ISSUE NO. 8_15 dollars

FASHIONING A COMMUNITY.

+ FEATURING DANIELA UPSHAW, BAMCO, RICKETT’S INDIGO, ALLISON FORD, MATTY BENNETT, CURT ATON AND MORE

LET US MAKE YOU SOMETHING SPECIAL Cocktails Reinterpreted at Plat 99

The Art of the Cocktail. Art inspired us to think about hotels differently. The Alexander’s Plat 99 will inspire you to do the same about hotel bars. Designed by the award-winning artist Jorge Pardo, Plat 99 is a vibrant mixology lounge featuring small plates and artisanal cocktails made with fresh, local ingredients. Bright flavors and colors combine with incredible sights and sounds to elevate a night out with friends into a true work of art. thealexander.com 333 South Delaware Street Indianapolis, IN 46204 (317) 624-8200

SEREIN 16 DIAMOND TWO-TONE ROSE GOLD, COCOA DIAMOND DIAL ON TWO-TONE ROSE GOLD 7-LINK

146Th STREET AND MERIDIAN, CARMEL IN

146th Street and Meridian Carmel, IN WWW.MOyERfINEjEWELERS.COM www.moyerfinejewelers.com 317-844-9003 317-844-9003

SEREIN 16 DIAMOND TWO-TONE ROSE GOLD, COCOA DIAMOND DIAL ON TWO-TONE ROSE GOLD 7-LINK

146Th STREET AND MERIDIAN, CARMEL IN WWW.MOyERfINEjEWELERS.COM 317-844-9003

DESIGN & INSTALLATION SERVICES | DRAPERY TREATMENTS | BLINDS | SHUTTERS DECORATIVE PILLOWS | BEDDING | SHOWER CURTAINS | WALL PANELS | HEADBOARDS All products are fabricated by veteran seamstresses in our on-site workroom. KITCHENS BY DESIGN | KBDHOME | CUSTOM DRAPERY | 1530 E. 86TH STREET • INDIANAPOLIS, IN 46240 | 317-815-8880 | MYKBDHOME.COM

sculpture objects functional art and design November 6–8 Opening Night, November 5 Navy Pier

Ken Akaji, Ippodo Gallery

sofaexpo.com

EDITOR’S LETTER

TIME TO GET OUR HANDS DIRTY TO MY GREAT EXCITEMENT, IN FEBRUARY, THE CITY OF INDIANAPOLIS decided to invest in the creation of a makerspace inside the gigantic Circle City Industrial Complex located in the Mass Ave/ Brookside corridor. The grant was part of a broader initiative to stimulate and support small scale manufacturing job creation in Indianapolis. Since then it’s been a non-stop medley of meetings with city planners, architects, makers, consultants, sponsors and donors. Bringing Ruckus - the makerspace - online is a huge undertaking, and I am deeply grateful that so many entities and individuals have offered their support to Pattern and our partner, Riley Area Development Corporation, to help make it happen. AS IF THAT ISN’T ENOUGH, WHEN THE ONE YEAR ANNIVERSARY OF PATTERN STORE ROLLED AROUND, instead of throwing a party, we decided to rework the entire concept, and re-launch as Pattern Workshop—a combination of micro-makerspace, showroom and event space. We’re still on Mass ave in the Trailside building, just in a different space, and it looks amazing! The revised concept is what I had originally envisioned when the opportunity to have a storefront presented itself - I think taking makers out of their basements and spare bedrooms and putting them front and center on a lively, downtown street is one of the best ways that we can continue to educate our community about the Maker Movement, and why it matters. As this issue is going to print, Christian, Jerry, Chelsea, Eric and Rachel, are all busy moving into the space and getting ready to take their businesses to the next level. If you haven’t had a chance to stop by and meet them yet, please do so! AND SO PATTERN’S WORK TO PUT THE MAKERS OF OUR FINE CITY ON THE NATIONAL AND INTERNAtional stage continues. We’ve taken many great strides in the last five years. Tangible support from Indy’s civic and business leaders means that there is a growing understanding of the importance of small-scale manufacturing for our city’s economic, and yes, cultural future, but we’ve got a long way to go yet. HOW CAN YOU HELP? FOR STARTERS GET TO KNOW THE LOCAL MAKERS - THERE ARE QUITE A FEW OF THEM—AND BE SURE to support them by purchasing their goods. Also? Tell your friends! And if it’s been a while since you last visited downtown Indianapolis, I invite you to come and see how much growing up our little city has done in the last few years—I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised! FINALLY, I HOPE THAT THE CURRENT ISSUE NOT ONLY OPENS YOUR EYES TO ALL THE DIVERSE TALent and cool stuff happening in Indianapolis, but perhaps also inspires you to pick up some tools, and get back to exploring a well-loved hobby or creative outlet. Making stuff is where it’s at! PS. As our publication matures, we’ve decided to venture more purposefully outside of Indy’s borders to share our story with the rest of the world, face to face. So starting with the current issue we’ll be traveling to different parts of the country, making new friends, visiting old ones, and bringing back great Hoosier expat stories and fabulous fashion editorials. This issue, we went to NYC, and had an amazing time! Next stop? LA!

POLINA OSHEROV_EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

PHOTO ©BENJAMIN BLEVINS

6

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

COMING SPRING 2016 | INDYRUCKUS.COM

FASHIONING A COMMUNITY.

PUBLIC RELATIONS Keri Kirschner

AD SALES

ads@patternindy.com Account Director Laura Walters Account Director Jordan Updike

DISTRIBUTION

Distributed worldwide by Publishers Distribution Group, Inc. pdgmags.com Printed by Fineline Printing, Indianapolis, IN USA PATTERN Magazine ISSN 2326-6449 is published by PATTERN

EVENTS

Event Director Laura Walters events@patternindy.com Event Coordinators Abbi Johnson Amanda Meyer Volunteer Coordinator Esther Boston

ONLINE

Senior Web Developer Peter Densborn Web Developer Tony Ledford Content Manager Eric Rees content@patternindy.com

SHOWROOM

871 Massachusetts Ave Indianapolis, IN 46204 Hours: 12-5p, Thr-Sat

VIDEO

Nickerson Films

BOARD OF DIRECTORS Maria Dickman Kenan Farrell Daniel Incandela Kyle Lacy Craig McCormick Polina Osherov Sherron Rogers Eric Strickland Barry Wormser Tamara Zahn

HOW TO REACH PATTERN

Events: For the latest on Pattern events, sign up for updates via meetup.com/pattern

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Visit patternindy.com/subscribe Back issues, permissions, reprints info@patternindy.com Advertising inquiries ads@patternindy.com

EDITORIAL

Editor & Creative Director Polina Osherov Design Director Kathy Davis Managing Editor Eric Rees Senior Designer Lindsay Hadley Senior Copy Editor Mary G. Barr Editors-at-Large Benjamin & Janneane Blevins & Maria Dickman Staff Photographer Esther Boston

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Kevin Aranibar Al Bracken Wil Foster Shaun Frederickson Hadley “Tad” Fruits Elese Keturah Polina Osherov Greg Perez Stephen Simonetto Christopher Whonsetler

ILLUSTRATORS

Jon McClure Aaron Scamihorn

WRITERS

Mary G. Barr Maria Dickman Amanda Dorman Catherine Fritsch Crystal Hammon Dylan Hodges Denver Hutt Abbi Johnson Richard McCoy Ashley Minyard NaShara Mitchell Kate Newman Gabrielle Poshadlo Austin Radcliffe Sam Stall Madie Szrom Danielle Waggoner Laura Walters

DESIGNERS

Doug Eaddy Andy Fry Lindsay Hadley Lars Lawson Amy McAdams-Gonzales Jon McClure Stacey McClure Katie Snider Cody Thompson

DESIGN INTERN Abigail Godwin

PATTERN WORKSHOP & EDITORIAL OFFICES PATTERN 871 Massachusetts Ave Indianapolis, IN 46204 By appointment only

A SPECIAL THANKS TO

Riley Area Development Corporation, Sun King Brewing, IndyChamber, PRINTtEXT, SpeakEasy, KLF Legal, Central Indiana Community Foundation, Indianapolis Downtown Inc, LISC, Moyer Fine Jewelers, and Horizon Bank 8

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

CHALLENGER G U S TAV E E F R O Y M S O N ENTREPRENEUR

FEARLESS BUSINESSMAN. FIGHTER OF BIGOTRY. FOREFATHER OF PHILANTHROPY IN CENTRAL INDIANA.

THE COMMUNITY WE’VE BECOME STARTED TAKING SHAPE A CENTURY AGO. THE COMMUNITY WE’LL BE IN 100 YEARS

STARTS WITH YOU.

Share your vision for the future of Central Indiana at CICF.org/BeIN.

CONTENTS PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8 patternindy.com

TEXT EDITOR’S LETTER, 6 CONTRIBUTORS, 12 TRUE BLUE, 24 RALEIGH DENIM, 30 BAMCO Q&A, 32 MAKING SPACE FOR MAKERS, 34 HIDE BOUND, 46 MADE IN INDIANA, 51 Danisha Brown Jerry Lee Atwood Ian Oehler Christopher Stuart Allison Ford Matthew Osborn Matty Bennett Brian McCutcheon Indy_Droids Curt Aton Sister Karen BECK JONES Q&A, 68 DANIELA UPSHAW, 74 THE MAKER’S PROCESS, 78 INDxNYC, 104 CRIMSON TATE Q&A, 128 OP-ED, 160

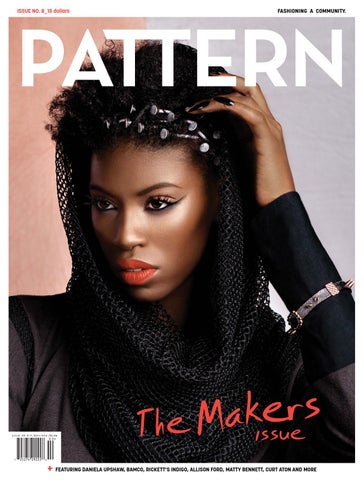

IMAGES CONSTRUCTED, 14 HARD WEAR, 41 THE MAKER’S MAP, 64 RED HARING, 70 STUFF ARRANGED PRECISELY , 76 BEAUTY BREAKFAST, 80 LOVELY BONES, 84 SKYLINES, 94 CONCRETE, 110 IN CONFIDENTIAL, 121 INFURTUATION, 130 QUEEN NAPOLEON, 138 DAY GLOW, 144 A HAUNTING FALL, 152 ON THE COVER Ebony, LModelz Model Management Photography by Polina Osherov Art Direction by Polina Osherov & DaNisha Greene Style by DaNisha Greene Makeup by Kathy Moberly Hair by Philip Salmon Manicurist Tenesa Burnett Photography assistant: Esther Boston Wardrobe assistant: Candace Bullock Retouch by Wendy Towle Wardrobe: Hooded mesh sweater, Arreic Black romper, Arreic

10

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

ON THIS PAGE Dress, Vivien Jackson by Mariah Crop Top, Arreic Accessories, Cheeky Couture

CONTRIBUTORS

MAKERS OF ANOTHER KIND WORD SMITHS, DOCUMENTARIANS AND LAYOUT NINJAS ILLUSTRATIONS BY AARON SCAMIHORN AL BRACKEN, PHOTOGRAPHER

DENVER HUTT, WRITER

DOUG EADDY, DESIGNER

AUSTIN RADCLIFFE, ARTIST AND CURATOR

INFURTUATION, PAGE 130

MATTY BENNETT, PAGE 59

QUEEN NAPOLEON, PAGE 138

STUFF ARRANGED PRECISELY, PAGE 76

albrackenphotography.com

Indianapolis native Al Bracken has always been drawn to the arts in its various forms. He was Introduced to the medium of photography by a college roommate assisting a local NBA and NFL sports photographer, but discovered that he was more drawn to fashion editorial and advertising imagery. He built a relationship with LModelz Model Management where he tested with all the new talent. After a year of portfolio building, he packed two suitcases and boarded a New York City bound Greyhound coach and freelanced in the city for various modeling agencies, as well as doing actor headshots, and cookbooks for clothing startups. Now back in Indy, Al is in preparations to attend a one-year portfolio school in Chicago this fall for art direction. His goal is to be an art director living in New York City and working with luxury and commercial fashion brands. If you could spend your whole life making something, what would it be? Building a large house or public museum with various rooms, antechambers, and secret passageways with each space having it’s own unique charm or character. Think of Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory.

ASHLEY MINYARD, WRITER @ashleyminyard_

INDXNYC, PAGE 104 Ashley Minyard is a recent Indiana University grad who has just made the big move to New York City. She is looking to start her career in magazines, a passion that Pattern has helped inspire. She loves all things creative—art, fashion, music, and food—and seeing Indiana’s arts community grow and develop makes her proud to be a Hoosier. If you could spend your whole life making something, what would it be? If I could make a living by “making” I would make magazines!

12

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

@denverallison

A born Southern Californian but Hoosier at Heart, Denver Hutt attended Indiana University—Bloomington where she earned degrees in political science and criminal justice. Following her graduation in 2009, Hutt moved to Indianapolis where she was named Executive Director of Central Indiana’s first collaborative work space, The Speak Easy. Under Hutt’s leadership, The Speak Easy’s adopted its vision to “cultivate an entrepreneurial community in which its members create, collaborate, and learn.” This echoes Hutt’s driving passion to connect community partners to produce new relationships and advance economic opportunity across Indianapolis. Hutt’s efforts have led to her being recognized as an Indianapolis Business Journal “Forty Under 40” honoree, a member of the Stanley K. Lacey Series class XXXIX, an Indy Star Woman to Know and a Plan2020 CityCorps Fellow.

NASHARA MITCHELL, WRITER @Nashsaramitchell

OP-ED, PAGE 160 NaShara Mitchell is a SUCCESS advocate, strategist, speaker, educator, entrepreneur, and business owner (#SASSEE B) reframing gaps to opportunities in education, business and life for women, creatives, and the underrepresented. With 14 years in higher education administration and business ownership, she currently serves as assistant dean of academic affairs and student development for the Indiana University Graduate School. As a Plan C professional, she is also the owner of Studio B Creative Exchange, an unconventional co-working accelerator and event space, the Design Bank-a maker space with Impact in 3D and Ready to Blush—a beauty and wellness concierge. If you could spend your whole life making something, what would it be? Make ideas happen for ALL.

blazedesignstudio.com

Doug Eaddy is a new design recruit to the Pattern Magazine Army. Hailing from a small town in Scranton, South Carolina, Doug brings his unique perspective in design by incorporating his architectural background to his new found love: art direction and graphic design. If Doug not seen indulging in the southern tradition of BBQ and football, he is found designing and exercising his entrepreneurial skills by focusing on his own studio Blaze Design Studio. His dedication and perseverance awarded him the opportunity to have his work featured on prominent websites “Abduzeedo” and “Packaging of the World.” and have designs selected by Grammy Award Nominee recording artist Kendrick Lamar and renowned recording artist Wale. He’s even happier that he is able to fulfill his desire by helping people dream different and dream bigger. That’s why he lives by his motto: Live Life. Takes Risks. Have No Regrets. If you could spend your whole life making something, what would it be? Designing affordable homes/communities for lower income families, veterans and the elderly. I feel that just because you’re poor, older or a veteran you shouldn’t be deprived from being a able to have a stress-free and safe environment. And with the world changing, we all need to do a better job of giving individuals a better shot at life and it starts at home.

AARON SCAMIHORN ILLUSTRATOR AND SCREEN PRINTER, RONLEWHORN INDUSTRIES ronlewhorn.com

CONTRIBUTORS, PAGE 13 He is an illustrator and screen printer living in Indianapolis and operating his business under the name Ronlewhorn Industries. He produces hand-screenprinted artwork such as gig posters for bands like Cake, Taking Back Sunday and Dropkick Murphys as well as pop culture prints featuring movies such as The Princess Bride, Scott Pilgrim and The Burbs. If you could spend your whole life making something, what would it be? Portraits. I love illustrating faces. There is something so captivating about unique facial features that I can’t get enough of it. I see some faces and and I just have an itch to draw them.

thingsorganizesneatly.tumblr.com

Austin Radcliffe is a photographer, blogger, curator and art-world freelancer. Based in Cincinnati, he spends most of his time between the Midwest and NYC. Austin has worked with a growing list of galleries and institutions around the world, including Tate Modern in London, Art Basel in Switzerland and Mt. Comfort in Indianapolis. He also runs the Webby Award-winning tumblr and soonto-be-book, “Things Organized Neatly,” which will be published in Spring 2016 with Universe/ Rizzoli. If you could spend your whole life making something, what would it be? If I could exist making anything, I would make installation art with Taryn Cassella and Anna Martinez from Copy/Culture Studio.

SAM STALL, WRITER

TRUE BLUE, PAGE 24 Sam Stall is a veteran journalist who’s written or co-written 16 non-fiction books and three novels (none of which you’ve heard of). This is his first piece for Pattern, and it brings him one step closer to his life’s goal of appearing in every print publication in North America. If you could spend your whole life making something, what would it be? Like all freelance writers, I regularly toy with the idea of getting into another profession. Beer making sounds intriguing—especially since growing an epic beard is practically a job requirement for brew masters. But I can’t stand beer, which probably disqualifies me. Perhaps some form of carpentry work? Nah. That trade takes skill, extensive training, and good hand-eye coordination—all of which I lack. Better to stick with writing. At least I’m reasonably sure I’ll end each workday with the same number of fingers with which I started.

NASHARA M

ITCHELL

L

L SAM STA

AUSTIN

FE

RADCLIF

DOUG EADD

Y

AL BRA CKEN

AARON SCAMIHORN

DENVE

R HUT

T ASHLEY MINYARD

13

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SHAUN FREDERICKSON ART DIRECTION BY KATHY DAVIS AND LARS LAWSON STYLE BY LAURA WALTERS MAKEUP BY GREG ROSE FOR MAC COSMETICS HAIR BY SHAWN DILLMAN, SARAH VONEWEGEN AND JESSE NORRIS FOR HAIRSPRAY BY SHAWN DAVID PHOTOGRAPHY ASSISTED BY BETHANY FREDERICKSON, LAURA DE LA PAZ AND MATTHEW ZEGLEN WARDROBE ASSISTED BY CIERRA MCNEAL MODELS: AYDEN MORRIS, MARISSA AKERS, JORDAN ANTHONY AND RON STREET (LMODELZ MODEL MANAGEMENT) PROPS FURNISHED BY SOCIETY OF SALVAGE LOCATION PROVIDED BY BILTWELL EVENT CENTER DESIGN BY LARS LAWSON

ALL QUOTES TAKEN FROM “FRANKENSTEIN” BY MARY SHELLEY WEDDING GOWN, 317 BRIDE SNAKE BRACELET, VINTAGE, MURPH DAMRON SHOES, MODEL’S OWN

14 PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

15

LEFT: TOPHAT, COSTUMES BY MARGIE | CHOKER, PROFYLE BOUTIQUE | CLOCK NECKLACE, STYLIST’S OWN | RING, NICHE | FEATHER SHRUG, BOUTIQUE ON THE BOULEVARD | BUSTIER, PILLOW TALK | SKIRT, PROFYLE BOUTIQUE | RIGHT: GOGGLES, CITY MOTO | BOW TIES, STYLIST’S OWN | APRONS, SOCIETY OF SALVAGE

16 PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

17

DRESS, PROFYLE BOUTIQUE | BUSTIER, VINTAGE, MURPH DAMRON | BELTS, STYLIST’S OWN, TOGGERY | SHOES, MODEL’S OWN

18 PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

19

LEFT: JACKET, STYLIST’S OWN | BLOUSE, THE TOGGERY | RIGHT: DRESS, MARIE’S BRIDAL COUTURE GLOVE, VINTAGE, MURPH DAMRON | SHOES, BOUTIQUE ON THE BOULEVARD

20 PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

21

LEFT: LEATHER VEST, NICHE | DRESS, CALVIN KLIEN | CHOKER, THE TOGGERY | RAM NECKLACE, NICHE | RIGHT: DRESS, MARIE GABRIEL COUTURE

22 PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

23

TEXT BY SAM STALL + PHOTOGRAPHY BY HADLEY “TAD” FRUITS +DESIGN AND HAND LETTERING BY KATHY DAVIS

THE ALL-ABSORBING ART OF

24

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

25

26

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

T

he media insists on calling textile artist Rowland Ricketts a “maker.” Last year he and his Japaneseborn wife, Chinami, were one of ten winners of the 2014 Martha Stewart American Made program. And Metropolis magazine recently listed the couple among its best new American makers. The Ricketts appreciate the recognition, but aren’t quite sure the title they’ve been given fits. “One of the concerns I have with the maker movement is that it’s a trend, and trends come and go,” says Rowland, an assistant professor at Indiana University’s Henry Radford Hope School of Fine Art. “But we’re part of something that’s been done for hundreds of years by cultures around the world. It’s not a trend for us. It’s who we are.” Their lives revolve around Bloomington-based Ricketts Indigo, which colors textiles using organic indigo plant dye the couple grows, harvests, and processes themselves. Chinami, a weaver, uses it to add deep, vibrant blues to the kimono and obi fabrics she creates. Rowland employs it to make, among other things, textile-based art installations that have appeared everywhere from the Textile Museum in Washington, D.C. to the Cavin-Morris Gallery in New York City. Much of their indigo is grown on a small plot next to their modest rural home’s driveway. Come midsummer the short, bushy plants are harvested, placed on tarps in their front yard to dry, then trampled to separate the leaves— which produce the pigment—from the stems. The dried leaves are composted and dropped into vats in Rowland’s IU studio, where they ferment into dye. The duo, who have three young sons, are utterly absorbed in textile work and indigo production. Likewise, indigo has utterly absorbed into Rowland. The tips of his fingers are stained blue from submersion in the dye vats. But why bother with the laborious dye-making process when the product can be purchased abroad and cheap synthetics are easily available? Because the couple believes that the act of creating the pigment is as important as the pieces it enhances. It’s something akin to performance art – a way to infuse their products not just with color, but with history and tradition. “If we just wanted to dye things blue, there’s a million other ways that would be cheaper and quicker,” Rowland says. “But it’s also about the work of making it. What you’re making is perhaps not as important as the work you’re performing to make it.” Rowland found both his calling and his wife thanks to his fascination with Japan. He visited the country during his high school and college years, then returned after graduation to work as a high school English teacher. “I didn’t want to just go to Japan for a year or two and come back,” he says. “I really wanted to bring something home with me.” He returned with several things. First came a deeper appreciation for craftsmanship and local production. One of his most influential “teachers” was a century-old farmhouse where he lived for a while. Made almost entirely from locally-produced wood, stone, and other building materials, it helped him understand the huge spiritual and creative contrasts between making something and merely buying it. “It opened my eyes to those traditions of making that were really different from what I knew growing up suburban St. Louis,” Rowland says. 27

T

hat awareness of the local environment also changed his means of artistic expression. He was doing photography at the time, and thoughtlessly dumping his used developing chemicals down the drain. But when he learned that they were flowing, untreated, into a nearby river, he decided to find a more environmentally benign way to create. So he apprenticed to an indigo dyer. It was a fateful move, both professionally and personally. One of the craftsman’s other students was Rowland’s future wife, Chinami. She’d started her work life as a receptionist at a pharmaceutical company, but left to learn the exacting crafts of indigo production and traditional weaving. “I wanted a job I would never have to retire from,” she says. Working with indigo is a centuries-old craft tradition in Japan. But when the couple came to America they had to start from scratch. Today a handful of farmers (many advised by Rowland) produce domestic indigo. But for a while he and Chinami were the only show in town. That’s not surprising, given how hard it is to process the plant and use its pigment. One doesn’t simply dissolve some indigo into water and then drop in some fabric. Instead, a fairly substantial amount of composted leaves are placed in a vat, where they’re combined with other traditional materials. Bacterial action creates usable dye – a dye that can change its character based on the age of the container in which it sits, temperature, and any number of other influences. Each pigment vat is only good for between four to 12 months, after which the bacteria die and the material becomes useless. Indigo is worth the trouble, however, because of its resilience and longevity. Unlike most other dyes, it isn’t water soluble and never fades. One day the couple wants to move their dying operation to their country home, effectively placing all of their artistic endeavors in one location. Chinami already does her weaving in a cottage on the property, and the composted indigo resides in a small greenhouse. But if all this sounds unspeakably romantic, it’s not. The Ricketts take great pains to point out that their farm life is anything but idyllic. One of their goals is to hire someone to help with dye production, because though the process is integral to their artistic endeavors, the endless labor consumes a huge portion of their days. “It takes time from other things,” Rowland says. “When we’re out harvesting indigo, we’re not working or dying things.” That hard, unglamorous work forms the foundation not just for their art, but for their lives and livelihood. Rowland thinks that too many people, perhaps caught up in the perceived glamour of the artistic life, minimize or ignore this part. “All artists are businesspeople,” he says. “You have to find a way to continue to do what you want to do. Where you’re in the driver’s seat instead of having someone else calling the shots. Anyone who ignores that is just being willfully ignorant.” The Rickets take solace in the fact that even the most pedestrian aspects of their labor can inspire. For instance, in summer when they spread their indigo harvest on tarps in their front yard to dry, curious passersby regularly inquire about what they’re doing. The couple doesn’t mind sharing. It’s part of the creative process. “The work that we’re doing causes people to stop and look and ask questions,” Rowland says. “On some level that’s what art’s all about.” ✂ 28

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

29

INDUSTRY INSIDER

RALEIGH DENIM MAKING THE AMERICAN DREAM USING THE AMERICAN FABRIC TEXT BY ABBI JOHNSON + PHOTOGRAPHY BY POLINA OSHEROV

ON WHEN YOU DECIDE TO START A DENIM COMPANY WITHOUT ANY PRIOR EXPERIENCE: When the whole process began, Victor was coaching a soccer team, and Sarah was still in school. Victor had been on some wayward travels through Europe, where he found a favorite pair of pants: a pair of denim jeans tailored more like trousers. When they were worn through, Sarah and Victor realized that they couldn’t find a replacement. The solution? Take them apart and figure out how to make a new pair. Sarah explains, “Can we make a pair of pants? Yes we can. Can we make them better? Yes we can. Can we make them fit better? Yes we can. Can we make pants that fit more people than just Victor? ‘Hey Brad, let’s make some pants for you.’ ‘Hey, Tom let’s make some pants for you.’ Can we sell them? Oh, someone bought some pants.” ON PERSISTENCE: At the point that they decided to start producing a greater quantity of jeans, they needed to buy a lot of denim. Luckily, there was a mill that produced denim for some of the largest and most well-known denim brands in the country just an hour away. Victor called and emailed the sales rep at the mill where they were trying to buy a 200 yard bolt of denim every day for three months, and still didn’t hear anything back. He finally had to go to the sales rep’s boss in order to be able to buy denim. When they showed up to pick up the denim, they arrived at the gate meant for 18 wheeler trucks in their car. “It took 20 minutes to open the gate for a car. They were like ‘no one’s ever used this gate before’ and they’ve been around since 1905.” ON DOING WHATEVER IT TAKES: Their first big break was a meeting with Barney’s New York. At this point, their business was named “VS” as in “Versus.” In the week before the meeting they received a cease-and-desist letter from Versace. In that week, they had to recreate their brand from the ground up. “We coated screens, burned new logos, made new samples, made new line drawings…” Sarah lists off the number of things that they had to accomplish in the few days before their meeting. “And then we didn’t have enough money to get to New York, either.” Victor explains, “So, I called my dad to ask for money for the first time since I moved out of the house.” His response? “Oh, I think your 19-year-old cousin from Ukraine, who doesn’t speak any English, is in town. I think he’d love to see you.” In exchange for borrowing his dad’s minivan and a few hundred dollars, Sarah, Victor, and their intern, had to bring Victor’s Ukrainian cousin, on their very first selling trip to New York. ON SCALE: When Raleigh Denim was only sold at Barney’s New York, Sarah and Victor signed every single pair of jeans with a unique edition number themselves. When they realized they would need to double production, it raised a number of questions about how they would scale their brand, what their values were, and how they could make

30

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

SUBMITTED IMAGE

RUNNING A SUCCESSFUL FASHION BUSINESS IS A FAMILIAR DREAM FOR MANY BUT A reality for only few, like Sarah and Victor Lytvinenko of Raleigh Denim. Despite starting in somewhat unfavorable conditions—during the recession, in debt, and with little business experience—their persistent commitment to authenticity, as well as what has to be vats of sweat, blood, and tears has brought them well earned success. What began as a three person operation (the founders and an intern) has grown into a warehouse, known as “the Factory,” retail stores in Raleigh and New York City, denim distributed internationally, and collaborations around the world. This April, I was fortunate to hear Sarah and Victor first-hand as they shared their startup story, their successes, and the lessons they learned along the way, at a Pattern meetup. Some of their best advice—and stories—were too good not to share again.

those work. “We decided we’d share with every single person that has been with us long enough, to master it, in a way. Those people that have been here for two or three years that are as good or better than we are, we want them to be as invested as we are.” Even still, scaling is terrifying Victor says. “There are so many demands that are so time sensitive, with so much pressure. It’s terrifying, it’s exhilarating though.” The challenge is one that they consistently deal with and are comfortable knowing it comes with producing for themselves. ON HAVING A HEMMING MACHINE IN THEIR RETAIL STORE: Initially, when they opened their first retail store in NYC, they had a hemming machine that was functional but primarily for looks. Since the machine wasn’t being used, it almost seemed like something was missing, given that the authenticity of how the jeans were made was so important to the brand. Once they started using the machine, in the middle of the store, they found that people were so intrigued that most people ended up becoming clients. ON ASKING FOR HELP: “Small business is tough and a lot of the things you run into, maybe nothing’s really wrong, it’s just small business,” Sarah explained. They made use of local business resources, which helped with best practices, general questions, the basic things that are essential to running a business but aren’t your expertise when it’s your first start up. ON WHETHER OR NOT IT HAS BEEN WORTH THE JOURNEY: Building Raleigh Denim from an idea and a desire into a nationally recognized and premier brand has been anything but easy. Like many startups, it has taken a combination of perseverance, back-breaking work, and timing to overcome the perils of scaling, inexperience, and setbacks. Sarah and Victor started with a simple question—could they make a better pair of jeans? Years later, with a factory producing high-quality jeans for distribution in premium boutiques, they appear to have their answer. ✂

31

32

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

MIKE LYONS & BRAD DILGER. BAMCO. DYNAMIC MAKER DUO BRINGING INDY’S DREAMS TO LIFE. ONE IDEA AT A TIME. TEXT BY ERIC REES + PHOTOGRAPH BY ESTHER BOSTON ERIC REES: So what exactly does BAMCO do for its clients? BRAD DILGER (PICTURED LEFT): (Laughs) Generally, we make things. Those things could be anything from custom residential handrails to art pieces to music video props. We figure out how to do the project presented to us as efficiently as possible. MIKE LYONS (PICTURED RIGHT): It’s all over the place really. Recently, we worked with a local Pride Parade group to create their float. They wanted something good looking, but easy to pull. So we helped build this thing called a zonohedron, ten-foot-tall steel structure that they decorated. ER: How did BAMCO come to exist? BD: Well, Mike has been in Circle City Industrial Complex (CCIC) for much longer than I have. I had been doing some work up on the north side. We were both looking for a way to cut overhead costs. ML: It just worked out well since we are both the same age and at the same position in life. We’ve got families that need provided for. It just made sense. ER: What did you do before BAMCO? ML: Formerly, my business was known as !WOW-HUH? in this shop at CCIC. I started here about seven years ago making things for a living before we joined forces. BD: I worked at the Indianapolis Museum of Art for five years in their installation department. It involved working directly with artists to figure out how to make their vision actually work. Sometimes creatives have a problem getting over that conceptual hump and getting it done. I think that’s what us makers are for.

ER: How does BAMCO benefit creative clients?

ER: Tell me about your involvement with Ruckus.

BD: A lot of what we do as makers is provide artists the “canvas” on which to do their art. We worked with Spencer Finch on one of his installation projects. He has these awesome star features that are made from steel and florescent lights and then he tunes them to the color of stars in the galaxy. And then he hung them ten feet in the air. We had to figure out all the pieces to make it work.

BD: Pretty much everyone in the CCIC is excited for it. It’s going in at the south end of our building behind “the Big Red Door.” When construction starts, we’re going to be helping put this space together, but also helping the people who come here to work.

ML: If someone, creative or not, needs a part or something—anything custom-made to get a project done—we enjoy helping solve the problem. We’re a big proponent of open conversations and open-source. If you’re someone, like us, that geeks out over the complexity of things, we want to talk with you. ER: Anything advice to help the creative class grow in Indy? ML: As makers, we understand that it’s gratifying to solve your own problems, but we try not to get too caught up in that. Looking around at makers here in Indy, it’s a nice network of give and take. We don’t want to take work from other good makers who are doing good stuff. There seems to be a lot of competitiveness within that network. It’s a “I-can’t-let-anyone-do-thisbetter-than-me” mentality. I think if creatives can liberate themselves from that a little bit, it’ll result in much better work.

ML: We’re hoping that it brings a new group of people to this side of town. I really like the idea of makers and creatives being within the same space. There’s potential for some really cool stuff to come out of Ruckus. ER: What’s the biggest creative risk you’ve ever taken? BD: Probably the project that we just finished for The Band Perry. They came to us needing a life-sized structure of the logo for their new song “Live Forever.” We had to completely design, wire, and transport this enormous steel heart that lights up in seven days to make it in time for the music video shoot. It had a lot of elements that were firsts for both of us, so that just made everything harder. ML: When you’re on that short of a deadline, nothing could be an error or the whole thing would have fallen apart. I think we got it though. The end-product looked great. ER: Any last pieces of advice to makers or creatives? ML: Really quick, I think the sub-answer to the risk question would be quitting my job to start !WOW-HUH?. Wanting to take control over our lives and put together this business was scary, but gratifying. BD: Same here. I never regretted that decision. ✂

33

INDUSTRY INSIDER

MAKING SPACE FOR MAKERS OUTGROWN THE BASEMENT AND GARAGE? WE’VE GOT SOME SUGGESTIONS.

TEXT BY ABBI JOHNSON + PHOTOGRAPHY BY HADLEY “TAD” FRUITS AFTER BECOMING A FASHIONABLE TREND IN CITIES WORLDWIDE, ‘MAKERSPACES’ HAVE finally arrived in Indianapolis. Also referred to as hacker spaces, or community fabrication spaces, ‘makerspaces’ offer memberships to host craftspeople, artists and entrepreneurs, analog and digital alike. In addition to offering equipment and classes in traditional fields like woodworking, fiber arts and metalworking, they often have 3D printers, software, electronics, craft and hardware supplies and tools, that are shared by all the members of the space. Driven by the growth of the ‘sharing economy’ and the need for affordable and accessible space to support the maker movement, they’ve turned up in libraries and unused warehouses, and wherever else large groups of independent craftspeople reside. Many schools are starting to implement makerspaces on their campuses as well. The Maker Movement which is responsible for spawning these inclusive, experimental, and entrepreneurial communities of innovation started as a grassroots phenomenon, following the financial collapse of 2008 and the loss of almost eight million jobs. Seven years later the movement has taken hold of the entire country, and perhaps even the world. In the US, last year, President Obama proclaimed June 18, the National Day of Making, launching The Nation of Makers Initiative, and hosting the first-ever White House Maker Faire. This year, the Day of Making grew into a week, and Ruckus, one of Indy’s own nascent makerspaces made it into a White House press release outlining the many Maker related initiatives taking place around the country. Of course, Ruckus is not Indy’s only makerspace, and it’s certainly not the first— technology and robotics-focused Club Cyberia has been around since 2012, and is finally getting much deserved recognition. The new makerspaces launching this year primarily grew out of communities rooted in art and design. The Tube, originally Weber Dairy building, built in 1908, is the anchor for a larger community project in Garfield Park created by Big Car; Design Bank is the brainchild of design studio w/purpose and coworking community Studio B Creative Exchange, Ruckus came online due to the efforts of People for Urban Progress and Pattern while The Think It Make It Lab is set to open in the Herron School of Art + Design this fall fulfilling a long-time vision of its Chair of Fine Arts, Cory Robinson. Each ‘makerspace’ has its own flavor and different amenities to offer the creatives hungry to tinker, or take their big idea to the next level.

There is no question that makerspaces proactively contribute to the wider community and the neighborhoods in which they are located. From transforming old industrial sites into hubs of activity and creativity, to offering opportunities for people to come and learn a new skill or perfect an old one. Ultimately, makerspaces have proven themselves to be great economic development engines by helping connect small business owners to one another, and to essential resources. The community within the makerspace is important, too: members are quick to lend a hand when a fellow maker is at an impasse, share ideas, or ask for feedback. After all, the goal is not just to weld together steel and hammer together wood—it’s also to build a more productive city and a stronger community.

RUCKUS

FOUNDING ORGANIZATIONS: People for Urban Progress (PUP), Pattern, Riley Area Development Corporation LOCATION: Circle City Industrial Complex, 1001 Mass Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46204 PLANNED OPEN DATE: Spring 2016 MEMBERSHIPS: $85 - $325; Annual memberships also available EQUIPMENT/AMENITIES OFFERED: Industrial sewing machines, CNC routers, laser cutters & plotters, 3D printing, wet lab, hand tools, photography studio WEBSITE: indyruckus.com POLINA OSHEROV: “There was an increasing need for the growing fashion community to have a space to start a business, and the support to do so. PUP had identified the same need in among other groups of makers and artisans, so there was a lot of overlap and common benefits. It felt right to come together to create a greater density of makers of all kinds.” ERIC STRICKLAND: “In many cities, the makerspace location is an afterthought, not located in an ideal neighborhood, not in a true industrial building and lacking connectivity. The Ruckus location on Mass Avenue, instantly plugs it into Downtown Indy, the Mass Avenue Cultural District, and the Cultural/Monon Trail.”

34

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

RENDERINGS COURTESY SCHMIDT ASSOCIATES

35

INDUSTRY INSIDER

THE TUBE

FOUNDING ORGANIZATION: Big Car LOCATION: 1125 Cruft St., Indianapolis, IN 46203 PLANNED OPEN DATE: October 2015 MEMBERSHIPS: Access to the space will be primarily for Garfield Park neighbors, and Big Car staff and artists-in-residence. Classes open to the public will also be offered. EQUIPMENT/AMENITIES OFFERED: A shop for wood, metalworking, screenprinting and a darkroom. WEBSITE: bigcar.org JIM WALKER: “Ultimately I think makerspaces will help create a super local economy - something that already exists a little in the food realm. You can get local eggs, vegetables, and there are lots of benefits to local economies, jobs are created, and it changes how people connect. If there are places people can build things and then sell them, you’ll see more partnerships come together, stronger communities, and people won’t have to drive as far to get what they need.”

36

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

CLUB CYBERIA FOUNDING ORGANIZATION: Meetup group formed in 2012, moved to new location in 2015 LOCATION: 6800 E 30th St, Indianapolis, IN 46219 MEMBERSHIPS: Monthly, ranging between $35-$75 EQUIPMENT/AMENITIES OFFERED: Laser cutters, 3D printers, welder, CNC router, hand tools WEBSITE: clubcyberia.org MIC OWENS: “Of course with all the gadgetry that makes The Cyberia makerspace “STACKED”, I love the people who make up the community. We laugh, we play, we speak kindly to one another and have meaningful discourse about the world. And we do it all with really bad puns and some really insightful thinking. The thing I love most is that the members are from ALL walks of life. No matter what, our differences make us better and makes our creativity flourish in ways each member uses for their own enlightenment and achievement. we have and discuss big dreams and then go about making those things come to life, together.”

37

INDUSTRY INSIDER

THINK IT MAKE IT LAB FOUNDING ORGANIZATION: Herron School of Art + Design

LOCATION: 735 West New York Street, Indianapolis, IN 46202 PLANNED OPEN DATE: Fall 2015 MEMBERSHIPS: Open to Herron students only at this time; no memberships EQUIPMENT/AMENITIES OFFERED: Computers, cameras, scanners and printers—adjacent to a digital fabrication lab containing equipment including largeformat CNC routers and laser cutters, plasma cutters and milling machines. WEBSITE: herron.iupui.edu CORY ROBINSON: “Giving students the ability to experiment is one of the big benefits. Before we’d have to outsource the production, which results in exact, perfect results, which is great except that the students miss out on the creative process. Oftentimes the mistakes are the most interesting part of the process, giving students a great chance to problem solve.”

38

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

DESIGN BANK

FOUNDING ORGANIZATIONS: w/purpose, Studio B Creative Exchange, UNEC Development Corp. LOCATION: 3636 E 38th St, Indianapolis, IN 46218 OPENING: Soft opening February 2015, Grand Opening Fall 2015 MEMBERSHIPS: Daily and Weekly; $30-350 EQUIPMENT/AMENITIES OFFERED: Large Scale-Plotters, Laser and Vinyl Cutters, and 3D Printers WIL MARQUEZ: “The opportunity to ‘make’ opens up new markets and enables the spirit of ingenuity to build platforms for economic growth, entrepreneurship, and social impact. The impact is also global - as Design Bank belongs to online global certification networks that connect us to 18,500 3D printers and makers around the world. The idea of micro or clean manufacturing reappearing in many communities throughout the United States is real.” ✂

39

FASTEN YOUR LOOK TOGETHER WITH THESE RIVETING PIECES.

PHOTOGRAPHY AND ART DIRECTION BY CHRISTOPHER WHONSETLER ASSISTANTS EMMA ROGERS AND KEVIN MEDLIN DESIGN BY KATIE SNIDER

40

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

PEOPLE FOR URBAN PROGRESS, CHIEF BIFOLD DOME WALLET, SILVER IN THE CITY, PEOPLEUP.ORG/GOODS.

41

WILD N’ SEXY WILD II: HIGH TOP SUEDE RED BOTTOM, PATTERN WORKSHOP WILDNSEXYCLOTHING.COM

RIGHT: ROCK MY BOWTIE, SOLID PRE-TIED RED $25.00.

.

42 72

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8 BLUMLUX PRINCE QUATTRO COUNSEL W/ DIAMONDS, BLUMLUX BOUTIQUE, BLUMUX.COM

FASTEN YOUR LOOK TOGETHER WITH THESE RIVETING PIECES.

HOUSE OF 5TH PS*FU BACKPACK, HOUSEOF5TH.COM

43 73

FASTEN YOUR LOOK TOGETHER WITH THESE RIVETING PIECES.

DISTRICT 31 STERLING & WALNUT BENTWOOD RING, DISTRICT-31.COM

44

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

TEXT BY ASHLEY MINYARD + PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEPHEN SIMONETTO + ASSISTANT EMMA ROGERS FEW THINGS MANAGE TO DISTINCTLY appeal to the senses more than leather. The smell is intoxicating, nostalgic, and organic, wafting into the nostrils to deliver a calming dose of pleasure. To the touch, leather is smooth. The hand glides across its surface easily, the fingertips encountering slight ridges and rough patches of the hide, a diary of the life of its bovine owner. When transformed into a product, leather takes on a new existence. While maintaining the character of its being, it faces tight stitches, embossed ridges, careful folds, clean cuts, rough embellishments, artificial texture, and softly-worn suede. The look is different depending on the hands that formed it. Indiana is lucky enough to have several leather crafters, all with different aesthetic, but a true dedication to producing quality leather goods. Although the materials they work with are similar, each craftsman takes his or her own approach to the hide.

46

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

HIDE BOUN 5 TYLER MECHEM LM PRODUCTS

ND 4 CHRISTIAN RESIAK HOWL AND HIDE

1 BROOKE LINDEMANN LEATHER.FEATHER.STONE.

3 MICHELLE WARBLE BUSTY’S FUN BAGS

2 TRUEN JAIMES HOUSE OF 5TH

47

1 LEATHER.FEATHER. STONE. ORGANIC CHIC

Brooke Lindemann is the founder of Leather. Feather. Stone. Created in her home studio, she shapes pieces of leather using the raw edge and true shape of the hide to inform her designs. This results in chic and simple products with soft textures and visual aesthetic. Each product is as unique as the hide from which it originates. Lindemann is a stay at home mom who decided to take on a creative career at home. Her company is largely run from Etsy but her products also appear in select boutiques. Her company has taken off in just a few short years, but actually began in 2011 with an unfortunate accident. “I had a pair of moccasin boots that I absolutely loved but my dog ate all the fringe off,” says Lindemann. “I bought some pieces of scrap from a leather store in Indy and replaced the fringe. I made it really wild and shaggy, and basically improved them.” She used the leftover leather to create belts and cuffs to sell on Etsy. That transformed into clutch bags and evolved into a full bag collection. She sources her leather from a local family owned leather business, one that she prefers to keep top secret. Her choices in leather are very selective, and each product is informed by the natural raw edge of the hide. “I buy leather that I’m drawn to and that I know will make beautiful items,” says Lindemann. “For example the crackle leather that is used on some of my bags, I have no idea where it comes from, and I can’t even find it online. I enjoy the hunt of stumbling into something awesome. It keeps things fresh for me and creates a demand for my product.” Lindemann has general patterns that help provide a standard in shape and size for her bags, but she always leaves the edge open for interpretation. Another variable is the tassel that adorns each bag. The result is a snowflake line, similar products, but each organically unique. She also creates accessories outside of the bag collection using the leftover leather to create tassels, cuffs, and earrings, utilizing as much of the hide as possible. The majority of her business revolves around playing, something that sets her apart. “I grew up watching my mom sew, and I’m not great at sewing clothing but I’ve got an eye for detail and aesthetic. It’s important for me to have a nice finish to things. I’m self–taught but I have honed my craft. I’ve always felt like more of a sculptor than a seamstress.”

48

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

2 HOUSE OF 5TH

3 BUSTY’S FUN BAGS

Situated at a luxury price point, House of 5th is delectably designed. The accessory line spearheaded by Truen Jaimes started in 2008, but only turned to leather goods three years ago. The company focus is to create fine leather goods & accessories that cater to the tech and travel savvy customer in an artisan fashion. The resulting product is a bold yet streamlined approach to fashionable tech.

Busty’s Fun Bags are just as interesting as the name. Created by Michelle Warble, the bags incorporate upcycled leather goods and often patterned upholstery fabric for a whimsical and homespun aesthetic. The name derives from her old roller derby nickname, Busty Sanchez, and the company came into existence after her retirement from the Naptown Roller Girls team. Although she only makes them on the side of her full–time job, the craft has gone from a hobby of creating her own bags to making products for others.

LUXURY ARTISAN

House of 5th’s selling point lies in elaborate finishing techniques and originality of design. Jaimes has full control of the operation of the company, and all production is done by artisans in his Fountain Square studio. Eighty percent of the leather is dyed in house with their 19 proprietary colors. The top surface dye fades and distresses in certain areas to show the beauty of the leather over time. “We only use vegetable tanned, top– grain, premium leather for our hand died line,” says Jaimes. “It ages nicely and softens over time, but it is very thick so it doesn’t tear.” The process of construction is a mixed production strategy using industrial machinery or hand stitching, depending on the product. Part of what makes House of 5th so successful is their investment in top of the line equipment, acquired over time, to allow for advanced, streamlined production in–house. Instead of placing concern on money saving techniques, Jaimes seeks ways to make products more hand finished and artisan. “I use what I call a reactionary design process,” Jaimes explains. “Where a lot of designers will be fine just focusing on trend, for me it’s really important to study and analyze the data of what’s trending but then offer the consumer something that they’re not going to find somewhere else. Sometimes it’s a forced design method. If I find something that I really want to do, but the market is already responding to it, I will force myself to design in a different direction. I want it to be relevant, but I want to create something that is not on the market.” House of 5th’s latest collection is architecturally inspired, thanks to the recent completion of his own home and new studio, made evident by the punching and linear designs that mimic those found in the industrial space. Even as his designs develop, Jaimes still aims to keep the focus on the quality and production techniques that truly create the luxury artisan products.

WHIMSICALLY CRAFTY

“I really had no sewing experience, just home economics in seventh grade, but I decided I could do it. I sewed a purse, and it went from there. I started with regular fabric, moved up to quilting and upholstery weight fabric, then on to vinyl, and now I’m working with leather.” The bags have clean lines, geometric patterns, and raw leather. She sources the material from both old leather clothing and local leather shops. Her products are then either hand stitched or constructed on her industrial sewing machine in the attic space of her home she’s dubbed “The Sweatshop.” She sells her bags online and at various craft fairs to artsy customers in Indianapolis, Cincinnati, and Louisville. “I see things in the market I like and then use my weird twisted mind to put my own spin on them.”

4 HOWL AND HIDE

TRADITIONALLY RUGGED Christian Resiak never intended to start a leather business; he simply saw a product and decided that he could do better. In less than a year, this idea transformed into Howl and Hide, a completely hand sewn and American made leather company. “I would stay up for hours and teach myself how to hand sew on crappy old leather jackets,” says Resiak. “I spent a lot of time studying and refining how to do this traditional trade that’s been long forgotten. It’s evolved to what it is.” Functionality is the biggest focus of Resiak’s designs resulting in simple, timeless pieces. Preferring to skip the trinkets, there are no gimmicks to hide behind. He prefers clean silhouettes and few embellishments to let the leather and construction processes speak for themselves. “I take pride that everything is completely hand stitched,” says Resiak. “You lose the integrity of the item by machine stitching. I know every stitch that goes into the bag because I do it with my own two hands.”

All of the leather Resiak sources is full– grain hide from American raised cattle. He prefers leather that shows distress from the life of the animal, adding a rugged appearance to the product without having to rough it up himself. He is very passionate about sourcing everything from the United States, even his tools. His traditional American values and construction methods make for a lucrative small business that has picked up quickly, but Resiak plans to stay small. His products are made to order, so although he has a collection of designs, he will only start creating a bag when a customer places an order. “I’ll finish a bag, put it in a box, and send it,” says Resiak. “I don’t take it off a dusty shelf. It’s from my hand to yours. It’s me making it specifically for you‚— maker to consumer.”

5 LM PRODUCTS

RUSTICALLY CRAFTED

LM Products may be a familiar brand that comes to mind, but more in relation to the music business. The company started in 1975 and is internationally known for selling quality guitar straps and musical accessories. LM Products has been passed down for generations, and now Tyler Mechem runs the company alongside his father, LJ. But Mechem has taken on his own project within the company, creating leather bags and accessories with the same high–quality crafting expertise passed through his family. “I thought about breaking away from LM Products early on, giving the bags a different name and branding them differently, but I’m so proud that it’s a family business. I want to keep that aspect with the name. I didn’t want to have some contrived brand for the bags; it’s still just us in the workshop making it,” says Mechem. While about 30 artisans work on the guitar straps, only Mechem and one other lead craftsman create the bags. The workshop is filled with craftsmen who have been with the company for upwards of 20 years. Mechem learns from working alongside those makers and from his father and grandfather. He consults his father with bag designs, who helps him to push the concepts further past the first iteration of the product. He uses the experience gained from his family to uphold the brand’s quality.

LM PRODUCTS PHOTO BY TYLER MECHEM

“We have a strap here that is 10 years old. It has been toured around forever, and it looks better than the day we made it. We think of things in advance to keep products from breaking down,” says Mechem. “In the bags, the stitches will end and we’ll anchor it with a rivet—that way the stress of years of use has two types of securement there that keep it from tearing apart. We anticipate how it’s going to be worn and react to that.” The aesthetic of the bags at LM Products is timeless and somewhat rustic, but all edges are finished and polished. The function is built in, and the shapes and design of the bags are classic, no exuberant flourishes needed. The leather looks pre–worn, showing the marks from the construction process and the hands of the leatherworkers. The beauty of the bag only increases with age.

LEATHER. FEATHER. STONE. PHOTO BY POLINA OSHEROV

Mechem plans to expand the accessory aspect of the business, creating more products and moving past the music focus, but he says there’s nothing that can take him away from LM Products. He plans to one day pass the trade on to his son, who is now only 2 years old, if he’s willing and ready.

HOWL AND HIDE PHOTO BY POLINA OSHEROV

“One time when I was younger there was me, my father, grandfather, and great grandfather all working together at the same time. Four generations. Not a lot of companies have that kind of legacy anymore.” ✂

HOUSE OF 5TH PHOTO BY ANNA ZIEMNIAK

HOUSE OF 5TH PHOTO BY ANNA ZIEMNIAK

BUSTY’S FUN BAGS PHOTO BY MICHELLE WARBLE

49

SHOWROOM OPEN THURSDAY—SATURDAY, 12-5PM

MADE IN INDIANA MEET SOME OF INDY’S TOP MAKERS.

© ITSMESIMON/SHUTTERSTOCK

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ESTHER BOSTON AND POLINA OSHEROV + DESIGN BY KATHY DAVIS

51

JERRY LEE ATWOOD

I ANISHA BROWN IS EXACTLY WHERE SHE BELIEVES GOD WANTS HER to be. It’s this unshakeable faith, paired with an incredible work ethic and sparkling personality, that is the driving force of Poppy Seeds, her swimwear line. She wasn’t always in swimwear; in fact, her love for fashion and desire to have her own line began with an interest in lingerie. After graduating from the Art Institute of Indianapolis with a degree in fashion design, she set about making her dream of having her own lingerie line come true. But on the advice of a customer and mentor, she soon turned her focus to swimwear. “I had no interest in swimwear,” Brown says. “I only took one stretch course at the Art Institute. But [she] was insistent that I should look into doing swimwear, because lingerie was more of a luxury, but women would always need a swimsuit.” It’s advice that has paid off. Now several years into the line, with multiple collections under her belt, Poppy Seeds is almost to the point where Brown can begin to hire an employee and think about expansion. Currently, she’s working on getting more wholesale accounts in far-off, beachy locations, like California or Hawaii. Locally, Poppy Seeds can be found via trunk shows and at Boomerang BTQ. Brown also maintains a web store, and takes custom orders. She’s also working to drum up greater publicity through Julia Rutland’s Aesthetic Design Style House. “It’s a dream come true,” she says. “There are good days, and then there are incredible days.” Poppy Seeds draws inspiration from old tv shows and strong, iconic women like Lucille Ball. Appropriately, collections are named after their inspirations, with recent ones being “Jeannie” and “All About Eve.” Bright colors and patterns are her signature, as well as vintage-inspired, but creative cuts—similar to what you might expect from Betsey Johnson. Favorites include her “Perry” high-waisted yellow polka dot bikini (yes, like the song) from one of her first collections, the “Caviar” plunging halter one-piece, and the “Julip” halter one-piece. As a young entrepreneur, Brown is enthusiastic about encouraging others to pursue their dreams and keep the faith. “Be patient,” she said. “Work the process and do your research. Learn from others. And most of all, have faith that you are in the right place, at the right time. ” She attributes much of her success to the support she’s received from the creative class in Indianapolis. From photographers and models to makeup artists, boutique owners, and event producers, the loyalty to showcasing and growing local talent impressed and inspired her. She also credits her family, husband, and son for their tireless support as she achieves her goals. But in the end, it all comes down to faith: in her God-given talents, and in herself. —TEXT BY MARIA DICKMAN

T ALL BEGAN WITH A FRUSTRATION WITH WESTERN SHIRTS. IN 2000, JERRY LEE Atwood was wearing them and working in a coffee shop, but the shirts were hard to find in his size. Spurred into action, he bought a pattern, borrowed a sewing machine, and, without ever having sewn anything, tried to make a shirt. “It was a disaster,” he says. But he enjoyed the process and recognized the potential. He purchased “Reader’s Digest Complete Guide to Sewing,” not long after—“the best instructional book”—and continued his journey of self education. For a time, Atwood worked for a custom drapery shop, whose owner hired him after hearing of his interest in learning to sew. In 2011, he responded to a job opening from the Indiana Repertory Theatre (IRT), and although he was completely unprepared for the interview, the manager took a chance on him. “We got to try something new for every show,” he says. “It was never monotonous.” He credits the IRT for many learning experiences, including a trip to Chicago to see the Charles James exhibit, as research for “Fallen Angel.” “It was fun to see the whole shop work on that project,” he says, referring to the red dress. Atwood’s biggest risk would come in 2014, when he left the steady work at the IRT and struck out on his own for the first time. He works in his home studio, now, primarily on custom chain-stitch orders, while he perfects his patterns for jeans and, more recently, experiments with making t-shirts. His designs are inspired by historic clothing and vintage machinery. He has a collection of Cornelys, chain-stitch embroidery machines with a universal feed to sew in any direction. Some of the machines are in use, while others he is rehabbing for sale, as a labor of love and preservation for future generations. His love of Western wear comes from the childhood trips he’d take to Nashville with his father. Although he didn’t care for the music, the nostalgic style stuck with him. “I feel fortunate to be able to make money doing what I do,” he says. “But there is never enough time to try everything that I want.” Part of this is the challenge of trying to “do it all” as a small business owner. “It’s tough being your own motivation and marketing,” he says. Despite that, the majority of his customers, particularly for his custom work, reside outside of Indiana. In the future, Atwood wants to increase the quantity of work in chain stitch embroidery. His goal is to find more repeat customers, especially other businesses or brands, because doing larger orders for other businesses creates a steadier income than taking individual custom orders. He’s built a great business relationship with Jess Snell’s Rockin’ B Clothing, now based in California, for whom he has had repeat orders. He’s ready to grow, although his expansion plans as yet don’t include hiring an employee, as training people to use the Cornelys is very time-consuming. Atwood admits there are inherent challenges in running a Western-wear business in the Midwest; namely, that there’s a lack of large festivals—maker fairs, music festivals, D.I.Y. fairs and the like—creating sales opportunities. “Living in the Midwest is an island, and traveling isn’t practical for me,” he says. He also hasn’t found the perfect studio in a neighborhood in which he feels comfortable and that is also affordable, so for now, he’s working out of his basement. And, as the father of a young son, his work-life balance involves part-time day care. All these things add up to a feeling of isolation from others with similar businesses. “I hear about someone else making jeans in the city, and think, ‘Wow, I had no idea someone else was doing that here,” he says. By the time this story goes to print, however, things will have shifted dramatically as Atwood has been accepted as one of the residents of the newly launched Pattern Workshop—a pop-up makerspace and retail showroom in a storefront on Mass Ave in downtown Indianapolis. He jumped at the opportunity for more visibility and to become better connected to others who share his ideals of creating beautiful items by hand and from scratch. “I’m really excited to be a part of this project, and to play a role in helping grow the maker movement here in Indy.” In the space, Atwood plans to focus on making selvedge denim jeans for men, while continuing to fulfill his custom orders. To those just starting out, take note. Atwood credits others’ encouragement to help get him where he is today. Important, though, is that he’s carved his own path. “Find a niche that you enjoy that not a lot of people are doing, and make a name for yourself,” he says. “Teach yourself to be good, and eventually, someone will notice.” —TEXT BY CATHERINE FRITSCH

poppyseedfashions.com

hoosier-built.blogspot.com

DANISHA BROWN

D

52

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

53

54

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

CHRISTOPHER STUART TEXT ON PAGE 56

IAN OEHLER

W

HEN YOU MEET THE MAKER OF SOMETHING AS AWESOME as the adult sit-n-spin, you walk away feeling as though you just caught up with an old friend. Well over six feet tall, his long brown hair pinned back with self-made wooden hair sticks, Ian Oehler has his feet planted firmly on the ground. It’s an unconsciously firm stance, a nod to his strong Indiana roots. He sees himself settling down here, long-term, although if pressed, he wouldn’t be opposed to a stint in Germany, from where his grandparents immigrated circa WWI. He’s often found in Fountain Square, or spotted en route to his hometown of Carmel, Indiana, via the Monon Trail (I’m sure he would zip past me when I keel over at mile two). At 30, Oehler’s one of the young people making an impact on Indianapolis’ creative culture. He’s a maker, and a tinkerer. “I’ve always wanted to be innovative,” he says. “I grew up working in a wood shop. My father is a furniture maker. He primarily makes kitchen cabinetry in a shop attached to his house. It was my job in high school, and sometimes my punishment. I realized I had to find my own way.” Finding his path took him from a seven-year stint in Bloomington at Indiana University, where he studied environmental science, to the golden coast of California, where he worked in snowboard repair in the Squaw Valley region of Tahoe. After that, he moved on to a fast-fashion shop in Los Angeles, where he assisted in digital media production, before returning to Indianapolis in November of 2012. “I really missed having a shop, among other things,” he says. “It felt very stifling in LA. You can certainly find your niche. However, it’s a lot of people working competitively, [whereas] here, it’s a lot of people working together. “ Then, he met with Jim Walker, the executive director of Big Car, to talk about his desire to work with a non-profit. Walker invited him to a staff meeting and Oehler started showing up. He volunteered for a time, and even did shows in their old space (a converted service station on Lafayette Road) and working for commission. He then started doing game night once a month for Big Car, where he created ping pong paddles and tables. Which leads us to the present. Oehler works out of his father’s shop, though he hopes to be involved with The Tube Factory, which is set to open in late 2015 on Shelby and Cruft streets across from Garfield Park. He tries (and fails) to convince me he’s not a master maker. Rather, he creates purely for the love of making something. “I don’t really want to make a living off what I make. I just enjoy making things for myself, and for people around me using reclaimed wood,” he says. He enjoys how forgiving woodworking is, and how he can make a lot of different, functional designs. Precision-driven, Oehler seeks to build a pedal-powered tool, like that of a potter’s wheel, in order to be more efficient in grinding and sanding, although he does enjoy working with hand tools. Outside of his work with Big Car and his father’s shop, he dabbles in music, performing as a tenor with the Indianapolis Symphonic Choir. “I sing for myself when I’m not singing for ISC,” Oehler says. “In addition to singing, I like to play my main instrument, the marimba. I started playing it in the third grade.” Occasionally, he can be found out and about in search of good dancing opportunities, like at Night Train at the Hi-Fi or Real Talk at White Rabbit Cabaret, and there’s a good chance he’ll be singing along on karaoke night. “I sang ‘Kiss Of A Rose’ at the Metro on a Thursday night recently,” he says. “It was not well received.” You can try out one of Ian Oehler’s adult sit-n-spins on Monument Circle through October. The public installation is in association with the Spark Program by Big Car, which is a 501c3 non-profit arts organization and collective of artists in Indianapolis. —TEXT BY DYLAN HODGES instagram.com/thehighhills

55

CHRISTOPHER STUART

C

HRISTOPHER STUART IS A GEM—ALBEIT A SOMEWHAT HIDDEN one. He works out of an industrial park in Carmel, but within his studio is a wealth of great modern design (never mind the AT&T warehouse next door). He didn’t start out as a furniture designer, or even an industrial designer. Instead, he started in graphic design at an industrial design company here in Indianapolis. At first he was just an assistant, but then his natural drive took over, and he began staying late to teach himself CAD to make himself more valuable. Cue the recession. At the first major downturn, he was laid off. “No one was hiring industrial designers, because no one was producing anything,” he says. “So I thought, ‘What can I do?’ At the time, all I had experience with was designing consumer electronics. So I was like, ‘What can I build from the hardware store?’” He started tinkering and researching, and discovered a movement centered around this D.I.Y. ideal, particularly in Europe. And not D.I.Y. as most of us think of it—you know, all Pinterest and arts and crafts. Stuart’s D.I.Y. is rooted in great, simple, modern, somewhat sculptural ideas. “Like this is art, but the artist didn’t have a budget, so he went to the hardware store and bought shit, but the design was really good,” he says. Thus the idea for his books, “DIY Furniture” and “DIY Furniture 2,” were born. Around the same period of time, Stuart enrolled at Herron School of Art + Design, to get a degree in furniture design. “My original thought was to go design for a furniture manufacturer,” he says. “I’d then have a better understanding of the making side, to help me better design the products.” “As an adult, art school allows you to be selfish and think about what you really want, from your work and your life,” he says. “That pause from the real world really allowed me to think about what I wanted, and it was at that time that I realized I really didn’t want to go to work for someone else. So I started thinking about opening my own studio.” While at Herron, Stuart worked as a freelancer, which allowed him to build up some clients and make his goal come to life. He split his studio in half, part shop, part office, which allowed for on-site fabrication. “Any downtime we had on the traditional service side—stereotypical design work for corporate clients with very little making involved—any lull we had, we would work on our own designs and make them in-house,” he says. The end goal: to move more toward self-initiated work. “Eventually, I wanted the service side to match the work on the self-initiated side,” Stuart says. “Which is where we are now.” His studio, LUUR, has made a name for itself in minimalistic modern objects, but almost always with a surprise twist, which has garnered acclaim from Architectural Digest, Design Milk, and Dwell Studio, among others. His new-ish North South bracelets, gorgeously made in-studio of Corian, is a modern spin on the friendship bracelet, with the ability to mix and match colors and textures thanks to magnetic closures. The HiLo tray, made of Stuart’s current favorite wood, white oak, is an exercise in form and restraint. The U Bench, his highest end piece thus far, is part sculpture, part seating space, stunningly rendered in steel with a dark patina. “Some people might think of simple and minimal as a negative,” he says. “I look at it as a challenge, because it can easily end up looking like everything else out there that’s simple and minimal.” LUUR also stands out because of the range of the objects they produce. “I think one of the beautiful things about our studio is that we don’t paint ourselves into a corner,” he says. “We do high end [like the stunning steel U Bench], but we also have more affordable pieces [the bracelets, trivets, and trays].” In many ways, this approach gives anyone an entryway into good design. LUUR’s approach also dictates the materials, as they try to produce as much in-shop as possible. “I look at it as, ‘What can I produce in-house with the equipment that I have?’” he says. “I like to work with materials that resonate with me, particularly natural materials. There’s something beautiful about that. The materials that stand out to me feel like they have longevity to them, so even though my style is minimalistic, it feels like something that would have been used a long time ago.” Stuart draws inspiration from art, architecture, fashion—and other designers, of course. “I think fashion, in particular, is really starting to push the limits with structural design,” he says. “The list goes on and on: Le Corbusier, Carlo Scarpa, Scott Burton. It’s pretty massive.” But of course, there are limits to his capacity to D.I.Y. and design. “It takes a lot of time to make something,” he says. “Materials always cost more than you think. The general public’s idea of what things should cost is skewed because of mass manufacturing. I think that’s a major challenge. It’s difficult to get the average consumer to understand why our costs are what they are.” So where, then is the line between the maker and the designer? “I think you can be all of them,” he says. “It’s all getting blurred nowadays, which I think is really good, personally. Why can’t objects be functional as well as beautiful? Why can’t functional objects make you feel the way you feel when you look at art?” He makes a strong point. His next steps include several showcases and continued development on his retail side, as well as furniture design in-line with what they achieved with the U Bench. LUUR’s also working on the interior design for a new hair salon that is soon to open in Nora. In the meantime, Stuart will continue to make his own opportunities, both here and on the coasts. LUUR is truly a studio on the verge; with his determination to put out outstanding work and break boundaries in traditional industrial and object design, as well as sculpture and art, there’s little doubt that it’s only a matter of time.—TEXT BY MARIA DICKMAN

luurdesign.com

56

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 8

ALLISON FORD

A