Lola Simon

03THIS WEEK IN ECLIPSE

Cecilia Barron & Yoni Weil

Joshua Koolik

Lola Simon

03THIS WEEK IN ECLIPSE

Cecilia Barron & Yoni Weil

Joshua Koolik

MANAGING EDITORS

Angela Lian

Arman Deendar

Kolya Shields

WEEK IN REVIEW

Cecilia Barron

Yoni Weil

ARTS

George Nickoll

Linnea Hult

EPHEMERA

Colin Orihuela

Quinn Erickson

FEATURES

Luca Suarez

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Plum Luard

LITERARY

Jane Wang

Madeline Canfield

METRO

DESIGN EDITORS

Andrew Liu

Ollantay Avila

Ash Ma

COVER COORDINATORS

Julia Cheng

Sylvie Bartusek

STAFF WRITERS

Abani Neferkara

Aboud Ashhab

Angela Qian

Caleb Stutman-Shaw

Charlie Medeiros

Charlinda Banks

Corinne Leong

Coby Mulliken

David Felipe

Emily Mansfield

Emily Vesper

Gabrielle Yuan

Jenny Hu

Kalie Minor

Kayla Morrison

Lucia Kan-Sperling

Maya Avelino

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Izzy Roth-Dishy

Julia Cheng

DESIGNERS

Anahis Luna

Eiffel Sunga

Jolin Chen

Kay Kim

Minah Kim

Nada (Neat) Rodanant

Nor Wu

Rachel Shin

Riley Cruzcosa

Ritvik Bhadury

Sejal Gupta

Simon Yang

Tanya Qu

Yuexiao Yang

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Lucy Pham

ILLUSTRATORS

Abby Berwick

Aidan Choi

Alena Zhang

Angela Xu

Martina Herman & James Langan

Sam Stewart

Georgia Turman

Abani Neferkara 10THE

Riley Gramley 12TO

Audrey He 13ACROSS

Emilie Guan

Keelin Gaughan & Ashton Higgins

Evan McHenry

Solveig Asplund 20BULLETIN

Emilie Guan & RL Wheeler

Self-Help Books I Wish Existed:

How to Concern Yourself With Greater Things

How to Disassociate from Meaning

How to Surpass Self-Help

How to Aufhebung

How to Formalize Foreplay

How to Love Your Oppressor

How to Treat Your Grandfather as a Child

How to Make Money from Art

How to Turn Without Re-Turning

How to Love Your Diagnosis

How to Manage-Edit the Indy -K

Ashton Higgins

Keelin Gaughan

Sofia Barnett

SCIENCE + TECH

Christina Peng

Daniel Zheng

Jolie Barnard

WORLD

James Langan

Tanvi Anand

X

Claire Chasse

Joshua Koolik

Lola Simon

DEAR INDY

Solveig Asplund

SCHEMA

Lucas Galarza

Sam Stewart

BULLETIN BOARD

Emilie Guan

RL Wheeler

DEVELOPMENT TEAM

Audrey He

Avery Liu

Yunan (Olivia) He

*Our Beloved Staff

Martina Herman

Nadia Mazonson

Nan/Jack Dickerson

Naomi Nesmith

Nora Mathews

Riley Gramley

Riyana Srihari

Saraphina Forman

Yunan (Olivia) He

COPY EDITORS / FACT-CHECKERS

Anji Friedbauer

Audrey He

Avery Liu

Ayla Tosun

Becca Martin-Welp

Ilan Brusso

Lila Rosen

Naile Ozpolat

Samantha Ho

Yuna Shprecher

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Eurie Seo

Jolie Barnard

Nat Mitchell

Yuna Shprecher

FINANCIAL COORDINATOR

Simon Yang

Anna Fischler

Avery Li

Catie Witherwax

Cindy Liu

Ellie Lin

Greer Nakadegawa-Lee

Luca Suarez

Luna Tobar

Meri Sanders

Mingjia Li

Muzi Xu

Nan/Jack Dickerson

Jessica Ruan

Julianne Ho

Ren Long

Ru Kachko

Sofia Schreiber

Sylvie Bartusek

COPY CHIEF

Ben Flaumenhaft

WEB DESIGNERS

Eleanor Park

Lucy Pham

Mai-Anh Nguyen

Na Nguyen

SENIOR EDITORS

Angela Qian

Corinne Leong

Charlie Medeiros

Isaac McKenna

Jane Wang

Lily Seltz

Lucia Kan-Sperling

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and self-critical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

( TEXT CECILIA BARRON & YONI WEIL

DESIGN SEJAL GUPTA ILLUSTRATION JULIA RUAN )

c It’s that time of the decade! Eclipse time. We know that watching the sun get absolutely bodied by the moon can be overwhelming for some. To help you cope with eclipse-induced anxiety, we’ve compiled eight lists to cover any and every eclipse concern and question you might have.

What to bring to an eclipse

- A great attitude!

- A husband

Who to bring to an eclipse

- People who hate the sun

- Your favorite Brown administrator

- Quirked-up white boy

- Gullible friend (to convince them you’re God)

- Stoner friend

- Idiot friend

- Poet

- ASMRtist

How to avoid eclipse fatigue The strength to admit that you’re at capacity Setting boundaries with yourself Coffee

Accepting that sometimes the sun and moon fight and they will get past it

How to profit off of the eclipse

- Dropshipping

- Selling tickets

- GoFundMe to get this promisin student within the path of totality

- Committing insurance fraud

- Hawking fried pickles

- Busking with moon-based material

- Shorting sunlight stocks

How to stage a breakup over the eclipse - I have personal stuff going on - I’m dealing with eclipse burnout

- Werewolves

- Vampires (for battle purposes)

- Plenty of napkins

- A little drool, for the napkins

- Shock collar

- Two forms of ID

- Blue light glasses

- A bitter herb

- Sketchbook

- Telescope

- I slept with your best friend because of the eclipse

- The eclipse is making me want to be a bad partner

- I’ve realized you’ve stolen my shine

- I’ve realized I’ve dulled your sparkle

- Write breakup message on the inside of their glasses

Things that need to be eclipsed

- War (by Peace)

- IBS (by a more definitive diagnosis)

- Polarization (by a recognition of the Whole)

- Gina Raimondo (by your favorite barista)

- Regret (by hope for the future)

- Popeyes chicken sandwich (by my mouth!)

Words that sound like eclipse

- E-clips

- Lips

- Tri-tips

- Crisps

- Greek trips

- Eclair

c Savia

Crece en ella una nube de polvo, una urna que por su boca se abre.

Él se acerca y se deleita en la posibilidad infinita de observar.

Ella da vueltas alrededor de una válvula a presión, se arrodilla al sol acercándose a los dioses.

La danza frena. Está allí, de espaldas, con los ojos cerrados.

Teme, espera que la estructura de su pelvis se derrumbe, que los recovecos de sus huesos la traicionen.

Su sangre la recorre. Es un río en el que querría nadar y sumergirse.

Explora la temperatura del aliento en su cartílago, murmura en la intimidad de su boca una respuesta.

Ya conoce lo inútil del intento. Trepa las copas de los árboles, apenas roza lo que se le escapa.

Él habla en gestos, en figuras: busca una expresión indeleble para su reflejo.

Ella reza. Escucha.

Revuelve una corriente en el espacio, siente al universo expandirse dentro de sus costillas mientras cae.

Incorpora el ritmo de su boca en su propia boca, la pronunciación errada de las letras.

Se mira las manos. Traduce la savia de una lengua extranjera.

Implora que el tornado que se avecina la haga añicos para siempre.

c Vitality

Inside her grows a cloud of dust, an urn that opens through her mouth.

He moves closer and basks in the infinity of observation.

She goes around a pressure valve, kneels to the sun approaching the gods.

The dance stops. She’s there: back turned, eyes closed.

She fears, waits for the structure of her pelvis to shatter, for the nooks of her bones to betray her.

Her blood runs through her, a river she yearns to swim, to immerse herself in.

She explores the temperature of the breath in her cartilage, murmurs in the intimacy of her mouth an answer.

She knows the futility of her attempt, climbs to the top of the trees, just grazing what escapes her.

He speaks in gestures, in figures; he searches for an indelible expression for his reflection.

She prays. Listens.

She stirs a current in the air, feels the universe expand inside her ribs as she falls.

She incorporates the rhythm of his mouth in her mouth, the mistaken pronunciation of letters.

She looks at her hands. Translates the vitality of a foreign tongue.

Implores that the coming tornado tears her apart forever.

c Nombre

No quiero saber tu nombre, susurrame otras cosas al oído. No quiero saber tu genealogía, tus hábitos de hombre de mundo.

Hablame del trajín del cielo, de las implicancias del calor de una rueda, de cuánto pesa la saliva de un pájaro.

Prefiero escucharte callada, con la mirada mentirosa de un gato doméstico. Prefiero el brillo del trofeo en la vitrina.

Yo también conozco el ritmo de la danza, la aerodinámica de la caída.

Hablame como en un monólogo.

No hay punto final que nos libere del megáfono de los susurros:

c Dance

I don’t want to know your name, whisper other things in my ear.

I don’t want to know your genealogy, your habits as a man of the world.

Tell me about the hubbub of the skies, the effect of heat on a wheel, the weight of a bird’s saliva.

I prefer to listen to you silently, with the lying look of a domestic cat. I prefer the gleam of the trophy in the display case.

I, too, know the rhythm of dancing, the aerodynamics of the fall.

Speak to me like a monologue.

There is no full stop that frees us from the megaphone of whispers: headwinds and tailwinds, recited with eyes shut.

MARTINA HERMAN B’26 is swimming. (JAMES LANGAN B’24 está nadando.)

( TEXT MARTINA HERMAN & JAMES LANGAN DESIGN TANYA QU ILLUSTRATION JESSICA RUAN )

( TEXT SAM STEWART DESIGN SAM STEWART )

Nobody on the Indy knows how our website works (I just asked, like, four Indy people about it to make sure). theindy.org’s biggest mystery has to be its sponsored content, which an ignorant visitor to the site might label “clickbait.” In an effort to make sense of these cryptic advertisements, I’ve organized them the only way I know how: along the axes of Sexless-Horny and Animals-People.

Think something is labeled too Horny? Not Animals enough? Direct all hate mail to lucas_galarza@brown.edu.

SAM STEWART B’24 Removes Pet Stains Instantly

( TEXT GEORGIA TURMAN

DESIGN KAY KIM

ILLUSTRATION JESSICA RUAN )

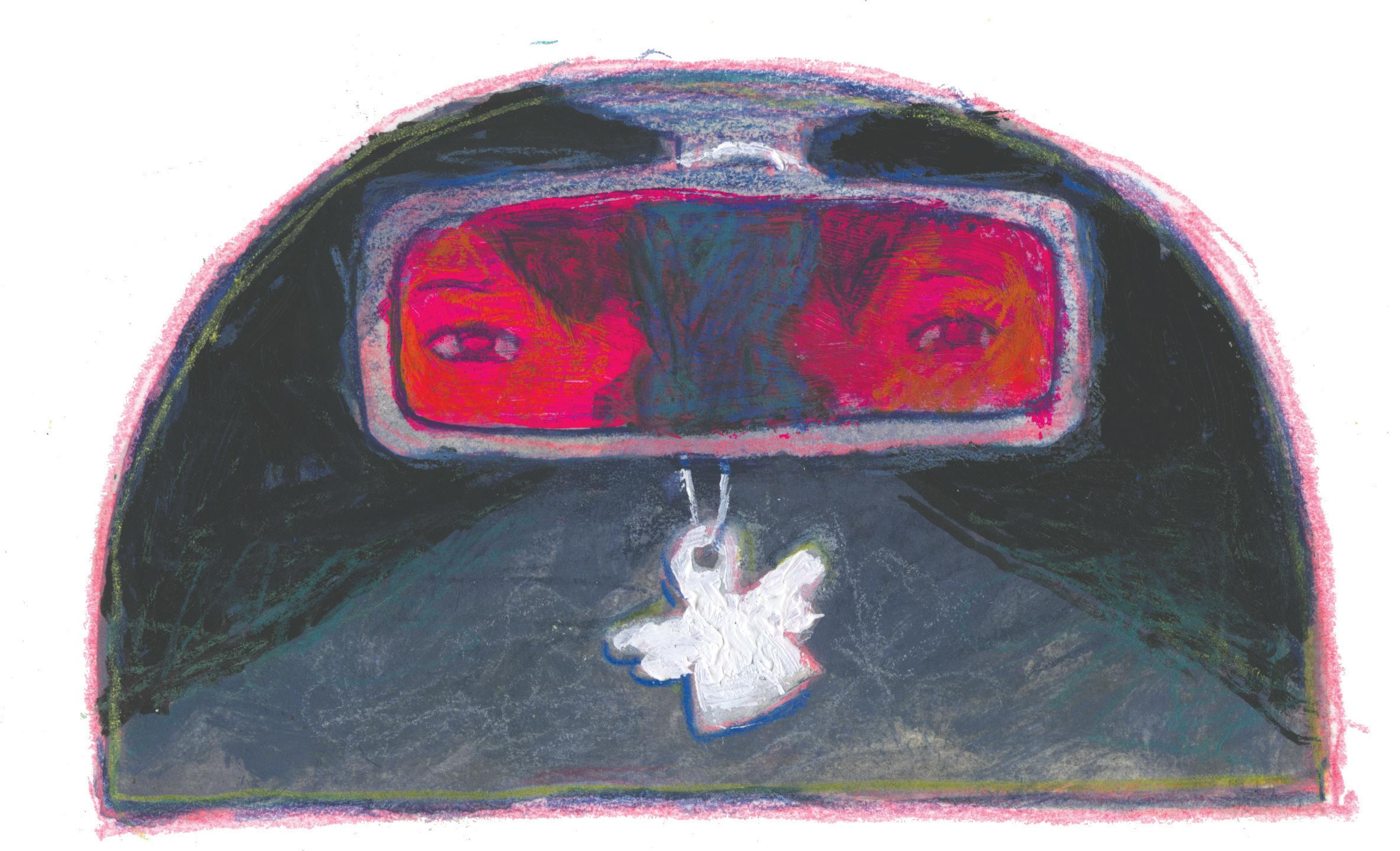

c What we set out to do was see an angel. It seemed like a good night for it—clear, dark. We didn’t have any homework to do and there was gas in the car. I’d been holed up in the house all day stuck in one of those helpless moods, singing at the hands around my heart to sit still, please, sit still. An angel, why not. I guess it was my idea really, to go looking for the angel. You just wanted to go for a drive.

You drove and I sat in the passenger seat. You didn’t bring binoculars? you asked me when I buckled in empty-handed. I shook my head. How do you think we’re going to see the angel, then? you poked. It seemed like you were making fun of me. You pulled out of the driveway and onto the flat, endless street. You put your blinker on.

The whole point is that they reveal themselves to you, I huffed. Then why do we have to go looking for one? you asked. I struggled to explain it exactly, and it made me emotional. I wasn’t sure you were the right person to come on this journey with me. I looked at you, through you, tears in my throat. I’m sorry, you apologized, seeming sincere.

So what do you think it’s going to look like? you continued. You were thinking too much about it. I explained the basics, which I’d learned on Reddit. That they glowed, and their bodies were covered in

eyes, and they were in the shape of rings or covered in uncountable feathers. And that they could take many forms, or that maybe that every description of them was a metaphor. That maybe I was looking for a metaphor.

We argued over the car radio; you wanted to listen to the jazz station and I wanted silence. Silence won out, and you hummed to yourself quietly.

A couple miles down the road you were hungry and I had to pee, so we stopped at a gas station. You bought trail mix and chunk light tuna. In the bathroom, as I hovered over the toilet, I read the notes and names on the walls. The whir of the fan echoed down the room like a chorus of voices. I felt holy. I flushed. I wasn’t hungry, but I bought a plastic-wrapped slice of angel food cake on my way out and put it in the glove compartment, so you wouldn’t see.

Let’s drive to the coast, I said. You got on a different highway and headed toward the water. The whole car smelled like fish by the time we could see the ocean, but I didn’t complain, because I was grateful to you for driving me.

We had been driving for a while when we came across a big ball of rotating light hovering over the water. A beam swept over us, the car, engulfed us, became us, everything was light, and then it disappeared, like an idea. Then it was very dark. The ball of light pulsed us in and out of being.

This has gotta be our angel, you said. No, I said, it’s just a lighthouse. We kept driving.

Are you sure that you’re not an angel? you asked me. Why, I said, because I’m pale and strong? No, you said, because you’re beautiful and I love you.

We kept driving up the coast, past the ball of light and farther and farther away from the wide, empty

streets where we lived. It was so dark, I realized. So very dark, I couldn’t see the lines on the side of the road. I couldn’t even remember your name. Were you my mother or my child? There are no streetlights on the Atlantic, I said, to which you did not respond. The darkness intensified, leaked through the cracks of the car. It went from juice to sauce. It got inside our skin and disappeared us until we were just little fluorescent worms wiggling around in black sauce together. No car, no nothing. This is pretty neat, I said, except I couldn’t say anything because I had no mouth. But I had the feeling that you could hear me, because I heard you. I heard you saying that you felt really good, that you were suddenly hitting life at the perfect angle, that the angle itself was blessed.1

GEORGIA TURMAN B’26 is a serious girl.

c The small map scrawled on the back of the business card led me down winding back roads in the old part of town. Each alleyway split and branched into three or five more at seemingly random intervals, drawing me further into the evening as I wandered down the hill at the card’s behest. In the distance, the sea shimmered beneath the low-hanging blaze of almost sunset. Periodically, I stopped to remove my glasses and wipe the gathering sweat from my brow as I watched its slow descent. Eventually, the buildings cast in bronze by the deep yellow light gave way to the bar situated at the center of the map’s 2D world.

I’m not proud of the way this impromptu expedition began. L and I didn’t usually fight. Of course, we would have challenging moments, little annoyances that sprouted into heated debates or icy remarks. But as each new one budded, they could be manageably cut down with patience as averted eyes met and softer words filled the space between us. We could both own up to when we had said or done something wrong. I liked that about us. Eventually, the fight would blow over, a gentle smile or some dumb joke, like a wave that washes away a line drawn in the sand. This fight felt different though, even before it happened. Sometimes, I think conflicts between two people are so inevitable that they develop into an entity all their own. This imperceptible yet ever-present mass hangs in the stale air, swelling with each passing hour until it becomes enormous enough that it develops a gravitational field, pulling the two unwitting participants into its orbit, so they spiral too fast, pass through the atmosphere, and crash headfirst into the ensuing dispute.

Some choice words, cheap digs, and a shouting match later, I found myself beyond the apartment door. With a head still hazy from anger that bubbled, and eager to cut some distance between her and me, I fished the business card/map from my pocket. It had come into my possession earlier that day when the seed of our fight was still germinating high in the air above us. I had first spotted the stranger who slipped the card from his hand to mine as he watched us loading groceries into the car. Thick, prismatic lenses adorned an otherwise unnoteworthy face, possibly distorting his view more than correcting it. Once he had crossed from his side of the parking lot to ours, he paused and seemed to consider the space around us. For a moment I thought I saw his chin tilt up, and I wondered if he could perceive the fine hairs developing on the ink-black fruit pit that had grown to the size of a bowling ball and sunk a few inches closer to the ground. L, paying no mind to my discomfort, continued to shuttle consumables from cart to trunk as the stranger finalized his assessment and produced the card, despite my obvious reluctance to receive it. The transfer was accompanied by a brief invitation to ‘take a load off,’ and an alert to the 5% discount on drinks happening this week. As I slid into the passenger seat, I murmured to L that 5% seemed low for a discount and the man somewhat odd, but I think my words couldn’t quite pass through the new tangle of growth sprouting from that core nestling between us. All this is to say, I now get the sense the stranger could, in fact, perceive that obscured root-wrapped thing because when I stepped through the tiny door into the bar, I was greeted by a menagerie of patrons accompanied by their own winding knots of various dimensions and morphologies above their heads.

The dim light, cigarette haze, and opaque masses that filled the air obscured my vision of the bartender,

who stood rigid alongside rows of taps and bottles. I took a seat, spurring him to life, at which point he began, with rehearsed efficiency, to retrieve ingredients and assemble them into the drink I had intended to order. I received the drink and inquired into how he had predicted my order. I could have sworn he was looking past me entirely when he shrugged and returned to his previous post. Although this was odd, I was happy to sip my discounted drink and keep to myself as the bar’s atmosphere washed over me, pushed and pulled by the messy constellation of fruiting bodies overhead.

I stayed this way for a while, sipping and letting my mind wander, unaware and uncaring of the slow comings and goings of my fellow customers. This daze was abruptly interrupted when a woman bumped her shoulder against mine as she took the adjacent stool, something I cannot help but think was intentional, given how she so fluidly turned a normally brief apology into the beginning of a conversation. Aurora, as she would eventually introduce herself, seemed to be the only one in there without a shrouded clump tethered to her, or at least she had one that was imperceptible to me. She immediately began providing details on her life and asking for ones about mine. She hated her job and loved foraging for mushrooms, lamented the fact she had panicked and chosen to major in English when she was much better suited to being an ecologist and did I know that plants and mushrooms can communicate with one another through mycelia? No, not really, I answered, with some enthusiasm to avoid more questions about myself, which successfully prompted a conversation more focused on toadstools and slime mold than our personal lives.

We spent some time like this, Aurora expounding on ecological wonders, primarily fungi, and I giving enough of a response to encourage her to produce the next factoid. It was easy to move through the night this way, and I didn’t have to think about coming home to L or about the persistent mass behind my right shoulder, swathing itself in greedy capillaries, around and around, carving the surface of a planet. However, we eventually arrived at a lull in the conversation, and after it stretched to the point where we were forced to make a sort of questioning eye contact, she asked if I wanted to go somewhere else. I thought about mentioning L, or at least indicating my relationship status with some nonspecific remark, but something about the now sleepy churn of guests at the bar made the impatient expectation

in her eyes feel like an invitation I wouldn’t have the willpower to refuse.

After closing out with the bartender, who had only become slightly more distinct from the bar itself, we took our coats from the rack by the door and emerged into the cool alley, loyal thing at my back. As we made our way further down the hill toward the night sky and purple sea, Aurora decided it was time to fill me in on the big picture. I’ve been telling you all these things about fungi and root networks because we are just like them, or more precisely, they’re just like God, and the divine power we’re all looking for isn’t some humanoid deity up in the sky, but the imperceptible stuff in between us all, what connects us. I told her I didn’t really believe in God, and that the network she described was hard for me to picture anyway, but she was convinced I would come to understand her great theory. It’s not about believing, she fired back, it’s about how we as humans are inextricably bound, that there’s something that weaves us into everyone else whether you choose to believe in it or not. Hmm, I’m sure if I locked myself in a box six feet underground I would feel pretty disconnected, I let slip with a chuckle. L always says this is a bad habit of mine, this reflexive need to interject a dumb joke when I should be listening, when I have nothing else to say. Half the time I feel like she says it out of spite. Regardless, my outburst didn’t derail Aurora, either because it was inaudible or because she chose to ignore it, continuing to outline her grand vision of divinity. Think about it, she mused, it’s like if a bird dropped dead onto the forest floor, only the local fungi would be aware, and yet their expansive mycorrhizal network built through millions of mycelia carries the reverberations of that impact through the entire community. Like some sort of collective trauma? I asked, still thinking about how I could repackage my earlier comedic remark for broader appeal. Good, bad, anything, it’s carried between everyone like power lines, the whole of humanity one living, breathing power grid, and the electricity that slides between is the holy spirit. She smiled at the neat bow she’d placed on her rather eccentric understanding of God and humanity. I, for one, wasn’t convinced, and my small moon, following the two of us, felt less like a vein and more like a blood clot, thick and impenetrable to oxygen or whatever other nutrient was supposedly transmitted across root-mycelia networks. I supposed I had learned something during this exchange. However, I kept my rebuttal to myself as we arrived at the bottom of the hill with the sea stretched wide before us. Its appearance spurred Aurora to run to the end of the esplanade and step up onto the low cobblestone wall dividing the domain of man from oceanic expanse which birthed a new sun at its horizon. There, elevated above the known and the unknown with arms outstretched, the first rays of sunlight cast across the water reached my eyes, and as they passed through the scratched prisms of my glasses, it looked as if she too was housed in a vast network of fungal hyphae that stretched between moss-eaten stones, over rising waves, out into the cosmos and all the way back, manifold and shifting, then slipped past me, in search of something else.

ABANI NEFERKARA B’24 is plucking at the mycorrhizal network.

( TEXT RILEY GRAMLEY

DESIGN ASH MA

ILLUSTRATION ELLIE LIN )

c My first time on the East Coast, for college, I penned, with a reverence, how green the vegetation looked. In southern Oregon I had been used to Augusts that were arid and blonde. It was a striking difference, and a difference, I imagined, determined by the presence and absence of water. And, now, it is a difference I consider every time I draw tap water from the sinks in Grad Center, or brush the tufts of emerald grasses on the quadrangles. It is a difference I consider as I walk beside the Providence River, or fill my Nalgene. It is a difference I have begun taking note of, even if unconsciously, and a difference in scene and specter I am trying to note here.

From the passenger seat, I’m looking out onto the highway’s flanks of bald, dry sod—evidence of controlled burns. The burns run parallel alongside I-5 as its roadway drops into Northern California. My brother and I had just driven down from the Siskiyou Pass, an elevated piece of the Cascade mountain range in southern Oregon that stretches downward before bending east at the top of California. It was a remarkable scene, and a scene I had driven through often: Mt. Shasta, volcanic and inky against the horizon, sits tall on a wide and amber countryside, like a gray fist. Down the rocky faces of the highway is a riverbed, which is small and almost impossible to make out. There is no water, nor current, there. Small trees on the riverbank bend to touch only pebbles and dried mosses. It is clear you’ve entered California. It is clear it is the summer, and that water is a precious resource here.

My brother and I have set out on I-5 to visit a friend in the Bay Area. A pavilion, close to one of the first towns in Northern California, Yreka, stands in a field the color of mustard. “State of Jefferson” reads in large block letters on a white tarp, which is fastened to the roof of the pavilion. Maybe hay was once stacked under the pavilion, but not as we pass it now. The “State of Jefferson” is a secession movement born of settler-colonial populations in the middle 19th century who got wealthy from the gold they found in the Klamath River basin. The settlers then attempted to claim land that was governed over by distant and more populous capital cities in both Oregon and California. Their sentiments remain on land that wasn’t theirs in the first place, land on which the Kahosadi peoples lived. The pavilion’s white tarp still advertises their radical political message. Yet, the Klamath River, which I craned to see, then, down the highway’s rocky walls, had dried. And the fields which were themselves dry, below the pass, looked gold in the hot winds.

Eventually, my brother and I make it to the Bay Area, through the large depressions of land that make up California’s long central valleys. We pass grain factories, cattle, and rice fields. The tin skeletons of industrial farming machinery are a kind of grandeur to rush by. It is often hard to figure out if this place is new or old, if its economy and its agricultural makeup are thriving or depleted. At some point during our visit to the Bay Area, we drove through Sacramento Valley into Stockton. Like Modesto or Sacramento, Stockton is stamped along Highway 99. And accessing Stockton required driving our car from the Bay Area, which descends down, like a concrete arm, through the crescent Central Valley. Heat wicking off the roadway obscures the distance and gives the illusion of spilled water. Highway 99 is lined with innumerable car dealerships and seemingly vacated corporate office buildings. The highway cuts into the landscape before eventually dilating into thin pale glens. Beyond the road, new housing developments are spread out on the flat parts of the landscape. The plots of houses look, at a distance, as if someone had thrown a deck of

cards across Sacramento Valley. The houses look something like those on Madeleine L’Engle’s planet “Camazotz” in A Wrinkle in Time—identical structures lined up in uncannily, inorganic, grids. They are these suburban, rectangular impositions, set against California’s hazy, yellow-saturated horizons. Heading back from Stockton, my brother and I were caught in car-to-car traffic, and a plume of smoke became visible just ahead. It turned out that a car had ignited on fire, and, too, ignited the grasses on the hills just beside it. The fire was extinguished quickly, but the hills still bore the fire’s scars, long brushes of sepia and overturned sod. As we rolled slowly past, firefighters were standing silently on the hills, like little red statues. Aridity here, I was learning, keeps the score.

Warren, Rhode Island is almost entirely surrounded by water—to its south and east are Mt. Hope Bay and Narragansett Bay, which marble into one another as they meet. To Warren’s north is a wide marshy area called Belcher’s Cove, and to its west is the Providence River, which opens into the bay like a cone. The Providence River moves downward to meet Warren, as if unclasping its hands, signing off its prayer. Just beyond Warren and the rest of Rhode Island is the Atlantic Ocean, which, no

doubt, is a kind of specter: it is projected that by the year 2100, much of Warren’s shoreline infrastructure will be permanently enveloped by seawater.

The first thing I smelled when I got to Warren was the sea. It was my job that day to do what I am trying to do now—pay attention to water. I was part of a small team of two professors and one other student researching climate-induced sea level rise and its effects on the Warren community. On my first visit, I walked along Belcher’s Cove and studied each puddle, many blooming with algae that fall. It was hard to tell where the marshland and its pockets of water ended and where they began. I remember the sky that day held several gray clouds that looked like fingers brushing a silver curtain to a rhythm. I think they were threatening rain.

On my first visit to Warren, I walked down Market Street, an area of particular importance to our work because it often experiences severe effects of flooding. Parts of the street that day were stained, as if marsh water had at some earlier point laid stagnant there. Multi-family units were stacked along the street. Many had gravel driveways and yards, which I later learned were built to better absorb flood water and runoff. Market Street acts as a kind of shoreline; the lip of each yard descends into the cove. On stormy or high-tide events the whole street is filled, the cove consuming, insatiably, basements, sidewalks, and yards.

On the occasions that I return to southern Oregon, the first thing I notice are the colors on the hills. Along the bases of the Cascades are several blemished landscapes—rows of moors settle below these mountains. In the spring, when the rains are plenty, the moors are green and dark, and look from a distance as though someone had smashed a thousand green olives on their surfaces. But as the season turns to summer, and the rains leave, and leave for long intervals, as is typical in the southern sprawls of the Cascades, the moors turn flaxen. I have learned that when I see pieces of the moors brighten—patches of green fading to yellow—the rains will not come again for a long while. The moors loom above my backyard and I’ve developed a habit of studying them. I study them more often these days because I impose on them, maybe unfairly and illogically, a presence as if they offer me clues—information that might reveal how devastating the fire and smoke season will be to come. The dryer, the more yellow, I think, the hazier our August should be, the greater chance I’ll sit from my backyard and watch the moors go up in flames, see fires over the hillsides, like rashes fanned across the landscape.

Each summer rain in southern Oregon feels impossible. But, on the rare occasion that it does rain, I’m delighted by each drop—delighted as

it grays the pavement, slightly darkens a collection of orange pine needles, hits the stems of wild starflowers, angling their stocks downward. Last summer, when rain came, astoundingly sometime at the beginning of August, I thought of my favorite poem by Carl Phillips, in which he writes: “...a vast / meadow of silverrod, each stem briefly an / angled argument against despair.”

In Warren, however, petrichor marks a warning.

In her essay “Holy Water,” Joan Didion writes, “Some of us who live in arid parts of the world think about water with a reverence others might find excessive.” Although it might be excessive, I find it a privilege to consider water and its absence, to study the landscape without searching for calculable answers. I don’t aim to compose a climate model, to come up with an actual figure that estimates rainfall accumulation, or snowpack, that tells me how clean my tap water is. I don’t think about water to assign a numerical value to how arid or fertile a landscape really might be. I’m not as interested in these things, although they are often vital measures. I’m more interested in looking, imagining how water colors the landscapes of my own life and others, how water feels when it’s there and when it’s not. I do, however, know that for many people, like those on the shorelines in Warren, it may not feel like a privilege or a luxury to think about water, but rather a mortgage-saving, or perhaps life-saving, necessity.

On a recent visit to Warren, I picked up the Warren Times-Gazette, in a coffee shop. Almost every article was about water—a demolition to begin soon at the Kickemuit Reservoir dams, a 400,000 dollar grant that will restore the coastline at Jamiel’s Park, the same coastline I walked my first time in Warren. I exited the Coffee Depot, the small coffee shop at which I sourced the Gazette, and walked through a neighborhood, a few blocks removed from Jamiel’s Park and Belcher’s Cove. Puddles spotted the street, their edges thawing from thin coverings of ice. The puddles looked like fraying paper. The day was flat and gray-soaked. A rain to come. I noted this on a napkin, my pen ink blurring a little as it ran through a coffee stain.

In her 1967 Saturday Evening Post column, “Points West,” Didion wrote to her readers that “Newport is curiously western.” I’ve yet to visit Newport, but I wonder if I’d find the aridity with which I associate my growing up in Oregon and the West. I wonder if I’d find the yellow moors and the golden grasses. I sort of doubt it—Didion’s holy waters have changed. They ride higher, are absent more often.

RILEY GRAMLEY B’25.5 is delighted by each drop.

cFour years ago, I fell mysteriously ill. I stopped eating. I lost my period. I had bouts of crying, nausea, dizziness. It terrified me, and it worried my mother to the point of panic.

In the months that followed we rushed from appointment to appointment, hospital to hospital. My mother sat on the side of the examination rooms, her brows knit together in worry, watching the doctors examine me, trying to understand what they were saying. I was ordered a variety of diagnostic tests, but nothing came back with conclusive results, and as the months went on, we fell into a cycle that seemed futile and endless. I saw first the general physician who would refer us to a specialist, then the specialist who, after briefly interrogating me, would order a test or medication, then the technicians at the hospital or imaging center who would carry out the tests. At follow-up appointments, we were usually recommended more, different tests or referred to more, different doctors.

I wasn’t getting any better. The multitude of appointments, most lasting shorter than the amount of time it took us to drive there, was draining me. Parts of my body that I had never given much thought to before were isolated, probed, and imaged, and I felt an increasing disconnect, my body belonging less and less to myself, transmuting into a thing the doctors seemed to have a better understanding of, and more control over, than I did. My mother suffered through me. She stopped eating at dinnertime; she said she was too stressed. She began keeping a diary, which turned into a medical log of my appointments, test results, and symptoms: my illness was consuming her life, too.

So when she suggested I try traditional Chinese medicine—like acupuncture and herbal remedies—I agreed.

I wasn’t expecting anything. I thought it was all pseudoscience, but if trying it would ease my mother’s pain, that was enough. Yet the appointments surprised me. The herbal doctor we found was a soft-spoken, middle-aged Chinese woman. She held my hand to lead me to my room, a small and warmly lit space. She asked about my symptoms, but also about school, my friends and family, my day. Though I was terrified of needles, she was so gentle, and during the acupuncture sessions I would always fall asleep. For the first time since falling ill, I felt I was being treated by someone who truly cared about me. Before I left she always told me how brave I was.

I couldn’t reconcile my skepticism about traditional medicine with the emotional results it produced. Surely I couldn’t be cured by some needles placed in my body—but then why did every session make me feel better? Why didn’t my encounters with the Western doctors, whose expertise I actually trusted, do the same? +++

Traditional Chinese medicine, or zhongyi 中医, is a holistic approach to healing, based on the belief that the body is a network of energies through which the forces of qi 气 (breath, or vital life force) and xue 血 (blood) circulate. In the West, it is often called “alternative medicine” or even “pseudoscience,” because there seems to be no scientific basis for its theory and practices. Yet it is a system that has existed for at least 2,200 years. Huangdi neijing 黄帝内经, a foundational text of Chinese medicine, dates to 206 BCE, though acupuncture and herbal remedies were likely already being practiced centuries earlier. Sickness is understood as a blockage of the movement of qi 气 or xue 血, resulting in imbalances of yin 阴 and yang 阳. Acupuncture works to restore harmony through the placement of needles at specific points along the body’s 12 major channels, or meridians, through which qi flows. Each meridian is either yin or yang and corresponds to one of 12 internal organs. In some schools of acupuncture, there are two additional meridians along the centerline of the body: the conception vessel, which controls yin meridians, and the governor vessel, which controls yang meridians.

( TEXT AUDREY HE DESIGN OLLANTAY AVILA ILLUSTRATION MUZI XU )

Though I complained of pain in my head and my stomach, the herbal doctor looked at my eyes and my tongue and felt my pulse on my inner wrist, assessing the strength of my qi, the balance of my energies. The points of my body at which she inserted the needles, as well as the kinds of herbs she prescribed, depended both on what I told her in our conversations and what she learned from her assessments. Needles in my shin targeted the stomach meridian to treat digestive disorders. Needles in the center of my lower abdomen targeted the conception vessel to treat irregular menstruation and exhaustion. Sometimes she put needles along my hairline, on the governor vessel: this targeted mental distress. At the end of the hour, she would come back to remove the needles and massage my body with a fragrant oil.

Modern Western medicine views the body as a mechanized system of parts, and disease as a particular, somatic malfunction of that system. Historically, this is a recent development—the foundations of Western medicine were holistic. The humoral theory Hippocrates formulated associated four bodily fluids with four major temperaments and viewed disease as a state of imbalance of those fluids. Humoral physicians relied both on medical texts and on a personal understanding of the patient to treat this imbalance, for the dissection of human bodies was forbidden by religious taboo. It was only during the 16th and 17th centuries that developments in anatomical dissection, surgery, and microscopy set the stage for the research methods and medical specialization that characterize Western medicine today. The 19th century truly catalyzed this transformation through the emerging forces of modern capitalism, industrialization, and nationstates. Michel Foucault argued for what he called “the medical gaze,” a clinical objectification of the patient by medical practitioners and medical knowledge. In The Birth of the Clinic, he writes that “medical certainty is based not on the completely observed individuality but on the completely scanned multiplicity of individual facts.” The patient on the examination bed is reduced to a body, a landscape to be divided and surveyed for evidence, a problem to be solved.

The doctors I saw ordered CT scans, ultrasounds, MRIs. I got bloodwork done, an endoscopy, even something called a “gastric emptying test,” where at the hospital I ate a cup of radioactive oatmeal and every hour laid down so that an X-ray image could be taken of my stomach, to trace the progression of the food. These were needed in order to rule out possible diagnoses, I knew that. But they necessitated an understanding of my body as simply an amalgamation of parts, a machine which was now malfunctioning, and in their mechanical probing and scanning they contributed to my alienation and distress. My sickness blended both mental and physical pain, and there seemed to be no doctor who could understand it entirely. I was told it could just be “psychosomatic,” a term that refers to symptoms that have no clear physical causes and therefore are thought to be psychological in origin, but which most people, myself included, interpret as a dismissal. Maybe, they seemed to suggest, it was all in my head. I was recommended a psychiatrist.

The specialization of Western medicine also transfers the care of the patient into the exclusive hands of medical professionals. Informal networks of care—one’s family, relatives, friends—find themselves displaced. When I went to get my tests done at the imaging centers, my mother was rarely allowed to come in with me. Usually, she would be confined to the waiting room while I was led down the hallway into the dark room, outfitted with screens and sleek machines. Even when she was in the room with me, there was little she could contribute aside from asking nervous questions and providing the insurance information. I disliked her coming with me to my appointments because I felt embarrassed by her questions, the childishness of her ignorance. But why? She would ask. The doctor’s answer was never satisfactory, and she would follow-up with the same question: but why? I could tell when the doctor was getting annoyed; their answers would get more curt, more simplified, sometimes they would end it themselves. Sorry, I have a lot of patients today, I really don’t have the time. And I could see, still, my mother frustrated with the gaps in her knowledge, the obstacles to her understanding. There were nights she did not sleep because she was ‘

做研究,’ as she told me. Doing research. How could I tell her that she didn’t have to understand anything; that’s what all these doctors were for? That there was nothing she could do for me? That she couldn’t take care of me anymore?

Yet when I started seeing the Chinese doctor, things changed. My mother had to pick up packets of herbal medicine weekly. Every morning she opened a new packet, poured its contents into a pot, and slowly heated it to a simmer. She would bring the drink to me midday as I sat at the kitchen table, as if it were coffee, and watch as I drank it with my nose pinched. Traditional Chinese medicine considers a patient’s social environment as a key part of treatment, acknowledging the interconnectedness of the well-being of both patient and caregiver. My mother’s role as caregiver, as mother, was restored, and she got better.

Even now I can’t say whether all those hours spent lying in that room with needles in my body, all those cups of hot bitter brew I gulped down, truly

helped me recover. But I do believe that the care and connection afforded to me through those appointments came at a time when I really, really needed it. I left every session feeling permeated with a sense of calm, relaxation, and hope. The herbal doctor never told me she didn’t know the answer. 放心,可以治疗, she repeated to my mother and me. Don’t worry. She can be treated.

Maybe traditional Chinese medicine is just a placebo effect, maybe her words were false promises. I don’t know. What I do know is that it felt like kindness, mercy, love. I think it was healing.

AUDREY HE B’27 is still afraid of needles.

cI go downstairs because of the burning smell. My grandmother stands in the kitchen, stirring something on the stove. She’s burning orange peels for her cough, my dad explains, face pinched in dismissal. Does it work? I wonder.

Ma, hey Ma, does it work? Does it help with the cough, he asks loudly. She cranes her better ear towards us. Does it help, he asks louder. She looks down at the peels on the plate, charred commas wisping into smoke. They’re oranges. Good for the throat. I burn them and the nutrients sink better into the skin. Then I eat them warm, she explains in Mandarin.

Look, I really don’t think that’s how that works, he replies. Quietly, I agreed.

I grew up with a shallow distaste for non-Western medicine and an understanding of how real medicine worked: I drank acid-pink Tylenol from a plastic cup, and it cured me. When I was very young and staying at my grandparents’ place though, I had to cure my colds by gulping isatis root, or ban lan gen, in tiny brown vials.

I’d rather just be sick, I complained to my mom, the bitterness burning down my throat. But really I’d absorbed, in the same way as one does grammar, slowly, unconsciously, that this kind of medicine was superstition, not science. And I knew I didn’t want to swallow that

In every textbook from my biology classes, the history of medicine (in which they always mean modern medicine) jumps from Britain to France, from spontaneous generation to leeching. The late modern medicine in Asia section of the Wikipedia page for “History of Medicine” writes, “Finally, in the 19th century, Western medicine was introduced…” I read it as Finally! Finally, no more witchcraft. Finally, the dying were saved. For the entire page, there is little mention of original medical breakthroughs originating from Asia—only the dissemination of Western ideas outwards, like a superspreader, or a colonizing operation.

Imagining decolonization through histories of traditional medicine

Many non-Western discoveries of health and care go uncredited in the records of medical knowledge and history we accept today. This lack of documentation in both the scientific and public consciousness means that we continue to believe in a medical efficacy that exclusively equates to a Western nucleus of knowledge. Indigenous or traditional knowledges from non-Western countries are automatically devalued as “outside” of science. As anthropological scholar George Jerry Sefa Dei writes,

“I come to…an educational journey replete with experiences of colonial and colonized encounters that left unproblematized what has conventionally been accepted in schools as ‘in/valid knowledge.’ My early educational history was one that least emphasized the achievements of African peoples and their knowledges, both in their own right and for the contributions to academic scholarship on world civilization.”

This perception of non-Western and Indigenous knowledges as invalid forms of global medical scholarship persists.

Around 50 percent of current pharmaceutical products today can be traced to nature and traditional sources of knowledge. The history of drug and cure development, spanning from hundreds of thousands of years to a few decades ago, takes much inspiration from traditional medicine.

As early as 200 BCE, there is evidence of ancient practices of variolation in parts of North Africa and Asia. Around the 16th century, there was evidence of inoculation in places like India and China for smallpox, where material from the sores was administered to healthy people to induce a milder strain of the virus and protect against deadlier encounters from regular viral contraction. Today the smallpox vaccine draws from this principle and is the only human disease to be completely eradicated.

( TEXT EMILIE GUAN DESIGN OLLANTAY AVILA )

Around 1500 BCE, Sumerians used the bark of willow trees for its salicin component and the analgesic and antipyretic effects. Egyptians and Assyrians also discovered willow bark’s therapeutic uses later around 4000 BCE. Today its medical descendant, aspirin, is taken by millions of people every day for pain relief, blood pressure, and stroke prevention.

Dating back to 2600 BCE, Mesopotamian folklore contained records of Madagascar periwinkle being used as a medicinal plant, and it’s also mentioned in traditional Indian and Chinese medicine. Today it’s the source of vinblastine and vincristine, which has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as chemotherapeutic agents in cancer drugs.

In 1971, Tu Youyou and her team at Project 523 isolated artemisinin, which is an active compound in sweet wormwood. For two years, they unsuccessfully tested 240,000 compounds in an effort to search for a malaria treatment. It was when she turned to traditional Chinese medicine texts that they finally found a reference to sweet wormwood being used to treat intermittent fevers around 400 CE. Today it’s the most effective antimalarial drug, and Tu was awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of artemisinin as a first line of defense against malaria.

Traditional texts pressed the sweet wormwood into their pages, and the wormwoods in turn hold profound insight for the rest of the world. To understand that these histories of medicine exist, and can and should inform current medicine practices and research, is a process of decolonizing frameworks of knowledge.

This process is by no means restrained to theory, nor a new political project: Frantz Fanon, an important thinker in post-colonial theory, studied psychiatry in Lyons and was disgusted by the mainstream psychiatric approach, replete with overt anti-Black racism. He found an alternative by studying institutional psychotherapy at a Saint-Alban hospital under François Tosquelles, which sought to humanize psychiatry by questioning the authoritarian and colonial philosophies of the mental health psychiatry of the time. The French word “aliéné” meant alienation but also often referred to mental illness—Tosquelles and his colleagues believed that there was a “doubled alienation” not just reducible to illness. In other words, illness had neurological causes but was also a symptom of societal sickness, where settler colonialism and racism caused intense alienation, especially for the oppressed.

When Fanon began practicing as Chief of Service at Blida Hospital in Algeria, he implemented the principles he learned in Saint-Alban and drastically changed the delivery of care there: minimized restraints, prohibition of “native” and European patient distinctions, and occupational therapy programs for all patients were a few of the changes made. He intended to address the social alienation from colonialism through a philosophy that was radically divergent from mainstream thinking at the time.

If I were to ask many doctors, or skeptical dads, or even myself a year or two ago, traditional medicines remain hard to reconcile with the indisputable science that Western medicine purports to be founded upon.

In his book Philosophy of Medicine, philosopher Alex Broadbent proposes four “bad arguments” for traditional, or alternative, medicine:

1. that they would not persist if they did not work;

2. that they fulfill other needs;

3. that they are effective because they fulfill other needs; and

4. that they are supported by scientific evidence or theory.

He contends that these arguments don’t work to justify the effectiveness of alternative medicine. 1) There are many reasons—social, political, religious— why practices may persist despite efficacy (I’m reminded of the old medical agreement that homosexuality as a ‘disease’ could be treated by hormonal injections). 2) Though they may fulfill a need, this doesn’t defend the claim of them as working cures. 3) Even if alternative medicine may be effective in ways not understood by themselves, this reasoning perhaps speaks more to a psychological operation than the medicine’s proposed mechanisms. 4) Finally, part of what makes alternative medicine, alternative, is a lack of support from mainstream clinical trials. How might we then imagine the role that traditional medicine plays within current medical frameworks, especially for processes of decolonization?

Broadbent first acknowledges that “the relationship between power and knowledge is uncomfortable…knowledge yields power” and shapes the ability to do things that those without knowledge are precluded from. Yet a theory’s truthfulness cannot depend purely on yielding practical power. He cites Newtonian physics as an example—it breaks for the edge cases of objects interacting on a subatomic scale or traveling near the speed of light, yet it has had practical power for physics.

Knowledge also directs power. It may then follow that the decolonization of medical knowledge begins with universal, equal medical access and what Broadbent refers to as epistemic equality. But Broadbent challenges certain aspects of these arguments.

It is no surprise that mainstream medicine accessibility depends on race, class, and gender, with those historically excluded and marginalized facing similar treatment in healthcare systems. Yet a blind push for universal medical provision (without interrogating the canon of knowledge) may exacerbate underlying power dynamics—that Western medicine is superior to traditional Indigenous, or traditional African, or traditional Asian medicine, for example—by determining what medicine is imposingly provided. As Fanon contends in A Dying Colonialism, in a colonial context (such as Algeria during French occupation), consenting and yielding one’s body to a practitioner with one’s best interests in mind wasn’t possible because Algerians understood that the colonial doctor othered the Algerian patient. He echoes his mentor Tosquelles for the doubling of alienation as not just psychic state, but also social condition. Broadbent further explains the material impacts of alienation for healthcare:

“Othering continues: ‘we’ end up deciding what ‘they’ need and what ‘they’ will get, where ‘we’ are the social and political elite, and ‘they’ are the rest, who get our sympathy and our assistance, but who ‘we’ still do not see as equals, even if ‘we’ will not say so.”

Calls for equal access must contend with what access it provides, and who decides it.

When it comes to exercising decolonization through the mode of leveling the epistemic equality of different medical frameworks, Broadbent cautions against sliding into a kind of wholesale medical relativism because it doesn’t actually promote tolerance for differing traditions and viewpoints. In fact, instead of inviting critical thinking and epistemological humility, it throws a blanket statement of “to each their own medicine,” and any medical tradition that disagreed with another would be paradoxically protested. Thus Broadbent argues for “critical decolonization” and evaluating knowledge regardless of canonical or epistemological origin.

What has been considered “mainstream” medicine and practices of care has always been in flux.

The resulting interplay of political power dynamics and medical practices then has a profound impact on health institutions and the material lives and well-being of patients throughout time. The act of “decolonizing medicine” may begin with challenging frameworks of knowledge, but it arguably must be a political act— to avoid turning the movement into metaphor and “moving towards innocence” without dismantling the material artifacts and systems of settler-colonialism. As our understanding of medical knowledge shifts, so must the reality of healthcare implementation—who decides what practices of care are implemented, and the tangible impact on patient lives. +++

A concern that arises from considering this process of decolonizing mainstream medicine through Indigenous medicines is the co-opting of Indigenous cultures and lands into the capitalistic, modern medicine industry. The term “mainstreaming” refers to mainstream medicine’s selective incorporation of traditional medicine, resulting in either a benign or more insidious relationship between the two. A more benign manifestation might be adopting certain traditional practices, but practitioners perhaps not fully understanding or engaging with traditional philosophies. Then there’s the danger of co-opting alternative medicine, which is driven by profit and power. Faced with decreasing control over the industry, biomedicine tries to coerce and buy out alternative medicine in a way that doesn’t value equality or acceptance of co-existence.

This co-option ignores the distinct medical philosophies and epistemologies of different practices of traditional care—it aims to commodify and appropriate alternatives when “integrating” into biomedicine. While there is a need for traditional medicine histories to be brought into more mainstream conversations and research, there is also a danger if done so in ways that perpetuate existing dynamics of extraction and colonialism, thus likely harming Indigenous practitioners and patients. The guiding principle for every “decolonization” movement should be the material impact on Indigenous communities and cultures.

+++

In her Nobel Lecture, Tu Youyou says that she learned four years of modern pharmaceutical sciences and later trained in traditional Chinese medicine at Beijing Medical College. During her antimalarial research, she stumbled upon the line “A Handful of Qinghao Immersed in Two Liters of Water, Wring out the Juice and Drink It All,” and following this phrasing prompted her breakthrough in preserving herbal efficacy. In another paper, she writes that the discovery of artemisinin, or qinghaosu, from sweet wormwood is a “true gift from old Chinese medicine” and hopes that Chinese medicine will continue helping cure diseases worldwide.

The impact and potential for impact that traditional epistemologies around the world have on the current Western archive of medicine needs more discussion and consideration. In addition to specific plants and compounds found in nature, the very frameworks of traditional medicine knowledges emphasize synergistic treatment for more complex diseases and challenge the “1 disease, 1 target, 1 drug” doctrine.

Knowledge yields, directs, and sometimes itself is power. To rule out traditional medicine as “superstition” not only does a disservice to scientific progress but also perpetuates an elitist, hegemonic philosophy of knowledge and a damaging narrative of non-Western equating to primitivity. Understanding traditional medicine’s rich history—the care within sweet wormwoods, and folklore records, and synergistic philosophies—enables us to explore its immense potential in current medicine practices, as well as imagine its decolonizing force within the medical field.

EMILIE GUAN B’26 recommends tiger balm for mosquito bites.

c In June 2023, the Supreme Court, in a 6-3 majority, decided that Harvard University and the University of North Carolina’s admissions programs were unconstitutional, ending race-conscious admissions at U.S. colleges and universities. Consequently, universities across the country have spent the last nine months scrambling to figure out how to eliminate explicit considerations of race from their admissions processes while maintaining racial diversity on their campuses.

But, the termination of affirmative action is not the only force hindering equitable admissions at elite universities like Brown—the continued consideration of “legacy” status (or an applicant having an alumnus of the same institution in their family) further prevents historically underrepresented communities on college campuses from accessing those educational opportunities in the future. Even before the Court ruled on race-based admissions, schools including Amherst College, MIT, and John Hopkins University had already struck down legacy admissions. Now, even more students across the nation are protesting the dual impact of eliminating affirmative action and maintaining legacy admissions on racial minorities applying to American universities. Brown’s response to such concerns was announced on March 5, 2024, when the Ad Hoc Committee of Admissions Policies announced the results of their months-long, closed-door deliberations.

On March 5, President Christina H. Paxson released an executive summary of recommendations by the Ad Hoc Committee which the University intended to accept. The committee, composed of senior faculty and alumni members of the Brown University Corporation, was appointed in September of last year to examine how to better align Brown’s undergraduate admissions policies with the University’s values of diversity, equity, and inclusion without explicit considerations of race. In an email to the Brown Community from September 6, Paxson wrote, “Brown has a strong track record for national leadership in demonstrating a commitment to building and sustaining a diverse and inclusive campus community.” However, Brown has yet to propose any substantive changes to its admissions policies to fulfill these commitments without affirmative action.

Paxson accepted recommendations including reinstating the requirement for standardized testing scores and upholding existing policies for legacy applicants. Despite the Committee’s stated goal of charting a new path forward in the wake of the elimination of affirmative action, the resulting suggestions are nothing new, relying on the same early decision, test required, legacy considered metrics that were employed alongside affirmative action in the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, without any new concrete metric to replace affirmative action, it is still unclear how racial diversity will be protected on College Hill.

Students for Educational Equity (SEE), established in 2019, is a student organization at Brown committed to achieving educational equity in the Providence community. In response to the formation of the Ad Hoc Committee, SEE introduced a proposal to voice the opinions of current university

students, as none were included on the committee. This included the results of a student survey conducted on 266 Brown undergraduates, 82 percent of whom voted in favor of the elimination of legacy admission practices. In a 2018 Undergraduate Council of Students(UCS) referendum , 81 percent of students voted to end legacy admissions.

“This is the time when Brown is going to make a decision, presumably for posterity, on these three policies we care deeply about,” said Nick Lee, co-president of SEE and co-lead of the Admissions and Access Team at SEE,which is concerned specifically with educational admissions policies. The proposal advocated for maintaining test-optional permanence and considering Restrictive Early Action as an alternative admissions option that would not be financially binding, alongside removing legacy admissions.

In 2021, the UCS proposed a resolution regarding the University’s preferential reception of legacy applicants, organized by SEE co-founder and Chair of Academic Affairs Zoë Fuad. This resolution cited numerous studies, essays, and other university policies advocating for the end of legacy admission preferences for the children of Brown alumni. In addition, UCS called upon the University to fully disclose the formal and informal benefits provided to legacy applicants.

Garrett Brand, Co-lead of SEE’s Mobilization Team, talked to the Indy about Brown’s stake in upholding legacy admissions: “It’s a funding mechanism, basically.”

“Legacy admits are wildly disproportionately wealthy people who are going to be most likely paying full tuition or even giving large donations to the University,” Brand continued. Wealth is overrepresented among the legacy population across the nation given the disproportionate access to higher education in terms of class, especially at elite institutions like Brown that explicitly pander to wealthy alumni donors.

According to a 2017 study by the New York Times, 38 colleges and universities in the United States, including Brown, admitted more students from the top one percent of the income scale (roughly $630k+) than the bottom 60 percent (less than $65k). For the class of 2013, Brown was ranked first out of 12 Ivy League and selected elite colleges in terms of median parent income. Brown has a notorious history of seeking out applicants from extremely wealthy and famous families in the hopes of attracting donations from such children’s parents and bolster its endowment, which is the lowest in the Ivy League.

For an institution that prides itself on progressiveness, wealth inequality at Brown is the most severe in the Ivy League. In 2023, Brown ranked last place among the Ivy League in terms of economic diversity and was 230th in the entire United States. In an interview with the Brown Daily Herald on February 24, Paxson remarked that if the University “were concerned primarily with socioeconomic diversity, it would make sense to eliminate this practice [of legacy admissions].” Evidently, the University still cares more about wealth than accessibility. With affirmative action out of the picture, it remains unclear how the University will be held liable for such inequitable priorities going forward.

Despite the long history of legacy-related advocacy by student organizations, Brown had not established a formal body for reviewing admissions policies until last year.

“When we got that news and heard that there was a committee announced, I think we had kind of dual feelings.” Lee told the Indy. “How efficient is [the committee] going to be? How equitable is this committee going to be? Are they actually going to make changes for the history of Brown?”

On March 20, SEE held a rally on the Main Green to oppose the committee’s decision. Afterward, students packed into the student center for the Brown University Community Council (BUCC) meeting, where members discussed ongoing questions about admissions policy.

“The takeaway is that there probably won’t be a final decision made for a while,” Brand told the Indy. “[BUCC] wants to take the time to properly gather community input from different stakeholder groups—primarily alumni.”

Lee also highlighted BUCC’s emphasis on community input: “If they’re committing to considering public input, I think it’s extremely necessary that students come out and show public input, especially on the legacy admissions topic.”

SEE released a public petition1 the week before spring break to call on President Paxson and Brown University to end legacy admissions and reject the notion that these policies can support equity and diversity.

In response to calls from the Brown community to commit to diversity, equity, and inclusion, Brown launched an action plan in February 2016 entitled Pathways to Diversity and Inclusion: An Action Plan for Brown University, or DIAP. This was intended to confront the University’s history of racist and discriminatory policy-making.

DIAP Phase II was shared in March 2021, five years after the initial action plan. Among the new actions included in the plan was to increase the number of Black/African American-identified students who yield or accept, their undergraduate Regular Decision offer to 50 percent over the next five years.

Yet, in 2024, first-generation, low-income, and BIPOC students remain underrepresented in the student body. Alongside class issues related to legacy, over 60 percent of all Brown students who claim legacy status also self-identified as white, despite white students making up only 37.8 percent of the overall student population. The continuation of legacy admissions will only exacerbate this, disproportionately admitting white and wealthy students. By favoring the children of alumni, the University perpetuates financial disparity in its admissions process from one generation to the next, valuing the potential to create future donors over the diversity of its student body. “If you can’t have a race-based affirmative action, there should not be any reason we have class-based affirmative action that panders to the wealthy,” Brand told the Indy.

Lee concluded: “We’re really just hoping that we can mobilize students to come out here to support equitable admissions and support people getting their fair shot, and having access to Brown resources and not just being an institution recycled for the privileged.”

The issue of equity in higher education for underrepresented communities is far broader than increasing access to Ivy League institutions. Protecting diversity at Brown only impacts a couple hundred students; thousands more low-income students of color will continue to face discrimination in higher education due to the consolidation of wealth and resources at Ivy Plus institutions that remain inaccessible to most students, no matter their admissions policies. To truly address inequities on college campuses, a broader scrutiny of the underfunding of public universities, evisceration of humanities programs, and lionization of so-called ‘prestigious’ universities-cum-hedge funds is necessary. Representation and diversity at Ivy League universities cannot be the horizon of higher education politics.

KEELIN GAUGHAN B’25 & ASHTON HIGGINS B’26 think $8,000,000,000 is already a lot of money for a school to have if you look at all the zeros…

1. SEE Petition

James Patterson produces novels like products, not literature. But does the literary world need him?

c So I wanted some Chex Mix. I was on a layover for a flight back to Providence, and my only option appeared to be one of those ‘newsstand’ airport shops where I could drop fifteen dollars on two snacks. Waiting in line to pay, I found myself facing a massive wall of books. Their dramatic covers— replete with silhouettes, crosshairs, and explosions —resembled posters for action films, as did their titles: 12 Months to Live; 1st to Die; and Alex Cross Must Die: A Thriller. Besides their clear concern with death, I noticed another commonality: James Patterson, James Patterson, James Patterson. I didn’t recognize him. The name seemed to be composed of such rudimentary components that it could refer simultaneously to anyone and to no one, like some kind of American everyman whose works reflected mass consumerist preferences and materialized on airport bookshops’ shelves, where such things naturally would. I googled him.

As someone who studies literature, I was embarrassed to learn that James Patterson is one of the most prolific authors on the planet. It turns out that he is an American novelist, known mainly for writing thrillers, and he is kind of a big deal. In his lifetime, his books have sold over 425 million copies, and from these books, James Patterson has made himself a brand and a fortune. Maybe you’ve heard of him. He publishes several novels per year, and usually these books would be considered ‘genre fiction,’ a loose category often used interchangeably with ‘popular fiction,’ which encompasses any work easily contained within a specific genre—e.g. science fiction, murder mystery, thriller, romance, etc.—and that often appeals to a wide audience. In an attempt at consolation for my ignorance, I scrolled down Patterson’s Wikipedia page to confirm that his works hadn’t won any major literary awards, which they hadn’t.

The Factory I started to become obsessed with James Patterson, with how fiction, my precious area of study, was functioning for him as a mass commodity, and a successful one at that. One out of every 17 novels bought in the U.S. is authored by Patterson, and his net worth is estimated to be in the neighborhood of $800 million. Patterson’s ludicrous sales success has granted him the life of a celebrity: he golfs frequently, owns multiple estates (including a 20,000 square foot mansion in Palm Beach), has co-authored a book with Bill Clinton, and has received fan mail from both George Bushes. A profile in the New Yorker described him as “unapologetically rich.” This seems a sharp contrast to the oft-romanticized image of the secluded artist: a mysterious, even cantankerous genius—à la Bernhard, Dickinson, Pynchon—whose isolation and fixated dedication frees them to transmit their thoughts raw to the page, all to make great art. This isn’t Patterson. He does not toil away at some undisclosed location to produce an idiosyncratic magnum opus, nor does he have any trouble selling books. If the theoretical genius-recluse embodies painstaking artisanal craft, Patterson

embodies the factory. He has cultivated an empire of sheer volume: over the span of his career, he has produced more than 130 separate full-length books, and typically, he releases several novels per year. But the not-so-secret secret is that he doesn’t actually write the novels, at least not anymore. In fact, he has a sixteen-person team dedicated entirely to ghostwriting—or, as it’s more flatteringly referred to in interviews, “coauthoring”—his novels. Essentially, he feeds outlines of characters and plots to his team, who then write the books. Vanity Fair has called him “The Henry Ford of Books,” perhaps a backhanded compliment. In 2015, a particularly productive year, Patterson released eighteen full-length books. His original success has allowed his name to bloom into a brand now supported by this army of writers, whom he credits in a far smaller font under the monolithic “JAMES PATTERSON” on his covers. Despite this kind of productivity and profitability, his books are rarely reviewed in major literary publications, and receive little to no attention from any critical or academic perspective. He is largely external to the literary world, and is not considered a writer of ‘literary fiction,’ a term that seems broadly understood on a vague conceptual and canonical level, but remains diaphanous insofar as its actual essence. For some, it is easier first to define ‘genre fiction’ (since genres themselves manifest for the purpose of categorization) and then work backward to form a picture of whatever its inverse must be, some shadow that is the ‘literary.’ Provisional definitions on the internet claim literary fiction prioritizes character development, style, and thematic complexity over the plot-driven and entertainment-oriented simplicity of genre fiction, though I’d argue this elides the complexities of many books that still employ elements of known ‘genres’ (I’m thinking of Octavia Butler’s Kindred as a good example). In any case, it seems Patterson has an idea of what ‘literary’ is, and how it isn’t him. In an interview he mentions his appreciation for Joyce, but also his distance: “I’m not even going to try to write serious fiction because I can’t get anywhere near [Ulysses],” he says, rather honestly. Regarding his contrast to other canonical greats, he has also said, “if you’re writing Crime and Punishment or Remembrance of Things Past, then you can sit back and go: ‘This is it, this is the book. This is high art. I’m the man, you’re not. The end.’ But I’m not the man, and this is not high art.” The classics of Joyce, Dostoevsky, and Proust, as well as the contemporary works that seek to continue what Patterson calls “serious fiction,” all represent what is respected and studied, what comprises ‘literary fiction’ and the avant-garde, and what, in today’s world, is largely unprofitable. In 2023, a survey by the Author’s Guild found writers of literary fiction experienced the biggest recent decline in book earnings: 27 percent over the last decade. They also found that genre fiction is nine times more profitable than literary fiction. Patterson’s obvious difference and immense financial success has brought scorn upon him from such communities, and elsewhere. In 2009, Stephen King (whose own books are never far from airport bookshops) described him as a

( TEXT EVAN MCHENRY

DESIGN LUCY NGUYEN PHAM

ILLUSTRATION REN LONG )

“terrible writer.” Online, Patterson’s ghostwriting seems to be a particular target area: “fuck James Patterson and his army of ghostwriters,” writes one member of Reddit’s r/books. Another blogger alludes to Patterson’s background in advertising: “Patterson realized he could mix his Burger Kinglevel marketing skills with his substandard writing and vomit out some trash to read, all while making a pretty penny on it.” Damn. But between the short chapters (often only a page or two), repeated characters and content (there are 35 “Alex Cross” books alone), and straightforward syntax (“The window shattered. The bullets hit hard.”), Patterson’s work betrays the assembly line it was manufactured on.

Entanglement