Volume Issue the 03 THE LEGACY QUESTION 07 ISRAELI DELEUZIAN FORCES 13 HATE ME TENDER THE HEADLIGHT ISSUE The College Hill Independent * 47 02 September 2023 22

From the Editors

It’s issue two! Two is much more than 1 and another 1. TWO is one of the most powerful ideas. A few nights ago my friend and I were talking about kissing, googled: do animals kiss for love?. I have COVID. Most results point at BONOBOS. Bonobos kiss for comfort and to socialize. Watching videos, Bonobos often laugh while kissing. Sometimes kick each other after. Added: do bonobos kiss with tongue?. They do! Trying to leave our windows open in the house. Promoting Air flow. Bonobo-kissing and bonobo-tongue-sucking seem to be separate mechanisms. Sometimes after a fight Bonobos even kiss and make up. I’ve been turning on the kitchen fan when I wash my plate. -CM

Masthead*

MANAGING EDITORS

Charlie Medeiros

Angela Qian

Lily Seltz

WEEK IN REVIEW

Christina Peng

Jean Wanlass

ARTS

Cecilia Barron

Nora Mathews

Kolya Shields

EPHEMERA

Quinn Erickson

Lucas Galarza

FEATURES

Madeline Canfield

Lola Simon

Ella Spungen

LITERARY

Evan Donnachie

Tierra Sherlock

Everest Maya Tudor

METRO

Kian Braulik

Cameron Leo

Nicholas Miller

SCIENCE + TECH

Mariana Fajnzylber

Lucia Kan-Sperling

Caleb Stutman-Shaw

WORLD

Tanvi Anand

Arman Deendar

Angela Lian (feat. Kolya Shields)

X

Claire Chasse

Joshua Koolik

DEAR INDY

Solveig Asplund

LIST

Chachi Banks

Saraphina Forman

BULLETIN BOARD

Qiaoying Chen

Angelina Rios-Galindo

STAFF WRITERS

Aboud Ashhab

Maya Avelino

Benjamin Balint-Kurti

Beto Beveridge

Dri de Faria

Keelin Gaughan

Jonathan Green

Emilie Guan

Yunan/Olivia He

Dana Herrnstadt

Jenny Hu

Anushka Kataruka

Corinne Leong

Priyanka Mahat

Sarah McGrath

Kayla Morrison

Abani Neferkara

Luca Suarez

Julia Vaz

Siqi/Kathy Wang

Zihan Zhang

Daniel Zheng

COPY CHIEF

Addie Allen

COPY EDITORS / FACT-CHECKERS

Rafael Ash

Elaina Bayard

Victoria Dickstein

Maria Diniz

Benjamin Flaumenhaft

Anji Friedbaur

Dylan Griffiths

Sam Ho

Becca Martin-Welp

Nadia Mazonson

Adelaide Ng

Taleen Sample

DEVELOPMENT

COORDINATORS

Corinne Leong

Angela Lian

Ella Spungen

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Jolie Barnard

Kian Braulik

Angela Lian

Kolya Shields

Yuna Shprecter

*Our Beloved Staff

Mission Statement

COVER COORDINATOR

TBD

DESIGN EDITORS

Gina Kang

Ash Ma

Sam Stewart

DESIGNERS

Jolin Chen

Riley Cruzcosa

Sejal Gupta

Kira Held

Xinyu/Sara Hu

Avery Li

Anahis Luna

Tanya Qu

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Eiffel Sunga

Simon Yang

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Julia Cheng

Izzy Roth-Dishy

Livia Weiner

ILLUSTRATORS

Sylvie Bartusek

Aidan Xin-he Choi

Avanee Dalmia

Michelle Ding

Anna Fischler

Lilly Fisher

Haimeng Ge

Seungwoo Hong

Ned Kennedy

Avery Li

Mingjia Li

Ren Long

Jessica Ruan

Meri Sanders

Sofia Schreiber

Isa Sharfstein

Luca Suarez

WEB EDITORS

Kian Braulik

Hadley Dalton

Matisse Doucet

Michael Ma

MVP

Kolya

The College Hill Independent is printed by TCI in Seekonk, MA

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and selfcritical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

* THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT 01 00 “SLIDE RUNE” Mason Hunt 02 WEEK IN AIR CONDITIONING Riley Gramley 03 THE LEGACY QUESTION Owen Dahlkamp 06 MAGIC ROCK Mindy Ji 07 ISRAELI DELEUZIAN FORCES James L. 09 FACE TURNED TOWARD UPSETTING SUN; GARDEN OF IMPROBABLE DELIGHTS Emilie Guan 10 OPPORTUNITY ROVER Annie Wu 11 THIS SENTENCE IS JUST A PLATITUDE Corinne Leong 13 HATE ME TENDER Kian Braulik 15 OVER EASY CHOICES: PLANNING IN AN AGE OF CRYOPRESERVATION Cecilia Barron 17 PARTY GROUP THERAPY Kailin Hartley 18 DEAR INDY: CRUSHING IT Solveig Asplund

BULLETIN Qiaoying Chen & Angelina Rios-Galindo This Issue

19

47 02 09.22

Letters to the editor are welcome; scan the QR code here or email us at theindy@gmail.com!

→ Are you sticky? Is it hard to get to sleep? Is that small Scandinavian sauna your eccentric aunt was perusing on eBay actually your Grad B single? If you answered “yes” to at least one of these questions, you’ve probably noticed that 1) You're living in an un-air-conditioned building and 2) It's really hot outside. In fact, Providence was so hot the week of fall move-in that you began to plot a break-and-entry—you'd wait by the door of Greg (air-conditioned), or the new dorms (250 Brook Street or Danoff Hall, both air-conditioned)—and follow an ID-carrying resident into their dorm. Then, you'd find one of their kitchens and perch yourself on three stools for the duration of your HVAC-induced slumber.

All over our beloved College Hill, students found ways to escape the heat. The MCM concentrator from my playwriting class, who introduces himself by gushing about his second home in Sun Valley, Idaho, booked a stay at an air-conditioned hotel room for several days. The Econ concentrator who refers to his dad as “my father” found reprieve from the heat in his white Tesla. Phew! And, yesterday, I overheard the Italian mining heiress in my "Introduction to Gender and Sexuality Studies" class say to her friends that the state-of-the-art cooling system she installed in her off-campus residence has been a real lifesaver. Thank God! But for the rest of us, who might not have the luxury of an air-conditioned getaway, places like the CIT have been converted into our own personal air-conditioned sanctuaries.

Here are a few helpful tips you might want to employ if you're getting too hot. First, you could turn on a hand dryer in your communal bathroom and squat under it. Let the almost-cool air dry your sweat before someone on your floor asks if you’re okay. Second, you could buy one of those super cool water beds and instead of sleeping on top of it, sleep inside it. Cut a hole in the blue plastic and slip right in. Remember to be sure your head is peeking out so you don’t get trapped in there. Or, instead, you could take my third piece of advice: Walk north for hundreds and thousands of miles until you hit the Arctic Circle. Hopefully, by the time you get there, it isn’t moonlighting as a tropical vacay! In case it is, don't forget to pack your swim trunks and sunscreen (especially the sunscreen—you don’t want wrinkles amidst the apocalypse). Fourth, and my last piece of advice, try to storm Shell headquarters, blow up a pipeline, or sink an oil rig.

But, before you grab your pipe bomb kit or adventure to that oil rig, you and your fellow Brunonians could start at home and organize around this air-conditioning thing. Perhaps read this article less as a complaint and more as a manifesto. Okay, here comes the downer…we live on a boiling planet—extracted from, deforested, polluted. Ecosystems are collapsing. New England cities broke heat records early this September. We just lived through the hottest three months on record. Some of Brown’s buildings, at least all the un-air-conditioned ones, demonstrate how vulnerable students are to this sort of extreme heat. When UCS lobbied for free laundry, they guaranteed that right for everyone, at least for the near future. With AC in some buildings and not in others, students aren't on a level playing field. And if we rely on CPax, or that one Swedish teenager, we probably aren't going to get all our dorms air-conditioned any time soon, no less save our one home planet.

While I muse about our deteriorating planet, it might be important to remember the environmental impacts of air conditioning. Installing AC units in the buildings that don’t already have them would mean that Brown consumes more energy and relies on cooling systems that

produce more greenhouse Gases. Perhaps AC is a necessary evil—at least I can be cool while my classmates flirt with corporate oil at the job fair. And, if there's one thing I’m certain about, it’s that not all buildings were created temperature-equal. I have to wear a sweater in the air-conditioned Rock. In my dorm room, I have to essentially place my fan on top of my body. In about every other building on campus, I have to perform a choreographed layering and delayering routine depending on its relationship to AC. Sometimes I feel like I’m slowly boiling in a vegetable stock. But, other times, in the cool hallways of Greg, for example, my mind goes quiet, as if I’m strolling the freezing basecamps of several Himalayan peaks. Thankfully it's starting to cool down. Recently, I’ve been able to turn off one of my two sad oscillating fans and I’m considering that a huge win. And with Brown’s history of flooding—the great Archibald flood of 2022, for instance—I’m glad I’m not on the ground level of my dorm as the onset of fall brings more rain. At least I don't have to worry about those big annoying puddles strewn across the carpeting! Woohoo! However, when it gets really hot, when I start to languish in the middle hours of the afternoon heat and the sun seems to pierce everything around me, when the humidity is unbearable and my thoughts begin to run and tangle, I sometimes fantasize about jumping into that rainwater. Maybe Brown’s infrastructure, poorly adapted to extreme weather, isn't that bad after all. So, I begin to imagine the water amassing. I begin to imagine the flooded floors turning into a reservoir. I begin to imagine taking a refreshing swim, finally cooling off.

WEEK IN REVIEW VOLUME 47 ISSUE 02 02

RILEY GRAMLEY B’25.5 is wondering how to scale an oil rig.

( TEXT RILEY GRAMLEY DESIGN SEJAL GUPTA ILLUSTRATION AVERY LI )

Alumni preferences after the fall of affirmative action

→ In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s June decision to restrict race-conscious practices in college admission—often called “affirmative action”—higher education institutions across the country are scrambling to find an alternative path to maintain a diverse student body. History has shown the stakes of such a decision: In 1996, California passed a measure that eliminated race-conscious admissions in public universities. In the following 27 years, California’s public colleges have been unable to produce a blueprint for administrators to cope with the end of affirmative action.

Now, universities nationwide have taken up California’s struggle to maintain racial diversity, considering novel admissions practices to be tested in the coming years. In an unexpected twist, some advocates have begun to push a tool often thought of as an enemy to diversity in universities: legacy preferences in admission.

While each institution defines “legacy applicants” differently, Brown considers them to be children of one or more parents who completed an undergraduate degree at the University. According to the Office of College Admission, this criterion is considered “when it comes to choosing among equally strong candidates” but “does not ensure admission.”

Opponents of legacy preferences have long contended that increasing reliance on this century-old practice would only exacerbate the racial inequity in the selection process. Its proponents, however, claim that years of affirmative action have actually led to an increasingly diverse alumni community— including many Black and Hispanic alumni—whose children will benefit from legacy admissions. +++

This fall, Brown’s five percent acceptance rate looms as a daunting prospect over stressed high school seniors; hunched over their computers, these students search for the perfect three-word description of themselves to trot out in application after application.

Historically, some methods employed by prospective Brunonians to catch the attention of their application reviewers have been creative, to say the least. In 1985, a Brown admissions officer told a Brown Daily Herald reporter about one application that

included pictures of the applicant in a “string bikini,” with the caption, “I hope you get as complete a picture of me as possible.” Another applicant sent a bottle of alcoholic brew to the Admissions Office (homemade, of course). In yet another instance, a scantily-clad applicant submitted a photo of herself with a large snake coiled around her neck. Admissions officers lovingly dubbed her the “snake lady.” Verging on the perverse, these efforts demonstrate just how far applicants will go to receive a second glance during consideration. These stunts are unorthodox, but other extraneous factors remain influential in the review process—chief among them being the use of legacy preferences.

Until as recently as 2011, the University of Pennsylvania employed an Alumni Admissions Resource Center, “an office devoted to families who had children going through the admissions process,” Sara Harberson, a former UPenn admissions officer, told the College Hill Independent. The university admissions office even had a separate committee in which legacy applicants were considered.

Today, around eight percent of Brown’s student body has at least one parent who graduated from the College’s undergraduate program. The acceptance rate for legacy applicants has soared far above the University’s average, with a 51 percent rate in 1998 and a 40 percent rate in 2001. The overall selectivity for these years hovered around 15 percent. The Indy requested the current acceptance rate for legacy admits from the Office of College Admission, but did not receive a response.

Fast-forward two decades, and students applying to the selective Ivy Plus institutions with alumni relatives are three to five times more likely to be admitted compared to an applicant without that privilege. This difference becomes even more pronounced as the applicants’ familial wealth increases.

An alumni connection to the University is in no way a guarantee of admission, but legacy applicants who clearly don’t meet Brown’s standards have been given far more leeway than non-legacies with similar credentials. One 1985 admission file reviewed by the Indy was laden with negative descriptors of a legacy applicant, with an alumni interviewer going so far as to call the applicant in question “not quite a person.” The admissions committee ultimately rejected her application, but not without fearing how they would inform her father—a former

student. “Who wants to talk to her father?” one officer asked. Each deflected responsibility for the task until the Director of Admission volunteered, citing his long-standing relationship with the alumnus: “the father won’t talk to anyone but me.”

+++

Prior to the ruling, Brown’s Associate Provost for Enrollment Logan Powell was among the first at the University to suggest that increasing reliance on legacy consideration would provide a means to maintain diversity. “We have admitted increasingly diverse classes of students, which means that their children are increasingly diverse,” Powell said during a presentation to faculty prior to the ruling. He noted that onethird of legacy students self-identify as students of color—a number verified by on-campus polls taken by the BDH.

In a recent article for The Atlantic, Brown graduate Xochitl Gonzalez echoed Powell’s opinion, writing that “for the children of minority alumni, legacy admission remains one consistent pipeline to college.” For Gonzalez, without affirmative action, it is naïve to think that the coveted spots in the next class of Ivy-leaguers will “go to low-income students of color.” However, she maintains that ending legacy preferences won’t change the university’s overwhelmingly white, well-off composition either. Gonzalez currently sits as a trustee for the Corporation of Brown University, the highest governing body at the university, and maintains jurisdiction over sweeping policy changes.

Not everyone is convinced that legacy preferences can be used to diversify Ivy League schools. In July, the legal organization Lawyers for Civil Rights (LCR) filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education against Harvard, alleging that the practice discriminates against minority applicants. “Removing legacy preferences,” the lawyers argue, “would increase admissions for applicants of color.” In response, the Department has opened an investigation into Harvard University.

A recent study by Brown economics professor John Friedman concluded that eliminating legacy preferences would result in a mere 3 percent increase in the number of students from the bottom 95 percent of household income earners: only 46 additional students.

Whether or not it’s effective for maintaining

METRO * THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT 03

( TEXT OWEN DAHLKAMP DESIGN RILEY CRUZCOSA ILLUSTRATION SYLVIE BARTUSEK )

racial diversity today, the history of legacy has been fraught with discrimination. In the 1930s, schools began adopting legacy preferences as a reaction to anti-Semitic rhetoric in the United States. In fact, a popular college song at the time illustrates the Jewish sentiment on Ivy League campuses: “Oh, Harvard’s run by millionaires/ And Yale is run by booze/Cornell is run by farmers’ sons/Columbia’s run by Jews.”

Terrified of being ‘stained’ by the same label as Columbia, then-Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell prioritized preventing “a dangerous increase in the proportion of Jews” in collegiate institutions nationwide. This fear sparked the “holistic review process,” which expanded the set of criteria considered during application review beyond academic achievement. Among the new criteria was a preference for prospective students whose family members had previously attended the university.

In order to exclude Jewish students, nearly all universities at the time, including Brown, marched in lock-step, implementing a preference for children of alumni: a predominantly Protestant population.

“It’s not just Harvard,” Michael Kippins, litigation fellow at LCR, told the Indy. “[Legacy] is certainly a nationwide issue that needs to be taken care of and eliminated on a widespread basis.”

Harberson, now an independent college counselor and founder of consulting company Application Nation, echoed Kippins, arguing that this new excuse for keeping legacy around is merely a way to maintain the status quo at a time when legacy is under increased “public scrutiny.”

“Where were these colleges 10? 20? 30? 40 years ago?” she pondered. “Why weren’t they ensuring that underrepresented minorities were being represented in larger numbers [using legacy preferences]? To rest on this argument, I think, is just hanging onto a thread.”

Sanford Williams, a law professor at U.C.L.A., has been reckoning with this topic in relation to his own family’s experience.

Williams attended the University of Virginia. So did his wife. And so did his three daughters. “It’s kind of neat having that connection,” he told the Indy. “Five of us went to UVA, which is something that can never be taken away from us.”

Prior to the fall of affirmative action, Williams publicly defended legacy preferences in

admissions from his position as a Black alumnus. But since the Supreme Court’s decision, he’s changed his tune. “The Court seems to just not comprehend that race is still a huge issue in our society,” he said.

Privately, he mulled over the ruling, weighing its benefits to children of white and minority alumni. Ultimately, he reversed his sympa-

applicants. In response, the organization cites Friedman’s study which says that “the children of alumni of a given Ivy-plus college have no higher chance [than other applicants] of being admitted to other Ivy-plus colleges” when controlling for familial income. If legacy students were purely more qualified, the data would show a higher acceptance rate across the board.

Increasing reliance on legacy preferences may result in public outcry, forcing universities to look for other measures to prevent a plunge in student body diversity. +++

With legacy preferences under fire, Brown recently announced the formation of an Ad Hoc Committee on Admissions to investigate, among other policies, legacy preferences. Composed of members of the university’s corporation, faculty, and Provost Francis J. Doyle, the group will use a data-driven approach to consider changes to the practice.

Several alumni, whose children may benefit from legacy preferences, sit on this board. One committee member and professor of Africana Studies, Nowile Rooks, has publicly supported familial preferences as a means to bolster campus diversity.

thetic stance toward legacy admissions. “I can't with good conscience say, ‘yes, legacy preferences should be granted’ since they benefit mostly folks who are white,” he said. “There are so few people of color who can benefit from it.”

Students fighting for fairness in admissions on College Hill overwhelmingly concur. One student group, Students for Educational Equity, has held protests outside University Hall (where many influential administrators work) urging Brown to stop considering applicants’ familial ties.

Nick Lee, co-lead of S.E.E.’s Admissions and Access Committee, asserted that legacy is “inherently problematic and essentially repeats a cycle of allowing the richest and most supported individuals to get into top universities.”

One common argument S.E.E. encounters is that legacy students are simply more qualified

Notably absent from the committee, however, are staff members in the Office of College Admission and student representatives. In an interview with the BDH, Provost Doyle said that they plan to consult the admissions staff throughout the process, pulling “together the appropriate experts across the University ecosystem.”

Student activists have voiced their disappointment at not being included in the discussions. Asked about their absence, Doyle cited the review’s intended inclusion of “highly confidential” and “highly specific” information. “We did not want to place our students in a conflicted situation,” he said.

In response, co-president of S.E.E., Niyanta Nepal, told the Indy that Brown could “still integrate students and have them participate with the understanding that it is confidential information they're working with. The idea of having students serve on that committee would also help increase the level of transparency.” +++

METRO 04 VOLUME 47 ISSUE 02

“I can't with good conscience say, ‘yes, legacy preferences should be granted’ since they benefit mostly folks who are white,” Williams said.

“There are so few people of color who can benefit from it.”

“Diversity changes lives,” Williams, the U.C.L.A. law professor, said. “When you have a diverse group of people, you get exposure to people and ways of thinking that totally change how you perceive the world.”

As the Ad Hoc Committee weighs the fate of future Brown classes in their hands, stakeholders like Williams have begun to suggest alternative measures in pursuit of racial diversity. He specifically suggested that the work starts before some students even consider their collegiate plans; he says that ensuring “equitable resources nationwide” for Pre-K through 12th-grade students will make a substantial difference. Harberson and Kippins agree.

Harberson believes that admissions departments nationwide may focus applicant recruitment in rural areas and high schools whose graduates are less likely to attend a four-year university. Brown already has two such programs—one providing local Providence high school students with resources to guide them in the admissions process and one encouraging students from rural backgrounds to apply and attend Brown.

Nepal also pointed to fly-in programs for underserved communities to “help them access Brown before they apply and make it feel like a more accessible place.” The University currently hosts a no-cost fly-in program for rural and small town students, with the next visit planned for October 2023. The University has also committed to covering travel costs for low-income, admitted students who wish to visit campus before committing.

Kippins said that increased emphasis on recruiting students from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and first-generation students will be central to the effort to undo a legacy of exclusion.

Wary of ending legacy, many universities are adding new supplemental essay prompts to their applications, asking students to expand upon their lived experiences. These prompts do not explicitly ask a student to discuss their race, but they leave the door open to do so. In admitting the class of 2028, Brown has added several new supplements, including asking students to write about “where they came from” and how “an aspect of [their] growing up has inspired or challenged [them].” Some are even more explicit: Johns Hopkins asks students to write about “an aspect of [their] identity or a life experience” that has shaped them. Duke asks students to describe “any ways in which

[they’re] different,” and the impact on them as an individual.

Nepal empathized with students asked to write these new supplements, remembering “what it was like to feel icky about that and to not feel comfortable necessarily discussing” her race. She hoped that as students draft their essays, they would “feel authentic in their delivery of who they are” without having to “tokenize” their identity.

As Harberson advises students on their applications, she has noticed less emphasis being placed on their legacy status compared to past years. In response, she posited a hypothetical that sums up what she thinks colleges are prioritizing: “if there is a student of color, who is a legacy at Brown, my gosh, the thing that is most powerful to me, is not that their parents went to Brown — it’s why they want to go to Brown as they bring in their culture, their race, their ethnicity, and how they’ve been raised” into the fold. +++

Of all those who spoke with the Indy, not one said that they were surprised by the Justices’ ruling on affirmative action. Instead, each said that they were consciously bracing themselves as the decision was handed down by a conservative-dominanted Court. But notably, Justices on either side of the affirmative action issue argued in tandem against legacy preferences.

In her dissent, liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor likened college admissions to a complex puzzle, in which many of its pieces, including legacy, “disfavor underrepresented racial minorities.” The traditionally conservative Justice, Neil Gorsuch, concurred with the Court’s opinion, but agreed with Sotomayor on legacy, writing that colleges’ “preferences for the children of donors, alumni, and faculty are no help to applicants who cannot boast of their parents’ good fortune or trips to the alumni tent all their lives.”

We can see in states that have banned affirmative action—like California and Michigan— the possible consequences of the June ruling: the percentages of Black and Hispanic students on these campuses were slashed in half. These changes were not met without a fight: California, for example, substituted the use of race in admissions by using zip codes, recruiting students from racially diverse high schools, and assigning “adversity scores” to applicants. None of these efforts have succeeded in restoring the diversity that Golden State campuses

once enjoyed.

Powell is turning to intentional recruitment as one focus the University will take in a post-affirmative action world. Prior to the ruling, he said that the administration’s “hope is that by expanding the pipeline of really talented students from diverse backgrounds,” they would be able to maintain and bolster the racial composition of the student body.

Despite Powell’s optimism, the landscape looks bleak: in 2018, Harvard itself ran a simulation showing that there is no comparable ‘race-neutral’ alternative that maintains the diversity of its current student body. Not eliminating early action programs. Not eliminating standardized test scores. And not even eliminating legacy preferences. So how can we stave off the seemingly inevitable loss of diversity, as seen in California? The truth is: we don’t know for sure.

As the Ad Hoc Committee on Admissions meets behind closed doors in University Hall, they hold the fate of the next generation of prospective applicants in their hands. The responsibility to thwart the return to racial homogenization that legacy status once ensured now rests squarely on the shoulders of a committee composed of alumni, Corporation members, and statisticians. The Brown community, along with those high school seniors hunched over their computers, are waiting to see what they come up with.

METRO * THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT 05

OWEN DAHLKAMP B’26 is still thinking of three words to describe himself.

Most summers, I make it to the Blue Ridge Mountains. For me, the Mountains are synonymous with a number of things: a reprieve from the heat of the Piedmont, swimming, bugs everywhere—if not the bugs themselves, then their webs, their molt, and their carcasses—and mica.

You don’t have to look hard to find mica. It’s awfully shiny in its natural state, and most times you’re not so much looking to find it as you are blinded by it. It first caught my eye at the bottom of the North Toe River, rounds of mica around the size of my pinky nail. Later, I would mistake its thin, flaky plates for plastic wrap litter. Its dust glittered my clothes, the wood floors of cabins, the upholstery of my car. A neighbor let me dig for it on his property, a contender for mica extraction back when Spruce Pine was a more prolific mining district. One only had to move aside the leaf cover to find great big hunks of it covered in moss.

The thing about mica is: its abundance is what makes it so magical. There is no such thing as diminishing returns when it comes to finding mica.

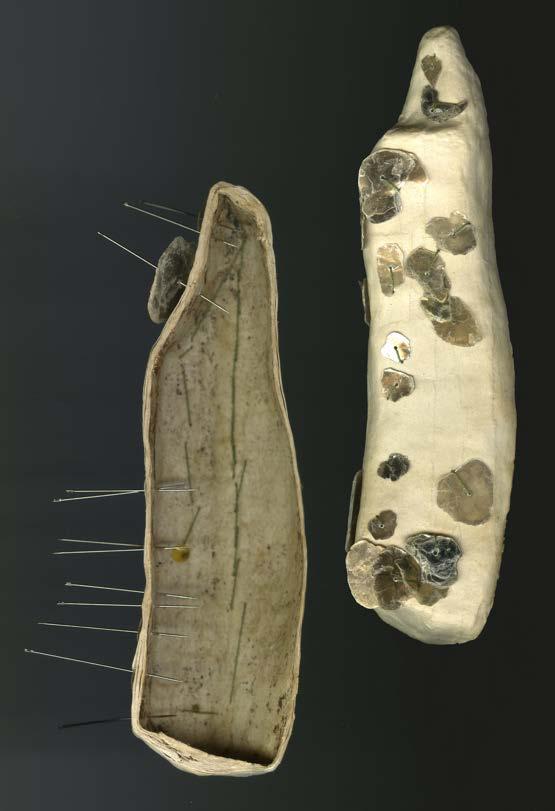

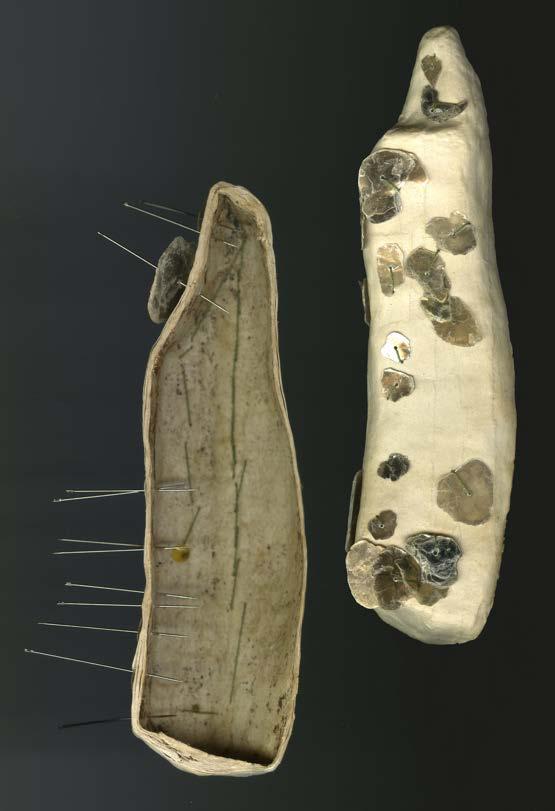

Magic Rock is a Blue Ridge rock-in-progress. One of a multiple, you can find it (finished) at the bottom of the North Toe, on my neighbor’s property, or in and around Spruce Pine.

X 06

Mindy Ji B’24

Magic Rock paper mâché, thread, mica

VOLUME 47 ISSUE 02

Israeli Deleuzian Forces

Or, The ‘Theorywashing’ of Occupation

→ Trapped between the inefficacy of Marxist projects in Eastern Europe, the fragmentation of leftist coalitions in the West, and the decaying of its own institutions, 1960s France found itself in a state of moral, political, and social panic. This national crisis culminated in a period of unprecedented civil unrest between May and June 1968. During Mai 68—the month that lasted seven weeks—student- and worker-led protests shut down universities, factories, and government buildings across the country. The litany of philosophical musings that bled out of the post-1968 intellectual frenzy would, years later, come to be named ‘French Theory’—anathema to some, ravishing for others, and completely unknown to most. Among its canon are self-declared post-Marxists, postmodernists, poststructuralists—thinkers mutually disillusioned with Western Europe’s chronic inability to ‘do communism for real this time.’

One such intellectual to sprout from this tumult was Gilles Deleuze. Deleuze is perhaps best remembered for his arcane philosophy and frequent collaborations with Félix Guattari, a militant Marxist activist and psychoanalyst. From 1969 until his retirement in 1987, Deleuze taught at Université Paris 8, a fledgling university on the ideological and geographical fringes of Paris.

For students on College Hill, Deleuze may be a curious case: he’s not the first French theorist to whom an impressionable first-year humanities student may be exposed in a cultural anthropology class (that would be Michel Foucault). Nor is Deleuze usually the first person to come to mind when prompted to name a French philosopher whose name starts with D (Diderot. Wait, no, Derrida). Yet the terms that Deleuze and Guattari popularized in their writings have seeped their way into seminars on literature, film, and the social sciences; we often encounter their fiery writings on, for example, rhizomes, the time-image, or the ‘Anti-Oedipus.’

As obscure as Deleuze may be outside of elite academic circles, his impact is farther-reaching than we give him credit for. As far-reaching, it turns out, as the strategy rooms of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), the military force tasked with protecting and legitimizing the violent occupation of Palestine. I’m slightly embarrassed to admit—though who can blame me?—that I learned of the IDF’s embrace of Deleuze this summer on the social media platform then-named Twitter. “Incredible how Deleuze has inspired so many over the years: accelerationists, the IDF, that guy that created buzzfeed [sic],” marveled a user who, despite not being followed by me, had garnered enough attention from the digital intelligentsia to show up on my timeline.

Though I can’t fully remember my initial reaction upon reading the tweet—I probably DMed it to my twin brother moments later—it certainly was not one of shock. I had long graduated from the stage of intellectual maturation during which you realize that reading theory does not automatically make you a good person. I likely just continued scrolling. Yet the image of an IDF general poring over a copy of Capitalism and Schizophrenia refused to escape my head. I was bemused. Horrified, even. What about Deleuze could possibly appeal to the Israeli military? So I went digging.

In a 2006 article for the contemporary art magazine Frieze, British-Israeli architect Eyal Weizman describes how military strategists have used the works of thinkers like Deleuze and Guattari to reconceptualize the urban arenas of warfare. Through an interview with Shimon Naveh, a retired IDF Brigadier-General and director of the now-defunct Operational Theory Research Institute (OTRI), Weizman explains the development of “military operational theory,” a “‘shadow world’ of military urban research institutes and training centres that have been established to rethink military operations in cities.”

Naveh is brawny, brash, and, admittedly, very well-read. (In a

separate profile for the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, he’s described as “Foucault on steroids.”) At one point in his interview with Weizman, he somewhat innocuously shares, “Without theory we could not make sense of different events that happen around us and that would otherwise seem disconnected.” (This shouldn’t be too hard to agree with.) Later on, Naveh asserts that the IDF must “combine theory and practice. We can read but we know as well how to build and destroy and sometimes kill.” (Never mind.)

What is being destroyed here? And who is being killed? At the time of this article’s publication, the OTRI was crucial in ‘theorywashing’ Israeli military actions through the esoteric language of French theory. Deleuze’s poststructuralist theory sets out to destabilize notions of hierarchy, form, and order. His “rhizomatic” approach, borrowing from the botanical term for a root that adventitiously grows underground, questions our predilection for reading the world through rigid frames and structures.

In the pioneering text A Thousand Plateaus, for example, Deleuze and Guattari differentiate between “smooth” and “striated” spaces. Simply put, striated spaces contain fixed and distinct elements; smooth spaces elude conventional categorization and find themselves in a constant state of transformation. Smooth and striated spaces never exist independently from one another; rather, Deleuze and Guattari devise this distinction to explain how an entity as singular as, say, a city contains within it endless multiplicities.

In April 2002, nearly two years into a period of Palestinian resistance called the Second Intifada, Israeli forces descended upon the city of Nablus. As troops moved to occupy most of the Palestinian city, they effectively smoothed Nablus out, moving through civilian communities as if, Naveh says, “it had no borders.” (Israeli forces killed at least 78 Palestinians in the Battle of Nablus; by contrast, only one Israeli died—by friendly fire.) In this analogy, it follows that occupied lands are striated spaces; the innumerable fences, walls, and roadblocks erected by Israeli occupying forces serve to immure Palestinians.

We can see how similarities can be drawn between poststructuralist philosophy’s aversion to stability and structure and the dynamism

WORLD * THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT 07

+++

( TEXT James L. DESIGN Anahis Luna & Ash Ma ILLUSTRATION Livia Weiner )

“war machine.” The war machine is not uniformly defined, but it’s an attempt at articulating the force behind human movement and social developments. It’s not necessarily belligerent; the real danger, we are warned, lies in the appropriation of the war machine by the State. What ensues is the creation of “new nonorganic social relations,” the normalization of states trudging towards a tenuous state of “peace still more terrifying than fascist death.”

In “Spoilers of Peace,” a 1978 essay that originally appeared in the French newspaper Le Monde, Deleuze asks us, “How could the Palestinians be ‘genuine partners’ in peace talks when they have no country?” In another interview translated into English as “The Indians of Palestine,” Deleuze similarly laments the statelessness of Palestinians under Israeli occupation: “The Palestinians are not in the situation of colonized peoples but of evacuees, of people driven out… it is a matter of emptying a territory of its people in order to make a leap forward.” That’s all to say, attempts to subsume Deleuze’s writing into an ongoing Zionist project require a particularly impressive degree of mental gymnastics.

Weizman documents how Naveh and his compatriots willfully misinterpret Deleuze and Guattari’s neologisms; terms like “war machine” feature in the literature produced by the OTRI. The idea that the Deleuzian war machine could stand to critique the “hideous mutilations” committed by a state like Israel is not completely lost on Naveh. He notes, “ The disruptive capacity in theory is the aspect of theory that we like and use… This theory is not married to its socialist ideals.” Despite whatever obtuse jargon the IDF may use to euphemize its practices, the goal of Israeli military operational theory remains transparent: “It is essential never to use one’s full destructive capacity but rather to maintain the potential to escalate the level of atrocity. Otherwise threats become meaningless.”

There are massive contradictions at play here. Yet, it can be argued, there is a flip side to the rejection of fixity and certainty that Deleuze and Guattari espouse: theory is rendered more manipulable. And in this case, Palestinians become victims of the defanging of Deleuze’s words. A regime of words materializes on occupied lands; the state grinds the gears of its war machine and kills.

A couple of semesters back, a literature professor of mine quipped, “Theory was born in France, shipped to the United States, and died somewhere along the way.” On November 4th, 1995, Gilles Deleuze died by suicide, jumping out of the window of his Paris apartment. He was seventy years old. I won’t try here to analogize Deleuze’s death-bysuicide to the death-by-deliberate-misinterpretation of his philosophy, nor to the purported death of whatever philosophical tradition from which Deleuze may have originated. I will note, however, that French Theory was never actually a politically cohesive project. Many of the movement’s best-known thinkers—if we can even conceive of French Theory as a coherent movement—hesitated to call themselves Marxists, communists, or radicals at the peak of their careers. At the end of the day, French Theory was a catch-all term devised by American intellectuals to categorize currents of philosophical intrigue that were being maligned, if not wholly ignored, by the French academy at the time. I’m not interested in debating whether French Theory was ever destined to save us from colonial-capitalist treachery. What intrigues me instead are the mechanisms behind its reception and subsequent circulation—in the United States, occupied Palestine, and elsewhere. Elite institutions that initially welcomed countercultural, unconventional theories continue to hoard wealth, dismantle tenure, and insidiously appropriate language designated to critique injustice. Even here on College Hill, we have the recent memory of months-long worker strikes at RISD, tuition fixing scandals, and the legacy of Brown Corporation members investing in the Zionist industrial complex on which to reflect. Deleuze may not feature on as many humanities syllabi as he did in the 90s; yet, the American university hellscape has made it entirely possible for a tenured professor to cross a graduate-student-led picket line to lead a lecture on decolonial praxis.

The Operational Theory Research Institute that Shimon Naveh headed over fifteen years ago is now defunct. In fact, I struggle to find recent information that would indicate Deleuze is still actively being read by IDF affiliates. The OTRI, it would seem, was absorbed into the Dado Center for Interdisciplinary Military Studies, a research center that continues to offer ‘theorywashed’ support to the IDF. Here, Deleuze can help us understand how the ideological remnants of fallen institutions never fully perish. As we attempt to critique and chip away at institutions like the state, they mutate; they transform and rebuild themselves. Let’s return to the “death of theory” that my literature professor portended. Indeed, I must ask myself how worthwhile this exercise has been. I don’t believe that theory is dead. On the other hand, I see this as an example of how we must use theory to make sense of the contradictions that produce our current material reality. The IDF’s dalliance with Deleuze is a contradiction. So too is the Zionist occupation of Palestine, which paradoxically demands the subjugation of Palestinians to assert itself as the Middle East’s only ‘true’ democracy. It is ultimately by remaining wary of the fetishization of revolutionary ideas, of our institutions’ tendencies to curricularize concepts no longer deemed threatening, that we sharpen theory’s claws.

WORLD 08 VOLUME 47 ISSUE 02

+++

JAMES L. B’24 listens to the Red Scare podcast to go to sleep.

Face Turned Towards Upsetting Sun

yoked to a buddha statue I found irony inside like a small figure sleeping I never prayed because I didn’t want to wake anything I’d have to answer to fairies were something to stop believing in stop worshiping with fisted daffodil crowns and lifting the underside of curious leaves so I clasped on and became one what grueling work searching for promises in the dark prising a rooted head from the sky biting hard enough to cut these moss-glass wings what if what makes me and call it reinvention?

I collect teeth for anything hard to swallow and find questions wasp-nested like

in shallow mounds oh believe me I’ve only been using the language of what slithers across the ground to describe the wholly dead it’s much closer to only truth only gleamings

only what I would never say in thinned daylight never long ago I stayed landlocked and milk spoiled and eternally distrustful like that old trek to the temples to people-watch fairy-catch and hunger light incense as flare lights slit dreams of snakeskin and splitting should be enough good material for prayer

is it unfair sometimes I ask for things and end up believing a response.

EMILIE GUAN B’26 is praying for cooler weather.

LIT * THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT 09

Garden of Improbable Delights

from the pulpy pit of the world I shave the skin of ghost pears and make paint swatches out of the peeling afterburn like burial-salmon like yolk nervous of glancing pain yet every expanse tastes the same as if the tongue can’t imagine itself coated in the sweet corpse yellowing and other burns of an unknown when I think of heaven it’s where the sun haloes a mountain not a god where we crouch beside its earthly rust-roots and are unbelievably small like speckled voices carving a question and in the damned garden those golden pears tumble down the cragged face of descent craving cut hands to dislodge a terrible dawning of truth god I don’t know how to break it to you but we were never placed anywhere by any winged vessel or all-squinting eye or even foolish blessing if anything we threw ourselves off the cliffside out of time’s sight like most universes we burst in here with pepper-heat and the vertigo of holding a weight now in the rotting should we be asking how we leave like bloodlines severing like slow myth down the throat the image evokes itself and I heard in the end there was an unspooling of light from human eye.

EMILIE GUAN B’26 is praying for cooler weather.

Opportunity Rover

Red rock wedged between my toes as sun rises & sets, the greeting of another horizon bathed in rust. Iron rakes its colors across a sky missing its memories of rain, & desert bleeds loneliness, scattering sand into space. Purpose finds altars in barren places—I found an offering hidden in hematite. Oasis buried itself here: holy water could have been mine, once.

You gifted me with sight & what love to have a world sitting beneath my feet, discovery shoveled into my fingernails. The dirt of Mars coats my body—baptism leaves no surface to break, dust crawling into the deepest parts of me. You spell out your love in an atomic language, crystal lattice brittle bone fragile shifting soundless aching adrift in the joints of my steel skeleton. Dust is a little killer, blots out the sun until I forget how to breathe. The storm eats light alive, but faith rediscovers itself in the darkest hours. I was yours, for a while. But there is no miracle. Distance is our last frontier:

The valley between us is stained with space debris. Among stars, the call of wake up. Where did you go? is not mine to hear. I was not built to weather storms. & Creator, I do not blame you. Infinity is quiet. Sleep, you whisper. I have only known love sweet with creation— Battery low. Sky is dark. Time stops.

ANNIE WU B’27 always appreciates a good café.

( TEXT EMILIE GUAN, ANNIE WU DESIGN SIMON YANG ILLUSTRATION MERI SANDERS )

LIT 10 VOLUME 47 ISSUE 02

From: Corinne Leong <corinne_leong@brown.edu>

→ At least five of my friends and I all applied to the same job over the course of the last year. We never directly competed, though each of us answered an identical question regarding a specific mode of communication. Of concern to our potential employers wasn’t responsiveness (concerning/glacial) or style (sexy/infuriating), but medium. In response, one friend dove into a deconstructive paean of the object in question. Another admitted, “A little more intimate than I’d like it to be.” The arbiters had asked: What is your relationship to email?

If someone came to me for interview prep on this question, I’d tell them to visibly suffer (snivel, wince) for a second or two, because I think it’s meant to be sadistic—its deceptive simplicity, the dark and libidinal charge of the word “relationship,” a tesseract of possible misinterpretations unfolding in perpetuity. After my own interview, I labored far too long over a thank-you email that ended up being about three sentences. The message was both meaningless and perfectly demonstrative of my rich humanity. You could discern my interminable depths because I’d made one joke. It was chaste and took thirty minutes.

As far as email communications go for those born post-millennium, this sense of gravity and its associated demands seem to be typical. My roommate says email is the single greatest source of dread in their life (a provocative interview response). A computer-lab class I endured in elementary school—I never took the typing test because I wore a carpal-tunnel wrist brace the entire year in an act of early Munchausen’s—informed us that we were failing if a respondent couldn’t reply accurately to our messages by subject line alone. Presently, memes about young femmes frantically trying to place exclamation points without turning their drafts into self-shouting matches might now be considered their own genre. But for me, email is dense with a slowness, seriousness, and illusion of analog unavailable elsewhere on the internet. A letter! In my inbox! To me! A well-crafted subject line or postscript—one might as well have slathered on 31 Le Rouge and given the envelope a big kiss. And yet the sanctity of the email space seems to command just as much effort, if not more time per output, than other forms of online performance.

This is a form of suffering I wish had ended in 2014, when Tumblr user ischemgeek claimed in a viral text post to have discovered a solution to email’s strain on hapless Z-ers and Zillennials: a template! “Nobody has figured out yet that it’s the same email with the details changed as needed,” the post noted.

The stock correspondence spans four short paragraphs. “Dear Person I Am Writing To,” the message begins, “This is an optional sentence introducing who I am and work for.” By the closing sentence the sender’s turned biting, if honest: “This sentence is just a platitude (usually thanking them for their time) because people think I’m standoffish, unreasonably demanding, or cold if it’s not included.”

There was a time when the medium didn’t seem so restrictive, at least in terms of content. A 2007 article from n+1’s early years (titled, in a contrast that makes my selection of the following quote seem especially disingenuous, “Against Email”), sardonically extols email’s seeming liveliness: “The true mood of the form is spontaneity, alacrity—the right time to reply to a message is right away.” I know everyone has their own rules, but I find that the appropriate time to respond is any time before the end of the work week, a product of email’s near pure professionalization and geriatrification that occurred when personal communications found even more instantaneous, accountable platforms to die on, like IM and text. The email of 2007 is foreign to me, and so too does it seem to the email of a decade earlier.

Reporting from just two years after the birth of webmail, the Selin in the 1995 of Elif Batuman’s novel The Idiot (2016), too, is fed up with language—though not necessarily that of email. When, as a college freshman, she volunteers as an ESL teacher as a college freshman in Cambridge, she finds simple statements like “the paper is white” half-transmuted by her interlocutor into “papel iss blonk,” “the pen is blue” into “ball iss zool.” “I am now the interpreter of a language that only he and I can understand,” she types furiously to her crush via email. “It makes me so tired, even angry. Why should I have to figure it out? Why don’t any messages come to me clearly?” In another instance, Selin reads a serialized Russian short story constructed only from grammatical structures the students in Slavic 101 have been taught:

Ivan’s father looked at her.

“Don’t you want to find your son?” asked Nina.

Ivan’s father was silent.

“Goodbye,” said Nina.

Ivan’s father did not reply.

Austere and alien, Selin considers the story “ingeniously written,” finding herself completely immersed in “a world where reality mirrored

“Every email I send sounds like somebody else. The next email you send will sound like me.”

the grammar constraints, and what Slavic 101 couldn’t name didn’t exist.” Accordingly, it’s this strange, occult language Selin uses to structure a gutsy first email correspondence to her crush. “Ivan!” she writes. “When you receive this letter, I will be in Siberia.”

To write her way into intimacy, Selin relies on the dependable structure of Slavic 101’s narrative inanities, forging something like a prototypical email template. She soon learns Ivan has a girlfriend and always writes in terrible nonsensical riddles, like a bench-warming court jester who receives a commission each time the audience wants to rip its hair out. His desire, it seems, is not to communicate but to confound. Nonetheless, the push-andpull of the couple’s failure of understanding—a “falling out of language,” as Selin puts it—is tender and evokes the nauseating circularity of first love.

Though they continue to see each other in class, Ivan resists their speaking in person. “I don’t understand why it will trivialize these letters to say hi, or to actually talk to each other,” Selin writes, to which Ivan responds, “When I write to you, I feel … as if my thoughts and moods are directly in the keystrokes. I don’t understand why I want this, because clearly it is really hard to understand. I understand maybe one-third of what you write, and vice versa.” Meaning is beside the point. Language is, too.

Seduction via email is not strictly the purview of fiction. In the same year Batuman’s novel is set, real-life writers Kathy Acker and McKenzie Wark were engaged in extended digital foreplay. Their two-week email correspondence is collected in I’m Very Into You: Correspondence 1995-1996. Perceptively, Matias Viegener’s introduction to the collection notes that “to call [the emails] love letters would exaggerate their tenor and consequence,” theorizing that “[i]f paper letters were best suited for love, perhaps email does best with crushes.” While the pair’s replies occasionally capture gender trouble and past sexual partners, little is funneled into the poetics of conveying interest for the other person, a hallmark of the love letter. Instead, Acker and Wark traffic mostly in high theory (“Emotion moves more slowly and tyrannically than thought (ideas),” says Acker), swapping email threads about Spinoza and Baudrillard, neoconservatism and Pasolini’s crucifixion. After Acker re-confesses her sincere interest in Wark, begging for clarity, Wark affirms her own, then proceeds with a self-conscious reflection on their mode of communication: “If I was sounding evasive or something, I’m sorry about that. I was writing to you from the office and it really wasn’t the place or time to think about what I really wanted to say. My cavalier use of this medium.”

Just as Nina’s story allows Selin to prop up her communication with Ivan, Wark acknowledges how the nascent relationship between email and office culture allows her to strip language of its true, burdensome weight. In leaving the words themselves relatively hollow, they clear space for something ephemeral, aspirational, ambient. Affect and intensity congeal around their words rather than within them, in the white plane just beyond the text.

It’s not clear that the emailers of yesteryear ever envisioned a world in which email was old, or that its presence might one day rival the significance of a handwritten letter—albeit with lesser expectations for the prose within. In 2023, we’ve far surpassed the point at which professionalism and outdated epistolary style became its own dialect, a hymn that takes hours to gargle out, each request or inquiry recited as if by rote memory in the process of constant breakdown. Email’s promise to the language of 2007, to Selin, to Acker and Wark, was an unprecedented immediacy. Against these new and incomprehensible expectations for day-to-day communication, early users created the familiar terrain of expression that now allows us to take refuge from the unrelenting demand to articulate—and the rapid acceleration email prefigured.. It might be that very same medium that now allows us to retreat—both from and the rapid acceleration email prefigured. Where else to hide but that rare holdout in the web’s razed plains?

We draft templates. From words, we strain the yolk of ourselves and sprinkle it back in in the form of predictably cheeky parentheticals and canned jokes. Every email I send sounds like somebody else. The next email you send will sound like me. This isn’t a failure, just a means of feeling for when we’ve tired of speech. Nowadays, I find that to be often. “I want to find a territory with you,” Wark writes to Acker toward the end of their correspondence. I double-check the salutation, comb the body text for typos. “I was deferring something until I found the words…” she says, “but one never finds the words.” I send the email anyway.

CORINNE LEONG B’24

CORINNE LEONG B’24

A.B. English Candidate

(401) XXX-XXXX | corinne_leong@brown.edu

69 Brown Street, Mail # 1930

Providence, RI 02912

S+T * THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT 11 ✉ This Sentence Is Just a Platitude: The email after words

( TEXT CORINNE LEONG DESIGN JOLIN CHEN )

“For me, email is a forest clearing with a charming little brook, a glittering glade dense with a slowness, seriousness, and illusion of analog unavailable elsewhere on the internet. A letter! In my inbox! To me!”

“For me, email is a forest clearing with a charming little brook, a glittering glade dense with a slowness, seriousness, and illusion of analog unavailable elsewhere on the internet. A letter! In my inbox! To me!”

“ We draft templates. From words we strain the yolk of ourselves and sprinkle it back in in the form of predictably cheeky parentheticals and canned jokes.”

S+T 12 VOLUME 47 ISSUE 02 Subject: This Sentence Is Just a Platitude: On [subtitle]

“For me, email is a forest clearing with a charming little brook, a glittering glade dense with a slowness, seriousness, and illusion of analog unavailable elsewhere on the internet. A letter! In my inbox! To me!”

Hate Me Tender

→ Queer wellness company ForThem is currently advertising a first-of-its-kind “gender-tracking app” so that paying subscribers can monitor in real time their “gender evolutions.” Blitzing past any double-takes from hearing the phrase “queer wellness company,” I’m curious about exactly how “biometric data” and “identity check-ins” serve ForThem’s queer patients, who, extrapolating from the website’s concentration of rainbows (rivaled only by the Target Pride section), are likely part of a lucrative market bursting with tweenaged fans of the Alice Oseman graphic-Gesamtkunstwerk-turned-Netflix-binge Heartstopper. As if their cash grab wasn’t blatant enough, recall for another second the fact that telehealth companies aren’t necessarily compliant with HIPAA regulations that protect consumer privacy. According to a report by Pixel Hunt for The Markup, “49 out of 50 telehealth websites [are] sharing health data via Big Tech’s tracking tools.” Maybe privacy just isn’t one of ForThem’s priorities. They’re more used to selling just one product, a binder, in fourteen colors. Whether the company is ill-intentioned or fumbling, their ideas aren’t just stupid but anathema to a community uniquely deprived of privacy. By surveilling an already hyper-surveilled population, ForThem risks not only the safety of their consumers but the perpetuation of a medicalized narrative of transition. C’est la vie, to what’s now become of “queer revolution” and “true community!”

It’s no secret that brands like ForThem prey on young people paying on parents’ credit —incidentally, they call their community “The Playground.” Both in their visuals and online blurbs, ForThem revels in the language of activist circles. Its gayness gets cobbled together out of rainbows and taglines about “holding space for gender euphoria,” in a manner that makes it difficult to recall how those aesthetics and attitudes are meant to instantiate an inclusive gay-people community. Faced with an online platform clearly manipulating these communitarian heuristics, I’m left with a bad taste in my mouth by this urge to hold space, for what does “a tangible IRL and URL community space” look like, exactly? Apparently, a $52 binder ($36.40 for members!). This marketing lingo, dear readers, is an unmistakable appropriation of once-meaningful terminology originating in the transformative justice movement for the benefits of what, in the best case scenario, are a round table of pocket-lining consultants, not covert operatives siphoning trans girl data. I’m compelled to mention that, since ForThem has recently purchased queer blog Autostraddle, their ascendant empire is all but guaranteed. We are long since the ontogenesis of queer assimilation. But when, precisely, did paywalled ‘support’ groups become such a safe bet for burgeoning rainbow corporations’ bottom lines?

+++

Tenderqueer is a term that I use over drinks with friends, to bitch. So-and-so is a total tenderqueer, we went on a couple dates and they asked me to join the polycule. At its most concrete, tenderqueer is an in-group aesthetic and affective concept that emerged in the early 2010s to name a particular brand of polychromatic gay person or gay-person community. As an aesthetic, it catches things like pastels, anime, leg warmers, children’s television merchandise, chokers, decorated septum piercings, roller backpacks, and daisy chains. As a feeling, it emphasizes conflict-aversion, passivity, baby-doll airs, and repurposed therapy-speak (at best, hollow, and at worst, manipulative). Simultaneously effervescent and scathing, “tenderqueer”

describes a facile undercurrent to the visuality and visibility of ‘queer’ aesthetics, an aestheticized dilution of radical politics where rainbow becomes the modus operandi for locking down June margins. In ForThem’s case, this substitution might look like the redefinition of “queer revolution” as “creating our own standards of wellness,” rather than something like Act Up. It’s challenging to find a concrete definition for “tenderqueer” beyond an array of shifting signifiers and aesthetics. Ideally, my use of “tenderqueer” scrutinizes a political rather than personal condition. Various aspects of “tenderqueerness” are worth saving: the therapy-speak that ForThem misappropriates should probably enter common parlance. Regarding others with tenderness is valuable. It’s a delicate balance politicizing the aesthetic without denigrating the individual for their sartorial miscalculations. Tenderqueer is a disorganized aesthetic whose foot soldiers opt into buying multicolored Doc Martens and Sanrio paraphernalia. Further, since tenderqueer has a derogatory connotation, its cultural import gets bent to the will of bad-faith actors.

Entrepreneur Kylo Freeman (they/them) has served various roles in finance since they finished a degree in mathematics in 2010. In 2019, Freeman founded a production company called Boycotted Entertainment that focused on underrepresented talent. Two years later, they presumably leveraged a vast sum of venture capital into their latest endeavor, ForThem. That previous entertainment firm has since been left to rot. After producing one award-winning short called “MIA” (irony), Boycott Entertainment seems to have ceased all operations. Its last Instagram post is 2 years agéd and the “Upcoming” section touts as its prospective output next year’s presumably darling film: “Untitled.” Freeman’s Twitter posts begin in 2018 and conspicuously eschew any references to their previous ventures. Instead, we’re left with gems like:

The success of your business is directly linked to your understanding of your customer… and therefore yourself. Find out who you are. #foundertherapy.

It’s telling that in place of what some might expect as a good faith entrepreneur’s yearslong effort at raising up the voices of the dispossessed in the film industry, Boycott was not just hastily abandoned but kicked to the curb, all because it’s more lucrative to sell nylon binders. Good faith entrepreneur is an oxymoron.

Froufrou ‘self-care’ discourses, while intended to affirm an ethos of radical self-sufficiency, personal agency, and individual recovery are often abused, as in the case of #foundertherapy. All of my gay-people friends opt for non-carceral and non-institutional means of conflict mediation in an effort to hone the tenets of transformative justice. This means that situations both mediative and casual become a circlejerk of therapy-speak. The echo chamber writes the narrative that this in-lan-

ARTS * THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT 13

( TEXT KIAN BRAULIK DESIGN TANYA QU ILLUSTRATION MINGJIA LI )

guage is a queer thing, rather than a set of specific discourses rooted in a medical setting. Its co-optation by the tenderqueers of the world merely adds insult to injury. Therapy-speak, as a relatively novel ‘queer thing’ apparates into boardrooms hankering for the next best way to monetize chestwear and finds its way into mission statements like “we believe there’s nothing more uplifting, brazen, playful, or freeing than human beings breaking shit apart.” I have a hard time believing that Freeman practices radical brick-throwing after their sessions on the #foundercouch. Instead of threatening the ruling-class, tenderqueer aesthetics service Freeman’s enterprise selling gay data up the corporate food chain, putting at risk the very “underrepresented” demographic they claim to represent. +++

In his 1994 book Homographesis, critical theorist Lee Edelman describes the way that gay people come to bear the semiotic weight of cultural assimilation into a more legible, and therefore palatable gayness.

As soon as homosexuality is localized, and consequently can be read within the social landscape, it becomes subject to a metonymic dispersal that allows it to be read into almost anything.

Once queerness becomes a matter of identification—of being gay, or lesbian, or transsexual—it carries the burden of its own troping. Edelman takes his illustrative example of this phenomenon from James Baldwin’s Another Country

How could Eric have known that his fantasies, however unreadable they were for him, were inscribed in every one of his gestures, were betrayed in every inflection of his voice, and lived in his eyes with all the brilliance and beauty and terror of desire.

Everything from movements of the fingers to exhalations from the throat come to encode gayness. But whereas, for Baldwin, an effeminate voice or exuberant gesture plummet his Eric into otherness, the contemporary situation spells a more multifaceted and often nefarious codescape whereby it is not only bodies that suggest stereotypes but stereotypes which inform embodiment (see, the gender-tracking app).

Jean Baudrillard maps this distinctly postmodern move—from material to discursive to discursive to material—with the example of the Gulf War. In lieu of the commonly-held assumption that there is a “logical progression from virtual to actual” phenomena, he argues that the “virtual has definitively overtaken the actual.” One of Baudrillard’s examples is the virtual apocalypse inaugurated by the Cold War, which won’t definitively result in nuclear destruction, but which instead instills an insistent cycle of deferred suffering through proxy violence and cycles of economic instability, like in Syria or Ukraine today. The battlefield of tenderqueer liberation is primarily virtual or representational, the political horizon ceded to PRIDE2023 discount codes and algorithmic niches. These primarily symbolic goals which service hetero-scrutability distract from meaningful political action toward housing and healthcare access, police abolition, and ending gender-based harm. Once the gay subject becomes nothing but an other in a set of proper options—hetero- or homo- or pan- or a-sexual—so they become the subject of free-floating meanings and monetizations. In our pursuit of the trappings of social acceptance, we’ve eaten up the oppressor’s disingenuous co-optation of our signifiers, for no less than $36.40.

Tenderqueers tend to cluster around a specific set of sterilized queer geographies defined solely by a singular shared identity—from on-campus safe spaces to online forums. But what payoff do we get from prioritizing community simply for community’s sake? In his essay “Gay Betrayals,” early critic of gay assimilation Leo Bersani states that “identity is communitarian” and that ‘community’ in today’s milieu is often grounded in unsettled terror and paranoia. Questions abound as to who belongs and who doesn’t at the gates of our most prestigious institutions, the club and the co-op. Decades later, in his memoir about public queerness, Gay Bar, Jeremy Atheron Lin qualifies Bersani’s adage.

We hear the word community all the time. Often it sounds like wishful thinking. Queer community is just as vague—just piling a confusing identity onto an elusive concept. Maybe community […] excludes inherently.

ForThem represents the nth degree of the inherently exclusionary community, as access to its services requires not just surmounting a paywall but opting into the risk of surveillance. Still, it’s hard to envision a ‘queer community’ writ large as anything other than hostile. Gay people collect in increasingly institutionally mediated environments like university safe spaces, zinefests, select daytime eateries, a gay bar if you’re fortunate, and dyke bar if you’re born under only the luckiest star, and while these spaces uphold a host of exclusionary practices (sometimes strict, other times loose), with borders that are now easily diffusible by straight people and generally desexualized expectations. Even the gayest of gay bars tend to now lack a strong enough bouncer to sufficiently homosexualize the space. Lin writes effusively about the San Francisco bar Twin Peaks, which underwent a process of desexualization in order to “promote a wholesome, agreeable gay identity.” There’s this prominent gay club in my city that’s become a rite of passage for our town’s college freshmen. It’s come to host more eighteen-year-old girls than gay adults and oozes a completely sexless energy. There, tenderqueerness names a community defined by aphoristic allyship and prismatic wardrobes, not resistance to systemic violence meted out against ‘deviant’ bodies and ‘perverted’ sex acts. Quashing the id—the true axis of queer repression—in favor of drag brunches with dollar-waving straight girls isn’t compatible with liberation.

bar. In the era of corporate ubiquity and #foundertherapy, ‘community’ is no longer a felicitous heuristic for conceptualizing gay liberation.

+++

Rethinking gay liberation might not primarily constitute a process of legible togetherness— arms linked, ready for our zine workshop—but the rejection of belonging altogether. Tenderqueer’s derogatory use suggests that unbelonging can be auspicious, or even attractively intense. There’s a deviant, enlightened pleasure in being in on the joke, gay in practice as well as theory; as such, the term stakes its own politicized claim that refolds the boundaries of a larger ‘community.’ Lin says, about his longing for the good old days:

Gays can relax in a gay bar, people will say, but I went out for the tension in the room. I miss, more than any notion of community, the orbiting.

Gender-tracking and pay-to-enter ‘communities’ don’t liberate, they streamline. Transness becomes a process with a cohesive narrative and checkable items, things like social transition, name change, hormones, and surgeries. Orbiting names a process of push-and-pull energies that unify and disjoin through engagements in uneven but immutable anarchy. By figuring solidarity this way—the idea of going out in search of the unfamiliar, the sordid, and the disorienting, rather than for a fixed crowd or community—orbiting foregrounds a togetherness for otherness, rather than community for the self, self-care, or even “wellness.” Gay Bar the memoir and gay bars writ large remember an identifiable battleground for the sexual orbits that are fading slowly from the urban landscape. It’s nothing new that rediscovery and nostalgia incite a politics of desire, but in an economic landscape like ours, these bars will not reopen en masse any time soon. That loss forces us to think about our solidarity outside of (and maybe without) constitutively queer spaces—to instead braid our own threads of mutuality from scratch. For me that means how-do-I-get-hormones coffee and brattily allowing my nascent lesbians to sleep together in my bed and sprawling out on the hardwood in a recovery effort from a dyke-break blue period. Yet, interpersonal relationships do not remotely suffice when fighting a losing game, and radical change requires networks of localized activity, mutual aid, and incendiary action. We must orient our seemingly atomized, dyadic connections towards material politics. These efforts should serve not only to promote accountability to one’s local environment but to also strengthen one’s intimate engagements with friends and lovers.

Lin’s memoir doesn’t ask for its audience to have faith in the sudden reconstitution of his prized adolescent haunts but instead lapses into an unexpected acquiescence to the self-admitted virtues of his younger peers. Plagued by his own untethering in the age of the safe space, he concedes a platitude to the next generation:

The idea of safe space isn’t coherent to me, but then again I now recognize that I’m privileged in ways I didn’t previously comprehend. The kids have told me.

Unable to stymie the unanswerable tendencies of kids these days, Lin isn’t belligerent or trusting, but exhausted. A ticking clock, hand on the eleventh hour, looms above the ceilings of the gay

In a world of relative gay legibility, weaponizing provocative labels can undermine the ever-enclosing pressure to assimilate. When conflict in a beloved graphic novel series like Alice Oseman’s Heartstopper centers around the unfurling of gay scrutability–“he’s probably straight anyway” launching the first romantic conflict—Generation Alpha is first to inherit tender hegemony. Optimistically, I doubt that the market will shake out in ForThem’s favor because its opposite, work like Lin’s, isn’t just propelled by nostalgia, but anger. It’s no longer beneficial to find go-to places to locate queer solidarity, yet as connection becomes more and more inaccessible, the tension between gay revolutionaries and assimilationists only burns hotter and hotter. When, I wonder, will tenderqueer become a foregone aesthetic? It’s high time to reject acceptability in favor of disruption, mixture for melee. To build networks founded on presentist care and conscious organizing. Not labels. Not color schemes.

ARTS 14 VOLUME 47 ISSUE 02

+++

KIAN BRAULIK B’24.5, directed by the Wachowski sisters.

“Today, it is not just that certain bodies suggest stereotypes but that certain stereotypes will inform embodiment.”

Over Easy Choices

Planning in an age of cryopreservation

→ I have never imagined myself pregnant. I want to have kids, but the gap between here and there has always felt invisible and blurred. I would like to have the kids there in front of me, actualized and drooling, but the process of creation I could do without.

So I was surprised by my reaction when my cousin told me she was considering law firms based on whether they included egg-freezing and in-vitro fertilization (IVF) as healthcare benefits. For the first time, I could see myself pregnant. Hyper-pregnant. I was wearing a white dress, with long hair I don’t have, sitting in a meadow surrounded by flowers and butterflies. My stomach was almost comically large. And my eyes were wide open, staring down at a belly that seemed to signify the marriage between Nature and Purpose.

As much as watching live births disgusted me, this whimsical image disgusted me more. Pregnancy, so long abstracted from my conception, never felt inherently natural to me. I associated it with wires and ultrasounds, hospitals and modern medicine. The idea of a natural pregnancy had not only felt like a fiction but also a way to entrap people into a God-given motherhood ideal. I have always been against any conception of reproduction that placed normative standards on the people who reproduced, whether on their gender, method of reproduction, or their willingness to reproduce at all. I have, like many people in my generation, been raised under the banner of choice. And choice includes the option to deny nature, to refuse its processes. Championing the choice to refuse pregnancy also meant supporting the choice to become pregnant in any form. The codification of alternative reproductive options into healthcare benefits should have felt like a win—a way out of nature’s impossible bind. Why, then, did I feel like we were all losing?

+++

“Baby now or baby never?” my roommate asks me after I complain about a baby crying outside. Would you rather have a child right now or forgo the possibility of having children altogether? I almost always say never, as do most of my friends. We grew up under the assumption that children were something we could choose to have when we wanted, when “the time was right.” For us—people with the funds and resources to plan out our futures in such a way—life could be broken up into yearslong segments where things were