Acknowledgments

Rosmarie Amacher, Zurich

Kara Braciale, Artist and Educator, Cocoran School of the Arts and Design, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA

Susan Brown, Associate Curator and Acting Head of Textiles at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, USA

Tosca Cariboni, MA Student, Institute of Art History and Museum Studies, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Alessandro Cicco, MA Student, Institute of Art History and Museum Studies, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Caitlin Condell, Associate Curator and Head of the Department of Drawings, Prints, and Graphic Design, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, USA

Lisa Cornali, PhD Student, Institute of Art History and Museum Studies, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Corinna Cotsen, Los Angeles, USA

Shadow Curley, Cotsen Textile Traces Student Research

Assistant, The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Washington, DC, USA

Verena Dengler, artist and author, Vienna, Austria

Alice Gianola, MA Student, Institute of Art History and Museum Studies, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Ursula Graf, entrusted with the processing of the Backhausen Archive, Klosterneuburg, Austria, and PhD Student, Department of Fashion and Styles at the Institute of Art Education, Academy of Fine Arts

Vienna, Austria

Niklaus Manuel Güdel, Director of the Ferdinand Hodler Institute, Delémont

Nathalie Gür, MA Student, Institute of Art History and Museum Studies, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Michelle Jackson-Beckett, Senior Lecturer, University of Applied Arts Vienna, Austria

Lori Kartchner, Curator of Education, The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Washington, DC, USA

Mun Kim, Cotsen Textile Traces Student Research Assistant, The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Washington, DC, USA

Stefanie Kitzberger, Head of the Collection of Fashion and Textiles and Senior Scientist at Collection and Archive, University of Applied Arts Vienna, Austria

Eva Marie Klimpel, PhD Student and Textile Conservator at Collection and Archive, University of Applied Arts Vienna, Austria

Markus Kristan, Curator of the Architectural Collection, Albertina, Vienna, Austria

Monika Mähr, Curator and Vice Director of the Historical and Ethnological Museum, St. Gallen, Switzerland

Chloé Marbehant, MA Student, Institute of Art History and Museum Studies, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Bernadette Reinhold, Director of the Oskar Kokoschka Center and Senior Scientist at Collection and Archive, University of Applied Arts Vienna, Austria

Anne-Katrin Rossberg, Curator of the Metal Collection and Wiener Werkstätte Archive, MAK—Museum of Applied Arts Vienna, Austria

Wolfgang Ruf, Gallerist and Collector of European Textiles and Costumes, Stansstad, Switzerland

Johannes Schweiger, Co–founder at Wiener Times, Vienna, Austria

Janis Staggs, Director of Curatorial and Manager of Publications, Neue Galerie, New York, USA

Lyssa Stapleton, Los Angeles, USA

Lara Steinhäußer, Curator of the Textiles and Carpets Collection, MAK—Museum of Applied Arts

Vienna, Austria

Emilie Thévenoz, MA Student, Institute of Art History and Museum Studies, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Angela Völker, Textile Scholar, Retired Curator of the Textiles and Carpets Collection, MAK—Museum of Applied Arts Vienna, Austria

John Wetenhall, Founding Director of The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Washington, DC, USA

Deborah Ziska, Consultant in Museums Communication, Washington, DC, USA

9

Régine Bonnefoit and Marie-Eve Celio-Scheurer

In keeping with the title Tracing Wiener Werkstätte Textiles: Viennese Textiles from the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, eleven authors trace the history of the world-famous and innovative fabrics designed by the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop, or WW). Their studies focus on aspects such as the origins of textile and fashion design collections and archives in Austria, Switzerland, and the United States; the importance of Eastern European folk art, Japanese stencils, and didactic books on ornament of the late nineteenth century for WW textile patterns; the practical application of WW textiles in fashion, interior design, film, and theater sets; and strategies for conquering new markets in the United States. Three of the contributions provide new insight into the work of previously little-noticed female artists such as Hilda Schmid-Jesser, Maria Likarz-Strauss, and Mizzi Vogl.

The majority of the ten studies were written by curators of major archives or collections of WW objects, such as the MAK—Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna and the University of Applied Arts Vienna; and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, and the Neue Galerie in New York. The impetus for the creation of this book, however, came from an institution that holds one of the largest collections of WW textiles in the United States: the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection (CTTSC) at The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum in Washington, DC. The essays emerged from a three-day colloquium organized in April

Introduction

11

2022 by the CTTSC in collaboration with the Institute of Art History and Museum Studies at the University of Neuchâtel in Switzerland and the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

The authors come from three countries that were significant in the history of WW textiles: Austria, Switzerland, and the United States. Austria played the essential role, as the Vienna Workshop was founded there by Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, and Fritz Waerndorfer as an artists’ and artisans’ collective in 1903. Its primary goals were to create high-quality arts and crafts according to purely artistic criteria, following the example of the British Arts and Crafts movement and the Guild of Handicraft.1

The connection with Switzerland intensified during World War I, which plunged Austria into economic crisis. In order to promote exports and bring urgently needed foreign currency into the country in this difficult situation, the Austrian government urged the WW to establish a subsidiary in neutral Switzerland. This led to the opening in 1917 of a WW store on the Bahnhofstrasse in Zurich, with Dagobert Peche appointed as its director.2

The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918 prompted the WW to open up new markets in the United States. On June 9, 1922, Viennese architect, stage designer, and interior decorator Joseph Urban opened the Wiener Werkstaette of America, located on Fifth Avenue in New York. In a contract dated February 4, 1922, the head office of WW granted Urban “the sole right to sell the products of the arts and crafts department in the United States of America for the parent company in Vienna and Wiener Werkstätte in Zurich.” The contract had the following to say about textile production: “[…] we also expect your support in establishing suitable business contacts for our fashion articles, printed fabrics, laces, etc., etc.”3 Many artisanal objects produced by the WW reached the United States through its short-lived New York branch.4 Between 1917 and 1919, several of the WW fabric patterns were printed in Switzerland and sent to New York to be sold by the Wiener Werkstaette of America.5 In this respect, in the 1920s, Austria, Switzerland, and the United States formed a trade triangle for textiles, as well as for other WW arts and crafts objects. Through the Cotsen Textile Traces Colloquium

12

2022, a research triangle was formed between WW specialists in Austria, Switzerland, and the United States. This volume owes its existence to their lively exchange of knowledge, critical debates, and enthusiasm for the research project.

The upturn in fabric production within the workshop began in 1910 with the establishment of a separate Textile Department, followed a year later by the Fashion Department. The Textile Department was headed by Josef Hoffmann until the WW closed in 1932;6 whereas Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill was responsible for the Fashion Department until 1922, when he decided to leave Vienna for a fresh start in the USA. His goal was to design stylistically appropriate clothing for the owners of houses and interiors furnished by the WW by using textiles from the Textile Department. Both departments quickly developed into the most successful production facilities within the WW.7

In the first section of the book, entitled “Wiener Werkstätte Textiles and Their Archives,” four curators of important collections of textiles and preparatory works on paper for textiles examine the origins and particularities of their extensive holdings: Marie-Eve Celio-Scheurer, Academic Coordinator of the CTTSC in Washington, DC, from 2019 to 2022; Lara Steinhäußer, Curator of the Textiles and Carpets Collection at the MAK, Vienna; and Susan Brown and Caitlin Condell, Associate Curators of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. The resulting synoptic view of three collections allows surprising cross-connections and relationships to emerge.

Both the CTTSC and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum owe the identification and dating of countless pieces to the invaluable expertise of Angela Völker, a pioneer in WW textiles research. Her book Die Stoffe der Wiener Werkstätte 1910–1932 (Textiles of the Wiener Werkstätte), published in German as a catalog of the WW fabrics held at the MAK in 1990, translated into English in 1994 and reissued in 2004, remains an unsurpassed standard work in this field. In her essay, which forms the conclusion of this book, Angela Völker provides an overview of more than half a century of research, personal experience, and exhibition history on the WW and its textiles in particular.

13

In the book’s second section, entitled “Interest in the Patterns in Folk Art in Austria-Hungary,” three authors investigate the importance of Eastern European textiles for WW artists. Rebecca Houze, Professor of Art and Design History at the School of Art and Design at Northern Illinois University, examines the work of Anna Lesznai, a Jewish Hungarian artist and writer from Budapest, who was commissioned by the WW to design fashion articles. In her contribution, Eva Marie Klimpel, Textile Conservator and PhD candidate at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, investigates two groups of traditional textiles from the Fashion and Textiles Collection of her university, which includes many pieces stemming from rural populations in Austria-Hungary. These objects were gathered between 1901 and 1925 by artists Mileva Roller and Rosalia Rothansl, who used them as teaching materials and artistic models at the k. k. Kunstgewerbeschule (Imperial Royal Arts and Crafts School) in Vienna. Therefore, it is not surprising that the manufacturing of students’ works from Rothansl’s class is similar to that of traditional embroideries by the Matyó, a Hungarian ethnic group from the region around Mezőkövesd. Houze and Klimpel both discuss the concept of cultural appropriation, which implies an imbalance of power, in which the appropriating group benefits at the expense of those whose cultural forms have been appropriated.

Bernadette Reinhold, Head of the Oskar Kokoschka Center and a Senior Scientist at the Collection and Archive of the University of Applied Arts Vienna, also traces Eastern European models in her essay on one of the best-known garments of the WW in the Fashion and Textiles Collection of the University of Applied Arts Vienna: a skirt designed by Oskar Kokoschka as a kind of “embroidered love letter” to fellow student Lilith Lang. As Reinhold shows, the outer shape of the skirt and the decoration are reminiscent of peasant skirts with aprons, which Kokoschka repeatedly depicts in his WW postcards.

Rebecca Houze’s and Eva Marie Klimpel’s essays create an appropriate transition to the third section, entitled “Innovative Female Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte.”

The great merit of female textile designers at the WW has already been extensively honored by the exhibition Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte at the MAK in 2021 and the catalog published on

14

that occasion.8 Thanks to Rebecca Houze and Eva Marie Klimpel, this volume presents further insight into the importance of female artists such as Anna Lesznai, Mileva Roller, Leopoldine Guttmann, and Rosalia Rothansl in the field of textile design. Many of the artists who later worked for the WW—such as Camilla Birke, Mela Koehler, Maria Likarz-Strauss, Felice Rix-Ueno, Hilda Schmid-Jesser, Mizzi Vogl, or Vally Wieselthier—began their training with Rothansl.

The third section is dedicated to two female artists of the WW: Hilda Schmid-Jesser and Maria Likarz-Strauss. In her contribution, Janis Staggs, Director of Curatorial and Manager of Publications at Neue Galerie New York, examines the work of Schmid-Jesser, who not only designed textiles but also created fashion drawings, ceramics, and murals. In her essay, Lisa Cornali, PhD candidate at the University of Neuchâtel, explores the models of a floral textile pattern called Asunta, designed by Maria Likarz-Strauss. By comparing it with katagami (finely cut paper stencils from Japan) in the MAK collection, she traces Likarz’s sources of inspiration. Cornali shows that Hoffmann already employed katagami in his teaching at the Arts and Crafts School in Vienna. With nearly two hundred patterns, Likarz-Strauss was the most prolific female artist working for the WW Textile Department.

Marie-Eve Celio-Scheurer, former Academic Coordinator of the CTTSC in Washington, DC, and present Curator in Chief of the collection of prints and drawings at the Musée d’art et d’histoire in Geneva, also explores in her essay on the WW Collection within the CTTSC a single textile pattern called Kanarienvogel (Canary), designed by a female artist, Mizzi Vogl. Celio-Scheurer demonstrates that Vogl followed principles similar to figures published in Eugène Grasset’s Méthode de composition ornementale from 1905. Between 1896 and 1905, Swiss-born artist and art theorist Grasset published two main didactic books on ornament, which were among the pedagogic references at the Arts and Crafts School in Vienna and were acquired during the year of their release.

In the fourth section, entitled “The Wiener Werkstaette of America,” Régine Bonnefoit, Professor of Art History and Museum Studies at the University of Neuchâtel in Switzerland, shows the attempts of the WW to open new markets in the

15

United States. Her essay explores its marketing strategies but also the reasons for its failure. In the United States, the innovative textile designs garnered applause for a time in the show business world but rarely found their way into private homes.

The book’s editors are deeply indebted to all the authors for insight into their collections and research topics. Their commitment, generosity, and support made this publication a reality.

We would like to express our heartfelt thanks to the Birkhäuser publishing house for the wonderful opportunity, and for the quality of its editorial staff, in particular Katharina Holas, for the precise coordination of all stages involved in the creation of this book. Our thanks also go to Scribe and to John Sweet for the quality of their proofreading work. We are also indebted to John Wetenhall, Director of The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum; Gerald Bast, Rector of the University of Applied Arts Vienna; and Martin Hilpert, Vice Rector for Teaching at the University of Neuchâtel, for their support and trust.

We would like to thank The Cotsen Textile Traces Study Center at The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum in Washington, DC, and the Faculty of Arts and Humanities and the Institute of Art History and Museum Studies of the University of Neuchâtel for their financial support with the production of this book.

April 2023

1 Werner J. Schweiger, Wiener Werkstätte, Kunst und Handwerk, 1903–1932 (Vienna: Christian Brandstätter, 1982), 17.

2 Paulus Rainer, “Eine Chronologie der Wiener Werkstätte,” in Der Preis der Schönheit. 100 Jahre Wiener Werkstätte, ed. Peter Noever (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2003), 50 and 258.

3 The contract between WW director Otto Primavesi and Joseph Urban dated February 4, 1922, can be found in the estate of Philipp Häusler under the signature ZPH 833 at Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Vienna.

4 For the objects from the Wiener Werkstaette of America, still preserved today in American collections, especially in the Neue Galerie New York, see Janis Staggs, “The Wiener Werkstätte of America,” in Wiener Werkstätte, 1903–1932:

The Luxury of Beauty, ed. Christian Witt-Dörring and Janis Staggs (Munich: Prestel, 2017), 468–505.

5 On the printing of WW fabrics in Switzerland, see Monika Mähr, “Wiener Werkstätte Stoffdruck —kulturelles Erbe in der Schweiz,” in Klimt und Freunde, ed. Daniel Studer and Tobias G. Natter (Schwellbrunn, Switzerland: FormatOst, 2021), 66–75, here 69.

6 Anne-Katrin Rossberg, “Brought to Light: Art and Life of the Wiener Werkstätte Women,” in Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Anne-Katrin Rossberg, and Elisabeth Schmuttermeier, eds., Die Frauen der Wiener Werkstätte / Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte (Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag, 2020), 15.

7 Rainer, “Eine Chronologie,” 18, 323.

8 Thun-Hohenstein, Rossberg, and Schmuttermeier, Die Frauen

16

20

Figure 1 Mizzi Vogl, Kanarienvogel, 1910/11, silk, plain weave, block printed, 18 × 14 cm, Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, Inv. no. T-0193.247

The Wiener Werkstätte Collection within the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection: From Austria to the United States via Switzerland

Marie-Eve Celio-Scheurer

Introduction

Housed today at The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum in Washington, DC, the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection (CTTSC), assembled by Lloyd Cotsen, holds one of the most significant bodies of Wiener Werkstätte (WW) textile samples in the United States.

After a brief presentation of the CTTSC and a general description of its WW Collection, this article will attempt to trace the provenance of this unique collection and focus on the Kanarienvogel design by Mizzi Vogl, taking us from Austria to the United States via Switzerland. As part of this endeavor, connections between Austrian artists, especially Josef Hoffmann, who taught Mizzi Vogl, and Swiss artists, such as Eugène Grasset, will also be evaluated as regards their teaching methodologies.

The Wiener Werkstätte Collection within the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection

Previously housed in a private gallery in Los Angeles, the CTTSC entered its new home at The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum a year after it was donated to George Washington University in October 2018. As part of a generous gift from the late Margit Sperling Cotsen (1934–2022),1 the wife of Lloyd Cotsen (1929–2017),2 and the Cotsen 1985 Trust, the collection came with an endowment to support research and scholarly programming.

21

The CTTSC represents a lifetime of collecting by business leader and philanthropist Lloyd Cotsen and is one of the world’s most significant textile study collections ever assembled. The nearly four thousand textiles of small size (fragments or garments) offer insight into human creativity around the world, from antiquity to the present day. Cornerstones of this collection are objects from Japan, China, India, pre-Columbian South America, late antique to early medieval Egypt, sixteenth- to seventeenth-century Europe, and the WW. The collection also includes sample books, publications, and manuscripts, as well as other works on paper, archival material, and a reference library.

The Cotsen WW Collection represents more than 10 percent of the CTTSC, quite a high proportion considering the global scope of the collection and the fact that the WW covers a limited period (1903–32)3 and place (Vienna). This reflects the importance of the WW in the history of textiles and Lloyd Cotsen’s own appreciation for this period. Cotsen had a particular interest in the original creations of the WW, as the CTTSC and some private belongings testify: in his private office in Los Angeles, Cotsen had a set of furniture consisting of two chairs and a table designed by Josef Hoffmann.4

The WW Collection within the CTTSC consists of over 350 textile samples, a pattern book,5 two textile-covered boxes,6 some works on paper, including two postcards designed by Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980),7 and an early manifesto pamphlet by Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, and Fritz Waerndorfer: Wiener Werkstätte, Productgenossenschaft von Kunsthandwerkern in Wien, 1905.8 The latter presents the goals of the WW program: pushing against mass and machine production, back to individual hand-finished pieces, to the relationship of all arts with design, and to the house as an integral design.

The pattern book is still in its original state, with two cardboards covered with black waxed linen and the WW logo in gold. It comprises 258 block-printed silks and some eightyeight patterns, available in various color combinations. Most of the samples have a paper label glued to the lower left-hand corner. The label lists the title of the design, the name of the designer, and the design number.

22

Sample books were not printed by year; they were a compilation of all available patterns at any given time. According to Angela Völker, who saw the Cotsen WW Collection while it was still in its private gallery in Los Angeles, the samples date between 1910 and the early 1920s.9 If a particular pattern was printed on silk, this does not mean that the pattern was only available in this material; it could also be ordered on cotton or linen. This kind of book was presented to clients, who would select the design, colors, and material and place their order accordingly. The Cotsen pattern book is like a mini collection within the WW Collection in the CTTSC and echoes the small formats preferred by collector Lloyd Cotsen.

Covering the 1910s to 1930, with some fifty WW designers, this collection therefore gives a good overview of the entire span of WW textile production and represents one of the most important bodies of WW textile samples in the United States. It was acquired by Lloyd Cotsen between 1998 and 2015 on the art market in New York, Munich, London, and Switzerland.

From Austria to the United States, via Switzerland

Some objects from the Cotsen WW Collection were acquired from the gallery Kamer-Ruf, in Beckenried, Switzerland, owned by Martin Kamer and Wolfgang Ruf. They never directly met Lloyd Cotsen, but Wolfgang Ruf, as an art collector and dealer in the field of European textiles, was aware of Cotsen’s interest in collecting textiles of small size, especially as this type of collecting was uncommon.10 While focusing on large pieces and costumes, he kept a few WW objects for his own collection, acquired in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, trading what did not fall within his own collecting parameters, such as textile samples and preparatory works on paper. He therefore sold the WW textile samples to Lloyd Cotsen and the WW preparatory works on paper to the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, and this is how two important WW ensembles moved from Switzerland to the United States.11

To further study the connections between Austria, Switzerland, and the United States, this paper will focus on the Kanarienvogel (Canary) design by Mizzi (Marie) Vogl, or Vogel (1884–?).12 Mizzi Vogl was an Austrian textile artist. Before working for the WW, she studied at the k. k. Kunstgewerbe-

23

24

Figure 2 Summer dress made from the fabric Kanarienvogel by Mizzi Vogl, ca. 1915, Galerie Ruf AG, Switzerland, Inv. no. 2155

25

Figure 3 Printing blocks for the fabric Kanarienvogel by Lotte Frömel-Fochler, ca. 1910–15, Galerie Ruf AG, Switzerland

52

Figure 17 Students studying the Collection at Cooper Union Museum, 1921, photography, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York

Beautiful Specimens: Wiener Werkstätte Pattern Designs at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Susan Brown and Caitlin Condell

In 1897, the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration—today known as Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum—opened its doors to the public in New York. It was located on the fourth floor of the Cooper Union for Advancement of Science and Art, the free university founded in the mid-nineteenth century by American industrialist Peter Cooper. Modeled on the Musée des arts décoratifs in Paris, the museum was founded by Cooper’s granddaughters, Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt, with a mission to collect “beautiful specimens of art applied to industry” and become “an educator of the public standard of taste.” Though the museum was open to all as “a practical working laboratory,”1 it specifically aimed at aiding American craftspeople and manufacturers “to elevate the character of their products.”2

Like the Wiener Werkstätte (WW), the Cooper Union Museum offered opportunities for female designers through its affiliated retail shop, Au Panier Fleuri. Opened in 1905, the shop sold goods designed by students of the Cooper Union Women’s Art School: painted furniture and trays, lampshades of silk and paper, writing sets, books, and decorative screens and wall panels. The intention of the original investors was to provide a bridge for young women to access professional design work, and for seventeen years Au Panier Fleuri fulfilled that mission [Figure 17].

Despite its progressive stance in creating career pathways for young women, the museum was less forward-looking in

53

72

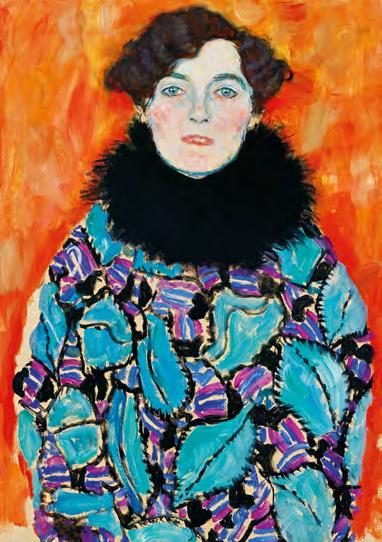

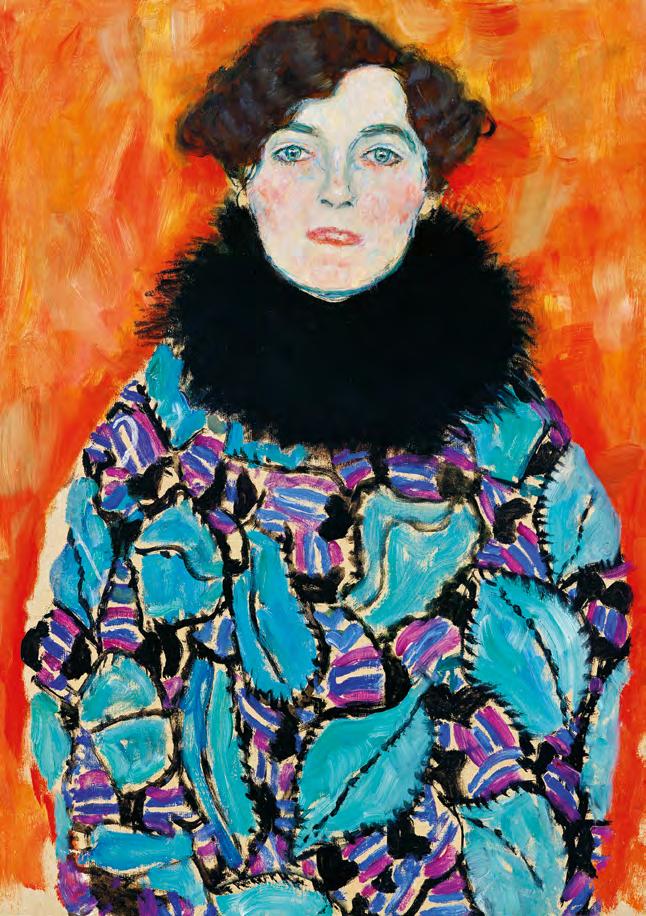

Figure 29 Dress, designed by Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill, produced by the WW, in Kunst und Kunsthandwerk 14, no. 12 (1911): 678

Appropriating the Peasant: Wiener Werkstätte Fashions before World War I

Rebecca Houze

Fashionable women’s dresses produced by the Wiener Werkstätte (WW) before World War I featured slim silhouettes, decorative embroidery, and fabrics printed with stylized floral or geometric patterns. These elements can be traced both to the artistic dress movement of the late nineteenth century and to the growing ethnographic interest in the border regions of Austria-Hungary. Modern artists and designers admired the local costumes worn by indigenous people from rural villages, viewing their garments as authentic and uncorrupted, in contrast to contemporary urban fashions, which were often industrially manufactured and styled according to popular international trends. Did the WW fashions reflect a concern for the lived experience of the rural people who used their own indigenous visual and material culture as symbols of cultural identity, self-determination, or nationalist sentiment? Or were they exploitative, sold for many times the income a peasant embroiderer would have earned for her work? Despite the reformist aims of their designers, the stylish WW dresses and textiles with their lively, colorful, expressive patterns could be considered as examples of cultural appropriation, a concept that implies an imbalance of power, in which the appropriating group benefits at the expense of those whose cultural forms are adopted. They were complex, multivalent artifacts, which reveal that attitudes toward race, gender, and social class in Vienna before World War I were deeply entangled in both progressive and reactionary impulses.

73

88

Figure 35 Madame d’Ora, atelier, portrait of Mileva Roller, 1908, black-and-white glass-plate negative, 22.6 × 16.9 cm, Austrian National Library Vienna, 203.442-D

Cultural Translation and Artistic Reform: Mileva Roller’s and Rosalia Rothansl’s Collections at the University of Applied Arts Vienna

Eva Marie Klimpel

The catalysts for the thoughts in this essay are two groups of seemingly traditional textiles in the holdings of the Collection Fashion and Textiles at today’s University of Applied Arts Vienna. These objects were gathered between 1901 and 1925 at the university’s predecessor institution, the k. k. Kunstgewerbeschule (Imperial Royal Arts and Crafts School) in Vienna by the artist Mileva Roller née Stoisavljevic (1886–1949) and Rosalia Rothansl (1870–1945), the first female professor at the school, who used them as teaching materials and artistic models.1

Many of the members of the Wiener Werkstätte (WW) began their artistic careers at the Arts and Crafts School, the first public institution of the Monarchy to offer women access to higher education. The translation of floral ornaments, previously associated with rural handicrafts, into modernist designs is especially obvious in the block-printed textiles of the WW.

In placing Mileva Roller’s and Rosalia Rothansl’s collections in the context of art-pedagogical and art-critical discourse of around 1900, this paper will convey their link with the revaluation of the textile medium in arts and crafts, the female dress reform movement, and the professionalization of “housework,” all of which were strongly connected to artistic training and production. Using the descriptions of the textiles, this article will attempt to trace a specific “primitivism” of Viennese Modernism, which manifested itself in

89

124

Figure 50 (From top to bottom) Hilda Jesser, Lilly Jacobsen, Vally Wieselthier, and Fritzi Löw, 1918, photography taken in the WW Textile Department, Kärntner Strasse 32, Vienna

Hilda Schmid-Jesser: Career, Interrupted, Reinvented

Janis Staggs

Hilda Jesser (1894–1985)1 joined the Wiener Werkstätte (WW) during World War I [Figure 50]. Her designs were widely admired and she appeared to have an illustrious future ahead of her. Yet her career was interrupted not once, but twice. Her request for a salary and benefits from the WW in 1921 was denied and so she left the firm. Undaunted, she reinvented herself as a painter and pursued a teaching career. Forced into retirement by the National Socialists in 1938, she was reinstated only after World War II.

This paper will examine Jesser’s designs for the WW and consider them in the context of her broader oeuvre.2 Her work reveals a deep empathy for textiles and demonstrates her tremendous and versatile skill as a painter.

Jesser was born in 1894 in Marburg an der Drau in what was then Styria. The town was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the end of World War I. Known today as Maribor, it is based in Slovenia and located south and west of Vienna. In 1900, Maribor had almost twenty-five thousand inhabitants. It was a bustling city on the Drau River, about halfway along the Vienna–Trieste rail line. A picturesque city dating back to the twelfth century, Maribor boasts a number of prominent structures including a Gothic cathedral, one of the oldest surviving synagogues in Europe, and various historic castles and civic structures. Some of the town’s distinguishing architectural features appear to have provided visual inspiration for Jesser.

125

138

Figure 58 Maria Likarz-Strauss, Asunta, 1929, silk, plain weave, block printed, 27.9 × 16.5 cm, Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, Inv. no. T-0193.175

Bright Colors, Stylized Flowers: Notes on Asunta, a Fabric Pattern by Maria

Likarz-Strauss

Lisa Cornali

The quality and stylistic richness of the fabric patterns of Maria Likarz-Strauss (1893–1971) are often emphasized in literature about the Wiener Werkstätte (WW). Through her activity in several departments of the company, but in particular through her work for the textile and fashion divisions, Likarz emerged as one of the most influential female artists of the WW. From her studies at the k. k. Kunstgewerbeschule (Imperial Royal Arts and Crafts School) in Vienna (1911–16) to the company’s closure in 1932, she designed more than two hundred textile patterns—about 15 percent of the more than 1,320 fabric designs created by the WW—which were highly valued for their versatility.1

In this regard, the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Center (CTTSC) holds a representative collection of Likarz’s productions. Thirty-seven samples exemplify nineteen motifs created between 1910 and 1929. They thus cover almost all her activity for the Textile Department and offer an excellent overview of her main stylistic orientations. Early on, Likarz developed geometric and abstract patterns—as in Athos, Marmon, or the famous Irland (Ireland)—but also numerous motifs characterized by increasingly stylized vegetal elements—like Gräser (Grasses) or Menorea. 2 Designs such as Basel and Rhodesia attest to Likarz’s ability to combine stylized plant forms with strong geometric structures.3 Reflecting the variety of her designs, the CTTSC perfectly documents Likarz’s creativity and contrasting styles. The juxtaposition

139

156

Figure 66 Joseph Urban, office space at the WW of America, 1922, Joseph Urban Archive, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University, Scrapbook, Box B25, Folder 11

The Reception of Wiener Werkstätte Fabrics in the United States in the Early 1920s

Régine Bonnefoit

The severe economic crisis that hit Austria following World War I and the collapse of the Danubian monarchy prompted the Wiener Werkstätte (WW) to try to open up new markets in the United States. This study explores WW marketing strategies but also the reasons for their failure in the early 1920s. It relies on the estate of Philipp Häusler (1887–1966), the administrative director of the WW from 1920 to 1924, and on articles from the archives of Joseph Urban, the founder of the Wiener Werkstaette of America. This WW subsidiary opened in New York at 581 Fifth Avenue in June 1922, only to shut its doors a mere eighteen months later, in December 1923, due to a lack of success.1 In keeping with the theme of the book, this essay focuses on WW fabrics.

Joseph Urban and the Wiener Werkstaette of America

Originally from Vienna, Joseph Urban (1872–1933) was an architect, illustrator, stage designer, and interior decorator. Janis Staggs has already presented fundamental research findings on his initiatives to market WW products in the United States.2 On June 9, 1922, Urban opened the Wiener Werkstaette of America on the second story of a building located at 581 Fifth Avenue. In a contract dated February 4, 1922, the Central Head Office of WW granted Urban “the sole right to sell the products of the arts and crafts department in the United States of America for the parent company in Vienna and Wiener Werkstätte A.G. in Zurich.” The contract had

157

158

Figure 67 Joseph Urban, office space at the WW of America, 1922, in Dry Goods Economist, July 29, 1922

the following to say about textile production: “[…] we also expect your support in establishing suitable business contacts for our fashion articles, printed fabrics, laces, etc., etc.”3

Regarding the fabric patterns of the WW artists, a look at the extant photographs of the WW of America rooms reveals Urban’s preference for the original creations of Dagobert Peche (1887–1923). He joined WW in 1915 and served as the business manager of the WW subsidiary in Zurich from 1917 to the end of 1919.4 Segments of the walls in the reception area and in the office space were covered with Peche’s Krone (Crown) pattern.5 In another part of the office space [Figure 66], Peche’s Pappelrose (Hollyhock) fabric pattern can be seen on the upper sections of the wall and on the ceiling.6 An article in the July 29, 1922, issue of the Dry Goods Economist noted the omnipresence of fabrics in all the rooms. In a view of the office space [Figure 67] in this same article, the Krone pattern can be seen covering the wall in the corner of the room and is commented on as follows: “The wall is partly covered with silk of an unusual pattern, suggesting stripes.” To deliver on the objective expressed in its title, “Hints for Decorators,” the article explains how the silk is mounted on the wall: “The method of mounting the rather thin silk on the wall is worth knowing about. Muslin is first used and between it and the silk is placed a soft padding of double-faced canton flannel. The result is very fine.”7 Since the mounting of fabrics on walls is no easy task, Urban made the following offer in a 1923 promotional catalog for WW products: “We undertake complete decoration, including treatment of walls in silk […].”8

To help make these WW products known beyond New York City, Urban staged an exhibition for the Art Institute of Chicago in the fall of 1922.9 A look at the exhibition space once again shows the dominance of Peche’s patterns [Figure 68]: the chair in the center of the room is upholstered with his Parasit (Parasite) pattern, while the curtains around the entrance in the background are made of Pappelrose and the broad stripe above the niches in the partitions features his Grosse Blätter (Large leaves) wallpaper. The view of another room shows a wall in the background covered by three draped lengths of fabric [Figure 69]. The one on the left is the Flieder

159

174

Figure 74 Printing block for the fabric Ameise by Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill, 1910/11, 31.5 × 24 × 4.5 cm, MAK, Vienna, Inv. no. T 13996-3

Research, Scholarship, and Exploration:

Toward the Wiener Werkstätte at the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna

Angela Völker

This article will seek to describe my research on the Wiener Werkstätte (WW) at the MAK—Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna, the museum where I was Director of the Textile Department for thirty-two years (1977–2009), a period that shaped my life and gave me the opportunity to work on its textile, carpet, and fashion collections and, in 2015, even on the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection (CTTSC).

First of all, I would like to draw your attention to a particular aspect of working in a museum that is still significant today. Until 1989 at the earliest, my colleagues and I had never used a computer for our work, which was mainly focused, like my publications, on the objects in the MAK Textile Collection. The diversity of this collection, the materials, the history, and the art history from across the various eras inspired me to concentrate on entirely different key topics of research. Of course, there were and still are many important publications on the MAK’s textiles and the museum has a marvelous library in terms of its holdings and art history and textiles in general, and as a staff member its use was and remains very accessible. But we could not take pictures of objects for documentation purposes within seconds as smartphones allow today. Up until the turn of the millennium, there were no commercial digital cameras and no photo archive of the MAK collection. If inventories existed, they were essentially simple registers or handwritten card indexes with very few images. In most cases we worked directly with the objects, and that

175

190

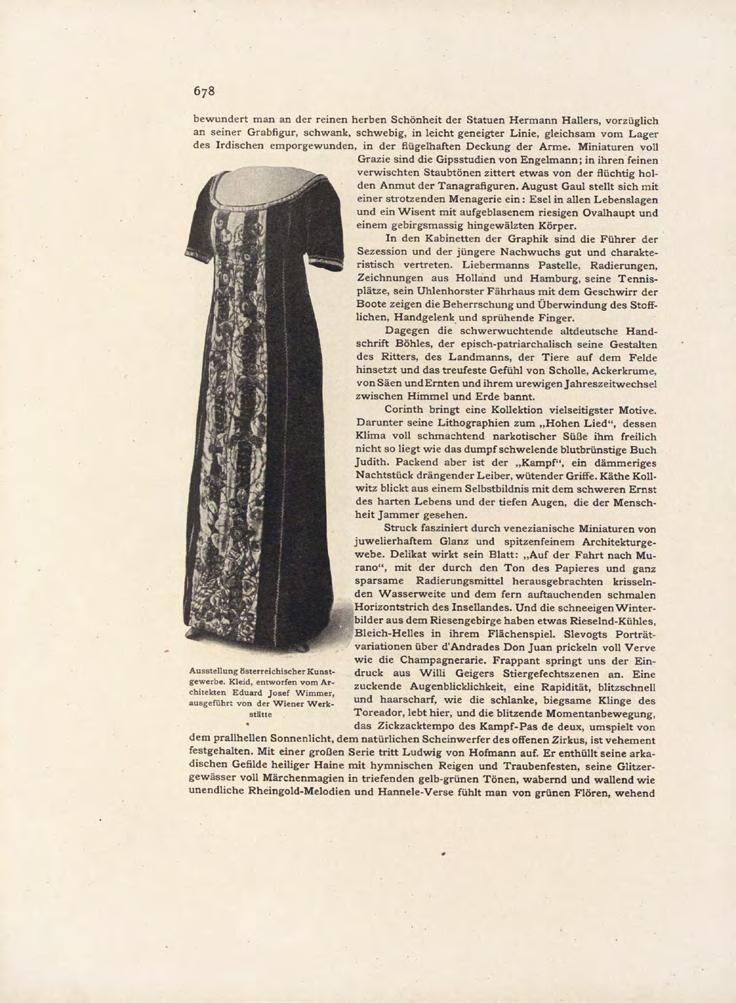

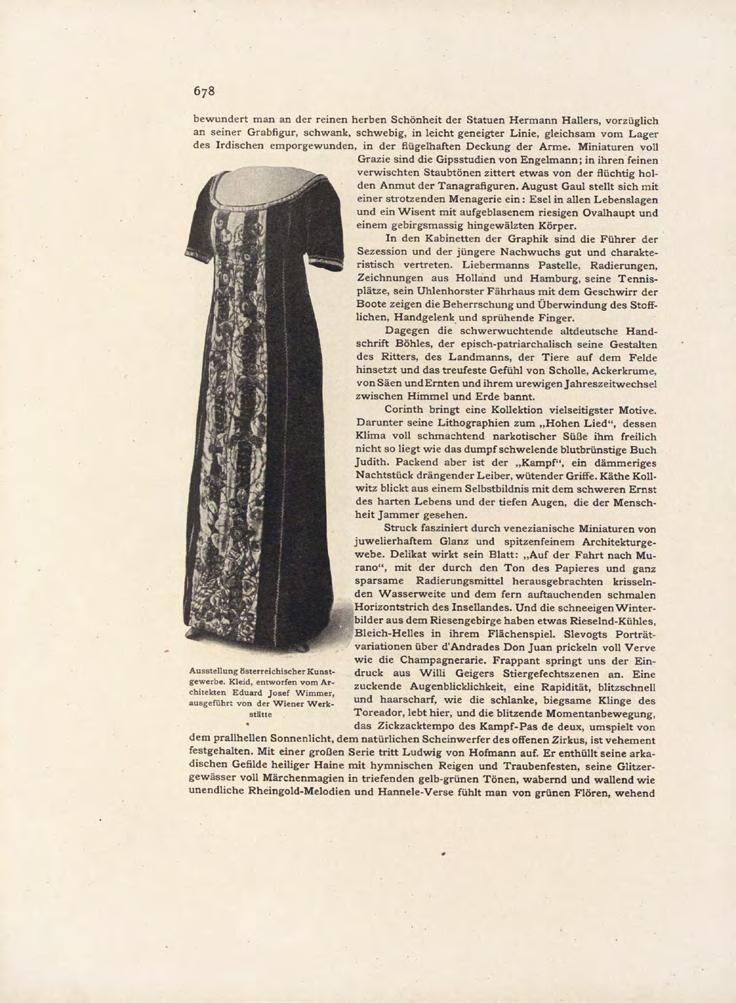

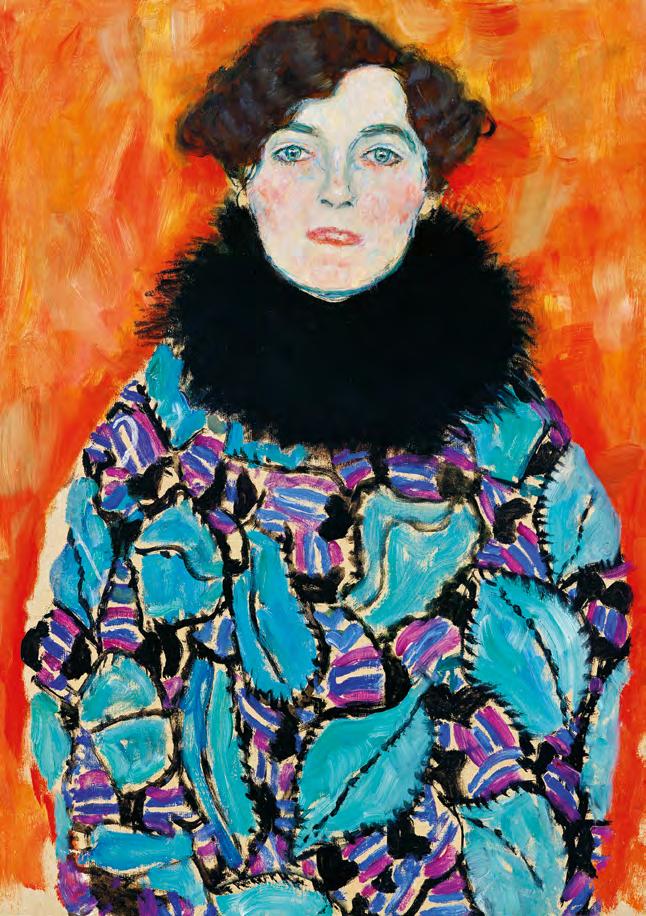

Figure 82 Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Johanna Staude, dressed in an item of clothing made from the fabric Blätter by Martha Alber, 1917/18, Belvedere, Vienna, Inv. no. 5551

191

Figure 83 Martha Alber, Blätter, 1910, linen, plain weave, block printed, 15.9 × 14 cm, Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, Inv. no. T-0193.001

Image Credits

Figures 1–83

Austria

– Austrian Museum of Folk Life and Folk Art Vienna 38

– Austrian National Library 35

– Belvedere, Vienna, Johannes Stoll (photographer) Cover, 82

– Brandstaetter Images / alt: IMAGNO, Vienna 80

– MAK—Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna 9, 11, 13–16, 50, 56, 60, 64

– Branislav Djordjevic (photographer) 12

– Georg Mayer (photographer)

61–62

– Katrin Wißkirchen (photographer) 8, 74

– Private collection, Austria 75

– University of Applied Arts Vienna

– Collection and Archive

36–37, 39–40, 46, 48–49

– Collection Fashion and Textiles, Christin Losta (photographer) 45

– Oskar Kokoschka Center 42–44

France

– akg-images, Paris, Erich Lessing (photographer), AKG433464 78 – Musée d’Orsay, Paris 6

Germany

– Deutsche Kinemathek—Marlene

Dietrich Collection, Berlin 65

– Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg

29, 31, 34, 57

Hungary

– Matyó Múzeum, Mezőkövesd 41

Switzerland

– © Fondation Oskar Kokoschka / 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich 43, 47

– Galerie Ruf AG, Switzerland 2, 3

– Musée d’art et d’histoire, Geneva 4, 7

USA

– Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York 17

– Matt Flynn (photographer)

18–28

– The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Washington, DC, Bruce M. White (photographer)

Cover, 1, 5, 10, 32, 47, 51, 55, 58–59, 76–77, 79, 81, 83

– Joseph Urban Archive, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York 66–69, 72–73

– Metropolitan Museum of Art / bpk 70

– Neue Galerie New York 71

– Hulya Kolabas (photographer)

52

– Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Neue Galerie New York 53, 63

– Private collection, New York 54

– Rebecca Houze, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL, private archive 30, 33 196

Index of Names

Numbers refer to text; numbers in italic relate to a figure.

A

Alber, Martha 186, 190, 191

Altmann, Bernhard 50

Amacher, Rosmarie 26, 34 B

Backhausen, Johann & Söhne 33, 39, 179

Bahr, Hermann 81–82, 111

Beer, Friederike Maria 184, 186, 187, 193

Berger, Arthur 68

Bianchini-Férier 168

Birer Papanek, Luise 68

Birke, Camilla 15, 68

Blonder, Leopold 68, 185, 186

Bruck-Auffenberg, Natalie 51, 79, 82

Brunner, Maria Vera 68

C Calm, Lotte 68

Clavel & Lindenmeyer 26, 165

Cooper, Peter 53

Cotsen, Corinna 33

Cotsen, Lloyd 21–23, 26, 33, 34

Coudurier Fructus 168

Czeschka, Carl Otto 44, 45, 68, 85, 90, 105, 108, 110

Diaghilev, Sergei 116

Dietrich, Marlene 140, 149, 153, 196

Dostal, Ignaz 55, 68

F

Fischel, Hartwig 74, 79, 85–87

Flammersheim & Steinmann 178

Flöge, Emilie 39, 46, 51, 82, 86, 87, 91, 102, 115, 117, 121, 178, 192, 200

Flögl, Mathilde 54, 59, 61, 65, 68, 178, 192

Foltin, Wilhelm 68

Friedmann-Otten, Mizi 68

Frömel-Fochler, Lotte 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 68, 84, 85–86, 103

G

Gilliard, Eugène 32

Grasset, Eugène 15, 21, 27, 28, 30, 32, 35

Griessmaier, Viktor 177, 192

Guttmann, Leopoldine 15, 91 H

Haberlandt, Michael 79, 81, 87

Häusler, Philipp 16, 69, 130, 136, 157, 161, 164, 170–71

Hearst, William Randolph 160, 167

Hevesi, Ludwig 103, 108, 116

Hewitt, Eleanor 53, 69

Hewitt, Sarah 53, 69

Hirsch, Heddi 68

Höchsmann, Gertrud 68

Hodler, Ferdinand 32–33, 35

Hoffmann, Josef 12–13, 15, 21–22, 26–27, 32–35, 39–40, 41, 45, 50, 54, 59, 61, 68, 74–75, 80, 81–82, 85, 90, 103–5, 107, 115, 117, 126–27, 128, 130, 140–41, 148, 161, 164, 171, 177–78, 182, 186, 187, 192–93

Hofmann, Alfred 38, 50

Hofmannsthal, Hugo von 111

D

197

Itten, Johannes 32, 35

J Jacobsen, Lilly 68, 124

Jeanneret, Charles-Édouard (future Le Corbusier) 32

Jonasch, Wilhelm 68, 85

Jordan, Vance 61

Jungwirth, Maria 68

K

Kabarett Fledermaus 107

Kalhammer, Gustav 68

Kallmus, Dora (Madame d’Ora) 82, 90

Kamer, Martin 23, 34

Klimt, Gustav 85, 87, 115, 117, 182, 184, 186, 190, 192, 193

Klimt, Helene 82

Knips, Sonja 180, 182, 193

Koehler, Mela 15, 74

Kokoschka, Oskar 14, 22, 33, 105, 106, 107–8, 109, 110–11, 113–14, 116–20

Kopriva, Erna 68

Körösfői-Kriesch, Aladár 79

Kovacic, Valentine 68

Kraus, Karl 116, 120

Krenek, Carl 68

L

Lang, Erwin 110–11, 116

Lang, Lilith 14, 105, 108–11, 112, 116–20

Lang, Marie 110

Larisch, Rudolf von 90, 110

L’Éplattenier, Charles 32

Lesznai, Anna 14, 15, 75, 76–77, 78–79, 86

Levetus, Amelia Sarah 45, 78, 79, 86

Lhuer, Victor 40, 43

Likarz-Strauss, Maria 11, 15, 40, 45, 54–55, 57, 59, 62–64, 68–69, 91, 138, 139–41, 142–43, 146, 147–48, 150, 151–53, 178, 182, 183

Löffler, Bertold 105, 110, 118, 119, 121

Loos, Adolf 107, 116, 120

Löw-Lazar, Fritzi 68, 124

Luza, Reynaldo 168, 169

Mackintosh, Charles Rennie 45

Mahler, Alma 120

Mallina, Erich 110

Martens, Wilhelm 61

Matyó embroidery 14, 75, 78–79, 91, 101

Mell, Max 116

Metzner, Franz 90

Moser, Ditha 46, 47

Moser, Koloman 12, 22, 39, 44, 45–46, 48, 61, 105, 140, 177–178, 192

Müllner, Emma 68

Muthesius, Anna 99, 104

Nechansky, Arnold 68

Oman, Valentin 137

Pappenheim, Bertha 121, 177, 192

Peche, Dagobert 12, 40, 54, 59, 68–69, 130, 133, 159–61, 165, 168, 170–71, 177–78, 186, 188, 192

Perlmutter, Marianne 68

Piotrowska-Wittmann, Angela 68

Poiret, Paul 36, 40, 42, 46, 50, 54

Primavesi, Eugenia 130

Primavesi, Otto 16, 130, 170, 171

Prutscher, Otto 33

I

M

N

O

P

198

Riegl, Alois 95, 103, 177

Rix-Ueno, Felice 15, 54, 56, 58, 59, 60, 61, 68, 148, 152–53, 168, 170, 178, 193

Roller, Alfred 90

Roller, Mileva 14–15, 88, 89–90, 93, 98–99, 102

Rothansl, Rosalia 14–15, 26, 34, 89, 91, 96, 99, 102–3, 111, 117, 147, 153, 193

Ruf, Wolfgang 23, 24, 34, 69

Ryšavy, Juliana 68

S Salubra 50, 178

Schaschl-Schuster, Reni 68

Schiele, Egon 108

Schmid-Jesser, Hilda 11, 15, 61, 68, 69, 91, 124, 125–27, 128, 129–31, 132–33, 134, 135, 136–37

Schmidt, Max 178

Schnischek, Max 40

Schönberg, Arnold 116

Schröder, Anny 61, 68

Schultze-Naumburg, Paul 98

Siebold, Heinrich von 141, 144–45, 152

Singer, Susi 68

Sperling Cotsen, Margit 21, 33

Stadlmayer, Marie 61, 66, 68

Stark, Adele von 90

Staude, Johanna 186, 190

Sternberg, Josef von 149

Stoclet, Adolphe 107–8

Stoll, Luise 68

Stonborough-Wittgenstein, Margarethe 46, 48

Urban, Mary 164, 171

van de Velde, Henry 99

Vogl, Mizzi 11, 15, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26–27, 34, 68

WWabak, Emma 68

Waerndorfer, Fritz 12, 22, 45, 107–8, 177

Weinberger, Gertrud 68

Weissenberg, Marie 68

Wieland, Barbara 26, 34

Wieland, Monica 26, 34

Wieland, Richard Rudolf 26, 34

Wieselthier, Vally 15, 45, 61, 67, 68, 91, 124

Wiesenthal, Grete 111, 116

Wimmer-Wisgrill, Eduard Josef 13, 35, 39–40, 68, 72, 74–75, 82, 116, 161, 164, 171, 174, 181, 186, 193

Wintersteiner, Hanna 68

Witzmann, Carl 130–31, 136

Zels, Marianne 39, 68

Zimpel, Julius 68

Zovetti, Ugo 68, 186, 187, 189

Zuckerkandl, Eleonore 68

Zülow, Franz von 61, 68, 103, 108, 160

Trinkl, Maria 68

, 170–71

R

T

U

Urban, Joseph 12, 16, 156, 157, 158, 159–61, 162–63, 164, 166

V

Z

199

Bonnefoit, Régine

Régine Bonnefoit holds a doctorate in Art History from the University of Heidelberg (1995) and a habilitation at the University of Passau, Germany (2006). She was Research Assistant at the Department of Drawings of the Louvre in Paris (1992–94) and Trainee at Berlin Museums (2000–2001). In 2001, she became Assistant at the Institute of Art History at the University of Lausanne and later Curator at the Oskar Kokoschka Foundation in Vevey, Switzerland (2006–16). After a professorship at the Swiss National Science Foundation, she was appointed Professor of Contemporary Art History and Museum Studies at the University of Neuchâtel in Switzerland. Curator and co-curator of numerous exhibitions, she is also the author of writings on Austrian and German Expressionism (Oskar Kokoschka, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner), the Bauhaus (Paul Klee), and the Russian avant-garde.

Brown, Susan

Susan Brown is Associate Curator and Acting Head of Textiles at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, where she oversees a collection of over 27,000 textiles

produced over 2,000 years. Her exhibitions include Extreme Textiles: Designing for High Performance (2005); Fashioning Felt (2009); Quicktakes: Rodarte (2010); Color Moves: Art and Fashion by Sonia Delaunay (2011); David Adjaye Selects (2015); Scraps: Fashion, Textiles and Creative Reuse (2016); Saturated: The Allure and Science of Color (2018); Contemporary Muslim Fashions (2020); Suzie

Zuzek for Lilly Pulitzer: The Prints that Made the Fashion Brand (2021); A Dark, a Light, a Bright: The Designs of Dorothy Liebes (2023). She lectures regularly for the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University.

Celio-Scheurer, Marie-Eve

Marie-Eve Celio-Scheurer, PhD, is Head of the Collection of Prints and Drawings at the Musée d’art et d’histoire in Geneva. She holds a doctorate in Art History from La Sorbonne. She was a grant recipient from the Swiss National Science Foundation and a research fellow at the German Center for Art History in Paris, where she worked at the Musée d’Orsay. After being a consultant for the National Salarjung Museum in Hyderabad and for unesco in

Authors 202

New Delhi (2004–12), she worked as a scientific collaborator at the Museum Rietberg in Zurich and lectured at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland before moving to Washington, DC, where she led the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Center (2018–22). Curator of numerous exhibitions, her publications and research areas are in the fields of Art Nouveau, early twentieth century, contemporary art scene, theory and circulation of ornaments, and global cultural exchanges.

Condell, Caitlin

Caitlin Condell is the Associate Curator and Head of the Department of Drawings, Prints, and Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, where she oversees a collection of nearly 147,000 works on paper dating from the fourteenth century to the present. She has organized and contributed to numerous exhibitions and publications, including Making Room: The Space between Two and Three Dimensions (2012–13) at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA); How Posters Work (2015); Fragile Beasts (2016–17); Nature— Cooper Hewitt Design Triennial (2019–20); After Icebergs (2019–20); and Underground Modernist:

E. McKnight Kauffer (2021–22)

at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She worked pre-

viously at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in the Department of Prints & Illustrated Books.

Cornali, Lisa

Lisa Cornali is currently a PhD candidate and Assistant to Professor Régine Bonnefoit at the Institute of Art History and Museum Studies, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland. She holds a BA in Art History, History and Ethnology from the University of Neuchâtel, and an MA in Historical Sciences (mainly History of Art) from the Universities of Lausanne and Neuchâtel. She specialized in the study of nineteenth- and twentieth-century European art, with a focus on cultural history and artistic practices of reception and circulation of models. Her doctoral thesis, under the joint supervision of the University of Neuchâtel and the École du Louvre in Paris, examines the reception of John Flaxman’s outline engravings in nineteenth-century English and French art. Over the last six years, she has also worked in various Swiss and German museums and research institutes.

Houze, Rebecca

Rebecca Houze is Professor of Art and Design History at Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois. In 2022 she was a Fulbright visiting scholar at the Research Centre for the Humanities Institute of Art History, Hungarian Academy of 203

Sciences, in Budapest. Her research focuses on the relationship between art, industry, collection, and display in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. She is the author of Textiles, Fashion, and Design Reform in AustriaHungary before the First World War: Principles of Dress (2015) and New Mythologies in Design and Culture: Reading Signs and Symbols in the Visual Landscape (2016). Her new project investigates design history and cultural heritage in the landscape and built environment of world’s fairs and national parks in Europe and North America at the turn of the twentieth century.

Klimpel, Eva Marie

Eva Marie Klimpel studied Art Therapy and holds a master’s degree in Conservation and Restoration from the University of Applied Arts Vienna. She was part of diverse projects such as a conservation campaign in Patan Museum, Kathmandu, a practical semester at the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, and multiple collection care campaigns in Austria. For her final thesis, she focused on the problem of foxing in nineteenth-century lace, experimenting with enzymes and chelating agents to remove it. She has planned, designed, and organized the renewed storage systems of three small textile collections, thereby gaining broad experience

in preventive conservation. Klimpel works as a Textile Conservator for the Collection and Archive of the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

Reinhold, Bernadette

Bernadette Reinhold, PhD, is Director of the Oskar Kokoschka Center and Senior Scientist at Collection and Archive at the University of Applied Arts Vienna since 2008. She studied History and Philosophy, and holds a doctorate in Art History from the University of Vienna. Her research projects, publications, exhibitions, and teaching are focused on architectural and urban planning history, modern art, and Austrian cultural policy. Recent research project: “‘Sonderfall’ Angewandte: The University of Applied Arts Vienna under Austrofascism, National Socialism and the Postwar Period.”

Her recent publications are: Oskar Kokoschka und Österreich. Facetten einer politischen Biografie (2023); Margarete SchütteLihotzky. Architecture. Politics. Gender. New Perspectives on Her Life and Work, coedited with Marcel Bois (2023); and Oskar Kokoschka: Neue Einblicke und Perspektiven / New Insights and Perspectives, coedited with Régine Bonnefoit (2021).

Staggs, Janis

Janis Staggs is Director of Curatorial and Manager of Publications at Neue Galerie New York, where she 204

has worked for more than twenty years. During her tenure at the museum, Staggs has curated a number of exhibitions, including Wiener Werkstätte Jewelry (2008), Gustav Klimt and Adele BlochBauer: The Woman in Gold (2015), The Expressionist Nude (2016), and Wiener Werkstätte Fashion and Accessories (2020–21), among others. She served as co-curator of Wiener Werkstätte, 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty (2017) and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (2019). A specialist in the decorative arts, her work focuses on the intersection between the fine and decorative arts, with an emphasis on the Vienna 1900 era. Staggs has lectured widely. She taught a graduate seminar on Vienna 1900 for the MA Program in the History of Design and Curatorial Studies at Parsons, The New School of Design, in conjunction with the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, in 2017.

Steinhäußer, Lara

Lara Steinhäußer was appointed, in 2019, Curator of the Textiles and Carpets Collection at the MAK— Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, where she has been working since 2011. She completed her Art History studies at the University of Vienna with a master’s thesis on “The Wiener Werkstätte and Paul Poiret: Collaborations, Influences and Differences in Viennese and

Parisian Fashion and Their Media Representation between 1903 and 1932.” In addition to her research focus on Austrian textile art and fashion of the early twentieth century and their international networks, she is currently concerned with contemporary positions at the intersection of fashion and art, as well as the historical development of textile consumption up to slow fashion.

Völker, Angela

Angela Völker, PhD, holds a doctorate in Art History from the University of Vienna (1972). She served as Assistant Curator at the Museum of Applied Arts in Frankfurt am Main (1972–73). Völker then worked as Curator of Textiles at the Bavarian National Museum in Munich (1974–76) and at the MAK— Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna (1977–2009). She also held the position of Vice-Director for the MAK (1986–93). She has given lectures at the University of Applied Arts Vienna and the University of Vienna, and was visiting professor at the Academy of Arts in Linz. Her other accomplishments include a fellowship at the Metropolitan Museum of Arts, Islamic Department, in New York (1997–98). Völker’s main fields of work and publication center on fashion and fabrics of the Wiener Werkstätte, the Russian avantgarde, Biedermeier textiles, Oriental carpets, lace, and Coptic textiles.

205