pattern

cu ltivate s the skills and professional development of e merging cre ative s to make in dianapolis a world-class destination for cu lture , fa sh ion , art, and music .

by inve sting in the training and mentorship of the n ex t gen er ation of talent, we will help to develop tomorrow

’

s cu ltu r al workforce in central indiana.

IN THE MIDST OF MY EVER-EVOLVING PATTERN REALITY...

I’VE CAUGHT MYSELF FEELING NOSTALGIC FOR THE EARLY DAYS of PATTERN–early days we shared with Big Car, Dreamopolis, Oranje, People for Urban Progress, Printtext, iMOCA, PechaKucha, and many others. Do you remember Fashion’s Night Out? Maaaannnn!! It was a time when the energy and the buzz of potential in Indy was palpable. If you were here for it, then you know what I’m talking about.

SADLY, NOT ALL OF THE CULTURAL VENTURES LISTED ABOVE ARE ALIVE today. Some shut down long before the pandemic, others because of it, but driving around Indy late last fall, it was hard for me not to feel downhearted seeing Indy looking like it had time warped back to 1998, the year I moved here from Chicago.

THANKFULLY, I RECEIVED AN INVITATION TO GRAB A DRINK AT STRANGE BIRD, AND I’M NOT SURE ANYTHING could have lifted my urban spirits the way that night at a little tiki bar in Irvington did. I felt the familiar sense of pride in this city creeping back in, and once I opened up to the possibility, I couldn’t stop seeing it.

FAST FORWARD SIX MONTHS AND INDY IS BURSTING AT THE SEAMS WITH EVENTS, NEW RESTAURANTS and bars, and significant infrastructure projects throughout the region that will make our downtown and neighborhoods feel more cosmopolitan–and just maybe, more equitable?

I WAS SUDDENLY LEFT WONDERING IF I WASN’T HIP TO ALL THE NEW AND EXCITING EXPERIMENTS springing up to replace those that have gone by the wayside, perhaps others were missing out on signs of cultural spring in our city and state, too. So our team went a-lookin’, and we found plenty of new (to us!) and intriguing efforts happening all around us, all the way from Gary in the north down to New Harmony in the south.

THIS STATEWIDE SURVEY OF NEW MOJO BEGS THE QUESTION: WHAT ARE WE HOOSIERS MOST PROUD OF? If many Hoosiers stand for family values, many also stand for gay pride. In theory, why can’t these exist as two sides of the same cool coin?

AS TIME ROLLS ON, I ALWAYS LOOK FORWARD TO THE REMINDERS OF WHY I FELL IN LOVE WITH INDY IN THE first place, and nothing rejuvenates my regard than discovering new cultural hotspots, and connecting with dreamers young and old who want to take a run at making Indy a better place for those of us who use the right side of our brains.

SOME OF THIS ACTIVITY IS HAPPENING DUE TO PENT-UP DEMAND, BUT SOME IS SURELY THE RESULT OF the unprecedented amount of financial support unleashed on culture and arts communities to prevent them from drying up completely during a two-year forced hiatus. It’s always nice to have some startup cash to get things rolling, right?

AS ALWAYS, THERE ARE FAR MORE STORIES TO TELL THAN THERE IS SPACE TO SHARE THEM … SO WE HOPE you will forgive us if some noteworthy amenity or story has been omitted. I welcome your feedback. Don’t forget PATTERN has a digital magazine as well–and we’re always looking for uplifting stories about our home state, its creatives as well as those who make creative self-expression possible.

HERE’S TO INDY & INDIANA!

PHOTO ©BENJAMIN BLEVINS

POLINA OSHEROV EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 2 EDITOR’S LETTER

BRAND PARTNERSHIPS

info@patternindy.com

DISTRIBUTION

To stock PATTERN magazine please contact us at patternindy.com.

Printed by Fineline Printing, Indianapolis, IN USA

PATTERN Magazine

ISSN 2326-6449 is

Proudly made in Indianapolis, Indiana

DIGITAL

Online Content Manager

Cory Cathcart

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Michael Ault

Alan Bacon

Michelle Griffith

Julie Heath

Freddie Lockett

Lindsey Macyauski

NaShara Mitchell

Sara Savu

Barry Wormser

SUBSCRIPTION

Visit patternindy.com/subscribe

Back issues, permissions, reprints info@patternindy.com

FASHIONING A COMMUNITY

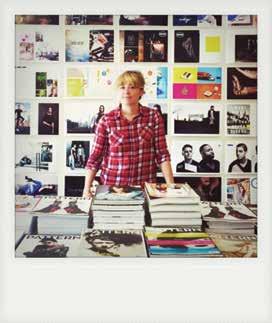

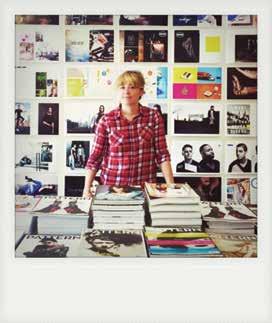

EDITORIAL Editor & Creative Director

Polina Osherov

Design Director Emeritus

Kathy Davis

Design Director

Lindsay Hadley

Design Fellow

Carrie Kelb

New York Editor

Janette Beckman

Editorial Intern

Katie Freeman

Photography Intern

Kelsey Matthias

Copy Editors

Jessie Hansell

Anne Laker

Lauren Manges

Charlie Sutphin

DESIGNERS

Megan Gray

John Ilang-Ilang

Julie Valentine

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Esther Boston

Hadley ‘Tad’ Fruits

Jay Goldz

Clint Kearney

Solomon Mabry

Myriam Nicodemus

Francis Nwosu

Polina Osherov

Caleb John Smith

Amy Elisabeth Spasoff

WRITERS

Tabitha Barbour

Philip Barcio

Alexa Carr

Cory Cathcart

Colin Dullaghan

Crystal Hammon

Denise Herd

Kary Kovert Pray

Dylan Lee Hodges

Anne Laker

Samuel Love

Adrian Matejka

Dawn Olsen

Terri Procopio

Julie Rhodes

Caleb John Smith

Allison Troutner

Jenny Walton

Iris Williamson

PATTERN IS GRATEFUL TO THE FOLLOWING FUNDERS AND PARTNERS FOR THEIR SUPPORT:

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 4

5

CONTENTS

PATTERN ISSUE NO. 21

patternindy.com

WORDS

EDITOR’S LETTER, 2

CONTRIBUTORS, 8

Q+A KELVIN BURZON, 18

HOODOX, 20

ALL MADE UP, 26

REVVING UP, 32

HIT PARADE, 34

Q + A CHRIS NEWELL, 45

HOOSIER PRIDE, 47

THE WHITE RIVER

WABASH, IN

LYLES STATION, IN

NEW HARMONY, IN

GOSHEN, IN

MARION, IN

SPENCER, IN

MUNCIE, IN

CLARKSVILLE, IN

CRAWFORDSVILLE, IN

HUNTINGTON, IN

ALI BOMAYE, ALI BOMAYE, 82

Q+A MAURICE BROADDUS, 84

COWBOY GOVERNOR, 86

IN-RESIDENCE, 92

ABOUT FACE, 100

EXTRAORDINARY GARY, 102

FRIEDA GRAVES

SAMUEL LOVE

LAUREN PACHECO

MAYOR JEROME PRINCE

DECAY DEVILS

OP-ED, 136

IMAGES

SATIN FINISH, 10

NEON THAW, 116

LIVING IN COLOR, 126

VOLUME 20 POP-UP, 134

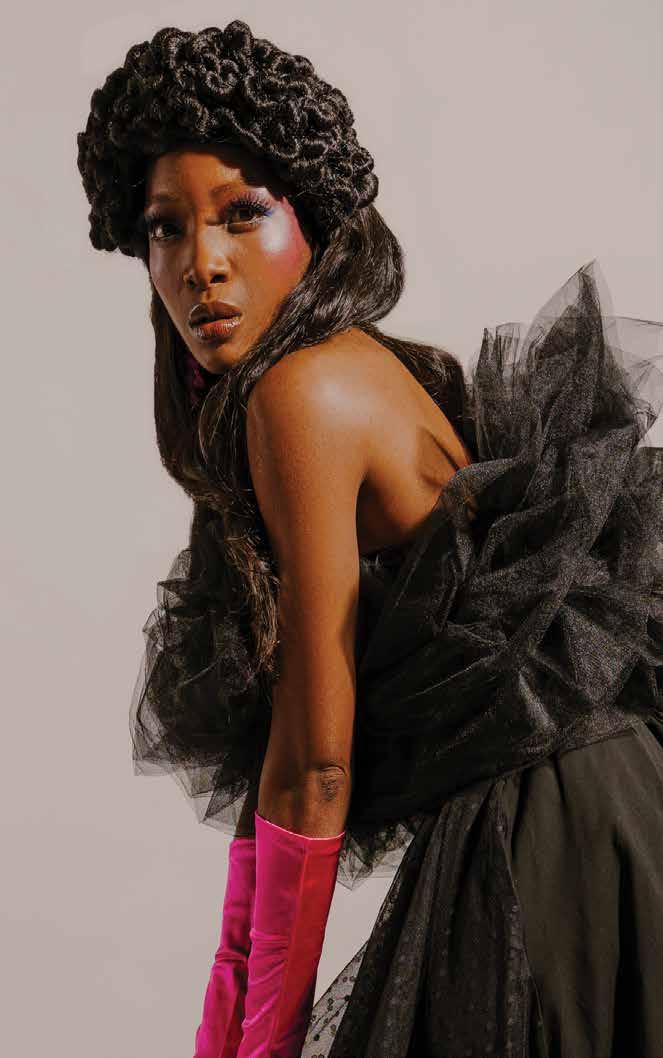

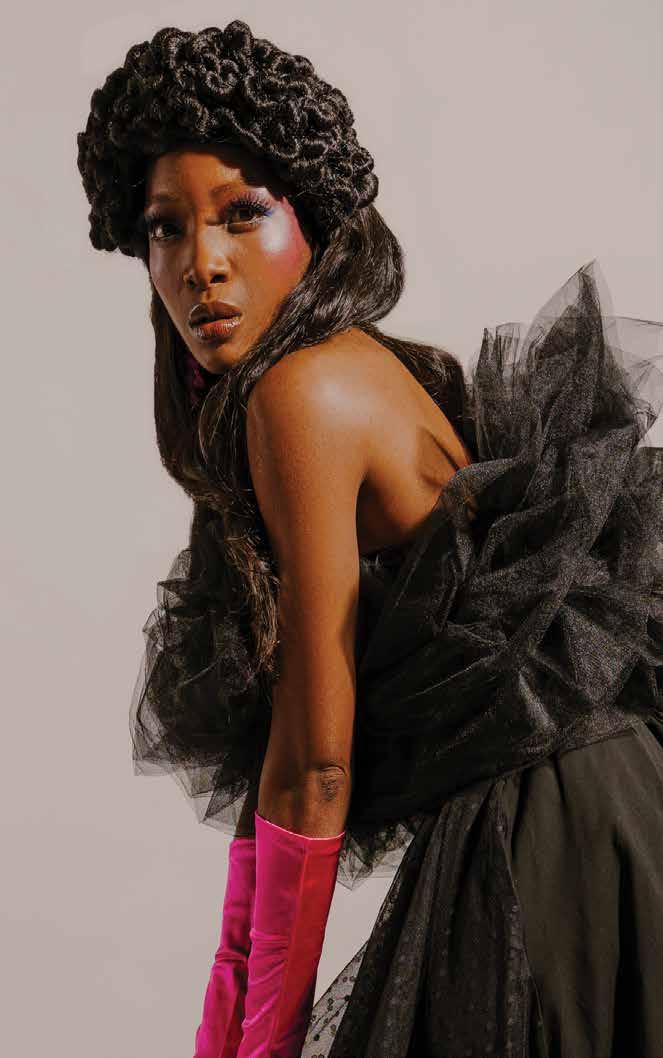

ON THE COVER Angelina (Heyman Talent Agency)

Photography by Polina Osherov

Style by Laura Walters for Style Riot

Makeup by Jon Gregory and India Hall (Aesthetic Artist Agency)

Assisted by Alexa Carr

ON THIS PAGE

Joey Rose (Heyman Talent Agency)

Photography by Polina Osherov

Assisted by Esther Boston

Style by Laura Walters for Style Riot

Makeup by Kimberly Harris (Aesthetic Artist Agency)

Hair by Philip Salmon

Production Assistants Anne Laker and Jenny Walton

Crown, Vintage

Dress, Jill Sander

Bodysuit, Zara

Neon Yellow Stiletto, Elisabet Tang

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 6

7 Indy’s only cut & sew facility stitchworksindy.com @stitchworksindy

WHAT IS ONE OF YOURPROUDEST MOMENTS? CLINT KEARNEY

Clintisaphotographerwhocurrently residesinIndianapolis.Hefinds passioninhisworkbyliftingup individualsandsharingwhathe learnsaboutthemthroughvisual storytelling.Heisexcitedtocreate moreeachdayandspreadthelove. Ahandfulofyearsago,Iwas blessedtohaveapieceofwork publishedintheKurtVonnegut Museumliteraryjournal.

www.clintkearney.com

@hellohoosier

PHILIP BARCIO

Myriam Nicodemus is a self taught photographer and filmmaker based in South Bend, Indiana. She began her career as a photojournalist while stationed in Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri as a military spouse and started her own photography and videography business while stationed overseas in Germany. She is originally from Guatemala and believes her love of photography and cinema came from a longing to fit in as a newly implanted immigrant in America. She is also the Founder and Executive Director of EM EN. EM EN empowers artists to create for a living by reducing barriers to that dream by addressing issues including access to space, knowledge capital, and tools that are necessary to elevate an artist’s practice to a full-time and professional level so that they can become full time artists.

MYRIAM NICODEMUS

Phillip Barcio is an author, journalist, art historian, radio host, filmmaker, public speaker, plant-based Neapolitan pizza expert, cocktail aficionado, hyper-competitive amateur bowler, social media skeptic, degrowth proponent, animal protector, maker of antiracist choices, and member of the executive team at Kavi Gupta gallery in Chicago. His writing has been published in dozens of publications, including Hyperallergic, Tikkun, Momus, New Art Examiner, PATTERN, Western Humanities Review, and MichiganQuarterlyReview,amongmany others.Heholdsadegreeinfilmmaking from Vancouver Film School, and degreesinTheaterandPhotojournalism fromBallStateUniversity. One of my proudest moments occurred when I was 8 years old and some adult asked me directions how to get somewhere. I told them. Then later on they came back around and let me know my directions were right. I wasn’t surprised of course. But they said they were impressed that a little kid knew the city so well. It felt good for once to have an adult acknowledge that my brain worked just fine. I never forget that experience whenever I’m around kids. They’re more aware of what’s going on than it seems.

philbarcio.com

Starting EM EN because of my son and creatives like him. Everytime we get to meet and work with a new creative artist through EM EN, I feel incredibly grateful and proud that this exists now and that people are participating and building a community alongside us.

myriamnicodemus.com @mnphotofilm

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 8 CONTRIBUTORS

IRIS WILLIAMSON

DYLAN LEEHODGES

Dylan

is

Over

he has contributed to the local shopping and fashion coverage for the magazine’s lifestyle section. He previously interned for PATTERN magazine, and worked at its former companion store on Mass Ave. One of my proudest moments was when I overcame my fear of public speaking to join a panelist discussion at the Indiana Fashion Foundation’s 2021 Making it IN Fashion industry conference where I talked about how my work intersects with the fashion industry.

@dyllhodg

Iris Williamson is a curator, arts upadministrator,andartistwhogrew regularlyontheFloridacoast,whereshe encounteredbothalligators and shuttle launches from her backwindow.Shecurrentlydirectsand curatesNewHarmonyGalleryofContemporaryArt,Universityof Southern Indiana and is 2021-2022 ofCurator-in-ResidenceatUniversity WilliamsonOregon’sCenterforArtResearch. co-founded HOLDING ORContemporary,agalleryinPortland, with an alternative business modelthatexaminestheprivilegeoftheArt World. Her curatorial research centers around how labor, economics, and the built environment affects individuals and communities. I’mveryproudofthegalleryI Inco-founded,HOLDINGContemporary. subsidizedlate2016,Iwasgiftedaspaceata ratetostartachallenging PearlexhibitionspaceinPortland,Oregon’s Arts District. While it was a wonderfulopportunity,itwasstill debtfinanciallybeyondreach(Istillhad frompreviousartist-runspaces).Afterresearchingdifferentgallery models within the art world as well as broader business structures outsideoftheartworld,nothingseemed feasible until we arrived at the conceptofaShareholderProgram. theConceptuallyapplyingthemodelof financial stock market to the art theworld,HOLDINGContemporaryoffers $100/eachpublic“shares”ofthegalleryfor asawaytosupportan whoemergingartsspace.Shareholders, lovers,areartists,professors,art-friends,andsupportersfrom aroundtheworld,receivefinancialandstatements,votingopportunities, dividends based on sales. TheShareholderprogramhasallowed HOLDINGContemporarytosupport whilecontemporaryartists’artandideas privilege,confrontingideasofpower,andaccessintheArtWorldofforfiveyears.Iamincrediblyproud artiststhisprojectandthankfulforthe and individuals I’ve been able to work with.

@nhgca

@holdingcontemporary

TABITHABARBOUR

TabithaBarbourisacreative entrepreneurinIndianapolis.Shehas avarietyofpassionsincludingevent management,culinaryarts,writing, fashionandbeauty,andvlogging.

Tabithagraduatedwithhonorsfrom ButlerUniversityin2017,whereshe earnedadegreeinEnglishwithminors inGender,Women,andSexuality StudiesandPoliticalScience. I’mproudtohaveplannedand executedtheIndyPrideVirtual Festival2020and2021.

@tabithabarbour

9

Lee Hodges

the digital editor at Indianapolis Monthly.

the years,

PHOTOGRAPHY BY POLINA OSHEROV

ASSISTED BY ALEXA CARR

STYLE BY LAURA WALTERS FOR STYLE RIOT

MAKEUP BY JON GREGORY AND INDIA HALL (AESTHETIC ARTIST AGENCY)

MODELS: NEGUS & ANGELINA (HEYMAN TALENT)

DESIGN BY CARRIE KELB

PHOTOGRAPHY BY POLINA OSHEROV

ASSISTED BY ALEXA CARR

STYLE BY LAURA WALTERS FOR STYLE RIOT

MAKEUP BY JON GREGORY AND INDIA HALL (AESTHETIC ARTIST AGENCY)

MODELS: NEGUS & ANGELINA (HEYMAN TALENT)

DESIGN BY CARRIE KELB

PATTERN 12

15

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 16

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 18

KELVIN BURZON. ARTIST. DESIGNER.

Kelvin Burzon is a Filipino-American artist whose work explores the intersection of sexuality, race, gender, and religion. In his recent series of work, members of the queer community, found on the gay dating app Grindr, pose as figures from traditional Catholic imagery.

DYLAN LEE HODGES: How would you define pride?

KELVIN BURZON: Pride, for me, is more internal than a public understanding of what pride means. When I say internal, I mean that it’s more personal and should be defined per person. It’s easy to fall for Pride month and what it means to be a prideful queer. It’s part of our culture to be campy and to don our rainbows and all these things, but not all queer people are like that. And so, I kind of want to change that definition of pride to something that is going to be personal for each person. So, pride for me means the instances and the moments that I found comfort in myself, accepting who I am, and then trying to follow in those footsteps eventually.

DLH: Was it easy to find your footing and put your work out to the world?

KB: Absolutely not. I found all kinds of ways to avoid talking about it. Like, I would make [work] that had absolutely nothing to do with me, that I didn’t have any interest in, honing in on skills that had nothing to do with the work that I should be making. [I’d do that] just to avoid the subject matter and just to avoid having to communicate it to the world. And I wasn’t prideful then. There was no way I was going to wear a rainbow flag tank top. My work was what helped me develop this pride, this pridefulness, this acceptance. It wasn’t until I was able to make this work, and tell the world about who I am, that I developed into my full-grown identity.

DLH: Have you faced any challenges being an artist?

KB: It was a challenge to get over the initial shock of my work. That was the biggest thing. I tell my students to make work about what keeps them up at night. I avoided that for so long. I knew exactly what I should be doing. It was just the block of my upbring and religion. All these

external influences I knew really had nothing to do with me. It was challenging accepting that and moving on with what I was supposed to be doing in the first place. Since then, there hasn’t really been any issue with making work. It’s endless inspiration for me: religion and the queer community. The stories that are there are ongoing.

DLH: RuPaul’s Drag Race contestant Silky Nutmeg Ganache features a lot in your artwork. For instance, she’s seen as Mary Magdalene in Noli Me Tangere. How did you meet?

KB: She is a friend that I’ve known since college. I was getting my graduate degree at Wabash College when we met. That’s when Silky began doing drag. I’ve watched her drag career go from us driving to Evansville making a gown from Walmart fabric to us being on VH1. I’ve made multiple looks during her times on Drag Race.

DLH: Do you make custom-order gowns?

KB: I do, but it’s not a thing that I advertise. It’s not my profession, it’s a passion. If it was something that I had to do from this hour to this hour, then I’d lose interest. And fashion has always been an escape from the things that I had to do. I fell into it because I’ve always been around garment construction. When I was young, in the Philippines, we would get custom pajamas made by a neighbor. Our Catholic school uniforms were customdone by somebody nearby. I have a grandma who’s a seamstress that does alterations. Within the past six years, I really fell into doing more research about pattern making and actual construction methods. I started transitioning my closet out of bought clothing and started making my own clothes. Then really it was the queer community. It was drag that brought me into this level of costume design.

DLH: How did you manage to use Grindr to find people willing to pose for you?

KB: I got game! (laughs) Seriously though, people want to be photographed. People want to be a part of art. If you say, ‘I’m an artist and a photographer, and I would like to

have you in my studio,’ people are flattered by that.

DLH: Is there a medium you haven’t tried but would like to explore?

KB: I wish I did more technical production stuff like weaving, metal stripping, or jewelry making. I’m lacking experience in it and it’s harder to research and learn.

DLH: Do you feel boxed into religious works?

KB: No, these religious works are just what I fell into. I love [them], and I will probably keep going, but [they’re] not who I am. There are other pieces that I am working on at the same time that look completely different, which is why I don’t feel boxed.

DLH: What other imagery excites you?

KB: My next project, which I have been looking forward to for a long time, is making more textile-based work that explores my identity as a Filipino outside of colonialism. I am doing that through textiles and researching garments and clothing from before the Spanish rule in the Philippines. I’m really interested in the transition between how people dressed in the Philippines and what happened when religion came along making fabric out of pineapples.

DLH: What kind of impact do you want your artistry to make?

KB: I was giving a presentation of my religious and queer work at a national convention for photography. This young queer came up to me and asked, ‘How do I come out to my parents?’ I didn’t answer, because there is no direct answer to that question. But that kind of puts me in a space where my work stands for people, what it can do for people, and what kind of conversations can root out of it. That’s what I want for my art, to keep creating the space for these discussions. ✂

IG @kburzon

19

WORDS BY DYLAN LEE HODGES + PHOTOGRAPH BY ESTHER BOSTON

PRESSING ON

Pressing On is a great window into a technique of design you have to love in order to pursue these days. I love the texture in this film. The location and the actual process itself looks very striking on the screen. The filmmakers do a great job of making you want to reach in and get your hand dirty!

-TYSON COCKS

“YET ANOTHER STREAMING SERVICE—WHY?”

That’s the initial and understandable reaction to Hoodox, the first streaming service to exclusively feature nonfiction content focused on Indiana. It’s short for “Hoosier Documentaries,” and, just like a great documentary, the logic behind Hoodox draws you in quickly—and keeps you engaged as you learn more.

“There’s this metaphorical chasm,” explains Rocky Walls, the organization’s executive director and part of the all-volunteer team behind the not-for-profit. “On one side, you have talented filmmakers, putting forth their own blood, sweat, and tears—and often their own money—to tell a story they think is really, really important.” These stories, he points out, frequently explore issues like racial justice, environmental risks, or overlooked episodes in our history.

“And on the other side,” he continues, “There are all these people in Indiana who would actually love to watch something created locally, by someone who’s invested in the community.” Hoodox serves those of us, Walls theorizes, who have already committed themselves to shopping and dining and are ready, whether we realize it yet or not, to enjoy the benefits of watching local, too.

For $10 per month, or $100 per year, watching local is now a relatively easy thing to do. Which isn’t to say everyone’s going to cancel Netflix, Hulu, and their ilk and start streaming Hoodox exclusively. Even Walls doesn’t expect that; nor do any of the dozen other people on the Hoodox board of directors, which includes filmmakers, executives, and community luminaries from operations including Kan-Kan Cinema & Brasserie, Indy Film Fest, Heartland Film, and the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis.

Rather, Hoodox is meant as a carefully curated supplementary option. Living, as we do, in a world where anybody with a phone can now call themselves a filmmaker with varying results, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the onslaught of new stuff to watch. It’s also easy to realize that, just by virtue of sheer volume, there’s bound to be more worthwhile work out there than ever before. All we need is a good way to find it. That’s why it’s so useful to see a service with which, as Walls says, “You can feel right away the sense that somebody has really done a good job putting together a certain collection. And they’ve been clear about what you're going to get, and they’re delivering on those expectations honestly.”

WHEN WE WERE SYRIAN

When We Were Syrian is this wonderful exploration of the filmmaker’s family history. He narrates the film in a very authentic and enjoyable way and invites you along for the ride as he pieces together the story of how his family came to be where they are today.

-GRANT MICHAEL

-GRANT MICHAEL

It sounds like a humble goal when you put it like that, but the artistry on display in the films of the Hoodox collection—which gets updated regularly—is far from humble. You might choose to dive into an hour-long visit with the proprietor of an urban lumber company. Or a study of the environmental conditions affecting the White River and the young people working to improve the health of this waterway. Or a 16-minute love note to the iconic Chatterbox Jazz Club. Or a penetrating look at America’s need to define Blackness through the eyes, and in the words, of five fascinating people. There’s a lot there.

All of it helps bridge that gap between inspired filmmakers and curious local audiences. What’s more, it all gives voice and visibility to Hoosiers with a gift for truly listening to others’ stories trusting in their power to inspire us—on both sides of the screen. ✂

21

polina OSHEROV

THE SUPPER CLUB

Food biases aside, since 9th Street Bistro is truly one of my favorite restaurants, The Supper Club artfully tells a story we all probably think we know—passionate restaurant owners fighting to survive during the COVID-19 pandemic—but seeing and hearing the story in this short documentary reveals so much more emotion and raises the stakes that much more. The film is a solid reminder of how valuable our incredible local food businesses really are.

-ROCKY WALLS

NO LIMITS: ACCESS FOR ALL

One of the best things about documentaries is that they provide a space to hear from unheard voices. No Limits takes you into the lives and experiences of teens with visual impairments. Your heart will burst at the pride and effort that these teens put into raising awareness for accessibility, specifically within the walls of the Eiteljorg Museum.

-LORI BYRD-MCDEVITT

IMBPREZ

Being in my first full year as a full-time artist, the documentary is what I needed. It was hope! Brian is proof that artists can have a positive impact in the community. He is empowering artists like myself to stand up and share our voices to make a difference. This documentary is a perfect example of why following your dreams and passions are important.

-TORRIE HUDSON

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 22

BLACK UNSCRIPTED

In a world that wants to define the Black community's experience, Rachel Hardy's film highlights five individuals standing their own identity. Black Unscripted speaks to how we define ourselves comes from within and standing up to the external labels assigned to us. It is brave storytelling with characters stepping into the light authentically themselves.

-KATELYN CALHOUN

-KATELYN CALHOUN

LAST MAN FISHING

Documentaries are best, I believe, at telling personal, human stories, and Last Man Fishing does just that. The story is familiar—big industry using their money and power to bend the rules to benefit them, leaving the little guy in the dust—but this was about a topic I wasn't familiar with. While I don't eat a ton of fish in the Midwest, since watching this film, I have made more conscious decisions about where I buy fish. Motivating viewers to take a specific, positive action is one of the best accomplishments a documentary can have in my opinion.

-ZACH DOWNS

MORE THAN CORN

In the age of industrial agriculture, Genesis and Eli work non-stop to live out their passion for locally grown goods, wholly separate from commercially and federally incentivized crop production. The job is tough, the conditions are dirty, but the people are real and the produce is the star of the show. Documentaries like More Than Corn challenge us to reach outside what makes us comfortable (both on the screen and in our wallets) and that’s what great storytelling should be about. I hope we get another season.

-JARRED JUETT

SNAG IN THE PLAN

Katelyn Calhoun is making very important nature documentaries about local wildlife that casual Hoosiers may know nothing about. Snag in the Plan explores the importance of protecting our forests, but more importantly, what inside those forests we are protecting. This film is exactly why Hoodox should exist: educating Hoosiers (and beyond) about their own backyard with heartfelt and impassioned storytelling.

-DANIEL A JACOBSON

-DANIEL A JACOBSON

FINDING HYGGE

At a time when life has been changed for so will make you question what matters most in yours. This film does a great job of telling the story without the creators making you think that its their opinion. They cover all angles and leave enough space for you to determine what the ultimate lessons are and how to apply them best to your own life. After the first time I screened this in person, I made the 40-minute drive home without the radio on. This purposeful act was brought about by the film causing me to evaluate how I can be more present in a time when our attention is being pulled in so many directions.

-CHRIS THEISEN

25

JON GREGOR Y

MAKEUP AR TI ST HAIR S TYLI ST &&

WORDS BY ALEXA CARR A CONVERSATION WITH DANI OGLESB Y

DESIGN BY CARRIE KELB WORDS BY ALEXA CARR A CONVERSATION WITH

DD D D

Dani Oglesby and Jon Gregory are Indianapolisbased hair and makeup artists, respectively, with influence spanning all over the country. They have collaborated on shoots from editorials to bridal parties—and now they are launching BaeBar, a blowout bar and salon team, dedicated to catering to everyone. Read more about their collaborative process, ideas for Indianapolis’s creative sector, and their personal goals and aspirations.

ALEXA CARR: I understand—and have seen first-hand— how well you collaborate together. How many projects have you worked on together?

Dani Oglesby: I can't even count, because whenever I do a creative hair shoot, nobody can do makeup but Jon; I would trust Jon with my life and my career. I know that no matter what I put in front of him, I know he's going to execute it beautifully. We have the same mindset, morals, and values. He's become one of my best friends. I know it’s been more than ten shoots, because of the photos. But I’m not sure specifically, it's been a lot.

AC: How did this continued collaboration come to be?

Jon Gregory: We met at a free outdoor shoot set up through our agency for our portfolios. This was our first publication together actually now that I think of it. After that shoot, Dani and I ended up working on a styled wedding shoot, and I walked away from that shoot with a best friend. I feel so honored that she trusts my work to be featured alongside hers.

AC: That's amazing, and even more impressive to see how many projects you’ve worked on in such a short time. Dani, what's your favorite part about collaborating on shoots with Jon?

DO: It’s easy. He's not just good, he also centers me. I feel like we have the same energy. I would say, in our industry, there are not a lot of people that are okay with collaborating and giving everyone love and recognition, but we truly complement each other.

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 28

29

ABOVE PHOTOGRAPH BY JACOB MORAN

STYLE BY RAEMIA HIGGINS MODEL JANAY WATSON, 10 MANAGEMENT

LEFT PHOTOGRAPH BY JEANIE STEHR

STYLE BY SARIAH BOROM MODEL CIARA F, 10 MANAGEMENT

OPENING PAGE

PHOTOGRAPH BY REGGIE WHITTAKER MODEL RHIAN, RUNE MODELS

AC: Jon, what has been your favorite collaboration shoot together so far?

JG: My favorite collaboration with Dani has to be our Shuba Magazine submission. This was a collaboration with Callie Zimmerman, Sariah Borom, Chrison Wilson with LModelz, Dani and me. We shot at Healer—which is an incredible location here in Indy. It offers many different styled sets to shoot in and is full of work from local artists This collaboration really showed how well Dani and I can work together. No one in Indy was doing what Dani was doing and that was truly what drew me in. I’ve held on for dear life ever since.

AC: It's incredible to hear about the level of support that you both clearly have for each other. Tell me about creative hair/makeup shoots and your inspirations for them. DO: The first creative hair shoot I did was the summer of 2020. I don't feel like many people are taking the risk that we're taking on, and I feel like we're changing things. I feel like we're setting the standard for a photographer or hairstylist or makeup artist who probably aren't shooting everybody. As far as inspiration, this might sound crazy, but nine times out of ten, I don't know what I'm going to do when I get to a shoot. I have a general plan in my head, but as far as executing it—especially with the creative hairstyles— until I see a model's face or have my hands in their hair, I really don't know what's possible.

JG: I draw inspiration from my life and things that I see day to day in this job. I don't really necessarily like to draw from fashion magazines because that's already been done. I want to do something that's my own signature. I love putting a new spin on things from my experience and playing with color in new ways.

AC: Dani, I understand that you’ve recently launched BaeBar, and Jon is on the team as well—tell me about this and what you hope to accomplish?

DO: I want to change the industry. I worked at DryBar before, and I was the only person that could take care of Black clients. And I felt like if you're going to put Black women or a woman with textured hair on the brochure, you need to be able to accommodate those types of clients. So I want to create an environment where the people on my team are comfortable putting their hands on all hair textures because cosmetology schools don't teach that. I just want to create an inclusive business, so when you see the Bae’s name, no matter what you look like, no matter your hair texture, no matter what your bridal party looks like, you’ll know we can take care of you and you're going to be comfortable.

JG: I'm going to be putting my heart and soul into that and building the team. We have so many plans and ideas for it, and I'm so excited to see where that goes in the next five, ten years. It's so much different from what is in any industry in the United States; we're trying to show people that this is needed, and it's going to happen here in Indianapolis.

AC: That's so important, and I'm glad that Indianapolis is going to have something like that. Do you have a dream project, whether it be a celebrity or brand that you'd love to work with one day?

JG: I've always said if I do Kacey Musgraves’ makeup, I can retire happily, and I will never have to make a brush ever again. So, if I can do Kacey Musgraves’ makeup, that would be my number one.

DO: I haven't told anybody this year, but when I was in Los Angeles, I got to work with Issa Rae, and I signed with her agency. Issa Rae started an agency specifically for Black women who are celebrities to have hair stylists who are comfortable working with their hair type. But throughout the whole collaboration, I couldn't believe I was in the room with them. To fully answer the question—I would love to do Beyoncé's hair. My daughter would think I'm the most amazing person in the world if I did Beyoncé’s hair.

AC: Finally, what lessons have you learned about Indianapolis’s creative sector and navigating it?

JG: We're all together, and there's no competition. The only competition that we have here is against ourselves, and there's a space for us all here. We all bring something different to the table.

DO: Yeah, there are a lot of talented people in the community. You have to be willing to collaborate and work together, because we all win when a shoot gets published or somebody gets signed. People are going to want to know who took that picture, who did the makeup, who the model was, and what agency they are a part of. ✂

Dani Oglesby

IG @dolled_by_dani Agency

Texture Management

The Rock Artists

Jon Gregory IG @jongregorymakeup Agency

Aesthetic Artist Agency

The Rock Artists

BaeBar

IG @baebarindy

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 30

PHOTOGRAPH BY ROCK CANDY PHOTO MODEL DENISE, LMODELZ

REVVINGUP

“Everyone has a story about the Indianapolis 500. Everywhere I go, not just in this city but all over the country, people come up to me and tell me their Indy 500 stories. I love it,” Joe Hale, President of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, shares this sentiment fondly. Hale and his team at the museum welcome over 100,000 guests annually from all over the world.

“It’s not unusual to walk through the galleries and see multi-generational families looking at one car next to some visitors from another country studying a different one,” says Hale. “You may have one person recounting how they saw a particular car or driver win the race, while a child asks why the wheels are so big.”

But Hale and his team are determined to grow and enhance the museum to appeal to new and repeat visitors. The museum sat static in previous years and had one or two rotating exhibitions. However, Hale, who joined the Museum in January 2021, and Jason Vansickle, recently named Vice President of Curation and Education in January, are already making changes.

Under Vansickle’s lead, the exhibition and restoration teams have opened three unique exhibitions this year; three more are planned within the next twelve months.

“We aren’t just trying to do more,” says Vansickle. “We are intentionally trying to do exhibitions that are not just focused on a car or driver, but on the culture of racing and what it means to Indianapolis.”

Vansickle and his team have approached this challenge from a creative and resourceful angle. For “Traditions,” an exhibition that digs deeper into the celebrations and traditions around the Indy 500, the exhibition team combed through historic photos and video footage, piecing storytelling elements together. The exhibition incorporates everything from fashion to music and, of course, milk. As you walk through the space, you see guests pointing and recounting their own stories to one another.

“IN-Focus: The Stories of IMS Photo” is a photography exhibition spotlighting the work of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Photo Team. Bright, bold images contrasting against simple white walls transport you to these moments frozen in time. The show came from a brainstorming session by the exhibition development team.

“We work with IMS Photo every day on different projects. You’ll find their work throughout the entire museum. When we were thinking of creative ways to incorporate more storytelling exhibitions about the history and the iconic moments at the track, we were looking through photographs as a part of our research. Then we realized these images were so stunning and emotional; they were the story. Let’s have them be the showcase.”

The response to these exhibitions has been just what Hale was hoping for. “Sure, our numbers are up, but what pleases me is the stream of positive feedback we have from members and guests. And it makes me so excited for what else we have planned.”

“Roadsters 2 Records: The Twelve Years that Revolutionized the Indianapolis 500” opened this spring (the third exhibition if you are keeping track) and is a more traditional, car-focused show based on the evolution of racing between 1960-72. It incorporates highlights from pop culture and historical moments to help guests connect with the story at hand.

Next is an exhibition titled “Sleek: The Art of the Helmet.” Desiring to incorporate an artist’s perspective for this show, Vansickle reached out to Amiah Mims, a local artist and creative, to serve as guest curator and graphic designer for the exhibition. The exhibition features a combination of historic helmets, modern driver helmets, and new helmets commissioned by artists selected by a committee that included Mims. Artists are asked to design a helmet representing them, similar to how drivers put their personal touches on their helmets.

The museum has two more exhibitions to come. How many times have we all thought, “What if?” “Second” explores the drivers who came close to the victory podium but never entirely made it. In early 2023, the fashion of the Indy 500 will take center stage. Over 100 years old, the race has seen some notable fashion trends.

If Hale’s goal was to enhance the visitor experience and walk away with an understanding of the importance of the Indy 500 and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, his team has creatively stepped up to the challenge. From increasing exhibitions, showcasing the collection in a unique medium, and extending an invitation to visitors to our city, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum is a destination for all.

“There is such pride for what the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the Indianapolis 500 have brought to our city. I want people to walk through our galleries, spend time in our exhibitions, and gain an understanding of that pride. And I want them to come back again and again.” ✂

33

WORDS BY KARA KOVERT PRAY ILLUSTRATION BY CARRIE KELB

INDIANAPOLIS MOTOR SPEEDWAY REVAMPS MUSEUM

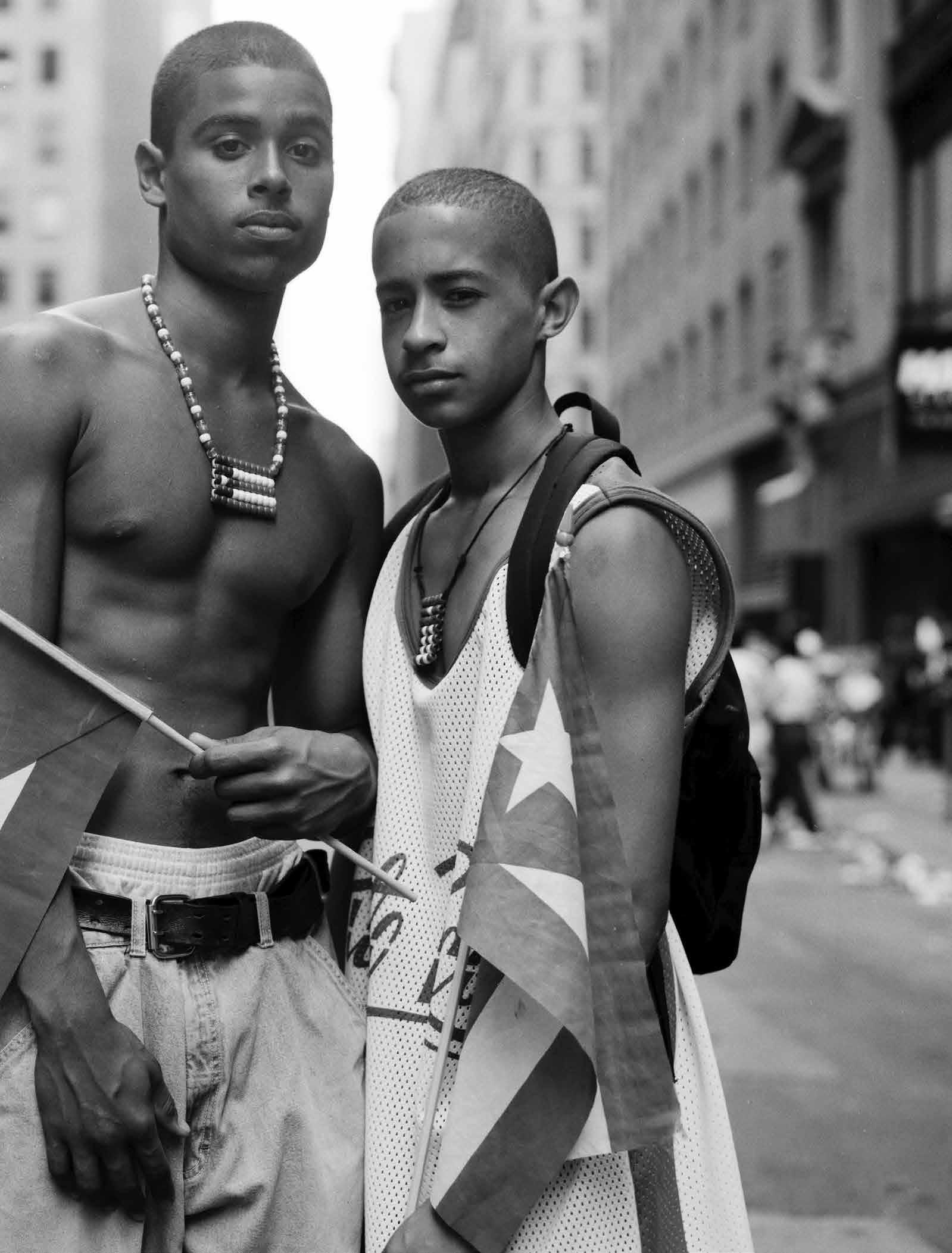

HIT PAR ADE

BE PROUD OF WHO YOU ARE. PARADES ARE ABOUT STANDING UP AND BEING PROUD OF WHO YOU ARE, CELEBRATING IDENTITY, BELIEFS AND COMMUNITY. WHERE YOU CAME FROM AND WHERE YOU ARE AT.

PATTERN

21 34

VOLUME NO.

-JB

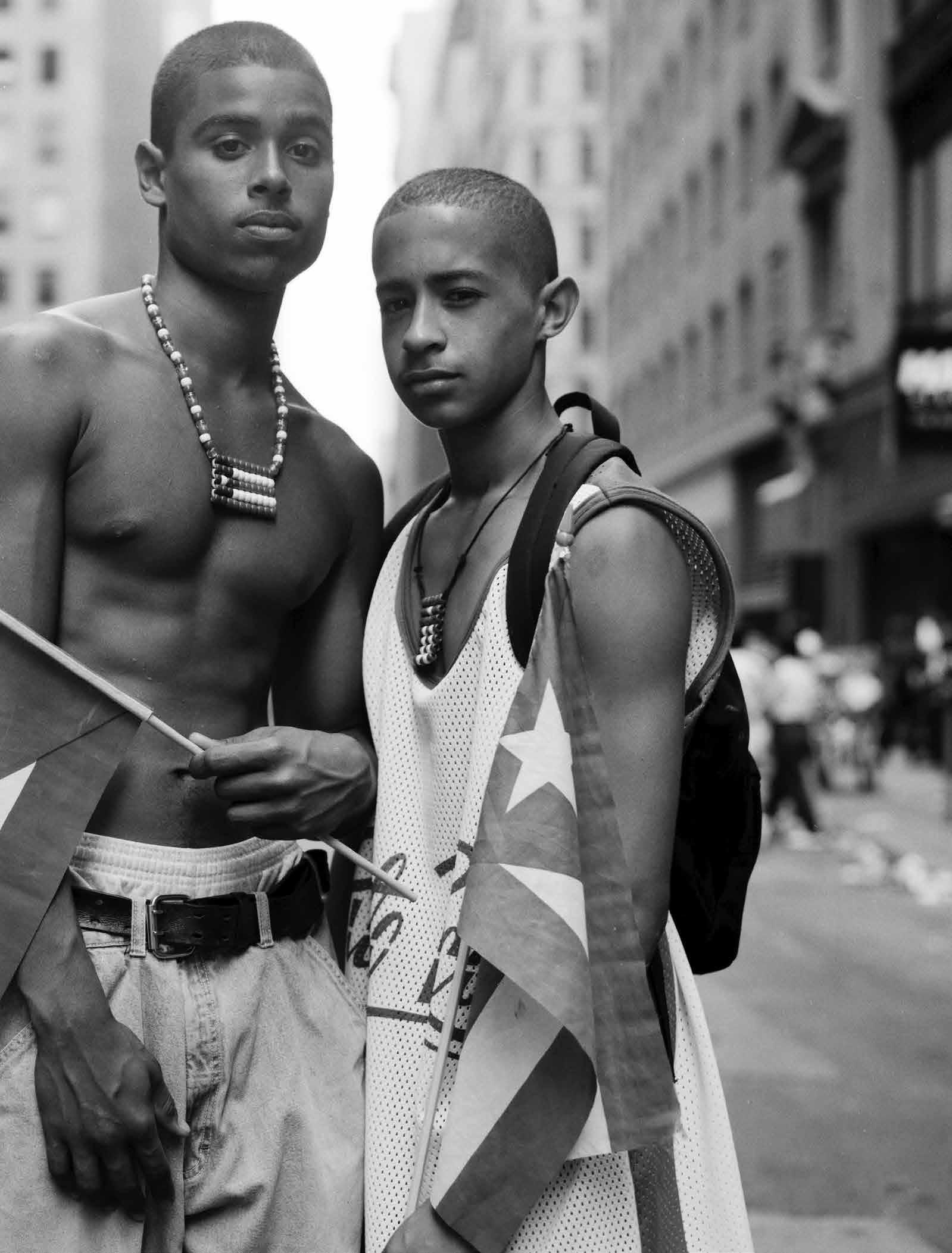

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JANETTE BECKMAN

OPENING PAGE

BROTHERS DANNY AND CARLOS, PUERTO RICAN DAY PARADE, FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY, 1995

ABOVE

IRISH STEP DANCERS, ST PATRICK’S DAY PARADE, NEW YORK CITY, 1995

LEFT

BRONX DRUMMER WITH ST BENEDICT’S FIFE AND DRUM CORPS, ST PATRICK’S DAY PARADE,NEW YORK CITY, 1995

37

VIETNAM VETERAN ON FLOAT, LABOR DAY PARADE, OMAHA, NEBRASKA, 2014

VIETNAM VETERAN ON FLOAT, LABOR DAY PARADE, OMAHA, NEBRASKA, 2014

ABOVE CHEERLEADERS, INDY 500 PARADE, INDIANAPOLIS, 2019

LEFT

YANKEE FANS FROM WASHINGTON HEIGHTS, WORLD SERIES VICTORY PARADE THROUGH THE CANYON OF HEROES, NEW YORK CITY, 2009

41

GRANDMOTHER WITH FAN, PUERTO RICAN DAY PARADE, 47TH STREET, NEW YORK CITY, 1997

MEMBERS OF THE PUERTO RICAN SCHWINN CLUB, PUERTO RICAN DAY PARADE, 5TH AVE, NEW YORK CITY, 1995

RIGHT

BELOW

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 44

CHRIS NEWELL. PHOTOGRAPHER.

WORDS BY KATIE FREEMAN + PHOTOGRAPH BY KELSEY MATTHIAS

Photographer Chris Newell has immersed himself in the arts. After playing the saxophone for over a decade, studying theater, and dreaming of becoming a painter, Newell ultimately fell in love with the camera. His creative process is ever-changing, yet consistently guided by his love of playing with shadow and light. Self-expression is central in his work—whether or not he’s actually in a photo—Newell sees himself in the darkness within his high–contrast editing style. He’s had seventy photos featured in Vogue Italia digital, and his Instagram is packed with street photography and portraiture. We wanted to know more about Newell’s photo-taking process, so we had him come into the PATTERN studio to answer a few questions!

KATIE FREEMAN: What does your creative process look like?

CHRISTOPHER: It’s always changing. I start off experimenting with ideas, with physical pieces like markers, paper, and drawing. Other times, I’ll take a photo of something that inspires me and make a digital vision board. Or I’ll print out a photo, change it up, take a photo of that and keep playing with it. Maybe draw on it. A lot of times, I will hold onto ideas for weeks, take a breather from them and then come back just to check if I see them the same way.

KF: I noticed a lot of your photography incorporates black and white. What attracts you to expressing your ideas that way?

CN: When you put something in black and white, it really separates something for what it is into the purest form. Color is like a drug. It’s addicting. When I put something in black and white, if I’m still attracted

to the image, then the idea itself has even more meaning [than] it did in color. Also, it simplifies things.

KF: What draws you to street photography?

CN: I’m drawn to the authenticity of it. Those moments can never be reincarnated into something else. It can be a learning experience too, like when I end up speaking with a complete stranger and something they say changes the scope of my day.

KF: I noticed that with your portraits, you tend to put your subjects right in the middle of the frame? Is there a reason for that?

CN: When I do that, it allows me to focus on everything that I want to capture about them. It gives me a chance to see something in that person I didn’t see before.

KF: Do you draw inspiration from any other photographers’ work?

CN: Probably, but to be honest, I draw more inspiration from musical artists. Between the different people that I value and favor the most— like Pharell Williams and people my grandma likes, like Teddy Pendergrass or Freddie Jackson—I get inspired by how much emotion they invoke.

KF: Your Instagram bio reads “Lost Photography - to the same place that’s ever changing…” What does that mean to you?

CN: “Lost Photography” expresses the idea that our reality changes over time. Even if you keep going back to the same places, nothing’s ever really the same. That applies to anything: places, people,

festivals, even a state of mind.

KF: Can you tell me a bit about the photos that are featured on Vogue Italia digital?

CN: Something I found interesting when I looked back on the collection I have with them is that those particular images say more about me than most of the ones I have on my VSCO or my Instagram.

KF: Do you have any upcoming projects you’re excited about?

CN: I just started a new job, so I’ve been caught up in that. The work environment is completely different from who I am, so I’m still adjusting. I do have a personal project with a local artist who I can’t name yet that I’m very excited about. It’s called ‘Yin.’ There’s a whole meaning behind it that we’re still trying to figure out. It is a mix of instrumental music, video, and poetry. It’ll probably involve some photography too, but won’t be super focused on it, just to mix things up for myself.

KF: What are you most proud of when it comes to your photography?

CN: I think I’m most proud of my work when people say my photos look like paintings. I never saw it that way, and that’s a comment that happens every once in a while. I think that’s cool because I’ve always secretly wanted to be a painter, but I just didn’t have the time or patience for it. ✂

IG @_chrisnewell_

45

BUSINESS PRIVATE SECURITIES

Legal is a boutique law firm, working with clients on a variety of business and real estate matters, including entrepreneurial and venture capital services, buying, selling and leasing real estate, and drafting and negotiating contracts 6219 Guilford Avenue, Indianapolis, Indiana 46220 (317) 643-9910 More information at www.wormserlegal.com

REAL ESTATE Wormser

47 PHOTOGRAPHY BY ERIN SCHUERMAN; NEAR OSGOOD, IN

ARTSIER + GUTSEIR + HOOSIER THAN YOU KNEW

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JONATHAN HILL; NOBLESVILLE, IN

Water

Through sixteen Indiana counties, the White River’s entire watershed occupies 1.7 million acres of land. In Marion and Hamilton Counties alone, the White River traverses fifty-eight miles (106 miles of riverbank), offering 11,000 acres of parks and greenspace. We talk about Indiana as landlocked, but in recent years, community leaders have recognized an opportunity that exists if we just grow our appreciation and connection to this beautiful asset.

BY

49

EXPLORE INDIANA’S WHITE RIVER FOR UNEXPECTED FUN AND ADVENTURE

WORDS

JULIE RHODES

PHOTOGRAPH BY DREW MEEK

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 50

Locked Land

Many are investing time, expertise, and money to make the White River and all the smaller tributaries more hospitable for its wildlife and human inhabitants.

After a century of dumping raw sewage from combined stormwater and sanitary sewer systems, clearing land for development and agriculture, building impervious surfaces, installing exotic trees and plants, and using chemical fertilizers and pesticides, there is a growing movement to transform our waterways into community places of beauty, tranquility, and recreation.

Most recently, news of even more exciting investments are being announced. Here are just a few developments recently completed or underway:

• $9 million investment to restore the crumbling historic Taggart Monument in Riverside Park for live performances from groups like Indy Shakes, the outdoor Shakespeare company

• $30 million golf and entertainment center to open this summer

• $100 million development for Elanco Animal Health Campus that includes expansion of the White River State Park

• $20 million READI grant for an effort called the White River Regional Opportunities Initiative to activate projects in three Indiana counties

In addition, billions in new investment dollars are helping secure Indiana’s drinking water systems, reducing raw sewage and other pollutants, and building opportunities for future generations to better appreciate our waterway assets.

Since 2017, the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust has provided seventeen non-profit organizations with nearly $11 million to increase access to, improve water quality in, advance advocacy for, and increase awareness about the White River watershed. Local companies and foundations like Cummins, Eli Lilly and Company, and Ball Brothers, are also lifting up waterway projects and efforts across Central Indiana and beyond.

• $21 million in trails funding from the federal American Recovery Act dollars for Marion County to enhance or complete trails along waterways like Pogue’s Run and Pleasant Run

• Natural restoration projects underway at major cultural institutions including 100 Acres at Newfields and Conner Prairie

• Repurposing a gravel pit into a public use space at Strawtown Koteewi Park

• Beautiful, cultural, and nature-filled riverfront promenades at Riverside and Broad Ripple parks

• Lilly Endowment funding to create a pop-up park with sunshades and picnic tables, a tech hub, and art gallery at the formerly segregated beach-front area that is now the community-led Belmont Beach Project near 16th Street in Indianapolis

One brand-new resource, DiscoverWhiteRiver.com just launched last month and offers information about the White River, from events happening in adjacent art and music venues, parks or along trails, as well as where to stop for a meal or drink and information on local festivals. The website allows you to take a quiz to help tailor your interests to experiences. What started as an exploration and visioning process in 2018 as part of the White River Vision Plan has evolved into an incredible resource for anyone looking for a day out all year long. Even before the plan, city and civic leaders across Indianapolis launched our collective impact initiative, Reconnecting to Our Waterways (ROW), to engage community members across Marion County to connect, engage, and improve the waterway nearby. These early efforts resulted in community-led improvements working with community partner organizations and opened up views, added resting spots, overlooks, art pieces, and restored natural habitats–efforts that continue to this day. An Exploration & Celebration Guide for locating these hidden gems is available in English and Spanish at: OurWaterways.org/get-involved/explore

No matter where you live in Indiana, you are either within or very near the White River watershed. And whether you are seeking a day hiking, biking, paddling in nature, enjoying a drink or meal overlooking a waterway, there are many opportunities to explore, engage with, and improve the waterways across the state. Plan now for your next adventure! ✂

51

THIS TIME HAS BEEN MARKED FOR BETTER CO-EXISTENCE WITH THE MANY SPECIES, INCLUDING THE HUMAN SPECIES, THAT RELY ON OUR RIVER FOR HEALTH, WELLBEING, AND QUALITY OF LIFE.

No matter where you live in Indiana, you are either within or very near the White River watershed.

Neighborhood

Before dozens of murals colored its walls, fences, and facades, Wabash was just the neighborhood on the other side of the tracks. Active rail lines separated it from downtown Lafayette, Indiana, and left Wabash Avenue as the only way in and out of the neighborhood. Not that people were trying to go to Wabash. The neighborhood had, as they say, a certain reputation. A storied history. There were vacant buildings and rumors of gang activity and you only went there if you knew someone, and they knew you.

53

WORDS BY DAWN OLSEN

PHOTOGRAPHY BY CLINT KEARNEY

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 54

In the fourteen years since Tetia Lee arrived in Lafayette, the city has gotten a lot more vibrant. That’s largely due to Lee herself, who was the assistant director of a northwest Indiana arts organization before stepping into her current role as CEO of The Arts Federation. Based in Lafayette, The Arts Federation serves as the umbrella organization and arts council for fourteen counties in north central Indiana. Places like Benton County, where 92 percent of the population is white according to 2020 census data. Small, one-thousand-person towns where doors go unlocked and gossip runs deep. Rural communities whose population is declining. And neighborhoods with a median household income of $28,000—like Wabash.

“The Wabash neighborhood is right outside downtown, and there’s this incredible retaining wall there on Wabash Avenue,” Lee says. “I was driving around town, looking for blank canvases. When I saw that wall, I knew I wanted to paint it.”

Lee brought the idea to Margy Deverall, a project manager for Lafayette’s Department of Economic Development. Deverall confessed that she too had been thinking about putting a mural there. But the more they talked, the more they realized one mural just wasn’t enough. Not for them or the neighborhood. But a mural festival? Now, that sounded sexy.

Double time to August 2018, when eleven artists arrived in Lafayette for the first Wabash Walls Festival. The artists were from around the world, and some had never heard of Indiana. The ones who had associated the state with two things: race cars and racism.

True, Indiana isn’t diverse. The state remains 77 percent white. With those demographics, it’s easy for outsiders to assume corn isn’t the only thing on the straight and narrow in Indiana. But that’s the thing with stereotyping—it doesn’t encompass Hoosier Hospitality.

“Artists are really surprised by the amount of support from the community,” says Lee. “A lot of them come from big cities and don’t go up and talk to strangers, but these are small towns and small communities that take care of them. Overfeed them. Host them, set up meal trains, offer assistance.” Next-level hospitality, in other words, and a new experience for artists who are used to being dumped at a site and left to their own devices. Need water? Want food? Forgot a tool? You’re on your own. Good luck. Let us know when you’re finished.

Not Lee, though. And not the residents of Wabash or the small towns who welcome something new, something colorful. “The biggest compliment I can get is when artists tell me this is the most professional program they’ve been a part of,” says Lee.

Although the Wabash Walls Festival is only in its fifth year, the mural initiative itself has been in place since 2008. And the artists? They’ve been coming back to Indiana for years. Take Argentina native, Andrés Petroselli, for example. In 2018, Petroselli, known as Cobre, painted the face of a train conductor on south Second Street in Lafayette. (You’ll find it on the Lafayette Sanitation Department building, just before the road goes under the train tracks, past the rainbow-colored Wabash Walls! mural, and turns into Wabash Avenue.) In the summer of 2021, Cobre completed a mural honoring diversity and inclusion inside Purdue University’s Peirce Hall. He also has two murals in Rensselaer, Indiana, whose entire population could cruise together on a Royal Caribbean ship. Cobre is just one of the many artists of color who The Arts Federation has partnered with. They’ve also worked with Japanese-American artist JUURI, whose work is inspired by traditional Japanese art. (She often references Japanese folklore, history, and kabuki plays in her murals.) Nicole Sagar, a Miami-based artist of Latin descent, has painted two pieces on Wabash Avenue, one in small town Covington, Indiana, and one in even-smaller Wolcott, Indiana. El “Chiwi” Vickery, a non-binary artist based in Modesto, California, painted a catfish mural during the 2018 Wabash Walls Festival. And then there’s Mexican-American artist Ms. Yellow, also known as Nuria Ortiz, who painted a peacock mural as vivid as a Lisa Frank Trapper Keeper.

“DEI IS INSTILLED IN THE FABRIC OF THE ARTS FEDERATION,” SAYS LEE. “I LOOK FOR TALENT, BUT IF WE HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY TO WORK WITH A VERY TALENTED ARTIST WHO ALSO HAPPENS TO BE AN ARTIST OF COLOR, ALL THE BETTER. WE ARE VERY INTENTIONAL ABOUT PROVIDING PLATFORMS LIKE THE WABASH WALLS FESTIVAL TO HIGHLIGHT UNDER-REPRESENTED ARTISTS.”

Inviting under-represented artists to under-served rural communities is another way The Arts Federation combats the belief that art is elitist. “People can be intimidated, but public art brings the art to the people,” says Lee. “And if we’re talking about equity, art should be accessible to everyone.”

That includes rural Indiana, whose residents may not be able to afford admission to a museum. Or have the means to travel to the city. But when Korean street artists like Royyal Dog—who paints African-American women in traditional Korean clothing—come in, Hoosier Hospitality comes out. Community members hang at the site and develop personal relationships with the artists. They take artists as their own and create an environment where creativity can flourish. As a result, artists have started to view Indiana as an arts-forward state, a place where two-story sunflower murals are the norm and art has turned towns into cultural destinations and people drive past two hours’ worth of cornfields to Fountain County, where they admire a wall of spray-painted peonies, then order a tenderloin with pickles from a diner across the street. A place where gravel lots become greenspaces, like in Fowler, Indiana, a town of two thousand and where just one piece of art, one mural, reinvigorates the community.

Like in Francesville, a blip of a town one hour north of Lafayette. In the spring of 2021, Brooklyn-based artist Jenna Morello painted a mural of different flowers in various stages of bloom. Lee describes the dedication ceremony as one of the most touching she’s ever attended. “Residents talked about the symbolism of the mural, that all the flowers in different stages of development represented the growth of their town, that they’re still alive. They’re focused on celebrating their assets and not focused on things they don’t have,” says Lee. Lee thinks The Arts Federation’s programs have influenced the number—and the quality—of art in Indiana and beyond. She says she’s fielded phone calls from various communities asking how they can implement their own mural festivals. Just like how art can—and should be—anywhere, so can community pride. In Wabash, the dozens of murals have kindled the economy. Before the first Wabash Walls Festival, the median home price in Wabash was $80,000. Now, homes are valued at $120,000 and up. Can the mural festival claim credit? Yeah, some of it. Because you don’t pass through Wabash anymore; you pause and admire. You get a coffee from Sacred Grounds and walk around, to the peacocks, to the catfish, to the chip factory where Jenna Morello painted the head of a cello and turned an eyesore into art. ✂

55

THE IDEA OF CRUISING DOWN WABASH AVENUE TO SEE THE ART WAS LAUGHABLE. THERE WASN’T MUCH TO SEE, UNLESS YOU COUNTED THE EYESORE THAT RESIDENTS CALLED “THE CHIP FACTORY.” BUT THAT WAS BEFORE.

Legacy

KEARNEY

KEARNEY

LYLES STATION: LOOKING AHEAD TO THE NEXT 200 YEARS

“It all started with a forty-five pound pig,” says Stanley Madison grinning and holding his hand up in the air as if he was presenting his prized pig to my mother and me. Our eyes are wide and mouths agape as we sit in an auditorium in the lower level of the Lyles Station Historic School and Museum in Lyles Station, Indiana. Madison is recalling the story of how he began his journey as a farmer. When he was a young boy, his grandfather gave him a small feeder pig as a way to earn money. “I raised pigs until I was twenty-six years old, starting with that small feeder pig who had more piglets that I raised to full grown to sell at the market.”

TABITHA BARBOUR

BY

WORDS

57

PHOTOGRAPHY BY CLINT

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 58

200 years

Stanley Madison, born and raised in Lyles Station, founded the Lyles Station Historic Preservation Corporation (LSHPC) in 1997. He is the chairman and museum curator at the Lyles Station Historic School and Museum (LSHSM).

MADISON IS PASSIONATE ABOUT INCREASING THE NUMBER OF AFRICAN AMERICAN FARMERS IN THE UNITED STATES. ACCORDING TO AN ARTICLE ON INPUT FORT WAYNE, “SINCE 1920, THE NUMBER OF BLACK FARMERS HAS DECREASED DRASTICALLY FROM ABOUT ONE MILLION TO JUST UNDER 45,000 IN 2021.”

It is a small farming community and is the last remaining and oldest African American settlement in Indiana. It was first settled by Thomas Grier, a freed slave who purchased farm land in Gibson County over 200 years ago. Lyles Station is named after Joshua Lyles, a prominent leader in the settlement community, who “… donated six acres of land, valued at $50 on September 16, 1870, to the Old Airline Railroad, now called the Southern Railroad, on the condition that the company would maintain station in Lyles Station.”

On February 4, Lyles Station celebrated the 100th anniversary of Lyles Station Consolidated School. It was founded in 1922, and Madison remembers when he was a student at Lyles Station Consolidated Schools in the late fifties. When I ask Madison what he’s most proud of when he thinks of Lyles Station he says, “I think the most proud is to know that you are following the legacy from your forefathers and you are continuing that legacy.”

The LSHPC hosted a weekend of events including a documentary screening. The events had around seventy community supporters in attendance. The Lyles Station Consolidated School site is now the LSHSM with a replica heritage classroom, two exhibition rooms with Lyles Station history, and an auditorium.

Speaking of his hopes for Lyles Station over the next hundred years, Madison says, “I am looking at two hundred years down the road because one hundred years is very short and two hundred years is what we need to make Lyles Station a higher education development for the future.”

At the end of the museum tour, Madison shows us a map of the LSHPC site’s future plans, where the board hopes to expand the programmatic offerings and impact. This includes a dining hall and cafeteria, log cabins for overnight field trips, school bus parking, expansion of youth programming, and an agriculture teaching facility for young adults who are interested in learning about farming, business, and research.

Madison laughs, “People think that anyone can become an ol’ dirt farmer.” He continues sternly, “…But the farmer of yesterday is not the farmer of today.” Madison points out that being a farmer today requires you to be a marketer, a manager, a sales person, and to have a good understanding of technology. “I want to build a program that allows young people to have a six-month immersion experience in agriculture to discover if they can see themselves as a farmer or researcher.”

When I ask Madison how people can support Lyles Station, he states, “You can donate to our project via PayPal!” Madison would love to work with Marion County and surrounding area schools to bring students to Lyles Station for farming and Indiana history activities. The LSHPC hosts a variety of activities throughout the year at Lyles Station, including Night at the Museum and Juneteenth Celebration. ✂

59

LYLES STATION IS ONE OF SEVENTEEN HISTORIC AFRICAN AMERICAN SETTLEMENTS IN INDIANA, WHERE FREE BLACKS MOVED FROM THE SOUTH AND PURCHASED LAND TO START A NEW LIFE AFTER ENSLAVEMENT.

is what we need to make Lyles Station a higher education development for the future.

Structure

Located at the southwest tip of Indiana near Evansville on land originally occupied by the Mississippian culture, New Harmony is approximately 2.5 hours drive from Indianapolis, and just over two hours from St. Louis and Louisville. Twice the site of utopian experiments in communitarian living, New Harmony is a town rich in beauty, culture, and history. And it makes the perfect location for people to enjoy moments of respite and reconnect with others through conversations about roles of art, design, and place in society. This spring, Big Car Collaborative brought together more than twenty notable authors, artists, designers, researchers, and philosophers from Indiana and around the world—to look at the role of utopian thinking yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

61 PRIDE IN HOOSIER DESIGN

PHOTOGRAPH BY CLINT KEARNEY

MEANING IN STRUCTURE

THE ART OF DOCEY LEWIS

WORDS BY PHILLIP BARCIO

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JIM WALKER

It’s winter, late-pandemic. I’m in my home office perusing images of handwoven textiles by an artist named Docey Lewis. In her seventies, Lewis stepped away from her successful global textile business to restart the art practice from which she walked away in her twenties.

Glancing away from Lewis’s delightful abstractions to the headlines on my muted TV, I see that a million Americans are now dead from COVID-19; six million dead worldwide; Russian troops are fighting Ukrainian citizens in the streets; and somehow 45 is back on the news, calling some petty dictator a genius. Optimism is in short supply. Yet, turning back to Lewis’s rugged, elegant, geometric compositions, I see something in their patterns and interconnected layers that suggests a beautiful, Bauhausian dream—a better world run on systems designed by artists, not authoritarians.

I’m one of those people—the ones who think abstract art is inherently political, because it opens doors of perception that increase conceptual literacy, or something like that.

Wondering if she is of the same ilk, I give Lewis a call. She is, after all, uniquely qualified to speak about the intersection of politics and abstract art—not only because she’s an abstract artist, but because she’s

descended from the founders of one of America’s earliest Utopian societies: New Harmony, Indiana. ORIGINALLY CALLED NEU HARMONIE, THE CITY WAS ESTABLISHED IN 1814 BY JOHANN GEORG RAPP, LEADER OF AN END-TIMES CULT FROM PENNSYLVANIA. RAPP’S FOLLOWERS BUILT 180 STRUCTURES AND ESTABLISHED A THRIVING ECONOMY. BUT BY 1825, THE SECOND COMING HAVING FAILED TO COME, THEY MOVED ON, SELLING THE TOWN TO A WEALTHY INDUSTRIALIST ROBERT OWEN, LEWIS’S GREAT-GREATGREAT-GRANDFATHER.

Owen attempted to establish a second Utopia in New Harmony, based on the principles of universal education and equality. His sons joined him. One, Richard Owen, was the first President of Purdue University. Another, Robert Dale Owen, was elected to Congress, and introduced the bill establishing the Smithsonian Institution.

Despite their means and influence, the Owen family, like the Rapps before them, saw their Utopia fail. In Robert Dale Owen’s autobiography, he postulated that Americans don't naturally want to work together— particularly those who came to the United States after leaving structures where they were trapped. Like her abstract textiles, Lewis has a tangled relationship to both perspectives—the one that thinks structures can and should be constructed that will foster harmonious relationships, and the one that prioritizes independence.

“For me, Utopia is kind of a squishy word,” Lewis says.

The original Greek ou topos literally means no place. There’s a metaphor there I guess.

“The work I do is about creating structures on which pictures might exist,” she explains.

Doesn’t that relate to everyday life, I ask?

“Every day is a new opportunity to help make other people's lives better,” Lewis says. “So what structures do you put in place to make that happen?”

Lewis returned to her ancestor’s field of Utopian dreams a few years ago. In an art studio above a bakery in downtown New Harmony, haunted by the ghosts of her successes and her losses, she is trying to make peace with her past while literally pulling at the threads of her personal history.

Lewis’s roots in the woven world reach back to age nine, making potholders in the attic of her family home in Northford, Connecticut. Her first real textile training came while in college at Stanford.

“The university had a Jane Goodall Center, and I’d applied to go to the Gombe Stream Reserve over the summer,” Lewis says. “I was in the middle of that application and I met a man. You know, there's always a man hidden away in the story when you’re young. I was very conflicted about whether to go to Africa or stay and have this romance. I chose the romance.”

That summer, Lewis enrolled in a weaving class and learned the basics of working with raw fiber.

“I was hooked,” she says with a laugh.

Next thing she knew, she was on a train crossing Canada solo for the Albion Hills School of Weaving, Spinning and Dying. She spent three months there living on a sheep farm and learning the grass roots of the textile process. Edna Blackburn, who ran the school, brought children with emotional or behavioral disorders to the school and had her students show them the basics of the craft.

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 62

“They found it was a very calming activity,” Lewis says. “I was exposed to this other aspect of the effect of weaving on a human being’s mental health. I saw that it could be a broader thing than just me playing with a loom and making something with it.”

Lewis then headed south in a VW van to the Ganado, Arizona, Navajo reservation where she learned a different kind of spinning and weaving and experienced the Navajo dye process. Meanwhile, back in California, the man for whom she had given up her dreams of Africa was busy building her a studio in a geodesic dome on a forty-acre property in the redwood forest.

“It had been a bootlegger's weekend extravaganza,” Lewis says, “kind of falling apart, but cool.”

In that redwoods retreat she built the loom on which she made her first textile artworks. At her debut exhibition, in a library in Redwood City, a collector invited Lewis to do a large private commission for his home.

“He was a mucky-muck in the corporate world in San Francisco,” Lewis says. “So that led to other opportunities. I ended up with an agent, Bridget O’Hara, who was a character. She’d been a chef on a submarine. She was Irish, her son was gay. I met my first transvestite. I was so naive. I broke out of my New England cocoon. It was the early 70s in San Francisco and I was exposed to a very colorful world.”

Looking back to her experience at Albion Hills, Lewis was always looking for ways to make a concrete difference in people’s lives with her work. Wondering if business had a better chance of making a social impact that art, she decided to start her own line of clothing, made from her own fabric.

She enrolled in the San Francisco Fashion Institute, learning to cut and sew handmade fabric by day, and attended night school to learn accounting—“just enough to understand a balance sheet,” she says.

Lewis’s first patroness in fashion was Doris Khashoggi. Yes, that Khashoggi.

“She had married the brother of Adnan Khashoggi, the arms dealer,” Lewis says.

After her divorce, with her fortune Khashoggi set up retail stores in Palo Alto and San Francisco. Lewis was one of several independent clothing designers she took under her wing.

The success of Lewis’s clothing line inspired her to expand by making fabric to sell to other designers. To do that she needed more weavers, so she put together a business plan and took it around to embassies from countries where there were weavers who needed work. Her timing with the Philippine embassy was perfect. “They were doing a trade mission and they invited me on it,” Lewis says. “March Fong Eu, the Secretary of State of California, headed the tour. Texas Instruments was there looking for overseas production, and little old me with my hand weaving workshop.”

Her second day in Manila, Lewis had breakfast with President Marcos. Soon, she had investors helping her establish a workshop in Baguio.

“Imelda Marcos was one of my best customers,” Lewis says. “She commissioned me to do all the fabrics for the interiors of the summer palace. Kept me busy for years.”

Gradually, Lewis expanded her operations into other countries, including Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Nepal. The list of companies that have sold the products made in her workshops includes Sears, Hallmark, Bergdorf’s, Lord and Taylor, Bloomingdale’s, Macy’s, Henri Bendel, Gumps, Horchow, Neiman Marcus, and Sundance Catalog.

The real payoff for Lewis, however, was mentoring the local female weavers she worked with to become entrepreneurs. She also recalls many difficult decisions along the way, and many tragedies, losing friends and colleagues to earthquakes, volcanoes, and floods.

Regaled by the tale of her journey from a tiny redwood forest studio to the top of a global design empire, I can’t help but ask Lewis why she walked away—and why she chose the soil of her ancestor’s disappointments as the place to revisit her own sidelined dreams.

Her answer:

“Do you know David Brooks, the New York Times columnist? Well, two or three years ago, he started something called the Weave Project. The idea was that our social fabric has come unraveled. Brooks got these dinners going where you would invite your town council member over to dinner and talk about things you have in common, and have a civil conversation and not name call and de-base the other side. So I thought, this is a chance to take that metaphor, reweaving the social fabric, and make it real.”

In addition to trying to heal herself through her art, Lewis is involved in an initiative to bring disadvantaged kids from all around to learn weaving in New Harmony. They’ll take classes and see what it’s like to camp and hike and live in a rural village.

“I’ve got selvedge waste of silk wallpaper from a workshop in Nepal, and stacks of samples and lines of products and yada yada, all gathering dust,” Lewis says. “It’s like an archaeological dig of everything I've ever woven or designed. I thought maybe I could turn it into something—take this detritus, take the stories, take everything, and weave it together and see if I can bring some measure of peace to my own life.”

IT ISN’T UTOPIA, BUT IT’S A GOOD YARN. ✂

63

Docey Lewis’s exhibit opens at Tube Factory artspace’s Jeremy Efroymson Gallery on October 7.

Originally called Neu Harmonie, the city was established in 1814 by Johann Georg Rapp.

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 64

65

Rapp’s followers built 180 structures and established a thriving economy.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY HADLEY “TAD” FRUITS

But by 1825, the second coming having failed to come, they moved on.

WORDS BY IRIS WILLIAMSON PHOTOGRAPH BY CLINT KEARNEY

WORDS BY IRIS WILLIAMSON PHOTOGRAPH BY CLINT KEARNEY

People often speak of New Harmony as a “utopia” with its public art and labyrinths, its mix of early-nineteenth-century and mid-twentieth-century architecture, its quaint art scene, and its Mayberry-esque sensibility. If you’ve been here, you know what they’re talking about. It’s hard to not wonder what’s behind this idealistic veneer, which is what drew me from Portland, Oregon to New Harmony Gallery of Contemporary Art (NHGCA).

FOUNDED NEARLY FIFTY YEARS AGO, NHGCA’S ARTIST-RUN VIBE PERSISTS THOUGH IT WORKS WITH REGIONAL, NATIONAL, AND INTERNATIONAL TALENT. THE GALLERY RECEIVES INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT AS PART OF THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN INDIANA, AND WE PRIORITIZE THREE AUDIENCES: THE LOCAL COMMUNITY IN NEW HARMONY; UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN INDIANA STUDENTS, FACULTY, ALUMNI, AND STAFF; AND VISITING TOURISTS.

Despite this support and the widespread exposure, the gallery itself lives out on its own—it is an in-between space shrouded in the myth and magic of two failed utopian experiments. For good or for bad, I tend to find myself professionally in the in-between. Whether it’s from my natural curiosity or from something I learned from escaping a religious cult, I believe there’s a freedom found in the process of letting go. So this in-betweenness appeals to me.

Since joining NHGCA, we’ve made an effort to work with artists that have stories to tell that are different from what has been seen in the area in the past. Allowing the community to explore the idea that what is utopia for one person can easily be a dystopia for another. At NHGCA we ask our visitors to consider questions such as: What are the stories we tell ourselves? What is this space we occupy? What is sacred here, and to whom? Who belongs here? What happens when we hang on too tight, and what happens when we let go? Listening and questioning can help us see more of ourselves, and we can choose to embrace that process. It’s stronger some days than others, but I sense that I’m living through these questions here in New Harmony myself. ✂

What are the stories we tell ourselves? What is this space we occupy? What is sacred here, and to whom? Who belongs here? What happens when we hang on too tight, and what happens when we let go?

Community

If we’re talking politics, Indiana’s more purple than most folks think. There’s more than blue in Indianapolis, and there’s a whole lot more than red across the state. In every corner and pocket available, Hoosiers are building exceptional communities and creative practices. From the enclave of potters living in Goshen to the unexpectedly large Pride Festival in Spencer, there’s a lot of cool shit going on off the well worn paths of Indiana than many of us might imagine. And Hoosiers are the ones making it happen.

WORDS BY JENNY WALTON

69

PRIDE IN

HOOSIER COMMUNITIES

PATTERN VOLUME NO. 21 70

WORDS BY TERRI PROCOPIO PHOTOGRAPH BY MYRIAM NICODEMUS A POTTERY DESTINATION

Michigan native Sadie Misiuk took over another potter’s studio in Goshen, Indiana, in order to establish herself in the ceramics industry. Recognizing Goshen for its supportive arts community and affordable living, Misiuk, an On-Ramp grant winner, saw the city as the perfect place to grow as an artist. “If you live in Goshen and work hard, you can make it as a potter.” Misiuk says. “I’m proud of my On-Ramp award and winning it helped solidify my feeling of being a Hoosier.’

The Goshen arts community continues to grow with a strong emphasis on local, handmade items and its location serves as an influence for creativity. Potters draw inspiration for their work from the scenery and settings around them. “One artist draws inspiration from the woods he lives in,” Misiuk says.

WORDS BY TERRI PROCOPIO PHOTOGRAPH BY SOPHIE STEWART FROM BLIGHTED TO BOOMING

A thirty-year Marion, Indiana resident, Wendy Puffer of Marion Design Co. saw a different side of the city when she moved downtown. “Marion has struggled with poor self-esteem,” Puffer says. “Parts of the city’s history have tamped it down.”

A mecca for pottery, the last weekend of September marks the annual Michiana Pottery Tour. Ceramic enthusiasts flock to the area to stop at the six-to-eight studios on tour, which creates a boom for the town’s shops and restaurants. “It’s really awesome to see different mediums and artists come into the area,” Misiuk says, “The tour continues to get stronger and stronger each year.” ✂