the B&W

Print Editor-in-Chief

Lauren Heberlee

Print Managing Editor

Samie Travis

theblackandwhite.net

Online Editor-in-Chief

Ethan Schenker

Online Managing Editors

Stephanie Solomon, Sonya Rashkovan

Online Production Head

Vassili Prokopenko

Online Production Assistants

Cameron Newell, Eliza Raphael, Duy Bui, Adam Giesecke

Print Production Managing Assistants

Gaby Hodor, Elizabeth Dorokhina

Print Production Assistants

Mary Rodriguez Molina, Eva Sola-Sole, Nadeen Perera

Photo Director

Rohin Dahiya

Photo Assistants

Katherine Teitelbaum, Ava Ohana, Charlotte Horn, Heidi Thalman, Sally Esquith, Navin Davoodi Communications and Social Media Directors

Norah Rothman

Puzzles Editors

Elena Kotschoubey, Cameron Newell

Business Managers

Sari Alexander, Sean Cunniff, Alanna Singer Business Assistants

Aditte Parasher, Greta Berglund, Marissa Rancilio

Webmaster

Sari Alexander Adviser

Ryan Derenberger

Print Managing Editor

Simone Meyer

Print Production Head

Maya Wiese

The Black & White (B&W) is an open forum for student views from Walt Whitman High School, 7100 Whittier Blvd., Bethesda, MD, 20817. The Black & White’s website is www.theblackandwhite.net.

The Black & White magazine is published six times a year. Signed opinion pieces reflect the positions of individual staff members and not necessarily the opinion of Walt Whitman High School or Montgomery County Public Schools. Unsigned editorial pieces reflect the opinion of the newspaper.

All content in the paper is reviewed to ensure that it meets the highest level of legal and ethical standards with respect to the material as libelous, obscene or invasive of

Copy Editors

Sophie Hummel, Christopher Landy

Traffic Manager

Aditte Parasher

Feature Editors

Norah Rothman, Kiara Pearce

News Editors

Samantha Wang, Jamie Forman

Opinion Editors

William Hallward-Driemeier, Eliana Joftus, Zach Poe

Sports Editors

Gibson Hirt, Zach Rice, Alex Weinstein

Feature Writers

Emily Weiss, Josefina Masjuan, Caroline Reichert, Grace Roddy, Kate Rodriguez, Sydney Merlo, Dani Klein, Marissa Rancilio, Manuela Montoya, Louisa Ralston, Scarlet Mann

News Writers

Alessia Peddrazini, Jasper Lester, Greta Berglund, Ines Foscarini, Darby Infeld, Christopher Landy, Meredith Lee, Aidan Donnan, Harper Barnowski

Opinion Writers

Maddie Kaltman, Sadie Goldberg, Jacob Cowan, Ava Faghani, Natalie Easley, Ian Cooper, Macie Slater, Ben Lammers, Lucia Gutierrez, Jacob Palo, Chloe Walker

Sports Writers

Faiyaad Kamal, Ellen Ford, Grace O’Halloran, Will Gunster, Diego Elorza, Asa Ostrow, Waleed Aslam

Multimedia

Maya Kawomoto, Elena Kotschoubey

privacy. All corrections are posted on the website.

Recent awards include the 2019 CSPA Gold Crown, 2018 and 2017 CSPA Hybrid Silver Crowns, 2013 CSPA Gold Medalist and 2012 NSPA Online Pacemaker.

The Black & White encourages readers to submit opinions on relevant topics in the form of letters to the editor, which must be signed to be printed. Anonymity can be granted on request. The Black & White reserves the right to edit letters for content and space. Letters to the editor may be emailed to theblackandwhiteonline@gmail.com.

Annual mail subscriptions cost $35 ($120 for four-year subscription) and can be purchased through the online school store.

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Change is inevitable — documenting it, a choice. In this issue, a photojournalist focuses on change occurring internationally, capturing the thousands of people rallying to fight against Iran’s longstanding patriarchal system that silences women’s voices and robs them of their freedom. A writer contemplates the morality behind standing for the Pledge of Allegiance given its original intention and the changes in the years since its creation.

With positive change, controversial change may still plague in hidden ways. One writer chronicled youth as they’ve been funneled into intense wilderness rehabilitation programs, potentially leaving them with more troubles than when they arrived. Another writ-

er takes a look at what we lose when the journalism sector changes nearly completely from print to online.

And for the three of us, working as student journalists for The Black & White has exposed us to the changes within our publication, administration and student body at Whitman. Through covering incidents of antisemitism, harrowing journeys of Venezuelan immigrants, the system of student tracking and the impact of a parent’s disability on a family, we ourselves have been imperceptibly changed.

As we reflect on our time at The Black & White and pass on our roles to Volume 62, we hope they will evolve and change like we did. Through every magazine compiled, we

broadened our general knowledge and challenged our own perspective, shaping ourselves along with the stories and graphics we edited. We hope to give that same opportunity to our readers.

We’d like to thank our irreplaceable advisor Ryan Derenberger, our dedicated editors, motivated writers, talented graphics team and imaginative crossword creators for the hard work they have devoted to the publication throughout Volume 61. Thank you, Volume 61, for a bittersweet end to an era.

Best, Your editors

6 9 7 12 14 16 17

Time capsule

The impact of Title IX at Whitman

How a michelin star chef whips up success AT ‘CRANES’

Gym culture at Whitman

Exploring historical tracks at the Harriet Tubman Byway

Instrumental music strikes a chord for a writer

The fight to keep print journalism alive

rehab wilderness centers: helpful or harmful?

27 30

32

WHAT THE Pledge of Allegiance MEANT TO ITS AUTHOR 35

Exploring the depths of a treasured Maryland island

The Baltimore Orioles’ assistant general manager takes us out to the ballgame

Pro con: Should teachers use the flipped classroom model?

Documenting the D.C. protests for Iranian women’s rights 38

The impact of the Montgomery Cheetahs Special Hockey club

INTERNATIONAL CROSSWORD, THE LOGIC PUZZLE OF GRADUATION, & THE AP-TESTING TUNDRA

THE BLACK & WHITE TIME CAPSULE

Some names have been changed to protect students’ privacy.

The year was 1967. Senior Phyllis Lerner was called to the auditorium stage to receive the “Outstanding Girl Athlete” award. She had excelled in girls “Honor Teams” all throughout her high school years, but still she was shocked when her name echoed across the room.

In an eager haze, Lerner made her way up the stairs and collected her prize — a cheap plastic box, she said, that held a small pin atop a blue foam base.

Moments later, Lerner’s enthusiasm was extinguished; she watched the male recipient of the same award step onto the stage and collect a Division I college scholarship, a giant trophy and an envelope with a check from the Whitman Service Club, Whitman’s version of a booster program at the time. Only one thought was at the forefront of Lerner’s mind: this was completely unfair.

“That was a transformative moment for me,” Lerner said.

Lerner has spent her career advocating for women’s equality, specifically in regards to Title IX — a federal civil rights law prohibiting sex-based discrimination in education programs that are funded by the federal government. Passed in 1972, Title IX sought to transform school athletic programs nationally and has come with mixed results.

Gender disparities in sports predate the law and persist in spite of it, whether it be in the funding and accessibility to resources, salary, fanbase or the way people perceive players and teams in general. Even today, most sports fans say they prefer to watch a men’s match over women’s; according to the National Research Group and Ampere Analysis, while interest in women’s sports is growing, 79% of sports fans in the United States do not actively follow women’s sports.

At Whitman, the gap between boys and girls sports dates back several decades. When Lerner attended Whitman, there were no varsity-level sports available for girls. Instead, she and her female classmates were given the opportunity to participate in “Honors Teams,” which did not involve tryouts and practiced up to twice a week after school. There were no official coaches, uniforms, referees or matches. Even so, Lerner played numerous sports for Whitman in-

TITLE IX THE HISTORY OF

IN WHITMAN SPORTS

by LOUISA RALSTONcluding field hockey, volleyball, basketball and softball. She also competed for the school in county-wide events such as archery and tennis.

At the time, women’s basketball was hardly recognizable compared to today, Lerner said. There were six players on the court for each team. Each had two “rovers,” who were allowed to cross midcourt, whereas the other players were designated to one side or another. States justified this difference by claiming that women “didn’t have the stamina to go across the court all game,” according to Lerner. And while some states had permitted normal, “unlimited dribbling” by the time Lerner attended Whitman, the girls in Montgomery County Public Schools were only permitted to dribble three times before passing the ball.

“When I was supposed to be a rover, I was asked if I was on my period because if I was, then I wouldn’t have the stamina,” Lerner said.

On the flip side, Whitman highly prioritized the boys teams. They had the benefit of getting line-watchers, cheerleaders, home and away uniforms and longer practice times on the court. On top of that, they drew large crowds and gathered more support from the Whitman community.

While most of these inequities have been resolved, some still plague the school even after the passing of Title IX.

Many athletes continue to feel that they are not seen as entirely equal to their male counterparts, especially by the student body. Crowd size differences between boys and girls sports are stark, said sophomore and girls varsity soccer team player Jasmin Jabara.

“It’s within Whitman culture to have a little bit of prejudice, which doesn’t necessarily mean discrimination, but they have preconceived notions that we’re not as good as the guys,” Jabara said. “They don’t even come to our games to begin with.”

The girls basketball team, coached by Peter Kenah for the past 21 years, has had its share of successes. They have made six regional championships and two state finals, once bringing a state title home. Yet despite equality in administrative areas, they do not receive the same community support as the boys basketball team.

“When we used to have the varsity doubleheaders, and the girls

would go second, that was really hard,” Kenah said. “The boys game would end, the girls came to warm up, and you just saw the mass exodus.”

In recent years, the schedules alternate, which has helped to alleviate some of the impact on morale, Kenah said. The boys and girls teams play at the same time — home and away — so for most games, the situation is avoided. But it isn’t always the case, and the lack of support for the girls’ team is put on display.

Even in playoff runs and important games, crowds for girls are significantly less than for boys. When the boys basketball team won the state title in 2006, there were 8,000 people at the game, whereas only around 1,500 attended the girls’ championship in 2016, Kenah said.

“There is something magical when a boys team gets on a run that we haven’t quite been able to capture with the girls side,” he said.

While most issues faced by female athletes at Whitman revolve around support — or lack thereof — from the student body, there are still some noticeable differences between genders on certain teams. The softball team specifically has faced disparities in terms of equipment and field quality. “The baseball team has really nice dugouts with a roof over them, and their whole field is just really nice in general in comparison to the softball field,” said softball player Maddie Smith.

While some inequalities still linger, female teams at Whitman and the administration have made considerable steps towards reducing them. The administration plans to install dugouts at the softball field in the near future.

Whitman Athletic Director Andrew Wetzel feels that while the Whitman administration has made a conscious effort to support female athletes and level the playing field, it is up to the students to complete that final step.

“I think the leaders of the student body

need to lead the way in promoting attendance at female sporting events,” Wetzel said. “Unless it’s a state championship game, girls’ games don’t get the same attention or support by the student body.”

Jabara feels that if the Whitmaniacs or students with a lot of school spirit made more of an effort to come to girls’ games, the rest of the student body would follow, successfully reducing the support disparity between genders.

The attendance of Whitman students has a major impact on the mentality and morale of teams as a whole and players individually. Varsity girls soccer player Ella Pierce feels that the lack of student support reduces her drive and enjoyment in games.

“When we’re working so hard on the field and see that there aren’t any students at our game, it’s discouraging,” she said. “It feels like no one cares about our games.”

CULINARY

DROP-OUT TO MICHELIN STARS:

PEPE MONCAYO PLATES UP EXCELLENCE IN D.C.

by LUCIA GUTTIERREZChef Pepe Moncayo meticulously places microgreens and dried yam flakes around his newest dish: a Japanese twist on a Spanish paella. Instead of the traditional saffron rice, the dish is composed of short semolina noodles, pickled bean sprouts and cured kelp imported from Japan, all simmered in the salted kelp broth until the noodles are “halfcrunchy, half soft.” Moncayo then begins to plate his dish — he layers a bowl with Beurre Blanc sauce, fills it with the noodles and tops it with roasted brussel sprouts. The result: a complex dish with various crunchy textures, slight acidity and a salty umami flavor that can melt taste buds in a single bite.

Moncayo never pictured himself creating these critically acclaimed dishes in the comfort of his own Michelin-starred kitchen when he first dropped out of culinary school 26 years ago, he said.

Growing up in the suburbs of Barcelona, Moncayo’s love for the kitchen came unexpectedly. At thirteen years old, he was appointed “executive chef” of his household when his mom passed away, he said. With his older brother entering the military and his father busy commuting into the city for work, it was up to Moncayo to create results in the kitchen.

“I started cooking at home for survival, my dad could barely cook a fried egg,” Moncayo said. “I immediately found a passion.”

That passion he harvested for the culinary arts came from his desire to eat and try new foods. When it came time for higher education, Moncayo enrolled in culinary school in

Spain. He soon realized culinary school wasn’t what he thought he signed up for. Classes in management, marketing and finance filled his schedule. Though all necessary skills to successfully run a restaurant, Moncayo wasn’t interested. He wanted to cook.

A few months in, Moncayo decided to drop out of culinary school and started working as an apprentice at a hotel restaurant. He worked from eight or nine o’clock in the morning to midnight, six days a week. Eager to learn, Moncayo was motivated by the sense of teamwork, belonging and camaraderie in the kitchen, he said. Throughout his career, Moncayo never sent in a résumé or even applied formally for a job; rather he slowly worked his way up in the industry through hard work and recommendations until he became an executive chef at his first Michelin-starred restaurant, “Via Veneto” in Barcelona.

While an honor, he said, the achievement was just the first stop, Moncayo said. After hopping around Spain cooking for various, equally as celebrated restaurants under his mentor, renowned Chef Santi Santamaria, Moncayo received the phone call that would alter the course of his career. Chef Santamaria asked Moncayo to be second in command at his newly established restaurant “Santi” in Singapore. Without knowing his salary or even where Singapore was exactly in Asia, he said, Moncayo left the only home he had ever known to follow his ambition.

“I found a beautiful, amazing country that changed my career and my personal life forever,” Moncayo said. “The food scene in Singa-

pore was an amazing melting pot of flavors that I was so unaware of,”

While Moncayo enjoyed his life and career in Singapore, interested investors began to approach him about opening his own restaurant. Soon after, Moncayo decided to open his first solo restaurant, “BAM!” in Singapore. In creating its menu, he paid tribute to “modern shudo,” a new culinary style incorporating Japanese sake.

“I just wanted to open a fine dining restaurant, cooking with all these beautiful ingredients, and that was it.”

But after a decade in Singapore, Moncayo was eager for more.

“I cannot sit and enjoy my achievements,” Moncayo said. “I need to keep growing, I need to see what I’m capable of.”

In 2019, Moncayo packed his bags once again and headed halfway across the world to Washington, D.C. Visiting the city only four times prior to moving, Moncayo scouted D.C.’s culinary industry before deciding to open his next restaurant, “Cranes.”

Moncayo built everything for Cranes from scratch — the team, menu and even the original building, which was originally a statehouse before Moncayo tore it down to build a modern, fine dining ambiance instead.

“This design is inspired by my restaurant back in Singapore,” Moncayo said. “This one is much more beautiful… the designers took inspiration from Japan, too.”

The 12,000-square-foot restaurant features polished metal tones, sleek black-tile floors, textured tables and a gleaming bar. Cranes

presents the intersection of Spanish and Japanese cuisine through “Spanish Kaiseki.” The Spanish influence comes from Moncayo’s own culture, and Kaiseki is a style of formal, multiple-course Japanese cuisine.

However, Cranes’ is much more than a rough Japanese and Spanish fusion; it’s Moncayo’s own, cultivated by the flavor combinations he’s encountered throughout his career, techniques he’s learned from various mentors and ingredients he’s come across throughout the years. To Moncayo, his cuisine represents a Spanish guy who lived in Asia, drove a lot to Japan, became obsessed with Japanese cuisine and found a meeting point of it all, he said.

“This concept isn’t something I wanted to do out of the blue,” Moncayo said. “It’s an organic thing that’s been building in me for years.”

Cranes’ name stems from a discussion Moncayo had with his family where they told him he was like the migratory crane, traveling around the world and taking in the tastes and scents. The crane is also significant to him because it’s an important symbol in Japanese mythology — representing honor, loyalty and longevity — and the animal is native to where Moncayo’s mom lived growing up in Spain.

The star of the restaurant is the Omakase tasting menu — a ten-course menu that is constantly changing, consisting of dishes created by Moncayo using the best ingredients in season. Moncayo finds the highest-quality ingredients on the market from sellers he’s built connections with over the years. And once he finds an ingredient he wants to feature, he applies

his knowledge, technique and unconventional themes he’s observed throughout his career to create his dishes. Among some of the dishes offered recently are the duck rillette gyoza, octopus with edamame hummus, monkfish in acidulated broth and smoked eel paella.

of Moncayo’s Japanese sellers sent him a picture of a moonfish, something Moncayo had never seen before let alone tasted. The seller shipped him moonfish intestines, so Moncayo put his skills to work to create a crunchy tempura.

“It was amazing: the textures and the favors,” Moncayo said. “I keep finding ingredients that keep me excited, and that will never stop.”

At Cranes, high-quality food isn’t the only thing Moncayo strives for; the service is prioritized, too.

After only a year in operation, Cranes was awarded a Michelin star in 2021. “It was a life achievement for me,” Moncayo said. “It was a dream come true.” Moncayo makes sure to maintain his excellent quality cooking through ingredient quality control, reliable suppliers and extensive training of his team to keep the high standard in the kitchen.

One thing Moncayo respects about American cuisine in particular is the limitless array of ingredients, he said.

“The American pantry is unbelievable,” Moncayo said. “So many species of fish, seafood, even vegetables I’d never seen before.”

Moncayo has a particular passion for rare ingredients. Growing up in Catalonia, Spain he knew well certain rare ingredients such as espardenyes — sea cucumber intestines, which are a delicacy in his culture. Just recently, one

“The most important thing we can deliver in our industry is that sense of taking care of people,” Moncayo said. “Opening fancy, beautiful restaurants is money, and money isn’t important compared to humans.”

For Moncayo, the most important thing isn’t to arrive, but rather to stay, he said. He’s determined to see Cranes continue to deliver at the highest standard possible. Though Moncayo has accomplished what many chefs believe is the highest point in their career, his culinary curiosity leaves him chasing more.

This February, Moncayo opened a brand new restaurant in Tysons Galleria, “Jiwa Singapura,’’ which he describes as a love letter to his ten years in Singapore.

“I want to aspire to whatever I think is the next level,” Moncayo said. “Looking back to Barcelona, I thought I was at the highest I could achieve, but it turns out it was just the beginning.”

“I cannot sit and enjoy my achievements. I need to keep growing, I need to see what I’m capable of.From left to right: the spaces around the 12,000 square-foot restaraunt; Japanese paella; Moncayo preparing a dish in his kitchen. photos by HEIDI THALMAN

LET’S GET LIFTING: GYM CULTURE AT WHITMAN

by AVA FAGHANIThe clock hits 2:30 p.m. and a rush of students spill from the doors of Whitman.

While many of them file onto buses, start their cars or catch a ride from a friend or a family member, there are some who walk past the line of traffic entirely. Little by little, they collect at the 29 Ride-on bus stop, preparing for their daily trip to their favorite place in Bethesda: the gym.

Workout culture can be as dominating as the attitudes it seeks to create. Often, these “gym bro” students are committed to the cause, following strict schedules to maximize the benefits of working out. Many choose to go to the gym to improve their mental health, to feel and look physically stronger and to increase their energy levels.

“I often work out when I’m stressed — it helps me clear my head,” said varsity baseball player and junior Ethan Murley. “Having a gym to go to motivates me.”

Student athletes in particular find going to the gym to be the perfect way to stay in shape during off seasons. The variety of machines and resources available accommodates different types of sports training.

“When I’m not in season for a few months over the winter, I’m always going to the gym,” Muley said. “A lot of working out for baseball includes more explosive exercises, which is why the gym is very convenient for me. I am able to go to the gym and work on anything I want, when I want.”

The benefits of consistent exercise and having an outlet to go to are undeniable. In a survey done by The Black & White, 96% of Whitman students reported the gym significantly helps their mental health. Many also said they enjoyed working out to improve their physical state and appearance.

Sophomore Kristin Sartori and senior Alaia Gomez go to the Onelife gym together at least once a week. They enjoy not only the mental benefits of working out, but also looking in the mirror after extensive workouts and seeing their physical progress, they said.

“I feel that it distracts me from a lot of things I have going on or am going through,” Sartori said. “It’s also an easy way to not only ease my mind but also get my body to a point where I want it.”

At a low point in her life, Gomez was able to rejuvenate her livelihood through working out with Sartori, and now the gym is part of her daily life, she said.

“When I was going through a rough time, it gave me something to do and later feel good about,” Gomez said. “I felt healthy and strong.”

Bethesda’s Onelife Fitness, formerly known as Sport&Health, is a particularly popular gym in the Whitman community. One of Onelife’s biggest appeals, among its amenities and community, is its proximity to Whitman, sophomore Connor Ho said.

“I was introduced to Onelife by my friends,” Ho said. “I decided to get a membership there because there are a lot of Whitman kids and it’s conveniently located. I love it.”

trainer at Equinox I work with, Rudy, who has helped me to make unreal progress in strength and amazing physical results through lifting. I love every workout I do with him, and he continues to motivate me every day.”

Gyms of all tiers have seen an increase in female representation in the fitness industry in the last decade. As of 2020, More than 50% of all gym goers in the U.S. are now female, according to the International Health, Racquet & Sportsclub Association. Gomez appreciates the community overall and hopes to empower other females, she said.

“A lot of girls feel they’re gonna be judged or made fun of because it’s mostly guys, but you later realize people aren’t actually judging you,” Gomez said.

There is a notable mob of students at the gym, which changes the atmosphere at Onelife, Onelife fitness director Beau Bernado said. Although the gym appreciates the business, students have been known to crowd the gym and even may attempt to sneak in without a membership.

“We’ve definitely had an issue with kids sneaking in through the back door,” he said. “Compared to other gyms, our membership dues are fairly low. It’s not difficult to get a membership and fairly cost effective.”

A Onelife membership adds up to around $79 per month. Known to be more luxurious, Equinox in downtown Bethesda starts at about $205 per month and provides among other amenities a spa and unlimited guided classes. Senior Jake LaDuca values the deluxe quality of Equinox over other gyms, he said. After being inspired by health and physicality, LaDuca plans to go on to double major in kinesiology and finance at Tulane University. He even works with a personal trainer to optimize gym productivity.

“I go to the gym six days a week because I really just love it,” LaDuca said. “I also have a

Despite this recent wave, sexism in particular can still be found in gyms — a historically male-populated space. Part of the original bias can be attributed to the stereotypes around men, not women, being physically strong, according to Sartori. Unfortunately, females exercising in the gym will often have to maneuver inappropriate or unwelcomed remarks, said Sartori, who has experienced a wide age range of males interrupting her gym regimen.

“It’s definitely challenging to feel comfortable every time you’re at the gym because there are definitely people, whether they are teenagers or in their 30s, who don’t understand personal boundaries and will interrupt to make uncomfortable comments about you,” Sartori said.

Whitman students’ commute to the gym can be unpredictable as well. Many choose to go with friends to add extra excitement and incentive to their grind. The 29-bus ride is part of the tradition, sophomore Cade Afas said, and it can get hectic.

“The bus drivers always get mad,” he said. “The other day, a freshman trying to go to the gym ran in front of the bus and he had to stop the bus. The driver said he’s not coming back and he skipped our stop for like three days.”

Whitman students crave the exhilaration of breaking a sweat after school, they said — and they do it to be with each other.

“It’s a powerful thing,” Gomez said, “to look strong and help each other out.”

graphic by NADEEN PERERA“When I was going through a rough time, it gave me something to do and later feel good about,” Gomez said. “I felt healthy and strong.”

Road to Freedom:

The Underground Railroad and Harriet Tubman Byway

PHOTO STORY by NAVIN DAVOODI

PHOTO STORY by NAVIN DAVOODI

Hiding in plain sight on Maryland’s Eastern Shore lies a rich history detailing one of America’s most difficult times. The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway tells the story of how one of the country’s greatest patriots freed hundreds of enslaved people, leading them through treacherous land and dangerous waters in the righteous cause of liberty. Guiding visitors through various historic sights, museums and works of art, the Tubman Byway has cemented itself as one of the most important historical landmarks in the state.

graphics by NADEEN PERERA

Encompassing a 223-mile drivable route, the Byway runs through three states, starting in Maryland, moving through Delaware and ending in Philadelphia. Along the route lie 45 sites important to the workings and history of the Underground Railroad. Many are dedicated to Harriet Tubman’s remembrance. Others mark important historical sites and places that were critical to the work of Railroad conductors and the emancipation of enslaved people.

In Maryland’s Dorchester County sits the farm where a slaver enslaved Harriet Tubman and her family, starting in the early 1820s.

Along the route of the Byway lie many sites critical to the liberation of enslaved individuals. Tubman used the Bestpitch Ferry Bridge in Cambridge, MD, as a landmark to identify the way north. Places such as these were crucial in aiding Tubman and other conductors to navigate the Railroad in their effort to escape the South.

The visitor center focuses on Tubman’s bravery and perseverance in her efforts to bring others to freedom. It exhibits various sculptures of her pulling freedom seekers aboard a boat and leading others to safety, as well as multimedia exhibits and a library.

Tubman’s story began on a farm in the 1820s, where she was born under the name Araminta Ross to enslaved parents Benjamin and Harriet Greene Ross. At the age of six, Tubman was separated from the rest of her family. Though she eventually reunited with her parents and freed some of her siblings, three were forever lost to the family after being sold in the deep South. Harriet later married and took the last name of her husband, John Tubman. As she formulated plans to escape bondage, she adopted her mother’s name in an effort to conceal her identity. Following the light of the North Star, Tubman eventually made it to the safety of the North with two of her brothers. Now free, Tubman became an operator for the Underground Railroad. Over the course of her life, she would make at least thirteen journeys into Maryland to rescue family and friends.

Artist renderings on premises at the park capture Tubman’s bravery and resolve. The Tubman Byway stands as a testament to the incredible resilience, determination and courage of Tubman and many others who risked their lives to help enslaved people along the road to freedom. The Byway will continue to exemplify what it means to fight for liberty — a continuous reminder of what has forged America, and what still lies ahead in the ongoing journey towards a more perfect union.

The visitor center at Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park in Church Creek, MD, is one of the first stops along the Byway. Inside, visitors can view exhibits and collect information about the surrounding land, where Tubman lived and came to begin her track to freedom.

The visitor center at Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park in Church Creek, MD, is one of the first stops along the Byway. Inside, visitors can view exhibits and collect information about the surrounding land, where Tubman lived and came to begin her track to freedom.

notall aboutthelyrics

Every Sunday morning, no matter what, I wake up to the sound of music. Some Sundays it’s Miles Davis, others, Chick Corea. The music isn’t from an alarm or a speaker in my room; like clockwork, I expect music blaring from the living room just below me. I don’t need to hear the lyrics because there aren’t any to hear. Whether my dad fights for jazz or my mom pushes for classical, instrumental music always prevails.

While my family’s Sunday tradition dates back to some of the earliest years of my life, over time, instrumental music slowly found its way into more than just Sundays. My sister played the piano, then the cello. I played the violin, and then the saxophone. Though I no longer actively practice any instruments, I’ve entered my sixth year of ballet, where I dance to instrumental music.

We’ve all put on “lofi” beats or classical music to study, and that’s fine. But relegating the wonders of Prokofiev or the ardent beats of Daft Punk to the bottom of a playlist is like putting on “The Godfather” just to scroll through Instagram — there’s too much beauty in instrumental music to ignore. Music lovers of all genres should open their ears to instrumental music, or they risk losing its beauty altogether to the ever-changing modern music industry.

Instrumental music’s influence is undeniable; instrumental musicians provide inspiration to lyricists, they add depth to the instrumentation found in lyrical tracks and they even craft pieces of music ripe for sampling.

Instrumental music, by nature, is stripped back. With just you and the music, there’s a feeling of intimacy. There’s no voice to guide any feelings, no words to paint any pictures and no one to tell the listener how to feel. If nothing else, instrumental music leaves us to interpret the music personally.

The first genre that pops into mind when casual music fans hear the word ‘instrumental’ is classical. In classical music, the swelling crescendos and symphony of instruments take listeners on a journey. The music doesn’t always stand alone either; movie soundtracks and dance scores are incredible in part because

they pair so well with the images on screen — the Lord of the Rings soundtrack and Ludwig Minkus’ Don Quixote score are parts of collaborative works that rival the best in audio and visual arts precisely because they have such amplifying harmony within their own blend of mediums.

Although classical music is fantastic — and I’d be a pretty fraudulent ballet dancer if I disagreed — classical is just one chapter within instrumental music’s endless library. From jazz to EDM, afrobeats to bluegrass — within every genre, there are countless numbers of instru-

by JACOB COWANmental music too, like electronic music. I’ve discovered some of the most creative sounds and sonic atmospheres in electronic music. From computer-generated melodies to incredible sampling, electronic music can transport us in a way that no other form of music is capable of.

None of this is to say that lyrics are overrated. Lyrics are perfect for many songs, most songs, even. I still love lyrical works — Outkast and Adele will always have a special spot in my playlist, and neither are known for stifling their voices. But the discrepancy in popularity between lyrical music and instrumental music is far greater than it should be.

ments to assemble, each with their own unique voices. The soul of the drums in afro beats is alive. The pure power of a Dvořák brass section is just as riveting to me as any rap song I can think of.

With jazz, there are only a few instruments in the band to connect with, but a few is more than enough with the way the musicians command their craft. Those frequent, unique solos, from the saxophone to the piano, create an unrivaled level of depth and variety — something lyrical works can often exclude. Within jazz, there’s a plethora of atmospheres to explore, from intense, fast-paced improvisation to relaxing, smooth pieces. Regardless of the style, there’s an intimacy between the listeners and the musician that gives new meaning to Sunday morning Coltrane or Friday night Charlie Parker.

The futuristic synths of EDM can make you feel like you’re on another world. Even if it isn’t obvious to our modern ears, there’s limitless value to unconventional types of instru-

It’s understandable and normal to not like instrumental music at first — not everyone will be comfortable with the space it opens, nor should they have to be. I didn’t always like instrumental music. Even when I played the violin and saxophone, I never cared for classical music, and in my first few years of dancing, I couldn’t listen to classical outside of the studio. Like many, I found it boring and the culture surrounding it even pretentious at times. I felt the same way about a lot of instrumental music since I sought familiarity in the human voice — but what long-term listeners come to realize is that there is just as much value in instruments as there is in lyrics.

Selectively listening to a small subset of music and relegating the rest of the industry to the background is disappointing, especially considering that music is more accessible now than ever.

Lyrical works are just as important to the industry as instrumental work — there’s no disputing that — yet so few people listen as purposefully to instrumental music as they do lyrical music. While it’s easy to overlook the instrumental works for lyrical pieces, the raw, unbridled connection between instruments and the listener is something that we should never lose. No matter how much we love lyrics and our favorite singers’ voices, there will always be just as much beauty in the voices of the in struments.

“M usic lovers of all genres should open their ears to instru M ental M usic , lest we lose its beauty to the ever - changing M odern M usic industry .”

instrumental music provides an intimate listener experience

It’sby JOSEFINA MASJUAN

in modern journalism: Relevant or outdated?

In the modern digital age, shelves have begun to empty of print magazines. Staying informed has become yet another screenbased activity — scrolling through the same filter-bubble headlines, dodging bright advertisements and other distractions that vie for your attention.

With access to thousands of stories at our fingertips, it’s hard to imagine the world of journalism without online newspapers and digital catalogs. But print magazines, once a staple, still add elements to journalism that can’t be found on digital platforms. Now more than ever, we need this form of journalism to continue — but now more than ever, it’s at risk of ending altogether.

Print magazines date back to the 17th century, though they only became truly mass consumed in the U.S. in 1893 when several popular magazines lowered their prices. The shift made the once-expensive media form accessible to the general public. The wider audience yielded higher advertising profits, which in turn allowed magazines to sell even for less than their cost of production.

Accessibility was everywhere: Print journalism found a vast audience by offering content related to the interests and problems of the

print media has waned significantly. In 2022 alone, several popular news outlets announced they’d be cutting their print magazines, including industry giants like The Washington Post, Entertainment Weekly and Allure. The end of print journalism for several outlets has meant layoffs for print staff, most of whom had been reporting for their publication for years, becoming experts in their assigned beats.

The decision to cut print magazines and end subscriptions is partly the result of an unprecedented rise in not just casual readers, but in paid online subscribers. Digital content allows newsrooms to reach more readers faster. In sidestepping print distribution, online journalism provides flexibility when scaling to larger and larger audiences. Media are banking on new digital formats to fill the gap, and new ways to make the most of available audiences and compete for advertising.

While digital platforms do hold the advantage of efficiency, print magazines often result in more retention than screens. The simplicity of paper allows for clarity when reading, according to Scientific American, as digital devices make it more difficult to navigate longer texts and may inhibit comprehension. Lower retention translates to confused readers and a less enjoyable experience.

David Leonhardt, a senior writer for The New York Times, has experience writing for both the print and online versions of The Times after working at the organization for over 20 years. For him, the difference in the reader experience between print and online is signif

“I think one of the big dan gers of modern digital life is dis traction,” Leonhardt said. “A print newspaper never runs out of battery. It never has any notifications. You can always read it even if you’re in a tunnel or on a subway, and that’s actually something quite wonderful.”

When editing, news outlets must factor in the guarantee of digital dis tractions, including ads that pop up

throughout and in front of their stories. Editors adjust to be even more concise than they already were, involuntarily lessening the value of longer, more analytical stories. A study conducted by Slate found that only about half the readers who choose to read a given story online make it more than halfway through. That reality makes it into the pitch meetings.

According to informatics professor Dr. Gloria Mark of the University of California, Irvine, in 2004, the average attention span was two and a half minutes; in 2023, it’s about 47 seconds. Print magazines are distinct from online ones in that they allow the reader to truly pace themselves to take in what the story is conveying. For Jessica Goldstein, a contributing editor to The Washingtonian and former writer for the Washington Post Magazine, print magazines afford readers a private break from the demands of a fast-paced life.

“There’s more of a hunger for experiences that aren’t mediated by big tech, that they’re not automatically public or being tracked,” Goldstein said.

When it comes to the creative aspects of stories, print magazines also have an edge of flexibility and potential for unique artistic choices with each edition. Online user interfaces follow a consistent format by design, and copy editors publishing online must make safe and consistent choices with graphics, writing styles and conventions to ensure the reader experience is seamless with respect to other arti-

presence. In the last six years, the Post has run on an internally-built publishing suite of software called Arc XP that the publication has also annexed to sell to other media.

Courtney Rukan, the Post’s deputy multiplatform editing chief, observed this evolution firsthand. Rukan began to work for the organization in 1998 and watched it go through several publishing systems, each one integrating itself more and more into the online experience. Adapting to the digital age requires new considerations for the formatting of tangential story elements like photos and captions, he said. Editors must now consider how, where and when those elements should appear on a personal device.

When writing for print, a journalist is writing to a defined spec — the considerations are much different online, Rukan said, as captions can interrupt the flow of the story in terms of user experience. Additionally, journalists have to refine their stories to get as much hit-count traction as possible.

“We have to remember, we’re writing not only for readers, but also for the search engine algorithms,” Rukan said. “We can use those parameters to get our stories to more readers, so we really have to think about how to present the story.”

As technology advances, algorithms are becoming an increasingly important part in nearly all sectors, including journalism where they are used to aggregate user-specific content streams. Algorithms purport to expose readers to relevant articles, though for organizations to take full advantage of them, journalists must adapt their writing and be more concise, and more targeted in order to trigger recognition in the programs and continued interest among the readers.

Print publications don’t face such creative limitations. The artistic components of each mag azine add more to the experience than they do online, and the lack of constraints allows each edition to present a truly unique, but still cohe sive image.

The nightmare of disinformation and misinformation campaigns in the last decade also eases with print media — a considerably more labor-intensive medium, and one that necessarily must be more close ly managed. A series of increasingly height ened vetting awaits every story before it’s pressed into thousands of copies and shipped across the country. Editors cannot afford mis takes, and the expertise fans out, on display at every full newsstand — Runner’s World to Guitar World.

Accurate or not, online media allows the reader to easily access vast amounts of infor mation — though it can become somewhat overwhelming for the reader, Leon hardt said. For him, the word constraints of print create a unique challenge for journalists and are more substantive aims than algorithm-targeted edits.

“One of the wonderful things about print is it forces discipline in a way that online does not,” Leonhardt said. “Print forces you to say, ‘What are the 800 or 1000 words that summarize this better than anything else?’”

Users are still the ones directing the industry, according to Goldstein, and have the ability to demand the kind of positive media experiences once more common.

“I feel like people understand that there’s something really crucial about having some offline reading experience,” Goldstein said. “I think that people are seeking that.”

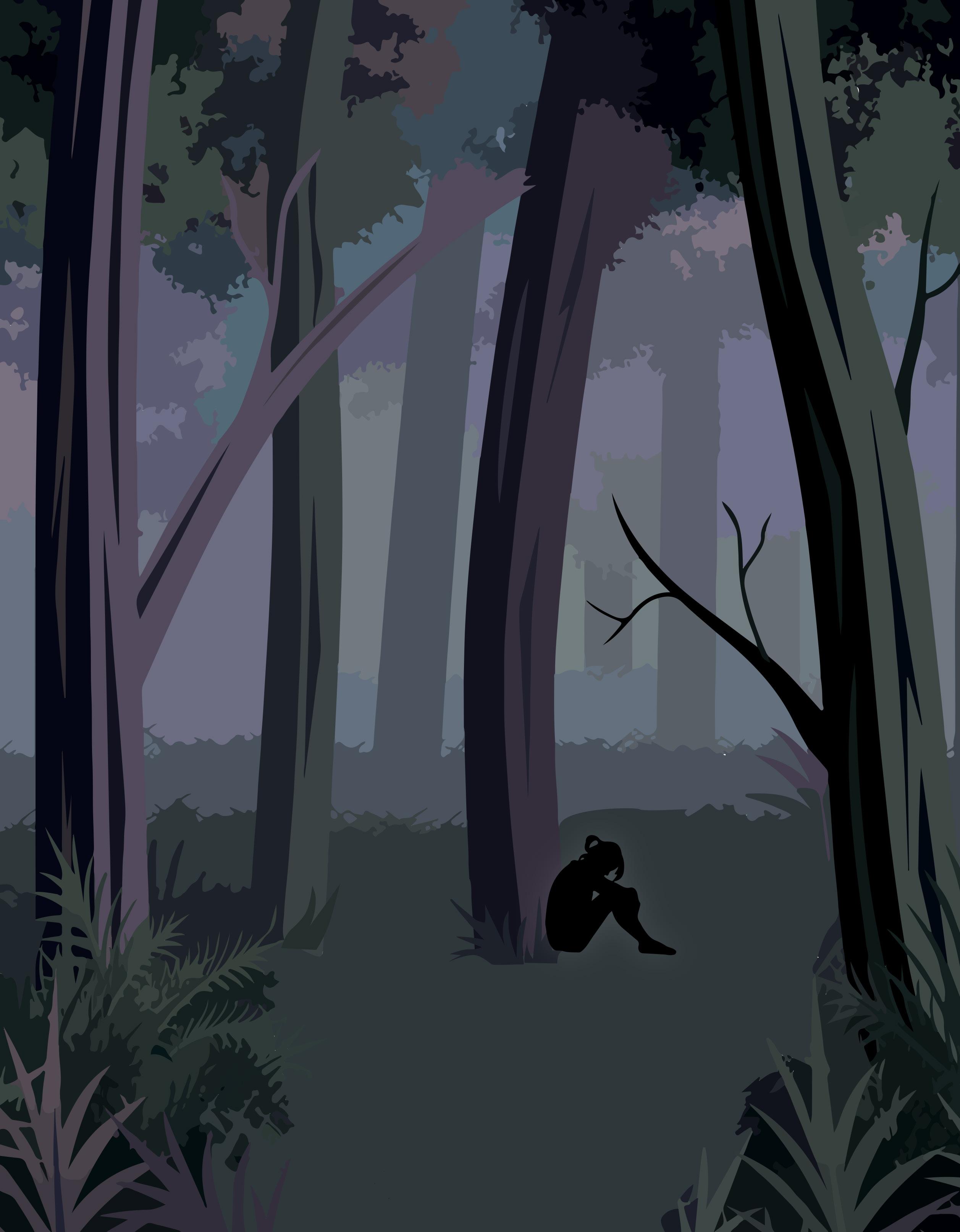

FROM TOUGH LOVE TO TORTURE

Wilderness therapy rehabilitation programs leave teenagers traumatized.

by KATE RODRIGUEZ

by KATE RODRIGUEZ

Trigger warning: discussion of suicide, drug abuse and violence.

In the scenic mountains of Utah, worlds away from anything resembling civilization, lives a group of teenage girls. Bonded together by long hikes through the forest and poetry readings around the campfire, they are participants in Open Sky Wilderness Therapy, a program that seeks to “inspire individuals to live in a way that honors, values and strengthens relationships.”

This is not, however, a normal day: Katia, a participant in the program, has just swallowed shards of glass. In the midst of the girls’ panicked calls for help, Katia is airlifted out of the woods and transferred to a higher security institution. Staff members explain that Katia will not return to Open Sky — the program does not welcome participants who continue to endanger themselves.

When senior Sarah Eisel arrived in Durango, Colorado, in Mar. 2021, she never predicted that this sort of experience would characterize the next year of her life. After struggling with drug addiction and mental health challenges, Eisel’s parents decided to enroll her in Open Sky. Based out of Colorado and with many of its programs operating in Utah, Open Sky is one of new movement of organizations that use an outdoor-based approach as behavioral intervention for adolescents and young adults.

In her first few days at Open Sky, Eisel saw newcomers experience severe substance withdrawals with little to no medical assistance. She watched Gracie, another teenage girl who would eventually become her close friend, suffer through Xanax and fentanyl withdrawals without so much as an Advil to ease her constant convulsions. The program’s unwillingness to lean on these intuitive interventions is the exact reason parents send their kids to Open Sky.

A week in, Eisel joined her “team” — a group of youth, pooled together based on similar concern and age — where she would spend the rest of her time in the program. Immediately, she felt like an outsider. Forced to intrude on a group that had been together for months and deprived of any contact with friends or family at home, an overwhelming sense of solitude defined Eisel’s first few weeks in Colorado. Exhaustion also set in quickly. Five out of seven days of the week, Eisel’s team participated in hours-long hikes, carrying heavy packs, unsure how long they’d been walking or how much further they had to go.

“My mental reaction first was just ‘how can I get myself out of here?’” Eisel said. “I was just trying to figure out every which way how I could get out, I needed to leave so bad.”

Eventually, things got easier. Eisel began to connect with other girls in the program and adjusted to the physical demands of her new daily routine. She found that Open Sky had succeeded in at least one aspect — she truly wanted to stay sober when she left.

Finally, in June, Eisel received the news she had been waiting for: in a week, she would be done with wilderness. After three months of exhausting daily hikes and nights spent on the for-

est floor, she was going to a therapeutic boarding school, Eva Carlston Academy in Salt Lake City, Utah. Eisel was elated at the prospect of having a mattress to sleep on, she said.

In the nine months she spent at Eva Carlston, Eisel felt mistreated and emotionally manipulated at the hands of staff members, she said. By the time she returned to Whitman in Mar. 2022, Eisel was sober and ready to stay that way, but she was also utterly traumatized by what it had taken to reach that point, she said.

Wilderness therapy programs and behavioral boarding schools like the ones Eisel attended are individual branches of the larger “Troubled Teen Industry.” The industry encompasses wilderness institutions, boot camps, boarding schools and behavioral ranches which look to address issues ranging from substance abuse and mental health concerns to “gaming addictions” and “social skills deficits.” The common factor that ties together these establishments is their strict approach to teenage behavior intervention — they work to fundamentally change participants’ ways of life.

While some programs implement the use of physical force, humiliation, starvation and other severe punishments to get through to participants, there are wilderness retreats that adopt a gentler approach. For Whitman youth development specialist Zakariah Anderson, experiences in wilderness programs helped him to rebuild his confidence. Following a difficult period in his high school career, Anderson spent three weeks at Outward Bound, a wilderness program located in Wales, England.

Initiated in 1962, Outward Bound held the goal of building survival skills and self-sufficiency for young boys to help them discover greater success. According to Anderson, programs like Outward Bound create a safe environment for individuals to broaden their perspective and connect to youth going through similar struggles.

“Once you sort of disconnect from not just your phone and all of these things, internet and whatever it is, and connect more with nature, you will find yourself to be a little more renewed and happier and having a greater sense of gratitude towards everything,” Anderson said.

Outward Bound’s model of cleansing through time in nature spread quickly to the United States, where copycat institutions soon populated the country. The ideology continued to gain momentum in the late 1960s, when Utah’s Brigham Young University began using rugged wilderness outings as a way to offer failing students an opportunity to salvage their academic career. From there, wilderness therapy took root in the rest of the state and spread into neighboring areas.

Utah’s status as the epicenter of the industry is also due to the specific state-level laws that dictate the way such programs can operate. In Utah, the age of medical consent is 18. Minors do not have control over what medical treatments they’re subjected to — that decision falls squarely on their parents, who maintain the right to send their child to a correctional facility if they see fit. Conversely, states like California and Washington have imposed regulations that favor individual choice; in California, minors ages 12 and older

must consent to receive outpatient mental health treatment, and in Washington, the same applies for minors 13 and older. Because of these unique laws, parents across the country who feel the need to place their child in outsourced behavior modification programs tend to seek out those

in nearly every aspect. Within the first five days of entering the program, he felt well-supported and ingrained in the program’s mission of self-improvement. Anderson spent his time canoeing, hiking and rock climbing, finding the rigorous schedule comfortable, he said.

services in Utah, or other states with lenient restrictions on medical consent and medical guardianship for minors.

Wilderness Therapy’s no-nonsense approach to self-improvement is controversial in the world of healthcare. According to the American Psychological Association, ethical issues within the movement include consent, confidentiality and the treatment methods themselves.

Many programs advise parents to have their child unknowingly and forcefully taken to the program in a simulated kidnapping situation. Renee Farnet, who attended Open Sky with Eisel, experienced this approach firsthand.

“They grabbed me by the wrists and dragged me out of my house kicking and screaming,” Farnet said. “Then they shoved me into the car while I was fighting. They locked me in, and I started having a panic attack.”

This traumatic entrance to wilderness made Farnet’s adjustment period worse than it otherwise would have been, she said. Farnet was left constantly wondering why her parents would subject her to something so absurdly terrifying.

The programs continue to foster a divide between participants and their parents for the duration of their stay. Initially, this manifests through a complete ban on outside communication. As participants advance through their time in wilderness, they are allowed limited contact with their families. Employees warn parents in advance that their child will likely resist treatment at first, and may complain or exaggerate the conditions in an attempt to escape. When a child raises concerns or asks their parents to pull them from the program, the parent is already conditioned not to believe them. Eisel said this doubt often extended to the programs’ assigned therapists and staff as well.

“They went in with this mentality that I was not to trust, or to believe, or anything,” Eisel said.

Anderson’s wilderness experience differed

“I felt as though it forced me to create these bonds and forced me to work with people, help people and work as a team and to bring that self-confidence and self-esteem back,” Anderson said.

For adolescents struggling with their gender and sexual identities, current Troubled Teen programs’ conservative rules erred on the side of harm. While at Open Sky, Farnet began to question her gender identity, and changed her pronouns to she/they. When her therapist discovered this, she accused Farnet of wasting therapy time to discuss her gender expression. For other LGBTQ+ attendees, conditions were even worse, Farnet said. Transgender participants were also forced to use pronouns they would not identify with, despite the fact that they had transitioned prior to entering the program.

“At that point, I was kind of like, ‘Huh, this is low-key conversion camp,’” Farnet said.

Although they acknowledge the ways their lives have improved since they entered wilderness therapy, Eisel and Farnet both said that programs like Open Sky are an inherently harmful way to attempt to help struggling teenagers.

“I feel like there could be ways to make it better,” Farnet said. “But you know, it’s going to be traumatizing no matter what way you do it.”

Anderson believes that the government needs to pool more money and resources into wellness programs to further education in the field and decrease the stigma around mental health. Current concerns about abuse in rehabilitation programs are often dismissed as being a “natural part of the process” — breaking an addiction isn’t easy, and is practically guaranteed to take a deep emotional toll — but not every hurdle is natural. The lack of public support leaves a void these private programs fill.

“I felt like nobody really believed me,” Eisel said. “except my friends that I made there.”

graphic by GABY HODOR“They grabbed me by the wrists and dragged me out of my house kicking and screaming. Then they shoved me into the car while I was fighting.”

The Pledge of Allegiance is a staple of public school mornings. While many students around the county and at Whitman regard the Pledge as background noise, conflicts surrounding patriotism and free speech have made the Pledge of Allegiance a controversial tradition throughout its history.

As documented by The Smithsonian, American Baptist minister Francis Bellamy originally wrote the Pledge in 1892 as part of his work for the promotions department for the American magazine Youth’s Companion. To mark national celebrations planned for 400-year anniversary of Columbus’ journey, Bellamy wrote the Pledge on behalf of the magazine and then lobbied politicians to endorse its adoption in a coordinated, national celebration. The original version had no specific reference to religion or the U.S. by name: “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

Bellamy continued to lobby, seeking to make the Pledge a daily tradition. In an editorial he published in the Illustrated American newspaper, he explained why he felt national unity was valuable for a country formed by immigrants. About Americans, Bellamy wrote “They must guard, more jealously even than their liberties, the quality of their blood”:

“There are races, more or less akin to our own, whom we may admit freely, and get nothing but advantage from the infusion of their wholesome blood. But there are other races which we cannot assimilate without a lowering of our racial standard, which should be as sacred to us as the sanctity of our homes.”

By the early 1900s, the Pledge had become a daily staple in all public, and select private schools in the U.S. In 1923, the American Legion and the Daughters of the American Revolution lobbied to add “United States” to it by name.

Then, in the 1940 case Minersville School District v. Gobitis, compulsory participation in reciting the Pledge crossed the floor of the Supreme Court. A Pennsylvania elementary school expelled two children — Jehovah’s Witnesses — for not participating. The family cited religious freedom in their complaint, but the Court ruled in favor of the school, concluding that freedom of religion and speech do not apply to the exercise of these national “political responsibilities” the justices said promoted “national cohesion” in school or otherwise.

“National unity is the basis of national security,” the Court wrote. “The mere possession of religious convictions which con-

tradict the relevant concerns of a political society does not relieve the citizen from the discharge of political responsibilities.”

In 1943, the Supreme Court reversed the decision under First Amendment free speech protections in the case West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette.

Still a tradition, many continue to feel pressure to stand for the Pledge, junior Laila Rana said.

“If everyone’s hearing their teacher say something like ‘okay, now everyone stand up for the Pledge,’ you’re going to listen,” Rana said. “It’s just what you do.”

Changes in the Pledge have also catered to smaller and smaller groups of people as its content began to reflect conservative religious values specifically. In 1954, amid anti-communist fervor, President Dwight Eisenhower and Congress altered the text to include the words “under God,” associating the Pledge with Judeo-Christian beliefs.

“I feel like the Pledge is very biased towards Christianity,” Rana said. “I’m Muslim, and I don’t feel comfortable with having to

experience here in America today.”

Seen as a natural extension of the National Anthem’s pride, the Pledge’s glorification of American patriotism marks a further point of dissent. In 2016, NFL player Colin Kaepernick began to take a knee during the National Anthem before games to protest police violence and discrimination. Students exercise the same right over the Pledge.

The country is no stranger to dissent; it was founded on it, and liberal and conservative protests alike remain part of the fabric of the country, Whitman tech ed. teacher Ted Pope said.

“I still believe in the ideals of America, but I’m also very critical of things done in the name of American patriotism,” Pope said. “I grew up in an era of protest during the Vietnam War, a time when people didn’t like what America and the American flag represented. So I completely understand people’s reluctance today to stand.”

While conversations surrounding the Pledge generally revolve around free speech, that debate often draws attention away from the Pledge’s commercial, political and nativist origins. Of the students and teachers who do stand every day, many do not know of Bellamy or the push for his Pledge to select “wholesome blood.”

pledge myself to God because I don’t know what I believe about God, and I know it’s not the same as what the writers of the Pledge believed.”

Respect for the American military became the next common point of controversy. For junior Violet Learn, who comes from a military family, her conflicts with what the Pledge compels her to say prevent her from standing up to recite it.

“When I think about the way my dad being in the Air Force has affected my family, and harmed my family, it doesn’t encourage me to pledge myself to America,” Learn said. “Because of that, I don’t feel an obligation to stand up and pledge myself to the flag.”

Whitman social studies teacher Robert Obando sees the text in a changing context. Its current version is not neutral, and is therefore not always something that Americans can support right now, he said.

“The Pledge as we know it is a relic of the Cold War — we are over 30 years past that,” Obando said. “The words of the Pledge of Allegiance do not match up with everyone’s

That disconnect is common, Obando said.

“I don’t think we realize how blurred the line becomes between patriotism and nationalism,” Obando said. “I think you can be proud or love your country in a variety of ways, and you don’t prove that by mindlessly repeating something like the Pledge, nor does patriotism have to be measured on a daily basis. I just don’t see any place for something that can be seen as forced nationalism, especially in our community as diverse as Montgomery County.”

t he words of the p ledge of a llegiance do not M atch up with everyone ’ s experience here in a M erica today .by DANI KLEIN

“Races which we cannot assimilate without a lowering of our racial standard”

the Pledge of Allegiance, according to its writerby GRACE RODDY

Plummers Island: The most-studied island in North America.

AA secluded parcel of land is surrounded by crystal clear waters, lush greenery and diverse wildlife. A small island in the Potomac River provides the perfect outdoor laboratory for conducting biological research — then, surrounding the island, miles of untouched land whose forests and dense vegetation are a petri dish for the local biota.

Plummers Island, an obscure strip of land called “the most thoroughly studied island in North America,” sits along the side of the Potomac Gorge just off the C&O Canal between Great Falls and Georgetown. The island houses hundreds of rare species, including bats, beetles, moths and invasive plants, and has been home to 120 years of research.

A nonprofit research group, The Washington Biologistʼs Field Club (WBFC) initially leased the land in 1901 and purchased the site in 1906, which included the 12-acre land and a 35-acre parcel on the adjacent Maryland mainland. The site was managed by the WBFC until 1958 when ownership was transferred to the National Park Service. The Club continues to conduct research on the island and provides grants to scientists to conduct research on the island and in the context of the Mid-Atlantic bio-region. Since 1901, hundreds of scientists have studied the islandʼs thousands of plant and wildlife spe-

cies through WBFC grants, tracking archival data augmented by their own, to inventory the island’s biota and analyze changes in the indigenous flora and fauna.

“People can go back and look at these specimens and collections and go, ‘Cool, hereʼs what was there 500 years ago,’” said John Brown, an entomologist and former researcher at the Smithsonian. “It just sets the stage and creates the foundation of knowledge that you can look at over time.”

The WBFC supplies grants of up to $5,000 to scientists for transportation to the island and equipment for when they’re there. Currently the club totals 60 members with four applications pending. First an all-male club, the WBFC became more progressive when it opened to women members in 1996. In 2005, the group welcomed Maria Alma Solis as their first female president.

As a nonprofit organization, the WBFC like others must disperse five percent of its endowment yearly towards its objective of promoting biodiversity and ecological research on the island. The club maintains its right to research the island, but has occasionally challenged the Park Service over whether they are permitted to take organisms from the island for further research.

Taking inventory of all Plummers Is-

land’s wildlife is one of the clubʼs aims, but since the proposal to expand the American Legion Bridge through the island has threatened the natural habitat, members have shifted their focus to protection. Rushed, botanists, entomologists and other scientists need to complete as much research as possible before state officials put the plan in place, they say. However, club members are hopeful that the recent change in Maryland’s leadership from Gov. Larry Hogan to Gov. Wes Moore may bring about the delay or even the elimination of the plan to expand the bridge onto the island.

“There is a chance that our efforts in promoting scientific knowledge are being understood, heard and appreciated,” said Dr. Shannon Browne, a Whitman alum and Senior Lecturer at the University of Maryland in the College of Agriculture & Natural Resources. “Weʼre very thankful that we might be saving the island after all.”

The bridge expansion was originally proposed to ease traffic, but the environmental consequences are extensive. If implemented, construction would jeopardize the biodiversity historical research and trends on the island.

Unfortunately, the club has another enemy encroaching, as well — a biological one.

INVASIVE SPECIES

On her knees, Jil Swearingen sifts through plants, searching for the invasive “grand ivy” rooted in the soil. Next, she tirelessly yanks out each stem of “garlic mustard.” Finally, she stands up: she’s finished removing all the invasive species in “plot 19,” one of roughly two dozen, 10-meter tracts scattered throughout the island cordoned to document the impact invasive species have on the native organisms.

In 2012, The WBFC formed an Invasive Biota Committee to research the destructive ramifications of invasive species on native ones. As part of the process of observing the biome, the plots go largely undisturbed land for five to ten years. Some researchers visit multiple times each month, while others only visit a few times a year to document the ongoing differences each species present.

Their findings were concerning: there were already more invasives than natives. But their data also yielded proof that the native species rebounded when invasives were removed. The committee was granted permission by the overseeing club members to start extracting invasive species with their hands and safe, targeted chemicals.

“It was clear that if we didnʼt do anything at all, there would be more and more of the invasives and less and less of the native species,” said Swearingen, biologist and Chair of the Invasive Biota Committee. “Weʼre really worried about invasive species spreading and becoming even more problematic. You canʼt just watch them, you actually have to get out and do something, and we all feel dedicated to doing something about it.”

The recent proposal to expand the Legion Bridge will worsen the problem of invasive species on the island, Swearingen said. The club is still actively lobbying for a more environmentally friendly proposal.

BATS

Diving down just below the tree tops, a bat perches itself gingerly on a branch. Hoping to find the nearest pool of water, the bat sets off and uses echolocation — a batʼs ability to locate objects through sound frequencies — to locate water close by. Beside it along the tree line are hidden microphones capturing its every sound.

Dr. Browne sifts through hours of these recordings, filtering out non-bat wave frequencies. She listens intently in order to identify each bat call in hopes of discovering a new species on Plummers Island.

Beginning her research in 2022, Browne pooled together a group of her college students to study bats. Mainly researching on the island, Browne set off on a goal: to find all ten bat species known to live in Maryland.

The American Legion Bridge looming, she decided to expand her research to not only catalog the number of bat species on the island, but prove that if Hoganʼs plan to dig up part of the island were to go through, the state would be removing an essential habitat for specifically endangered bat species. There is a sense of urgency to conduct as much research as possible to continue the 120 years of data on the island as long as possible, Browne said.

After sifting through recordings, she ultimately memorized all the calls, she said. Browne analyzed the time between each to determine what behavior the bat was engaging in and from which bat species each call originated. She primarily used their commuting calls, but other measurements help her compare statistics against one another to narrow the scope on which species are present on

Plummers Island, she said.

“Itʼs not just science, but also an art,” Browne said. “I try to think like that species: which kind of trees, water and insects do they prefer?”

Depending on the species, the locations of the recording devices must change. Bridges, cliffs, rock crevices, forests, water pools, high trees, an abandoned cabin — there’s been strategy in placing the devices to record all ten species.

Browne and her team experienced some unique challenges: bats are nocturnal, so they had to collect their data at night. Before sunset, the team would replace the SD cards and power on the devices to record all night. The organization involved in managing all of the locations came down to teamwork, she said.

On Nov. 11, her researchers ended their surveys and picked up all their equipment — but Browne herself is still working. Her results documented on the island six out of the ten bat species in Maryland. She is currently in the process of applying for another grant to purchase additional equipment and survey more frequently in new locations.

Once Browne discovers which species are present on the island, she makes recommendations to help those threatened and endangered species. Saving these species is not just important for their survival, but for human survival as well.

“I want to inspire and educate future generations, influence policymakers in their decisions so that they prioritize environmental health and wildlife health, Browne said, “because itʼs all tied to human health and because itʼs the right thing to do.”

MOTHS

At dusk, John Brown hops out of his truck, lugging moth traps made from buckets, lights and ammonia along with him in hopes of catching as many moths as possible throughout the night. Thirty minutes later, he climbs back into his car and heads back home, excited to go out collecting again in the morning.

Brown, an entomologist specializing in Lepidoptera at the Smithsonian, worked to inventory of the kinds of “Tortricidae” moths

present on the island from 1990-1999. He compared data from 1901-1910 to see how the species varied over time.

To collect his data, Brown set up traps all across the island hoping to capture the moths. Blacklight traps, Brownʼs preferred collection method, proved to be the most successful method of catching them in bulk. He stuck buckets on the ground with a light just above, attracting the moths. As the moths fly around the blacklight, they fall into the funnel below the light, and are trapped in the bucket, where they are killed by ammonia fumes.

With grants from the WBFC, Brown hired students to help him set up traps and collect specimens. Every Saturday morning, Brown then collected his buckets of dead moths, beetles and other insects, laid them out on his kitchen table and started to sort — a process that lasted four to six hours. With insects, scientists must pin them on a board and label the species so other scientists in the future can look at the mothsʼ dimensions and species.

“It is just a really enjoyable time chatting about entomology, pinning and labeling insects every week for ten years,” Brown said. “Iʼve always loved research, and I would publish six or seven or eight papers a year.”

It was when Brown realized the tortricid was declining that he decided to focus more on the how and why uncovering how the species and numbers have changed over time. The most baffling part of his entire experiment was realizing that scientists in the early 1900s collected more moth species than he did by just using a lantern and bedsheets, Brown said.

Brown decided after ten years that he would publish his findings and end his research to eliminate bias because previous studies were also conducted over a ten-year period.

“Whenever you finish a research project, you realize that you have raised more questions than you have answered, and thatʼs whatʼs cool,” Brown said. “Thatʼs what leads to more research.”

Though Brown retired in 2014, at age 71 today, he continues to commute to the Smithsonian daily, paying for public transportation to identify insects, he said.

“This is really typical of older scientists at the Smithsonian and I think elsewhere across the globe,” Brown said. “You just develop this passion for something, and just because youʼre done or youʼre tired, you still have it.”

BEETLES

While hiking across a back trial, Warren SteiWhile hiking across a back trial, Warren Steiner spots dying ash trees and rummages around trying to find the cause of death. He comes across a few small green beetles, each the size of a grain of rice, hovering around the trunk. Steiner picks one up and later finds it to be an emerald ash borer, a rare pest origi-

nating in Asia — previously undiscovered on Plummers Island.

Part of a lineage of research that began in 1900 and ended in 2000, Warren Steiner, an entomologist specializing in Coleoptera at the Smithsonian, studied the beetle population changes on Plummers Island. He and other entomologists found that some species disappeared as the years went on, but a few new species were also discovered.

In the 80s and 90s, Steiner and his colleagues made several trips to the island, including many nighttime vigils. Their UV light attracted a multitude of beetles, but Steinerʼs favorite capturing method is a fluorescent tube that projects onto a white screen, he said.

Steiner used Malaise traps — tent-like structures that lure the insects to the highest point of the tent, where they fall into a container below — primarily used to catch flying beetles. He also knew how to get down in the dirt, sifting through the grass and turning over logs, hoping to scoop up with his hands and then document as many species as possible.

In the early years of the WBFC, researchers discovered 53 new beetle species active on the island. Steinerʼs study from 1976-2006 showed that 29 out of the 53 species were still present alongside a new eight.

“Iʼve had fun naming them, describing what they do and documenting the other critters that share the planet with us,” Steiner said, “hopefully — can do something about their decline.”

Invasive populations threaten insects’ survival significantly. The shift in food type and availability, researchers say, will likely cause the beetle populations to diminish over time or even disappear.

There are few places on the earth as heavily studied as Plummers Island. The area is uniquely diverse as a biodome because humans in modern times have never tried to occupy it or build through it. It’s had millennia to just be.

After purchasing it, the Park Service made it outright illegal to disturb the area. The plans to construct a bridge seek to end that protection.

The island’s value to the scientific community nationally and nearby is irreplaceable, Steiner said.

“Plummers Island is just as interesting on a local scale because of its history,” Steiner said. “The islandʼs diversity and its being near scientists makes it that much more special.”

A & Q with Eve Rosenbaum Orioles’ Assistant General Manager

by MARISSA RANCILIO

by MARISSA RANCILIO

Eve Rosenbaum is the Assistant General Manager for the Baltimore Orioles. Rosenbaum grew up playing baseball and later moved to softball during both high school and college. She graduated from Whitman in 2008 and then went on to attend Harvard University. While in college, Rosenbaum earned an internship with the NFLʼs commission office and then later worked in international scouting for the Houston Astros. She transferred to the Orioles in 2019 as the director of baseball development and was recently promoted to Assistant General Manager.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.