Omnino

Omnino is a peer-reviewed, scholarly research journal for the undergraduate students and academic community of Valdosta State University. Omnino publishes original research from VSU students in all disciplines, bringing student scholarship to a wider academic audience. Undergraduates from every discipline are encouraged to submit their work; papers from upper level courses are suggested.

The word “Omnino” is Latin for “altogether.” Omnino stands for the journal’s main mission to bring together all disciplines of academia to form a well-rounded and comprehensive research journal.

ISSN: 2472-3223 (Print), 2472-3231 (Online)

Isabella Schneider

Carissa Zaun Student Editors

Sam Acevedo Sydney Bergquist Angel Davis

Laura Northup Kasmira Smith Graphic Designer Kwame Akuoko

Faculty Advisor Dr. Anne Greenfield

Copyright © 2022 by Valdosta State University

2021 California Recall Election: What Are the Key Predictors of the Recall Vote of Governor Gavin Newsom across the Counties of California?

By Jacob C. Ryan

Faculty Mentor: Dr. James LaPlant, Department of Political Science ........................................................................................................................7

The Seminole Wars of the 19th Century: A Look into the Causes of One of the Longest Military Conflicts in American History

By B. Cordell Moats

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Lavonna Lovern, Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies

Giving a Voice to the Voiceless

By Kasmira K. Smith

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Pat Miller, Department of English

Native American Property Loss and the United States’ Law

By Maya Commodore

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Lavonna Lovern, Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies ......................................................................................................................58

The Consequences of Education: Liminality and Othering in the Life of Zitkala-Sa

By Laura Northup

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Deborah Hall, Department of English

The Mummy: An Analysis of Egyptomania and How Ancient Egypt Is Portrayed in The Mummy Franchise

By Cassidy Weaver

Faculty Mentor: Melanie S. Byrd, Department of History

By Sydney Bergquist

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Marty Williams, Department of English ....................................................................................................................110

By Rhonda Reliford

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Cristobal Serran-Pagan, Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies ....................................................................................................................124

Exploring Predictors of College Graduation Rates at Colleges and Universities Across Georgia

By Tia Brown

Faculty Mentor: Dr. James LaPlant, Department of Political Science ....................................................................................................................148

“Be something more than man or woman. Be Tandy”: Resisting and Redefining Gender in Winesburg, Ohio

By Georgia Wynn

Faculty Mentor: Dr. Adam Wood, Department of English ....................................................................................................................166

The purpose of this quantitative study is to examine the key predictors of the “yes” vote to recall California Governor Gavin Newsom. This study evaluates the factors that led to the unusual event of a recall election in the middle of the Governor’s elected term by reviewing data across the 58 counties of California. The study analyzed seven independent variables: percentage of the African American population, percentage of the Latino population, county unemployment rates, percent of the population who have a college degree, percent of the vote for Trump in the 2020 presidential election, population density per capita, and the number of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people. The impact of these variables on the dependent variable, the percentage yes votes to recall Governor Newsom, is determined through correlation analysis, scatterplots, and multivariate regression analysis. Three of the seven variables proved to be highly significant. The percent of the vote for Trump in 2020 and the percent of those with a college degree per county were found to be highly significant at p<.01. Interestingly, population density and the number of COVID-19 cases were found significant at the bivariate level but washed out in the multivariate analysis. The African American population and unemployment rate variables had minimal influence on the recall election. While not significant

at the bivariate level, the Latino population variable was found significant in the multivariate model. The variable was found to have a negative relationship with the dependent variable. Newsom’s recall election was a significant and unusual political event that he will carry with him into his 2022 reelection campaign. The 2021 recall election of the state of California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, is one that served as a bellwether for the future of United States politics. California is our most populous state and is one that has become increasingly Democratic over the past decades. The political convulsion that would have occurred if a Republican candidate had been elected to replace Governor Newsom would have been astounding. The nature in which this election was conducted in the middle of Newsom’s elected term was an attempt to unseat the Democratic governor. This occurrence would not normally occur outside of regular election cycles. The unprecedented circumstances of the past two years due to the COVID-19 pandemic have caused major shifts in how the different sides of the aisle see fit for the government to be conducted. In a survey, Californians claimed COVID-19 was the top issue within their state (Baldassare et al. 2021b).

The main question being asked is “What are the key factors that would predict a vote to recall Governor Newsom across the counties of California?” The rate of unemployment was weaponized by both parties to cite reasons for or against the election. Newsom claimed in July that California had added 114,000 new jobs. However, the California GOP argued that the California unemployment rate accounted for 21.4 percent of the entire nation while only representing 11.7 percent of the entire workforce (Hoeven 2021). With California electing Joe Biden by 28 percentage points, the vote for Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election is a key indicator of the likelihood of voters to recall Newsom.

The purpose of this quantitative study is to investigate the key predictors of the recall vote of Governor Gavin Newsom. Specific studies on a variety of predictors have been conducted. However, the overall rarity of recall elections makes the predicting factors more difficult to observe. The last recall election of a California governor occurred in 2003. Some studies evaluate the racial demographic changes that have occurred in the state. Other studies suggest the impact of other sociopolitical predictors that would cause changes in voting outcomes. These studies will be explored in the first section of this study. The second section will explain the data and methods used in this study. This will be followed by the third section including the findings and conclusions on the significance of the study based on correlation, and regression analysis as well as the use of the study for future research.

There are a variety of predictors that could explain how counties vote in the recall election. Studies have been conducted to observe California residents’ relationship with their government. Orrin Heatlie was the first to file the recall petition. Heatlie is a resident of Folsom, which is a city in Sacramento County near the capital. He spent 25 years serving as the Sergeant with the nearby Yolo County Sherriff’s Department (MEET THE BOARD n.d.). The petition claimed that Newsom implemented laws that were detrimental to Californians. This claim went on to mention that Newsom harbored illegal immigrants and took care of them more than his citizens. California had the highest tax rates in the nation, the highest homelessness rates, and the lowest quality of life (Gavin Newsom recall, Governor of California (2019-2021)/Path to the Ballot n.d.). Additionally, proponents stated in the petition their disappointment with Newsom suspending the death penalty as it “overruled the will of the peo-

ple” and their irritation against water rationing due to droughts (Gavin Newsom recall, Governor of California (2019-2021)/ Path to the Ballot n.d.).

Organizers were required to have 1,495,709 signatures to place the election on a special ballot. Signatures had to come from registered voters, and the signatures had to be filed monthly with the secretary of state conducting a signature status report (Gavin Newsom recall, Governor of California (2019-2021)/ Path to the Ballot n.d.). Funding for the campaign mostly came from large committees and groups. While support for the recall had aggregate contributions of $10,994,454, the opposition had over $31,834,189 in funding (Recall Election 2021). The largest amount of funding in support was contributed by the Rescue California Recall group at $955,053 (Recall Election 2021). Other contributors to the election funding included Prov 3:9 LLC, DGB Ranch, Chamath Palihapitiya, etc.

While COVID-19 was claimed to be the top issue in the state, partisanship deeply divided voters. The recall was not initially an effort brought on by COVID-19, but by other policy and ideological differences. However, the recall effort quickly became about COVID-19 restrictions after Newsom was seen dining at one of the most expensive restaurants in the country where the least expensive meal is $350, after advising strict social distancing to Californians (Kang 2021). This added frustration to most who supported the recall with claims that Newsom was out of touch with the restrictions he was enforcing, and this boosted other driving forces behind the election such as opposition to his other progressive policies. Studies have found that political partisanship has influenced citizens’ decisions to voluntarily engage in COVID-based preventative measures in response to communications by their governor during the pandemic (Grossman et al. 2020). Over half of Californians among all regions and demographic groups agreed the state has handled the pandemic well.

However, Democrats and Independent voters are more likely to hold that view than Republicans (Baldassare et al. 2021b).

California has had the ability to recall its governor since 1911. State-level recall attempts have been largely ineffectual with the recall of Gray Davis being the only successful recall out of 32 attempts since 1911 (C. Coleman 2011). The political landscape of California is much different today than it was when Governor Gray Davis was recalled in 2003 (Gray Davis recall, Governor of California (2003), n.d.). The effort was successful to recall Democratic Governor Davis. The recall election occurred on October 7th, 2003, which was 11 months into Davis’ second term. 55 percent of the vote was cast in favor of the recall option. The elected replacement of Davis was Austrian-American actor and public personality, Arnold Schwarzenegger, who served as governor until 2011.

There are now 22 million registered voters in California. The Republican Party only claims 25 percent of the electorate (Ronayne 2021). Democrat Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump capturing 63.5 percent of the statewide vote. This result compares well to the initial election of Governor Newsom in 2018 in which he obtained 62 percent of the vote (Blood 2021). Democratic lawmakers have vigorous support in the state. Republican voters remain somewhat in small margins in the state. However, studies have found that the approval rate of former President Trump was at least 27 points below his disapproval. Thus, Donald Trump remains widely unpopular throughout the state with his approval only representing 3 percent of the population (McGhee 2020). While there are some GOP strongholds in the state, counties that were once suburban strengths for the Republican party are also becoming increasingly Democratic. Orange County is a bellwether for the suburban mood. Traditionally voting conservative, the county was won by Hillary Clinton in 2016. This was attributed to the alignment of young voters to the Democratic party (Goldberg 2020).

The racial demographics are also far more different in California in 2021 compared to the last recall in 2003. Significant increases in minority populations could change the dynamic of the electorate. The Democratic party has added 3 million voters in California since the 2003 recall. An increase in Latino voters from 17.5 percent to 25 percent of voters has occurred (Ronayne 2021). Studies find that most minority populations are more likely to vote for the Democratic party. Overwhelming majorities of African Americans (73%) and most Latinos (58%) are registered as Democrats in California. This is far less than the percentage of registered Republicans in these populations (5% African American and 16% Latino) (Baldassare et al. 2020). Registration among white voters is more equally divided with 40 percent registered as Democrats and 34 percent registered as Republicans. Latinos’ voting power in California is not taken lightly. While studies have found this group has increased support for former Republican President Donald Trump, they are the largest minority group in the state representing 40 percent of the state’s population. Since 1994, Latinos have contributed the largest number of votes from communities of color to winning Democratic candidates. Furthermore, the Latino community tends to support Democratic candidates by a 2-to-1 margin However, Latinos only account for 21 percent of California’s likely voters (Baldassare et al. 2020).

Studies have also found that those who are college educated often have more partisan loyalties than those who are not. Since many are often politically socialized at a young age, the university is the first occurrence of freedom outside of family-introduced socialization units. Educational realignment is a prominent force in developing party affiliation. Thus, educated individuals are well-positioned politically and tend to reasonably fashion and defend their political interests (Joslyn and Haider-Markel 2014). Areas with a high concentration of college graduates such as the Bay Area are typically Democratic strongholds, made up of San Francisco and Marin counties. This

area of the state is also a major urban, metropolitan area. With almost 60 percent of residents over the age of 25 with a college degree, the area holds the highest share of college graduates in the state (Kondik and Coleman 2021). Previously conducted research also found that those with a college degree or some form of higher education represent eight out of ten likely voters (Baldassare et al. 2021a). Orange County is also a heavily populated area that once was a conservative stronghold. With its highly educated, diverse population, the county has increasingly had more partisan competition. Previous studies would suggest that there is somewhat of an urban and rural divide among partisanship in the state (Kondik and Coleman 2021).

There has been significant disagreement on the performance of California’s economy since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. With studies finding almost half of Californians think the state is in an economic recession, Republicans are found more likely to hold that view (Baldassare et al. 2021b). While partisans may disagree on the state of the economy, this does impact their view of Newsom’s job performance. With unemployment claims not budging during the pandemic, 69,000 Californians filed unemployment claims the week of August 14, 2021 (Hoeven 2021). The California Democratic Party, which typically finds more support for extending unemployment benefits, noted the unemployment rate of 7.6% in July 2021 was 5.6 percentage points lower than it was in June 2020 earlier in the pandemic (Hoeven 2021). The chair of the California Republican party has provided counterarguments that the 7.6 percentage of unemployed persons is the second-highest rate in the nation.

Studies have found that unemployment voting behavior tends to fall upon a reward and punishment system (Wright 2012). If the unemployment rate is low, the incumbent party typically enjoys electoral success during times of economic prosperity. However, voters tend to turn against incumbents when unemployment rates are higher in times of economic hardship (McIver 1982). The view of the economic state of California

is decidedly divided along party lines. Previous empirical findings on county-level data on unemployment and election results based on gubernatorial elections have found that unemployment and the Democratic vote are forces that move together. The study found that across 175 gubernatorial elections, higher unemployment rates in counties led to larger shares of the vote for Democrats (Wright 2012). In relation, this would seem to hold true regardless of if a Republican or Democrat were the incumbent.

While California is known for its overwhelmingly Democratic majorities, there is no denying that there are sizable numbers of conservative Republicans across the state as well. Since California is one of our largest states, it is also our most populous. The vote in counties with a large, dense population compared to those that are less populous could allow for changes in voting behavior. The state has not elected a Republican statewide since 2006 (McGhee 2020). The state was not always as Democratic as it has become today. The Bay Area, Los Angeles County, and areas along the coast have developed the most from red to blue. However, the interior areas of the state in the northern region and the eastern border tend to have more party-line votes and hold conservative county majorities.

The units of analysis for this study are the 58 counties of the U.S. state of California. The dependent variable is the vote of “yes” to recall Governor Gavin Newsom. Voters in this election were given two options. Voting “yes” would lead to a second question in which voters would be asked who they would like to replace Newsom if he were to be recalled. Those who voted “no” would like Newsom to remain in office. Data for the dependent variable was found on the CNN Politics website.

There are seven independent variables in this study that have been observed to determine their effect on the voting outcome of the recall election. The data for the independent variables of population density, percent of the African American population, percent of the Latino population, and percent of the population with a college degree can be found on the U.S. Census Bureau website. The data for the number of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people the week before the recall election can be found on the Mayo Clinic website. The data for the percentage of the Trump vote can be found on the Politico website of 2020 election results. The data for the unemployment rate can be found in reports provided by the Employment Development Department of California’s website. All variables are included in Table 1 with their sources.

the vote to recall Governor Newsom will decrease.

H2- As the Latino population in a county increases, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will decrease.

H3- As the unemployment rate increases in a county, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will increase.

H4- As the percent of those with a college degree in a county increases, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will decrease.

H5- As the vote for Trump increases in a county, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will increase.

H6- As the county population density increases, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will decrease.

H7- As the number of COVID-19 cases in a county increases, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will increase.

After running a correlation analysis, three of the independent variables proved to be statistically insignificant in relation to the dependent variable. The variables that were insignificant were percent African American 2020, percent Latino 2020, and unemployment rate. The independent variable of percent with a college degree was significant at p<.01 with a correlation coefficient of -.791. The percent who voted for Trump was significant at p<.01 with a correlation very close to 1 (.995). The variable has a positive correlation with the dependent variable. Population density was significant at a p-value of .002 and a correlation of -4.05. The percent with a college degree and population density variables share negative correlations with the dependent variable. The last significant independent variable was the number of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population at p<.01 with a correlation of .652. This variable also shares a positive correlation with the dependent variable. Correlations for each independent variable are shown in Table 2.

Independent Variables

Percent that Voted Yes to Recall

African American Population 2020 -.250

Latino Population 2020 -.057

Unemployment Rate -.159

Percent with a College Degree -.791**

Percent Trump vote 2020 .995**

Population Density -.405**

Number of COVID Cases Per 100,000 .652**

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), N=58

Figure 1 is a bivariate regression analysis that demonstrates a positive relationship between the percentage of the Trump vote in 2020 and the vote to recall Governor Newsom. An r2 value of 0.991 indicates that the percentage of the Trump vote explains 99.1 percent of the variance in the dependent variable to vote yes to recall Governor Newsom. The y-intercept is 1.32. This would be defined as if there were no votes for Trump, the percentage of the vote to recall Newsom would be 1.32. The slope of the regression line is 1.08, meaning that for every percentage point increase in the votes for Trump, there will be an increase of 1.08 in the vote to recall Newsom.

Regression Line Equation: Y= 1.32 + 1.08X, N=58

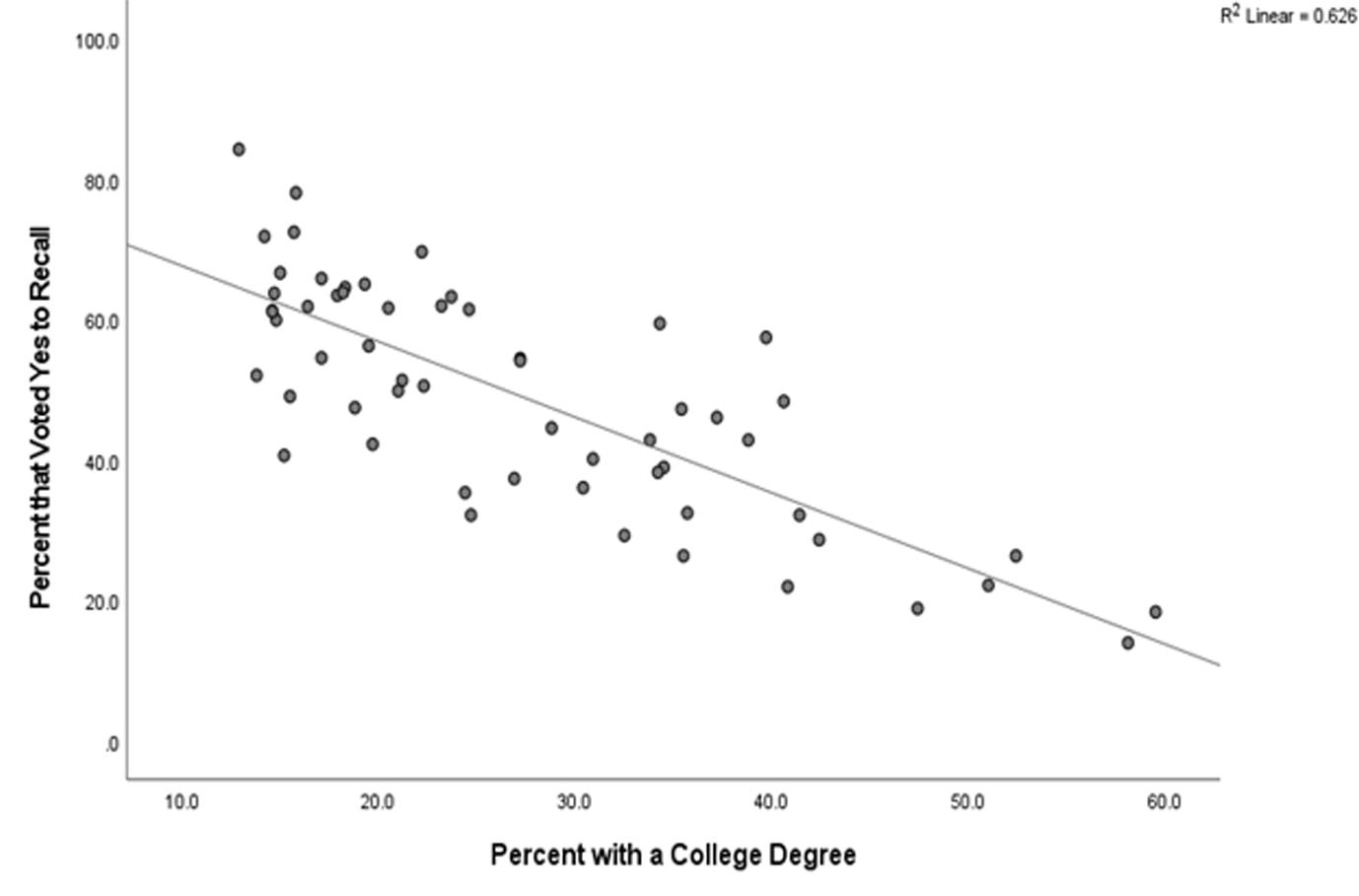

The correlation of -.791 between the percent with a college degree and the percent that voted to recall is highly significant at p<.01. Figure 2 displays the inverse relationship these two variables share. The y-intercept is 78.39, meaning that if there was 0 percent of the population with a college degree, the percentage of the vote to recall Governor Newsom would be 78.39. The slope of the regression line is 1.08, which indicates that for every percentage increase in the population with college degrees, there will be a 1.08 decrease in the yes vote to recall. The r2 coefficient reveals that the percentage of the population with a college degree explains 62.6 percent of the variance in the vote of yes to recall.

Regression Line Equation: Y= 78.39 - 1.08X, N=58

The multivariate regression analysis in Table 3 reveals that the number of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population and population density is no longer statistically significant. The variable that remains highly statistically significant is the percent of the population with a college degree. Due to multicollinearity, the percent that voted for Trump in 2020 is so strongly related to the other independent variables that it made it difficult to estimate the effect of the other variables. The variance inflation factor (VIF) of the Trump vote was 4.076. This caused the VIF of the college degree variable to be 5.560. The percent Trump vote in 2020 was not included in Table 3, in order to accurately show the partial effects of the other independent variables. Additionally, the Latino population variable was found significant in Table 3 even though it was previously not significant in the bivariate analysis.

The slope coefficient for the percent with a college degree is -1.113. For every percentage point increase in the population with a college degree, the vote to recall Governor Newsom decreases by 1.113 percent. The slope coefficient for the percent Latino population is -.214. For every percentage point that the Latino population increases, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will decrease by .214 percent. The r2 coefficient for the multivariate regression is .750. This reveals that the independent variables explain 75% of the variance in the vote to recall Governor Newsom. The constant coefficient found when conducting this analysis reveals what the percentage of the dependent variable would be if all the independent variables were set at 0 percent. The constant coefficient for this model is 88.015. If the six independent variables in Table 3 were set at 0 percent, the percentage of the yes vote for the recall election in the dependent variable would be 88 percent.

nor Newsom will decrease). The hypothesis of H2 (i.e., as the Latino population in a county increases, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will decrease) was also accepted. The hypotheses of H6 (i.e., as the county population density increases, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will decrease), and H7 (i.e., as the number of COVID-19 cases in a county increases, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will increase) were rejected. While both variables were found significant at the bivariate level, the multivariate regression revealed that these factors were not significant when controlling for the other independent variables. The hypotheses of H1 (i.e., as the African American population in a county increases, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will decrease), and H3 (i.e., as the unemployment rate increases in a county, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will increase) found no support in either the bivariate or multivariate regression analyses and thus were rejected. As previously stated, the percent of the Trump vote in 2020 was not included in Table 3 due to issues of multicollinearity. This study still finds support for H5 (i.e., as the vote for Trump increases in a county, the vote to recall Governor Newsom will increase) in the correlation and scatterplot analysis. This would make H5 the most significant hypothesis as the bivariate analysis was able to show an almost perfect correlation between this independent variable and the dependent variable.

The results of this study suggest that the counties in which the most votes to recall Governor Newsom would be received are the counties with lower levels of college-educated residents and lower percentages of Latino populations. The variables that displayed a significant negative relationship with the recall vote were the Latino population as well as the percentage of the population with a college degree. The Latino population’s negative association with the independent variable is likely due

to the minority being a core part of Democratic voters in the state. The strongest independent variable was the positive correlation between the dependent variable and the Trump vote in 2020. This was expected in California, a state in which Donald Trump received no electoral votes in the 2020 election. The astonishing correlation coefficient of .991 was found in the bivariate regression model of the 2020 Trump vote. The model provides an accurate depiction of partisanship in the Democratic bastion of California. Voters who cast their ballot for the Republicans in 2020 carried the same vote to the polls for the recall election. Since Californians considered COVID-19 and the economy as the most important issues facing their state, it is striking that the unemployment rate is insignificant as well as having a negative correlation with the vote to remove the Governor. While it is proven that partisanship was the most significant independent variable, the unemployment rate was thought to result in a reward and punishment system regardless of the incumbent’s political party affiliation. COVID-19 cases were found significant at the bivariate level while insignificant in the multivariate regression. This untraditional socioeconomic variable could heavily rely on partisanship and other factors to influence its significance. In future studies, it would be interesting to observe other COVID-19 associated factors that influenced this election such as mask and vaccine mandates as well as mandatory closures that occurred at different stages of the pandemic. Nevertheless, this study was conducted using available, aggregate-level data that was averaged by the geographic units of counties. The investigation of voter attitudes concerning COVID-19 and unemployment policies would require individual-level, disaggregated data.

The six socioeconomic factors in Table 3 account for 75% of the variance in the 2021 recall vote of Governor Gavin Newsom. While Newsom is still a viable future presidential candidate, he will carry with him the legacy of his recall election through his future political career. California is an interesting

state to study since it is such a well-known, infallible Democratic stronghold in the United States. Observational research of strength, as well as the correlation of population density to the dependent variable in the bivariate analysis, reveals that this strength is centered in San Francisco and Los Angeles counties as well as surrounding areas. In future research, the study of the impact of other demographic subgroups of voters would be riveting to see. This could include the percent of the Asian population, inclusion of certain age ranges such as those who are 65 and older, etc. The ongoing political polarization in our country could lead to future recall elections. There is no viable belief California will falter from the voting pattern it has shown in the past decades. If Democratic candidates continue to be elected, the recall election process could occur again years from now due to partisan opposition. Nonetheless, others may view recall elections as unsuccessful and would rather wait until the general election. Thus, there is not as much attention placed on California since it is not known to be a swing state. However, the rare electoral event of a gubernatorial recall election places a political bellwether of attention on our 2nd largest and most populated state.

Baldassare, Mark, Dean Bonner, Alyssa Dykman, and Rachel Lawler. 2020. “Race and Voting in California - Public Policy Institute of California.” Public Policy Institute of California. https://www.ppic.org/publication/ race-and-voting-in-california/ (November 28, 2021).

Baldassare, Mark, Dean Bonner, Rachel Lawler, and Deja Thomas. 2021a. “California’s Likely Voters.” Public Policy Institute of California. https://www.ppic.org/publication/californias-likely-voters/ (November 28, 2021).

—. w2021b. “PPIC Statewide Survey: Californians and Their Government.” Public Policy Institute of California. https://www.ppic.org/publication/ppic-statewide-survey-californians-and-their-government-september-2021/ (November 28, 2021).

Blood, Michael R. 2021. “California GOP Licks Wounds after Another Lopsided Loss.” AP NEWS. https:// apnews.com/article/california-recall-elections-california-election-2020-recall-elections-4a135cc452bf758a2206d3632e597102 (November 27, 2021).

“California Coronavirus Map: Tracking the Trends.” Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/coronavirus-covid-19/ map/california (November 27, 2021).

“California’s September 2021 Unemployment Rate Holds at 7.5 Percent.” 2021. www.edd.ca.gov. https://www.edd. ca.gov/newsroom/unemployment-september-2021.htm (November 27, 2021).

Coleman, Charley. 2011. Recall Elections. London: House Of Commons Library. http://tjvodici.com/Arhiva/ VodiciKonacno/Energija/Razno/literatura/Recall%20 Elections.pdf (April 27, 2022).

“Gavin Newsom Recall, Governor of California (2019-2021)/ Path to the Ballot.” Ballotpedia. https://ballotpedia. org/Gavin_Newsom_recall,_Governor_of_California_ (2019-2021)/Path_to_the_ballot (December 5, 2021).

Goldberg, Michael. 2020. “Is One Former Republican Stronghold in Deep Blue California a Suburban Bellwether?” State of Reform. https://stateofreform.com/news/ california/2020/09/is-one-former-republican-stronghold-in-deep-blue-california-a-suburban-bellwether/ (November 27, 2021).

“Gray Davis Recall, Governor of California (2003).” Ballotpedia .https://ballotpedia.org/Gray_Davis_recall,_Governor_of_California_(2003) (December 5, 2021).

Grossman, Guy, Soojong Kim, Jonah Rexer, and Harsha Thirumurthy. 2020. “Political Partisanship Influences Behavioral Responses to Governors’ Recommendations for COVID-19 Prevention in the United States.” SSRN Electronic Journal 117(39). (April 27, 2022).

Hoeven, Emily. 2021. “How Both Sides Weaponize California Unemployment Rate in Recall.” CalMatters. https:// calmatters.org/newsletters/whatmatters/2021/08/california-unemployment-newsom-recall/ (November 27, 2021).

Joslyn, Mark R., and Donald P. Haider-Markel. 2014. “Who Knows Best? Education, Partisanship, and Contested Facts.” Politics & Policy 42(6): 919–47. (April 27, 2022)

Kang, Gene. 2021. “Why Is California Gov. Newsom Facing Recall? Frustration with COVID Orders Led to Election.” KTLA. https://ktla.com/news/california/why-iscalifornia-gov-newsom-facing-recall-frustration-withcovid-orders-led-to-election/ (December 5, 2021).

Kondik, Kyle, and J. Miles Coleman. 2021. “The California Recall: Looking under the Hood as Vote Count Finalized –Sabato’s Crystal Ball.” University of Virginia Center for Politics. https://centerforpolitics.org/crystalball/articles/ the-california-recall-looking-under-the-hood-as-votecount-finalized/ (November 27, 2021).

McGhee, Eric. 2020. “California’s Political Geography - Public Policy Institute of California.” Public Policy Institute of California. https://www.ppic.org/publication/californias-political-geography/ (November 27, 2021).

McIver, John P. 1982. “Unemployment and Partisanship.” American Politics Quarterly 10(4): 439–51. (April 27, 2022).

“MEET the BOARD.” REBUILD CALIFORNIA. https://www. rebuildcalifornia.com/meet-the-board/(December5, 2021).

“Recall Election.” 2021. www.fppc.ca.gov. https://www.fppc. ca.gov/transparency/top-contributors/recall-election-Newsom.html/ (December 5, 2021).

Ronayne, Kathleen. 2021. “California Voters: Less Republican and White than in 2003.” AP NEWS. https:// apnews.com/article/entertainment-elections-california-voting-race-and-ethnicity-5113544f216da2fda4f7983410313335 (October 22, 2021).

United States Census. 2021. “Story Map Series.” Census. gov. https://mtgis-portal.geo.census.gov/arcgis/apps/ MapSeries/index.html?appid=2566121a73de463995ed2 b2fd7ff6eb7 (November 27, 2021).

US Census Bureau. 2019. “QuickFacts: United States.” Census Bureau QuickFacts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/ fact/table/US/PST045219 (November 27, 2021).

Vestal, Allan James et al. “Live Election Results: 2020 California Results.” www.politico.com. https://www.politico. com/2020-election/results/california/ (November 27, 2021).

Wright, John R. 2012. “Unemployment and the Democratic Electoral Advantage.” The American Political Science Review 106(4): 685–702. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23357704?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents (November 27, 2021).

Article Abstract:

This research focuses on the causes of the Seminole Wars of the Nineteenth Century. Research shows that the Seminoles were often pushed into these conflicts by the United States, which maintained the belief that it was not the aggressor. The series of wars between the Seminoles and the United States have often been considered separate conflicts. However, there is a common thread that ties all three wars together and illustrates the complexity of the relationship between the U.S. propaganda and the actual events. Indeed, it is more accurate to designate these events over the century as a single war with two ceasefires. From the onset of the conflict with the Seminoles, the U.S. was preoccupied with issues that allowed the war with the Seminoles to be used as a pawn in achieving other political goals, including dealing with escaped slaves and the desire to control more land. In contrast, when the Seminoles went to war, they fought for their homes and for their basic right to maintain their traditional way of life. To establish the single war theory, this article will look at each of the traditionally labeled Seminole wars and examine the history and causes of each. The article will then examine the relation of the causes and the use of the Seminoles as means to achieve U.S. political goals. Finally, the article will argue that the continued U.S. encroachment into Seminole territory was a single unified political strategy toward larger territorial goals.

“On a cold and wet morning in early March 1818, a sizeable contingent of U.S. regulars, militia, volunteers, and Creek warriors under the direct command of Major General Andrew Jackson departed Fort Scott in Georgia and crossed into Spanish Florida. The First Seminole War had commenced.… This seemingly brief episode in the volatile and fabled history of U.S. expansion was anything but an isolated incident.”

-William S. Belko on the outbreak of the Seminole Wars.1

In the nineteenth century, the United States went to war with the Seminole people on three separate occasions. Officially beginning in 1817, the leadup to the first war shows multiple causes that suggest that the United States felt threatened, but that the Seminoles were not necessarily making any threats. The Seminole War era of Southeastern United States history was about a forty-year period from 1817 to 1858 following the United States’ Indian policy of westward removal. In this time, the federal government of the United States actively attempted to remove many eastern Native American groups to the west of the Mississippi River and to lands that today make up large portions of the state of Oklahoma. These wars are often studied separately; however, the causes for each of the three wars share many similarities, suggesting that after the outbreak of war in 1817, the following separate Second and Third Seminole Wars were not separate conflicts but a continuation of the First war. This research shows that on closer inspection of the causation of each of the Seminole Wars, the Seminoles did not choose to go to war, but were pushed into conflict by the United States, which maintained the idea that it was not the aggressor in the wars.

1 William S. Belko, “Epilogue to the War of 1812: The Monroe Administration, American Anglophobia, and the First Seminole War,” in America’s Hundred Years’ War: U.S. Expansion to the Gulf Coast and the Fate of the Seminole, 1763-1858, ed. William S. Belko (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2011), 54.

A major issue that arose early on during these conflicts was an understanding of who the Seminole people were. Historian Joe Knetsch discusses how Western culture has combined many Southeastern Native American groups into one loose confederation under the Creeks. Knetsch also explains why this identification is not historically accurate due to how it fails to recognize the diversity of these Native peoples.2 The reason for this misunderstanding lies in the similarities between people of the Creek Confederation such as the Muscogee and those of Native groups such as the Seminoles and Miccosukees, especially regarding their clan structure. Settler culture looked at these similarities and ignored the distinctions between the cultures.

Knetsch describes clan structures among early Seminole communities as “matrilineal and membership was determined by the mother’s family. A man was always a member of his mother’s clan, but his children were members of his wife’s clan.”3 Clan membership was a major part of one’s life and defined one’s kinship to others, including, “whom to joke with, whom to marry, whom to defend or avenge, etc.”4 While clan structure was similar to other Indigenous communities in the region, the Seminole communities did not consider themselves to be Creek and were not represented by the Creek Confederation. Knetsch explains that “It may be because of these vast relationships that [W]hite society became so confused about the nature of Native American society and lumped them all together in a Creek Confederation.”5 Concepts of justice and retribution were major cultural factors that contributed to conflicts between the Seminoles and White settlers. The Seminoles handled justice differently than settlers were accustomed to, and settlers were

2 Joe Knetsch, Florida’s Seminole Wars:1817-1858 (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 10.

3 Knetsch, 10.

4 Knetsch, 10. 5 Knetsch, 10.

often unwilling to respect this difference in culture. Seminole culture recognized the need for a justice system, but they did not include imprisonment, a typical practice in the White justice system. Indigenous concepts of justice involve restitution, not retaliation or revenge. Because neither side understood the other’s concept of justice, these practices among settlers and Seminoles often led to conflict.6

The Garrett Killings was an event that involved the killing of white settlers Mrs. Obediah Garrett and her children following an attack on a group of Seminoles by settlers. This event was a result of the Seminoles and Whites failing to respect differing cultures.7 Around the outbreak of the First Seminole War, these killings were the only examples of the Seminole hostility toward settlers. Some White settlers were able to understand at the time that these killings were not unprovoked, unlike leaders such as General Gaines. For instance, Indian Agent David Mitchell advised that the Garrett Killings clearly reflected Native American principles of ‘retaliation,’ now understood as a form of restitution.8 And because of this misinterpretation of justice, Seminole chiefs in the region, such as Neamathla, the Chief of Fowltown,9 were not willing to turn over to the White justice system those who were accused of the Garrett Killings.10

General Gaines also reported that cattle rustling was the primary issue between White settlers and Seminoles.11 John and Mary Lou Missall explained that “Particularly troublesome was the matter of cattle theft. Florida abounded in good range land, and the Seminoles excelled at animal husbandry.”12 Lead-

6 Alfred A. Cave, Sharp Knife: Andrew Jackson and the American Indians (Santa Barbara California: Praeger, 2017), 85.

7 Cave, 84-85.

8 Cave, 85.

9 Fowltown is the name of an important Seminole village that was located in Georgia, close to the border of Spanish Florida.

10 Cave, Sharp Knife, 85.

11 Cave, 84-85.

12 John Missall and Mary Lou Missall, The Seminole Wars: America’s Longest Indian Conflict (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004), 32.

ers among Whites such as Gaines accused Seminoles of stealing livestock. However, “Backwoods [W]hites, coveting the Indians’ herds and grazing land, seized every opportunity to steal Seminole cattle. The Indians, feeling a need for just retribution, stole [W]hite cattle.”13 General Gaines can be seen as having directly contributed to the war by failing to recognize the culture of the Seminoles and by sending fanciful stories about the events along the Florida-Georgia border, claiming that “Indian hostilities had made it impossible for settlers on the Georgia frontier to plant crops, all their livestock having been stolen and their houses occupied”14 while completely ignoring the acts of violence Whites committed towards the Native American population. These reports eventually contributed to the military leadership authorizing the First Seminole War. A misunderstanding of the Seminoles’ concept of retribution led directly to the outbreak of the First Seminole War, the Scott Massacre.15 On November 30, 1817, a group of Seminoles attacked a supply convoy that was under the command of Lieutenant Richard W. Scott. Knetsch explains that this battle became justification for the United States to increase their involvement in Spanish Florida.16 However, the motives of the Seminoles involved in this battle were not to start a war, but to gain retribution for an attack on their people that had occurred on November 23, 1817. After Neamathla refused a summons to Fort Scott, troops were sent and ordered to burn down the village of Fowltown.17 It was after this burning that the Seminoles sought retribution in the form of the Scott Massacre.

13 Missall and Missall, 32.

14 Cave, Sharp Knife, 86.

15 The Seminole attack on Lieutenant Scott’s supply convoy has been labeled as a ‘massacre’ to instill fear and to further add to the belief that Seminoles were uncivilized.

16 Joe Knetsch, Florida’s Seminole Wars, 27.

17 Knetsch, 23-24. The military attack on Fowltown could also be characterized as a massacre, however, in many historical accounts this has not been the case. Seminole attacks on Whites have often been historically referred to as massacres. White attacks on Seminoles have often been historically referred to as “battles” or “attacks.” This word usage has intentionally slanted the discussion to the advantage of the White population.

The topic of slavery was another major issue between the United States and the Seminoles prior to the First Seminole War. Within the United States, there were fears of Seminole threats regarding the peacefulness of slaves in the South, including rumors that Seminoles had called for Blacks to go south for freedom.18 Slavery existed among the Seminoles; however, the practice worked in a different way than slavery among the White population of the United States. Joe Knetsch in Florida’s Seminole Wars: 1817-1858 explains that “slavery, as practiced by the Seminoles, Miccosukees, and others of their relations, was a very benign form.”19 This was a challenge to the authority of the White population of the Southern United States, who were losing slaves that ran away to better conditions and a safe-haven provided by the Seminoles. Knetsch also explains that “over time, a bond developed between escaped Africans and the Seminoles that only increased with time and [W]hite pressure for their return.”20 This bond was such an issue among the United States and the Seminoles that Knetsch concludes that “the relationship and existence of the combined Seminoles, Miccosukees, and escaped slaves would be the most important cause of the Seminole Wars.”21

Joshua Reed Giddings provides primary evidence explaining the importance of runaway slaves in the Seminole Wars in his 1858 publication, The Exile of Florida: Or, The Crimes Committed by Our Government against the Maroons Who Fled from South Carolina and Other Slave States, Seeking Protection under Spanish Laws. Giddings explains that prior to the First Seminole War the people of Georgia “were greatly excited at

18 Cave, Sharp Knife, 82. The terms “Black” and “Negro” are used in this paper to reference African, Caribbean, and African Americans because that is the reference term used in history and is not intended to be used in any way that implies that these terms are accurate in defining the people to which they refer. Simarily, any use of the term “Whites” is used to match the use in historical record to refer to people of European descent.

19 Knetsch, Florida’s Seminole Wars, 12. 20 Knetsch, 12-13. 21 Knetsch, 13.

seeing those who had once been slaves, in South Carolina and in Georgia, now live quietly and happily in the enjoyment of liberty, … but they were on Spanish soil, protected by Spanish laws.”22 In this work, Giddings confirms that the United States’ main goal throughout the Seminole Wars centered around the capture and re-enslavement of people he called “the Exiles of Florida”: runaway slaves and their descendants.

A specific example of conflict involving runaway slaves is the “Negro Fort” in Spanish Florida. According to Alfred Cave in Sharp Knife: Andrew Jackson and the American Indians, a major point of tension was the presence of a “very well-armed fort the British had built at Prospect Bluff” that became occupied by Native Americans and Blacks (mostly escaped slaves).23 Cave goes on to explain that the United States had tried to get Spain to address the issue of this “Negro Fort,” but “Generals Jackson and Gaines had their own plans.... [which involved that] they first undertook a frontier fortification project.”24 The generals built Fort Scott on the Georgia side of the border, then in late July, a naval flotilla crossed into Spanish waters to travel upriver and provision the new fort. On the way, the expedition stopped and bombarded the “Negro Fort.” The attack ended almost immediately; a shot hit the powder magazine causing a massive explosion and killing 270 of the 320 people residing in the fort. Many of the survivors of this massacre fled to the nearby Seminole village of Fowltown. Shortly after these events, “concern over activities at Fowltown … soon replaced anxiety about the Negro [F]ort.”25 These actions indicate that the fears of Native Americans, such as the Seminoles, were less about the Natives themselves and more related to the Blacks who lived alongside them.

22 Joshua Reed Giddings, The Exile of Florida: Or, The Crimes Committed by our Government Against the Maroons Who Fled from South Carolina and Other Slave States, Seeking Protection under Spanish Law (Columbus: Follett, Foster, and Company, 1858), 29.

23 Cave, Sharp Knife, 82.

24 Cave, 82.

25 Cave, 83

The Treaty of Fort Jackson was one of the main causative agents of the First Seminole War. This treaty between the United States and the Creek Confederation contributed to the start of the First Seminole War because of the land cessions that the Creeks made. The issue that arose dealt with Native Americans within the new borders that were not a part of the Creek Confederation and did not cede their lands. This included villages, such as the Seminoles, and chiefs who did not attend the signing of the Treaty of Fort Jackson. Fowltown, one of these villages, was located within the Georgia border, but did not consider themselves Creek, and therefore believed that the Creek were unable to give away lands that belonged to people not represented by the Creek Confederation.27 Knetsch explains that “To Neamathla, the treaty [of Fort Jackson] meant nothing and his people occupied the land, which gave them rights to its use.”28 However, to the commander of the new Fort Scott, General Gaines, the Treaty applied to Fowltown. When Neamathla refused to meet with him, Gaines ordered the massacre of Fowltown, which occurred on November 21, 1817.29

The Fowltown Massacre marks the start of the First Seminole War from a Seminole perspective. However, in United States history, the start of the war has been attributed to the Seminole’s counterattack: the Scott Massacre. The White narrative of the event begins when Lieutenant Richard W. Scott and forty men traveled downriver from Fort Scott to meet with Major Peter Muhlenberg’s supply convoy. Scott was warned that Seminoles were gathering along the river to make a stand against anyone traveling upstream. Instead of heeding this warn-

26 The First Seminole War was formally fought between the United States and the Seminole people from 1817-1818.

27 Missall and Missall, The Seminole Wars, 36.

28 Knetsch, Florida’s Seminole Wars, 23.

29 Knetsch, 23-24.

The Seminole Wars of the 19th Century

ing, Muhlenberg replaced twenty of Scott’s men with some of his injured soldiers and ordered Lieutenant Scott to travel upstream.30 Accounts of who was with Lieutenant Scott vary; some unconfirmed narratives included the deaths of children, and “later reports, especially those found in the congressional debates, stressed the presence of the children, but a political motive for these is easily assumed.”31 At the time, the presence of children was the most important detail of the massacre. Knetsch also states that “the story of this battle has been clouded by reports from a variety of contemporaries and historians.”32 Knetsch is sure that “the battle of November 30, 1817, became the reason for the approval of further incursions into Spanish Florida.”33 The United States now had a way to justify going to war with the Seminoles, despite having created that justification by antagonizing their opponent, with the perpetration of their own massacres against Seminoles and Blacks.

The United States military strategy and propaganda belied the fact that the Seminole wars were not specifically about subduing a “threat” to settlers or the government. The military during the first conflict was more concerned with conquering Spanish Florida, making the Seminole issue an excuse for incursion. When given the go-ahead to deal with the “Seminole menace,” Calhoun specifically forbade General Jackson from making any hostile actions against the Spanish. Jackson then wrote directly to President Monroe, claiming that he could seize Florida in sixty days if it “would be desirable to the United States.”34 Jackson claimed that the President approved of this plan to seize East Florida; however, many historians believe that Jackson either lied about receiving authorization, took silence as consent, or interpreted Monroe’s overall confidence in him as a green

30 Knetsch, 26. 31 Knetsch, 27. 32 Knetsch, 26-27. 33 Knetsch, 27.

34 Andrew Jackson in Alfred Cave Sharp Knife: Andrew Jackson and the American Indians, (Santa Barbara California: Praeger, 2017) 86-87.

light.35 By the end of the war, General Jackson had deposed the Spanish Governor of East Florida.36 For those who initiated the war, the First Seminole War had little to do with the Seminoles and more to do with a military invasion of a Spanish colony and issues regarding slavery.

Second Seminole War37

The Second Seminole War allegedly broke out in late 1835. While this war was said to have dealt with its own issues, there were many similarities to the previous Seminole war, especially regarding the causes of the conflict, which suggest that the two events were not separate but a continuation of previous U.S. policy and related to earlier conflicts.

Unlike the start of the First Seminole War, where the outbreak of war can be attributed to the United States, Western historians attribute the official start of the Second Seminole War to events of aggression made by the Seminoles such as the Dade Massacre38 and the assassinations of important U.S. leaders at Fort King. Osceola was an important leader among the Seminoles, even leading the attack at Fort King. Prior to the December attack, “the signal that a war had actually begun came in late November 1835.”39 Charley Emathla, typically considered a well-respected Seminole chief, decided to emigrate. This decision contradicted the stance of the rest of the Seminole Tribe, and at the time, “to go against the expressed wishes of the entire tribe was considered treason.”40 Because of this choice, Osceola

35 Cave, Sharp Knife, 87.

36 Cave, 87.

37 The Second Seminole War was formally fought between the United States and the Seminole people from 1835-1842.

38 Similar to the “Scott Massacre,” the “Dade Massacre” is classified as a massacre to continue the false image of Native Americans as people of lesser value.

39 Missall and Missall, The Seminole Wars, 92.

40 Missall and Missall, The Seminole Wars, 92. This is similar to U.S. treatments of treasonous behavior. In the eyes of the Seminoles, Charley Emathla was not just “emigrating” to the west, he was taking information, including military information, to an enemy force.

met Emathla on the way to Fort Brooke to kill Emathla. The execution of Emathla confirmed Osceola as a primary leader of the Seminole people.41 Then, on December 28, “a well-planned and executed attack led by Osceola” resulted in the deaths of Indian Agent Wiley Thompson, Lieutenant Constantine Smith, Erastus Rogers, and four other United States military officers.42 This attack at Fort King occurred on the same day as the Dade Massacre, the other act of aggression that allegedly started the Second Seminole War.

The military maneuver of the Dade Massacre shares some distinct similarities to the Scott Massacre that began the previous war. Major Frances Dade and a company of 108 soldiers were attacked by a group of around 180 Native Americans and Blacks. In this attack, three of Dade’s soldiers survived. The Seminoles only lost three men. Due to the Dade Massacre and the attack on Fort King, the U.S. would return to a state of war, now known as the “Second Seminole War.”

Also important is that for many Seminoles, the inter-war period between the first and second Seminole Wars was not a time of peace; they still experienced a state of war. From this viewpoint, the attacks at Fort King and on the Dade company were military maneuvers that were a part of an ongoing war, not acts of aggression meant to start a new war.

While from a Western perspective it is in the Second Seminole War that the first acts of aggression were taken by the Seminoles, the United States was not completely blameless for the return to war with the Seminoles. The United States was working to force the Seminoles to emigrate43 to the West. John

41 Missall and Missall, The Seminole Wars, 92. Emathla’s death has been referred to as an execution or assassination by multiple Western scholars, but from the Seminole perspective could be considered to be a justifiable elimination of a traitorous figure.

42 Joe Knetsch, Florida’s Seminole Wars, 71.

43 The term ‘emigrate’ is used to refer to the United States policy of removing Native people from their homeland and placing them on reservations in Indian Territory (located in present-day Oklahoma). The use of this term is not intended to disregard the horrors that were forced upon the people who had to endure this involuntary removal from their land.

Missall and Mary Lou Missall explain that having issues with emigration can be a difficult concept because common understandings of migration involve moving to a better place, but “for the Indians, it usually meant going to a worse one.”44

The resistance to leave their homeland ensured that Seminoles would be in close proximity to White settlers, which led to issues and conflicts between the two. Prior to the return to war, “a state of ‘temporary hostilities’ again hit the frontier of Florida. The main reason that the [Indian] agent gave was the poor conditions of the Native Americans and the constant intrusion into their lands by [W]hites hunting cattle and escaped slaves.”45 Many of these Whites that intruded on Seminole lands were “of unscrupulous behavior” and were “simply taking whatever black men, women, and children they found and claiming them to be escapees.”46

Issues from the First Seminole War clearly had a contributing effect in accounting for the poor living conditions of the Seminoles prior to the Second Seminole War. The Treaty of Moultrie Creek, signed on September 18, 1823, a few years after the First Seminole War, established the Seminole’s territory. In this treaty the United States Congress agreed to appropriate five thousand dollars a year to the Seminoles. However, this money mostly went to government agents instead of assisting the Seminole people.47

There were also rising tensions regarding the Blacks living among the Seminoles. “It had constantly been maintained by the governor and others that some of the blacks living within the nation actually controlled the policy of the Seminoles and Miccosukees toward emigration and had always opposed it.”48 This was unsubstantiated propaganda and did not fit with Seminole

44 Missall and Missall, The Seminole Wars, 69.

45 Knetsch, Florida’s Seminole Wars, 58.

46 Knetsch, 58.

47 William C. Emerson, The Seminoles: Dwellers of the Everglades: The Land, History, and Culture of the Florida Indians (New York: Exposition Press, 1954), 28.

48 Emerson, The Seminoles, 59.

culture or practices. C.S. Monaco explains why White officials had issues with Seminoles claiming slaves as their own; “Native slave ownership undermined a central tenet of settler-colonialism. Indians, given their supposedly wild and childlike natures, … were thought to be incapable of managing the land, let alone slaves; hence, colonizers had an implicit and righteous duty to appropriate these wasted resources.”49 The existence of a slave society among Native people raised into question the assumption that Natives were unable to manage such a society, which, interestingly, also belied the Euro-American hierarchy of humans that placed American Indians lower than Africans. Some historians have taken these fears and concerns among the White population regarding the Black population living with the Seminoles into account. This situation led some to find, as suggested at the time by U.S. General Thomas Jesup, that the Second Seminole War “is a negro, not an Indian war.”50 Matthew Calvin in his study of this theory found that as the war progressed, there was an increase in accusations that African Americans were responsible for the war regardless of the evidence that this was not the case.51 Monaco, on the topic of Black control over the Seminoles during the war, finds that “no tangible evidence exists that African Americans ever appropriated Native authority.”52 Historiographical interpretations of African Americans as leaders of the Second Seminole War originated during the latter half of the twentieth century and failed to recognize the power of the Seminoles, disregarding them in a con-

49 C.S. Monaco, The Second Seminole War and the Limits of American Aggression (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), 39.

50 General Thomas Sidney Jesup said, quoted in Matthew Clavin, “‘It is a negro, not an Indian war’: Southampton, St. Domingo, and the Second Seminole War,” in America’s Hundred Years’ War: U.S. Expansion to the Gulf Coast and the Fate of the Seminole, 1763-1858, ed. William S. Belko (Gainesville, Fl: University Press of Florida, 2011), 193.

51 Matthew Clavin “‘It is a negro, not an Indian war’: Southampton, St. Domingo, and the Second Seminole War,” in America’s Hundred Years’ War: U.S. Expansion to the Gulf Coast and the Fate of the Seminole, 1763-1858, ed. William S. Belko (Gainesville, Fl: University Press of Florida, 2011), 196.

52 C.S. Monaco, The Second Seminole War and American Aggression, 41.

tinued condescension towards Native people.53 Regardless of the actual involvement of Blacks and African Americans among the Native population, the settlers and officials from the United States claimed that they were in play, which allowed them to justify the Second Seminole War.

An analysis of congressional discussions on the Second Seminole War immediately after the conflict illustrates how leaders in the United States viewed the War and what they believed was significant. Document number fifty-five from the twenty-seventh Congress’s second session is a message from the President to Congress covering the cause of the war with the Seminoles as well as the number of Slaves captured during the conflict. In this nine-page document, General Thomas Jesup estimated that “the number captured during the short period of my command amounted, I think, to more than four hundred.”54 How General Jesup determined this number is unclear, and other important information is not provided, such as any estimates of how many slaves were killed during the war. The importance of documents such as this is to show that leaders in the United States were still not primarily focused on the Seminole people despite being at war with them. Instead, United States leaders were focused on other issues, in this case, the number of slaves gained from the war.

While it can be interpreted that Seminoles began the war in 1835 in order to resist removal, historians such as Samuel Watson point out that this idea disregards the many other forms of resistance other native groups attempted to use.55 The reason

53 C.S. Monaco, “Whose War Was It?: African American Heritage Claims and the Second Seminole War,” American Indian Quarterly, no. 41 (2017) 39-40.

54 Thomas Sidney Jesup in John Tyler, “Seminole War— Slaves Captured Message From the President of the United States Transmitting the information called for by a resolution of the House of Representatives of August 9, 1841, in relation to the origin of the Seminole War, of Slaves captured,” (3 September 2020), Slavery Papers, Speeches, and Manuscripts, Box 1 Folder 28, Slavery Papers, Valdosta State University Archives and Special Collections, Valdosta, GA, no. 55 (Washington: Quartermaster General’s Office, 1841), 2.

55 Samuel Watson, “Seminole Strategy, 1812-1858: A Prospectus for Further Research,” in America’s Hundred Years’ War: U.S. Expansion to the Gulf Coast and the Fate of the Seminole, 1763-1858, ed. William S. Belko (Gainesville, Fl: University Press of Florida, 2011), 159.

The Seminole Wars of the 19th Century

that Watson gives for war being the only option the Seminoles had to resist removal was that their lack of acculturated leaders who could be readily identified in other Native American communities. In other Native communities, the leaders were often able to pursue other non-military options.56 As war was the Seminole people’s only option, they had to take a position “on the offensive in defense of their homes” which gave them “the luxury of knowing when serious fighting would commence.”57 This concept of “offense in defense” may explain the Seminole strategy as a defensive preemptive strike.

Given the nature of the Third Seminole War, there is less documentation to establish causal factors than its predecessors. For many historians, “the Third Seminole War may appear to be nothing more than an afterthought to the much larger Second Seminole War.”59 However, it can also be understood as the conclusion to the continuing conflict beginning in the First and following through the Second Seminole wars.

For the United States, by 1853, plans to “remove the Seminole from Florida had more or less fallen apart … Large rewards [were offered] for any captured Seminoles,” and several expeditions to South Florida by militia were made to cash in on these rewards.60 During this time, the Seminoles were “trying to build good faith, hoping the [W]hites would see they intended to be friendly.”61 Despite Seminole efforts, Euro-Americans were set on the removal of Seminoles from Florida.

56 Watson, “Seminole Strategy,” 159.

57 Missall and Missall, The Seminole Wars, 93.

58 The Third Seminole War was formally fought between the United States and the Seminole people from 1855-1858.

59 Joe Knetsch, John Missall, and Mary Lou Missall, History of the Third Seminole War: 1849-1858 (Havertown: Casemate Publishers, 2018), vi.

60 Knetsch, Missall, and Missall, History of the Third Seminole War, 72. 61 Knetsch, Missall, and Missall, 75.

The United States Army used a slow attrition strategy to “persuade,” or force Seminoles to accept emigration and removal to the west. By limiting Seminole movements and trade and invading their territory, the goal was to quietly force the Seminoles out of their homes.62 Almost all military accounts from leaders in Florida acknowledge the understanding that “Native Americans wanted peace and would avoid contact with [W]hites whenever the opportunity allowed.”63 The conflict in the Third War started with White settlers, as the same reports state that settlers were hoping to lead the frontier into a state of war.64 Eventually, these attempts would be successful, and on December 20, 1855, the Third Seminole War allegedly began with a Seminole attack on the command of Lieutenant George Hartsuff. All sources point to a consensus best stated by Knetsch, “this war was forced upon the Native Americans in no uncertain terms.”65

The series of wars through the nineteenth century between the Seminoles and the United States continue to be categorized as separate conflicts. However, there is evidence for claiming that the events were part of a single war with two ceasefires. The largest cause of these wars was the refusal of the United States’ leaders and White settlers to recognize the authority and rights of the Seminoles. Major problems between these groups manifested in issues such as slavery among the Seminoles, which United States propaganda felt was a challenge to their authority. However, from the Seminoles’ perspective, the long war was a matter of maintaining their land and way of life. The United States led itself into these conflicts because of its

62 Knetsch, Florida’s Seminole Wars,143. 63 Knetsch, 147. 64 Knetsch, 147. 65 Knetsch, 150.

failure to recognize that, in the eyes of the Seminole people, the United States was not the ultimate authority. This failure would cost many lives to be lost, both Seminole and White. This dark period of United States history is often overlooked but deserves more research and analysis moving forward.

Giddings, Joshua Reed. The Exile of Florida: Or, The Crimes Committed by our Government against the Maroons Who Fled from South Carolina and Other Slave States, Seeking Protection under Spanish Law. Columbus: Follett, Foster, and Company, 1858.

Tyler, John. “Seminole War—Slaves Captured: Message from the President of the United States Transmitting the Information Called for by a Resolution of the House of Representatives of August 9, 1841, in Relation to the Origin of the Seminole War, of Slaves Captured.” Slavery Papers, Speeches, and Manuscripts. Valdosta State University Archives and Special Collections, Valdosta, GA.

Belko, William S. “Epilogue to the War of 1812: The Monroe Administration, American Anglophobia, and the First Seminole War.” In America’s Hundred Years’ War: U.S. Expansion to the Gulf Coast and the Fate of the Seminole, 1763-1858, edited by William S. Belko. 54-102. Gainesville, Fl: University Press of Florida, 2011.

Cave, Alfred A. Sharp Knife: Andrew Jackson and the American Indians. Santa Barbara California: Praeger, 2017.

Clavin, Matthew. “‘It is a negro, not an Indian war’: Southampton, St. Domingo, and the Second Seminole War.” In America’s Hundred Years’ War: U.S. Expansion to the Gulf Coast and the Fate of the Seminole, 1763-1858, edited by William S. Belko. 181-208. Gainesville, Fl: University Press of Florida, 2011.

Emerson, William C. The Seminoles: Dwellers of the Everglades: The Land, History, and Culture of the Florida Indians, New York: Exposition Press, 1954.

Knetsch, Joe. Florida’s Seminole Wars:1817-1858, Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003.

Knetsch, Joe, John Missall, and Mary Lou Missall. History of the Third Seminole War: 1849-1858. Havertown: Casemate Publishers, 2018.

Missall, John, and Mary Lou Missall. The Seminole Wars: America’s Longest Indian Conflict. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004.

Monaco, C.S. The Second Seminole War and the Limits of American Aggression. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018.

Monaco, C.S. “Whose War Was It?: African American Heritage Claims and the Second Seminole War.” American Indian Quarterly. no.41 (2017). 31-66.

Watson, Samuel. “Seminole Strategy, 1812-1858: A Prospectus for Further Research.” In America’s Hundred Years’ War: U.S. Expansion to the Gulf Coast and the Fate of the Seminole, 1763-1858, edited by William S. Belko. 155-180. Gainesville, Fl: University Press of Florida, 2011.

Article Abstract:

As a result of the digital age, journalists must be adaptable, collaborative, and engaging. Technology is a major component of our society. Technology never stays stagnant, and it is always evolving just like journalism and journalists. This article analyzes how the impact of technology affected my experience and role as a journalist, and how it catalyzes evolution in the field of journalism collectively. Along with the constant updates with social media and software, journalists must be willing to learn these new technologies. Journalism caters to society and its community. If the community is accessing their news from a new way of communication, then journalists/journalism needs to figure out how to share news in that new way. Without all opinions and perspectives being shared, one cannot have a marketplace of ideas or have a debate to determine truth. When journalists share this information, it drives debate. It catalyzes the necessary conversations that need to occur so that we can work on our community.

In a small town in Cook County, GA, there has been only one frequent writer in our local newspaper. I saw this journalist at school events, community gatherings, and around the county. He always kept a camera and a notebook with a pen. After being interviewed and photographed for the local newspaper a few times, I wondered why he was the only person I had seen doing

this. I had never seen someone that looked like me work as a writer at the newspaper. Even though I had been featured in the newspaper, I felt like my story and my minority’s perspective were not represented. There was barely any minority event coverage or perspective included in the newspaper. I was initially unsure of why it was so important for me to see a local African American female journalist; after all, there were other local African American broadcast journalists on television, yet there is much to be said about seeing someone physically doing what you aspire to do. Whenever I saw an African American newspaper journalist, it gave me hope and confidence that I could become an advocate for my community.

It was not until my senior year at Cook High School that I found my passion for photojournalism. I was enrolled in a journalism class to help with the school yearbook, and I took pictures at school events and conducted interviews for the page description. I always loved covering the clubs and organizations at my school because I learned about them and got to share them with the rest of the school. Seeing the students’ and clubs’ reactions to their pages fulfilled my goal: giving a voice to the voiceless. This was when I felt the closest to my community. Journalism is a public duty, and journalists must represent and share true news and facts with their community. As a child, I remember reading the newspaper with my grandparents and watching the news every morning and evening. I learned about local breaking news, the weather, and my community in both print and broadcast media. After watching the news, I observed my grandparents, aunt, and mother as they talked about the coverage for that night. We also gathered for elections, bad weather updates, and court verdicts. After watching the news one evening, my family gathered and told me my birth story: I was born on Election Day in 2000 because my mother’s labor was induced due to her high blood pressure.

My mom could not participate in voting, and the nurses had to stop her from watching the news when she got upset as George W. Bush won the election. The fact that people were undergoing life-changing events such as childbirth but still wanting to watch the news exemplifies how important journalism is to the community.

The Trayvon Martin murder and the trial of George Zimmerman were all over the news when I was in middle school, and I recall watching the news coverage and comprehending the fatal events intensively as a national controversy that sparked debates across the United States. My family and I sat all evening waiting for the verdict, and after they acquitted Zimmerman, I remember the debates that ricocheted across my grandma’s living room. I was shocked to see that lots of people had many different opinions. I noticed that even in national controversy, journalists didn’t participate in the debates because they can’t focus on their personal opinions. Journalists still have a job to do, and that was to share the news. No matter what their political or moral position was, journalists remained objective, collaborative, and shared all available information.

That’s when I realized journalists are public community advocates and teachers. They must do their job ethically and authentically, embodying a mission to help their community have awareness and a voice. Opinions and perspectives must be shared; without opposing ideas, you cannot have a marketplace of ideas or have a debate to determine truth. When journalists share multiple perspectives, debate occurs. Opposing viewpoints and conflict catalyzes conversations necessary to enhancing our community. Journalists do not interview sources, write stories, and publish news just for a salary. No, journalists are called to this position because they want to make an impact and change the world. The audience determines the impact and the modality of the news. Reporting can affect so many aspects of our daily lives. It amazes me when the community offers feedback to journalists or debate on the recent news. That’s exactly what I want

to do as a journalist. I want to use my words and reporting to change the world, and I want to have an active impact on others in my community.

For me, being a journalist must highlight diversity, various opinions, and perspectives, while including the facts of the topic. Over the past few years, however, the creditability and truth within news reporting have not been present in some journalistic media. During the Trump administration, the press received major backlash when the fake news allegations spread across the media. These allegations undermined the capability of the press to produce the news ethically and truthfully, and with my acquired skills, I want to show my community that a credible and objective journalist still exists.