THE YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW

MASS INCARCERATION AND COVID-19

THE RISE OF AN UNLIKELY PUBLIC HEALTH ALLY: BRAZILIAN DRUG CARTELS

WHY IS OUR GENOME DATA SO WHITE? A DISCUSSION ON THE LACK OF REPRESENTATION IN GENOME-WIDE

VOL.

NO. 1

FALL 2020

8

17

ASSOCIATION STUDIES 09 13

TABLE

CONTENTS Why is Our Genome Data So White? A Discussion on the Lack of Representation in Genome-Wide Association Studies • Ann-Marie Abunyewa The Doctor with a Gavel: Keeping the Gates to the Constitutional Right to Health in Brazil • Murlio Dorion The Rise of an Unlikely Public Health Ally: Brazilian Drug Cartels • Sophia De Olivera COVID-19 and Mental Health: Sleep, Anxiety, and Suicide • Mika Yokota Mass Incarceration and COVID-19 • Amma Otchere On Average, What People Think About Covid-19 Responses, and the New Vaccine • Ryan Bose-Roy A COVID-19 Vaccine: What’s Been Done and What’s to Come • Maiya Hossain Uighur Cultural and Ethnic Genocide in 2021: Understanding Humanitarian Crises Through the Lens of a Continuing Pandemic • Sherry Chen FALL 2020 VOL. 8 NO. 1 03 06 09 13

OF

17 21 23 26

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Dear Readers,

Amidst the ongoing pandemic, we are excited to release the Yale Global Health Review’s Fall 2020 issue. While this project arrived with many challenges, our team has met each with enthusiasm and accomplishment. We hope that our publication serves as a initiative for global health discussion both at Yale and beyond.

In this issue, our writers explore health disparities emerging from the American genetics field, Brazillian law— and most prominently—Covid-19. They navigate serious and widespread ramifications on quality care. How misrepresentation in research and social policy impact efficacious treatment development. How biological disease confers multifaceted consequences in the context of mental health, social determinants, and various cultural responses. Such health topics are extremely urgent in contemporary society.

The creation of this magazine could not have been possible without our dedicated team: the writers, editors, and designers. We would also like to thank our new members involved in this issue, including the Arts Director, Operations and Outreach Manager, Webmaster, and illustrators. Ultimately, we are sincerely grateful to you, the readers, whom we thank for reading our work and considering the issues at hand.

For more information on global health, please visit our website at yaleglobalhealthreview.com.

Jenesis Duran, Jane Fan, and Sophia Zhao

MASTHEAD & STAFF

Editors-in-Chief

Jenesis Duran

Jane Fan

Sophia Zhao

Editors

Jenesis Duran

Jane Fan

Gianna Griffin

Sein Lee

Amma Otchere

Natasha Ravinand

Sophia Zhao

Webmaster

Ishani Singh

Illustrators

Malia Kuo

Tori Lu

Michelle Foley

Sarah Teng

Writers

Ann-Marie Abunyewa

Ryan Bose-Roy

Sherry Chen

Murilo Dorion

Maiya Hossain

Sophia De Olivera

Amma Otchere

Mika Yokota

Production & Design

Ann-Marie Abunyewa

Lauren Chong

Manuljie Hikkaduwa

Sein Lee

Ishani Singh

Sophia Zhao

Arts Director

Alice Mao

Operations & Outreach Manager

Sophia De Olivera

ABOUT THE REVIEW

The Yale Global Health Review is the premiere undergraduate-run publication at Yale University covering topics in health. We feature original research, thoughtful commentary, and balanced reporting with a global health focus. Our goal is to bridge scholarship and practice, connect students and faculty, and bring together voices from across a spectrum of disciplines and sectors. The YGHR is a hub for discussion and engagement on all issues relevant to global health – in print and online, at Yale and beyond.

SPONSORS

We would like to thank the Yale Global Health Leadership Institute, Yale Global Mental Health Program, Yale China, the Yale School of Public Health AdmissionsDepartment,and theYaleUndergraduate Organizations Committee for their support. Alice Mao is a first-year in Morse College, and plans to major in Art with a concentration in Painting/ Printmaking. Alice has also illustrated for the YDN, the Record, and the New Journal, and works as a graphic designer at the Yale University Art Gallery. Her work can be viewed online at www.alice-mao.com.

COVER ARTIST

The Doctor with a Gavel

Keeping the Gates to the Constitutional Right to Health in Brazil

By Murlio Dorion

By Murlio Dorion

João da Silva is a 61-year-old Brazilian man with a severe hernia that causes constant pain and nausea. He was diagnosed in March but, because of the pandemic, the local government relocated his doctor to a field hospital, pushed non-emergent surgeries, and left João waiting for his urgent procedure at least up until November when I met him. With no end in sight, this wait could cost him his kidney or even his life.ᵃ João is a user of Brazil’s Unified Healthcare System (SUSᵇ), which was created by the 1988 Constitutional Assembly as part of a plan to revolutionize the country’s exclusionary healthcare model. Although a private option still exists, the vast majority of Brazilians are uninsured and rely almost solely on the free healthcare offered by the SUS.

YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW 3

Tori Lu

Legally, this should not be a problem, since Brazilian citizens have a constitutionally guaranteed right to health. Article 196 of the Federal Constitution states: “Health is everyone’s right and a duty of the State, upheld through social and economic policies that aim at the reduction of the risk of disease and other harm, and at the universal and equitable access to actions and services for its promotion, protection, and recovery.” 1, c

This passage gives a broad definition of health under State responsibility. It very clearly establishes the principle that should guide public policy including, but not limited to, healthcare. However, it is ambiguous whether this right can be demanded in courts. Social rights were a new concept, and there was no consensus on whether such postulates were merely policy guidelines or an irrefusable call to action by the state.

that the state of Santa Catarina was constitutionally required to cover the costs of stem cell treatment for a patient with Duchenne, a hereditary muscle dystrophy disorder.2 This decision was based on the “impossibility to postpone the fulfillment of the political-constitutional duty...of securing the protection of health for all (Constitution, article 196)”.d Later in his short decision, de Mello decided that the individual right to life, crystalized in article 5 of the Constitution, takes precedence over the “financial and secondary interest of the State,”ᵉ which the governor of Santa Catarina invoked to justify their government’s incapacity to fund the treatment.

This decision created a recourse within the State to request the immediate protection of the unalienable right to health. In a system that sometimes struggles with delays, shortages, and unreasonable waiting times, such an avenue is crucial to ensure that urgent cases are treated with the haste they require. Since then, this decision has been corroborated and cited as precedent in numerous rulings: between 2014 and 2019, 800,000 right-to-health cases were introduced in courts throughout the country, with access to medications being the most frequent petition3. Access to surgeries – which João would need – represent 17% of such petitions in Distrito Federal.⁴

patients and the slow evolution of therapeutic consensus, courts were an important resource for advocacy groups, since judges can act in a counter-majoritarian fashion to protect the rights of the sick, regardless of social taboos, prejudices, or opinions.⁵ This was crucial to securing free access to medications that were not available in the country, some of which are now part of the standard cocktail for the disease.⁶

The later passing of law 9313/96, which requires HIV drugs to be available in the SUS, was still not enough to secure this right, and patients were forced to appeal to judges to access these drugs. The city of Porto Alegre, for example, claimed in court that budgetary decisions were the sole duty of local governments, as stated in the constitution. Therefore, even if their budget could not fund the HIV treatments, a court could not interfere with the city’s decision without overstepping the attributions of the judicial branch. Nonetheless, a landmark decision in the year 2000 rejected this claim and solidified the thesis that the right to health is a prerogative of the judiciary branch. Thus, Porto Alegre was forced to provide the necessary anti-HIV drugs⁷ and, more

However, less than a decade after the constitution was proclaimed, courts started to sketch the future of this right. In 1997, Supreme Court minister Celso de Mello determined

In Brazil, during the peak of the AIDS epidemic in the late 1990s, court rulings based on article 196 were crucial to guaranteeing that HIV-positive individuals had access to the quickly evolving treatment landscape for their illness. Due to the stigmatization of

broadly, courts were affirmed as important actors for the proper functioning of the public healthcare system.

However, the steady increase of health-related petitions since then³ is concerning. As important as the judicialization of health is to remedy momentary injustices, it poses a fundamental threat to the universality of the system, since access to the judicial system is not equitable. A study in the state of Minas Gerais found that over 70% of right-to-health suits were made by private lawyers, and 87.5% of petitions are accompanied by a petition made by a private-sector doctor. ⁸ The ability to pay

4 VOLUME 8, NO. 1

” “

As important as the judicialization of health is to remedy momentary injustices, it poses a fundamental threat to the universality of the system, since access to the judicial system is not equitable.

” “

Courts were an important resource for [HIV] advocacy groups, since judges can act in a counter-majoritarian fashion to protect the rights of the sick, regardless of social taboos, prejudices, or opinions.

Supreme Court of Brazil in session

for lawyers, however, is not the only obstacle to this right: there also is a significant socioeconomic gradient in citizens’ understanding of their rights. A 2016 poll found that only 30% of those earning less than 4 times the minimum wage self-reported understanding the rights contained in the constitution, as opposed to 70% of those who earn over 12 times the minimum wage.⁹ The marginalized are often not present in the courts that are meant to uphold their rights.

In the 2000 decision on HIV treatment, minister Celso de Mello claimed that forcing the city to provide treatment free-of-charge was a demonstration of solidarity with the lives of those that “have nothing, other than consciousness of their own humanity and essential dignity.” If such a consciousness is unequally distributed along socioeconomic lines, this statement –and the transformation of health into a judicial object - will act as one more driver of exclusivity within the public healthcare system.

The success of the HIV movement did not occur despite these socioeconomic inequities, but rather because of them. Between 1987 and 1998, HIV patients were disproportionately wealthy, and more likely to be students and professionals.10 As effective as litigation was in overpowering the implicit homophobia underlying the lackluster governmental response to HIV, it also ensured that public resources went to those who already had funds in their bank accounts.

Transferring part of the decision-making away from democratically accountable bodies and into the courtroom fundamentally

changes the logic of the healthcare system. Popular participation is a core constitutional trait of the SUS¹, which cannot be fulfilled when technocratically-selected judges make decisions that impose burdens on the budget. The immediate need of a single patient, which takes precedence in the eyes of the judge, can have destructive effects on the overall public health plans for a given political entity. As much as 3% of the healthcare system expenses

complications increased the financial burden on the healthcare system, thus diverting resources away from what was necessary to resolve the situation: buying an almost century-old antibiotic.

The emergency-focused prerogative of the judge also hinders the tackling of systemic problems. Lack of proper sewer access is a critical problem in Brazil and, in 2015, 1760 deaths

are determined in courtrooms,³ and, in 2014, almost 10% of the pharmaceutical budget in Distrito Federal was decided by judges to meet the needs of individual cases rather than that of the overall population.12

This upheaval of the underlying logic of resource allocation creates obstacles for a system that already struggles with long-term planning. Between 2014 and 2017, Brazil went through a penicillin shortage due to a lack of funds and an overreliance on imports.13 The consequent syphilis outbreak that ensued affected poorer neighborhoods more severely14 and, as those neighborhoods struggled to control transmission, reinfections became more common and newborns started contracting neurosyphilis in the womb.15 This started a self-fulfilling cycle, as treating downstream

were caused by sanitation-associated diarrheal diseases.16 However, it is impossible to frame a case about a lack of sewage treatment in the terms that have been accepted by courts: unlike the HIV case, there is no “impossibility to postpone the fulfillment of the political-constitutional duty,” so the issue is allowed to persist and slowly wither citizens’ health away.

Courts are currently not a viable option to tackle distal causes of disease. Their resource allocation logic favors patients at the end of the disease pathway where the only available treatments are less effective and more expensive. The double-edge of the judicial sword must be wielded carefully: on the one hand, it serves as an essential escape from the Kafkaesque edge cases; but, on the other hand, it can be corrupted into a regressive force that takes from those who need the most. Fortunately, the Supreme Court has attempted to impose limits on judges’ discretionary power in a 2019 decision, imposing criteria such as blocking experimental treatments from being litigated.17 While the political problem of perfecting the SUS is not solved, courts, with their vices, will continue to be an increasingly important part of the healthcare system.

And, for João da Silva, they are his last chance. As his hernia worsens every day, a judge’s ruling could decide whether he gets surgery or spends his last few months waiting for a doctor to return his call.

YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW 5

www

Murilo Dorión is a sophomore in Silliman. He can be contacted at murilo.dorion@yale.edu

“ ”

The double-edge of the judicial sword has to be wielded carefully: on the one hand, it serves as an essential escape from the Kafkaesque edge cases; but, on the other hand, it can be corrupted into a regressive force that takes from those who need the most.

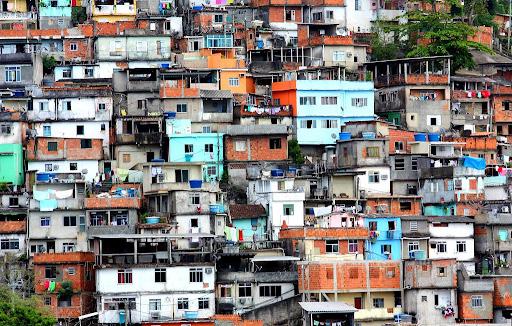

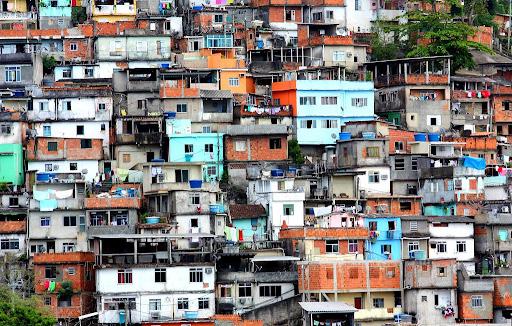

A favela settlement in Brazil that lacks a sewage system

Covid-19 and Mental Health:

Pixabay

The Spring Festival on January 25, 2020 has become an unexpected and unforgettable memory for the people of China. On December 31, 2019, Wuhan Municipal Health Commission authorities reported multiple pneumonia cases of unknown etiology in Wuhan, Hubei Province. A series of events that followed disallowed the country to celebrate the renowned annual festival. On January 1st, the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan linked to the first four reported cases closed. The city went into lockdown on the 23rd. Then, COVID-19 was proven capable of human-to-human transmission. With countries such as Italy, Iran, and Japan reporting surging cases early in the year, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020. Quarantine and social distancing measures were then implemented as safety guidelines. With the world in an emergency health crisis, not only is the physical aspect of health a number one priority, but the mental aspect of health also remains in need of attention. Constant isolation and the deprivation of human interaction have caused trouble for many across the world. The pandemic has undoubtedly impacted people’s psychosocial wellbeing, with emphasis on sleep, anxiety, and suicide. 1

Background

Mental Aspect

Seeing the constantly rising cases, anxiety creeps in and tickles the unsettled mind. COVID-19 has transformed hugs and kisses into weapons. Not visiting grandparents became an act of love, and money has lost its power. Quarantine has devastated the world economy and the mental wellbeing of many. Extensive periods of isolation and social distancing may give rise to concerning mental health issues.

The Science Behind Sleep, Anxiety, and Suicide

There are four stages of sleep, separated into Rapid Eye Movement (REM) and non-REM sleep. The first nonREM stage is called N1. It is the stage between sleep and wakefulness, where the brain starts to produce theta waves. Hypnagogic hallucinations may occur

along with hypnic jerks. People are harder to awaken during N2. More theta waves are produced along with sleep spindles, which are bursts of rhythmic brain activity that help inhibit some cognitive processes; the k-complexes produced suppress cortisol arousal and keep people asleep and aid memory consolidation. N3 is a deeper stage of sleep where the person is “dead to the world”. The Electroencephalogram (EEG) will show a much slower frequency with high amplitude signals - delta waves. This is the stage where people walk or talk in their sleep. REM is the stage associated with dreaming. The EEG resembles wake time, but the body is in a state of sleep paralysis to prevent the person acting out their dreams. 2 Despite having four stages, sleep is a 90-minute cycle with N3 returning to N2 before entering REM: N1->N2->N3->N2->REM.

We need sleep for various reasons, including recuperation, mental function, and growth. Yet, COVID-19 has heightened levels of stress and anxiety, disrupting our natural rest pattern. Cortisol, our stress hormone, should be at low levels when entering sleep; the level gradually rises as we wake up. But, stress can cause the curve to be reversed. High cortisol levels at bedtime hinders the ability to fall asleep. 3 Glucocorticoid receptors will be activated, leading to elevated cortisol releasing hormone, which decreases short wave sleep. Light sleep is increased, and wakes during the night occur more often, which leads to more anxiety and stress regarding falling asleep. This vicious cycle impedes the replenishment of the circadian rhythm, and blood sugar levels may also plunge into chaos and spike during the evening 4

And, above mentioned emotional instability caused by objective isolation or perceived loneliness both contribute to suicidal ideation. This pandemic may cause increased suicidal rates during and even after the crisis.

Discussion

Healthcare Workers

A survey was sent out through Chinese social media by health departments in Shenzhen to examine the public’s mental health burden. Results demonstrated that the healthcare worker group - doctors, nurses, healthcare administrators - showed the most significant mental strain due to the pandemic. Their group also reported the highest rate of poor sleep quality (23.6 percent), evaluated with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), with a P-value less than 0.001, allowing us to reject the null hypothesis that ‘there is no relationship between COVID-19 and sleep quality in health workers’. The higher number for health workers comes as no surprise as 16-hour shifts and exhaustion from the frontline fighting deprive them of proper recuperation, raising the risks of chronic stress, distress, and anxiety. 5

Additionally, the hours dedicated to evaluating the pandemic situation were revealed to contribute to stress levels. 6 Most nurses spend over three hours thinking about the pandemic per day due to the intensity of their contact with COVID patients and their need to assist with the daily living of the ill. Coupled with the wearing of humid, air trapping personal protective equipment and diapers for their whole shift, the nurses have completed their duty in exchange for their wellbeing. A female nurse from Hubei Province that joined the COVID ward on February 4th commented that she found it extremely tough to carry out normal processes such as venipuncture due to the thick layer of gloves; reading medicine labels has also become hard of a task since the goggles blur up. “I am very anxious and irritable, because I have so much work to do but I can’t see well.” she said. 7

Doctors and physicians must continuously review the government’s COVID-19 guidelines and policies with colleagues and

YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW 7

“ ”

Results demonstrated that the healthcare worker groupdoctors, nurses, healthcare administrators - showed the most significant mental strain due to the pandmic.

decide on how to proceed. Along with the health administrators organizing them all into the COVID-19 ward, they have to juggle all the problems while simultaneously acquiring new skills with speed. In an interview conducted on February 13, 2020, a physician in Hubei province, specialized in oncology, said: “I have to treat patients who are not in my specialty…it is an unknown disease and everyone feels powerless.” 8 Some teams even included healthcare workers from other provinces; this diverse and multidisciplinary team had to find ways to collaborate and communicate effectively and quickly.

Moreover, a study showed that 34 percent of healthcare workers experienced insomnia. 9 In Wuhan versus not in Wuhan, frontline versus second line, and secondary hospital versus tertiary hospital, medical workers in the former were more susceptible to anxiety and insomnia. 10 Unusual sleep patterns are a standalone risk factor for suicidal thoughts, attempts, and death. 11 A 37-year-old Japanese health worker who managed isolated returnees from Wuhan, China was reported to have committed suicide.12

Teachers and Students

With strict guidelines regarding school reopening after the winter holiday, most

schools opted for online learning. The extensive period lacking physical interaction has challenged adolescent and young adult’s mental strength. Although remaining home appears as a scarce opportunity to spend time with family, the limitations may outweigh the bene-

fits. Physical education classes have been canceled, or the possibilities restricted. Sporting facilities are closed and remain such until governments authorize the openings. Exercise has long been considered a potential remedy for sleep disorders such as insomnia and a vital maintainer of sleep patterns. Improved fitness from aerobic endurance activities and hour-long acute exercises have been proven to be most beneficial.

Moreover, with students managing their upcoming examinations and applications, it is not easy with teachers spread across the globe; sleep adjustments must be made. A faculty of Sports Science indicated that earlier wakes were required to ensure no students were falling behind. A ninth-year student commented that communication barriers developed with peers and teachers in other countries; another exclaimed that

her “social life has been disturbed!”. If the sudden transition to remote operations was not frustrating enough, students faced the reality of exam cancellation. Final examinations have been canceled by many organizations, including the International Baccalaureate Organisation (IBDP), Cambridge International Education (CIE), Pearson, and College Board, etc. This has left the student panicking, fearing postponement and grade prediction complications. 13

Enterprise and Institution Workers

Unemployment in the U.S. is rising towards unprecedented levels since the Great Depression. And the uncertainty drifting through the news is contributing to anxiety levels. Data released by the International Labour Organisation on March 18, 2020, declared a decline of 24.7 million jobs and 5.3 million jobs, as the high and low scenario, respectively. Suicide is also closely linked with unemployment, as the lack of secure income creates emotional and physical vulnerabilities.

Conclusion

The focus of the news on the transmission of the virus within various countries in the world has diverted attention from the equally demanding psychological aspect of the pandemic that may translate into long-term ramifications. A holistic response should contain physiological and psychosocial information and resources for the affected and the general population. Researchers should continue their work on COVID-19’s effect on several components of mental health, identifying additional measures to address pandemic related psychosocial issues while maintaining consistent effort to counteract the physical spread of the virus.

Mika Yokota of Japanese nationality now lives in Beijing, China, and is a high school student at Dulwich College Beijing. She hopes to major in life sciences at university. Flickr

8 VOLUME 8, NO. 1

www

“ ”

Suicide is also closely linked with unemployment, as the lack of secure income creates emotional and physical vulnerabilities.

Healthcare workers juggle the challenges of the pandemic as well as mental health struggles.

By Sophia De Olivera

The Unlikely

Rise of an Unlikely Public

Health Ally Brazilian Drug Cartels

Michelle Foley

Michelle Foley

As I peered outside the window of a bus shuttling me to my grandmother’s house from the Rio International Airport, I found myself exceedingly curious about the towering multicolored slums decorating the outskirts of the Brazilian city. These vast stretches of impoverished housing, known as Favelas, were unlike anything I’d ever seen in the developed world. Although I was inquisitive about what life looked like inside these vast stretches of informal settlements, my parents strongly advised me against familiarizing myself with Favelas since I was a child. My extensive Brazilian family was conscious of the dangers housed in Favelas; these government-neglected neighborhoods, although not inherently dangerous, are known to house pockets riddled with the gruesome gang and drug violence that make Favelas incredibly inhospitable toward outsiders. However, the Coronavirus pandemic ravaging the world since late 2019 has painted the culture of Favelas in an extraordinarily different light. Against a government neglecting the dangers of Coronavirus, drug trafficking gangs in Brazilian Favelas have emerged as an unlikely proponent of public health and safety.

Brazil has been one of the hardest-hit countries by the Coronavirus, reporting over 7 million cases and 186,356 deaths.1 These staggering numbers are likely significantly less than the real values due to the underreporting of Coronavirus cases in Favelas and rural areas. Since the onset of the Coronavirus outbreak in Brazil, Brazilian President Jair

Bolsonaro’s response has reaffirmed his ineptitude to effectively respond to a health crisis of this magnitude, from antagonizing his health minister to promoting resistance towards public safety measures.

Consequently, distrust towards the Brazilian healthcare system and the presidential cabinet has gained widespread prominence among the general Brazilian public. A young gang member from a Rio Favela showcases this omnipresent distrust by declaring that “the hospitals kill more than if you stay home and take care of yourself.” 2 This distrust is rooted in the corruption of the Brazilian public health

between governmental promise and action has been exasperated by the Coronavirus pandemic that has similarly exposed several other fallacies in the Brazilian public health system, some of which have proven to cost hundreds of thousands of lives so far. Such fallacies have proven most deadly to the 15 million Favela residents, who are commonly poor, burdened with chronic illness, situated far from adequate hospital service, and live in extremely close quarters.

Void of adequate help from the state, drug cartels in Favelas responded by stepping up and taking the health and safety of their community into their own hands by establishing curfews, social distancing laws, and delivering food to those in need. Even before the Coronavirus pandemic, these drug cartels, heavily armed with semi-automatic rifles, such as AR-15s, M4s, Glock pistols, rifles, and sometimes even grenades, maintained strict control over Favelas by guarding the area against police and rival gangs. In the absence of government involvement and the Favelas’ known immunity to authorities, drug cartels institute and enforce social contracts within their own Favelas. In doing so, drug cartels establish themselves as providers for their respective Favela. Once the Coronavirus pandemic hit, drug cartels maintained the role of provider by quickly educating themselves about the Coronavirus and public health safety measures in order to protect their communities. Most prominently, the efforts of Favela drug cartels to promote public safety have manifested in strict curfews.

system, Sistema Unico de Saude (Single Health System). The Brazilian constitution famously states that “health is a universal right and a duty of the state”; however, a 2019 report by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development discovered Brazil’s per-capita health care spending to be thirty percent below the average for developed countries, classifying it among the countries contributing the least to public health.3 This dichotomy

A viral video of the Comando Vermelho (Red Command) gang leaders in the famous Cidade de Deus (City of God) Favela showcases a gang member with a loudspeaker broadcasting a recorded message to residents: “Anyone found messing or walking around outside will be punished.” Such curfew has also extended to bars, restaurants, and even churches, as drug cartels have ordered many businesses and institutions to promptly decrease operating hours. The efficacy of a

YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW 11

Favela des Plaisirs in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Flickr

“

”

Against a government neglecting the dangers of Coronavirus, drug trafficking gangs in Brazilian Favelas have emerged as an unlikely proponent of public health and safety.

Coronavirus curfew has proved effective as residents, fearing death due to violating curfew, have left Favela streets relatively quiet and void of the normal lively humming of music and camaraderie between residents. A decrease in social interaction between residents has greatly mitigated the spread of the deadly virus in these settlements. In turn, many other of Rio De Janeiro’s 1,000 Favelas instituted curfews in an effort to hinder the spread of Coronavirus among its residents.

Additionally, drug cartels across hundreds of Favelas have distributed soap and bottles of hand sanitizer to residents, placed several large posters around their Favelas, and ordered residents through social media posts and megaphones atop moving cars to practice good hygiene. These measures are especially important because the typical Favela often has no standard for sanitation due to forced closed living quarters and inadequate access to running water.4

One Favela resident explains that those who live at the top of the hill (Favelas are often situated on hillsides) often don’t receive running water for two weeks. Favela drug cartels have prioritized the delivery of hand sanitizer and other alcohol-based disinfectant products to these residents in recognition of their lack of access to water. Likewise, drug cartels have placed large posters and published social media announcements

concerning hygiene in an effort to hinder the introduction of Coronavirus into Favelas by outsiders. Drug cartels have strategically positioned large posters reminding individuals to wash their hands at the Favela boundaries, where they hope to remind incoming visitors, who are often in search of drugs, to practice good hygiene.

Favela drug cartels have also contributed to their communities’ health and safety in several other remarkable manners. First, of prominence, is the distribution of groceries to Favela residents. During a CNN visit to an undisclosed Favela, reporters described seeing drug cartels gifting groceries to Favela residents who have been hardest hit by the pandemic.1 One package of groceries was given to a manicurist in the Favela, who is reported to have been out of work for four months; the second package was gifted to a street vendor who has experi-

Coronavirus and systemic governmental neglect have helped protect the lives of the 15 million Brazilians that call Favelas home.

enced great difficulty selling her products. Second, several drug cartels have transformed their Favelas into major local manufacturers of face masks and sick wards, where they have begun massively distributing face masks and housing COVID-19 carriers. Third, Favelas have notably organized ambulances, equipped with physicians and first-responders, to respond to local emergencies after the failure of adequate municipal government aid.5

Throughout the entirety of the pandemic thus far, drug cartels have famously stated that if the Brazilian government does not have the capacity to fix the suffering caused by the pandemic, organized crime will solve it. Through the imposition of curfews, social distancing measures, hygiene, and food delivery, Favela drug cartels have accomplished exactly that. The notable efforts of drug cartels in fighting back against the

As I get ready to return to Brazil after the end of the global pandemic, I am ever more intrigued by the Favelas that decorate the city I call my second home. Peering outside my window, I’ll no longer simply see Favelas as vast stretches of informal settlements, but strong, independent, and resilient self-governing entities. Similarly, I’ll no longer unconsciously consume the narrative of Favelas as unkempt and unruly, but, rather, I’ll challenge it. Despite being an unlikely ally for public health and safety, Brazilian drug cartels have accomplished what many worldwide argue the Brazilian government was incapable of doing. With the least amount of medical and governmental aid, social structure, and the worst living conditions, the perseverance of Favelas throughout this pandemic has been an extraordinary feat and has served as a model for many other social entities. Perhaps, most importantly, Brazilian Favelas’ unity has proven that the most essential thing in fighting this pandemic is community solidarity. ■

12 VOLUME 8, NO. 1

www

Sophia De Oliveira is a freshman in Morse College. Sophia is a prospective Sociology major from Wisconsin. She can be contacted at sophia. deoliveira@yale.edu.

Depiction of close unsanitary living quarters and streets littered with trash in Favela da Rocinha

Flickr

“ ”

If the Brazilian government does not have the capacity to fix the suffering caused by the pandemic, organized crime will solve it.

Flickr

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has repeatedly downplayed the gravity of the Coronavirus pandemic.

Why is Our Genome Data So White?

A Discussion on the Lack of Representation in Genome-Wide Association Studies

By Ann-Marie Abunyewa

The public health research consensus is that predominantly social and economic factors contribute to the health disparities observed in the United States. The determinants that contribute the least to health disparities are biology and genetics, which is understandable, as all humans share roughly 99.9% of DNA, and access to quality healthcare and a healthier lifestyle is not governed by our DNA but by environmental factors. However, with growing revolutionary fields like pharmacogenomics and precision medicine, which promise to use genetic information to further personalize healthcare towards the individ -

ual, the fact that the vast majority of genetic databases contain information from individuals of European descent does not necessarily guarantee similar benefits for underrepresented communities. In order to maintain the status that genetics is not a significant determinant of health, it is absolutely necessary that the genetics community eliminate its severe bias towards the European community and increase the number of participants from underrepresented populations in genomewide association studies. Otherwise, this lack of representation can in fact exacerbate health disparities.

Malia Kuo

The field of genetics acknowledges that the vast majority of participants in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are those of European descent. In a 2009 analysis, about 96% of participants in GWAS were of European descent.1 As of 2018, this number has lowered to about 78% with the increasing representation of participants of Asian descent in GWAS, but the number of participants of African, Hispanic/Latin American, and/or Native American descent has remained low.2 Participants of African descent made up about 2% of GWAS, participants of Hispanic or Latin American descent made up approximately 1%, and participants of Greater Middle Eastern, Native American, or Oceanian descent made up <1%.2 A 2017 study by Johnson et al. has identified the consequences of this discrepancy in the field of pharmacogenetics. They found that for participants of European descent, short nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in three genes account for between 11 and 30% of variance in drug metabolism of warfarin, the most prescribed oral anticoagulant in the

world.2 Meanwhile, for participants of African descent, SNPs account for a significantly smaller percentage of variance, thus claiming that “the algorithms derived from Europeans do not translate into better and safer treatment

research. These provide further insight into what protocols researchers need to prioritize in order to improve the representation of minorities in genomics research.

across ethnic groups.”2 Many researchers recognize that it should be a priority to have more representation in genomics studies, and this understanding has reached mainstream media in the past couple of years. However, it is important to recognize some of the reasons for which certain populations are severely underrepresented in genetics

There is no doubt that the history of genetics has been rather hideous: the field has been used as a tool to justify and perpetuate bigotry, racism, and supremacy over others. The story of Henrietta Lacks, whose “immortal” cancer cells underpin key developments in molecular medicine, and the story of Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey, whose subjugation to experimentation

14 VOLUME 8, NO. 1

“ ”

With cases like these depicting the history of medical science, it is understandable why many members of underrepresented communities are more hesitant to participate: they do not want to be the next “guinea pig” that scientists can exploit for recognition, financial gain, or perpetuation of racist ideologies and agendas.

Cell

A distribution of ancestry categories. On the left is the distribution of ancestries represented in studies. On the right is the distribution of all individuals represented in GWAS studies.

allowed for James Marion Sims to become the so-called “Father of Modern Gynecology,” both highlight instances of a lack of informed consent. In each case, the scientists profited not only financially, but also in the form of recognition, at the expense of African Americans and enslaved people.3, 4 The Guatemala and Tuskegee experiments (where scientists had knowingly injected a combined total of over 5,600 people with sexually transmitted diseases) and Havasupai tribe case (where DNA samples were kept to investigate mental illnesses and theories on geographical origins that contradicted traditional stories) also share the common denominator of exploitation and lack of informed consent.5, 6, 7 With cases like these depicting the history of medical science, it is understandable why many members of underrepresented communities are more hesitant to participate: they do not

2018 — it became clear that it had not been a priority of many granting bodies to fulfill that mandate. Epidemiologist Esteban Burchard of the University of California San Francisco says that the delayed GWAS diversification comes from “a system that distributes accountability across multiple scientific committees, leaving no one truly responsible for ensuring improvement.”9 Yet, he also remarks that, given that the vast majority of scientists are of European descent and that granting bodies are made up of scientists that have received grants themselves, “The scientists that are reviewing the grants are primarily white males. They’ll say, ‘This is my friend. He’s white, trying to get blacks, and he can’t do it. Let’s give him a pass.’”9 Burchard was denied funding for an asthma study on African American children by these granting bodies and instead had to seek out private donations,9 even though these same granting bodies have established mandates to diversify study populations decades before.

want to be the next “guinea pig” that scientists can exploit for recognition, financial gain, or perpetuation of racist ideologies and agendas. This history has thus compromised the chance of an overall positive relationship between underrepresented communities and the scientific community.

Still, it is not only due to a lack of trust among these marginalized communities that certain populations are understudied, as indicated by further underlying complexities. One factor that plays a role in the disparity among representation of participants from different ethnic communities originates from the institutional bodies that allocate grants towards scientists conducting GWAS. A 2011 Nature article stated that a mandate to include more participants from minority backgrounds was issued in 1985.8 Thus, when it was revealed that twenty-four years later only 4% of GWAS studies included individuals from non-European backgrounds8 — later increased to a whopping 7% in 2011, and eventually 22% in

Some researchers who have conducted diverse genomics research and clinical trials suggest that the studies themselves are not putting in enough effort to be inclusive. A 2005 study by Wendler et al. conducted a comprehensive literature search and found a total of 20 health research studies conducted in the United States (representing over 70,000 people) that had published consent rates to research by ethnicity. They had uncovered that those studies on average did not have significant differences in consent rate between different ethnicity groups, but there were significant differences in enrollment rates between studies.10 Their data suggest that it is not necessarily an attitude towards research that is affecting participation (as the consent rates are quite similar), but rather knowledge of the studies that are occurring and access to their sites.10 This suggests a much larger focus on identifying what factors may contribute to this disparity in recruitment, such as travel expenses and language barriers — in other words, factors can be addressed by the researchers themselves, not the people they are trying to recruit.

The All of Us program aims to recruit 1 million participants research, 80% of which are from historically underrepresented

With these reasons in mind, protocols to improve participation are actions that can be accomplished both in the present and future. The most promising way to increase trust among marginalized communities is to increase minority representation in science, medicine, and public health. It becomes much more empowering for a patient from a marginalized group to see a scientist of a similar background occupy a space that holds such a complicated relationship with marginalized communities; a sense of trust can be established. Significantly increasing representation in these fields will take several years, meaning that a long-term effort will be required to overcome barriers of entry to dramatically increase trust. Nonetheless, there are actions that researchers can

YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW 15

“ ”

When it was revealed that twenty-four years later only 4% of GWAS studies included individuals from non-European backgrounds,8 it became clear that it had not been a priority of many granting bodies to fulfill that mandate.

accomplish right now in order to improve participation in studies and the general relationship between the scientific community and these marginalized communities.

Jocelyn Ashford, a patient advocate for biotech company Eidos Therapeutics, offers how she invites African Americans in clinical trials that benefit their communities:

“I’ve found that one of the first and most important steps to creating an inclusive

clinical trial is to engage the target community in discussions around the recruitment plan. By bringing these communities to the table early, we can hear their input instead of making assumptions about how to best reach them. We can hear their concerns and attempt to address them, while educating the communities about the importance of clinical trials, all that’s involved, and the potential to bring high-quality care to their community.”11

She emphasizes building a positive relationship between the researcher and the participant, one that is not only focused on

increasing the number of studies with strong minority representation, but also doing so in an ethical manner that respects the concerns of the participants.

Moreover, it is important to recognize and amplify the efforts that have been implemented to address this extreme disparity in representation. For instance, the National Institute of Health’s “All of Us” research program aims to recruit a diverse group of at least one million United States participants to provide more comprehensive phenotype and genotype data. Enrollment opened in May 2018, and as of July 2019, more than 175,000 participants had volunteered their biospecimens for research; moreover, about 80% are from historically underrepresented communities. The All of Us research program investigators also emphasize the importance of ensuring that participants are engaging in a positive relationship between the participant and the researcher, specifically regarding privacy for the participants:

“Establishing authentic engagement with participants and providing value for them will be key to long-term retention and continued recruitment of persons from diverse populations. The All of Us program must resist cyberattacks and effectively communicate the legal and procedural protections of privacy such as those afforded by the 21st Century Cures Act.”12

The All of Us research program investigators estimate that they will reach their target participant size by 2024.12

When analyzing this historical perspective in relation to contemporary innovations, although there is not much that science can do to change its past, there is more than enough room to build a positive relationship it has with underrepresented groups for the present and the future. It will hopefully only be a short amount of time before representation across genomic studies better reflects and better serves the populations that have been neglected and mistreated for so long.

Ann-Marie Abunyewa is a first-year in Branford College. She is a prospective double major in Classics and Ecology & Evolutionary Biology. She may be contacted at ann-marie.abunyewa@yale.edu.

16 VOLUME 8, NO. 1

www

The most promising way to increase trust among marginalized communities is to increase minority representation in science, medicine, and public health.

“ ”

participants and has already recruited over 175,000 participants who have volunteered their biospecimens for underrepresented communities. (Sketchify on Canva)

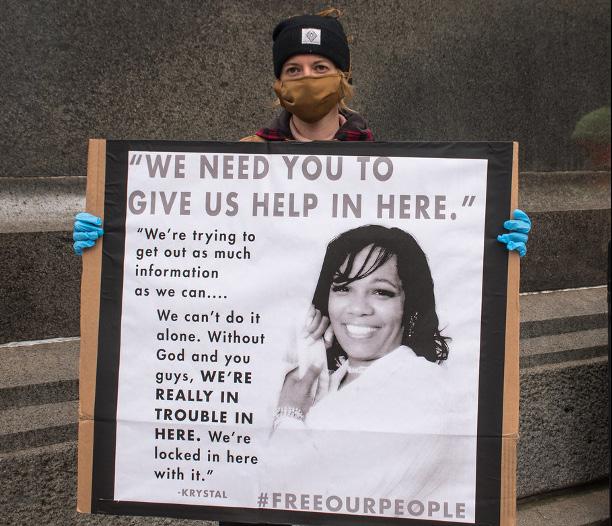

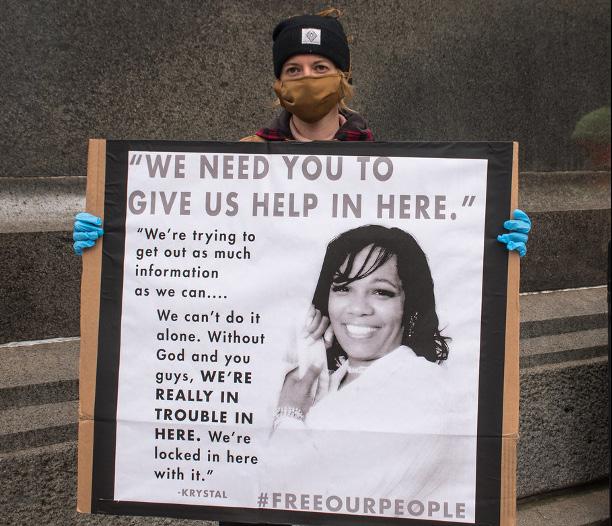

Mass Incarceration and COVID-19

Faced with the looming coronavirus threat, governments around the globe have employed a number of strategies to curb the spread of COVID19. As prisons have emerged as a hotbed for coronavirus, one of the strategies has included attempts to reduce prison populations through methods such as early release and reduced admissions.1 By their very nature, prisons pose a multifaceted challenge in the face of the uncontrolled spread of an airborne virus. Widespread issues such as overcrowding, lack of testing, and diminishing resources make it impossible for incarcerated individuals to adhere to international COVID-19

guidelines, including quarantine protocols, social distancing, and mask-wearing. With more than 10.35 million people incarcerated worldwide, wide variations in international governmental responses to COVID-19 in prisons and jails have led to a range of consequential outcomes.2 Global data paints a consistently bleak picture of the coronavirus crisis in prisons and jails around the world, drawing stark attention to the reality of mass incarceration as a dangerous public health crisis with vast repercussions beyond the current pandemic.

Brazil hosts the third-largest prison population in the world with over 750,000

incarcerated people, many of whom have yet to face their first trial.3 Official data from Brazil’s government is largely unsatisfactory; as of July, there were 66 officially reported COVID-19 related deaths in prisons, but it was estimated that only 3.2% of the incarcerated population in Brazil had been tested for COVID-19.3 Some academics have also warned that official government data is untrustworthy, casting doubt on the methods by which the data is being collected and pointing to a likely vast underestimation of COVID-19 impact in prisons.3 These factors reflect a culture of brazen denial at the highest levels of the Brazilian government, led by Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, who has

YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW 17

Incarceration COVID-19

By Amma Otchere

By Amma Otchere

dismissed COVID-19 as nothing more than a “little flu.”4 This hands-off policy has contributed to Brazil having the second-highest number of COVID19 deaths in the world,4 and the situation in Brazil’s prisons has grown direr in response. Prisons are characterized as “porous institutions,” which means that not only are incarcerated Brazilians vulnerable to the coronavirus crisis occurring outside prison walls, but the

unchecked spread of coronavirus within prisons also poses a threat to surrounding communities.3 Furthermore, lack of testing

Brazil, leading to riots and attempted jailbreaks which have served only to worsen the spread of COVID-19 in Brazilian prisons.3

capacity and widespread distrust have sowed deep unrest among incarcerated people in

South Africa has a prison population of over 130,000 and a prison overcrowding rate of 14 percent, posing an obstacle to curbing the spread of coronavirus.5 South African president Cyril Rhamposa ordered the release of incarcerated people classified as “low-risk” in an effort to address overcrowding.5 However,

18 VOLUME 8, NO. 1

“ ”

Widespread issues such as overcrowding, lack of testing, and diminishing resources make it impossible for incarcerated individuals to adhere to international COVID-19 guidelines, including quarantine protocols, social distancing, and mask-wearing.

FreeIMG

the sporadic nature of these releases has left thousands of incarcerated people facing abysmal and unsanitary conditions without any avenue to protect themselves from contracting coronavirus. Several incarcerated South Africans have reported widespread shortages of essential supplies, including food and hygiene products like soap.5 Furthermore, they have reported the emotional toll of witnessing the deaths of other imprisoned people from coronavirus, some of whom are their cellmates or are housed on the same floor.5 Pervasive fear and anxiety coupled with feelings of isolation since the suspension of familial visits in September have only led to increased feelings of hopelessness as cases begin to rise again in South Africa. However, the South African government has largely cast these accounts from incarcerated people as overstated and misrepresentative of the COVID-19 situation in South African prisons and insists that it has taken adequate measures to address the spread of COVID-19.5

Home to the largest incarcerated population globally, the United States presents perhaps the most extreme case of nearly

increased transmission risks in densely confined prison conditions; the case rate in US prisons and jails is 5.5 times that of the gen-

unchecked spread of COVID-19 among its imprisoned populace.6 90 out of 100 of the largest cluster spreading events in the United States have occurred in prisons and jails,7 with recent data indicating that there have been over 190,000 COVID-19 cases and nearly 1,500 deaths in US prisons since the start of the pandemic.8 The data also indicates a disproportionate toll of the disease on the prison population, likely due to the high prevalence of underlying medical conditions and the

eral population and the death rate is over 2 times as high.6 The United States prison population also represents another vast inequality: African Americans are imprisoned at a rate almost four times as high as their white counterparts.9 With reported data demonstrating a disproportionate coronavirus disease burden in African American communities--Black Americans have an infection rate of 62 per 10,000 people compared to 23 per 10,000 among white Americans10--COVID-19 has uncovered a broader issue of deep health inequity among marginalized populations in the United States. Mass incarceration is a contributing factor to this vast inequality, reflecting the structural and institutional policies that influence the spread of coronavirus among marginalized groups worldwide.

In New Zealand, mass incarceration of indigenous Maori peoples has led to a disproportionate coronavirus disease burden among this marginalized population. 51% of New Zealand’s prison population is Maori, despite the fact that Maori peoples make up only 15% of the total New Zealand population.11 Though New Zealand as a whole has boasted extremely low relative rates of COVID-19 infection, Maori activists and advocates have urged a swift governmental response to their concerns about rates of coronavirus among imprisoned Maori peoples, especially among the growing number of incarcerated youth. They cite disproportionate levels of comorbidities and other underlying health issues among the incarcerated Maori population that pose a heightened risk for serious health consequences and even death caused by COVID-19 exposure.11 The dangerous conditions in many New Zealand prisons, including crowding and poor healthcare access, have led to a call for governmental compliance with several urgent demands, including immediate decarceration and reform of carceral policies unequally applied to indigenous people in New Zealand.1

YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW 19

Lack of access to crucial medical care has exacerbated the devastation of COVID-19 in prisons.

Joe Pietto/Flickr

“ ”

Global data paints a consistently bleak picture of the coronavirus crisis in prisons and jails around the world, drawing stark attention to the reality of mass incarceration as a dangerous public health crisis with vast repercussions.

The South Korean government’s handling of COVID-19 among its prison population may present potential lessons for other nations whose incarcerated populations are reeling from the disease. South Korean prisons have significantly increased their testing capacity with the installation of “walk through testing booths” and have embarked on a concerted effort to distribute masks across the entire prison population. 7 They have followed a strict set of guidelines, including the required quarantine of each person who tests positive for coronavirus or is newly admitted to prison. 7 Additionally, masks are mandated to be worn at all times, and gatherings in common areas are greatly restricted. 7 Though the ability of South Korean prisons to follow these guidelines is likely due to its relatively small prison population--a little over 50,000 incarcerated South Koreans as of June 2020--it is clear that nations around the world can adapt some of these strategies to address the immediate crisis of coronavirus spread in prisons and jails. 12

The disproportionate effects of coronavirus amongst prison populations worldwide reflect the larger global issue of public health and incarceration. Though the decarceration efforts employed by several governments worldwide play an important role in reduc-

ing the spread of coronavirus among prison populations, temporary reductions to prison populations are only short-term solutions. Beyond the acute consequences of the current pandemic, global governments must seek long-term solutions to the public health risks

posed by mass incarceration. Incarceration is a “major social determinant of health,” with consequences that extend beyond the incarcerated individual to affect their families and communities.6 Furthermore, incarceration rates in many countries reflect the systemic discrimination of vulnerable populations, further contributing to their marginalization. Public health practitioners and organizations, including the American Public Health Association, have urged for the complete abolition of carceral institutions as we know them.11 They have called upon governments to create new institutions that will centralize restorative justice and public health to address the injustices perpetuated by the current justice system.6 As the pandemic continues to devastate nations across the globe, it is clear that there must be an international reckoning with the public health consequences of mass incarceration.

Amma Otchere is a sophomore in Davenport majoring in Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology. She can be contacted at amma. otchere@yale.edu.

20 VOLUME 8, NO. 1

www Flickr

“ ”

Beyond the acute consequences of the current pandemic, global governments must seek long-term solutions to the public health risks posed by mass incarceration

Protesters in Philadelphia take to the streets to demand decarceration.

The Uighur Cultural and Ethnic Genocide in 2021

Understanding Humanitarian Crises Through the Lens of a Continuing Pandemic

By Sherry Chen

What happens when a humanitarian crisis overlaps with a global pandemic? Uighurs living in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XUAR) are met face-to-face with this issue on a daily basis. The Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) was an American counterterrorism effort, initiated by President George W. Bush in response to the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center1. Since then, China has used the GWOT as justification for its rampant settler colonialism. It has implicated the Uighurs—Turkic ethnic minorities native to the XUAR—in the fight against terrorism. However, what the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) disguises as counterterrorism methods is, in fact, cultural and ethnic genocide.

For context, Uighurs in the XUAR undergo intrusive surveillance from the CCP, are forbidden from practicing their religion in the public and private spheres, and are forcibly assimilated into Han Chinese society—wiping the Uighur culture and language that once pervaded every corner of the XUAR. Now, even Kashgar, a rural area in the south of the XUAR that has held its Uighur culture intact for centuries, has abided by the CCP’s policies and forced assimilation. The Uighurs had no choice. After all, disobedience to the CCP in any capacity is met with strict punishment: long-term internment or imprisonment, and sometimes both2

The health implications of the Uighur genocide must be addressed immediately. Unknown injectable medications are administered to Uighur internees; several women from these internment camps have reported that these were forced sterilization methods. A former detainee, Tursunay Zi -

yawudun, reports that these injections caused her to stop having her period. Additionally, due to physical abuse inflicted by internment camp employees during interrogations, she frequently bleeds from her womb and is now physically incapable of bearing children. Additionally, several Uighur women were forcibly fitted with intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUDs) 3 . As a result of these inhumane efforts at eugenics, birth rates in the mostly Uighur majority regions of Hotan and Kashgar have declined 60 percent from 2015 to 2018 3 . This is a direct ethnic erasure, revisiting the unethical and grossly dehumanifying programs of eugenics prevalent during the Holocaust 4

On top of these already existing health threats facing the Uighurs, the COVID-19 pandemic has ravaged international communities, since the initial COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China.

As of January 23rd, several COVID-19

infections have been reported in the XUAR. In particular, waves of cases surged from mid-July to mid-August and again, from late October to early November5. However, it is difficult to gauge the extent of the COVID-19 outbreak in the XUAR, due to a suspected inaccuracy in case reporting by the CCP.

Though the exact number of currently interned Uighurs is unclear, the XUAR Uighur internment camps have detained somewhere between a million and three million people since the CCP’s crackdown on the Uighurs in 2017 6 . The internment camp’s gruesome conditions, forced community activities, and collective labor are bound to facilitate community-wide

21 YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW

On March 13, 2019, the United States co-hosted an event with Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom at the UN in Geneva to raise awareness about ongoing human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Participants discussed future actions international communities could consider to initiative ahead of protecting fundamental freedoms in Xinjiang. (Flickr, U.S. Mission Photo / Eric Bridiers)

spread, especially when so many people are detained with such limited spatial capacity. While the World Health Organization recommends that people maintain a 1 meter—or three feet—distance, this health regulation becomes more difficult to enforce with higher population densities 7,8 . In 2019, Mihrigul Tursun, another former Uighur detainee at a state-run internment camp, claimed that each of the camp’s cells was approximately 430 square feet and held about 60 women 9 . Therefore, with the camps’ high population density, internees are more susceptible to COVID-19 community spread.

While the World Health Organization recommends that people maintain a 1 meter—or three feet—distance, this health regulation becomes more difficult to enforce with higher population densities 7,8 . In 2019, Mihrigul Tursun, a former Uighur detainee at a staterun internment camp, claimed that each of the camp’s cells was approximately 430 square feet and held about 60 women 9 .

Additionally, the children of detainees are kept in state facilitated orphanages. It is reported, as of 2019, that “[a] total of 880,500 children–including those whose parents are absent for other reasons–were living in boarding facilities by 2019” 10 . Though it is also unclear how many Uighur children are currently being kept at these orphanages during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is known that each facility contains a minimum of 100 beds 11 . Thus, community spread is also a high risk among Uighur children.

In the case that Uighur detainees or their children do end up contracting the disease, quarantine facilities and hospitals are not readily accessible. The ones that are open to Uighurs are cramped.

To further exacerbate this issue, Uighurs—especially Uighur women—live in a fear of state-run medical facilities. Historically, state-provided care has resulted in mass forced sterilization of Uighur women. Additionally, most doctors are of Han Chinese descent, which may disincentivize Uighurs from receiving care due to the long history of violence and tension between the Han Chinese and the Uighurs, which traces back to the early 20th century 4

Though the CCP claimed that all of the Uighur detainees in the internment camps were released in December

2019—right at the onset of the community spread of COVID-19—there exists limited evidence to support this claim. Additionally, because no human rights organizations and media outlets have access to these camps, the true condition of these internment camps—especially during the pandemic—is unclear. However, we can safely assume that any form of community spread would ravage these camps.

Dr. Anna Hayes, senior lecturer in international relations at James Cook University, who specializes in Uighur human insecurity in the People’s Republic of China, confirms the tendency for secrecy among CCP officials about public health crises.

“I doubt we would ever know,” she said, referring to the publicization of outbreaks within the internment camps. “But [we know] there is community transmission, it’s only a matter of time, if it hasn’t happened already,” she added [12].

We must demand justice for the Uighurs living in the XUAR, to combat these concurrent and dual crises. China must immediately release the Uighur detainees to their homes. The international community must hold the CCP accountable. An immediate first step is to call for the International Criminal Court to prosecute China in mass cultural and ethnic genocide. We cannot wait for the deaths of Uighur internees from COVID-19 to act.

Sherry Chen is a first-year in Pierson majoring in Political Science. She may be contacted at sherry.chen@yale.edu

VOLUME 8, NO. 1 22

www

“ ”

On Average, What People Think About Covid-19 Responses, and the New Vaccine

By Ryan Bose-Roy

With 317,800 Covid-19 deaths in the United States and 1.7 million deaths worldwide, the recent emergence of suitable Covid-19 vaccine candidates is a refreshing sight. However, vaccine availability is just a stepping-stone to the end goal; public opinion of the pandemic response and trust in the vaccine are crucial for adequate coverage and for reducing viral spread1. Since more than one million travelers per day are passing through American airport security checkpoints for Christmas and New Year’s, understanding how perceptions of Covid-19 and its vaccines differ across countries and regions, as well as what motivates these perceptions, is paramount in making safe decisions2

At this time of writing (December 21, 2020), roughly six million doses of Moderna’s newly authorized mRNA-1273 vaccine are being shipped to more than 3,700 locations across the country, adding to the three million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine dispatched mostly to american health care workers the week prior2. On December 21st, this vaccine became the first one au-

thorized in the European Union, with the European Commission concluding “that it is safe and effective against Covid-19.”3 Roughly 500,000 people have been vaccinated in the United Kingdom, and adding the vaccinations authorized by China and Russia—administered in July and August before being fully tested—over two million people in the U.S., UK, Russia, Israel, China, and Canada have been treated4

Several caveats exist alongside these promising numbers. Firstly, reports of Russia’s “Sputnik V” vaccine, despite claiming a 92 percent success rate, covered just 20 total Covid-19 cases in vaccinated and placebo groups and faces skepticism from analysts inside and outside the country. A study conducted by the Russian Levada Center in October showed that even if it was offered for free, 59 percent of Russians were unwilling to get the vaccine5.

Secondly, newly emerged viral mutants in Britain and South Africa, predicted by modeling to be 70 percent more transmissible than the current strain, will likely

alter vaccine distribution due to lockdown-induced fears. Hong Kong, Canada, India, Iran, Argentina, Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Russia have all imposed travel restrictions on Britain; Israel has closed its skies to foreign nationals and Saudi Arabia has instituted a one week ban on all international travel 6,7. Although the new variant likely does not cause any more serious illness than the existing strain, growing alarm over the virus and the shock of financial markets may likely delay efforts to administer vaccines in order to meet the pressing demands of maintaining order and ensuring international trade continues.

Thirdly, although roughly two million people have been treated across six coun -

23 YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW

tries, success seems ambiguous for hardhit nations where distribution hasn’t started. According to CNN, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s plan to administer the first doses to 300 million people by August is highly ambitious given India’s “poor rural infrastructure and inadequate public health system that is already buckling under tremendous pressure from the coronavirus.” 8 . Nevertheless, it is worth noting that India is the lead producer of vaccines worldwide— in addition to the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, India is manufacturing its own vaccines, Covishield and Covaxin, locally through its already-established mass vaccine production lines. However, nations without existing infrastructure have to rely on international sales;

here, competition and politics dominate distribution. The 27 member states of the European Union, together with five other wealthy countries, have already pre-ordered half of the existing vaccine

candidates 9 . These countries amount to just 13 percent of the global population 9 , leaving dwindling supplies for low- and middle-income nations. And even if vaccines were made accessible to countries, misleading federal efforts and inappropriate interventions may prevent treatment until it is too late 10

Faced with a bevy of complications, from vaccine skepticism to national and international politics, how do people across the world view the coronavirus? How do they view efforts to curtail the spread of the coronavirus? Do views of their own government’s efforts differ from their views of the international community? Do people in different countries have different views?

As reports of Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness become more promising, American public confidence in the vaccine appears to in-

VOLUME 8, NO. 1 24

”

Sarah Teng

“

Politics has interfered with science and public health too many times during this pandemic

crease; nevertheless, concerns about rushing vaccination are still widespread. In September, nearly 50 percent of American adults said that they were willing to take a vaccine11; as of December 14, that number rose to more than 80 percent12. While 40 percent said that they would take it as soon as possible, 44 percent said that they would wait before getting it12 This caution seems not to be due to concerns about vaccines in general, but instead primarily due to concerns about the politicization of the vaccine and the potential for being overly optimistic. A poll released in October by the Kaiser Family Foundation suggested that Americans were more skeptical about a rushed vaccine than an effective one: 62 percent of adults stated concerns over the Trump administration pressuring the Food and Drug Administration to approve a coronavirus vaccine before the election13. Those who

million people in the world, it is perhaps understandable that many people are frustrated, cautious, and slightly optimistic. Dr. Susan Bailey, president of the American Medical Association, suggests that it’s only natural for people to be suspicious of what they don’t know. Former acting director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Richard Besser, continues that “politics has interfered with science and public health too many times during this pandemic,” and has as a result led to a deep erosion of trust15

Citizens of other countries also give the United States a poor grade for its handling of Covid-19. A poll conducted by Pew Research Center, released in September, found that across 13 countries (Canda, Denmark, Belgium, Netherlands, France,

ongoing survey conducted at 11 universities across the world, including at MIT, Princeton, Oxford, and Harvard, currently holds that on average in 58 countries, people hold pessimistic views about their fellow citizens’ response to the pandemic. 93 percent of respondents believe that social gatherings should be cancelled, yet they estimate that only 67 percent of their fellow citizens think the same thing17. These views suggest that people hold strong beliefs about the importance of avoidance, but do not show confidence in the nation’s ability to uphold them.

stated that they were not planning to get a vaccine believed that they needed it, but were concerned because they wanted to know more about its efficacy and side effects. Thus, while the majority of Americans are willing to take a coronavirus vaccine, it appears as though to many, treatment feels rushed.

Many Americans’ cautious optimism towards the vaccine contrasts with their distrust towards federal response to the pandemic. According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in August, over half of Americans believe that poor government response, including a lack of timely testing, is majorly responsible for the continuation of the outbreak14. It is important to note, however, that views towards the coronavirus spread are widely divided across partisan lines: 62 percent of Republicans held the increase in confirmed coronavirus cases as simply a result of greater testing in previous months, while 80 percent of Democrats held that the increase was due to an increase in infections. Since the United States has the highest rate of daily new confirmed Covid-19 cases per

UK, Sweden, Spain, Italy, South Korea, Australia, and Japan), only 15 percent of adults view the U.S. response favorably [14]. In South Korea, Denmark, Germany, and Belgium, nearly nine-in-ten adults say the U.S. response to Covid-19 has been bad. The caveat here is that people’s conception of performance—and thus their conception of Covid-19 risk—does not exist independently of people’s minds and culture. A large body of research over the last decades suggests that risk perception is constructed by cognitive, emotional, social, individual, and cultural variation between people and between countries [16]. By observing trends in people’s perceptions towards their own governments and contrasting them with perceptions towards other governments, perhaps it is possible to identify potential confounding factors that might clarify overall global perceptions towards Covid-19.

Interestingly, people across the world seem to believe that their own nation’s response to the virus was inefficient. This belief is not limited to their nation’s government, but to their citizens as well. An

Perceptions of federal response to the pandemic differ across individual countries. Countries such as Italy, Canada, Sweden, Australia, Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, and South Korea in general hold that they have done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak. However, most of the public in these nations appear pessimistic towards their fellow citizens; a much lower percentage of people believe that their country is more united because of the pandemic. Overall, 48 percent of people feel that divisions have grown. Nonetheless, different groups of people indeed perceive the pandemic differently. For instance, a cross-sectional descriptive study of 500 nurses in Saudi Arabia found that more than half of the nurses had positive attitudes towards caring for Covid-19 patients, and over 90 percent had “excellent knowledge of Covid-19.”18.

Ultimately, it appears as though people’s perceptions towards Covid-19 and their willingness to take the vaccine are not merely defined by their perception of the national response. Instead, their views towards Covid-19 also appear to be motivated by their views towards their fellow citizens and uncertainty towards the promising vaccine results. Perhaps a greater degree of clarity and transparency, both at the federal and healthcare industry level, would help raise overall confidence towards a solution.

Ryan Bose-Roy is a First-Year at Trumbull, aspiring in Biomedical Engineering. Outside of the Yale Global Health Review he loves reading, learning, eating sushi, and listening to Brahms's Wiegenliend: GutenAben,guteNacht.

25

www YALE GLOBAL HEALTH REVIEW

”

“ People across the world seem to believe that their own nation’s response to the virus was inefficient. This belief is not limited to their nation’s government, but to their citizens as well.

A COVID-19 Vaccine: What’s Been Done and What’s to Come

By Maiya Hossain

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has completely taken the world aback, forcing individuals to alter their usual ways of life. From abruptly transitioning to Zoom classes in March to requiring masks in virtually all public spaces, COVID-19 has affected all facets of society, which has paved the way for what some dub the “new normal.” However, it’s clear that many people are dissatisfied with these unprecedented circumstances, as they have led to significant lifestyle restrictions, record-high unemployment levels, and negative mental health implications. With cases in the US at an all-time high nine months after the pandemic was declared a national emergency, many are left wondering: when, if ever, will life go back to normal again?

The answer greatly depends on the development and distribution of a coronavirus vaccine. This process usually takes place over the span of several years. However, the US government, in partnership with the private sector, has initiated a multibillion-dollar plan known as Operation Warp Speed (OWS), which aims to accelerate the production and delivery of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines to the general public. In June 2020, the White House named five vaccine candidates that would most likely meet the timeline of OWS. These in -

clude Moderna’s mRNA-1273, AstraZeneca and Oxford University’s AZD-1222, Johnson & Johnson’s JNJ-78436735, Merck’s multiple candidates, and Pfizer and BioNTech’s BNT-162b2.