“Alex imagined … himself still there—his young self, full of schemes and high standards, with nothing decided yet. The fantasy imbued him with careening hope.”

A Visit From the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan

Because she thinks she can’t get older, because she thinks she’s running out of time, I say, “We’re so young.” When that doesn’t work, I pivot. In a winter away from home, time is stagnant. I will leave the same age I arrived. I ask her: does the future ever thrill you with possibilities? Not each permutation of whatever life you might live, but the love you’re sure to experience, just by being. Usually I reference the stranger in the café in New York, who lent me his entire laptop for over an hour so I could finish my essay on time. But I am starting to see myself in the same light, a nameless figure content to be so, primed to give and sit beside.

Before I would have said that each year shaves a branch from the deci sion tree. Now I want to tell you that getting older makes tenderness the only certainty. Instead it teaches the structure of a question. How can I say if each day inundates me with all of the love the world aches to offer? If believing in its presence is instead like cooking myself dinner, working the shift, locking the door. Something I have learned I must do to live. –CL

MANAGING

EDITORS

Corinne Leong Sacha Sloan Jane Wang

WEEK IN REVIEW Masha Breeze Nora Mathews

ARTS

Cecilia Barron Anabelle Johnston Lola Simon

EPHEMERA Chloe Chen Ayça Ülgen

FEATURES

Zachary Braner Ryan Chuang Jenna Cooley

LITERARY

Madeline Canfield Tierra Sherlock

METRO

Jack Doughty Nélari Figueroa Torres Rose Houglet Nicholas Miller

SCIENCE + TECH

Justin Scheer Ella Spungen Katherine Xiong

WORLD Priyanka Mahat Alissa Simon

X

STAFF WRITERS

Hanna Aboueid

Madeleine Adriance

Maru Attwood

Graciela Batista Kian Braulik Mark Buckley

Swetabh Changkakoti

Laura David Emma Eaton

Danielle Emerson Mariana Fajnzylber Keelin Gaughan Sarah Goldman

Jonathan Green Faith Griffiths Eric Guo

Charlotte Haq Anushka Kataruka Roza Kavak Nicole Konecke Cameron Leo Kara McAndrew Morgan McCordick Sarah McGrath Charlie Medeiros

Kolya Shields Alex Valenti Julia Vaz

Kathy/Siqi Wang Justin Woo

COPY CHIEF Addie Allen

COPY EDITORS /

FACT-CHECKERS

Ava Bradley Qiaoying Chen Dun Jian Chin

Klara Davidson-Schmich

Eleanor Dushin Mack Ford

DESIGN EDITORS

Anna Brinkhuis Sam Stewart

DESIGNERS

Brianna Cheng Ri Choi

Addie Clark

Amy/Youjin Lim Ash Ma

Jaesun Myung Enya Pan Tanya Qu Jeffrey Tao Floria Tsui Anna Wang

ILLUSTRATION

EDITORS

Sage Jennings Jo Ouyang

ILLUSTRATORS

Lucia Kan-Sperling Seoyoung Kim Maxime Pitchon

DEAR INDY Annie Stein

BULLETIN BOARD Sofia Barnett Kayla Morrison

SENIOR EDITORS

Alisa Caira Sage Jennings Anabelle Johnston Deb Marini Isaac McKenna Peder Schaefer

Zoey Grant Aidan Harbison Doren Hsiao-Wecksler Rahmla Jones Jasmine Li Rebecca Martin-Welp Everest Maya-Tudor Eleanor Peters

Angelina Rios-Galindo Grace Samaha Shravya Sompalli Jean Wanlass

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Klara Davidson-Schmich Britney De Leon Ayça Ülgen

Sylvie Bartusek Noah Bassman Ashley Castañeda Claire Chasse Julia Cheng Nicholas Edwards Lillyanne Fisher Sophie Foulkes Haimeng Ge Elisa Kim Joshua Koolik Lucy Lebowitz Sarosh Nadeem Hannah Park Sophia Patti Izzy Roth-Dishy Livia Weiner Iris Wright Jane Zhou Kelly Zhou

DEVELOPMENT COORDINATORS

Anabelle Johnston Bilal Memon

DEVELOPMENT TEAM

Rini Singhi Jean Wanlass

MVP Anna Brinkhuis & Sam Stewart

The College Hill Independent is printed by TCI in Seekonk, MA

The CollegeHillIndependent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and selfcritical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

Read it and tweep is the message from Esther Crawford, this month’s most notorious somniac. Twitter manager Crawford made headlines on November 7 for her surefire strategy to secure a femmeboss image despite mass layoffs at Twitter HQ. “#SleepWhereYouWork,” Esther proudly tweeted, hopefully a true-to-form act of somnam bulance that heralds the outsourcing of Twitter la bor into the sleeping and waking mind. Celebrated as a “spitfire” by laid-off coworkers in the replies, you’re probably wondering how she got here.

See online a video of Twitter Product Manager and CEO Elon Musk swaggering into San Fran cisco’s Twitter headquarters on October 26 with a sink. “Let that sink in,” cried the new owner, only to sink Twitter within the coming week. Musk fired half of Twitter’s 7,500-person employee base last week in a layoff operation intended to build the platform back during a lagging economy. Tesla advisors suggested that Musk attend to “diversity and inclusion” during the cuts so as to avoid a precarious legal swamp, a proposition apparently ignored. Musk et al. realized soon after the cull that no one knew how to use particular “mon ey-generating products,” and Twitter execs soon rehired their beta-male, or rather “weak, lazy, and unmotivated” engineers back.

“Bankruptcy isn’t out of the question,” said Musk, implementing new policies such as a pay-to-eat cafeteria at headquarters and the im mediately-suspended Twitter Blue feature to scrap back a couple bucks. That “Blue” feature meant that from November 9 to November 11, 2022, you could buy a verified check for a monthly eight dol lars. This 48-hour feature enabled the verification of Jesus Christ as well as mass impersonation of politicians during the night of the midterm elec tions. If I were on Twitter, I would impersonate my College Hill Independent right-hand DJ Kolya Shields but not in order to lie, just so I could publish ev erything they have restricted to their Circle (<3). His mind sublime, Musk supplemented that any account engaged in parody must now add “paro dy” to their name.

Many words have been spilled about Musk’s father’s Lake Tanganyika emerald mine, his cuck olding by Chelsea Manning, or his brave claim, “I have no idea how to smoke pot.” My favorite moment in Muskstory came during the unveiling of the Cybertruck. After asking the demonstrator to throw a stone at the purportedly indestructible car window, you watch the glass shatter and feel Musk sweat and quiver through your monitor. Alas, no castration humor will phase Musk, who’s maintained a veritable rotation of partners and a spawnpool now at ten critters.

In his 2014 Commencement Speech at the University of Southern California Marshall School of Business, Elon wanted to give the young come-uppers some advice.

“When my brother and I were starting our first company, instead of getting an apartment, we just rented a small office, and we slept on the couch. And we showered at the YMCA.”

A moment later:

“I, sort of briefly, had a girlfriend in that peri od, and, in order to be with me, she had to sleep at the office. So.”

Rather than psychoanalyze the urethral tunnel made for electric vehicles running through Los Angeles or the impetus to perform humanitarian work only when it involves rescuing Thai children from an underwater cave, perhaps we, like Esther

Crawford, need to bury our heads in the prover bial office futon, and #EmbracetheDigiYuppies #BrownComputerScience2023

If you can’t code, better find yourself a man’s (or woman’s (or non-binary person’s)) Palo Alto office couch and wait until his/her/their next coding break for some totally protected sex that won’t result in your bearing the next generation of C3^pG72e& babies. If your lover’s office floor belongs to a “diverse and included” software engineer, maybe they’ll even be able to hold a job at Twitter, so get your chase on. To quote a woman and Twitter-employee-at-time-of-writing Ms. Crawford, “‘You’ll never do a whole lot unless you’re brave enough to try.’ —@DollyParton.”

liked the “!!!” Hunter Schafer comment; they don’t listen to podcasts like that. She has to prove her transness; they can fall back on feminism.

There’s just something about his aloof attitude and greasy hair—and something about her capacity to see the kickflip as a deterritorialization of streets ruled by the Law of the Father (Car). She subsists on bone broth, ketamine, and a modeling deal (with one of those agencies that looks for ugly girls), he’s totally enmeshed in the Providence scene (they bonded over misogyny).

He has a Circle, she has a close friends. Dis course won’t get you pussy, but a story like might. They think edginess makes up for the lack of emotional vulnerability—probably not. But, l’ll still click the link in bio (duh).

Neoliberalism and Occupy

Multiculturalism and ‘subversive’ organization might seem to have no common ground—but have you considered that both give white peo ple a radically non-material way out?

What better to dull the blade of misogyny than drugs! Anyways, he’s too fucked up to protest the prenup. His apartment has never looked better than under the sheen of a free eighth.

VISA and RISD

In the alienated, individualistic late-capitalist world of the dating app and the pronouns circle, natural, flirtatious sociality has atrophied. We went from classic meet-cutes and the comfort of the nuclear family to an impotent polymor phic autoeroticism—boys prostrate themselves before the crypto-phallus, entranced by the promise of an infinite/infantile online flexibil ity. A constantly present e-girl blows you in the gaming chair until you come to and realize it’s just you and an icy blue screen announcing GAME OVER

Luckily, here at the Indy, we understand that opposites attract. Instead of catching your own reflection, your enumerated (false) desires glimmering on a cracked phone screen, we be lieve in the real of difference. Unplugging from the self-referential spiral of online identity is the only way to truly see and respect the other as other; instead of undifferentiated, networked cyberspace, the brave vulnerability of unmed iated interaction shows who you really are. On anatomical, psychological, and social levels, our partners should fill our gaps, make us (a) whole As the Indy’s premiere autogynephilic binary transsexual dialectical materialist (sorry Kian and Masha), I’ve taken the liberty of laying out some topical examples of bio-psycho-social compatibility. Hopefully this shiplist will prove that organic difference will always triumph over constructed multiplicity.

She wears short skirts; they wear oversized fishing t-shirts (Fishing is Like Boobs: Even the Small Ones are Fun to Play With). She

Bonding over the impossibility of registering for the classes they want, they fixate on each other’s constructed alterity—apparently the starving artist has no home in an image-ob sessed society? It’s hard enough being a true creative in this homogenized, capitalist world without all these damn posers thinking they can readymade their way out of mediocrity. Luckily they can browse the TheRealReal to gether to find frilly tights that accentuate their thigh gaps when daddy’s money runs out.

Maggie Nelson and Chelsea Manning

She’s really into the strap. She has what some might call the ‘bio-strap.’ They both have ravenous non-binary fanbases. What better to deal with the stresses of fame than a back 2back Boiler Room set?

I’m both too aggressive (man behavior) and too stupid (woman behavior). She’s just a hole. What if we got together and said fuck you!

There’s something strangely true in a joke… has anyone ever really thought about that?

Financial Aid and the Middle Class

They both constitute themselves against the (true) specter of the nepotism baby…can they find the synthesis of class solidarity? Per haps the way out is neither McKinsey nor the non-profit but simply the guillotine for the notably named among us.

Have you ever thought about how the spirit of history moves in a progressive, dialectical fashion? One girl’s antithesis is another’s first real orgasm!

KOLYA SHIELDS B’24 thinks the feminine rela tion to the phallus, and therefore humor (as the unsignifiable real), is grounded in self-hatred.

ILLUSTRATION SAGE JENNINGS

DESIGN TANYA QU

TEXT KIAN BRAULIK & KOLYA SHIELDS

Mathematical Theory of Communication. The article came out of Shannon’s wartime cryptography research at Bell Labs, AT&T’s former research laboratories. The probabilistic approach to communication—IT’s big innovation—led to a somewhat counterintuitive definition of “infor mation.” It’s a technical definition that has to do with coding schemas—the rules by which data is translated into binary—but the key take away for our purposes is an inverse relation of information with likelihood. According to this definition, the observation of an unlikely event has high information, while the observation of a likely event has low information. Back to our “curling hair” example: there would be very lit tle information contained in the event that the next letter is “r,” but if we observe that the next letter is actually “q,” our observation would be very “informative,” as it were.

more sentences given, our sense of the author’s style and direction more solid, we could go on adjusting our approximations of the probability of any particular letter appearing next.

THE FOREHEAD WAS ROUND AND SMOOTH, AND THERE WAS A CURIOUS BUMP AT THE BACK OF HIS HEAD, COV ERED BY

CURLING HAI_With high certainty, we could say that the final missing letter is “r,” which would spell hair—curling hair. With some degree of cer tainty (though less this time) we could guess the first letter of the next word. It looks like “hair” may have been the terminal word of its sentence, so the probability of the next letter after “r” being some particular letter, say “o” or “a,” is markedly less than the probability of “r” following “i” to spell “hair.” The next sentence could go anywhere. Who knows what its author is capable of—how erratic their style is, what arc the passage will take on, etc. With all of these questions open, but with the helpful assumption that character choice is limited to the English alphabet, the probability that the next letter is any particular letter, say “o” or “a,” is somewhere around one in 26. Familiarity with the English language dictates that “x” is a pretty unlikely candidate, so maybe that figure is closer to one in 25. Supposing we had a few

If you’ve ever written or read anything, spoken or been spoken to, this mode of receiv ing a sentence—that is, as a question of proba bilities—probably felt unnatural. And not just letters in language; we could inspect the color value of each consecutive pixel in an image, for instance. In the broadest sense, we could encounter any digital communication from one person to another as a construction of individ ual symbols appearing probabilistically. This logic, arbitrary as it seems, is the central tenet of information theory, a field of mathematics at the core of all digital communication technol ogies. It is precisely this logic that governs the translation of communications (text, images, etc.) into the 1s and 0s passing immaterially from machine to machine. And so it is the logic beneath the vast com munication webs that link us, of the digital economies that entangle us. Its limits are, perhaps, the limits of social and economic life in the digital realm. The structures of control in communication—and on the internet in particu lar—relate to this logic, opposing and constrain ing the uncertainty that it describes. +++

Information theory (IT) emerged with the publication of Claude Shannon’s 1948 article, A

This idea of information may make more sense from a machine’s perspective, if we can imagine it. The machine doesn’t care much about coherence or meaning per se. Its ap proach to the world, to the signals it receives, is far too rigid and methodical to accommodate a sense of “meaning” (at least not until AI came along, but that’s a whole other conversation). The machine is interested, first and foremost, in how predictable something is. A likely event is a more predictable event, and the more pre dictable the event, the less the machine learns anything new about the world from that event, roughly speaking. If something happens that one expects to happen, in a sense one hasn’t gained new information by observing that thing happening.

In the introduction to Communication, Shannon distills his motivating challenge, what he calls the “fundamental problem of com munication,” as “that of reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a mes sage selected at another point. Frequently the messages have meaning.” Frequently, but not necessarily. The inverse relationship of likelihood to information, as Shannon defined it, sets up a paradox, a dichotomy of meaning and information. If a more likely choice of letter, given the preceding sequence of letters, is a choice which tends to make more sense semantically (a real word usually makes more sense than a nonexistent one), Shannon tells us that the more informative letter choice is often one that makes less sense—or, at the very least, the most informative letter choice need not make sense.

As the thought experiment from the point of view of the machine suggested, information theory affirms no particular commitment to language as a medium for coherent thoughts or

Communication, possibility and control through the lens of Information Theory

TEXTto communication as a medium for meaning. At first glance, a probabilistic view of communication seems to imagine its building blocks as fundamentally random. An information theoretic study of language might take a text bank (a bunch of books, for instance) as its data set and analyze the frequency of each letter (or the frequency of a letter when preceded by a particular letter, or the frequency of a letter when followed by a particular letter, etc.). A hypothetical speaker would thus choose letters randomly in accordance with the probabilities estimated by those frequencies, as though the speaker’s choice of each letter were determined by a (weighted) dice roll. By a sort of circular logic, information theory, as applied to text and speech, seems to substitute the culmination of the cognitive processes behind language in place of their origin.

But maybe this is unfair to Shannon and his theory. Perfect and complete knowledge of a system, of all causal chains producing ob servable effects in that system, would make a probabilistic approach unnecessary. Why consider the probabilities of each of several out comes if we can predict the actual outcome with 100% certainty? To approach human speech/ text in terms of probabilities, then, is not so much to make an unfounded assumption about the cognitive processes behind language, but to humbly acknowledge the limits of knowledge: to preface the entire project of information theory in its application to language with an admission that much is unknown about how the human brain works. Speech’s determinants and their paths of cause and effect are a mystery, the theory seems to say, so the best we can do is suppose that sen tences, words, and letters are chosen at random

Information theory borrows a crucial bit of terminology from thermodynamics: entropy IT’s entropy and thermodynamics’ entropy don’t have much in common besides a vague resemblance in their mathematical defini tions. Entropy in the IT context is the average (“expected,” to be mathematically rigorous) information content taken over the entire set of possible symbols. In short, it is a measure of the “unpredictability” or “uncertainty” of a sequence of symbols (letters) constructed out of a given symbol set (alphabet). To illustrate this, suppose hypothetically that in all English text, the letter “a” occurs 99% of the time. In this scenario, the English alphabet would have very little entropy; that is, each letter is highly

predictable, since it is almost certainly “a” every time. An entropic, highly unpre dictable alphabet, on the other hand, is one whose letters all occur with equal frequency and in no discernable pattern, so that no one letter is more likely to occur in a passage of text than any other.

When encoding an alphabet in binary, information theory provides a limit on the efficiency of any coding scheme on that alpha bet, where ‘efficiency’ refers to the average (expected) length of binary code needed to encode a letter of the given alphabet. A mes sage encoded in binary is at least as ‘lengthy’ and inefficient as the entropy of the alphabet is large. This ‘entropic limit’ sets up an opposition between efficiency in the communication of a message and the unpredictability of that message—the latter as a con straint on the former. This oppo sition lurks beneath all modern communication technologies, all systems by which data is sent and received. It is a fundamental bound on the efficiency of digital communica tions in terms of message encoding, and thus suggests a limit on the functioning of digital economies—it is everywhere and all the time.

Digital economies (and all econo mies, for that matter), in pursuit of efficiency and profitability, live and evolve in tension with uncertain ty. All the time, new technologies emerge that, while opening up new connections and modes of (in ter)action on the internet, tend to constrain the terms of those connections by preforming and predetermining the messages sent through them. Common experience with the trademark structures of the digital economy and internet communications are instructive here. Algorithms—dictating recommend ed-for-you media content or search results on the Web, for instance—shape a user’s tastes, interests, and ideas, influencing online behavior in turn. Online media platforms give us a finite set of preformed options for engagement with media. These examples of controls on online behavior are designs of a tech oligarchy, to be sure, but constraints on possibility and unpre dictability also persist in free-floating, dispersed forms, which are not necessarily machinations of a Silicon Valley regime. In particular, the same tension between proliferation and restric tion of possibility plays out on the less visible level of protocol, described by media and com munications scholar Alexander Galloway as the

decentralized control structures underlying the internet. Like their etymological predecessors in diplomatic negotiations, they are not imposed from above but emerge as norms from horizon tal interaction between people. Galloway likens protocol in technical form to the interstate highway system: “many different combinations of roads are available to a person driving from point A to point B. However, en route one is compelled to stop at red lights, stay between the white lines, follow a reasonably direct path, and so on.” Thus, the countlessly many permuta tions of connection, an unbounded set of possi bilities, are reigned in under protocol’s control. Connections multiply in number while their substance—the digital communications they transmit—are controlled and, to some extent, predetermined.

The sense that the internet, once billed as a revolutionary democratic alternative to top-down media structures, fell short of that promise points to a preference for the predict able and to the structures of control—imposed from above and materializing from within—of an ostensibly horizontal, distributed, non-hi erarchical space. To be clear, it’s beyond the scope of this article to prove that the limit on efficiency, as information theory articulates, is the ultimate source of this control. It may not literally be the entropic limit which directly produces these real constraints. But we can at least pay closer attention to the ways these con straints appear concomitantly with information theory’s entropic limit on efficiency. We can ask how this limit exists in relation—as synecdoche, as root cause, or somehow else—to the digital economy’s natural antagonism toward unpre dictability and preference for certainty. +++

Shannon chose to approximate language and communication as a game of probability, per haps out of a humble lack of knowledge of the cognitive processes that give thought a symbol ic form, but this approach leaves much to be desired. If science seeks incessantly to master the puzzles of cause and effect, to know all determinants of all phenomena, it must view information theory as a job only partially com pleted—or rather a job whose point of departure was prematurely advanced. These puzzles have evidently not been solved; by way of constraints on unpredictability, the determinants of com munication have not been discovered so much as constructed

JUSTIN SCHEER B’23 hopes the message got through.

When, during one of their runs, Hannah and her teenage daughter Mira heard the music beckoning from the next street over, it was al ready late into the summer. The sound hummed toward them like a soft interruption.

The string instruments beckoned. They followed the sound the way they followed the ground, tentatively, then with dedication, as if it were a tangible thing, a rope to grasp and pull themselves forward, or maybe one which wound itself around their wrists and yanked their yielding bodies toward its other end. Entranced, they ran slowly, the music deliver ing them to its makers. A gathering riddled the grass of a plain house. Ten or fifteen people, some on the lawn and others on the curb across the street. In the center, two folding chairs, and their occupants, the musicians. A violin lay trapped under the chin of the man in the first seat, and a massive cello submitted to the woman in the second, her splayed legs encasing the wooden body in her embrace. He shook a bow between the fingers of his right hand and she shook one in her left. He wore coral kha ki shorts and she wore her hair cascading in sheets across her shoulders.

The whole affair seemed liminal, uncertain of how it had emerged—impromptu for the audience drawn out by the curi ous music, but de liberate,pre-ar ranged, for

the musicians. A middle-aged couple, one accustomed to innovating interesting ways of occupying their time because their children had by now grown and fled from them. The music billowed with a sharpness, like the movement of a curtain jutting upward and cinching to a crease, a precipice that loomed high above its gaping slope—before suddenly plunging down ward, flattening first into the slow roll of hills and soon all the way back to a quiet ripple, but the imprints of the previous motions remained, the traces of the crease lurking long after the curtain had straightened out again. This audi ble, visualized motion was the strings’ doing. The violin and the cello paired beside one another, their strings a lull of vibrating steel, a series of drowsy low notes inhaling upwards into a tremble, a trembling, a quivering, then a shaking, then a seizing, then crying crying cry ing, screaming out those final high notes when the bow struck the strings at its most desperate of angles.

An odd array of noises, for a residential street in the evening. None of this looked like the backdrop of a concerto. But the mu sician-neighbors seemed only aware of how tightly they gripped their instruments so they might squeeze out the perfect sounds, no mat ter the incongruity between those sounds and their surroundings. And the audience-neighbors stood, mesmerized by the talents of these am ateurs who mimicked professionals, this house and this lawn and this cracked curb reminis cent of all the accouterments of some old concert hall, perhaps an opera house with plush seats, the one in Paris let’s say, its ceiling painted by an immigrant artist who wanted to render an image in col ors, something of red, yellow, blue green black that wheeled around in a circle and now matched their sky as it melted with the setting sun.

They shouldn’t have been surprised at the effect of the performance, for didn’t they, like everyone else, know that the only function of the violin was to convey a state of longing?

To inject some thing invisible into the atmo sphere, the pulsing instability of their

thoughts, the jagged polygraph of their breaths?

The two of them succumbed to something slow but anxious, a recollective state of mind, one which lacked articulable thought, in the way the mind lies dreaming inside the body. It was the perpetual condition of listening to mu sic, voices which overwhelm you so totally that you believe all you have ever done and all you will ever do is hear this, that your life will only be sound, even if the sound only rings on repeat inside your head.

The violin, the violin, the music heavied their eyelids, there was a cello too but they heard it less. They became more and more aware but less and less alert, overstimulated into lethargy. They blinked. Mira’s gaze fell upon a tree with pink fruit—pomegranates, small ones that would fit within two cupped hands, growing a couple months out of season, but nevertheless already ripening into the red of an infectious blush. Hanging upside-down on this neighborly tree was the fruit they associ ated with their holidays, with the Jewish new year, a time of joy for the promise of another beginning yet a time of unspoken wistfulness for all that had gone wrong in the months prior. Mira began to taste the memory of pomegranate on her tongue; the real violin notes bled into the conjured tastes of the fruit. The borders between senses folded into one another until everything coincided, her perception lost in what was liminal.

Hannah spent those transitory minutes captured by the sight of another human. The music’s melancholy scratches and slices had already unsettled her into complacency when she saw K. Her Nazi. The man with piercing blue eyes and a name wracked with a field of consonants. The man who claimed his family hailed from Argentina, one of the “far away” places to which Europe’s suspicious characters had kindly run after the war. The man who Hannah trained in his medical studies, who al ways seemed disingenuous, disinterested when he looked at her and when he cared for patients, as if he were thinking about more important things than the ailing people in front of him. At the concert, too, with a slight smirk toying with his mouth, he gave the impression of being unsatisfied, of being elsewhere, drawing in that elsewhere to meet him on this lawn, the physi cal spot he could not leave because he had come of his own volition.

Of course Hannah’s recent fixations on K

would eventually manifest the man in the flesh, so close to her home. Ever since her revela tion about K’s Nazi parentage, thoughts of K taunted Hannah: specters, visions, inklings of disquiet—he hovered around the edges of her attention, springing forward at any oblique reference: articles on far-right extremism in the military, books about the migratory patterns of former state leaders, news of cemeteries vandal ized with swastikas. The obsessions swarmed her. She watched K get into a blue Volkswagen one day after work; whenever she saw one on the highway, she wondered if it was him. She noticed a man at Target with K’s blond hair; she trailed him through the aisles before he finally turned and it wasn’t him. Recently, a friend told her that K lived only a few blocks away; Hannah had twice “gone on a walk” that convenient ly passed his home. From the sidewalk, she peered inward but saw nothing but a staircase ascending until it faded into darkness.

Hannah and K occupied the same spheres, worked in the same building, walked past the same trees and the same cars and the same houses each day. Though she barely spoke to him, Hannah understood now that she and K shared one landscape. Her landscape, which this man had invaded. A real-life (child of a) Nazi lived in her backyard, making his liveli hood from Hannah’s mentorship. His presence infuriated her. The audacity of this K, to inhabit her thoughts, her streets, the sites of her story! She was the one who ran; murderers stayed put with their governments. K lacked even the decency to arrive on her doorstep as a Ger man—he’d rinsed himself of his origins with a childhood in a third country, a third culture, a third language.

Now, in the outskirts of her daily run, here he stood again, broad shoulders and an angular head jutting up from the tall plane of chest, torso, legs—a hulking cross, dwarfing any one who drew near. Where Hannah sprouted wrinkles, youth clung stubbornly to his face, his hairline, his entire image, his features refusing to reconcile themselves to the passage of time. Aging—the process of reaching the present by moving out beyond the years that chiseled us. As Hannah watched K listen to the music with such nonchalance, as if impervious to the violin’s lament, her usual feeling towards K was overtaken by the feeling always lurking un touched beneath it, an exasperation soaked in fright. Why must this man keep reappearing?

Eventually, K turned to go, raising his hand at an angle, a small wave to the couple, a good bye salute. At this, Hannah reconvened with her daughter.

“Mira.” Her name was a hiss seeping out from her mother’s teeth. A line to reinsert the boundary between senses and categorize Mira back into herself.

“It’s K. The Argentinian Nazi. He’s on the left, watching the show—except, he’s leaving.” Hannah grabbed her daughter. “Let’s follow him.”

The run resumed itself. The dirge of the violin trailed them like a stream of tears pour ing forth as their strides revealed their inten tion. They followed as K yanked open his car door thrust one leg inside curled the rest of his body to meet that leg slammed the door shut. His car, the blue Volkswagen, it revved its engine it zoomed it curved away from the curb it zoomed. He was in the car so his motions sped they sped all at once. Why he had driven

when he lived so close, why he had deliberately attended this performance when the rest of the audience appeared spontaneous, Hannah and Mira could not fathom the answers but they had no time for questions, the music was fading and they chased him in silence.

They chased him past rows of houses, homes with perfectly-mowed lawns, and homes overrun by shrubbery, and homes with no greenery at all, their lots plastered over by the cracked cement of sidewalks and driveways; onward past box hedges, oak trees, azaleas blooming, shady patches and sun-scorched ones, a scenic route yes a density of pretty things, they chased him past variety but regis tered none of it, registered only the image of his car retreating into the maze of streets paved before them. He never went more than twen ty-five miles per hour, but to them he careened across those streets. He sat pumping the pedal while sitting inside an automated sheath of metal; they pushed through the air unprotected, all their muscles raging, not merely a driver’s single foot. They fled towards him in sync, hurrying fluidly, hurrying organically, hurrying strong. The running was difficult but simple because now they knew how to do this, this action they called running, now that they had practiced, well, now that Hannah had instructed them to practice, now slipping through their fingers if they ever became brazen enough to grasp at it, look at it, think about it, now only ever the idea of what could not be contained, now a violence taunting the impossibility of the present with the inevitability of the past. Now was only ever forward or backward, never that point where feet touched ground. They were on foot, so while they ran, ran, sprinted with an uncontained velocity escalating by the sec ond, each step headed towards a new place yet enumerated a drawn out sequence of behinds, compounding and compounding, expanding and expanding, an infinite series of individual nows stacked up against each other, another note penciled onto the bar of sheet music, anoth er meal cooked to perfection yet left uneaten, another photograph propped up on a bookshelf, another question shored up from an earlier era and rewritten into the screenshots of their moment, another soccer ball kicked and another sports game lost to a stray invective, another friend smiled and waved at until forgotten, another necklace clasped around an unsuspect ing neck, another wave crashing along the great expanse of contiguous ocean, another child con ceived and carried and cast out from the birth canal, upon which there was always another storm to prepare for, another pair of candles to light, another text message or news notification or video clip or some other form of memory sauntering out from the fray to laugh in cahoots with the real world playing out in front of us. They ran through each punctuation along their line of everything.

CANFIELD B’24 does not listen to music when she goes on a run.

I did not believe my mother knew me. At age nine, a newcomer to Pennsylvania—this state where whiteness grew like banyan roots an chored deep into soil—I knew only one thing, that there was no path forward for me. Not because of the sheer white plant mass; rather, my disaffection, my anger were functions of my distance from that mass, the loss of my white Californian friends, the loss of my casual inte gration into the drought-stricken lands where faces like mine were unsubtly everywhere. We went to a Gap Kids at the Lehigh Valley Mall in search of clothes. Something new to cover up with.

All mall interiors look more or less the same. Having been to a number of malls in my life, I can attest to this sameness and the way it leads me from place to place, room to room like I live here, like this is my home, a place of origin, conception, definition, familiarity. If I were blindfolded and released into any Macy’s, and I took off the blindfold to witness the rows upon rows of half-formal blouses and the little cardboard kiosks of makeup and perfume in the middle of the first floor, I would immediately know where I was. I can picture the deep inside of a Victoria’s Secret, the black shelves and the dismembered mannequins with their neatly stitched cleavage and polyester lace thongs. A Hot Topic, with its Boruto and Naruto and HunterxHunter and One Piece T-shirts lining the wall next to checkered miniskirts and wallet chains.

Gap Kids was no different. Nearly every thing in here was made of cotton fabric with that filmy, translucent texture, the kind that wind could pass through with ease. I was at the age when running off to look at things on my own was still not permitted. But I did those things despite myself, forgetting, for a second, to mind the invisible leash that should have kept me tethered to my mother’s hip, and disap pearing behind a rack of marshmallowy parkas to feel their protruding hoods with my finger tips. Then I’d feel a tug on the invisible leash and turn around to find my mother, with an angry look on her face. Why did you leave me? It’s not safe to run off like that. What are you looking at? She dug around inside the depths of the children’s large-sized parka—it wasn’t until later that I was allowed to buy clothes that weren’t two sizes too big for me—and pulled out the price tags with her free fist. Hmm. It’s on sale, 30 percent off. San, qi, ershiyi. With the same hand, she reached under the parka to find the fabric tag. Aiya, it’s polyester. No polyester for you. When I tried to protest, she said the same thing again. You cannot wear polyester. It makes you too hot and itchy.

So every shopping trip was about devasta tion. Never mind that Pennsylvania, which was basically an ice age waiting to happen, had the perfect winter to justify hot and itchy. I lowered my head and resigned myself to ugly clothes that were neither uniquely fluffy nor perfectly sized. You still need space to grow into your clothes, my mother said.

Dutifully, I followed my mom around the store, letting the leash tug me through aisles, under fluorescents, and past shelves of dark denim and striped sweaters. A stray hanger or two littered the floor, their accompanying garments lost in the Gap maze. Then I noticed another magical clothing item that with all likelihood contained a forbidden synthetic ma terial, and scurried toward it. A floral skort, just above knee-length, modesty-proofed by the set of white shorts hidden underneath the crown of loose cotton, was the only clothing item I picked out that made its way into the try-on pile. It was

white with pink and orange roses, and looking back, I cannot help but be both embarrassed by my lack of taste and jealous of my boldness. If I had a skirt like that today, I think. Everyone would be obsessed with me.

My mother brought a good rack of clothes into the fitting room, half of the bevy assembled from other articles with the same oversized fit but in different colors. She hung them up on the assorted hooks that dotted the stall door, gave me an impatient look in the mirror, and pointed at the hanging collection. Now strip. Undressing in front of my mother was always an ordeal, not least because when I turned eight and began to notice how my thighs puddled when I sat down, I knew she was right about how I needed to start eating less. Two weeks before, she pinched the side of my stomach and murmured to herself, something in Mandarin about laoma wei ta tai duo le. I bristled, felt that monster of vexation claw its way up my throat, a monster which was quickly beaten down by another mouthful of rice, always with the rice or the chicken or the broccoli. My grandmother and my mother fed me in turns, like it was a competition to see who could fill the recepta cle faster. There were piles of leftovers—of the most delicious dishes that would otherwise become cold and congealed, wasted in the refrigerator—that I schwoomed up, me, the vacuum. Eat more of this, my mother said, spooning beans onto my plate. More of this, my grandmother said. You have no self control, my mother said. I sat on my hands and rocked forward, out of the reach of them both, resenting how good it all tasted.

I hated undressing in front of her, but in a fitting room as small as this, in a store, in my pre-adolescence, when I wasn’t allowed to be left alone with my thoughts for even a minute—I had no other choice.

The pants came off first and were quickly replaced with my chosen rosy skirt. At least I could pick the order in which I tried things on. I swirled my hips around, watching the pleats flare out like dresses in the movies. I liked the way that the skirt covered the tops of my thighs, the thickest parts, making the rest of my legs look reason ably skinny. I couldn’t tell if my mother agreed, but she was in the practice of letting me have something in order to keep me quiet. Other wise, when I became fixated on one special item that I was convinced could be a cure-all for my

malaise, I would posit a poorly constructed argu ment that escalated, albeit unintentionally, into a tantrum, which the entire occupancy of Gap Kids would be able to hear through the thin walls of our stall. So we put it onto the ‘yes’ hook.

We moved through the collection quickly—a sweater dotted with clouds here, a shirt adorned with horses there. I was becoming more irritable by the second, tired of scratchy clothes coming on and off, mussing my hair, making my arms and chest and back tingle until I wanted to scream, to tear my skin into tiny miserable strips like through a shredder. The inside buttons of my adjustable jeans rubbed too hard on my hip bones, leaving indents, and these were feelings I could not explain, feelings that I look at now, turning them over in my hands, noting how they surge, then lay flat, then swirl around, meander, peter out. The feelings are try ing to burrow beneath the skin of my palms to get under cover. They don’t like how I hold them under a beam of sunlight. Now, as then, they draw glances when I wrest them to the surface, and then they shy away, they hate drawing attention to themselves, but they also want to take up space, to expand—

I don’t want to do this anymore. Are we done yet? My mother looked down at me, disappointed for some reason I couldn’t discern. Weren’t these clothes for me? What right did she have to look dis appointed, like I was robbing her of the kind of per son she wanted to be? She looked at the ‘yes’ hook and the ‘no’ hook, the former jammed substantially fuller. My mother always got what she wanted, even if I fought her with childlike vehemence. She flipped through the remaining items and settled on one, careful as she teased its hanger out of the stack so that the rest didn’t come toppling down. Okay, she said. Just try this one.

I chewed on my lip and nodded. I let her hold the hanger and slipped the electric blue shirt off of it, trying to reign in the raging tide that boiled in my chest, to fold it under more layers of clothing. A glance at the shirt in my hands told me that it was not really unique in any way, except that it was a better, stiffer kind of cotton. Why did you want me to try this one? I asked as I slipped it over my head, hissing at the sensation, again, of new fabric scrap ing against my shoulders. Well, my mother said, I thought you might like this one.

Why would I like this one? I tried to keep my voice level, but I was awash in irritability, struggling to communicate with words against this current tugging me backward into the deepest, most primi tive and antagonistic parts of my brain that encour aged me to stomp on her foot and run away, scream ing. My mother shrugged and looked at me in the mirror. Because blue is your favorite color?

I blinked, the shirt only half on. What? How could she possibly know that blue was my favorite color? It wasn’t a secret that I kept, but even as I floundered in a mental pool, trying to process this previously undemonstrated intimate knowledge she had of my preferences, she simply reached into her purse to answer a few texts on her work phone. The clacking on her BlackBerry stopped after some minutes, and she looked up at me through the mirror, seeing that I still hadn’t put the shirt on all the way. She tucked her phone back into her purse and then seized the ends of the shirt, dragging it down so it covered my torso properly. What? she asked.

How did you know my favor ite color is blue? I felt dizzy all of a sudden, and grasped at my mother’s hand for balance. I had never told her this before. So who snitched, this thing that she could now wield against me, like she wielded my love for food against me, and my love for beauty, and my despera tion to be loved? I didn’t recognize the look on her face.

You think I don’t know you? she finally said. I’m your mother. Of course I know your favorite color is blue. How…I…

She looked at her phone, then looked back at me. I’m your mother. I know everything about you.

I’m your mother. I’m your mother.

JANE WANG B’24 knows the favorite color of her mother.

As I spent that time with West Rutland, Vermont, USA, it’s hard to get away from the fact that I am from Gurgaon, Haryana, In dia, which isn’t ever going to be the exact same but that’s why it doesn’t hurt to try to make it feel a little more connected.

One of the more boyish things I did as a kid was collect comic books. My main focus were the comic spin-offs of TV I already watched at home: Invader Zim, Adventure Time, sometimes even the occasional X-Men.

Once, my dad (former boy, former comic collector) brought down from the attic a box filled with two differ ent comics: Steven and Idiotland, both by the author Doug Allen. I was thrilled. I had just read The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and couldn’t believe that one of my favorite authors had written two comic series! (My 13-year-old brain mistook cartoonist Doug Allen for novelist Doug Adams, but nevertheless comic reading ensued.)

Idiotland was a little beyond me at the time: a surre alist, plotless jam strip1 prioritizing absurdity and irrev erence above all else. (If you were interested in seeing an overtly feminized rabbit-humanoid hitting a bong, or perhaps a man with dicks for legs emotionally re-learning how to walk, Idiotland is the place for you. At 13, I didn’t think I was ready to move there yet.)

Steven was a little more my speed, a punky, bratty little boy named Steven who hates everything. (Imagine if Bart Simpson wore a white top hat and lived on An gell Street, or if Charlie Brown started listening to Dead Kennedys.) Flipping off the reader, Steven makes it very clear that he does not like you. He hates you, he hates his friends, and he definitely hates Providence. In fact, he doesn’t really like anything, except maybe TV, beer, and music. It is as if Steven walked out of a Black Flag music video and onto Kennedy Plaza, issuing zingy one-liners like: “Eat Paste!,” “I hate you!,” and (my personal favor ite) “no!”

Unlike Steven, I really enjoyed his friends. There was Brock, his sweet—but naive—sidekick, unaware, sincere, and often Steven’s punching bag. There was the tiki-man, the owl-man, the local mailman (I’m sensing a theme). My personal favorite side character was Mr. Rochambeau, the flamboyant, aristocratic poodleman, constantly beg ging Steven to be taken on a walk.

Moving away from the boy, and onto the-man-whodraws-the-boy, Doug Allen is a cartoonist originally from Greenwich, Connecticut, who moved to Providence in 1973 to enroll as an Illustration major at RISD. At RISD, he would go on to create Steven, originally as a recur ring jam strip in the student paper, The RISD Press. Allen would later move the project to Providence’s under ground newspaper, The New Paper, after graduating in 1978. He would continue this strip, Steven of Providence, for the next three decades, even after moving out of The Creative Capital and into Brooklyn. Steven would later go on to be compiled and sold in collections, these editions being the ones my dad bought and read.

Wanting to interview Allen for this project, I first needed to find his email. I tried looking for it through his website; however, that became difficult upon realizing that his website had been hacked several times. First in 2016 (I found these dates using the Wayback machine) by a dropshipping furniture company, and then again in 2018 by a group of poker players from Indonesia. While I may not have found his email on the website, I did leave with an appreciated knowledge of international poker cultures. (Did you know that “PLAYING ONLINE SLOT GAMES WITH REAL MONEY IS AN ATTITUDE”?)

I was eventually able to get in touch with Allen through the incredible connective force of the RISD alumni network (special thanks to Annabeth at RISD). On November 3, Allen graciously agreed to be inter viewed, calling in from his home in New York as I re sponded from my Slater triple.

CM:

CM: Hello. Is this Doug?

DA: Yes, Charlie?

DA: I always had a connection to Providence. My mother and grandmother were painters, and I would visit an aunt in Provi dence off and on when I was a kid, so we were always driving up there. My mother encouraged me to be an artist from an early age; I was an only child, and she was always sticking crayons in my hand to keep me busy. I had a stack of newsprint paper, so I was always drawing from an early age, and I definitely wanted to go to art school, and RISD seemed like the clear cut choice for me. I really fell in love with Providence in 1973; it was so down and out, and it’s such a gritty kind of Rust Belt looking town. So different from where I grew up in Connecticut.

CM: What were the most influential parts of the city? Was there a specific community, or maybe the infra structure?

DA: It was just the look of it. I was a big fan of Edward Hop per’s paintings and that desolate down-and-out New England look. Factory decay, I guess you’d call it. I used to be able to walk around downtown and go into these old factories that were abandoned. There was one called Dorette Incorporated, where I would find tap handles, old plexiglass, every different beer brand buried into the ground. Everything was just inside these open warehouses. You could wander around another factory that made leather cigarettes, cigarette cases, and purs es. There were all these different creations you could just pick up. I still have a cigarette holder made with red leather that I just picked up off the floor. I applied to RISD in 1973. When I got there, there were all these second hand clothing stores, and everyone looked like they were from the ’40s. There was a big music scene playing big band jazz. You could see a roomful of blues playing downtown with Big Joe Turner and Scott Hamilton playing saxophone at the Met Café. Everybody sort of looked like they were Robert Crumb characters. I was in the Illustration department at RISD, and everything I drew kind of looked like a cartoon. My teachers would say, “Oh no! Everything you do looks like a comic.” So I thought why fight it. The RISD paper had a weekly rag called The RISD Press, and my roommate and I did a comic strip series for that in ’74.

CM: Did this comic for The RISD Press bear any resemblance to work you would go on to create later in your career?

How did your relationship with Providence shape what your comics looked like in their early stages?DA: The strip was called the “history of ____”: “history of animals,” “history of people”... etc. It was a jam strip with my roommate. When he lost interest in doing it, I switched to a character from one of my sketchbooks named Steven. I thought, I’m gonna do a punk comic strip with Steven and his friends, like a punk version of Peanuts. And just, I was also a big fan of Pogo, and that was similar to a Peanuts kind of thing where it was just a little group of furry animal friends and they were very political, but all that stuff was over my head at the time.

CM: What was the influence for Steven’s attitude?

DA: Yeah, well, that was part of the era too, because it was the late ’70s, and the whole punk thing was going on. And there was a music scene downtown at Lupo’s.2 You know, these, the Ramones and the Dead Boys played down there, and everyone threw bottles at them. There was also the whole punk scene going on at Brown’s radio station, BRU, playing Elvis Costello and The Clash. It was really part of the era. I was always into the concept that Steven would be this little punk character who hates everything and drinks beer.

CM: I’m wondering about the politics you saw represented in comics, going back to Pogo. What do you see as Steven’s relationship with this?

DA: There wasn’t much politics in Steven other than it was based in Providence: “Steven of Providence.” This was in the Buddy Cianci3 era with all the mob stuff that was going on in Providence. There are also a lot of local references in the comics. I would drive around in my car, and I’d sit in front of one of these iconic landmarks like the Ocean State Theater and draw a picture of it in a sketchbook so that I could put it into the strips the next week. Even when I moved to New York, it was still Steven of Providence. After I graduated from RISD in ’78, Ty Davis from The Providence Journal started The New Paper, which was the local underground free press paper, similar to The Phoenix in Boston and The Village Voice in New York. I started doing a weekly strip for them. They’d have music listings, apartments for rent, classified ads, editorial pieces, comics, and all the advertisements that supported the rest of the publication. They were just stacks of them at all the shops, especially in record stores along Thayer Street.

CM: I’m interested a little bit more about Steven as part of a college publication. Did you have a big readership at RISD? Did you get a lot of interaction with the comic?

DA: I think it wasn’t really big, it was circular. It was kind of the way all those free papers were, with this one being for RISD students and teachers. There were stacks of them around campus, and people really did read articles by their classmates, look at the comics, see the listings and music reviews and things just like any underground paper. But I think for me, I just had the thrill of seeing my strip get printed, and being able to pick up a copy of it and tear out my strip and see how it would look on the page along with all the articles and that kind of thing.

CM: Were there any noticeable changes in Steven as a RISD comic vs. as a Providence comic?

DA: I think mostly just a slow change from when the focus of it opened up to local events in Providence. And then more, it became more national when I moved to New York—the idea was to move to New York, you know, and become an illustrator, which I tried to do for about a month when I sublet an apartment that was owned by a RISD painting teacher who was on sabbatical. I would put on my sport jacket and take my portfolio around to magazines; I think I only got one gig doing a strip for High Times. And then I ran out of money in a month very quickly in New York and had to move home for a while. And then I end ed up moving back to Providence for a few years, because it was easier living up there. And I was playing in bands.

CM: I read about you and Gary Lieb in bands. You did bass for a band, right?

CM: I’m thinking about the two of you working together. Was there a lot of collaboration within the comics scene at the time? Was there an established, networked community?

DA: There were other cartoonists out there doing the same kind of thing. Kaz, Gary Panter, Dan Clowes, who did a comic book called Eightball, Matt Groening. At this time, I was doing a weekly strip called “The Angriest Dog in the World” or something like that. You know, they were all running in these underground newspapers. Sometimes we got together when Gary Lieb was in Chicago; we’d go out to a coffee shop and sit around and draw these jam strips. Did many comics with Dan Clowes and a bunch of other boys. It became national. Gary and I both moved to New York and eventually there were other cartoonists in Brook lyn, in Williamsburg. There definitely was a scene. And then eventually we started having these comic book conventions in Brooklyn, where all these underground cartoonists would show their books and trade things and sell their wares.

CM: Do you still feel connected to any kind of comics world or scene now? Do you read anything? Do you keep up with anything?

DA: Not so much now, I haven’t really followed anything online. I haven’t followed many of the new cartoonists. As soon as all of these underground newspapers started to fold and were replaced by online sources, the fun really went out of being able to see these things get print ed. So after 23 years of doing a weekly strip, I kind of lost interest in it, and around the same time I was running out of ideas for weekly strips.

CM: That’s interesting, what you’re saying about the death of the underground comic with the death of the underground newspaper. I’m also interested in your opinions on graphic novels, as I’ve heard it argued that they are a contributor to the death of the comic strip?

DA: I didn’t really get involved in that whole wave of that change in comics nor make myself available to any of that. Now I’m just one of these old grouchy guys who talks about the old days. But there’s supposed to be a collection of old Steven stuff coming out in a book called Alive and Outside this fall.

CM: Thank you very much for this interview! I’m glad that the RISD alumni email chain could connect us.

DA: Yeah, yeah, that did work. I’m kind of off the grid these days. Since you know, I had a website for a while. People used to complain that there was no contact information. I put it up in 1996, and I never changed it until one day I finally said, “Why am I paying for this?”

CM: There’s like some crazy poker thing on it now.

DA: Oh, really? I haven’t looked it up lately. That’s another little glitch with the Internet. You can never really erase yourself. They sell your domain to some body else or something. It’s weird.

1 A jam strip is a collaborative comic where each page is drawn by a different artist.

2 Lupo’s Heartbreak Hotel: old bar downtown.

3 Mayor of Providence, twice, from 1975-1984, and 1991-2002.

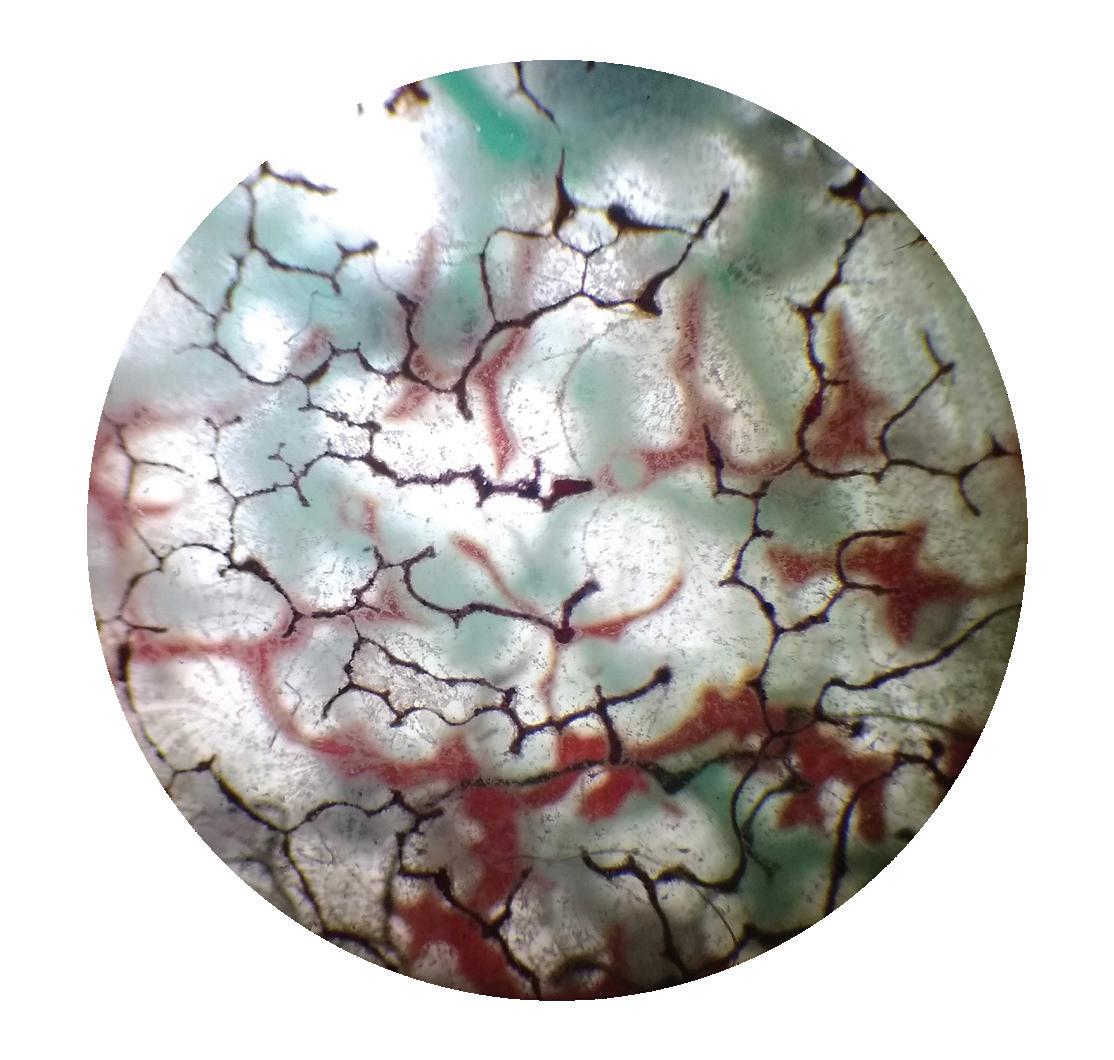

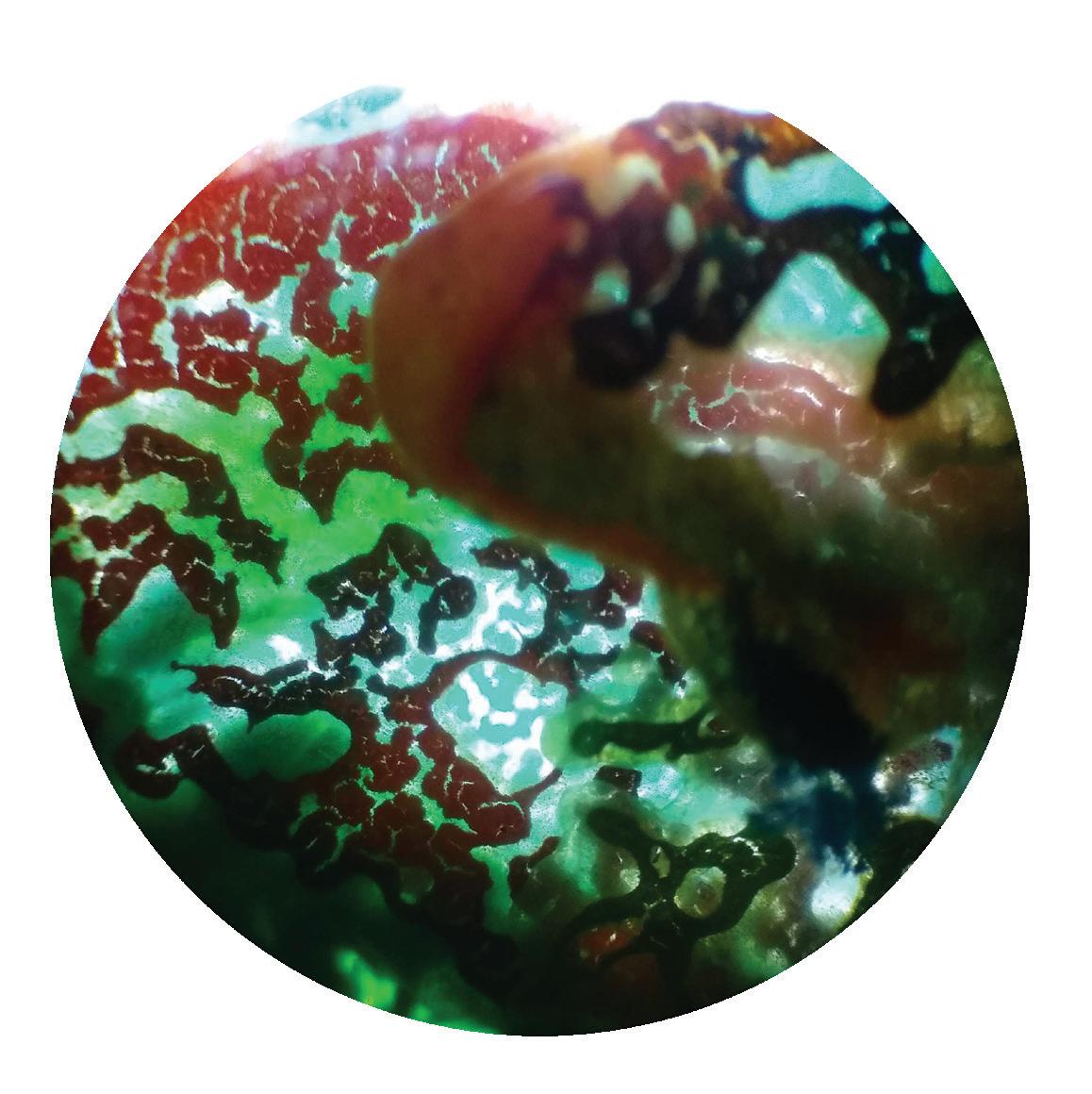

microscope, you can move through each layer as if sinking to the bottom of the sea: the first layers are imbued with color and high resolution, but as you move inward, the picture becomes less visible and obscures. Aside from posing as an imaginative response to the abuse our planet has endured, these micropaintings act as exhi bitions where art and science are engaged in a symbiotic relationship.

Suppose I were to tell you I have been reinvigo rated with wonder, that I fell in love again with the world. Suppose I were to say we became reacquainted amidst a stream of light funneled through a dark barrel and refracted through a glass lens. Suppose I learned just how beautiful ordinary things are when you look at them from a different perspective, when you zoom in past the outer barrier. It is blank at the start. Then you turn the knob slowly and a haze of color appears. Then, a new world opens up to you, exploding as if you are watching a time lapse of a rose blooming. Stooped over the microscope, I am a child experiencing autumn for the first time, stupefied by the burst of warm tones, reawakened by the cool, refreshing breeze.

For some time, I have been creating multi-dimensional micropaintings in response to the effects of human behavior on the environ ment. The first layer placed on the microscope slide is opaque, and then a thin piece of glass—a slide cover—is positioned over top. I continue to mount more paint on these slide covers, adding water to the paint as the stratification builds for translucency and depth. When placed under the

One slide speaks to how methane and plastics are deposited into the air and ocean, how they fill our respiratory systems with toxins and marble the bodies of nonhuman species with malignant growths. Another slide depicts the bleaching of the Great Barrier reef resulting from intemperate fishing and tourism that have compounded the threat of global warming and ocean acidification. As you move through the layers, you are traversing space and time, starting at the present and then diving into the past. The sea is home to an entanglement of anemones, kelp, and tubeworms ensnared by synthetic polymers. Chemicals contained in plastics cast into the ocean interact with these organisms with parasitic intentions. In the first layer of the painting, you are shown how these habitats are presently met with the unwel come guests of radiation, plastics, and fossil fuels, killing species more rapidly than they are renewed. But a deeper submersion into the painting will introduce you to coral colonies as they once were: a colorful metropolis of diverse species braided together in procreative arenas in a balanced, continuous, and natural cycle of living and dying.

My work with microscope slides and paint was inspired by an early microscopist practice of arranging diatoms for the purpose of gener ating fine art. Diatoms are single-celled algae that range from 20–200 microns in length. One hundred diatoms would fit into the size of a comma in normal typeface—size 12, Times

New Roman. In the late 1800s, microscopist J.D. Möller used a single hog’s eyelash glued to a pencil to arrange diatoms in spectacular geometric designs and rectilinear organizations often resembling intricate mandalas. These were constellations of the artistic consciousness, fixated on showcasing beauty for beauty’s sake. These diatom arrangements were frequently exhibited at social gatherings and were said to evoke a profound sense of awe in the viewer, a reawakened appreciation for the diversity of lifeforms populating the Earth that are beyond our field of vision.

More recently, diatoms have been imple mented as a tool to map a history of climate change. When looking at a diatom through the microscope, you are transported to a distant Earth, an unfamiliar Earth, an Earth of inter connected processes and ecosystems, generating new life forms across space and time. Diatoms are ancestors of the sea, capturing moments of Earth’s climate history. Changes in the combi nation of fresh and sea water—induced by rises in sea levels and water management—can be hypothesized through the evaluation of diatom remains. Because they are preserved in layered sediment that contain parts of the ecosystem in which they once lived, diatoms function as a portal to a previous version of the Earth, allowing us to improve our understanding of the planet’s evolution.

While Möller and I have taken the micro scopic approach to access smaller dimensions— preserving Earth’s smaller beauties in intricate arrangements or painting microscope slides to call attention to the widespread impacts of climate change—artist Lee Hunter has been zooming out, projecting into the future. Through this macroscopic lens, Hunter envisions a future where humans have reached the climax of envi ronmental destruction and face consequences that impede both everyday life and the ability to carry out scientific endeavors such as space travel. In Hunter’s fictional future, space travel has been terminated as Earth can no longer supply the necessary resources to support cosmic

explorations.

I first encountered Hunter’s world-building project Cosmogenesis at a museum in my home town of Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Cosmogenesis, a collection of art objects Hunter has accumu lated since 2014, explores humanity’s relation ship with nature as well as the narrowing gap between apocalyptic fiction and the grim reality of climate change. Interested in challenging our ability to think creatively about the future, Hunter focuses on the ways in which specula tive fiction forges a space where we can critique the society we live in and dream up new, viable futures.

Its narrative framework is based upon the following premise: It is 2245 and the United States’ coasts have been submerged due to rising sea levels. What was once the country’s capital is now a lost city home to fish and sea turtles, barnacles and algae fastened to the pillars of the White House. An archivist is invited to the new Library of Congress to translate artifacts from Transdimensional Travel Groups (TTGs), organizations grounded in Western occult practices and coded language to convey methods to travel parallel dimensions for the acquisition of resources no longer found on Earth. These groups banded together between 2040–2145 and were secretive with their methodologies for parallel travel, so information was shared orally, with no written records left behind.

In walking through the exhibit, I was reminded of the Welsh concept of hiraeth, a homesickness for the lost places of your past to which you cannot return. As an archive of objects that contain the memory of a bygone place, Cosmogenesis highlights the common attempt to preserve a historical moment and the complications that arise in the process of translating the visual into a readable narrative. Among other things, I was curious about the function of Hunter’s archivist as a symbol for the desire to memorialize our achievements, to keep a timeline of human progress. In an interview with the College Hill Independent, Hunter stated that the character of the archivist represents their interest in the tradition of interpretation, where meaning can be lost and made. This “sort of slippage … seemed to be a fun spot to inhabit,” they stated. The archive is comprised of photographs that serve to reproduce TTG training manuals, ceramic figures and vessels, stone sculptures, handmade mirrors, needle point, and found objects which reference portals, temples, and markets used and established by TTGs. They come together as part of a system that reveals the secret methods of parallel travel used by TTGs to discover the key to a new

Hunter mentioned that around the time they began the project, a quote by Fredric Jameson had been circulating among political and cultural theorists and philosophers: “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is the end of capitalism.” Taking a stance firmly against the apoc alyptic and dystopian thinking perpetuated by the media and popular culture, Hunter envisions a future where capitalism has fallen and the Earth remains standing, wounded but in the process of regenerating. While Hunter’s exhibit serves as a commen tary on our current conservation efforts, it also seeks to unravel neoliberal capitalism and explore its detri mental global impacts. “The relationship between climate change and capitalism is intrinsic … One of those systems is ignoring that the other system is collapsing and continuing to push on even though we are in the sixth extinction. We are already in the middle of collapse. We are collapsing now.”

The premise for Hunter’s project arose from an article that argued humans have reached the first peak of maximum technological advance ment and another is projected to occur in about 70 years, after which it is believed that Earth will no longer have the resources to achieve interstellar travel, which has historically allowed us the opportunity to understand our place in the universe. The people who possess power and access to capital are those that are capable of forwarding the space exploration agenda; however Hunter finds it difficult to imagine that these individuals have a humanitarian objective. “There doesn’t seem to be any chance that they are not trying to treat space as another area to colonize as the rhetoric about space is manifest destiny-based. Why are we going to mismanage the place that we live to the point that we must flee to space to survive. The travel cults ended up being another way to access other pockets of the universe.”

For Hunter, humans have been given an amazing biosphere to call home. We are stew ards of this planet and finding a new plane tary body to manipulate into satisfying our biological needs should not be our quick fix for ensuring the survival of our species after we have exhausted the Earth. “The landscapes in Cosmogenesis have giant dead zones in it, they can’t grow vegetables, they have to do everything in bio-splicing labs. Most of the seed banks were destroyed so there are not many biological species remaining that humans can use as a food resource. They are working on remedia tion for these large swaths of dead zones,” but there is a limit to how successful such attempts at mending the planet are; the more injured our planet is, the more fruitless ventures to preserve become. So much effort is allocated to preserving artifacts of human knowledge, but we remain negligent when it comes to protecting the planet’s diverse inhabitants from endangerment.

The invention of the microphotograph in 1852 by John Benjamin Dancer proved to be a useful tool in the preservation of unique and rare documents; in present day, microphoto graphs are made in response to the fear that products of human thought will be lost due to paper’s vulnerability to time. The inexpensive wood-pulp paper used for newspapers rapidly disintegrates, and even paper considered to be good quality degrades within a few decades. As a contingency plan, books and periodicals that have become unusable and fragile have been transferred onto a microscopic film format. Libraries are able to store large quantities of information in a small space due to the size of these microphotographs. The original docu ments are photographed onto a film reel and then projected onto a larger screen for viewing. Microfilm copies allow libraries to frequently access the material of rare and aged manu scripts without causing damage to the original texts through handling.

We should be handling our planet with the same degree of care. We should devote more effort, however tedious, to preserving what is left before we, like Hunter’s TTGs, have to find new means to locate materials no longer abundant on Earth, or grow vegetation using seeds kept in biobanks. We are of nature, not apart from nature, not above nature. So how can we imagine new and viable futures in which humans respect and live in harmony with the flora and fauna populating this planet? What would the future look like if we brought other organisms into the democracy governing Earth? What if we alter our thinking about who dictates the planet’s future? What if we all— human and nonhuman species alike—assume responsibility for our actions and actively work toward making amends whether it be through the creation of art objects or planting a commu nity garden?

The morning after my interview with Lee Hunter, I am sitting in my kitchen watching the light cast the shadow of branches and leaves onto the windowsill. I think about how distant I am from nature in this room, how it seeks entry through shadows. I pry open the window hoping the scent of nature will filter into this congested space, this kitchen that looks out upon a groomed landscape, one that keeps the growth of grass at bay.

Like Hunter, I am interested in the various tools and frameworks for seeing and thus being in the world, zooming in and zooming out across time and space. In a time when the climate crisis has reached immeasurable magnitudes, it has become difficult to decide where to begin making amends. Perhaps the first steps to address the endan germent of our planet should be taken through artistic means. Perhaps an urgency to preserve Earth’s seen and unseen beauty will arise if we are presented with opportunities to creatively interact with nature’s offerings from multiple perspectives.

NICOLE KONECKE B’23.5 recommends the pear and honey poptart from Plant City.

The Industrial National Bank Building, known as the “Superman” building, looms over Kennedy Plaza, the heart of Providence’s under staffed public transportation system on which many Rhode Islanders rely. After nine years of vacancy, the Superman building is now at the center of a political firestorm: a planned redevel opment of the building, greenlit by city officials, is facing backlash from housing advocates over its lavish use of public funds and its lack of affordable housing.

Rhode Islanders’ right to shelter has not been a governmental priority for a long time— the state was home to the largest housing crisis in New England even before COVID-19. The pandemic brought a new level of economic devastation to the entire country, leaving housing insecurity at an all-time high. According to the Rhode Island Homeless Management and Information System, at least 42 people experi encing homelessness died in the past year. As we move into a brutal winter, there are at least 461 Rhode Islanders currently living on the streets.

And around 22 percent of renters are facing eviction.

But rather than build more affordable housing, government officials voted on October 17 to fund a redevelopment that will convert the Superman building into luxury condos and business offices. While politicians and union leaders praised the project for its economic and developmental foresight, other politicians, housing justice advocates, and low-income residents are adamant that it will aggravate the existing housing crisis. These concerns have been ignored by the building’s redevelopment approval process.

In an interview with the College Hill Independent, Democratic State Senator Samuel Bell called the project “a net loss to the city—it’s a net loss in terms of tax revenue, economic development, affordable housing, historic preser vation, and it’s a net loss in terms of downtown vitality.”

“A lot of this plan is about luring rich people in, and pushing poor people out of the city,” Terri Wright, a leader at Direct Action for Rights and Equality (DARE), said at the September 1 “Superman Can’t Save Us” protest. “They take our money when we come down here and

shop, they take our dollars, but we can’t afford to live down here.” In addition to condemning the Superman project, Wright and other activ ists reiterated their longstanding demands for the city to put public funds toward immediate shelter for homeless people. State officials recently unveiled a new $166 million investment in affordable housing—but this new housing will not be available for at least six months, and expensive Superman units will count as ‘afford able,’ according to UpriseRI

In mid-October the City Council approved the usage of millions of dollars in public funds for the Superman redevelopment. These millions include: $10 million taken from the city’s Housing Trust Fund, which is intended to fund housing for its lowest-income residents; a $5 million direct appropriation in the city budget; and a $29 million, 30-year tax break for High Rock Development, the building’s out-of-state developer since 2008.

Advocates have called for at least 30 percent of the building’s units to be permanently afford able to low-income households. Low-income households earn under 30 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI), or $20,300/year for an individual and $29,000/year for a four-person household. This demand has been ignored. High Rock Development instead plans to allocate 20 percent of the new lofts as ‘affordable’ units,

with prices ranging from $1,384 to $2,076 a month. Dwayne Keys, president of the South Providence Neighborhood Association, told the College Hill Independent that labeling these units ‘affordable’ is “blatantly disrespectful,” given that they are affordable only for residents making 80–120 percent of the AMI.