To Care for a Community

Inside: Full Disclosure, Unlearning Surveillance, Leaves of Service

Dear readers,

A few weeks ago, we hosted our Bulldog Days event in a small room at the top of Phelps Hall. We did not belong there. Still, we set down our things and made it so—half-eaten bags of hot chips, a modest pile of tote bags, and enough Red Bulls to kill someone. We worried if people would come. Slowly, they did, and we welcomed a small cohort of five.

The New Journal began for us this way, too: a small group of editors, a small mess of junk food, and a small table at which we barely belonged. Over the past year, we have found a home here. This April, we welcomed back the people who have created their own homes in The New Journal, the people who have cared for this magazine over the course of nearly five decades. It seems this home is still as scrappy as they remember.

But as we all do this time of year, we begin as we leave.

In our board’s first issue, our stories interrogate the safe places many call home. Amelia Davidson’s cover story explores an approach to make New Haven a safer place to live—but some envision radically different ways to protect this peace. Megan Vaz parses out efforts to create systems of support against sexual violence, often at the expense of emotionally burdening our cce s. Elisa Cruz writes of the struggle to make New Haven Public Schools sanctuaries, rather than sites of surveillance.

While we work to make our existing homes more caring, we may negotiate the things that constitute them, creating something new yet familiar. Grace Ellis recalls her dear friend Allis’s path to the “irrevocable condition” of home. Connor Arakaki creates presence from absence as she weaves together fragments of her Indigenous Hawaiian identity. And to begin this issue as we end this letter, Ashley Chin introduces us to the found families of Elm City Games and the refuge to be found in play.

We are about to scatter around the globe, leaving some things behind and holding on to others. We hope you’ll take these stories with you as you go.

Editors-in-Chief Jabez Choi

Abbey Kim

Executive Editor Paola Santos

Managing Editor Kylie Volavongsa

Associate Editors

Naina Agrawal-Hardin Chloe Nguyen

Kinnia Cheuk John Nguyen

Viola Clune Ingrid Rodríguez Villa

Grace Ellis Netanel Schwartz

Aanika Eragram Etai Smotrich-Barr

Maggie Grether Anouk Yeh

Samantha Liu

Senior Editors

Amal Biskin Zachary Groz

Meg Buzbee Yosef Malka

Nicole Dirks Cleo Maloney

Lazo Gitchos Dereen Shirnekhi

Ella Golblum J.D. Wright

Jesse Goodman

Copy Editors

Yvonne Agyapong Adam Levine

Connor Arakaki Ella Pearlman-Chang

Lilly Chai Victoria Seibor

Mia Cortés Castro Lukas Trelease

Iz Klemmer

Creative Director Kevin Chen

Design Editors

Meg Buzbee Jessica Sánchez

Camille Chang Chris de Santis

Madelyn Dawson Miye Sugino

Karela Palazio Etai Smotrich-Barr

Charlotte Rica

Website Directors

Makda Assefa Serena Ulammandakh

Photography

Nithya Guthikonda Nour Tanush

Christian Robles

Members & Directors: Emily Bazelon • Peter Cooper

• Jonathan Dach • Kathrin Lassila • Elizabeth Sledge •

Fred Strebeigh

Neela Banerjee*

Anson M. Beard

James Carney

Andrew Court

Romy Drucker

Jeffrey Foster

David Gerber

David Greenberg*

* Donated twice. Thank you!

Thank you to our donors.

Matthew Hamel

Makiko Harunari

James Lowe

Chaitanya Mehra

Ben Mueller

Sarah Nutman

Peter Phleger

Jeffrey Pollock

Adriane Quinlan

Elizabeth Sledge

Gabriel Snyder

Fred Strebeigh

Arya Sundaram

Stuart Weinzimer

Steven Weisman

Suzanne Wittebort

Advisors: Neela Banerjee • Richard Bradley •Susan Braudy

• Lincoln Caplan • Jay Carney • Andy Court • Joshua

Civin • Richard Conniff • Ruth Conniff • Elisha Cooper •

Susan Dominus • David Greenberg • Daniel Kurtz-Phelan

• Laura Pappano • Jennifer Pitts • Julia Preston • Lauren

Rawbin • David Slifka • John Swansburg • Anya Kamenetz

• Steven Weisman • Daniel Yergin

Friends: Nicole Allan • Margaret Bauer • Mark Badger and Laura Heymann • Anson M. Beard • Susan Braudy •

Julia Calagiovanni • Elisha Cooper • Haley Cohen • Peter

Cooper • Andy Court

• The Elizabethan Club • Leslie

Dach

• David Freeman and Judith Gingold

• James Liberman • Alka

• Paul Haigney and Tracey Roberts • Bob Lamm

Mansukhani • Benjamin Mueller • Sophia Nguyen • Valerie

Nierenberg • Morris Panner • Jennifer Pitts • R. Anthony

Reese • Eric Rutkow • Lainie Rutkow • Laura Saavedra and David Buckley • Anne-Marie Slaughter • Elizabeth

Sledge • Caroline Smith • Gabriel Snyder • Elizabeth

Steig • Aliyya Swaby

• John Jeremiah Sullivan

• Daphne and David Sydney • Kristian and Margarita Whiteleather

• Blake Townsend Wilson

• Daniel Yergin • William Yuen

cover story

Peer-led policing alternative compass has seen a successful rollout in the past five months. But can an organization bankrolled by the City and run by Yale achieve radical aims?

By Amelia DavidsonYale’s cce program aims to revolutionize campus sexual misconduct response, but its student-led approach raises crucial questions about power and accountability.

By Megan Vaz 39point of departure

Ashley Chin explores a local game store challenging the gaming community’s conservative status quo.

crtitical angle

Unlearning Surveillance

As national conversations about policing in schools intensify, some New Haven Public School students question whether school resource officers actually make them safer.

By Elisa Cruzprofile

Leaves of Service

Eli Whitney student Allis Ozornia grapples with what it means to get a Yale education after ten years of reproductive justice activism in South Texas.

By Grace Ellispersonal essay

Metamorphosis

A writer reflects on Indigenous identity following Yale’s repatriation of the iwi kūpuna.

By Connor Arakakiflash fiction

West End Avenue

By Amal Biskin

By Amal Biskin

Isle

By Charlotte Hughes By Charlotte Hughescrossword

It’s March again

By Kylie Volavongsa By John Nguyen

By John Nguyen

Local Geography, by Adam Winograd.

image credits: Christian robles (top, front); etai smotrich-barr (bottom); nour tanush (back)

F rom that very first night I happened by Chapel Street, I was charmed. Maybe it was the hot pink facade that unapologetically spans three storefronts. Maybe it was the two lifesized kobolds—a kind of monster from Dungeons and Dragons (DnD)—that grumbled at me from the window display with their spears raised, like guardians at the shop’s front door. It was most probably, though, the ambience of Elm City Games (ECG) on a busy night: tables by the windows were filled with customers chatting away, while a giant rainbow flag greeted passersby.

“It’s just our natural state of being,” says Elm City Games owner Matt Fantastic, whose larger-than-life last name evolved from a joke gone too far. “We’re queer-owned and most of our staff is some varying flavor.”

Originally founded in 2016 as a corner inside the now-shuttered Happiness Lab café, the business has grown along with its community to take on three storefronts, which now house some of the three thousand items in inventory that line the store’s floor-to-ceiling shelves. The brightly painted rooms flanking the store’s interior are the game café areas where, for ten or twenty bucks, customers are free to play on one of the shop’s game nights.

With their Hell Fire’s Club baseball hat and long unruly hair, Fantastic initially struck me as Eddie Munson from Stranger Things come to life. Like Eddie, Fantastic grew up playing Dungeons and Dragons, and evoking Eddie’s famous guitar solo of Metallica’s “Master of Puppets,” Fantastic had a brief career in the nineties Brooklyn musicscape, where they played in “loud angry bands.”

Though Fantastic nonchalantly answers that the store is queer-owned, the abundant progressive imagery that pervades the store—the massive rainbow sidewalks just outside, the little queer identity flag stickers for sale—is very intentional. As Fantastic affectionately characterizes it, the store’s strategy is to be “aggressively progressive.”

“It’s important to put it really out there that ‘hey, you can come here and

be whoever you are,’” Fantastic explains. “No one’s going to say something, you know, negative or hurtful or even just thoughtless.”

Fantastic tells me that over the past seven years, ECG has been a place where LGBTQIA+ patrons have felt safe enough to come out. Some use ECG to figure out a different way of presenting themselves than they would at work or home or school. For a lot of players, ECG acts as a safe space to negotiate queerness.

Elm City Games hosts its online community on Discord, where players mingle, talk smack, and organize game nights. This is where I struck up a conversation with Brenda W., who requested not to be identified by name as to not be outed to her parents. She replied to my post, commenting that her first experience using her preferred name as an openly trans woman was at ECG: “I never once have had reason to regret that decision.”

Brenda had mostly been interacting with the ECG community through the Discord server, when she started questioning her gender. She had yet to settle on a name, a hesitation she explained was “mostly due to internalized anxiety on my part, making me doubt whether or not the name I chose was right, whether it would feel good hearing other people use it, as well as worrying about what would happen if word got back to my parents.”

he asked for her name. Her mind went blank; the little script she’d rehearsed in her head went out the window.

“I just stood there awkwardly for a moment and explained that I was trans and in between names at the moment,” she explained to me over Discord message. “He was totally cool with it, so I took my shot with my favorite of the choices I’d been kicking around.” She told him she was trying the name Brenda. Hearing the other player sound her name out back to her abated her initial anxieties. “From that moment on, I’ve been Brenda and I couldn’t be happier.”

When I asked what made Brenda feel that ECG was safe enough to come out, she pointed to the store’s owners, Matt Fantastic and Trish Loter, who both had multiple pronouns listed under their Discord usernames, and who, in her eyes, “generally cultivated a left-leaning political culture and attitude, both in-store and in the server.” Other stores Brenda had visited didn’t feel quite as welcoming; one store in Wallingford was particularly rude to new customers and tolerated homophobic remarks made by other clientele.

“Games traditionally have a reputation for being this domain of, you know, shitty men,” Fantastic explained to me, “There’s just this kind of casual shittiness.” ECG aims to upend that. Fantastic describes the archetypal board gamer as the “um, actually” player who’s a real stickler for the rules. Ben Walter, a staff member at Yale’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion by day and a Magic: the Gathering (Magic) regular by night, recalls the experience of playing at a Magic convention, describing it as “a rules, lawyerly environment.” A lot of the fun in Magic, for Walter, lies in the tabletop conversation during which alliances and rivalries are formed. ECG game nights are typically more conversational and allow players to backtrack, whereas official Magic games are played strictly by the book. If you blurt out any inaccuracies, Walter explains, the “um, actually” gamers are quick to cut you off and recite the rulebook. He pauses, searching for the right words to name this impulse. “It becomes this very mansplainy, masculine desire to prove yourself by being right So it’s not fun, honestly.”

She happened to be in for a game of Armada with another player from the ECG Discord, who only knew her by her username. They were making comfortable small talk before the match, until

For DnD game night—the store’s most popular game—Dungeon Masters (DMs) are briefed on ECG’s standards. An institution in its own right, DnD is a collaborative game in which players

roleplay as adventurers of their own creation, banding together to take on a journey spun by the DM. Fantastic explains that during gameplay at ECG, general swearing is okay but casual homophobia, misogyny, or any hate speech is “like super not cool.” Fantastic continues, “Really it’s about having fun . . . We want people that are excited to share their love of DnD with new people.” They emphasize that “welcoming players of all backgrounds is a big priority to the organizers.”

In this spirit, ECG organizes the Elm City Adventure Squad, a beginner friendly, in-house program for DnD. Though Luke Mastalli-Kelly, software engineer by day and DM by night, is no stranger to running campaigns, he admits that there’s a lot more consideration that goes into programming a session for ECG than for the typical DnD campaign. “It needs to be inclusive in a wide variety of ways,” Mastalli-Kelly writes over Discord message. “I’ve [run DnD] games for everyone—from a kid who hadn’t played much DnD and mostly wanted to fish, to folks who have been playing since the very first editions of the game and are focused adventurers.” It strikes me how thoughtful Mastalli-Kelly has to be to include everyone in the game. For the fishing-obsessed kid, he had to find a way to have fishing advance the plot: “I think he eventually caught a fish that was grabbed by one of the Sahuagin [or a half-man, half-sea creature monster] stalking the boat. Gave him a unique reason to care about the threat!”

I couldn’t help but think back to the groups of friends I had seen through a window that very first time I happened by in one of the game rooms. MastalliKelly and his fiancée had gotten involved with game nights almost as soon as they moved to New Haven in January 2020. He also hosts a separate DnD game night, spun out of friends he made from previous Elm City Adventure Squad games: “That’s how I actually met folks who turned out to be neighbors in my little apartment complex before I moved into a house.”

At this point, I was itching to join a game night at ECG. As luck would have it, a spot had opened up with the Elm City Adventure Squad. For my very first foray, I revived a character I had imagined from my 13-year-old fanfiction days: Kat—a hot, emo, dark magic-wielding, half-demon type of few words (officially, I was a Tiefling Warlock). Kat was

joined by Mockwind, a grouchy, money-chasing warlock; Garuda, an aloof, novel-writing Owlin Sorlock (a halfowl humanoid of a mixed class combining sorcerers and warlocks); Damion, a brooding hero-type fighter; Ranger, a bumbling Barbarian Dwarf with the catchphrase “It’s Dwarfing Time!”; and Dax, a pint-sized Fairy Ranger who doubles as a sheriff with an on-and-off Southern drawl. Snee, our ventriloquist Dungeon Master, led us through a storyline of his own creation—we six adventurers had been hired to take out a kobold infestation that was terrorizing a town.

attacks until it became my turn. For the first spell I would ever cast, I was ready to bring out the big guns. Under my breath, I announced my plan: “I wanna nuke ‘em.” Everyone pooled together dice for me to roll. It added up to twenty-two, more than enough to end the Kobold King in one blow. Snee grinned at me: “How do you wanna do this?” I described what came to mind: clutching the wand with both arms, I (as Kat) fired a giant orb of magic straight into the Kobold King, completely eviscerating him from the face of the earth upon contact. Complete K.O. The table reacted gleefully, perhaps with a tinge of pride, at the newcomer who dealt the finishing blow on the tough boss. Afterward, I got to keep the wand in Kat’s inventory, a token of triumph.

In the seven years since opening, the ECG community has been a revolving door. Fantastic explains: “We have some people that think they’re coming here temporarily and ended up staying a long time and other people who are here from the start of the first semester and then, two days after graduation, they’re gone. We see people that come to visit again, [although] they may have moved away three years ago.”

We marched through with Damion and Dax at the helm, who had a good cop, bad cop schtick going. The others spewed out catchphrases in character (sound effects included) as I lucked out by roleplaying with sparse words. Over the course of the four-hour session, the guys chipped away at my introversion. Roman, a retiree who commandeered Ranger the Dwarf, won me over with packs of M&Ms. As we looted the corpse of a champion we’d defeated, Terry interrupted, “We should let the newbies have first pick.” Michael had picked up a powerful magic item—the Wand of Fish Magic. In a gruff voice, Michael presented the wand to me: “To congratulate the youngin’ on her first adventure.” Andrew, who had been explaining the game to me, smiled kindly: “It does a lot of damage for a level one character.”

The Wand of Fish Magic proved to be quite pivotal. The final boss, a Kobold King backed by a wizard, had effortlessly thwarted my fellow adventurers’

Though Brenda lives a town over and can’t drive, she makes it a point to visit the store whenever she can. “I’ve tried to duck back in because finding a truly safe and accepting place in the gaming community—or in life in general—is hard as hell for me sometimes.” For her, and for quite a few other regulars who commute from out of town, the inclusivity at ECG is worth it.

Come May, I’ll be moving out of New Haven. I might not see the guys I played my very first game of DnD with again (Michael, Andrew, Terry, Roman, Patrick, and Snee), but we’ve formed a Discord thread named Kobold Cave. I like the idea that I’m still tethered to them in some way, and that the Kobold Cave we surmounted lingers somewhere out there, no matter what.

As we wrap up our conversation on a quiet Sunday afternoon, Fantastic has to leave and greet their guests—friends from a now-defunct gaming convention, coming to catch up over a round of games. “We’re a social club built around games,” Fantastic grins as we walk out, “[but we’re] community first.” ∎

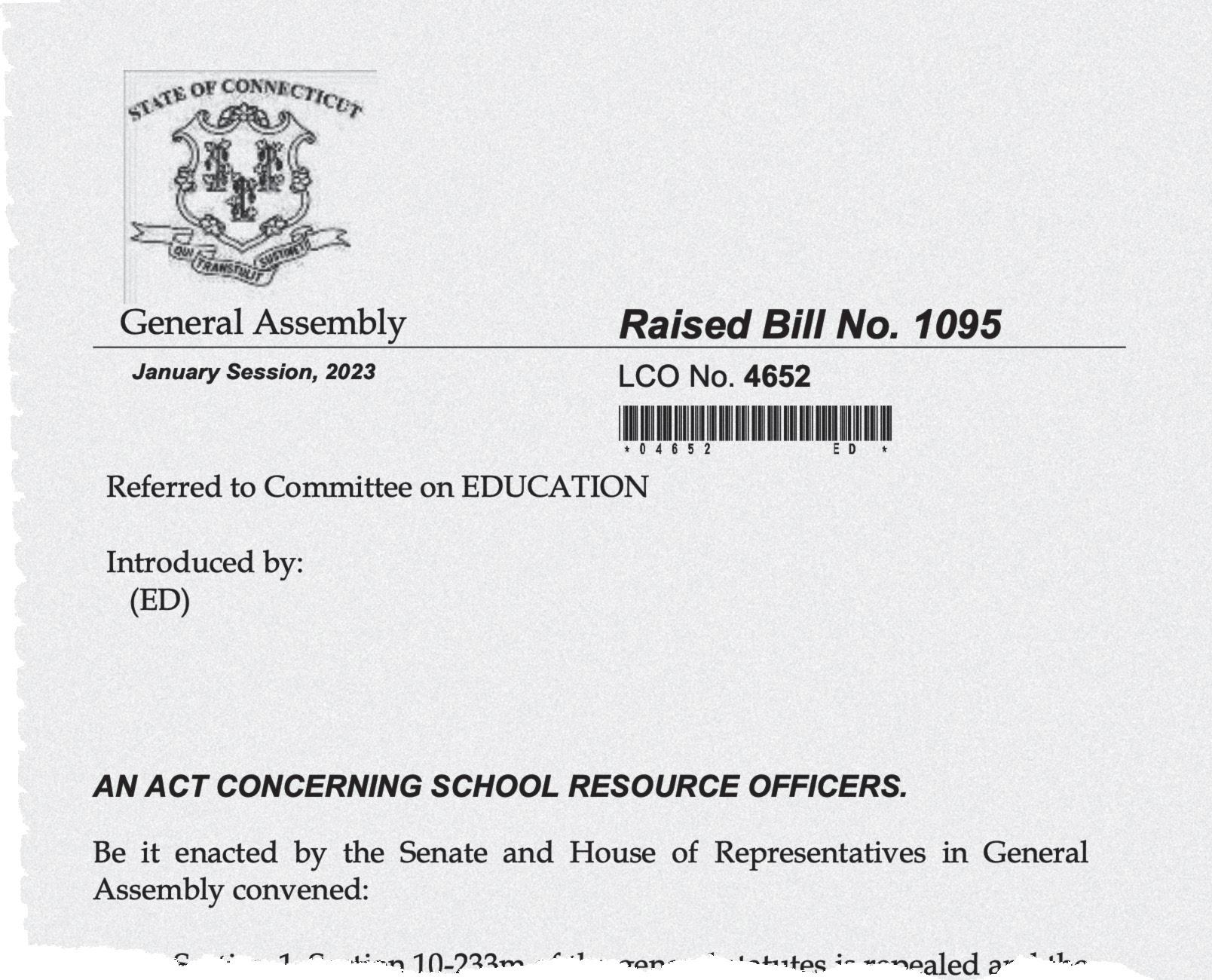

As national conversations about policing in schools intensify, some New Haven Public School students question whether school resource officers actually make them safer.

By Elisa CruzLess than a mile from Yale’s central campus stands my alma mater Hill Regional Career High School. There, it was normal to have a security guard blow a whistle in my face and bark at me and my friends to go to class because our lunch conversation lingered for a minute after the bell rang. School resource officers (SROs) patrolled the hallways, lunchrooms, and even bathrooms. Amidst this surveillance, I was confronted every day by the school’s lack of resources. Teachers often bought class materials out of pocket. The building lacked proper air conditioning. Hardly any school psychologists existed to match the needs of students. It was hard to accept that within this tight budget, money was used to fund more policing rather than more material support.

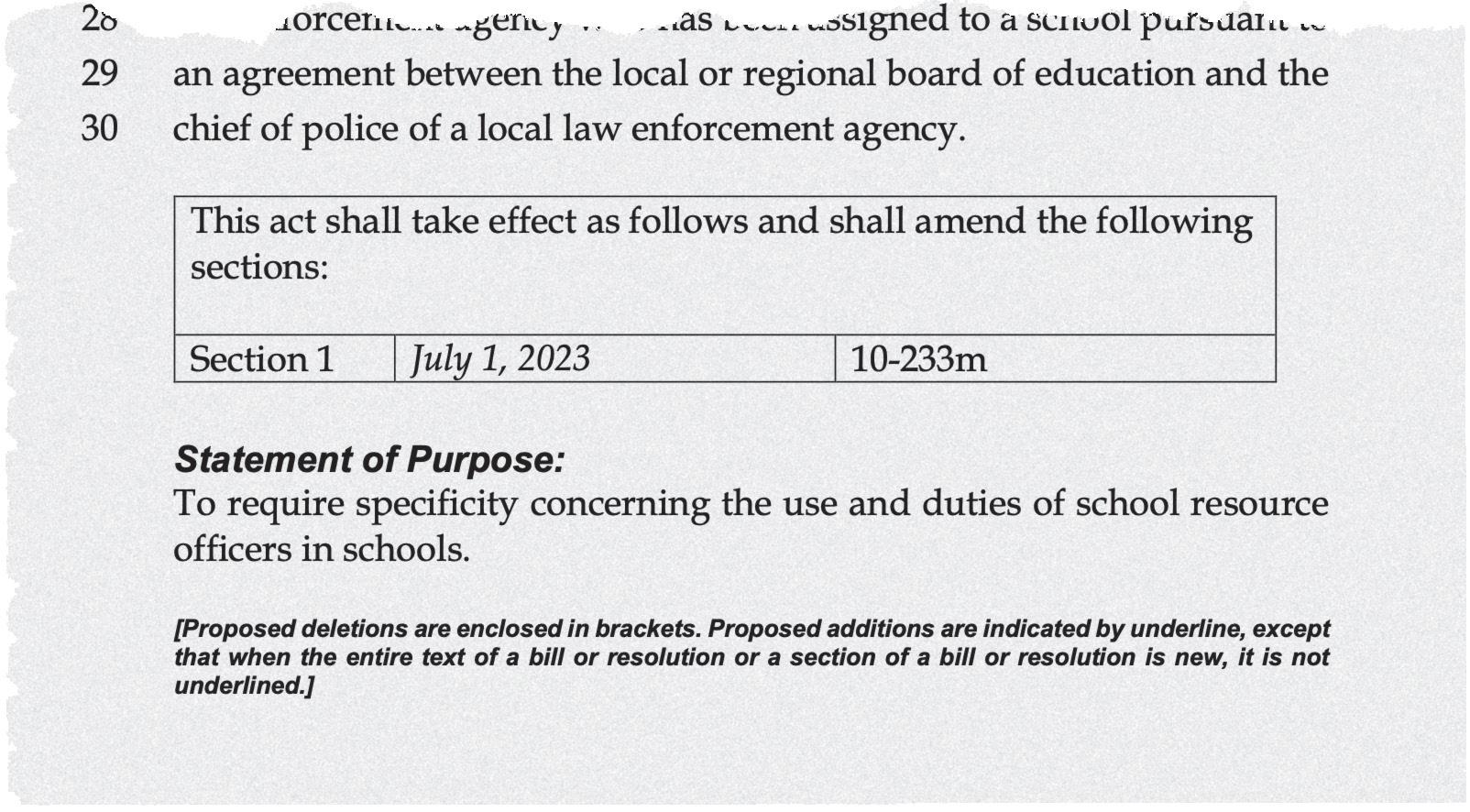

Starting in 1994, New Haven Public Schools (NHPS) established the SRO program—the integration of a police officer into school—to increase both security and support within school districts. SROs differ from security guards in that they are armed police officers. While security guards are not sworn police officers, they still participate in the surveillance of schools. There’s a lack of available public data on SROs, including an explanation for what prompted NHPS to implement SROs in the first place. Now, the SRO program spans seventy school districts across Connecticut.

From my first day as an NHPS student, I was readily aware of our SROs and security guards. Our SRO was usually stationed downstairs, monitoring students as we walked through the metal detector. We

also saw SROs outside in our hallways and bathrooms. I wondered if everyday tasks like finding a bathroom or walking to class needed to be policed. Whether we liked it or not, NHPS students were constantly confronted with surveillance. Yet it wasn’t until I was a junior that I was introduced to our psychologist and social workers. In some sense, it was clear who the New Haven Board of Education (NHBOE) wanted us to know.

“You can’t be in your neighborhood without the police being there and can’t be at school either,” Jamila Washington, a 20-year-old community organizer for Citywide, told me. “So, where’s your safe place?”

While SROs never approached me in a standoffish manner, I likely benefited from being labeled as “good”—I was heavily involved with extracurriculars and close with staff, meaning I was not labeled an “at-risk” kid. I am a Southeast Asian woman, a demographic that doesn’t bear the main brunt of racialized police brutality. However, I still stood in solidarity with

students who felt uncomfortable around SROs and what the SROs represented: a system that allows officers to be brutal. This mainly stems from the sheer power they have over us—students, but most importantly, kids.

Last year, I witnessed our SRO —a fully armed police officer—slam a teenage girl against a brick wall, handcuff her, and lead her into a police car after a school fight. My school’s SRO was twice the age and size of the girl. I cringed watching him seamlessly slam her against the wall. More concerning, we never received an explanation for the severity of the SRO’s actions. I found this lack of transparency strange. How were we to rely on SROs for safety when their actions seemed so arbitrary? Aside from the violence, the sight of an SRO’s navy blue uniform and police badge will always create discomfort for students who have witnessed police brutality—either in their own lives or through the media. SROs will always be a symbol of fear even if they are not always putting their hands on teenagers.

In my school and beyond it, students began organizing against SROs. Citywide Youth Coalition is a group of NHPS students demanding disinvestment in SROs and reinvestment in mental health support. Citywide hosted a district-wide walkout last May, where I joined a crowd of seven hundred students from thirteen high schools across New Haven. Chants of “Care not cops!” rang through the streets, and the protest pressured the NHBOE to actualize their plan promised back in April 2021: to implement more

social workers, counselors, and support personnel. We envisioned a better future for our schools through investing in restorative and transformative justice. We insisted that New Haven end its memorandum of understanding (MOU)—a written, legal agreement between NHPS and the New Haven Police Department (NHPD).We demanded a reallocation of six million dollars from this police budget to anti-bias and anti-racist social workers in NHPS, phasing out the SRO program.

After seeing how unwilling NHBOE was to meet with Citywide executives and students, Citywide worked with statewide coalitions to introduce Senate Bill 1095 into Connecticut’s legislature in February 2023. With this bill, Citywide and other state coalitions hope to increase the transparency of the SROs by having the MOUs and the job performance of SROs visible to each school. In light of nearly a year after this walkout and the implementation of this bill in July 2023, I sought to hear how students and other community members felt about the future of SROs in NHPS.

“You can’t be in your neighborhood without the police being there and can’t be at school either,” Jamila Washington, a 20-year-old community organizer for Citywide, told me. “So, where’s your safe place?”

Seven years ago, Washington started organizing with Citywide after being invited by a friend to join Citywide’s “Dinner and Dialogue,” a program where New Haven residents have round table discussions about social issues over a meal. She told me she joined Citywide as a “socially anxious” NHPS student, but as we talked and joked, I could see the joyful and confident 20-yearold community organizer she’d grown to be.

Washington doesn’t support SROs in schools due to her lived experiences in NHPS, but her distrust in the system builds upon a growing body of information. Research by Connecticut Voices for Children demonstrates that SROs do not make schools measurably safer or improve academic outcomes, but their presence does greatly increase the number

of students arrested each school year— feeding the school-to-prison pipeline. In the 2018 to 2019 school year, Black and Latine students were three times and one point six times more likely, respectively, to be arrested than their white counterparts. The average percentage of Black students arrested in schools with SROs present was over seventeen percent higher than those without SROs. In this sense, SROs seem to be more adept in criminalizing students— the main demographic of NHPS—than creating a safer school.

Even then, the NHPD is no stranger to such brutality, employing officers like those who left Randy Cox paralyzed in June 2022 and tackled Shawn Marshall, a bipolar man, during a manic episode in January

Washington works alongside Alyssa Marie Cajigas, a director of the Citywide Youth Coalition. Cajigas is an NHPS alumna who has since dedicated her time to community organizing with Citywide. As she chats with me enthusiastically about the work Citywide continues to do, her love for the NHPS community is evident.

“We believe that violence should never be the answer,” Cajigas told me, “and police should never be the first resort for discipline in schools.” She explained how police were called to address nonviolent situations such as a class interruption, which could easily be mended with proper social support.

A dual enrollment student at Hillhouse High School and Yale, Elsa Holahan, echoed Cajigas’s worries about policing. Perhaps she owes her conviction to her mother, who is a social worker, or to her own belief in schools where students “feel heard and create their most authentic self.” Regardless, Holahan chose to walk out to the Citywide’s protest last May.

“There are power dynamics and it disrupts trust,” Holahan said about SROs before referring to the broader police system. “Students have had negative experiences and trauma.”

2021. This danger extends to SROs, employees in the same system. Upon a simple Google search, I found an Instagram promotional video from my SRO urging people to become good leaders for the New Haven youth. But the link before it was an article about a New Haven police officer who assaulted a man at a Fairfield bar. A mixture of shock and discomfort contorted my face as I confirmed that the police officer charged with this violent encounter was the same one who roamed our hallways. I found it almost dystopian to see this duality play out side-by-side online. There have been too many instances in which police officers have been unnecessarily aggressive for me to find it possible to connect with them.

Holahan’s words remind me of Washington’s story about a teacher at her school would threaten to call SROs against the typecasted “bad” students—including those who skipped class often—to get them to “behave.” Holahan is adamant about the removal of SROs from Hillhouse. After seeing the police cars parked outside and knowing there are students who have had negative experiences with the gun-wielding SRO, Holahan finds it impossible to ever develop any relationship with SROs. After all, there is no police officer roaming the hallways of the Humanities Quadrangle at Yale— another place where Holahan attends class. I couldn’t help but chuckle at her joke that SROs are “glorified hall monitors.” I asked her if it would be possible to connect with SROs on an emotional level. Without hesitating a second, Holahan confidently answered “No,” before we both giggled at her eagerness.

But Cajigas emphasized that establishing a connection with SROs—whether a friendly relationship or one for mental support—can feel like the only option for some students when the officers are the

most accessible and visible choice. “There is [almost] no other resources for students in the schools ...to look for support and peer mentorship,” Cajigas told me. “Of course, they’re gonna rely on the only system available.”

Cajigas noted that despite these positive relationships formed out of necessity, SROs are part of an oppressive system that is tied to even the well-intended people: “The truth is that Black and Brown folks are oppressed because of a system, not because of individuals. These individuals just so happen to be a part of a horrible system.”

Within this complicated web of systemic fault but individual kindness, SRO s do embody useful support systems for some members of NHPS. But these views often come with acknowledgments of the tension between individual trust and trust of the larger institution of the police force.

“I think he’s a nice person,” Ayush Patel, a senior at Hill Regional Career High School, says about his SRO. “We were setting up for a robotics event, and he was able to find a table for us.”

I saw a piece of myself in Patel. We both went to a predominantly white primary school and, as a result, we didn’t experience the surveillance of SROs until high school. His face tenses up as he scratches the back of his neck. He hesitantly admits that “[SRO presence] feels somewhat

protective, but the fear of just weapons in general in school—even if it’s not within students—it’s just frightening.”

Patel’s experience highlights a contradiction. He knows that his SRO is not inherently evil. At the same time, he feels troubled knowing the SRO wields a gun and taser—weapons that disproportionately harm people who look like him and his peers.

Some students sympathize with New Haven’s vision of SRO s and believe that they are effective protectors. Alex Aguirre, a junior at Hill Regional Career High School, recalls when a student got jumped by a group of other students during school dismissal. He believes that his SRO acted as a sign of “authority that can actually stop them [fighters],” and pulled students away, ultimately intervening midway through the fight. Aguirre views sro s as the second line of intervention—only there if something “crazy” such as physical altercations happens, while social workers can deal with the “small” issues such as arguments.

A school psychologist I spoke with, who requested to remain anonymous due to concern over the security of their job, explained that they view social workers, school psychologists, and SROs all as a team of trusted adults. This team, in theory, acts as social support for students and reaches out based on whatever the student’s individual needs. A safe school climate, according to the psychologist, comes from building relationships between teachers and the mental health support team. The

psychologist expressed a fervent hope for increased mental health support as a way to provide more time and care for students’ specific needs. More importantly, they underscored that the students’ opinions in this conversation about SROs and mental health support will ultimately be the most vital, as they are the biggest stakeholders in this conversation.

Like the school psychologist, Patel and Aguirre both seemed to agree that SROs represent a degree of safety within NHPS. In a perverse cycle, however, this safety is temporary. We often observed a fight, saw the SRO and security guards help break it up, and then waited for the next one. Watching this, many students came to associate SROs with safety since they were a reactionary measure to immediately resolve a situation. But even if SROs do break up school fights, the underlying roots of this violence are not resolved. Often the fight continues off school grounds—including near our school bodega, where I’ve seen student videos circulating.

Despite differing views on SROs, both Patel and Aguirre supported Citywide’s protest, with Aguirre attending in solidarity with his friends who demanded better mental health support. Across their varying stances on SROs, the students I spoke with all just wanted to feel safe at schools and have an investment in more mental health services.

Dr. Wendy Decter, a teacher who recently left NHPS after seventeen years, echoed these fundamental concerns. Decter explained how an ideal world

would have more mental health resources to keep kids on track. She emphasized the importance of having as many people in school buildings to make student life easier. She hopes that SROs can be a reassuring presence for people as they are another route of adult support for students. She noted that some SROs become ingrained into the community, becoming familiar with students and their families.

“I think the SRO was a wonderful resource, they knew [students] from a totally different perspective than the teachers and the school administration,” Decter said, alluding to the idea that SROs come from students’ own communities. “There should have been hiring of as many social workers, school counselors, school psychologists as possible, and making them as available to the students in school as easily as they could be made.”

Within the status quo, some still believe the police to be the most effective form of safety. This is despite the fact that, as Cajigas pointed out, SROs have not been able to deter school shootings, even as far back as Columbine. In a hundred ninetyseven instances of gun violence at U.S. schools since 1999, SROs intervened successfully in only three instances.

When I imagine a safer and more just school, I envision a police-free space. Imagining NHPS without SROs can be difficult because surveilled schools are all that the majority of my peers have experienced—we have gotten desensitized. While I have the privilege to draw upon my knowledge of an SRO-free school before high school, this position does not fix the widespread lack of students’ understanding about how the disinvestment in SROs will improve school health and culture.

At my middle school, much like NHPS, we would attend class, socialize with friends, and work in the library. But we did all these things without a police car parked alongside the school, police officers roaming the halls, and entering through a metal detector. These two experiences still coexist with one another. I have friends who have never experienced police in their schools, while others view it as unquestionably the norm. This tension raises further questions as to why SROs are still viewed as trusted and necessary figures by some groups in the NHPS community.

“What the hell does better New Haven Public Schools mean? For me, and for a lot

of my peers, it means having schools that nourish our souls in a way that actually matters,” Dave Cruz Bustamante, a youth community organizer and current NHPS student told me.

This pattern of SROs’ surveillance hasn’t shifted much since my or Washington’s years at high school. Although more SROs are allocated in larger schools, the students I talked with revealed that it didn’t matter their student population: each school had only one to three social workers—the same way I left the school.

With the staff’s limited numbers and emotional bandwidth, it seems inevitable that NHPS students would experience mental exhaustion. Despite the seven hundred student turnout at the Citywide protest, Cruz Bustamante, who now serves as an NHBOE student representative, told me the NHBOE “is taking very small steps like revising the MOU with the police department ...almost not noticeable at all.” They even admitted that by the end of their term, nothing entirely revolutionary would likely be changed about SROs due to the bureaucratic inactivity in the NHBOE

Instead of relying on reactionary figures like SROs, NHPS should instead look to preventive measures including hiring more healthcare professionals. Mental health professionals can intercept an issue before it manifests into something more harmful. This is especially vital as those with incomes below the federal poverty threshold and individuals, the main demographics of NHPS, are disproportionately

represented in the American carceral and legal system. Cajigas and Citywide have set out to transform this inequity, especially within the context of legislative work.

Washington and Cajigas both told me that their campaign against SROs is “only phase one”—they plan to rethink community security as a whole. Cajigas explained that Citywide is reflecting on other forms of monitoring, including if older community members were employed as monitors in the place of SROs and security guards. In practice, this intervention could look like a community member with no affiliation to the police entering the school, rather than pulling in outsider cops from neighboring towns. Cajigas emphasized the need for NHPS students to be served and protected by members of the same community, disaffiliated from a system that notoriously harms BIPOC.

As an NHPS alum, I’ve now become disconnected from the experience of SROs I had a year ago. I no longer have a fully armed police officer watching every move my peers and I make out of fear we will break into a fight. Security guards no longer view my lunch container as a “weapon” since it’s glass. Yale is only a fifteen-minute walk from my old high school, yet my status as an Ivy League student has exempted me from being as surveilled by the police as I was in high school. At Yale, even when police roam around Cross Campus, they aren’t hounding students who are skipping lectures. The rationale behind this massive shift in surveillance has weighed on me.

Functioning for a year both at Yale and since the walkout prompted me to question whether we need SROs for a safe school environment. And though I went to an SRO-free school for most of my academic life, my four years in a surveilled school still linger within me. At my predominantly high school, we would rarely have toilet paper and grew accustomed to seeing police cars when we walked in through a metal detector. Now, I inhabit the world of a predominantly white Ivy League where students know truffle season in Milan and the most consistent police presence is guarding the exit to our libraries.

Though I am what feels like a world away, I still carry the same habits I did in high school, unzipping all six zippers of my backpack for a security check in libraries and speeding up when I walk by police cars. I doubt I’ll lose them any time soon. ∎

Imagining NHPS without SROs can be difficult because surveilled schools are all that the majority of my peers have experienced—we have gotten desensitized.Elisa Cruz is a first-year in Berkeley College.

Peer-led policing alternative COMPASS has seen a successful rollout in the past five months. But can an organization bankrolled by the City and run by Yale achieve radical aims?

By Amelia Davidson

On the top floor of a converted Victorian home, in the heart of New Haven’s Dwight neighborhood, lives the city’s attempt at an alternative model to policing.

The old home is peaceful when I visit, its rooms awash in sunlight. Tenants putter from one floor to the next, their footsteps creaking against warm hardwood floors. This is a crisis respite house run by the nonprofit Continuum of Care, which provides refuge and short-term beds for people in crisis. “Some, but not enough,” says John Labieniec, one of multiple co-vice presidents at the organization.

Labieniec’s mild manner and casual dress— sweatshirt, long hair tied back—fit right in as he guides me upstairs to what could be mistaken for an attic bedroom. In this room, a new organization has moved in: Elm City COMPASS, short for “Compassionate Allies Serving Our Streets.” The initiative has been years in the making, envisioned as a clinician- and peer-led alternative to traditional policing in mental health and substance use crises. COMPASS has worked with three hundred and four people since its November 2022 launch (as of March 1), through a mix of responding to 911 calls and conducting proactive outreach.

Although COMPASS’s office has a distinctly cozy and communal feel, New Haven’s biggest institutional forces are at work in this Dwight home. Yale University manages COMPASS in a partnership with the New Haven city government, having secured $3.5 million of city and federal funding to administer the program. Yet, Yale’s name has been largely omitted from the COMPASS rollout.

COMPASS is one of the few initiatives across the country that is tangibly moving toward peerbased alternatives to policing. Yet its collaboration with New Haven police and its integration with some of New Haven’s most entrenched institutions—the city government and Yale University— alienates some long-time harm reduction advocates. COMPASS’s launch then begs the question: can an organization meant to disrupt the policing system still do so in collaboration with mainstream institutional mammoths?

COMPASS emerged from a time of “multiple pandemics,” Jack Tebes, COMPASS director and Yale Professor of Psychiatry, told me, “one hundreds of years old and one more recent.”

Tebes’ two pandemics—one being centuries of racism and police brutality, and the other being COVID-19—intertwined in the summer of 2020, as masked protestors marched in the streets and called for police abolition in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. In response, the city of New Haven appropriated funds for a civilian crisis

response team that would follow a new model of law enforcement and community care, soliciting applications from organizations up for the task. Tebes and his colleagues at Yale’s Consultation Center had long worked on crisis response matters and were selected to spearhead the new initiative.

In the years of planning ahead of COMPASS’s launch, the initiative strove to involve New Haven residents as much as possible. Representatives from the city and Yale conducted focus groups and community forums, ultimately consulting more than two hundred and fifty community members, according to its website. Yale also subcontracted with Continuum of Care, long established in the world of New Haven crisis response, to provide what Labieniec calls “boots on the ground” for the COMPASS operation. With this collaboration, Labieniec became the coordinator of COMPASS’s crisis response team.

COMPASS was slated to begin in mid-2021, but the launch was delayed over four times as the city struggled to find a subcontractor and finalize its contract with Yale. The city also contended with police and fire unions who wanted to bargain over COMPASS’s plan of operation and the role that police and fire officials would play in its implementation. In August 2022, the police union filed a state labor board complaint saying that the city was going forward with the COMPASS launch without providing the launch plans to police. Ultimately the bargaining was resolved, but it did delay COMPASS’s launch yet again through the later half of 2022.

When the crisis response operation did launch, it did so in the form of a “secondary response” team, one that would only go out on a call if requested by police and fire operations. This ongoing collaboration with police, although temporary, is leaving its mark.

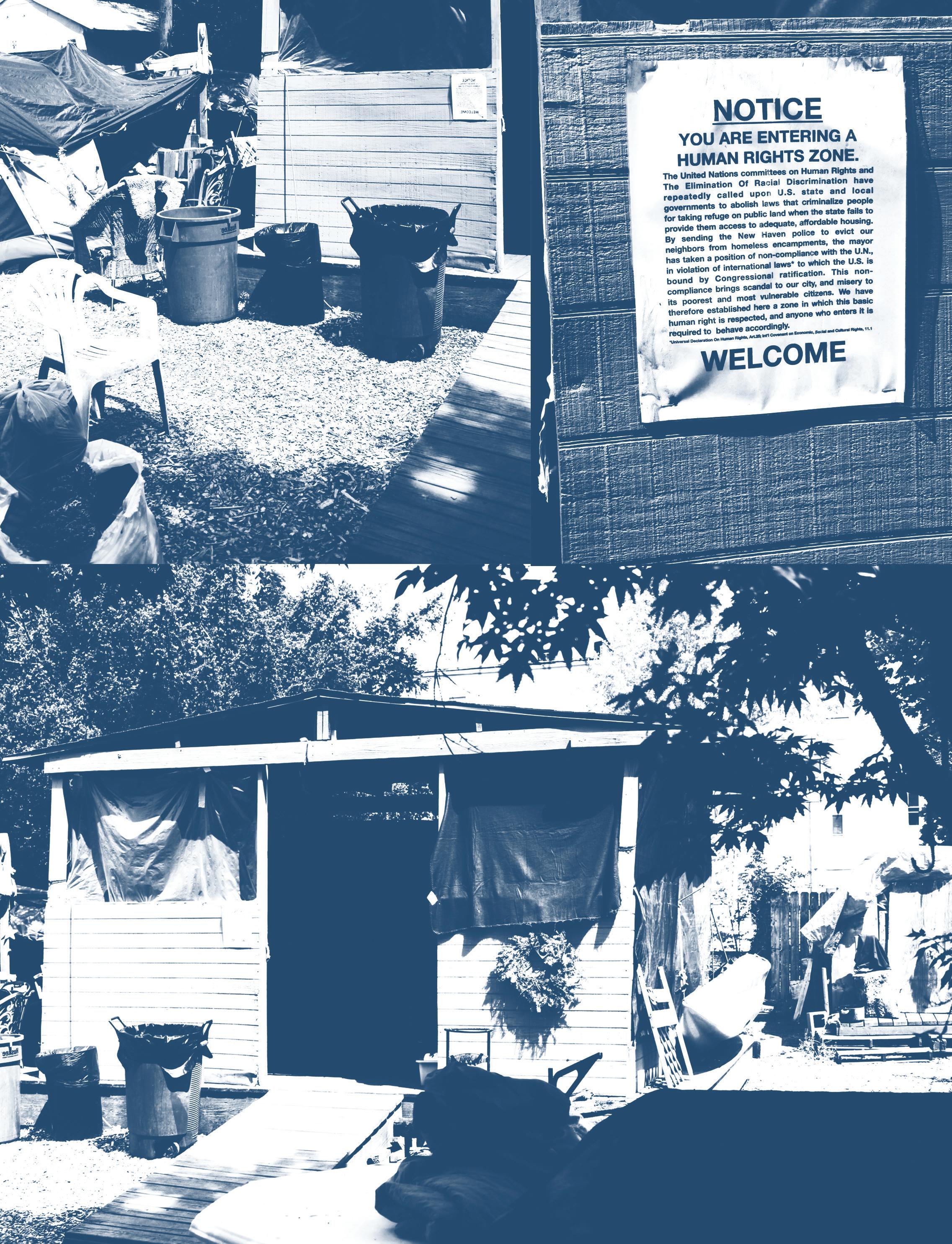

In March, when city officials and police arrived at the West River, off Ella T. Grasso Boulevard, to clear the three-year-old Tent City encampment, COMPASS’s signature green jackets were present alongside them. As bulldozers rolled over the tents that had once housed sixteen people, the COMPASS team members worked to find beds for those who were getting evicted. One Tent City resident, Barry Lawson, told The New Haven Register : “I was going to get arrested, but then I got offered a place [to stay] on Edgewood” by the COMPASS team.

Despite the care COMPASS provided, in moments like the Tent City clearing, said housing advocate Mark Colville, “the roles get a little weird.” Colville’s organization, Amistad Catholic Worker, is based nearby in The Hill neighborhood and helped organize and sustain Tent City for years. He believes that COMPASS’s alignment with the city during the mass eviction—even while they were just administering care to the evicted— exemplifies the danger of a harm reduction

“As bulldozers rolled over the tents that had once housed sixteen people, the COMPASS team members worked to find beds for those who were getting evicted.”

organization that works alongside police and city government.

“What I saw [during the Tent City clearing] was people from COMPASS accompanied by police in uniform and with guns. So to me, that sort of invalidates the whole thing,” Colville explained to me over the phone.

Colville’s model of community care is different from COMPASS’s, as he lives in a home directly alongside those he works with, including the former residents of Tent City. This generates a horizontal model of care in which neighbors help neighbors—without necessitating the involvement of police.

People who are unhoused from all over the state come to The Hill, Colville says, because “we take care of our own.”

Amistad Catholic Worker runs a house to which anyone can come eat, pray, and receive donations. Following the Tent City demolition, they also allow unhoused people to camp in the backyard. The organization’s mission statement reads: “We seek to be a safe haven and a public nonviolent witness in our neighborhood, and always try to blur the distinction between the people who are serving and those being served.”

“That’s what we’re doing here, and we simply need the city to get out of the way and let us show them how to do it,” Colville emphasized.

At COMPASS, crisis response occurs only after police referral, generating a major departure from Colville’s model. Yet

there are aspects of COMPASS that do resemble forms of horizontal community care, such as the involvement of peers on their response teams. Two people from COMPASS respond to crisis calls: a licensed clinician and a peer recovery specialist who has experienced homelessness and/or substance use.

Between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m., each two-person COMPASS team can respond to a call in an average of thirteen minutes. When they do, COMPASS peer recovery specialist Nanette Campbell told me over the phone, the clinician will often take the immediate lead on crisis response, while the peer is there to relate to those in crisis and approach them in a more accessible manner than police or clinicians may be able to do.

Campbell is the primary peer on the COMPASS team and has been working in the field of peer crisis response for twenty years. She emphasized the importance of having a peer respond to a crisis, rather than just a clinician or an armed force:

“It’s just different walks of life, and [police] don’t know what we know as far as mental health issues, substance issues,” Campbell told me, exhaustion in her voice at the end of her work day. “Me myself, I’ve lived that life. So just knowing about different things and what people are going through and meeting them where they are.”

COMPASS also does proactive outreach to areas that it deems crisis hotspots: “where there are drug overdoses, folks who look like they’re in need, folks who may be congregating during cold winter weather and may need to get to a warming center,” Tebes explained. During these outreach sessions, the two-person team distributes care packages and can respond if they see someone in distress. These efforts tend to be concentrated on the New Haven Green, along a stretch of Ella T. Grasso Boulevard in the Edgewood and West River neighborhoods, and at the end of the Boulevard south of The Hill. All are majority BIPOC and low-income neighborhoods with the exception of the Green, where demographics are affected by its close proximity to Yale.

COMPASS conducts its outreach without any police presence. Yet Colville feels like the ongoing partnership with police— especially given that it is the only way the group responds to crisis calls—keeps COMPASS from being able to help in areas that do not want a police presence.

“I doubt that anyone on my block, except for me, is really aware that [COMPASS] is a thing,” Colville told me with a sigh. “That’s fine, you know, it’s in its infancy. But in this neighborhood we have a standing policy here, we don’t call the police. So who knows if we will ever see [COMPASS].”

Both Tebes and Labieniec made it clear that this secondary response phase is temporary, and that there are plans for COMPASS to independently respond to crisis calls as soon as this summer. However, COMPASS would still remain a part of the 911 system. Tebes explained that Public Safety Answering Points (PSAP), which runs the 911 dispatch, would direct relevant 911 calls to COMPASS rather than uniformed police. In order to reach that point, however, COMPASS must collect enough data to understand where it would succeed as a solo actor, and with that data, draw up a standard to be used by 911 dispatchers. This data comes with time, and the more COMPASS referrals that come from police and fire officials, the more useful this data can become.

“In New Haven, it was always planned that COMPASS would grow into that [independent role],” Labieniec said. But that process takes time. Labieniec has traveled and met with leaders from Colorado and Iowa’s statewide non-police crisis response systems. And in both cases, “it was a process” to become disentangled from their existing police systems.

“If you’re not in it, you don’t realize how complicated it is,” Labieniec said.

On a later call, I asked him if he was concerned that the current phase of police partnership might alienate communities like Colville’s in The Hill. He responded that it would be impossible to get this project off the ground without collaborating with police. In order to help those in crisis, he believes the project needs to begin—even if it starts with the police.

“I don’t think you can effectively do what everyone is seeking for us to do without collaborating at some extent with everyone. And I think that includes the police,” Labieniec said emphatically. “If we don’t have positive relationships with the police and with the city and with everyone, we’re not going to be as successful for the people that actually need the help.”

Labieniec and Campbell both expressed to me their belief in the ways that COMPASS has helped, and will continue to help, people on the individual level. Campbell described a woman who refers to the team as “her saving angels” after they helped her get clean. Labieniec pointed me to a New Haven Independent story about a woman who COMPASS helped safely relocate off the street.

But COMPASS is not just the two-person response team, nor the house in Dwight. It is also an experiment in policing alternatives that is continuously debated in City Hall and litigated by Yale and city lawyers. And at that macro level, some activists have begun to grow concerned—even those looking past police presence.

Behind COMPASS’s slow, methodical, and data-driven approach to policing alternatives—an approach that frustrates more radical, anti-police advocates like Colville—is Yale and the New Haven government.

Last spring, Yale quietly became a driving force behind the COMPASS project. A publicly available, 36-page contract between Yale and the city shows that, in exchange for over $3.5 million in funding, Yale agreed to set up and run COMPASS for at least three years. More specifically, The Consultation Center at Yale University, which Tebes runs, would subcontract with Continuum of Care to launch the COMPASS team, and would then be able to collect data from the initiative for research purposes. This data includes COMPASS’s clients’ demographics like race, ethnicity, gender identity, and income—all of which Yale collects and shares with New Haven.

The Consultation Center has, for the last forty years, researched best practices for mental health crisis intervention, according to a video on the center’s website. The center partners with external organizations or bases projects off of affiliated faculties’ needs. One of these projects included running a culture and diversity training for the New Haven Police Department.

According to Tebes, Yale has made in-kind contributions, such as new hires and equipment, that will amount to up to

$750,000 over the three-year duration of the contract. Continuum of Care has made additional in-kind contributions that will total around three hundred thousand dollars, Tebes said. As COMPASS’s main representative from Yale, Tebes manages the entire budget.

The partnership between the city and Yale, and the lack of publicity surrounding the matter, raised alarm bells for some. In May 2022, when the contract became public, Nichole Roxas and Alice Shen, two former Yale Psychiatry residents published an op-ed in The New Haven Independent titled “COMPASS Critics To City: Be Transparent.” They wrote that “as two community psychiatrists, our patients tell us they do not trust the police in New Haven and, more than that, they do not trust Yale.”

“How did Yale sneak in on the cut? Did the city solicit community input about who would receive the money and how it would be spent? Would reported concerns be addressed?” the pair asked.

When I asked Tebes similar questions, he pointed to COMPASS’s Community Advisory Board as an important check on Yale’s involvement. The board currently contains nineteen New Haven residents from all walks of life, including one unhoused person. It meets four times a year in addition to separate small-group meetings and comes to decisions via group consensus on policies ranging from maintenance of the COMPASS website to what community resources it should provide. These meetings, according to Tebes, also ensure that Yale does not make any unilateral policy changes.

“We begin with humility, listening to community members, sharing any credit, centering our community, not centering Yale or ourselves,” Tebes added.

Faced with those same questions in the COMPASS office, Labieniec thought for a moment, and then quietly shared that he has not seen COMPASS’s affiliation with Yale as an alienating force when COMPASS helps out in the community. “There’s been nothing but warm, welcoming, positive excitement,” he said. “I personally have not seen anything, and I’m very involved.” Labieniec oversees the team every day, and occasionally accompanies them on calls.

Colville would say otherwise. In his opinion, by taking up a huge amount of city land and then refusing to use their forty-two billion dollar endowment to help the citizens they displace, Yale has become a catalyst of homelessness and poverty in New Haven, making their sponsorship of COMPASS come across as too little, too late.

“It is the university and the city government that are sort of colluding in promoting this myth of scarcity,” Colville said, “as if land and resources are too scarce to take care of the most low-income people among us.”

Unlike Colville, David Agosta, a New Haven

disability rights activist and former member of COMPASS’s Community Advisory Board, takes no issue with Yale’s involvement in COMPASS. “We recognize that Yale has the smartest people in the world,” he said. “When they do something right, they do it right.”

Yet Agosta recently resigned from the board due to frustration with a different partnering institution: the city of New Haven. Although he repeatedly expressed his admiration for everyone involved in COMPASS, Agosta said that he could not remain on the board so long as the city refused to provide adequate beds and services for people without housing. He likened the COMPASS project, with the lack of current city resources for unhoused people, as “building a structure without a foundation.”

“It’s not about COMPASS; it’s that the mayor has not done his part to allow COMPASS to succeed. That’s why I resigned,” Agosta said. “If you talk to the folks there, there was evident frustration at the fact that there was no housing. You can’t really talk about it from the inside, so I had to do it from the outside.”

Colville also expressed concern at the city’s involvement with the project. Despite everything, he sees COMPASS as “a good concept.” However, he is critical of the current framework of New Haven’s government, and that within it, COMPASS will be unable to turn into the radical alternative to policing that it was originally envisioned to be.

“This happens all the time in New Haven,” he told me. “Is this just another liberal idea that usually tends to fizzle out at some point, especially when the cops start pushing back or when we get the next ‘law and order’ mayor?”

The current contract only guarantees COMPASS’s funding through June 2025, at which point New Haven, Yale, and Continuum of Care will have to renegotiate. A mayoral election is approaching, and as time passes from when public calls for policing alternatives had peaked in 2020, it is possible that COMPASS’s funding could dry up.

If it does, Labieniec will not let that mark the end of the initiative. Although Yale and the city of New Haven are large conglomerates, whose whims could change when it’s time to renew the contract in 2025, Continuum of Care is still a grassroots organization, and it is committed to COMPASS for the long run. Labieniec told me that he has already looked into alternative grants that could keep COMPASS up and running, should New Haven or Yale step out of the picture.

“Our agency is invested in this,” he said.

A solely nonprofit version of COMPASS, without the financial backing of the city or the datadriven work of Yale, might look radically different. A non-Yale, non-governmental COMPASS would be missing a significant and consistent source of funding, the guidance of a city-run advisory board, and the data-driven operational approach

“It is the university and the city government that are sort of colluding in promoting this myth of scarcity,”

that Labieniec says could not happen without the help of Yale. But it might not have the same incentives to work closely with police, and could instead call directly on the city to provide more housing services and beds, as Agosta wants. Meanwhile, there would be a greater emphasis on Continuum of Care’s horizontal modes of aid, including the peer response team and the location of their respite centers.. This is the version of COMPASS that resembles a radical nonprofit organization—the version that is on full display in the Dwight attic office.

Still shy of the six-month mark, COMPASS is only beginning its work, as Tebes was quick to point out. COMPASS teams still only respond to crises during the daytime, and they still act only as a secondary response for 911 calls, behind police

and fire officials. Both of these are on a timeline to change by the end of the summer. And with that time passing, Labieniec and Tebes both said, collaborations should continue to grow between COMPASS and the myriad harm reduction and homelessness organizations that exist in New Haven.

“We want to create the structure that this will be able to be going on for years to come,” Tebes said. “It’s very rewarding. It’s difficult, but it’s a good kind of difficult that we all want to do.”

But speaking to me from a communal home in The Hill, rather than a Yale office, Colville’s doubts remain unassuaged.

“Until [Yale and the city government] change their policies, I don’t see how they can be part of the solution,” said Colville. “. in terms of what their role should be, they should get the hell out of the way.” ∎

Yale’s CCE program aims to revolutionize campus sexual its student-led approach raises crucial questions about

At the start of the Spring 2022 semester, K. was sexually assaulted. They can’t recount everything that happened that night, due to the impacts of alcohol and post-traumatic stress disorder, but they remember meeting an older student from a campus club they were in at a fraternity party. They talked. It was suggestive. The two went back to his room. They weren’t in the right state of being to consent—and they didn’t consent.

K. had also just started their new job on campus. As a Communication and Consent Educator (CCE), they’d spend the rest of the semester attending trainings hosted by institutions like Title IX, planning events to educate students about sexual misconduct, and flipping through readings in preparation for weekly CCE meetings—all in the hopes of creating a healthier social and sexual culture at Yale. After they were raped in high school, K. spent years working to build more supportive structures for survivors of sexual assault at their school and local community. The opportunity to continue this with Yale’s CCE program was a large factor in their decision to enroll.

Specifically, K. kept working to make Yale a more comfortable environment for survivors of sexual violence with the CCE Survivor Support team, one of four “project groups” that CCEs serve in alongside their respective residential colleges.

Despite their time learning about and educating others on sexual misconduct as a CCE, they had trouble recognizing their own experience of sexual assault. They’d only begun processing the events of that night several months later on a summer trip to Europe—when they weren’t “CCE-ing,” they told me. Although they’d started to come to terms with their experience that summer, they tried to keep their trauma out of sight and out of mind come fall semester, avoiding thinking or speaking about it.

sexual misconduct response, but

power and accountability.

In retrospect, K. asked: “Why do I not give myself the same care and concern as I would give literally any of my friends especially as someone who is paid to talk about these kinds of things with people?”

The CCE program emerged partly in response to widespread scrutiny of Yale’s sexual climate both on and off campus. The program signaled an accountability shift inwards—toward a peer-topeer system managing sexual misconduct and away from the more bare bones administrative Title IX procedures.

Melanie Boyd, Yale College Dean of Student Affairs, helped launch the program in August 2011, about four months after the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) began investigating Yale for violating Title IX rules. The headline-making Title IX complaint, raised by a group of sixteen Yale students and alumni, alleged that the University fostered a hostile sexual climate and mishandled several cases of misconduct in recent years.

The complaint highlighted several campus events, many of which remain infamous at Yale more than a decade later. In 2008, Zeta Psi pledges held a sign reading “We love Yale sluts!” outside of the Women’s Center. In 2009, male students circulated the “preseason scouting report,” a mass email ranking dozens of female first-years by how many beers it would take to sleep with them. And in October 2010, pledges of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity (DKE) marched around Old Campus chanting “No means yes, yes means anal!” and other misogynistic remarks.

The day after the 2010 DKE incident, Boyd’s Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies (WGSS) seminar “Theorizing Sexual Violence” met at their usual time and place at the Hall of Graduate Studies, which is now the Humanities Quandrangle. But instead of discussing the week’s scheduled curriculum, the Yale Daily News reported, Boyd urged students to reflect on a “script-breaking response” to campus sexual violence and imagine community-oriented ways to respond to such incidents.

Later that year, the University’s Task Force on Sexual Misconduct Education and Prevention, composed of Yale faculty, convened in response to the DKE incident. They released a report recommending that Yale “expand the pool of well-supported, well-educated student educators” and “raise the level of student knowledge through mandatory educational programs,” among other ideas. While the CCE program began to take shape, Yale adopted a flurry of other sexual misconduct response programs, including the University-Wide Committee on Sexual Misconduct (UWC), which investigates and adjudicates sexual misconduct cases.

A proposed CCE program, according to Interim Assistant Dean of Student Affairs and Director of the Office of Gender and Campus Culture (OGCC) Eilaf Elmileik, “grew out of” Boyd’s WGSS seminar in the fall of 2020. Though the News reported that

the seminar discussed the DKE incident and that the program came amid the flurry of Yale’s responsive actions, Elmileik denied connection to the public uproar.

The first class of CCEs trained for their new roles in the summer of 2011. They held their inaugural first-year orientation workshops that fall.

“These are difficult issues and require frank, thoughtful conversations—the kind of discussions students are often most willing to have with other students,” Boyd stated in a News article when the CCE program first kicked off.

Today, the student-led CCE program, which the OGCC oversees, stands unique among other sexual misconduct education and support systems at Yale. More than fifty undergraduates, distributed throughout all fourteen residential colleges and diverse areas of student life, serve as CCEs. In an effort to change the campus’ social and sexual climate as a whole, they hold “interventions,” including informal conversations and more formal workshops, like the mandatory Bystander Intervention training for first-years.

Deputy Title IX Coordinator Katie Shirley wrote to me that the Title IX office provides “guidance” on the primary content of CCE workshops. But it is typically fellow undergraduates that are responsible for educating their peers on how to prevent sexual violence themselves—despite the heavy topics at hand and the complex web of sexual misconduct policies and response systems at Yale. The University’s professionally staffed programs like Title IX and the Sexual Harassment and Assault Response & Education center (SHARE), which provides crisis support, counseling, and health and wellness care referrals for survivors, take a more indirect role in outreach.

Title IX offers its own customizable workshops and training for campus organizations that request them, according to its website. Shirley did not address my inquiry into what Title IX’s own training looks or whether these are mandatory for students on their own. CCE Zoe Kanga ’24, who is on the Title IX Student Advisory Committee, told me that there are opportunities for students to speak directly with the Title IX office about sexual misconduct at Yale, but that these opportunities aren’t well advertised beyond CCEs’ workshops with firstyear students.

“We do, of course, advertise those resources during our interventions. But I think after that it kind of falls out,” Kanga said. “And I doubt that anyone in their junior year after experiencing something is going to go dig through their archives and find that one slip of paper that they received in their CCE training first year.”

In her email to me, Shirley only described opportunities for student leaders employed by Yale—including CCEs, First-Year Counselors, Peer Liaisons, and Transfer Peer Advisors—to speak with her during open office hours. She added that she is available to meet with CCEs one-on-one if they are interested in speaking about a particular area of the

office’s work further. Despite the chances to connect mentioned by Shirley, CCE Aiden Magley ’25 told me that beyond trainings, collaboration between the CCEs and Title IX is sparse.

As their fall semester back to campus continued, K. couldn’t control the visceral reaction they felt when they saw their assailant in spaces they once felt safe in. Right before Thanksgiving break, they began speaking with Shirley, whom they were familiar with through CCE training, to secure a no-contact agreement between themselves and their assailant. They’d learned a little about no-contact measures through CCE training, but the intricacies of the process were still unclear.

Initially, K. believed that visiting the Title IX office would fix all of their problems. As a CCE, they directed people to the office all the time. But as they sat across from Shirley at each meeting, tackling the logistics of academic accommodations and social arrangement conditions in the new no-contact agreement, K. gradually understood they weren’t going to receive the emotional relief they needed. Title IX’s supportive measures—and all of their limits—are laid out to CCEs during training and made accessible on the office’s website. Shirley and most Title IX administrators aren’t trained as therapists. Despite this, K. came into the process expecting more support than logistical accommodations. They’d ultimately walk away emotionally unsatisfied, even though they’d later describe their experience in itself as “neutral.”

When students come to CCEs with disclosures of sexual misconduct, CCEs respond with a script designed by the OGCC. Usually, the CCE begins by informing the survivor that they are an educator, not a counselor. They emphasize that they’re available as support, but they aren’t trained to give advice or to offer solutions themselves. As someone talks through their experience, CCEs make sure to mimic their language as part of the motivational interviewing method, which prioritizes guiding students toward their own conclusions on their experiences.

During each conversation, the CCE presents the array of resources on campus available to students who state they have experienced sexual misconduct. If you’re looking for something like emotional counseling and cognitive behavioral therapy, SHARE may be the way to go. If you need to move rooms to distance yourself from your assailant, or even an ex, Title IX can help arrange accommodations. And if you want to hold your assailant accountable through disciplinary consequences, you can book a consultation with the UWC. But the process may be lengthy.

As mandatory reporters, CCEs inform their OGCC supervisors of all disclosures, which are then reported to Title IX. Shirley then sends the survivor an email with resources and opportunities to follow up with the office, which they may or may not respond to.

As they navigated their own process, being a CCE made K. feel “helped and not helped.” From

“We have a tendency to over-intellectualize our experiences in a way that can be challenging to give enough space for the human, personal elements of those experiences,” K. explained.

“I have all this hefty consentbased vocabulary that I can use in an academic context. But where does that leave space for my rage, and my pain, and my sadness?”

Sexual Harassment and Assault Response & Education Center

Crisis support, counseling, and health and wellness care referrals for survivors

Counselors are available any time at the 24/7 hotline: (203) 432-2000

Part of Yale’s obligation to respond to sex- and gender-based discrimination as required by federal law

Compiles and reports disclosures of sexual misconduct

Can provide accomodations such as a no-contact agreements

University-Wide Committee on Sexual Misconduct

Investigates and adjudicates sexual misconduct cases, with the power to discipline assailants

Process involves a trial with evidence, lawyers, and cross-examination

their own training, they recognized Shirley’s kindness toward survivors of sexual violence. Still, K. felt strange about approaching someone related to their job. They remembered thinking, “Man, this is really fucking weird.”

K. also initially felt awkward telling their bosses about the assault—after all, they were a University employee, and the OGCC coordinators were the ones who signed their paychecks. They ultimately grew comfortable enough to be vulnerable with them after a CCE friend reassured them that the nature of their work is to understand situations like theirs. Their friends in the program supported them through their experience, often offering them a place to talk through their emotions while providing a shoulder to rest on.

“We have a tendency to over-intellectualize our experiences in a way that can be challenging to give enough space for the human, personal elements of those experiences,” K. explained. “I have all this hefty consent-based vocabulary that I can use in an academic context. But where does that leave space for my rage, and my pain, and my sadness?”

When students process their feelings about a sexual situation, CCEs take care not to use words like “rape,” “harrassment,” or “assault” if the person does not do so themselves.

“If someone’s talking about a ‘really weird hook up,’ we just help them work through a ‘really weird hook up,’” Kanga explained to me. “We have the skills and the trainings to just be a validating and listening ear that I think really helps.”

Unlabeled incidents that are concerning to the CCEs—which CCE Maya Fonkeu ’25 called “events of concerns”—wouldn’t be officially reported to the OGCC or Title IX office, even if they’d be considered sexual misconduct based on Yale’s definitions. So, students would never get that email with supportive resources from Title IX, unless they labeled their experiences of misconduct on their own.

Naina Agrawal-Hardin ’25, an Associate Editor of The New Journal, works with the national organization Know Your IX, which aims to end sexual and dating violence in schools through education on survivors’ rights through Title IX. Because the CCE program and SHARE are often successful at providing students individual attention and support, Agrawal-Hardin said, many people may decide against going to Title IX or other administrative bodies for accommodations.

“On the one hand, it’s really excellent that students are able to circumvent these systems that often are traumatizing, are really lengthy, or really exhausting, or don’t always turn out in your favor,” she told me. “On another level Yale has a lot more discretion about what numbers it discloses, and how it represents the scale of the issue on campus.”

Since privacy concerns and confidentiality rules govern Title IX and the UWC, it’s difficult to know how many people who make disclosures to CCEs ultimately end up going to the Title IX office for a follow-up. Most CCEs I spoke to estimated that the

majority of students who come to them do not continue onto Title IX, but stated that they couldn’t be completely sure. Shirley told me in her email that “many students who receive initial outreach from Title IX do follow up,” but declined to share more about numbers. Even if students decline to follow up with Title IX, the office’s official reports still include their disclosures.

Outside sexual misconduct surveys might provide more clarity. In the spring of 2019, Yale participated in the Association of American Universities’ Campus Climate Survey, which estimated that 38.7 percent of the women and 15.4 percent of the men at Yale College experienced some kind of sexual assault. The 2018-2019 student body totaled 5,964, indicating that at least 1,600 students experienced sexual assault. But from fall 2015 to spring 2019, Title IX received only two hundred forty-six disclosures of sexual assault, according to its semiannual reports on sexual misconduct cases.

Because Title IX is two semesters behind on releasing its reports, their most recent statistics on sexual misconduct at Yale date back to 2021. That year, there were a total of one hundred fifty-two disclosures of sexual harrassment, sexual assault, intimate partner violence, stalking, and other recognized forms of misconduct reported to Title IX, the UWC, and the Yale Police Department (YPD). Seventeen of these disclosures involved the YPD, while ten primarily involved the UWC. Of the eight resolved UWC cases, the UWC found sufficient evidence of sexual misconduct in five. The outcome of those five resulted in “respondent-focused responses” including written reprimands, sexual consent awareness training, suspension, and expulsion.

When K. was weighing their options, they reckoned with their general beliefs against the punitive UWC system and the raw pain they experienced following the assault. K. knew ostracizing perpetrators didn’t necessarily call for a “growth mindset.” They believe putting perpetrators through the punitive system, whether it’s the UWC or the carceral system, can reproduce harm in the long run. But these beliefs didn’t change the fact that their assailant had harmed them, too. For a while, they struggled to reconcile their broader ideological beliefs on punishment with their personal feelings toward their assailant.

“I felt like being a CCE seems so much more like the former to me, and being a person felt like the latter,” K. confessed.

Although the CCE program and UWC were both created in 2011 in response to the public reckoning with sexual misconduct at Yale, the UWC representatives only spoke directly to the CCEs this past semester. The experience was “exciting” to CCE Josephine Cureton ’24.

“It definitely was not your typical CCE meeting at all,” she said.

During the usual CCE training at the start of each semester, representatives from SHARE and Title IX directly speak to the CCEs, with explanations of the UWC usually handled by the Title IX

They believe putting perpetrators through the punitive system, whether it’s the UWC or the carceral system, can reproduce harm in the long run. But these beliefs didn’t change the fact that their assailant had harmed them, too. For a while, they struggled to reconcile their broader ideological beliefs on punishment with their personal feelings toward their assailant.

representatives. They also tended to give far less extensive information on the process. When I asked Cureton about what she learned, she whipped out a notebook and flipped through a list of the complicated factors that go into the UWC’s investigation process: types of text and video evidence they accept, the amount needed to reject or move forward with complaints, students’ ability to hire their own lawyers, policies on the cross-examination of witnesses, and more.