Volume 25, Number 3, May 2024

Volume 25, Number 3, May 2024

Behavioral Health

303 Addressing System and Clinician Barriers to Emergency Department-initiated Buprenorphine: An Evaluation of Post-intervention Physician Outcomes

Jacqueline J. Mahal, Polly Bijur, Audrey Sloma, Joanna Starrels, Tiffany Lu

312 Factors Associated with Acute Telemental Health Consultations in Older Veterans

Erica C. Koch, Michael J. Ward, Alvin D. Jeffery, Thomas J. Reese, Chad Dorn, Shannon Pugh, Melissa Rubenstein, Jo Ellen Wilson, Corey Campbell, Jin H. Han

320 Implementation and Evaluation of a Bystander Naloxone Training Course

Scott G. Weiner, Scott A. Goldberg, Cheryl Lang, Molly Jarman, Cory J. Miller, Sarah Li, Ewelina W. Stanek, Eric Goralnick

Critical Care

325 Emergency Department SpO2/FiO2 Ratios Correlate with Mechanical Ventilation and Intensive Care Unit Requirements in COVID-19 Patients

Gary Zhang, Michael J. Burla, Benjamin B. Caesar, Carolyne R. Falank, Peter Kyros, Victoria C. Zucco, Aneta Strumilowska, Daniel C. Cullinane, Forest R. Sheppard

Education

332 Geographic Location and Corporate Ownership of Hospitals in Relation to Unfilled Positions in the 2023 Emergency Medicine Match

Zachary J. Jarou, Angela G. Cai, Leon Adelman, David J. Carlberg, Sara P. Dimeo, Jonathan Fisher, Todd Guth, Bruce M. Lo, Laura Oh, Rahul Puttagunta, Gillian R Schmitz

Emergency Department Operations

342 Imaging in a Pandemic: How Lack of Intravenous Contrast for Computed Tomography Affects Emergency Department Throughput

Wayne A. Martini, Clinton E. Jokerst, Nicole Hodsgon, Andrej Urumov

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Amin A. Kazzi, MD, MAAEM

The of MMM

The American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

Brent King, MD, MMM University of Texas, Houston

Christopher E. San Miguel, MD Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Christopher E. San Miguel, MD Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Daniel J. Dire, MD

Daniel J. Dire, MD University of Texas Health Sciences Center San Antonio

Douglas Ander, MD Emory University

Emory University

Edward Michelson, MD Texas Tech University

Edward Michelson, MD Texas Tech University

Edward Panacek, MD, MPH

Edward Panacek, MD, MPH University of South Alabama

Francesco Della Corte, MD Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria “Maggiore della Carità,” Novara, Italy

“Maggiore della Carità,” Novara, Italy

Gayle

Gayle Galleta, MD

Sørlandet Sykehus HF, Akershus Universitetssykehus, Lorenskog, Norway

Sørlandet Sykehus HF, Akershus Universitetssykehus, Lorenskog, Norway

Hjalti Björnsson, MD

Icelandic Medicine

Hjalti Björnsson, MD Icelandic Society of Emergency Medicine

Jaqueline MD

Desert

Jaqueline Le, MD Desert Regional Medical Center

Jeffrey Love, MD

The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Jeffrey Love, MD The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Katsuhiro Kanemaru, MD University of Miyazaki Hospital, Miyazaki, Japan

Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA University of Arizona, Tucson

Katsuhiro University Miyazaki, Kenneth University

Leslie Chicago Medical School

Leslie Zun, MD, MBA Chicago Medical School

Linda University of

Linda S. Murphy, MLIS University of California, Irvine School of Medicine Librarian

Niels K. Rathlev, MD Tufts University School of Medicine

Tufts University School of Medicine

Pablo Aguilera Fuenzalida, MD Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Región Metropolitana, Chile

Pablo Aguilera Fuenzalida, MD Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile

Peter A. Bell, DO, MBA Baptist Health Sciences University

Peter Sokolove, MD University of California, San Francisco

Baptist University of California, San Francisco

Rachel A. Lindor, MD, JD Clinic

Rachel A. Lindor, MD, JD Mayo Clinic

Robert Suter, DO, MHA

Robert Suter, DO, MHA UT Southwestern Medical Center

Derlet, University of California, Davis

Robert W. Derlet, MD University of California, Davis

Rosidah Ibrahim, MD

Hospital Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Rosidah Ibrahim, MD Hospital Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Scott Rudkin, MD, MBA

Scott Rudkin, MD, MBA University of California, Irvine

Elena Lopez-Gusman, JD

Elena Lopez-Gusman, JD

California ACEP

California ACEP

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE, MAAEM, FACEP

Isabelle Nepomuceno, BS Executive Editorial Director

Steven Changi

American College of Emergency Physicians

American College of Emergency

Jennifer Kanapicki Comer, MD FAAEM

AAEM School

California Chapter Division of AAEM Stanford University School of Medicine

DeAnna McNett, CAE

DeAnna McNett, CAE

Kimberly Ang, MBA

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Robert Suter, DO, MHA American College of Osteopathic

Robert Suter, DO, MHA American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians UT Southwestern Medical Center

MPH FAAEM, FACEP

Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH FAAEM, FACEP

Visha Bajaria, BS WestJEM Editorial Director

Emily Kane, MA WestJEM Editorial Director

Scott Zeller, MD University of California, Riverside

Scott Zeller, MD University

Singapore

Steven H. Lim, MD Changi General Hospital, Simei, Singapore

Terry Mulligan, DO, MPH, FIFEM ACEP Ambassador to the Netherlands Society

Terry Mulligan, DO, MPH, FIFEM ACEP Ambassador to the Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians

Wirachin MSBATS

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS

Siriraj Mahidol Bangkok,

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians School

Randall J. Young, MD, MMM, FACEP

California ACEP

UC Irvine Health School of Medicine

Jorge Fernandez, MD, FACEP

Jorge Fernandez, MD, FACEP

UC San Diego Health School of Medicine

UC San Diego Health School of Medicine

Visha Bajaria, BS WestJEM Editorial Director WestJEM

Stephanie Burmeister, MLIS WestJEM Staff Liaison

Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

American College of Emergency Physicians

Kaiser Permanente

American College of Emergency Physicians Kaiser Permanente

Physicians, :

Cassandra Saucedo, MS Executive Publishing Director

Nicole Valenzi, BA WestJEM Publishing Director

Cassandra Saucedo, MS BA WestJEM Publishing Director Casey,

June Casey, BA Copy Editor

Official Journal of the California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the America College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians, and the California Chapter of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

PubMed, Central, CINAHL, Medscape, MDLinx Editorial and Publishing Office: JEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W. Chapman Ave. Suite 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA

Available in MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central, Europe PubMed Central, PubMed Central Canada, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, eScholarship, Melvyl, DOAJ, EBSCO, EMBASE, Medscape, HINARI, and MDLinx Emergency Med. Members of OASPA. Editorial and Publishing Office: WestJEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W. Chapman Ave. Suite 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA Office: 1-714-456-6389; Email: Editor@westjem.org

of Emergency

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Emergency medicine is a specialty which closely reflects societal challenges and consequences of public policy decisions. The emergency department specifically deals with social injustice, health and economic disparities, violence, substance abuse, and disaster preparedness and response. This journal focuses on how emergency care affects the health of the community and population, and conversely, how these societal challenges affect the composition of the patient population who seek care in the emergency department. The development of better systems to provide emergency care, including technology solutions, is critical to enhancing population health.

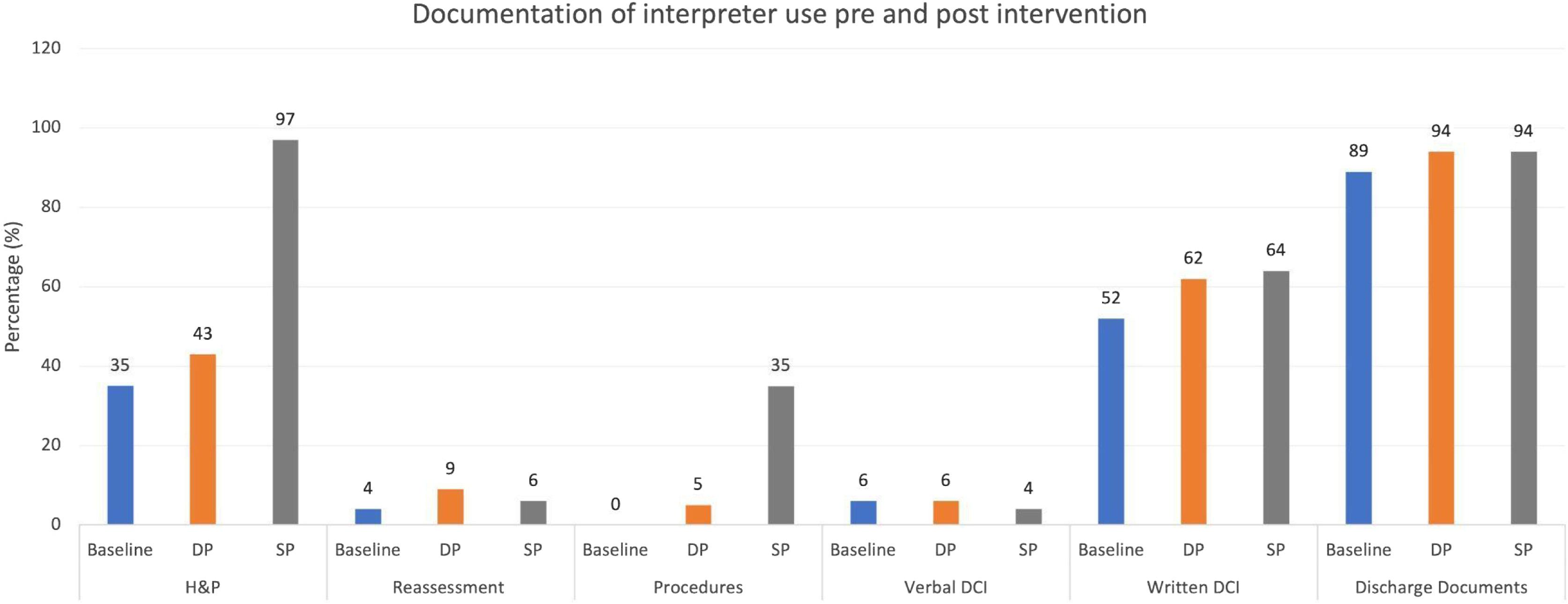

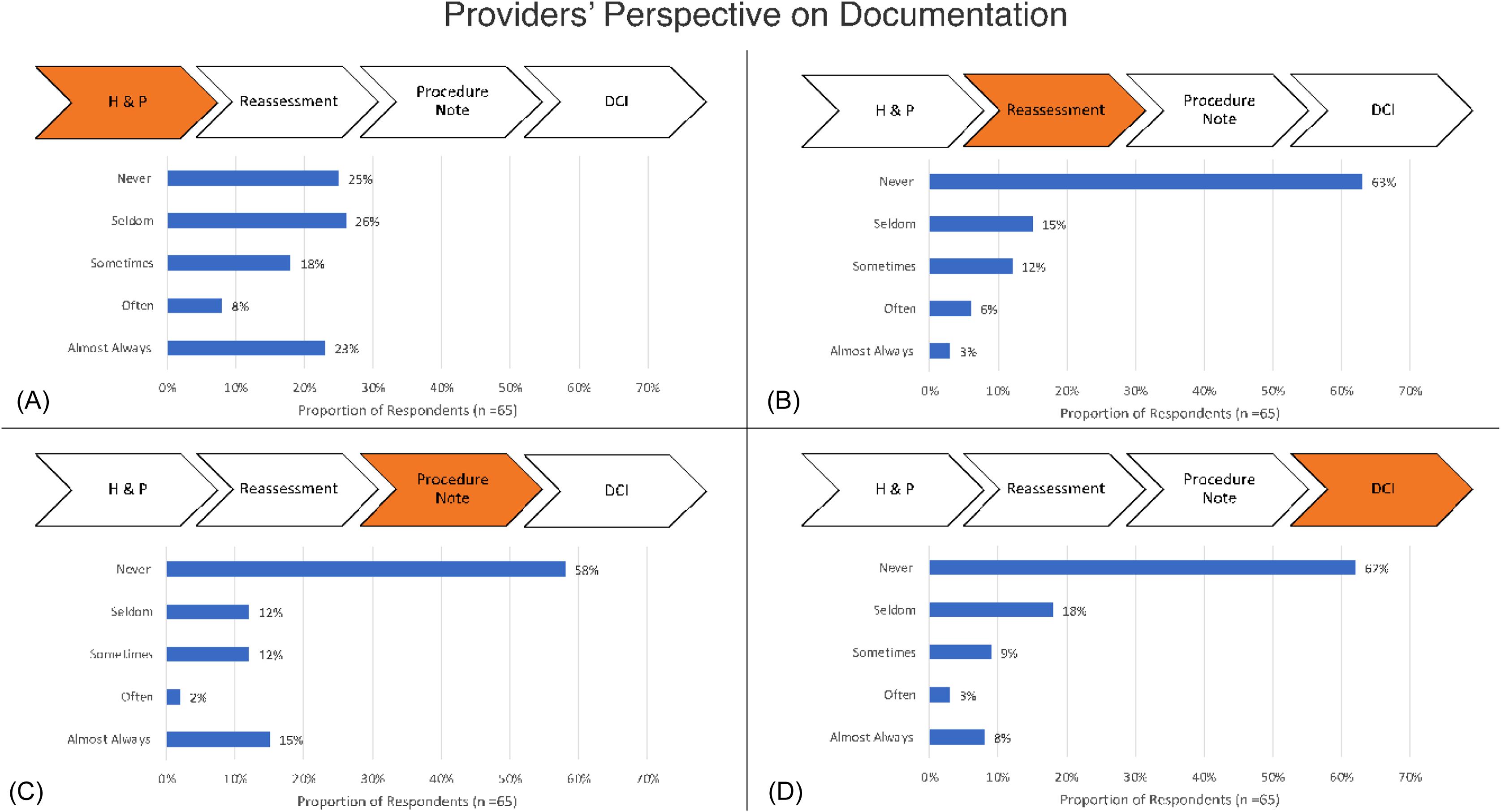

345 The Utility of Dot Phrases and SmartPhrases in Improving Physician Documentation of Interpreter Use

Katrin Jaradeh, Elaine Hsiang, Malini K. Singh, Christopher R. Peabody, Steven Straube

350 Best Practices for Treating Blind and Visually Impaired Patients in the Emergency Department: A Scoping Review

Kareem Hamadah, Mary Velagapudi, Juliana J. Navarro, Andrew Pirotte, Christopher Obersteadt

Endemic Infections

358 Association Between Sexually Transmitted Infections and the Urine Culture

Johnathan M. Sheele, Carolyn Mead-Harvey, Nicole R. Hodgson

368 Changing Incidence and Characteristics of Photokeratoconjunctivitis During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Yu-Shiuan Lin, Chih-Cheng Lai, Yu-Chang Liu, Shu-Chun Kuo, Shih-Bin Su

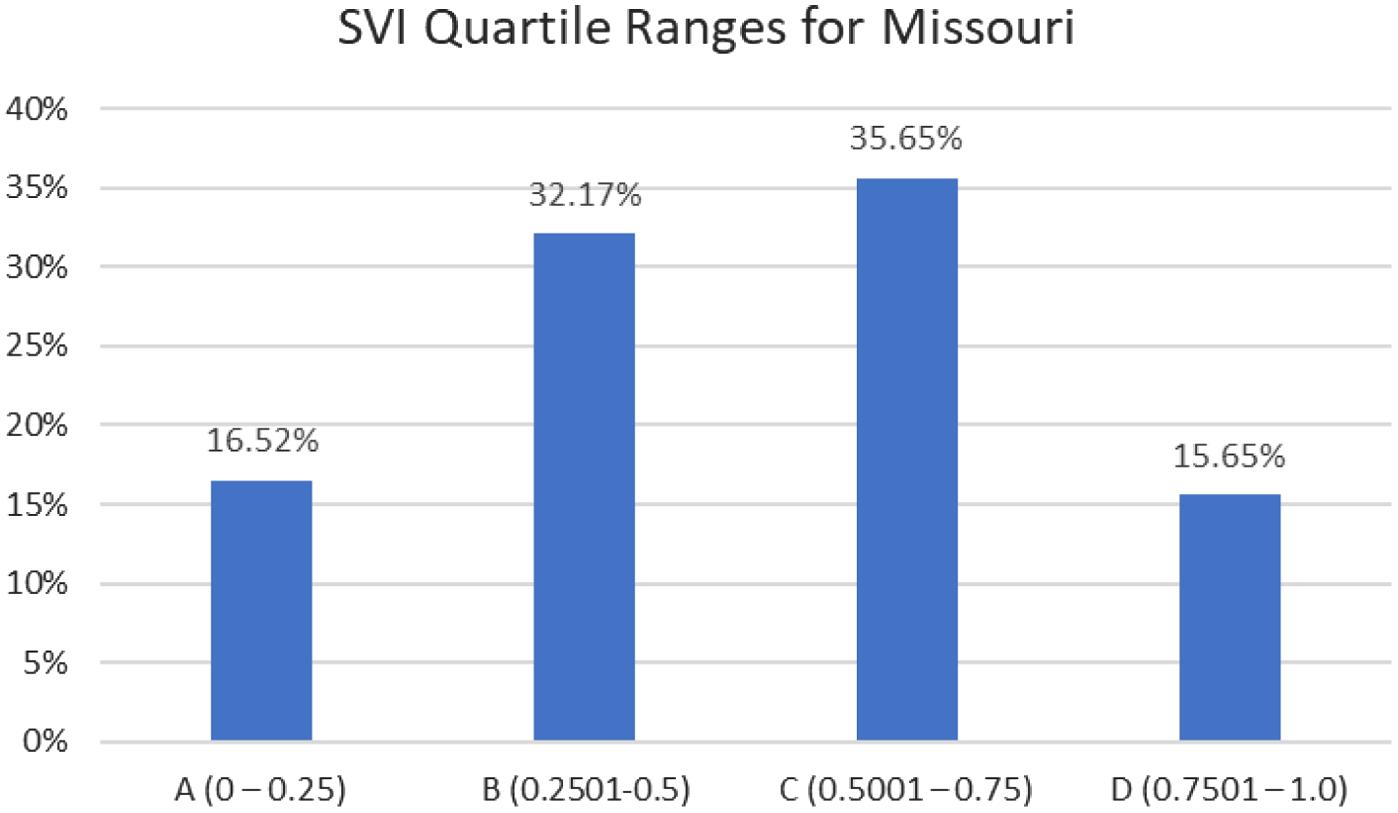

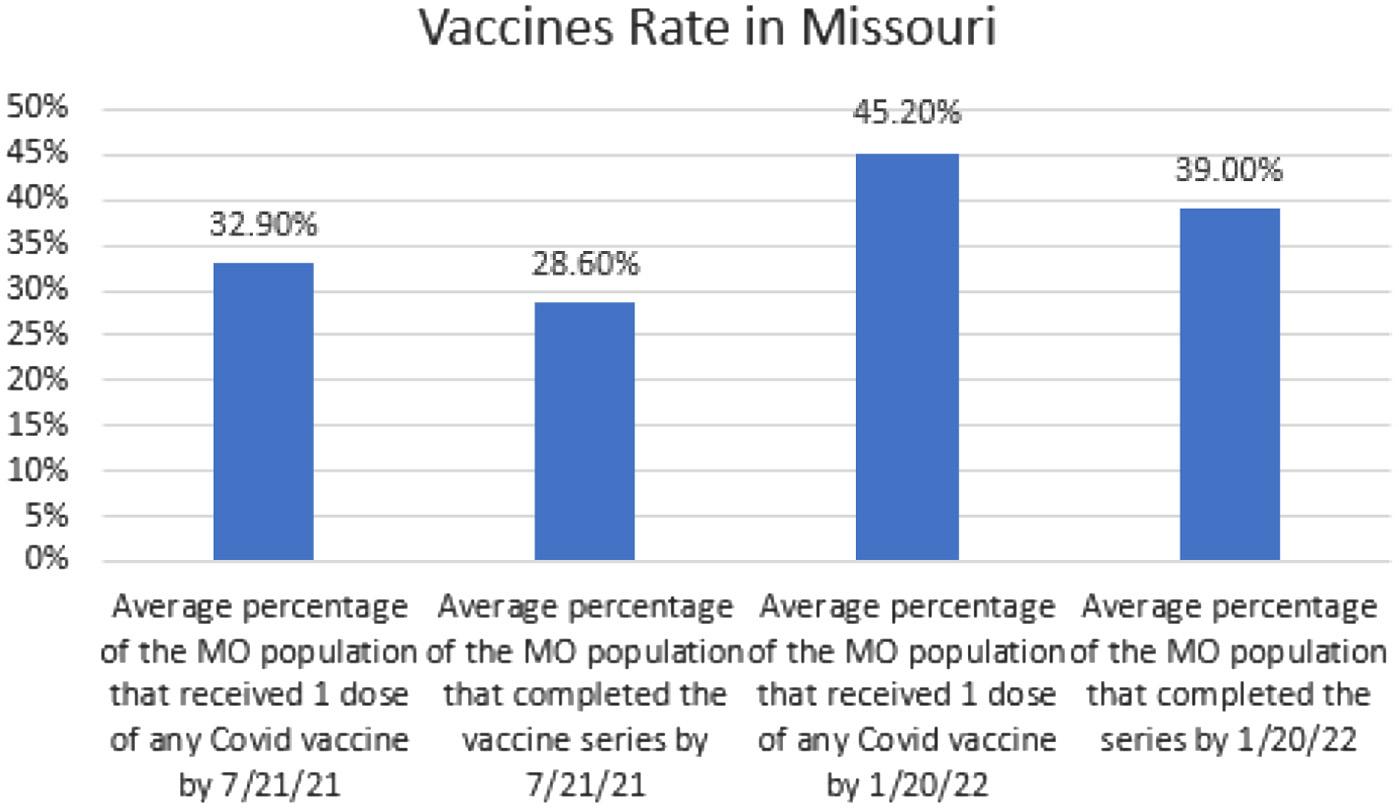

374 Operation CoVER Saint Louis (COVID-19 Vaccine in the Emergency Room): Impact of a Vaccination Program in the Emergency Department

Brian T. Wessman, Julianne Yeary, Helen Newland, Randy Jotte

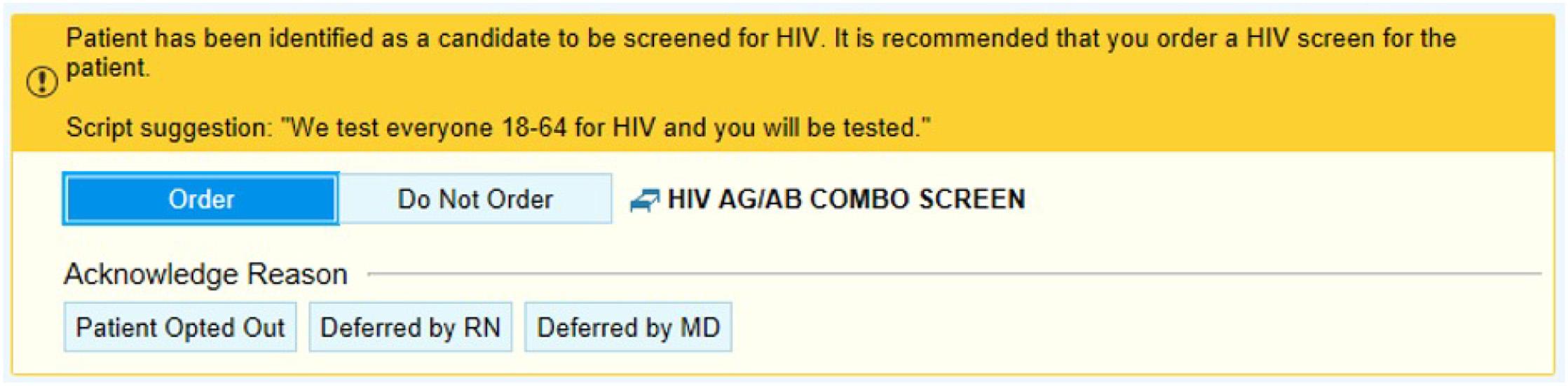

382 Sexually Transmitted Infection Co-testing in a Large Urban Emergency Department

James S. Ford, Joseph C. Morrison, Jenny L. Wagner, Disha Nangia, Stephanie Voong, Cynthia G. Matsumoto, Tasleem Chechi, Nam Tran, Larissa May

International Emergency Medicine

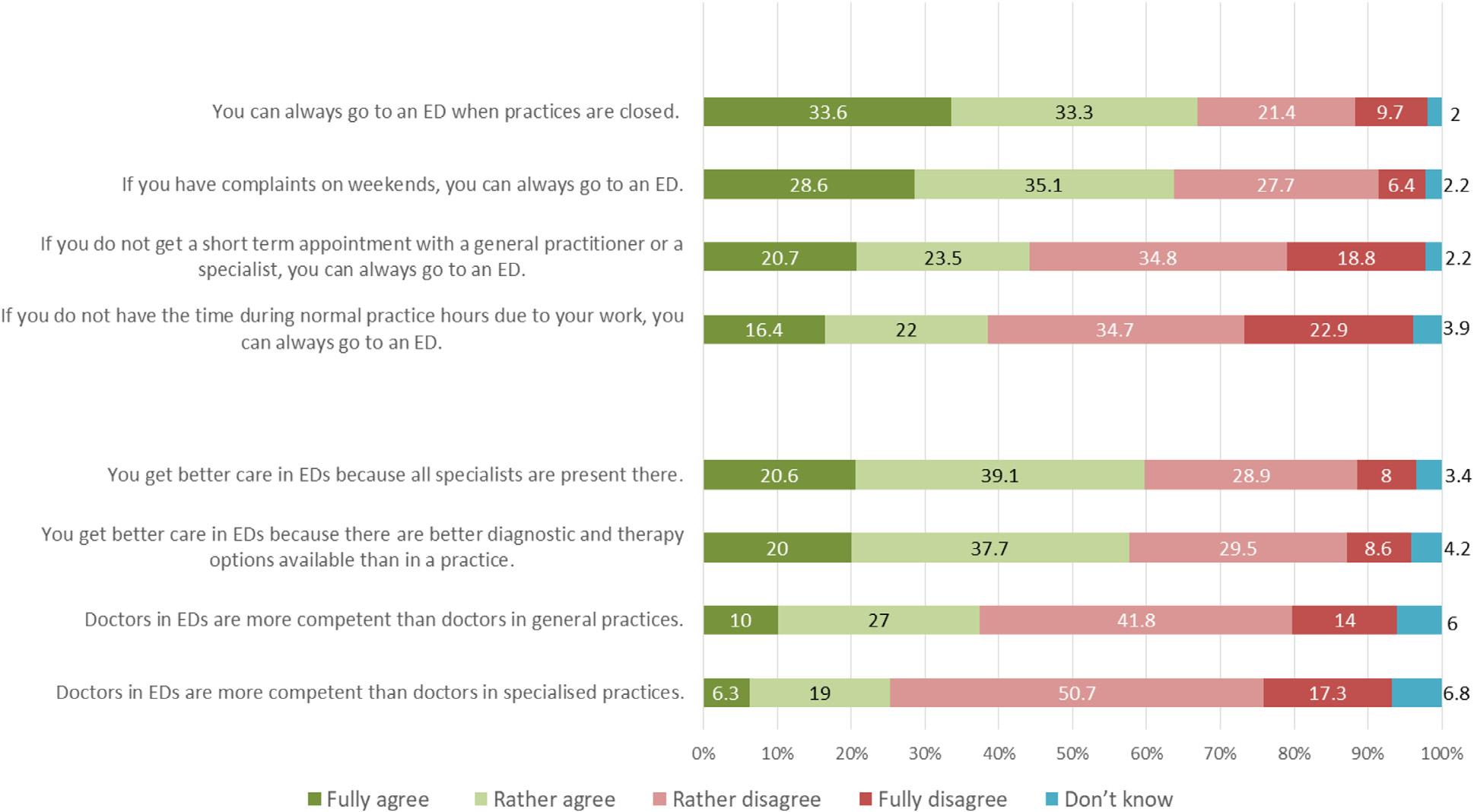

389 Public Beliefs About Accessibility and Quality of Emergency Departments in Germany

Jens Klein, Sarah Koens, Martin Scherer, Annette Strauß, Martin Härter, Olaf von dem Knesebeck

Neurology

399 Support for Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Stroke Patients on Direct Oral Anticoagulants: Mortality and Bleeding Complications

Paul Koscumb, Luke Murphy, Matthew Talbott, Shiva Nuti, George Golovko, Hashem Shaltoni, Dietrich Jehle

Pediatrics

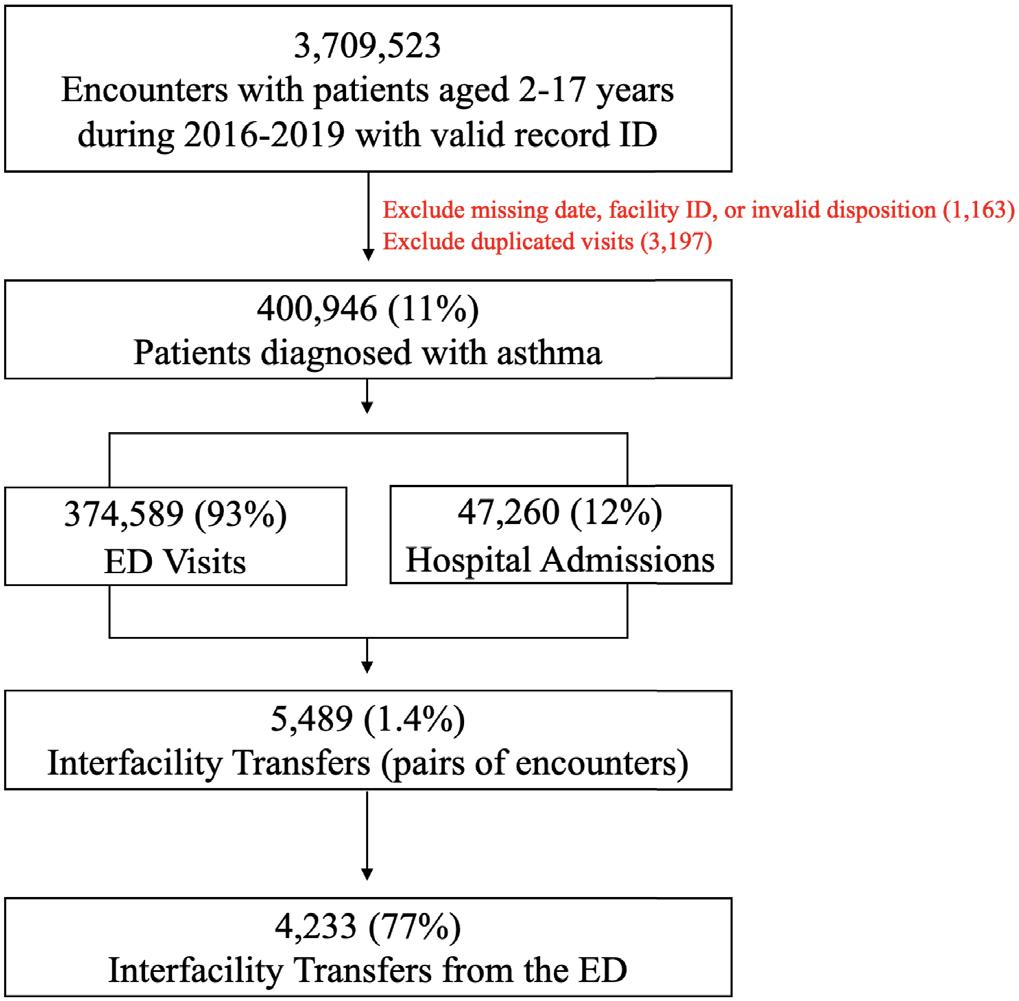

407 Patient-related Factors Associated with Potentially Unnecessary Transfers for Pediatric Patients with Asthma: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Gregory A. Peters, Rebecca E. Cash, Scott A. Goldberg, Jingya Gao, Lily M. Kolb, Carlos A.Camargo

Public Health

415 Public Health Interventions in the Emergency Department: A Framework for Evaluation

Elisabeth Fassas, Kyle Fischer, Steven Schenkel, John David Gatz, Daniel B.Gingold

Policies for peer review, author instructions, conflicts of interest and human and animal subjects protections can be found online at www.westjem.com.

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Trauma

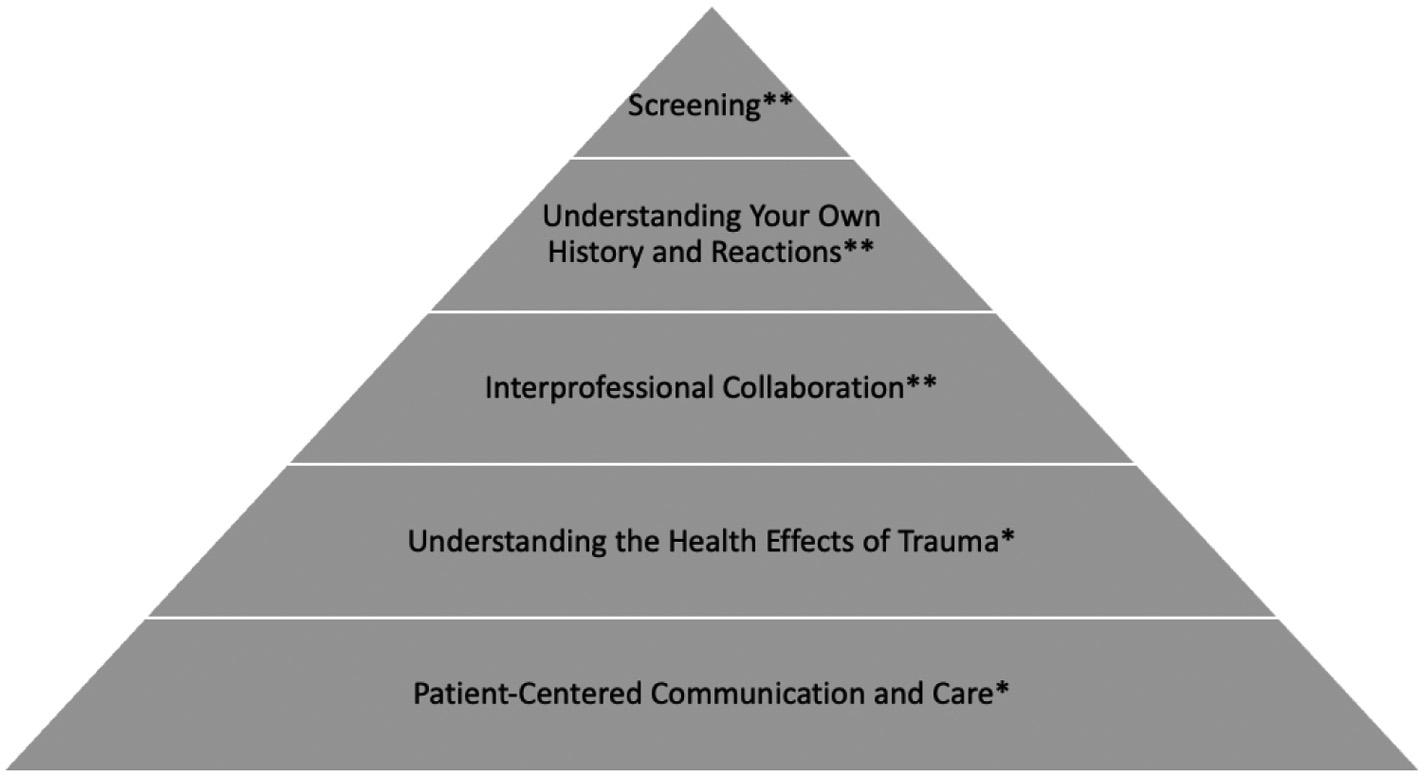

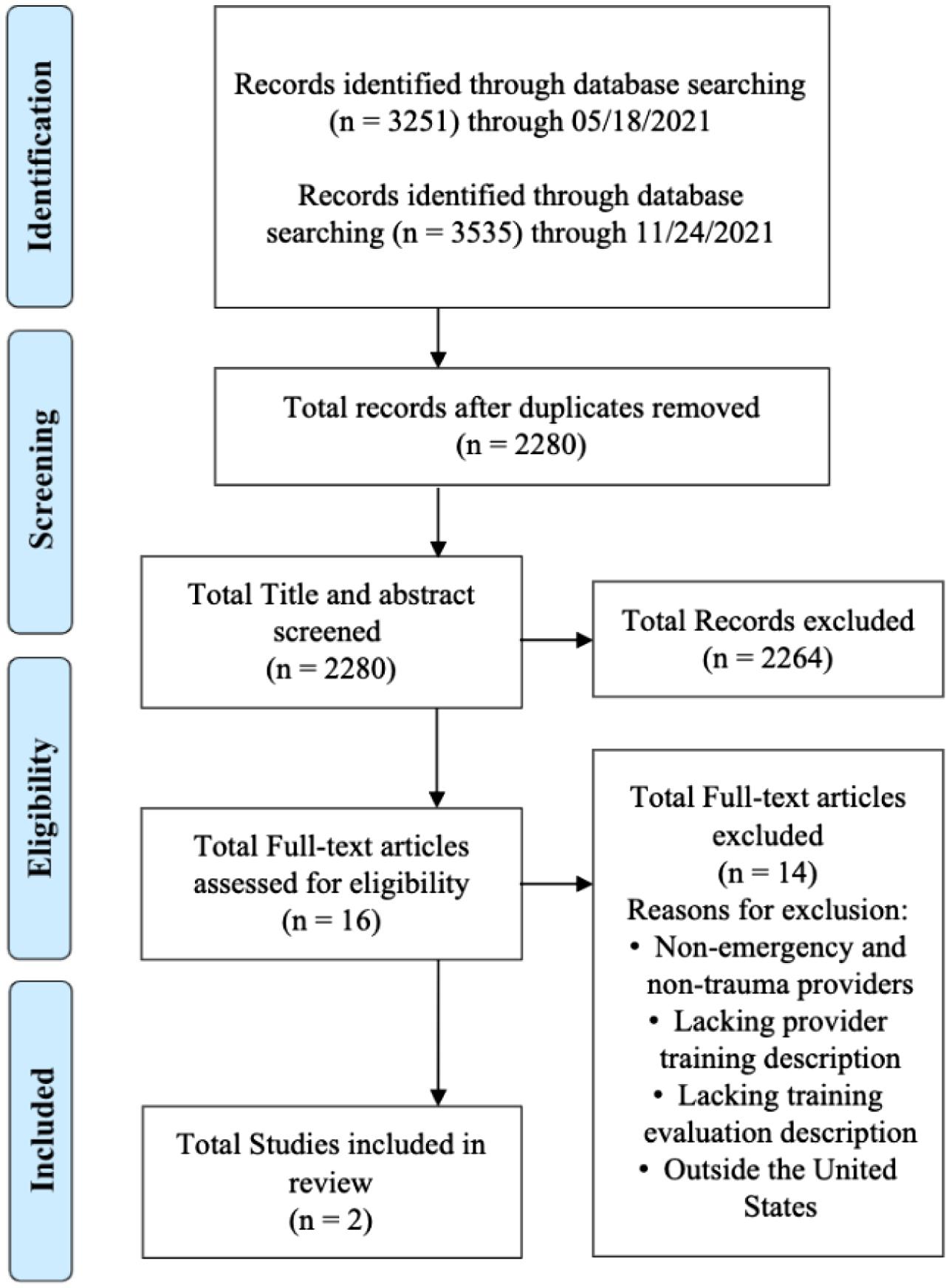

423 Trauma-informed Care Training in Trauma and Emergency Medicine: A Review of the Existing Curricula

Cecelia Morra, Kevin Nguyen, Rita Sieracki, Ashley Pavlic, Courtney Barry

Women’s Health

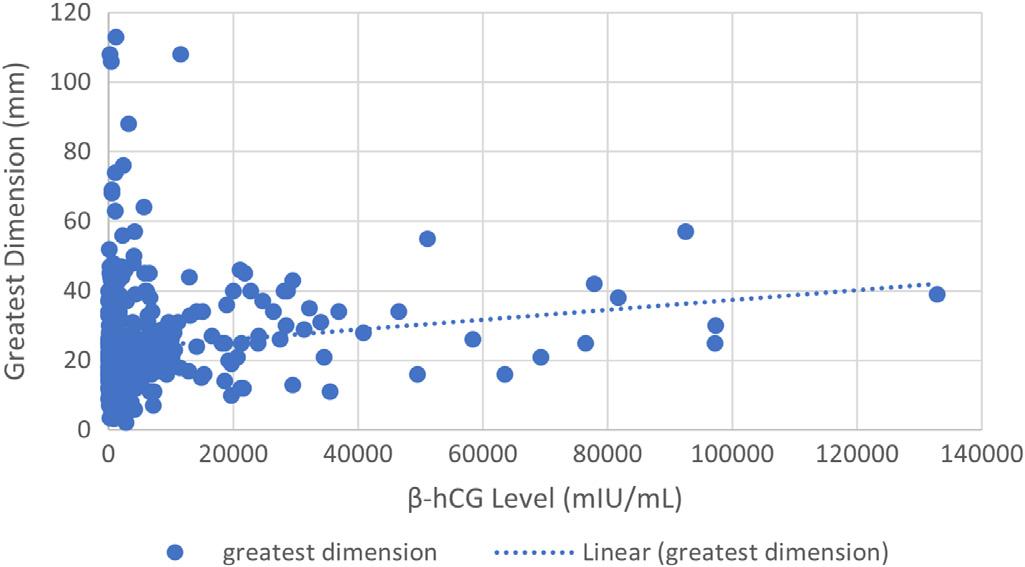

431 Relationship of Beta-Human Chorionic Gonadotropin to Ectopic Pregnancy Detection and Size

Duane M Eisaman, Nicole E. Brown, Sarah Geyer

436 Prevalence and Characteristics of Emergency Department Visits by Pregnant People: An Analysis of a National Emergency Department Sample (2010–2020)

Carl Preiksaitis, Monica Saxena, Jiaqi Zhang, Andrea Henkel

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

California American College of Emergency Physicians

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber Albany Medical College Albany, NY

Allegheny Health Network Pittsburgh, PA

American University of Beirut Beirut, Lebanon

AMITA Health Resurrection Medical Center Chicago, IL

Arrowhead Regional Medical Center Colton, CA

Baylor College of Medicine Houston, TX

Baystate Medical Center Springfield, MA

Bellevue Hospital Center New York, NY

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Boston, MA

Boston Medical Center Boston, MA

Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, MA

Brown University Providence, RI

Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center Fort Hood, TX

Cleveland Clinic Cleveland, OH

Columbia University Vagelos New York, NY

State Chapter Subscriber

Arizona Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Florida Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

International Society Partners

Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Johnstown, PA

Crozer-Chester Medical Center Upland, PA

Desert Regional Medical Center Palm Springs, CA

Detroit Medical Center/ Wayne State University Detroit, MI

Eastern Virginia Medical School Norfolk, VA

Einstein Healthcare Network Philadelphia, PA

Eisenhower Medical Center Rancho Mirage, CA

Emory University Atlanta, GA

Franciscan Health Carmel, IN

Geisinger Medical Center Danville, PA

Grand State Medical Center Allendale, MI

Healthpartners Institute/ Regions Hospital Minneapolis, MN

Hennepin County Medical Center Minneapolis, MN

Henry Ford Medical Center Detroit, MI

Henry Ford Wyandotte Hospital Wyandotte, MI

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey Lebanese Academy of Emergency Medicine Mediterranean Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

INTEGRIS Health Oklahoma City, OK

Kaiser Permenante Medical Center San Diego, CA

Kaweah Delta Health Care District Visalia, CA

Kennedy University Hospitals Turnersville, NJ

Kent Hospital Warwick, RI

Kern Medical Bakersfield, CA

Lakeland HealthCare St. Joseph, MI

Lehigh Valley Hospital and Health Network Allentown, PA

Loma Linda University Medical Center Loma Linda, CA

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans, LA

Louisiana State University Shreveport Shereveport, LA

Madigan Army Medical Center Tacoma, WA

Maimonides Medical Center Brooklyn, NY

Maine Medical Center Portland, ME

Massachusetts General Hospital/Brigham and Women’s Hospital/ Harvard Medical Boston, MA

Great Lakes Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Tennessee Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine Sociedad Argentina de Emergencias

Mayo Clinic Jacksonville, FL

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine Rochester, MN

Mercy Health - Hackley Campus Muskegon, MI

Merit Health Wesley Hattiesburg, MS

Midwestern University Glendale, AZ

Mount Sinai School of Medicine New York, NY

New York University Langone Health New York, NY

North Shore University Hospital Manhasset, NY

Northwestern Medical Group Chicago, IL

NYC Health and Hospitals/ Jacobi New York, NY

Ohio State University Medical Center Columbus, OH

Ohio Valley Medical Center Wheeling, WV

Oregon Health and Science University Portland, OR

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Hershey, PA

Uniformed Services Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Virginia Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

for Emergency Medicine

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive electronic copies for all faculty and residents, and free CME and faculty/fellow position advertisement space, please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

California American College of Emergency Physicians

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber Prisma Health/ University of South Carolina SOM Greenville Greenville, SC

Regions Hospital Emergency Medicine Residency Program St. Paul, MN

Rhode Island Hospital Providence, RI

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital New Brunswick, NJ

Rush University Medical Center Chicago, IL

St. Luke’s University Health Network Bethlehem, PA

Spectrum Health Lakeland St. Joseph, MI

Stanford Stanford, CA

SUNY Upstate Medical University Syracuse, NY

Temple University Philadelphia, PA

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, TX

The MetroHealth System/ Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, OH

UMass Chan Medical School Worcester, MA

University at Buffalo Program Buffalo, NY

State Chapter Subscriber

Arizona Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Florida Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

International Society Partners

University of Alabama Medical Center Northport, AL

University of Alabama, Birmingham Birmingham, AL

University of Arizona College of Medicine-Tucson Tucson, AZ

University of California, Davis Medical Center Sacramento, CA

University of California, Irvine Orange, CA

University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA

University of California, San Diego La Jolla, CA

University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA

UCSF Fresno Center Fresno, CA

University of Chicago Chicago, IL

University of Cincinnati Medical Center/ College of Medicine Cincinnati, OH

University of Colorado Denver Denver, CO

University of Florida Gainesville, FL

University of Florida, Jacksonville Jacksonville, FL

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey Lebanese Academy of Emergency Medicine Mediterranean Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, IL

University of Iowa Iowa City, IA

University of Louisville Louisville, KY

University of Maryland Baltimore, MD

University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA

University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI

University of Missouri, Columbia Columbia, MO

University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences Grand Forks, ND

University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE

University of Nevada, Las Vegas Las Vegas, NV

University of Southern Alabama Mobile, AL

University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA

University of Tennessee, Memphis Memphis, TN

University of Texas, Houston Houston, TX

University of Washington Seattle, WA

Great Lakes Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Tennessee Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine Sociedad Argentina de Emergencias

University of WashingtonHarborview Medical Center Seattle, WA

University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Madison, WI

UT Southwestern Dallas, TX

Valleywise Health Medical Center Phoenix, AZ

Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center Richmond, VA

Wake Forest University Winston-Salem, NC

Wake Technical Community College Raleigh, NC

Wayne State Detroit, MI

Wright State University Dayton, OH

Yale School of Medicine New Haven, CT

Uniformed Services Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Virginia Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

for Emergency Medicine

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive electronic copies for all faculty and residents, and free CME and faculty/fellow position advertisement space, please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

JacquelineJ.Mahal,MD,MBA*†

PollyBijur,PhD†

AudreySloma,MPH*

JoannaStarrels,MD,MS‡

TiffanyLu,MD,MS§

*JacobiMedicalCenter,DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine,Bronx,NewYork

† AlbertEinsteinCollegeofMedicine,DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine, Bronx,NewYork

‡ AlbertEinsteinCollegeofMedicine/Monte fi oreMedicalCenter,Departmentof Medicine,Bronx,NewYork

§ JacobiMedicalCenter,DepartmentofPsychiatry&BehavioralSciences, Bronx,NewYork

SectionEditor:MarcMartel,MD

Submissionhistory:SubmittedMay22,2023;RevisionreceivedJanuary3,2023;AcceptedJanuary4,2023

ElectronicallypublishedApril9,2024

Fulltextavailablethroughopenaccessat http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem DOI: 10.5811/westjem.18320

Introduction: Emergencydepartments(ED)areintheuniquepositiontoinitiatebuprenorphine,an evidence-basedtreatmentforopioidusedisorder(OUD).However,barriersatthesystemandclinician levellimititsuse.WedescribeaseriesofinterventionsthataddressthesebarrierstoED-initiated buprenorphineinoneurbanED.Wecomparepost-interventionphysicianoutcomesbetweenthestudy siteandtwoaffiliatedsiteswithouttheinterventions.

Methods: Thiswasacross-sectionalstudyconductedatthreeaffiliatedurbanEDswherethe interventionsiteimplementedOUD-relatedelectronicnotetemplates,clinicalprotocols,apeer navigationprogram,education,andreminders.Post-intervention,weadministeredananonymous, onlinesurveytophysiciansatallthreesites.Surveydomainsincludeddemographics,buprenorphine experienceandknowledge,comfortwithaddressingOUD,andattitudestowardOUDtreatment. Physicianoutcomeswerecomparedbetweentheinterventionsiteandthecontrolsiteswithbivariate tests.Weusedlogisticregressioncontrollingforsignificantdemographicdifferencestocompare physicians’ buprenorphineexperience.

Results: Of113(51%)eligiblephysicians,58completedthesurvey:27fromtheinterventionsite,and31 fromthecontrolsites.Physiciansattheinterventionsiteweremorelikelytospend <75%oftheirwork weekinclinicalpracticeandtobeinmedicalpracticefor <7years.Buprenorphineknowledge(including statusofbuprenorphineprescribingwaiver),comfortwithaddressingOUD,andattitudestowardOUD treatmentdidnotdiffersignificantlybetweenthesites.Physicianswere4.5timesmorelikelytohave administeredbuprenorphineattheinterventionsite(oddsratio[OR]4.5,95%confidenceinterval 1.4–14.4, P = 0.01),whichremainedsignificantafteradjustingforclinicaltimeandyearsinpractice, (OR3.5and4.6,respectively).

Conclusion: Physiciansexposedtointerventionsaddressingsystem-andclinician-level implementationbarrierswereatleastthreetimesaslikelytohaveadministeredbuprenorphineintheED. Physicians’ buprenorphineknowledge,comfortwithaddressingandattitudestowardOUDtreatmentdid notdiffersignificantlybetweensites.Our findingssuggestthatED-initiatedbuprenorphinecanbe facilitatedbyaddressingimplementationbarriers,whilephysicianknowledge,comfort,andattitudesmay behardertoimprove.[WestJEmergMed.2024;25(3)303–311.]

Opioid-relatedoverdosedeathsintheUShaveincreased sincethe1990s,andinthe12monthsendingJune2023 provisionaloverdosedeathsexceeded81,000.1 The emergencydepartment(ED)hasbeeninvolvedinaddressing theopioidcrisisbyimplementingopioid-sparingpain managementprotocolsandtreatingopioidoverdoses.Yet patientswithnon-fatalunintentionalopioidoverdosevisits totheEDarestill100timesmorelikelytodieofanoverdose withinayearoftheirindexvisitthanthosefroma demographicallymatchedpopulation.2 Emergency departmentsareintheuniquepositiontoinitiateandlinkto evidence-basedtreatmentforopioidusedisorder(OUD) whenapatientpresentsacutelywithopioidwithdrawalor non-fataloverdose.

Buprenorphine,apartialopioidagonist,isaneffective medicationtotreatOUDthathashistoricallynotbeen offeredinEDsettings.In2015,D’Onofrioetalpublisheda seminal,randomizedcontrolledstudydemonstratingthe efficacyofED-initiatedbuprenorphineandongoing engagementinOUDtreatmentat30-dayspostdischarge.3 Follow-upstudiesalsodemonstratedthatED-initiated buprenorphineisaneffectiveintervention,withongoing OUDtreatmentat30daysin50–86%ofthepatients.4,5 On theheelsofthese findings,theSubstanceAbuseandMental HealthServicesAdministrationpublishedaresourceguidein 2021acknowledgingtheEDasanimportantsitefor provisionofOUDtreatment.6 Inthesameyear,the AmericanCollegeofEmergencyPhysicianspublished consensusrecommendationsforOUDtreatmentincluding useofbuprenorphineintheED.7

WhilebuprenorphineuseintheEDhasincreasedinrecent years, 8 multiplebarriersatthesystemandclinicianlevellimit theimplementationofED-initiatedbuprenorphine.9–13 System-levelbarriersincludelackofstreamlinedordersets forOUDtreatment,difficultyreferringtoongoingtreatment servicesafterdischarge,limitedavailabilityofexpert physiciansandpharmacistsforconsultation,andlackof accesstodedicatedcarecoordinators,socialworkers,orpeer counselors.Clinician-levelbarriersincludelackof knowledge,comfortandexperiencewithbuprenorphineand OUDtreatment,ahistoricalneedforabuprenorphine prescribingwaiver,14 aswellasstigmatowardpatients withOUD.

Fewstudieshaveexaminedspecificinterventionsthat addressclinician-levelbarriersandpost-intervention clinicianoutcomes.Fosteretaldescribeda financial incentiveprogramforemergencyphysicianstocompletethe then-requiredbuprenorphinewaivertrainingandreporteda positivebutvariableincreaseinbuprenorphineprescribingin the fivemonthsaftertheincentive.14 Butleretalreportedona setofbehavioral-scienceinformedinterventionsthat increasedphysicianinitiationofOUD-relatedtreatments15

PopulationHealthResearchCapsule

Whatdowealreadyknowaboutthisissue?

WhileED-initiatedbuprenorphineforthe treatmentofopioidusedisorderhas increased,system-andclinician-levelbarriers continuetolimititsuse.

Whatwastheresearchquestion?

Wesoughttocomparewhetherinterventions addressingbarrierstoED-initiated buprenorphinewouldimproveadministration ofbuprenorphine.

Whatwasthemajor findingofthestudy?

Physiciansattheinterventionsitewere 4.5timesmorelikelytohaveadministered buprenorphine(95%CI1.4 – 14.4,P = 0.01).

Howdoesthisimprovepopulationhealth?

ED-initiatedbuprenorphinecanbefacilitatedby addressingbothsystem-andclinician-level barriers,althoughphysicianknowledge, comfort,andattitudesmaybehardertoimprove.

atasingleacademicEDsitewitharobustaddictionclinic program.Khatrietalrandomizedphysicianstoaclinicianlevelinterventionofeitheradidactic-onlygrouporadidactic plusweeklymessaginganda financialincentivegroup.16 While33%ofallparticipantsprescribedbuprenorphinefor the firsttimeinthe90dayspost-intervention,buprenorphine administrationfrequencyorknowledgedidnotdiffer significantlybetweenthegroups.Inanongoing,multicenter effectivenessstudyofbuprenorphineinitiationintheED, D’Onofrioetaldescribedmultiplesystem-level implementationfacilitatorsthatincludeclinicalprotocols, learningcollaboratives,andreferralprograms.17,18 The implementationfacilitationperiodwasassociatedwitha highernumberofemergencyclinicianswhocompletedthe buprenorphineprescribingwaiver,aswellasEDvisitswhere cliniciansprescribedbuprenorphineandnaloxone.19

Wecontributetothegrowingbodyofliteratureby describingasetofinterventionsthataddressedmultiple system-andclinician-levelimplementationbarrierstoEDinitiatedbuprenorphineinasafety-netED.Weevaluated post-interventionphysicianoutcomesandcomparedthese betweentheEDsitewithtargetedinterventionsandtwo relatedsiteswithouttargetedinterventions.Ouraimwasto determinewhetheraddressingmultipleimplementation

barrierstoED-initiatedbuprenorphineisassociatedwith improvedbuprenorphineknowledge,comfortwith addressingOUD,andattitudestowardOUDtreatment amongphysiciansattheinterventionsite.Wehypothesize thatphysiciansattheinterventionsitehadimproved experiencewithadministeringbuprenorphineintheED.

Weconductedacross-sectionalstudyofattending physiciansatthreeEDsaffiliatedwithalarge,urban emergencymedicine(EM)residencyprogram.Physician knowledge,comfortwith,andattitudestowardOUD treatment,aswellasexperiencewithadministering buprenorphineintheED,werecomparedbetweenone interventionsite(whereamultifacetedsetofinterventions aimedataddressingclinician-andsystem-levelbarriersto ED-initiatedbuprenorphinewasimplemented)vstwo controlsites(whereinterventionsfocusedonED-initiated buprenorphinewerenotimplemented).Thestudywas approvedbytheaffiliatedinstitutionalreviewboards (IRB#2019-10920).

ThisstudytookplaceatthreeEDsaffiliatedwithalarge academicEMtrainingprogramwith84residentsperyear and100full-timeattendingphysiciansonfaculty.OneED siteispartoftheNewYorkCitymunicipalhospitalsystem, whiletheothertwoEDsitesarepartofalarge,private, academichealthsystem.AllthreeEDsseeahighvisitvolume around70,000perannumpersiteandprovidesafety-netcare toapayormixthatispredominantlypubliclyinsured.All threeEDsareintheboroughofTheBronx,NewYork, wheretheopioid-relatedoverdoseratewas73.6per100,000 in2022,representingthehighestofall fiveboroughsinNew YorkCity.20 ConsistentwithmostEMpracticesacrossthe country,thethreeEDtrainingsiteshavenothistorically offeredbuprenorphineforopioidwithdrawaland OUDtreatment.

BetweenNovember2018–June2020,themunicipal hospital-basedEDsite(hereinreferredtoas “intervention site”)implementedamultifacetedsetofinterventionsto addresssystem-andclinician-levelbarrierstoED-initiated buprenorphine.System-levelinterventionscustomizedforthe EDincludedthefollowing:1)anelectronichealthrecord (EHR)notetemplateforopioidwithdrawalandOUD assessment;2)aclinicalprotocolforadministering buprenorphineintheED;3)aclinicalworkflowtoprovide naloxonetrainingandtake-homekitsforoverdose prevention;and4)apeernavigationprogramtofacilitate referralandlinkagetooutpatientbuprenorphinetreatment, includinganin-housesubstanceusedisordertreatment

program.System-levelinterventionswerefundedand developedbyacentralizedleadershipteamfromthemunicipal publichospitalsystem.LocalEDimplementationwas facilitatedbyaclinicianchampion(JM)whoworkedclosely withaninterdisciplinaryteamofemergencymedicine, behavioralhealth,pharmacy,andsocialworkleadership. Initialsalarysupportforthisworkwasgrant-funded.

Clinician-levelinterventionsincludedthefollowing:1)a modest financialincentiveforvoluntarycompletionof buprenorphinewaivertrainingandobtainingtheprescribing waiver;2)regularupdatesandremindersaboutsystem-level interventionsatEMfacultymeetingseverytwoweeks;and 3)two,one-hourgrandroundslecturesthatreviewedthe evidenceforED-initiatedbuprenorphineandtheavailability ofclinicalprotocolstosupportbuprenorphinetreatment. Grandroundslecturesatthetimeofinterventionwere conductedinpersonandvoluntarilyattendedbyfacultyand residentsacrosstheEMresidencyprogram.Manyofthe interventionswereintroducedinanoverlappingmannerand refinediterativelyduringthetwo-yearimplementationperiod.

Duringthesameperiod,aclinicalprotocolandanorder settosupporthospital-initiatedbuprenorphinewerealso beingimplementedatthetwootherEDsitesbasedatthe private,academichealthsystem(referredtoas “thecontrol site”);however,theseinterventionsdidnotfocusontheED. PeernavigatorsbasedintheEDwereavailablebutwerenot dedicatedtosupportreferralandlinkagetooutpatient buprenorphinetreatment.Neitherwere financialincentives forcompletionofbuprenorphinewaivertrainingor physicianmeetingsdedicatedtoED-initiated buprenorphineoffered.

Werecruitedstudyparticipantsbasedonthefollowing criteria:1)licensedphysicianeligibletoobtainawaiverto prescribebuprenorphine;and2)attendingphysicians practicingateithertheinterventionorcontrolsite.Wedid notincluderesidentphysiciansinoursamplebecausethey rotateatboththeinterventionandcontrolsitesandwould haveexperiencedvariableexposuretotheinterventions aimedatED-initiatedbuprenorphine.Neitherdidweinclude physicianassistantswhoareanimportantpartoftheEM workforcebecausetheydidnotreceivethe financialincentive anddidnotattendfacultymeetingsorgrandroundswhere mostoftheclinician-facinginterventionsoccurred.

BetweenSeptember–December2020,weemailed113 eligibleemergencyphysiciansatthethreeEDsitesto introducetheopt-instudyandcontinuedtosendmonthly emailreminders.Wealsoannouncedthestudyinpersonat attendingphysicianmeetingsattwoofthethreesitesthat

couldallocatemeetingtimeduringtheCOVID-19public healthemergency.Individualizedemailremindersweresent toattendingphysiciansatallsitesinthelastmonthofstudy recruitment.Thesurveywasadministeredanonymouslyin EnglishusingtheonlineplatformQualtrics(Qualtrics, Provo,UT).Uponcompletionofthequestionnaire, participantswereeligibletoenteraraffletowinoneof five $50giftcards.

A22-itemsurveywasadaptedfrompreviouslypublished researchonclinicianbarrierstobuprenorphine prescribing.9,11 Thesurveyinstrumentwedeveloped consistedof fivedomains:demographics;buprenorphine experience;buprenorphineknowledge;comfortwith addressingOUD;andattitudestowardOUDtreatment.

Self-reporteddemographicsincludedage,gender,race, ethnicity,yearsinpractice,andamountoftimespent workingclinically(clinicaltime).Thenumberofyearsin practicewasmeasuredbythenumberofyearssince AmericanBoardofEmergencyMedicinecertificationdate, andrespondentswereconsideredjuniorattendingphysicians iftheyhadsevenorfeweryearsinpractice.Clinicaltimewas adichotomousmeasureoflessthanvs ≥ 75%,basedonthe rationalethatattendingphysicianswhospend <75%clinical timerepresentclinician-educators,researchers, oradministrators.

Forbuprenorphineexperience,participantswereaskedto answeryes/notoeveradministeringbuprenorphineinthe ED,completingthebuprenorphinewaivertraining,and receivingtheirbuprenorphineprescribingwaiver. Buprenorphineknowledgewasevaluatedwithseven questionsspecifictotheclinicaluseofbuprenorphineusinga three-pointLikertscale(“agree-neutral-disagree”),where agreeingordisagreeingcorrectlytotheknowledgequestions wasakeyoutcome.ComfortwithOUDtreatmentwasalso evaluatedwithathree-pointLikertscale(“comfortablesomewhatcomfortable-notcomfortable”)regarding managementofopioidwithdrawal,responsetoopioid overdose,counselingonandadministeringmedicationsfor OUD,andreferraltooutpatienttreatmentforsubstanceuse disorder.AttitudestowardOUDtreatmentweremeasured withlevelofagreement(“agree-neutral-disagree”)to stigmatizingstatementsdescribingpatientswithOUDas difficulttotreat,buprenorphineassubstitutingonedrugfor another,andprescribingbuprenorphineforOUDas increasingmedicolegalrisk.

Wecalculateddescriptivestatisticsfordemographic characteristics,buprenorphineexperience,and buprenorphineknowledgeforphysiciansattheintervention andcontrolsites.Fisherexacttestswereusedtoassess whetherphysicians’ demographiccharacteristicsand buprenorphineexperiencedifferedbysite.Weexamined buprenorphineknowledgebycalculatingacomposite

knowledgescorebasedonthenumberofcorrectanswersto thesevenknowledgequestionsandcomparedthembysite usingtheMann-WhitneyU-test.Physicians’ comfortwith addressingOUDandattitudestowardOUDtreatmentare describedwithproportionofresponseswith “comfortable” and “ agree, ” andcomparedbysitewithFisherexacttestsand Fisher-Freeman-Haldentests,forvariableswithmorethan twocategories.

Weconductedapost-hocmultivariableanalysisbecause ofastatisticallysignificantdifferencebetweenphysicians’ buprenorphineexperienceof “everadministered buprenorphine” bysite.Weexaminedpossibleconfounding ofthisassociationbythedemographiccharacteristicsthat aresignificantlyassociatedwiththesite.Weusedlogistic regressiontoassesstheassociationbetweenbuprenorphine administrationandsitewhilecontrollingforthesecovariates. Followingtherecommendationthatonevariableshouldbe usedforevery10participantswiththeoutcome,we ascertainedthatonlytwovariablescouldbeincludedina singleanalysisastherewere20participantswhohad “ ever administeredbuprenorphine.” Thus,werananalyseswith siteandeachofthepossibleconfoundersseparately.Alltests weretwo-sidedwithastatisticalsignificancecriterionof0.05. WeusedSPSSversion27(IBMCorp,Armonk,NY)forall statisticalanalyses.

Amongthe113eligibleattendingphysicians,58(51.3%) physiciansfullycompletedthesurvey,with27responses fromtheinterventionsiteand31responsesfromthecontrol site.Asshownin Table1,nosignificantdifferencesinthe demographiccharacteristicsofgender,race,andethnicity werefoundamongemergencyphysiciansbysite.Physicians weremorelikelytospend <75%oftimeinclinicalpracticeat theinterventionvscontrolsites,44.4%vs19.4%,respectively (P = 0.05).Nearlytwiceasmanyphysiciansatthe interventionsitewereinclinicalpracticeforsevenyearsor lesscomparedtothoseatthecontrolsite,70.4%vs38.7%, respectively(P = 0.02).Inotherwords,physiciansatthe interventionsiteweremorelikelytobeclinician-educators, researchersandadministrators,andjunior attendingphysicians.

Forbuprenorphineexperience,morephysiciansatthe interventionsitereported “everadministered buprenorphine” intheirclinicalpracticethanphysiciansat thecontrolsite,51.9%vs19.4%,respectively(P = 0.01).Over halfofthephysicianrespondentscompletedthewaiver trainingatboththeinterventionandcontrolsites,55.6%and 51.6%,respectively.Ofthosewhocompletedthewaiver training,mostphysiciansobtainedtheprescribingwaiver. Therewasnostatisticaldifferenceinwaivertraining completionandstatusbysite.Forbuprenorphine knowledge,themedianscoreofcorrectanswers(oftheseven knowledgequestions)wasthreeforphysiciansatthe

Table1. Demographic,experience,andknowledgeparticipantcharacteristics.

Demographiccharacteristics

Gender

Interventionsite N = 27n(%) Controlsites N = 31n(%) P-value

White 17(63.0%)22(75.9%)

Black 3(11.1%)3(10.3%)

Asian 2(3.7%)3(10.3%)

Other 2(7.4%)1(3.4%) Declinetoanswer4(14.8%)1(3.4%)

Obtainedprescribingwaiveramongthosewhocompletedwaivertraining0.74

Yes 12(80.0)12(75.0)

No 3(20.0)4(25.0)

Buprenorphineknowledge

Mean(SD)numberofcorrectresponses(7items)3.4(2.0)3.3(2.1)0.82 Median(range)3(0–7)4(06)0.88

*Statisticalsignificancewithp-valueforcomparison(p < .05).

interventionsite,whichwassimilartothemedianscoreof fouratthecontrolsite(Mann-WhitneyU = 428, P = 0.88). Asseenin Figures1 and 2,physicians’ comfortwith addressingOUDandtheirattitudestowardOUDtreatment didnotdiffersignificantlybetweentheinterventionand controlsites.

Thepost-hocanalysis(see Table2)oftheassociation betweenbuprenorphineadministrationandsiteindicates thatphysiciansattheinterventionsitewere4.5timesmore

likelytohaveadministeredbuprenorphinethanthoseatthe controlsite(OR4.5,95%CI1.4 – 14.4, P = 0.01).After adjustingforthetwodemographiccharacteristicsthat differedbysite(clinicaltimeandyearsinpractice),the likelihoodofbuprenorphineadministrationremainedhigh andstatisticallysignificantamongphysiciansatthe interventionsitecomparedtothecontrolsite(OR3.5 withclinicaltimecontrolled,4.6withyearsinpractice controlled,respectively).

Trea ng opioid withdrawal with buprenorphine will extend pa ent length of stay in the Emergency Department

Providing pa ents with buprenorphine for OUD will increase my medicolegal risk

Buprenorphine is subs tu ng one drug for another

Pa ents who have a history of OUD are difficult to treat

The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) is difficult to administer

PercentAgree(%)

Figure1. Physicianattitudestowardspatientslivingwithopioidusedisorder(OUD)1 anduseofbuprenorphinebysite(percentagree.)

Physicianagreementwiththestatementsalongtheverticalaxisbysite.Nostatisticaldifferencefound.

DISCUSSION

Inthisstudy,wefoundthatemergencyphysicianswho wereexposedtoamultifacetedsetofinterventionsthat addressedsystem-andclinician-levelbarrierstoED-initiated

Refertooutpa entsubstanceuse treatmentprograms

Counselpa entsaboutnaloxone take-homekits

Administermethadone

Administerbuprenorphine

Discussmedica onsforOUD

Respondtoopioidoverdose

TreatOpioidwithdrawal

buprenorphineattheirclinicalsitewereatleastthreetimesas likelytohaveadministeredbuprenorphineafteradjustingfor clinicaltimeandyearsinpractice.Yetphysicians’ buprenorphineknowledge,comfortwithaddressingOUD,

ControlSite Interven onSite

Percent(%)comfort

Figure2. Physicianpercentcomfortwithaddressingopioidusedisorderbysite. Physiciancomfortwiththeactivitieslistedalongtheverticalaxisbysite.*Statisticalsignificancewith P-valueforcomparison(P < .05).

*Statisticallysignificant P-value < 0.05. Ref,referencegroup; OR,oddsratio.

andattitudestowardOUDtreatmentdidnotdiffer significantlybetweentheinterventionandcontrolsites.Our findingssuggestthatED-initiatedbuprenorphinecanbe facilitatedbyaddressingsystem-levelimplementation barriers,whileclinicianknowledge,comfort,andattitudes maybehardertoimproveandmayrequirelong-termand/or differentinterventions.

Thesystem-levelinterventionsdescribedwereaseriesof toolsandservicesintroducedtotheEDbyinterdisciplinary stakeholderstoencouragetheuseofevidence-based,EDinitiatedbuprenorphinethathadnotpreviouslybeen consideredstandardtreatmentforpatientslivingwithOUD. IntegratedEHRtemplatesandclinicalprotocolsand workflowsweretoolstosupportclinicaldecision-making, whilethepeernavigationprogramprovidedharmreduction interventionsandsupportedpost-dischargeplanningand linkagetocare.Theimplementationofthesesystem-level interventionswasintendedtominimizetheburdenon cliniciansandtoreducevariationincare.21 Theimpactofeach interventionwasnotmeasuredindividuallybecausemany componentswereintroducedandrefinedinanoverlapping, iterativemannerduringtheimplementationperiod.(For example,announcementsandeducationregardingtheEHR ordersetsandclinicalprotocolsoccurredatasimilartimeand acrosssubsequentmeetings.)Thecross-sectionalstudy capturedonlyclinicianoutcomesafterreceivingthewholeset ofsystem-levelinterventions,whichisalimitationof measuringreal-worldimplementationfacilitation. Implementationofthesesystem-leveltoolsandservices requiredinterventionsattheclinicianleveltointroduce, familiarize,andremindcliniciansofavailabletoolsand supportservices.Frequentreminders,educational opportunities, financialincentivesforthethen-required buprenorphineprescribingwaivercourseworkwerean attempttoencourageknowledgeofandcomfortwithEDinitiatedbuprenorphinewiththegoaltosupportachangein clinicalpracticeto treat OUD,notjustrespondtoacute

overdoses,intheED.Ourclinician-levelinterventionseased theimplementationofsystem-levelinterventionsinasimilar manner,asthebehavioralscience-based “nudges” wereused toincreasethenumberofphysicianswhoobtainedawaiver atanotherurban,academicED.22 Thesamegroupalsoused clinician-levelnudgesintheformofbestpracticeadvisories intheEHRandmonthlyemailstoincreasetheuseof ambulatoryreferralstoaBridgeClinicandbuprenorphine administration.15 Animportantpartoftheprocessappears toincludeaclinicalchampionwhocanworkwith stakeholderstoovercomeinstitutionalbarriers18,19,23 to refineworkflowsandprotocols,andwhocanalsobea contentexpertresourcetocolleaguestointroduceevidencebasedpracticeupdatesandreminders.

Inourstudy,physicians’ clinicaltimeandyearsinpractice hadanimpactonthelikelihoodofpracticingED-initiated buprenorphine.Clinicaltimeinpracticeisavariableusedto differentiatebetweenphysicianswithorwithoutdedicated timeforclinicaleducation,research,andadministration, whichwashypothesizedtohaveanindependenteffecton adoptionofemergingclinicalpractices.Yearsinindependent clinicalpracticeisusedasameasuretoaccountforsecular trendsinEMtraining;attendingphysicianswithfewerthan sevenyearsinclinicalpracticemayhavebeenexposedto frequentpressontheopioidepidemicandchanging guidelinesforOUDtreatmentintheED.Imetalreportthat junioremergencyphysiciansaremorelikelytoviewOUDas achronicdiseaseandapproveofbuprenorphineinitiationin theED,24 evenifjunioremergencyphysiciansexpresseda similarsenseoffrustrationtreatingpatientswithOUDas seniorphysicians.Ourstudydidnotincluderesident physicianstominimizecross-contaminationofexposureto interventions.Otherstudieshavefoundthatemergency physiciansintheirresidencytrainingareeagertoimplement ED-initiatedbuprenorphine.15,22 Attitudesamong emergencyphysiciansaregenerallychangingtowardOUD, anditisincreasinglybeingviewedasachronicdiseasewith

acutemanifestationsthatshouldbetreatedinthe EDsetting.24,25

Theremovalofthebuprenorphine-prescribingwaiver requirementisanacknowledgmentthatthisclinician-level barrierimpededaccesstotreatmentforOUD.26,27 Whilethis studywascompletedatatimewhenthebuprenorphineprescribingwaiverrequirementwasstillineffect(and justified financialincentivesforemergencyclinicianswho voluntarilyobtainedaprescribingwaiver),weexpectthat futureinterventionstoaddressclinician-levelbarriersto buprenorphineinitiationintheEDwillstillrequireaclinical championwhocanregularlyprovideupdatesabout implementationandleadeducationefforts.

Limitationstoourstudyincludearelativelysmallsample sizewitha58%responserate,whichmayhavecontributedto asamplingbias.Ourclinicalsitesareinanurbanareawitha highprevalenceofopioidoverdoseandOUD,whichmay influencephysicianinterestinandknowledgeofOUDand, thus,participationinthesurvey.ImplementationofEDinitiatedbuprenorphineattheinterventionsitereceived financialsupportanddepartmentalresourcesinatertiarycaremunicipalhospitalaswellasinitialgrantfundingfor salarysupportoftheclinicalchampion,whichmaylimit generalizabilitytoEDsettingsinsmaller,ruraland/orunderresourcedhospitals.Withoutpre-/post-evaluationsforeach intervention,wewereunabletoassesswhetheraparticular interventioninfluencedthedifferenceinbuprenorphine administrationattheinterventionsite.Buprenorphine experienceisself-reported;responsesregarding buprenorphineadministrationintheEDarenotlinkedto pharmacydatafromtheinterventionalorcontrolsites. Lastly,cross-contaminationofattendingphysicians’ exposurestointerventionsmayhaveoccurredviaresidents whorotateamongtheinterventionandcontrolsites.Itmay havealsooccurredatthegrandroundslectureswhereall facultyfromtheresidencysitesareinvited;however,total facultyattendancetypicallyhoveredbelow10%forthethen in-personlectures.

OurstudycomparestheadministrationofED-initiated buprenorphineattwosimilarandrelatedEDsettingswhere physiciansatonesitewereexposedtoamultifacetedsetof interventionstoED-initiatedbuprenorphine.Physicians exposedtointerventionsdesignedtoaddresssystem-and clinician-levelbarriersweremorelikelytoinitiate buprenorphineforOUDtreatmentintheirclinicalpractice. Futureimplementationeffortsshouldexamineinterventions thataretailoredtoimplementationbarriersevenafterthe buprenorphine-prescribingwaiverrequirementhasbeen eliminated,includingresidencyeducationtoimprovethe

understandinganduptakeofED-initiatedbuprenorphine. Couplingpharmacy-levelbuprenorphineadministrationand prescribingdatawithphysician-reportedoutcomeswillalso helpparseoutimpactoffutureinterventions.

AddressforCorrespondence:JacquelineMahal,MD,MBA,Jacobi MedicalCenter,DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine,1400Pelham ParkwaySouth,Bronx,NY10461.Email: mahalj@nychhc.org

ConflictsofInterest:Bythe WestJEMarticlesubmissionagreement, allauthorsarerequiredtodiscloseallaffiliations,fundingsources and financialormanagementrelationshipsthatcouldbeperceived aspotentialsourcesofbias.Noauthorhasprofessionalor financial relationshipswithanycompaniesthatarerelevanttothisstudy. Therearenoconflictsofinterestorsourcesoffundingtodeclare.

Copyright:©2024Mahaletal.Thisisanopenaccessarticle distributedinaccordancewiththetermsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY4.0)License.See: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/

1.AhmadFB,CisewskiJA,RossenLM,etal.Provisionaldrugoverdose deathcounts.NationalCenterforHealthStatistics.2023.Availableat: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm AccessedNovember20,2023.

2.Goldman-MellorS,OlfsonM,Lidon-MoyanoC,etal.Mortalityfollowing nonfatalopioidandsedative/hypnoticdrugoverdose. AmJPrevMed. 2020;59(1):59–67.

3.D’OnofrioG,O’ConnorPG,PantalonMV,etal.Emergencydepartmentinitiatedbuprenorphine/naloxonetreatmentforopioiddependence:A randomizedclinicaltrial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636–44.

4.KaucherKA,CarusoEH,SungarG,etal.Evaluationofan emergencydepartmentbuprenorphineinductionandmedicationassistedtreatmentreferralprogram. AmJEmergMed. 2020;38(2):300–4.

5.EdwardsFJ,WicelinskiR,GallagherN,etal.Treatingopioidwithdrawal withbuprenorphineinacommunityhospitalemergencydepartment:an outreachprogram. AnnEmergMed. 2020;75(1):49–56.

6.SubstanceAbuseandMentalHealthServicesAdministration (SAMHSA).UseofMedication-AssistedTreatmentinEmergency Departments.2021.Availableat: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/ default/files/pep21-pl-guide-5.pdf.AccessedAugust16,2023.

7.HawkK,HoppeJ,KetchamE,etal.Consensusrecommendationson thetreatmentofopioidusedisorderintheemergencydepartment. Ann EmergMed. 2021;78(3):434–42.

8.RheeTG,D’OnofrioG,FiellinDA.Trendsintheuseofbuprenorphinein USemergencydepartments,2002–2017. JAMANetwOpen. 2020;3(10):e2021209.

9.HawkKF,D’OnofrioG,ChawarskiMC,etal.Barriersandfacilitatorsto clinicianreadinesstoprovideemergencydepartment-initiated buprenorphine. JAMANetwOpen. 2020;3(5):e204561.

10.MendiolaCK,GalettoG,FingerhoodM.Anexplorationofemergency physicians’ attitudestowardpatientswithsubstanceusedisorder, J AddictMed. March/April2018;12(2):132–5.

11.LowensteinM,KilaruA,PerroneJ,etal.Barriersandfacilitatorsfor emergencydepartmentinitiationofbuprenorphine:aphysiciansurvey. AmJEmergMed. 2019;37(9):1787–90.

12.SavageTandRossM.BarriersandattitudesreportedbyCanadian emergencyphysiciansregardingtheinitiationofbuprenorphine/ naloxoneintheemergencydepartmentforpatientswithopioiduse disorder. CJEM. 2022;24(1):44–9.

13.LoganG,MirajkarA,HouckJ,etal.Physician-perceivedbarriersto treatingopioidusedisorderintheemergencydepartment. Cureus. 2021;13(11):e19923.

14.FosterSD,LeeK,EdwardsC,etal.Providingincentiveforemergency physicianX-waivertraining:anevaluationofprogramsuccessand postinterventionbuprenorphineprescribing. AnnEmergMed. 2020;76(2):206–214.

15.ButlerK,ChavezT,WakemanS,etal.Nudgingemergencydepartmentinitiatedaddictiontreatment. JAddictMed. 2022;16(4):e234–9.

16.KhatriU,LeeK,LinT,etal.Abriefeducationalinterventiontoincrease EDinitiationofbuprenorphineforopioidusedisorder(OUD). JMed Toxicol. 2022;18(3):205–13.

17.D’OnofrioG,EdelmanEJ,HawkKF,etal.Implementationfacilitationto promoteemergencydepartment-initiatedbuprenorphineforopioiduse disorder:protocolforahybridtypeIIIeffectiveness-implementation study(ProjectEDHEALTH). ImplementSci. 2019;14(1):48.

18.WhitesideLK,D’OnofrioG,FiellinDA,etal.Modelsforimplementing emergencydepartment-initiatedbuprenorphinewithreferralforongoing medicationtreatmentatemergencydepartmentdischargeindiverse academiccenters. AnnEmergMed. 2022;80(5):410–9.

19.D’OnofrioG,EdelmanEJ,HawkKF,etal.Implementationfacilitationto promoteemergencydepartment–initiatedbuprenorphineforopioiduse disorder. JAMANetwOpen.2023;6(4):e235439.

20.TuazonE,BaumanM,SunT,etal.UnintentionalDrugPoisoning (Overdose)DeathsinNewYorkCityin2022.NewYorkCityDepartment

ofHealthandMentalHygiene:EpiDataBrief(137);September2023. Availableat: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/ databrief137.pdf.AccessedFebruary13,2024.

21.CentersforMedicareandMedicaidServices.QualityMeasurementand QualityImprovement.2023.Availableat: https://www.cms.gov/ Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/ Quality-Measure-and-Quality-ImprovementAccessedNovember23,2023.

22.MartinA,KunzlerN,NakagawaJ,etal.Getwaivered:aresident-driven campaigntoaddresstheopioidoverdosecrisis. AnnEmergMed. 2019;74(5):691–6.

23.WoodK,GiannopoulosV,LouieE,etal.Theroleofclinicalchampionsin facilitatingtheuseofevidence-basedpracticeindrugandalcoholand mentalhealthsettings:asystematicreview. ImplementResandPract. 2020;1:2633489520959072.

24.ImDD,CharyA,CondellaAL,etal.Emergencydepartmentclinicians’ attitudestowardopioidusedisorderandemergencydepartmentinitiatedbuprenorphinetreatment:amixed-methodsstudy. WestJ EmergMed. 2020;21(2):261–71.

25.SokolR,TammaroE,KimJY,etal.LinkingMATTERS:barriersand facilitatorstoimplementingemergencydepartment-initiated buprenorphine-naloxoneinpatientswithopioidusedisorder andlinkagetolong-termcare. SubstUseMisuse. 2021;56(7):1045–53.

26.OfficeofNationalDrugControlPolicy(ONDCP).Dr.Guptaapplauds removalofX-waiverinomnibus,urgeshealthcareproviderstotreat addiction.2022.Availableat: https://www.whitehouse.gov/ondcp/ briefing-room/2022/12/30/dr-gupta-applauds-removal-of-xwaiver-in-omnibus-urges-healthcare-providers-to-treat-addiction AccessedFebruary23,2023.

27.USDepartmentofJustice,DrugEnforcementAdministration,Diversion ControlDivision.EliminationoftheDATAwaiverprogram.Availableat: https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/docs/dear_registrant_ AM_01122023.html.AccessedNovember20,2023.

EricaC.Koch,MD*†**

MichaelJ.Ward,MD,PhD,MBA*†§

AlvinD.Jeffery,PhD‡§∥

ThomasJ.Reese,PharmD§

ChadDorn,PSM§ ShannonPugh,RN* MelissaRubenstein,MPH*

JoEllenWilson,MD,MPH†¶ CoreyCampbell,DO#

JinH.Han,MD,MSc*†

*VanderbiltUniversityMedicalCenter,DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine, Nashville,Tennessee

† TennesseeValleyHealthcareSystem,GeriatricResearch,Education,andClinical Center,Nashville,Tennessee

‡ VanderbiltUniversitySchoolofNursing,Nashville,Tennessee

§ VanderbiltUniversityMedicalCenter,DepartmentofBiomedicalInformatics, Nashville,Tennessee

∥ TennesseeValleyHealthcareSystem,NursingServices,Nashville,Tennessee

¶ VanderbiltUniversityMedicalCenter,DepartmentofPsychiatry, Nashville,Tennessee

# TennesseeValleyHealthcareSystem,PsychiatricServices,Nashville,Tennessee

**VeteransAffairsQualityScholarsProgram,Nashville,Tennessee

SectionEditor:PhilipsPerera,MD

Submissionhistory:SubmittedMarch23,2023;RevisionreceivedNovember17,2023;AcceptedJanuary10,2024

ElectronicallypublishedApril9,2024

Fulltextavailablethroughopenaccessat http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem DOI: 10.5811/westjem.17996

Introduction: TheUnitedStatesVeteransHealthAdministrationisaleaderintheuseoftelementalhealth (TMH)toenhanceaccesstomentalhealthcareamidstanationwideshortageofmentalhealth professionals.TheTennesseeValleyVeteransAffairs(VA)HealthSystempilotedTMHinitsemergency department(ED)andurgentcareclinic(UCC)in2019, withfull24/7availabilitybeginningMarch1,2020. Followingimplementation,preliminarydatademonstratedthatveterans ≥65yearsoldwerelesslikelyto receiveTMHthanyoungerpatients.Wesoughttoexaminefactorsassociatedwitholderveteransreceiving TMHconsultationsinacute,unscheduled,outpatientsettingstoidentifylimitationsinthecurrentprocess.

Methods: ThiswasaretrospectivecohortstudyconductedwithintheTennesseeValleyVAHealth System.Weincludedveterans ≥55yearswhoreceivedamentalhealthconsultationintheEDorUCC fromApril1,2020–September30,2022.Telementalhealthwasadministeredbyamentalhealthclinician (attendingphysician,residentphysician,nursepractitioner,orphysicianassistant)viaiPad,whereasinpersonevaluationswereperformedintheED.Weexaminedtheinfluenceofpatientdemographics,visit timing,chiefcomplaint,andpsychiatrichistoryonTMH,usingmultivariablelogisticregression.

Results: Ofthe254patientsincludedinthisanalysis,177(69.7%)receivedTMH.Veteranswithhighriskchiefcomplaints(suicidalideation,homicidalideation,oragitation)werelesslikelytoreceiveTMH consultation(adjustedoddsratio[AOR]:0.47,95%confidenceinterval[CI]0.24–0.95).Comparedto attendingphysicians,nursepractitionersandphysicianassistantswereassociatedwithincreasedTMH use(AOR4.81,95%CI2.04–11.36),whereasconsultationbyresidentphysicianswasassociatedwith decreasedTMHuse(AOR0.04,95%CI0.00–0.59).TheUCCusedTMHforallbutoneencounter. Patientcharacteristicsincludingtheirvisittiming,gender,additionalmedicalcomplaints,comorbidity burden,andnumberofpsychoactivemedicationsdidnotinfluenceuseofTMH.

Conclusion: High-riskchiefcomplaints,location,andtypeofmentalhealthclinicianmaybekey determinantsoftelementalhealthuseinolderadults.Thismayhelpexpandmentalhealthcareaccessto areaswithashortageofmentalhealthprofessionalsandpreventpotentiallyavoidabletransfersinlowacuitysituations.FurtherstudiesandinterventionsmayoptimizeTMHforolderpatientstoensuresafe, equitablementalhealthcare.[WestJEmergMed.2024;25(3)312–319.]

In2020,52.9millionpeopleintheUnitedStates(US) sufferedfromamentalhealthorsubstanceusedisorder.1,2 Emergencydepartment(ED)visitsandadmissionsfor psychiatricconcernscontinuetoincrease.3–7 Despitethe increaseddemand,thereisawidespreadmentalhealth professionalsshortageintheUS,whichnegativelyaffects accesstotimely,efficientmentalhealthcareforsociety’smost vulnerablepopulations.Anestimated7,632cliniciansare neededtobridgethegapinlow-resourcedareas.8 Approximately66%ofruralorpartiallyruralcountiesare designatedbythefederalgovernmentasmentalhealth professionalshortageareas.8 Patientsintheseareashave beenfoundtohaveworsehealthoutcomes,includingshorter lifeexpectancyandhigherrateofsuicide.9–11 Innovative solutionsareneededtoaddressthesekeygapstoexpand accesstoequitablementalhealthservices,particularlyinthe settingofacutecrises.

Telehealthwas firstdescribedinclinicalpracticeinthelate 1950s.12 Overthepasttwodecades,usehasexpandedina varietyofclinicalsettings.13 TheVeteransHealth Administrationhasadoptedtelehealthacrossavarietyof settings,includingmentalhealthcomplaints.14 By2016, nearlyhalfofEDsintheUSreportedtheuseoftelehealth, with20%usingitformentalhealthpurposes(telemental health[TMH]).15,16 TheuseofTMHinroutineEDclinical practicegrewdramaticallyduringtheCOVID-19 pandemic.5 FormanyEDs,itistheonlyavenueto emergencypsychiatriccare.15

OnMarch1,2020,theTennesseeValleyVeteransAffairs HealthSystemimplementedfull-timeTMHforveteranswho presentedtotheEDformentalhealthcomplaints.Both TMHandin-personconsultationsperformedbyamental healthclinicianwereavailable7daysaweek,24hoursaday, includingholidays,attheEDandduringalloperatinghours attheUCC(daily8 AM – 8 PM).Consultationmodalitywas lefttothechoiceofthementalhealthclinician.In-person cliniciancoveragewasalwaysavailablebyanattending physician,residentphysician,nursepractitioner,or physicianassistantduringfacilityoperatinghours. Capabilitiesdidnotchangedependingontheroleofthe clinician.Amoredetaileddescriptionoftheprogramis providedelsewhere.17 Despitetheimplementationofthis TMHprogram,preliminarydatashowed20%ofmental healthconsultationsstilloccurredinperson.17 Veteranswho receivedin-personmentalhealthevaluationswerenotably oldercomparedtothosereceivingTMH,with31%in-person consultsoccurringinveteransages ≥65vs18%of TMHconsults.17

Olderpatientswithmentalhealthcomplaintsfaceunique challengesintheemergencysetting.Attentiontothese patientsduringtheimplementationofnewprocessesofcare isvitaltoensuretheyreceivehigh-qualitymentalhealth evaluation.Withtheexponentialgrowthprojectedforthe

PopulationHealthResearchCapsule

Whatdowealreadyknowaboutthisissue? Thereisawidespreadshortageofmental healthprofessionalsintheUS,which decreasesaccesstotimelyemergency mentalhealthcare.

Whatwastheresearchquestion?

Whatfactorsareassociatedwitholder veteransreceivingacute,unscheduled telementalhealth(TMH)vsinpersonconsults?

Whatwasthemajor findingofthestudy?

High-riskchiefcomplaints(suicidalor homicidalideation,oragitation)were associatedwithdecreasedTMHuse (OR0.39,95%CI0.18 – 0.81).Typeof clinicianandlocationofcarewerealso associatedwithTMHuse.

Howdoesthisimprovepopulationhealth?

TMHrepresentsanopportunitytoexpand accesstomentalhealthcare,therebyreducing potentiallyunnecessarypatienttransfersand shorteningboardingtimes .

olderpopulationintheUS,understandingfactorsassociated withvariabilityofTMHusewillinformfuture implementationandsustainabilityinacutecaresettings.18 In thisstudywesoughttoexaminefactorsassociatedwitholder veteransreceivingTMHconsultationsinacute,unscheduled, outpatientsettingstoidentifypotentialbarriersto widespreaduseofTMHintheED.Encountersinvolving patientsolderthan75,urbanlocation,residentphysicians, andhigheracuitywerehypothesizedtobemorelikelyto occurinperson.

StudyDesign,Setting,andPatientPopulation

Thiswasanexploratory,retrospective,cohortstudy conductedattheTennesseeValleyVAHealthSystemED andurgentcareclinic(UCC).20 Describedinmoredetail elsewhere,thisTMHprogramwasinitiallypilotedduring limitedhoursin2019andthenwentlivewith24/7coveragein March2020withtheonsetoftheCOVID-19pandemic.17 PatientswereinitiallyevaluatedbyanEDorUCCclinician (attendingphysician,residentphysician,nursepractitioner, orphysicianassistant)anddeterminedtoneedmentalhealth consultation.Aconsultorderwasthenrequestedthroughthe

electronichealthrecord(EHR)withdirectcommunication betweentheemergencyphysicianandon-callmentalhealth clinician(nursepractitioner,physicianassistant,orattending psychiatrist).Consultmodalitywaslefttothedecisionofthe on-callmentalhealthclinician.TheTMHvisitwasprovided viaAppleiPad(AppleInc,Cupertino,CA)withaudioand visualcapabilities,whereasin-personevaluationswere performedbythesamementalhealthclinicianintheEDor UCC.Bothin-personandTMHconsultationswereavailable 24/7intheEDandduringoperatinghours oftheUCC.

Weincludedveteranswhowere ≥55yearsandreceiveda mentalhealthconsultationintheEDbetweenApril1, 2020–September30,2022.Sincethereisnouniversally acceptedagethatdefines “olderage,” wechose55yearsold asthecut-offtomaximizeoursamplesizewhilemaintaining amedianageof65yearsold,atraditionalcut-point.Nonveteranswithoutservicebenefits,directadmissionswhodid notpresentthroughtheED,andpatientswithamissing modalityofconsultationwereexcluded.Forveteranswith multipleEDmentalhealthencounters,onlythe first consultationencounterwasincluded.Of1,478initialvisits withinthestudyperiod,weselected510chartstoreview;497 hadcompletementalhealthconsultationsinthechart.A substantialproportionofpatientsreceivedTMHduringthe studyperiod.Therefore,2–3TMHconsultationswere includedforeachin-personconsultation.Webalancedthe numberofchartsselectedforeachmonthofthestudyto reducetemporalbias.Wethenexcludedallpatients <55yearsfromthisanalysis.Thisstudywasapprovedbythe localinstitutionalreviewboardasexempt.

Wedesignedthechartreviewmethodologytofollow acceptedguidelines.21 Datawasmanuallyextractedfromthe VAEHRandClinicalDataWarehouse.Thefollowing patientfactorswereincludedinthisanalysis:age;race; gender;maritalstatus;rurality;EDtriagechiefcomplaint; mentalhealthhistory;totalactivenumberofpsychoactive medications;andpresenceofadditionalnon-psychiatric medicalcomplaint(eg,chestpain).Ruralitywasdetermined bytheRural-UrbanCommutingAreaCodesbasedonthe patient’sZIPcode.22 Weconsideredthefollowingsystemlevelfactors:location(EDvsUCC);timingofpresentation (9 AM – 5 PM ornights/weekends)andmentalhealthclinician type(nursepractitioner,physicianassistant,resident physician,orattendingphysician).

Patientdemographics,visitdate,homelessness, psychiatrichistory,andmedicationsweremanually abstractedbyaphysician(ECK)andnurse(SP).Senior authorstrainedabstractorspriortodatacollection.Each reviewerunderwentmentoredtrainingonhowtorevieweach chartwithatrialperiodofmanualdouble-checkingbythe seniorauthortoensurecompetency.Eachchartwas

reviewedbyeitherthephysicianornursereviewerandthen wascarefullydouble-checkedbythesamereviewerfor inaccuracies.Eachchartwasreviewedbyoneperson.Data abstractionformswereused,andthedatawascompiled usingREDCapelectronicdatacapturetoolshostedatUS DepartmentofVeteransAffairs.

Weusedthetotalnumberofpsychiatricconditions documentedintheEHRpriortotheindexEDvisitto determinepsychiatriccomorbidityburden.Anymentionof suicidalideation,homicidalideation,andagitationqualified ashigh-riskmentalhealthchiefcomplaints,regardlessof whetherthiswasthepatient’sprimaryreasonforED evaluation.Additionalmedicalreasonsforthe EDvisitwerecollectedbyreviewingtriageand physiciandocumentation.

Theprimarydependentvariableofinterestwasreceiptof TMHvsin-personmentalhealthconsultationbyamental healthclinicianwhowasanattendingphysician,resident physician,ornursepractitioner.

Wereportedcentraltendencyanddispersionasmedians andinterquartilerangesforcontinuousvariables. Categoricalvariableswerereportedasfrequenciesand percentages.Amultivariablelogisticregressionanalysiswas performedtodeterminefactorsassociatedwithuseofTMH. Wecreatedamoderatelysaturatedmodelwith7–8 covariatestominimizeoverfitting.23 Giventhesmallsample size,independentvariableswererankedaprioribasedon expertopinionfrompsychiatrists(EJW,CC)andemergency physicians(MJW,JHH)whoroutinelycareformental healthpatients.ThetopsevenrankedfactorsforTMHvsinpersonmentalhealthevaluationincludedage,race,high-risk chiefcomplaint,presenceofdementia,urbanlocation, timingofpresentation,andhistoryofsubstanceabuse.To exploreadditionalfactorsassociatedwithTMHvsin-person mentalhealthconsultation,weperformedahighlysaturated modelincorporatingallfactorsintothemultivariablelogistic regressionmodel.Becausesite(EDvsUCC)ofpatient presentationmayhavestronglyinfluencedTMHvsinpersonmentalhealth,thisfactorwasincorporatedintothe models.Adjustedoddsratios(aOR)with95%confidence intervals(CI)arereported.Weconductedallstatistical analyseswithRstatisticalsoftware,v3.6.2(TheRProjectfor StatisticalComputing,Vienna,Austria).

Ofthe510healthrecordsreviewed,254patientsmetage inclusioncriteria(≥55yearsofage)andwereincludedinthe study.Characteristicsofthisoldercohortvstheentirecohort ofchartsreviewedisincludedasasupplementaltable. Ofthoseeligible,177(69.7%)veteransreceivedTMH

Table1. Baselinedemographicdataofpatientspresenting totheemergencydepartmentorurgentcarecenterreceiving psychiatricconsultation.

Variable In-person (n = 77) Telemental health(n = 177)

Age,(years)65[61,71]65[61,70]

Gender,n(%)

Female3(3.9)14(7.9)

Male74(96.1)163(92.1)

Race,n(%)

Black30(39.0)72(40.7)

Non-Black47(61.0)105(59.3)

Maritalstatus,n(%)

Married26(33.8)44(24.9)

Unmarried/unknown51(66.2)133(75.1)

Chiefcomplaintrisk,n(%)

Low49(63.6)130(73.4)

High28(36.4)47(26.6)

Historyofdementia,n(%)

Yes10(13.0)18(10.2)

No67(87.0)159(89.8)

Location,n(%)

ED76(98.7)151(85.3)

UCC1(1.3)26(14.7)

Rural,n(%)

Rural24(31.2)45(25.4)

Urban53(68.8)132(74.6)

ESIscore ≥ 2,n(%)77(100.0)177(100.0)

ESIscore,n(%)

<322(28.6)61(34.5)

≥355(71.4)116(65.5)

Timingofpresentation, n(%)

Offhours28(36.4)64(36.2)

Businesshours49(63.6)113(63.8)

Historyofsubstance abuse,n(%)

No36(46.8)74(41.8)

Yes41(53.2)103(58.2)

Mentalhealthclinician type,n(%)

Attendingphysician62(80.5)123(69.5)

Residentphysician7(9.1)1(0.6)

Nursepractitioneror physicianassistant 8(10.4)53(29.9)

Totalpsychoactive medications, median[IQR]

(Continuedonnextcolumn)

Table1. Continued. Variable In-person (n = 77)

Telemental health(n = 177)

Totalpsychiatric comorbidities,median [IQR] 1.00[1.00,2.00]2.00[1.00,2.00]

Additionaltriagemedical complaint,n(%)

No48(62.3)118(66.7)

Yes29(37.7)59(33.3)

Homelessness,n(%)

No64(83.1)144(81.4)

Yes13(16.9)33(18.6)

CCIscore,median[IQR]2.00[1.00,4.00]2.00[1.00,5.00]

ESI,EmergencySeverityIndex; IQR,interquartilerange; CCI, CharlsonComorbidityIndex; UCC,urgentcareclinic; ED, emergencydepartment.

consultations,and77(30.3%)veteransreceivedanin-person evaluation.Therewerenomissingdatapointsonchart review.Intheunadjustedresults,UCClocationand consultationperformedbynursepractitionersandphysician assistantswasassociatedwithastatisticallysignificanttrend towardsTMHuse(Table1).Consultationsperformedby residentmentalhealthphysiciansweremorelikelytooccurin personbutrepresentedfewconsultsoverall(Table1). Age,race,presenceofdementiaorsubstanceusedisorder inmedicalhistory,totalpsychoactivemedications, psychiatriccomorbidityburden,homelessness,andmarital statuswerenotassociatedwithsignificantdifferencesin consultmodality.

Wethenperformedmultivariablelogisticregression analysis.Modelswereadjustedforlocationtoaccountfor sitepracticedifferencesattheEDandUCC,astheUCC performednearlyallconsultsviaTMH. Table2 demonstratesamoderatelysaturatedriskmodel.Nofactors weresignificantlyassociatedwithTMHusebeyondurgent carelocation(AOR15.15,95%CI1.98–116.04).Inahighly saturatedmodel,patientsevaluatedbyresidentphysicians werelesslikelytoreceiveTMH(AOR0.04,95%CI: 0.00–0.58),whilethoseevaluatedbynursepractitionersand physicianassistantsreceiveditmorefrequently(A5.07,95% CI:2.13–12.03),comparedtoattendingphysicians(Table3). Patientswithhigh-riskchiefcomplaints(suicidalideation, homicidalideation,oragitation)werelesslikelytoreceive TMH(AOR:0.39,95%CI:0.18–0.81)inthehighlysaturated riskmodel(Table3).Gender,age,race,comorbidityburden, timingofpresentation,historyofsubstanceusedisorder, historyofdementia,andhomelessnesswerenotassociated significantdifferencesinconsultmodality.

Table3. Multivariableregressionanalysis – highlysaturatedmodel.

modality.Specifically,weobservedthatpatientswithhighriskpsychiatricchiefcomplaints(suicidalideation, homicidalideation,andagitation)weremorelikelytoreceive in-personconsultations.Residentphysiciansperforming consultswerelesslikelytouseTMH,whilenurse practitionersandphysicianassistantsweremorelikelyto chooseTMH.TheUCCusedTMHnearuniversally.

Themoderatelysaturatedriskmodelofmosthighly rankedapriorifactorsshowedAORsgreaterthan1inurban location,timingofpresentationduringoffhours,andhistory ofsubstanceusedisorder.However,the95%CIweretoo widetobesignificant.These findingsweresimilarinthe highlysaturatedmodel.Whilenotstatisticallysignificant, thesefactorsmayholdclinicalrelevance.Further studieswithahighersamplesizeareneededtoclarify anysignificance.

–2.26

–12.03

–0.58

–1.32

–1.54

–1.40 Homelessness1.130.47–2.71

–1.23

UCC,urgentcareclinic; CCI,CharlsonComorbidityIndex.

DISCUSSION

InanoldercohortofveteranspresentingtotheEDor UCCwithacutepsychiatriccomplaints,wefoundthathighriskpsychiatricchiefcomplaints,cliniciantype,andlocation ofthementalhealthconsultwerekeydriversofconsultation

Onepotentialexplanationforreduceduseamonghigher severitycomplaintsisthatmentalhealthcliniciansmayfeel morecompelledtoconductin-personconsultationinhigher acuitysituationsbecausethisiswhattheyaremostfamiliar with.PracticechangessuchastheuseofTMHmaycreatea disruptionasphysiciansstruggleto “unlearn” whattheyare mostfamiliarwithpriortoestablishinganewpractice pattern.24 Alternatively,asrecognizedbytheSocietyfor AcademicEmergencyMedicineConsensusConferenceon EmergencyTelehealth,littleresearchhasbeendoneonthe qualityandsafetyoftelehealth.25 Recentworkhassoughtto addressthis.Evidencesuggestspatientspresentingwithacute psychosismaytoleratetelehealthwell.26,27 Telementalhealth hasbeenfoundtohavenodifferenceinlong-termoutcomes ofrehospitalizationanddeathinpatientswithsuicidal ideationandsuicideattemptscomparedtoin-person consultation.26,28 Additionally,recentworkhassuggested thatTMHisnotassociatedwithincreased30-dayreturn visits,readmissions,ordeathcomparedtoin-person evaluationsinacutecaresettings.26 Therefore,EDand mentalhealthcliniciansshouldbeeducatedonthesafetyof TMHinolderEDpatientswithhigh-riskmentalhealth chiefcomplaints.

Priorresearchdemonstratedthatclinicianscontribute substantialvariabilitytothedecisiontousetelehealthand maypartiallyexplainwhytherearesuchdifferencesinthe useofTMHbycliniciantype(ie,residentphysiciansvsnurse practitionersandphysicianassistants).29 Therewereno differencesinclinicianschedulingthatcouldaccountforthe findingsinourstudy.Allmentalhealthclinicians,including residents,wereavailabletoperformin-personorTMH evaluations.Therefore,locationdidnotmakeresidentsmore orlesslikelytoevaluatepatientsinperson.Thepandemic demonstratedvariabilityintelehealthusewithclinician factorshavingagreaterinfluenceontheuseofvideo telehealthwhencomparedwithpatientfactors.29 Moreover, priorstudiesindicatetherearevariabilitiesinpatientswho areofferedtelehealthdespitebeingvideo-capable.30 Prior

qualitativestudiessuggestthatincreasedexposureto telehealthimprovedclinicianattitudes,whileperceptionsof complexitywithintheprocessledtoreducedutilization.31 Furtherresearchisneededtobetterunderstandwhether inequitiesandanycontributingfactorsexist.

Systemswithunanimousleadershipbuy-inandpolicies usetelehealthmorefrequently.31 Despitetheavailabilityof anin-personmentalhealthclinician,theUCCusedTMHfor nearlyeveryencounter.Itisplausiblethatsimilarsystemic factorsmaybecontributingtothisphenomenon. Investigatingthepoliciesanddecision-makingprocesses throughqualitativestudiescouldshedlightontheunderlying reasonsforthenear-universaluseofTMHattheUCC,as factorsnotcapturedinthisstudyarelikelyinvolved.

ReluctancetoadoptTMHmaycontributetopotentially avoidabletransfersinEDswithlimitedmentalhealth resources.Priorresearchfoundthatmentalhealthpatients werethemostlikelytobetransferredfromVAEDsand representthelargestgroupofpotentiallyavoidabletransfers, definedasthosetransfersrapidlydischargedfromtheEDor within24hoursfromhospitaladmission(withouta procedure).32 Our findingssuggestthatmentalhealth cliniciansfeltcomfortableevaluatingpatientsviaTMHin low-acuitysituations.Inplaceswithoutaccesstoin-person mentalhealthconsultation,patientswithloweracuity complaintsmaybeevaluatedandsafelydischargedvia TMH,reducingtheriskofunnecessarytransfer.33

WeidentifiedonlyoneresidentTMHencounter throughouttheentirestudyperiod.Asresidentsgenerally rotatebetweenmultipleVAandnon-VAclinicalservices, this findingmaybeduetolackoffamiliaritywiththeprocess inthissystem.Duetothelowoverallnumberof consultationsperformedbyresidents,itisdifficulttodraw conclusionsregardingthisdata.Educationalinitiatives targetingtelehealthuseamongresidentphysiciansmay increasefamiliaritywithTMH.34,35 Astelehealth expandedacrossmultiplespecialtiesduringthepandemic, medicaltrainingcurriculacouldbeadaptedtoinclude telehealthinitiatives.34,35

Limitationsofthisstudyincludedasmallsamplesize.Our samplesizemayhavebeentoosmalltoidentifyriskfactors forTMHuse.Additionally,becausethisstudywas conductedinasinglecenteritmaynotbegeneralizableto othersettings.Riskfactorsidentifiedinourexploratory analysisandthesignificantassociationsobservedmayhave beensecondarytooverfittingasstatisticalsignificancewas onlynotedinthehighlysaturatedmodel.Asaresult,these findingsshouldbeconfirmedinalargersamplesize. Additionally,theVAhasalowproportionofwomen veterans(estimated11.5%),potentiallylimitingthe generalizabilityofourstudyoutsidetheVApopulation.36 FurtherstudiesoutsidetheVApopulationareneededto

assessforanygender-specificdifferencesthatmayimpact consultmodalitychoice.

TheED/UCCclinicianandmentalhealthclinician generallyhadaverbalconversationoncallpriortomental healthconsultation.Theseconversationsmayhave influencedmodalitychoicebythementalhealthclinician. Ourquantitativedatawouldnothavebeenabletocapture theseconversations.Furtherqualitativeworkmaybridge thisgaptounderstandaclinician’smodalitychoice.

Therearepotentialconfounderstothisstudythatwerenot accountedfor.Severityofillnesslikelyaffectsboththe likelihoodofacutecarepresentationandtheconsult modalitychoice.Whileweadjustedforhigh-riskpsychiatric complaintstoaccountforseverityofillness,residual confoundinglikelystillexists.Encountersthatoccurred duringtheCOVID-19pandemicalsolikelyinfluencedboth thelikelihoodofacutecarepresentationandtheconsult modalitychoice.Morementalhealthcliniciansmayhave optedforTMHtoreducetheriskofvirustransmission, especiallyduringperiodsofwidespreadCOVID-19 transmission.Patientsmayhavealsobeenmorefearfulof presentingtotheEDforcareduringthesetimes.Ongoing post-pandemicdataanalysisbothatthisfacilityand externallyshouldbeperformedtoevaluatetheeffectsofthe COVID-19pandemiconTMHuse.

Inthisexploratoryretrospectiveanalysis,illnessseverity, location,andcliniciancharacteristicsappearedtoinfluence useoftelementalhealthinpatientsoverage55.Loweracuity, olderpatientsrepresentapatientpopulationwithwhom moreclinicianswouldbecomfortableusingTMH.For resource-poorsettings,TMHmayrepresentanopportunity toexpandaccesstomentalhealthcareinshortageareasand reducepotentiallyunnecessarypatienttransfersthatcould otherwisebepreventedviaremoteconsultation.Further researchisneededtoexaminehesitancytoadoptTMHin moreacutelyillpopulationsandthegeneralizabilityofthe findingspresentedinthiswork.

AddressforCorrespondence:JinH.Han,MD,MSc,Vanderbilt UniversityMedicalCenter,DepartmentofEmergencyMedicine, 2215GarlandAvenue,LightHallSuite203,Nashville,TN37232. Email: jin.h.han@vumc.org

ConflictsofInterest:Bythe WestJEMarticlesubmissionagreement, allauthorsarerequiredtodiscloseallaffiliations,fundingsources and financialormanagementrelationshipsthatcouldbeperceived aspotentialsourcesofbias.Thismaterialisbaseduponwork supported(orsupportedinpart)bytheDepartmentofVeterans Affairs,VeteransHealthAdministration,OfficeofRuralHealth, VeteransRuralHealthResourceCenter–IowaCity(Award#ORH10808).AlvinD.Jefferyreceivedsupportforthisworkfromthe AgencyforHealthcareResearchandQuality(AHRQ)andthe

Patient-CenteredOutcomesResearchInstitute(PCORI)under AwardNumberK12HS026395.Thecontentissolelythe responsibilityoftheauthorsanddoesnotnecessarilyrepresentthe officialviewsofAHRQ,PCORI,ortheUnitedStatesgovernment. Therearenootherconflictsofinterestorsourcesoffunding todeclare.

Copyright:©2024Kochetal.Thisisanopenaccessarticle distributedinaccordancewiththetermsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY4.0)License.See: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/

1.SubstanceAbuseandMentalHealthServicesAdministration.Key substanceuseandmentalhealthindicatorsintheUnitedStates:Results fromthe2020NationalSurveyonDrugUseandHealth.2021.Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/ NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121. pdf.AccessedMarch22,2023.

2.OwensP,FingarK,McDermottK,etal.InpatientStaysInvolvingMental andSubstanceUseDisorders,2016.HealthcareCostandUtilization Project(HCUP)StatisticalBriefs.2019.Availableat: https://hcup-us. ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb249-Mental-Substance-Use-DisorderHospital-Stays-2016.jsp.AccessedMarch22,2023.

3.BallouS,MitsuhashiS,SankinLS,etal.Emergencydepartmentvisits fordepressionintheUnitedStatesfrom2006to2014. GenHosp Psychiatry. 2019;59:14–9.

4.TheriaultKM,RosenheckRA,RheeTG.Increasingemergency departmentvisitsformentalhealthconditionsintheUnitedStates. JClin Psychiatry. 2020;81(5):20m13241.

5.ZhuD,PaigeSR,SloneH,etal.Exploringtelementalhealthpractice before,during,andaftertheCOVID-19pandemic. JTelemedTelecare. 2024:30(1):72–8.