“It’s no coincidence that ‘aspiration’ means both hope and the act of breathing. When we speak, we use the breath in our lungs to give our thoughts a physical form. The sounds we make are simultaneously our intentions and our life force.”

—from Exhalation by Ted Chiang

2

PANORAMA 2024

Welcome to the 32nd edition of Panorama!

Panorama is a curation of work from students of the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania’s Weitzman School of Design. In this year’s edition of Panorama, we want to ask the question, “What’s in a future?” Who takes stock of the present and shapes change? What ideas and images move us forward?

As planners, preservationists, designers, and urbanists, we find ourselves studying the past with our eyes on the future. Panorama features student work that grapples with this condition by exploring topics and offering recommendations on local and global scales. Through writing, map making, and design, students explore topics such as affordable housing policy, free speech on public transit, Urban Outfitter’s use of the phrase “urban renewal,” federal energy policy, and much, much more.

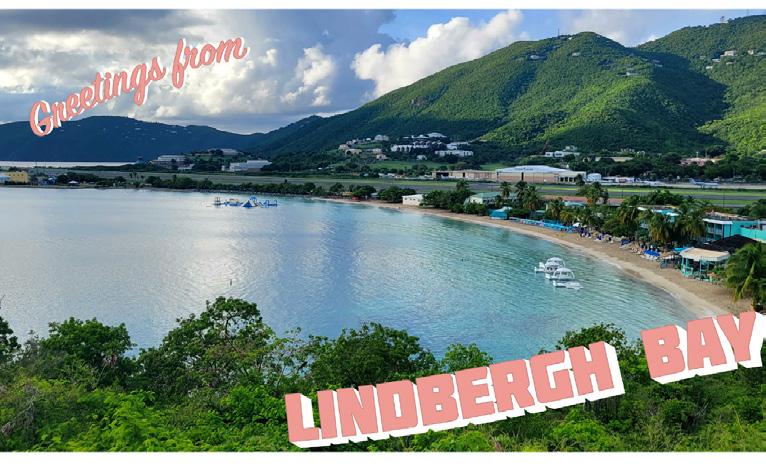

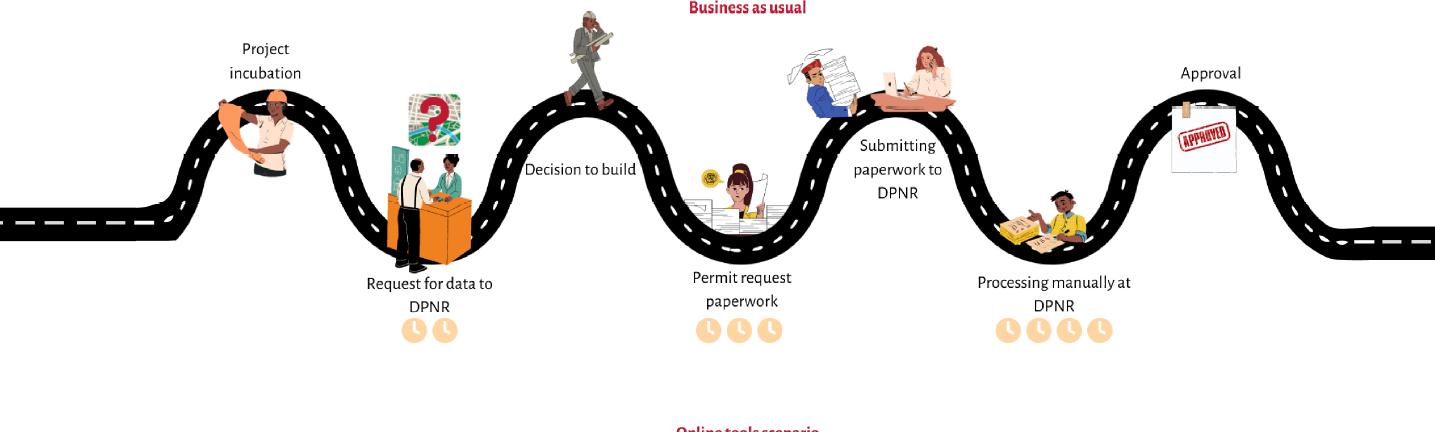

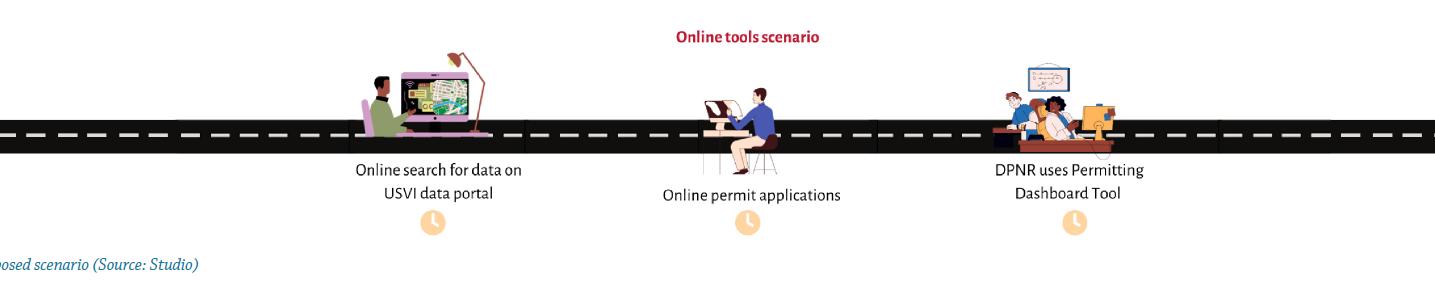

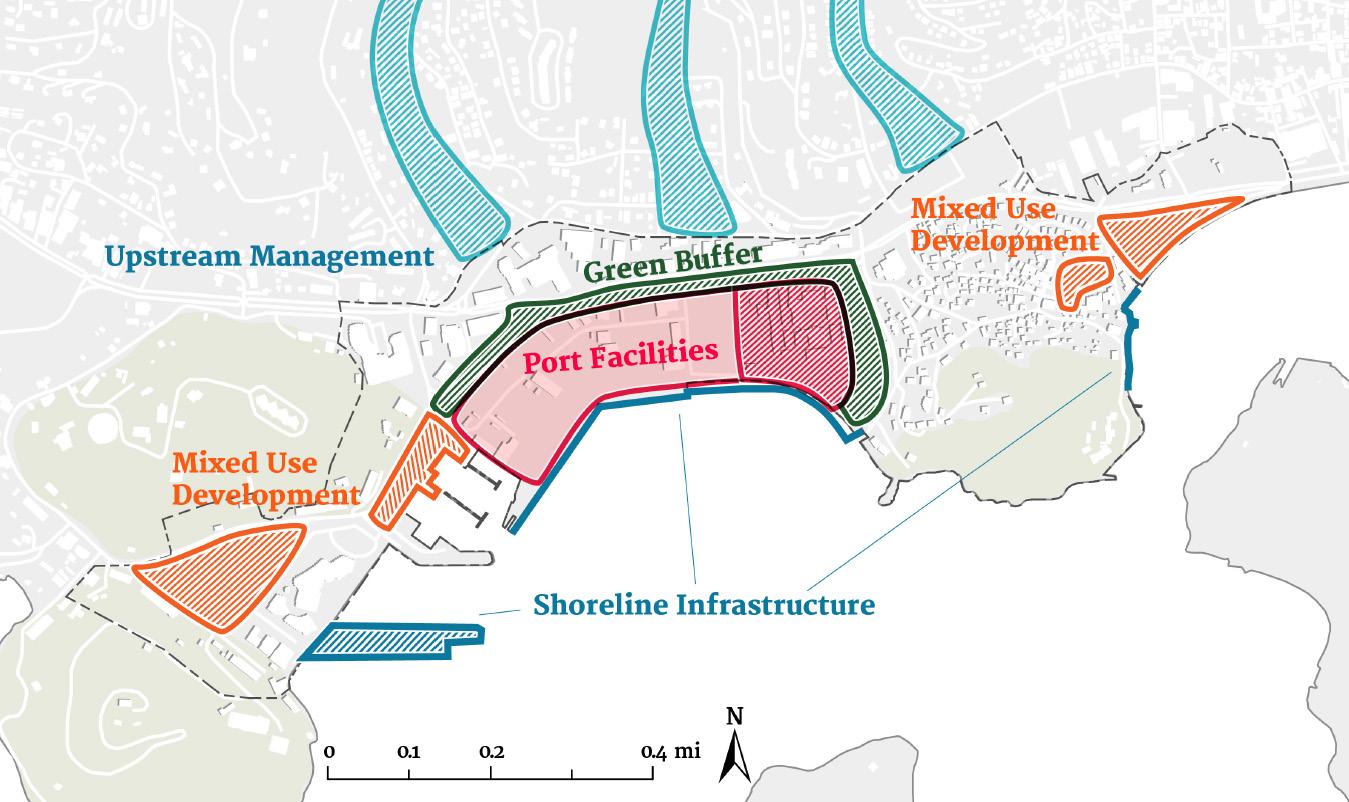

Panorama 2024 also features studio work from the Weitzman School’s Fall ’23 semester, including recommendations for Philadelphia’s summer of 2026, when the city will host games for the FIFA World Cup, the MLB All Star Game, and the nation’s 250th anniversary celebration; strategic planning for the intersection of land use and mass transit in Bogota, Columbia; urban design for climate resiliency in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands; and design for equity and trauma informed planning at West Philadelphia’s Sayre High School.

This edition of Panorama aims to open dialogue about the critical issues that all of us, planners or not, witness in our everyday lives, be it social inequity, housing crises, underfunded transit systems, or accelerating climate change. The future of planning is shaped when we share our work, have open conversations, and move forward together. We have thoroughly enjoyed bringing together this edition of Panorama and we hope that when you turn the last page, you feel challenged, informed, and hopeful for our future.

With hope, and in solidarity,

Dr. Lisa Servon

Kevin

and

Erica

Penn Presidental Professor and Chair of the City & Regional Planning Department

Bailey Bradford

Katie Hanford

Revathi V. Machan

Claudia Schreier

Jeff Tseng

Jonathan Zisk

Panorama Editorial Staff

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE?

3

Meet the Panorama 2024 Editoral Team

Katie Hanford, Copy Editor

Bailey Bradford, Design Editor

Bailey (he/him) is a second-year Master of City Planning student with a focus in Sustainable Infrastructure and Transportation Planning. He is passionate about the role of transportation accessibility and equity in building safe, climate-resilient, and vibrant communities. Prior to becoming a graduate student, he developed paid digital media campaigns for clients such as the Georgia Democratic Party and Voto Latino. When not browsing bus network maps, he is probably deep in a new dinner recipe or playing Beyoncé’s Renaissance on loop.

Katie is a second-year Master of City Planning student concentrating in Housing, Community and Economic Development. After studying anthropology as an undergraduate, Katie worked for a few years in the nonprofit sector, focusing on youth development and community support. Katie is interested in the intersection of culture, power, and community-led design, specifically how communities come together to create urban space that fits their needs. When not people-watching, Katie spends her time playing/listening to all things heavy, watching ‘90s romcoms and finding the best food and drink deals Philly has to offer.

Revathi V. Machan, Content Editor

Revathi (she/her) is a first year Master of City Planning student concentrating in Housing, Community, and Economic Development. Prior to coming to Penn, she studied landscape design and environmental policy. Currently she is exploring the intersection of data and design to drive connection between communities through human-centered infrastructure and greener public spaces. When not lost between lines of code and/ or plans, you can find her working on tattoo commissions, upcycling her clothes (or wrecking them—depending on your perspective), and exploring new places in the city.

4

Jeff Tseng, Design Editor

Claudia Schreier, Copy Editor

Claudia (she/her) is a first-year Master of City Planning student with a focus in Smart Cities. Prior to coming to Penn, she worked in the clean tech and coastal resilience fields. Claudia is passionate about emerging technologies that promote equity and sustainability in the city. She holds a BS in Oceanography from the University of Delaware (Go Blue Hens!). Outside of school, Claudia is slowly completing her mission to enjoy a cold brew at every independent coffee shop in Philadelphia.

Jeffery is a first-year Master of City Planning student concentrating in urban design and pursuing a certificate in Real Estate Design and Development at the Wharton School. He is an aspiring urban designer, landscape architect, planner, and future developer aiming to enhance the quality of life and connection between people and the environment in the public realm. He hopes that through sustainable design and development, we can combat the environmental impacts and injustices experienced by contemporary urbanism. When he’s not worrying about real-world problems, you can find him at the Penn gym playing pickup basketball with his mates.

Jonathan Zisk, Content Editor

Jonathan is a second-year Master of City Planning student concentrating in sustainable transportation and infrastructure planning. He comes to Penn with experience working at the School District of Philadelphia and at Philadelphia’s Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity. Jonathan has an English degree from Reed College in Portland Oregon and also attended Deep Springs College in California. He believes that cities are remarkable spaces for sustainable and equitable life and wants Chestnut and Walnut Streets to be permanently closed to cars. If you have any questions, you can find him in Clark Park at 6:30pm every Wednesday.

IN A FUTURE? PANORAMA 2024

WHAT’S

6 08 Embracing Diversity:“Little ASEANs” in Greater Taipei by Tao Chen 30 What Happens When You Have a Picture of the Entire World? by Jonathan Zisk 80 Absorb, Adapt, Thrive by Elaina Geiger 94 Energizing Progress by Laura Frances 116 Bogotá: Equity & Expansion Fall ‘23 Studio 52 Philadelphia 2026: A Legacy Planning Framework Fall ‘23 Studio 16 Am I Clean Yet? by Revathi V. Machan 38 In Love with the Details by Brianna Belo 88 Flooding in Ghana’s Volta Region by Sylvanus Narh Duamor 108 Corredores Viales & Fare Capping by Leo Wagner 130 Between Data & Experience by Alexa Ringer 72 Stabilizing a City through Seed by Bakari Clark Table of Contents

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE? 7 PANORAMA 2024 142 Stop Requested by S. Amos 156 Navigating Smart City Pilots by Emmy Park & Laura Frances 202 A Place for All? by Katie Hanford 216 Industrial Legacies & Open Space by Junyi Yang 228 Tu fu, an exile in Berlin by Nissim Leibovitz 170 Climate Resiliency in the U.S. Virgin Islands Fall ‘23 Studio 144 Free Speech in Transit by Leah Martins-Krasner 164 Echoes of Bias by Shuai Wang 214 Left Foot, Right Foot by Revathi V. Machan 220 Sayre High School Fall ‘23 Studio 230 Urban Renewal: “What’s in a Name?” by Claudia Schreier 190 Staring Down Speculators by Elam Boockvar-Klein

Diversity Embracing

by Tao Chen

“Little ASEANs” in Greater Taipei

by Tao Chen

“Little ASEANs” in Greater Taipei

The tapestry of Taiwan’s cultural and urban landscapes is in a state of profound transformation. The growing presence of Southeast Asian communities and the government’s encouragement of inclusivity contrasts with historical efforts by the post-World War II occupying regime to impose a homogeneous “Chineseness.” 1 The emerging Southeast Asian communities challenge traditional Confucian-Taoist-Buddhist paradigms and are prompting Taiwanese society to reevaluate the perceived monoethnic environment entrenched during decades of Kuomintang (KMT) rule. Nowhere is this metamorphosis more evident than in the vibrant “Little ASEANs”2 that have flourished throughout Greater Taipei, reshaping both the physical urban landscape and bringing new vitality into neighborhoods.

Much like Chinatowns and Asian Strip Malls in the US, the presence of Southeast Asian establishments such as stores, restaurants, churches, and services in Greater Taipei offer a comforting sense of familiarity and cultural affirmation for different diaspora groups.3 They serve as a home away from home to the growing diaspora population, catering to the diverse needs and desires of their clientele. These services are particularly important in the context of Taiwan’s aging (and shrinking) population and the reluctance of Taiwanese youth to engage in certain sectors like manufacturing and caregiving.4

...emerging Southeast Asian communities challenge traditional Confucian-Taoist-Buddhist paradigms and are prompting Taiwanese society to reevaluate the perceived monoethnic environment...

During my visit to Mie Ayam Indostar, a modest eatery near Taoyuan Station (a city just southwest of Taipei), the often bustling crowds of Javanese factory workers and caregivers for Taiwan’s rapidly aging population were noticeably absent on a quiet Thursday afternoon. Run by a lovely mother-son duo, this establishment represents a part of Taiwan’s burgeoning “new resident” (新住民) population, a term encompassing foreign spouses, migrant workers, and their children, who have embraced Taiwan as their home.

Mie Ayam Indostar offers a straightforward menu, albeit at relatively higher prices compared to the norm in Taiwan (where a typical bento box would cost less than $100 TWD, or $3.25 USD). Nonetheless, customers appreciate the authentic flavors and warm atmosphere when they visit after work, as evidenced from glowing reviews on platforms like Google Maps5 and

IN A FUTURE?

WHAT’S

9 PANORAMA 2024

TikTok.6 The addition of a grocery section at the back further enhances the restaurant’s appeal, providing aa sense of home for Indonesians longing for familiar products.

While Mie Ayam Indostar primarily caters to the Indonesian community, the restaurant also strives to reach out to Taiwanese customers. With the rise of online food influencers and the convenience of delivery apps like UberEats, more and more Taiwanese locals are showing interest in exploring the rich flavors right in their own neighborhood. Over at Cres-Art Philippine Cuisine in Taipei’s “Little Manila” within Zhongshan District, Imelda, the owner, shared with me how she has seen a growing number of Taiwanese patrons keen on indulging in Filipino delicacies. As I savored my halo-halo (a Filipino cold dessert), Imelda also mentioned the necessity to diversify her customer base, especially as an increasing number of Filipino workers seek employment in the regions south of Taipei.

These “Little ASEAN” areas and their culinary establishments not only help different diaspora groups maintain their identities, but also foster the formation of new ones. Just like Asian malls in the United States that foster a sense of “Pan-Asian” Asian-American identity where diverse backgrounds

10 EMBRACING DIVERSITY: “LITTLE

GREATER TAIPEI

Little Myanmar, or Nanyang Sightseeing Food Street in Zhonghe District, New Taipei (photo by Tao Chen)

ASEANS” IN

converge, Little ASEANs have played a similar role for Taiwan’s “New Immigrants.” This is especially evident in the grocery stores and other services found within these communities, where offerings transcend Southeast Asian boundaries, including goods from Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand. Additionally, remittance-sending and package delivery services cater to the needs of the diverse Southeast Asian countries represented.

Little ASEANs serve as a powerful reminder that vibrant communities do not emerge in isolation but are the result of a complex interplay of historic dynamics and deliberate policies implemented by various levels of government. The establishment of Taipei’s Little Manila, for instance, can be traced back to the founding of St. Christopher’s Church by American parishioners, which held the distinction of being the sole English-speaking Catholic church in Taipei for many decades. This unique institution acted as a magnet for the Filipino community, creating a nurturing environment that fostered a strong support network and provided a sacred space where cultural and religious practices could thrive and be preserved.7

Similarly, the presence of “Little Myanmar” in New Taipei’s Zhonghe district and the significant Burmese-Thai community in Taoyuan’s Longgang district can be attributed to the historical ties between the KMT and northern Myanmar and Thailand. Following their defeat in the Chinese Civil War, thousands of KMT troops crossed the border from the southwestern Chinese province of Yunnan and seized control of the northern Burmese provinces.

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE?

11

2024

English and Tagalog signs at the King Wan Wan Shopping Center (Tao Chen)

PANORAMA

12

Indonesian, Burmese, and Thai items at a grocery store in New Taipei’s “Little Myanmar” (photo by Tao Chen)

EMBRACING DIVERSITY: “LITTLE ASEANS” IN GREATER TAIPEI

There, they sustained themselves through the opium trade and laid the foundation for what would later become known as the Golden Triangle. After being evacuated in 1960 to Taiwan, these soldiers and their families were resettled in Zhonghe and Longgang, where their unique heritage and experiences continue to shape the fabric of these communities.8

These days, Southeast Asian stores are seamlessly integrated into the urban fabric of Taipei, in many cases extending beyond designated “Little ASEAN” areas. Near Taipei Main Station, at the western end of the underground Taipei City Mall,9 an array of Indonesian restaurants, telecom services, and grocery stores has flourished, even outnumbering Taiwanese establishments in the vicinity. This “Indonesia Street” has helped reinvigorate an otherwise struggling mall.

Moreover, malls like the King Wan Wan Shopping Center in Zhongshan District have transformed into thriving business hubs for diverse Southeast

These communities epitomize resilience, adaptability, and extraordinary journeys.

Asian communities, empowering Taipei’s Filipino community in the face of persistent challenges of migrant worker discrimination and racism.10 The increasing popularity of Vietnamese cuisine has led to the proliferation of Vietnamese restaurants and food carts throughout Taiwan, reflecting both the significant Vietnamese community and the growing Taiwanese appreciation for the flavors of Vietnam. So much so, even FamilyMart, a Japanese convenience store chain with over 3,600 locations in Taiwan (second only to 7-Eleven’s 6,500), has recently introduced a dedicated “Southeast Asian” section to cater to the diverse tastes and preferences of its customers.11

The Little ASEANs of Greater Taipei illuminate the historical forces shaping social and cultural landscapes. These communities epitomize resilience, adaptability, and extraordinary journeys. It is crucial to recognize the deliberate policies and historical ties that underpin their formation. Policymakers globally should prioritize embracing and supporting diverse communities, respecting and celebrating their unique needs, aspirations, and cultural identities. Moreover, it is essential to acknowledge and cater to the distinct groups within diaspora communities to ensure that their individual needs are fully met. The presence of Little ASEANs in Greater Taipei stands as a testament to the transformative power of embracing diversity, challenging traditional notions of identity, and offering invaluable lessons to policymakers worldwide, spanning all levels.

A FUTURE?

WHAT’S IN

13

PANORAMA 2024

Endnotes

1 Karvelyte, Kristina. 2022. “The Chineseness of Urban Cultural Policy in Taiwan.” Asian Studies Review 168-185.

2 The Association of Southeast Asian Nations

3 Lung-Amam, Willow S. 2017. “Mainstreaming the Asian Mall.” In Trespassers?: Asian Americans and the Battle for Suburbia, by Willow S. Lung-Amam, 98-137. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 99

4 Hsueh, James C T. “Taiwan Heading into Its Super-Aged Era.” East Asia Forum, March 4, 2023.

5 Mie Ayam Indostar · Yanping Rd, Taoyuan District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan 330.

6 TikTok. “X I N L IIDTW on TikTok.” Accessed February 22, 2024. https://www.tiktok. com/@xinli_78/video/7224862354352246022.

7 Lin, Eric. 1999. Taipei’s “Little Philippines” St. Christopher’s Catholic Church. December. Accessed February 19, 2024.

8 阿美米干(A-Mei Migan). n.d. 異域孤軍大事記 (Major Events of the Lonely Army in a Foreign Land). Accessed February 20, 2024. https://amay.com.tw/about/ourheritage/.

9 One of many underground malls linking metro stations in Taipei

10 Lin, Yumei. “Southeast Asian Migrant Workers in Taiwan: Human Rights and Soft Power | New Perspectives on Asia | CSIS,” September 28, 2023.

11 陳立儀 (Li-Yi Chen). 2023. 首波40店搶先開賣!全家便利商店南洋酸辣燙「馬 尚煮」強勢登台 冬蔭功湯+10款海味食材自由配 (“First Wave of 40 Stores Launch Sales! FamilyMart Introduce Southeast Asian Spicy Hot Pot ‘Tom Yummy’ - Tom Yam Kung + 10 Seafood Ingredients for Customization”). United Daily News. November 8. Accessed February 22, 2024.

About the Author

Tao Chen is a Master of City Planning candidate at the University of Pennsylvania’s Stuart Weitzman School of Design, concentrating in housing, community, and economic development. His primary interest lies in the intersection of climate resilience, global development, and post-conflict recovery.

14 EMBRACING

GREATER TAIPEI

DIVERSITY: “LITTLE ASEANS” IN

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE?

15 PANORAMA 2024

A bowl of mie ayam bakso (Indonesian noodles with diced chicken and beef meatballs) at the aptly named Mie Ayam Indostar near Taoyuan Station (photo by Tao Chen)

Am I Clean Yet?

Perceptions of Sanitation and Cleanliness in Colonial Systems

by Revathi V. Machan

by Revathi V. Machan

Cleanliness is next to godliness, or so they say. In a post-pandemic era, where hand sanitizer is our holy water, and Clorox wipes our sacrament, there has been a renewed effort to build cleaner cities. Beneath these seemingly noble intentions, however, lurks a dark history rooted in racial prejudice and social control that has codified our urban planning ideologies. Exploring the intertwined history of sanitation and planning, this piece delves into the story of how sanitary reform reshaped not only our cities but also our perceptions of cleanliness, citizenship, and belonging.

Let’s start at the beginning (of urban planning). Sanitary reform essentially birthed urban planning, making sanitation theorists the first iteration of urban planners. The concept was a byproduct of the Industrial Revolution and the rapid growth it brought to cities with no regulations for sewerage, housing, water systems, and other aspects of public health. When people are packed together like sardines in poorly constructed buildings with no established sanitation systems, diseases, such as tuberculosis and cholera, like to run rampant.1 And death generally follows.

Enter, the filth theory – the idea that filthy physical conditions associated with the urban informal settlements fostered diseases. 2 At the time, it was also believed that poor living conditions created individuals of poor constitution, i.e., the poor, the sickly, and the disabled suffered those conditions because of the physical environments they lived in. European health officials took this unique opportunity to remove a city of all its ills – physical and social – through spatial reorganization. This particular concept refers to a collection of different practices that would sanitize an area of physical congestion and environmental ills by removing informal settlements, creating a grid street system, and establishing waste management practices.3 After all, it’s much easier to sanitize a city than it is to tackle systemic inequalities, right? So, off the sanitationists went, clearing out those pesky informal settlements and creating grid street systems like some sort of urban Marie Kondo, tidying up our cities one eviction at a time. This implementation of sanitary measures spatially cleansed history, systems, and power. And by proxy, cleansed people of their cultures, identity, and agency.

“This implementation of sanitary measures spatially cleansed history, systems, and power. And by proxy, cleansed people of their cultures, identity, and agency.”

IN A FUTURE?

WHAT’S

17 PANORAMA 2024

“Cleaning” the Colonies

The Progressive Movement entered the scene shortly after the filth theory era, sweeping across Europe and the Americas in the early 1900s. Orderly and efficient planning principles based on the “scientific” principles of sanitation were believed to be the most efficient way to cure all physical and social ills. In spaces already established like Europe and the U.S., there was a lack of opportunity to put these theories into practice. Although there were still areas of Europe that underwent demolition and reconstruction, like Paris and Manchester, these changes paled in comparison to those implemented in the colonies. Sanitation theory maintained that a limited physical space caused social ills in a population – if you were white and living in Paris. In colonies, it was a different story. It was believed that the only way to manage the “cesspools of filth” was to sanitize the lands, in which “sanitizing” meant completely destroying and “lands” meant the settlements of the poor, minorities, or colonized (which in a colony means all of the settlements). Colonial cities were “laboratories” for much more extreme versions of sanitary reform,4 but also stages for shows of socio-political and economic power over colonized populations.5 As is standard to colonization lore – these demonstrations of colonial power and sanitary environments were rooted in racist ideologies.

Colonists developed the delightful notion that people of color were considered inherently dirty because of any variance that othered them –different waste management practices, resource distribution systems, and spatial organizations. In fact, colonists that entered tropical territories would often “[turn] their new tropical frontier into a desolate human-waste land, imagining everything “brownwashed” with a thin film of germs.”6 Lovely. All these variances were in one way or another inferior to the systems that had been developed by the colonists. The systems that existed in colonial cities were simply different from what Europeans had established in their cities, such as the grid streets in Paris7 and sewer system in London.8 No matter how well-built any of the native systems were, their status as “other” belittled them and sullied them in the eyes of colonizers. Of course, this demanded colonial interference to civilize and cleanse those systems.

Colonial Interference Strategies

Strategy #1: Demolition

In Delhi, colonial officials tore down nearly three-fourths of the city to remove the “[congested area’s] evil influence upon civilized society.”9 What was really removed were spatially established social systems for markets, healthcare, and sanitation. These clearances were meticulously regulated,

18 AM I CLEAN YET?

observed, and calculated, but were determined entirely by colonial administration. The demolitions did offer a solution to the health and safety concerns of the city, but the lack of distinction between areas of disease and areas that presented political challenges (rebellions and disloyal factions) is telling of the true purpose - to establish dominance over the Delhiites.10 Because nothing says civilization like destroying indigenous systems and imposing your own, right?

Strategy #2: Preservation

When the French colonized Morocco in 1912, Protectorate Hubert Lyautey wanted to develop the colonizers’ settlements around the established city. “The vulnerable, formalized bodies of the American colonialists demanded sanitary quarantine.” 11 The French quite literally drew lines in the sand between their new establishments and local settlements, tastefully referred to as “sanitary corridors.” 12 All of the “dirty” Moroccans were clustered together away from the development and technology that the French brought into Morocco – but only for sanitary reasons.13 Black Moroccans could and were encouraged to live within the white settlements but only if they assimilated wholly to the French ideologies and culture. Of course this was just an option and Moroccans could make their own choices. I guess “preservation” and sugar-coated assimilation tactics also say civilization.

Though colonialism was implemented differently across the world, one of the main recurring themes was that colonizers were entering dirty, congested, unplanned spaces that were directly due to the nature of the natives. I’m not sure if you, my Reader, are aware of the basic tenets of statistics, but let me inform you. Cause and correlation are not the same thing. Whether or not colonizers knew this, they didn’t care. Their main goals was to establish power and control in these spaces, using whatever guise they could use.

The violent spatial reorganization14 and the establishment of a racial hierarchy reinforced ideas of social differentiation and segregation between the Indians and the British.15 The system of preservation in Morocco established segregation and hierarchies where Europeans obtained infrastructural benefits in the name of creating a safe, hygienic space for themselves. Through many similar repeated processes across the world, sanitary reform took the ideology of “race is tied to cleanliness” and institutionalized it. Creating a clear precedent “based in science” for all those who came after to refer to as a blueprint for colonization and urbanization.

Immigration to the U.S.

Apart from the legal codification of sanitary reform, the idea of race being dirty became codified into the identities of many colonized cultures over

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE?

19 PANORAMA 2024

time. Cleanliness wasn’t just next to godliness, but also next to whiteness. The way sanitary reform was implemented blurred the lines of what was being sanitized. It wasn’t just the physical environment or lived practices that were dirty. Every group that looked different from the ruling class began to hold a warning sign of being filthy. Minorities were considered sullied by the act of existing. The connotation of their unrefined, and irrational, and uncivilized ways followed their identity regardless of where they went, especially in their immigration to the United States. As people of color began migrating to the U.S, one thing was made clear: the only way to address this dirtiness was to assimilate completely to Western (read: white) ideologies or forever be marked as dirty, uncivilized, and unworthy. This was seen throughout the entire immigration process, from before an immigrant even stepped into the country all the way to several generations of assimilation later.

Before an Immigrant Even Stepped into the U.S.

The 1880’s saw a dramatic increase in the number of immigrants arriving on U.S. shores.16 People were coming from all corners of the globe for

20 AM I CLEAN YET?

“Bracero workers being fumigated at Hidalgo Processing Center,” photograph by Leonard Nadel, Texas, 1956. Smithsonian Museum of American History.

the land of opportunity and fresh starts. If those immigrants had been able to get those opportunities as easily as I was able to write that sentence, we could’ve ended the paper here. Alas.

The federal government established a law around then that required immigrants to undergo medical examinations by U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) medical officers.17 The goal here was “to prevent loathsome or dangerous contagious disease” from entering the country by conducting these inspections – a goal established by the federal agency.18 The goal interpreted by PHS officers on the ground was “to prevent the entrance of undesirable people –those ‘who would not make good citizens.’” 19 Of course, the inherent goodness of an individual is easily and immediately visible to a racially-biased, officious government official. Naturally, the origin of the immigrant would determine how violating the medical inspection would be. Standard procedure would dictate that the PHS physician would conduct a visual check of prospective immigrants to find any obvious physical signs of physical or mental illness. 20

Non-Europeans (Latin American and Asian immigrants) faced many more medical obstacles to gain entry. 21 Stripped, showered, disinfected, searched for lice. At some immigration stations, Mexican immigrants would be required to strip naked, bathe, and then be sprayed with gasoline or other pesticides (sometimes containing DDT) to kill lice before they even underwent the physical examination. 22 You know how it is, get fumigated to get initiated— the real motto of the PHS. DDT, by the way, is the pesticide that was nationally banned in 1972 because it was so toxic and persistent in the environment that it was killing off the bald eagles. Also a known carcinogen. Migrant workers who commuted across the border as part of the 1943 Bracero Program for their work were subject to this kind of treatment daily. 23 Sanitation became a violating and necessary part of assimilation.

After an Immigrant Stepped into the U.S.

Cleanness being the only way to enter and assimilate to the country was hammered in early on and quickly became an involuntarily accepted condition of many different immigrant cultures in the U.S. The large waves of immigration sparked much fear in U.S. nativists – who could’ve guessed. 24 Immigrants either had to assimilate, repent, or be punished. Assimilate

German Jewish immigrants who arrived in the early 1800s spent decades seeking respectability by Americanizing their self-image. The construction of their synagogues – the most noticeable representation of the community – exhibited more Christian and cruciform qualities over time. And as their architecture assimilated to the surrounding community, so did their

IN A FUTURE?

WHAT’S

21 PANORAMA 2024

congregations. Traditional practices like chanting, praying in German vernacular, and participatory congregations evolved into singing hymns, praying in English, and observer-based congregations – reformed to Protestant practices of worship. 25 German Jews not only Americanized themselves, but they also distanced themselves from orthodox Russian Jews that entered the U.S. in the 1900s. The “distinctive language, un-American appearance, and ‘backward ways’” of the Russian Jews created a divide formed by the inherited ideology that refusing to assimilate was a threat to the community. 26

Repent

Hindu and Indian immigrants that moved into San Francisco in the early 1900s were simply considered “culturally ‘unassimilable,’” a condition that was determined by a discrete and profound analysis of their homeland: “a land under a ... threefold curse that of the caste system, of gaunt-eyed famine, and of poison-breathing plague.”27 Maybe I can put down “descendent of land cursed threefold” on my Hinge profile as my fun fact. Accusations like this weren’t always disputed by the community. In public newsletters, some Indians acknowledged the “backwardness and superstitions” that had become ingrained into the Hindu culture through British colonization. 28 These traits were accepted as truth - not a fault of their own but something to be ashamed about regardless. The public nature of these admissions was another indicator of the level of their penitence – maybe if they bowed their head enough in apology, the Americans would look right past them and allow them to exist peacefully.

Punished

“Immigrants and minority communities have long been stigmatized as “dirty,” perpetuating discrimination in policies from immigration to housing. Understanding these issues’ roots is key to building truly clean, equitable, and inclusive cities.”

Chinese immigrants who entered the U.S. in the late 1800s often congregated in Chinese-only neighborhoods, using these carved out spaces to hold onto their culture, traditions, and systems – power to them. 29 One of the consequences of this non-assimilation was extreme ostracism. During the third wave of the bubonic plague in the 1900s, entire Chinese communities were quarantined or forcibly inoculated on the basis that their living

22 AM I CLEAN YET?

PANORAMA 2024

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE?

conditions (and inherently them) were dirty, carriers of disease and plague.30 When the first victims of the plague died in Honolulu’s Chinatown, eight entire blocks went under lockdown, trapping 10,000 Chinese, Japanese, and Native Hawaiian people.31 After the first German (white) woman became infected and died, the city’s public health officials decided that even more drastic actions were necessary. They burned down every house in Chinatown that they suspected of harboring victims of the plague.32 The fire burned for 17 days and left 4,500 Chinatown residents homeless.33 Residents of Honolulu’s Chinatown had refused to assimilate or repent for their otherness and were punished for it.

The first step toward lightening the White man’s burden is through teaching the virtues of cleanliness. , 1899. Photograph. (Source: US Library of Congress)

23

Several Generations of Assimilation Later

Throughout U.S. immigration waves, many immigrants faced overcrowded, underfunded living conditions, a recurring theme for immigrant and minority communities. During the peak of tenement housing, immigrants, barred from various neighborhoods, resorted to living together to save money as rents soared due to predatory landlords. In Los Angeles, male Chinese immigrants bunked together to cut costs.34 In NYC, Sicilian immigrants played housing Tetris, fitting four families into a four-bedroom apartment to afford rents consuming 30 to 50% of their incomes.35 Meanwhile, Mexican and Puerto Rican immigrants in Chicago struggled for decent housing, often forced into overcrowded, unsanitary conditions, further policed for their plight.36 This cycle didn’t end with tenement housing’s decline. Cue the American suburbs post-World War II, where government-backed mortgage programs like the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) touted homeownership as a path to prosperity—reserved, of course, for white folks!37 These policies explicitly excluded people of color, perpetuating segregation, and limiting opportunities.38 White families fled to the suburbs faster than you can

24 AM I CLEAN YET?

Fires in Honolulu’s Chinatown (Source: Hawaii State Archives)

say “white flight”, leaving minority and immigrant communities stranded in disinvested, impoverished inner-city neighborhoods.

Notice the parallels between early immigrant struggles and those of later inner-city dwellers, blamed for their living conditions while facing systemic barriers. Ever hear someone criticize a city for being “unclean”? Maybe it’s time to ponder why it’s unclean in the first place.

Today, the legacies of discriminatory housing policies endure, shaping America’s spatial wealth distribution. Communities of color still confront barriers to safe, affordable housing, perpetuating cycles of poverty and segregation reminiscent of past injustices.

So, as we embark on yet another quest to build cleaner cities, let’s not forget the lessons of the past. Cleanliness might be next to godliness, but it’s definitely next to a whole lot of racism and social inequality. The historical connection between sanitation, urban planning, and racial prejudice underscores their enduring legacy today. Sanitary reform has been tainted by racism and social control, reshaping cities to the detriment of marginalized communities. As we strive for healthier cities post-pandemic, we must confront this legacy head-on. Environmental justice, equity planning, and dismantling systemic racism must be at the forefront of urban planning. Immigrants and minority communities have long been stigmatized as “dirty,” perpetuating discrimination in policies from immigration to housing. Understanding these issues’ roots is key to building truly clean, equitable, and inclusive cities.

Endnotes

1 “Causes of Illness and Disease - The Effects of Industrialization.” BBC News. Accessed March 11, 2024.

2 Troen, Ilan. “Urban Reform in Nineteenth Century France, England, and the United States.” Tel Aviv University, 1988, 1-18.

3 Ibid

4 Hosagrahar, Jyoti. “Sanitizing Neighborhoods.” In Indigenous Modernities: Negotiating Architecture and Urbanism, New York: Routledge, 2005. 83-113

5 Njoh, A.J. Urban Planning and Public Health in Africa: Historical, Theoretical and Practical Dimensions of a Continent’s Water and Sanitation Problematic. 1st ed. Routledge, 2012.

6 Anderson, Warwick. “Excremental Colonialism: Public Health and the Poetics of Pollution.” Critical Inquiry 21, no. 3 (1995): 640–69.

7 Chapman, Brian. “Baron Haussmann and the Planning of Paris.” The Town Planning Review 24, no. 3 (1953): 177–92.

8 Otter, Christopher. “Cleansing and Clarifying: Technology and Perception in Nineteenth‐Century London.” Journal of British Studies 43, no. 1 (2004): 40–64.

9 Hosagrahar, Jyoti. “Sanitizing Neighborhoods.”

10 Ibid.

11 Anderson, Warwick. “Excremental Colonialism.”

12 Wright, Gwendolyn. “Tradition in the Service of Modernity: Architecture and Urbanism in French Colonial Policy.” Journal of Modern History (1987): 291-316.

IN A FUTURE?

WHAT’S

25 PANORAMA 2024

Donna. From Sicily to Elizabeth Street: housing and social change among Italian immigrants, 1880-1930. (Texas Tech University, 1984), Chapter 5.

Rodríguez, Alexa. “‘Imperial Circuits’ and the Boundaries of a City: Puerto Rican Migration during the Mid-Twentieth Century,” Journal of Urban History 0, no. 0 (2023).

36 Gioielli, Robert. “The Tyranny of the Map: Rethinking Redlining,” The Metropole, 2022, accessed February 10, 2023.

37 Ibid.

38 Scott Markley, “Federal ‘redlining’ maps: a critical reappraisal,” Urban Studies 61, no. 2 (2023): 195-213.

About the Author

Revathi (she/her) is a first year Master of City Planning student concentrating in Housing, Community, and Economic Development. Prior to coming to Penn, she studied landscape design and environmental policy. Currently she is exploring the intersection of data and design to drive connection between communities through human-centered infrastructure and greener public spaces. When not lost between lines of code and/ or plans, you can find her working on tattoo commissions, upcycling her clothes (or wrecking them – depending on your perspective), and exploring new places in the city.

13 Ibid. 14 Archer, John. “Colonial Suburbs in South Asia, 1700-1850.” In *Visions of Suburbia*, edited by Roger Silverstone, 26-54. London: Routledge, 1997 15 Hosagrahar, Jyoti. “Sanitizing Neighborhoods.” 16 “Medical Examination of Immigrants at Ellis Island.” Journal of Ethics, American Medical Association. Accessed February 26, 2024. 17 Ibid. 18 Ibid. 19 Ibid. 20 Ibid. 21 Ibid. 22 Ibid. 23 Nadel, Leonard. Bracero workers being fumigated at Hidalgo Processing Center. Photograph. Washington DC, 1956. 24 Moffson, Steven. “Identity and Assimilation in Synagogue Architecture in Georgia, 1870-1920.” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, 151-165. 25 Ibid. 26 Library of Congress, “Building Communities: Chinese Immigration and the United States Capitol,” Classroom Materials, accessed March 2, 2024. 27 Sen, Arijit. “Architecture and World Making: Production of Sacred Space in San Francisco’s Vedanta Temple.” South Asian History and Culture (2010): 76-102. 28 Ibid. 29 “That Rotten Spot.” Distillations Podcast, Science History Institute. Accessed February 20, 2024. 30 Ibid. 31 Ibid. 32 Ibid. 33 Ibid. 34

Gabaccia,

35

26 AM I CLEAN YET?

27 PANORAMA 2024

Margolies, John. Colonial Theater, angle 2, Seaside Heights, New Jersey. United States New Jersey Seaside Heights, 1978. Photograph. WHAT’S

IN A FUTURE?

Window to Another World

by Kamya Khandelwal

The artwork depicts an intriguing contrast between the industrial and ethereal in Philadelphia’s Mantua neighborhood. Crafted for a site planning class, this photomontage frames a vibrant sky within the urban structure, hinting at a hidden dimension in the cityscape—a profound reminder of beauty beyond the visible.

About the Author

Kamya is an architect and urban planner with a knack for designing cities that feel like home and playgrounds for the child in everyone. Her tools are a love for design, data, and a keen ear for community needs. Off-duty, you’ll find her immersed in music, expressing life through photography and art, or enjoying a swim. Recently, swing dancing has caught her fancy - life’s all about balance, right? With a deep affection for the sea, I’m eager to merge my design work with marine conservation and climate resilience initiatives down the line.

IN

FUTURE? 29 PANORAMA 2024

WHAT’S

A

What Happens When You Have a Picture of the

Google Streetview, Ed

Ruscha,

and the optics of urban change

Entire World?

by Jonathan Zisk

In 2014, Google subtly introduced a new feature to Streetview: the ability to toggle between different dates of panoramic imagery. The results were nothing short of extraordinary. Via any internet browser, Streetview users could suddenly watch the world change before their eyes. Google’s tweak to their user interface dropped a visual time machine into our laps, and the city planning world has only scratched the surface of this tool’s potential. Streetview’s innovation comes in the form of scale and access. Its panoramic images of streetscapes are more extensive and accessible than any made before, yet follow in the path of conceptual precursors who displayed the power of capturing and recapturing urban panoramas. Ed Ruscha’s Sunset Strip project is preeminent among those. Ruscha made regular panoramas of Los Angeles’ Sunset Boulevard for over 40 years, and in doing so captured the evolution of the street’s changes, from the mundane to the monumental. Ruscha’s Sunset Strip project is an illustration of the potential that Streetview has granted to its millions of daily users, with uses from data mining and machine learning to urbanist activism and gaming. All of these uses are enabled by the trove of information that exists in sharing photographs of our built environment.

An attempt to photograph the world: Google’s temporal streetscapes

Besides a fascination with technical achievement, a curiosity for the world, and Silicon Valley hubris, it is unclear why Google undertook Streetview. Streetview spun out of a Stanford engineering project and began by trying to photograph every street in San Francisco using Google founder Larry Page’s personal car. Early results were merely “interesting,” but didn’t gain internal buy-in until the project was greenlit in 2005 and began development towards becoming a true Google product – the product being offered was a panoramic photograph that covered every road on earth.1

In 2010, Google engineers celebrated the fifth anniversary of the project and explained that “the idea of driving along every street in the world taking pictures of all the buildings and roadsides seemed outlandish at first, but analysis showed that it was within reach of an organized effort at an affordable scale, over a period of years—at least in those parts of the world where political systems make it possible.”2 Google does a poor job of articulating the utility of Streetview. Whether more extensive explanations are for internal use only, or if they go fully unarticulated is unclear. However, Google’s dedication to the project can only be explained by their recognition of the immense potential inherent in having an image from everywhere in the world.

Google Streetview has established a monumental data set of the built WHAT’S IN A

31

FUTURE?

PANORAMA 2024

environment. By the project’s 10th anniversary in 2015, it had taken 220 billion images and driven over 10 million miles across 100 countries.3 Vast swaths of the world are now available for exploration, research, and enjoyment from behind any computer or smartphone.

On top of their already unprecedent services, Streetview’s 2014 inclusion of historical images richened its offerings. In a blog post to announce the change, Google project manager Vinay Shet wrote that, “[t]his new feature can also serve as a digital timeline of recent history, like the reconstruction after the devastating earthquake and tsunami in Onagawa, Japan. You can even experience different seasons and see what it would be like to cruise Italian roadways in both summer and winter.”4

Though announced as a glorified software update, accessible historic Streetview imagery should be considered a notable moment in human history – Google gave its users the ability to visually go back in time and see how the world around us has changed. Almost two decades into Streetview, the project is robust as ever, with high-trafficked cities receiving new Streetview updates every few years. Any internet user, without paying extra or even having a Google account, can access this trove of temporal streetscapes. The results of the tool have been predictably diverse and ingenious.

Since its widespread rollout, Google Streetview has been used for day-to-day navigation, for data mining to assess urban environmental, social, and infrastructural conditions,5 for public health audits,6 for study of the behavioral psychology of navigation,7 and for use by artists who plumb its depths to select readymade images out of street scenes.8 Each of these uses capitalizes on Streetview’s tremendous trove of data to shape how we view the world.

Google Streetview images are used widely in city planning offices for existing conditions analyses and have become pervasive on social media for their ability to depict changes in urban policy. Housing advocates regularly engage with the effects of zoning reform on housing supply by sharing before and after images of increased density in urban spaces. These Streetview image pairings optimistically depict the speed with which urban spaces can change to address pervasive social issues. The images encourage viewers to think about the built environment as the product of tangible policy and social decisions, rather than as an unchangeable condition of city life.

“Streetview image pairings optimistically depict the speed with which urban spaces can change to address pervasive social issues.”

32

A PICTURE OF THE ENTIRE WORLD

Gamers study the built environment

However unexpectedly, online gaming has proven to be among Google Streetview’s most popular uses. Online gamers use the game GeoGuessr to study the non-monumental, under-appreciated quirks of our built environment, especially of the industrial vernacular architecture that lends our cities, towns, and rural highways unique characteristics.

Alton Wallen, a Swedish software engineer, launched GeoGuessr in 2013. The game taps into Google Streetview in order to use its imagery for fun.9

In each round, GeoGuessr randomly selects locations in Streetview and gives players the opportunity to guess where they are on a world map. The game was long a site for curious players to attempt an unbeatable and entertaining challenge. After all, there is no way to identify the location of any spot in the world. However, in the last few years, especially over the course of the Covid19 Pandemic, GeoGuessr players took up the challenge of getting better at the game than anyone imagined would be possible.

GeoGuessr has blossomed into a streaming juggernaut, with millions watching live game play and YouTube recordings of players who deftly sift through the forensics of a streetscape and pinpoint themselves across billions of possible locations around the globe. Professional Geoguessr player GeoRainbolt has gained prominence on TikTok by showcasing his ability to pinpoint Streetview imagery after seeing an image for less than a second.10

The game now has over 40 million accounts and the GeoGuessr community is one of the greatest forces for studying and cataloguing vernacular architecture across the globe, all for the purposes of satisfyingly navigating rounds of a competitive video game. Players study the way different countries

Photo by Matt Sylvester on Unsplash

Photo by Matt Sylvester on Unsplash

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE? 33 PANORAMA 2024

and regions erect bollards, tile their roofs, and string their telephone wires.11 In short, they are filtering the mountains of information contained in Streetview and identifying traits that make each part of the world stand out as simultaneously interconnected and unique.

While GeoGuessr pros catalogue and memorize the ways that different regions mark roadways and design cityscapes, they are inadvertently unveiling the limitless potential for how we can construct our built environment. Knowing that streets do not have to be built the way that we’ve always built them is a powerful idea. By facilitating a study of our differences, GueGuessr uses Streetview to help us see the built environment as a collaborative, progressive project.

Streetview’s predecessors

Google was not the first to try and take a picture of everywhere in the world. Urban panoramas have captured the curiosity of audiences for centuries, from Meiji Japan12 to 20th Century New York City,13 but technological advances have allowed temporal repetitions of these panoramas to showcase the dynamism of cities.

Prominent among Streetview’s predecessors is Ed Ruscha’s Sunset Strip project, which entailed the recapturing of panoramic images along Los Angeles’ Sunset Boulevard roughly every five years from the 1960s to the

70

Years of change in Los Angeles (Design by Jonathan Zisk)

Years of change in Los Angeles (Design by Jonathan Zisk)

34 A PICTURE OF THE ENTIRE WORLD

early 2000s.14 Ruscha, an American pop artist and conceptual photographer, approached the city with a deadpan aesthetic that proved invaluable for studying the modern American built environment. Ruscha’s work serves as a conceptual bridge between modernist street photography and the maximalist technocratic advancement of Streetview. Ruscha’s geographically-constrained Streetview-style project shows the dynamism that our cities hide in plain sight and contextualizes the generational scope of urban change.

In 1966, Ruscha published the first and only official installment in his Sunset Strip project, an enigmatic book called Every Building on the Sunset Strip. The book consists of a single accordion page which unfurls 25 feet to reveal a panorama spanning one and a half miles of street frontage on both sides of Sunset Boulevard. The book is simultaneously a parody of Robert Frank’s road trip photography and a mesmerizing work of postmodern realism. Every Building is a landmark depiction of American space: the Sunset Strip, with all of its star-studded hangouts, Hollywood billboards, and rough around the edges allure. Ruscha took to his project assiduously, manually stitching each photo together, labeling side streets and alleys along the way, leaving no piece of land out of the image.15

“Temporal streetscapes are an ingenious tool for depicting the shape of our built environment as a continuous negotiation between cultural preservation and progress.”

Aside from its humorous presentation, Every Building is an achievement in conceptual art that displays an urban environment through consistent, transparent editorial choices. Ruscha photographed a discrete stretch of roadway with such careful consistency that he eventually mechanized the process for reproduction on an industrial scale. Every Building makes an artistic advance by limiting the impact of the artist’s hand in order to represent the world with as few modifications as possible.

Ruscha’s 1966 project was the seed for a generational attempt to document changes in the built environment. After publishing Every Building, he kept the project going, rephotographing Sunset Boulevard for the next forty years.16 The project now includes twelve incarnations of Every Building, each one displaying the subtlest and most dramatic changes alike that occurred along the street in the time elapsed.

By recapturing Every Building, Ruscha turned his original project from a onetime conceptual achievement into a temporal streetscape whose significance gained complexity with each iteration. Rusca’s sequential panoramas

35 PANORAMA 2024

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE?

visually accelerate the pace of urban change and allow viewers to see the city evolve before their eyes.

Stitching together Ruscha and Streetview

To illustrate the utility of Ruscha’s Sunset Strip project, I hoped to recreate one of the era’s iconic images of Los Angeles using Ruscha’s panoramas – Robert Frank’s photograph of a statue on the Sunset Strip, as included in his landmark 1958 book, The Americans The Americans was a tremendous influence for Ruscha, who modeled some of his own first photography projects on Frank’s, especially his 1963 Twentysix Gasoline Stations 17

To my initial dismay, the statue photographed by Frank had been removed by the time Ruscha could photograph it. However, its absence underscores the treasure trove hidden in Ruscha’s work. Ruscha didn’t have the chance to photograph the statue, but he photographed the widened boulevard and parking lots that remained in its absence.

The statue, it turns out, was moved just a few blocks away, to a park in front of Los Angeles Union Station. Google Streetview captured it many times up until 2019. However, the statue was missing in all following images from that location.

By setting out on a foolhardy project to capture the world, much as Ruscha did for the Sunset Strip, Google Streetview captures the often-overlooked social and political movements etched into our built environment. The statue in question was a likeness of Father Junipero Serra, the principal architect of Spain’s California mission system, which systematically repressed non-European cultures in the territory and converted native people to Catholicism. In June 2020, indigenous activists tied ropes around the statue’s neck and pulled it to the ground.18

Ruscha’s work exists in a nexus between conceptual art, historical documentation, and urbanism. Associating his work with Google Streetview allows for an optimistic approach towards navigating the optics of urban change. Collective distaste and distrust for change in the built environment is an essential force for keeping cities equitable and functional, yet the same impulses are often the greatest barriers to making more sustainable transportation systems, building denser housing, and beautifying communal spaces. Temporal streetscapes are an ingenious tool for depicting our built environment as a productive negotiation between cultural preservation and progress. Every city is the manifestation of a collection of an untold number of decisions that shape the dimensions, character, and orientation of space. Temporal streetscape allows us to see this cycle in action.

36

A PICTURE OF THE ENTIRE WORLD

Endnotes

1 Olanoff, Drew. “Inside Google Street View: From Larry Page’s Car To The Depths Of The Grand Canyon.” TechCrunch (blog), March 8, 2013. 2 Ibid.

3 Google Maps Street View. “Celebrate 15 Years of Exploring Your World on Street View.” Accessed December 9, 2023.

4 Shet, Vinay. “Go Back in Time with Street View.” Google, April 23, 2014.

5 Li, Xiaojiang, and Carlo Ratti. “Mapping the Spatial Distribution of Shade Provision of Street Trees in Boston Using Google Street View Panoramas.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 31 (April 1, 2018): 109–19.

6 Smith, Cara M., Joel D. Kaufman, and Stephen J. Mooney. “Google Street View Image Availability in the Bronx and San Diego, 2007–2020: Understanding Potential Biases in Virtual Audits of Urban Built Environments.” Health & Place 72 (November 1, 2021):

About the Author

Jonathan Zisk is a second-year Master of City Planning student concentrating in sustainable transportation and infrastructure planning. He comes to Penn with an English degree from Reed College in Portland Oregon. He believes that cities are remarkable spaces for sustainable and equitable life and wants Chestnut and Walnut Streets to be permanently closed to cars.

102701. 7 Berners-Lee, Ben. “The Semiotics of Digital Cartography at the Geoguessr Interface: A Practice-Oriented Case Study.” New Media & Society, March 31, 2023. 8 Ingraham, Allison L. Rowland and Chris. “How Google Street View Became An Art Form.” Fast Company, May 25, 2017. 9 Browning, Kellen. “Siberia or Japan? Expert Google Maps Players Can Tell at a Glimpse.” The New York Times, July 7, 2022, sec. Business. 10 Condon, Ali. “Man Who Can Pinpoint Exact Locations from Tiny Details in Photos Explains How He Does It.” UNILAD, April 26, 2023. 11 “Plonk It,” Plonk It, accessed November 12, 2023, https://www.plonkit.net. 12 Kusahara, Machiko. “The Panorama in Meiji Japan: Horizontal and Vertical Perspectives.” Early Popular Visual Culture 18, no. 4 (October 1, 2020): 400–421. 13 Gleason’s Pictorial. Gleason. Frederick, 1852. 14 “Sunset Over Sunset.” https://www.sunsetoversunset.org. 15 Baca, Miguel de. “On Ed Ruscha’s Books, Los Angeles, and Peripatetic Flow.” Art in Print 9, no. 2 (2019): 46–50. 16 Sunset Over Sunset. 17 Wolf, Sylvia, Ed Ruscha and Photography. First edition. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2004. 18 Miranda, Carolina. “At Los Angeles Toppling of Junipero Serra Statue, Activists Want Full History Told.” Los Angeles Times, June 21, 2020.

FUTURE? 37

WHAT’S IN A

PANORAMA 2024

In Love

with the Details

Anecdotes on memory and an argument for beauty as a right

photos and words by Brianna Belo

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE?

I’ve noticed I’m mesmerized by the sidewalk on the corner of 34th & Market

in the same way that I’m enthralled by the long walkways in the Gardens of Versailles or the streetscapes in Paris.

It’s the detail that I find incredibly charming.

39

2024

Philadelphia, PA (left) and Versailles, FR (right)

PANORAMA

When moving back to Philadelphia from Paris I lived in a haze for the first 3 months of my return.

The fog began to lift for me only when I made my first visit to my neighborhood’s coffee shop.

I vividly remember walking into Two Sisters Coffee. Upon stepping inside I was greeted by the warm scent of baked spices—cinnamon, nutmeg and cardamom. My eyes rested on freshly baked sourdough bread and a lingering scent of roasted coffee stirred my consciousness.

I was instantly transported back to late mornings at French cafes and the daily strolls on which I was greeted with enticing smells wafting from patisseries.

In August of 2022 I moved to Paris to attempt living nomadically. I decided to make the City of Light my first stop. I chose Paris to be closer to my sister, but I had an additional semi-conscious motive to this move as well. After living in DC for nearly 8 years I was ready for something different, but I wasn’t sure what. Feeling restless from the confinement of COVID and heavy from the work of BLM, I was searching for a life that felt lighter—even if just for a little while. Brittany, my twin sister, had been living in Paris for 3 years at this point, steadily building her career in styling and editorial direction.

Paris, FR

Paris, FR

40 IN LOVE WITH THE DETAILS

The twin cities

Philadelphia and Paris have long held an interconnected relationship with one another. In some spaces Philadelphia is known as one of Paris’ sister cities, and Michelin’s “Le Guide Vert” has even crowned Philly the “Frenchest” city in America (the same guide asserts Philadelphia is a “perfect compromise between American excess and European spirit”). However, this title is not a recent accomplishment but rather a culmination of shared ideologies that have shaped the character of both nations.1 Following Independence in 1776, French revolutionaries remained in Philadelphia—motivated by idealism—to assist in the establishment of the nascent United States. 2 Beyond shared, foundational ideologies, French architecture and art transformed Philadelphia’s popular cultural and urban landscape, leaving an indelible imprint on our city. Many of Philadelphia’s anchoring monuments—City Hall, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Parkway, The Benjamin Franklin Bridge, and even the Philadelphia Zoo were designed by French architects or native Philadelphians trained in some form at Paris’ École des Beaux-Arts.

In hindsight, it comes as no surprise that Britt landed there permanently—as France’s fingerprints were left all over Philadelphia and inherently, our childhood.

Growing up in Philadelphia, I adored my hometown’s prestigious landmarks for their beauty and the memories I’d attached to them—fireworks on the Parkway, trips to the Zoo, and summer movie nights at the Delaware riverfront back lit by the Benjamin Franklin bridge are top of mind examples. I was even convinced I would live in the Art Museum someday. My sister and I developed a deep affection for our home, nurtured by the pride instilled in us through formative experiences throughout Philly.

Beyond Paris’ foundational connection to Philadelphia, the City of Light served as a haven for African Americans seeking respite from physical, intellectual, and spiritual violence of racism in the U.S. This relationship has long existed but further solidified when African American troops were commissioned to fight alongside French soldiers in both World Wars because they were excluded from serving on frontlines with white Americans. Fighting in company with the French forged bonds and invited cultural exchange between the two groups. African Americans were awarded medals for their bravery and invited into French homes, creating a lived experience that was nearly

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE?

41 PANORAMA 2024

unfathomable on U.S. soil at the time. It was also during this time that Black soldiers introduced their French comrades to Jazz, igniting France’s love of the genre and African American creativity.3 France garnered a reputation as a place where Black Americans could “just be” and prolific African American visionaries and activists began to seek refuge, find solace and inspiration in Paris’ embrace.4 Figures such as Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Beauford Delaney, Josephine Baker, W.E.B DuBois, Loïs Mailou Jones,

Paris, FR

“I needed Paris…It was a feast, a grand carnival of imagery, and immediately everything there seemed to offer sublimation to those inner desires that had for so long been hampered by racism back in America. For the first time in my life I was relaxing from tension and pressure.”

- Gordon Parks, Voices in the Mirror: An Autobiography

alongside notable Philadelphians like Henry Ossawa Tanner and Julian Able, were among those who selected the city to develop their craft and advance their ideologies. The contributions and philosophies of these individuals empowered African American expression and advocacy, particularly at a time when it faced suppression in the United States. Local historians and African-American expats alike celebrate Black culture’s ubiquity throughout the city. With an awareness of this context, Paris felt like the ideal place to slow my pace and make room for ease in my life.

On my walks to and from Britt’s apartment – 20 minutes each way—I’d slow my pace and marvel at the streets, stopping at the windows of patisseries and forgoing headphones in order to take in the honks of scooters, or the sounds of petit voices playing in the parks I passed by.

One morning we set out on a walk that became a 2 hour stroll through Montmartre. The streets were empty and our pace was leisurely. I savored the sense of wonder that I felt as I discovered this new place, lingering on corners and in corridors. We ended at my sister’s favorite café, Two Doors Coffee. When stepping inside, as the shop was lit with soft morning light, I was greeted with echoes of Cleo Sol’s “23” and an aroma of freshly ground espresso. This walk allowed me to reclaim a childlike moment with my sister.

42 IN LOVE WITH THE DETAILS

We were close growing up, our younger years full of long days of play and longer conversations about everything and nothing.

It was in Paris that for the first time, since childhood, I was able to experience what it meant to just be—to linger and mosey.

Savoring small details

Back in Philadelphia, Two Sisters led me to once again be mesmerized by the details of a place —exposed brick and steel beams boasted the building’s original architecture, and the space itself held a warm hum of chatter. The baristas were busy fulfilling orders while the cafe’s in-house baking staff were pulling pastries from a stone fire oven.

As I settled into my seat and continued to take in my surroundings, I fell into the same trance I’d felt during my travels when my eyes were drawn to the way a light hit a surface, a texture, or art hidden in plain sight. This space in my home city evoked the same sense of wonder and curiosity.

I recalled this first long walk with my sister in Paris, one of many walks where I inspected nearly every corner, sidewalk, and wall searching for new intricacies I’d never noticed before.

IN A FUTURE?

WHAT’S

43 PANORAMA 2024

44 IN LOVE WITH THE DETAILS

Philadelphia, PA

I’d call each outing “a little adventure” and take photos, savoring the small details of my surroundings. I loved my photo walks because they grounded me and put my nervous system at ease.

I continued the practice of photo walks when I moved back to Philadelphia.

Over time I found myself beginning to obsess over the beautiful intricacies of this city that I was born in—realizing my hometown had as much to offer as the streets of Paris when I looked closely.

Photo walks were quite sensory—they brought forward a slow, unraveling sense of relief—like kneading bread, sculpting clay or flowing through a yoga sequence. I could breathe deeper and connect more to the environment around me.

The sensations I’d felt on my photo walks often revisit at random moments when I walk around Philadelphia. A cool gust of air would trigger a memory and suddenly I’d feel that same sense of freedom I felt exploring autumnal Paris or Menorca. I liken these senses to cravings. In the same way that the smell of roasting herbs may evoke a taste for one of my mother’s staple recipes, or the light hitting red bricks on rowhomes makes me long for golden hours spent at French cafes watching the light cast shadows of building facades.

WHAT’S IN A FUTURE?

Paris, FR

45 PANORAMA 2024

Today, as a city of neighborhoods, it is difficult not to find yourself reflected in some facet of Philadelphia. Though not perfect, and often threatened, the city has somehow managed to maintain much of its deeply rooted character. Philadelphia is expressive, rebellious, resistant, and dynamic —it bucks at uniformity, perfection, and sterility, instead insisting that you come as you are, with no heirs and no agendas. Here, you can tap into identities you may have tucked away in less cosmopolitan spaces and invest in facets of yourself that might have been challenging to explore in less accessible cities.

As I reflect on Paris’ impact on me, I now do not find it surprising that Paris and Philadelphia are considered sister cities, and that the City of Light has a legacy of attracting people of color from the States to its streets.

Like Paris, Philadelphia often acts as a mirror for who you are, a challenger and catalyst, helping you embrace dormant factions of yourself.

In the same way that Philadelphia’s boastful architecture pays homage to its French influences, Philly’s whispers, snickers and nuances do the same—as if the dialogue between Paris and her kid sister have never stopped. Together, they point at you and ask you who you are. This time abroad revealed to me how different environments can uncover hidden facets of my personality. Searching for my environment’s intricacies helped me notice my own by deepening my connection to my innate curiosity and rekindling my admiration for creative expression in urban landscapes.

“[Philadelphia is] a very human city..with a strong human identity that you can see when walking or cycling in its neighborhoods.”

—Philippe Orian, Editor-In-Chief of the Michelin Green Guide5

Savoring these details was therapeutic. Photo walks allowed me to be more present, and became a key strategy in the rehabilitation of my mental health. I felt as though the built environment had loved notes dispersed for me to find.

Our brains process senses, emotions, and memories in tandem. For instance, smell is closely linked to memory storage and emotional recall. Therefore, landscapes and places can trigger memories and evoke values through their physical attributes. Even if memories are created elsewhere, landscapes can become vessels to revisit what is not immediately tangible. By paying attention to the sensory experiences provided by our surroundings,

46 IN LOVE WITH THE DETAILS

such as what we see, hear, smell, and feel, it can help us remember that we share common human experiences. Mindfulness in the natural world can serve as a way to connect with and understand one another better.

This single coffee shop spurred an internal dialogue I am still mulling over to this day:

Similar to music, food, and poetry, our physical landscapes communicate to the soul and to the mind.

Physical landscapes have the power to hold memory, ease or even disrupt our sense of being.

For this reason, in the same way that I am fascinated by the sidewalk on 34th street, I find myself fascinated by the language of our built environment.

Beauty is a right

These anecdotes remind me that beauty is a right, and beauty is justice.

Architecture and design are often posed as luxuries—indirectly communicating that beauty is only for those who can afford it.

My love for urbanism is not attributed to Paris or Philadelphia alone. I will not over-romanticize the legacies of these cities. France and other imperial nations have colonial histories that I hope reparative planning will address, while Philadelphia has enduring histories of divesting and policing communities of color.

But before Paris I was not conscious of the hypervisibility and weight I felt as a Black woman in America.

The weight can feel heavy on your shoulders—much of the time.

It is difficult to admit that before Paris, I didn’t know what many Black Americans meant when they said they felt like they couldn’t breathe.

It wasn’t until I felt what it was like to expand, breathe and stretch out—free of weight, that I understood what it meant to breathe without burden attached.

I argue that for me (as for many)—the city’s emphasis on beauty awakened a demand for beauty that already existed inside of me. The same way it provided an environment that pulled out the prolific work and sentiments that were gestating in the Josephine Bakers and James Baldwins that have paved the way for my generation.

Black people saw ourselves reflected in the urban, social, and cultural fabric of the City of Light—and time spent there has imprinted a call to pull that forth, to continue creating and revitalizing, leaving our mark on tangible and intangible landscapes.

A FUTURE?

WHAT’S IN

47

PANORAMA 2024

48 IN LOVE WITH THE DETAILS

Paris, FR (top and bottom right) and Versailles, FR (bottom left)

It is my love for Philadelphia that calls me to critique it. Growing up in this city I noticed disparities across neighborhoods and counties before I understood what they were. I have always remembered how that made me feel.

Not everyone in is provided the same opportunities to sit in a sense of awe and wonder, to dream, and to soak in the beauty of the environment around them.

Those living in neighborhoods heavily impacted by inequity, discrimination, and structural violence are often told by their environments that they are not enough, and that they must strive, adapt and assimilate to achieve a better quality of life.

Some of us have chosen to leave the U.S—while some have come back—revived and willing to reshape what tried to assimilate or contort us. There is no one way to heal from the generational and internal ruptures caused by systemic racism.

It is my love for Philadelphia that calls me to critique it.

As a Black woman I am still finding my way and recovering my voice, and as a planner and designer I am constantly looking for the ways in which my identity is both reflected in and shaped by the environment. So far, I know that I aspire to help craft external landscapes that mirror our internal worlds.

As a result, I continue to ask myself questions like “what prevents us from designing as if beauty is a universal right?”, “how are we using coded language to police public life in the way we design?”, “what uncomfortable realities are we overlooking in this field?”, “how can we transform the internal (individuals) and external (communities—physically and socially) environment at the same time?”, and “in what ways can we promote healing in design processes and outcomes?” I am insistent on continuously evaluating my biases in this field, and the impact of this work on the human psyche. I care deeply about the subtle and obvious ways in which we are creating opportunities for shared experiences that leave emotional imprints and ease in our collective memory.

I look to human-centered design principles, joy, liberation and the frameworks of anti-racism, restorative justice, radical imagination, to design a

IN A FUTURE?

WHAT’S

49 PANORAMA 2024

world that reminds community members they are worthy of all they dream of, and that resources and peace need not be withheld from them.

Space for deep, expansive breaths was the propellant of my predecessors.

I believe we need more architects, planners and designers who are willing to play with the built environment, and leave love notes that remind people that their humanity is welcome.

So finally, I am reminded that I want to be a designer who makes sidewalks sparkle, because joy is an act of defiance and resistance.

50 IN LOVE WITH THE DETAILS

Paris, FR

Endnotes

About the Author

Brianna (Bri) Belo (she/her) is a first year Master of City and Regional Planning Candidate in the Housing, Community and Economic Development concentration and is pursuing a certificate in Urban Design. Bri is a native Philadelphian who is passionate about understanding the ways in which the built environment impacts the human psyche and how it can be used as a tool for healing, reconciliation and social cohesion.

IN A FUTURE?

WHAT’S

3 Virok and Cooper

Chernick,

in

Obscura, August 24, 2020.

Prihar, Asha.

at WHYY, May 10,

1 Virok, Christina, and Lauren Cooper. “France and the French.” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, March 17, 2022. 2 Haas, Kimberly. “Je t’aime, Jawn Française! New Book Explores Philly’s Inner Francophile.” Hidden City Philadelphia, July 16, 2021.

4

Karen. “The Hidden Histories of Black Americans

Paris.” Atlas

5

“Michelin Is Coming to Town with Its First-Ever Philadelphia Tourism Guide.” Billy Penn

2023.

51 PANORAMA 2024

Tre Ambroise

Bailey Bradford

Shefali Gupta

Katie Hanford

Sidney Kuesters

Jiahang Li

Alec Pompeo

Kathleen Scopis

Samantha Shasanya

Yang Yang

STUDIO A Legacy Planning Framework DELPHIA 2026

PHILA-

WHAT’S

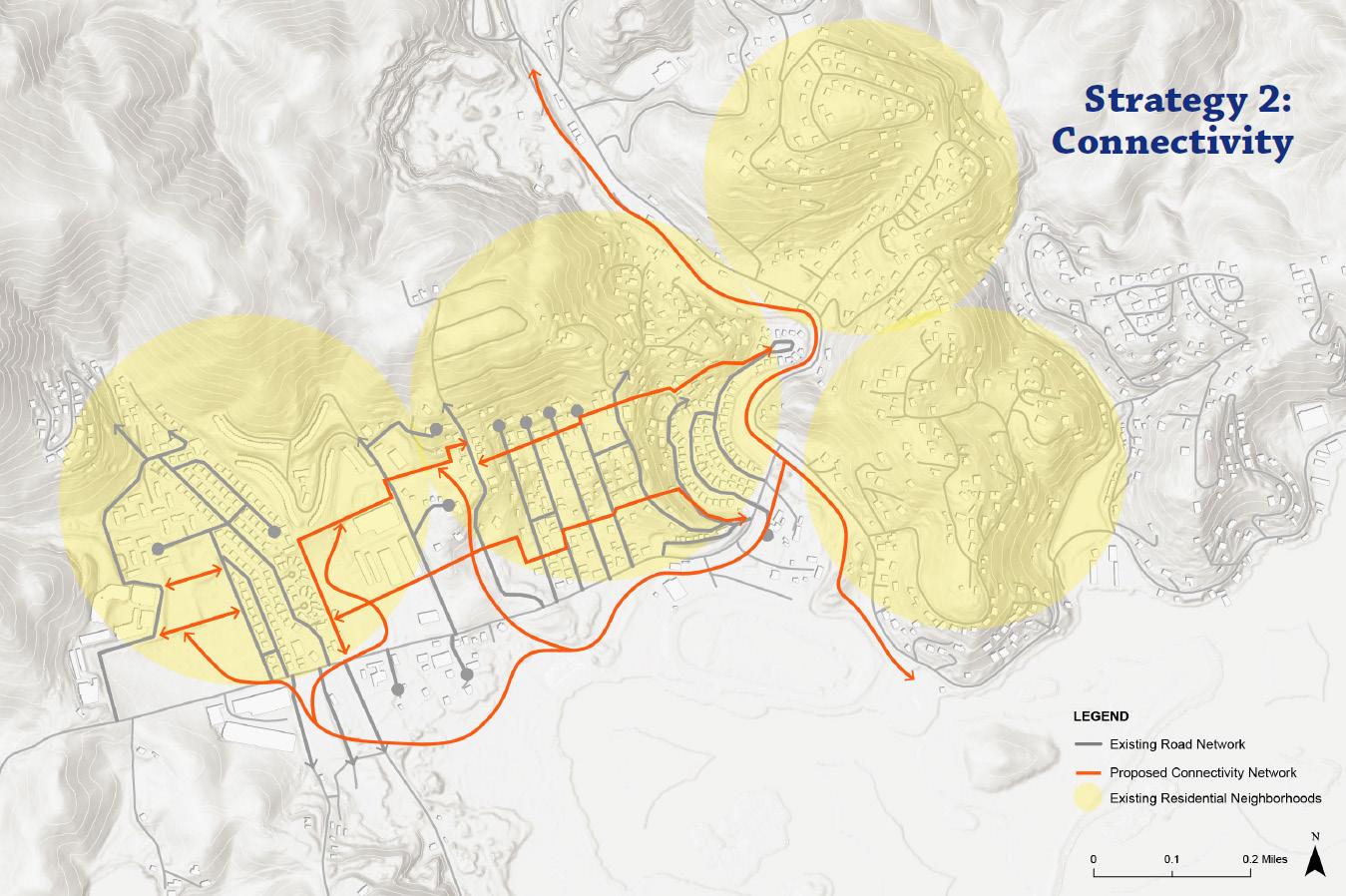

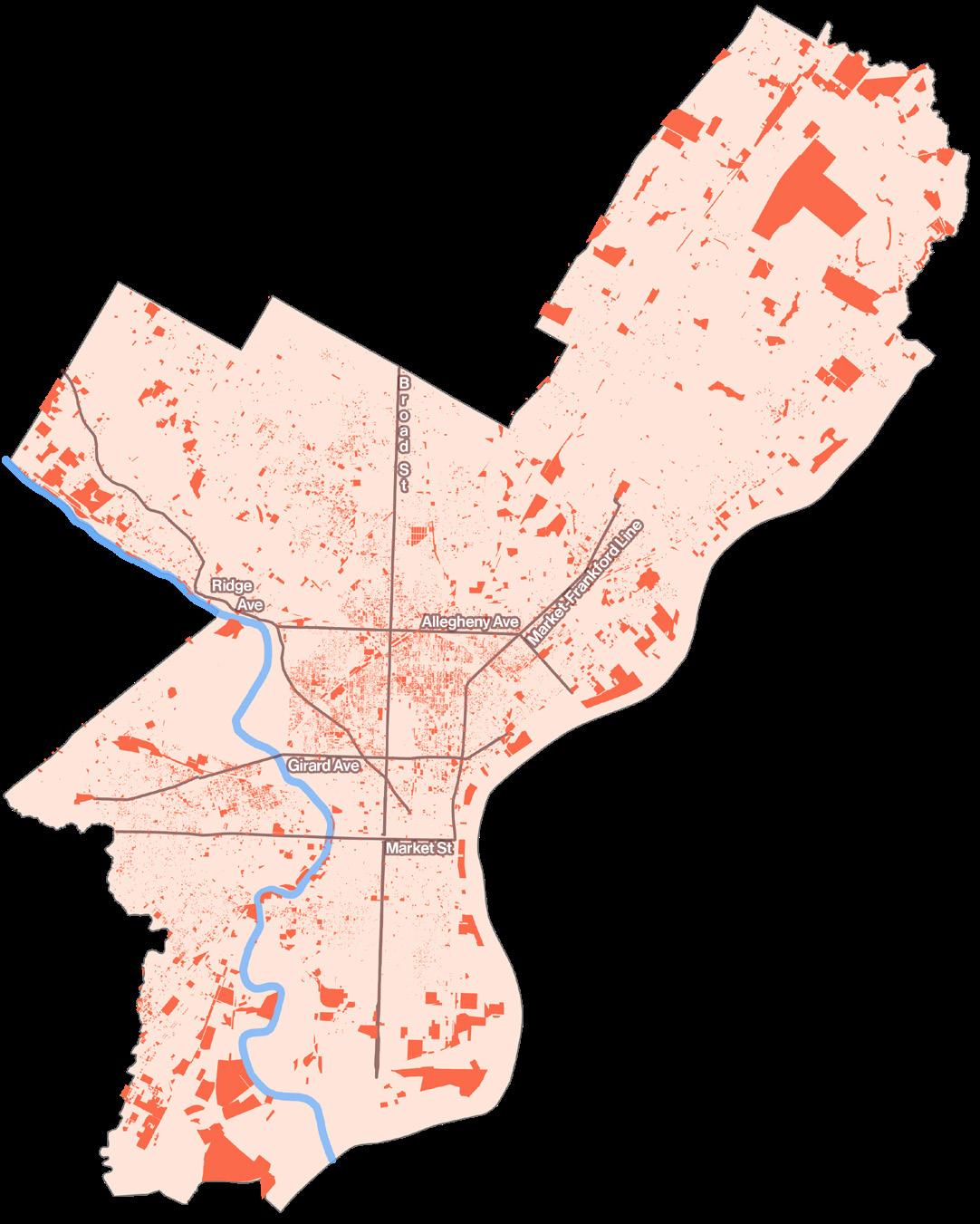

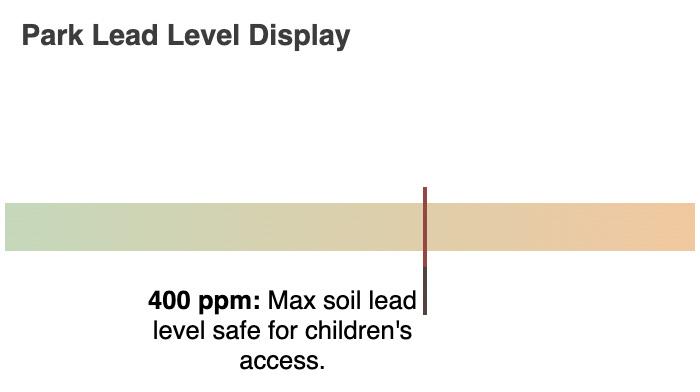

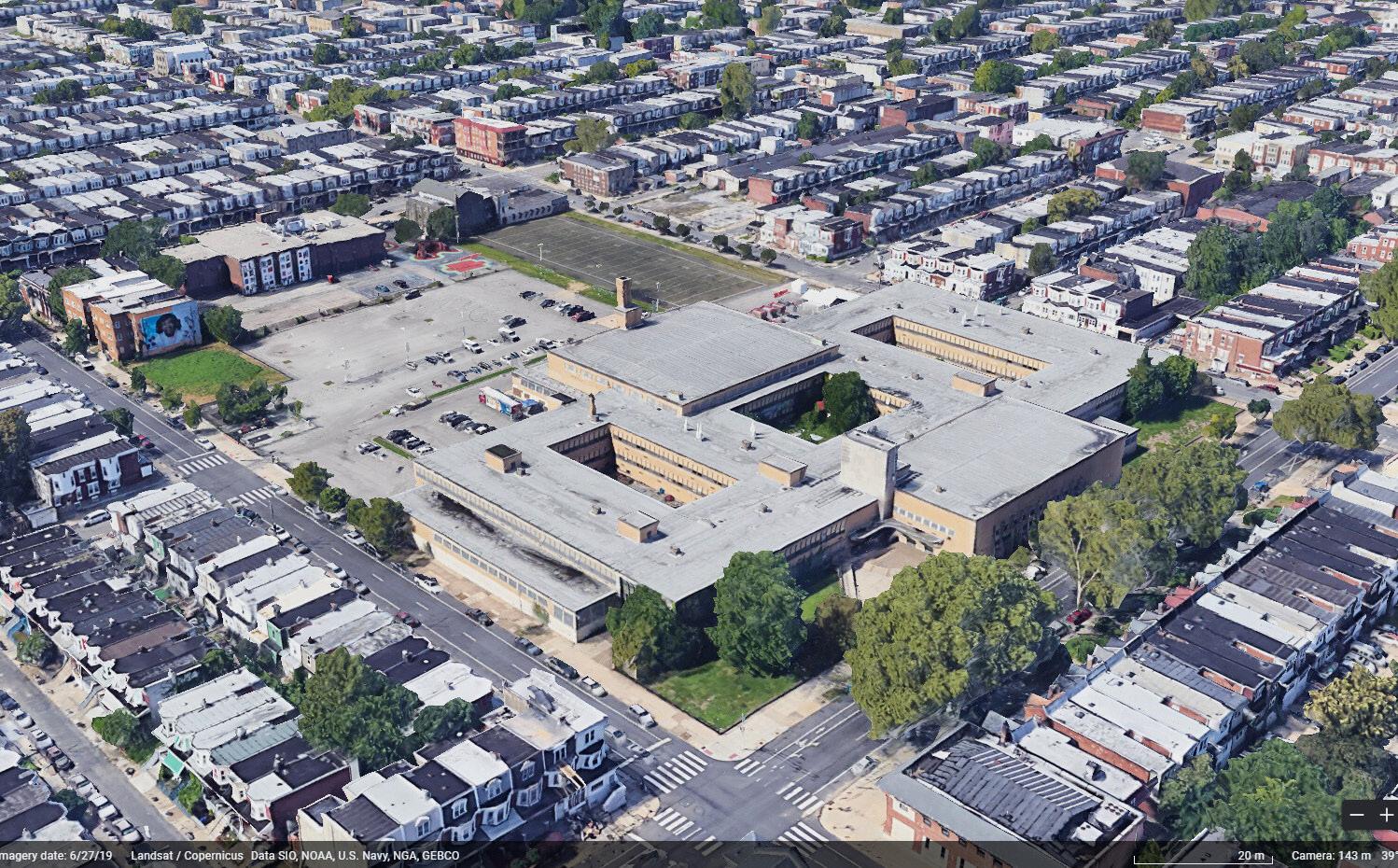

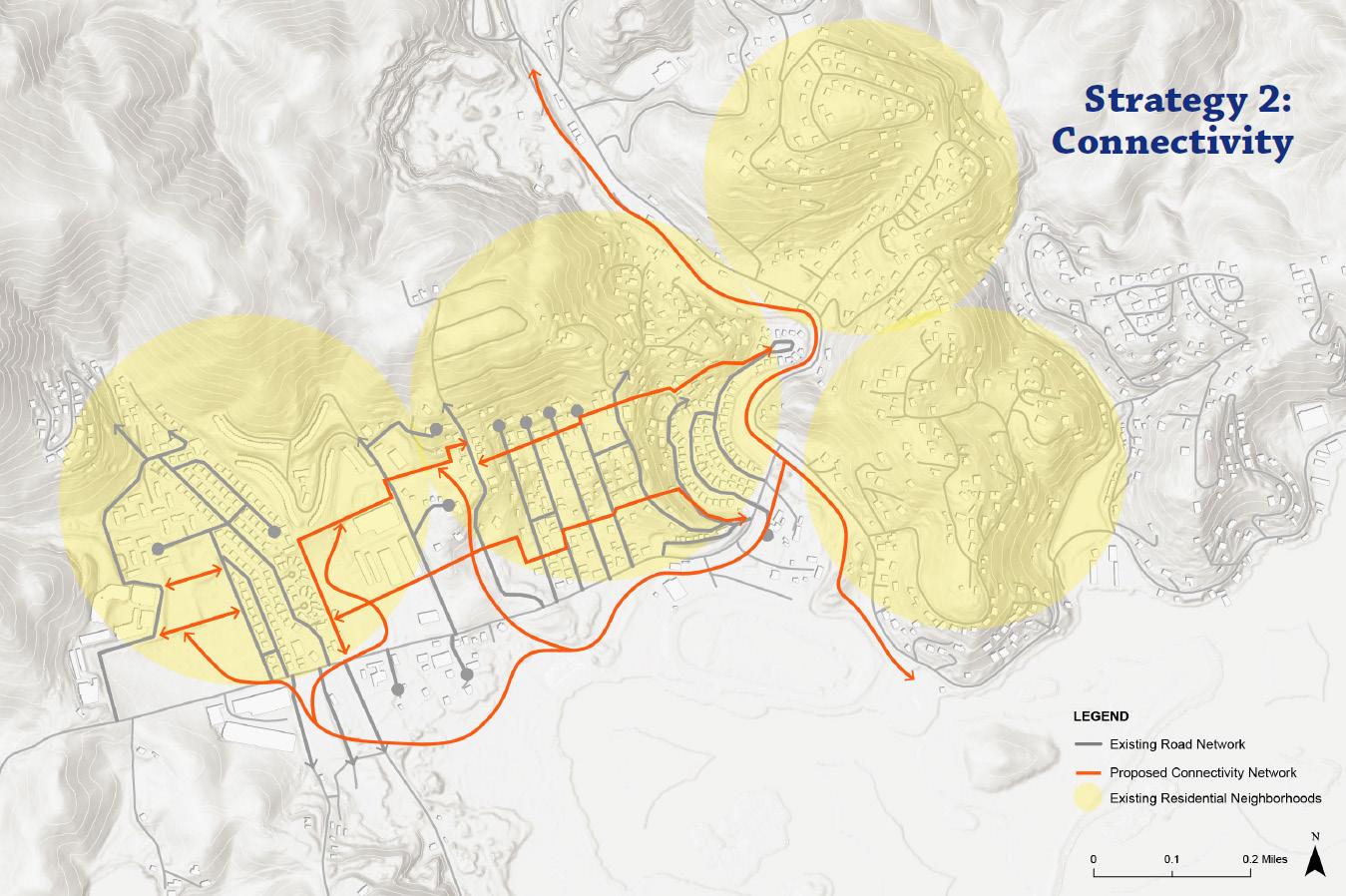

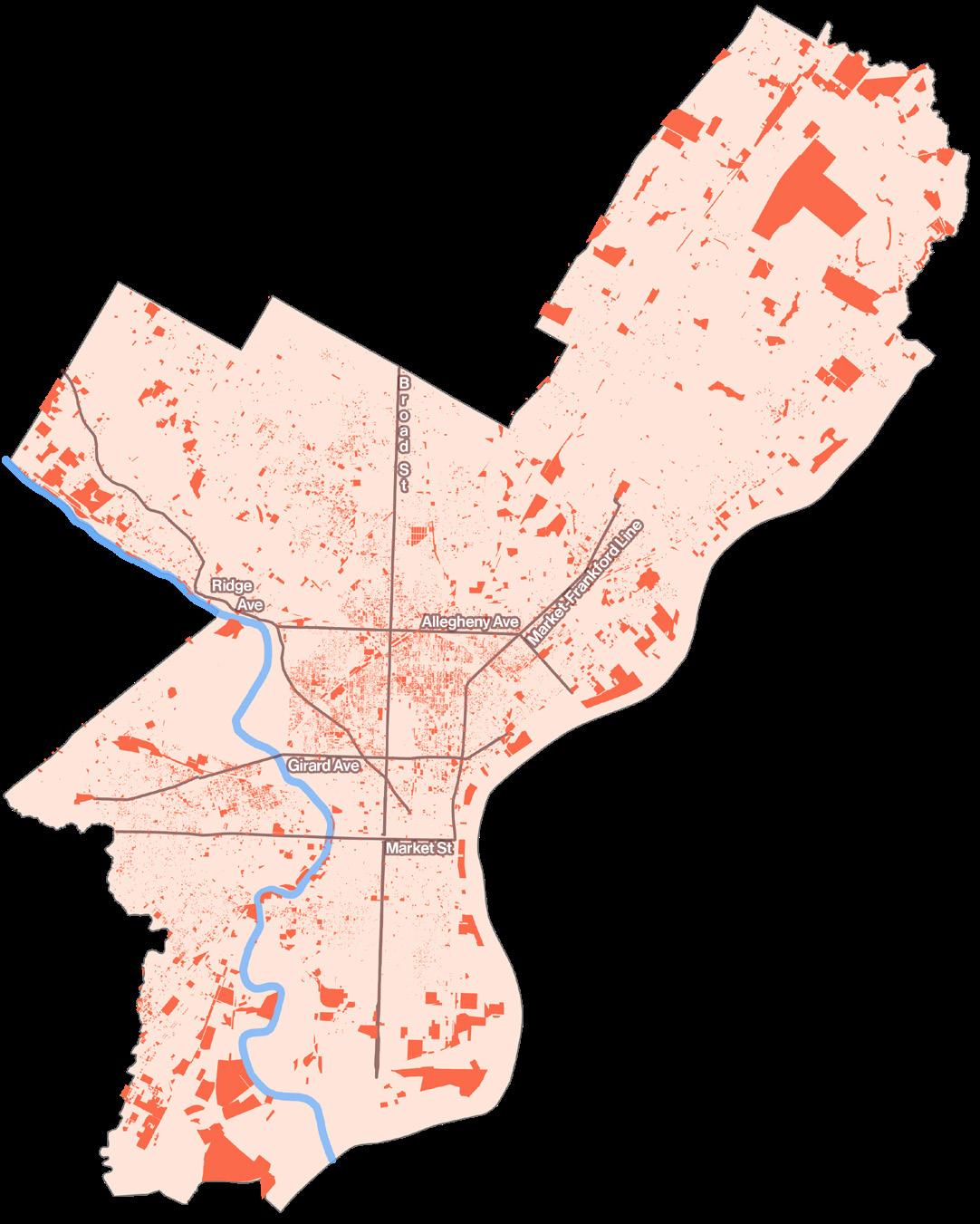

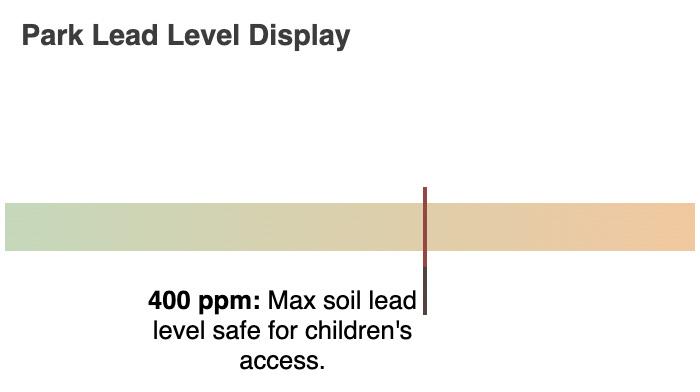

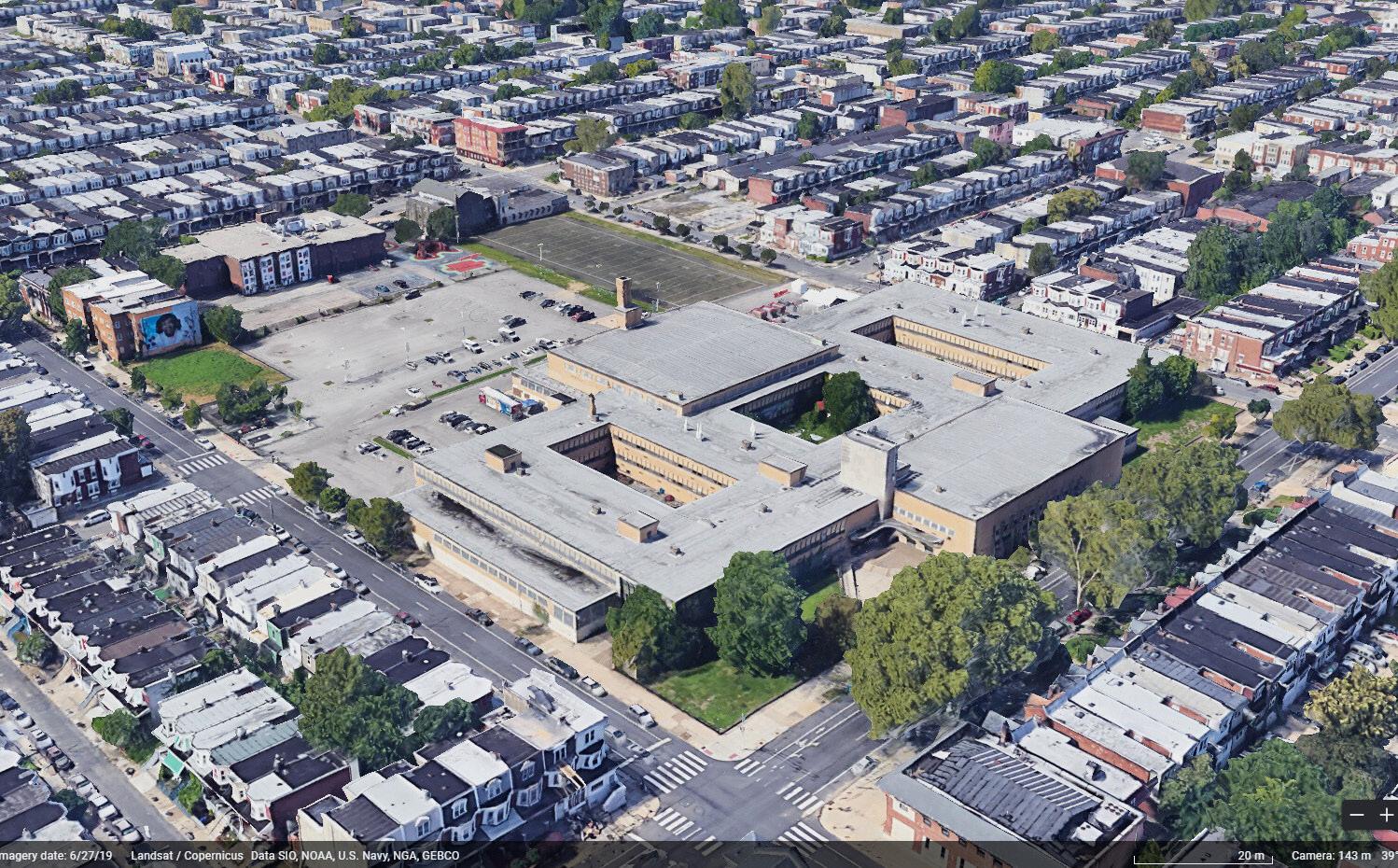

In the summer of 2026, Philadelphia will attract visitors from around the world for the FIFA World Cup, the nation’s semiquincentential, and the MLB All-Star Game—how can the city leverage the mega-events of 2026 to make an equitable, long-term impact for Philadelphians?

53 PANORAMA 2024

IN A FUTURE?

250 Years in the Making

As the city where the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, it’s only natural that the nation’s birthdays should be celebrated in Philadelphia. Every 50 years, the city hosts a major commemoration for the occasion, with each event leaving a major mark on the city. The 1876 Centennial Exposition brought us Fairmount Park as well as the 1776 Bicentennial iconic imagery that would come to define the Sixer’s brand.