VIETNAM IN TRANSITION, 1976-PRESENT

APRIL 1-OCTOBER 22, 2023

WENDE MUSEUM

Vietnam in Transition, 1976–Present is curated by Joes Segal and Emma Diffley, with support from Anna Atkeson. The exhibition is generously supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and is dedicated to the late Stephen O. Lesser (1931–2021).

Catalogue design by Ananya Madiraju.

Vietnam in Transition, 1976–Present explores the multilayered intersections of art, history, and memory in Vietnam since the end of the Vietnam War and national reunification. With its history of French colonialism, American imperialism and war, Soviet-style socialism, and relative economic liberalization since the 1986 Doi Moi policy, Vietnam is a country of contrasts and strong divisions, both internally and between the homeland and the international diaspora.

Through the lens of contemporary art and artifacts, Vietnam in Transition, 1976–Present highlights a variety of topics, including dealing with a traumatic past, sites of remembrance, political suppression, tensions between tradition and modernity, refugees and refugee camps, and the diasporic experience between nostalgia and adaptation.

The exhibition presents Vietnamese artists who fled or immigrated to the United States, artists who returned to their homeland, and artists who never left Vietnam. While many of the artists touch on complex ideas and associations, their works on view can be divided in four main approaches. Dinh Thi Tham Poong, Nguyen Quang Huy, Nguyễn Thế Sơn, Nguyen Van Cuong, and Võ Trân Châu reflect on elements of tradition versus modernization in present-day Vietnam. Binh Danh, Dinh Q. Lê, and Tuan Andrew Nguyen evoke memories and representations of war in the East and the West. Hoang Duong Cam, Ngô Đình Bảo Châu, and Phan Quang focus on the complex interplay between history and memory in dealing with the Vietnamese past. And Ann Le, Antonius-Tín Bui, Binh Danh, and Phung Huynh address aspects of the Vietnamese diaspora, including the traumatic experience of fleeing and refugee camps, as well as the complexities of mixed identities associated with the country of birth and the country of destination. The exhibition also presents contextual materials, including refugee drawings from the Art in the Camps (Garden Streams) Archive of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library’s Special Collections, photographs by Les Bird of Vietnamese boat refugees in and around Hong Kong, and the documentary The Next Generation by Sandy Northrop about transformations in the lives of young Vietnamese in the 2000s.

Vietnam in Transition, 1976–Present is curated by Joes Segal and Emma Diffley, with support from Anna Atkeson. Special thanks to Emma Balda, Shoshana Blank, Tommy Vinh Bui, James Cohan, Vinny Dotolo, Jane Friedman, Judith Hughes Day and John Day, Burhan Gafoor, Leung Harry, Suzanne Im, Luis De Jesus, Jamie Kwan, Việt Lê, Evelyna Liang, Monique Meloche, Quynh Pham, Vicki Phung Smith, Chau Thuy, Nora Annesley Taylor, Jennifer Vanderpool, Madame Zarina Varukatty, Linda Trinh Võ, Nancy Zastudil, and the participating artists.

1

INTRODUCTION

Ann Le, PHOXSCAPE, 2020

The Vietnamese diaspora has established communities in every corner of the world. Since the reopening of the country in the early 1990s, many of those who left their home country have made the return journey. Others shrink back from the confrontation between their memories and the present reality of their country, or are afraid to reawaken carefully buried memories. As a child of refugee immigrants, Le’s livelihood and that of her family was built upon Pho restaurants. Saigon Blue and Café Plus Purple are reimagined environments of old-world landscapes of the Vietnamese rừng (jungle) and contemporary urbanscape of Pho restaurants of Los Angeles. These stacked images transform moments and environments into a reimagined landscape, merging here and there, past and present.

ARTISTS 2

Sponsored by Nikon.

Ann Le, Saigon Blue, PHOXSCAPE, 2020, photomontage Courtesy of the artist

3

Ann Le, Café Plus Purple, PHOXSCAPE, 2020, photomontage Courtesy of the artist

Antonius-Tín Bui

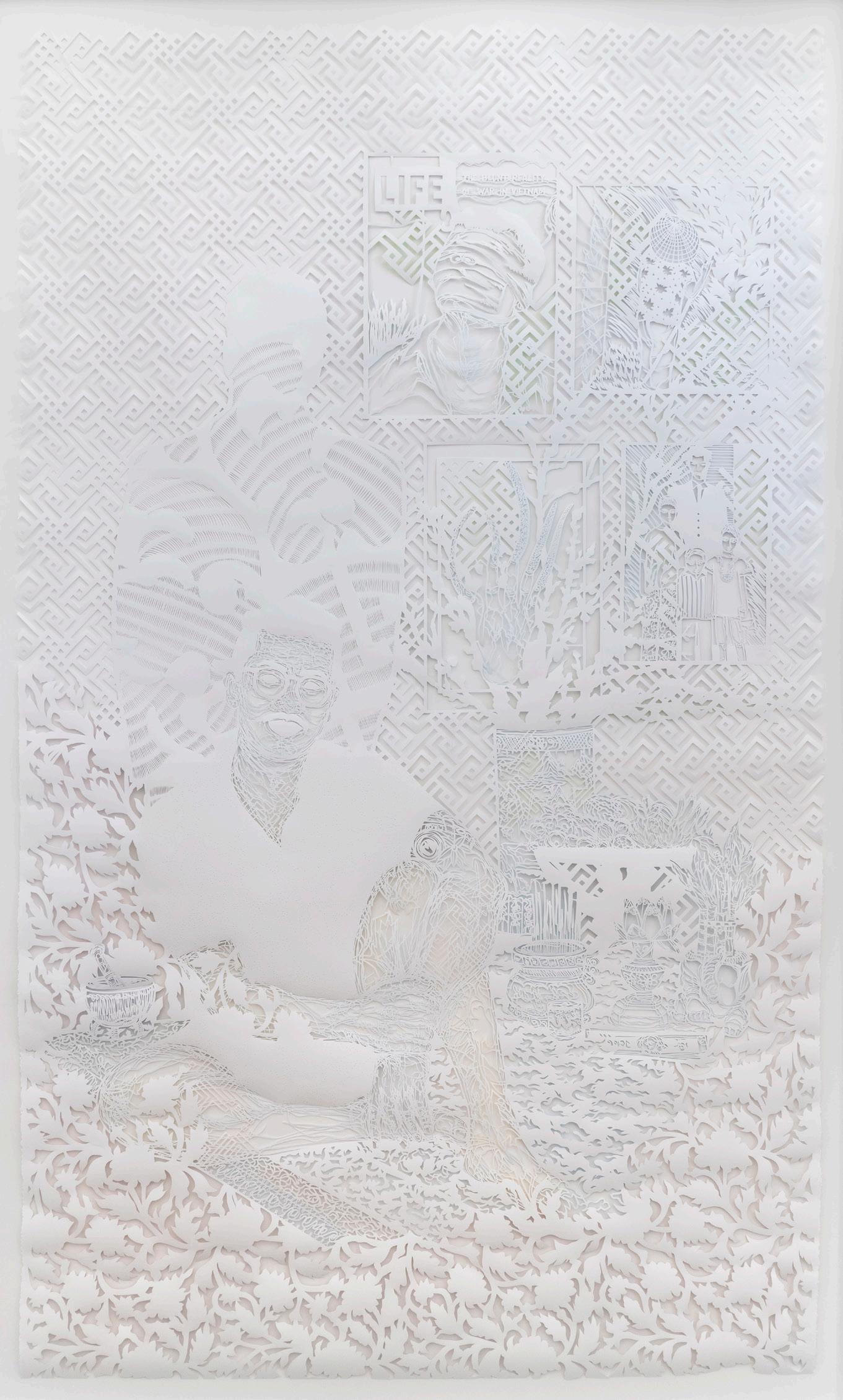

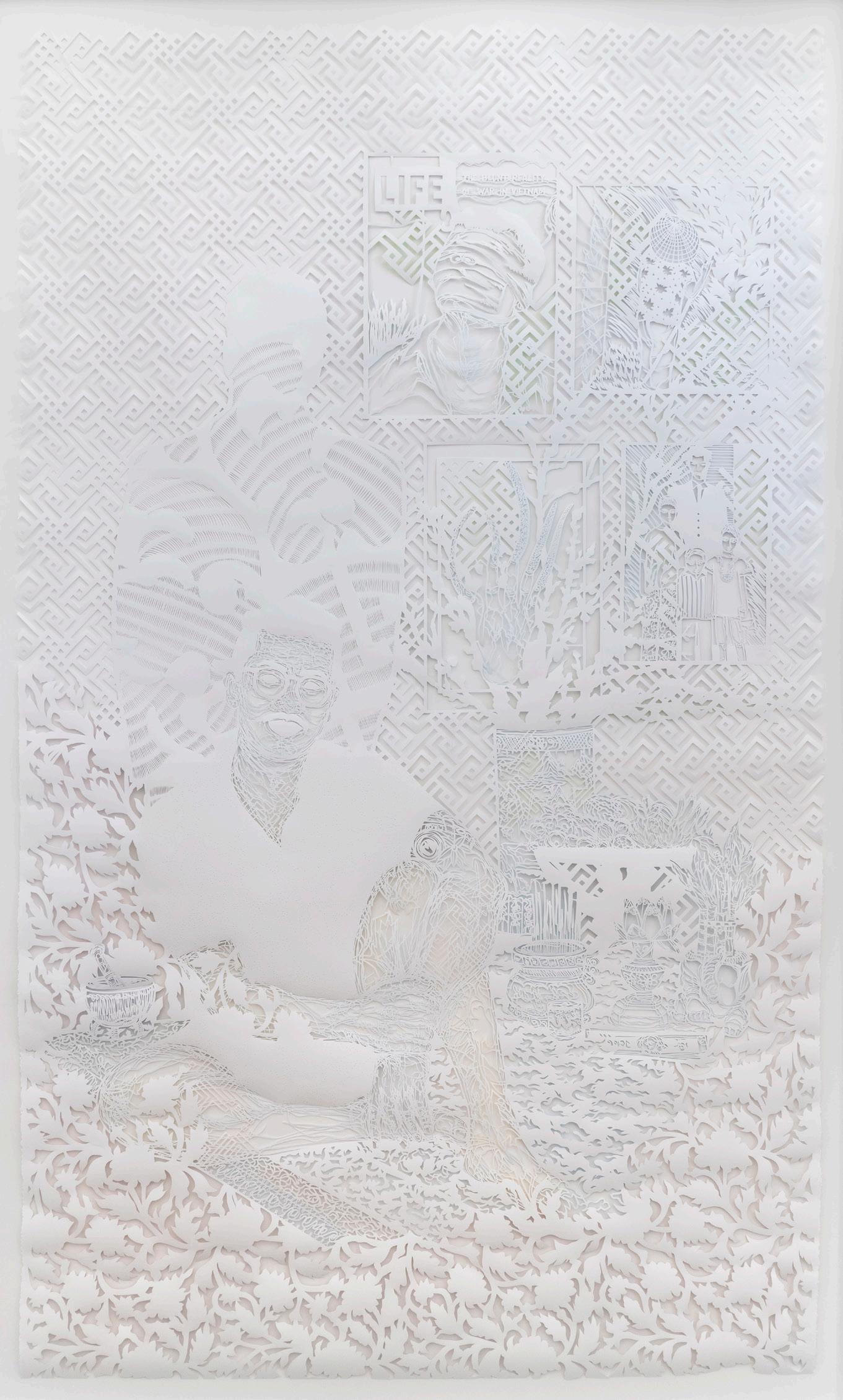

Antonius-Tín Bui, Finding Himself in an Impossible Direction, A Future Outside the Photograph, 2021, ink, pencil, and paint on hand-cut paper Courtesy of the artist, Vinny Dotolo, and Monique Meloche Gallery

Antonius-Tín Bui’s artwork reflects on the kinship shared within the queer Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. Their larger-than-life-size, hand-cut paper portraits consider the archival documentation used to reconcile formerly lost Asian American and Pacific Islander narratives, while also drawing from practices across Vietnamese culture. This work juxtaposes the portrait of Bui’s friend Brandon Tho Harris with a silhouette of Harris’s deceased father, wearing an áo dài, a traditional Vietnamese long-sleeve garment. The Life Magazine cover shows a Vietnamese soldier bound and about to be executed. Bui cuts their work out of white Joss paper (incense paper), a color symbolizing death in Vietnamese culture. The rigorous and reductive paper-cutting process deconstructs the traditional white canvas in order to both metaphorically and physically carve out space for narratives that are so often omitted from whitewashed histories. “When working on my hand-cut paper portraits, I compare each slice to a line break within a poem, an opportunity to breathe into the next idea. Together every inhale and exhale materializes into a body of textual flesh, one that can be read in infinite ways.”

—Antonius-Tín Bui

4

Detail: Antonius-Tín Bui, Finding Himself in an Impossible Direction, A Future Outside the Photograph, 2021, ink, pencil, and paint on hand-cut paper Courtesy of the artist, Vinny Dotolo, and Monique Meloche Gallery

Details: Antonius-Tín Bui, Finding Himself in an Impossible Direction, A Future Outside the Photograph, 2021, ink, pencil, and paint on hand-cut paper Courtesy of the artist, Vinny Dotolo, and Monique Meloche Gallery

5

Details: Antonius-Tín Bui, Finding Himself in an Impossible Direction, A Future Outside the Photograph, 2021, ink, pencil, and paint on hand-cut paper Courtesy of the artist, Vinny Dotolo, and Monique Meloche Gallery

Details: Antonius-Tín Bui, Finding Himself in an Impossible Direction, A Future Outside the Photograph, 2021, ink, pencil, and paint on hand-cut paper Courtesy of the artist, Vinny Dotolo, and Monique Meloche Gallery

6

Details: Antonius-Tín Bui, Finding Himself in an Impossible Direction, A Future Outside the Photograph, 2021, ink, pencil, and paint on hand-cut paper Courtesy of the artist, Vinny Dotolo, and Monique Meloche Gallery

7

Detail: Antonius-Tín Bui, Finding Himself in an Impossible Direction, A Future Outside the Photograph, 2021, ink, pencil, and paint on hand-cut paper Courtesy of the artist, Vinny Dotolo, and Monique Meloche Gallery

8

Binh Danh

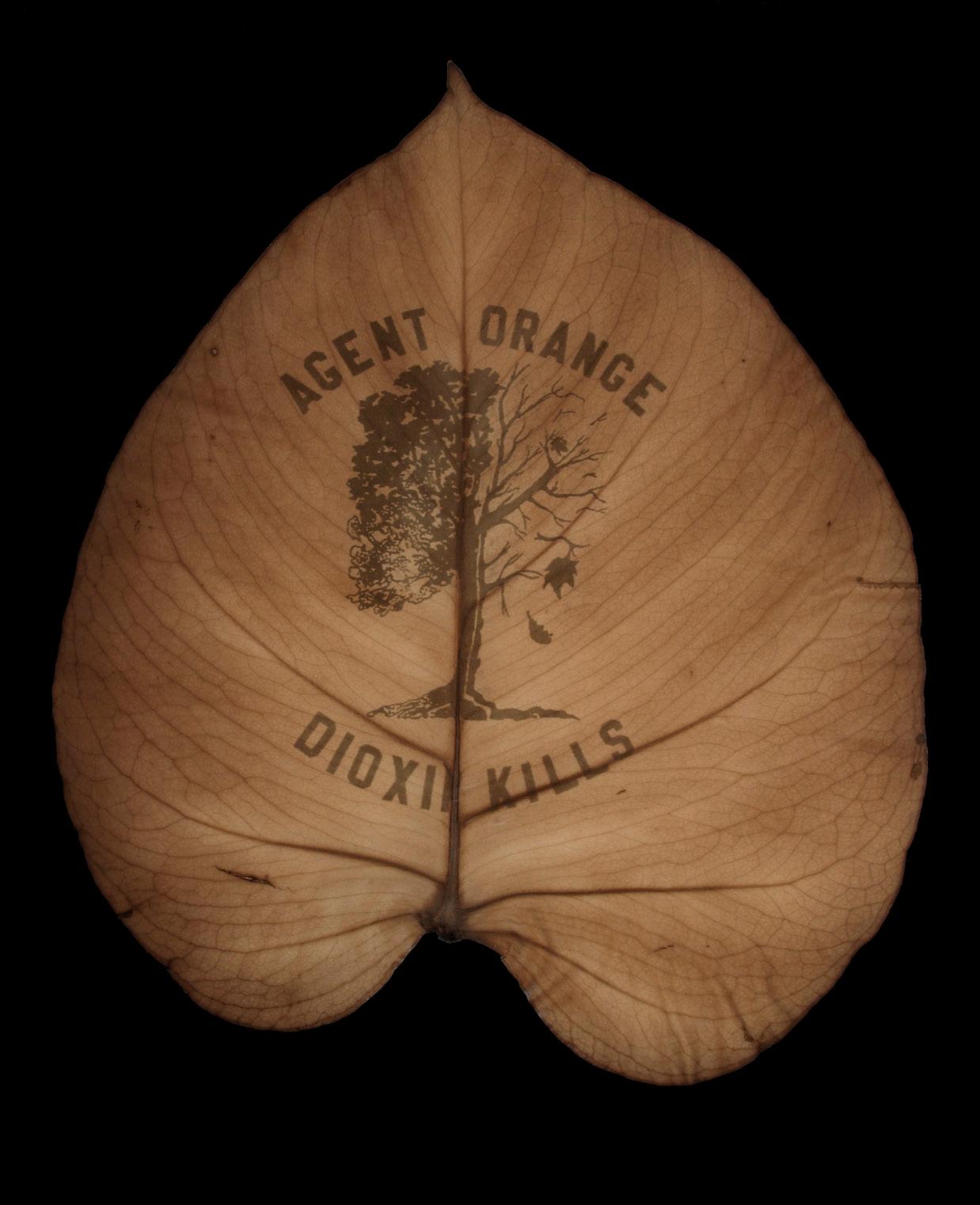

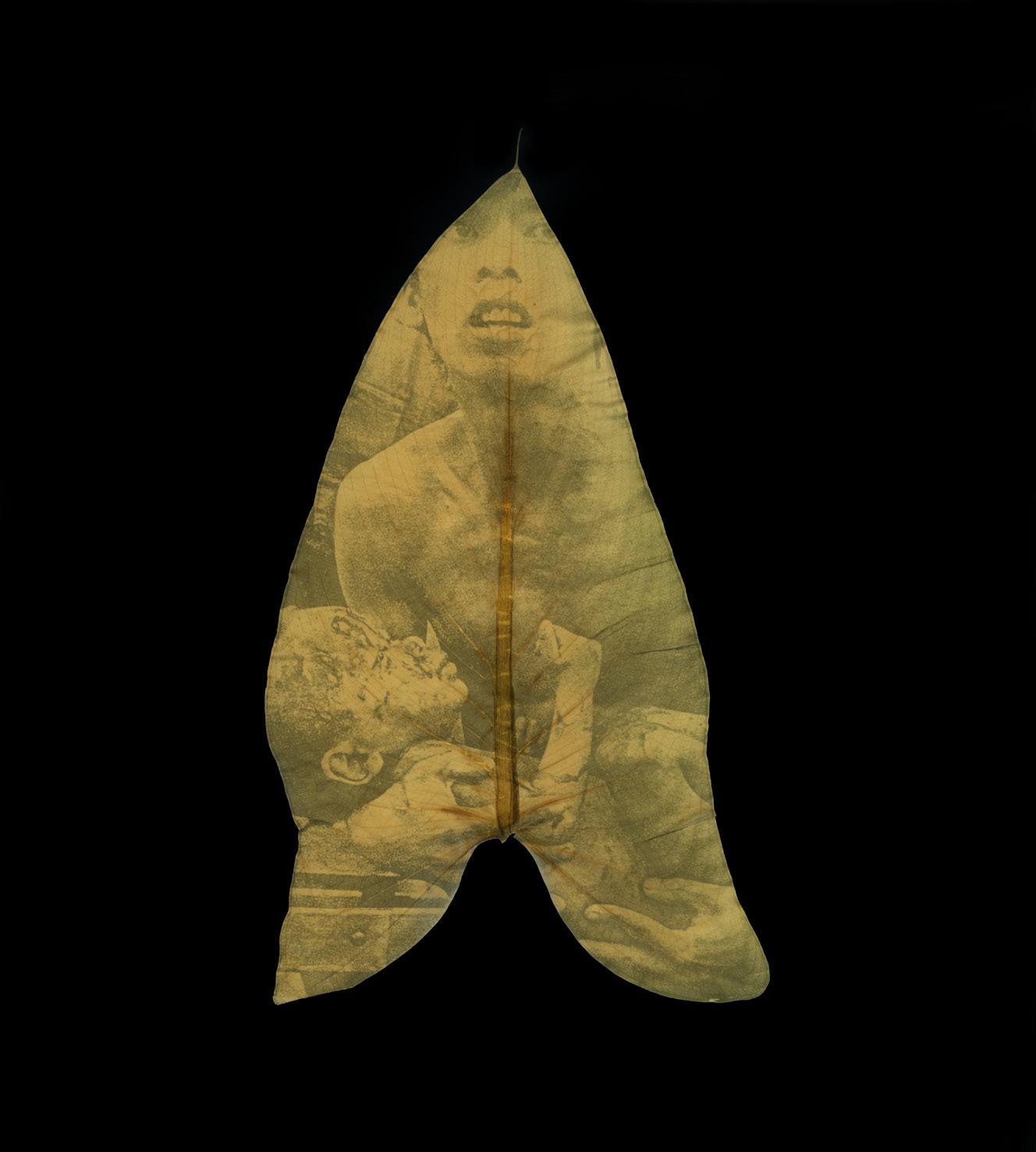

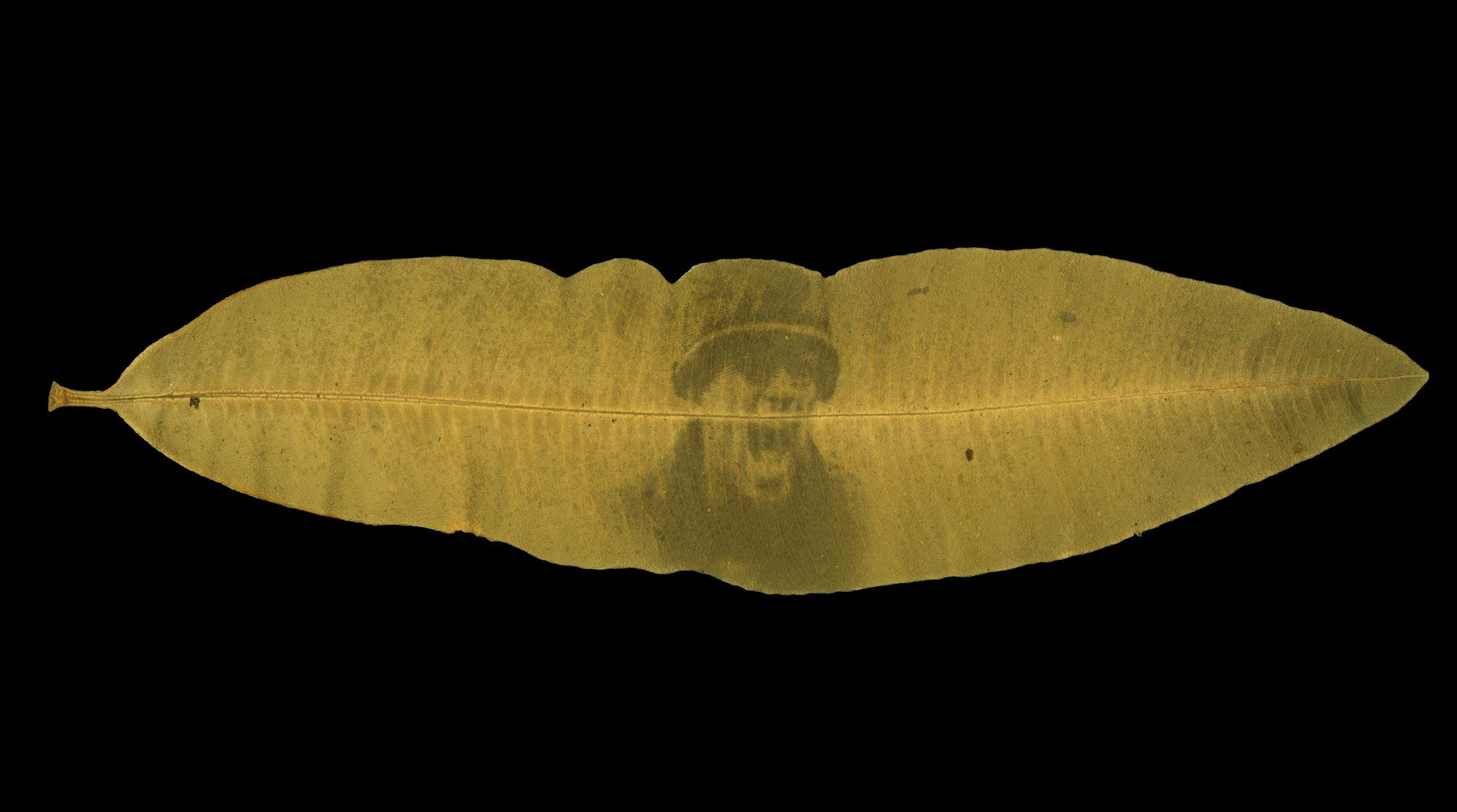

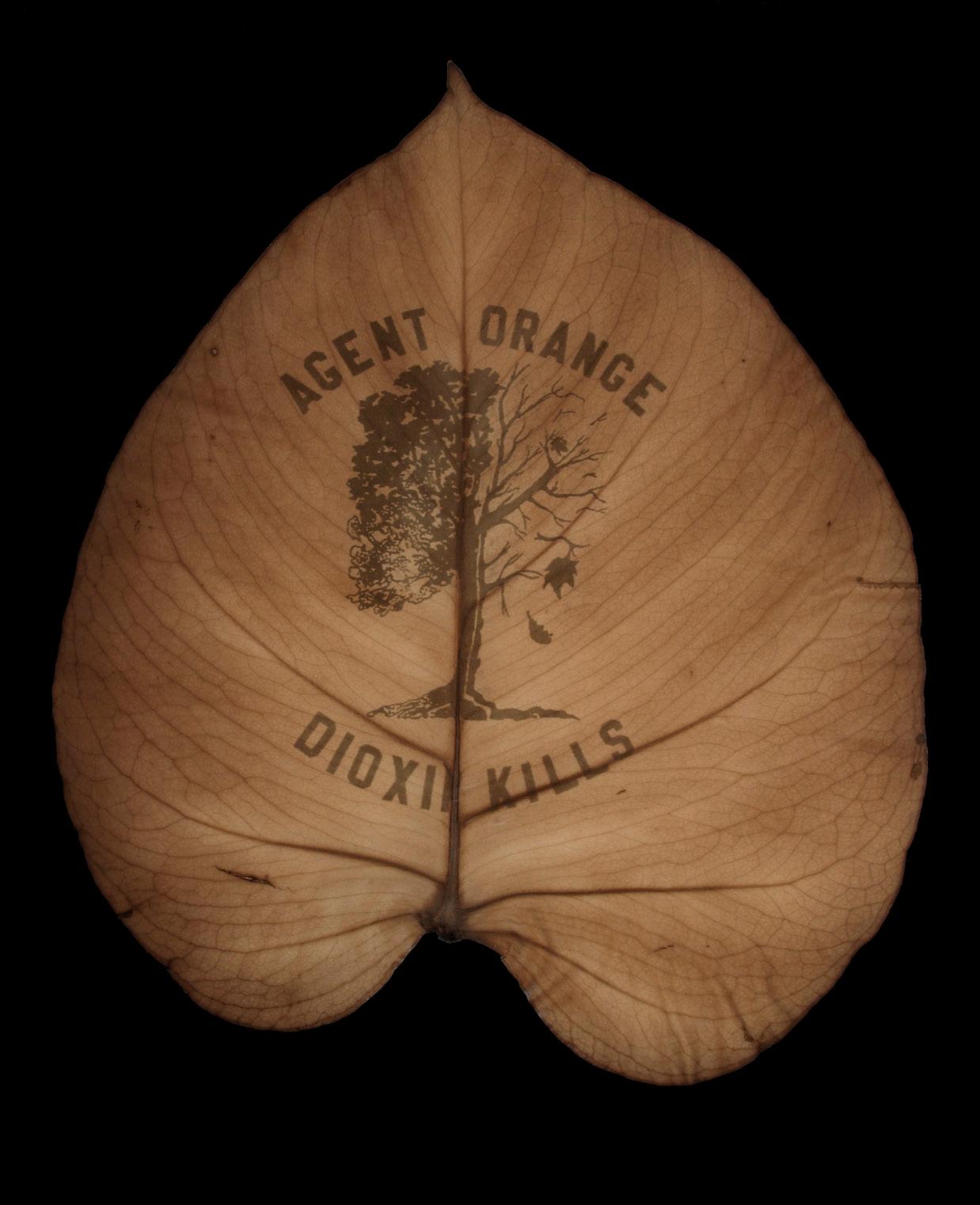

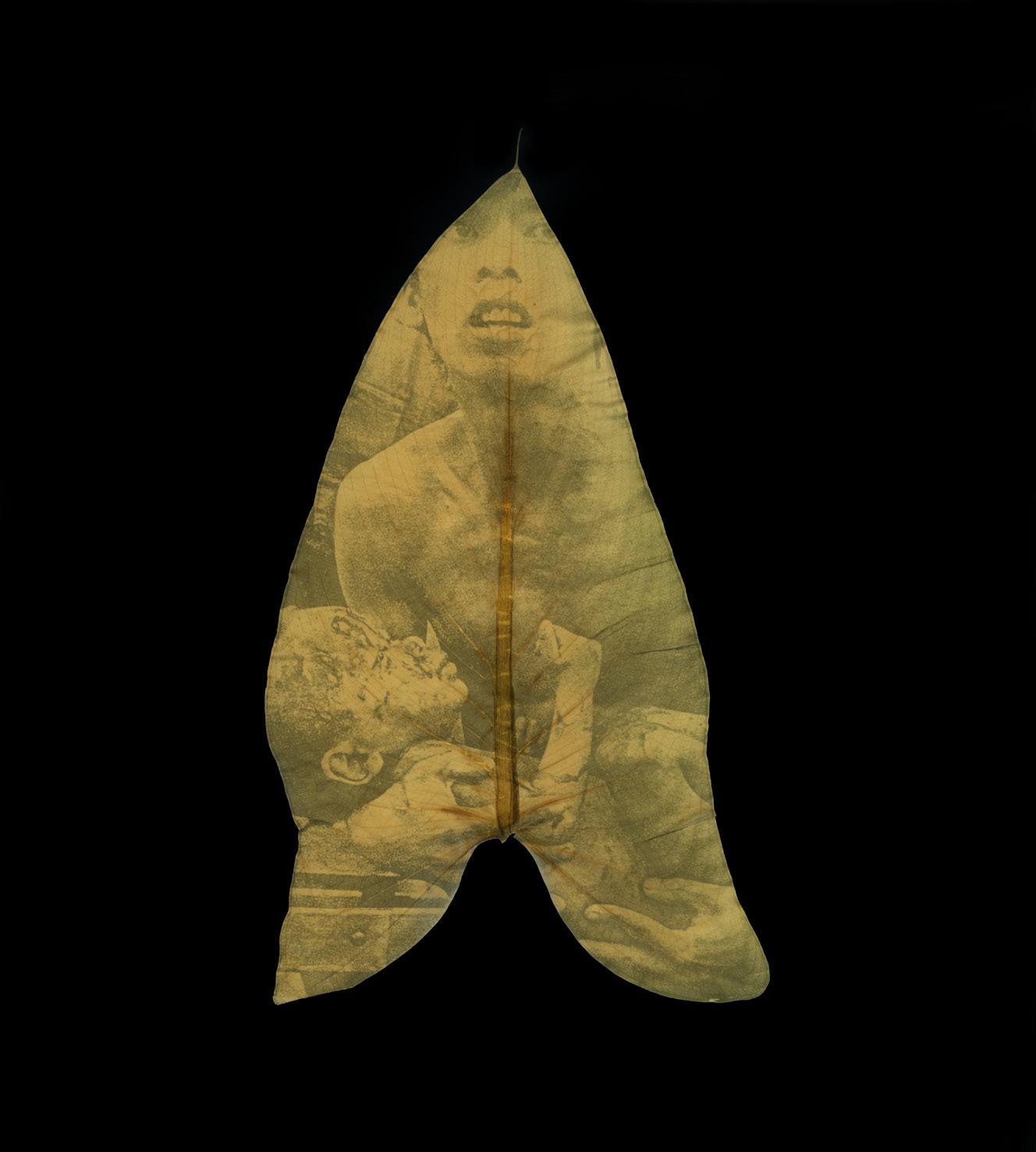

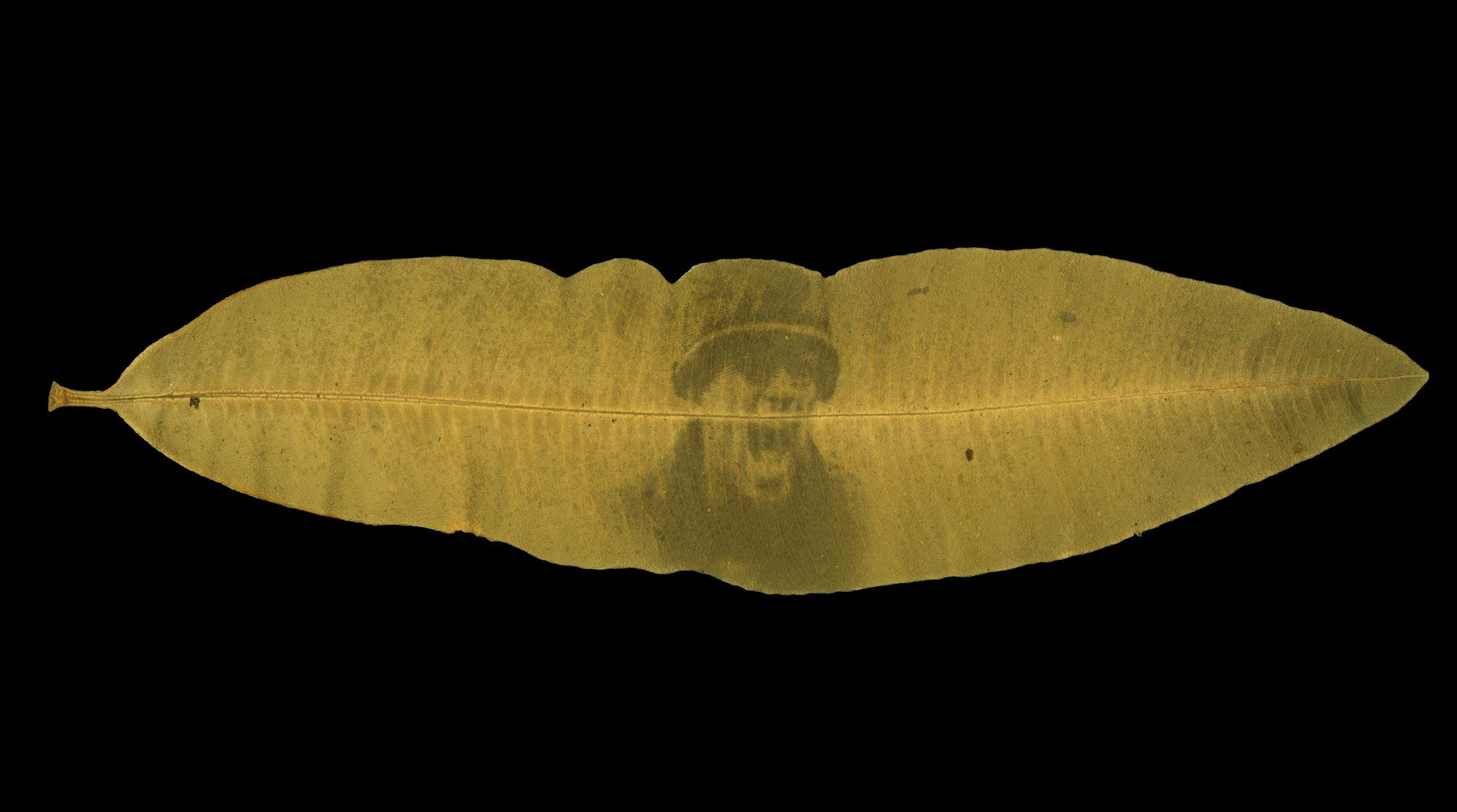

Binh Danh, Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War, 2008 Courtesy of the artist

Binh Danh was born in a Southern Vietnamese fishing village two years after the end of the Vietnam War. When Danh was a toddler, his family was among the “boat people” who fled the country and relocated from a refugee camp in Malaysia to San Jose, California. The artist invented the chlorophyll printing process, in which photographic images appear embedded in leaves through photosynthesis. The leaves are then cast in resin, like biological samples for scientific studies. This process deals with the idea of elemental transmigration: the decomposition and composition of matter into other forms. Danh’s images of war are part of the leaves and live inside and outside of them. The leaves express the continuum of war, and they contain the residue of the Vietnam War: bombs, blood, sweat, tears, and metals. The dead have been incorporated into the landscape of Vietnam during the cycles of birth, life, and death. As matter is neither created nor destroyed, but only transformed, the remnants of the war live on forever in the Vietnamese landscape.

Binh Danh, Dioxin Kills, Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War, 2008, chlorophyll print and resin

Courtesy of the artist

Binh Danh, Holding #1, Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War series, 2009, chlorophyll print and resin

Courtesy of the artist

9

Binh Danh, Holding #2, Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War series, 2009, chlorophyll print and resin Courtesy of the artist

Binh Danh, In the Realm of Pain, Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War series, 2005, chlorophyll print and resin Courtesy of the artist

10

Binh Danh, Operation Rolling Thunder, Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War series, 2005, chlorophyll print and resin Courtesy of the artist

11

Binh Danh, Backs of Men, Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War series, 2004, chlorophyll print and resin

Courtesy of the artist

Binh Danh, Drifting Souls, Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War series, 2010, chlorophyll print and resin

Courtesy of the artist

12

Binh Danh, Soldier in Action, Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War series, 2003, chlorophyll print and resin

Courtesy of the artist

Binh Danh, The Interrogation, Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War series, 2003, chlorophyll print and resin

Courtesy of the artist

13

Binh Danh, Untitled (Combat 2), Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War series, 2008, chlorophyll print and resin

Courtesy of the artist

Binh Danh, Untitled (Parts of War), Immortality: The Remnants of the Vietnam and American War series, 2005, chlorophyll print and resin

Courtesy of the artist

14

14

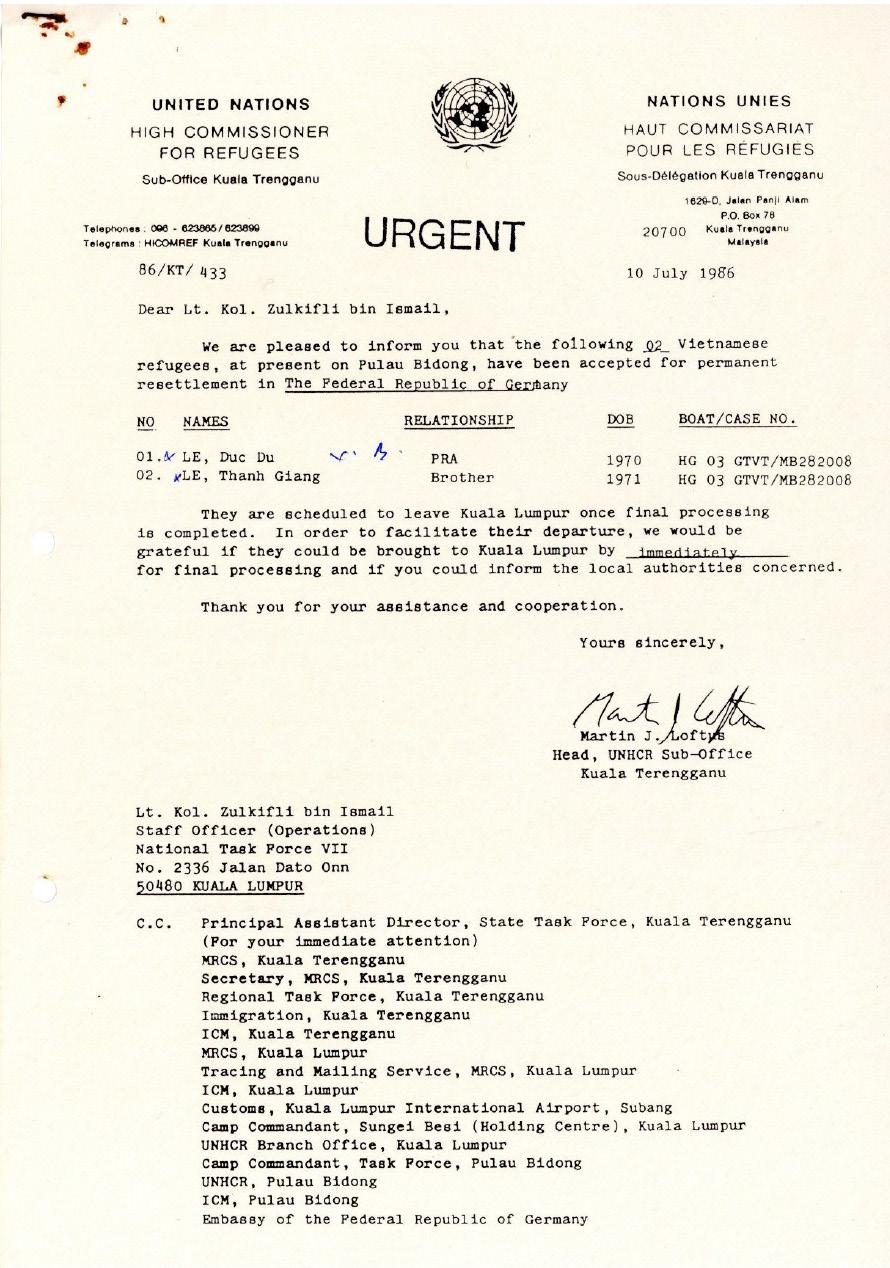

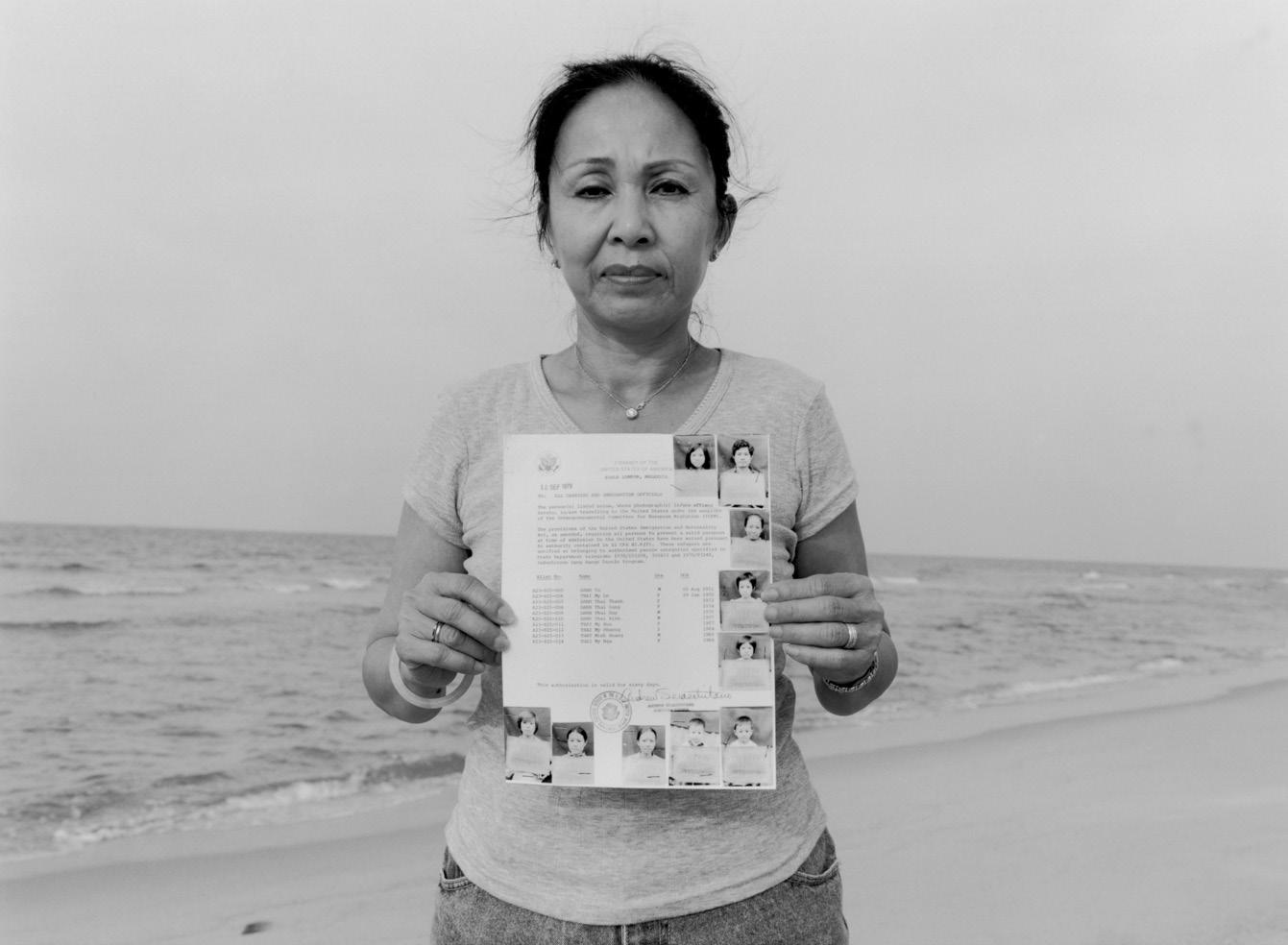

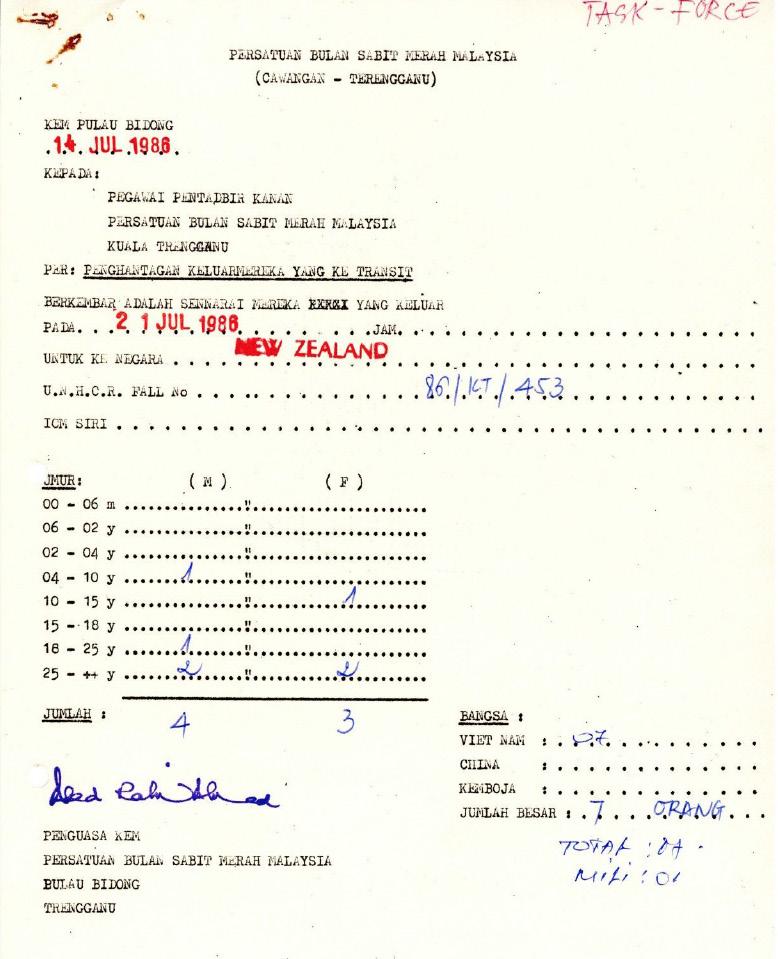

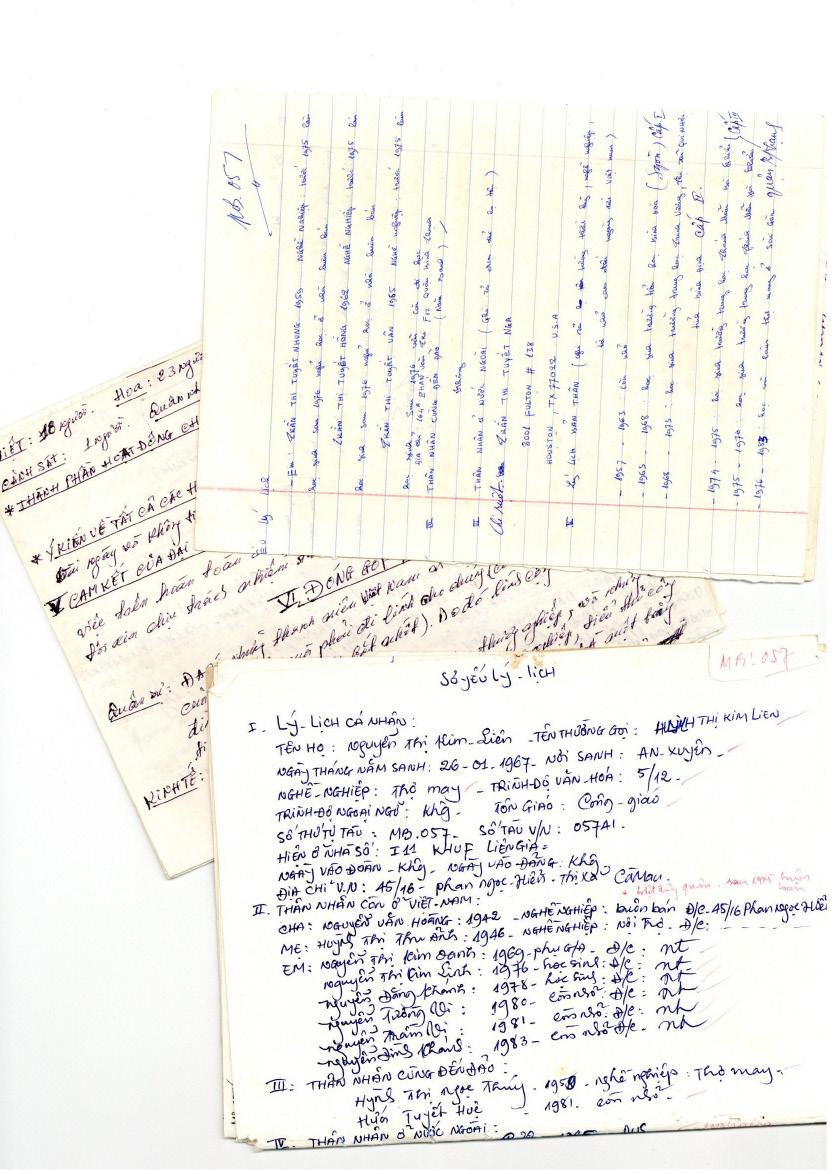

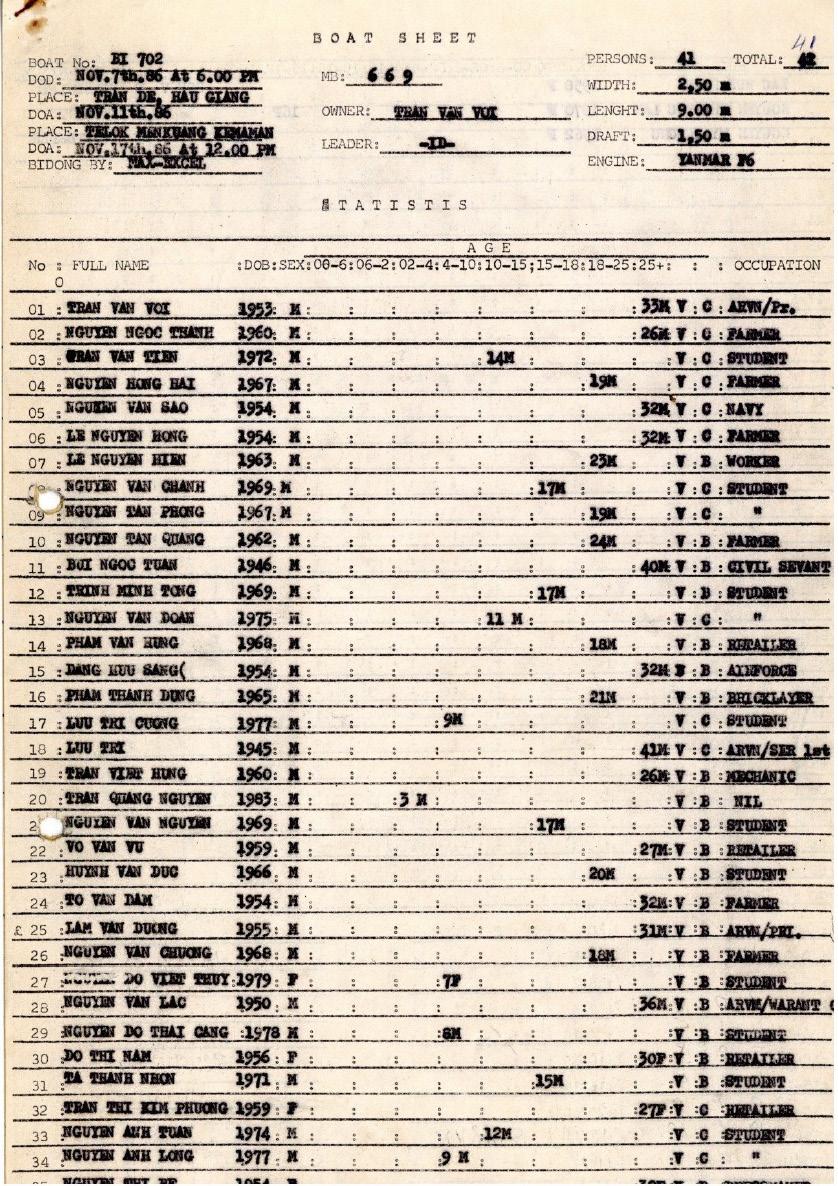

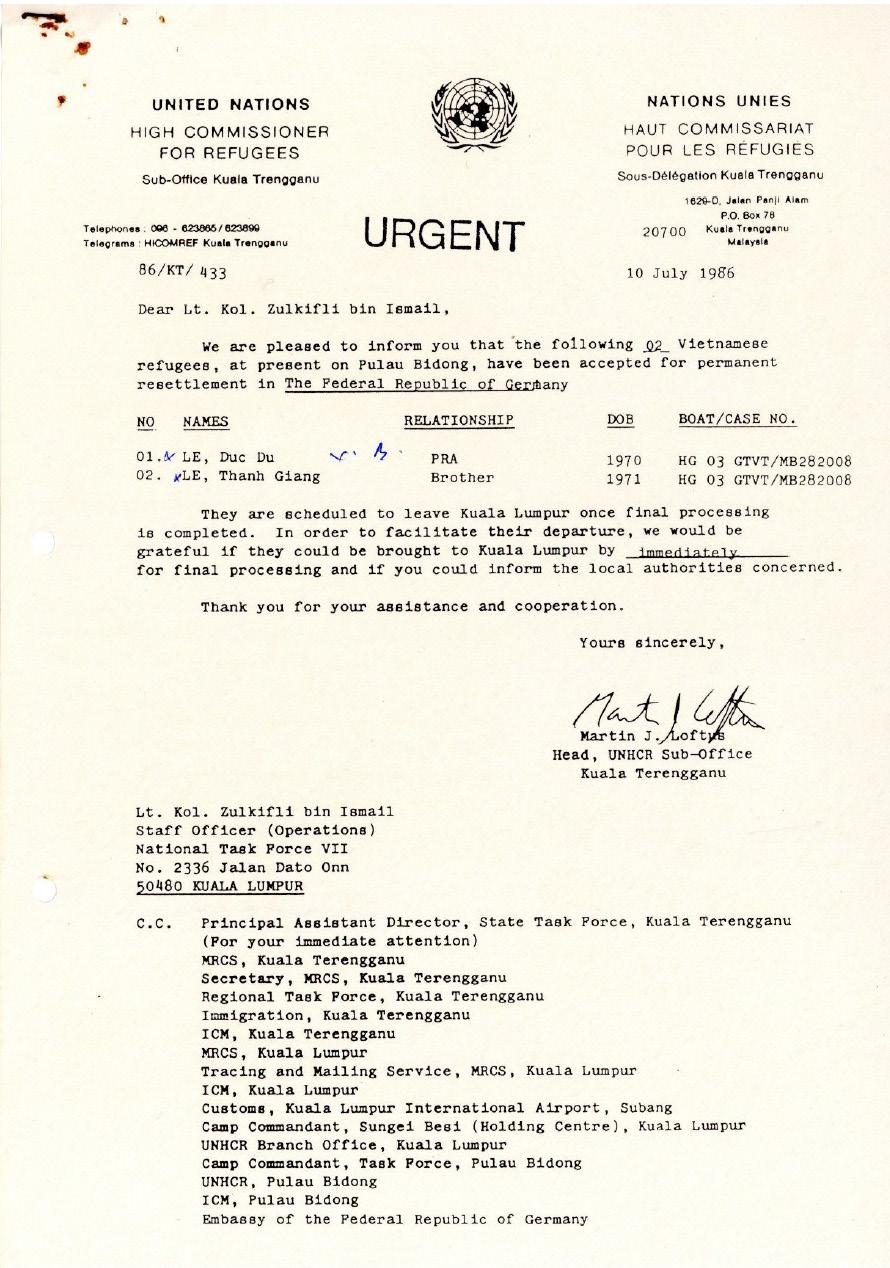

Binh Danh, Untitled, From the Pulau Bidong Island: Southeast Asian Refugee Camp, 2002, silver gelatin prints

During the summer of 2002, Binh Danh and his mother visited the abandoned island of Pulau Bidong, off the coast of Malaysia, the site of the Vietnamese refugee camp where they had lived. Danh and his mother explored the island and its deserted buildings by taking photographs and gathering ephemeral documents, including letters, testimonies, and government records. Some contained wormholes, others were partially buried under dirt with plants growing through them, taken over by nature and exposure to the elements.

Binh Danh, Blurred Memories (Boardwalk), Untitled, From the Pulau Bidong Island: Southeast Asian Refugee Camp, 2002, silver gelatin print

Courtesy of the artist

The photograph shows remnants of the dock on Pulau Bidong. After being rescued and taken onto a larger ship, the refugees would deboard here and walk to the island.

15

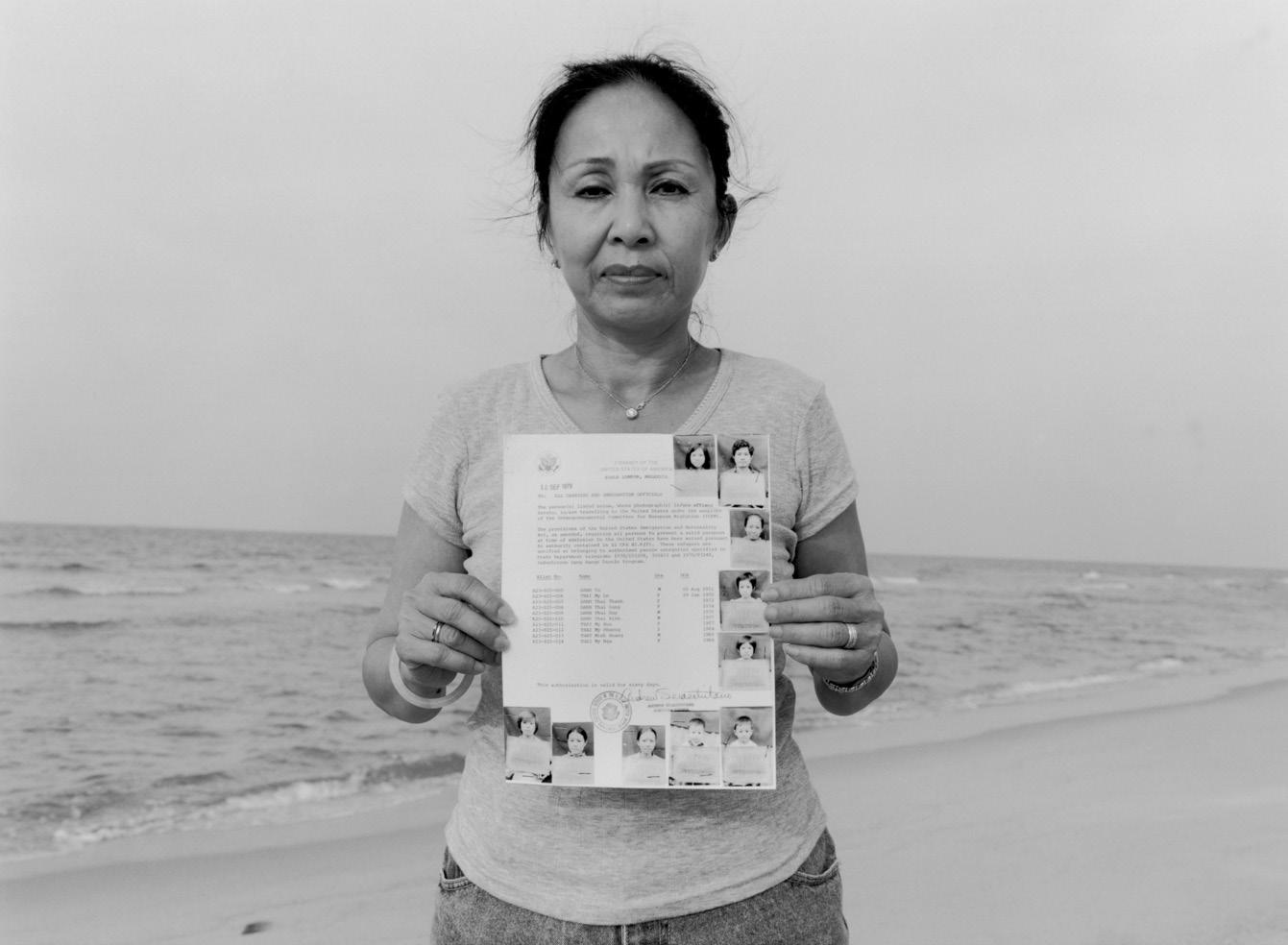

Binh Danh, Blurred Memories (Mom), Untitled, From the Pulau Bidong Island: Southeast Asian Refugee Camp, 2002, silver gelatin print

Courtesy of the artist

Binh Danh’s mother holding the immigration document that allowed them entrance as refugees into the United States in 1979.

Binh Danh, Blurred Memories (Old Father Bidong Monument), Untitled, From the Pulau Bidong Island: Southeast Asian Refugee Camp, 2002, silver gelatin print

Courtesy of the artist

Old Father Bidong is a mythological figure named after the island. Families would dedicate plaques to him in different languages—“Thanks to Old Father Bidong”—honoring him for their survival. Refugees from Cambodia and Laos were in the Pulau Bidong camp as well.

16

Binh Danh, Blurred Memories (Paperwork), Untitled, From the Pulau Bidong Island: Southeast Asian Refugee Camp, 2002, silver gelatin print

Courtesy of the artist

The artist and his mother collected as many artifacts from the island as they could carry, including testimonies, governmental records, and ID cards— paperwork left behind by either the refugees or the refugee support organizations.

Binh Danh, Blurred Memories (A Homage to the Boat), Untitled, From the Pulau Bidong Island: Southeast Asian Refugee Camp, 2002, silver gelatin print

Courtesy of the artist

Refugees often converted fishing boats to use for their escape. According to the artist’s mother, they would pretend to go fishing in the early morning to evade the officials. There would be ice blocks on the top deck, hiding the refugees below deck. Though there were a few remnants of boats on the island, most of the converted fishing boats were destroyed after humanitarian organizations rescued the refugees.

Binh Danh, Blurred Memories (Boat Drawings), Untitled, From the Pulau Bidong Island: Southeast Asian Refugee Camp, 2003, silver gelatin print

Courtesy of the artist

Many of the walls inside the remaining buildings on Pulau Bidong have graffiti or messages left by people who lived in the camp or who have visited the island since its closing.

17

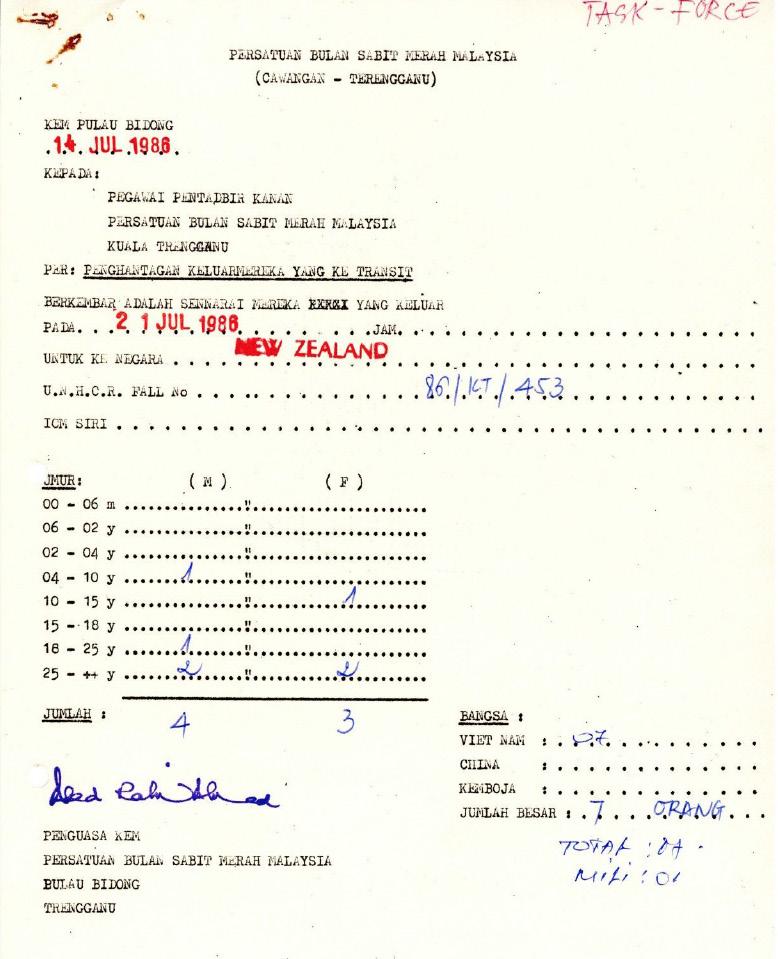

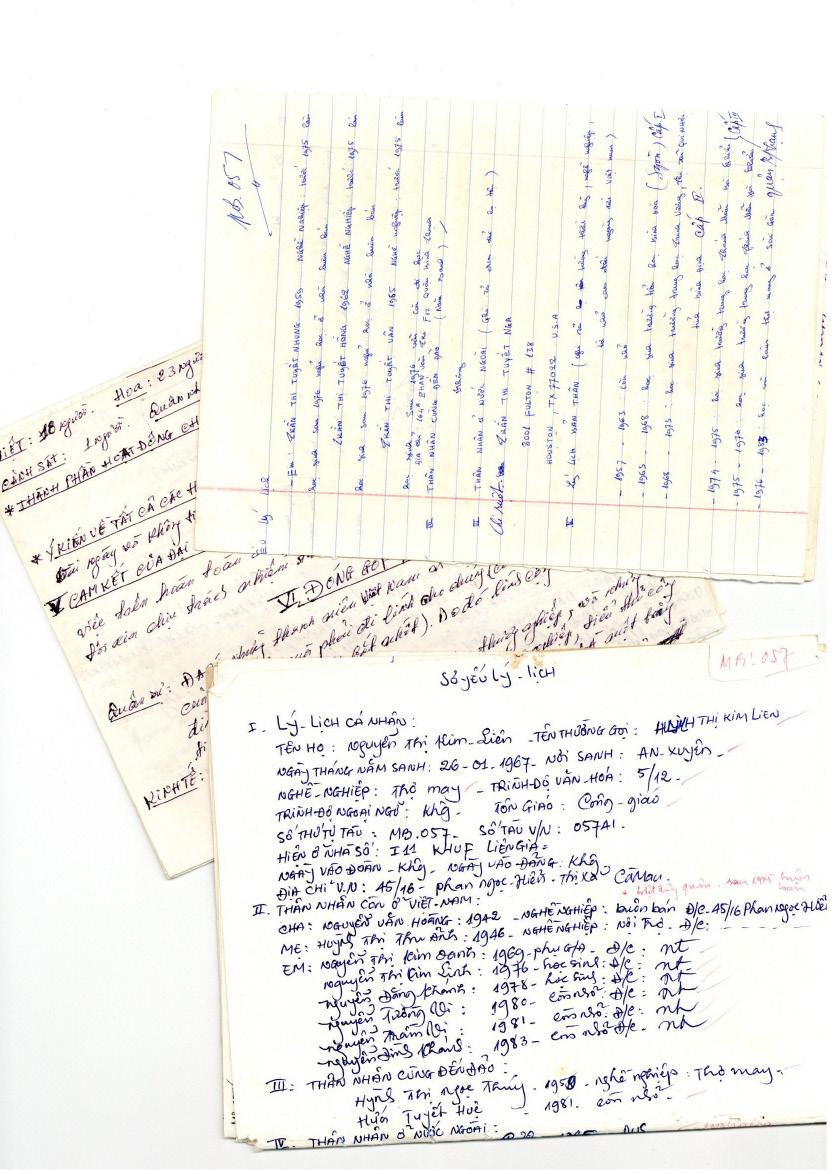

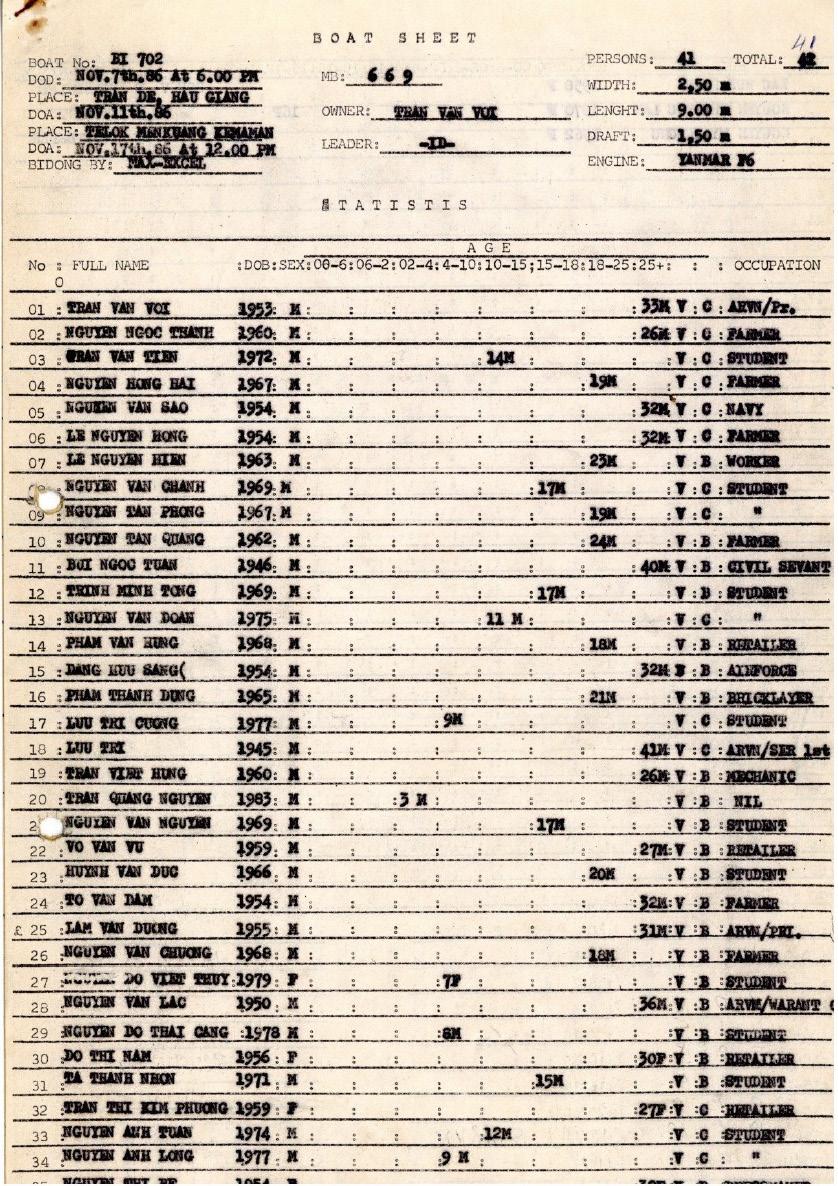

Binh Danh, Set of Documents, 2002, UNHCR documents, boat sheets, and written testimonies seeking asylum found on Pulau Bidong island Courtesy of the artist

18

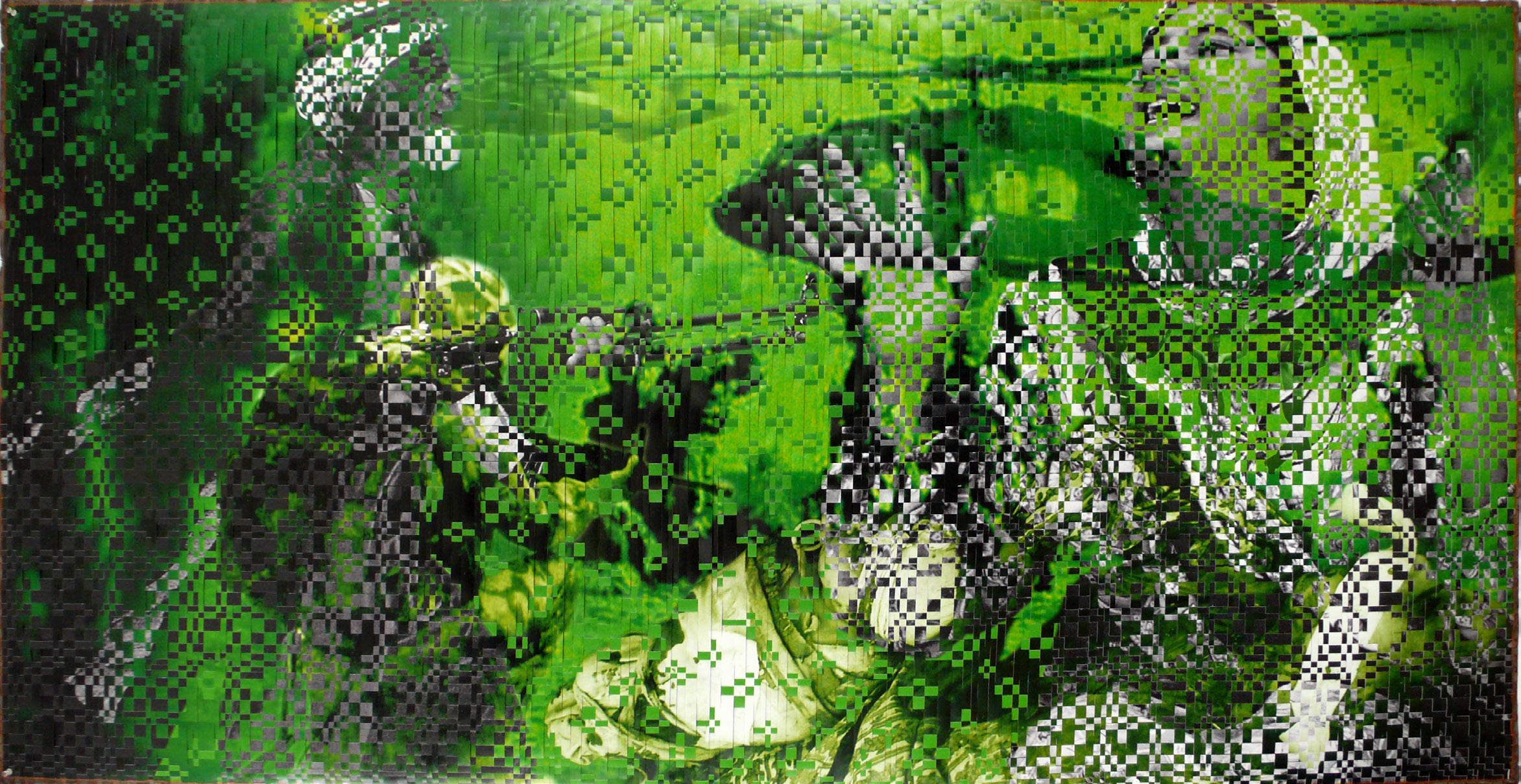

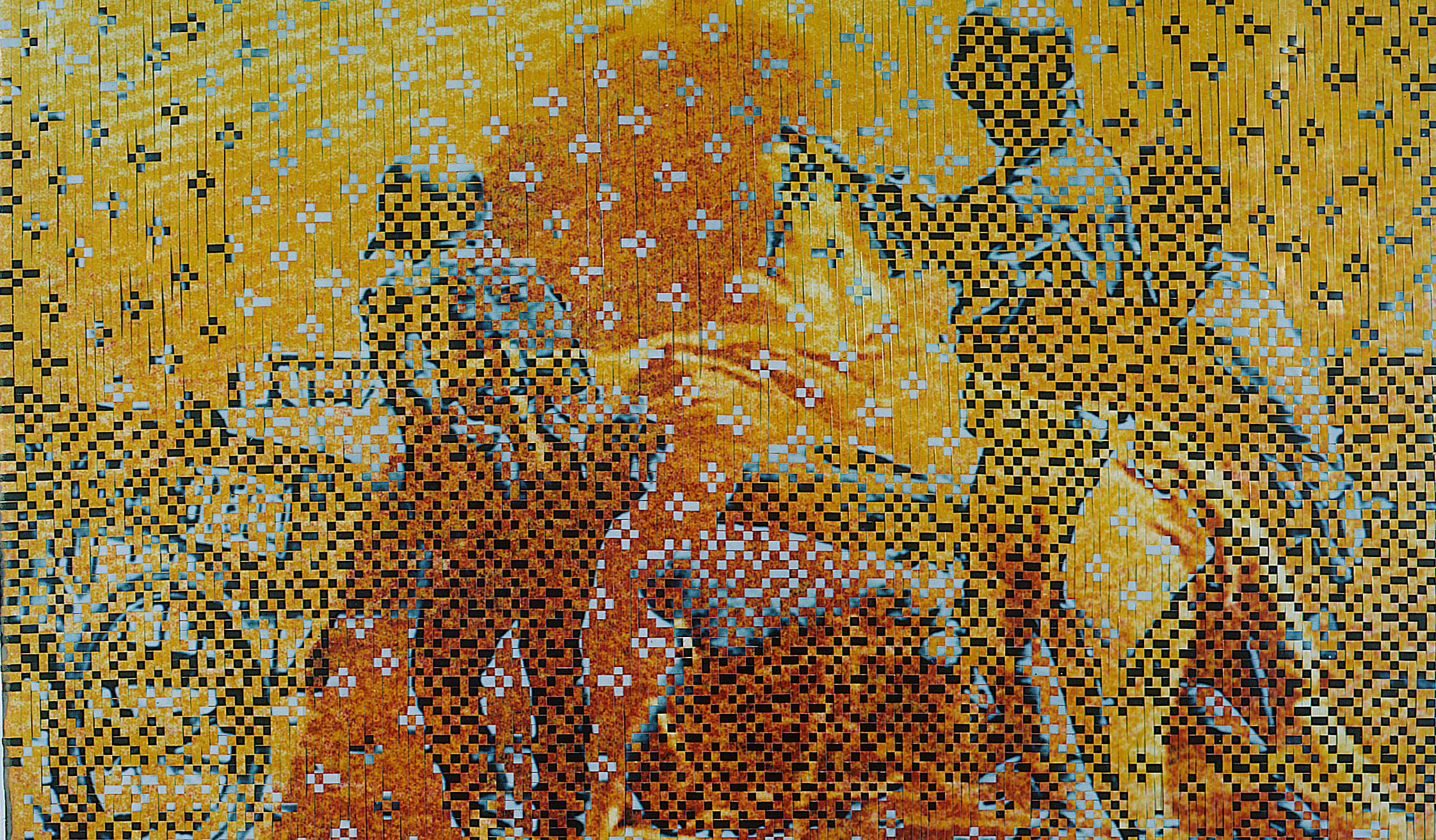

Dinh Q. Lê

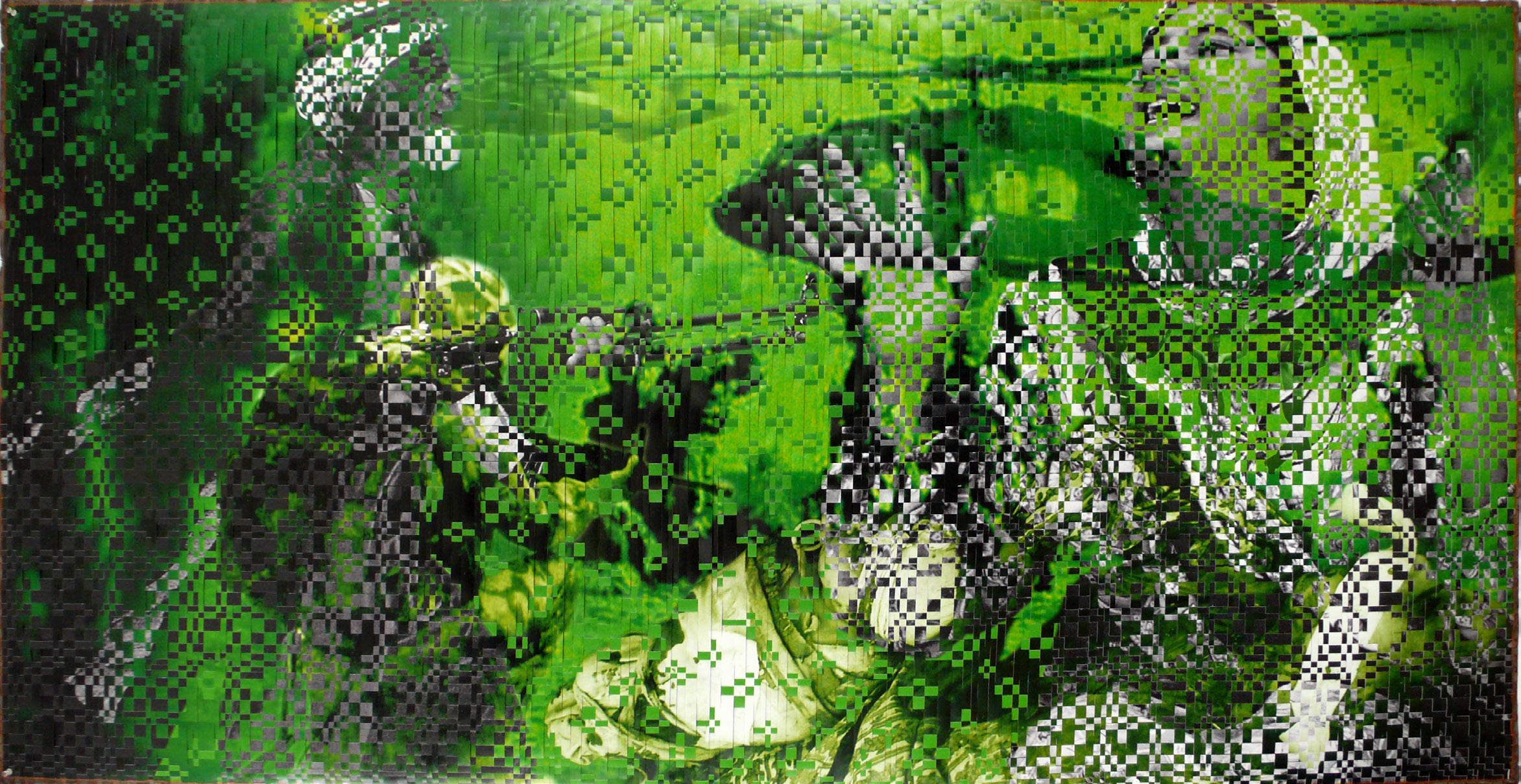

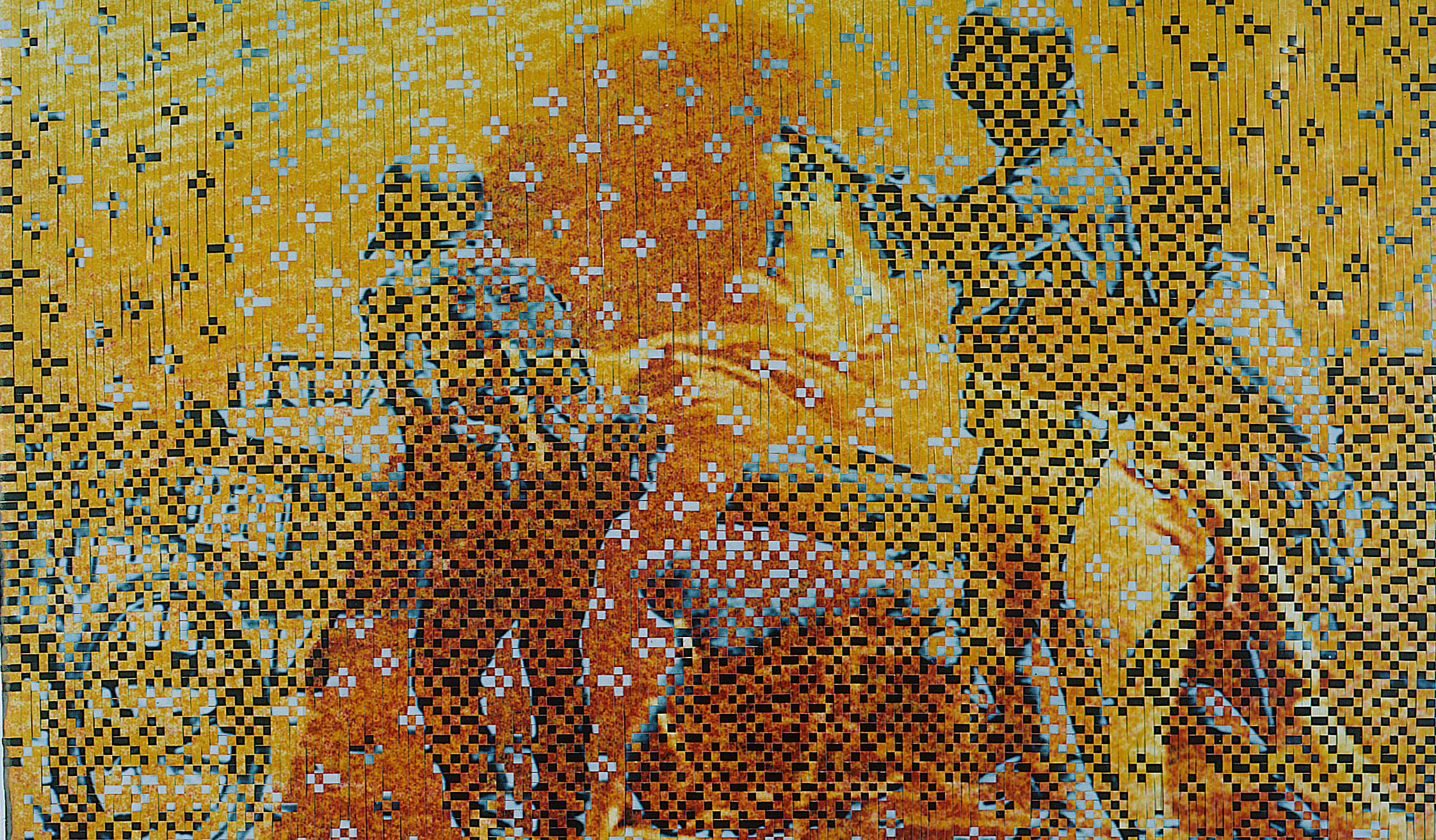

Dinh Q. Lê left his birth country of Vietnam at age ten, when his family fled the Communist regime and the Khmer Rouge and settled in the United States. Lê splices, interweaves, and distorts photographs to explore his own relationship to Vietnam’s complicated cultural and political history. Lê now divides his time between Ho Chi Minh City and Los Angeles. By using a photo weaving technique, Lê creates large-scale photographic montages. He layers the images in a repeating pattern of glossy tapestries made entirely of chromogenic prints and uses linen tape to finish the edges with meticulous and precise craftsmanship. Synthesizing his own memory and perception with popular depictions in the film industry and in journalism from Western and Eastern cultures, Lê reframes the history of Southern Vietnam, challenging censorship, exploitation, and propaganda from all sides.

This work features a dense layering of images from Vietnam, Iraq, and the September 11 attacks in the US. Figures and scenery wander and seethe across the picture plane, melding the past with the present. The faces of the victims and soldiers become universal in their expressions and actions. Repetition and timelessness play with the concrete and acutely detailed scenes in a meditation relevant to both human nature and US foreign relations. Lê reminds us of our flawed politics in Vietnam and the negligence of repeating similar atrocities.

Dinh Q. Lê, Night Vision, 2008, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Dinh Q. Lê, Night Vision, 2008, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

19

Lê weaves together black-and-white photographs taken during the Vietnam War with richly colored stills from Hollywood films based on that war. He proposes that this collective memory consists of three parts; the media’s images, Hollywood fiction, and personal memory. By merging and layering reality and fiction, Lê references our collective memory and experiences of the Vietnam War, which become more ambiguous and deteriorate over time.

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled 3, 2004, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled 3, 2004, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

20

Dinh Q. Lê, The Ghosts of our Past, 2008, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Here Lê incorporates stills taken from The Deer Hunter, Apocalypse Now, and Born on the Fourth of July. The resultant work, which blends images of reality and fiction, indicates that while Hollywood films have helped America come to terms with the war, they also have contaminated our collective memory of the Vietnam War, which is slowly being replaced by cinematic images.

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled (The Persistence of Memory), 2000–01, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled (The Persistence of Memory), 2000–01, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

21

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled (The Children), 2004, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

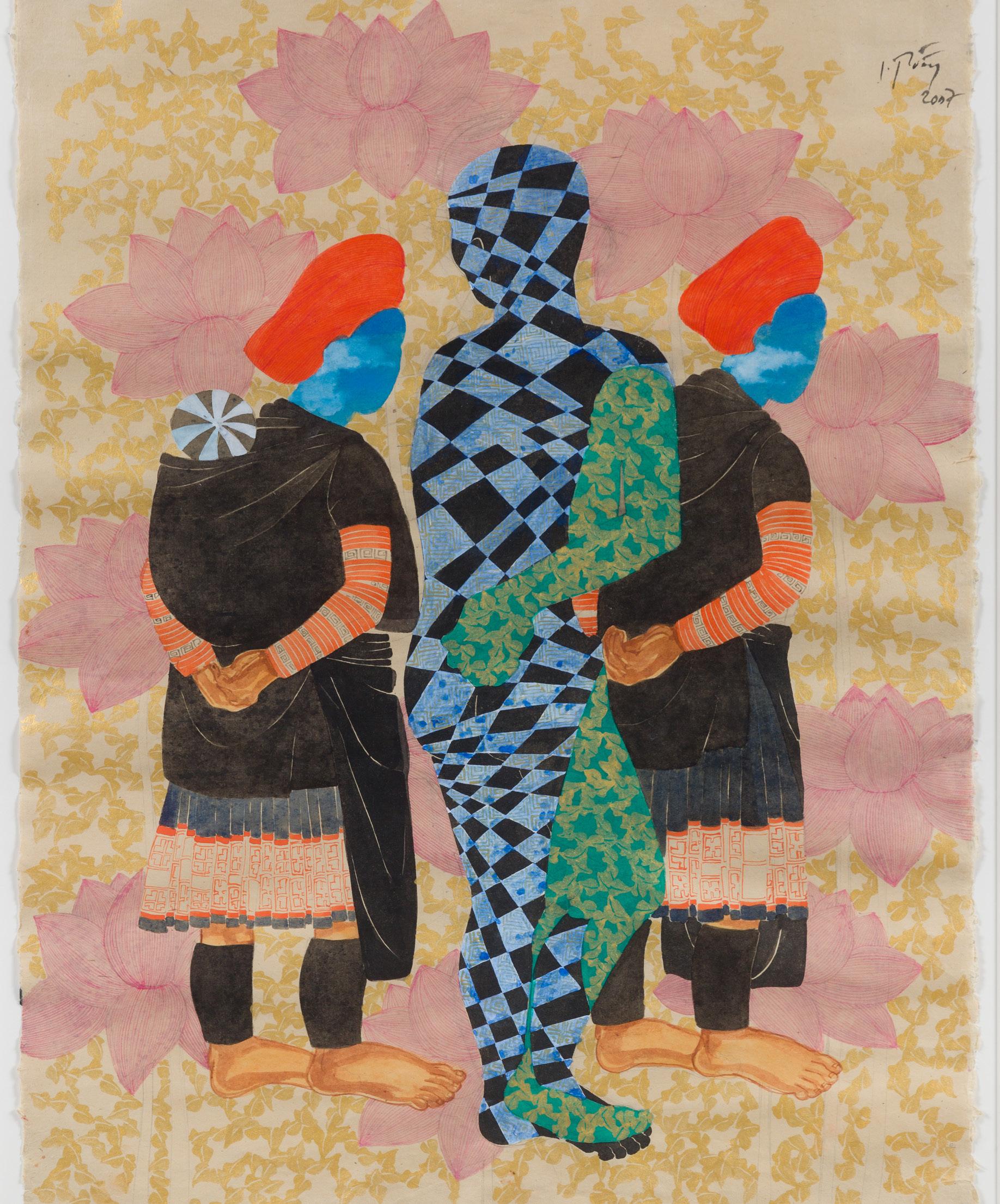

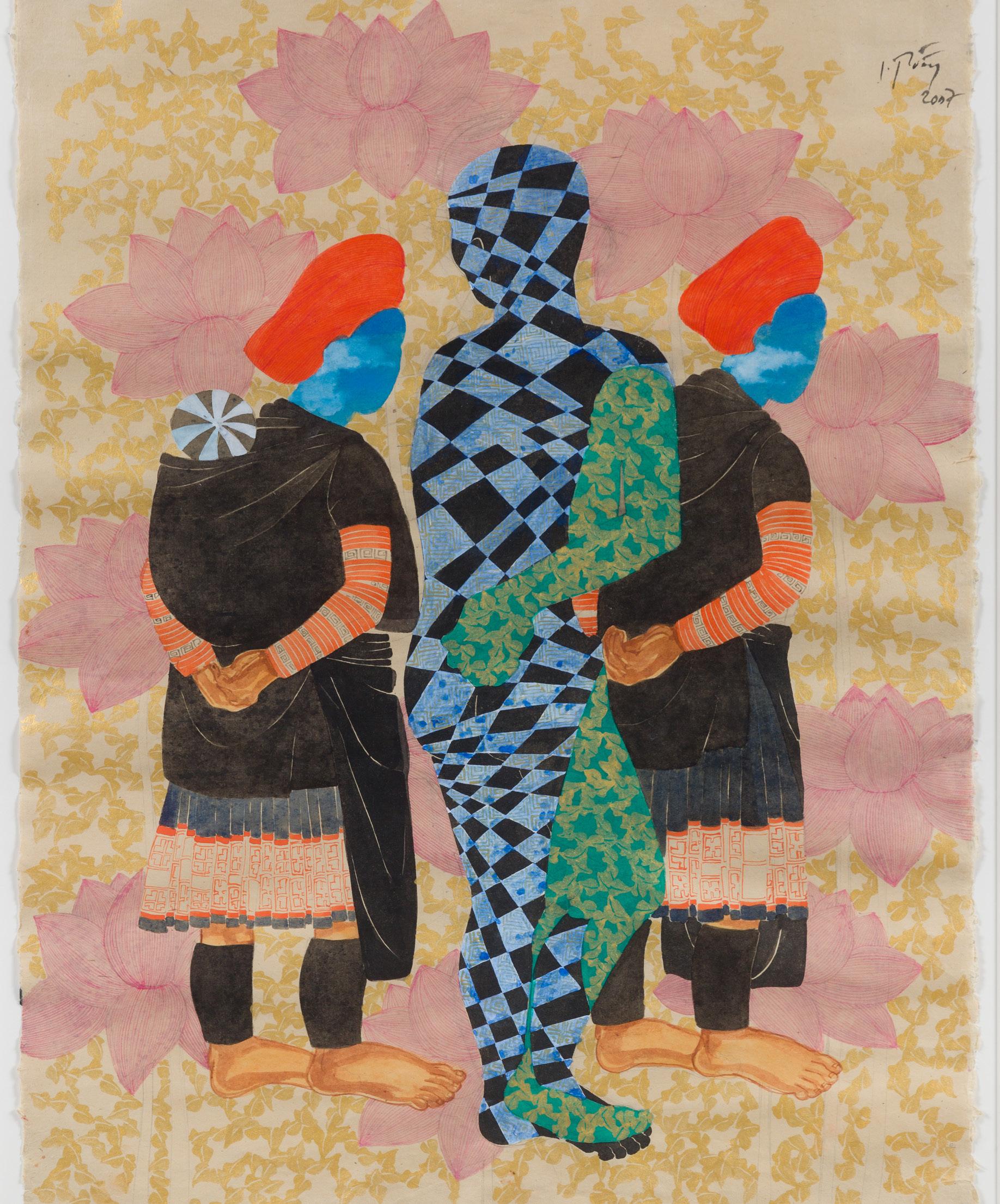

Dinh Thi Tham Poong

Dinh Thi Tham Poong, Following Nature’s Way, 2007, watercolor and gold paint on handmade paper Courtesy of the artist and Judith Hughes Day, Vietnamese Contemporary Fine Art

Poong’s art focuses on balance in the environment, life’s transitions, and women’s role in society. In this painting, the central figure is a contemporary woman, possibly the artist herself, who looks back on her H’Mong heritage represented by two mothers, each with a child on their back. Poong employs several symbols: a checkerboard pattern represents balance in life between the modern and the traditional, between nature and humanity; sky faces are evidence of the figures being attuned to their environment, their large bare feet showing their link to the earth; and lotuses as signs of femininity and of Buddhist transformation.

22

Dinh Thi Tham Poong, Sound of the Khen, 2008, watercolor and gold paint on handmade paper

Courtesy of the artist, Madam Zarina Varukatty, and Burhan Gafoor, Ambassador and Permanent Representative for Singapore to the United Nations

Poong, who descends from two of Vietnam’s fifty-two ethnic minorities, the H’Mong and the Dai, remembers the khen, a musical instrument of the H’Mong minority in North Vietnam made of bamboo connected to a hollowed-out hardwood reservoir into which air is blown, producing soothing sounds. On traditional handmade paper, Poong illustrates two men and a boy of H’Mong heritage listening to another boy playing the now rare instrument. The khen and its music pass through the head of a fifth-spirit figure, evoking remembrance.

Dinh Thi Tham Poong, Women’s Talk, 2009, watercolor and gold and silver paint on handmade paper

Courtesy of the artist and Judith Hughes Day, Vietnamese Contemporary Fine Art

Poong painted several women in thought and conversation. The lowered window in the background implies looking into the past and transitioning into the present. The checkerboard patterns on the figures refer to their balance with their natural environment, as symbolized by the flowers, and energy in their lives. For Poong, these background patterns represent happiness and a long life.

23

Hoang Duong Cam

Ho Chi Minh City-based artist Hoang Duong Cam works in painting, photography, video, installation, performance, and collaborative projects. Many of his works explore the complex mechanisms that connect the self and its surroundings. The manifold connections between our inner selves and meaningful places are the topic of his series Representation in the Meaning of a Metaphor for a Forest as Endoscopy / Links Between Locations. Places of memory, loss, or rediscovery are seen as projections from the inner world to the outside world. The series, which consists of hundreds of combined digitally altered images, including the almost hidden presence of the artist, depicts places layered with history and personal memories and asks questions about the interplay between “self” and “environment.”

Hoang Duong Cam, No. 1 – Venice Apartment, Representation in the Meaning of a Metaphor for a Forest as Endoscopy / Links Between Locations, 2008, photomontage Courtesy of the artist

Cam traveled to Europe for the first time in 2007 as a Vietnamese artist participating in Migration Addicts, a satellite exhibition in conjunction with the Venice Biennale that year. There was no Vietnam Pavilion at the time, and no Vietnamese artist had ever participated in the Biennale. Cam focused his interests on the issues of the boundaries that might or might not exist between worlds, landscapes, peoples, and even within the artist himself; this work is the first of the series. Cam created an image of himself as part of the surrounding landscape, in this case the residential area where his group of artists was staying during the Venice Biennale, with the details appearing as if seen through a camera lens during an endoscopy.

24

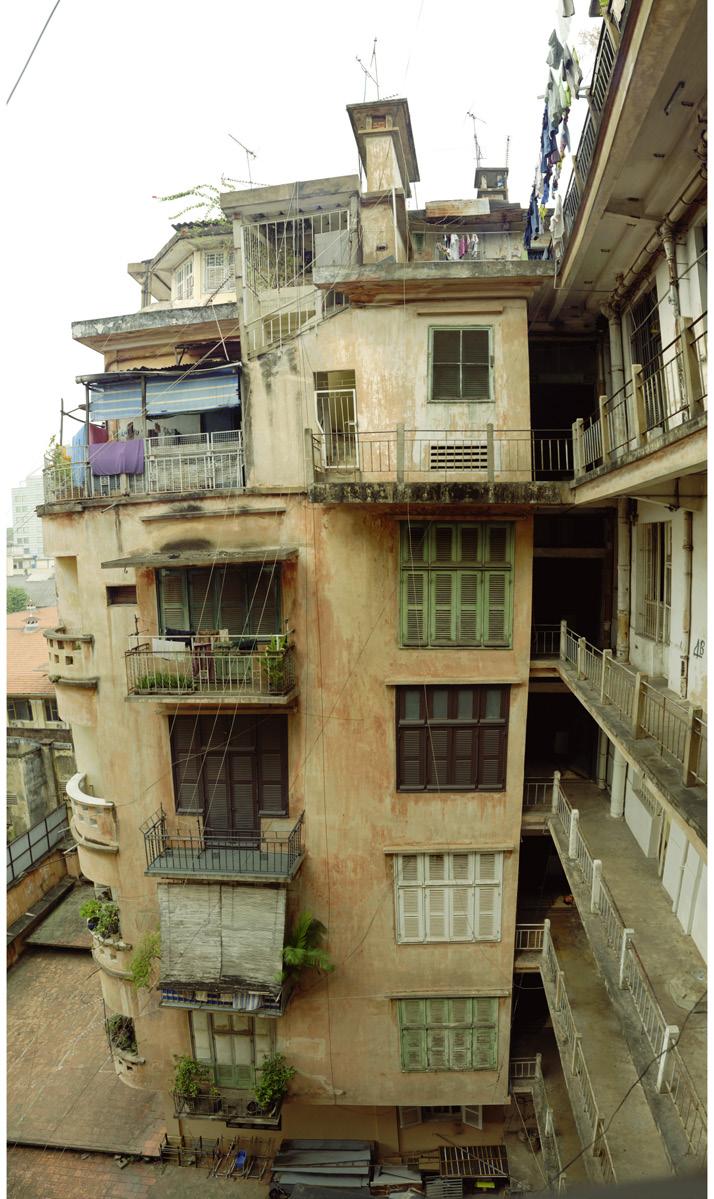

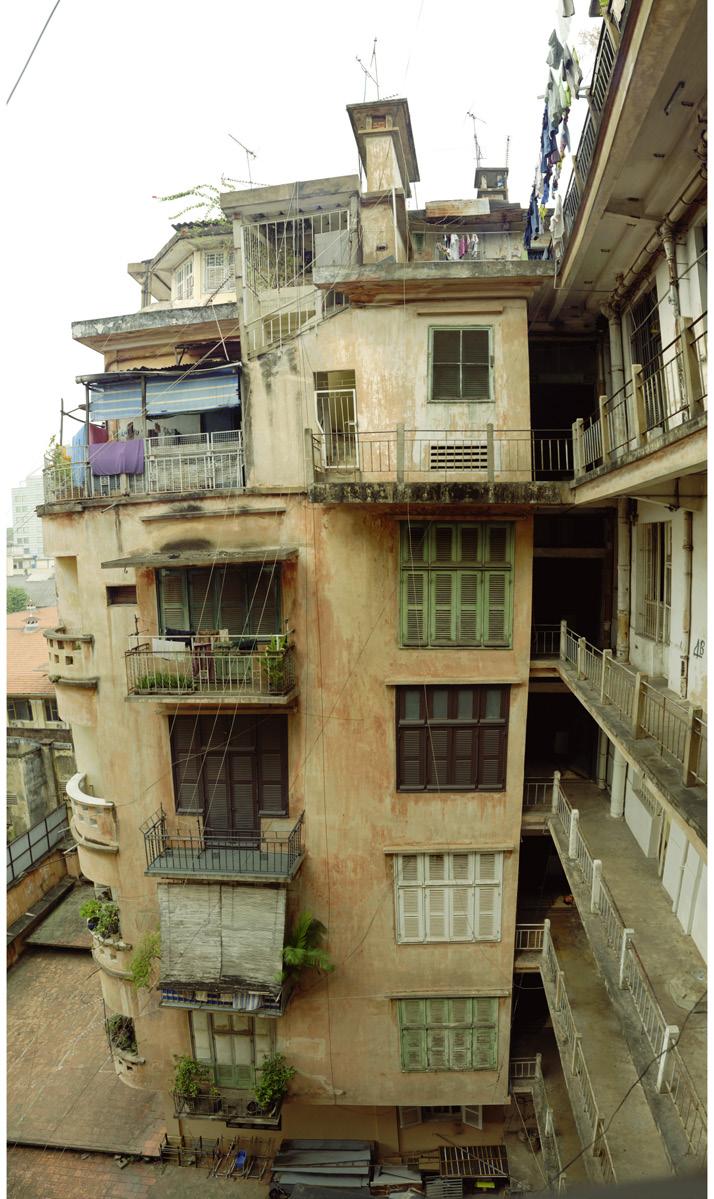

Hoang Duong Cam, No. 2 – Saigon Apartment, Representation in the Meaning of a Metaphor for a Forest as Endoscopy / Links Between Locations, 2008, photomontage

Courtesy of the artist

Saigon Apartment was photographed at an old apartment building from the French colonial period, located next to the city hall, where French offices were located before it was used as Ho Chi Minh City’s People’s Committee Office. The very location is described in Graham Green’s novel The Quiet American. After 1975, it was converted into a residential building, but because it lacked amenities, authorities added shared toilets in the corridor, which completely transformed the architecture—and created unpleasant smells. The building was demolished in order to be replaced by a high-end shopping mall, but the project is still pending and the space is currently empty. As in all the works of this series, the artist inconspicuously added himself to the photograph.

Hoang Duong Cam, No. 3 – The Hole, Representation in the Meaning of a Metaphor for a Forest as Endoscopy / Links Between Locations, 2008, photomontage

Courtesy of the artist

“The hole” is one of the many construction sites abandoned for years along Nhieu Loc Canal in Saigon; it became a place to dump garbage. There were many news reports about people falling into such holes with their motorbikes. Alden Pyre, the character in Graham Greene’s novel The Quiet American, was found here.

25

Hoang Duong Cam, No. 5 – Angkor Wat, Representation in the Meaning of a Metaphor for a Forest as Endoscopy / Links Between Locations, 2008, photomontage

Courtesy of the artist

In 2008, the artist’s family visited the Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia. Around this time, the first philosophy books became available in Vietnamese bookstores. Cam read all the books he could lay his hands on and brought one of Edmund Husserl’s ideas about phenomenology with him to Angkor Wat. When photographing the images for this work, the architectural details and bricks of the temple merged with Husserl’s ideas in Cam’s mind. In this photomontage, Cam also reflects on his childhood memories about propaganda TV.

26

Hoang Duong Cam, No. 7 – Long Bien Bridge, Representation in the Meaning of a Metaphor for a Forest as Endoscopy / Links Between Locations, 2008, photomontage

Courtesy of the artist

The Long Bien Bridge, originally named after French President Paul Doumer, was built during the French colonial period, marking the completion of Tonkin’s pacification process in 1899 to suppress Vietnamese resistance against French rule. The bridge has its own history, lasting over 100 years and figuring in many milestone moments in Vietnamese history. The artist, who grew up in Hanoi, used this bridge as a playground for many years. To this day it is a popular place for social gatherings.

27

Ngô Đình Bảo Châu

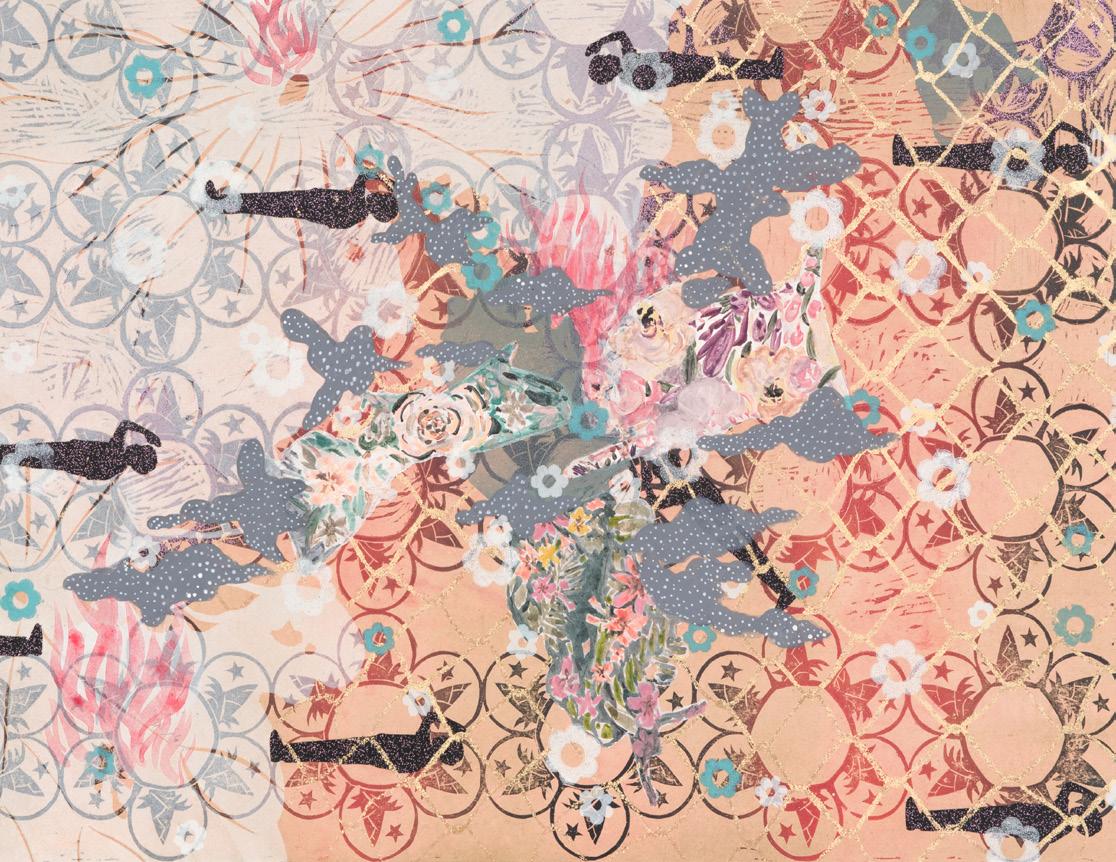

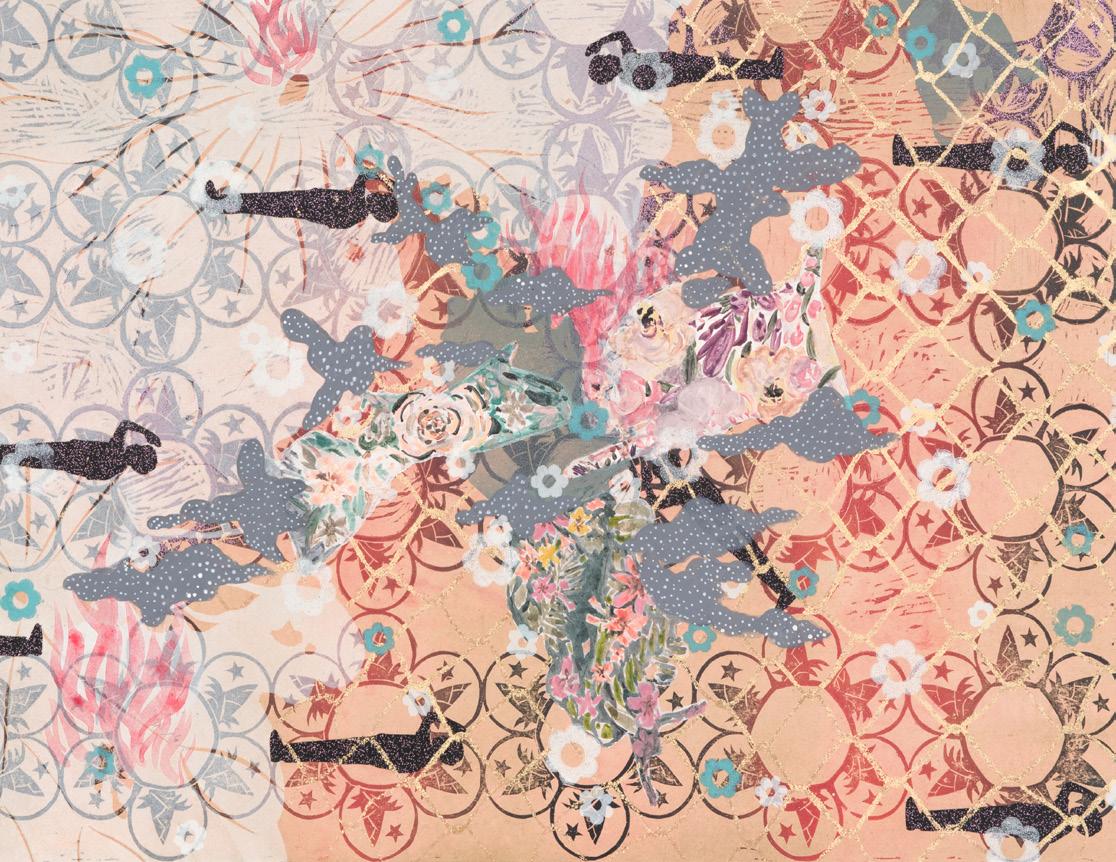

Ngô Đình Bảo Châu, Uniform, 2020, woodblock print, monoprint, stamping, stencil, acrylic, glitter, imitation gold leaf on cardboard

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Quynh

Hue- and Ho Chi Minh City-based artist Ngô Đình Bảo Châu has worked in a wide range of materials and techniques. In her wallpaper series, she uses motifs and objects from public life, referencing Vietnamese history and personal memory, and recreating the discontinuous and incomplete practice of remembering. The works evoke a nostalgia for things, events, and images that the artist has experienced but which are now someone else’s present and will be yet someone else’s future. Here we encounter măng non, a standardized symbol of the Ho Chi Minh Young Pioneer Organization, multiplied and arranged like a six-petal flower, hidden under smaller white floral motifs. The multitude of swirling flowers obscures the symbol and its original signifiers. These works combine images of chain-link fence, flowers, burning fires, shadows of monuments, and of a schoolboy saluting the flag. By turning public space into decorative wallpaper—a symbol of private space that is paradoxically shared in the public space of a museum—the artist adds a layer of reflection over the practice of everyday life.

28

Details: Ngô Đình Bảo Châu, Uniform, 2020, woodblock print, monoprint, stamping, stencil, acrylic, glitter, imitation goldleaf on cardboard

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Quynh

29

30

Nguyen Quang Huy

Hanoi-based artist and poet Nguyen Quang Huy focused for several years on monochromatic, photography-based paintings of women from several of Vietnam’s fifty-two ethnic minorities, visiting their villages in Vietnam’s northern highlands. After photographing his protagonists, Huy painted the portraits from memory, blurring the outlines to convey a sense of retrieved memory, in an attempt to capture the essence of the women’s inner lives.

Nguyen Quang Huy, Black H’Muong Girl VII, 2010, oil on canvas

Courtesy of the artist and Judith Hughes Day, Vietnamese Contemporary Fine Art

Nguyen Quang Huy, Flower H’Muong Girl IV, 2008, oil on canvas

Courtesy of the artist and Judith Hughes Day, Vietnamese Contemporary Fine Art

31

32

Nguyen Quang Huy, Black H’Muong Girl IV, 2008, oil on canvas Courtesy of the artist and Judith Hughes Day, Vietnamese Contemporary Fine Art

Nguyễn Thế Sơn

Nguyễn Thế Sơn, in collaboration with Trần Hậu Yên Thế, Changing Faces (Bottom and Face), 2016, video, duration 5:00 minutes

Courtesy of the artist and Trần Hậu Yên Thế

In this video, Hanoi-based artist and Vietnam National University professor Nguyễn Thế Sơn, in collaboration with artist and art researcher Trần Hậu Yên Thế, compares original architectural drawings of block apartment buildings in Hanoi from the 1950s to the 1980s to their recent condition in 2016. Many of the buildings between 1956 and 1965 were made of brick and designed by North Korean architects. After a building pause from 1965 to 1973 due to continual American bombings, architects from the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany supported the construction of a new generation of concrete apartment buildings. After the Doi Moi policy of economic liberalization, everything turned around and upside down. Private shops and enterprises were opened on the ground floor, and buildings were covered in billboards and advertisements. The artist shows the city as a palimpsest straining beneath layers of old and new, with billboards obscuring windows, balconies, and ancient remains, which gives his photographs the character of a relief.

33

Nguyen Van Cuong

Nguyen Van Cuong was born during the final years of the Vietnam War. In this series of lacquer plates, he reflects on the dramatic changes and transitions in Vietnamese society after the Doi Moi policy of economic liberalization, with its clash of traditional religion, communist ideology, and modern consumerism and entertainment.

Nguyen Van Cuong, Young Buddha, 2018, lacquer on wood

Courtesy of the artist and Judith Hughes Day, Vietnamese Contemporary Fine Art

Nguyen Van Cuong, Jazzy, 2018, lacquer on wood

Courtesy of the artist and Judith Hughes Day, Vietnamese Contemporary Fine Art

34

Nguyen Van Cuong, Transitions, 2018, lacquer on wood

Courtesy of the artist and Judith Hughes Day, Vietnamese Contemporary Fine Art

Nguyen Van Cuong, All In, 2018, lacquer on wood

Courtesy of the artist and Judith Hughes Day, Vietnamese Contemporary Fine Art

35

Phan Quang

Phan Quang, No. I, RE/Cover, 2013, digital c-print on paper

Courtesy of the artist

Ho Chi Minh City-based photographer Phan Quang started his career as a photojournalist for publications such as Forbes, New York Times, Vietnam Economic Times, and others before focusing on his art projects about microhistories. The series RE/Cover explores the lasting impact of Japanese soldiers stationed in Vietnam until 1955 and gives voice to the human stories that are not included in official historical narratives.

No. 1 depicts a man who was born in 1943 as the son of a Vietnamese woman and a Japanese soldier who got married in 1941. His identity card says he is Japanese, but he has never been to Japan.

Phan Quang, No. 5, RE/Cover, 2013, digital c-print on paper

Courtesy of the artist

This work shows a Vietnamese woman with the portrait of her husband, a Japanese soldier, who passed away in 1986. She has always worshiped her deceased husband according to Vietnamese custom.

36

Phan Quang, No. 8, RE/Cover, 2013, digital c-print on paper Courtesy of the artist

This work shows a woman who had three children with a Japanese soldier after they married in 1940. After the soldier went back to Japan, the woman always lovingly expected him to return to Vietnam, hugging the pillow with her husband’s waistcoat inside. The veil fabric covering the characters and visually connecting the series was purchased from a factory in Kyoto, Japan, established in 1955, the very year all Japanese soldiers returned from Vietnam. The fabric is used in Vietnam for bridal wear, whereas in Japan it is used in the production of kimonos.

37

Phung Huynh

Phung Huynh, Americanization, 2022, mixed media collage (laminated drawings, laminated collages, red polyester cord)

Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Gallery

Upon arriving in the United States, Phung Huynh and her family underwent a confusing process of “Americanization,” through which they had to navigate White dominant culture as well as the Chinese American community who preceded them. They were labeled as “FOBs” (fresh off the boat). When the family first moved to Los Angeles in 1981, they settled in Chinatown, in cultural proximity to an Asian community that was predominantly Chinese and East Asian. The artist’s installation of drawings peels back the layers of this complicated journey. Americanization includes drawings of the Vietnamese Madonna (Lady of La Vang); a Chinese cherub in the guise of a resistor; an old National Geographic magazine image of Chinese women in Shanghai getting a perm in 1980; photographs from a textbook that show one of the first Chinese families in California; and Chinese families in traditional clothing holding the American flag and pledging allegiance. Each piece is laminated in plastic, a reference to some immigrant’s tendencies such as covering furniture and remote controls in plastic, protecting and preserving everyday objects of value.

38

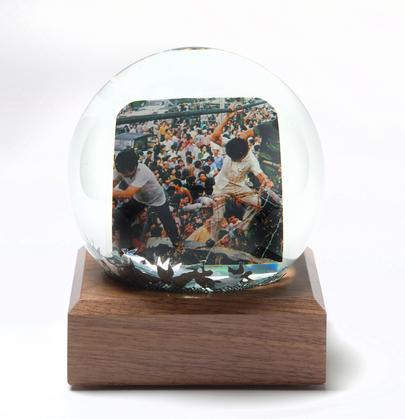

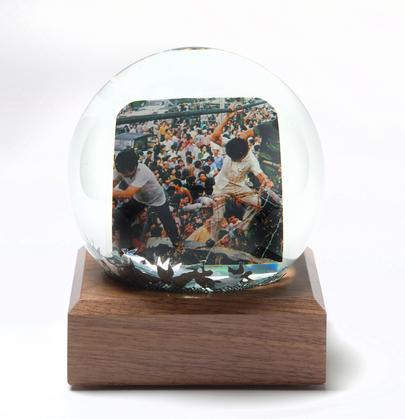

Phung Huynh, First Christmas, American Braised, 2021, snow globe, mixed media Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Gallery

While snow globes are traditionally used as decoration, filled with small dioramas of landscapes, small towns, or figures covered in snow to evoke a romantic feeling, oftentimes connected with the dream of a white Christmas, Phung Huynh’s snow globes convey a much more dramatic story: that of her family’s forced flight out of Vietnam at the closure of the war in April 1975. Each snow globe contains photographs from her early childhood. The Christmas theme refers to a coded message on the American Forces Network radio indicating that it was time to leave: “The temperature in Saigon is 105 degrees and rising,” followed by Bing Crosby singing “I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas.” American civilians, military members, and select Vietnamese families had been instructed to keep the signal secret, but the rumor spread, and thousands of families desperately tried to escape before it was too late.

39

Phung Huynh, Refugee Camp, American Braised, 2021, snow globe, mixed media Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Gallery

Phung Huynh, April 30, 1975, American Braised, 2021, snow globe, mixed media Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Gallery

40

Tuan Andrew Nguyen

Not the Smell of Napalm is a replica of foliage found in the jungle of Bataan, a province of the Philippine island of Luzon. Suggestive of a fossil, the carved leaves embody the memory of the land itself. Napalm was used extensively by the United States against entrenched Japanese forces in the Philippines during WWII and became a central weapon of the US military during the Vietnam War. Reports state that roughly 388,000 tons of American napalm bombs were dropped in the region between 1963 and 1973. In addition to its devastating effects on human targets and civilian bystanders alike, napalm bombs could create firestorms that burned through acres of jungle in a matter of seconds, leaving a defoliated landscape in its wake.

41

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Not the Smell of Napalm, 2019, hand-carved gmelina wood Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan New York

This is a replica of Bataan Death March Marker Mile 00, a white concrete obelisk that marks the start of the path taken by nearly 75,000 Filipino and American soldiers as prisoners of the Japanese Imperial Army after the Fall of Bataan on April 9, 1942. There are 138 Death March markers, one marking each kilometer. Placed beside a main road, they have been subject to damage, some accidental, some negligent, some intentional. The markers were erected by the Filipino-American Memorial Endowment Incorporated several decades after the war. While not directly related to Vietnam, this work exemplifies Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s practice to explore the power of memory and its potential to act as a form of political resistance worldwide. His practice is fueled by research and a commitment to communities who have faced traumas caused by colonialism, war, and displacement. Through his continuous attempts to engage with vanishing or vanquished historical memory, Nguyen investigates the erasures that the colonial project has brought to bear on certain parts of the world.

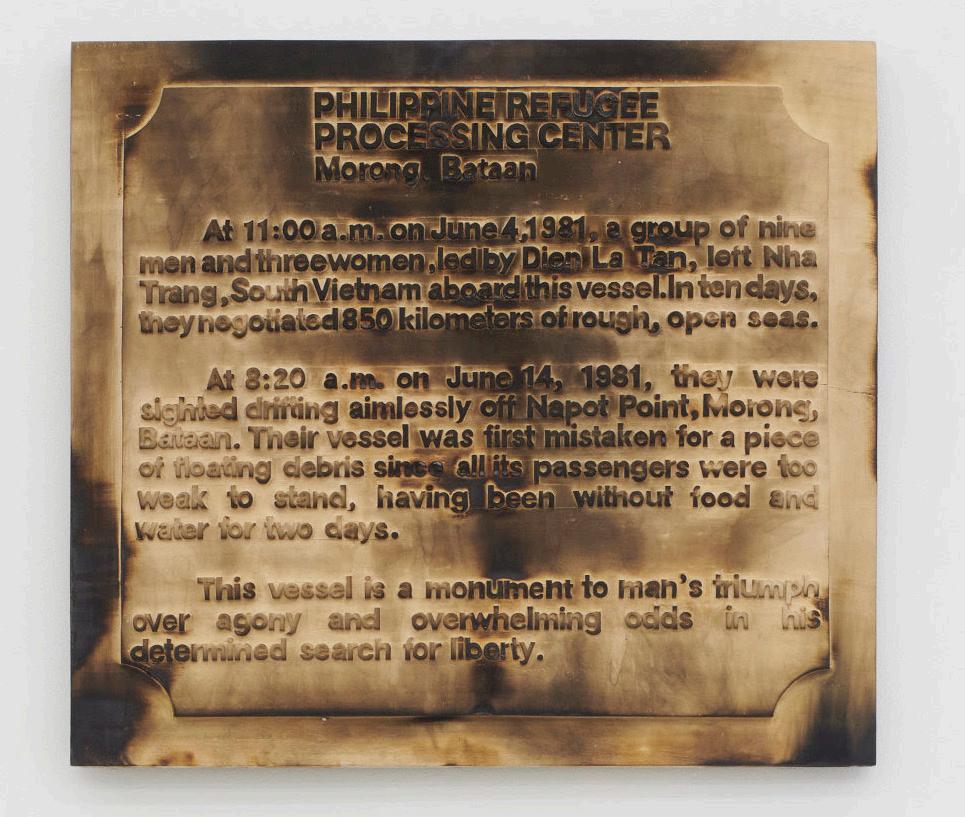

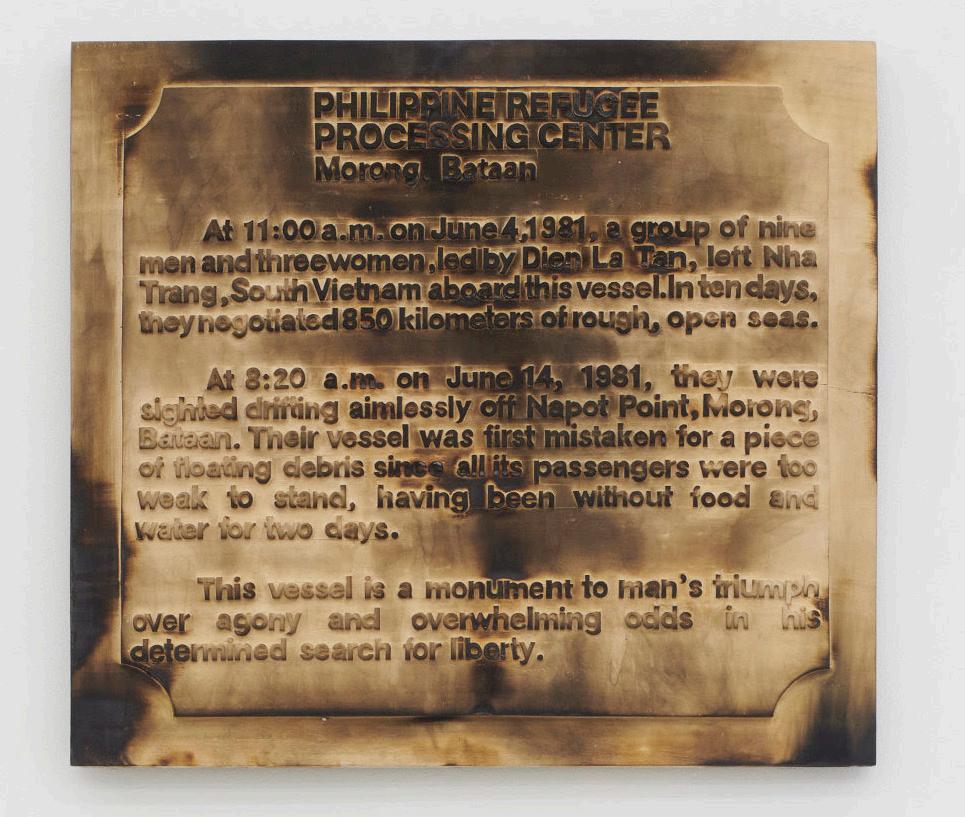

This is a replica of a memorial plaque from the former Philippine Refugee Processing Center (PRPC), which commemorates the perilous journey of nine men and three women who fled Vietnam by boat in 1981. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that between 200,000 and 400,000 boat people died at sea. Other estimates put the number of fatalities closer to 700,000.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Memorial to a Piece of Floating Debris, 2019, hand-carved gmelina wood

Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan New York

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Mile 00 Everywhere OR Replica of Bataan Death March Marker Mile 00, 2019, hand-carved gmelina wood

Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan New York

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Memorial to a Piece of Floating Debris, 2019, hand-carved gmelina wood

Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan New York

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Mile 00 Everywhere OR Replica of Bataan Death March Marker Mile 00, 2019, hand-carved gmelina wood

Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan New York

42

Enemy’s Enemy: Monument to a Monument transforms a classic American Louisville Slugger baseball bat into a meditation on the unifying and divisive powers of religion and sport. The figure carved into the bat is a memorial to Thích Quảng Đức, a Buddhist monk who in 1963 performed self-immolation in protest against the repression of the Buddhist community by the South Vietnamese government. The act of selfsacrifice was widely televised and formed part of the mounting pressure on the Diệm government that led to its deposition later in the year. In addition, the commemorative monument, installed in a reunited Vietnam, appears highly incongruous given the communist state ideology’s antipathy toward religion. This work illustrates how popular sports and organized religions can stir community loyalties, engendering solidarity and instigating conflict. Layered over the work’s reference to a specific moment in Vietnamese history is an allusion to the Vietnam War as a whole, and to the US support that the South Vietnamese received during that conflict. The patented bat is manufactured by Hillerich & Bradsby, a company that in the 1940s produced rifle stocks for the US Army as part of the war effort. Yet the figure of the bodhisattva emanates serenity and acquiescence.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Enemy’s Enemy: A Monument to a Monument, 2009, carved wooden baseball bats [Louisville Slugger, Northern White Ash], chromed metal base plate Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan New York

43

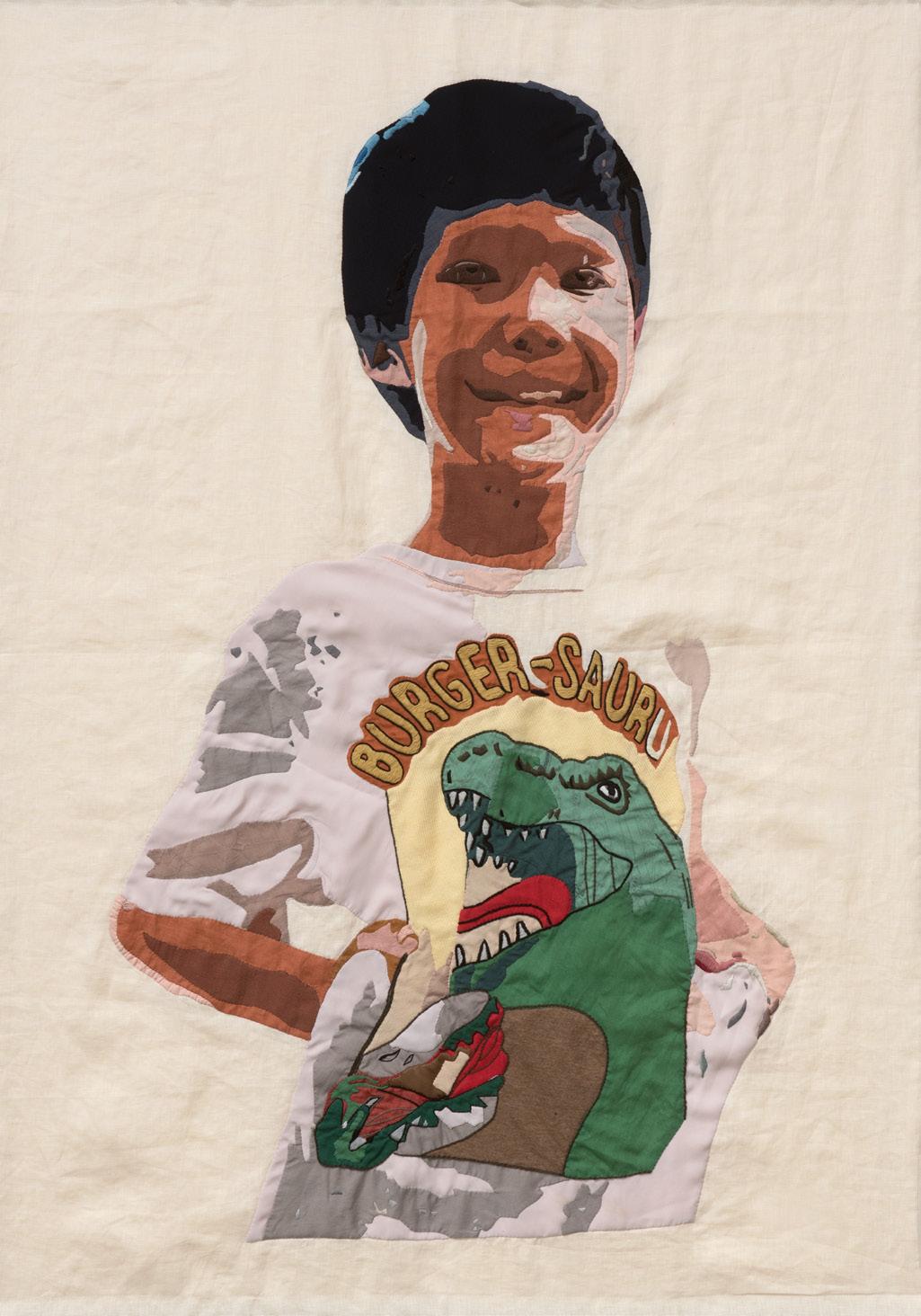

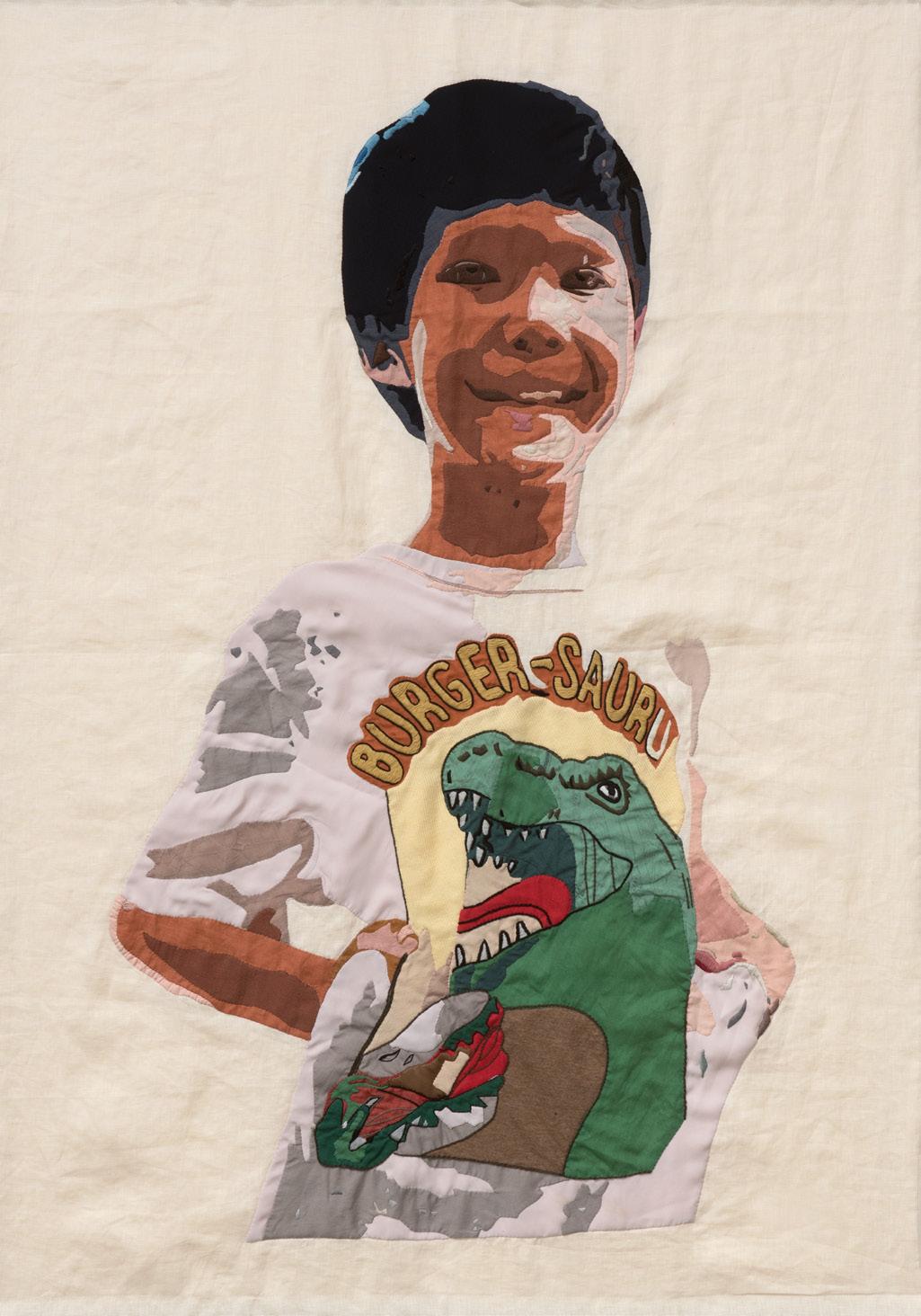

Võ Trân Châu

Adapting found photographs from two distinct periods, French colonialism in Vietnam and the present day, Ho Chi Minh City-based artist Võ Trân Châu chronicles the evolution of portrait and fashion photography. If clothing was once made for utilitarian purposes, now it is the aesthetic value that is more important. And if photography was once an invention that only people with power and authority could afford, now it is democratized to the point of overabundance. For Võ Trân Châu, who was born to a family of traditional embroiderers, the act of threading together her hand-quilted and embroidered textiles is akin to a reconstruction of the stories lost in grand narratives.

Võ Trân Châu, An Interpreter, 2021, hand-quilted found fabric and embroidery on linen Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Quynh

44

Võ Trân Châu, A Coppersmith, 2021, hand-quilted found fabric and embroidery on linen Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Quynh

Võ Trân Châu, A Tirailleur, 2021, hand-quilted found fabric and embroidery on linen Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Quynh

45

Võ Trân Châu, A Teacher, 2022, hand-quilted found fabric and embroidery on linen Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Quynh

46

Võ Trân Châu, A Little Girl, 2022, hand-quilted found fabric and embroidery on linen Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Quynh

Võ Trân Châu, A Boy, 2022, hand-quilted found fabric and embroidery on linen Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Quynh

47

Les Bird

In 1975, after the end of the war in Vietnam, millions of people fled the country. Many did so by the only means available to them—the sea. Between 1976 and 1989, Hong Kong Marine Commander Les Bird’s main duty was to patrol the South China Sea in search of those attempting to reach Hong Kong and seek refugee status. While over 210,000 were successful, many others failed and were lost at sea. During this time, Bird carried a Polaroid Model 210 Pack Film Land Camera in his kitbag. In the 1980s, Bird acquired his own cameras, a Pentax ME Super 35mm SLR and a Nikon FE with the Vivitar 80-200mm f4.5 zoom lens. When circumstances permitted, he would take photographs of his work and the people and vessels he intercepted at sea. Later, he took photographs inside the refugee camps in Hong Kong.

Shown here is a typical example of the type of craft that was arriving in Hong Kong in the early 1980s, overloaded with people and floating low in the water. Vessels such as these were not designed for passage on the open waters and could easily capsize and sink when faced with heavy storms at sea.

Les Bird, Arriving in Hong Kong Waters, 1982 Courtesy of the artist

Les Bird, Arriving in Hong Kong Waters, 1982 Courtesy of the artist

48

Les Bird, A Shot of the Stern of the Panama-Registered Ship the Huey Fong, January 1979 Courtesy of the artist

This photograph was taken from a Marine patrol launch that was moored alongside the Huey Fong. Two young girls look out of a porthole at the camera; a bamboo pole prevents them from falling out. Most of the 3,600 people on this ship had been housed in the cargo hold below the decks. The only fresh air they could get was from these portholes.

Les Bird, Nighttime Rescue, West of Hong Kong, 1983 Courtesy of the artist

Here, clustered together on the deck of a Marine patrol shortly after being rescued from their sinking wooden boat, more than 100 people sit, exhausted from the ordeal, many still in shock from what just happened. The Marine patrol crew managed to locate the vessel on their radar scanner and rescue most of the people from the sinking vessel before it went under. The crew also rescued those who jumped or were thrown into the sea as their boat capsized.

49

Les Bird, A Father’s Fear for the Safety of His Family, Tai Ah Chau Island Camp, 1989 Courtesy of the artist

The father of the family shown here built a cage-like structure to house his family. He found some wire mesh that washed up on a beach on the north side of the island and, together with bamboo sticks, constructed this pen. With no segregation on the island, many families were worried about the large number of young, single male refugees, particularly during the hours of darkness as there was no form of lighting on the island.

Les Bird, Behind the Wire, Stonecutter’s Island Camp, 1989 Courtesy of the artist

In this photograph, children, each with their Hong Kong government-provided plastic cups, line up for their daily issue of rice. In the heat, some cover their heads to protect themselves from the sun’s burning rays. In recent years, Bird has made contact with some of the refugees who came through Hong Kong; one of them sent him a photograph of his yellow plastic cup. He was a child back then and kept the cup after being relocated with his family to the United States. He told Bird that he still uses the cup today.

50

Les Bird, Junk Under Full Sail, South of Hong Kong, 1984

Courtesy of the artist

It was quite unusual for sturdy vessels to arrive from Vietnam, but the one in this photograph was an exception, carrying just twenty-three people, all from one family. The master of the vessel had sailed this wooden craft across the South China Sea in just five days. Everyone on board was in good health.

51

Les Bird, Upper Deck Accommodation, Stonecutter’s Island Camp, 1989 Courtesy

In 1989, there were over 60,000 Vietnamese people in Hong Kong awaiting resettlement overseas. Accommodations were running out. One initiative was to moor six converted public ferries alongside an island in Victoria Harbour. All seats were removed from the ferries in order to provide more deck space.

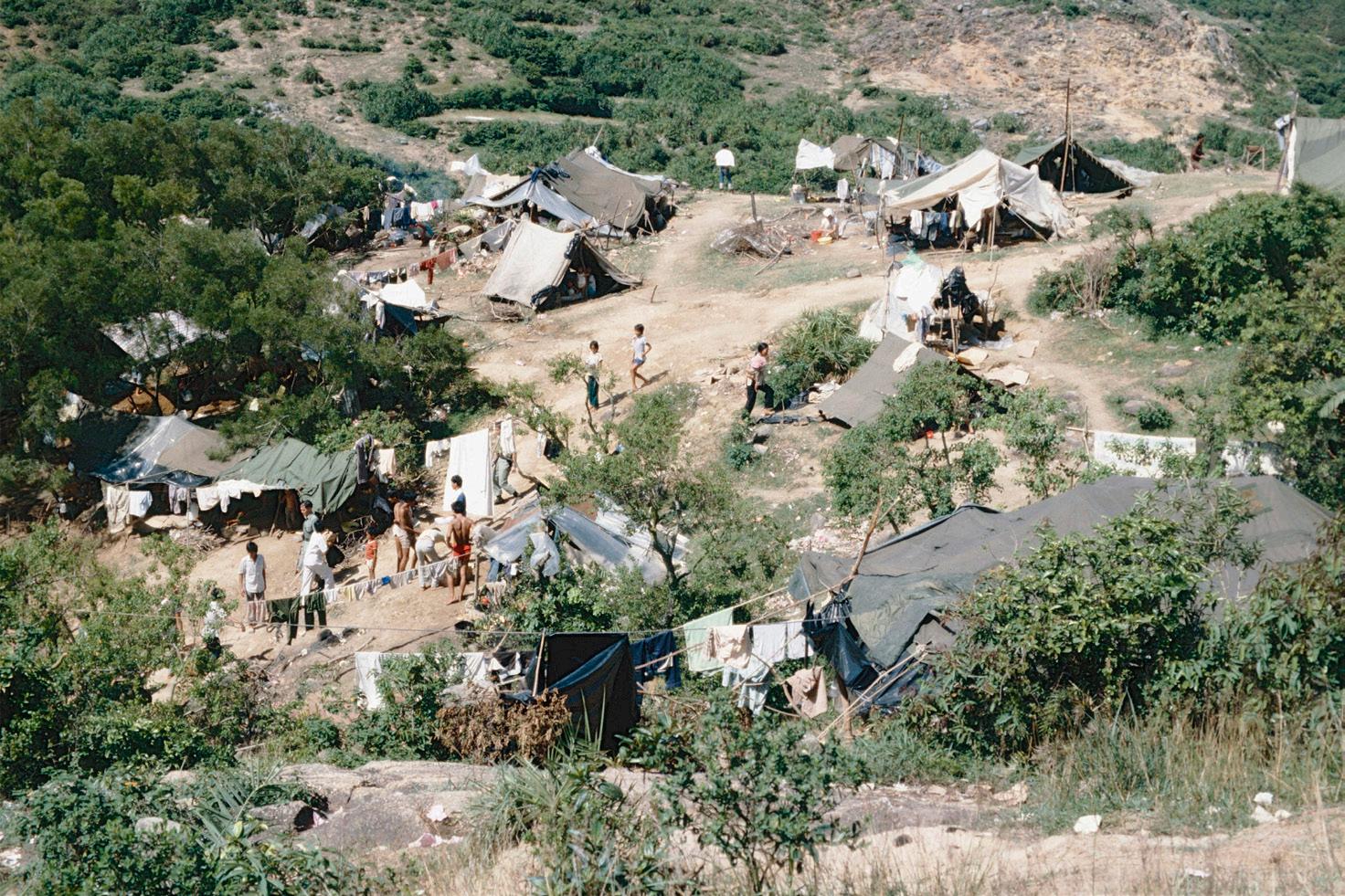

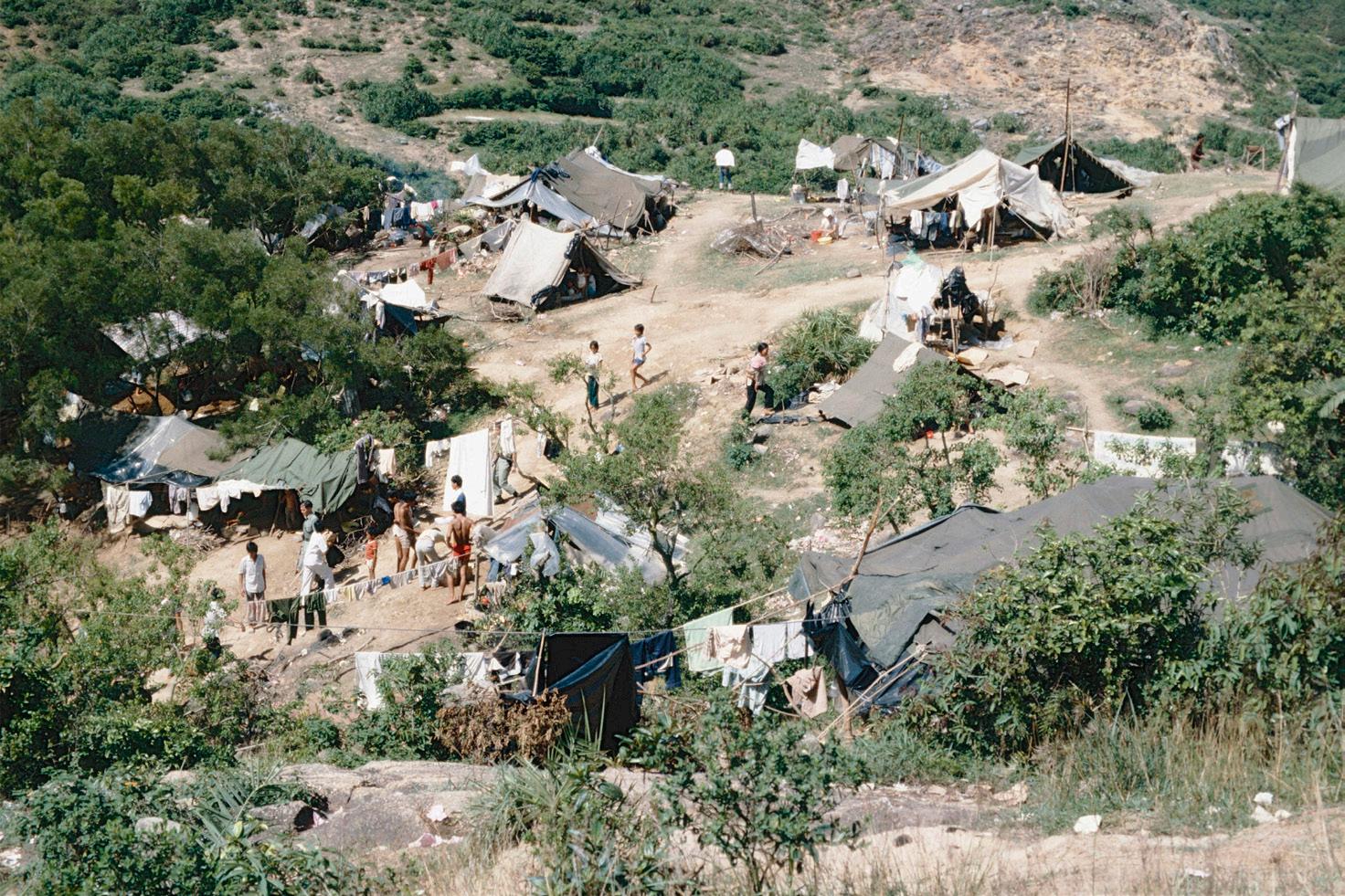

Les Bird, Tent City, Tai Ah Chau Island Camp, 1989

After approximately 3,000 Vietnamese refugees had been relocated to this deserted island, the government provided large military “ten man” tents for accommodations. The refugees erected tents all over the island and some form of an organized community began to take shape.

of the artist

Courtesy of the artist

of the artist

Courtesy of the artist

52

Les Bird, Three Generations, 1980 Courtesy of the artist

This photograph was taken from the upper deck of a patrol launch after finding the small motorized wooden vessel, with ten people on board, in the waters west of Hong Kong. A grandfather can be seen with his two grandchildren, while the men await instructions from the marine patrol crew.

Les Bird, An Entire Family Covered 1,000 Miles of Ocean on a Flimsy River Boat, 1980 Courtesy of the artist

One family of three generations was on the converted motorized river boat shown here. The low vessel was not designed to cross the open ocean and would have easily capsized during a 1,000-mile ocean voyage in rough conditions. This family had utilized raffia mats to form a roof on the boat to protect themselves from the burning sun. They also had utensils and a small paraffin stove to cook the fish they caught on their journey from Vietnam.

53

Sandy Northrup

Sandy Northrop, Vietnam: The Next Generation, 2005, documentary, 53:48 minutes Courtesy of the artist

In 1997, Sandy Northrop moved to Hanoi with her husband, Los Angeles Times correspondent David Lamb. That year, she began making Assignment Hanoi, her first of three documentaries about Vietnam, telling the story of Pete Peterson who had survived six years as a prisoner of war in Hanoi and returned to Vietnam as the United States’ first ambassador since 1975. Her second program, Vietnam Passage: Journeys from War to Peace, highlighted the Vietnamese perspective on the war and its aftermath. Vietnam: The Next Generation is the final film in what has become a trilogy on modern Vietnam. It profiles the lives of seven young Vietnamese, revealing the challenges, choices, and dreams that shape their lives and that of their generation, while the doors of a free-market economy were opening and memories of the war were being relegated to the distant past.

54

Tommy Bui

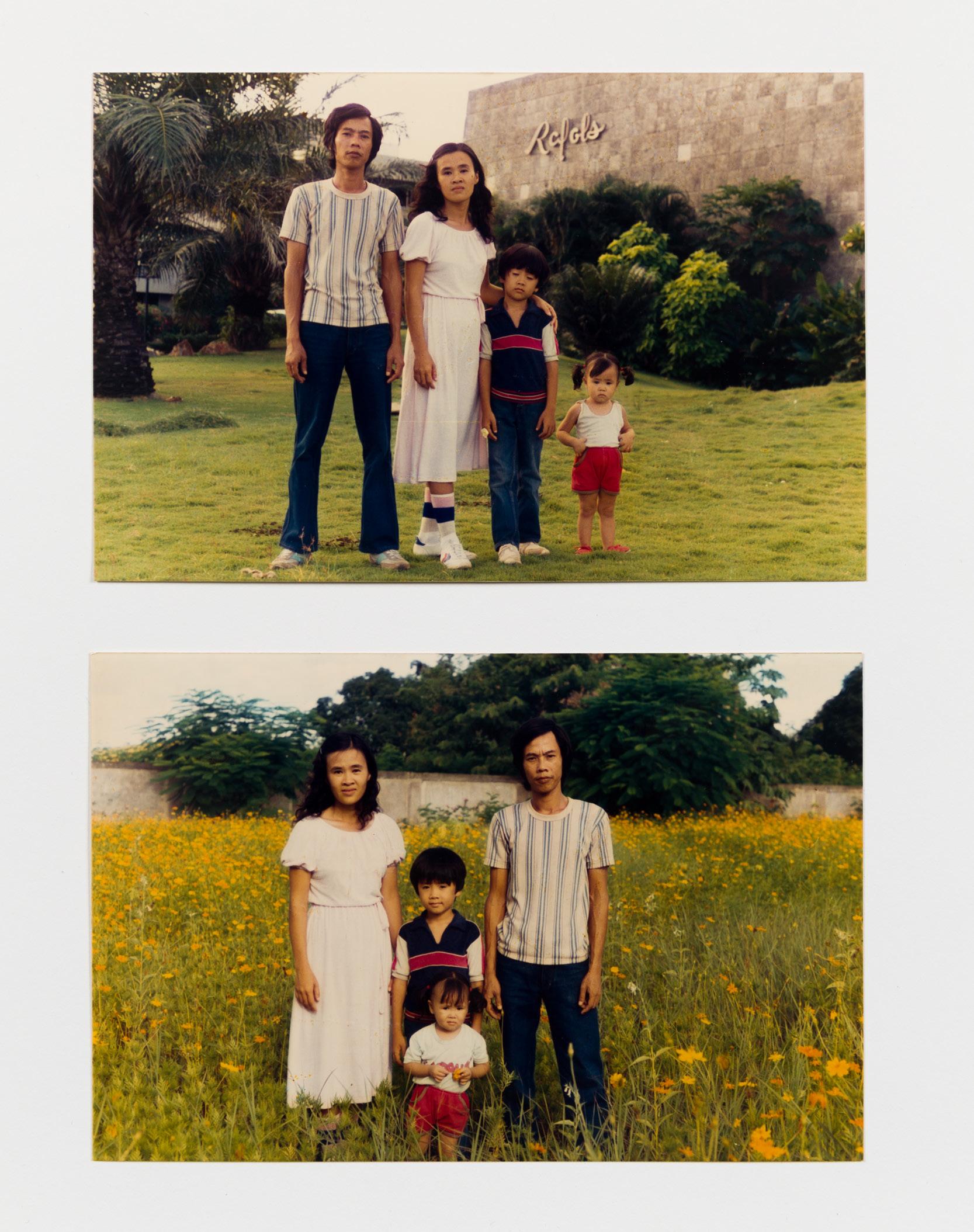

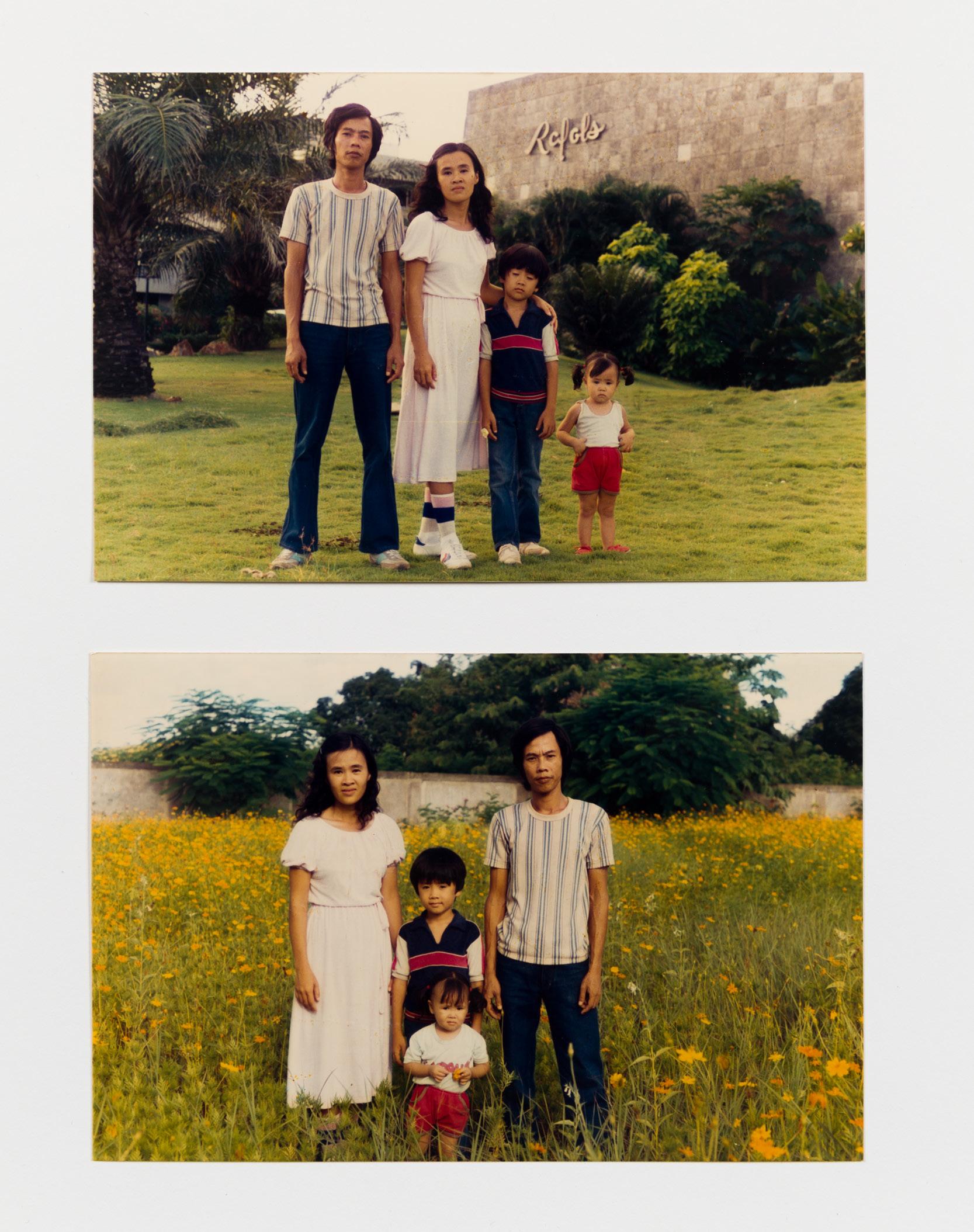

Two Family Portraits, 1984

Courtesy of Tommy Vinh Bui

“When my parents arrived at the Philippine Refugee Processing Center (PRPC), they urgently needed to send word to their families back in Vietnam that they had arrived safety. Photographers could be hired in the refugee camp and these proof of life photos would be sent, allaying fears that they had perished at sea. These are the few photographs I have of my parents from this era, and it’s oddly startling to recognize them as youthful and bright-eyed and full of optimism for the future.” —Tommy Bui

55

Sewing Box, 1989, needles, thimbles, pincushions, seam rippers, scissors, bobbins, measurement tape Courtesy of Tommy Vinh Bui

“My mother is from the historically significant trading port Hội An on the central coast of Vietnam. Because of its auspicious location along the Silk Road, it became renowned for their talented tailors and brilliant textiles. Skills passed down from generation to generation. When my mother first immigrated here, due to the language barrier and challenges of initial culture shock, she relied on the tried-and-true familiarity of mending clothes for hire. This little box of pincushions, thimbles, and bobbins provided a living for my family during those early days of assimilation.” —Tommy

Bui

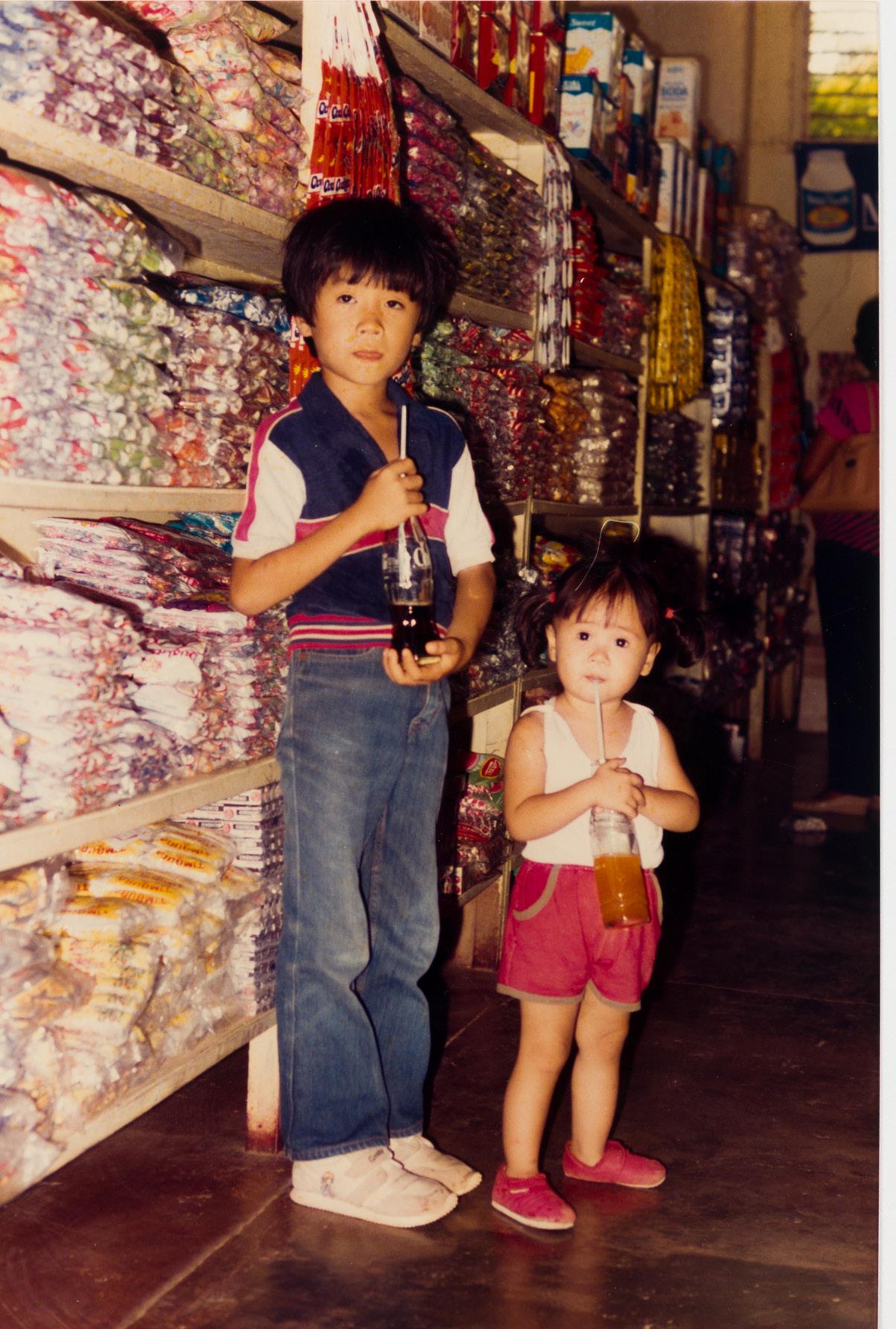

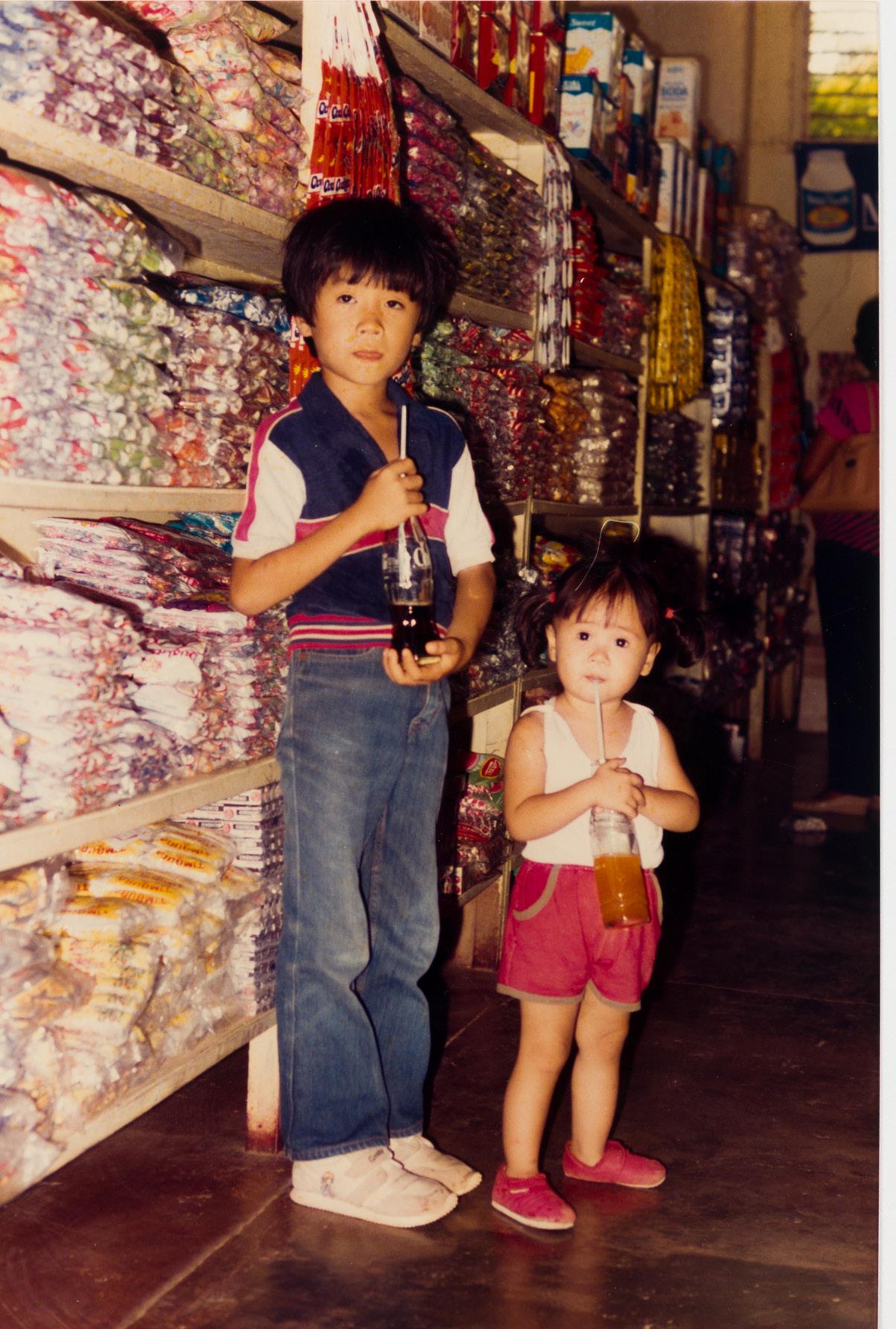

Siblings, 1984 Courtesy of Tommy Vinh Bui

“These are my older siblings in a shoppe in the refugee camp. Imbibing and surrounded by, what to them, must’ve felt like a windfall of confections and newfound abundance. Which must have been a stark contrast to the several weeks rationing water and food and bobbing languidly in unkind seas. My sister has hazy memories of the perilous journey. But my brother was old enough to lug along nostalgia for his far-flung homeland.” —Tommy

Bui

Bui

56

Three Identification Cards, 1984

“These were issued to my family upon arrival in the Philippines. My sister had to be hefted up for her mugshot-like portrait. What made their seaward journey all the more harrowing was that my mother, despite living in a coastal community, never learned how to swim. And they had to flee under the cloak of night. My sister was placed into this buoyant wicker basket thing and trawled along out to the ship moored several meters from the shore. And a human chain of people hauling along the women and children who couldn’t swim or navigate between the moonless night and obsidian sea.”

—Tommy Bui

—Tommy Bui

School Card, 1968

Courtesy of Tommy Vinh Bui

“This was my mother’s school identification card. Another remnant of a bygone past. And one of the few fragments of memories she was able to smuggle aboard and away with her to new far-flung western horizons.”

—Tommy Bui

57

Courtesy of Tommy Vinh Bui

Quoc Tran

Quoc Tran, April 30, 1975, Saigon, Viet-Nam, Witnessing. Ending. And Beginning., 2014, oil on canvas

Courtesy of the artist

“Early morning on April 30, 1975, I witnessed the last US helicopter flight out of Saigon. That flight marked the end of the Viet-Nam conflict, and the beginning of the redefinition, redemption and reclamation of the new Viet-Nam. This painting was my attempt to capture the complexity of that historic moment.” —Quoc Tran, artist and Superintendent of the Culver City Unified School District

58

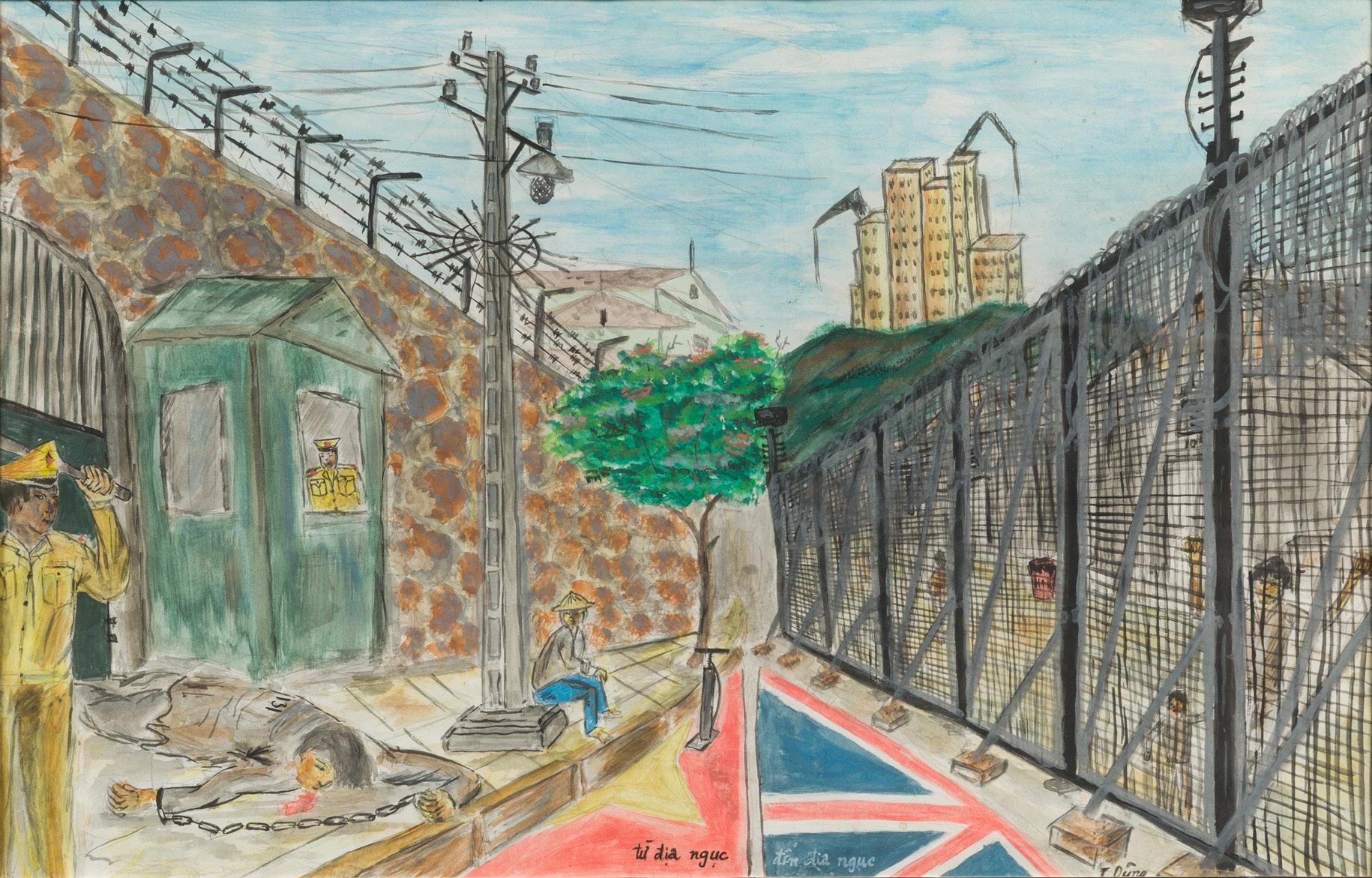

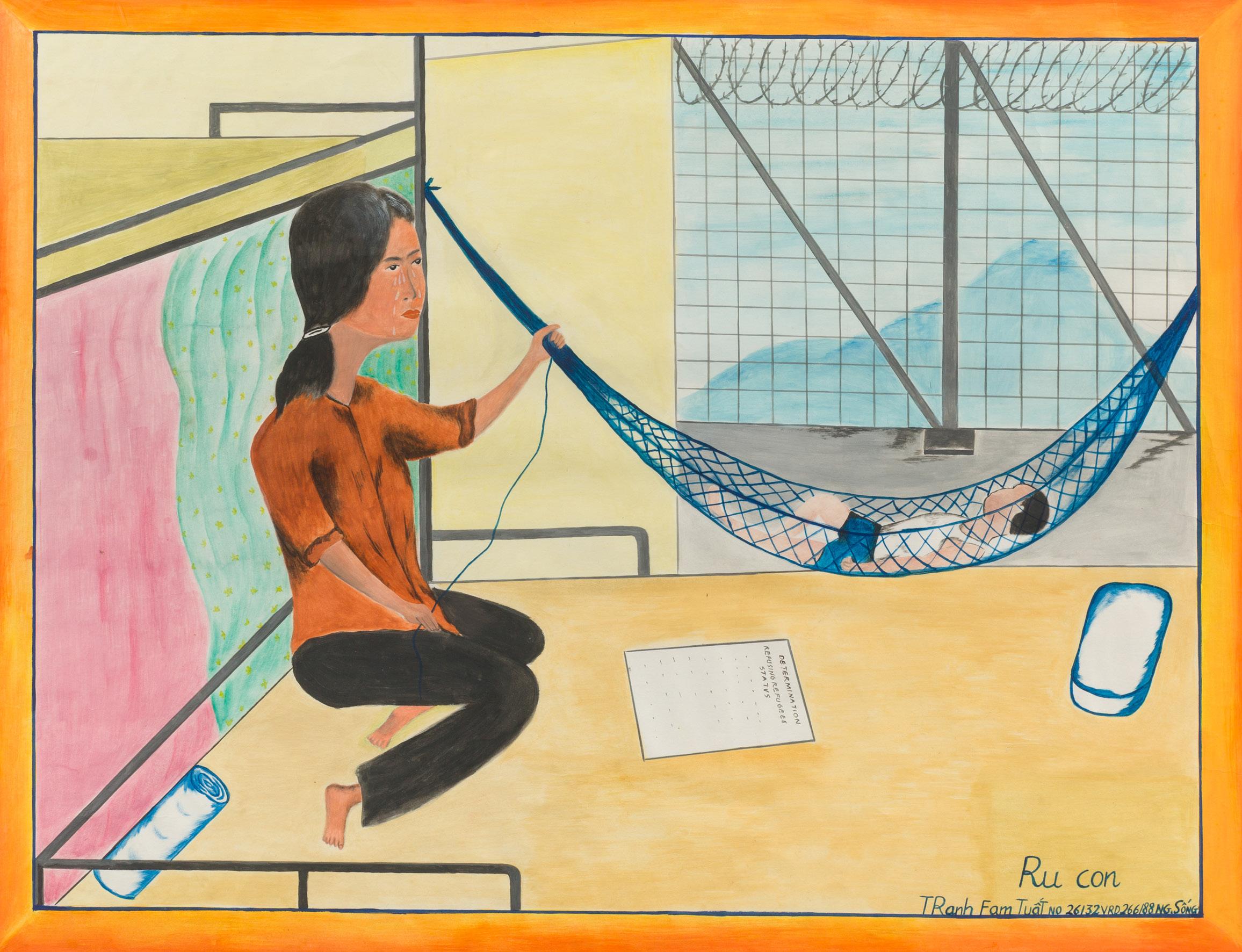

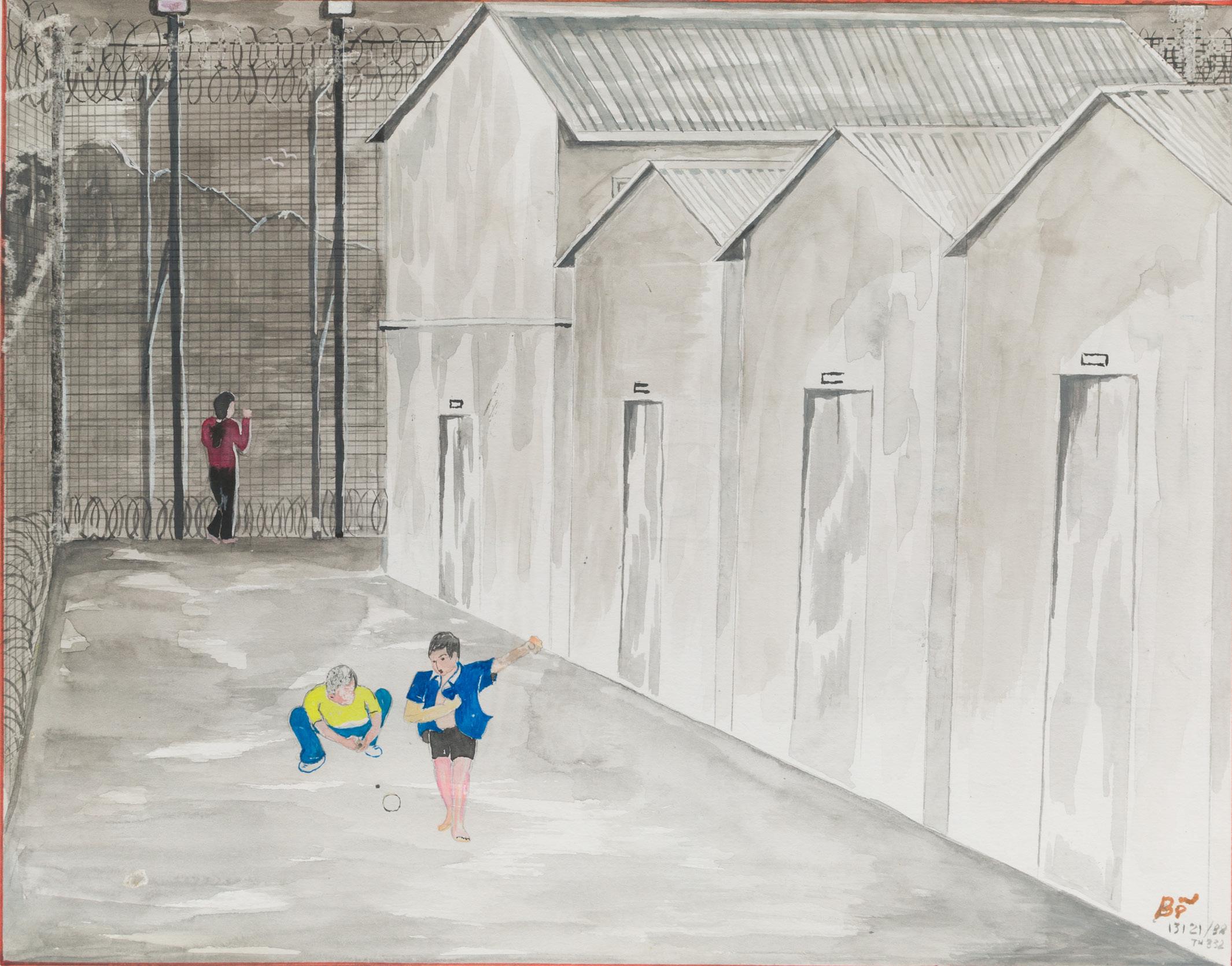

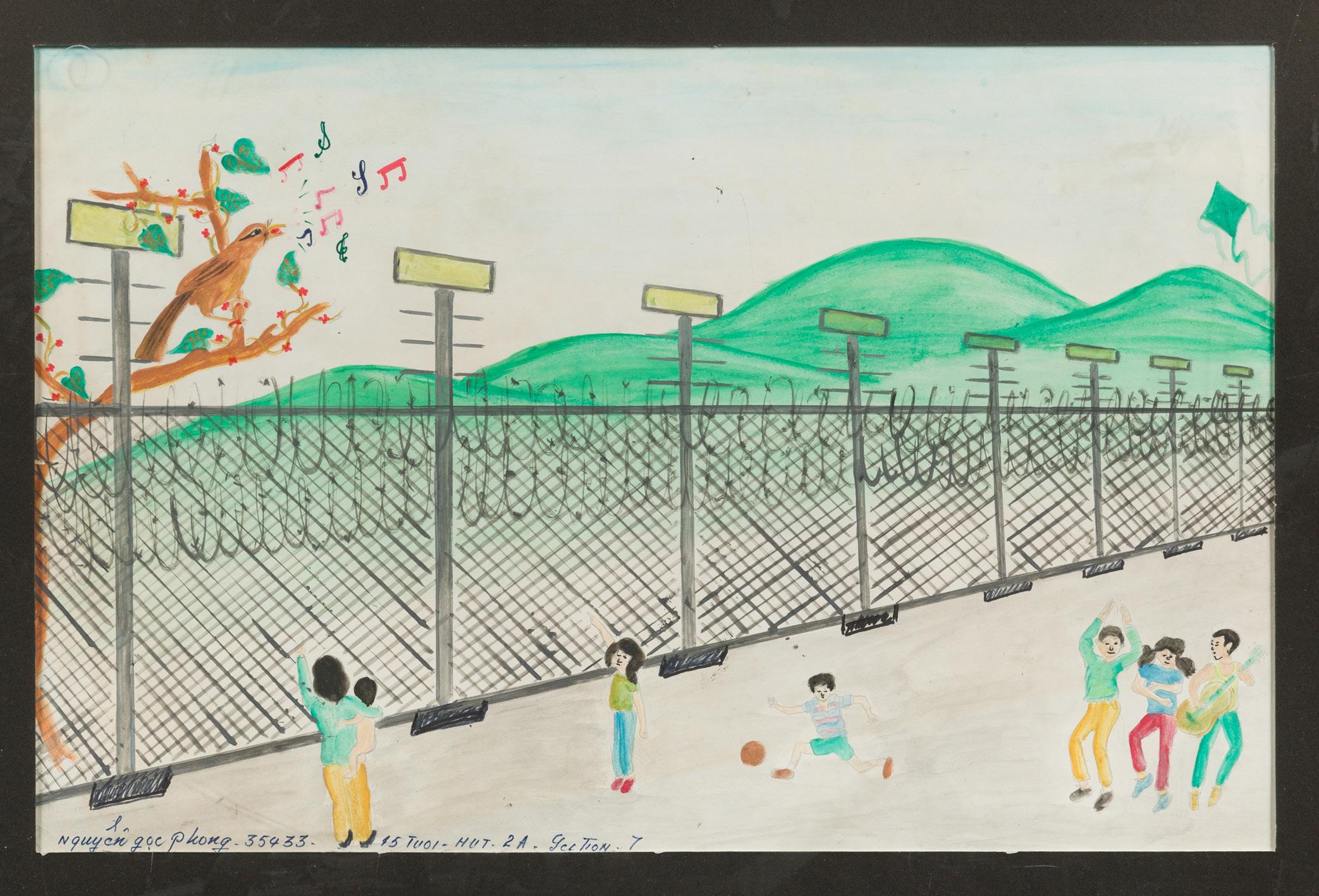

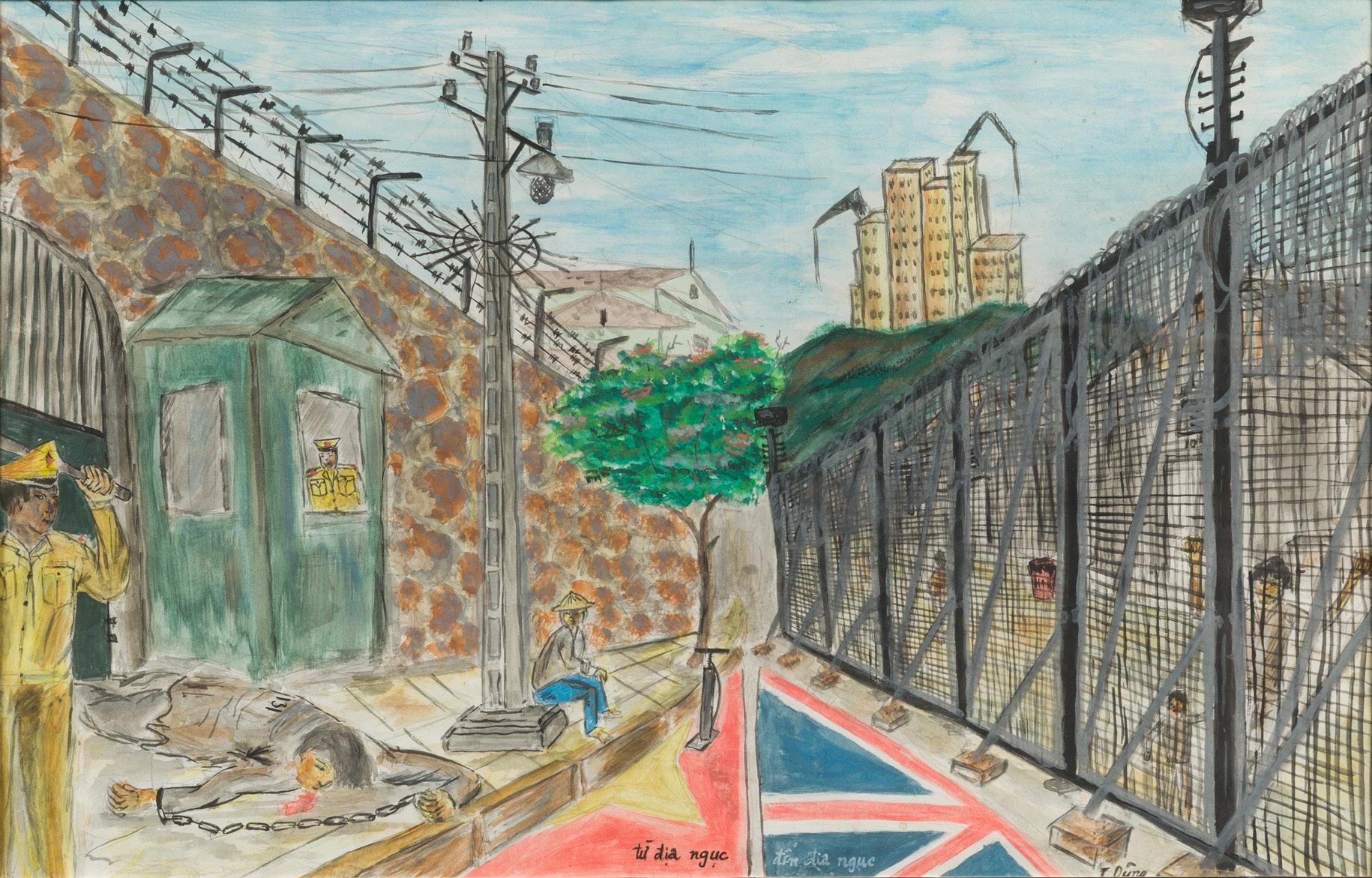

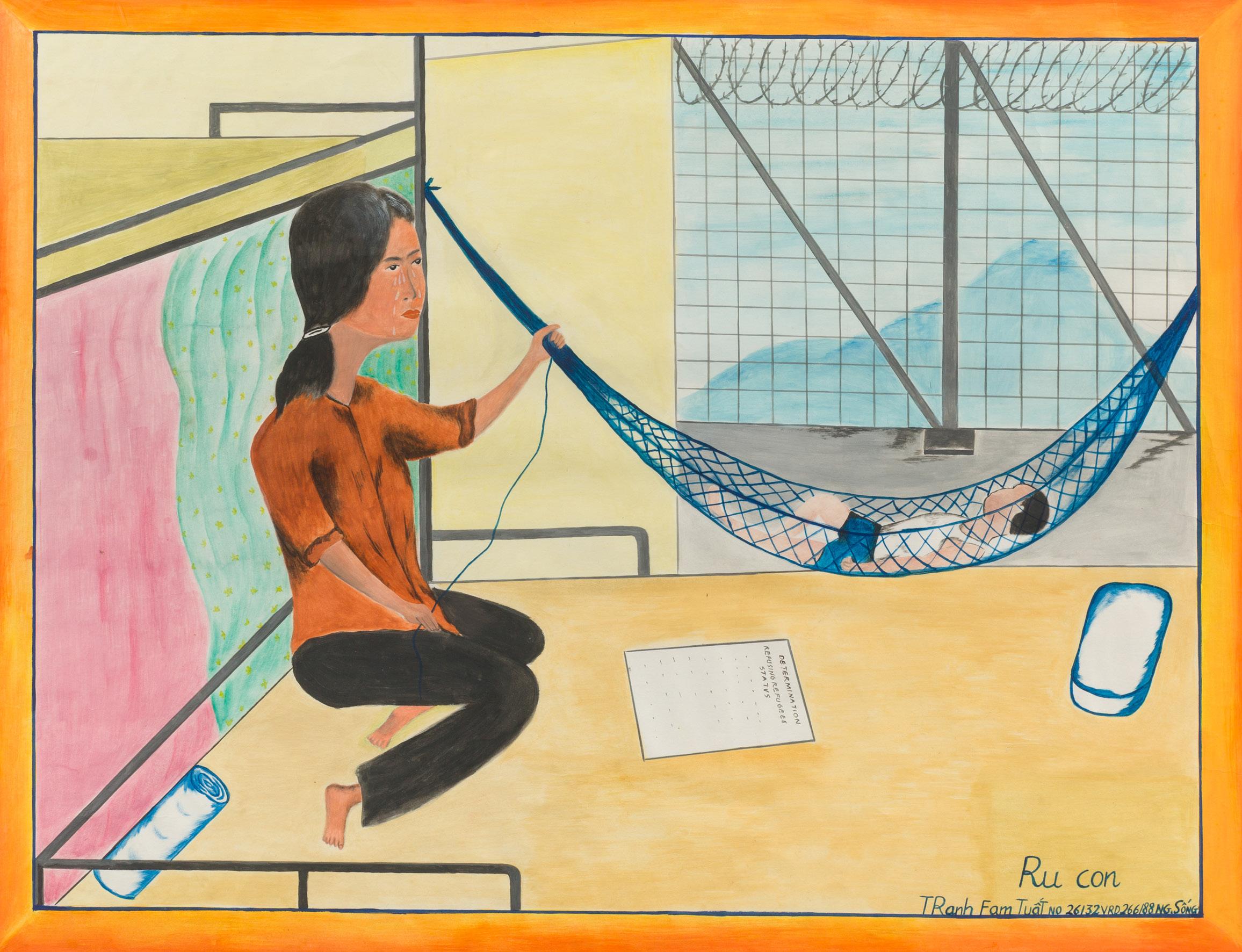

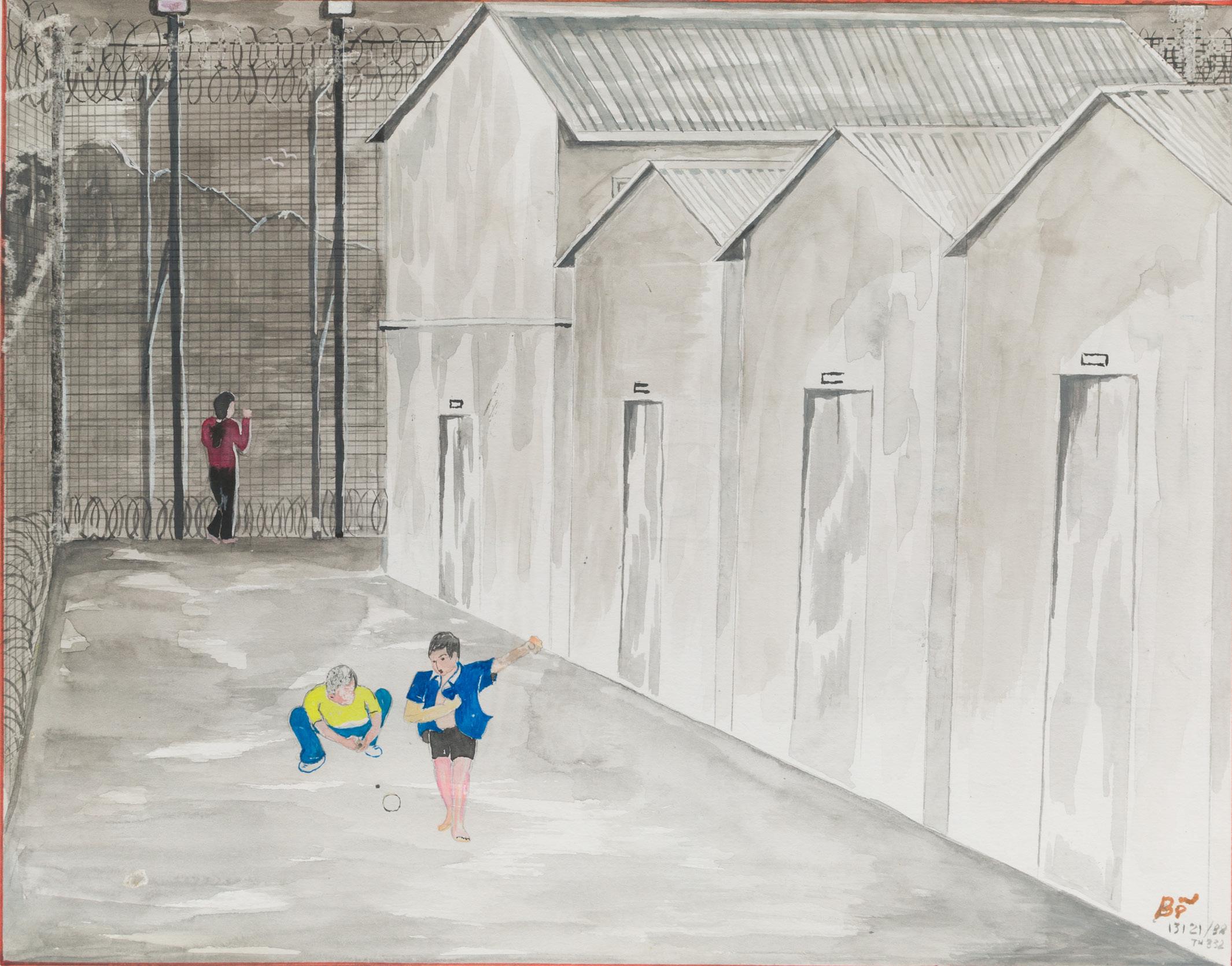

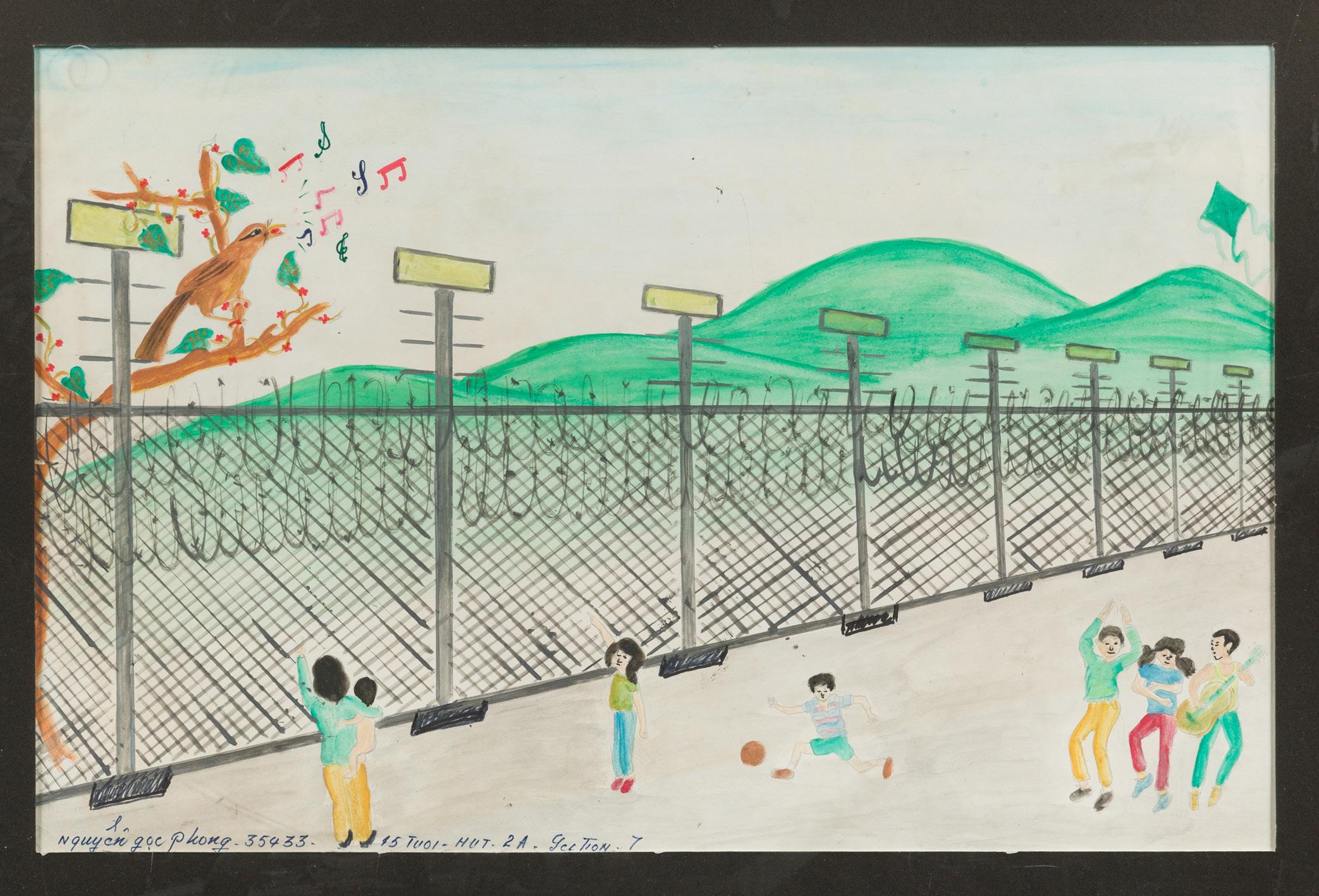

Art in the Camps

Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

In the late 1980s, more than 200,000 Vietnamese refugees were being held in detention camps in Hong Kong, after crossing the sea by boat from Vietnam. These people lived in a bleak, prison-like environment. From the 1980s, Hong Kong society became gradually more impatient with the refugee waves, renaming the Vietnamese as “boat people” instead of “refugees.” In 1988, artist, art educator, and community art facilitator Eveylna Liang founded the three-year art program Art in the Camps, funded by the United Nations, which was facilitated in these detention camps from 1988–1991, providing a platform for the inmates to express themselves.

“N,” Untitled, 1988–1991, watercolor on paper

Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

Dung, Untitled, 1988–1991, watercolor on paper

Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

59

Unknown Artist, Untitled, 1988, watercolor on paper

Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

D.Q.H., Untitled, 1988–1991, watercolor on paper

Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

60

61

D.Q.H., Untitled, 1988–1991, acrylic on paper Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

Le Khac Dat, Untitled, 1988–1991, acrylic on paper Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

Vu Ding Bang, Where is Freedom, 1989, acrylic on paper

Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

62

D.Q.H., Untitled, 1988–1991, acrylic on paper

Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong

Library and Art in the Camps

Trinh Do, A Stabbed Class, 1988, acrylic on paper

Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong

Library and Art in the Camps

63

NG DAP, Untitled, 1988–1991, acrylic on paper Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

NG DAP, Untitled, 1988–1991, acrylic on paper Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

64

Nguyen Goc Phong, Untitled, 1988, color pencils on paper Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

65

Unknown Artist, Untitled, 1988–1991 Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

Dung, Untitled, 1988–1991, watercolor on paper Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

Unknown Artist, Untitled, 1990, acrylic on paper Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

66

OANHB, The Exodus from Vietnam, 1988–1991, Vietnamese Embroidery Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

67

The Process of Women Weaving Artwork Inside the Detention Camp with Art in the Camps, 1988-1989

Photo courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

Thue Vu, Untitled, 1988–1991, acrylic on paper Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

68

The Wende Museum || 10808 Culver Blvd. || T: (310) 216-1600 || wendemuseum.org WENDE MUSEUM

Dinh Q. Lê, Night Vision, 2008, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Dinh Q. Lê, Night Vision, 2008, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled 3, 2004, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled 3, 2004, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled (The Persistence of Memory), 2000–01, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Dinh Q. Lê, Untitled (The Persistence of Memory), 2000–01, c-print and linen tape Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Memorial to a Piece of Floating Debris, 2019, hand-carved gmelina wood

Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan New York

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Mile 00 Everywhere OR Replica of Bataan Death March Marker Mile 00, 2019, hand-carved gmelina wood

Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan New York

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Memorial to a Piece of Floating Debris, 2019, hand-carved gmelina wood

Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan New York

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Mile 00 Everywhere OR Replica of Bataan Death March Marker Mile 00, 2019, hand-carved gmelina wood

Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan New York

Les Bird, Arriving in Hong Kong Waters, 1982 Courtesy of the artist

Les Bird, Arriving in Hong Kong Waters, 1982 Courtesy of the artist

of the artist

Courtesy of the artist

of the artist

Courtesy of the artist

Bui

Bui

—Tommy Bui

—Tommy Bui

NG DAP, Untitled, 1988–1991, acrylic on paper Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps

NG DAP, Untitled, 1988–1991, acrylic on paper Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library and Art in the Camps