NEW TERRAIN

21st-Century Landscape Photography

1

April 6 – July 7, 2024

Nancy Kathryn Burns

Olivia J. Stone

3

© 2024 Worcester Art Museum

worcesterart.org

NEW TERRAIN 21st-Century Landscape Photography

4

Hahnemuhle bamboo paper on white board, image (irregular): 59.2 × 59.4 cm (23 5/16 × 23 3/8 in.) framed: 71.8 × 71.4 cm (28 1/4 × 28 1/8 in.), Chapin Riley Fund at the Greater Worcester Community Foundation, 2023.35

That-Which-Has-Been-Reclaimed: Dawoud Bey, Stan Douglas, and Places in Memory

Nancy Kathryn Burns

New Terrain: 21st-Century Landscape Photography began as a project on the broader notion of place, not landscape specifically. There’s an important conceptual shift when speaking of a space versus a location. The former is seemingly limitless and can exist anywhere, while the latter entails boundaries and direction. Reflecting on both, I wondered whether a memory is a space, a place, or something else entirely.

When speaking of memories, people use orienting verbs like “located in,” “return to,” and “revisit.” One can even “get lost” in memory. The most notable difference between one’s current location and the one in memory is the relationship to time. In recollection, summoned details of varying reliability define how far the mind journeys.

People who share the same experience often recall or emphasize different aspects of an event, a form of selective memory. Weeding through first-hand accounts of collective memories to sort fact from fiction is among a historian's primary tasks since our shared memories anchor history. Though New Terrain foregrounds the relationship between photographic processes and the landscape genre, several objects, particularly those in the exhibition's second half, also examine the relationship between landscape, memory, and history.

Among artistic media, photography arguably has the most immediate relationship to history. In his 1980 treatise on the medium, French philosopher Roland Barthes (1915-80) asserted that the photograph's distinctive expression, or noeme, is a “that-has-been.”1 In other words, the essential feature of a photograph is its relationship to time, not its reliance on light, as many (including myself) argue. Photographs simultaneously co-exist in the past and present. The exposure “has been,” and the resulting image is experienced now and into the future. The photograph manifests time by fixing history to paper.

Barthes's definition hinges on the use of a camera and a reliable author, namely a photographer who prints their exposures as seen.2 He insists on photography being a truthful document of the past, “[It is] the necessarily real thing which has been placed before the lens, without which there would be no photograph.”3 In his mind, a photograph is like a ghost that lingers between life and death, neither here nor there, always both. But what would Barthes make of photographs that operate as a metaphoric “that-has-been”?

1 Barthes, Roland. 1993. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard (London, England: Vintage Classics, 1993), 77.

2 Considering this, I think Barthes would appreciate the works in New Terrain, though he may contest designating cameraless works like Alison Rossiter’s latent images from expired paper and Meghann Riepenhoff’s oceandipped cyanotypes photographs.

3 Barthes, 76 (italics Barthes).

5

Curator Mekeda Best began this line of inquiry in her 2021 exhibition, Devour the Land: War and American Landscape Photography since 1970, which examined the impact of the American military complex and environmental injustice through contemporary depictions of the landscape. In the accompanying catalogue, she elaborates on the broader role of the landscape genre as a form of ecocriticism: “Photography uniquely contends with complex historical phenomena that span time and geography…If landscape emerged as a way to see, frame, and organize space, then these images insist on connecting us to the natural world by forcing us to recognize and recover what is invisible and diffuse in the present and what is lost to memory.”

Most of the photographs in Devour the Land document war-torn, wounded terrains. Tragic histories permeate images of bleak, Cold War-era airfields and toxic craters. These photographs are truth-tellers in the Barthesian sense. By contrast, the large-format obsidian landscapes by Dawoud Bey and Stan Douglas in New Terrain use the camera in the service of remembrance instead of recounting what “has-been.”

Bey’s 2017 Night Coming Tenderly, Black is a moving series of 25 photographs memorializing Ohio homes and patches of land along the presumed path of the Underground Railroad, a network of largely undocumented “stations” that aided enslaved African Americans on their perilous route to emancipation. Historians date these clandestine paths to the early 19th century through the Civil War (1861-65). The title of the series comes from the 1926 poem Dream Variations by Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes (1901-1967):

Rest at pale evening . . .

A tall, slim tree . . .

Night coming tenderly

Black like me.4

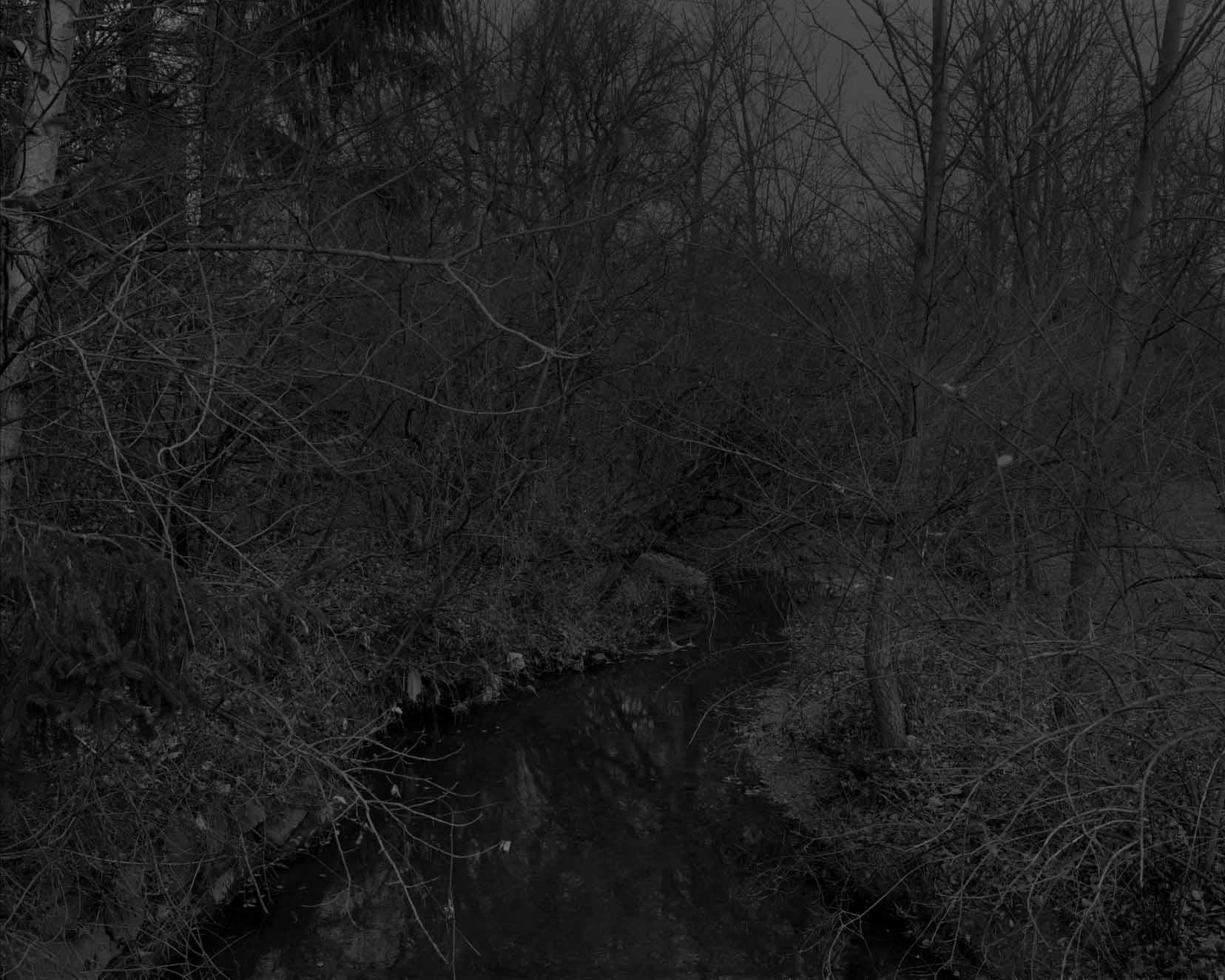

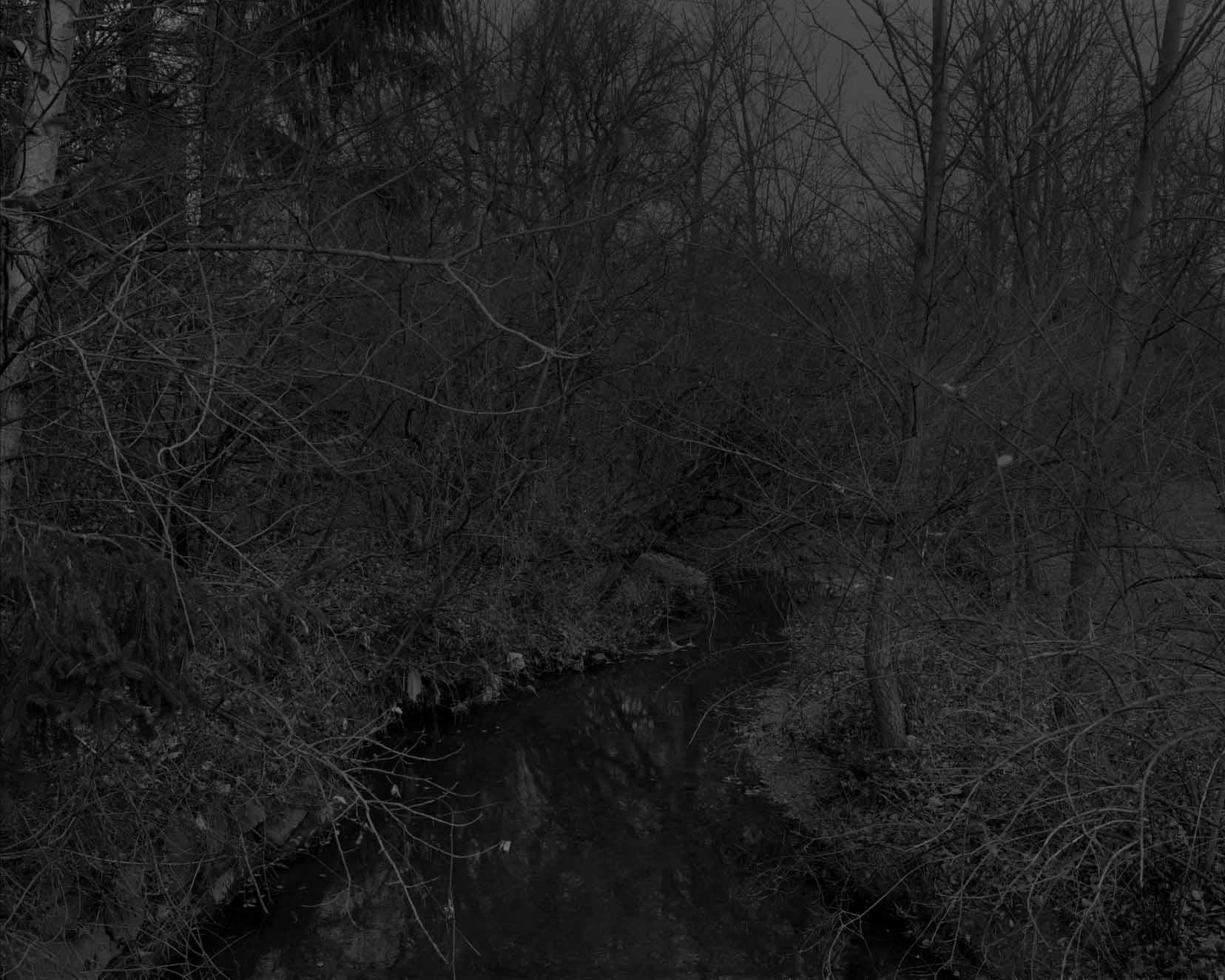

Untitled #19 (Creek and Trees) (Fig. 1), like all the works in Night Coming Tenderly, Black is the product of historical research that led Bey to Hudson, Ohio, a rural town largely unchanged since the 19th century. The region’s static landscape helped Bey conjure the emotional intensity of escape. Although none of the photographs include a figure, they are shot from the vantage point of a fugitive navigating what Bey and Hughes call the tender embrace of nocturnal darkness. While night can heighten fears of the unknown, it can also conceal, offering reassurance to those trekking toward freedom. “It was important to me that the fugitive slaves moving through this terrain possess a sense of presence, even though their actual bodies aren’t depicted,” the artist said in a 2019 interview. “The experience is visualized and imagined through their eyes; so, while their black bodies may be literally absent from the images, their presence still informs the work in a visceral way.”5

The scale, tonality, and slightly off-kilter perspective of Bey’s prints approximate the spatial and sensory experience of those cautiously traversing unfamiliar and dangerous terrain at night. Like entering a dimly lit space, the viewer’s eyes slowly adjust to the dark tonal range and reflective gelatin silver paper before becoming fully immersed in Bey’s black and steely landscape. To achieve this inky effect, he photographed the landscapes during the day and then overexposed the negatives, creating the impression they were captured at night.

4 Langston Hughes with contributions from Arnold Rampersad, and David E Roessel. “Dream Variations” in The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, 1995 (New York: Vintage Books) 40.

5 Louis Bury and Dawoud Bey. “Making Interiority Visible: Dawoud Bey Interviewed.” BOMB, April 5, 2019.

6

7

Fig. 1: Dawoud Bey (American, born 1953), Untitled #19 (Creek and Trees), 2017, gelatin silver print, image: 111.8 × 139.7 cm (44 × 55 in.), sheet: 121.9 × 149.9 cm (48 × 59 in.). Museum purchase through the Gift of Jean McDonough, 2024.2. Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles

Bey uses a 21st-century camera to recreate a 19th-century image of “that-as-it-might-havebeen” based on inherited oral histories that were too dangerous to record on paper. While Bey objectively captures a photograph of a scrubby rivulet in the Ohio woods, it may be better understood as a “rememory,” a central theme in Toni Morrison’s (1931-2019) novel Beloved. The term appears early in the book when the protagonist Sethe, once enslaved, is compelled to recount her daughter’s birth:

I was talking about time. It’s so hard for me to believe in it. Some things go. Pass on. Some things just stay. I used to think it was my rememory. You know. Some things you forget. Other things you never do. But it’s not. Places, places are still there. If a house burns down, it’s gone, but the place—the picture of it—stays, and not just in my rememory, but out there, in the world. What I remember is a picture floating around out there outside my head…Someday you be walking down the road, and you hear something or see something going on. So clear. And you think it’s you thinking it up. A thought picture. But no. It’s when you bump into a rememory that belongs to somebody else.

Night Coming Tenderly, Black uses photography to resurrect Civil War-era landscapes haunted by the trepidation that those fleeing enslavement and persecution endured. As such, Bey’s Creek and Trees is a borrowed thought picture of another’s taxing journey.

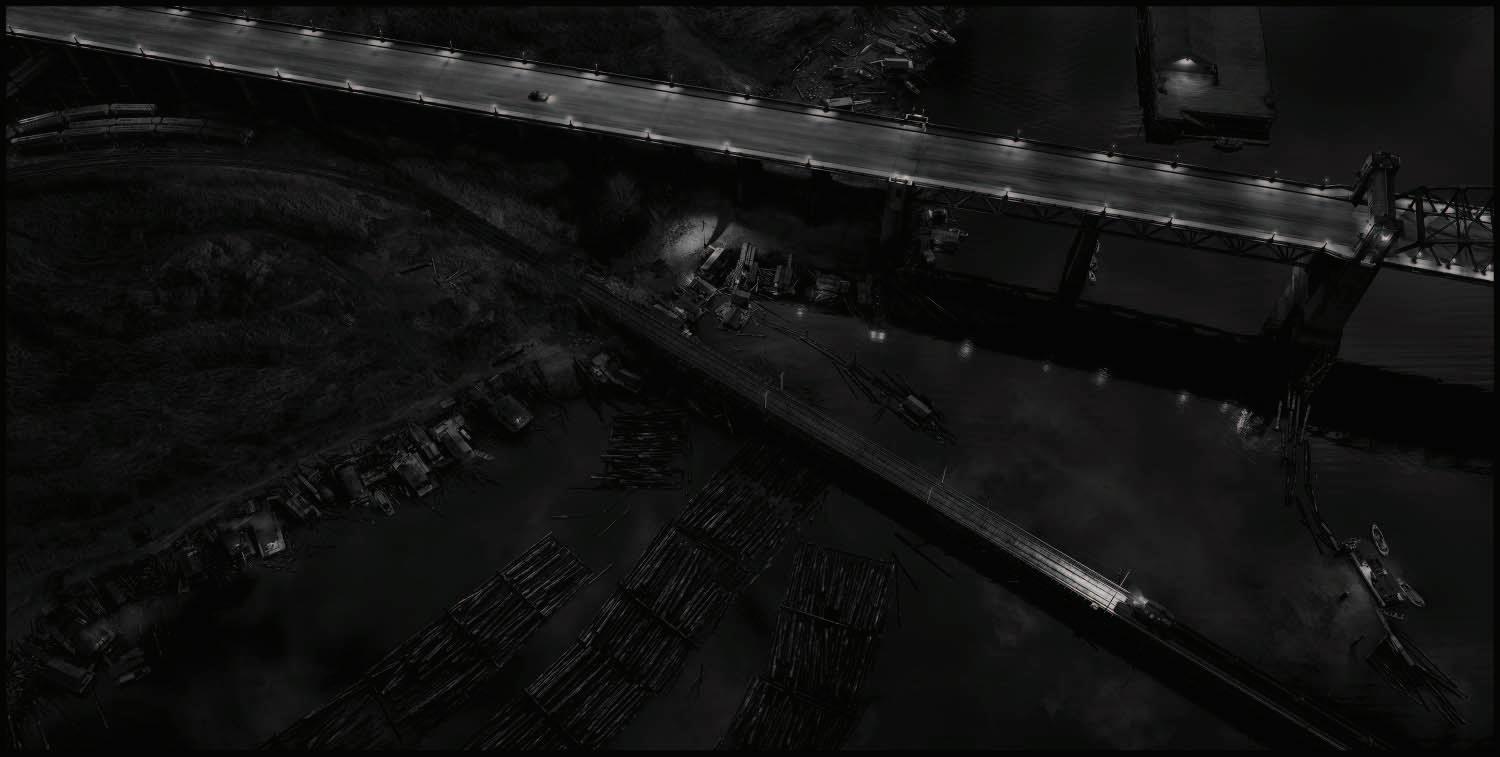

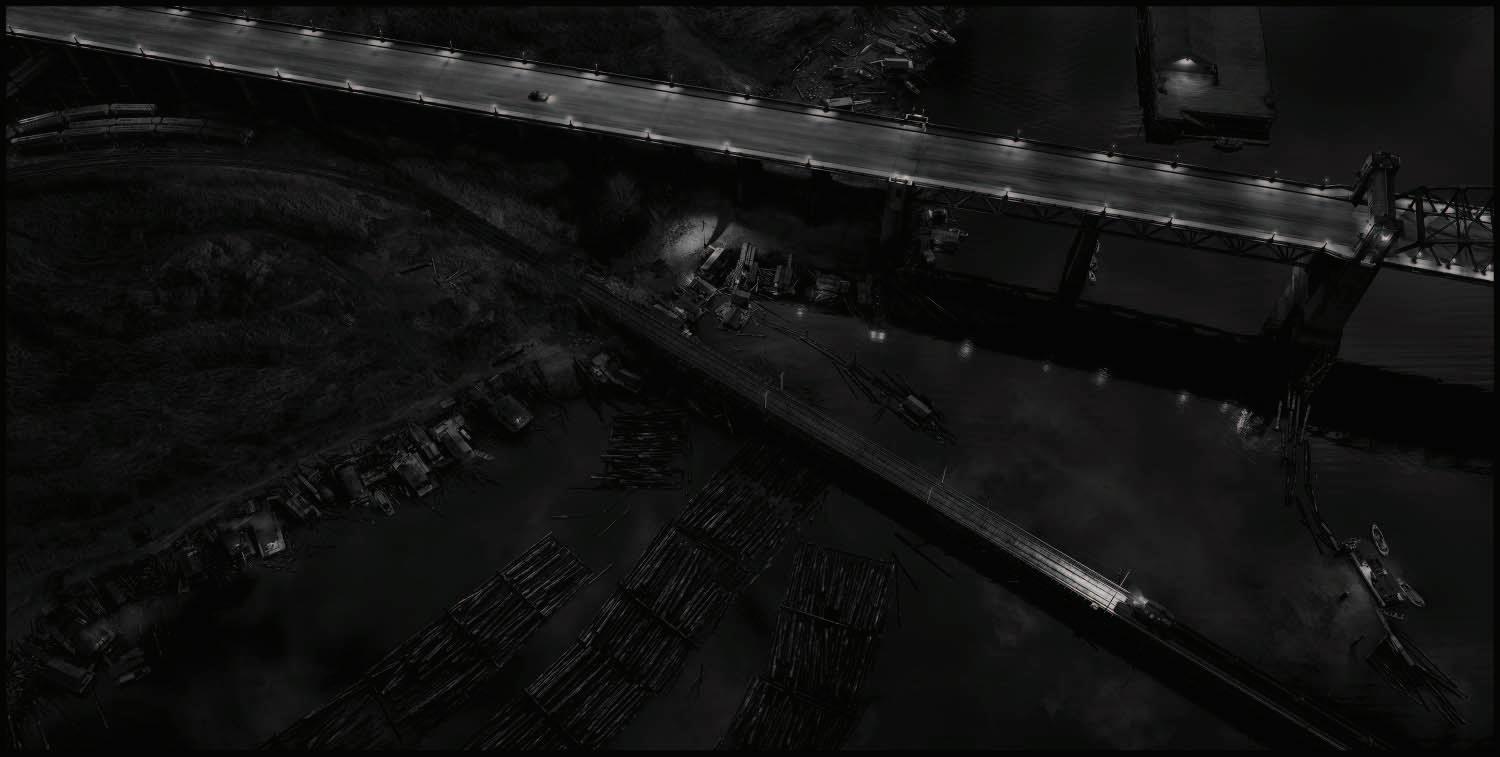

Like Bey, Canadian multi-media artist Stan Douglas concentrates on land as a site of rememory. In Douglas’s case, reconstructions of demolished urban terrain illustrate the repercussions of systemic economic and racial inequity on the landscape. Bumtown (Fig. 2), an eerie nighttime aerial view of bridges over the Vancouver shoreline, is a digitally rendered photograph that looks more like the staging for a 1940s film noir than a place once inhabited. Uncanny in its precision, it is removed several times from the original photographs that informed it.

8

Fig. 2: Stan Douglas (Canadian, born 1960), Bumtown, 2015, printed 2016, digital chromogenic print mounted on Dibond aluminum, image: 151.3 × 302.3 cm (59 9/16 × 119 in.). Museum purchase through the Loring Holmes Dodd Fund, Theodore T. & Mary G. Ellis Fund, and funds by deaccession from the Gift of Miss Annie Sprague Weston.

The image first appeared in 2014 as part of an immersive iPhone and iPad app called Circa 1948, created by Douglas and the National Film Board of Canada. The app enables users to move through a hyperrealistic digital storyscape of two neighborhoods in post-World War II Vancouver. Predominantly populated by immigrants and people of color, both locations were subsequently leveled beginning in the late-1940s. After completing Circa 1948, Douglas scaled up the 1,000-pixel files for projection onto scrims for a theater production he directed called Helen Lawrence. Finally, he produced a series of massive, black-and-white chromogenic prints using the same ultra-high-definition files, including Bumtown.

Photo historian Noam Elcott describes Bumtown’s sketchy waterway as “the intertidal zone, a no man’s land”6 that connects the gamblers and prostitutes on Vancouver’s Hogan’s Alley with the squatters living on the North Shore. Douglas resurrected these razed sites by painstakingly crafting historically accurate 3-D models from vintage photographs and film clips using the computer animation program Maya. The entire project took Douglas and a team of Maya artists over two years to complete.

Bumtown presents the viewer with an augmented reality equally hyperreal and hyperunreal. Although the image is sourced from archival material, the meticulous details, like the wisps of fog drifting across the glassy water and the bridge's rippling reflection, are too true, too exact. Likewise, the dark-as-pitch sky would be impossible to capture with a camera. Douglas reflected on his unattainable night photographs and said, "It's taking a photograph you can't really take. The places aren't there anymore, and there's no light.”7

As with all his nighttime photographs, Bumtown is a “that-has-and-has-not-been.” A nearly indecipherable déjà vu, this shoreline was once seen and photographed but is now a refashioned memory. Its nearly-real quality causes the eye to stumble. Like much of Douglas’s interdisciplinary work, Bumtown contends with the in-betweenness of photo, animation, performance, and film while visualizing the displacement of Black and Brown people through landscape. Comparable to Bey’s land memorials, Douglas’s photographs commemorate marginalized communities sacrificed in the name of urban renewal. Bey’s and Douglas’s landscapes are best understood as examples of Morrison’s thought pictures honoring victims of racial subjugation across three centuries. By representing “thatwhich-has-been-reclaimed,” both artists use photography to recenter forgotten people and places. Like several other photographs in New Terrain, these two works use landscape to uncover and restore painful but indispensable rememories. In so doing, these remembrances are made manifest and defined, indicative of memory’s capacity to inhabit a place, not merely a space.

6 Noam Elcott. “Counter History Paintings: Stan Douglas’s Photo-Panorama’s.” in Stan Douglas (Hasselback/ MACK: Göteborg: Sweden), 2016, 13.

7 Stan Douglas, quoted in Nick Compton, “Eye Spy: Stan Douglas goes undercover at London’s Victoria Miro,” wallpaper.com (February 5, 2016).

9

12

Fig. 1: Tabitha Soren (American, born 1967), Katie’s Vacation Photo from Surface Tension, 2018, archival inkjet print, ed. 2/5, image: 76.2 × 101.6 cm (30 × 40 in.), sheet: 81.5 cm x 106.5 cm (32 × 41.9 in.). Chapin Riley Fund at the Greater Worcester Community Foundation, 2021.94 © Tabitha Soren 2024

The Land-Index: Photography Contends with the Anthropocene

By Olivia J. Stone

Anthropocene noun An·thro·po·cene |‘an-‘thrä-pə-sēn| : the period of time during which human activities have had an environmental impact on the Earth regarded as constituting a distinct geological age. –Merriam-Webster Dictionary 1

Proposed in 20002 as a potential new geological age to describe our current era (instead of the Holocene), the Anthropocene is a helpful framework within which the impulses behind 21st-century landscape photography can be contextualized. In the preceding century, figureheads of photography advocated for land conservation with images of Nature seemingly documented in a pristine state. Today, however, the claim that any point on earth has not already experienced the impact of human activity seems naïve, at best.

The planet is changing rapidly, from a spike in microplastics found in our water, soil and bodies, to an unstable climate melting remote glaciers. The following photographers pursue the landscape in one of two ways: a nuanced look at land through the lens of human impact, or an alternative photographic process that incorporates a part of the land itself.

Foregrounding touch while also sounding the alarm about society’s distance from nature, Tabitha Soren’s (American, born 1967) work Katie’s Vacation Photo (2018) obscures a Chilean glacier behind multiple layers of removal. (Fig. 1) The titular vacation photo is being shared—as most photos are nowadays—on a touchpad screen whose surface is marred by fingerprints. Soren then used a view camera—19th century, analog technology—to take her own photograph of the screen as it displayed the glacier image. Raking light amplifies the tablet’s dirty surface, generating greasy rainbows. Soren’s photograph thus encapsulates both the viewer’s physical and mental distance from the subject, a reversal of conventional wisdom about photographic immediacy.

1 “Anthropocene.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Anthropocene. Accessed 6 Feb. 2024.

2 Paul J. Crutzen and Eugene F. Stoermer, ‘The “Anthropocene,”’ Global Change Newsletter 41, (May 2000):17-18.

13

Surface Tension, the series from which Katie’s Vacation Photo comes, investigates the space between “two systems, animal and machine,”3 so it is not surprising that Katie’s Vacation Photo does not operate as a typical landscape. The visual interventions covering the glacier suggest much more than is visible: for example, the ecological pitfalls of the tourism industry, or the extraction of rare earth elements needed for our tech. In this mode, the fingerprints take on a dark significance, melting away the glacier in a manner that goes on to suggest humanity’s compounding effect on climate change. As Soren further notes, another unseen impact is social.

“For me, the rainbow glitches from the sweat and hard side light really interrupt the beauty of the glacier and water background picture. This parallels the way technology interrupts the quiet beauty of our daily life. Posting on Facebook or Twitter [today, X] makes communication about morality and environmentalism very easy but makes actual moral living very hard.”4

Similar to Soren’s use of a view camera, David Emitt Adams (American, born 1980) also employs a photographic process more common in the 19th century in his commentary on modern landscape degradation. 111 Degrees, Facing West (2014) is a wet plate collodion tintype that Adams developed on the surface of a metal can that he found discarded in the Sonoran Desert in the Southwest. (Fig. 2) The tintype captures the view Adams saw from the position where the can lay. Like Katie’s Vacation Photo, this landscape offers a haunting quality as it recedes behind a narrative of human impact. In his artist’s statement, Adams explains, “As long as people have been in the American West, they have found its barren desert landscapes to be ideal for dumping garbage and forgetting. [… T]he notion of land untouched by the hand of man is so foreign it might as well be make-believe.”5 Both Adams and Soren tacitly acknowledge a landscape charged with the Anthropocene.

Yet, Adams’ work also departs from Soren’s significantly. In a reversal of the tablet screen’s human fingerprints, the rusted surface of 111 Degrees, Facing West has been corroded by the desert’s sun, wind and daily temperature swings. This leads to an intriguing suite of questions. Aside from the medium’s defining touch of light, what other marks can an environment leave on the photographic surface? Art theorists use the term “index” to describe traces and other visual indicators that offer evidence of a presence— a common example is a set of footprints indicating that someone has walked by. What would a “land-index” look like? Can photographers effectively co-author a photograph with the subject, and if so, what new perspective on landscape can this offer the viewer?

The following two photographers, Matthew Brandt (American, born 1982) and Meghann Riepenhoff (American, born 1979), both push the landscape into an active role within their practice by using the kinetic and chemical properties of water.

In 2008, Brandt began his series Lakes and Reservoirs. (Fig. 3) At first, the process behind these images seems straightforward: using a digital camera, Brandt photographs bodies of water in the American West. While there, Brandt also collects water from the site, and later uses this unfiltered liquid—murk and all—in the darkroom to bathe the image after it is exposed onto Kodak Endura chromogenic paper. The lake water makes its mark. Resulting striations of red, yellow, black, and white are the chromogenic paper’s thin emulsion layers as they peel away, their appearance a function of how long the paper was left in the bath and whatever organic material may have been swimming in

3 Jia Tolentino, Introduction to Surface Tension, by Tabith Soren, unpaginated. Paris: RVB Books, 2021.

4 Tabitha Soren, emailed correspondence with the author, January 29, 2023.

5 David Emitt Adams, “Conversations with History,” accessed November 3, 2023, http://www.davidemittadams.com/portfolio/traces.

14

15

Fig. 2: David Emitt Adams (American, born 1980), 111 Degrees, Facing West, 2014, wet plate collodion tintype made on metal can found in the Sonoran Desert, 10.2 × 16.5 × 22.9 cm (4 × 6 1/2 × 9 in.). Funded by the Douglas Cox and Edward Osowski Fund for Photography, 2018.49 © David Emitt Adams

Fig. 3: Matthew Brandt (American, 1982), Lake Dillon, CO1, 2011, chromogenic print soaked in Lake Dillon water, framed: 82.6 × 108 × 3.8 cm (32 1/2 × 42 1/2 × 1 1/2 in.). Collection of Ndingara and Mark Nevins. © Matthew Brandt, Courtesy of Yossi Milo, New York

16

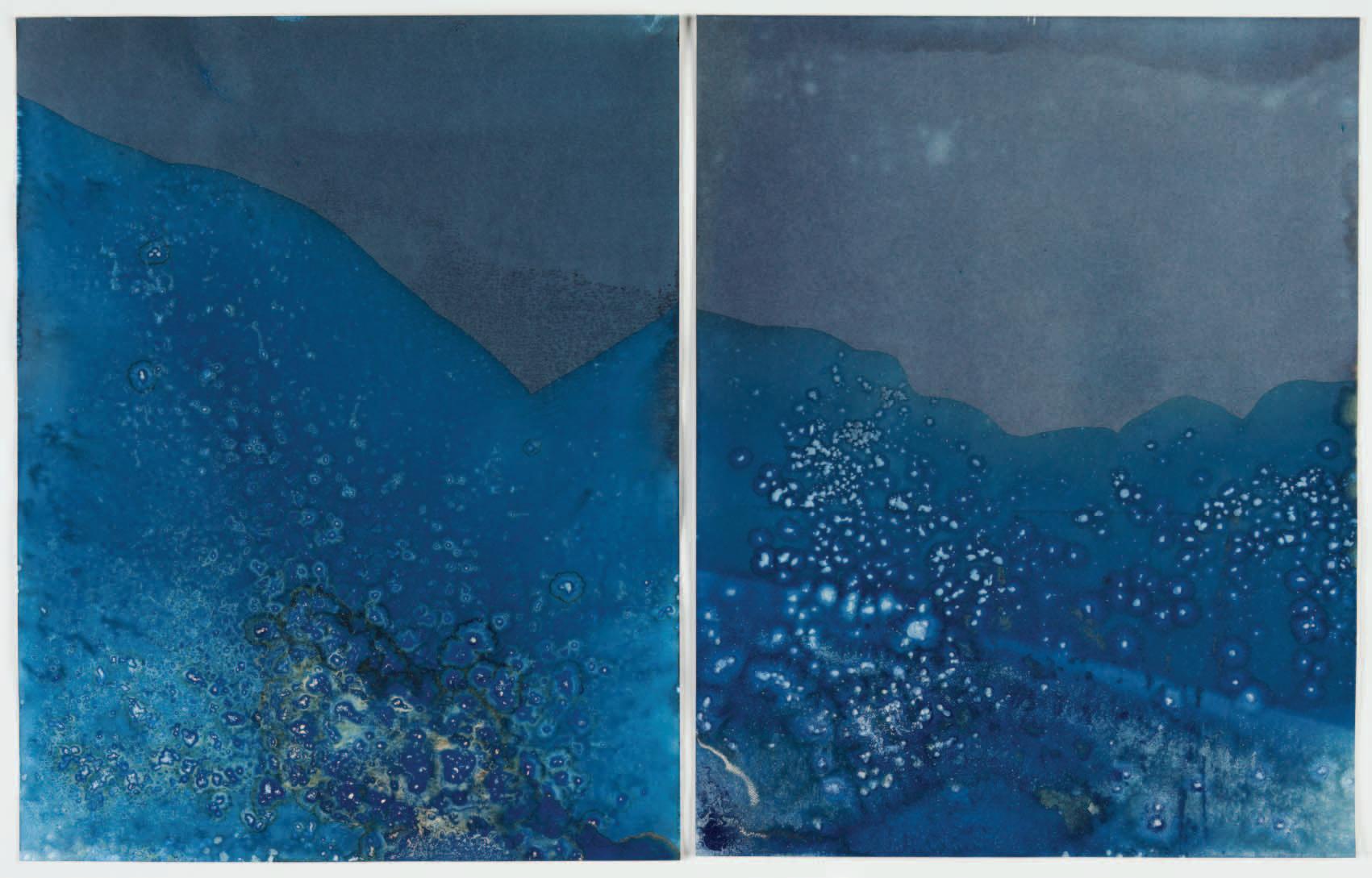

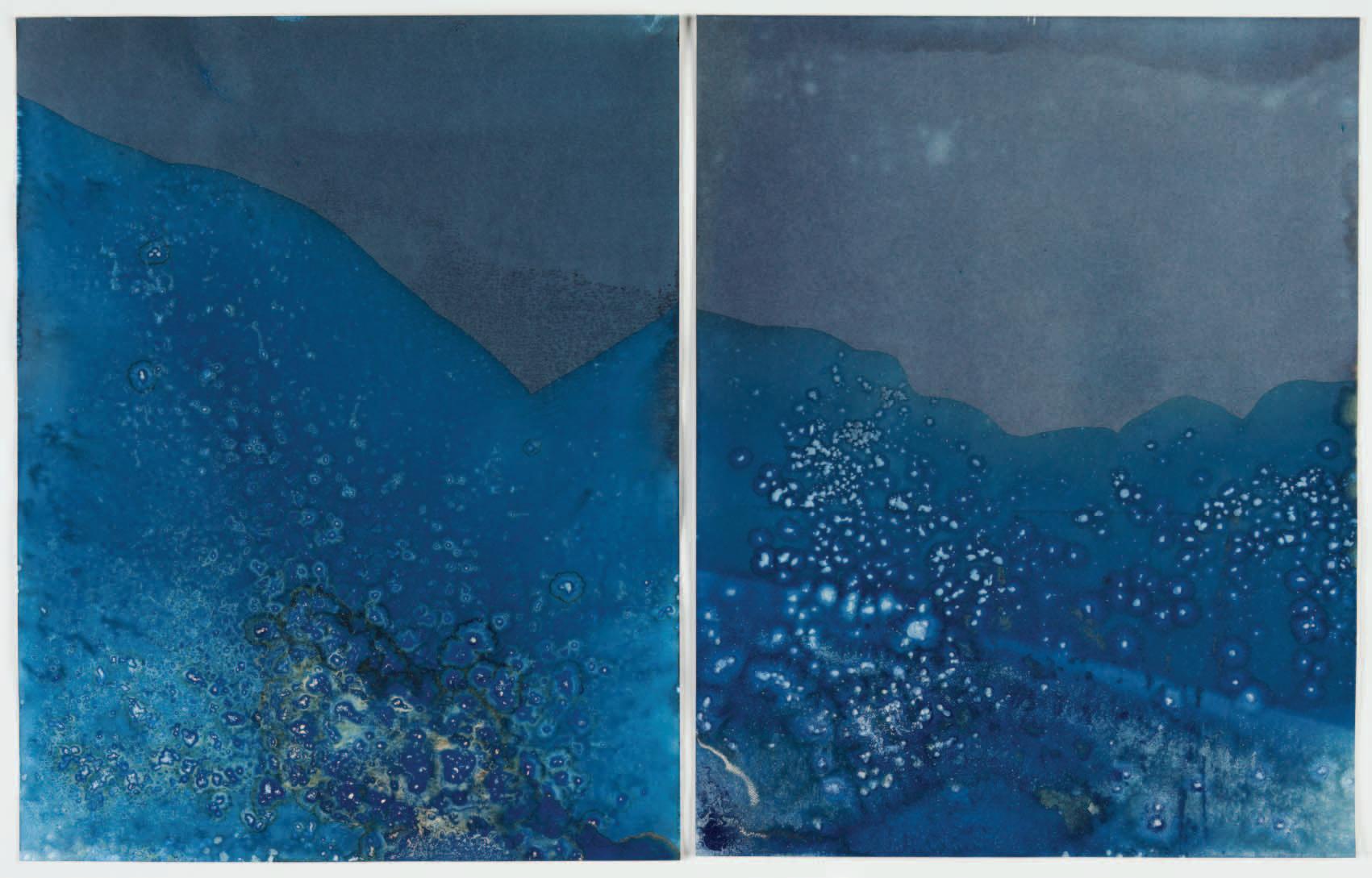

Fig. 4: Meghann Riepenhoff (American, born 1979), Littoral Drift #3 (Rodeo Beach, CA), June 13, 2013, cyanotype diptych on wove paper, overall, by sight: 70.3 × 55.5 cm (27 11/16 × 21 7/8 in.). Funded by the Douglas Cox and Edward Osowski Fund for Photography in memory of Robert A. Royka (1933–1996) and in honor of Margaret Kent Royka, 2015.44 © Meghann Riepenhoff

the water.6 In Lake Dillon, CO1 (2011), this process has created a large, red, yellow and white blotch at the center of the image, evoking an algal bloom or perhaps—for a human simile—an open sore.

Brandt allows the lake water, removed from its source, to swallow up his traditional capture of place and spit out instead a unique documentation of how place can reclaim the image-making process. By allowing elements from the landscape to affect the photograph’s surface, he suggests that the land can have its own creative voice, a reclamation that refutes the photographer’s lens and destabilizes the audience’s eye.

Even more direct is Meghann Riepenhoff’s (American, born 1979) Littoral Drift #3 (Rodeo Beach, CA), from 2013. (Fig. 4) In her series Littoral Drift, Riepenhoff uses a chemigram technique, in which light-sensitive cyanotype paper is exposed in direct contact with surf on the California coast. In her artist’s statement, Riepenhoff refers to the process as a “collaboration with the landscape and the ocean, at the edges of both,” noting further that “waves, rain, wind, and sediment… leave physical inscriptions through direct contact with photographic materials.”7 These physical inscriptions are a series of overlapping washes and speckled patterns—to the human eye, these sparkling, undulating blues evoke perhaps a starry sky, a mountain range at dusk, or an aerial view of a delta. Riepenhoff’s “collaborations” in Littoral Drift are among the most direct examples of something that could be termed a land-index in contemporary photography. As Vincent Pla-Vivas notes in his article about alternative photographies in the post-photographic era, Riepenhoff “conceives her pictures as truly indexical signs and her creative approaches exempt the photographic landscape even from the prerequisite of being created through the human gaze.”8

Not surprisingly—but nonetheless interestingly—in both Riepenhoff and Brandt’s work, the visual output of the land’s contribution is abstract. Since its explosion into the art world in the early 20th century, abstraction has been considered a product of human creative energy freed from the constraints of representation—an ego-filled art movement, in which the artist’s surroundings (ostensibly) matter little. This could leave viewers with an emotional and intellectual conundrum. Does one decide to understand the abstract element of these photographs as empirical experience—data points, signifiers of one particular place and time? Or try to read an emotional bond into the image by imagining them as beacons toward a kinder future, a collaborative Anthropocene?

Whatever an individual’s decision regarding Brandt’s and Riepenhoff's work, the juxtaposition of their images with those by Soren and Adams reveals that a 21st-century shift into the Anthropocene and a world defined by climate change will be a critical transition particularly for landscape photographers. Indeed, photographer and art theorist Ana Peraica has suggested a new term that highlights a link between the history of photography (invented during the industrial revolution) and the Anthropocene: “the Photographocene.”9 Acknowledging the complicated relationship between photography, our planet, and ourselves enriches our understanding of contemporary landscape photography, and of the increasingly nuanced, conceptual art practices that attempt to return agency to the land.

6 For a detailed explanation of Brandt’s process and its chemistry, see Virginia Heckert, Light Paper Process: Reinventing Photography, Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2015: 163.

7 Meghann Riepenhoff, “Statement,” accessed October 31, 2023, http://meghannriepenhoff.com/project/littoral-drift.

8 Vicente Pla-Vivas, “Operating in Alternative Photography: Agency through Prolonged Photographic Acts.” Journal of Visual Art Practice 20, no. 1/2 (March 2021): 71.

9 For more on this concept, see Ana Peraica, “Photographocene: The past, present and future in the photography of the environment,” Philosophy of Photography 11, nos. 1 & 2 (2020): 99-111.

17

Front and back cover details: Wu Chi-Tsung (Taiwanese, born 1981), Cyano-Collage 191, 2023, cyanotype photography, Xuan paper, acrylic gel, acrylic, mounted on brushed aluminum, panel: 225 × 60 cm (88 9/16 × 23 5/8 in.) © Wu Chi-Tsung Studio. Courtesy: the Wu Chi-Tsung Studio and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles

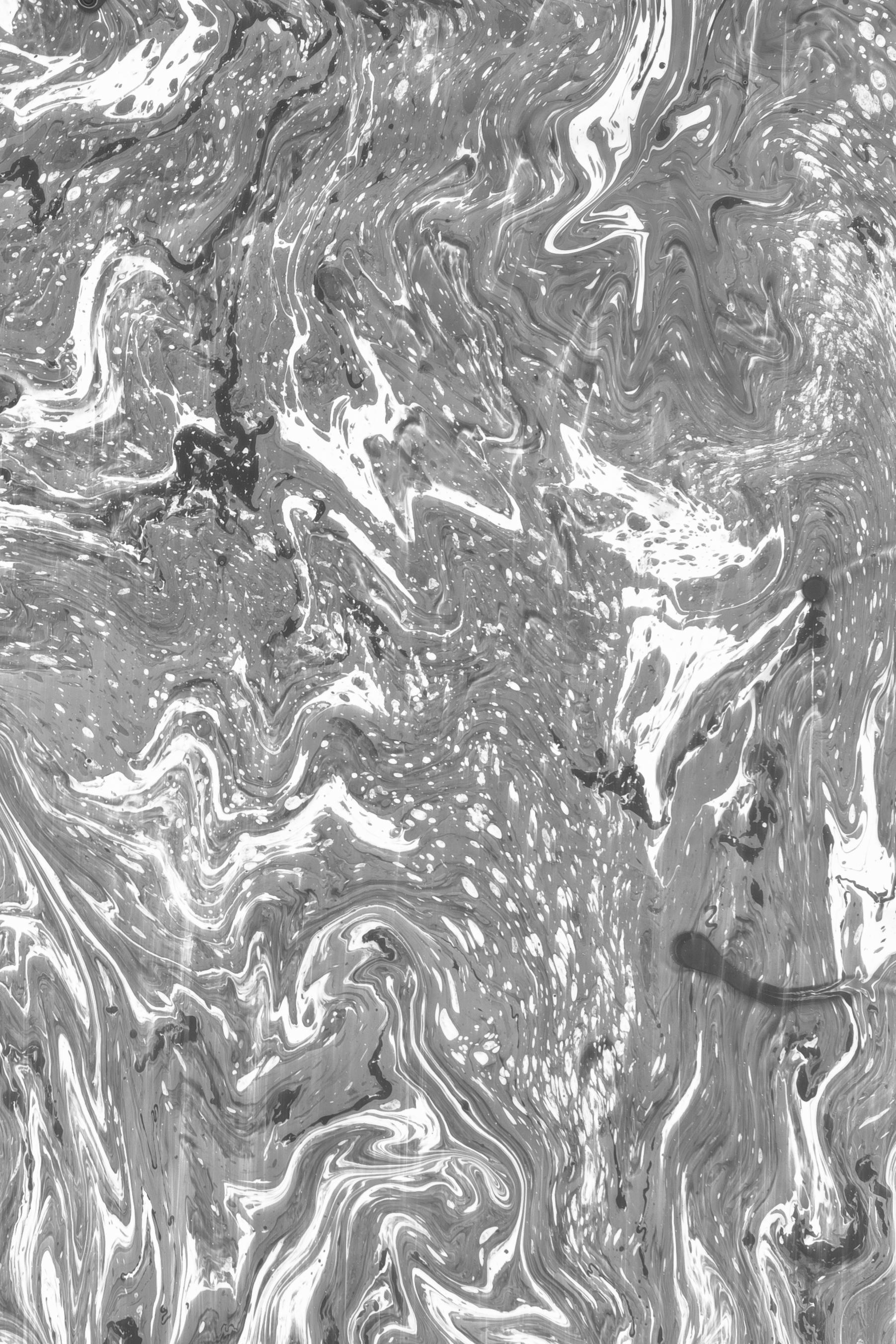

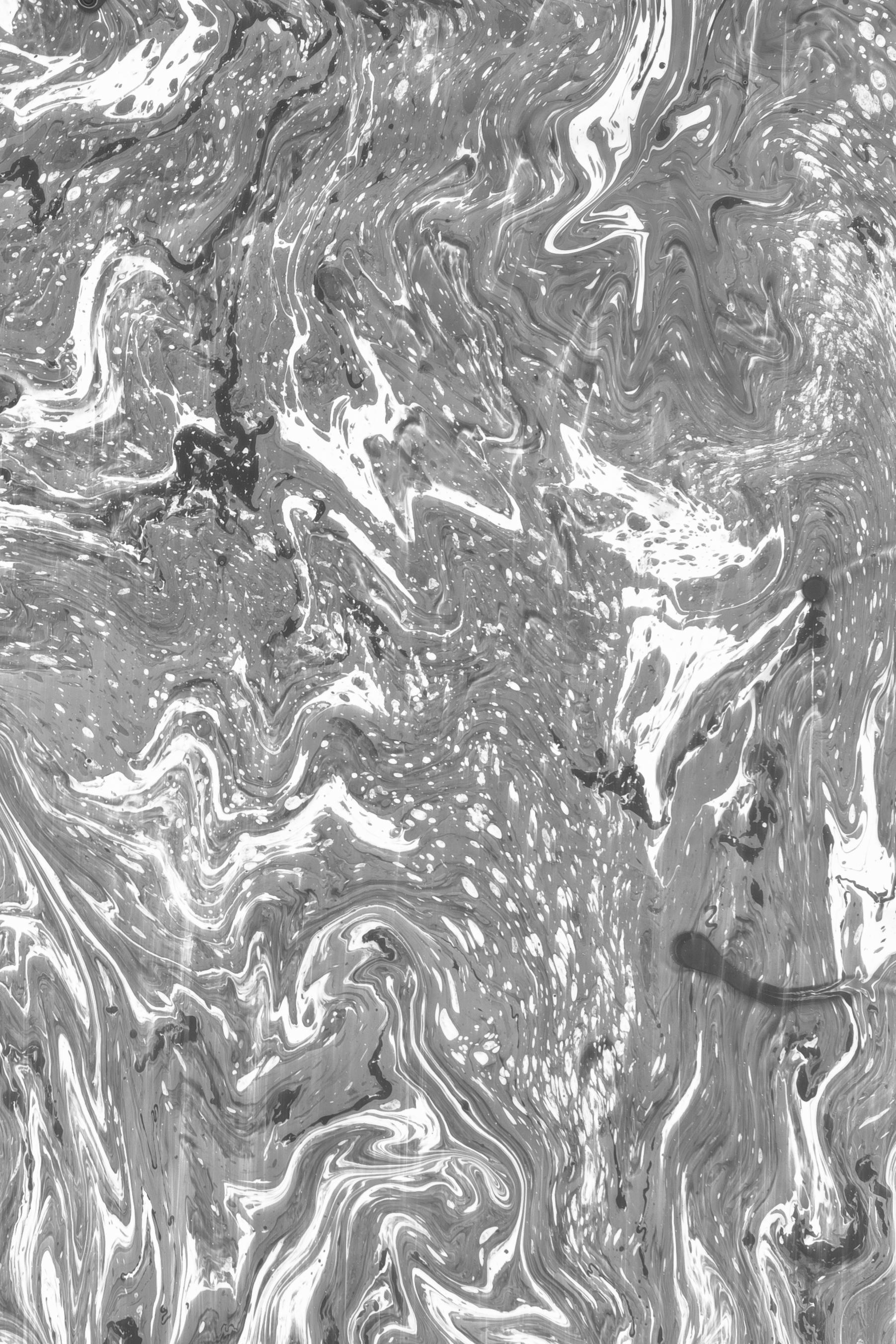

Inside front and back cover: Yael Eban and Matthew Gamber, partnership active since 2017, Yael Eban (American, born 1985), Matthew Gamber (American, born 1977), Metamorphic (4) from Marbre Vivant (detail), 2022, Photogram of ink on gelatin silver paper, unique, 101.6 × 81.3 cm (40 × 32 in.) Courtesy of the artists.

This exhibition is generously supported by the Fletcher Foundation. It is also funded in part by the Hall and Kate Peterson Fund and the Worcester Art Museum Exhibition Fund.

We also thank those who have lent or funded the purchase of works for New Terrain: Edward Osowski, James E. Hogan, Mark Nevins, Adam Ekberg, Yael Eban and Matthew Gamber, Ileana Doble Hernandez, Grant Wahlquist Gallery, Sean Kelly Gallery, New York/Los Angeles, Yang Yongliang and Galerie-B, Paris.

18

Above: Yang Yongliang (Chinese, born 1980), The Clouds from Imagined Landscape, 2022, Single channel 8K video file with audio on 85 in. screen, Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie-B, Paris, © Yang Yongliang.