Mapping

June

zero deforestation certification and private programs for soybeans farming in Brazil

2023

1 Contents PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................................................ 2 OBJECTIVE ........................................................................................................................................... 3 BRAZILIAN ENVIRONMENTAL LEGISLATION ............................................................................................ 3 OVERVIEW OF NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL LEGISLATION 6 LAW 6.938/81 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY 6 CONAMA RESOLUTION 237/97 ENVIRONMENTAL LICENSING 8 LAW 9.985/2000 NATIONAL SYSTEM OF NATURE CONSERVATION UNITS 8 LAW 12.651/12 NEW FOREST CODE ................................................................................................. 10 MAIN CERTIFICATION STANDARDS ....................................................................................................... 14 BENCHMARKING OF SUSTAINABILITY CERTIFICATIONS 17 ROUND TABLE ON RESPONSIBLE SOY – RTRS 17 SOYBEAN MORATORY 23 GREEN PROTOCOL FOR GRAINS FROM PARÁ 31 INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION PERFORMANCE STANDARD ........................................... 37 PRODES SYSTEM - DEFORESTATION MONITORING .............................................................................. 42 FIELD OBSERVATIONS – ILLEGAL MINING IN AMAZONAS ................................................................ 44 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS .................................................................................................................. 46 This document was requested and afforded by The Kingdom of The Netherlands and developed by Peterson Consulting. The information contained in this document is responsibility of the authors of the consultation sources and does not reflect the opinion of the organization.

PRESENTATION

This document lists the main sustainability certification standards present in Brazilian agribusiness. The information collected comes from the documents of the different standards, pointing out specific issues involving the theme “free of deforestation”, while analysing the requirements involving the environment theme, the deadlines for modification of native vegetation accepted and the conditions imposed to achieve the sustainability standard in the vegetation and nature conservation requirement and consecutively achieve certification.

For the development of this work, sustainability standards were analyzed, directly involving the approach to the theme of deforestation, or even the deadline for accepting the conversion of forests and other biomes and forms of native vegetation into agriculture, so that they could later become converted and vegetated areas. The obligation to have a management system applied for reforestation and maintenance of native fauna and flora was also raised. When required, the need to prepare an action plan for vegetation recovery was also informed.

The national environmental legislation was summarized in order to contextualize its basic structure, while pointing out the main points identified within the current legislation. The approach is limited to the list of the main national laws applicable to agribusiness, the breakdown to the respective executing agencies with a broad and non-operational interpretation. In this way, enterprises of interest can consult this information as support for tactical reconnaissance and development of appropriate action plans. It will also allow better targeting to obtain technical information in greater depth.

They are addressed:

● Diagnosis of existing certifications and private programs

o national legislation

o Main sustainability certification standards applicable to soy

o Applicability comments of the EU RED II Renewable Energy Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council in relation to deforestation

● Documentation

o Interpretation of criteria related to deforestation in certification programs.

o Certification Scope Overview

o List of applicable sustainability certifications

o General considerations for Dutch companies

2

OBJECTIVE

This document aims to meet the demand for identifying relevant aspects related to deforestation in the certification standards used in soy producing farms in Brazil.

BRAZILIAN ENVIRONMENTAL LEGISLATION

Brazilian environmental legislation comprises a series of laws, decrees, resolutions and norms that aim to ensure the protection of the country's environment and natural resources. For an introduction to the topic, an overview of public bodies and the main applicable laws is presented below.

GOVERNMENT AND ITS INSTITUTIONS

Matters related to the environment are deliberated and managed through environmental bodies. Each agency has its area of expertise. At the center is the Ministry of the Environment (MMA). Through its performance the other bodies were created for specific purposes. The list below lists the main federal agencies, and points out the state and municipal ones that operate in smaller territories to ensure compliance with the law.

Ministry of the Environment (MMA)– central organ

National Council for the Environment (CONAMA)– advisory and deliberative body

Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBIO)– executing agency

Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA)– executing agency

State Environmental Agencies– executive branch

Municipal Environmental Bodies– local executing agency

3

For a broad understanding, Brazilian legislation addresses the issue in its Federal Constitution of 1988 as the natural environment.

Federal Constitution Article 225

§1º III- “define,inallunitsoftheFederation,territorialspacesandtheircomponents tobespeciallyprotected,withalterationanddeletionpermittedonlybylaw,anyuse thatcompromisestheintegrityoftheattributesthatjustifytheirprotectionbeing prohibited.”

§4- “TheBrazilianAmazonForest,theAtlanticForest,theSerradoMar,theMato GrossoPantanalandtheCoastalZonearenationalheritage,andtheirusewillbe made,inaccordancewiththelaw,underconditionsthatensurethepreservation environment,includingtheuseofnaturalresources.”

Based on these definitions, the following laws were formulated to create mechanisms for the protection and conservation of natural resources, such as biodiversity, areas relevant to nature conservation and their main ecological functions. They also regulate obligations and responsibilities regarding the use and interventions on natural resources and the potential impacts generated through economic activities.

Considering the objective of this study, the laws of the agencies related to the environment that are directly related to the sustainability performance standards for agribusiness were listed below. The structure of sustainability standards commonly considers the following aspects, among others:

4

Legal compliance – assessing whether the enterprise complies with national laws within its scope of activity.

Identification of socio-environmental risks – determining through the management of risks in the scope of social relations (labor, stakeholders, traditional communities, among others) and the environment observed arising from or related to the economic activity carried out.

Protection and conservation of areas of biological value, conservation, carbon stock or biodiversity protection – being areas that must be protected for the conservation of natural species and for the fulfilment of ecological functions directly related to it. The protection of native vegetation, the maintenance of hydrological cycles, the preservation of the fauna, flora and biota of the ecological system, and the sequestration and storage of carbon can be highlighted.

GoodAgriculturalPractices– through soil conservation, proper management of water resources, correct and technically based use of pesticides and fertilizers, and waste management.

Following this line above, as those directly related to the environment, the legislations below were identified and the points of synergy were identified.

● Law 6.938/1981 National Environmental Policy

● CONAMA Resolution 01/1986 Environmental Impact Study

● CONAMA Resolution 237/1997 Environmental Licensing

● Law 9.605/1998 Crimes and Environmental Infractions

● Law 9.985/2000 National System of Nature Conservation Units

● Decree 6.514/2008 Infractions and Administrative Sanctions

● Decree 7.830/2012 SICAR and PRA

● Law 12.651/2012 New Forest Code

● Decree 8.235/2014 PRA and PMAB

5

OVERVIEW OF NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL LEGISLATION

The following are a superficial view of the main points that affect agricultural activities in the national territory. Articles directly linked to agricultural activities and their interaction with natural resources were highlighted, or even normative observations to operationalize the enterprise.

LAW 6.938/81 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY

Law 6938 of August 31, 1981 provides for the national environmental policy. It is the most important law hierarchically and regulates activities related to the environment. It establishes the National Environmental System and assigns responsibilities and powers to environmental agencies.

This law creates, among other functions, the National Council for the Environment, the instruments for establishing environmental quality standards, assessing the environmental impact, licensing effectively or potentially polluting activities, and disciplinary or compensatory penalties when measures necessary for the preservation or correction of environmental degradation are not met.

For this study, the Economic Ecological Zoning, the Environmental Impact Assessment and the Environmental Impact Report were highlighted, and the responsibility for the environmental impacts generated by the activity.

Art. 9 The following are instruments of the National Environmental Policy: Ecological-EconomicZoning(ZEE)– regulated by Decree 4,297/2002 is, according to Article 2 of Law 6,938/1981 “the instrument for organizing the territory to be compulsorily followed in the implementation of plans, works and public and private activities, establishes measures and standards of environmental protection aimed at ensuring the quality of the environment, water resources and soil and the conservation of biodiversity, guaranteeing sustainable development and improving the living conditions of the population”.

In short, the state executing agencies must draw up a mapping of their resources and direction of possible activities according to the desired territory. To this end, agricultural activities such as soy cultivation must be included in the permitted zones.

6

THE ASSESSMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS

An Environmental Impact Study (EIA) must be carried out, followed by an Environmental Impact Report (RIMA). This study must contain a diagnosis of the area of influence, analysis of the impact and its alternatives, proposal of measures to mitigate negative impacts, preparation of a follow-up program, and monitoring of positive and negative impacts, according to CONAMA Resolution 01/ 86 EIA RIMA.

For all agricultural activities there are legal risks of intervention in the environment. It is important to point out that according to article 14, I, paragraph 1, it is defined that:

“withoutpreventingtheapplicationofthepenaltiesprovidedforinthisarticle,the polluterisobliged,regardlessoftheexistenceoffault,toindemnifyandrepairthe damagecausedtotheenvironmentandtothirdparties,affectedbyhisactivity.”

Article 22 establishes that penalties for legal entities and individuals may vary.

Legal person: they can be fines, restrictions on rights and provision of services to the community.

Physical person: they may be partial or total suspension of activities, temporary interdiction of establishment, work or activity, or prohibition of contracting with the Government, or obtaining subsidy, grant or donation from it.

Obligation propter rem – Superior Court of Justice jurisprudence of 08/26/2013 establishes the responsibility of the current owner for the existing environmental damage in the area. In case of transfer of the rural property, the new owner assumes full responsibility for repairs. Therefore, the direct or indirect responsibility is attributed to the owner of the land for compensation and repair of the damage caused. The acquisition of land with irregularities before the environmental agencies is transferred to the landowner, even if it is prior to his possession.

7

CONAMA RESOLUTION 237/97 ENVIRONMENTAL LICENSING

Certain activities require environmental licensing for installation and operation. CONAMA Resolution 237 regulates licensing and establishes responsibility for environmental agencies according to their characteristics.

Art. 1. I - EnvironmentalLicensing:“administrativeprocedurebywhichthe competentenvironmentalagencylicensesthelocation,installation,expansionand operationofundertakingsandactivitiesthatuseenvironmentalresources, consideredeffectivelyorpotentiallypollutingorthosethat,inanyway,may cause environmentaldegradation,consideringthelegalprovisionsandregulatoryand technicalstandardsapplicabletothecase.”

The resolution regulates obtaining the Environmental License and Environmental Authorization to carry out the activity and must be carried out in advance. This instrument can be obtained through the executing agency, according to the potential polluting impact.

• National Level - IBAMA

• State level – state agency linked to the environment

• Municipal level – municipal environment department

The license takes place at three levels:

• Prior License - LP (inPortuguese,LicençaPrévia)

• Installation License - LI (inPortuguese,LicençaInstalação)

• Operating License - LO (valid for 4 years), (inPortuguese,LicençaOperação)

Licenses may require additional conditions for obtaining and maintaining them, which must be complied with as agreed with the executing agency.

LAW 9.985/2000 NATIONAL SYSTEM OF NATURE CONSERVATION UNITS

The National System of Nature Conservation Units (SNUC) defines territories with special characteristics, designated for the protection of their resources and their natural characteristics with a special administration regime. The purpose of these territories may be for strict protection of natural species, to provide environments for observation and research, to maintain traditional populations, among other ways to

8

guarantee the maintenance of local natural characteristics. Article 2 defines Conservation Units as:

I – “Conservationunit:territorialspaceanditsenvironmentalresources,including jurisdictionalwaters,withrelevantnaturalcharacteristics,legallyestablishedby theGovernment(bylawordecree),withconservationobjectivesanddefinedlimits, underaspecialadministrationregime,towhichappropriatesafeguardsapply.”

Unlike the protected territories that will be addressed in the Forest Code, specifically the APP and RL which are territories provided for by law, the Conservation Units are instituted or created by the public power by law or specific decree for each territory.

There are two main groups:

Group 1 - Full Protection Conservation Units (indirect use)

● Ecological Station – ESEC (inPortugues,EstaçãoEcológica)

● Biological Reserve – REBIO (inPortugues, Reserva Biológica)

● National Park – PN (inPortugues, Parque Nacional)

● Natural Monument – MONAT (inPortugues, Monumento Natural)

● Wildlife Refuge – RVS (inPortugues, Refúgio da Vida Silvestre)

These territories do not allow damage, consumption or collection and even access can be regulated.

Group 2 - Sustainable Use Conservation Units

● Environmental Protection Area – APA (inPortugues,Área de Proteção Ambiental)

● Area of Relevant Ecological Interest – ARIE (in Portugues, Área de Relevante Interesse Ecológico)

● National Forest – FLONA (inPortugues, Floresta Nacional)

● Extractive Reserve – RESEX (inPortugues, Reserva Extrativista)

● Fauna Reserve – REFAU (inPortugues, Reserva de Fauna)

● Sustainable Development Reserve – RDS (in Portugues, Reserva de Desenvolvimento Sustentável)

● Private Natural Heritage Reserve – RPPN (in Portugues, Reserva Particular do Patrimônio Natural)

These territories allow the use of their resources through authorization and regulation through the executing environmental agency. In other words, tourist exploitation, the settlement of traditional communities, the extraction of forest products, among other forms of regulated exploitation, are possible. Another

9

important feature of these territories that are related to the Forestry Code and agricultural activities are the Buffer Zone and the Ecological Corridors.

Art. 2 VIII -Buffer zone (purpose of restricting human activities so as not to affect the ecological activities of the area)

Art. 2 IX –Ecological Corridors (interconnection between protected areas).

The first consists of areas outside the Conservation Unit in which human intervention must respect criteria so as not to affect the quality of protected areas. Finally, the ecological corridors that connect protected areas with each other, such as two Conservation Units, or even between Legal Reserves or Permanent Protection Areas provided for in the Forestry Code.

LAW 12.651/12 NEW FOREST CODE

The Forest Code, or the New Forest Code is, in practical terms, the law with which agricultural activities are most closely related, as it directly addresses the protection and conservation of natural resources that are important for ecological functions, especially the hydrological cycles. The regulated situations of environmental protection areas are defined as the Permanent Protection Area (APP) and the Legal Reserve (RL). The relevant aspects for rural activity are presented below

PERMANENT PROTECTION AREA

Especially vulnerable areas are classified as Permanent Protection Areas – APP ((in Portuguese,ÁreadeProteçãoPermanente). As per Article 3 II, the definition of APP is:

“Permanent Preservation Area - APP:protectedarea,coveredornotbynative vegetation,withtheenvironmentalfunctionofpreservingwaterresources, landscape,geologicalstabilityandbiodiversity,facilitatingthegeneflowoffauna andflora,protectingthesoilandensurethewell-beingofhumanpopulations.”

10

The types of permanent protection areas are according to their function, and can be classified as:

Riparian Vegetation – they are marginal strips of perennial or intermittent watercourses, such as rivers. It is mainly understood as riparian vegetation. These have a minimum conservation strip width, considering the measurement from the edge of the watercourse gutter.

The areas around natural lakes and ponds in rural areas are according to the water surface area:

Area < 20 ha – 50 m

Area = > 20 ha – 100 m

Other areas characterized as Permanent Protection Area:

Water reservoir -in the case of artificial reservoirs, the APP area must be determined in the environmental licensing and defined by the competent body for licensing the project.

Water springs– must have their area conserved around a radius of 50 m.

Slopes –in situations where the terrain has a slope greater than 45 degrees, the entire area must be protected.

Tops of areas– including the edges of plateaus or plateaus, the tops of hills, hills, mountains and mountains, with a minimum height of 100 m and an average slope greater than 25 degrees, and areas at altitudes greater than 1,800 m.

Wetlands– in paths, the marginal strip, in horizontal projection, with a minimum width of 50 m, starting from the permanently marshy and swampy space.

Weirs and water mirrors- with an area of less than 1 ha do not require an APP.

11

Minimum APP width in watercourses Width of the water course (m) Width per edge (m) < 10 30 10 - 50 50 50 – 200 100 200 – 600 200 > 600 500

RESPONSIBILITY

The cut-off date for suppression of native vegetation according to the Forest Code is July 22, 2008. All interventions after this date oblige the property owner to recompose the native vegetation and carry out maintenance until its restoration.

LEGAL RESERVE

The Legal Reserve area (RL) is the portion of the total rural property that must have its native vegetation obligatorily conserved for environmental preservation and for the maintenance of natural resources. According to Article 3 III the definition is:

Legal reserve:“area located within a rural property or possession, delimited under the terms of art. 12, with the function of ensuring the sustainable economic use of the natural resources of the rural property, assisting the conservation and rehabilitation of ecological processes and promoting the conservation of biodiversity, as well as the shelter and protection of wild fauna and native flora ;”

The size of the RL area varies according to the biome in which the rural property is inserted. First, it is necessary to define the territory of the Amazon biome, which, for legal purposes, is defined in Article 3 I:

Legal Amazon:“the States of Acre, Pará, Amazonas, Roraima, Rondônia, Amapá and Mato Grosso and the regions located north of the 13th parallel S, of the States of Tocantins and Goiás, and west of the meridian of 44° W, of the State of Maranhão;”

Within this territory, the percentage of mandatory RL that must be conserved is:

a) 80% in the property located in forest areas;

b) 35% on property located in a cerrado area;

c) 20% on property located in the Campos Gerais area;

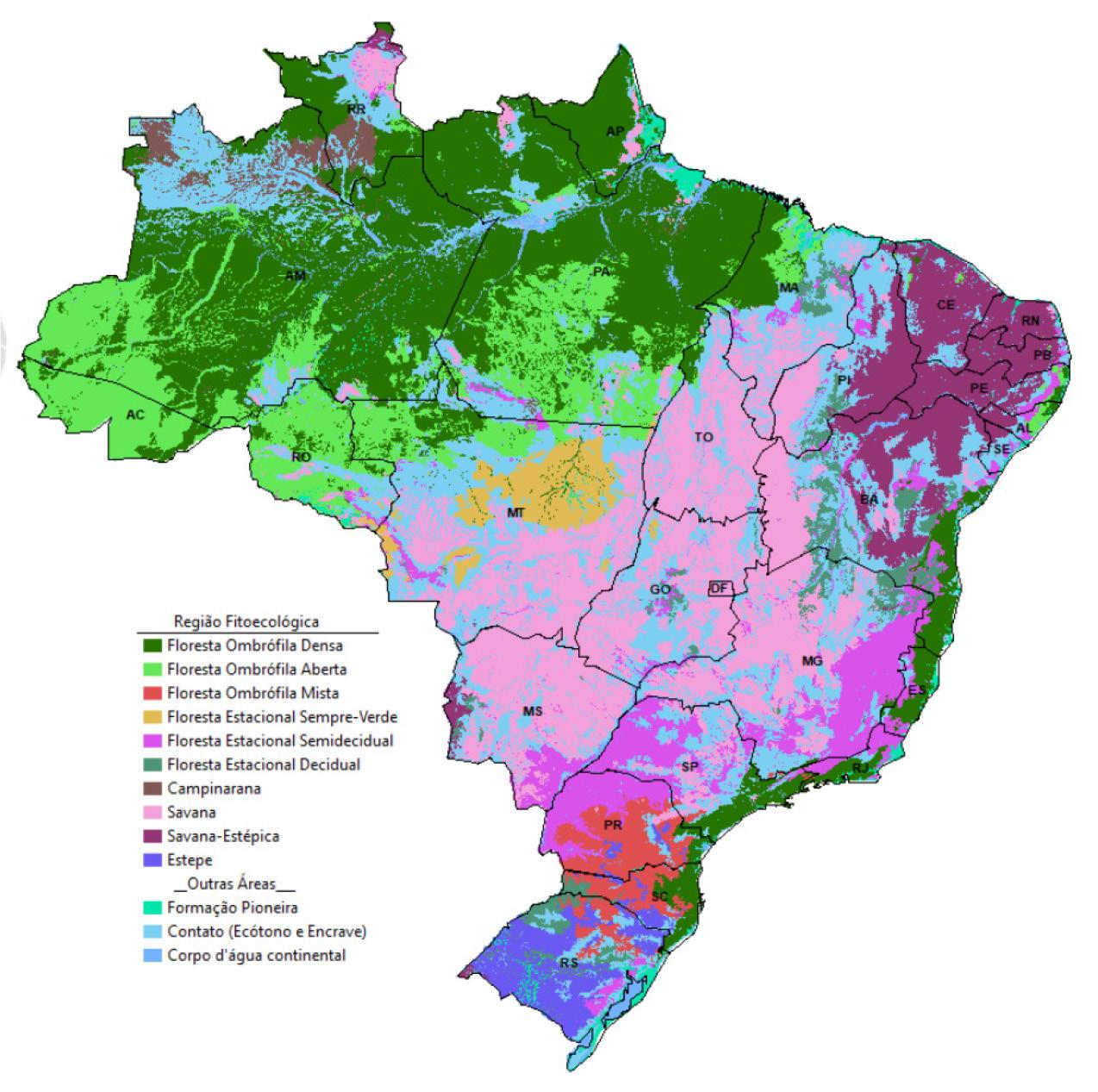

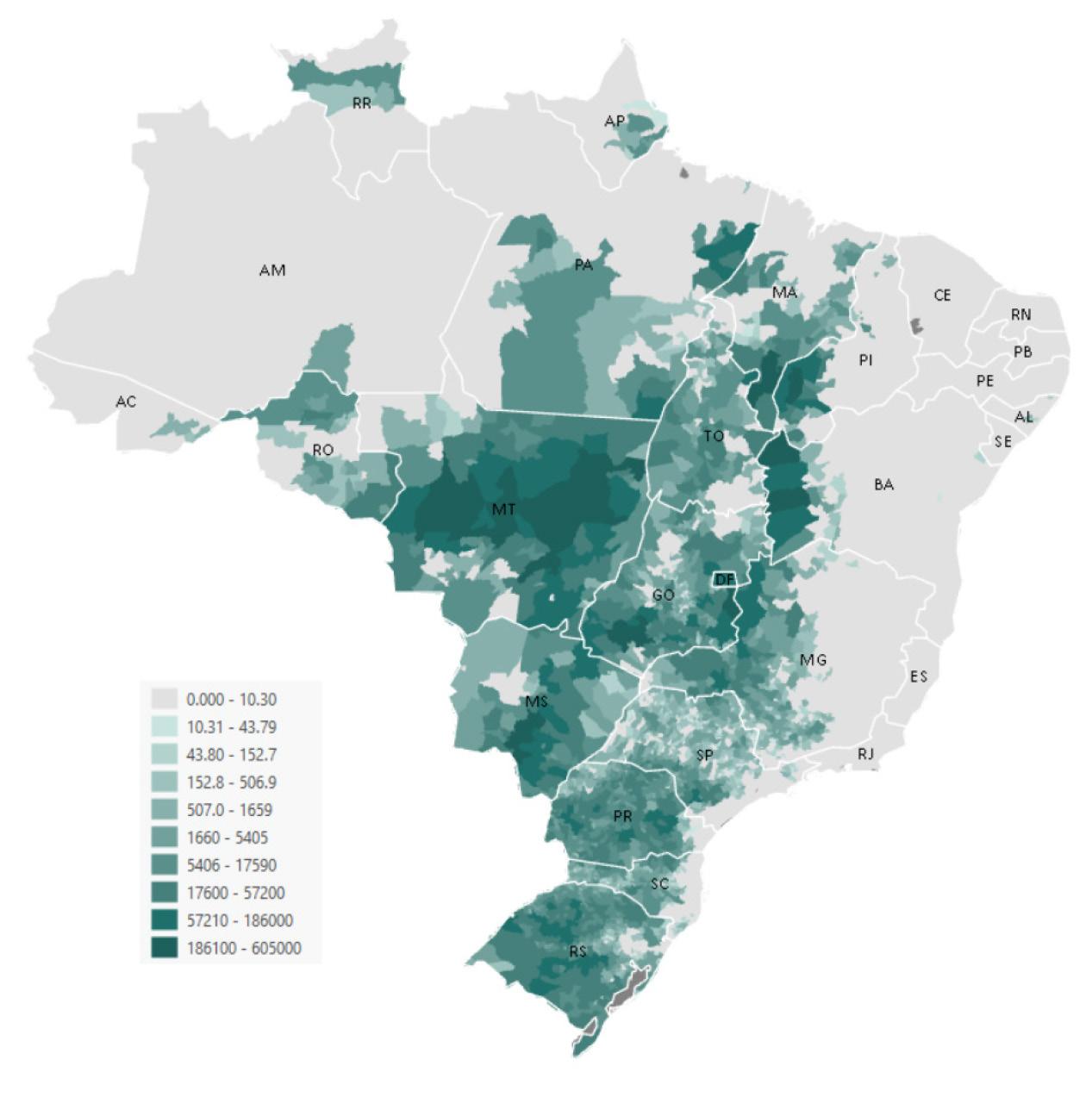

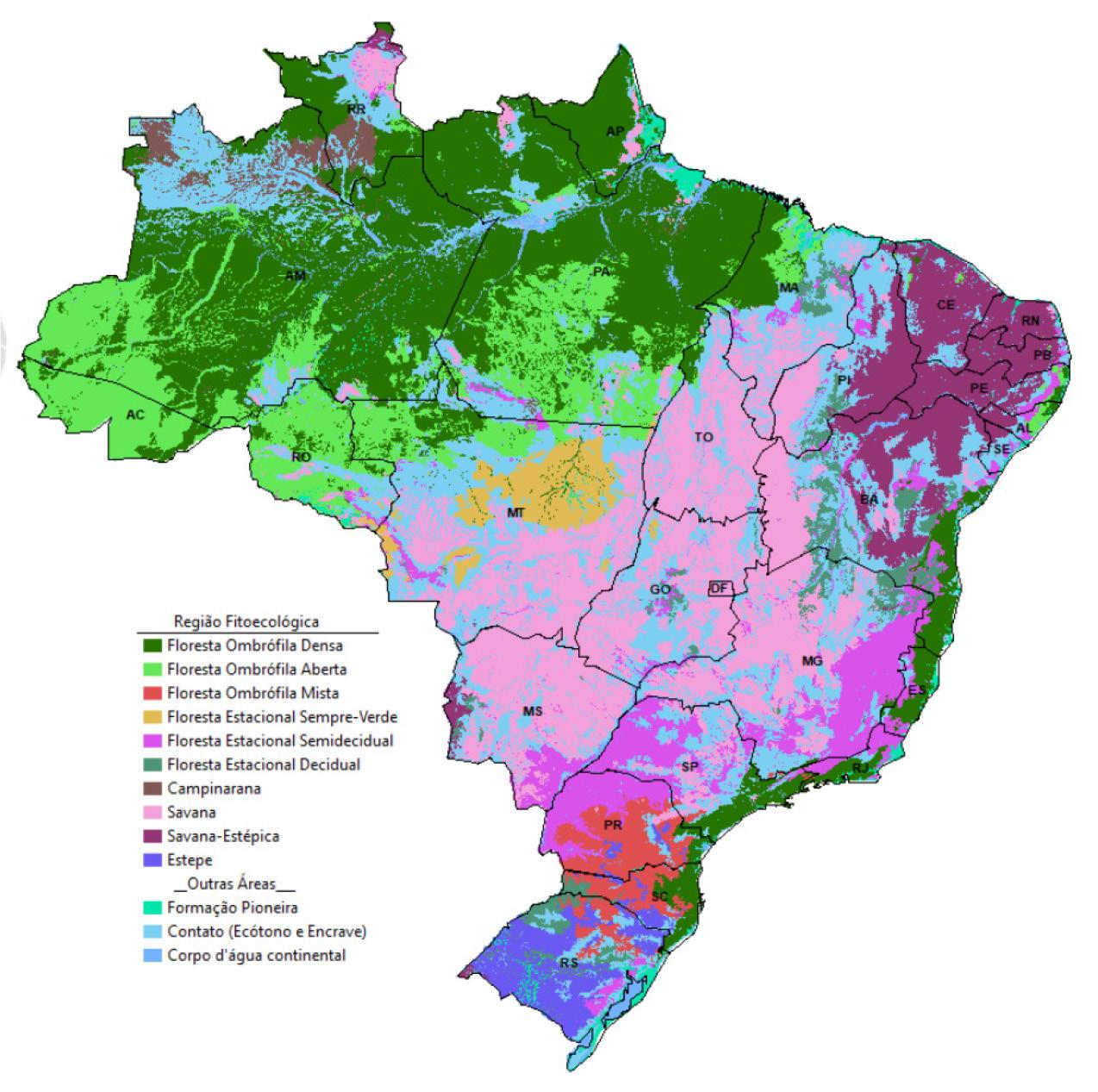

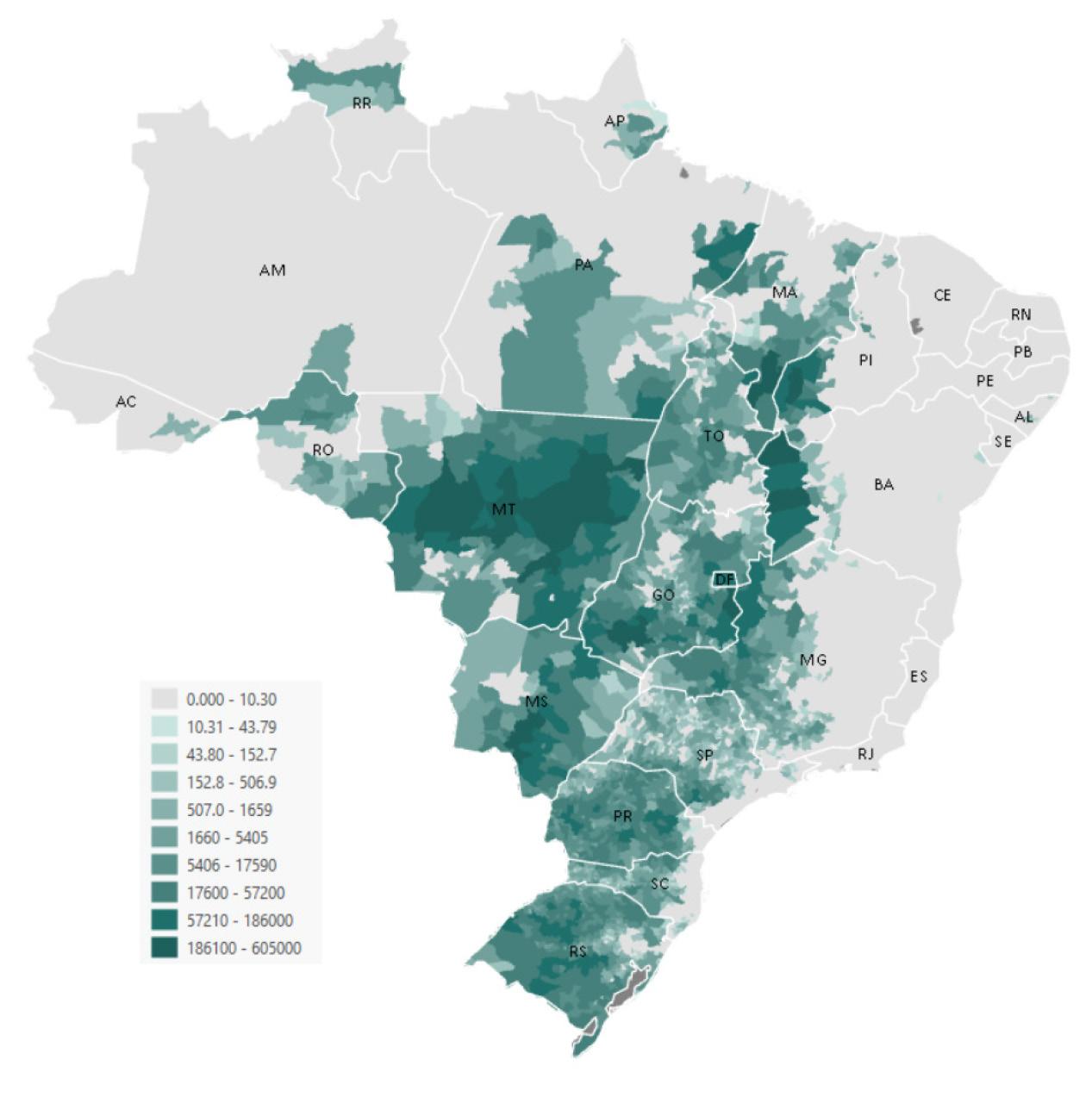

For all the territory located in the other regions of the country, the RL must be composed of 20% of the total area of the rural property. The image on the left shows the Brazilian federal states for a better understanding of their territory. On the right, the national biomes.

12

Source: Researchgate

Source: Researchgate

In certain situations, the RL can be included in the APP provided that:

I – does not imply the conversion of new areas, that is, it cannot convert a reserve area to compose a new one in another place of the rural property.

II – the area is already conserved or in the process of conservation.

III – the inclusion of the APP in the RL has been requested through a Rural Environmental Registry (CAR), still in the operationalization process.

13

MAIN CERTIFICATION STANDARDS

The main certification standards identified for the soy chain and with public information made available by the accreditation bodies were listed. Of these, issues of deforestation, compliance with local legislation, environmental protection and conservation criteria, socio-environmental risk management and good agricultural practices directly related to the protection of native vegetation and protected areas were considered.

The certification scopes evaluated were:

● RTRS

● I am Moratorium

● AgroPlus

● GreenProtocolofParastategovernment

● IFC

● PrivatePrograms*(ADM,COFCO,CefetraCRS)

*Private programs were structurally analyzed to determine compliance with deforestation practices, following the confidentiality limits determined by the holders, when applicable.

ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY

For the development of comparative analyses between the practices of the different sustainability certification standards, the Methodology for the Food and Agriculture Benchmark proposed by the World Bank Alliance was used, which uses the description of the topic, the desired indicator, the elements and key resources. This analysis was adapted for the purpose of this study. The result of this assessment was succinctly transcribed into four main themes, as described below. A score was assigned according to the requirement covering the topic with more indicators, always on a scale from zero to four.

Legal compliance. This indicator assesses the requirement for legal compliance with national legislation in the certification protocol, or in the audit guidance document. The purpose of this requirement is to cover possible aspects in the certification standard that may be less restrictive than the deforestation criteria established in Brazilian legislation.

14

Socio-environmental risk management at stakeholder level. This requirement evaluates the existence of indicators for identifying and managing socioenvironmental risks, governance and relationship with interested parties.

Deforestation control. Deforestation criteria, level of compliance with national legislation, with the European directive for renewable energy and the most restrictive level of prohibition of deforestation.

Good Agricultural Practices. This criterion assesses the existence of compliance with good agricultural practices in terms of conservation of the soil, water sources and biodiversity, as well as the management of pesticides and contaminating residues.

The table below briefly presents the score used for analysis and determination of benchmarking indicators.

15

ASSESSED REQUIREMENTS PUNCTUATION LEGAL COMPLIANCE Not required 0 Requires legal compliance regarding the environment 1 Requires legal compliance regarding the environment and human rights 2 Requires legal compliance regarding environment, human and business rights 3 Requires legal compliance with environmental, human rights, business, and EU market requirements 4 MANAGEMENT OF SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS AT STAKEHOLDER LEVEL Not required 0 Requires the identification and management of environmental risks 1 Requires identification and management of environmental and social risks 2 Requires identification and management of environmental, social and governance risks 3 Requires the identification and management of stakeholder environmental, social and governance risks and establishes communication channels 4 DEFORESTATION CONTROL Does not include deforestation indicator 0 Determinescriteriaof environmental preservation 1 Determines criteria and deadline for deforestation in line with the Forestry Code 2 Determines criteria and deadline for deforestation aligned with EU RED II for the European market 3 Determines zero deforestation criteria, which is more restrictive than national and market legislation 4 GOOD AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES Not required 0 Includes soil conservation indicator 1 Includes soil and watershed conservation indicator 2 Includes soil conservation indicator, water sources and biodiversity protection (fauna and flora) 3 Includes soil, water sources and biodiversity conservation indicator, as well as pesticide and contaminant residue management 4

Comparing the different aspects between the protocols, it is possible to highlight the RTRS, which was used as a reference in this study, as the most complete certification standard in terms of protection against deforestation.

The Soy Moratorium and the Green Protocol for Grains of Pará have a similar structure, the main difference being that the first is voluntary, that is, participants are audited in relation to their management system and in relation to compliance with national legislation. regarding deforestation. The second is linked to the complaints and notes made by the Public Ministry.

The IFC (International Finance Corporation) Performance Standard was included from the point of view of credit lines and investment and financing funds that has been taking shape with the advancement of the sustainability theme. Several financial institutions adopt the IFC principles to assess the risks of socio-environmental impact on their clients' activities. Institutions began to link social and environmental indicators as a compliance goal linked to the financial project, and deforestation control has often been found among them.

Finally, private programs were analyzed and compared. These have not had information published in detail due to disclosure restrictions. To this end, the structure of these programs within the scope of compliance with environmental legislation in relation to deforestation was evaluated, as well as other possible aspects that directly impact deforestation, or even the existence of additional criteria. In short, when present, the approach of these programs requires compliance with national legislation. The chart below lists the main themes comparing, among the protocols, the level of aspects analyzed and their scope. It is important to emphasize that this study is for the purpose of interpreting the criteria and indicators of the different protocols and does not reflect the opinion of the authors in relation to the protocols and their documents.

16

BENCHMARKING OF SUSTAINABILITY CERTIFICATIONS

ROUND TABLE ON RESPONSIBLE SOY – RTRS

BASE DOCUMENT

Certification Standard: RTRS Standard for Responsible Soy Production. Version 4.0.

CONTEXTUALIZATION

The Round Table on Responsible Soy – RTRS is a certification standard with a strong presence in the soy production chain. The standard is an initiative of the International Association for Responsible Soy that began its development in 2004, with approval and implementation between 2010 and 2011. Its information is published and made available for free consultation. As far as this study is concerned, only in 2016 did it include the obligation of zero deforestation and zero conversion in the environmental protection areas of soy-producing farms. As informed by the RTRS, in 2020, 4,437,276 tons of grains were certified, covering 1,261,133 hectares of area, of which 563,047 hectares are protected areas in 9,536 certified farms. All information can be consulted through the website https://responsiblesoy.org/

The RTRS mission is to promote the growth of production, trade, and use of responsible soy through cooperation with actors in and around the soy value chain, from production to consumption in an open dialogue with the participants, including producers, suppliers, manufacturers, retailers, financial institutions, civil society organizations and other relevant actors.

The objectives of the RTRS are:

1. RTRS refrains from profit making.

2. The objectives of the RTRS are to promote the growth of production, trade and use of responsible soy through cooperation with stakeholders relevant to the soy value chain, from production to consumption, in an open dialogue with stakeholders, including producers, suppliers, manufacturers, retailers, financial institutions, civil society organizations and other relevant stakeholders.

3. Responsible soy is economically viable, socially beneficial, and environmentally appropriate. In particular, the RTRS should facilitate a global dialogue on responsible soy:

17

● as a forum to discuss and develop solutions, with the aim of reaching consensus, on the main economic, social and environmental impacts of soy among various stakeholders;

● communicating issues relating to the production, processing, trade and responsible use of soy in commercial products, and consumption to a wide range of global stakeholders;

● as a forum to develop and promote definitions of responsible soy production, processing, trade and consumption with criteria that address economic, social and environmental issues incorporated in the RTRS Standards through its Principles, Criteria, Indicators and Verification and Accreditation System;

● mobilizing participants for the multi-stakeholder process;

● organizing conferences and technical workshops;

● as a recognized international forum that controls the status of responsible soy production, processing, trade and consumption.

4. The RTRS is a transparent and open organization that unites stakeholders, making every effort to disseminate and promote its processes to the public and share its results and conclusions developed in the RTRS Standards through its Principles, Criteria, Indicators and System of Verification and Accreditation with members and non-members.

5. It is fundamental to the integrity, credibility and continued progress of the RTRS that each member sincerely supports, implements and monitors this multistakeholder global process that promotes the responsible production, processing, trade and consumption of soy.

To determine deforestation characteristics, the RTRS uses macroscale maps in which it classifies areas into the following categories:

Category 1 red –critical areas for biodiversity, not allowing the conversion of native vegetation. Not certifiable, except legal proof prior to May 2009.

Category 2 yellow –high conservation value area (HCVA) conversion is not allowed after June 2016.

Category 3 dark green –enough legislation to control the expansion, being areas of agricultural importance, except RL, not being allowed to convert after June 2016.

Category 4 light green –areas already used for agricultural exploitation, with no remaining native vegetation, except RL, with conversion not allowed after June 2016.

2, 3 and 4 legally converted by June 2016 are certifiable.

18

A minimum standard for the plan to implement or monitor native vegetation and wildlife is established and must address:

1. Identification of native vegetation and wildlife on the farm.

2. Indicators and baseline status of native vegetation and wildlife.

3. Measures to preserve native vegetation and wild life.

4. Monitoring and adaptive management.

The chart below illustrates compliance with the four principles used in the benchmarking analysis among sustainability standards. This graphic highlights that the RTRS is the most complete and comprehensive standard regarding deforestation. According to the RTRS map, certain situations include zero deforestation, with verification carried out by the producer before the certification audit to assess the eligibility of his farm. The review mechanism and criteria are transparent and accessible to all stakeholders.

LEGAL COMPLIANCE

The RTRS requires compliance with local legislation, such as labor legislation, legislation applicable to commercial relations, land and water use rights, and environmental issues more broadly. It additionally has modules for traceability and volume control of certified products through a chain of custody system.

MANAGEMENT OF SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS AT STAKEHOLDER LEVEL

The RTRS is comprehensive in terms of stakeholder relationships. The standard requires the implementation and maintenance of accessible communication channels for the communities surrounding the rural property.

19

Additionally, the implementation of an environmental management system is required to cover the risks related to environmental preservation and the impacts arising from agricultural activities. Risks must be managed in a participatory manner, together with stakeholders and the community.

GOOD AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES

The RTRS standard has strict criteria of good agricultural practices in relation to the management and conservation of soil, water resources, including the conservation of riparian vegetation. The practices extend to ecological processes and environmental preservation through the correct use of agrochemicals and the mitigation of the risk of pollution. This aspect includes waste management.

DEFORESTATION CONTROL Compliance with national legislation (forest code)

The RTRS defines deforestation dates according to the classification and zoning of the areas mentioned above. In this sense, whichever is more restrictive must be complied with. The maximum level determines zero deforestation, not allowing the farm to be eligible for certification.

COMPLIANCE WITH EU RED II

The RTRS has a specific module for complying with EU RED II, when the scope of certification includes trade with the European Union for the purpose of supplying raw material for biofuels.

CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING HCV

Areas of High Conservation Value (HCV) are, according to the RTRS, biological, ecological, social or cultural areas of exceptional or critical importance. The standard classifies six types of HCV, namely:

HCV1 - concentrations of biological diversity. It includes endemic, rare, threatened or endangered species, regardless of geographic range.

HCV2 - intact forest landscapes, large forest ecosystems and ecosystem mosaics that contain viable populations of most naturally occurring species in natural patterns of distribution and abundance.

HCV3 - rare, threatened or endangered habitats, refuges or ecosystems.

20

HCV4 - basic ecosystem services in a critical situation, including protection of water intakes and erosion control of vulnerable soils and slopes.

HCV5 - key locations and resources to meet the basic needs of local communities or indigenous peoples (livelihoods, health, nutrition, water, etc.) identified through engagement with such communities or indigenous peoples.

HCV6 - sites, resources, habitats and landscapes of global or national cultural, archaeological or historical importance and/or of critical cultural, ecological, economic or religious/sacred importance to the traditional cultural identity of local communities or indigenous peoples, identified through engagement with local communities or indigenous peoples.

Definition of deforestation in the standard

The RTRS defines deforestation as “loss of natural forest resulting from:

i) conversiontoagricultureorothernon-forestlanduse;

ii)

iii)

ii)conversiontotreeplanting;or

iii)severeandsustaineddegradation.

It further defines thatthe severedegradationofscenarioiiiconstitutesdeforestation evenifthelandisnotsubsequentlyusedfornon-forestrypurposes.Lossofnatural forestthatmeetsthisdefinitionisconsidereddeforestation,regardlessofitslegality”.

Transparency Mechanism

The RTRS annually publishes reports and results on its website, as well as the audit result, hiding sensitive information that could expose people.

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

The RTRS standard is the only voluntary certification program present in the market, open to the market through which the producer can decide who to sell his production to, that is, there is no market restriction to sell his crop.

RTRS certification encourages access to soy markets that are more restrictive in terms of deforestation and can encourage producers through market entry and additional credit payments on the volume of sustainable soy produced, that is, the volume of certified material.

The RTRS is the most restrictive program regarding deforestation. Farms wishing to become certified are required to eligibility, and the criteria are defined in their sustainability standard. Additionally, the farm can be certified in compliance with the

21

requirements of European legislation for raw materials from agriculture and the legal aspects of eligibility of the area converted into agriculture after January 2008.

The RTRS has a transparent mechanism for publicizing the results of certified properties. Interested buyers can assess their customers' compliance with the standard's indicators, ensuring that only eligible farms have been certified.

An important aspect is that, following its criteria, small grouped producers can be group certified, minimally requiring that there be a common management system to monitor compliance with its requirements.

One factor that may be limiting is the cost of investment and maintenance of certification for small producers.

Deforestation criteria can be restrictive for the entry of rural producers, which excludes them from the deforestation monitoring system that certified farms must comply with. In this sense, those who are not eligible or those who fail to comply with the deforestation requirements are not certified and are no longer covered by the surveillance audits that directly contribute to the reduction of deforestation.

22

SOYBEAN MORATORY

BASE DOCUMENT

2021/2022 Soybean Moratorium Protocol

Soybean Moratorium - 14th Report, 2021/2022 Crop

CONTEXTUALIZATION

Established in 2006, the Soy Moratorium began with the need to meet the growing demand to eliminate the conversion of forests in the Amazon biome to soy crops. The initiative stemmed from a position taken by the Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries – ABIOVE (in Portuguese, AssociaçãoBrasileiradasIndústriasdeÓleos Vegetais) and the Brazilian Association of Cereal Exporters - ANEC (in Portuguese, Associação Brasileira dos Exportadores de Cereais) in relation to growing market pressure and concern for the Brazilian reputation in the face of the issue of deforestation in the international market.

The Soy Moratorium takes place through the adoption of a supplier management mechanism which the companies (traders) signatories to the moratorium must implement. Signatories must be associated with ABIOVE and/or ANEC. This management system includes information on deforestation carried out by a specific working group, and verification of an exclusion list of suppliers involved in work analogous to slavery. To ensure compliance with the requirements, a third-party audit is carried out through the hiring of a certification body that assesses the soy supplier management system implemented in each trader, the analysis of eligibility for inclusion of this supplier, and the due controls for the purchase and sale of sustainable soy (soy within the scope of Soy Moratorium certification).

The monitoring of deforestation in the Amazon biome is carried out through the collection of satellite images comparing, through superimposition, images of the year 2008 based on the date established by the forest code with images of the current crop year. The deadline for converting forests into arable land determined by Brazilian legislation through the Forestry Code is July 22, 2008. The moratorium follows the legal date for evaluating the eligibility of productive areas that supply soy to traders.

The images of the scope areas are analysed comparing the vegetation cover variation in both. The analysis is carried out by a company called Agrosatélite, formed by professionals from the National Institute for Space Research – INPE (inPortuguese , InstitutoNacionaldePesquisasEspaciais), signatory of the Soy Moratorium, through a technical team called Grupo de Trabalho da Soja – GTS (in free translation, soy work group), a team that is related to the management of the Soy Moratorium. Next,

23

information from the PRODES system and data made available through the Agrosatélite are analyzed, together with information obtained from the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples – FUNAI (In Portuguese, Fundação Nacionaldos Povos Indígenas), the Ministry of the Environment, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics – IBGE (in Portuguese, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística) and the Instituto National Council for Colonization and Agrarian Reform –INCRA (inPortuguese,InstitutoNacionaldeColonizaçãoeReformaAgrária).

The scope of the Soy Moratorium for eligibility of traders' suppliers are private rural properties with a total area of more than 25 hectares and in municipalities with cultivated soy area greater than 5,000 hectares. That is, the sum of all farms included in the municipality must be greater than 5,000 hectares. These municipalities must be located within the legal territory of the Amazon biome. It should be noted that the areas delimited for settlement of agrarian reform, indigenous territory and nature conservation units are not monitored.

The monitored scope area corresponds to 5.85 million hectares (2021/2022 harvest) distributed in 109 municipalities. These municipalities correspond to 97.9% of the soy planted in the biome, with the remaining 2.1% distributed in another 92 municipalities. The figure below outlines the location of the monitored municipalities that meet the criteria of the Soy Moratorium.

Source: SOYBEAN MORATORY – 14TH YEAR REPORT.

Amazonia boundaries

State boundaries

Municipal boundaries Soy 2020/21

24

It should be noted that in situations where only part of the municipality is located in the biome, only the area within the biome was considered. municipalities partially located in the biome, only the area located within it was computed. The area outside the Amazon biome is not included in the scope. Also, according to information from the Moratorium management, the average expansion of soybeans in the biome is 324,000 hectares per year, considering the start of monitoring in the 2007/2008 harvests. Annually, ABIOVE publishes reports with integrated harvest results. The document presents the results obtained through satellite monitoring of the scope areas and makes comparisons in relation to the total deforestation informed through the PRODES system in the Amazon biome. The figure below gives an overview of land use in the territory of the biome, according to the Moratorium.

Source: SOYBEAN MORATORY – 14TH YEAR REPORT.

Deforestations

Pasture, secondary vegetation

Soy in compliance with Soy Moratorium

Others (water, non-forestry vegetation, rock outcrop, etc.)

Primary forest

Soy not compliance with Soy Moratorium

As mentioned above, the scope of the audit for the Soy Moratorium considers three essential requirements for compliance with the norm, and the signatories undertake not to commercialize, acquire and finance soy that is cultivated in deforested areas within the Amazon biome after 22 July 2008 (date defined by the Forestry Code), areas that appear on the list of areas embargoed by IBAMA for deforestation and soy suppliers included in the list of work analogous to slavery.

25

Land Cover Use in the Amazon Biome 2020

Verification of compliance with these requirements is carried out at the signatory companies that buy the soy, and not directly at the rural producers. Buyers establish purchase contracts with their suppliers in their management system. These contracts include clauses specifying the need to meet the requirements of the Soy Moratorium. The trader's management system must describe the organization's internal processes, including means of training its personnel, internal audits, control of product volume and productivity (productive capacity of the farm in order to reduce the risk of cross-buying), method of identification and blocking the purchase of irregular suppliers, as in the case of being included in an IBAMA list, or identifying the existence of work analogous to slavery.

A third-party audit must be conducted annually to verify compliance with the Soy Moratorium. This is carried out by a certification body hired by the signatory company. The audit takes place on the quality of the management system, on the analysis of images of the supplying farms and the risk of deforestation and on-site inspections. Depending on the risk, the audit can be conducted completely remotely. The signatory company may purchase soy from intermediary suppliers. These must be covered in the scope of the audit to mitigate the risk of acquiring soy from non-compliant areas. The audit process is ultimately evaluated by the technical committee. It is your responsibility to evaluate and validate the audit process and correct potential flaws in its conduction and in the final report. If there are non-conformities, an action plan must be prepared following the criteria of the Soy Moratorium. At the end, a report should be published containing the summary of the audit findings. Information considered confidential because it is sensitive to the customer and its suppliers will be omitted.

26

ORGANIZATION NAME TYPE ORGANIZATION NAME TYPE ABIOVE Associations GAVILON Companies ANEC Associations SODRUGESTVO Companies ADM Companies IMCOPA Companies AGREX do Brasil Companies LDC Companies AGRIBRASIL Companies NEW AGRI Companies AMAGGI Companies OLAM GRAINS Companies AGRICULTURAL ALVORADA Companies SINACRO Companies BUNGE Companies VITERRA Companies CARGILL Companies EARTH INNOVATION INSTITUTE Civil

CARAMURU

GREENPEACE Civil

CHS Companies IMAFLOR Civil

COFCO INTL Companies IPAM AMAZONIA Civil society CJ SELECT Companies THE NATURE CONSERVANCY Civil society CJ INTERNATIONAL BRAZIL Companies WWF BRAZIL Civil

CUTRALE TRADING Companies BANK OF BRAZIL Government ENGELHART Companies INPE Government FIAGRILE Companies

society

Companies

society

society

society

The Soja Moratorium has a platform called Soja na Linha that publishes information on the Moratorium. Additionally, ABIOVE has recently published a report entitled Geospatial Analysis of the Expansion of Soy in the Cerrado Biome 2000-2021 with analysis data on the evolution of the soy cultivation area in this biome across the Brazilian states. The document is available for consultation through the linkhttps://abiove.org.br/publicacoes/analise-geoespacial-da-expansao-da-sojano-bioma-cerrado-2000-2021/.

The chart below illustrates compliance with the four principles used in the benchmarking analysis among sustainability standards.

LEGAL COMPLIANCE

The Soy Moratorium requires the soy-buying member to verify the legal constitution of the soy supplier and its intermediaries, as well as its inscription on the slave labor exclusion list. It also verifies legal compliance with regard to deforestation and legal provisions with regard to the forest code. However, it does not assess legal compliance with other requirements.

MANAGEMENT OF SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS AT STAKEHOLDER LEVEL

The Soy Moratorium does not establish mechanisms for socio-environmental management and relationship with stakeholders.

GOOD AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES

The Soy Moratorium does not establish good agricultural practices.

27

DEFORESTATION CONTROL

Compliance with national legislation (forest code)

The Soy Moratorium follows the main Brazilian legislation for the protection of forests, the forest code as a reference for compliance. The certification scope areas are analyzed based on the cut-off date established in the legislation.

COMPLIANCE WITH EU RED II

The Soy Moratorium has a cut-off date that does not meet EU RED II regulations. The European directive establishes the date of January 1, 2008, while the Brazilian legislation determines the deadline of July 22, 2008. Although the criteria for converting forests and areas of high biodiversity value or carbon stock are similar to national legislation, the standard is not in line with European legislation.

Considerations regarding HCV

Areas of high conservation value (HCV) are territories covered by the forestry code. All territories defined by legislation are treated equally in terms of the need for protection and the prohibition of deforestation. Territories such as native forests or other biodiversity conservation areas can be encompassed through the National System of Nature Conservation Units, the SNUC.

Definition of deforestation in the standard

The Soy Moratorium does not clearly define deforestation; however, it follows the definition of current local legislation, in particular the Forestry Code. Because it is an automated detection system, it recognizes deforested areas only over 25 ha and in municipalities with soy area greater than 5,000 ha within the Amazon biome.

Transparency Mechanism

The Soy Moratorium publishes the results of audits through a crop report containing data on deforestation carried out by soy producers in the Amazon biome, according to its own evaluation criteria. Information on signatory companies or their suppliers is not disclosed.

28

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

The Soy Moratorium uses an intelligent system to monitor deforested areas to ensure that the products do not come from deforested areas within the Amazon biome. This deforestation considers areas deforested in accordance with national legislation. In this sense, the limit of the current Forest Code is 80% of the Legal Reserve, added to the Permanent Protection Areas when applicable. However, the legislation provides that rural properties in municipalities with up to 50% of existing deforestation may be exempt from the obligation to comply with the recovery of the Legal Reserve in 80% of the rural property. The moratorium, although it presents an indicator of 2.1% of unmonitored area, does not guarantee that rural properties with an area of less than 25 hectares do not have an impact on deforestation.

Soy expansion informed by the Moratorium management was 5.85 million hectares. This area corresponds to soy grown within the legally permitted area. It should be noted that situations where soybean areas in the municipality are less than 5,000 hectares are not monitored, and also the total areas of indigenous lands, land reform areas and areas in nature conservation units (SNUC). The survey of deforestation in these situations can contribute to deforestation in the biome, without the Soy Moratorium contributing to its control.

The Soy Moratorium contributes significantly with statistical and spatial information for the analysis of deforestation, following legal criteria. The annual publication of the crop year report includes data analysis and interpretation carried out by your GTS. There is a certain influence on the expansion of soy area, which contributes to the reduction of trade in unsustainable products.

The signatories involved in the report have a reputation for issues related to environmental preservation. They are appointed as representatives of civil society Earth Innovation Institute, Imaflora, WWF Brazil, IPAM Amazonia, Greenpeace and The Nature Conservancy. Several companies in the Brazilian agribusiness commodity sector participate in the moratorium, with a direct interest in the monitoring result. The document contributes to mitigating the reputational risk of soy agribusiness in the Amazon biome.

The Soy Moratorium does not prevent deforestation in the Amazon biome, but acts to discourage the market through trade sanctions, which reduce sales options for producers whose rural properties are not compliant. Considering that, according to the report, currently 97.5% of the soy cultivation area used complies with the legislation because it is located in open areas, that is, deforested before 2008, there is an influence on deforestation through the entry barrier to the market.

29

SOURCES FOR CONSULTATION

ABIOVE: https://abiove.org.br/

ANEC:https://anec.com.br/

INPE: http://inpe.br/

PRODES: http://www.obt.inpe.br/OBT/assuntos/programas/amazonia/prodes

Soy on Track: https://www.soyontrack.org/

CCCA:https://climatecrimeanalysis.org/

30

GREEN PROTOCOL FOR GRAINS FROM PARÁ

BASE DOCUMENT

Term of Reference for Audit 2021/2022

CONTEXTUALIZATION

The Green Protocol for Grains of Pará – PVG (inPortuguese,ProtocoloVerdedeGrãos do Pará), or simply the Green Protocol, aims to promote the development of agricultural activities in the Amazon biome, without prejudice to compliance with environmental legislation, especially the forest code. The PVG was established in 2014 through the Federal Public Ministry and the State Government of Pará in conjunction with the state and municipal government, trade associations, unions, the private sector and rural producers. The PVG has a management committee made up of its own signatories. The objectives of the PVG are:

● Ensuring compliance with the sustainability criteria of the most demanding markets;

● Establish grain purchasing procedures that ensure legal and sustainable origin;

● Strengthen the CAR as a tool for environmental control and land use planning;

● Ensuring legal security for the grain production chain;

● Strengthen the private environmental governance of soybeans in the state of Pará;

● Assist companies in the traceability of sustainable products;

● Provide transparency and credibility through independent auditing.

In this way, the PVG establishes means to guarantee legal compliance in relation to deforestation, while organizing the soy production chain in a traceable way that can be submitted to a third-party audit to guarantee its compliance.

The state of Pará has a territory of 1,245,870.798 km², being one of the largest states in the world in terms of territory. A significant part of the Legal Amazon is inserted in its territory. Within this territory, the state accumulates the most deforested areas in the Amazon biome. The graphs below extracted from the PRODES system illustrate the accumulated deforestation between the years 2008 and 2022. The adhesion of new members must be submitted to the Federal Public Ministry of the state. The list below lists all private sector PVG signatories.

31

At left: Deforestation increases in the States; At right: Accumulated deforestation increments - Amazon – States

Source: PRODES

CORPORATE NAME AND NATIONAL REGISTER OF LEGAL ENTITIES OF THE ASSOCIATES

APR COMÉRCIO DE CEREAIS DE IMPORT E EXPORT EIRELI 37.082.932/0001-30

ABIOVE - BRAZILIAN ASSOCIATION OF VEGETABLE OIL INDUSTRIES 00.640.409/0001-72

ADM OF BRAZIL 02.003.402/0076-92

AGRA - ARMAZÉNS GERAIS LTDA 29.288.997/0001-09

AGRO AMAZÔNIA PRODUTOS AGROPECUÁRIOS SA 13.563.680/0025-70

AGRO KARAJÁ COMÉRCIO DE CEREAIS E EXPORTAÇÃO LTDA 30.182.564/0002-34

AGROMAIS COMÉRCIO DE GRÃOS LTDA 36.698.859/0001-63

AGRONORTE LOGÍSTICA E AGRONEGÓCIOS LTDA 00.293.663/0002-22

AMAGGI 77.294.254/0001-94

ANEC - NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF CEREAL EXPORTERS 60.853.306/0001-12

APAVI - PARAENSE POULTRY ASSOCIATION 05.387.709/0001-05

ARMAZENS GERAIS LTDA 24.854.352/0001-72

FJ AGROINDUSTRIAL LTDA 08.533.599/0010-21

FRONTEIRA CORRETORA DE GRÃOS LTDA ME 28.686.402/0001-00

GAVILON DO BRASIL COMERCIO DE PRODUTOS AGRICOLAS LTDA 04.485.210/0001-78.

MASTER GRAIN GROUP 14.119.613/0001-57

HERBINORTE AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS 10.348.159/0001-55

HP ARMAZÉNS GERAIS EIRELI 31.697.648/0001-92

HUMBERG AGRIBRASIL COMÉRCIO E EXPORTAÇÃO DE GRANES SA 18.483.666/0001-03

JAD COMÉRCIO DE CEREAIS DE IMPORT E EXPORT EIRELLI 27.737.510/0001-00

JUPARANÃ COMERCIAL AGRÍCOLA LTDA 02.219.378/0001-06

LAVROSOLO SOLUÇÕES AGRÍCOLAS LTDA 08.839.710/0001-11

LOUIS DREYFUS COMPANY BRASIL SA 47.067.525/0001-08

MASTER COMÉRCIO E EXPORTAÇÃO DE CEREAIS LTDA 14.119.613/0003-19

BELAGRO - G BELUSSO COMÉRCIO DE GRAIN 32.623.554/0001-31 MIL ARMAZÉNS GERAIS LTDA 24.854.352/0001-72

BERTUOL INDUSTRIA DE FERTILIZANTES LTDA 05.644.974/0006-36

BUNGE ALIMENTOS SA 84.046.101/0371-94

CARGILL AGRICOLA S A. 60.498.706/0001-57

CEREAIS GUARANI LTDA 16.782.818/0001-43

INDEPENDENT CEREALIST 05.275.206/0001-48

CEREALISTA VALE FÉRTIL LTDA 63.831.820/0001-45

CHS AGRONEGOCIO - INDUSTRIA E COMERCIO LTDA 05.492.968/0032-00

CJ INTERNATIONAL BRASIL COMERCIAL AGRICOLA LTDA. 21.294.708/0008-49

COADE - COOPERATIVA AGROINDUSTRIAL DE DOM ELISEU 15.918.791/0001-00

COFCO INTERNATIONAL BRASIL SA 06.315.338/0064-00

COMERCIAL AGRO FERNANDES EIRELI 43.285.172/0001-61

COMÉRCIO DE GRÃOS COLORADO LTDA 47.706.576/0001-32

COOPERNORTE - COOPERATIVA AGROINDUSTRIAL

PARAGOMINENSE 14.718.125/0001-66

DGA AGROPECUARIA EIRELI 39.382.305/0001-40

ENGELHART CTP (BRASIL) SA 14.796.754/0001-04

FERTITEX AGRO 74.649.138/0001-52

FERTITEX AGRO (SANTARÉM) 74.649.138/0011-24

MVM EMPREENDIMENTOS AGRÍCOLAS EIRELI EPP 20.781.341/0001-59

NATIVA AGRÍCOLA LTDA 07.634.396/0009-25

NEULS AGROINDÚSTRIA 08.836.065/0001-83

NOVAAGRI STORAGE AND DISPOSAL

INFRASTRUCTUREAGRICULTURALSA 9.077.252/0001-93

PORTAL AGRO COMÉRCIO E SERVIÇOS LTDA 10.197.621/0002-41

PREMA COMÉRCIO E EXPORTAÇÃO DE CEREAIS EIRELI 18.723.151/0004-86

RM AGRÍCOLA LTDA 18.426.776/0002-14

RURAL BRASIL SA 14.947.900/0025-22

SANTANA PRODUTOS AGROPECUÁRIOS LTDA 05.430.190/0001-09

SANTO ANTÔNIO DA BARRA LTDA ME 12.674.899/0001-07

SÃO PEDRO GRAIN COMMERCIALIZATION 26.796.361/0001-80

UNION OF RURAL PRODUCERS OF PARAGOMINAS 05.262.134/0001-02

SODRUGESTVO AGRONEGOCIOS SA 23.150.901/0008-31

VITERRA BRASIL S.A 32.441.636/0001-65

WK COMMODITIES E TRANSPORTES LTDA 40.120.385/0001-45

32

An important feature of PVG is that the Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries (ABIOVE) is at the forefront. The structure of the protocol is similar to the Soy Moratorium and the Monitoring of Soy in the Cerrado.

The standard establishes criteria for legal and environmental compliance, requiring verification of the registration and status of the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR). Subsequently, the productive capacity is evaluated according to the production area declared in the CAR, being the effective planting area. The declared produced volumes must be limited to the productive capacity of the farm, discouraging the acquisition of third parties or the expansion of the agricultural area through deforestation. The products covered by the PVG are rice, soybeans and maize. The average productivity for the 2020/2021 harvest should be respectively 60 bags/ha (3.6 t/ha) 70 bags/ha (4.2 t/ha) and 140 bags/ha (8.4 t/ha).

The rural properties of soy producers cannot be included in the list of embargoed areas issued by IBAMA, available for consultation at https://siscom.ibama.gov.br/geo_sicafi and on the List of Illegal Deforestation in the State of Pará through the link https://monitoramento.semas.pa.gov.br/ldi/. This criterion is essential for qualifying the supplier, assessing the existence of an environmental assessment, embargo for deforestation or for another reason. The verification is done both through the identification of owners and companies and through the geographic coordinates. The figure below illustrates the distribution of embargoed rural properties identified in the Pará List of Embargoed Properties (LDI).

Grain suppliers must also not be enrolled in the slavery-like work list issued through the Ministry of Economy available at https://www.gov.br/trabalho-e-previdencia/ptbr/composicao/orgaos-especificos/secretaria-de-trabalho/inspecao

33

Source: SEMAS PA

ABIOVE published a compliance level survey crossing the total soy production in the state reported by the National Supply Company (CONAB) in the amount of 3,568,200.00 tons for the 2020/2021 harvests against 3,209,066.53 tons of soy audited in the PVG. Therefore, approximately 10% of the volume produced was not submitted to a sustainability audit according to the protocol.

The chart below illustrates compliance with the four principles used in the benchmarking analysis among sustainability standards.

LEGAL COMPLIANCE

The Pará Green Grain Protocol requires legal compliance with environmental requirements regarding deforestation, in accordance with the forest code. It also verifies the supplier's and farm's registration on the list of work analogous to slavery.

MANAGEMENT OF SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS AT STAKEHOLDER LEVEL

The Green Protocol for Grains of Pará does not establish mechanisms for socioenvironmental management and relationship with stakeholders.

GOOD AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES

The Green Grain Protocol of Pará does not establish good agricultural practices.

DEFORESTATION CONTROL Compliance with national legislation (forest code)

PVG follows the main Brazilian legislation for the protection of forests, the forest code as a reference for compliance. The certification scope areas are analysed based on the cut-off date established in the legislation.

34

Compliance with EU RED II

PVG does not meet the EU RED II regulations.

Considerations regarding HCV

Areas of high conservation value (HCV) are territories covered by the forestry code. All territories defined by legislation are treated equally in terms of the need for protection and the prohibition of deforestation. Territories such as native forests or other biodiversity conservation areas can be encompassed through the National System of Nature Conservation Units, the SNUC.

Definition of deforestation in the standard

The PVG does not clearly define deforestation, however, it follows the definition of current local legislation, in particular the Forest Code. As it is an automated detection system, it recognizes deforested areas

Transparency Mechanism

The PVG has a website for publishing news and results. During the first two months of 2023, no disclosures or information or news were found regarding the execution of the protocol during the 2020/2021 harvest.

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

The PVG is a public and private initiative program, acting in mutual interest to reduce the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest. Its performance contributes to the reduction of the deforested area through the commercial restrictions imposed on the signatories of the protocol. Traders' suppliers must comply with the protocol to maintain active business through commercial intermediation with traders and consequent production flow.

The molds for verifying conformity and performance are similar to the Soy Moratorium program, with the participation of ABIOVE, ANEC and Unigrãos, a grain trading company from Goiás.

Although it has an expressive participation, deforestation in general is not discouraged in the region. The cause may be related to other exploratory activities in

35

the region, which are not directly related to soy, or only to soyin the state, and there should be a study covering this topic.

The Green Protocol acts directly with the Public Prosecutor's Office, monitoring is related to legal requirements, and is not a voluntary third-party audit system.

SOURCES FOR CONSULTATION

PVG -https://protocolodegraos.com.br/ LDI -https://monitoramento.semas.pa.gov.br/ldi/ Terra Brasilis -http://terrabrasilis.dpi.inpe.br/

36

INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION PERFORMANCE STANDARD

BASE DOCUMENT

Performance Standards on Social and Environmental Sustainability - 2012

CONTEXTUALIZATION

The Intenational Finance Corporation - IFC is a member organization of the World Bank. Its objective is to promote economic development by financing private sector businesses in developing countries. IFC was founded in 1956, is present in 184 countries, and operates in more than 100 countries. In the year 2022, it executed the amount of US$ 32.8 billion in investments. Of this amount, in Brazil in 2022, US$ 4.22 billion were invested in various segments.

IFC raises credit by issuing bonds in the international capital markets to finance projects. The credit reverted to low-cost financing. Its main activity is in socially responsible investment through roles linked to sustainable indicators. Specifically in the area of sustainability, it is present through programs for the issuance of Green Bonds for projects related to Climate Change, and Social Bonds for projects that address social issues. Both programs are aligned with the IFC's Green Bond Principles and Social Bond Principles. At the same time, there are other forms of financing, but all must comply with certain standards developed by the IFC.

IFC-funded projects must comply with the organization's Performance Standards (PS). These PS consist of documents with criteria of:

● Assessment and Management of Social and Environmental Risks and Impacts

● Conditions of Employment and Work

● Resource Efficiency and Pollution Prevention

● Community Health and Safety

● Land Acquisition and Involuntary Resettlement

● Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Management of Living Natural Resources

● Indian people

● Cultural heritage

37

Source: IFC

The IFC does not have a specific activity for the soy agribusiness. The most important aspect in relation to PS is its reference for socio-environmental risk assessment at shareholder level. Banks, other investment institutions and financial organizations use the Equator Principles, which are a set of socio-environmental criteria that help financial organizations to ensure that they finance responsible projects in the social and environmental sphere. These principles underlie the IFC PS. There is a categorization of the risk level of projects that are A (high risk), B (medium risk) and C (low risk), as detailed below.

Category A: consists of projects with risk of irreversible environmental impact, therefore, sensitive, different or unprecedented.

Category B: are projects with an environmental impact on human populations or in environmentally relevant areas, but with the possibility of reversing damage.

Category C: are the other projects that have little or no adverse environmental impact.

FI category: are the commercial activities that involve investments in Financial Institutions (FI) or through delivery mechanisms involving financial intermediation. This category is divided into:

FI-1:financial exposure through FI classified as category A.

FI-2:financial exposure through FI classified as category B or with a very limited number and categorized as A.

FI-3:financial exposure through FI classified as category A.

38

Agricultural-related projects that comply with the Equator Principles use the IFC standard to conduct due diligence on clients of all levels and types of organization. Especially for agricultural enterprises, several financial organizations use PS as a reference for assessing socio-environmental compliance.

The socio-environmental analysis assesses whether the client identifies and manages socio-environmental risks, considering the relationship with stakeholders, traditional populations and indigenous peoples. Effectively on aspects of deforestation, issues of biodiversity protection, flora monitoring, and the promotion of sustainable management of living natural resources are evaluated

The standard does not give legal compliance parameters, although it does require compliance with local laws. In the absence of specific laws, internationally recognized parameters are used. The IFC also does not certify clients, as this is not a quality or sustainability certification. This is a set of voluntary adoption performance standards, which may be required by financial institutions to assess the risk of socioenvironmental impact on their investments. The purpose is to guide conduct in accordance with international conventions and treaties on socio-environmental risk management.

The chart below illustrates compliance with the four principles used in the benchmarking analysis among sustainability standards.

LEGAL COMPLIANCE

IFC requires legal compliance in social, human rights and labor relations criteria.

MANAGEMENT OF SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS AT STAKEHOLDER LEVEL

The IFC PS require mechanisms for assessing and managing socio-environmental risk, neighbouring communities, indigenous peoples and stakeholders.

39

GOOD AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES

PS IFC define criteria for the efficient use of pesticides and chemicals. They require legal compliance and compliance with international conventions and treaties for agricultural management, in addition to the application of good practices in the use of natural resources.

DEFORESTATION CONTROL

Compliance with national legislation (forest code)

The IFC PS do not have criteria aligned with national legislation. Establishes the need for environmental preservation and conservation of areas of High Conservation Value (HCV) and requires compliance with international conventions or local legislation. In its Performance Standard 6 - Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Management of Living Natural Resources, it defines that in cases where a proposed project is located in a legally protected area or in an internationally recognized area, legal permission for the development of activities must be demonstrated.

Compliance with EU RED II

The IFC PS do not make direct reference to the European Union's biofuels policy.

Considerations regarding HCV

Performance Standard 6 - Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Management of Living Natural Resources defines through the requirements of protection and conservation of biodiversity the need to identify areas containing natural habitats or modifications, as well as habitats of high critical value. Intervention in these areas must be legally permitted and still comply with SP requirements. However, intervention in these areas is allowed when:

● Inexistence of viable alternatives within the region for the development of the project in modified or natural habitats that are not critical;

● The project does not have measurable adverse impacts on the biodiversity values for which the critical habitat is designated, nor on the ecological processes that support those biodiversity values;

● The project does notentailsthe net reduction in the global and/or national/regional population of any speciesgravely threatenedor Threatened for a reasonable period (determined by expert).

40

Transparency Mechanism

IFC does not publish the results of its due diligence on clients, or clients of Financial Institutions. The respective clients are not exempt from publishing the results of the diligences, but must establish communication mechanisms with interested parties.

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

The IFC PS are the main reference for financial institutions to assess the socioenvironmental risk of their direct project clients, or through Financial Institutions. However, other institutions not linked to the IFC also employ its principles for projects with potential risk of social and/or environmental impact.

Category B developments are the most common among project clients, especially for investment projects in agribusiness.

The standard is not a certification, but a system of performance standards that investment clients must comply with. It focuses on socio-environmental aspects, but it is multisectoral and very comprehensive, being the main market reference.

Financing projects commonly have linked deforestation and monitoring indicators, with recovery or conservation goals.

SOURCES FOR CONSULTATION

IFC Performance Standards:www.ifc.org

IFC Fiscal Year:www.ifc.org

41

PRODES SYSTEM - DEFORESTATION MONITORING

PRODES (Program for the Calculation of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon) is a project to monitor deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. It is run by the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and provides annual estimates of the rate of deforestation in the region. The project uses satellite imagery to map and measure forest loss, and has been widely used as an important tool for the management and conservation of the Amazon rainforest. Annual rates are estimated from the deforestation increments identified in each LANDSAT class satellite image (20 to 30 meters of spatial resolution and 16-day revisit rate) in a combination that seeks to minimize the problem of cloud cover and ensure a full coverage of the Legal Amazon.

It has been considered one of the most accurate and reliable deforestation monitoring systems available, and its estimates are widely used by international organizations, governments, environmental groups, and others interested in conserving the Amazon rainforest. Since satellite images are used to map and measure forest loss, this allows for an accurate estimate of the rate of deforestation in the region. Recent results, based on analyses carried out with independent specialists, indicate a precision level close to 95%.

In addition to providing deforestation estimates, the project also provides important information on the main causes of deforestation, such as agriculture, mining, livestock, urban expansion and road construction. This information is important to help authorities and other stakeholders guide policies and actions to conserve the forest and prevent further loss of natural habitats and species.

According to PRODES estimates, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon reached a deforestation peak in 1995 with a rate greater than 29,000 km², later this value fell until 2001, to then return to a level close to the peak between the years of 2003 and 2004. Faced with this challenge, the Presidential Decree of July 3, 2003 was signed, which established a Permanent Interministerial Working Group with the purpose of proposing measures and coordinating actions aimed at reducing deforestation rates in the Legal Amazon. A careful assessment of the causes of the problem was then carried out, as a basis for planning a set of integrated actions by the government to be implemented with the active participation of Brazilian society. Thus arose

In the first and second phases, the measures to combat deforestation had the following guidelines: 1) valuing the forest for the purposes of conservation and sustainable use;

2) recovery of degraded areas as a way to increase productivity and reduce pressure on the remaining forests;

3) land and territorial ordering, prioritizing the fight against public land grabbing, the creation of conservation units and the homologation of indigenous lands;

4) improvement of instruments for monitoring, licensing and inspection of deforestation;

5) promotion of activities for the sustainable use of forest resources and/or intensive use of agricultural areas; 6) decentralized

42

and shared management of public policies between the Union, states and municipalities;

In the first and second phases of the PPCDAm (from 2004 to 2011), the actions with the greatest impact on the drop in deforestation stemmed from the monitoring, control and inspection axis. While the third phase proposed to strengthen and promote the viability of the productive chains that constitute alternatives to deforestation.