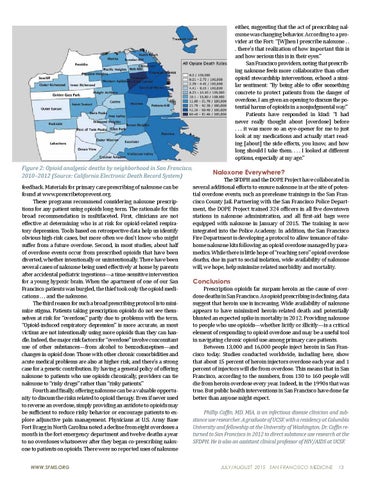

Figure 2: Opioid analgesic deaths by neighborhood in San Francisco, 2010–2012 (Source: California Electronic Death Record System) feedback. Materials for primary care prescribing of naloxone can be found at www.prescribetoprevent.org. These programs recommend considering naloxone prescriptions for any patient using opioids long-term. The rationale for this broad recommendation is multifaceted. First, clinicians are not effective at determining who is at risk for opioid-related respiratory depression. Tools based on retrospective data help us identify obvious high-risk cases, but more often we don’t know who might suffer from a future overdose. Second, in most studies, about half of overdose events occur from prescribed opioids that have been diverted, whether intentionally or unintentionally. There have been several cases of naloxone being used effectively at home by parents after accidental pediatric ingestions—a time-sensitive intervention for a young hypoxic brain. When the apartment of one of our San Francisco patients was burgled, the thief took only the opioid medications . . . and the naloxone. The third reason for such a broad prescribing protocol is to minimize stigma. Patients taking prescription opioids do not see themselves at risk for “overdose,” partly due to problems with the term. “Opioid-induced respiratory depression” is more accurate, as most victims are not intentionally using more opioids than they can handle. Indeed, the major risk factors for “overdose” involve concomitant use of other substances—from alcohol to benzodiazepines—and changes in opioid dose. Those with other chronic comorbidities and acute medical problems are also at higher risk, and there’s a strong case for a genetic contribution. By having a general policy of offering naloxone to patients who use opioids chronically, providers can tie naloxone to “risky drugs” rather than “risky patients.” Fourth and finally, offering naloxone can be a valuable opportunity to discuss the risks related to opioid therapy. Even if never used to reverse an overdose, simply providing an antidote to opioids may be sufficient to reduce risky behavior or encourage patients to explore adjunctive pain management. Physicians at U.S. Army Base Fort Bragg in North Carolina noted a decline from eight overdoses a month in the fort emergency department and twelve deaths a year to no overdoses whatsoever after they began co-prescribing naloxone to patients on opioids. There were no reported uses of naloxone WWW.SFMS.ORG

either, suggesting that the act of prescribing naloxone was changing behavior. According to a provider at the Fort: “[W]hen I prescribe naloxone . . . there’s that realization of how important this is and how serious this is in their eyes.” San Francisco providers, noting that prescribing naloxone feels more collaborative than other opioid stewardship interventions, echoed a similar sentiment: “By being able to offer something concrete to protect patients from the danger of overdose, I am given an opening to discuss the potential harms of opioids in a nonjudgmental way.” Patients have responded in kind: “I had never really thought about [overdose] before . . . it was more so an eye-opener for me to just look at my medications and actually start reading [about] the side effects, you know, and how long should I take them. . . . I looked at different options, especially at my age.”

Naloxone Everywhere?

The SFDPH and the DOPE Project have collaborated in several additional efforts to ensure naloxone is at the site of potential overdose events, such as prerelease trainings in the San Francisco County Jail. Partnering with the San Francisco Police Department, the DOPE Project trained 324 officers in all five downtown stations in naloxone administration, and all first-aid bags were equipped with naloxone in January of 2015. The training is now integrated into the Police Academy. In addition, the San Francisco Fire Department is developing a protocol to allow issuance of takehome naloxone kits following an opioid overdose managed by paramedics. While there is little hope of “reaching zero” opioid overdose deaths, due in part to social isolation, wide availability of naloxone will, we hope, help minimize related morbidity and mortality.

Conclusions

Prescription opioids far surpass heroin as the cause of overdose deaths in San Francisco. As opioid prescribing is declining, data suggest that heroin use is increasing. Wide availability of naloxone appears to have minimized heroin-related death and potentially blunted an expected spike in mortality in 2012. Providing naloxone to people who use opioids—whether licitly or illicitly—is a critical element of responding to opioid overdose and may be a useful tool in navigating chronic opioid use among primary care patients. Between 13,000 and 16,000 people inject heroin in San Francisco today. Studies conducted worldwide, including here, show that about 15 percent of heroin injectors overdose each year and 1 percent of injectors will die from overdose. This means that in San Francisco, according to the numbers, from 130 to 160 people will die from heroin overdose every year. Indeed, in the 1990s that was true. But public health interventions in San Francisco have done far better than anyone might expect. Phillip Coffin, MD, MIA, is an infectious disease clinician and substance use researcher. A graduate of UCSF, with a residency at Columbia University and fellowship at the University of Washington, Dr. Coffin returned to San Francisco in 2012 to direct substance use research at the SFDPH. He is also an assistant clinical professor of HIV/AIDS at UCSF.

JULY/AUGUST 2015 SAN FRANCISCO MEDICINE

13