When you were a kid, everything seemed simpler.

The sky was blue because Mom said it was. Fairy tales were real. Barbie said “you can be anything,” and you believed it. Nothing was impossible.

But as you grew older, you started to understand your view of the world was limited. The real world has bureaucracy and an affordability crisis. There are social norms to follow, regardless of whether or not they make sense, and no one has actually figured out how to transform into dragons or mermaids in real life.

This year’s magazine hopes to explore these limitations and how they interact and intersect with our lives. As university students, we’re in a unique space where we feel both like kids and adults. For most, this is our first time learning how to be in charge of ourselves, so we haven’t perfected it yet we have to feed ourselves, but no one is stopping us from doing it with a bowl of Lucky Charms. Navigating this space is not easy, but it is worthwhile.

In this magazine, you’ll find articles ranging from blending dance genres and the effect of the climate crisis on insect physiology, to pushing yourself to your physical limits at Storm the Wall and the impact of student evaluations on faculty promotion. They are not only stories of how people are limited, but also of how they are unlimited.

We hope this will inspire you to break through the limits you can, and accept with peace the ones you can’t.

6 A good excuse — Annaliese Gumboc

9 Do SEI surveys measure success or perpetuate bias? — Bernice Wong

12 In one ear, out the other: The limitations of memory research — Maya Levajac

15 ‘Breaking’ limits and ‘locking’ in the unlimited — Stella Griffin

18 Me and my lines — Aditi Mankar

22

20 The Aquatic Centre is an underrated seasonal depression cope — Tova Gaster

For the thrill of the chase: UBC’s love affair with Storm the Wall — Renée Rochefort

Impulse and impulse: A bond between ink artists and musicians — Elena Massing & Fiona Sjaus

28 Calling out for Mom — Brianna Reeve

30 putting myself first — Lauren Kasowski

With all my love, to the rain — Fiona Sjaus

I was about 13 when I discovered I wasn’t normal.

It was the middle of the night after a party. Like most nights, I had crept out of my room for a snack, treading the hardwood floor in socks and leaning against the wall to take the weight off my steps. I was only a few steps into the hallway when I heard voices coming from the kitchen.

There’s something wrong with her, my mom said. I think

something happened with the development of her frontal lobe.

She’s just acting like a normal teenager, my dad countered.

Earlier that evening, I’d poured Sprite into another kid’s bowl of vanilla ice cream. I thought it was funny. My mom thought it was a sign of a developmental disorder.

That comment from any other mother would be paranoid speculation, but my mom was a child psychiatrist.

I slipped back to my room unnoticed and googled ‘frontal lobe’ in bed. I read it was responsible for executive functions, social comprehension, voluntary movement, memory and speech skills. Frontal lobe conditions could cause severe complications like significantly impaired motor and language functions, but milder ones include impulsivity, clumsiness, anxiety, depression, disorganization, a short attention span and difficulty socializing.

Growing up, I had been different. Spacy and anxious, I struggled with bouts of low moods, sometimes suicidal thoughts. I usually had fewer friends than other kids and often felt disconnected from the ones I did have. I regularly forgot assignments and exams — teachers would pull me aside and tell me I had so much potential, if only I would do the work. I was beginning to see why.

That same year, I was dia -

to be associated with people like that; I didn’t want to be seen as less than.

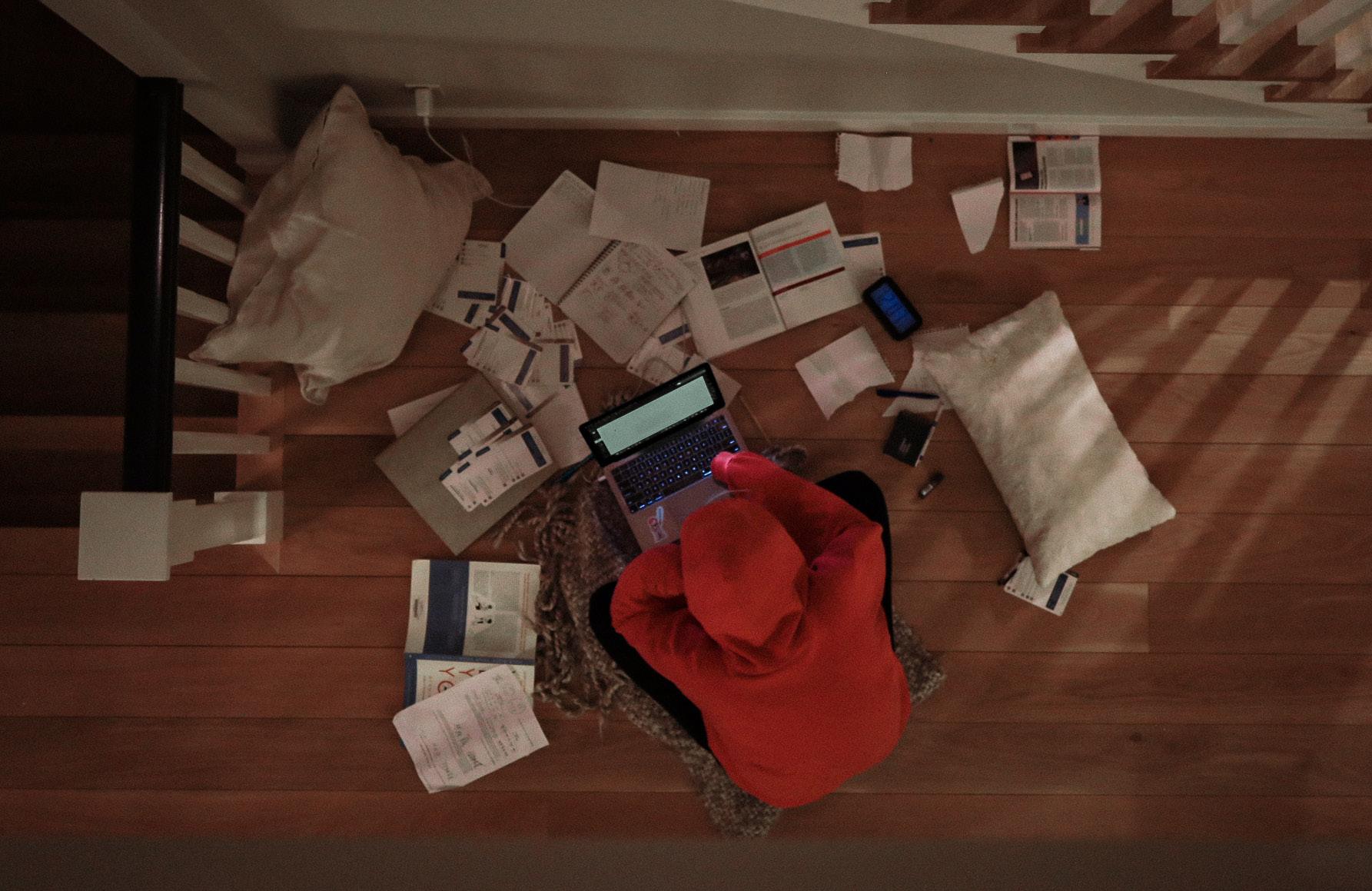

After my diagnosis, little changed. Except for the Adderall. My dad was opposed to me registering for academic accommodations. He said they were a crutch I wouldn’t be given in the “real world.”

Throughout high school, I mastered last-minute submissions and on the fly excuses. I would rifle through my bag in faux confusion, pretending I’d lost my homework, only to finish the assignment under the desk while the teacher collected others’ papers.

Sometimes on exam days, I would see students with accommodations filing into a separate room for testing. I felt a sense of superiority as I struggled to complete exams and didn’t finish a single math test on time. But I still managed to get As. They needed help and I didn’t.

out.

I flew back to Oahu as soon as I could. The cancer had reached her stomach, so she could hardly eat. Her skin stretched so taut over her bones, I feared her joints would pierce through. My family spent most days waiting, crowding her bedside in my grandparents’ home in Aiea. She passed away on an early morning in late June.

That morning, we took turns saying goodbye to her body, then stood outside on the concrete patio under the purple dawn, palm trees and telephone wires crisscrossing overhead, watching as people from the mortuary took her away. We stood apart, and those who cried did so in silence.

In those moments, I saw what it meant to live and die. Homework seemed pointless.

When I returned to university for my second year, everything was different. My grades began to slip and I stopped attending classes. When I did show up, I brought a small bottle of

gnosed with ADHD, a neurodevelopmental disorder related to the frontal lobe. I was given an Adderall prescription and sent on my way.

When I told a friend, she seemed appalled. But you aren’t weird like that, she said, before trying to buy some Adderall off of me.

I knew what she meant by ‘weird like that’ — weird like that boy who sat across from me in grade 8 math, who had Fs on his report card and beat his head against the desk when the teacher yelled at him. I didn’t want

The summer after first year, I got a call about my auntie. She had stopped chemo a month prior and now her time was running

Alberta Pure. I withdrew from a course and considered dropping out entirely. My high school boyfriend dumped me because he “missed the old me.” I called a mental health hotline twice

Words Bernice Wong Design Ericka Zahorszky

Words Bernice Wong Design Ericka Zahorszky

At the end of the term, emails flood into student inboxes with the reminder to fill out teaching evaluations. This is a chance for students to grade their professors’ performance as an educator.

Student Experience of Ins-

truction (SEI) surveys help departments understand students’ academic experiences and are used to grant teaching awards, holding significant influence over instruction.

Student evaluations also impact

reappointment, promotion and tenure decisions.

However, scholars have questioned the accuracy of these surveys, and how they might mask gender, racial and ethnic biases.

These implications are parti-

cularly important at UBC, where only 22 per cent of senior management — deans, associate vice-presidents and others — identify as BIPOC according to the 2022 Employment Equity Report. Currently, 38.5 per cent of UBC Vancouver faculty identifies as racialized.

The UBC Faculty Association (UBCFA) has been vocal on their opinions concerning SEIs.

In a 2019 public statement, it proposed the surveys not to be used when determining promotions of faculty.

“The invalidity of these instruments has been known for a long time,” wrote UBCFA, citing a 2018 arbitration between Toronto Metropolitan University and its faculty association. The arbitrator ordered the institution to stop using student evaluations to make promotion and tenure decisions, stating it had “little usefulness in measuring teaching effectiveness.”

The arbitration noted evidence from expert testimonies and peer-reviewed publications which revealed personal characteristics such as race, accent, gender, age and “attractiveness” could affect the results of student surveys. Other characteristics such as class size and quantitative versus humanities-focused courses could also impact results.

The UBCFA’s most recent statement about SEI surveys was in 2022, where it called them a “cheap candy of teaching metrics.” UBCFA wrote that these surveys are biased against marginalized groups and do not perform their intended purposes.

It entered a contract negotiation with UBC asking the institution to stop using these surveys as summative measures of teaching.

However, the ratification package for the 2022–25 period did not include a change in SEI practices.

The 2022 President’s Task Force on Anti-Racism and Inclusive Excellence Final Report found that “similar to other IBPOC folks, Indigenous graduate student teaching assistants report low teaching evaluations due to implicit bias of predominantly White students.”

The report also said BIPOC faculty members with accents may face negative course evaluations. Ultimately, the report called for student surveys to be removed for being discriminatory.

“Achieving and maintaining equity in employment is a systemic challenge facing many organizations and it’s one UBC takes very seriously,” wrote Associate VP Equity and Inclusion Arig al Shaibah in a statement to The Ubyssey.

She said the university is committed to improving representation across all equity occupational groups while focusing on improving experience and retention.

Currently, the university is “preparing to launch a guide that identifies a series of best practices to enhance equitable search and selection processes and to advance inclusive excellence in hiring.”

In Spring 2019, UBC formed the Student Evaluation of Teaching Working Group (SEoT) to re-examine the university’s approach to student evaluations.

As a collaboration between

UBC Vancouver and UBC Okanagan, the group was chaired by 1 professor from each campus and composed of 15 faculty and student members.

After over a year of consultation, the group published its 16 recommendations in 2020. The group found no systematic differences in aggregate data when examining between female and male instructors, and recommended that the next step be conducting an analysis based on ethnicity.

Work on processing data based on instructor ethnicity is reported to have commenced in 2022.

Dr. Catherine Rawn, professor and associate head of undergraduate affairs in the department of psychology, was among the members of the 2019 SEoT working group.

She acknowledged the biases that arise when examining interactions of gender within disciplines. Marginalized faculty in fields traditionally dominated by white men are especially vulnerable to evaluation bias.

For instance, engineering stands as a traditionally male dominated field. Last year, the Faculty of Applied Science reported that 34 per cent of assistant professors identify as women across both university campuses. A 2019 report from Statistics Canada noted the largest gender gap in STEM enrolment was within engineering programs.

A 2023 study published by the UBC Sauder School of Business shows the business field may also be affected by unconsciously held beliefs about physical appearances and areas of expertise. The results also showed people associate the position of a finance leader with the description of a white male. Currently, 1 of the 6 Sauder finance branch full professors is female and 5 of the 18 full profes-

sors are female.

Similarly, al Shaibah pointed to the important role of disaggregating data to unveil the masked inequalities that may not be visible in the aggregate.

She wrote that a report following up on the interim 2022 Employment Equity Survey Report will include Indigenous, racialized and disabled employees. It will be released in the spring and will report on intersectional data.

However, challenges arise in balancing the act of protecting sensitive information while providing a comprehensive representation.

Rawn also highlighted a potential issue with generalizing the broadly construed literature on student surveys to UBC experiences.

“From a psychological perspective, when we administer the

same survey, and when we want to compare across samples, we administer exactly the same survey in exactly the same way,” she said. This underscores the challenge of comparing across institutions with differing survey structures and methodologies.

As for discussions regarding the presence of SEIs in the realm of reappointments, promotions and tenures, Rawn said it is important to include the student voice in some way.

“I don’t think that the student voice can be the only indicator of teaching but I think it’s an important one,” she said.

“There’s work to be done about how to do that in a fair way that empowers people to identify bias and helps us to protect the faculty members who are most vulnerable.” U

Words Maya Levajac Design Bessie Guo

Words Maya Levajac Design Bessie Guo

Hartford, Connecticut, 1953 — Patient H.M. experienced severe epileptic seizures that could not be controlled by medication. After undergoing experimental neurosurgery, his epilepsy was under control, but with one problem: his ability to recall and form memories had been severely impacted.

H.M. underwent a bilateral medial temporal lobectomy to remove parts of his brain — notably the majority of his hippocampus.

Today, we understand that the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped brain structure, plays a crucial role in memory formation and storage.

Though H.M.’s case helped us gain critical insight into how memory functions, researchers generally can’t just remove parts of people’s brains to learn what happens. That leaves researchers, including those at UBC, with the need to innovate alternative approaches to researching memory formation.

While scientists have made immense progress in memory formation research, so much is still unknown.

What’s keeping us from fully understanding this aspect of the human brain, and what are memory researchers doing to overcome these obstacles?

Do we remember like rats?

Animal modelling is a gold standard method in neuroscience research. It involves using animals to study biological and physiological processes or mimic human diseases and test potential treatments.

Dr. Mark Cembrowski, a UBC cellular and physiological sciences assistant professor, uses a computational approach which integrates diverse datasets to map and interpret the brain while combining behavioural assessments in rodents to investigate memory formation.

Cembrowski said his ultimate goal is to “understand memory in a way that we can treat a variety of debilitating memory-related disorders and diseases, including PTSD, Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.”

The Cembrowski lab’s current research uses rodent models to

study fear memory, the memory of traumatic events that causes fear and avoidance, and recognition memory, the ability to identify a previously encountered stimulus or situation as familiar.

But do rodents form and retain memories in the same way humans do?

According to Cembrowski, the underlying assumption of animal research is “what is going on in this animal model is something that generalizes to humans.”

There are limits to this assumption of translatability between animal models and the human brain, and capturing the complexities of human behaviour in simpler animals can be difficult. However, researchers like Cembrowski are attempting to narrow the gap between animal models and humans.

“We’re starting to be able to show what specifically is different in the brain[s] of humans versus animals,” he said.

Cembrowski and his lab aim to overcome the barriers associated with animal modelling through a new research project in collaboration with Vancouver General Hospital.

The project uses donated brain tissue removed from consenting epilepsy patients. This tissue is then kept alive in Cembrowski’s lab and used to analyze the human brain’s organization on a cellular and molecular level.

By using live, functioning human tissue, they hope to solve the problem of translatability.

“We start from a living human brain [and] identify what we think are really important cells and molecules there for memory, ” said Cembrowski. “[We] test those in rodents, and then if [our hypotheses are correct], then we can then bring this back into clinical trials in humans and hopefully begin to understand and treat memory related impairments.”

“When you can actually start with things like living human brain tissue, there is no need to translate anything.”

A common approach to researching memory formation involves studying it from a cel-

lular perspective, which means looking closely at how individual cells interact and work with each other.

Dr. Jason Snyder, a UBC associate psychology professor, aims to understand the impact of neurogenesis, the production of new brain cells, on memory-related processes. Snyder is particularly interested in investigating memories formed in infancy, their relationship to neurogenesis and their impacts on future behaviour.

One method in cell biology involves researchers expressing genes in specific brain cells. Alterations in gene expression impact what proteins a neuron can manufacture and can have diverse effects on neuronal functioning. These effects range from how efficiently a neuron sends out its messages to what neurotransmitters it can synthesize.

Researchers use genetic tools such as promoters for optogenetic proteins, which activate or inhibit the ion channels neurons use to conduct electrical impulses by shining a specific colour of light onto the neuron

through an implanted optic fibre connected to a laser or LED.

However, different cells require different types of promoters and researchers don’t have genetic tools for every type of brain cell, which can limit how much we can understand about the process of neurogenesis.

“These molecular genetic tools are one of the current things that are really allowing us to identify functions of specific brain regions,” said Snyder.

Historically, researchers utilized chemicals that would overexcite and kill neurons in a brain region for memory research, allowing researchers to analyze how the loss of those neurons affects function, similar to how they studied H.M. following his surgery.

However, issues arose as these neurotoxins were relatively imprecise. New molecular genetic tools allow researchers to overcome this problem.

For example, Synder’s lab uses viruses to specifically infect dividing cells. After an adult animal is injected with one of these viruses, none of their existing

brain cells will be affected. Instead, the viral genes will only occur in the newborn cells, which can be manipulated to visualize their structure.

Imagine you were given a list of words and half of them were relevant to your personal identity and the other half were not. If you were tested on your memory of these words later, you would likely have better memory of the self-relevant words.

This behavioural observation provides some insight into how memory works and, when coupled with brain imaging techniques, shows how the brain supports this aspect of memory.

Dr. Daniela Palombo, an associate psychology professor at UBC, investigates autobiographical memory formation in human participants. Autobiographical memories come from real-life personal events, such

as learning to ride a bike for the first time.

Palombo’s research projects aim to understand how negative emotions impact people’s memories of certain events, as well as how memories can change over time.

Using human participants may be the only option for certain research topics concerning memory formation, such as more complex types of memory like autobiographical memory. However, studying memory formation in humans presents its own challenges.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measures the changes in blood flow to specific brain regions, and researchers can then use this information to make assumptions about human neural activity.

Palombo noted in a statement to The Ubyssey that fMRI “does not tell [researchers] how cells and circuits are operating during remembering versus forgetting.”

“It is not a direct measure of neural activity,” Palombo wrote. “We need other approaches to drill down further if we want to understand mechanisms.”

Palombo’s research combines neuroimaging with behavioural assessments such as autobiographical interviews where participants recall events from various life experiences to get a “richer picture into what and how people remember” and bridge the gaps in each method.

When behavioural output aligns with neural activity, “that might tell us a bit about how the brain supports certain aspects of memory,” wrote Palombo.

Each method has its own strengths and most researchers use a combination of techniques in order to support their findings. Developments in one research method, such as improved brain imaging quality, can ripple out to others to help the entire field of memory research gain further understanding of the mechanisms of memory. U

Words Stella Griffin

Design Andra Chitan & Emilīja Vītols Harrison

Photos Jerry Wong

Aayush Raghuvamshi grew up watching Bollywood movies and imitating the actors on the screen.

Eventually Tiger Shroff, a famous Bollywood star, reposted one of Raghuvamshi’s videos and it went viral.

Raghuvamshi now performs as a breaker with the Unlimited Dance Club at UBC. But it wasn’t until October 2022 that he began tackling new freestyle terrain instead of the set choreography he was comfortable with.

“In the beginning you feel so lost, because you’re just trusting your body to move in a certain way to a [song] you’ve never heard,” Raghuvamshi said.

Now, when Raghuvamshi competes in dance battles, he occasionally pulls out a push-up move that springs him into an aerial 360° twist. But before he could flip in the air, he had to learn the basics.

“Once you’ve learned to just bounce, then you start to add motion … you really trust yourself a little more [to] let yourself move with the music.”

Breaking, or b-boying, has roots in martial arts and gymnastics. Originating in early 1970s New York, breaking is credited to DJ Kool Herc, the first to string together bass-heavy sections of songs and encourage dancers to come forward and express themselves to the beat.

Half a century later, breaking and other hip-hop dances like locking continue to push dancers’ emotional, physical and creative expressions.

Unlimited Dance Club, and its competitive team Project U&G, are initiatives that draw on these

influences.

Project U&G’s marketing coordinator and locker Normey Liu feels most empowered and expressive in performance when she is conveying her passion to an audience. Like Raghuvamshi, she felt nervous for her first battle, but that did not stop her from leaving her comfort zone.

Liu’s mindset stems from the belief that she must continue to push her limits while dancing, because “time will give [her] feedback” with the more effort she puts in.

“I sometimes feel upset before and during dance practices, because I feel like I cannot express the music as I want,” Liu wrote to The Ubyssey. “But after a good session, I [feel] motivated and … want to practice more and get better.”

Although locking and breaking are considered more relaxed styles of dance compared to forms like ballet, the improv and freestyle elements are no less demanding nor limiting mediums.

“[Ballet follows] a very strict guideline of what you’re supposed to do,” said Kshitij Gupta, the Unlimited Dance Club’s president. “There’s a right technique and there’s wrong technique.”

“These differences [between hip-hop and other genres are] not just in the physical movements but also in the philosophies, cultural backgrounds, and expressive freedoms these styles embody,” Project U&G’s locking instructor Kelly Duan wrote to The Ubyssey.

“While classical forms often adhere to strict choreography, [hip-hop] styles encourage dancers to develop their own unique

style and incorporate freestyle elements into their performances,” she wrote.

Duan uses locking to express herself and believes it is the “happiest style of dance.” It brings out the funky side of performers, and inspires character and playfulness.

Unlike classical dance, the audience does not necessarily sit quietly and watch the dancers perform, but rather cheers and encourages the artists to express themselves fully.

And so do the other performers — dancers feed off of each

other and encourage their battling opponents to break through limits, from gymnastic handstands to martial arts windmills.

Hip-hop creates a unique atmosphere where no one is a bystander.

Speaking on the more flexible expression breaking and other hip-hop styles permit in routines, Gupta described a battle he witnessed where “one of the judges [incorporated] movements that would be more traditionally considered house [moves] into her breaking set.” It was something he had not seen in many contemporary sets before.

Although there is freedom in breaking, Gupta pointed to the frustrating limitations he overcame when he stepped away from dance for a couple years in high school. He initially felt disheartened he was no longer at his previous physical level, but that led him on a personal journey to figure out why he sought out dance as a form of expression.

“Do I dance because I want to look cool? Do I dance because it gets me to win competitions? Do I dance because I want to impress someone?” Gupta said. “Or do I dance because that’s what I like to do?”

From his journey, Gupta learned that, ultimately, dance is a tool for self-expression — and “it shouldn’t be anything deeper than that if you don’t want it to be.”

“I’ve never felt like I’ve mastered anything in dance at all,” Raghuvamshi said. “I think that’s kind of beautiful too, because then there [is] always something new for you to explore.” U

In my life, there is a Before and an After.

I was born in a body that would age to hold stories — stories spanning my land and stolen lands, stories spanning my heart and foreign hearts. Swaths of brown skin caged a soul and cushioned a heart that would witness revolutions within my body and outside of it.

You see, being born in a body with a vulva accompanied conditions of existing — conditions meant to keep me in check before I could even pinch a pencil between my stubby fingers.

Conditions were drafted with the notion of keeping my dignity, body and heart safe. Conditions were set because liberation was a threat to the expectations my family held for me.

The knowledge to wield a rolling pin, to roll bread and scrub greasy dishes were essential if I hoped to please my potential husband and his family. My fat thighs with gigantic dark birthmarks, my big nose and lips were seen as “ugly.”

My family also never signed up for my sharp tongue and sharper opinions. Instead, they encouraged a meek attitude and hums of acquiescence — indicators of a sophisticated and appropriate upbringing.

Respect, obedience, sweetness, hard work and compromise were the pillars on which my personhood was to be founded. These values had to be at my core; they would hold my skin tight, my bones together. Without them, I was a loose leaf at the bottom of some man’s teapot, ready to be discarded after he was done sipping on his chaha. But even then — especially then — I wouldn’t be free.

I couldn’t simply be an object — I had to be a prize; always the best, and never in control of my own fate.

On August 30, 2021, I first set my foot on this stolen land called “Vancouver,” convinced there was no eraser strong enough to eradicate the boundaries keeping me hostage, and no glue sticky enough to hold me together.

I was sure that I was watching a movie. I was a bystander in other people’s lives — ones much more interesting than mine, lived by people who ignited my envy for their bodies not caged within limits and boundaries.

But I never forced myself to look past the flesh and the face. I could only see their limbs held together with confidence, hear sharp syllables form witty remarks, arms flung around their buddies, faces and eyes brighter

than my Diwali lanterns. I never looked at the big picture; I simply accepted that they were a model of perfection that I would never reach.

I would have kept wallowing in self-pity had the After not appealed to me more.

This After held promises of independence, freedom, choice, Queerness, friendship,

sex, pleasure and — best of all — a gradual shrinking of selfdoubt and the start of my quest for liberation.

I had always anticipated roadblocks, but there were unprecedented factors I hadn’t considered at all, mostly because I thought I was being too idealistic in dreaming about them: love and community. Two things I grew up believing would be my Achilles heels if I fell head first into them.

I had always been told that interdependence would make me weak and put my heart at risk, so to witness and experience love and community took practice and willingness. I didn’t achieve self-love overnight or have a grand epiphany of all the potential and greatness I held.

The first time I went to a Queer Halloween party, I witnessed love interlocking people’s hands, love tying strangers together, nudging us to share our stories.

Love saw me through the first time I went against my instinct to contain anger and grief, and instead stepped into radical spaces where common values tied yet another group of strangers together. We were fraught with the same hunger for liberation, victims to the same systems of oppression. Yet none of us lacked love for the world.

Once, I wore my low cut pink dress that clung to my tummy rolls and made me not want to breathe or drink lest I look more like a stuffed teddy bear than a Barbie. But not a single

scathing word or barb was hurled in my direction. I was amongst big bodies, midsized bodies. Bodies carrying cellulite and warm smiles and affection and reassuring words.

I felt and witnessed love in these moments. Moments that contradicted my history and subverted my expectations. Moments that were normal to some, but only existed in the After for me.

“The world isn’t full of people out to hurt me, after all,” I thought to myself. “It’s not as harsh, and I don’t always have to be so strong,” I reasoned with my heart.

Moments of tenderness still catch me off guard. For a few seconds I am unsure what to make of them, whether I should allow myself to revel in whatever emotion threatens to overcome me or keep clinging to the fading lines that previously defined me. They’re familiar after all; familiar, but hated.

I loosen my grip on these lines: lines of shame, disgust, woman, more shame. I let myself feel. Let myself love and witness love.

The old lines and limits are not fully faded and

my skin feels the same, but my blood doesn’t. My body is shifting — outlines cracking and realigning, rubbing off, reforming themselves into new ones. The stench of the old boundaries might still cling to my skirt, but I don’t pay them much heed.

I’m still not free. I’m still oscillating between moments of tenderness and the harsh realities of my world. I’m still aware of the ways my body and identity limit what I can do, who I talk to, what they say to me. I’m still aware of my voice cracking when I’m demanding the right to be liberated.

I’m still not free because others aren’t, but because love has tied us together, our freedom shall come together. All the lines caging us will be rubbed off at once.

I’m so much freer than I used to be. I’m holding onto love, toppling cracked walls of oppression, chipping away at constraints of suppression. U

Looking down at the cheering crowd, Michael Dowhaniuk basked in the warm March sun. He had just climbed over a 12foot wall on his first attempt. A couple minutes later, Dominic Janus followed him over.

Our drive to challenge ourselves makes us chase activities that push our physical limits in unique ways — hence, the birth of Storm the Wall.

Every March, thousands of UBC students gather to participate in Storm the Wall and many more gather around the Nest to cheer them on. The annual student tradition requires students swim, bike and run before summiting a 12-foot wall. While the course is mostly attempted in teams, a handful of students decide to attempt the course completely by themselves, aiming to achieve the coveted title of Iron Legend.

Last year, UBC crowned Iron Legends for the first time in four years with both Janus and Dowhaniuk conquering the course alone.

Despite coming from different backgrounds, Janus, a master’s student studying geese in the Faculty of Forestry, and Dowhaniuk, a then civil engineering student and starting outside hitter for

the UBC men’s volleyball team, shared a common desire to test themselves against the wall.

In the past, both attempted the race solo, but only Dowhaniuk succeeded.

In 2019, Janus scraped his fingers along the top of the wall du-

ring a practice session, planting the seed of possibility in his mind.

“I spent an hour just throwing myself at the wall trying to do it by myself and got super close, like I was able to touch the top but I needed another inch or two to be able to hold on,” said Janus.

In 2023, he decided to try again.

“I thought last spring would be my last spring as a student. And I was like, might as well give it another go considering I was really close four years ago and was feeling a little bit in better shape.”

For Dowhaniuk, the thrill of conquering the challenge again appealed to his competitive nature.

“[Iron Legend] is the hardest difficulty given for the event,” said Dowhaniuk. “I want to push myself and test my limits and boundaries. I knew that if I did anything less than the hardest, then I wouldn’t be completely satisfied.”

Both participants approached the event as a personal challenge, seeking to prove their own abilities to themselves. But there is some psychology behind their shared decision to take a second shot at the wall.

Dr. Jeff Sauvé, a UBC Kinesiology PhD graduate and former instructor of PSYC 311, psychology of sport, broke it down in an interview, explaining how humans continuously learn from the past.

According to Sauvé, self-efficacy, or a belief in one’s capabilities to execute a goal, is

based on previous accomplishments. The risks and rewards of previous experiences can “propel [an athlete] to put forth a higher level of effort moving forward.”

“You’ve learned how to persist in the face of failure and you will continue to problem solve when encountering those failures,” he said.

Even though Storm the Wall was not something Janus was “super passionate about,” completing an unfinished challenge from his past and stepping out of his routine had a certain allure and led him to success in the race.

“I wanted to prove to myself that I could do it because I really thought I could,” he said.

Dowhaniuk said he was aware that climbing the wall demanded a large mental effort alongside physical ability and approached the challenge fully believing in himself. He credited his background in volleyball for drilling in him the importance of “the mental side of things.”

“If I had any doubt in myself, I definitely wouldn’t have performed as well,” Dowhaniuk said. “Once I got to the wall, I had no doubt in my mind that I was going to make it over, which definitely helps in that first attempt.”

A huge draw to Storm the Wall is that its physical demands and challenges allow participants to fulfill their basic psychological needs for competence.

Sauvé explained how competence is important for us to feel effective at achieving a desired

outcome.

“Sport provides so many opportunities for an individual to be motivated to work hard, and to achieve those outcomes,” said Sauvé.

Both recently crowned Iron Legends lead active daily lifestyles. Janus said he enjoys lacing up for a casual game of basketball and hitting a couple dunks. Dowhaniuk said he also took up cycling in the last couple years, recently completing the Gran Forno ride from Vancouver to Whistler.

For an elite-level athlete like Dowhaniuk, Storm the Wall and cycling provide ways to challenge himself in ways volleyball does not, creating a heightened sense of gratification.

“The hardest part for me when taking part in these events was the endurance side of things and having to sustain energy for hours at a time,” he said. “It was very difficult, but I accepted that challenge and tried to welcome it with grace even though it hurt a lot.”

Sauvé said it’s common for high-performing athletes to try other sports, adding that “in many ways that can be really helpful and healthy, especially in circumstances where you are measuring yourself against yourself.”

Janus said he expects to give Storm the Wall another go this year, and perhaps even a regular triathlon in the near future, as these activities bring a renewed sense of excitement to his life.

“I’ll think of some way to have more fun with [Storm the Wall] this year. I don’t know. Maybe put a cape on or something.” U

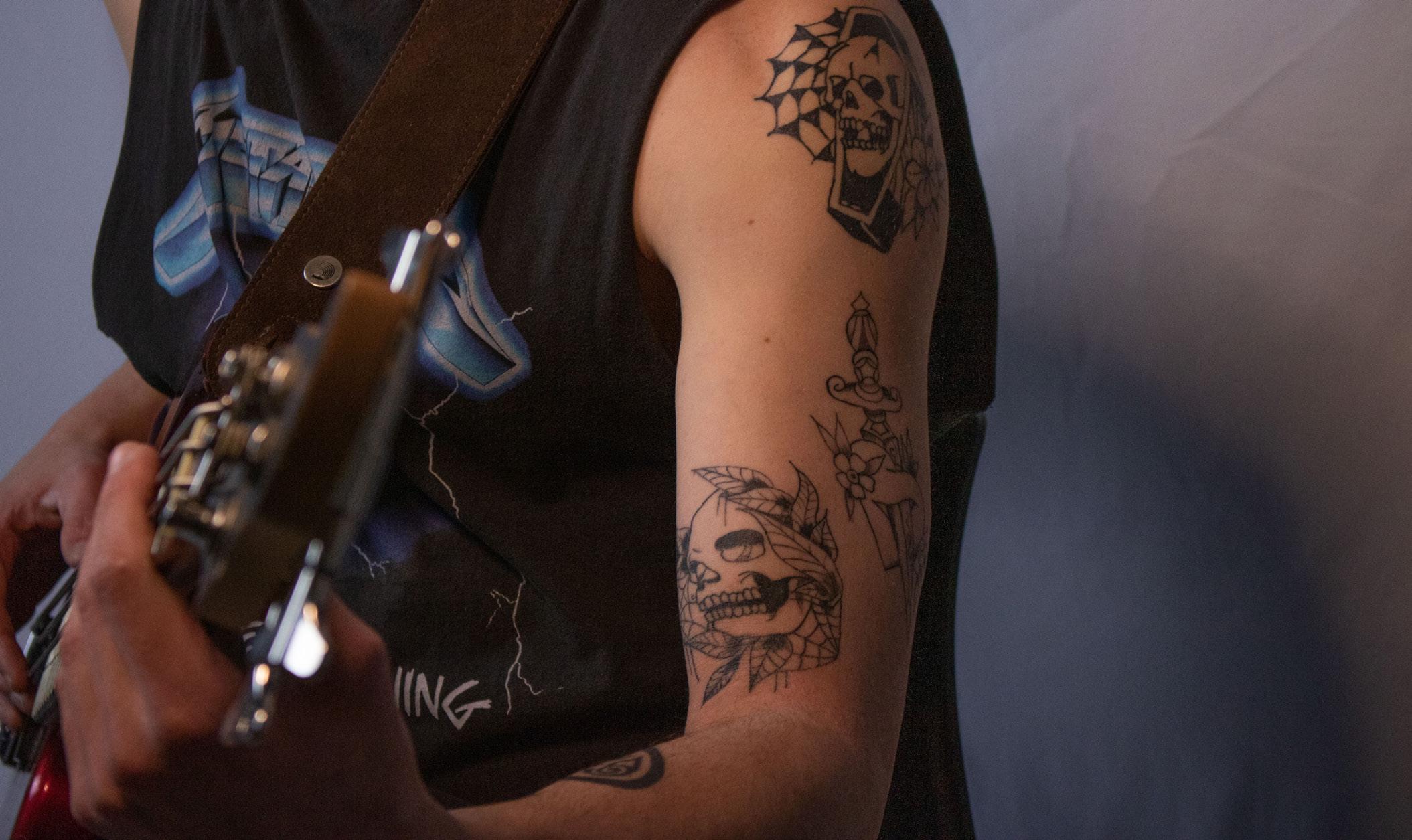

When the North American youth of the late ‘60s were struck with the bleakness of industrialization, the uproaring renaissance of punk and rock followed. Those movements inextricably linked the music and tattoo scenes.

Body adornment was adopted as a way of claiming agency and rejecting mainstream society — including the art that people looked toward.

Like ripples, this mentality folded into the context of Vancouver’s underground music scene.

“I remember being 13 and emo,” said local musician Haleluya Hailu. “I very much looked up to a lot of people from alternative subcultures who were

like, ‘I don’t really care what a person is supposed to necessarily look like, I just want to express myself in a way that feels fun.’”

Emerson Landwehr, a musician and second-year psychology student at UBC, has a colourful free-flowing tattoo parsed into three sections that runs down their torso to their leg. When an artist they admired took up residency in Vancouver, Landwehr took the opportunity to collaborate on the design.

“You know when kids are drawing stuff, they just go for it and they just draw things and it’s not restricted by all of the different norms that we’ve already learned by the time we’ve become adults?” they said. “It kind of

felt like that, except it was obviously … intentional.”

‘All art is expression’

Hailu isn’t bothered that they share the same ‘I heart music’ flash tattoo with other people.

Flash tattoos are pre-drawn, ready-to-go designs that an artist offers. The group of strangers all decided to get this ink design, sharing a “human experience” at Music Waste — a cheeky local annual music festival that was born “as a sort of protest against the more corporate and exclusive Music West festival,” according to Music Waste’s website.

“I think it’s just such a funny [tattoo] because it was just such

a spur of the moment [decision],” Hailu added.

Like photos in a scrapbook, Hailu said each tattoo is associated with a memory and “are super intimate,” they said.

Getting something marked on your skin forever is a big commitment. But that doesn’t bother Landwehr — they enjoy having a visible reminder of who they were and what they liked at different points in their life.

Each of their tattoos include elements that Landwehr designed themselves, which adds another layer of meaning and intentionality to them. The constant presence of the tattoos is helpful while they’re on a stage or in the technicolour crowds of a local venue, where it can be hard to express their feelings.

“It does take a lot of vulnerability to play music or to show your art in some way,” Landwehr

admitted.

“[Performing is] a scary thing for a lot of people, but if you’re in an environment where everyone is doing that very openly, and sharing these very vulnerable pieces of who they are, it becomes a lot easier to see other people as human beings.”

Local musical spaces like Music Waste nourish connection and demonstrations of craft.

Landwehr recalled a series of get-togethers some UBC students hosted last summer that served as an artist marketplace and a safe space to share local crafts.

“There was always a little area where people were getting tattoos or doing tattoos,” Landwehr said. “And there was always also some people doing improvisational music of some kind, and I also improvised with some people there a couple times.”

Not only were there a variety of art forms to engage with — people often jumped between them. After playing a set, someone might head over to their tattoo station to do some flash pieces.

Landwehr got most of their tattoos in the early stages of their involvement in Vancouver’s music scene.

“All art is expression in some way,” they said. “If you have multiple mediums of art, I think it’s easy to, once you get very invested in one of them … also have that creatively influence other things, and it can create a sort of feedback loop.”

It’s a cycle where tattoos are proof of choice, a mosaic canvas of memories and a venture into discomfort.

“I’m so much more open to this idea of experiencing everything good and bad and dirty,

and tattoos are a part of that,” Hailu said. “It’s a little bit uncomfortable. But you’re left with this amazing piece of art at the end and I feel that reflects on my music.”

“I think you’re a lot cooler of a person if you do push yourself to do something that might be a little bit uncomfortable.”

Due to their origin as a form of rebellion, tattoos are still taboo in some spaces, particularly in the workplace. However, many are gradually learning to accept — or even encourage — these displays of creative expression, especially in the indie music scene.

But this mindset change is taking longer to unfold in more traditional art forms.

“In the classical music world, there’s definitely still that element of uncertainty,” said Dr. Robert Komaniecki, a UBC music theory lecturer.

“If a student is an opera singer, and they want to pursue a career in opera, there is hesitation about getting visible tattoos because if you are performing … and the opera is set in the time it was composed, then people might not want you to have a big lizard tattooed on your forearm.”

Though perceptions are changing in the classical music industry as more people look to express themselves through body art, tattoo placement is still a consideration classical musi-

cians take into account when compared to their alternative cousins.

“People are worried about making themselves a liability to be employed,” Komaniecki said.

Third-year vocal performance student Sofia Culjak-Wade was conscious of where she decided to place her first tattoo — a custom design of the star tarot card signifying hope. One of her concerns was that if it was in a highly visible spot like her arms, it might impact the way she’s perceived during auditions, and she’d be forced to cover it up while singing.

“Even though things are a lot more progressive now, you don’t know who is casting,” said Culjak-Wade. ”You don’t know who’s behind that desk, and just

on the off chance that maybe it might affect how the outcome of your audition goes, because competition is high for roles, people cover it up.”

But as opera explores edgier tangents, it seems possible that the industry’s perceptions might evolve to allow for more expression — or at the very least, more willingness to accept tattooed singers under the condition that they hide their body art.

“I love tattoos,” said CuljakWade. “I love seeing tattoos on people and what people get.

“If the singer is okay to put makeup on or wear longer sleeves, then it’s nothing that can’t be fixed by costuming if you do want a more traditional look — by all means, singers, go crazy.”

Music in all its genres and forms isn’t perfectly replicable. Each performance sounds a little different, every song has its nuances and all artists have their own little quirks.

Landwehr doesn’t quite know how to place their musical style, but believes it could best fit under something like jazz. To them, it’s not a genre as much as it is “an umbrella term for a bunch of different stuff that stems from the same underlying systems in some ways.”

Similar to music, Landwehr views their tattoos and the meaning behind them as a mosaic.

“I’m not sure if I can always describe what it means to me emotionally,” they said. “I don’t think it necessarily has to have any meaning for me past [being] something that I’ve chosen intentionally and that in some way represents a period of my life. I’m happy with the fact that [it’s] something I can always access wherever I am.”

Having music as an outlet to mess around with under low stakes molds a transient self-identity and style, but it’s nice to have something like a tattoo that stays constant.

“Tattoos are kind of the polar opposite [of music] … one can

be that very permanent form of expression, the other isn’t,” Landwehr said. “I think people like having a combination of the two — they balance each other out.” U

One week before my nana died, I spent the night with her.

Nights weren’t typically my responsibility. We all took turns caring for her — spending the night had fallen to my nonno, while my mom and I would shower her and keep her company, ensuring she got her chemotherapy pills and went to radiation everyday.

As I helped her back into bed that night, I looked at my nonno’s face and saw exhaustion like I had never seen before. He’d always looked younger than he was, but over the past three months, he seemed to have aged 10 years.

When my nana was first diagnosed with stage 4 brain cancer, we knew keeping her at home would be difficult. But in the middle of a pandemic, we didn’t want to put her into a facility where visitation restrictions could stop us from seeing her if she took a turn for the worse.

We had underestimated the toll that brain cancer could take on a person — being worn down by treatment was one thing, but now that the cancer had progressed, she could barely speak, was no longer able to recognize

anyone in our family and called out for her long-dead mother constantly.

Tonight, though, she seemed better. Showering was easy, and when I stood behind her blow-drying her hair, she leaned back into me and closed her eyes, so peaceful for just a moment.

After we fed her dinner and my mom started to pack up, I took one more look at the bags under my nonno’s eyes and decided I would stay with my nana so he could sleep in the guest room. He quickly gave in.

I had always been my nana’s special grandchild, the one she called her second daughter. I was sure it would be okay.

I hugged my mom goodbye and sent my nonno off for an early bedtime. Then I settled into bed with my nana. This was a familiar feeling — when I was a kid, my mom would drop me off at my grandparents’ house early in the morning, and I’d crawl into bed while my nana was still sleeping. When she woke up, we would watch Heartland on the TV together until the sun was halfway across the sky.

As I laid on her bed that

night, my nana was quiet, making it easier to pretend for just a few minutes that the cancer was gone, that I was just there to watch our favourite shows together again.

The bird-themed clock that hung on the far wall of the room hit 11 p.m., a small black-and-white bird’s call marking the late-night hour. I felt myself begin to fall asleep. I checked on my nana one last time, then settled onto my side of the bed.

“Mama! Mama!” I woke up with a start. My nana was frantically calling out for her mother, startling me from the thin veil of sleep.

I held her hand and smoothed her hair until she quieted down, closing her eyes and settling her head back onto the pillow again. I laid back down on mine and closed my eyes.

“Mama! Mama!” I felt my body jerk from sleep again, panicking that something was wrong as her shouts rang through the room. I sat up, ran my hand down her arm, spoke some quiet comforts to her and held her hand until she laid her head back down and closed her eyes again.

Over the next 5 hours, I woke up every 10 minutes

to help her settle down. As a full-time undergraduate student working a full-time job and spending every free minute I had with my nana, my body was desperate for rest. Every time she shouted and I could do nothing to help, I felt myself inch closer to tears.

When the clock hit 4 a.m., I hit my breaking point. My eyes burned so badly tears dripped down my cheeks, and my body ached. My nana had always been the closest person to me; now she didn’t even know it was me laying next to her, trying to calm her down.

To her, I’d become a faceless person muttering incoherent comforts. In the darkness of her bedroom and the otherwise silent night, the full extent of her illness hit me in a steadily building wave, climbing higher with each shout.

“Mama! Mama!” Instead of reaching for her, I tipped my head back and closed my eyes, pushing back the stinging tears. In my desperation, I picked up my phone and called home.

My mom picked up on the third ring, her voice hoarse from sleep, but panic lining her tone. As I tried to open my mouth and tell her what was wrong, my nana began to call out again, crushing any chance that my mom would hear my words. When I opened my mouth, all I could do was sob.

Through my crying and my nana’s shouting in the background, I told my mom I couldn’t do it, I couldn’t comfort her, I couldn’t calm her down, I couldn’t help her, I was so, so tired. Tired in my bones and in my heart.

At 6 a.m., I laid in bed simply staring at the ceiling, holding her hand and watching orange hues from the sunrise play across the white paint. The exhaustion that lined my nonno’s face suddenly made perfect sense. He likely spent every night like this one, never getting more than 10 minutes of rest.

I felt like I was giving up on a fight I didn’t know I’d entered, giving up on the feeble hope I had always carried — I thought that because I loved my nana so much, I could handle taking care of her no matter how sick she got. As long as I was with her, I could power through the exhaustion and the pain and the heartbreak of losing her. But she wasn’t getting any better, and it made no difference to her that it had been me laying with her all night.

Two days later, an overnight personal support worker came to the house. I watched as she settled into a chair beside my nana’s bed and pulled out a book to read to her, leaving my nonno to make his way to the guest room to get a full night’s rest. I hovered in the doorway, my stomach in knots.

I knew it was the right

decision, because we were all burning out. The woman we had loved was gone, and now someone had to watch her 24/7 to ensure she didn’t try to get out of bed and fall, didn’t drink or eat something she wasn’t supposed to. We had to spoon-feed her and help her to the bathroom, on top of all of us working full-time jobs and having our own families — and in my case, a fully functioning farm with multiple horses — to take care of.

Still, the guilt threatened to suffocate me, telling me I should be the one staying with her even though it had led to me breaking down.

That night, I laid in bed and was almost as sleepless as I had been the night before. I tossed and turned for hours, wondering if she was being cared for properly, if she was stressed or scared. Eventually, sleep dragged me under, and when I woke up, I had slept through my alarm.

When I returned to the house in the morning, I thanked the support worker and found my nana asleep. My eyes didn’t burn, and when I laid down beside her, it didn’t make me jump when she called out, “Mama! Mama!”

I held her hand and smoothed her hair. I put on our favourite show, content to watch Heartland with my nana until the sun was halfway across the sky, even if she didn’t know. U

my mother’s advice:

‘there is no box’ was meant to be kind don’t limit yourself your dreams your capabilities you can be anything, do anything the world is yours but the possibilities are paralyzing being a biologist means not being a welder means being a corporate girl means not being a farmer

if i’m the perfect friend, i’m not the perfect daughter but then i’m the perfect colleague and not the perfect student

then who am i supposed to be?

trying to do it all is unrealistic

the only one who told me that is burnout

how do you choose who you are supposed to be?

who you are?

limits exist for a reason why shouldn’t i lean into mine? why shouldn’t i be happy?

so maybe after all there is a box a box shaped like me U

I hate to love Vancouver rain.

It makes everything smell like decay.

It rots dirt fissures into muddy pools, But it’s consistent.

I watched the clouds tumbling overhead last spring.

The weatherman casted a wall to wall shower for the last two weeks of March, So, breath suspended, I snuck a glance out my window after fourteen sleeps

To see the gray overcast flit over the inlet, rolling goodbyes, salutations from the sun, Just like the last prognosis

I trusted, steadying,

Weaning off of heart palpitations, shallow inhales and perspiration in a cold room.

I was healing beside myself in solus

And now I wonder why this love can’t be like Vancouver rain.

You yank forget-me-nots from the Earth by the root

And wait for seeds to manifest somewhere that has wanted water.

Dandelion diatribes for edelweiss embraces.

Their petals bloom and shrivel through a pseudo-season known only to you.

You swear my distance —

A void growing inward and out

— Will mark the last time

You care to harvest this garden.

We came to a head when second guesses began to swallow me whole:

We reached a breaking point when I watched the sun sizzle a field I was convinced I drowned. I want to trust that this love can make my forget-me-nots as green as Vancouver rain can, But it’s marred with something toxic.

And we still drink it up,

And we still remember to forget.

A gag forward — I spat out this rainwater for the first time yesterday, tired and sick, Some motion I promised myself would become a reflex.

You, reader, tending to your crops: do you follow?

I’m sorry that you do, that was my intention; I know you well.

A funny thing about Vancouver rain — soon, it’ll drive me out of this town

For tending to a garden, for showing myself imperfect security. U

As you wander through dazzling carpets of flowers on a sunny day, there comes a gentle buzz from afar. A fuzzy honey bee lands on a blossoming flower and indulges in its sweet nectar, hoping to nourish the colony. By the cabbage patches, white butterflies flutter, their bright wings glimmering in the sunlight.

With the climate crisis, however, insects are facing significant challenges. Rising temperatures can have broad effects on insects’ bodies, leading to physiological and ecological disruptions with long-term effects on the human population according to UBC entomologists.

The Pacific Northwest heatwave of 2021 saw the highest Canadian temperature on record at 49.6°C and devastated several insect species, notably honey bees.

In a normal hive, honey bees rely on a healthy queen bee, the only female in a colony that can reproduce. The queen bee mates with many male bees — drones — to produce fertilized eggs, which become workers or young queen bees that maintain the population.

“Even in more northern latitudes, like [BC], the temperatures can get hot enough to pass

into [the] danger zone, beyond which we expect the bees’ fertility to suffer,” said Dr. Alison McAfee, a postdoctoral fellow at UBC’s Michael Smith Laboratories whose research focuses on honey bees’ reproductive health.

Through a series of experiments, she found that half of the drones would die from heat stress after six hours in 42°C — a lower temperature than what was recorded during the 2021 heatwave.

The details are grim: when a drone dies from overheating, it convulses, forcefully ejaculating its endophallus (bee penis) out of its body.

Rising temperatures also decrease sperm viability. As queens mate early in their lives, they store the sperm for years in a specialized organ called the spermatheca. A lack of sperm viability means that queens are less productive, leading to smaller colonies.

After experimenting with the impact of heat on sperm viability, McAfee estimated that the viability of the stored sperm starts to decrease at around 38°C.

The drones’ and queens’ ability to tolerate heat also differ considerably. While half of the drones died after six hours of exposure to 42°C, almost none of the queens died.

“It [is] harder to study how

the high temperatures are affecting [drones’] sperm, because it’s difficult to separate if the sperm are dying because the individual is dying, or if the sperm

are dying because those specific cells are reaching their heat threshold,” said McAfee.

While matter usually expands with heat (like a balloon), rising temperatures have been shown to have the opposite effect on insects’ bodies.

Dr. Michelle Tseng, a UBC assistant zoology professor, is concerned about warmer temperatures reducing the size of certain insects.

“Let’s say your house is warmer than my house, and you take a bunch of baby beetles and I take a bunch,” said Tseng. “[The] ones that grow up in your house and turn into adult beetles are going to be smaller as adults than the ones that I

grew up in my house. [That’s] a pattern that we know exists across most insects.”

This decrease in size impacts an insect’s ability to find food. For example, bigger mosquitoes can collect more blood and bigger bumblebees can travel further to access more types of flowers, so smaller insects are at a disadvantage when compared to their larger counterparts.

Tseng’s research also focuses on changes in phenology — the timing of when insects emerge in spring or summer after hibernation.

The cabbage white butterfly is usually seen flying around cabbage plants in the summer. Previous studies have shown that cabbage white butterflies are emerging in spring, much earlier than usual, due to warmer temperatures.

Although early emergence

can be advantageous for some butterflies, giving them more time to search for food at warmer temperatures, Tseng is unsure whether these temperature-induced changes will be beneficial in the long run.

“There’s a limit to the temperatures that insects can withstand, and different insects have different coping mechanisms for hot weather. If we have these extreme heat events, are we going to have the same set of winners and losers? I don’t think we know that answer yet,” Tseng said.

Researchers are taking action to improve the well-being of insects amid global warming.

One example is Tseng’s Campus Trees, Microbes and Insects project, which assesses how insect diversity is related to the species of trees planted around campus.

The researchers provide valuable information on the suitable selection of urban trees to support insects and cities during climate change.

Around the world, scientists and beekeepers from different climates are collaborating to protect insect populations. Beekeepers in hotter climates, such as southern California or Australia, wrap beehives in insulation and install shade nets to protect the bees from excessive heat.

Many beekeepers also are crossbreeding heat-tolerant bees with species vulnerable to hotter climates to strengthen protection during heatwaves.

However, creating more heat-tolerant insects is not the ultimate solution for addressing the effects of climate change since there are always tradeoffs. McAfee noted bees more adapted to hot climates tend to produce less honey, which may reduce the desired output for farmers. Moving forward, farmers will have to balance maximizing crop growth with the bees’ ability to cope with climate change.

Even so, McAfee emphasized the need for more climate change resistant insects.

“Honey bees that most beekeepers are keeping are like dairy cows, but we need something more like a goat … robust and [less] vulnerable to [these] factors.” U

Photos Annie Di Giovanni, Iman Janmohamed, Lauren Kasowski & Maya Rochon

When you bump shoulders with someone in the halls, you think What’s their problem? You don’t know they just learned they failed their midterm.

When a bear bothers you in the woods, you think What are they doing here? even though you’re the one in the bear’s home.

When cracked plastic hits the garbage, you think Oh well not realizing the journey it will go on from the recycling bin to a fish’s stomach.

Humans seem to only ever think about ourselves. Why are we only ever thinking about ourselves?

Maybe it’s time to shift points of view. U

Growing up in the Renfrew-Collingwood area of Vancouver, fourth-year geography and urban studies student Philip Vargas and his mom knew where to find real corn tortillas, a staple of his family’s central Mexican cuisine. They always shopped at the same store: Los Guerreros.

“We would go to the Safeway to get the stuff that’s commonly available,” said Vargas. “And then we’d go across the street to that store to get our stuff that makes Mexican food Mexican.”

He would wander the aisles for queso fresco, serrano chiles and paleta payasos — chocolate

marshmallows on sticks wrapped in the logo of a smiling clown.

That changed when he moved to Dunbar to be closer to UBC, a 40-minute R4 ride away from the supermarkets he grew up with.

“I haven’t been able to cook as much Mexican food, just using a little very white-washed stuff from the Save-On [Foods],” said Vargas. “So I’ve just been getting stuff from restaurants, which is expensive.”

Vargas is one of many UBC students who have to choose between culture and convenience in a rising food affordability crisis.

Food traditions connect people to their homes, their histories and to each other. But many students said their options for affordable culturally-specific food — from seasonings and good tortillas to certified kosher meals — are slim.

How do UBC students access the food they need to not only stay alive, but to feel like themselves?

For fourth-year geography student Lukas Troni, grocery store trips and shared meals with friends help him enjoy his

favourite Chilean and Mexican foods.

“With my friends, there are Latin grocery stores that we go to where we can find the ingredients and then try to replicate recipes,” said Troni. “That’s something that I’ve been doing a lot for the past few years because [it] really connects me to home and to culture.”

Troni said Chilean food is characterized by fresh seafood and produce from the country’s long, abundant coastline, like caldillo de congrio (a fish stew) and machas a la parmesana (razor clams stuffed with parmesan cheese). A hemisphere away, Vancouver’s seafood doesn’t taste the same and Chilean restaurants are few and far between.

Troni and Vargas both pointed out that Vancouver isn’t known for its Latin American food scene. As per 2021 census data, only two per cent of the city’s population identifies as Latin American.

Still, many international supermarkets follow the demand to stock foods that reflect the multicultural makeup of their neighborhoods. 62 per cent of Renfrew-Collingwood, where Vargas’s favourite markets are located, is comprised of first-generation immigrants as per the 2016 census, with the majority coming from the Philippines, China and South Korea.

“Chinese grocery stores actually helped my family out because they had cheaper local organic produce,” said Vargas. “And they had some Mexican foods … I don’t know why, but they just had them.”

Vargas said that as a child, this sometimes caused the lines between cuisines to blur. He

assumed that dragon fruit came from Asia since he always saw their magenta spikes at Chinese groceries beside lychees and pomelos. But while dragon fruit, also known as pitaya, is widely cultivated in South Asia, Vargas said he’s since learned that they actually originated in Mesoamerica, domesticated by ancient Mayans and Aztecs.

Histories of migration shape food just like they shape people.

Vancouver immigrant food producers had to cope with food systems designed to exploit them, according to reporting from Tyee journalist Christopher Cheung. To adapt, they started producing the foods they missed from home, opened grocery stores and stocked the shelves with international products — from paneer to pitaya — that white grocers wouldn’t.

Many UBC students, both local and international, benefit from their persistence — when they can access it.

For first-year students living in residence, food options often are determined by the meal plan.

“We have 4,600 students on the first-year mandatory meal plan, and they’re from all over the world,” said UBC Food Services Culinary Director David Speight. “So it’s a big task to please as many people as possible among the fiscal and environmental requirements we have in our kitchens.”

Fifth-year English literature student Gurnoor Powar found living on campus difficult because she felt disconnected from her Indian culture, best conveyed through food. Her fa-

vourite is jalebis, orange spirals of dough soaked in sweet syrup.

“I get most of my joy out of food,” said Powar. “So when I was on campus, I was incredibly depressed.”

For Powar, cooking Indian food is an important part of her life. There is limited access to authentic Indian ingredients and

quality food options on campus, and most Indian grocery stores are distant — the closest ones are in Punjabi Market, a 40-minute commute away on the R4 or 49 bus line.

“When I was on campus, I rarely had Indian food,” said Powar. “And if I had Indian food, it was horrible.”

Powar resorted to buying non-perishable food and even depended on her family to bring grocery items for her from Surrey.

“My parents would go out of their way to drive all the way to Vancouver and give me groceries so I could make food,” said Powar. “A lot of the times I would ask them, ‘Can you bring me this or that … chole bhature or jalebis if you have time?’”

An important part of food is sharing it. But living alone on campus made that difficult for Powar, who said it was a very “isolating experience.”

“It was so depressing to make a cup of chai and then just look around and be alone,” said Powar.

Meanwhile, some commuter students have the benefit of home-cooked meals, easier access to family recipes and a un(limited)

pantry stocked with necessary ingredients.

“Some students are living at home with their families, where they may have less autonomy over food choices, [especially] if there are still others in the household doing the shopping and cooking and the choosing,” said UBC food, nutrition and health professor Dr. Jennifer Black.

“Others are living on their own, in residence or off campus and … creating new lives, identities and traditions. I don’t think there’s one path that reflects how students do that.”

Powar eventually decided to move back home.

“I moved out finally, and I realized a big part of why I was so sad was because [of] the food.”

Speight said UBC Food Services has been working to centre cultural diversity in their menu planning. They partner with local purveyors like Indian Pantry for Indian seasonings and Grandpa J’s for Greek spices, and aim to put together menus that “[provide] food from many places around the world.”

Still, no matter where the food comes from, it has a growing cost.

“Regardless of the cultural appro-

priateness of the food … the financial requirements of students is always a challenge for us,” said Speight.

As the cost of living in Vancouver increases, UBC students struggle to afford food. According to the 2022 UBC Undergraduate Experience Survey, 90 per cent of domestic respondents and 85 per cent of international respondents expressed concern about affording food in the academic year.

Food security isn’t only about getting the calories necessary for survival. According to Black, access to food that connects people to their sense of culture, community and home also impacts health.

“Many of our preferences are shaped not only by our biological and physiological needs, for calories and nutrients, but also the meaning and symbolism of food in our lives,” said Black. “And many of those processes are learned from our earliest times in childhood, and through our community experiences.”

10 per cent of AMS 2022 Academic Experience Survey respondents expressed concern about the limited accessibility of culturally appropriate foods on campus.

“Even if you’re filled nutritionally, if you don’t have foods that are culturally important to you or foods from your people, you’re still gonna be physically unhealthy because you’re not eating the foods that you enjoy,” said Vargas.

This is especially important for many Indigenous communities. Colonial land theft and assimilationist policies attempted to destroy traditional Indigenous foodways, and environmental degradation threatens them further. Accessing traditional food is often a form of healing.

46 per cent of Indigenous respondents to the 2023 AMS Academic Experience Survey reported worrying about access to food in the past year — a disproportionately high number compared to the 38 per cent of students experiencing food insecurity overall.

At UBC, spaces like xʷc ic əsəm, the Indigenous Health Research and Education

Garden at UBC Farm, grow culturally-relevant plants and me-

dicine for Indigenous communities on and off campus.

They highlight xʷməθkʷəy əm (Musqueam) foodways through plants like salal and salmonberries, as well as Indigenous food and medicine from other territories, such as sacred tobacco.

UBC and the AMS offer several resources for those struggling with food insecurity like the AMS Food Bank and the Food Hub Market.

The Food Bank is the most used AMS service, with 16,248 user interactions in the 2022/23 academic year and over 600 students served per week. The disproportionate majority of users are international students and graduate students.

“Food banks are where we need these foods the most,” said Vargas. “If you’re already facing financial troubles, and you’re also not able to access the food that you need and that you want, you’re just gonna not be very happy.”

“For me, food is happiness — I get depressed when I can’t have the food that I like.”

But this organization’s ability to meet UBC’s food needs, let alone culturally-appropriately, is limited.

According to AMS Senior Manager Student Services Kathleen Simpson, their capacity for expanding their selection to include ingredients beyond Canadian staples is limited by the funding UBC and the AMS allocates — and the Food Bank has seen consistent budget shortfalls.

They try to take user preference into account through

surveys and inventories of what foods run out first.

“I think that both rice and tofu, frankly, were important steps in having more cultural diversity in the items that we were offering,” said Simpson.

UBC’s Food Hub Market in the Centre for Interactive Research and Sustainability (CIRS) is another initiative that aims to provide low-cost food in a way that supports user choice and dignity. It’s run by students and funded through the Food Security Initiative.

“The Market’s emphasis on culturally diverse and plantforward foods, along with the interactive whiteboard for shop per requests, reflects a proac tive approach to catering to the diverse dietary preferences and cultural backgrounds of the UBC community,” wrote UBC Health Equity, Promotion and Education Director Levonne Abshire in a statement to Ubyssey.

Around the grocery shelves of fresh produce, teas, cans of tomatoes and coconut milk, tables and chairs are set up for students to chat or study after shopping. The cafe-like atmosphere is an effort to combat the stig ma often associated with accessing food assistance and to promote community around the market.

‘That’s how I like to show my love’

Beyond those chairs in CIRS, UBC students make the effort to gather around tables that nouri sh them physically and socially.

“I’ve surrounded myself with a lot of people that really do give

great importance and appreciation to food and how it connects to culture, and to community as well,” said Troni.

Powar regularly takes her friends to Surrey to enjoy Indian food, especially Punjabi food.

“They can’t get to that type of food usually because they don’t have a car. So I pick them up, drive them all the way to Surrey and I drive them all the way back,” said Powar. “That’s how I

A split second is all it takes to define weeks, months or even years of an athletic career. The life-altering impact of an injury arrives not only unwanted, but also unexpected.

Perhaps no one knows that bet ter than UBC men’s hockey player Jake Kryski.

The play began just like any other for Kryski, simply dumping the puck off to start a line change. But, this routine play he had done a thousand times before took a devastating turn.

“It was quite a minor hit — I didn’t even fall down or anything,” said Kryski. “One of their guys was changing right when [the in jury] happened. I didn’t really see him, and then he hit me from my right side. I put all my weight on my left leg, and I felt a weird feeling that I never really felt before.”

The weird feeling was a torn ACL in Kryski’s knee, which would sideline him for the remainder of the 2021/22 season and the first half of the 2022/23 season. While he eventually returned to the ice, viewing his journey as a straight line to recovery is a disservice to the turbulent and lengthy process that he and many other injured athletes have to endure.

better, and you’re doing a little bit more, and things are really going great,” Trainor said. “Then you tweak something or it’s not holding up as well. Then all of a sudden, your thoughts are like, ‘Oh my God, this is all for nothing.’”

Former Thunderbird track and field athlete Glynis Sim is all too familiar with that feeling. She started her collegiate career at Arizona State University where, during the first few years, she dealt with chronic stress injuries in her tibias. While her initial

the sport that played such a key part of her life was gone.

“I was there to get an education, but I was [also] there to run, and at a high level. It felt like the end of the world at that point, and there was no support after I was finished on the team there,” said Sim.

Lack of support, like Sim experienced at ASU, can be detrimental for injured athletes.

Going from an environment that is highly team-oriented to experiencing an intimately personal struggle can be extremely isola-

you watch all your other friends and teammates do the actual things they have to do. Sometimes you feel like you’re not doing enough, even though you know

school or personal lives, and also focuses on goal-setting as part of the recovery.

According to Johns, self-worth as an athlete is heavily tied to

if you’re not getting anywhere. Just take some time; you’ll get there eventually or you’ll find a new normal and things will be okay.” U

If you follow an AMS Elections cycle, one thing becomes clear — the AMS is a lot of things. It’s a lobbying organization, a student union, a non-profit and a manager of over 300 clubs. And students always want it to do more.

At a glance, the AMS works a lot like a public body. It represents close to 60,000 members, a bigger population than all but 9 cities in BC. It provides wide-ranging services, including health and dental plans, recreation spaces and a food bank.

But look at the AMS from another angle, and it’s a small business owner trying to turn a profit.

While the AMS has been running a deficit, its student leaders and permanent staff will tell you they are working to find ways to keep it profitable.

So, is the AMS a student government or a student business? The answer, on paper, is neither.

The AMS is primarily governed by the BC Societies Act, which regulates non-profit institutions with benevolent goals. The student society qualifies under the act because it “repre -

sents the interests” of a student body.

To a lesser extent, the AMS is governed by the University Act, which formalizes the relationship between the AMS and UBC. Most importantly, UBC collects fees for the AMS — mostly through the non-tuition fees students pay at the beginning of each academic year.

In less legal terms, interim AMS President Ben Du wrote in a statement to The Ubyssey that the “core purpose of the AMS is to serve students.”

But student interests have

changed dramatically since the AMS’s inception.

When the AMS was established in 1915, it was more similar to your high school student council than to the institution that we now know. In UBC’s first academic year, the AMS was entirely run by 10 council members who coordinated everything from event planning to communications.

The organization had no

legal structure outside the university. UBC even approved all AMS meeting minutes for the first six years it existed.

Slowly, the AMS began to set out on its own. It became an independent society in 1928 so students could raise money for a new gymnasium.

In the late 1920s, the AMS hired a general manager (now known as the managing director) to keep its growing funds in order — not a student, but a permanent staff member.

This was the start of a gradual process of “professionalization” in the society, according to AMS Archivist Sheldon Goldfarb.