or English Language Learners (ELL s). But since Augusta Lewis Troup lacks enough specially trained educators, these students have landed in Jett’s classroom.

Low pay and tough working conditions have triggered a mass exodus of teachers from the profession. Nationwide, starting teacher salaries have sunk to the lowest level since the Great Recession (after adjustment for inflation). Pay—decided years in advance by union contracts—has not kept up with the rapid rise in cost of living. Since January 2021, rates of resignation have grown in educational services faster than in any other industry because of low pay and overwhelming expectations.

In New Haven, the impact on students is especially dire. The city can’t compete with the salaries and working conditions of other Connecticut districts, which benefit from more local property tax revenue. Teachers are leaving New Haven to fill better-funded vacancies in wealthier districts, primarily in Fairfield, leaving the teachers who stay to pick up the slack. All six of the teachers I

interviewed for this article know people who recently left the district.

Ryan Boroski is a Social Studies teacher at the Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School. “Two of my friends left this year,” he told me. “One was going to make 50 percent more and one was going to make 35 percent more.”

When some teachers leave, class sizes increase for those who stay. Steve Baumann, an eighth-grade science teacher in his tenth year at the Conte West Hills school in New Haven, explained how classroom management suffers in large classes: “If you have twenty-five students and you have even three that are really off-behavior, it can really throw off the dynamic of the whole class.” Jett also said that he often feels unable to teach effectively with so many students in the classroom. Leslie Blatteau, President of the New Haven Federation of Teachers Local 933, said, “Right now we’re juggling the jobsof many people . . . it wears on energy and morale.”

All six of the teachers interviewed had classes larger than twenty-five students. Eighteen or fewer is generally considered ideal.

J ett, who is Black, began teaching because he wanted to show students of color that “we can lead in the classroom.” However, with increasing pressures from the school to cater to students with vastly different needs, Jett told me, he has little time to get to know his students one-on-one.

Before moving to New Haven, Jett taught in Hamden, where average proficiencies in math and reading are 43 and 50 percent, respectively. In New Haven, these rates are 22 percent and 35 percent. Jett attributed the discrepancy in achievement between New Haven and Hamden in large part to overwhelming class sizes. This year, Jett was relieved that his class only had twenty-one students,

a decrease from last year’s twenty seven-student class. But he still struggles to get everyone on the same page. Of the low reading levels among some of his students, Jett told me, “I didn’t know until I got there. I didn’t believe it until I got there. I just didn’t think it could be that low.”

Though conditions of teaching in New Haven—class sizes, low pay, and long hours—have induced some teachers to leave the district, the six New Haven teachers I spoke with are committed to helping their New Haven students. Teachers cited New Haven’s unique diversity and the new union leadership’s commitment to improving teaching and learning conditions as reasons for staying. The New Haven school district is in the top one percent in the state for racial and ethnic diversity, and 88 percent of its students are Black or Latinx.

Blatteau, who has taught social studies in New Haven since 2007, won her election to union president in December 2021. She ran alongside a slate of candidates that included Wilbur Cross High School counselor Mia Comulada as secretary. Before the election, Blatteau and her colleagues asked teachers what they wanted to change about their jobs. Many responded that their “working conditions are students’ learning conditions,”

15 TheNewJournal November 2022 Layout by Kevin Chen

Image courtesy of Da’Jhon Jett

Da’Jhon Jett outside of the school welcoming students, 2022.

Image courtesy of Da’Jhon Jett

$64,355

The amount Jett would make in Norwalk, where the median household income is $89,486.

I-95

Norwalk

$77,721

The amount Jett would make in Westport, where the median household income is $222,375. Westport is only a 35 minute drive away from New Haven.

and that students and teachers have “shared concerns, experiences, values, and should have shared action.”

The concerns that Blatteau and her colleagues saw emerge in conversations with teachers—especially the stagnant pay, despite growing responsibilities— were similar to those I heard. All of the teachers I interviewed said they worked more than the 6.75-hour day stipulated in their contract. Kris Wetmore, a visual arts teacher at New Haven’s Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School, told me she’s improving her work-life balance and trying not to work beyond 7:30 a.m. to 2:15 p.m., “the hours I’m getting paid for.” Still, Wetmore admitted that she usually has to get to work early and spend some time working on weekends to prepare for the week’s lessons. Jett added, “If any of us just worked for the 6.75-hour day, no one would get anything

done.” No one felt that their pay fairly compensated these long hours. Boroski feels low teacher pay reveals the city’s priorities. “I know no one gets into this job for the money, but the salary in New Haven is a reflection of the lack of respect for teachers.”

Teachers have long been subject to lower salaries than similarly educated professionals for their demanding work. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Blatteau explained, wages stagnated when the city negotiated a pay freeze that stopped the regular schedule of raises stipulated in the union contract. Since teacher pay schedules lay out pay for a teacher’s entire career, a one-year pay freeze meant that teachers were set back a full year in their schedule of raises.

“This really robs teachers who are going into retirement because their pensions

The city can’t compete with the salaries and working conditions of other Connecticut districts, which benefit from more local property tax revenue. Teachers are leaving New Haven to fill better-funded vacancies in wealthier districts, primarily in Fairfield, leaving the teachers who stay to pick up the slack.

$50,440

The amount Jett currently makes in New Haven, where the median household income is $44,507.

are dependent on their salary,” Baumann said, emphasizing the impact of pay freezes on long-term teachers.

Local activists and union organizers have attributed the deficit in New Haven public school funding to Yale’s paltry contributions to the city. Davarian Baldwin is a political science professor at Trinity College and Director of the Smart Cities Lab, which facilitates collaboration with eleven cities on problems involving municipal services including public transportation, housing, and schools. In the past, Baldwin has worked with New Haven Rising, a local activist group whose demands include an increased voluntary contribution from Yale. Baldwin said that top colleges like Yale are “built on the plunder of their cities,” and he highlighted Yale’s property tax break as a prime example.

Daniel HoSang is professor of Ethnicity, Race and Migration at Yale and a founding member of the Anti-Racist Teaching and Learning Collaborative. He, Blatteau, and Wilbur Cross counselor Mia Cormulada helped me understand the complex structure that determines public school funding, which in turn determines teacher salaries. School funding is allocated at a few levels: first, the city of New Haven determines its annual budget, which includes

16 November 2022 TheNewJournal Snapshot

Data from the New Haven teacher’s union

I-84 I-91

Westport

map by Kevin Chen

New Haven

all of the money that will be used for municipal services in the city. This money comes primarily from property taxes (New Haven’s city assessor, Alex Pullen, did not respond to questions about local funding, which accounts for 58.8 percent of total school funding).

Funding from property taxes does not include money from Yale’s voluntary contribution to the city, which was $23.2 million this year. In 2019, activists in New Haven Rising estimated that Yale would have paid $146,079,896 if its property was taxed as private, 40 percent of the $364,659,346 total public school budget for New Haven that year. Yale’s property holdings in New Haven are increasing every year.

The district gets a small amount of funding—approximately 4 percent in 2020—from the federal government, and the city also gets 37.3 percent of school funding from the state, including money from the Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) program. The PILOT program gives $90 million in state funding to New Haven to make up for property tax revenue lost because of the city’s large swaths of untaxed property, mostly owned by Yale and Yale New Haven

Health. When it comes to Yale’s tax break, this still leaves about $56 million unaccounted for.

Baldwin likened Yale’s tax break to a subsidy that New Haven grants the University each year. When discussing his work with New Haven Rising, Baldwin said, “We want to create policies that induce schools like Yale to be better neighbors.” Blatteau added, “Yale could really right the wrongs of the historic underfunding of public schools that they have contributed to by taking up so much untaxed property.”

Lauren Zucker, Yale’s associate vice president for New Haven Affairs and University Properties, responded to questions about Yale’s relationship with New Haven in an email: “Yale is proud of its commitment to our home city . . . the University pays approximately $5 million in property taxes . . . making Yale among the top three real estate taxpayers in New Haven.” She also

emphasized Yale’s cultural contributions to the city, including the University’s Pathways to Science and Pathways to Arts and Humanities programs for New Haven Public School students and Yale’s public museums.

Zucker cited Yale’s recent “historic increase” in voluntary payments to the city, and this year’s $23.2 million contribution. $23.2 million is 15.7 percent of what Yale would pay if its buildings were taxed like private property, according to the 2019 calculations from New Haven Rising cited earlier. Yale’s voluntary contribution still leaves New Haven about $33 million short in property tax revenue.

HoSang added that Yale is not entirely to blame for the harms its untaxed property has wrought on the city. “After all, Yale didn’t author the laws that keep it from paying taxes,” he said. Yale’s status as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization means that the school is exempt from all taxes on educational property

I-95 I-395 17 TheNewJournal November 2022 Snapshot

Blatteau added, “Yale could really right the wrongs of the historic underfunding of public schools that they have contributed to by taking up so much untaxed property.”

Teachers at the March For Our Classrooms rally in March, 2022.

Images courtesy of AFT-CT

buildings where instruction takes place.

New Haven Mayor Justin Elicker acknowledged that there is much work to be done to secure adequate funding for public schools, but he said, “We’re seeing both [Yale and the state of Connecticut] take significant steps to address these problems.” Elicker attributed the lack of money for schools to Connecticut counties’ overreliance on city-limited property tax revenue. Property taxes from suburbs and rural areas around New Haven don’t contribute to the city’s revenue. In contrast, Elicker said that other states distribute funding by county, spreading property tax revenue more evenly. New Haven schools would be better funded if the city adopted this system. Still, in Elicker’s view, “the city of New Haven works very hard with very limited resources to support funding for our public schools.”

Even within the district, however, funding is unequally distributed. Jett told me that the Wexler Grant Community school, a mile away from his school between Dixwell Avenue and Canal Street, has two sixth-grade classrooms and twenty-three sixth graders. In smaller settings, teachers can work with each student to meet their needs. The school district’s spokesperson, Justin Harmon, explained how funding is allocated in an email: “Neighborhood schools vary in enrollments as the population around them swells or declines,” he said. “Wexler is in a period of decline. Over time, the district makes staffing and program adjustments in an effort to rebalance the distribution of students and teachers from school to school.” Blatteau maintains that the public school deficit is an illusion: “If schools were a genuine priority,” she said, “the city would find the money.”

into his classroom.

To make up for the things his school can’t buy, Jett keeps his classroom stocked by spending his own money. While we were on the phone, Jett pulled up his Amazon purchase history for the last few months, going back to just before the school year started. Adding up the money that he spent on books, paper, pencils, markers, craft supplies, and toys demonstrating mathematical concepts, Jett estimated that he spent close to $4,000 on supplies for his classroom this summer. What the school is able to provide often arrives after the year has started. Teachers who didn’t make similar purchases sometimes begin the year without books. Baumann has experienced these delays, and now buys most of the materials needed for experiments with his own money. All of the teachers I interviewed said they spend some of their own money on classroom supplies, but amounts ranged from a few hundred dollars to Jett’s $4,000. Still, they choose to stay.

whom are teachers themselves—worked to increase member engagement in the union, responding to criticisms that there wasn’t enough information available about union activity.

Though he acknowledges that pay and conditions are better at other schools, Jett said, “New Haven is one of the only districts in Connecticut where kids’ and families’ voices are heard, where we’re really trying to fix these problems.” Where other districts promised inclusion but often fell short, in New Haven, “everyone’s doing their best to get kids up to where they need to be.” Still, as Blatteau and her colleagues in the union understand, teaching in New Haven is unsustainable for many teachers.

Things are looking up, though. In November, the city’s Board of Education approved a new teacher contract that will incrementally increase salaries over three years, according to the New Haven Register. In July of 2023, wages will increase 5.9 percent, then 4.9 percent the year after, and 3.9 percent the year after that. By the 2025–26 school year, the starting salary will be $51,421, compared to the current starting salary of $45,457. It’s an overdue improvement, but it might still not be enough.

Adding up the money that he spent on books, paper, pencils, markers, craft supplies, and toys demonstrating mathematical concepts, Jett estimated that he spent close to $4,000 on supplies for his classroom this summer.

When asked if he has considered leaving the district, Baumann said, “I think about it every day.” He knows several teachers who have left just this year. Still, he plans to stay for the next year and a half until he retires: “I honestly enjoy the eighth-grade team teachers that I’m working with, and I’m probably staying here more for them than for myself or the kids right now.”

Blatteau said, “Teachers who switch districts love New Haven, but I don’t blame them.”

“Teachers are the most unappreciated and undercompensated [workers],” said Boroski. What’s more, New Haven teachers advocate for their students far beyond the classroom. Comulada recounted two trips to Massachusetts that she organized in 2019, rallying students and fellow teachers to support a student who had been detained by ICE.

I f Jett worked in Norwalk, a majority white town with a median household income of $89,486, he’d be making $64,355, according to a salary comparison chart prepared by the New Haven teacher’s union. If he worked thirty minutes away in Westport, a city that is 86.5 percent white and where the median household income is $222,375, he’d make $77,721. In New Haven, where the median household income is $44,507, he makes only $50,440. A portion of Jett’s modest paycheck goes back

Comulada agreed. “People need to feed their families, Maybe [leaving] is in their self-care bucket,” she said, acknowledging also that pay across districts “isn’t an even-steven.”

Those teachers who do stay in New Haven remain excited about the district’s potential, and Blatteau said that “this isn’t a crisis without an answer.” The union’s current leadership is advocating for the things rank-and-file teachers want, like smaller class sizes and pay that adjusts to the rising cost of living. In preparation for the election, candidates—all of

Students leave Augusta Lewis Troup at 2:50 p.m. . Under the hum of fluorescent lights, Jett stows the markers and crayons, sorts early-reader books and chapter books into their separate bins, and reorganizes math manipulatives. He keeps the supplies his paycheck paid for in good shape. A mile away at the Cooperative Arts and Humanities High school, Boroski and Wetmore do their ritual clean-up as well: Wetmore puts away all of her art supplies so that a health teacher can use the room the following morning, while Boroski rolls up the projector screen that he bought for his room. ∎

—Caroline Reed is a junior in Saybrook College.

18 November 2022 TheNewJournal

Snapshot

19 TheNewJournal November 2022 The healthy whole body cryotherapy that everyone is talking about!

Y

CT

-

C O M E A N D T R Y I T O U T @ M A C T I V I T

www.mactivity.com/free-pass 285 Nicoll Street, New Haven,

06511 (203) - 936

9446

After uncovering the World Mission Society Church of God’s presence on Yale’s campus, two writers take a closer look at the religious organization that has been accused by former members of being a cult.

Building a fromreligion A to Z

By Miranda Jeyaretnam and Sarah Cook

By Miranda Jeyaretnam and Sarah Cook

Kelsey M. had just turned eighteen when she was approached on the way back to her dorm in Seattle by someone asking if she’d heard about “God the Mother.” Curious, she agreed to attend a Bible study the next day, at the end of which she was baptized.

When she was first approached, Kelsey was new to the area, having just moved for college. She had no family or friends in Seattle. The people who had invited her to attend a Bible study looked around her age and seemed friendly, so she decided to tag along.

In a matter of weeks, she was in so deep that she was prepared to “literally die for the Church.”

Kelsey was recruited during what the Church calls a “short-term mission”, in which members from Los Angeles are sent to cities like Seattle to preach for about a week and baptize as many people as possible. “Everything they said to me made logical sense, for example, because they believe in a God the Father and God the Mother, they said just as every living creature on this Earth requires a father and a mother to be given life, in the same way, we have to have a God the Father and the Mother to be given spiritual life,” Kelsey said. “They use a lot of real life examples to justify or explain their doctrine, to make it more digestible.”

During such missions, Kelsey told us, the recruitment process is “sped up,” which means important, secret tenants of the Church are divulged earlier than usual. Perhaps their most important belief is that their founder, a twentieth century minister named Ahn Sahng-hong, is the second coming of Christ. Many other members that we spoke to only learned about Ahn Sahng-hong after several months in the Church. What Kelsey did not learn right away, though, was that Ahn’s spiritual wife—a living South Korean woman named Zahng Gil-jah— is God the Mother. She was told this explicitly only after three years in the Church, by which time she was in so deep that she didn’t think to question it.

The church that Kelsey joined is known as the World Mission Society Church of God, a religious Bible-based movement that was founded by Ahn Sahng-hong in South Korea in 1964. Kelsey told us that the Church teaches preaching members to only reveal its beliefs and practices bit by bit, because the more radical beliefs of the Church—such as the fact that God the Mother is very much alive—would “scare [newly recruited members] and they’re not going to want to listen to the truth.” The Church allegedly justifies this through a verse in 1 Corinthians that says, “I fed you with milk, not solid food; for you were not yet able to receive it.”

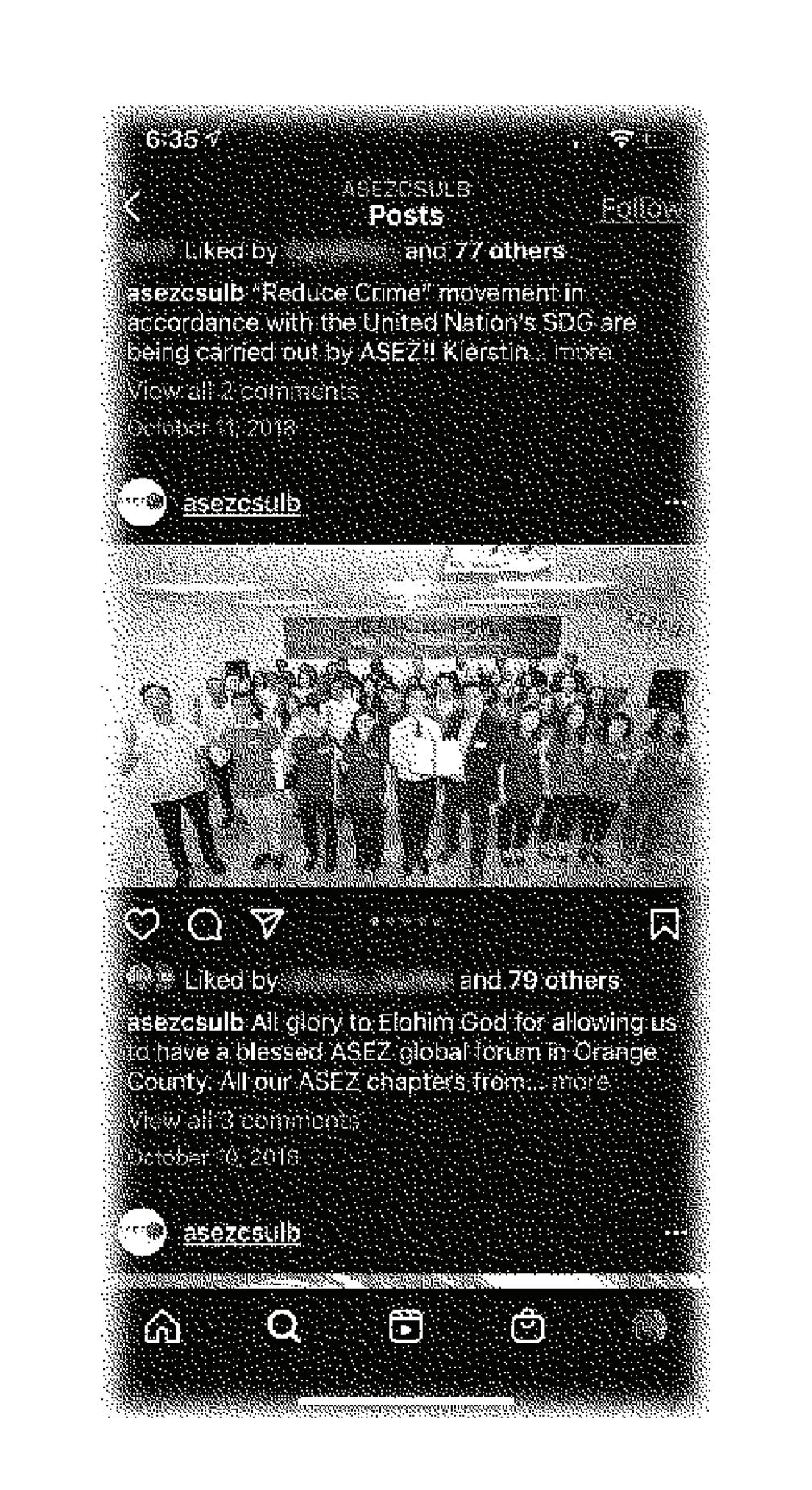

Last spring, a division of the Church known as ASEZ, or Save the Earth from A to Z, sought to establish a student organization at Yale. We investigated ASEZ for the Yale Daily News in April of 2022 and spoke to ten students who attested

to having been approached by members of the Church on campus, as well as a few who’d actually joined. One student, Charnice, who joined for a few months, was told to miss class and other extracurriculars to focus on her “spiritual family.” Another student, Davornne, became a Freshman Counselor (FroCo) while actively involved in the Church, seemingly seeking to recruit the first year students in her group and missing crucial responsibilities to attend marathon bible sessions. At the time that we interviewed ASEZ, the group was spearheaded on campus by Davornne, who has since graduated, but from student reaction to the article, we learned that there was a wave of attempted recruitment from as early as 2018. The Church’s closest location is in Middletown, Connecticut, but over the last year, they have mainly invited students to Bible studies at the Starbucks on Chapel Street.

Yale students might recognize the group’s recruitment tactics from personal experience. Usually in pairs, members of ASEZ would approach students in coffee shops or on the street between classes, asking if they’d want to join for Bible study. If the answer is no, a student might be subjected to a few minutes of earnest persuasion before they’re left alone. If the answer is “sure”, they’ll likely be invited to a Bible study at the Starbucks on Chapel Street or a room in Bass Library. Students on other university campuses have described being loaded into a car and driven to a church building, where they’ll sit down with other members for hours of worship, at the end of which, usually, awaits an impromptu, Do-It-Yourself baptism in the church bathtub.

We were able to meet Kelsey, and many of the other sources in this article, through a small online community of ex-members-turned-vocal critics of the World Mission Society Church of God. Kelsey told us that the Church’s “target audience” is young adults aged between 18 and 30 years old. “Basically, anybody who is not tied down with a family and can just dedicate their entire free time to the advancement of recruitment for the group,” Kelsey said. “That was number one. That’s why you see them on a lot of college campuses.”

But the question of the legitimacy of the Church, which has been accused by former members of being a “cult,” and the intense, often unsettling commitments it asks of its members, goes much deeper.

The Bible studies and church services that Kelsey attended were initially not held at a church, but at a member’s house. Every Saturday, she and other members would gather there from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. for three hour-long services, meaning that she was “constantly surrounded” by the same people. “When you start college, you’re very impressionable, everybody’s kind of trying to figure out the world around them at that time,” Kelsey said. “Everybody in the Seattle church at the time, we all just sat around one dinner table, so it was a bunch of people who had no family, no

22

Students on other university campuses have described being loaded into a car and driven to a church building, where they’ll sit down with other members for hours of worship, at the end of which, usually, awaits an impromptu, Do-ItYourself baptism in the church bathtub.

friends in the area . . . and we literally just became like a family.”

Things moved quickly for Kelsey. Her fellow members were all the friends she had in Seattle, and because she hadn’t previously read the Bible, she was quick to believe what they told her. For Kelsey, a lot of her first experiences in the Church weren’t immediate red flags—even if she was spending copious amounts of time at the church, it initially didn’t strike her as concerning. In fact, like all of the former members we spoke to, Kelsey described the tension between the Church as a toxic and controlling institution, and her fellow members being kind, friendly, and drawn to the Church for many of the same reasons as herself. This is what made it so hard for her, and others, to leave.

In July, we visited the New York City branch of the Church for their 3 p.m. service. We found the address on the internet, and at the front of the two-story office building was a sign that read “Ring the doorbell if the door is locked.” The door was not locked, so we entered through the glass doors into a makeshift waiting room with just an elevator. Certificates of philanthropic awards hung on the walls around the room. We stepped into the elevator to go up to the second floor, where the services were being held. But the elevator did not budge and the doors stayed open. After a couple of minutes, we stepped out and rang the doorbell—which had a Ring camera— outside the front door. Just then, the doors of the elevator closed.

As we debated calling the elevator again, the doors opened to reveal a tall man dressed in a gray suit. He began to question us: how did we know about the Church? Why were we there? Who’d invited us? Services were invite-only, we were told, for the protection of the members. It did not matter that we had called a week earlier and been told that services were open to all by someone who subsequently stopped answering our calls.

He instructed us to come back in half an hour for activities, when the service was over. So, we did. For the next thirty minutes, we sat kicking our legs on barstools at a restaurant next door, sweating in the New York City heat, debating our next move and guessing at what exactly “activities” might mean. But when we were let up to the second floor, there were now two men standing in front of the elevator door, barring our way. The second man, we found out, was Victor Lozado, the overseer of the New York and New Jersey branch. Members were being sent home early because of the heat wave, they said, so now was not a good time. It would be best if we could put our names down so they could contact us for a future Bible study. Members, all dressed in suits and blazers, despite the heat, streamed outside in twos and threes—but a few minutes later, they reentered the building through a door to the side of the main lobby. There was no indication that any of them were going home for the day.

T he origins of the World Mission Society Church of God are more complicated than the Church makes them out to be. Searching for information about Ahn online leads to a deluge of mixed information. The blog Examining the wmscog is run by a former member who is dedicated to unveiling the doctrines of the Church, and there are at least a dozen counter-blogs that attempt to hide and invalidate any criticisms of the Church. Googling “How can Ahn Sahnghong be the Christ” brings up pages of those counter-blogs, like The True wmscog and The True God the Mother, in addition to the Church’s regional websites. But there is little information about the man himself.

From what we were able to find, Ahn Sahnghong, a 46-year-old South Korean Christian minister, founded the Church in 1964 under the name Church of God Jesus Witnesses in Busan, South Korea. Born in the Jeollabuk-do province of South Korea in 1918, Ahn grew up in a Buddhist household. In 1946, he converted to the Seventhday Adventist Church. According to the website for the World Mission Society Church of God in Korea, he began receiving revelations from God in 1953, and in 1956, Ahn predicted that there would be the second coming of Christ within the next decade. In 1962, he was excommunicated from the Seventh-day Adventists.

Ahn taught a literal interpretation of the Bible, something he felt the Christian Church had distorted. He believed that Christian iconography like symbols of the cross was a form of idolatry; that the Sabbath should be observed on Saturday, not Sunday; that women should wear head coverings while praying; and that humanity is living in the end times, when the end of the world is imminent. In his books, The Mystery of God and the Spring of the Water of Life and The Bridegroom Was a Long Time in Coming, and They All Became Drowsy and Fell Asleep, he predicted that the world would end forty years after the creation of the modern state of Israel in 1988.

After Ahn’s passing in 1985, the original church split into two separate sects: the New Covenant Passover Church of God, led in Busan by Ahn’s son, and the Church of God Witnesses of Ahn Sahng-hong. The latter, which was rebranded as the World Mission Society Church of God in 1997, was led by Zahng Gil-jah and the general pastor Kim Joo-cheol. While the New Covenant Passover Church of God believes that Ahn was just a prophet of God, the World Mission Society believes he is God himself—and they believe that Zang is Ahn’s “spiritual wife”, and God the Mother.

Zahng is an ever-smiling 79-year-old woman living in South Korea. According to a letter allegedly written by her first husband Kim Jae-hoon, Zahng and Kim were married in 1966 and began going to Ahn’s church together. They had two children, but as Zahng became more and more involved with the Church, she sold

23

their house to pour money into the Church and began to neglect her family. Eventually, they separated in 1987.