SUMMER 2016 CONNECTING ALUMNI, FRIENDS AND COMMUNITY JACOBS SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY AT BUFFALO

UB Medicine

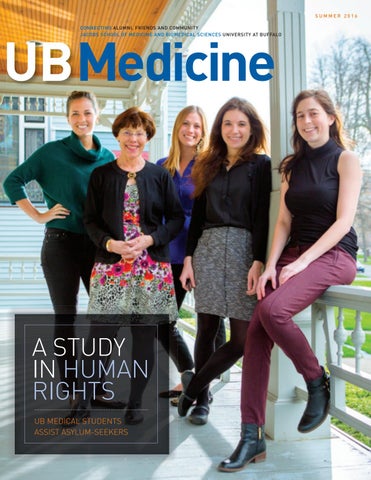

A STUDY IN HUMAN RIGHTS UB MEDICAL STUDENTS ASSIST ASYLUM-SEEKERS

THE EXCITEMENT IS BUILDING The Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences recently celebrated a major milestone in the construction of its new downtown medical school building: the signing and raising of one of the structure’s final steel beams. The beam put in place during the topping out ceremony represented the final piece of more than 7,000 tons of steel used in framing the massive building at Washington and High streets. With eight floors and 628,000 square feet of space, the completed building will be a major Buffalo landmark. Turn to page 4 to read more.

TA B L E O F C O N T E N T S

UBMEDICINE

UB MEDICINE MAGAZINE, Summer 2016, Vol. 4, No. 2

3

Michael E. Cain, MD Vice President for Health Sciences and Dean, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences Eric C. Alcott Senior Associate Dean, Executive Director Medical Philanthropy and Alumni Engagement

VITAL LINES Progress notes

22 26

Editorial Director Christine Fontaneda Assistant Dean, Senior Director Medical Philanthropy and Alumni Engagement

COLLABORATIONS Partnerships at Work

Editor Stephanie A. Unger Contributing Writers Colleen Karuza, Mark Sommer, Lori Ferguson, John DellaContrada Mary Cochrane, Ellen Goldbaum

DOCTOR VISITS 5HĂ€HFWLRQV RQ FDUHHUV

Art Direction & Design Karen Lichner

3

32 Q & A

Conversations with experts

www.facebook.com/ UBMedicalAlumniAssociation

COVER IMAGE: Founders of the UB Human Rights Initiative, left to right: Kathleen Soltis, Lauren Jepson, Kim Griswold (faculty advisor), Sarah Riley, Rachel Engelberg. Photo by Douglas Levere.

Polity President Rahul Kapoor, second from the left, and e-board members Chelsea Recor, left, and Thomas Zavrel, right, Class of 2018, presented Jeremy M. Jacobs, chairman of Delaware North and longtime supporter of UB, with the inaugural Polity Award. The award was established to thank individuals whose work has had a lasting impact on the lives of UB medical students. Last year, Jacobs gave $30 million to the UB School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. In recognition of his tremendous service and generosity to the university, the school was named the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. The students presented the award to Jacobs at Delaware North’s new headquarters at 250 Delaware Ave. in downtown Buffalo.

Photography Joseph Cascio, Philip J. Cavuoto, Sandra Kicman, Douglas Levere

People in the news

Visit us: medicine.buffalo.edu/alumni

JACOBS PRESENTED INAUGURAL STUDENT POLITY AWARD

Copyeditor Tom Putnam

28 PATHWAYS

UB Medicine is published by the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB to inform alumni, friends and community about the school’s pivotal role in medical education, research and advanced patient care in Buffalo, Western New York and beyond.

U B M E D V I TA L L I N E S

Megan Jones, PhD ’16, microbiology and immunology, celebrating graduation day with her mentor, Timothy Murphy, MD, SUNY Distinguished Professor and senior associate dean for clinical and translational research. Jones is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the UB School of Dental Medicine.

10 A Study in Human Rights

8% PHGLFDO VWXGHQWV HVWDEOLVK D SURJUDP WR DVVLVW DV\OXP VHHNHUV LQ RXU FRPPXQLW\ ZKR DUH ÀHHLQJ KRUUL¿F FRQGLWLRQV

14 TOGETHER WE CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE

7HUHVD 4XDWWULQ 0' DQG KHU WHDP FROODERUDWH ZLWK FRPPXQLW\ SK\VLFLDQV WR DGYDQFH FDUH IRU FKLOGKRRG GLDEHWHV DQG REHVLW\

18 NOT AN EASY OPTION TO WEIGH

$ SLRQHHU LQ EDULDWULF VXUJHU\ IRU VHYHUHO\ REHVH DGROHVFHQWV MRLQV WKH -DFREVÂś IDFXOW\ FR OHDGV QDWLRQDO 1,+ IXQGHG VWXG\

Editorial Advisers John J. Bodkin II, MD ’76 Elizabeth A. Repasky, PhD ’81 AfďŹ liated Teaching Hospitals Erie County Medical Center Roswell Park Cancer Institute Veterans Affairs Western New York Healthcare System Kaleida Health Buffalo General Medical Center Gates Vascular Institute Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo Millard Fillmore Suburban Hospital

GRADUATION DAY 2016! The Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences held its 170th commencement on April 29 in the Center for the Arts on the UB North Campus. During the ceremony, 143 students received their medical degrees. The keynote speaker was Mukesh K. Jain, MD ’91, Ellery Sedgwick Jr. Chair and Distinguished Scientist at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, who spoke on “The Privilege to Impact.� Jain is the recipient of the 2016 Distinguished Medical Alumnus Award from the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences (see related story on page 28).

Catholic Health Mercy Hospital of Buffalo Sisters of Charity Hospital Correspondence, including requests to be added to or removed from the mailing list, should be sent to: Editor, UB Medicine, 901 Kimball Tower, Buffalo, NY 14214; or email ubmedicine-editor@buffalo.edu 16-DVC-001

24 APLOMB AT THE CENTER OF THE STORM

3HGLDWULF QHXURORJLVW -HQQLIHU 0F9LJH 0' Âś VWRRG E\ D FRQWURYHUVLDO DQG FRUUHFW GLDJQRVLV XQGHU WKH JODUH RI PHGLD

Proud graduates Michael J. Hong Jr., left, and Joss Cohen.

From left, Nethra Madurai, Jamie Sklar and Joshua Cox celebrate the moment.

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

3

U B M E D V I TA L L I N E S

CONSTRUCTION MILESTONE FOR NEW MEDICAL SCHOOL On March 22, the final beam of steel was set atop the structure that will be the new home of the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences on the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus in downtown Buffalo. Speakers at the topping out ceremony included New York State Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo; UB President Satish K. Tripathi; Michael E. Cain, MD, vice president for health sciences and dean, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB; Jeremy M. Jacobs, chairman of Delaware North and chairman of the UB Council; and Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown. “We are building a physical and symbolic landmark on the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus, establishing the region’s first comprehensive academic medical center, transforming Buffalo into a destination for the best medical research, education and patient care,” Dean Cain told a large gathering. The 628,000-square-foot facility is scheduled to open in 2017.

Governor Andrew Cuomo and President Satish Tripathi signing the last beam.

Margaret and Jeremy Jacobs signing the beam.

Samantha Frank, Class of 2018, was one of many medical students who signed the beam.

Frank Schreck, MD ’79, and Mary Pat Schreck.

Candace Johnson, PhD, president and CEO of Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI), and Victor Filadora II, MD ’99, chief of perioperative medicine, RPCI, joining in the celebration.

Anne B. Curtis, MD, Charles and Mary Bauer Professor and Chair, Department of Medicine, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

The last beam is lifted into place atop the eight-story structure.

A happy day for Jeremy Jacobs.

Photos by Douglas Levere and Sandra Kicman

One of the last of 7,459 beams is prepared for hoisting.

Jonathan Daniels, MD ’98, immediate past president of the Medical Alumni Association.

Dean Michael E, Cain, MD, at the beam signing event on the South Campus.

4

SUMMER

2016

UB MEDICINE

Nancy Nielsen, MD ’76, PhD, senior associate dean for health policy; and Teresa Quattrin, MD, A. Conger Goodyear Professor and Chair, Department of Pediatrics, adding their names to the beam.

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

5

SPRING CLINICAL DAY AND REUNION WEEKEND 2016

WNY MEDICAL SCHOLARSHIP FUND RECIPIENTS

Alumni came from around the country this spring to celebrate with classmates, friends, faculty and students. More than 400 people joined in the festivities, which included an alumni cocktail party, dinners, tours of the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus, Spring Clinical Day and Medical Residents’ Scholarly Exchange, and presentation of the Distinguished Medical and Biomedical Alumnus awards and Volunteer of the Year Award. (Turn to pages 22 and 28 for related coverage.) The weekend was sponsored by the UB Medical Alumni Association and the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

First-year medical students Jessica LaPiano and Christine Robertson are the 2016 recipients of the Western New York Medical Scholarship Fund award. The award provides four-year tuition scholarships to select local students who attend the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. The Western New York Medical Scholarship Fund is an independent community organization founded last year by UB medical school alumnus John J. Bodkin II, MD ’76, who is co-chair with David M. Zebro, principal of Strategic Investments & Holdings. They teamed up with local organizations to create the fund to keep locally trained physicians in Western New York to help address the physician shortage. In order to accept the scholarship, students must pledge to stay in Western New York to practice for at least five years. Each awardee will receive a minimum of $30,000 annually for each of the four years of medical school. To be eligible for the scholarships, UB medical students must meet highly select criteria: They must have graduated from a high school within the eight Christine Robertson, left, and Jessica LaPiano. counties of Western New York, excel academically and have a demonstrated financial need. “I love the city of Buffalo and have always wanted to remain here,” says Robertson, who is from Williamsville, N.Y. “The city and its people are going through an incredible renaissance right now and it is so exciting to be part of that progress. It is such an honor to have been awarded this scholarship.” LaPiano, from Lancaster, N.Y., says: “I am very excited to know that I will be part of Buffalo’s rising medical community. Buffalo has been and always will be the city that I call home. I am grateful for the opportunity this scholarship provides me to give back to the community that has inspired and mentored me.” The 2016 scholarships are being funded by the John R. Oishei Foundation, Roswell Park Alliance Foundation and West-Herr Automotive Group. If you would like to contribute to this fund, contact Eric Alcott at 716-829-2773, or email medicine@devmail.buffalo.edu.

From left, Laszlo Tomaschek, MD ’76, Geraldine K. Kelley, MD ’76, and Shin Y. Liong, MD ’76

From left, Eric Southard, MD ’89, Kathylynn C. Pietak, MD ’91, John Gelineas, MD ’91, and Scott Williams, MD ’96 PhD

Photo by Sandra Kicman

U B M E D V I TA L L I N E S

Photos by Joe Cascio

WHITE HOUSE LISTS UB AS A LEADER IN OPIOID EPIDEMIC

From left, Anthony Alan IV, Gregory W. Branch, MD ’91, John John, MD ’91, and Mark Mancuso, MD ’91

6

SUMMER

2016

UB MEDICINE

From left, Terence M. Clark, MD ’71, Charles F. Yeagle III, MD ’71, David M. Rowland, MD ’71, and Molly Rowland, MD ’71

According to a fact sheet released by the White House, the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences is among medical schools nationwide at the forefront of fighting the opioid epidemic. The fact sheet was issued in conjunction with President Obama’s announcement this spring about steps being taken by medical schools and other organizations to combat the misuse and abuse of opioids. “Long before opioid addiction became a front-page issue, faculty in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences were leaders in developing formal curricula to teach medical students, residents and fellows how to prevent and treat addiction,” says Michael E. Cain, MD, vice president for health sciences and dean, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

Those efforts were led in large part by Richard D. Blondell, MD, professor of family medicine, who founded the Department of Family Medicine’s addiction medicine fellowship in 2011—one of the first of its kind to be accredited by the American Board of Addiction Medicine Foundation (ABAMF). There are now 40 such fellowships throughout the U.S. and Canada. In 2013, Blondell was appointed director of the National Center for Physician Training in Addiction Medicine. In March 2016, addiction medicine was approved as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties in response to an effort led by Blondell and his colleagues in the field.

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

7

U B M E D V I TA L L I N E S

MORE STUDENTS TRAINING IN BUFFALO

ERNSTOFF HEADS DIVISION OF HEMATOLOGY/ONCOLOGY

Responding to new energy in the community and the medical school

Dual appointment at UB and Roswell Park Cancer Institute

Medical students in the Class of 2016 celebrated the next steps in their medical careers during Match Day in March. There was much good news, including the fact that 45 out of the 143 members of the class will complete their residencies in Buffalo-area hospitals. That’s up from 33 last year and 30 the prior year. Students report that they like the new infusion of energy in the community and on the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus. (Turn to page 32 for a related story.) To view the entire match list, go to medicine.buffalo.edu and search 2016 Match Day.

Chinelo Ogbudinkpa, left, who will train in general surgery at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, talking with Upasana Kochhar, who will train in family medicine at UB.

William Du learns he will train in internal medicine at UB.

Marc S. Ernstoff, MD, has been appointed professor and chief of the Division of Hematology/Oncology in the Department of Medicine in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences and chair of the Department of Medicine, and senior vice president of clinical investigation at Roswell Park Cancer Institute. He also serves as chief of the Division of Hematology/Oncology at UBMD Internal Medicine, the clinical practice plan of the UB Department of Medicine. Ernstoff came to UB and Roswell from the Cleveland Clinic, where he served as director of the Melanoma Program at Taussig Cancer Institute since 2014. From 1991 to 2014, he served as associate professor of medicine and professor of medicine at Dartmouth College’s Geisel School of Medicine and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. During much of his tenure, he directed the Melanoma Program at the Norris Cotton Cancer Center and was section chief of hematology/oncology. Prior to that, Ernstoff was on faculty at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, where he directed the hematology/oncology fellowship training program. He also was an assistant professor of medicine at Yale University and director of its Clinical Research Office. Ernstoff’s clinical research is focused on the treatment of melanoma and genitourinary cancers. He is a member of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Melanoma Committee and the International Melanoma Working Group. A native of Brooklyn, N.Y., he completed his undergraduate degree

Marc S. Ernstoff, MD

at Emory University and earned his medical degree from New York University. He trained at the Bronx Municipal Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine and completed a medical oncology fellowship at the Yale University School of Medicine.

GIBBONS APPOINTED TO DUAL LEADERSHIP ROLES ROGER SEIBEL MEMORIAL FUND Supporting the next generation of trauma surgeons Trauma surgeon Roger Seibel, MD, FACS, longtime professor of surgery in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, is fondly remembered for his skills, leadership and passion for teaching and mentoring. He was instrumental in developing the trauma service at Erie County Medical Center (ECMC) in the 1970s in collaboration with John Border, MD, whose work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Seibel also was chief of surgery and director of trauma/burn services at ECMC until his death in 2007. At that time, an endowment fund was established in his memory at UB. Today, thanks to the generosity of many, the Roger W. Seibel, MD Memorial Fund is helping to support the

8

SUMMER

2016

UB MEDICINE

Trauma Critical Care Fellowship at UB and to offset conference costs for trauma surgery residents. “Roger always loved working with the next generation of trauma surgeons and encouraging them to excel,” says his widow, Kathleen. “He would be honored to know that a fund established in his memory is continuing to grow and assist those training for a future in trauma and critical care.” If you would like to make a gift in honor of Dr. Seibel and UB’s trauma surgery program, please send your gift to The Roger W. Seibel, MD Memorial Fund, UB Foundation, P.O. Box 900, Buffalo, NY 14226.

Kevin J. Gibbons, MD, has been named senior associate dean for clinical affairs in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences and executive director of UB Associates/UBMD, the university’s practice plan. In this dual role he will direct UB Associates and ensure an optimal relationship between UBMD and the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences and its partner institutions. Gibbons is an associate professor and vice Kevin J. Gibbons, MD chair in the Department of Neurosurgery and chief of neurosurgery for Kaleida Health. He also serves as director of surgery at Buffalo General Medical Center and the Gates Vascular Institute.

Gibbons received his bachelor of science degree from the University of Notre Dame and his medical degree from Albany Medical College. He completed his residency in neurological surgery and a fellowship in surgical critical care at UB. A nationally recognized speaker and educator, Gibbons is an expert in the surgical treatment of brain tumors, spinal and pituitary tumors, complex cervical disorders, critical care and adult hydrocephalus. He will continue his surgical practice at Buffalo General Medical Center and Gates Vascular Institute. Gibbons holds or has held several other major leadership positions at UB and in the Great Lakes Health System of Western New York. He has won numerous awards, including the 2009 Kaleida Spirit Award, the 2010 Erie County Medical Center Leadership Award and the 2007 Outstanding Citizen Award from the Buffalo News.

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

9

Medical Students Step up to Help Asylum-Seekers E S TA B L I S H H U M A N R I G H T S I N I T I AT I V E BY MARK SOMMER

“ T H E S E A R E S T U D E N T S W H O A R E A L E R T TO T H E P R O B L E M S O F T H E WO R L D . W H E N T H E Y C O M E TO M E D I CA L S C H O O L , T H E Y D O N ’ T WA N T TO LO S E T H AT. ” KIM GRISWOLD, MD ’94, MPH, FACULTY ADVISOR

Founders of the Human Rights Initiative, left to right: Kathleen Soltis, Class of 2017; Lauren Jepson, MD ’16; faculty advisor Kim Griswold, MD ’94, MPH; Sarah Riley, MD ’16; Rachel Engelberg, Class of 2018.

10

SUMMER

2016

UB MEDICINE

Asylum-seekers arrive in Buffalo from all over the world seeking a chance at a new life. Many have fled horrific conditions to get here, including rape and torture. Gaining permanent entry, however, requires presenting a convincing legal case, and that’s where University at Buffalo medical students come in. The Human Rights Initiative, run by medical students in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, provides medical and psychological forensic evaluations for asylum-seekers. The students, working with medical professionals, schedule and organize interviews, including the use of interpreters, and serve as scribes for long and often emotionally draining sessions. “The forensics evaluation documenting abuses really changes an asylum-seeker’s application by providing medical proof to go with the person’s story. It can strengthen their case,” says Kim Griswold, MD ’94, MPH, the group’s faculty advisor, and an associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine. Working with asylum-seekers is a powerful educational experience, students say. “Helping start the Human Rights Initiative was the most meaningful component of my medical school experience,” says Sarah Riley, MD ’16, who co-founded the project in 2014 with fellow medical students Lauren Jepson, MD ’16, and Kathleen Soltis, Class of 2017, under Griswold’s guidance. The work of the initiative occurs at a time when the world is facing its greatest migration crisis in over half a century. The United Nation’s refugee agency claims there are more displaced people worldwide—some 50 million—than at anytime since World War II. In New York State, the largest number of refugees are resettled in Buffalo. There were 4,085 refugees in New York between October 2013 and September 2014, according to the most recent records compiled by the New York State Bureau of Refugee and Immigrant Assistance. Some 96 percent of the refugees were resettled in upstate and Western New York, with 1,380, the largest number, coming to Buffalo and Erie County.

Between March 2015 and March 2016, 1,357 refugees from 70 countries came to VIVE, (Vive La Casa), a 118-bed asylum center on Buffalo’s east side. VIVE provides people with services they need to rebuild their lives, according to Anna Ireland, chief program officer for Jericho Road Community Health Center, which operates VIVE. Of these, fewer than 100 sought asylum in the U.S., the others seeking entry into Canada, where the government makes it easier to gain admittance.

COLLABORATION AT ITS BEST The idea for the Human Rights Initiative—formerly known as the WNY Human Rights Clinic—grew out of Riley, Jepson and Soltis’s roles on the executive board of the student chapter of Physicians for Human Rights. It’s there they learned about student-run asylum clinics at several medical schools around the country, including Brown University, Cornell University, Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania. At first, Riley, Jepson and Soltis were concerned that as full-time medical students they wouldn‘t have the time to do something similar at UB. Griswold convinced them to try. Their opportunity came after a grant from the New York State Health Foundation in June 2014 established the Western New York Center for Survivors of Torture, a program of Jewish Family Service of Buffalo & Erie County, in collaboration with the UB Department of Family Medicine and Journey’s End Refugee Services. The Center for Survivors supports individuals and their families with legal, medical and other services. Griswold was named medical director, helping set the stage for a collaboration between the two newly-established groups. Soltis, then serving as co-president of Physicians for Human Rights, interned that summer at the newly created center and helped recruit students into the Human Rights Initiative. In October 2014, the UB students hosted an informational dinner to educate physicians about the mission of the Human Rights Initiative.

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

11

DV ZHOO DV ZLWK IRONV ZLWK VHULRXV PHQWDO LOOQHVV 2IWHQ SHRSOH GRQ¶W OLVWHQ WR WKHP ´ *ULVZROG VD\V 7KH SURJUDP KDV EHHQ D YDOXDEOH RXWOHW IRU VWXGHQWV ZKR DUH FRQFHUQHG DERXW VX̆HULQJ LQ RWKHU SDUWV RI WKH ZRUOG DQG ZDQW WR KHOS VKH DGGV ³7KHVH DUH VWXGHQWV ZKR DUH DOHUW WR WKH SUREOHPV RI WKH ZRUOG :KHQ WKH\ FRPH WR PHGLFDO VFKRRO WKH\ GRQ¶W ZDQW WR ORVH WKDW ´

POWERFUL MOMENTS

“ LE ARN ING TO LIS T EN IS ONE OF T HE M O ST I M PO RTA NT THI NG S A PH Y SI CI A N CA N D O WITH ASY LUM-S EEKERS O R R E F U G E E S T E L L I N G T H E I R S TO R Y , A S WEL L A S W I T H FO L KS WITH S ERIOUS MENTAL ILLNESS. O F TEN PEO PL E DO N’ T L I STEN TO THE M .” KIM GRISWOLD, MD ’94, MPH Douglas Sawch, Class of 2018, and faculty advisor Kim Griswold, MD ’94, MPH, meeting with an asylum-seeker.

6HYHUDO PRUH HYHQWV ZHUH KHOG LQ WR SXEOLFL]H WKH LQLWLDWYH DQG SURYLGH WUDLQLQJ 7KDW $SULO 8% PHGLFDO VWXGHQWV DWWHQGHG D 3K\VLFLDQV IRU +XPDQ 5LJKWV WUDLQLQJ VHVVLRQ DW <DOH 8QLYHUVLW\ ZKHUH WKH\ OHDUQHG KRZ WR OLVWHQ WR D WRUWXUH VXUYLYRU¶V VWRU\ DQG WR EH D VFULEH ,Q -XQH D SRVWHU VKRZLQJ WKH GHYHORSPHQW RI WKH +XPDQ 5LJKWV ,QLWLDWLYH ZDV SUHVHQWHG DW WKH 1RUWK $PHULFDQ 5HIXJHH +HDOWK &RQIHUHQFH LQ 7RURQWR $QG LQ 1RYHPEHU D WUDLQLQJ VHVVLRQ KHOG LQ FROODERUDWLRQ ZLWK +HDOWK5LJKW ,QWHUQDWLRQDO GUHZ DWWHQGHHV WR 8%¶V 6RXWK &DPSXV 3DUWLFLSDQWV LQFOXGHG PHGLFDO VWXGHQWV SK\VLFLDQV ODZ\HUV VRFLDO ZRUNHUV DQG RWKHU KHDOWK SURIHVVLRQDOV 6WXGHQWV DOVR SUHVHQWHG JUDQG URXQGV LQ REVWHWULFV J\QHFRORJ\ LQWHUQDO PHGLFLQH DQG SV\FKLDWU\ 7KH JURXS ZDV UHFRJQL]HG DV D 3ROLW\ FOXE RQ FDPSXV WKDW VDPH \HDU DQG IXQGV ZHUH UHFHLYHG IURP VHYHUDO FRQWULEXWRUV WR KHOS GHIUD\ FRVWV 7KHUH ZHUH DOVR FROODERUDWLRQV ZLWK FRPPXQLW\ RUJDQL]DWLRQV WKDW VKDUHG D FRPPRQ PLVVLRQ $V RI 0DUFK PHGLFDO VWXGHQWV KDG EHHQ WUDLQHG DV VFULEHV DQG PHGLFDO

12

SUMMER

2016

DQG SV\FKRORJLFDO IRUHQVLF H[DPLQDWLRQV KDG EHHQ FRQGXFWHG ZLWK LQGLYLGXDOV IURP FRXQWULHV 7ZR FOLHQWV UHFHLYHG DV\OXP ZKLOH WKH RXWFRPHV RI WKH RWKHUV ZHUH VWLOO SHQGLQJ

LEARNING TO LISTEN *ULVZROG FRQGXFWV PHGLFDO H[DPV IRU WKH +XPDQ 5LJKWV ,QLWLDWLYH LQ DGGLWLRQ WR DGYLVLQJ VWXGHQWV 8% SV\FKLDWULVWV H[DPLQH SHRSOH VX̆HULQJ IURP SV\FKRORJLFDO WUDXPD *ULVZROG¶V ZRUN ZLWK UHIXJHHV EHJDQ DV D QXUVH DW 9,9( IURP WR 6KH OHIW WR DWWHQG PHGLFDO VFKRRO EXW FRQWLQXHG WR ZRUN ZLWK UHIXJHHV DQG UHPDLQV LQYROYHG ZLWK 9,9( E\ YROXQWHHULQJ RQH GD\ D PRQWK ³7KHLU VWRULHV DUH VR KDUG WR KHDU ´ *ULVZROG VD\V ³0DQ\ RI WKH ZRPHQ ZH VHH LQ FRXQWULHV DW ZDU KDYH H[SHULHQFHG VH[XDO YLROHQFH 7KDW LV RQH RI WKH PRVW SUHYDOHQW SK\VLFDO DQG SV\FKRORJLFDO VWRULHV WKDW ZH KHDU ´ 7KH PDMRULW\ RI UHIXJHHV FRPLQJ LQWR %X̆DOR DUH IURP %XUPD %KXWDQ 6RPDOLD DQG ,UDT 7KH FRXQWULHV ZLWK WKH PRVW DV\OXP VHHNHUV LQ UHFHQW \HDUV DUH WKH

UB MEDICINE

'HPRFUDWLF 5HSXEOLF RI &RQJR (O 6DOYDGRU ,UDQ DQG 1LJHULD ³5DSH LQ WKH 'HPRFUDWLF 5HSXEOLF RI &RQJR LV D ZHDSRQ RI ZDU ´ *ULVZROG VD\V ³:RPHQ KDYH RIWHQ EHHQ UDSHG QRW RQFH EXW PDQ\ WLPHV %RQGDJH LV DQRWKHU ZKHUH ZRPHQ DUH NHSW FDSWLYH DV VH[XDO VODYHV ´ *ULVZROG VDLG SHRSOH ZKR VSHDN RXW LQ UHSUHVVLYH FRXQWULHV DUH IUHTXHQWO\ LPSULVRQHG DQG WRUWXUHG <HW OHDYLQJ D UHSUHVVLYH FRXQWU\ GRHVQ¶W VXGGHQO\ ZLSH WKH SDVW FOHDQ VKH REVHUYHV ³6HHNLQJ DV\OXP LV RQH ZD\ WR JLYH WKHP VRPH PHDVXUH RI SHDFH EXW LW FDQ QHYHU HUDGLFDWH ZKDW WKH\ ZHQW WKURXJK RU WKH IDFW WKDW WKH\ KDG WR OHDYH EHKLQG WKHLU IDPLO\ SHUKDSV IRUHYHU ´ *ULVZROG H[SODLQV ³, WKLQN PDQ\ RI XV FDQ¶W LPDJLQH WKDW ´ *ULVZROG VD\V VKH ZRUULHV DERXW WKH WROO WKH VWRULHV FDQ WDNH RQ VWXGHQWV DQG VKH KROGV PHHWLQJV WR KHOS WKHP SURFHVV ZKDW WKH\¶YH KHDUG $ SRVLWLYH IRU VWXGHQWV VKH IHHOV LV WKDW WKH IRUHQVLF H[DPLQDWLRQV KHOS WKHP OHDUQ PRUH DERXW FRPPXQLFDWLQJ ³/HDUQLQJ WR OLVWHQ LV RQH RI WKH PRVW LPSRUWDQW WKLQJV D SK\VLFLDQ FDQ GR ZLWK DV\OXP VHHNHUV RU UHIXJHHV WHOOLQJ WKHLU VWRU\

.DWKOHHQ 6ROWLV QRZ D IRXUWK \HDU VWXGHQW YROXQWHHUHG LQ D ORZ LQFRPH FRPPXQLW\ DV DQ XQGHUJUDGXDWH DW %RVWRQ &ROOHJH WXWRULQJ SULVRQ LQPDWHV WHDFKLQJ VFLHQFH OHVVRQV DW DQ LQQHU FLW\ HOHPHQWDU\ VFKRRO DQG ZRUNLQJ LQ D KRPHOHVV VKHOWHU ³, ZDV ORRNLQJ IRU WKRVH VRUWV RI RSSRUWXQLWLHV ZKHQ , VWDUWHG PHGLFDO VFKRRO ´ VKH VD\V ³1RW LQLWLDOO\ EHFDXVH PHGLFDO VFKRRO LQ WKH EHJLQQLQJ LV SUHWW\ RYHUZKHOPLQJ %XW , IHOW DV WKRXJK VRPHWKLQJ ZDV ODFNLQJ LQ P\ OLIH VRPHWKLQJ , ZDVQ¶W JHWWLQJ IURP WKH PHGLFDO FXUULFXOXP SHU VH ´ :KHQ 6ROWLV ¿UVW OHDUQHG DERXW WKH VXPPHU LQWHUQVKLS RSSRUWXQLW\ ZLWK WKH :HVWHUQ 1HZ <RUN &HQWHU IRU 6XUYLYRUV RI 7RUWXUH VKH VRXJKW RXW D SXEOLF KHDOWK FRXUVH R̆HUHG DW 8% RQ UHIXJHH SRSXODWLRQV ,W ZDV WKHUH VKH OHDUQHG DERXW %X̆DOR¶V UHIXJHH SRSXODWLRQV DQG KRZ WKH\ GL̆HUHG IURP WKRVH VHHNLQJ DV\OXP 'RFXPHQWLQJ DEXVH DV D VFULEH DORQJVLGH PHGLFDO GRFWRUV VHHPHG WR EH VRPHWKLQJ WKDW FRXOG PDNH D GL̆HUHQFH $QG VKH VDLG LW KDV PDGH D GL̆HUHQFH ³,W¶V D UHDOO\ UHDOO\ SRZHUIXO PRPHQW ZKHQ \RX KDYH WKH RSSRUWXQLW\ WR EHDU ZLWQHVV WR VRPHRQH¶V VWRU\ ´ 6ROWLV VD\V ³,W¶V SUREDEO\ RQH RI WKH ¿UVW WLPHV WKDW , IHOW WKDW , ZDV UHDOO\ PDNLQJ D GL̆HUHQFH HDUO\ RQ LQ P\ FDUHHU ´ 6ROWLV VD\V WKDW WKH VWRULHV VKH¶V KHDUG DUH KHDUWEUHDNLQJ ³:H KHDU SUHWW\ WU\LQJ WDOHV UDQJLQJ IURP VH[XDO DVVDXOW UDSH LPSULVRQPHQW WRUWXUH ZLWK WRROV DQG HOHFWURFXWLRQ 7KHVH DUH WKLQJV \RX WKLQN \RX ZRXOG RQO\ VHH LQ PRYLHV 7KLQJV \RX GRQ¶W WKLQN DUH SRVVLEOH WR HYHU KHDU DERXW ZH KHDU DERXW ´

FORENSIC EVALUATION TRAINING 7KH :HVWHUQ 1HZ <RUN &HQWHU IRU 6XUYLYRUV RI 7RUWXUH LGHQWL¿HV FOLHQWV DQG OLQNV WKHP ZLWK WKH +XPDQ 5LJKWV ,QLWLDWLYH )RUHQVLF HYDOXDWLRQV ZKLFK WDNH SODFH LQ WKH DWWHQGLQJ SK\VLFLDQ¶V ṘFH DUH W\SLFDOO\ WZR WR IRXU KRXUV ZLWK D GRFWRU PHGLFDO VWXGHQW DQG LQWHUSUHWHU SUHVHQW 7KH WUDLQLQJ WKDW WKH VWXGHQWV UHFHLYH LQFOXGHV FXOWXUDO FRPSHWHQF\ DQG KRZ WR ZRUN ZLWK LQWHUSUHWHUV 7KH VWXGHQW VFULEHV IROORZ WKH ,VWDQEXO 3URWRFRO ZKLFK DUH LQWHUQDWLRQDO VWDQGDUGV IRU WKH VWUXFWXUH RI D IRUHQVLF H[DP DQG UHSRUW 7KLV VWUXFWXUH PDNHV WKHP SDUWLFXODUO\ YDOXDEOH WR LPPLJUDWLRQ FRXUWV 6WXGHQWV ZULWH GRZQ YHUEDWLP ZKDW WKH DV\OXP VHHNHU VD\V DQG VWULYH WR EH DQ REMHFWLYH HYDOXDWRU LQ WKHLU DVVHVVPHQW $IWHUZDUGV WKH VWXGHQW SUHSDUHV WKH ḊGDYLW ZLWK WKH FOLQLFLDQ ZKR DGGV WKH FRQFOXVLRQ DQG LPSUHVVLRQV DQG WKHQ VHQGV LW WR WKH FOLHQW¶V DWWRUQH\ 3DP .H¿ ZKR GLUHFWV WKH :HVWHUQ 1HZ <RUN &HQWHU IRU 6XUYLYRUV RI 7RUWXUH VDLG WKH 8% PHGLFDO VWXGHQWV KDYH SOD\HG D YLWDO UROH LQ WKH SURJUDP ZKLFK KDV KHOSHG LQGLYLGXDOV LQ LWV ¿UVW WZR \HDUV ³7KH VWXGHQWV EULQJ VR PXFK HQHUJ\ DQG DWWHQWLRQ WR GHWDLO DQG

“ H E L P I N G S TA R T T H E H U M A N R I G H T S I N I T I AT I V E WA S T H E M O S T M E A N I N G F U L C O M P O N E N T O F M Y M E D I CA L S C H O O L E X P E R I E N C E .” SARAH RILEY, MD ’16

WKH\ SXW LQ KRXUV ODWH DW QLJKW DQG RQ ZHHNHQGV ´ .H¿ VD\V ³,W¶V DPD]LQJ KRZ WKH\ FDQ GR WKLV ZRUN LQ WKH PLGVW RI GRLQJ DOO RI WKHLU PHGLFDO VFKRRO UHVSRQVLELOLWLHV :H UHDOO\ VWDQG LQ DZH RI WKHP ´

CONTINUITY OF CARING 5DFKHO (QJHOEHUJ &ODVV RI GLUHFWV FOLQLFDO RSHUDWLRQV IRU WKH +XPDQ 5LJKWV ,QLWLDWLYH LQFOXGLQJ WKH VFKHGXOLQJ RI IRUHQVLF H[DPV 6KH KDV EHHQ D VFULEH DW VL[ IRUHQVLF H[DPV VLQFH JHWWLQJ LQYROYHG LQ $SULO ³7KH SHRSOH ZH VHH KDYH EHHQ WKURXJK WKHVH KRUULEOH H[SHULHQFHV²ZRUVH WKDQ \RX FRXOG LPDJLQH²DQG \HW WKH\ DUH VR UHVLOLHQW ´ (QJHOEHUJ VD\V ³,W¶V WKH ¿UVW WLPH , HYHU IHOW OLNH , GLG VRPHWKLQJ WKDW WUXO\ PDWWHUHG , IHHO ZLWK PHGLFLQH ULJKW QRZ HYHU\WKLQJ LV ORQJ WHUP UHZDUG EXW ZLWK WKLV \RX FDQ VHH WKH LPSDFW \RX DUH KDYLQJ ´ )LUVW DQG VHFRQG \HDU PHGLFDO VWXGHQWV DUH UHFUXLWHG WR HQVXUH WKH +XPDQ 5LJKWV ,QLWLDWLYH FDUULHV RQ 7KH\ DQG IRXUWK \HDU VWXGHQWV DUH WKH PRVW LQYROYHG VLQFH WKLUG \HDU VWXGHQWV DUH RQ URWDWLRQ DQG WKHLU WLPH LV UHVWULFWHG $ WKUHH \HDU JUDQW UHFHLYHG E\ -HZLVK )DPLO\ 6HUYLFH HDUOLHU WKLV \HDU IRU WKH :HVWHUQ 1HZ <RUN &HQWHU IRU 6XUYLYRUV RI 7RUWXUH HQVXUHV WKH +XPDQ 5LJKWV ,QLWLDWLYH ZLOO FRQWLQXH WR EH QHHGHG ³%\ WUDLQLQJ VWXGHQWV WR EH PHGLFDO VFULEHV ZH DUH LQYHVWLQJ LQ WKH QH[W JHQHUDWLRQ WR WDNH RYHU WKH FOLQLF ´ H[SODLQV 6ROWLV ZKR OHDQV WRZDUG D FDUHHU LQ IDPLO\ PHGLFLQH ,Q FRQWUDVW 5LOH\ LV SODQQLQJ WR EH D SV\FKLDWULVW DQG -HSVRQ LV SUHSDULQJ IRU D FDUHHU LQ SHGLDWULFV ³2XU OHDGHUVKLS UHSUHVHQWV D ORW RI GL̆HUHQW LQWHUHVWV EXW WKLV LV D WRSLF WKDW WUDQVFHQGV DOO VSHFLDOWLHV ´ 6ROWLV QRWHV ³<RX QHYHU NQRZ ZKHQ D UHIXJHH LV JRLQJ WR VKRZ XS DW RXU GRRUVWHS :H JRW LQYROYHG ZLWK WKLV EHFDXVH ZH UHDOL]HG WKHUH ZDV WKLV XQPHW QHHG $IWHU WKH WUDXPD WKH\ KDYH IDFHG LW VHHPV OLNH SURYLGLQJ D IRUHQVLF H[DPLQDWLRQ LV WKH OHDVW ZH FDQ GR ´ -HSVRQ VD\V VKH SODQV WR FRQWLQXH ZRUNLQJ ZLWK UHIXJHHV DQG DV\OXP VHHNHUV DQG WR EURDGHQ KHU XQGHUVWDQGLQJ RI KHDOWK FDUH LQ LQWHUQDWLRQDO VHWWLQJV HVSHFLDOO\ LQ DUHDV RI FRQÀLFW ³7KRXJK , JUHZ XS LQ %X̆DOR , ZDV QDLYH DERXW WKH ODUJH UHIXJHH DQG DV\OXP VHHNLQJ SRSXODWLRQV KHUH XQWLO PHGLFDO VFKRRO ´ -HSVRQ VD\V ³, DP VR JUDWHIXO WR KDYH KDG WKH RSSRUWXQLW\ WR OHDUQ IURP WKHVH FOLHQWV WR KDYH ZRQGHUIXO PHQWRUV OLNH 'U *ULVZROG DQG WR ZRUN ZLWK VXFK SDVVLRQDWH PHGLFDO VWXGHQWV ´

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

13

Together We Can Make a Difference T E R E S A Q U AT T R I N , M D , A L E A D E R I N P E D I AT R I C D I A B E T E S R E S E A R C H A N D CA R E

Back in the mid-1980s, Teresa Quattrin, MD, was bursting with youthful exuberance and a million ideas. Having completed fellowships in pediatric endocrinology and genetics at the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, she was sure her field was on the cusp of momentous change. “I wanted to

14

SUMMER

2016

UB MEDICINE

COLLEEN KARUZA

make a difference, and I was cocky enough to believe that a cure for Type 1 diabetes was within our grasp,” she says. One of her mentors at the time was the late Allan L. Drash, MD, PhD, professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, considered by many to be the father of modern-day pediatric diabetes. Drash saw things from a slightly different angle. “He commended me on my enthusiasm, but advised me to rein it in and prepare for the long haul,” Quattrin recalls with a smile. “He knew all too well the Goliath we were up against, and the enormous amount of talent, collaboration and resources it would require over time to take it down.” Today, Quattrin is a national leader in Type 1 diabetes research, in large part because the essential components are in place in Buffalo, where she holds three key leadership positions: A. Conger Goodyear Professor and Chair of Pediatrics at UB; pediatrician-in-chief and chief of pediatric endocrinology and diabetes at Kaleida Health’s Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, a UB teaching affiliate; and president of UBMD pediatrics. Working from this world-class foundation, Quattrin remains headstrong in her resolve to develop—through leadership, translational research and collaboration—the successful, evidence-based care strategies that patients with Type 1 diabetes need to live longer, healthier lives. “I am still an optimist and envision a future where this disease can be effectively prevented and cured,” she says.

A MERGING OF INTERESTS

Teresa Quattrin, MD, A. Conger Goodyear Professor and Chair of Pediatrics, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

BY

Quattrin was born in Naples, Italy, and grew up there and in northern regions of the country. She attended the University of Naples, where she narrowed down her career ambitions to medicine or business law. “Both professions appealed to me,” she explains. “I have always been attracted to the business side of things, so I merged my interests and decided to pursue a career in medicine and health care administration.” After graduating from the University of Naples School of Medicine with high honors and completing her residency in Naples, Quattrin was determined to find a specialized training program in alignment with her research interests. She settled on UB, where, between 1985 and 1990, she completed an additional year of residency in pediatrics, one year of training in genetics and a fellowship in pediatric endocrinology and diabetes.

“Right away, I felt at home with the collegial environment,” she says. With ongoing opportunities for collaboration with faculty at three international research powerhouses in close proximity—UB, Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo and Roswell Park Cancer Institute—she also felt certain that Buffalo could sustain its momentum as a launching pad for discovery and innovation. “In the 1980s, pediatric endocrinology was still a relatively young field that was poised for growth,” she observes. “This was happening in Buffalo, where scientists and clinicians were already beginning to break down professional silos through strong collaborations.” Quattrin decided to put down roots in Western New York, and in 1990 she became an attending physician in the Division of Endocrinology and Diabetes at Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, where she was named director of the Diabetes Center. In the years that followed, she assumed greater leadership responsibilities.

EFFORT TO REDUCE THE TOLL

From the beginning, Quattrin doggedly pursued the lines of research that she felt could reduce the toll of Type 1 diabetes, and her investigations could not have been more timely. Over the last two decades, the incidence of Type 2 diabetes—largely attributed to obesity—has been on the rise and well-documented. What continues to confound scientists and clinicians is the reason for the steady rise in incidence rates (roughly 3 to 5 percent annually) for Type 1 diabetes. “It’s humbling that with all the advances in genetics and endocrinology we have made over the past 30 years we still have not found a way to prevent Type 1 diabetes,” Quattrin says. “But our understanding of the disease has significantly improved over time through some very sophisticated research studies.” A number of these studies have been conducted by TrialNet, an international network of researchers from 18 clinical centers and 200 screening sites that was formed in direct response to recommendations made in the U.S. Surgeon General’s Report, Healthy People 2000. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), TrialNet studies explore ways to prevent, delay and reverse the progression of Type 1 diabetes.

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

15

Quattrin is the principal investigator of the UB-Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo TrialNet grant that supports the Pathway to Prevention Type 1 diabetes study. Since 2005, more than 1,731 Western New York children who are at risk of developing this disease have been enrolled. Currently, there are 170,579 participants worldwide. Previous research in Buffalo and elsewhere has revealed that it can take anywhere from 5 to 10 years for symptoms of Type 1 diabetes, such as thirst, extreme hunger, frequent urination, weight loss and blurred vision, to appear. A number of the TrialNet studies focus on that window that precedes the onset of diabetes. “These studies also built on earlier investigations that determined factors—such as an individual’s genetic makeup as well as autoimmune conditions—that predispose someone to develop Type 1 diabetes,” Quattrin says. “They have provided a kind of road map that now allows us to predict with extreme precision if and when someone will develop the disease.”

CHILDHOOD OBESITY

As a pediatric endocrinologist, Quattrin has been studying the trends in childhood obesity and its causes for many years. “There’s no simple answer regarding causation, but the problem has been escalating for some time,” she says. “It’s easy to play the blame game and point fingers at bad habits and poor lifestyle choices as the culprits in childhood obesity,” she notes, “but we need to step back and realize that many factors, including social disparities, play a role, especially in minorities. When we advocate for healthy diets, we have to remember that fresh foods are more expensive and less accessible than cheap, fast foods. So we need to educate, not blame. “It’s also difficult to ask those most susceptible to pay attention to better food choices and to get more exercise when larger issues loom, such as poverty, unemployment and neighborhood crime,” she adds. Quattrin contends that only comprehensive, wellthought-out strategies will effectively change the landscape of obesity management in both children and adults. “We need to provide incentives and invest in culturally sensitive programs that have shown to be successful on a smaller scale and expand them. Primary care settings need to align with public health initiatives, programs and recommendations. And finally, we need to give our pediatricians the training and tools that enable them to identify risk factors and engage the entire family in thwarting this problem.”

FAMILY-CENTERED INTERVENTIONS

Decades of experience have led Quattrin to believe that family-centered strategies for any chronic disorder, including obesity, are the best, most direct way to achieve positive outcomes. She also believes that the best way to provide this care is through team-based health care. “We have entered a new era where students, trainees and specialists have to learn how to better interact with primary

16

SUMMER

2016

UB MEDICINE

care providers and implement coordinated care,” she says. In 2010, Quattrin and her collaborators launched a family-based weight control intervention in preschool children, ages 2 to 5, in urban and suburban pediatric practices in Western New York. (This age group was targeted because data indicate 80 percent will go on to become obese adults if both parents are obese.) Called Buffalo Healthy Tots, the initiative was funded by a $2.6 million grant from the NIH. The goal was to compare traditional interventions, in which only the child receives treatment, to family-based behavioral therapies implemented in pediatric primary care practices. Quattrin teamed up with UB colleagues Leonard Epstein, PhD, professor of pediatrics, and James N. Roemmich, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics and exercise and nutrition science, who is now with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Results gleaned from the Buffalo Healthy Tots intervention—and published in the journal Pediatrics in 2014—provided compelling support for Quattrin’s push for family-based care in the primary care setting. “Our results underscored that traditional approaches to obesity prevention and treatment that focus only on the young child, rather than the entire family, are obsolete,” she reports. Quattrin and her colleagues discovered that when overweight/obese preschool-age children and their overweight/obese parents received treatment in a primary care setting with behavioral modification, both child and adult experienced greater decreases in weight and body mass index (BMI) than children who received traditional child-only treatment. Parents who received care lost an average of 14 pounds, resulting in a BMI decrease of more than two units, while the weight of nonparticipating parents was essentially unchanged. “This study is important because while we know that it is critical to begin treating overweight or obese children early, we’ve had limited data on what works best,” she says. “Now we have some answers and know we can collaborate effectively with community pediatricians. “I am very proud of this research,” she adds, “because it is the result of team science—the product of scientists and primary care providers working together, merging different areas of expertise.”

COLLABORATION IS THE KEY

Quattrin emphasizes that “besides being very fortunate to collaborate with many scientists at UB,” she considers herself “uniquely blessed” to work with talented, forwardthinking community pediatricians who are willing to bring novel programs to their practices to help further enhance the care they provide to youth and their families. “It’s not an overstatement to say how much I value and rely on these partnerships,” she says. These types of bridge-building relationships, she continues, are critical to the success of the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus and its role as a dynamic 21st-century academic health center. “None of us can presume to know all the answers, but collaboration makes finding them easier.” The new John R. Oishei Children’s Hospital, scheduled to

The UB-Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo pediatric endocrinology/diabetes team. Standing, left to right: John Buchlis, MD, Indrajit Majumdar, MD, Kathleen Bethin, MD-PhD ’95; and seated, left to right: Shannon Fourtner, MD ’99, Christine Albini, MD ’80, PhD ’77, Teresa Quattrin, MD, Lucy Mastrandrea, MD-PhD ’99.

open on the campus in late 2017, also will accelerate and enhance pediatric research and drive innovation through collaboration. It will link via sky bridges with the UB medical school, Buffalo General Medical Center, Gates Vascular Institute, and Roswell Park Cancer Institute, as well as other partners. Bricks and mortar aside, the real excitement “is about having additional collaborators within close proximity to facilitate communication and exchange of ideas,” Quattrin contends. The proximity of the Oishei Children’s Hospital to Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI), for example, will benefit young cancer patients and their families by streamlining continuity of care. Plans are underway to dedicate an entire floor in the new hospital to inpatient cancer care, while a new pediatric outpatient facility will be located at RPCI, only minutes away. “We’re very proud of the partnership of UB, Kaleida Health and Roswell

“I am very proud of this research because it is the result of team science—the product of scientists and primary care providers working together, merging different areas of expertise.” —Teresa Quattrin, MD

that has made it possible to recruit nationally respected pediatric oncologist Kara Kelly to lead our joint pediatric hematology and oncology program,” Quattrin notes. Kelly, who graduated from UB’s medical school in 1989, came to Buffalo from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, where she served as professor of pediatrics and associate director of the Division of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation. Quattrin says that she hopes the next decade will see accelerated progress in all areas of pediatrics, but

especially in Type 1 diabetes. “I do see a tomorrow where we may be able to prevent this disease and, if not cure it, then at least halt the progression of the destruction of the pancreas.” She knows from experience that success will depend on mobilizing the right teams of physicians and scientists—both those in academic centers and the community—and patients and families. “At heart, I’m the same person I was back in the 1980s,” she says. “I still believe that together we can make a difference.”

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

17

Not an Easy Option to Weigh A PIONEER IN BARIATRIC SURGERY FOR ADOLESCENTS JOINS THE JACOBS’ FACULTY

BY COLLEEN KARUZA

By the time a severely obese teenager and his or her family come to see Carroll McWilliams Harmon, MD, PhD, it usually means that they’re approaching the threshold of what he calls “the last door in the hallway.” “Whether we enter together depends on careful thought and planning, a committed support team, and the conviction that we have left no other doors unopened, no other rooms unexplored,” says Harmon, professor and chief of pediatric surgery in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, and John E. Fisher Chair in Pediatric Surgery at Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, a major UB teaching affiliate. Harmon’s “last door” metaphor refers to bariatric surgery, a treatment option available to a select group of adolescents whose obesity-related challenges, ranging from obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension to Type 2 diabetes and kidney disease, have created a potentially life-threatening medical situation. “For them, standard weight loss strategies have proven ineffective,” says Harmon, who also directs UB’s pediatric surgery fellowship program. Recruited to Buffalo in 2014 from the University of Alabama, Birmingham (UAB), Harmon is a pioneer in the use of bariatric surgery for severely obese teenagers. As coprincipal investigator on a $10 million National Institutes of Health (NIH) multicenter grant that extends to 2018, he is leading the first study in the U.S. that assesses the short- and longer-term effects of weight-reduction surgery in adolescents.

GOING WHERE THE NEED IS

A native of Birmingham, Harmon was formerly the surgical

18

SUMMER

2016

UB MEDICINE

director for the Children’s Center for Weight Management and the Georgeson Center for Advanced Intestinal Rehabilitation at Children’s of Alabama, UAB. While Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo appealed to Harmon for its “rich, storied past of leadership and innovation,” what brought him north of the MasonDixon Line was the “exceptional opportunity to turn around some things” for Western New York children struggling with obesity and other conditions. Childhood obesity rates in New York State fall well below those in Southern states such as Mississippi and Alabama; however, they vary regionally, and Western New York has the highest incidence in the Empire State.

NO EASY ANSWERS

A 2015 report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that nationally, a staggering 17.5 percent of children and adolescents, ages 3 to 19, are obese. In the late 1970s, it was 5.6 percent. In addition, studies reveal that for adolescents ages 10 to 19, severe obesity— defined as 100 or more pounds over normal body weight and a body mass index (BMI) greater than 40—has tripled in the last 25 years. Harmon, who formerly chaired the Childhood Obesity Committee of the American Pediatric Surgical Association, admits that he has no easy explanation for the cause or rise in childhood obesity. “It’s a complex interaction of lifestyle, environment, culture and genetics, and how it became a

Carroll McWilliams Harmon, MD, PhD, professor and chief of pediatric surgery in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences; and John E. Fisher Chair in Pediatric Surgery at Kaleida Health’s Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, a major UB teaching affiliate.

national epidemic is still an area of and Translational Research Center intense debate. While basic science a biorepository of tissue and blood has identified a number of genetic specimens that will yield important mutations causing obesity, that is clues. only one piece of a stealthily intricate puzzle.” UNFINISHED BUSINESS And when it comes to eating It was nearly 16 years ago that patterns, humans march to an Harmon first explored surgery as ancestral drumbeat, hearkening back an option for extreme obesity in to the Stone Age. “Homo sapiens have adolescents. At the time, he was an —Carroll McWilliams Harmon, MD, PhD been hard-wired to a feast-or-famine, established international leader in eat-or-be-eaten biology that was once pediatric minimally invasive surgery key to survival,” says Harmon, noting and an early proponent of “rightthat human genome evolution has not kept pace with salient sized” surgical technology for younger patients. environmental changes. A serendipitous gathering at an airport in 2000 would “Cavemen bulked up when food was abundant to get give flight to new possibilities. through times when it was scarce,” he says. Even today, Attending a major pediatric conference in Chicago that with the availability of cheap, fast, fatty foods, the default year, Harmon discovered that the subject of childhood response is often “to overload and eat when we’re not obesity dominated the proceedings, supporting the new hungry. But there’s one difference: there’s no famine.” reality of a full-blown obesity epidemic in the United States. Harmon holds a PhD in molecular physiology and Pediatricians, overwhelmed by the shocking number of biophysics. He searches for answers to the obesity problem extremely obese children presenting with adult obesityby conducting basic research on appetite control and on how related diseases, began reaching out to specialists. lipids play a role in obesity and other diseases such as fatty “After the meeting, a group of us, including some NIH liver. He also is working to establish within UB’s Clinical leaders, were waiting for planes at O’Hare and we just

“It’s a complex interaction of lifestyle, environment, culture and genetics, and how it became a national epidemic is still an area of intense debate.”

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

19

started talking,” recalls Harmon. “There was so much unfinished business on the childhood obesity issue, and an urgency to do something about it. We each flew home, determined to work on solutions.” Noting its successes in severely obese adults, Harmon decided to explore bariatric surgery in younger patients when he returned to Alabama. After extensive training, he performed his first surgery on a severely obese teenager in 2004.

NO QUICK FIXES

In the October 2015 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, Harmon and his colleagues published the first multisite national study of severely obese teenagers after weight-loss surgery. Of the 228 participants, 161 had gastric bypass and 67 had the less invasive sleeve gastrectomy. Average patient age and BMI were 17 and 53, respectively. The results were nothing less than stunning. At three years postsurgery, 85 percent were still compliant with their weight-loss regimen. Patients saw an average weight loss of 27 percent—up to 100 pounds—and 95 percent saw remission of Type 2 diabetes. Also, 86 percent had abnormal kidney function return to normal and 74 percent had remission of hypertension. Significant improvements were noted in cardiovascular and metabolic health, and weight-associated quality-of-life markers. Both laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery and the less invasive sleeve gastrectomy are available at Women and Children’s Hospital

“Our guiding principle is that bariatric surgery for teens should not occur in isolation, but in an environment that meets their unique physical, medical, behavioral, psychosocial and emotional needs.” —Carroll McWilliams Harmon, MD, PhD

20

SUMMER

2016

of Buffalo. In sleeve gastrectomy, a large part of the stomach is removed, leaving a portion that is about 25 percent of its original size. With gastric bypass surgery, a small pouch is created by stapling closed the top portion of the stomach, separating it from the lower portion. The downstream small intestine is then joined to the pouch. Small amounts of food will fill the pouch, which makes the patient feel full quickly. Surgical complications, which are less than 10 percent, may include infection, bleeding, blood clots, internal hernia and bowel obstruction. Neither surgery is a quick fix. “A successful surgery rests in the hands of a competent surgeon,” notes Harmon, “but a successful outcome, which requires a forever-after commitment to strictly following the rules, rests squarely on the shoulders of the patient.”

FIRST ENCOUNTERS

At the initial meeting with patients and their families, Harmon gives a general overview of the bariatric surgery program. His first question—“Do you know what the word ‘compliant’ means?”—is directed at the patient. Many don’t know. “It’s a long, uphill trek before we even come close to entering that last door in the hallway, and sometimes patients and/or their parents are disappointed that surgery is not scheduled immediately,” he says. To be considered for the program, a surgical candidate must: (1) have participated in six or more consecutive months of medically supervised weight management; (2) have reached physiologic/ skeletal maturity; (3) have no evidence of psychological difficulties that would interfere with postsurgical care; (4) show evidence of the ability to comply with medical recommendations; (5) be severely obese, with a BMI greater than 40, with serious obesity-related problems; or have a BMI of greater than 50 with less-severe obesityrelated problems; and (6) have an accessible support system to assist with needs pre- and postsurgery. Since eligibility is decided case by case, it takes at least six months, and sometimes longer, to get to know a patient. All members of the bariatric surgical team—surgeon, endocrinologist, occupational and physical therapists, nutritionists and psychologists— closely monitor the patient and give exercise and diet recommendations. Patients keep a daily diet and exercise log to determine

UB MEDICINE

compliance. Compliance before surgery is a fair predictor of compliance after surgery. Every team member brings a unique perspective to patient eligibility. One might see a possible barrier that no one else caught. “For example, some of us may clear a candidate for surgery,” explains Harmon. “Our psychologist, however, may share that a patient is being treated for depression and is on antidepressants. That’s a red flag and potential disqualifier, because, with the rearrangement of the intestines, the drugs may no longer work. We then revisit the situation as a group.”

FOLLOW-UP IS FOREVER

Harmon says that there is “great value” to having a multidisciplinary program with people who specialize in caring for teenagers. “What strikes me as interesting is that we can have two patients who are almost identical in profile. One will lose weight, the other will not. We can never be 100 percent certain who will turn out to be the best candidates for the surgery, because despite how they seem in person and on paper, our patients are individuals—and teenagers to boot!” Adolescence is marked by an array of age-specific issues associated with normal development: image, identity, self-esteem, relationship building, risk-taking, peer pressure and acceptance. These issues are amplified in obese teens, says Harmon, and exercising extreme self-discipline, while trying to fit in with peers, can be a major hurdle. “Our guiding principle is that bariatric surgery for teens should not occur in isolation, but in an environment that meets their unique physical, medical, behavioral, psychosocial and emotional needs.” After surgery, Harmon says his team sees the patient every two weeks for a few months, after which follow-up visits are scheduled once a month, then once a year. “People are surprised to learn that follow-up is forever.”

IT TAKES A VILLAGE, AND THEN SOME

In 2014, the Journal of the American Medical Association reported that there has been a significant decline—roughly 42 percent— in the obesity rate among preschool-age children over the past decade. Health and fitness programs aimed at young children and families, such as Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move!” initiative, are gradually helping America turn a corner on childhood obesity. Hoping to continue the trend, Harmon

All patients are given exercise recommendations.

recently launched Children’s Healthy Weigh of Buffalo—a comprehensive weight-reduction program designed to provide personalized education and treatment to overweight/obese children and adolescents. Healthy Weigh has a team made up of endocrinologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, psychologists and an adolescent bariatric surgeon, who work in concert at Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo to manage any obesity-related health problems, prevent further weight gain and facilitate major lifestyle changes through behavior modification and support. “We have 200 children enrolled, and about 80 percent have lost weight,” Harmon says. “We’ve had to expand our clinic hours at least three times to meet patient demand.” Harmon says he hopes to add a weight reduction program for the entire family. “I’d like to get the Buffalo public schools on board, too,“ he says. “The

“A successful surgery rests in the hands of a competent surgeon, but a successful outcome, which requires a forever-after commitment to strictly following the rules, rests squarely on the shoulders of the patient.” —Carroll McWilliams Harmon, MD, PhD

more people involved, the greater our chances for success.” Mobilizing teams and resources also benefits communities economically. The National Center for Children in Poverty estimates that the U.S. spends more than $14 billion each year treating overweight adolescents.

“GOOD NEWS” DAYS

It’s a Tuesday and Harmon is waiting to see his next patient—a teenage girl who has been a Healthy Weigh participant for some months. Her mom had a successful bypass surgery for her own obesity issues and encouraged her daughter to do the same. This will be the family’s first meeting with the surgeon.

While Harmon prepares for the visit, a call comes in. The patient has canceled her appointment. “She said she didn’t need to see me, and it was all for the right reasons!” smiles Harmon, who wishes he had more “good news” days like this. “We started by recommending significant lifestyle changes, and she consistently lost weight and her BMI dropped. She felt that with continued support and guidance from our staff, she could continue to do so without the surgery. “We must be doing something right,” he says, confidently, “and we’re only just getting started.” Ellen Goldbaum contributed to this article.

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

21

U B M E D C O L L A B O R AT I O N S

A SURGEON WHO TAKES GIVING TO A NEW LEVEL Helen Cappuccino, MD ’88, receives Distinguished Volunteer Award

By Lori Ferguson

In 2013, Sheryl Sandberg issued her clarion call for women to lean in, spurring a host of conversations about what it means for women to bring their authentic selves to work and commit to realizing their full potential. Breast cancer specialist Helen Cappuccino, MD ’88, was already well ahead of that discussion. A surgical oncologist at Roswell Park Cancer Institute and clinical assistant professor of surgery in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Cappuccino also is the mother of six and a dedicated volunteer at the medical school and in Buffalo. Her giving, however, is not limited to upstate New York. Together with husband Andrew Cappuccino, MD ’88, a spine surgeon and team physician for the Buffalo Bills, Cappuccino has traveled to Africa to do medical mission work and has arranged for children from other countries who need surgery to receive care in the U.S. At Alumni Weekend in April, Cappuccino was presented the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences’ 2016 Distinguished Volunteer Award. Although delighted to have been selected, she says she was “completely caught off guard” by the honor. Such humility characterizes all that Cappuccino does.

22

SUMMER

2016

“I was raised in Lockport and have lived virtually my entire life within a few miles of Buffalo,” she explains. “I attended public schools, then entered UB and was the first person to graduate from the university’s Presidential Honors Program.” After completing her undergraduate degree, Cappuccino attended medical school at UB and completed her residency at New Jersey’s Monmouth Medical Center, the Jersey Shore Memorial Medical Center, and New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. She ran a private general surgical practice in Lockport for over a decade, where she saw “a disproportionate number of women who wanted to see a female surgeon.” In 1999 Cappuccino was recruited to Roswell Park Cancer Institute. “I went to meet with a physician at Roswell to learn how to perform sentinel lymph node biopsies, and we all got along so well that they invited me to join the institute.”

UB MEDICINE

Moved by the opportunity to offer patients access to the comprehensive cancer center’s state-of-the-art treatments and research protocols, Cappuccino accepted the offer. “More than one in nine women will develop breast cancer in their lifetime,” she says, “and I want to do all I can to help them fight the disease.” Cappuccino is equally committed to helping her alma mater. Since graduating, she has worked tirelessly to give back to UB’s medical school, serving as a member of the admissions committee and the Dean’s Council, as well as on the governing board of the Medical Alumni Association, including a term as president in 2007. Cappuccino also chaired the committee that planned and implemented the UBreathe Free initiative, which transitioned the UB campus into a smoke-free environment. “This was a multiyear project that had profound implications for the health and well-being of students, faculty and employees of the university,” she explains. “If just one person fails to start smoking or fails to develop lung cancer, it will have been worth it. I know, however, that many more people will have had a healthful benefit from the lack of smoke on campus.” When asked what motivates her deep commitment to the university, Cappuccino says simply, “UB enabled me to gain an education and be trained, prepared and successful in my field—and I met my husband there!” In addition to her alumni activities, Cappuccino also dedicates considerable time to supporting current medical students, not only because she knows their challenges firsthand, but also because she finds the interactions with the next generation of physicians so fulfilling. “I love working with the students— they’re enthusiastic, idealistic, caring and committed, and it’s wonderful to be a part of their educational journey. It reminds me of what started me on my path as a physician. Any of the volunteer activities that I do for them rewards me as much as it helps them,” she adds. “I remember how hard med school was, and I delight in making the process easier for them in any way I can.” Cappuccino is especially keen to help female physicians who, like her, have chosen nontraditional fields such as surgery. She

“I love working with the students—they’re enthusiastic, idealistic, caring and committed, and it’s wonderful to be a part of their educational journey.” —Helen Cappuccino, MD ’88

cites Ralph Doerr, MD, former chief of surgical oncology at UB, as an important mentor to her. “He was blind to gender and he really encouraged me.” Such support is important, she notes, but it is equally imperative for medical students to have mentors who look like them and have faced similar obstacles. “It helps them to realistically imagine themselves in the field.” To that end, in 2015 Cappuccino helped to found UB DoctHERS, a network of female physicians, scientists, faculty, residents and students who work to support one another and learn from each other’s experiences. “I talk with students about being a surgeon and having a family life, and I hope that this has helped at least a few

of them follow their dreams into surgery without giving up hope for some work-life balance,” she says. “Yet I try to impress upon them that, to a degree, the idea of work-life balance is a myth. Each person must choose his or her own path and go with what personally feels right. I advise them: know yourself, be true to yourself, know your priorities and always have a backup plan.” Outside of the medical school, Cappuccino is active in a number of nonprofit organizations, serving on the board of directors of the University at Buffalo Foundation, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery and the Western New York Women’s Foundation, an organization committed to helping women and young girls achieve self-sufficiency.

The Women’s Foundation position is a new appointment, she notes, and another opportunity for her to promote education in the city. Whatever the cause, the joy and satisfaction that Cappuccino derives from volunteerism is evident. “Buffalo is awesome,” she asserts. “I’ve always had great civic pride in my community, but the changes to downtown and the waterfront are just incredible. It’s a pleasure and an honor to give back to UB and to the community. I feel like I’m a part of something that’s really important. I’d like to think that I’ll live on through my kids,” she concludes, “but helping others is also incredibly rewarding.”

SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

23

APLOMB AT THE CENTER OF THE STORM Jennifer McVige, MD ’05, got the diagnosis right as the nation watched and debated

During that time, 18 girls exhibited symptoms ranging from twitches, seizures and fainting spells to body spasms and involuntary sounds. The recurring behaviors confounded the girls’ parents, school administrators and health officials. By January 2012, the story unfolding in the Town of LeRoy in upstate New York—birthplace of Jell-O gelatin dessert—held the nation’s attention. Environmental activist Erin Brockovich suggested that toxic waste from a 1970 train derailment could be the cause. A New Jersey physician, Rosario Trifiletti, said the girls suffered from a neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infections. But in the end, it was pediatric neurologist Jennifer McVige, MD ’05, and Laszlo Mechtler, MD, medical director of Dent Neurologic Institute, who diagnosed the students with stress-related conversion disorder, which begins with stress, trauma or psychological distress and manifests in physical symptoms. McVige also determined that the girls suffered from mass-psychogenic illness, formerly referred to as mass hysteria. She treated 14 of the 18 teens, and the girls— away from the media spotlight—improved. Today, most of her patients no longer exhibit recurring symptoms. “It was a whirlwind, a complete upheaval of my life,” McVige says. “I had no idea how much I would grow intellectually and emotionally from that experience.”

By Mark SoMMer

Confidence and Perspective McVige grew up on Colvin Avenue in North Buffalo and completed high school at City Honors. She attended the University of Rochester, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in neuropsychology. In her senior year, she went abroad to study for seven months on the island of Lamu, on Kenya’s northern coastline, where she learned Swahili. The experience of being “a pale Irish kid” among Africans in an Islamic culture was life altering, she says. “I used to go to a store and ask at the window for shampoo. I would say, ‘white person shampoo,’ which is what it was called. I remember returning to the States and going into a Rite Aid, and I cried because

24

SUMMER

2016

UB MEDICINE

there was an entire aisle of shampoos. I felt guilty about our excess.” Back in Rochester, McVige worked with an innercity counseling program, studying play therapy for sexually abused children. She then enrolled at UB, where she earned a master’s degree in behavioral neuroscience and psychology and a medical degree. She credits UB medical school with giving her the confidence to withstand the sustained media glare and adversity she recently experienced. “The medical school was amazing,” McVige says. “A lot of the strength and trust in my judgment came from instrumental educators who taught me to believe in myself and to be firm in my values and judgment.” Patricia Duffner, MD ’72, a pediatric neurologist, and Mechtler, an adult neurologist, were critical influences, explains McVige. “Their compassion really made me want to emulate their style of medicine.” After completing a pediatric neurology residency at UB and a fellowship in neurological imaging and headache medicine at Dent Neurologic Institute, McVige worked at a satellite site in Batavia, N.Y., where she was the only pediatric neurologist in a city of 15,000 people. A Rare Diagnosis It was there, in October 2011, that a teen came into her practice after waking up with abnormal movements. McVige thought the symptoms appeared stress-related, along the lines of conversion disorder. It wasn’t unusual, as she typically sees one or two cases a week of the stress-related disorder. “They go blind or can’t walk, or have a tic or twitch in an arm or neck or shoulder or legs, and verbal tics like vocalization,” McVige explains. “It is a subconscious evolution of neurological symptoms. The patients are not aware they’re doing it because it’s not of their own accord.” Another patient came through the following week with similar symptoms. The next week brought another, and most of the others soon followed. They ranged from cheerleaders and athletes to Goth girls and bookworms. While conversion disorders are common, mass psychogenic illness is very rare. Predictably, it

Photo by Douglas Levere

The medical phenomenon began in September 2011, shortly after school resumed at LeRoy Junior-Senior High School, and then largely faded from view after the media spectacle was over the following March.

Jennifer McVige, MD ’05

affected older girls first, starting with tics and moving on to vocalization, like a high-pitched “huh” sound or barking. Then the majority, at different points, passed out. About half had seizure-like shaking spells, and most later developed migraine headaches. McVige treated her patients with cognitive behavioral therapy, psychological intervention and medications. She rejected an environmental explanation because it would have stood to reason that those most vulnerable—the old, the very young and those with compromised immune systems—would be stricken. But that wasn’t the case, since only young and healthy girls were affected. Media and Misinformation A couple of the girls McVige didn’t see went on national television in January and suggested causes for their behavior that were never substantiated. “We lost control when it went to the media,” McVige says. “Everyone was almost better until then. Having the kids on The Today Show, CNN and on social media made it ten times worse.” So did misinformation. “There were things I knew, and that no one else knew, that I couldn’t discuss,” McVige explains. “The crux of this is that it can be a stress-related problem, and they said there was no stress in their lives.” McVige worked closely with Mechtler, who confirmed the diagnosis. Both appeared on CNN with Brockovich’s assistant and with Trifiletti, who attributed the girls’ condition to PANDAS, associated with strep infections. On another occasion, McVige went on the air with Sanjay Gupta, MD, the cable network’s chief medical reporter. She also made frequent appearances on local TV and radio.

“I don’t think I could come up with enough accolades for the job Dr. McVige did. . . . The symptoms went away exactly how she said they would, and when she said they would.” —Father of a patient

Some parents resisted the conversion-disorder diagnosis because they wanted a medical diagnosis—they didn’t like the stigma of a psychological determination, McVige says. Over time, McVige started seeing other girls pivotal to the story and began to “put bigger pieces together.” Grateful Parent “I don’t think I could come up with enough accolades for the job Dr. McVige did,” says the father of one of the girls McVige treated and who requested anonymity to protect his daughter’s identity. “She was incredibly professional and compassionate. My daughter felt comfortable with her, and the level of trust was very high. We concurred with her diagnosis of the conversion disorder because it just made sense. The proof is in the pudding. The symptoms went away exactly how she said they would, and when she said they would.” The phenomenon died down in early 2012, about the time an article about it was published in the New York Times Magazine. The last few girls graduated this June, and “the town no longer wants to talk about it,” says McVige. At least once a year, McVige gets a call from a small town experiencing something similar. SUMMER 2016

UB MEDICINE

25

UB MED DOCTOR VISITS

“I think it’s incredibly important to bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient care.”

Photos by Douglas Levere

“I had excellent teachers and mentors at UB, and I want to pay it forward.”

A HOSPITALIST SPECIALIZING IN PALLIATIVE CARE Rebecca Calabrese, MD, brings her expertise back home 5HEHFFD &DODEUHVH 0' FOLQLFDO DVVLVWDQW SURIHVVRU RI PHGLFLQH EHJDQ ZRUNLQJ DV D L O R I F E R G U S O N KRVSLWDOLVW \HDUV DJR VKRUWO\ DIWHU WKH WHUP ZDV ¿UVW XVHG LQ PHGLFDO OLWHUDWXUH WR PHOTOS BY GH¿QH SK\VLFLDQV ZKR FDUH IRU KRVSLWDOL]HG DOUGLAS SDWLHQWV LEVERE ³, ZDV ZRUNLQJ DV D KRVSLWDOLVW EHIRUH PDQ\ HYHQ FDOOHG LW WKDW ´ VD\V &DODEUHVH ZKR ZDV LQWURGXFHG WR WKH ¿HOG ZKLOH FRPSOHWLQJ KHU LQWHUQDO PHGLFLQH UHVLGHQF\ DW %HWK ,VUDHO 'HDFRQHVV 0HGLFDO &HQWHU :LWKLQ WKH ¿HOG &DODEUHVH KDV GHYHORSHG DQ LQWHUHVW LQ SDOOLDWLYH FDUH ,Q WKLV LQWHUHVW VROLGL¿HG ZKHQ VKH ZDV DSSRLQWHG DVVRFLDWH GLUHFWRU RI KRVSLWDO PHGLFLQH DW %HWK ,VUDHO ³$V LQSDWLHQW GRFWRUV ZH VHH PDQ\ SDWLHQWV ZLWK FKURQLF LOOQHVVHV VXFK DV &23' GLDEHWHV DQG FRQJHVWLYH KHDUW IDLOXUH ZKR ZLOO OLNHO\ EH OLYLQJ ZLWK WKHLU FRQGLWLRQV IRU DQ H[WHQGHG SHULRG RI WLPH ´ VKH H[SODLQV ³7KURXJK SDOOLDWLYH FDUH ZH FDQ KHOS WKHP PDQDJH WKHLU V\PSWRPV DQG PDLQWDLQ WKHLU TXDOLW\ RI OLIH ´ 7KLV FDUH VKH DGGV HQFRPSDVVHV KRVSLFH HQG RI OLIH DQG SDLQ PDQDJHPHQW &DODEUHVH D QDWLYH RI %X̆DOR ZLOO EHJLQ D IHOORZVKLS LQ SDOOLDWLYH FDUH DW 8% LQ 2FWREHU ³, ORYH SDOOLDWLYH PHGLFLQH EHFDXVH LW DOORZV STORIES

26

BY

SUMMER

2016

UB MEDICINE

PH WR HVWDEOLVK UHODWLRQVKLSV ZLWK IDPLOLHV ´ VKH VD\V 6KH LV SDVVLRQDWH DERXW WKH VSHFLDOW\¶V ORQJ WHUP LPSOLFDWLRQV IRU WKH SUDFWLFH RI PHGLFLQH DV ZHOO ³7KH IXWXUH RI KRVSLWDO PHGLFLQH LVQ¶W MXVW LQ KRVSLWDOV EXW DOVR LQ WKH SDWLHQW¶V WUDQVLWLRQ LQWR WKH FRPPXQLW\ , WKLQN LW¶V LQFUHGLEO\ LPSRUWDQW WR EULGJH WKH JDS EHWZHHQ LQSDWLHQW DQG RXWSDWLHQW FDUH ´ &DODEUHVH D JUDGXDWH RI 1HZ <RUN 0HGLFDO &ROOHJH MRLQHG 8%¶V IDFXOW\ LQ 6KH EHJDQ WKLQNLQJ DERXW UHWXUQLQJ WR :HVWHUQ 1HZ <RUN LQ PRWLYDWHG E\ D GHVLUH WR EH FORVHU WR KHU ODUJH IDPLO\ IROORZLQJ WKH DUULYDO RI KHU WZLQV $ IDPLO\ HPHUJHQF\ DFFHOHUDWHG KHU UHWXUQ EXW VKH¶V QHYHUWKHOHVV GHOLJKWHG WR ¿QG KHUVHOI EDFN KRPH ZRUNLQJ DW .DOLHGD +HDOWK¶V %X̆DOR *HQHUDO 0HGLFDO &HQWHU DQG (ULH &RXQW\ 0HGLFDO &HQWHU² ERWK PDMRU 8% WHDFKLQJ ḊOLDWHV²DQG WKH -DFREV 6FKRRO RI 0HGLFLQH DQG %LRPHGLFDO 6FLHQFHV ³7KH H[SDQVLRQ RI WKH PHGLFDO VFKRRO LV ZRQGHUIXO ´ VKH VD\V ³7KH LQVWLWXWLRQ KDV DQ H[FHOOHQW UHSXWDWLRQ²VRPHWKLQJ WKRVH RI XV IURP WKH DUHD KDYH DOZD\V NQRZQ %XW QDWLRQDO UHFRJQLWLRQ LV JURZLQJ DOO WKH WLPH , WKLQN EHIRUH ORQJ ZH¶OO EH D OHDGHU LQ PHGLFLQH DQG SHRSOH ZLOO QR ORQJHU WUDYHO RXWVLGH WKH UHJLRQ IRU FDUH ´ &DODEUHVH LV HTXDOO\ SOHDVHG ZLWK WKH SHUVRQDO RSSRUWXQLWLHV WKDW OLIH LQ %X̆DOR D̆RUGV KHU DQG KHU IDPLO\ ³7KLV WRZQ KDV UHDOO\ DUULYHG ´ VKH VD\V ³7KH DUFKLWHFWXUH LV EHDXWLIXO WKH UHVWDXUDQW VFHQH LV H[FLWLQJ DQG WKH TXDOLW\ RI OLIH LV KDUG WR EHDW %X̆DOR LV WRS QRWFK , UHDOO\ EHOLHYH LQ WKLV FLW\ ´

A PEDIATRICIAN DEDICATED TO GIVING BACK Daniel W. Sheehan, PhD ’89, MD, knows the value of mentoring ,I \RX ZHUH WR DWWULEXWH D PRWWR WR SHGLDWULF SXOPRQRORJLVW 'DQLHO 6KHHKDQ 0' 3K' ¶ LW ZRXOG EH ³SD\ LW IRUZDUG ´ 7KH FRQFHSW JXLGHV HYHU\WKLQJ KH GRHV IURP SURYLGLQJ FDUH WR \RXQJ SDWLHQWV WR WHDFKLQJ WKH QH[W JHQHUDWLRQ RI SK\VLFLDQV $ QDWLYH RI 2OHDQ 1 < 6KHHKDQ FDPH WR PHGLFLQH VRPHZKDW ODWHU LQ OLIH WKDQ PRVW RI KLV SHHUV $IWHU FRPSOHWLQJ D 3K' LQ SK\VLRORJ\ DW 8% DQG HQWHULQJ D SRVWGRFWRUDO UHVHDUFK IHOORZVKLS DW -RKQV +RSNLQV 8QLYHUVLW\ KH H[SHULHQFHG ³D PLGOLIH FULVLV DW DJH ´ ZKHQ KLV IDWKHU VXGGHQO\ GLHG 7KLV ORVV²DQG VXEVHTXHQW UHÀHFWLRQV RQ KLV IDWKHU¶V OLIH²LQVSLUHG 6KHHKDQ WR VWD\ DW -RKQV +RSNLQV DQG HDUQ D PHGLFDO GHJUHH $IWHU FRPSOHWLQJ D SHGLDWULF UHVLGHQF\ DQG SHGLDWULF SXOPRQRORJ\ IHOORZVKLS DW &KLOGUHQ¶V +RVSLWDO RI 3LWWVEXUJK KH DFFHSWHG D SRVLWLRQ DW 7KH 2KLR 6WDWH 8QLYHUVLW\ ,Q KH UHWXUQHG WR 8% MRLQLQJ WKH IDFXOW\ LQ WKH 'HSDUWPHQW RI 3HGLDWULFV LQ WKH 'LYLVLRQ RI 3XOPRQRORJ\ )URP WR KH VHUYHG DV FKLHI RI WKH GLYLVLRQ 6KHHKDQ GHGLFDWHV KLPVHOI WR D YDULHW\ RI HQGHDYRUV DERXW ZKLFK KH FDUHV GHHSO\ ,Q DGGLWLRQ WR WUHDWLQJ \RXQJ SDWLHQWV ZLWK SXOPRQDU\ GLVHDVHV DW :RPHQ DQG &KLOGUHQ¶V +RVSLWDO RI %X̆DOR D 8% WHDFKLQJ ḊOLDWH KH FROODERUDWHV ZLWK WKH &HQWHUV IRU 'LVHDVH &RQWURO DQG 3UHYHQWLRQ WR UHVHDUFK DQG GHYHORS JXLGHOLQHV WR LPSURYH UHVSLUDWRU\ FDUH IRU LQGLYLGXDOV ZLWK 'XFKHQQH DQG %HFNHU PXVFXODU G\VWURSKLHV $Q DVVRFLDWH SURIHVVRU RI SHGLDWULFV 6KHHKDQ