P

Pasos

Design

Interventions

for Gendered Agency in Latin Partner Dance

Design

for Gendered Agency in Latin Partner Dance

Design Intervetions for Gendered Agency in Latin Partner Dance

MONICA ALBORNOZ

MFA Products of Design

School of Visual Arts

Pasos: Design Interventions for Gendered Agency in Latin Partner Dance.

1st Edition © 2023 Monica Albornoz

Written, gathered and designed by Monica Albornoz.

Created as part of the author’s master’s thesis in Products of Design at the School of Visual Arts in New York City.

This work is licensed under the creative commons attribution, noncommercial, no derivatives, 3.0 unported license.

Attribution — You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Noncommerical — You may not us this work for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

“If

it’s true that we’re made for community, then leadership is everyone’s vocation.”Adrian Piper, American conceptual artist and philosopher. Notes on Funk

To Ben, who encouraged me to pursue the dream of design in the first place.

For your super-human listening ear and tireless support, for your many homecooked meals and little favors. For giving me perspective when I needed it most and for holding me up when I thought I could give no more. But most of all, for nurturing my wish to lead in dance, for asking me to lead you, and for pushing me to snap out of the fear and dare to lead.

To the dancers, teachers, and organizers I spoke with for this thesis.

For your precious time. For your openness in discussing the confusing paradoxes of the partner dance experience. For inviting me to your events and classes, and for giving me a privileged look at your methodologies, strategies, and business structures. For confiding in me your dance dreams and your personal stories, for pouring out your anger and frustrations, and for reminding me— through your passion—that dance is life, and that’s why we need to do better.

Isummoned all my courage and came over to Juan. “Do you want to come to dance lessons at my house?” I asked, trying to sound chill. “Lala and Cami are coming tomorrow. It’s fifty thousand pesos for an hour-long class.” Juan muttered some version of “...Maybe next week.” He had soccer practice.

Enrique, the dance teacher my mom had found for me, had encouraged me—now for multiple weeks in a row—to ask my male friends to come over for our afterschool dance lessons on Tuesday afternoons. My friend Simon had joined once or twice, but we needed more boys. We needed more boys because Gabriela, Camila, and Laura would often join me for class, and this meant that, as Enrique danced with one of us, the other

three held invisible partners in the air while doing the basic step.

I remember the quiet frustration and anticipation of waiting for my turn to dance with Enrique. When I danced with him, it was impossible not to smile. I could feel his charisma, his sazón (read: Spanish for “characterful flavor”), the music made physical through the moves he guided me on. I loved the heightened sense of attention that dancing asked of me and the endorphins I felt when moving rhythmically to my favorite music alongside someone else. Dancing was pure, freeing pleasure. But it was a pity: Having my girlfriends over came at the cost of partner dancing with Enrique, and the quinceañera parties for which I was learning to partner dance in the

the boys don’t like to dance

first place severely lacked boys who knew or wanted to partner dance at all.

I remember eagerly arriving at my first quinceañera party clad in heels and a short dress, eager to put my dance moves to use, maybe turn some heads, hopefully get a date. To my dismay, whenever the DJ played salsa and merengue seemed to be the de facto sit-down break time for the boys. All that fist-pumping to EDM hits of the early 2010s was exhausting, after all.

I used to label it as unfortunate that I didn’t have many male friends to invite to dance lessons as a 14-year-old. Thirteen years later, I know better. What is unfortunate is

the pervasiveness of a culture that teaches men to lead and women to follow. How much are girls and women missing out on as they sit on the sidelines waiting for men to enable them to do what they love?

Not once during that year of learning partner dance with Enrique did it occur to me to turn around, grab a fellow girlfriend and lead. Nor did it occur to them. How could that be?

Seventeen years later, it’s hard to express how much I wish that Enrique had taught me to lead partner dance. As you read through this thesis, I hope you will understand why.

Everything I knew about partner dance began to change in January of 2017 when a friend took me to a “Latin night” at the Soda Club, a four-story dance club in Berlin’s popular Prenzlauer Berg neighborhood. I was expecting a full-on dance club, loud and dim, where we’d dance a bit, but mostly drink, chat, and be flirted with. What I found was not quite that. In Colombia, drinking and dancing were inseparable. At the Soda Club in Berlin, I never found myself dancing with a drunken partner. In Colombia, a successful dance was one that encouraged your partner to stay with you for songs on end. In Berlin, the sign of a good dance was that the men would let you go after a song or two, but ask you to dance a second time

later that night or the following week. In Colombia, you’d never go dancing on your own. In Berlin, people arrived on their own all the time. All in all, in Colombia, partner dance was an excuse or means for something else, social, or romantic, or sexual. At the Soda Club in Berlin, partner dance was an end in itself.

This world that I discovered in Berlin, so different from dancing in Colombia, is what I’m calling the international amateur partner dance space.

I wish I could say that those first six months of dancing in Berlin were everything that my teenage school dances failed to be. After all, at Soda, the boys did like to dance, and they danced pretty well. But I still saw my place in the

world, and my place in the world of dance specifically, through the eyes of my 14-year-old self. I sat around waiting to be asked for a dance. I felt sad when the better dancers made eye contact with me but did not extend an invitation. I felt deeply confused and pained when I danced with men who’d swirl me around, much like a toy, but did not make eye contact or smile a single time during the whole song.

After the good dances, I’d feel like I was on a high, endorphins racing and no alcohol needed. But there were one too many times when I felt down, stuck waiting, or wishing that things or people were different.

I shared my pains with my friend Candace, the one responsible for bringing me to Soda in the first place. She was blunt and forward. She said, “You look for the people you want to dance with, and when a new song is about to start, you come over and ask them.” I had no idea that I could ask for a dance until that moment.

As my following skills improved, I got asked to dance more now, and faces and names around the club became familiar. But while some pains went away, new ones came. As a follower, I depended on a great leader to have a great dance. And sometimes, my favorite dancers weren’t around. There’d be nights when I’d feel a huge chasm between the dance experience I desired and the one I was having. Even though I had learned that I could ask for a dance and pursue the experienced

leaders, I was still a follower, and following always came after leading.

*

As the teacher yelled, “Change!” to signal the time to switch partners and practice the choreography with someone else, instead of a man, a woman approached me. It was the first time I’d ever danced with a woman. Flat-out surprised, I asked her, “Oh wow, you lead?”

What I felt in the early seconds of dancing with that woman was unforgettable. It’s unforgettable because, five years later, I see those feelings in my followers’ expressions when I approach them after the call to “Change!” in class.

*

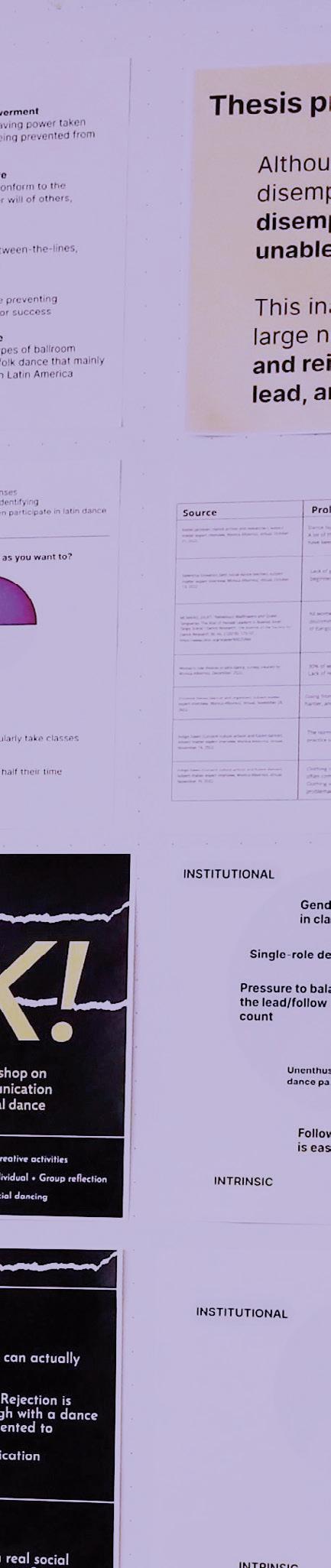

I chose to explore gender and leadership in amateur partner dance as my thesis topic because from the moment I danced with that woman in Berlin, my journey into the leader’s role has been harder than I expected it to be. I wanted to understand—why?

What is getting in the way? Am I alone in this experience? And most importantly, what can design do to help?

This book is a documentation of my master’s thesis process, conducted from September of 2022 to May of 2023.

This thesis is not a traditional academic thesis. In this work, I use contemporary design methodologies to explore the topic of partner dance and offer solutions and provocations to the problems identified.

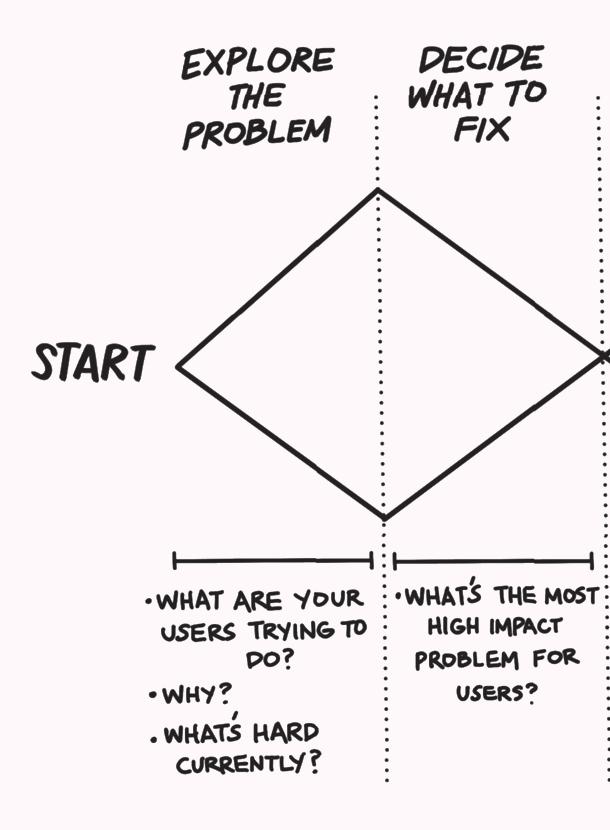

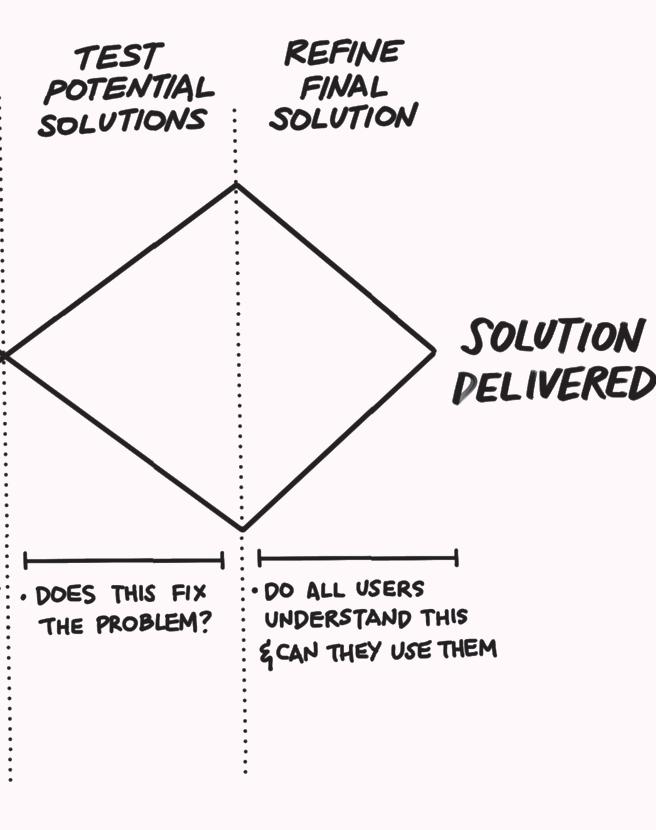

The overarching methodology of this thesis is the double-diamond model of design (see page 24). This model describes design as a process that starts broadly in problem discovery, then narrows down into a specific problem definition. This specific problem then inspires a range of product or solution explorations, which—through testing—re-define the problem and the requirements for more specific,

successful solutions.

Alongside the doublediamond, this thesis used rapidprototyping and user-centered design methodologies* to quickly test ideas, engage dancers and stakeholders in the design process, and create safer, more effective, and more ethical solutions. The final outcome of this thesis is not a set of finished objects ready to be launched to market, but a suite of products of design in the form of business models, digital products, services, speculative propositions, experiential engagements, and wearables.

The double-diamond model was officially invented by the British Design Council in 2005.

The double-diamond model was officially invented by the British Design Council in 2005.

Social dance

A category of dance form where sociability is the primary focus. Examples of social dances include partner dances, line dances, group dances, and even solo club dancing.

Partner dance

A kind of social dance whose basic choreography involves coordinated dancing generally between two partners. Examples include ballroom dance, Lindy hop, tango, salsa, and many others.

Latin dance

Types of ballroom and folk dance that primarily originated in Latin America or which were created by Latin American communities.

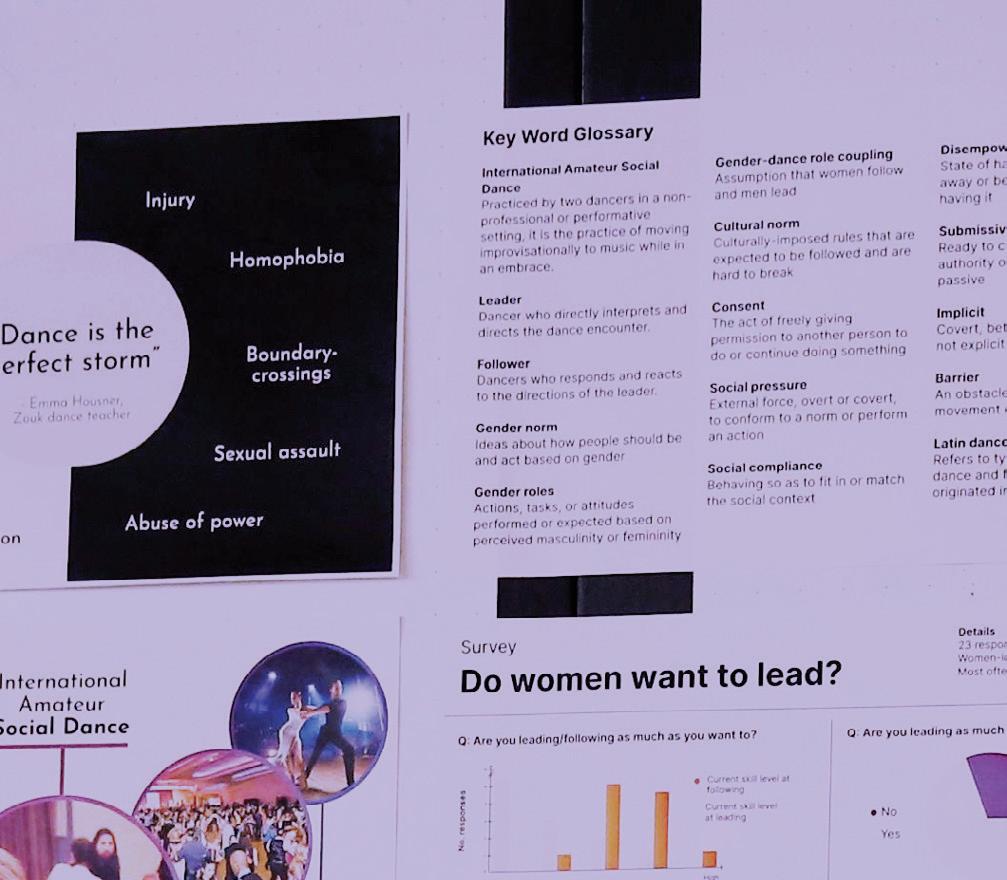

Cultural norm

Culturally imposed rules that are expected to be followed and are hard to break.

Gender norm

Ideas about how people should be and act based on gender.

Gender roles

Actions, tasks, or attitudes performed or expected based on perceived masculinity or femininity.

Social pressure

External force, overt or covert, to conform to a norm or perform an action.

Social compliance

Behaving so as to fit in or match the social context.

Mostly found in large cosmopolitan cities, it refers to the spaces, culture, and people that participate and run partner dancing classes and events attended by hobbyist dancers.

The “class”

The partner dance class that often precedes the “social,” or party, in the amateur partner dance scene.

The “social”

A term used in the partner dance scene to reference an organized event or meet-up, usually accessed at a cost, where partner dancers gather to dance with each other.

Dance encounter

A dance between two people, usually lasting for at least an entire song.

The role of a dancer in a dance encounter, generally either that of leader or follower.

Leader

The dancer in the dance encounter who directly interprets the music and directs their partner—the follower—through a sequence of improvised movements.

Follower

The dancer in the dance encounter who responds and reacts to the directions of the leader.

Switching

The act of organically changing roles within a dance encounter, such as that the person who started leading then follows, and vice-versa.

The custom and culture in amateur partner dance that dancers stick to a single dance role, either leading or following, whether in class, during a dance encounter, or until they have achieved mastery of that role.

Single-role mechanics

The practice in partner dance classes of asking students to pick either the leader OR follower role during the class.

Switch-role mechanics

The less common practice of teaching class attendees both leading and following. This practice is not common in Latin dance classes.

Gender-role coupling

The assumption that women follow and men lead.

Implicit

Covert, between-the-lines, not explicit.

Consent

The act of freely giving permission to another person to do or continue doing something.

Disempowerment

State of having power taken away or being prevented from having it.

Submissive

Ready to conform to the authority or will of others, passive.

Femininity

The qualities or attributes regarded as characteristic of women or girls.

Sex-positive

A movement that seeks to change cultural attitudes and norms around sexuality, promoting the recognition of sexuality as a

natural and healthy part of the human experience. It emphasizes the importance of personal sovereignty, safer sex practices, and consent, and covers many aspects of sexual identity, including gender expression.

Barrier

An obstacle preventing movement or success.

Enforcement

The act of compelling observance of or compliance with a law, rule, or obligation.

Power

The ability to influence or outright control others’ behavior.

Agency

The feeling of control over actions and their consequences.

(he/him), Latin partner dancer, co-creation workshop participant

“The energy you get in partner dance is something you can’t get anywhere else.”

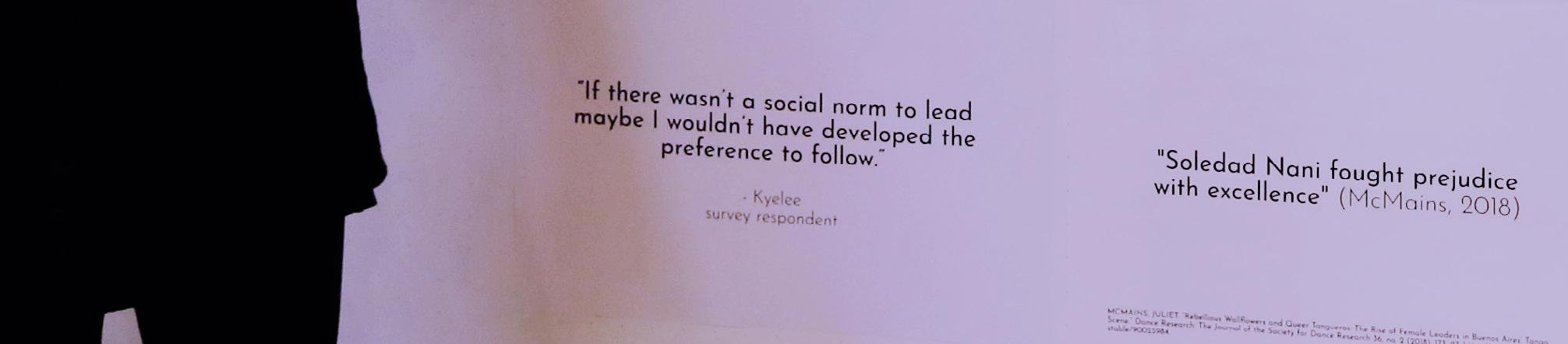

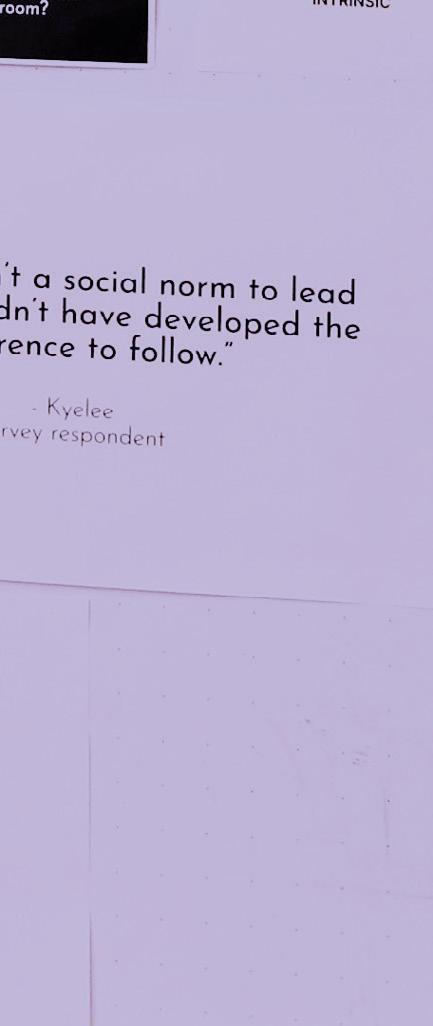

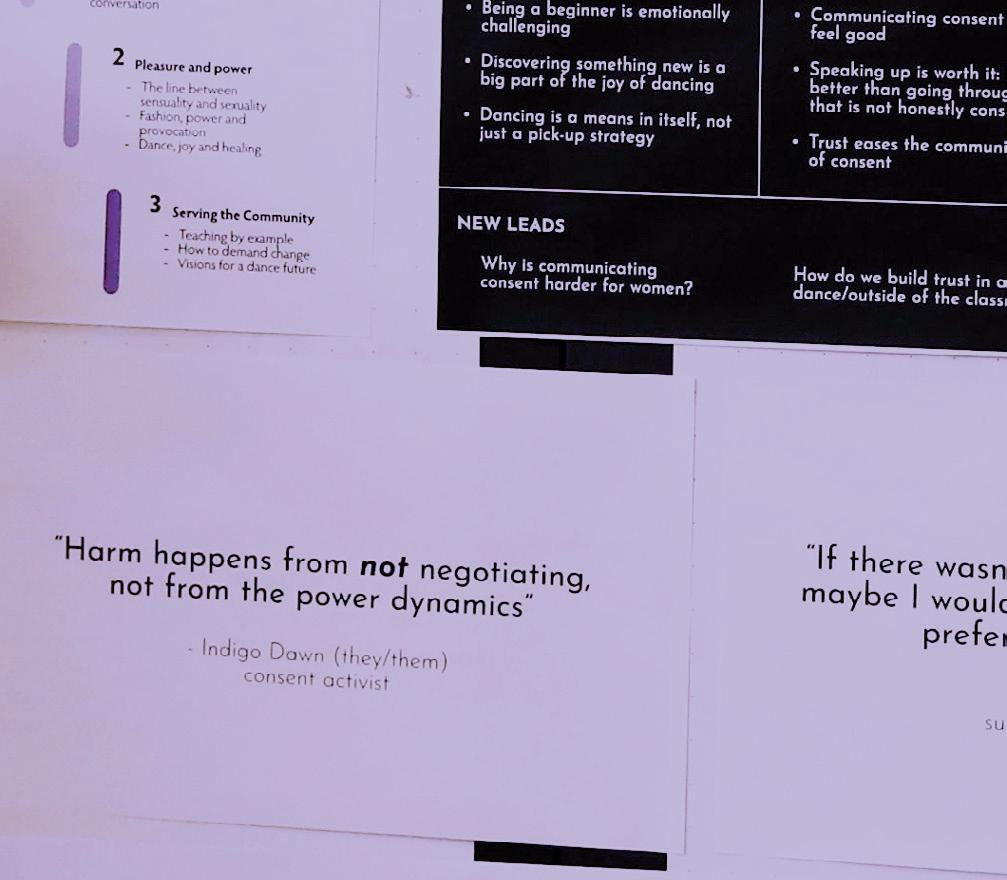

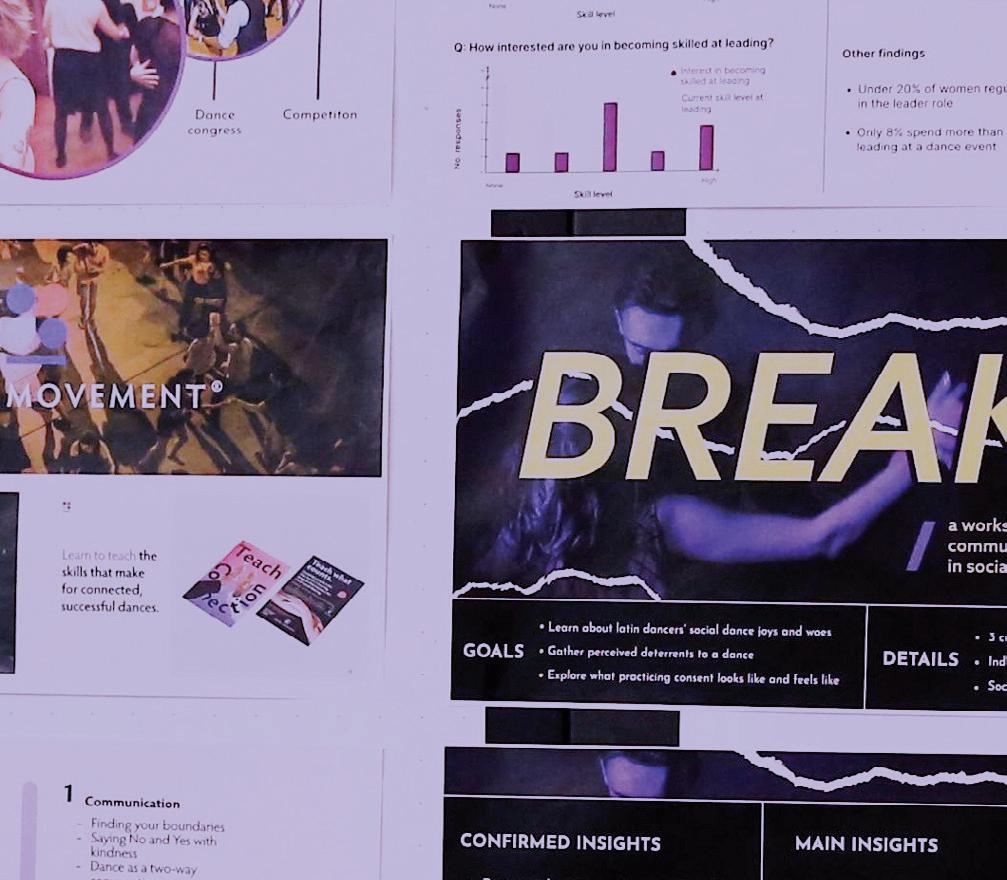

For this thesis, many kinds of research. This included desk research, field research, expert interviews, user inteviews, surveys, a co-creation workshop and concept and user testing

I read academic and magazine articles, books, and blogs, and listened to podcasts regarding partner dance, gender, leadership, and pleasure.

I attended many dance events and classes across Latin and other styles of partner dance, primarily in NYC. Events I attended ranged

in scale, from a 5-day Bachata congress with thousands of attendees to a Kizomba event lasting a few hours with less than 50 attendees. Event locations included dance studios, bars, restaurants, and a hotel conference room.” Event target audiences tended to be the same; while some were much more explicitly queer-friendly than others, none were queer-exclusionary. In classes, I participated as a leader the majority of the time and as a follower on a few occasions.

I also observed classes from the sidelines, overtly and covertly. I assisted a woman leader teaching a Latin dance class, as her follower.

I had formal and informal conversations with stakeholders at the center of partner dance experiences, including event organizers, instructors, event photographers, and dancers, as well as formal conversations with experts who could provide an academic and sociological perspective on the experience of partner dance, like researchers, activists, consent experts, and dance movement therapists, among others.*

I spoke with dancers of different genders, races, sexual orientations, dance-role choices, and dance-role levels of expertise.**

I facilitated a co-creation session with four practitioners of Latin partner dance that explored dancers’ attitudes towards dance and challenges I had identified during my early desk and field research.

I conducted a survey about women’s role choices in Latin partner dance, which was distributed in Latin partner dance groups in NYC, and which was completed by 25 women-identifying respondents.

I gathered feedback on my four design interventions through concept and user testing of different kinds. These included running ideas

with subject matter experts (SMEs) and users during phone interviews, presenting low-fidelity prototypes to users over video calls, sending links to prototype testing surveys to users and SMEs, and piloting prototypes at real events making sure to gather feedback from event attendees.

* Note: the development of social dance as an elitist phenomenon was not unique to Europe. Some African and Native American cultures reserved dance for members of certain status or success, who had to undergo specific rituals or ceremonies to be allowed to perform the dance.

** The vast majority of the experts I spoke with above also had extensive personal experience practicing in cosmopolitan partner dance, so learnings from those conversations can qualify as user research as well.

“My first fake ID was not even for alcohol. It was to get into dance clubs.”

Emma Housner (she/her) Latin partner dance instructor

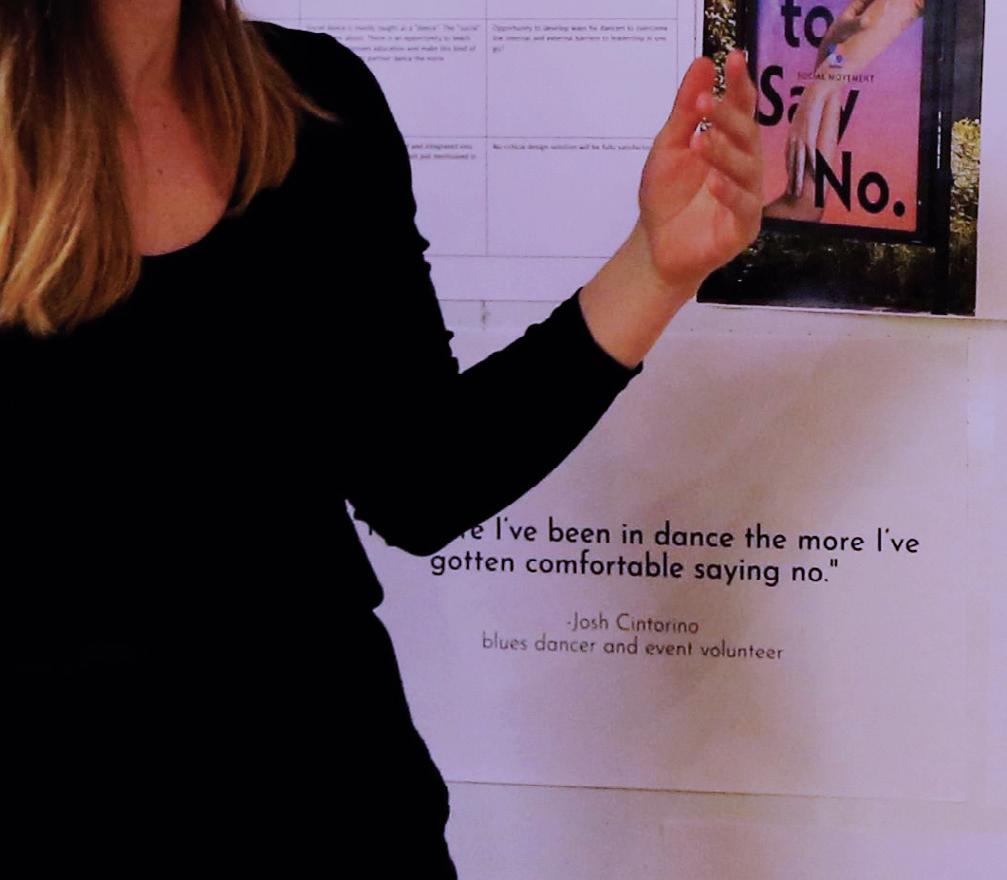

“If I’m gonna follow, that’s a song I’m not leading.”

“Dance is one of the spaces in my life where it feels safest to be authentic.”

Josh Cintorino Blues and fusion dancer

“I can’t lead for my life.”

“I wish I could lead.”

Several women Latin partner dancers, Classes and events in NYC

“I love leading so so so so much.”

Christine Nieves (she/her) Event runner, Bailamos Juntos Social

“You don’t have to be queer to want to lead.”

Sabrih Joy Short (she/her) Event runner, The Fusion Experience Social

“You come for the girls, you come back for the dancing.”

Jackson Lee (he/him) Latin partner dancer

Leandro Gil (he/him) Latin partner dancer

“Following is a submissive role in general.”

Indigo Dawn (they/them) Consent activist and educator

“When you dance, it’s like a mini-relationship, whatever the amount of time.”

Inessa Chernomaz (she/her) Operational manager, Sensual Movement

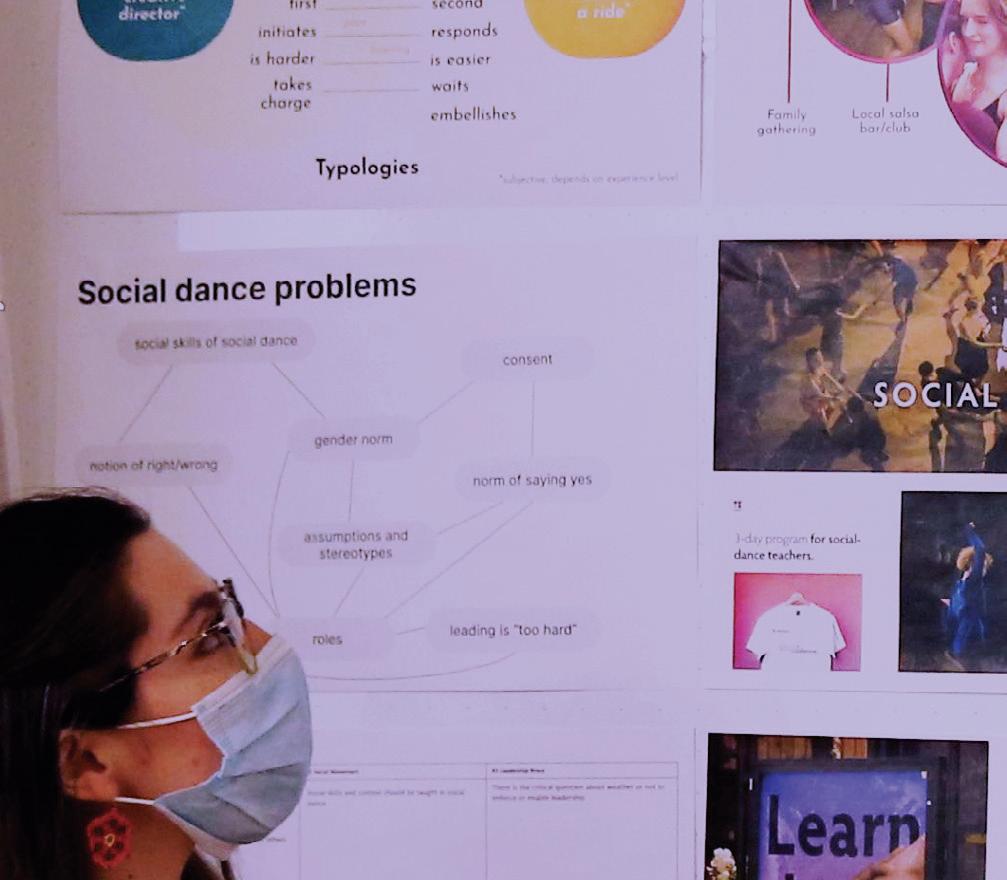

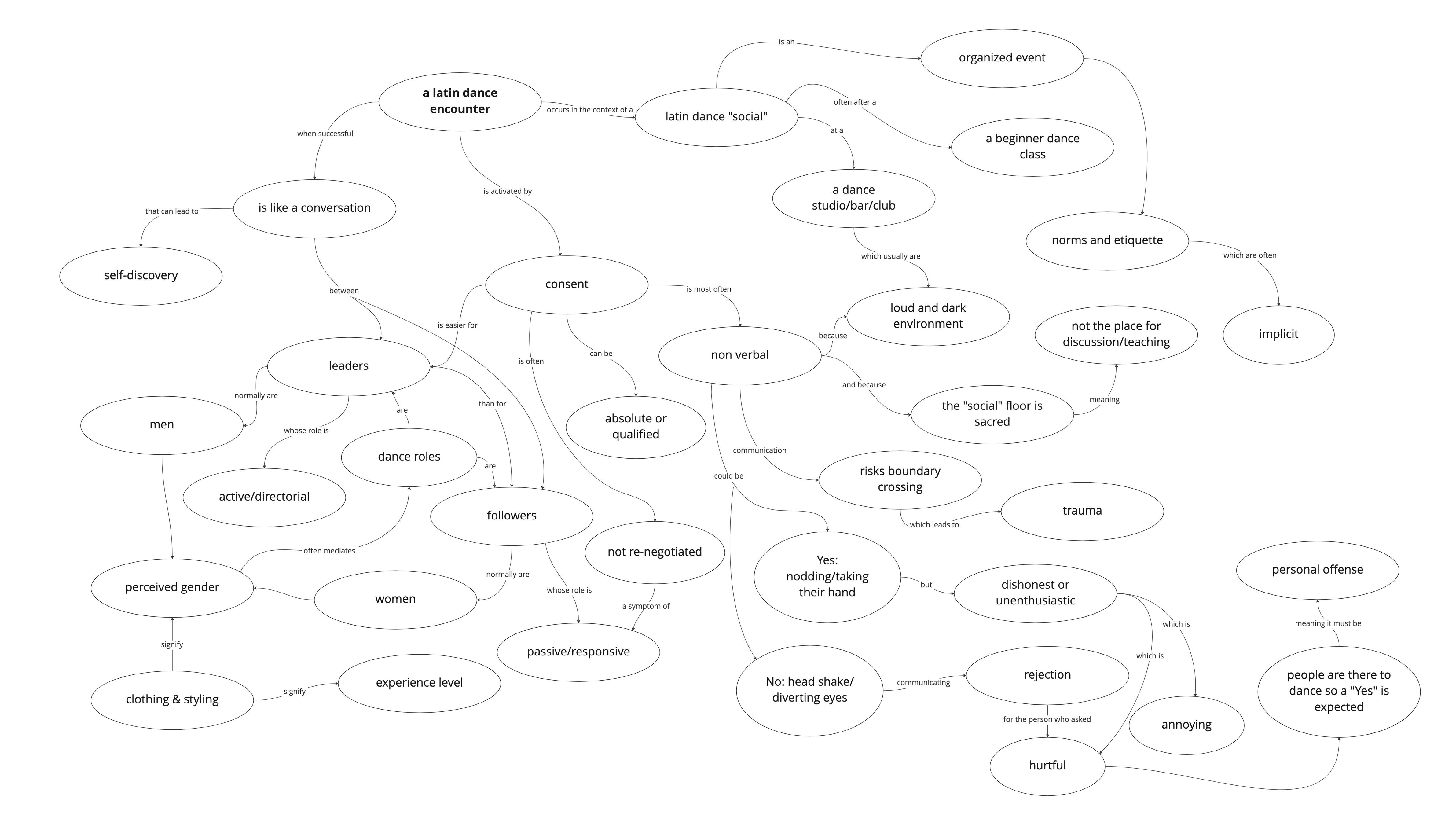

• Gender is coupled with dance role accross virtually all partner dance styles.

• Separating dance roles from gender stands to benefit all dancers, since learning one role helps improve at the other.

POWER

• Power dynamics are inherent to partner dance, with following being the more submissive role.

• Power, both having it and giving it up, is part of what makes dance exciting and pleasurable.

COMMUNICATION

• The physical enviornment of partner dance makes verbal and visual communication difficult.

• Poor communication creates risk of injury and boundary tresspassing for dancers, primarily followers.

JOY

• fun and pleasure are why partner dancers keep coming back.

• partner dance affords self-discovery and authentic expression.

• dancers find practicing the non-traditional role for their gender deeply empowering.

WOMEN

• Women are disempowered by dance’s gender roles.

• Women are more interested in learning to lead than men are interested in learning to follow.

• The gender norm gets in the way of women leading.

• partner dance simultaneously creates and reflects culture

• dancers draw parallels between behaviors in partner dance and the world outside dance

“You first come for the girls, you come back for the dancing .”

Jackson Lee (he/him), Latin partner dancer, co-creation participant

Cosmopolitan partner dance is the name I am giving to the partner dance contexts that exhibit values from both the “local” and the “European professional” ends of the social dance tradition. These include the communal, expressive, life-affirming values of street dances rooted in African culture and music, and the artistic, performative, goaloriented, correctness-driven values of European ballroom dances. Cosmopolitan partner dance is not unique to a single style of partner dance. In my years of dancing I have engaged in this kind of partner dance in styles like blues, fusion, and Latin dance.

The main characteristics of the space are the audience’s focus on personal enjoyment and pleasure through artistry, the prevalence of dance educational offerings alongside non-moderated parties, and dance’s reduced role as a tool for finding romantic or sexual partners.

Below are some characteristics:

METROPOLITAN + INTERNATIONAL Exists in large international cities like New York, Toronto, and Los Angeles, where populations are diverse and constantly changing.

PARTNER DANCING ONLY

Specifically engaged in partner dancing, not other instances of social dance, like group or line dances.

AFFORDABLE + ACCESSIBLE

Commonly marketed for $10 - $20 (in New York City) with the pre-social class often being complimentary. In New York City, some of the main locations of classes and events are around Penn Station and Times Square.

CONSIDERED LOCATIONS

Practiced in considered spaces that facilitate dancing, such as dance studios with boarded floors, and spacious bars and restaurants cleared of tables.

EDUCATION-ADJACENT

A connected culture of dancing and training, whether that is in classes before the “social” or in the promotion and showcase of amateur performance troupes.

SPECIFIC DANCE STYLE

Events, classes, and even rooms are specific to one or two kinds of music, so the audiences they attract are niche.

PART OF AN INDUSTRY

Comprised of an international community of freelancing instructors and DJs, clothing brands, partner dance celebrities, and brand-name international dance festivals.

I identified the following stakeholders in the cosmopolitan partner dance space:

• Event organizers

• Managers on duty

• Promoters

• Front desk clerks/cashiers

• Instructors

• Community leaders

• Dancers

• Advanced

• Intermediate

• Beginner

• Observers

Depending on the event, one individual might engage in multiple stakeholder roles in a single night.

Ifocused my work in cosmopolitan

Latin partner dance in New York City for several reasons:

THE LAGGARD

Of the cosmopolitan dance communities in NYC, Latin dance lags the furthest behind. Experts I spoke with agreed. Compared to blues, fusion, and swing dance, Latin dance is the most homogeneous, traditionally gendered, and has more prevalent machismo.

Latin dance is the largest of the partner dance scenes in NYC. This is unsurprising given the large

Latino population. I estimated 50 events (including classes) of Latin partner dance per week alone.*

CULTURAL LEGACY

NYC has a long connection to music and dance innovation, often from the Black and Latino communities.** Also, as a global hub, NYC exports and influences culture outside of its borders.

I already had some experience and connections in the scene.

For the above reasons, I thought I could have the most impact designing in this specific space.

* Based on conversations with partner dance instructors in New York, and by looking event listings online.

**Jazz music and lindy hop, hip-hop and salsa dance were all born in New York City.

Cosmopolitan Latin partner dance is not exclusively a space of or for Latinos. Of course, many New Yorkers of Latino heritage might default to or prefer Latin partner dance over other styles. But many of the stakeholders in cosmopolitan Latin partner dance in New York City are not Latino or Hispanic, and nobody thinks twice if they see an instructor, dancer, manager, etc., who is Eastern European, Asian, African American or of any non-Latino-appearing race or ethnicity.

While individual members of the Latin partner dance community mirror NYC’s cultural, racial, and ethnic diversity, I also believe that

cosmopolitan partner dance carries values and behaviours of its own, which dancers—whether Latino or not—adapt to or adopt. Here are some of the cosmpolitan partner dancer’s characteristics:

DANCE FOR DANCE’S SAKE

Dancers are primarily there to dance, not to date, not to have long conversations, not to drink.*

ARTISTIC

Dancers are interested and find pleasure in developing their dance skills from a technical perspective.

AMATEUR

Dancers are not there to make money. In fact, those who get bitten by the partner dance bug will often spend not insignificant amounts of money and time developing their skills. This might mean going to classes or events two or more nights a week, auditioning and paying joining fees for amateur performance teams, traveling to other cities or countries to attend large-scale multi-day events and purchasing clothing designed for dance such dance shoes.

While some arrive with friends, the context and structure of a dance class or dance event is not great for building friendships or going on a date. For this reason, many dancers arrive and leave alone.

NORMATIVE

In Latin partner dance, most dancers align with normative chatacteristics such as: being heterosexual, cis-gendered, traditionally feminine or masculine in appearance, and monogamous.

Everything from brand new to partner dance, to advanced professional.

Dancers can include men, women and gender nonbinary people.

All partner dances, as social and cultural practices, exhibit norms. Given the roots of partner dance in heterosexual courting, it makes sense that gender norms and gender roles are a large part of the social norms of partner dance. But in cosmopolitan partner dance, in our current day and age, gender roles and norms don’t make a lot of sense and do more harm than good. Gender norms limit men’s and women’s access to a truly agency-driven and transformative dance experience. They also discourage nonbinary dancers from participating.

Here are the distinctive norms in cosmopolitan partner dance:

• Women take the role of the follower and men the role of the leader.

• Women are approached and asked to dance by men.

• It is rude to deny a dance encounter.

• It is even more rude to stop a dance mid-way.

• It’s inappropriate to chat during a dance encounter. Chatting should be done while on the sidelines.

If you ask a partner dancer about partner dancing, chances are they will tell you that it changed their lives. Partner dance is powerful and unique. As Jackson put it “the energy you get in partner dance is something you can’t get anywhere else.” The magic of the dance hooks dancers, who shamelessly go the extra mile for it. Josh moved cities because of dance. Emma’s “first fake ID was not even for alcohol. It was to get into dance clubs.”

“You dance because you want to be free,” says Arnold. But what if this freest of spaces is only superficially so? At the heart of partner dance, and particularly Latin partner dance, is a set of

cultural norms that silently push women into the following role and men into the leading role. The coupling of gender and role is at odds with our current society’s stance on gender and power.

It’s not just that gender nonconforming individuals don’t fit in the gender binary or partner dance, but that cis-gendered queer and straight women and men are prevented from exploring the lived experience and self-discovery that the opposite role might offer.

While the gender norm affects everyone, I argue it disempowers cisgendered, feminine women in a specific way: Unlike gender-

nonconforming folks who might identify and question the norm from the get-go, most cisgendered women and men fail to see the gender norm in the first place.

Women in particular are ushered into the lighter end of the dance’s power balance* and are funneled into self-reinforcing patterns of behaviour and thought which push them deeper into following and away from leading.

It’s not surprising then, that in a survey I conducted of 25 women in Latin partner dance in NYC, 76% reported to be interested in leading. In my time in the field I also often heard women’s implicit and explicit desire to lead.

I believe that all dancers should have access to experiencing the joys of Latin partner dance as leaders and followers. I wanted to explore if helping women to access leading could be the pathway to break the gender norm for eveyone.

The gender norm is a system built on mental models and individuals’ patterns of behaviour. I believe that to break the system we must intervene directly in partner dancers’ experience.

In the next chapter of this book, I’ll be walking you through a night of partner dance. I will address four barriers towards leadership that women face at different moments of the experience, from arrival through to departure, through a suite of design interventions.

My first goal with this multidisciplinary design thesis is to contribute to the muchunderstudied field of partner dance in an academic context. My second goal is to contribute in a design capacity, by reformulating the partner dance problems previously studied from a social-sciences perspective, into actionable design opportunities

created through dialogue with users. My third and final goal is to create innovative products that provide value to dancers from meaninful social grounds, and which—as a suite of products— contribute to a new, inspiring vision of what partner dance could look like and fundamentally be in the 21st century.

BARRIER: IGNORANCE

DanceCode is a kit for dance event organizations that color-codes wristbands according to dance roles. This prevents women from falling into the follower role unknowingly, by confronting all dancers with their options upfront. DanceCode also supports dancers in communicating their preferred roles through active choice. Ultimately, DanceCode facilitates an interaction based on stated preference instead of gendered assumptions.

At the heart of the perpetuation of the gender norm is ignorance. When dancers first get introduced to cosmopolitan partner dance, they simply don’t know their role options. Event organizers very rarely communicate to dancers what their role options and desired behaviours are. As a result, new dancers come into the space and infer the norms and appropriate behaviour from what they see around them. In Latin dance, what they are likely to see is gender normativity, and as social animals, we are likely to mirror that gender normativity. It is often only by the presence of role models in class or at events that beginner dancers will realize that they can lead, both in theory and in practice.*

Let me first share how the moment of arrival to the dance event looks like:

ARRIVAL

All dancers go through the same motions at the moment of arrival to a dance event. Dancers come into the space, pay the cover fee, or show that they have paid in advance (if that is an option). The clerk or cashier at the event will mark customers so that they can exit and re-enter the event at will. Most often, the cashiers use a paper event wristband, like the ones used at concerts and clubs, as a marking method.

*On a personal note, this is how I first realized that women could lead, back in 2017. In the past year (2022-23), I have stood on the other side of that experience, seeing women’s reactions of surprise, confusion, and admiration when I dance with them during class.

Valeria Benitez

Dancers pay for entry upon arrival.

“I automatically go into the follower role instead of the leader role.”

DanceCode supports dancers in their role (or roles) of choice.

While dancing is a “low risk space”, it often doesn’t feel like it for beginners. Imagine being overwhelmed by loud, foreign music, new steps or cues to memorize, and dozens of dancing strangers all seemingly “advanced” and comfortable in the space. This makes beginner men and women especially vulnerable to shyness and social pressure.

Under this pressure, it’s rare for a beginner to think, or want to pursue the non-traditional role for their gender.

By the time women become intermediate dancers, they are likely aware that women are allowed to lead. At this point they might have danced with women leaders in class and may have become curious about leading, However, intermediate women followers will likely not pursue leading at this point. They’ll think it is best to prioritize developing their following skills, which they might have finally begun enjoying, before getting into leading. I heard this argument from women at least twice in the field. This mindset is another representation of the single-role default in social dance, and it’s deeply misguided.

One reason for this is that developing skills in following only makes it harder to lead later on,

from an emotional perspective.

“Expertise” is ever elusive, and the comfort of following and the pleasure of developing skills and being praised for good following skills is positive reinforcement to stay on that track. A second reason is that leading requires a completely different set of soft and hard skills, as well as a network of friendly followers, which introverted, intermediate women followers often don’t have. What is additionally unfortunate is that, according to dance instructors, learning the non-traditional role for one’s gender makes dancers better at the traditional role. This makes sense if we consider the symbiotic nature of partner dance.

While I don’t think it would be good to force women to lead, or scare them away from following, I think there is an opportunity to encourage a soft entry into leading for intermediate dancers.

Advanced or experienced women dancers often are in the best position to actaully pursue leading. A this point they might be familiar with the community and might even have lead in a few classes. But at the social itself, women who lead have no way of communicating to others that they are open to leading. This means that women who want to lead must approach other dancers, to ask to be their followers.

Emma Housner

“It was a blessing that I ended up learning both roles simultaneously.”

Help dancers learn their options from the moment they walk into the space in a way that also helps dancers communicate what roles they are open to performing during the class.

In the past, dance organizers have invited dancers looking to dance in the opposite role to their gender, or dancers looking to perform both roles, to use a physical identifier. To my knowledge, identifiers have included pinnable buttons and rubber wristbands. In my 6 years of dance experience however, I’ve never been offered the option to identify my preffered role.

• Make all dancers subject to a common code that communicates role preference, instead of the default of to gender appearance.

• Use the event wristband already existing in the dance experience that all dancers participating in the dance experience already wear.

• Convert the wristband into an interface to communicate prefered roles though a color-code.

• Create supporting materials to help dance organizations efficiently transition from a single-color wristband interaction to a more complex interaction requiring dancers’ choice.

• Create an accessible service for dance organizations to order materials and refill

wristbands according to usage at their particular event.

This project went through many iterations of concept and prototype development.

Initially, the problem I landed on was that event organizers were not effectively communicating the desired norms of their space and available opportunities to new dancers. My first concept was an interactive code of conduct that new dancers would sign at the door on an iPad. The code of conduct would be unique to that event or dance organization, and it would be produced through consulting or on a custom-built platform that used AI to develop the codes. But upon sharing the concept and a low-fidelity prototype with two organizers, they found the solution problematic. “People are not going to want to sign a contract” said Christine, event runner of Bailamos Juntos Social. Also, I noticed that not many dance events use iPads as part of their check-in process However, the event runners I spoke with completely agreed with the problem and were excited to find a way to communicate norms and options to their clients. This meant it was time to pivot.

I looked deeper at the current moment of arrival at several dance events. Normally it’s done through pen and paper, an iPhone to review Venmo transactions, and—this is where I had the “aha” moment— event wristbands. When I ran this idea by Christine, she was enthusiastic, especially because she thought the messages on the wristbands could align to dance roles (lead/follow/both). I had heard about events using color-coded buttons and other signifiers to communicate roles, and I wanted my design work to be innovative. However, it seemed that in the Latin dance space, this practice was largely unknown, and, given Chirstine’s excitement, I thought it might be worth exploring.

For the first test of this service, I drafted short codes of conduct based on my conversations with Christine and my personal take on the values, goals, and audience of the event she ran. We tested these at her event. I was at the cashier’s table asking participants for their preferred role and placing the appropriate wristband on them. I gathered candid reactions of confusion and delight, mostly from nonbinary dancers and women. I also heard at least a few scoffs from men and defensive replies to my question from dancers of all genders

Testing results revealed that

dancers wanted the wristbands back, that it positively improved their perception of the event, and that the wristbands affected their interactions with other dancers. Some users reported however that the wristbands were “out of sight and out of mind,” and many did not notice the messages on the wristbands until prompted by the survey to give a reaction.

I carried out an A/B test at a blues dance event in NYC. One set of wristbands had messages on them, the other didn’t. Additional changes for this testing round included not putting the wristbands on dancers as they arrived, but instead handing them the wristbands for them to put on themselves.*

Results were similar to the ones of the first user testing round, although blues dancers were much less surprised about the concept of dance roles and their colorcoding. Overall, even dancers whose interactions weren’t affected by the wristbands wanted to see the wristbands at the next event. When asked why they wanted them back, Gavin replied “why not?”

The A/B testing also revealed that despite the new interaction model, dancers did not read the messages. Also, the particular venue where the blues dance event was held was so dark that the wristbands’ colors were almost completely lost.

*I thought this modification in the interaction between cashier and dancer might be the solution to making the messages on the wristbands be read (and perhaps a way to interact with a stranger to get a hand!)

Given the learnings from the previous two rounds of user testing, I dropped the custom message feature, and am now focusing on creating glow-in-the-dark colorcoded wristbands. This small detail might fundamentally alter the way dance event organizations interact with dancers upon arrival and departure. For instance, it might mean that wristabands need to be re-usable instead of disposable for the cost and enviornmental waste to be sustainable for organizations. A glow-in-the-dark CMF also might mean that the wristbands need to be re-charged which would require a UV charving kit and power.*

Dance organizations create an account at dancecode.com and purchase the generic starter kit or purchase a custom kit that reflects the organization’s branding. The starter kit includes: 300 wristbands (any combination of lead/follow/both), a wristband storage box designed for use at events, and wristband usage tracking sheets which organizers can scan to automatically upload to DanceCode.com for over-time demographics analysis. Customers can purchase refills on their account.

Since the night of the first prototype test, it was clear that this product had potential. Two event

organizers other than Christine were interested in the wristbands. One explicitly asked me what she could do to have them at her event. Another asked if there was a mailing list.

Word of mouth, or marketing DanceCode as part of a broader a certification of inclusive spaces, which would become a tool for businesses to differntiate themselves and to attract queer, gender non-conforming and women and men who are looking for safe spaces to practice non-traditional roles.

BARRIER:

Ladies Take the Lead is an experiential workshop for women in Latin partner dance. Designed in response to women’s struggle in traditional partner dance classes, this workshop allows all participants to practice both leading and following in a supportive, feminine space.

Classes are a core component of cosmopolitan partner dance. I consider them one of the strongest representations of the value of artistry, for the ways in which cosmopolitan dance draws from both professional partner dance and the European tradition of courtly partner dances.

Let me start by explaining how standard Latin partner dance classes in New York City work.

Classes tend to run immediately before the “social” or party, and are often complimentary with the cover for the social. In New York City, they are affordable, ranging from $10-20 per class. Classes tend to start at 8pm or 9pm and last for

45 minutes to one hour.

At the start of class, all leaders and followers copy the instructors for a short warm-up. The warmup usually includes basic steps and turns to the class’s specific advertised style of music. After the warm-up, instructors will ask leaders to pair up with a follower* and stand in a large circle. At this point, the instructor will begin teaching a “pattern” (meaning, a choreography or sequence of moves) that dancers will learn and practice for the rest of the class.

When instructors call “Rotate!” leaders move to the next follower and continue learning and practicing the pattern. This class structure where dancers remain in the same role for the entire class is one example of “single-

*Many Latin dance class instructors still use gendered language to reffer to leaders and followers as “ladies and guys” (or similar), although this is slowly changing due to several factors, including societal regard for gender neutral language, the queer Latin dance community, and individual dancers within the Latin dance community who use the more progressive language already standard in other styles of partner dance, like fusion, blues and swing dance.

Fig 1. Leaders pair with followers. Leader Follower

Fig 2. When instructors call “Rotate!” leaders move on to the next follower.

Fig 3. The leader to follower ratio in class is often uneven.

Fig 4. When paired up, many leaders are left without a follower.

Fig 1. Leaders pair with followers. Leader Follower

Fig 2. When instructors call “Rotate!” leaders move on to the next follower.

Fig 3. The leader to follower ratio in class is often uneven.

Fig 4. When paired up, many leaders are left without a follower.

(she/her), Latin partner dancer, “Women’s role choices in Social dance” survey respondant

Kayelee Fitts

“If I didn’t have someone to lead me, maybe I’d be forced to do it more and end up enjoying it.”

role” default, a pervasive mental model in the cosmopolitan partner dance scene, which Juliet McMains, PhD, a professor of dance studies at the University of Washington, introduced to me during one of our talks.

Most of the class is taught without music. This is because it is challenging to hear teachers over the music and because instructors don’t need the music to teach the pattern.

Instructors use “counts” to break down the pattern into sets of moves grouped in eights. Counts are a practical tool for instructors and students, but by removing the dancing from the music, counts also represent the European-leaning view of dance as firstly technical, rather than the Black and streetdance legacy of dance rooted in connection to the music and its emotional interpretation.

The single-role structural default of partner dance classes’ design mirrors the gender norm in its binary nature. But it also upholds the gender norm in how it creates challenges for all stakeholders of the experience. Let me explain: It is extremely rare to find an equal number of leaders and followers in a class, but in Latin partner dance, it is exceedingly common that the leader-to-follower ratio leans heavily on the leader side.

This means that when dancers pair up for the pattern, many leaders are left without a follower. Below are the challenges that this creates for all stakeholders.

I’ve rarely seen a cisgender male in the follower role in a Latin partner dance class. From a numbers perspective, they would have an easy time finding leader partners in class. However, due to the stronger homophobia against men as compared to lesbiphobia, men wanting to follow also face barriers towards agency in role choice.

Men wanting to lead must often bear a portion of the class dancing without a partner. While suboptimal, this is not a terrible hindrance because leaders still get value from practicing the pattern on their own. Followers, on the other hand, don’t get anything from not having a partner in class since their role is responsive.

In class, women wanting to lead face the weight of the gender norms starkly. The main issue is social pressure. Social pressure in class can take the form of (1) selfcompliance, where women wanting to lead choose to follow because breaking the norm is so challenging,

impact on women wanting to lead

(2) covert pressure, such as hearing gendered language from instructors or getting odd looks from fellow participants, and lastly, overt pressure, which takes the form of teachers asking woman leaders to follow during the class to even out the leader:follower ratio; male leaders approaching women leaders without a partner and asking them to be their followers, and men leaders approaching women leaders currently partnered with a woman follower and asking them if they can split up.*

I’d like to note that many of these forms of pressure are not malicious, particularly in a progressive place like New York City. Instructors, organizers, and dancers are simply looking to have a fruitful experience for themselves or for their clients. The problem is that their actions, albeit innocent, draw strong, invisible barriers for the dancers who strive to go against the norm.

Women followers face the fewest challenges in class as they are often in high demand. Because of the responsive nature of following, followers don’t have to and, in fact, are encouraged not to memorize the pattern or to predict what move is coming. This is because partner dance in its true expression is improvisational, and leaders can’t practice improvisational leading if followers “backlead,” meaning, if followers don’t wait for the leaders’ movement cues. In fact this ease

turns out to be quite difficult for most beginner followers, who struggle to let go of the notion that they must “know the moves.”

I believe that part of the reason why there is a deficit of followers in classes is that, when followers reach the intermediate stage, they know all they need to know: basic moves and how to follow.**They know that they don’t need to know what’s coming—in fact, that they shouldn’t. So, the class stops being of value to them, and the social becomes a much better place to learn.

The instructors’ struggle is to manage a class with many more leaders than followers, which essentially means a product with many less-than-happy clients. I believe that instructors in the Latin partner dance scene either don’t know that a switch-role class is an option, which highlights the need for cross-style community and learning at all stakeholder levels, or they fear that a switch-role class structure will lose them business from cisgendered heterosexual dancers who are not open to dancing with the same sex or in the non-traditional role for their gender.

Outside of class-specific challenges, one of the barriers towards leadership that women face is the belief that leading is “not as

*You wouldn’t believe the amount of times I’ve heard versions of “oh that happens to me in dance class” or “I struggle with that a lot” or “I folded (meaning, gave in to the pressure to follow) the other day”, from women dancers accross many styles of dance.”

**I might have come to this belief based on my conversations with Sabrih Joy Short, an event runner of the Fusion Experience Social, who thinks it’s a problem that instructors only focus on what leaders are supposed to do in class, instead on what followers are supposed to feel.

“Male instructors never focus on what the follow is supposed to feel, they only focus on what the lead is supposed to do.”

(9). The emotional stakes grew when women did the same exercise with blindfolds. Aftwer switching, women discussed their experience in both sides of the power balance, and the vulnerability of both roles.

fun as following” or that it is “too hard.”

Funness and difficulty are subjective traits. They are not intrinsic to leading or to following. In fact, if leading was not fun, nobody would do it, right? Women have misconceptions about leading because the more they follow, the harder it gets to lead. The one exception here is that when followers reach “expert” level—which for many women is constantly a few months or years of practice away—they feel like they have the mental space to take up leading.

Based on the previous research and insights, I saw an opportunity to improve the following challenges and barriers women face at this stage of the experience:

• Make it a default for women to lead in class.

• Create a space where women don’t feel pressure to follow because of their gender appearance.

• Challenge women’s belief that leading is hard and not fun.

• Teach a switch-role class where all participants lead and follow.

• Create a women-only experience free of the gender norm.

• Create a supportive environment where the challenge of leading

will be matched with joy.

• Teach the soft skills often overlooked in standard partner dance classes.

• Give women the opportunity to re-think what following and leading are

The development of this project was rooted in theories of embodied experience, which argue that the human body, as our vessel of direct access into the world, is best suited for transformation. While dance is already an embodied action—and while partner dance is an interaction that affords great personal and interpersonal transformation—my challenge was to think about how to design a partner dance workshop that led participants to embodied emotional and cognitive change.

I first developed “movement” sketches to represent the feelings of confidence, freedom, and joy that I wanted participants to access during the workshop. In the process, I realized that confidence wasn’t really the problem, but rather the lack of external support for women to access training in leading. I believed that with support would come skills, and with skills, the confidence would follow. Based on my conversations with dancers and instructors, as well as my personal experience, I broke down the skills that leaders need in order to lead. Unsurprisingly,

these went far beyond basic steps and pattern-work. My takeaway was that in cosmopolitan partner dance, the best leading entails both technical and soft skills, and requires a balance of independence and interdependence with followers. It takes two to tango after all. From the follower’s point of view, it’s quite similar. Although the follower is responsive and rests on an unspoken “yes,” or acceptance of the movement cues coming their way, they still have personal agency and the power to communicate a “no.” I didn’t think that followers needed a reminder of their agency and their right to a “no” as much as they needed to experience it in practice. I also thought that this lesson about consent from the follower’s perspective should shift from a right to a responsibility. Because leaders can’t read minds. And it would be risky if we encouraged them to. Teaching followers their responsibilities in a context in which they could appreciate them from both points of view would be a testament to the follower’s bodily autonomy as an equal participant in the endless feedback loop that is the improvisational system of a partner dance encounter.* Partner dance is ripe with these complicated but exciting dualities!

BRANDING

For the look and feel of the

experience, I took inspiration from queer brands like lex to design a friendly, proud, but distinctly feminine brand design.

I advertised on several partner dance groups in NYC, posted flyers around the city at dance events, and created a free listing on Eventbrite.

Ladies Take the Lead occurred at Solas Bar NYC, a venue in Manhattan’s East Village with a long association with Latin partner dance. Solas Bar hosts partner dance classes and parties almost every day of the week. The dancefloor is accessed through a nondescript curtain in the back of Solas’ main bar. I thought the connection to the Latin dance scene in NYC, the slightly informal nature of the space (without the large mirrors and formality of dance studios), and the threshold of access through the curtain made the location a good choice for the workshop.

TIME

The workshop occurred on Thursday, March 23rd, from 6:30pm to 7:45pm, preceding the weekly 8pm sensual bachata class at the same location.

The experience welcomed women-identifying dancers of all experience levels.

The experience was split into three sections: discovery, generosity, and becoming. These sections were capped by an intake form and an outtake reflection. At the discovery stage, participants first learned to tune into their bodies and their interpretation of the music. To aid in this task, they did it while blindfolded. Here, the blindfold was a tool to prevent participants from looking at and comparing themselves to each other’s movement, forcing the eye inwards instead of outwards. Then, participants found a partner and practiced “mirroring,” a touchless form of leading and following with low stakes. I used mirroring as a warm-up into touch-based leading and following. Here, participants simply walked back and forth, for the first time feeling how their bodies could be used to direct others, and be directed by others. To spice things up, participants then repeated this back-and-forth walking exercise with blindfolds on, as the facilitator encouraged them to take note of how they felt in their respective roles and the vulnerability therein. Participants discussed how that experience felt afterwards, as blindfolded followers and seeing leaders.

After these relational exercises, the experience moved on to the discovery of bachata, the style of music that would be used for the rest of the experience.

To introduce bachata, I created a short pre-recorded audio that explained the origins of bachata music and dance, followed by a musical introduction to the five musical components of bachata music, inspired by the classic piece of music, “The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra”*, which introduces audiences to the distinctive sounds of each orchestra instrument.

The generosity stage aimed to incorporate the previously learned soft skills into the more standard components of a partner dance class. First, participants learned the basic steps of bachata in a short warm-up, and then learned a short pattern while rotating partners. The large change here was that before rotating partners, a couple would switch roles first, so that everyone got to lead and follow with each other.

The final stage of the experience was becoming, where all the soft and hard skills previously learned had a chance to come together in improvised practice with fellow participants. Here, the facilitator stopped calling out cues to “switch” or “rotate” partners, and participants were simply encouraged to interrupt dances with an invitation to dance with one of the partners.

This improvised practica or mini-social transitioned into a cheering party, where one or two couples dance in the middle of a circle of participants who clapped

Valeria Benitez

“I’m capable of leading and I should have more confidence to continue to do so.”

in support of their fellow women leaders.

The experience wrapped up with a video survey that asked dancers three questions:

• React to the workshop in three words.

• What’s ONE thing you’re taking away with you today?

• Do you think differently about leadership now vs. when you walked in?

These were accessed through a QR code on a take-away card showcasing the experience’s branding and the inspirational quote from the beginning of this book.

Participant and collaborator reactions were positive. They described a great energy, and feeling better than when they came in. The participants who joined from the bar asked if the workshop was happening again in the future.

From the video survey responses, participants used the following words to describe the exprience: “fun,” “challenging,” “energizing,” “safe,” “consent,” “thoughtprovoking,” and “enlightening.”

Personal reflections on leadership included Valeria’s, who said that “[she’s] capable of leading and should have more confidence to continue to do so.” Nihaarika, a firsttime partner dancer, learned that “leadership is not just about being

in charge, it’s about being a really good listener.”

While reflecting as a group after the official end of the experience, it came to my attention that brand new dancers wondered what it might be like to lead a man.

As I departed from the venue, two men at the bar who were waiting for the Thursday night bachata class asked me if I would do a workshop for men.

These two points make me believe there is an opportunity to create a similar experience with switch-role mechanics that is open to dancers of all genders, OR to create an experience with singlerole mechanics where women lead the whole class and men follow the whole class. I think that testing these class dynamics in a safe and supportive enviornment might be even more enlightening, humbling and transformative for individual dancers and the Latin dance community at large.

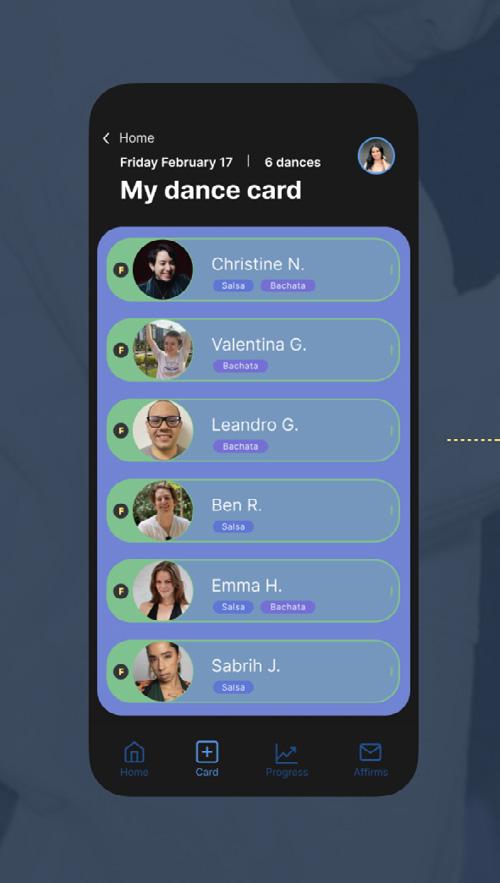

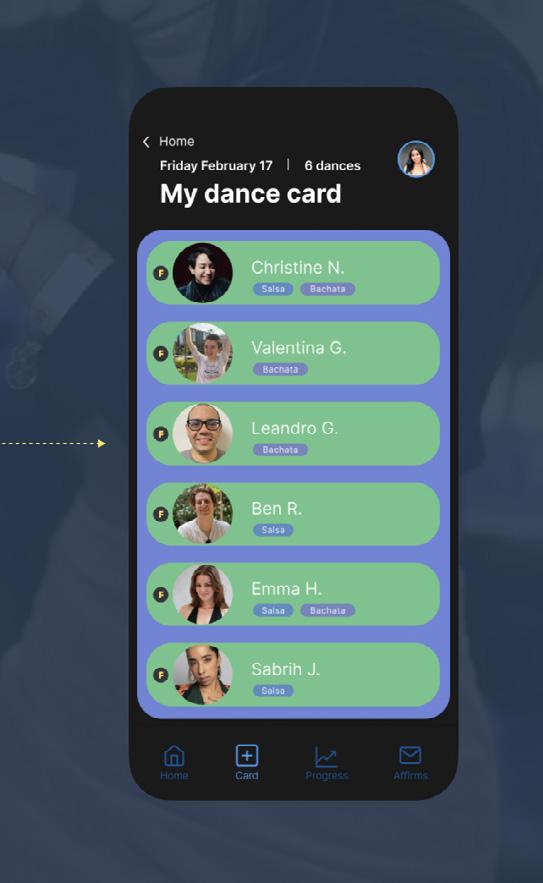

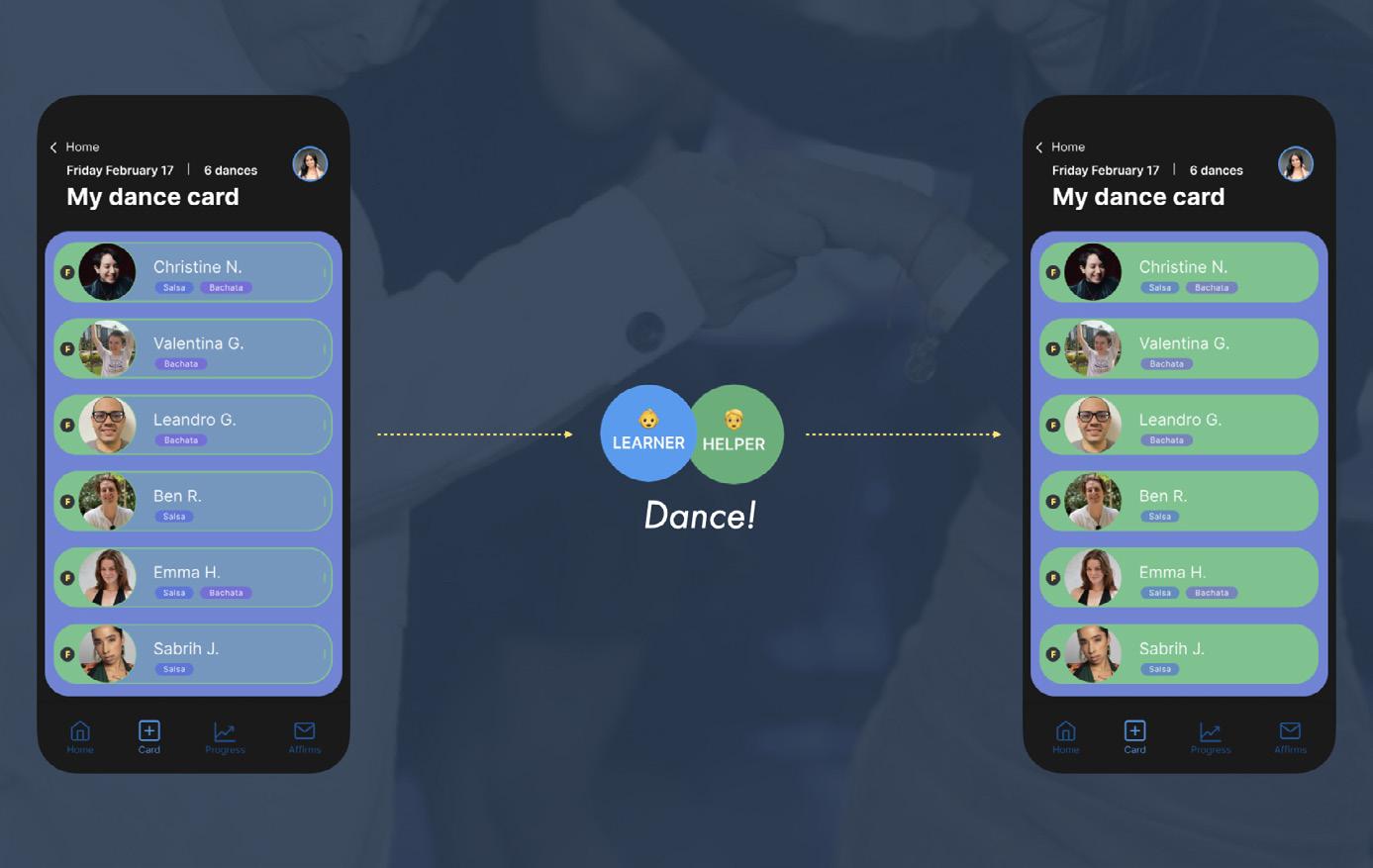

BARRIER: LACK OF SUPPORT

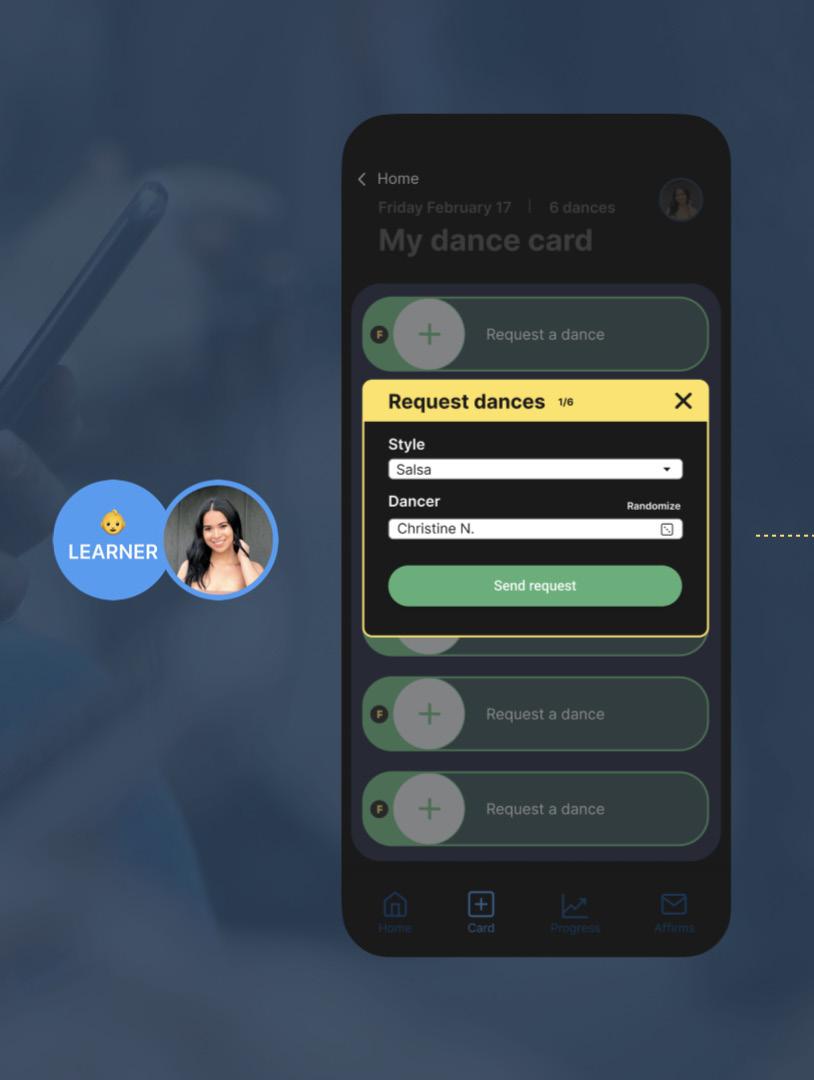

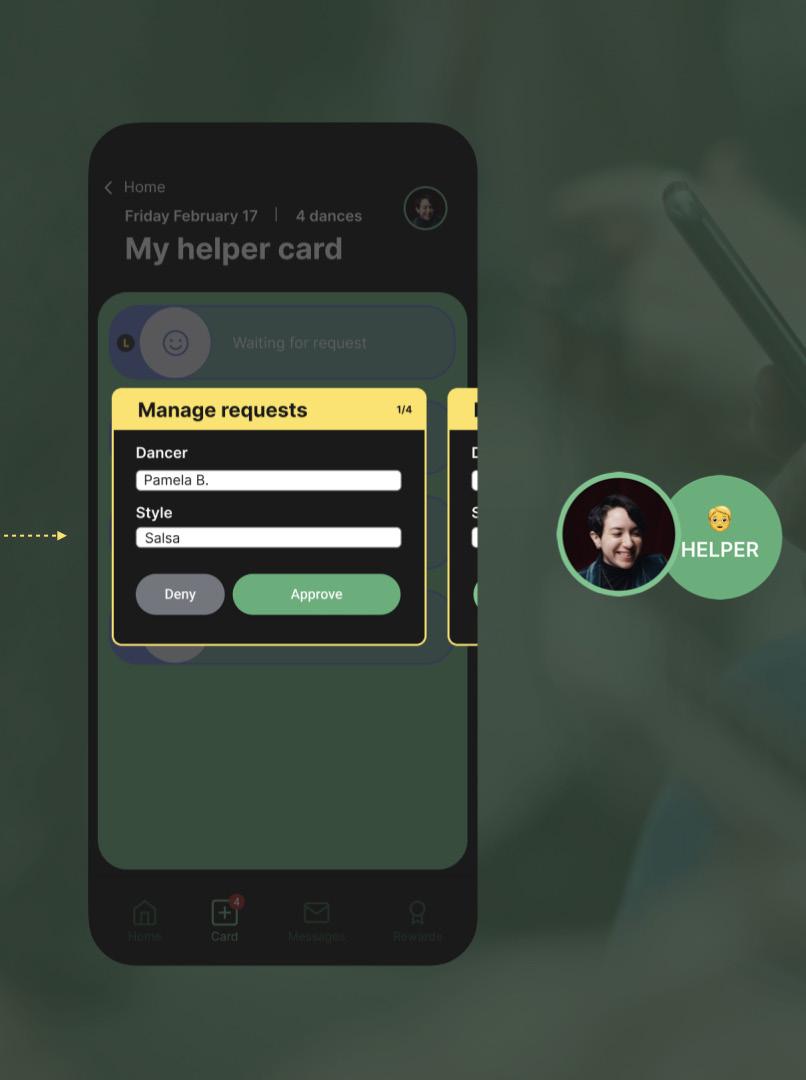

Lineup is a digital dance card that helps beginner dancers find willing partners to practice with at the “social.” Lineup functions as a platform with three user types: Learners, Helpers, and Businesses. Learners are dancers looking to learn the non-traditional role for their gender. Helpers are intermediate or advanced dancers eager to help beginners in nontraditional roles. Businesses are dance organizations who run dance events.

Asking for dances is emotionally taxing for beginner women leaders. Women plan out who they will ask to dance and—even then— panic up until the moment when they actually do it. This stems from the norm in partner dance where followers receive invitations to dance instead of doing the asking, which acts as an access barrier for beginner women leaders looking to practice what they might have learned in class.

The fear of rejection is worse than the fear of asking for a dance. An uneager verbal “yes” that feels like a “no” during the dance itself hurts women leaders’ confidence the most, often resulting in them sitting on the side or going back to the safety of following for the rest of the night.

PRODUCT FEATURES

LEARNERS

• Create a dance card with the desired number of practice dances.

• Track AI-recommended practice areas gathered from Helpers’ anonymous affirmations and feedback.

HELPERS

• Track and claim rewards set by Businesses to encourage Helpers to use the app.

BUSINESSES

• Add suggested class curriculum topics based on practice areas currently tracked by Learners who attend their events.

(she/her),

Sabrih Joy Sortevent runner, the Fusion Experience Social

“Me and my friends often don’t lead enough at socials. We only know a few moves. I told them I don’t care.

You give yourself a number, the number is three, you’re going to lead at least three dances today.”

Dancers wearing clothes without pockets have a harder time connecting with and building community in partner dance. This often means— women. Tenera is a wearable phone holster that makes it possible for those wearing dresses, skirts, or other non-pocketed clothing to exchange contact information immediately after a dance ends.

Tenera’s feminine design celebrates the affordance for expressivity of the partner dance space, which cisgendered women highly value. But Tenera also makes a statement about the need for embracing femininity in leadership. We can get women leading, and even men following, but if dance roles remain associated with femininity and masculinity, there will still be no place for those who reject these binary forms of expression.

Tenera is designed with the practical and aesthetic sensibilities for partner dance in mind: it’s adjustable, can be worn on different body parts, and is secure.

I rapidly prototyped several versions of a phone holster and shared these with users and SMEs. They were preocuppied with the practical features of the product, such as how to keep it in place and make it comfortable.

I drew inspiration from joint injury wearables, sports holsters, fashion holsters, and fannypacks. I also looked at visual depictions of strong, stealthy women, such as Lara Croft and other women superheroes.*

Jackson Lee

“I think that partner dancers move differently through the world.”

Ibegan this thesis with a hunch: There was something rotten laying underneath the charm of partner dance and I felt that it was critical to understand what it was and how to fix it.

I couldn’t put into words the reasons why this was important, though. Why pay attention to Latin partner dance, a niche, leisurely activity?

Nine months later, I have no doubt that cosmopolitan Latin partner dance is worth all our efforts.

Cosmopolitan partner dance has the rare ability to affect society at two levels: the individual and the collective. At the individual level, partner dance is a healing haven of endorphins, movement and

expression. “I notice the impact on my mental health,” stated Junaid as we waited for the Thursday bachata class to start at Solas Bar in NYC.

At the collective level, partner dance affords a barrier-breaking encounter with people of other races, socio-economic standings, genders, and sexual orientations.

In Notes on Funk II, Adrian Piper wrote about how she used funk dance lessons to immersively educate whites on Black popular culture. For Piper, partner dance was an embodied tool to reduce an unwarranted fear of blackness, or racism, based on ignorance.

Latin partner dance, which is currently growing in global popularity at an impressive speed, can only reach its true potential

for individual and social impact if partner dance spaces are made inclusive. Given the demographics of the current market, it makes sense to leverage women’s desire to lead and systematically intervene in the dance experience.

Change is waiting to happen. If organizers want business, they can’t afford to be exclusionary. Organizers who have wanted to break the gender norm in the past, and deem themselves “safe” spaces, have not gotten very far because they’ve been missing the point: Inclusivity is an active effort that takes tools designed for that purpose.

Change is waiting to happen!

Cisgendered dancers are starting to welcome roles into their experiential repertoire that society had deemed “not for them.” And these dancers want to support the queer community.

The challenge, then, is to design and implement tools for inclusivity that leverage the power of organizers and instructors, and to not let the curiosity of dancers who just might give the other role a shot go unsupported.

I think the strong word of mouth of the dance world will take care of the rest.

I believe this approach will, over the long term, rewrite the mental models that constrain women and men to the role binary, and as

a result, create access to the full spectrum of dance experiences for all dancers, regardless of gender.

As a niche community, cosmopolitan partner dance is not in the eye of academia, of social innovation or of venture capital. But it should be.

Bailamos Juntos Social

Latin dance event (mostly salsa) IG @bailamosjuntossocial

Passion Thursdays

Latin dance event (mostly bachata) IG @Passion_thursdays

Fusion Experience Social Latin dance event (mixed) IG @fusionexperienceofficial

Blues Dance New York Blues dance event bluesdancenewyork.com

Sensual Movement

Latin dance event (sensual Bachata) IG @sensual_movement

Emma Housner

Latin dance instructor housnere@gmail.com

Indigo Dawn (they/them) Consent culture consultant mxindigodawn@gmail.com

Stephanie Shapiro Wedding dance choreographer stephanie@dancewellny.com

Swagchata (Brian + Andrea) Latin dance instructors IG @swagschata

Valentina Giovannini

Latin dance instructor IG @valentina_56

media

Ismael Fernandez

Photographer ismaelf@me.com

Christine Nieves

Photographer cnievesphoto@gmail.com

Cyntia Abarca

Catalina Albornoz

Ace ArenasVasquez

Nihaarika Arora

Arshlavi Auleear

Pamela Bacian

Emily Baltz

Valeria Benitez

Brianna Brooks

Kate C.

Arnold Cabrera

Kummar Chandan

Inessa Chernomaz

Jaemin Cho

Allan Chochinov

Erika Choe

Michael Cheung

Michael Chou

Josh Cintorino

Giancarlo Cipri

Alexia Cohen

Bill Cromie

Indigo Dawn (they/them)

Alex De Looz

Alessandro Ferdico

Ismael Fernandez

Maria Andrea Garcia

Leandro Gil

Valentina Giovannini

Sarah Hackett

Emma Housner

Abdiel Jacobsen

Sabrih Joy

Julia Knoll

Ogochukwu Ononiwu

Jackson Lee

Kimaya Malwade

Marko Mariquez

Achi Martin

Corey McClelland

Juliet McMains PhD

Val Meneau

Xhercis Méndez

Kristine Mudd

Christine Nieves

Amelia Perry

Sam Potts

Sabrina Ramos

Rohitha Remala

Ben Rigney

Camila Rocha

Sinclair Scott Smith

Stephanie Shapiro

Charvi Shrimali

Amalia Sirica

SVA VFL staff

Kaylan Tran

Cathy Tung

Krissi Xenakis

Helena Yang

“Are you Afraid to Identify as a Leader?” Harvard Business Review, September 5 2022. https://hbr.org/2022/09/are-you-afraid-to-identify-as-aleader

“History of Dance: Universal Elements and Types of Dance - 2023MasterClass.” Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.masterclass.com/ articles/history-of-dance.

“Sexual Exploitation Was the Norm for 19th Century BallerinasHISTORY.” Accessed April 3, 2023. https://www.history.com/news/sexualexploitation-was-the-norm-for-19th-century-ballerinas.

Albornoz, Monica “Women’s role choices in Social Dance - 2min Survey” https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/ d/16DbpAyrcEnawZyB0g5HkS57IwQFs_Q4qb-Vj5fhiXgY/edit?usp=sharing

Beggan, James, and Allison Pruitt. “Leading, Following and Sexism in Social Dance: Change of Meaning as Contained Secondary Adjustments.” Leisure Studies 33 (September 1, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367

.2013.833281.

Bisexual Lighting: The Rise of Pink, Purple, and Blue. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8gU3IA4u-J8.

Brandstetter, Gabriele, Gerko Egert, and Sabine Zubarik. Touching and Being Touched: Kinesthesia and Empathy in Dance and Movement. Berlin/ Boston, GERMANY: De Gruyter, Inc., 2013. http://ebookcentral.proquest. com/lib/sva-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1130408.

Brown, Brene. Dare to Lead: Brave work. Tough Conversations. Whole Hearts. Random House: Audiobook, 2018.

Butterworth, Jo. Dance Studies: The Basics: The Basics. New York, UNITED KINGDOM: Taylor & Francis Group, 2012. http://ebookcentral. proquest.com/lib/sva-ebooks/detail.action?docID=957902.

Chapelain, Aurelie. “Bachata Musicality - The Traditional Instruments in Bachata.” Let’s Dance Bachata (blog), April 14, 2022. https:// letsdancebachata.com/bachata-musicality-the-traditional-instruments-inbachata/.

Chou, Will. “How Dancing Taught Me How To Take The Lead In A Relationship As A Man” Will Chow’s Personal Development Show - Motivational Life Advice https://willyoulaugh.com/how-to-lead-in-arelationship

Dancetime! Social Dance Vol 1: 15th-19th Centuries: Research Section of the Video Showing Original Sources for the Dance Steps.

Anonymous Dancetime Publications, 2016. https://www.proquest.com/ audio-video-works/dancetime-social-dance-vol-1-15th-19th-centuries/ docview/1864597341/se-2.

Dancing Through New York in a Summer of Joy and Grief - LEAFYPAGE

Del Valle Schorske, Carina “Dancing Through New York in a Summer of Joy and Grief”, The New York Times Magazine, Sept. 22, 2021 https://www. nytimes.com/2021/09/15/magazine/dancing-new-york-summer.html

Donato, Joe “How to Lead like a Man” Ballroom Joe, 2007 http://www. ballroomjoe.com/articles/followinglikealady.htm

Donato, Joe “How to Lead like a Man” Ballroom Joe, 2007 http://www. ballroomjoe.com/articles/leadinglikeaman.htm

Google Docs. “Interfusion Festival & Community: Incident Reporting Form.” Accessed February 3, 2023. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1

FAIpQLSfk40in6W8FuafQ60687RigX_O6vflHYUnhoVjhs1BjT-qobg/ viewform?usp=embed_facebook.

Hackman, Richard J. “Why Teams don’t Work” Harvard Business Review, 2009. PDF https://danceplace.com/grapevine/followers-women-and-sexism/

Julia Lee Cunningham, Laura Sonday, Susan (Sue) Ashford

Kaminsky, David. “Geographies of Gender: Social Politics of the Partner Dance Venue.” Dance Research 38, no. 1 (May 1, 2020): 25–40. https://doi. org/10.3366/drs.2020.0289.

Lovatt, Peter; Bussell, Darcey. Hosted by Giselle Parker. The Power of Dance. Podcast audio. July 2020 https://www.peterlovatt.com/power-ofdance/.

McMains, Juliet. “Fostering a Culture of Consent in Social Dance Communities.” Journal of Dance Education, 2021, 1.

MCMAINS, JULIET. “Rebellious Wallflowers and Queer Tangueras: The Rise of Female Leaders in Buenos Aires’ Tango Scene.” Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 36, no. 2 (2018): 173–97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90025984.

NYC Senior Zouk Social Community Code of Conduct, https:// www.notion.so/NYC-Senior-Zouk-Social-Community-Code-of-Conductb693b7fdc76a443c95f255174f3f151

Piper, “Notes on Funk I–IV,” in Out of Order, Out of Sight, 1:195-216 Riva, Laura “Followers, Women, and Sexism” The Dancing Grapevine, 2021.

Riva, Laura “Sexism: Is it an issue in social dance?” The Dancing Grapevine, 2016 https://danceplace.com/grapevine/sexism-is-it-an-issue-insocial-dance/

Sandberg, Sheryl, and Nell Scovell. Lean in: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. First edition. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013.

Skinner, Jonathan. “THE SALSA CLASS: A COMPLEXITY OF GLOBALIZATION, COSMOPOLITANS AND EMOTIONS.” Identities 14, no. 4 (2007): 485.

Steps on Toes Dance Lessons. “Is Partner Dancing Sexist?,” November 6, 2013. https://www.stepsontoes.com/leading-and-following/is-partnerdancing-sexist/.

The Dancing Grapevine. “Followers, Women, and Sexism,” June 12, 2021. https://danceplace.com/grapevine/followers-women-and-sexism/.

The Dancing Grapevine. “Sexism: Is It an Issue in Social Dance?,” June 8, 2016. https://danceplace.com/grapevine/sexism-is-it-an-issue-in-socialdance/.

Wulfhart, Nell McShane. “It’s Never Too Late to Learn the Tango and Fall in Love.” The New York Times, July 21, 2022, sec. Style. https://www. nytimes.com/2022/07/21/style/its-never-too-late-to-learn-the-tango-and-fallin-love.html.

Monica is a Colombian-born designer with a passion for applying a strategic and systems lens to any challenge. She has collaborated on product development with the MoMA design store, built visual identities for quantum computing enthusiasts at Xanadu, strategically innovated digital sales for an e-commerce retailer and produced handmade dinnerware for Michelin-starred restaurants. In the past, Monica has been a holder of the O-1 visa for exceptional artistic achievement, launched Moaz Ceramics, her own line of ceramic products, and been pretty decent at speaking German.