No. 35, Summer 2024 A TwoMorrows Publication

ALSO: Celebrating Arnold Drake at 100!

characters TM & © DC

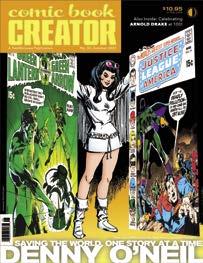

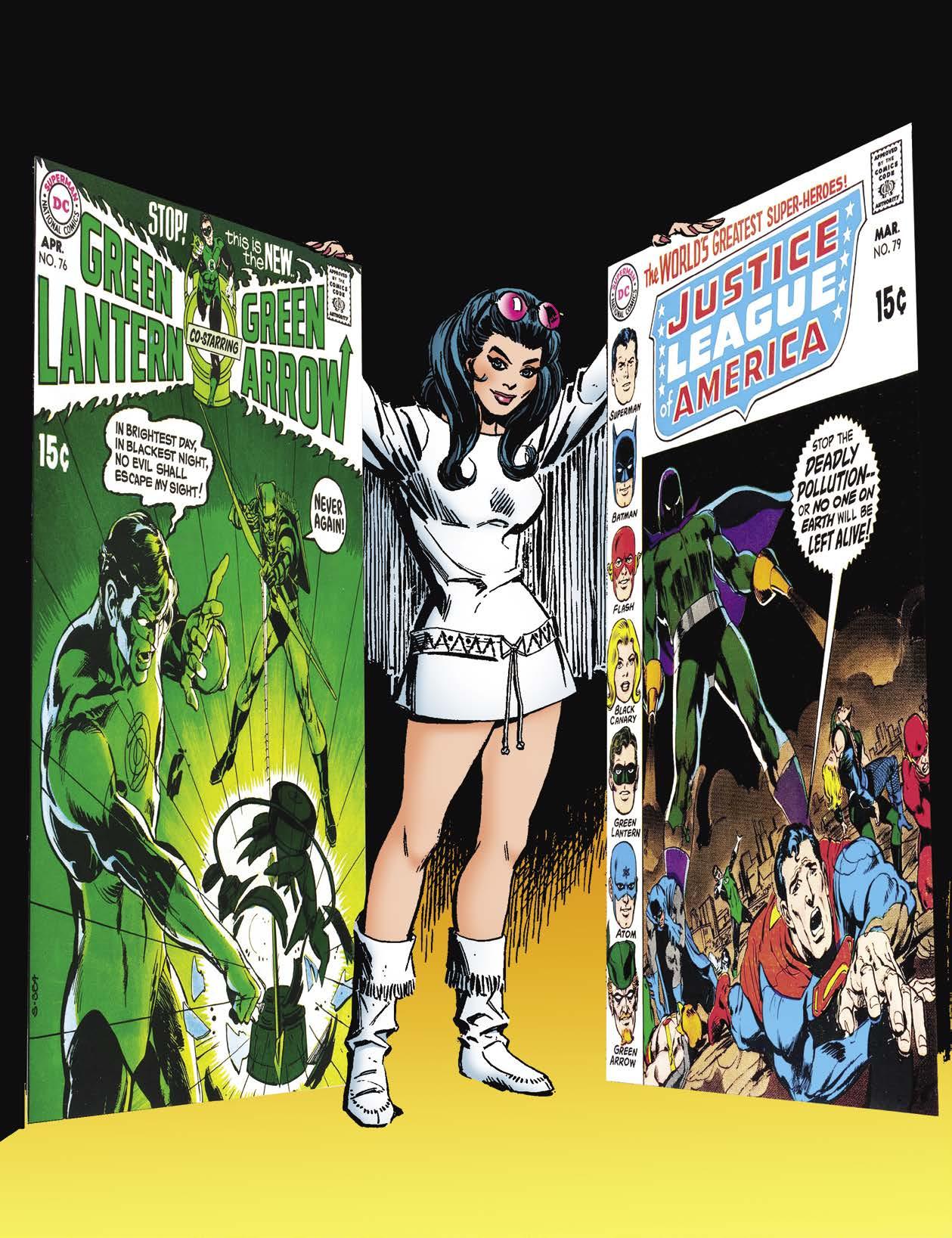

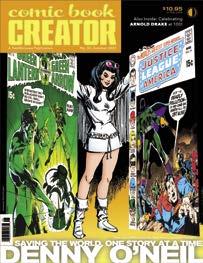

Cover art by Mike Sekowsky, Neal Adams, and Dick Giordano

All

Comics.

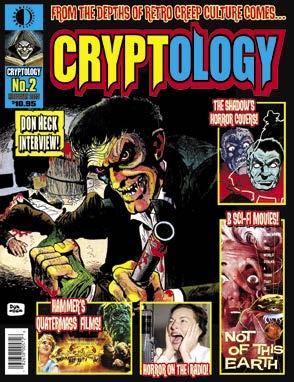

“Greetings, creep culturists! For my debut issue, I, the CRYPTOLOGIST (with the help of FROM THE TOMB editor PETER NORMANTON), have exhumed the worst Horror Comics excesses of the 1950s, Killer “B” movies to die for, and the creepiest, kookiest toys that crossed your boney little fingers as a child! But wait... do you dare enter the House of Usher, or choose sides in the skirmish between the Addams Family and The Munsters?! Can you stand to gaze at Warren magazine frontispieces by this issue’s cover artist BERNIE WRIGHTSON, or spend some Hammer Time with that studio’s most frightening films? And if Atlas pre-Code covers or terrifying science-fiction are more than you can take, stay away! All this, and more, is lurching toward you in TwoMorrows Publishing’s latest, and most decrepit, magazine—just for retro horror fans, and featuring my henchmen WILL MURRAY, MARK VOGER, BARRY FORSHAW, TIM LEESE, PETE VON SHOLLY, and STEVE and MICHAEL KRONENBERG!”

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99

#1 ships October 2024!

CRYPTOLOGY #2

The Cryptologist and his ghastly little band have cooked up more grisly morsels, including: ROGER HILL’s conversation with our diabolical cover artist DON HECK, severed hand films, pre-Code comic book terrors, the otherworldly horrors of Hammer’s Quatermass, another Killer “B” movie classic, plus spooky old radio shows, and the horror-inspired covers of the Shadow’s own comic book. Start the ghoul-year with retro-horror done right by FORSHAW, the KRONENBERGS, LEESE, RICHARD HAND, VON SHOLLY, and editor PETER NORMANTON

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95

(Digital Edition) $4.99 • Ships January 2025

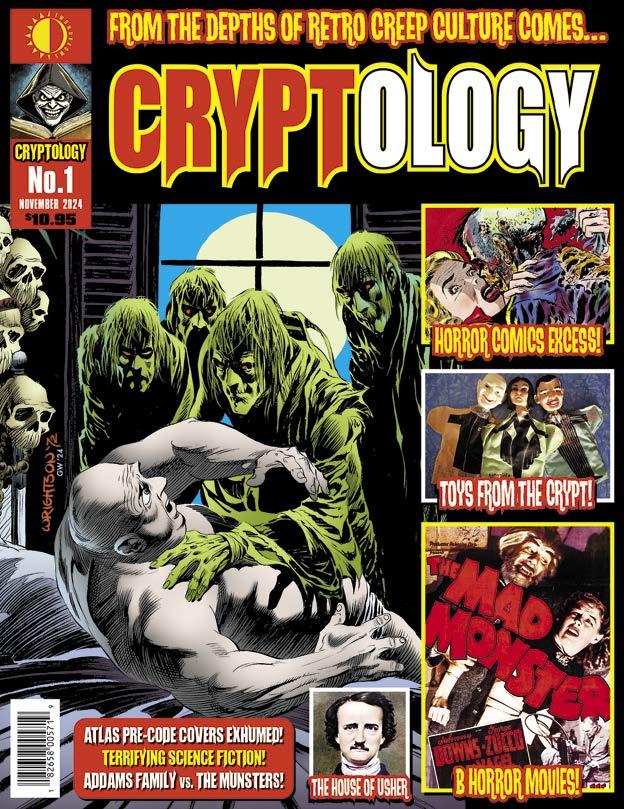

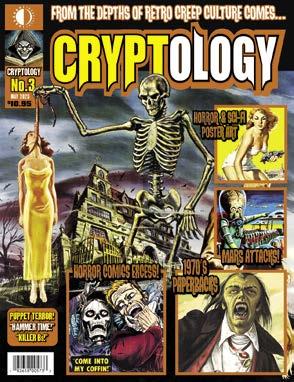

CRYPTOLOGY #3

This third wretched issue inflicts the dread of MARS ATTACKS upon you—the banned cards, the model kits, the despicable comics, and a few words from the film’s deranged storyboard artist PETE VON SHOLLY! The chilling poster art of REYNOLD BROWN gets brought up from the Cryptologist’s vault, along with a host of terrifying puppets from film, and more comic books they’d prefer you forget! Plus, more Hammer Time, JUSTIN MARRIOT on obscure ’70s fear-filled paperbacks, another Killer “B” film, and more to satiate your sinister side!

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95

(Digital Edition) $4.99 • Ships April 2025

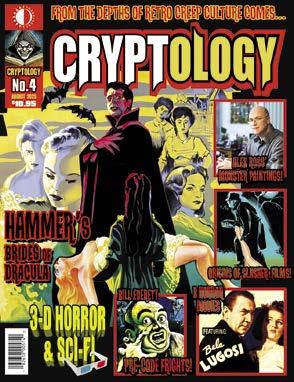

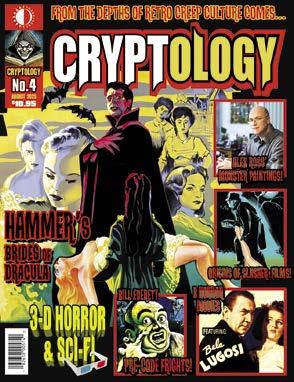

CRYPTOLOGY #4

Our fourth putrid tome treats you to ALEX ROSS’ gory lowdown on his Universal Monsters paintings! Hammer Time brings you face-to-face with the “Brides of Dracula”, and the Cryptologist resurrects 3-D horror movies and comics of the 1950s! Learn the origins of slasher films, and chill to the pre-Code artwork of Atlas’ BILL EVERETT and ACG’s 3-D maestro HARRY LAZARUS. Plus, another Killer “B” movie and more awaits retro horror fans, by NORMANTON, the KRONENBERGS, LEESE, VOGER, and VON SHOLLY!

Ships

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 •

July 2025

All characters and properties TM & © their respective owners.

TwoMorrows. The Future of Comics History. TwoMorrows Publishing 10407 Bedfordtown Drive Raleigh, NC 27614 USA 919-449-0344 E-mail: store@twomorrows.com Order at twomorrows.com Horror Four-issue subscriptions: $53 in the US $78 International $19 Digital Only

Satiate Your Sinister Side!

One Story at a Time

1960s/early ’70s

before him, launching an age of relevancy into the art

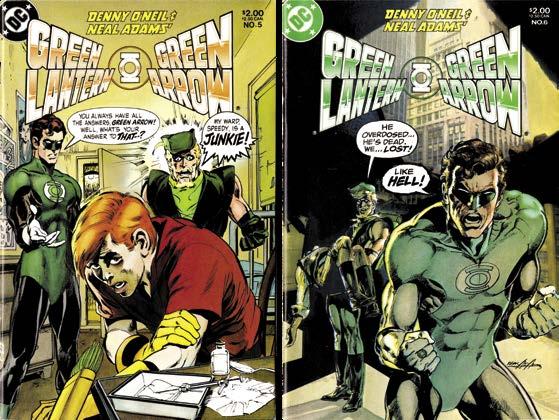

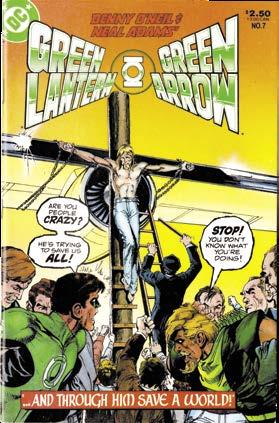

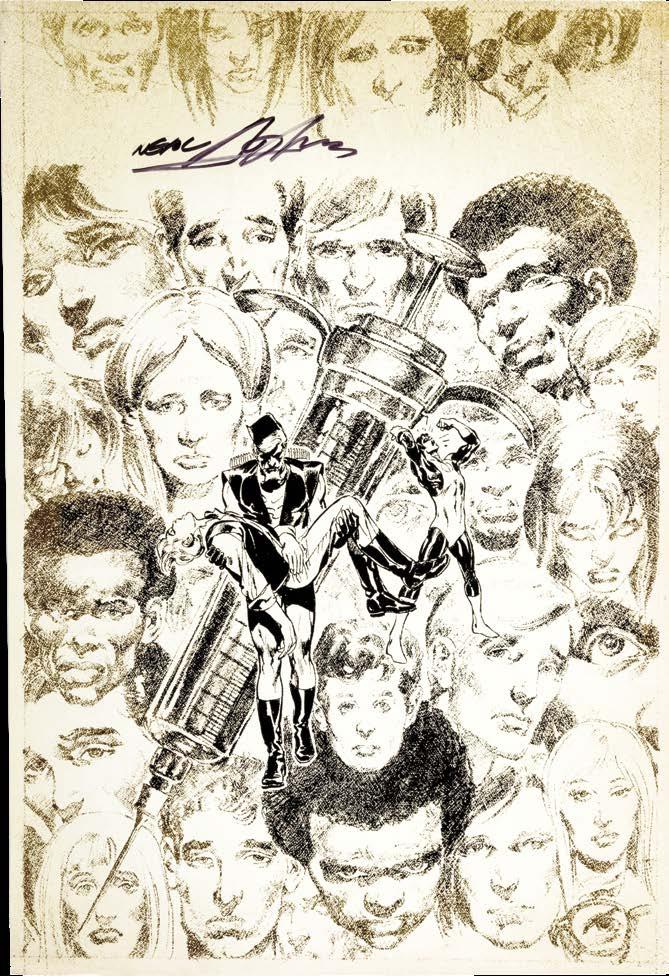

Also included are “Ten from Den,” Brodsky’s picks for the best of O’Neil’s work from that era

BACK MATTER

EDITOR’S NOTE: We intended to include an article on "Studio Zero," the circa 1974 Berkeley studio shared by Jim Starlin, Alan Weiss, and others, but that is postponed to a future issue. Also note that some images in this issue have been enhanced with software.

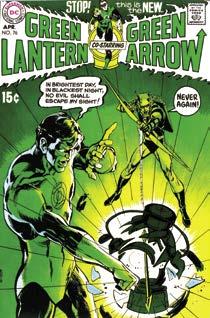

Right: There’s minor digital manipulation in this detail of Green Lantern #83 [May 1971] cover. Art by Neal Adams.

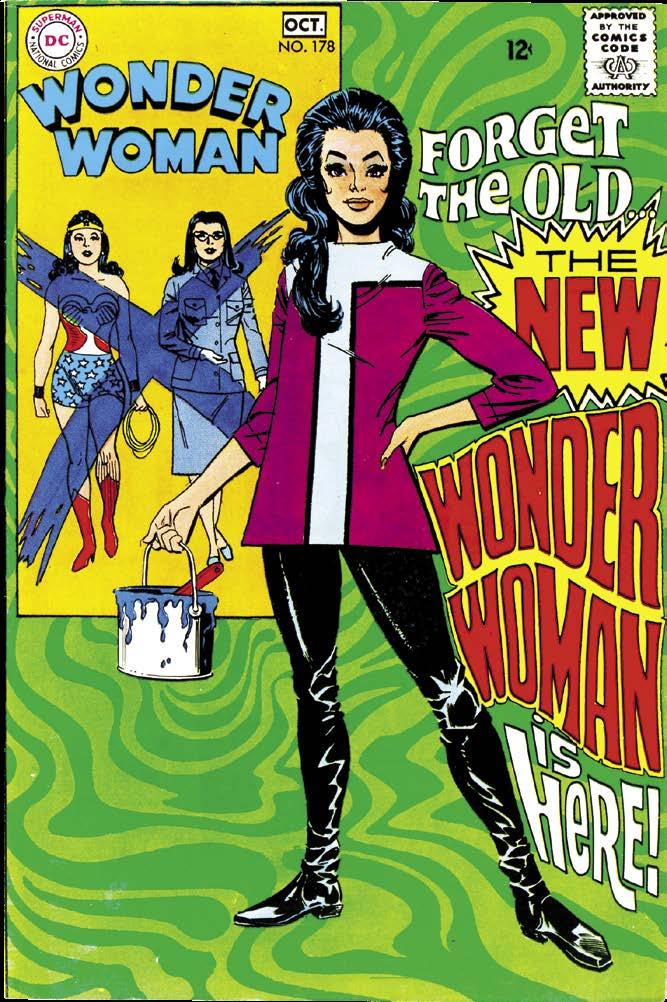

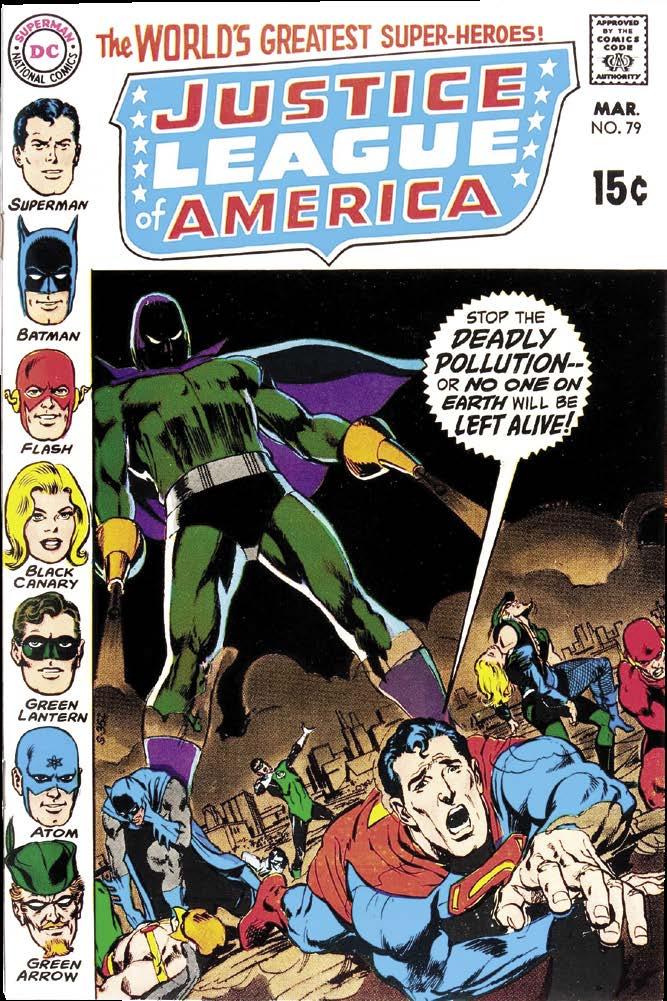

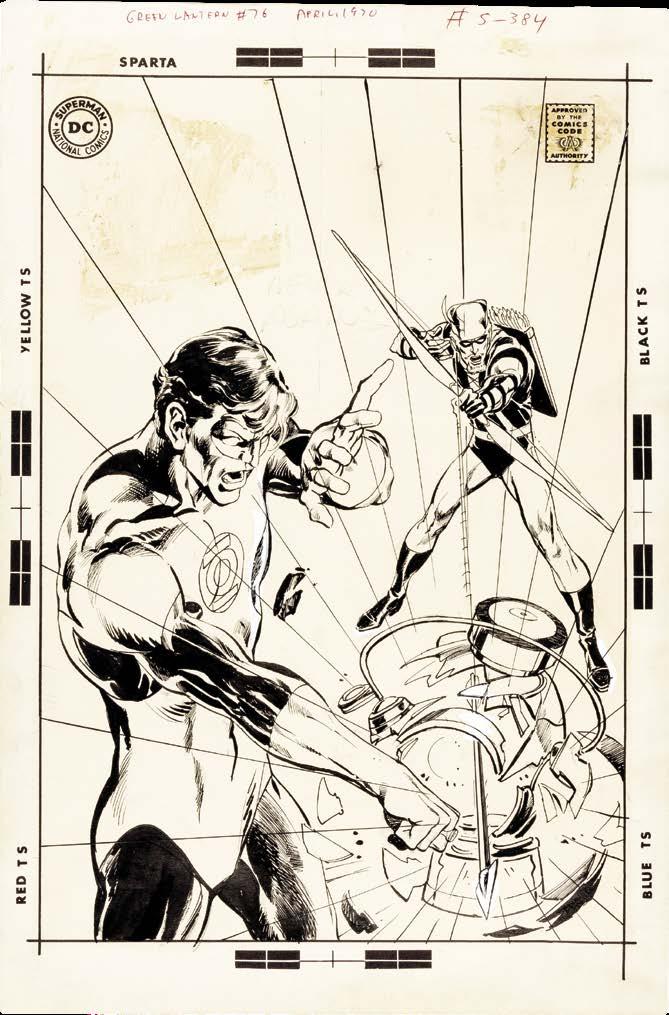

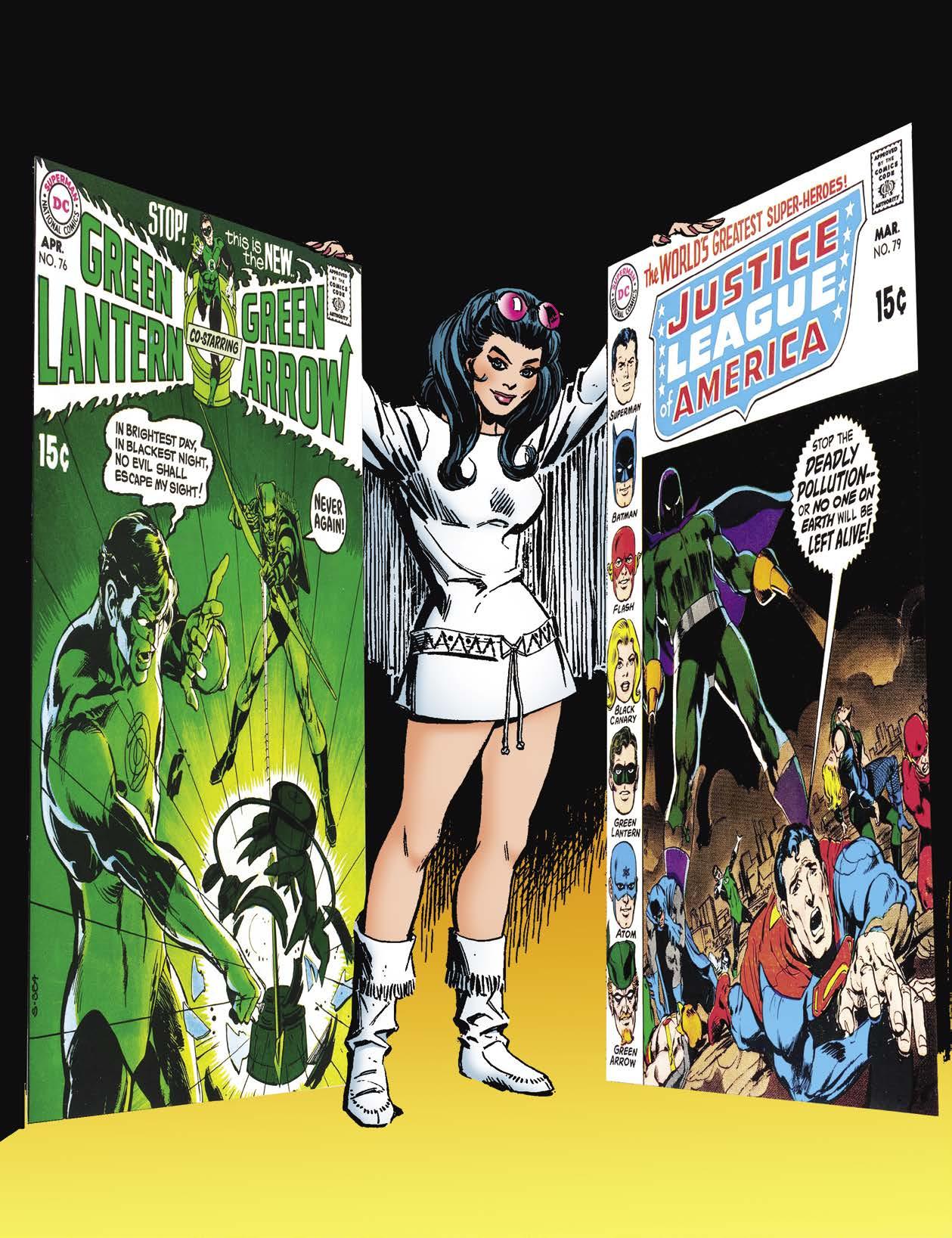

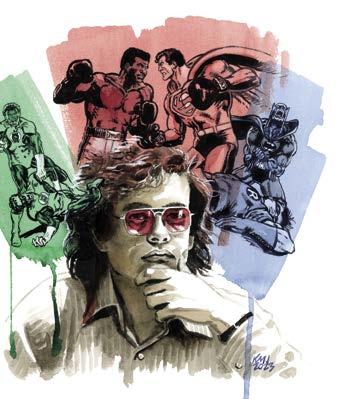

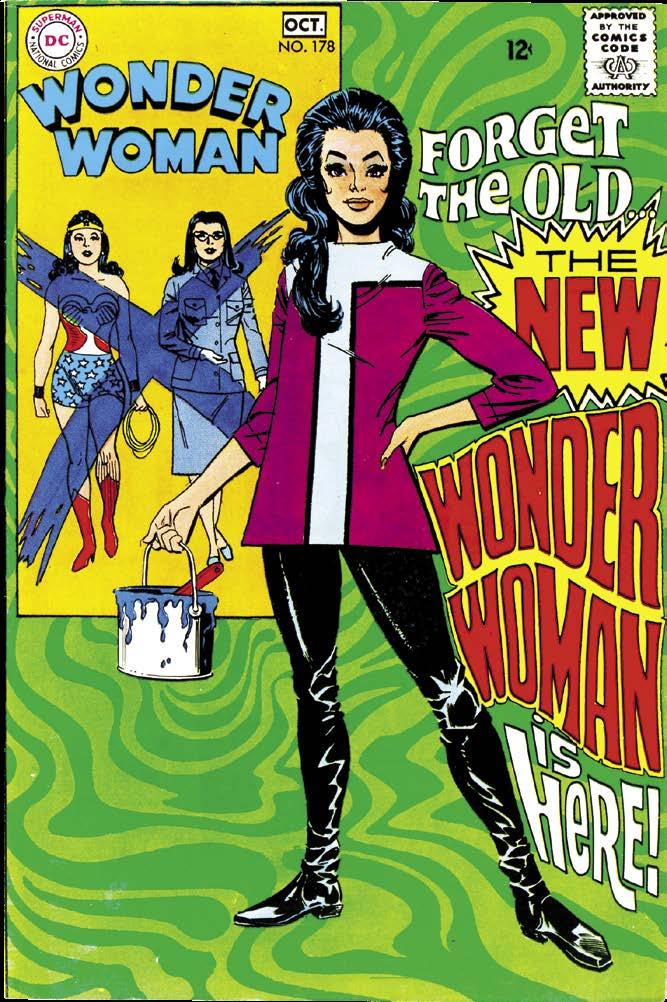

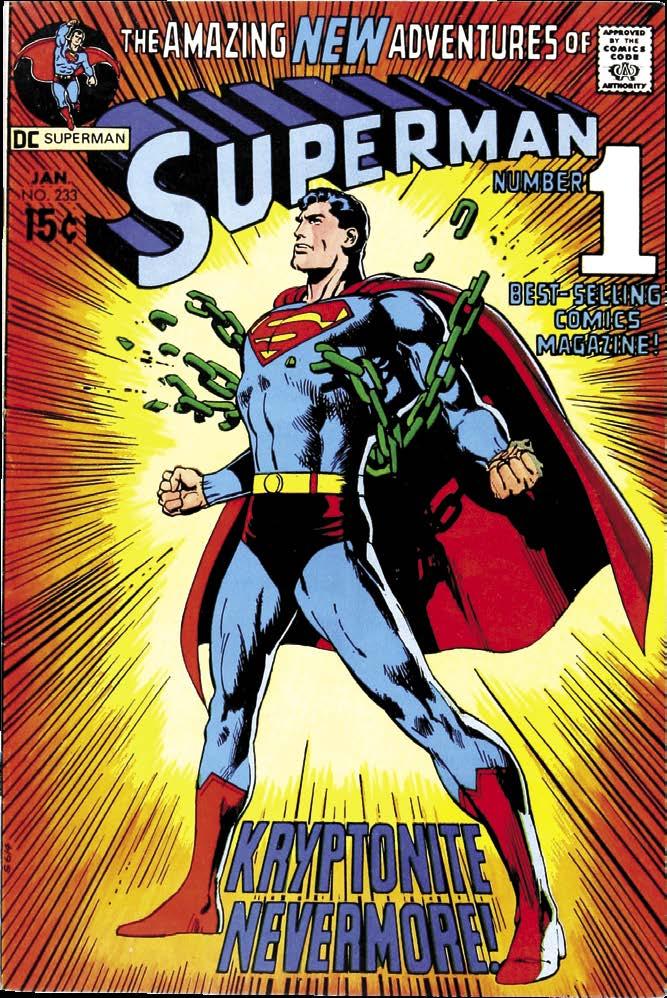

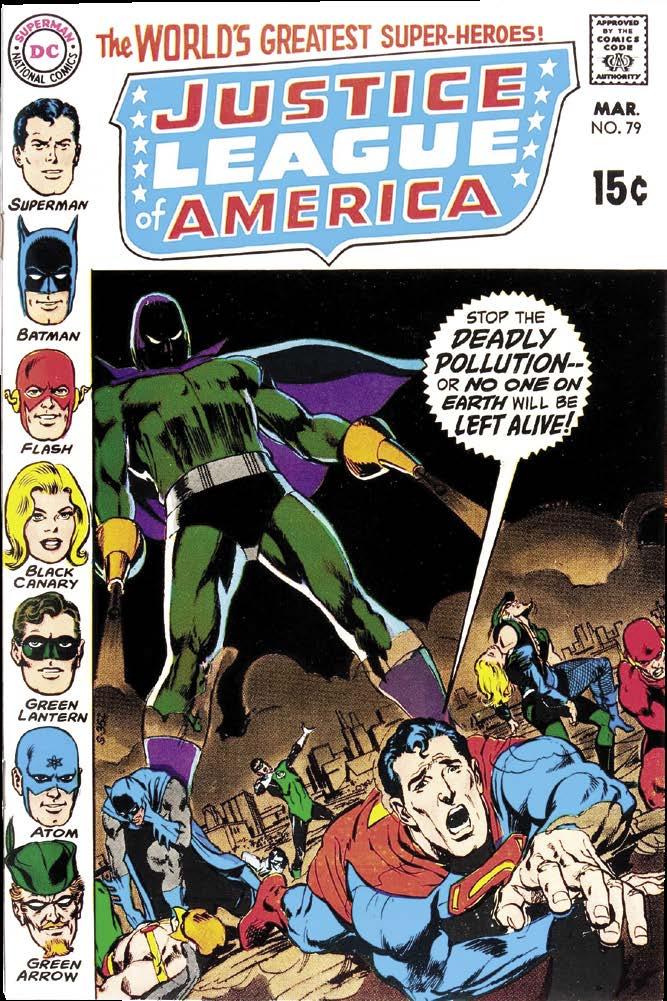

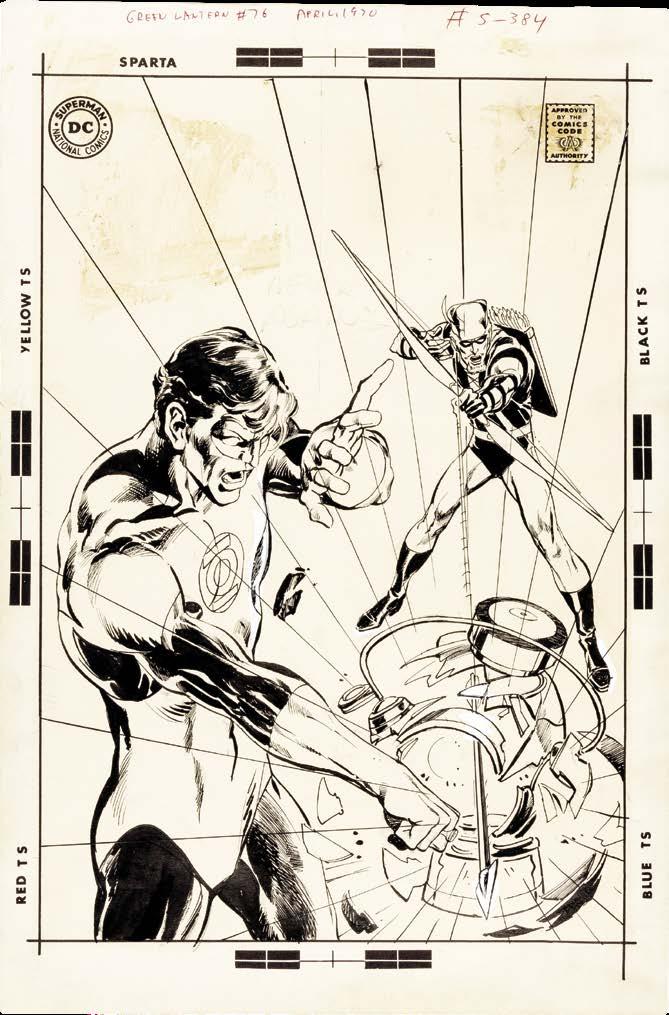

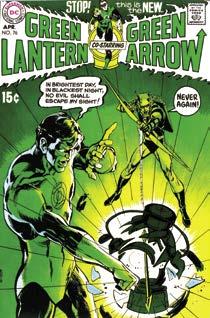

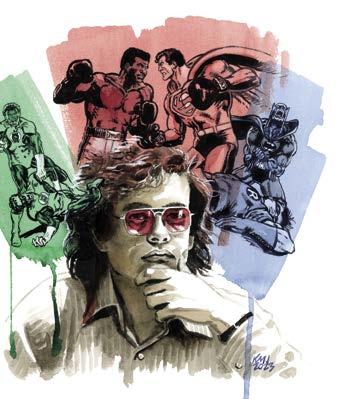

Comic Book Creator ™ is published quarterly by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Dr., Raleigh, NC 27614 USA. Phone: (919) 449-0344. Jon B. Cooke, editor. John Morrow, publisher. Comic Book Creator editorial offices: P.O. Box 601, West Kingston, RI 02892 USA. E-mail: jonbcooke@aol.com. Send subscription funds to TwoMorrows, NOT to the editorial offices. Four-issue subscriptions: $53 US, $78 International, $19 Digital. All characters are © their respective copyright owners. All material © their creators unless otherwise noted. All editorial matter ©2024 Jon B. Cooke/ TwoMorrows. Comic Book Creator is a TM of Jon B. Cooke/TwoMorrows. ISSN 2330-2437. Printed in China. FIRST PRINTING. Above: We combine penciler Mike Sekowsky and inker Dick Giordano’s Wonder Woman #191 [Dec. 1970] cover figure with Green Lantern #76 [Apr. ’70] and Justice League of America #79 [Mar. ’70], both sporting pencils and inks by Neal Adams. Summer 2024 • The Denny O’Neil Issue • Number 35 DENNY O’NEIL Portrait by KEN MEYER, JR. ©2024 Ken Meyer, Jr. Superman, associated characters TM & © DC Comics. TM & ©DC Comics. About Our Cover Cover art by MIKE SEKOWSKY & NEAL ADAMS, Pencils DICK GIORDANO & NEAL ADAMS, Inks Cover colors by GLEN WHITMORE

Ye Ed’s Rant: Yours truly confesses to an endless ’70s comics obsession and loving it! 2 COMICS CHATTER Incorrect: The Tragic Saga of George Caragonne: Bob Levin investigates the sad story of the Penthouse Comix creator/editor from his humble start to spectacular end 3 Arnold Drake at 100: The late, great author in part one of his career-spanning talk ...... 12 Once Upon Long Ago: Steve Thompson on his admiration for Harvey Kurtzman ........... 27 The Super Hero’s Journey: Patrick “Mutts” McDonnell on his “love letter” to comics 30 Tim Hensley: A conversation with the alternative cartoonist on his smart, fun comics 34 Mr. Butterworth: And we assumed Jack just wrote a bunch of Warren stories! Zounds! 38 Incoming: We empty our overflowing mailbag and suffer the slings and arrows 46 Cooke’s Column: Horrors! Jay Stephens gets terrifyingly cute with Dwellings! 49 Comics in the Library: Richard Arndt speaks of John Law, Will Eisner’s Lawman 51 Ten Questions: Darrick Patrick gets the scoop from writer W. Maxwell Prince 52 Hembeck’s Dateline: Zatanna is telling Fred that Magicman is full of “Yekralam!” 53

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Denny O’Neil:

With a focus on his

comic book scripts,

of

54

THE MAIN EVENT

Saving the World,

Bob Brodsky, onetime editor

fanzine The O’Neil Observer, takes a close examination — with Ye Editor — of the ground-breaking, topical work and life of Dennis Joseph O’Neil [1939–2020], the most important writer of his time in American comics. His collaborations with Neal Adams on Green Lantern/Green Arrow injected real life into the super-hero as none

form.

Creators at the Con: Kendall Whitehouse clix pix at the NYCC Ghost Machine panel 78 Coming Attractions: Greg Biga compiles an epic tribute to the late Tom

79 A Picture Is Worth A Thousand Words: Tom Z. shares rarely-seen George Pérez art 80

Palmer

COMIC BOOK CREATOR is a proud joint production of Jon B. Cooke/TwoMorrows Comic Book Artist Vol. 1 & 2 are available as digital downloads from twomorrows.com C’mon citizen, DO THE RIGHT THING! A Mom & Pop publisher like us needs every sale just to survive! DON’T DOWNLOAD OR READ ILLEGAL COPIES ONLINE! Buy affordable, legal downloads only at www.twomorrows.com or through our Apple and Google Apps! & DON’T SHARE THEM WITH FRIENDS OR POST THEM ONLINE. Help us keep producing great publications like this one! Don’t STEAL our Digital Editions!

Incorrect

by BOB LEVIN

[Preliminary Note: None of the four individuals to whom I wrote, emailed and/or phoned, having reasonably determined them related to my subject, George Caragonne, responded, leaving me short of details of his childhood and adolescence. Plus, by most accounts, Caragonne didn’t like to talk about himself. Perhaps he didn’t want people to know about him. Perhaps they would believe him cooler than he was.

Little in the way of contemporary written accounts about Caragonne exist. Many people who worked or socialized with him as an adult did not wish to revisit those years. When people did speak to me, often at length and with great generosity, I was hearing recollections of 30-year-old memories. If two people had knowledge of an event, I was likely to hear two versions of it. If three had knowledge, I would hear three.

Keep this is mind as you go through this article — and life.

— B.L.]

If it is true, as Shakespeare has Malcolm say of Cawdor in Macbeth, “Nothing in his life quite became him as his leaving it,” it is equally true that nothing so distorted George Caragonne’s as his exiting his.

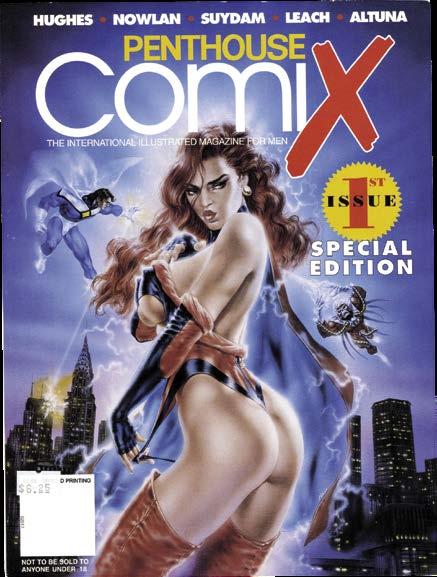

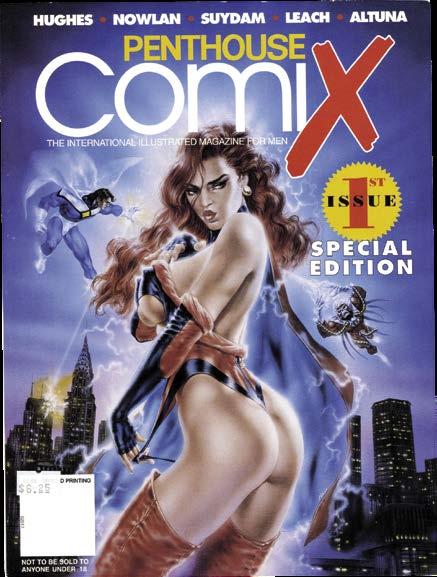

On Thursday, July 20, 1995, the 29-year-old, six-foot-four, 450-pound Texan, who had edited the X-rated, bi-monthly Penthouse Comix since its inception shortly over a year before, asked a bellhop at the Marriott Marquis Hotel, in Times Square, for its height. Forty-five stories, he was told. After being assured that it was the tallest building in the area, Caragonne entered an elevator.

He was casually dressed. He carried a bag containing two stereo speakers connected to a Walkman playing themes from James Bond movies. (He, it should be noted, identified with the villains,

The strange, tragic, and terrible story of George Caragonne, Penthouse Comix editor

not Bond.) He got off on the top floor, where an atrium provided a direct view of a food court 500 feet below, where dozens of tourists congregated. He climbed over a railing.

“Get off!” a maid called.

He jumped, tumbling, striking a glass elevator shaft of his way down, his speed nearly 180 miles-per-hour when he landed. One spectator described a “thud, louder than a shotgun blast.” It seemed, another said, “The ceiling was coming down.” Glass shattered; debris flew. The staff shepherded people outside and spread blankets to block the scene from view. “He didn’t just die,” one person put it. “He exploded.”

A conventioneer in town from Tucson told the Daily News, “They handled it pretty professionally. On the West Coast, everybody would have freaked out. But here, this being New York, they asked people to move along so business could continue as usual.” One person was taken to a hospital for shock. Others, including children, it has been said, were in therapy for months, if not years.

This page:

The death would have been unimaginable by anyone who had only known the Caragonne of a few years before. But not those who had been around him the preceding months. Mark Evanier, a comics writer and friend of Caragonne’s for a decade, told The Comics Journal shortly after his death that he would have been more surprised if Caragonne had killed himself “in a small, quiet way… It was not unprecedented for George to do something big and immensely messy.” He speculated Caragonne may have even timed his death to make it the talk of the upcoming San Diego Comics Con.

I.

George Caragonne was born September 16, 1965, in San Antonio, Texas. His father, an architect, left the family when George was young. He was disdainful of — and disrespectful toward — his son, who would grow up determined to impress him.

Caragonne’s mother, a Jehovah’s Witness, was tiny — fivefeet-tall, 100-pounds — and rigidly devout. She made sure her son went to church every Sunday. He was a choirboy until he was 18. He passed out leaflets door-to-door. He neither smoked nor drank. But his behavior grew so beyond her control that, when he was 13, she set him up in his own apartment and ordered him from the house. Or so he claimed. Some believe this a representative Caragonne exaggeration, designed to increase his outlaw image. Even if it was a fantasized expulsion, it provides an instructive glimpse into his feelings about himself.

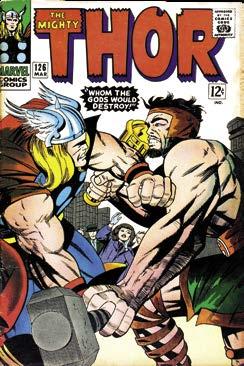

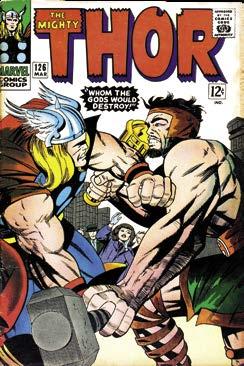

His passion was comic books. This passion ran deep and unswerving. In adulthood, if asked his favorite, Caragonne would exclaim, “Thor 126,” recite all the words of “Thor vs. Hercules,” including cover copy, and act out all the action. (Or so one person recollects. Others say he would recite no more than three panels containing, perhaps, nine word balloons.)

up front

COMIC BOOK CREATOR • Summer 2024 • #35

Photo courtesy of Dave Elliott. Penthouse Comix TM & © General Media Communications, Inc. Thor TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.

3

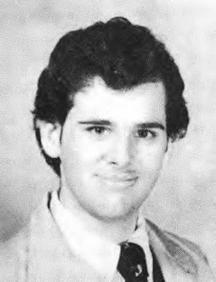

Above is George Caragonne during his time at Penthouse Comix. Inset left, the first issue [June 1994]. Below is caricature of the editor from the New York Observer. Bottom is George’s favorite comic book, Thor #126 [Mar. 1966].

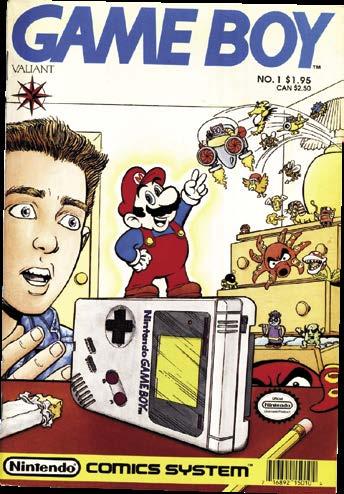

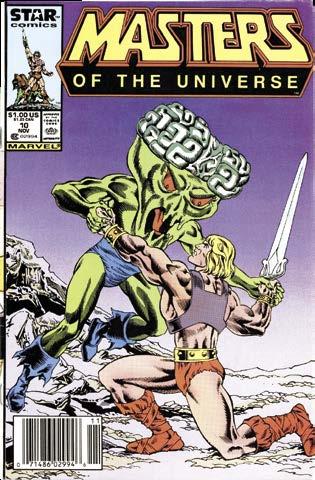

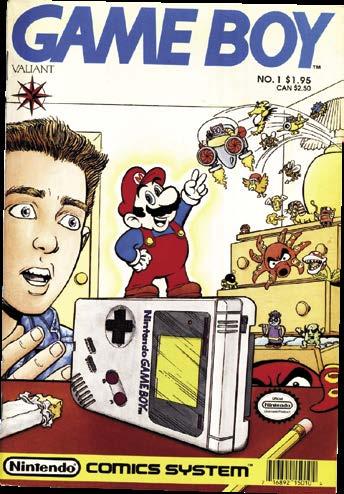

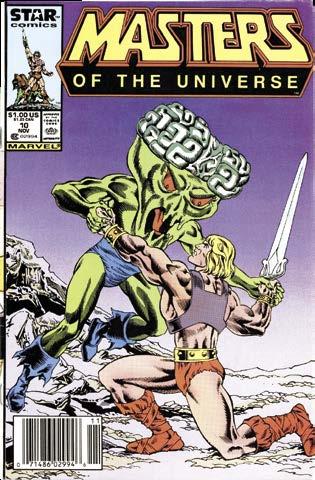

This page: Above is George’s 1982 senior class portrait, Alamo Heights High School, San Antonio, Texas. Below is a caricature of the man from his Star Comics days, which appeared in Care Bears #15 [Mar. ’88], illustrating biographical bullet points for the "Starry-Eyed Purveyor of Fancy and Fantasy (i.e., writer)." At bottom are covers to Masters of the Universe #10 [Nov. ’87] and Game Boy #1 [1990].

“A big, goofy, friendly guy,” says Buzz Dixon, who became a consulting editor (or, depending on the masthead, über-editor), at Comix late in Caragonne’s tenure, when describing him in the late 1980s.

“A big kid, billowing with energy and excitement,” says Eliot Brown, the magazine’s technical/science editor, recalling a young Caragonne, in blue suit and red tie, coming into Marvel Comics’ offices, asking the size of Daredevil’s apartment for a role-playing game he was designing. “A sweet, young soul.”

“A sweet, little guy. Well, not little,” says Evanier of the Caragonne he met at meetings of the L.A.-based Comic Arts Professional Society, a rookie thrilled to be among seniors he admired.

“A bombastic, big hearted, larger than life person,” says Dave Elliott, Comix art editor, “He always seemed happy. He could have played Santa Claus. A loud one. A loud Texan one.” Drugs, Dixon says, turned him “from Santa into Satan.”

II.

In terms of professional comics, Caragonne’s “origin” story begins with him sending an unsolicited story to Marvel Comics, in 1984. Over the next four years, he freelanced scripts for its ancillary books, like Masters of the Universe, Planet Terry, and Thundercats, under the mentoring of Jim Shooter, the company’s editor-in-chief. In 1988, after being fired by Marvel, Shooter launched Valiant Comics, in New York City, and, unasked, Caragonne drove cross-country and offered to work for him. Stan Lee, Marvel’s head, had been a god to Caragonne, and Shooter had supplanted him.

Shooter gave him work on Captain N, The Legend of Zelda, and Punch-Out!! and, Caragonne told friends, promised him the job of writing the more prestigious Magnus, Robot Fighter once he acquired the license. Shooter got the license, but Caragonne did not get the book. (Shooter neither confirms nor denies this promise.) If it happened, it was a “betrayal” Caragonne never got over.

Between Marvel and Valiant, Caragonne had too much work to leave New York but was not earning enough to live there. While scrambling to make it in comics, he found employment as a salesclerk with Big Apple Comics, at 92nd and Broadway, eventually becoming a “day-to-day” manager. He

was knowledgeable and likable, with a need to impress. Pete Koch, the store’s owner, recalls, “He had strong opinions about things that didn’t require strong opinions.”

He was also still so straight that when he joined Koch and some comic industry people visiting from England for a night out, it was Caragonne’s first time in a bar. “Are you sure this is a good idea?” he’d said. “You bet,” they’d answered.

“Isn’t sobriety to be valued?” he asked, ordering a Diet Coke. “Not at all,” they replied.

“Well, you wouldn’t do drugs, would you?” he went on. “Massive quantities,” they answered.

“George’s eyes rolled up into his head,” says Scott Dunbier, then a dealer in comic art. “These were his friends and he could not believe friends of his did drugs.”

Caragonne was so sober he became the person trusted to keep Big Apple open on Christmas. (It helped since, as a Jehovah’s Witness, it was not a real holiday.)

He had begun smoking though.

III.

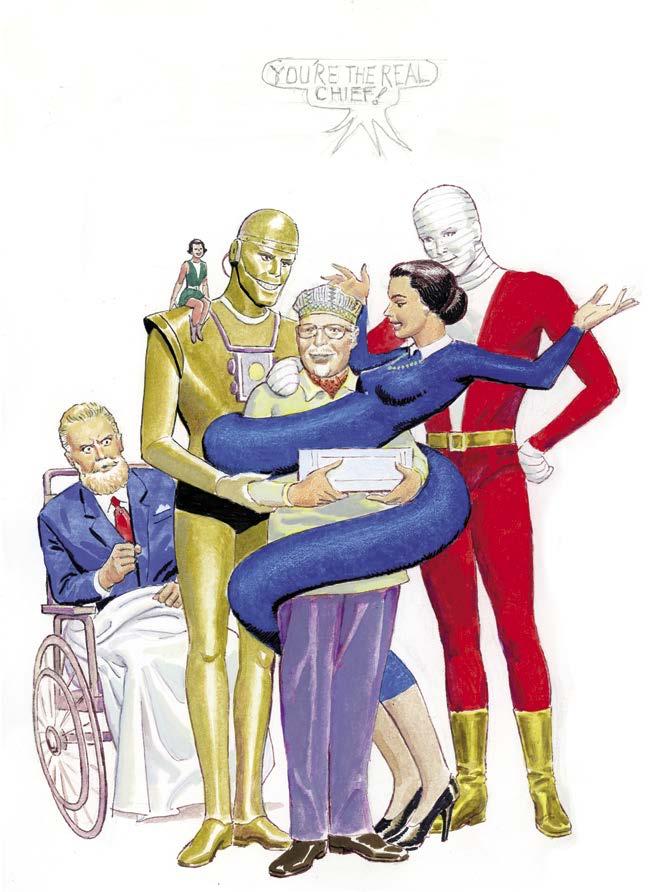

Stories differ as to how Caragonne got to Penthouse. One is that, while trying to start his own publishing company, Constant Developments, Inc., he had acquired the rights to T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents, a super-hero comic, created in the mid’60s by Len Brown and Wally Wood, which had passed through several hands since, and tried to interest Bob Guccione, publisher of Penthouse in it. Another is that Caragonne and a partner (or partners) had an idea for a new line of super-hero comics which they presented as a package to several publishers and, after being roundly rejected, drew up an R-rated version to pitch to Guccione. A third, Tim Pilcher in Erotic Comics [2008], has Caragonne compiling a list “of every magazine published in America… [and] offering to create a comic book version of [it].”

Only Guccione arranged a meet.

The 64-year-old, Brooklyn native, who had once worked as a newspaper and greeting card cartoonist, loved comics. He had begun Penthouse in London, in 1965 and brought it to the United States four years later. By combining photos of full-frontal nudity with a commitment to investigative journalistic that won him national awards, he had created a publication more attuned to the increasingly edgy times than, say, Playboy and become worth in excess of $400 million. He had produced the widely banned but ultimately profitable feature film, Caligula, starring Malcolm McDowell, and published Viva, an erotic magazine for women, and Omni, a science/sci-fi mag. He owned “The Willows,” a 2,000-acre ranch in Staatsburg, New York, whose trees and shrubs had been shaped to resemble those of an English lord’s manor. Peacocks and Russian wolfhounds roamed free, and the main house housed the art of a Medici prince.

Guccione had spent enough years in Europe to be accustomed to the idea of telling adult stories in graphic form. Some sources say Guccione had already offered several comics industry veterans the chance to run a section of erotic comics within Penthouse, but they had declined. Now he offered the job to Carragone. Wikipedia says that, after a several month trial, Guccione decided a stand-alone comic magazine would work. But others say it was not a “trial,” but a “preview,” and that Guccione had always planned on a magazine.

Still others think the idea originated with Caragonne. Kathy Keeton, once one of London’s highest paid exotic dancers and Guccione’s companion since 1965, was vice-chairman and COO

#35 • Summer 2024 • COMIC BOOK CREATOR

Thor , Hercules

TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. Masters of the Universe TM & © Mattel, Inc. Game Boy TM & © Nintendo of America, Inc.

the drake dossier

The Druckman Cometh!

Celebrating the centennial of writer Arnold Drake's birth with a three-part in-depth interview

Who is Arnold Drake?

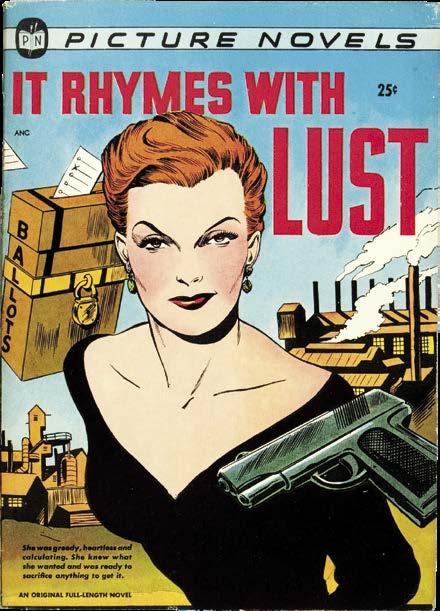

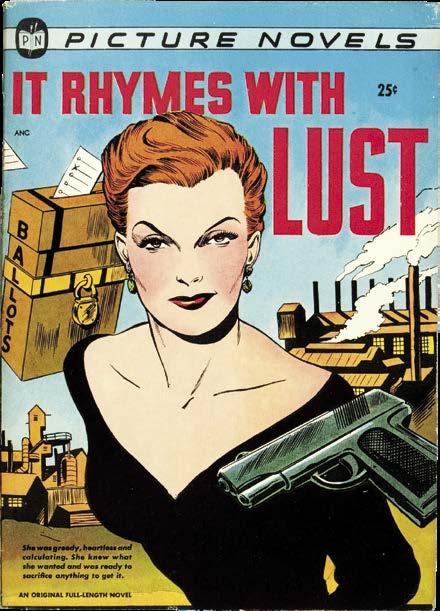

The Manhattan native is the recipient of the very first Bill Finger Award, in 2005, and is renowned as the creator of The Doom Patrol, Deadman, and The Guardians of the Galaxy, as well as co-author of the graphic novel widely considered the first of its kind, It Rhymes with Lust [1950]. Before his passing, Arnold proofed this interview and added some commentary throughout. — JBC.

This page: Below is a portrait of Arnold Drake and his creation, The Doom Patrol by artist Luis Dominguez, commissioned by Marc Svensson. (The scribe is supposed to be holding a typewriter but, well… long story!).

Conducted by JON B. COOKE

[Editor's Note: I've been talking with my pal Marc Svensson, fabled San Diego Comic-Con videographer, for quite some time about doing this project, as my buddy — a dear friend of the late writer Arnold Drake (who died at 83, in 2007) sent me binders filled with Drake-related material over the course of the pandemic and my Massachusetts-based chum volunteered to help present this centenary feature over the next three issues of Comic Book Creator. We both were intent on having all the portions of my 2003 career-spanning interview with the scribe appear during this 100th year since his birth, so here's part one. Marc had interviewed the man at length — check out Alter Ego Vol. 3, #17 [Sept. 2002] for his superb achievement — and he's been an enormous assist throughout, including supplying footnotes for this Q-&-A. So three cheers for Svensson! — Y.E.]

Comic Book Creator: Where are you originally from?

Arnold Drake: Manhattan. Born and bred in New York City. Grew up on the West Side.

CBC: When were you born?

Arnold: March 1, 1924.

CBC: What’s your background, ethnically?

Arnold: Well, my folks were from Romania. They met here, but they were born in Romania. They came here as kids. My dad landed in New Orleans when he was about 16 and got himself a job with the New Orleans Power and Gas, or something; a very early electric generating plant. Since nobody knew anything about electricity, being a greenhorn didn’t cost him anything. By the time he was 17 or 18, he had become an amateur boxer, a semi-pro. He got $5 a fight, and proudly boasted that they never broke his nose.

CBC: Was he a big guy?

Arnold: Not particularly, he was about 5'8". And before he married my mother, he had been quite slim. But the winter before he married her, they were engaged. And he knew that in those days you were judged by the amount of meat on your bones. So he drank cod liver oil all that winter and put on 25 pounds so that he’d look like a proper husband. [laughs]

CBC: Your mom was an immigrant to this country?

Arnold: She came here at about nine- or ten-years-old.

CBC: Did she have a job of her own?

Arnold: I think she started working when she was about ten-years-old, sweeping out stores and that kind of thing. But she went to night school and did a lot of self-education. She wound up speaking five languages pretty well: English, Romanian, German, Yiddish, and French. As I said, with a lot of self-educating. She was something of a writer, herself. When the movie industry started in New York, out on Long Island, she wrote one or two scripts that were made into films. And my brother Milton, some 12 years older than I (and still has all of his marbles), acted in one of those when he was six or eight years old. [Since this was taped, Milton died at 94.— A.D.]

CBC: Do you remember the subject matter or the title or anything?

Arnold: She told me a story that she had worked on. It was about the white slave trade. It was pretty commonplace then, and is not uncommon today. Kidnapping young girls out of their countries, and throwing them into whorehouses. They offered her a contract or some kind of oral agreement, but my dad wouldn’t let her sign it, because the world would think that he couldn’t support his wife. It was a common attitude at that time toward the wife working.

CBC: Did he stick with the electric company?

Arnold: No. He came up to New York and joined his brother Jake (two years older), and they got into the mattress business. They bought a horse and wagon and they sold mattresses from it. And then they began manufacturing mattresses in Brooklyn. From that, they got into furniture, and they became pretty prominent in the wholesale furniture business in New York City.

CBC: What was the name of their company?

Arnold: Well, in the end there were four brothers, and they

#35 • Summer 2024 • COMIC BOOK CREATOR 12

The Doom Patrol TM & © DC Comics. Commission art courtesy of Marc Svensson.

had four independent operations, each named for themselves. My dad was Max Druckman, the original family name. It was an old German name probably going back to the 13th century. (“Ein drucker” means a printer.) At any rate, Dad joined his brother Jacob and they were in business together for many years. And then their brother Ruben and their brother Irving came over, and they put them in the same business. They started what was then called the New York Furniture Exchange, which is now The Design Center, on Lexington and 32nd Street.

CBC: Did he do well?

Arnold: Right up until 1929. Famous story. Lost most of what he had in ’29, but managed to hang on through the Depression.

CBC: Did you have to move?

Arnold: Quite a number of times.

CBC: You were five-years-old?

Arnold: In ‘29, I was five, yeah. We were then living at Riverside Drive and 157th Street, in a magnificent apartment house. Then we moved downtown and were still relatively well-to-do, because, if I recall correctly, Babe Ruth lived in that building. Of course, the Babe was not making the kind of money that ball

players make today, but he was still pretty well off.

CBC: Were you cognizant of the crash at the time?

Arnold: Oh, yeah. I saw them pick up the remains of the father of a friend of mine who had jumped into the courtyard of a big building on 157th Street. That was somewhere around 1931 or ’32. They didn’t all jump in ’29. A lot of them hung in there for a few years and then jumped, when they decided they were worth more dead than alive.

CBC: Were you read to a lot as a child?

Arnold: I don’t recall. I was a pretty early reader, myself. I think my sister may have. I have two brothers and a sister, Milton, Ervin, and Beatrice.

CBC: Were your parents literate?

Arnold: My mom was a big reader. My dad read mostly newspapers. But Mom read fiction and non-fiction, and she was involved with the social movements of the time. She joined

the Henry George movement. I don’t know if you know anything about that.

CBC: No.

Arnold: It was an interesting development in the late ’20s, early ’30s, I guess. It was a single-tax system based on the notion that the only thing that had true value was land, so all the taxes were to be on land and anything built on it. And the Henry George School was founded here in New York City. It was quite prominent during the ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s. While the Marxists believed that labor was the base of all value, the Henry Georgeists thought that land was. Mom believed in it largely because she just knew that there were a lot of bad things going on economically and that we needed some change.

CBC: Did she come from a socially progressive family?

Arnold: Her dad was a self-made man. This guy hadn’t any proper schooling, but again, he was pretty well self-taught. He wound up being a paint contractor in Bucharest and did things like painted government bridges and palaces, and stuff like that, so he did pretty well there. But he decided that the air was freer in this country, so he packed up his family and brought them here.

CBC: So he came here in the 1890s or thereabout?

Arnold: Yeah, roughly.

CBC: Was it you who changed your last name?

Arnold: My brother Milton was the first one to do it. Both of my brothers were and are songwriters, and Milton wrote one of the better-known ditties of our times, “Mairzy Doats.”*

* “Mairzy Doats” was first published in 1943. Milton Drake, Al Hoffman, and Jerry Livingston are credited as composers.

13 C OMIC BOOK CREATOR • Summer 2024 • #35

It Rhymes with Lust TM & © the respective copyright

This page: Above is It Rhymes with Lust [1950], written by Drake and Leslie Waller and drawn by Matt Baker. Below: Drake pen-&ink portrait by Dominguez. Inset left: A very young Arnold Druckman, courtesy of his daughter Pamela.

holder. Young Arnold photo courtesy of Pamela Drake.

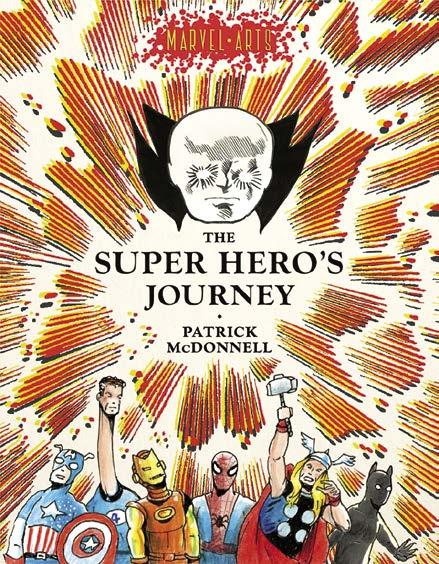

memories of a mutts man

McDonnell’s Marvel Mania

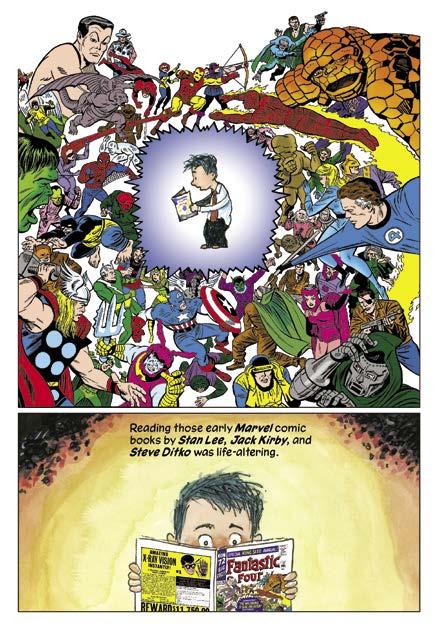

The Mutts cartoonist’s loving tribute to the age of Lee, Kirby, and Ditko super-hero comics

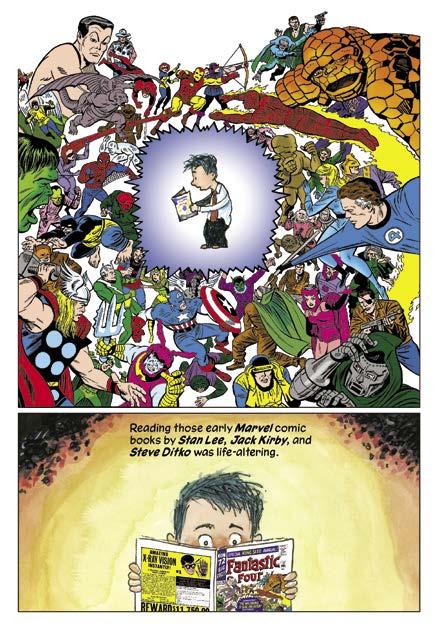

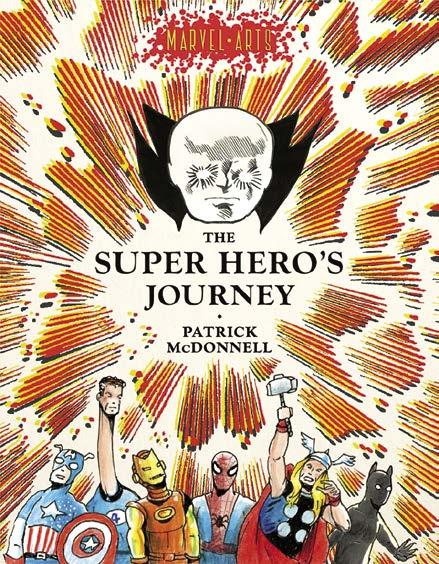

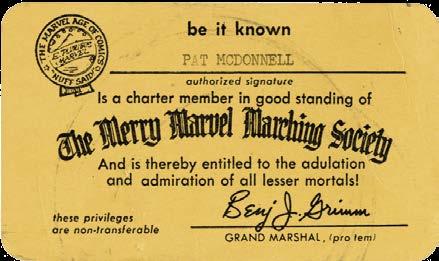

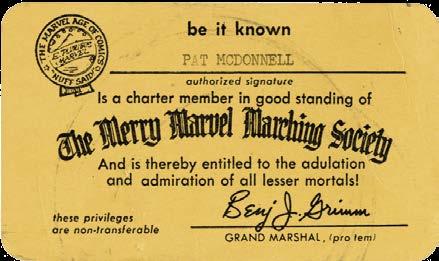

This page: Patrick McDonnell’s celebrated comic strip, Mutts, stars Mooch the cat and Earl the dog, best friends whose antics appear in 700 newspapers (and distributed by email, so sign up at mutts.com!). Inset right is the cover to Patrick’s “love letter” to ’60s Marvel, The Super Hero’s Journey [Abrams ComicArts], a book that incorporates Kirby and Ditko artwork alongside Patrick’s cartooning, as seen in page below. Inset bottom right is proof of his lifelong affection for the comics.

by JON B. COOKE

Don’t tell Bill Griffith or Wayno, but the one comic strip I subscribe to is Patrick McDonnell’s Mutts, which arrives in my email in-box, without fail and to my endless delight, every morning promptly at 6:00. The charm of the newspaper comic strip, warmth of its characters, and quaint, throw-back art style has made it my favorite comic strip since Calvin and Hobbes left the scene in 1995. And I had already encountered the cartoonist’s work eight years before starting his beloved dog-&-cat daily feature, though it was as co-author of Krazy Kat: The Comic Art of George Herriman, a wonderful oversize art book on the arguably greatest of all comic strips, published by Abrams, in 1986.

I was to later learn it was around that same time when Patrick and wife Karen were neighbors of Peter Bagge and his wife, Joanne, in Hoboken, New Jersey. And this was pertinent to me because…? Welp, Pete had been editor of Weirdo magazine between 1984–87 and I was putting together The Book of Weirdo [2019], so I called up Patrick to ask him about neighbor Bagge during that period, and I got to know the man a tad and we got along — well, it’s impossible not to get along with the gent, a truly kind and compassionate fellow. Back during the pandemic, Patrick wrote a piece for CBC #24 [Fall 2020] about his comic-book pastiches in Mutts, so it was natural for me to jump at the chance to focus on his latest endeavor, The Super Hero’s Journey, a memoir of a sort about a boy’s love of Marvel Comics in the 1960s. But there was a problem.

Anything I feature in this mag has to be timed at least six months in advance, but by the time I learned of his 112page love letter to the Marvel Age of Stan, Jack, and Steve, it was September 2023 and the book was about to come out! So, with the help of Abrams ComicArts editor Charlie Kochman, Patrick and I confabbed at Baltimore Con, and he was quite happy to participate in this piece coming a half-year after the book’s release! So two weeks later, I conducted an interview and now you’re caught up, so away we go!

JACK

To begin, we discussed our mutual love for the work of Jack Kirby and, when I shared with Patrick that I had met the man at a Phil Seuling con when I was 13 and pretty speechless, he exclaimed, “I met Kirby at the same place

when I was 13 years old and I didn’t know what to say to him either. I had him sign the first issue of The New Gods and — if you can believe it — a Charlie Chan comic (and I’m probably the only person who has a copy of that signed by Jack Kirby!)”

At the New York Comic Art Convention of 1972, I asked the King to sign Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen #141 (“Don’t Ask! Just Buy It!”) and my favorite super-hero comic book from the House of Ideas, Sgt. Fury #13 [Dec. 1964], which I purchased at the con and it guest-starred (naturally) my fave Marvel character. Patrick could relate to my enthusiasm for that story based in war-torn Europe. “I have two brothers and we all collected comics together and, boy, when that Captain America with Sgt. Fury came out — oh, my God! — that was one of the greatest comics ever for us!” He added with a chuckle, “After that, all we did was play World War II in our backyard.”

Patrick was eight when Kirby drew that issue of Sgt. Fury, but he didn’t necessarily recognize who the artist was behind the work. “I don’t think I knew his name when I was that young, but his comics were always my favorites.”

#35 • Summer 2024 • COMIC BOOK CREATOR Mutts , illustrations of Patrick

Patrick McDonnell. All else TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. 30

McDonnell ©

iconoclastic cartoonist dept.

Tim Hensley’s 275 Panels

The Sir Alfred cartoonist on his whimsical, clever, odd, and funny comic-book lovin’ comics

by JON B. COOKE

by JON B. COOKE

That Tim Hensley, he’s on a pretty unique journey in the comics realm. The cartoonist might have no recognizable style to call his own, at least thus far to readers of his graphic novels, but his ability to (sort-of)* mimic the stylings of other cartoonists is remarkable and it lends an entirely different dimension to his work not exactly easy to describe. While neither sentimental or overly reverent, there’s a profound thoughtfulness he lends to his drawing goofy satires and yet disturbing homages incorporating the approaches of an array of sometimes obscure comics of the ’50s and ’60s. It’s mesmerizing and deliciously appealing, an approach that is partly born of an uncollated(!) collection of random comic books that his dad kept in the garage when Tim was a kid.

“My father was a pretty big comic collector, in the EC fan club in the ’50s,” Tim recently shared. “So there were always comics around. I used to go with him to the comic book store about once a week and buy comics. He mostly bought Marvel and I bought DC at that point.” Also scattered around the house were copies of RAW magazine, Heavy Metal, and the comics in National Lampoon. “My dad had a lot of stuff.”

Those longboxes in the garage, Tim said, “would have comics — not in any real order — that were not organized and not separated by genre. It was just all together and that’s the way I experienced it. It was just like: here it all is!”

“It” would translate into inspiration for most of Tim’s published work to date: three graphic novels, each which took (give or take) the cartoonist five years to complete: Wally Gropius [2010], the “Umpteen Millionaire,” is visually a sort-of/kind-of amalgamation of Richie Rich’s “poor rich kid” premise, the high school tableau of Archie Andrews, adding in a dash of Beetle Bailey, and all resembling a generous slice of John Stanley’s teenager comics. And the story, about a cruel and “flush bobby soxer” on the prowl for a wife (a requirement of Daddy’s will), is told in a linear continuity broken up into often short episodes, including singleand half-pagers (some which quite likely contain comics allusions and tropes I’m just not familiar with). It’s all compiled to resemble a French

* “Sort-of” is a phrase one is compelled to employ frequently when describing Tim’s work!

hardback comics album, à lá Tintin, with endpapers, as well as opening and closing pages, add-ons all cleverly composed. (Tim excels at these seemingly extraneous details, very often “filler” material produced to meet publishing necessities, whether adding pages or conforming to a template. Some of his funniest stuff comes from these additions — for instance, Tim creating a hilarious two-page autobiographical vignette portraying himself as a Frankenstein monster just to fulfill a French publisher’s need to expand a translation of his work.)

Sir Alfred #3 [2015], an oversize sort-of pastiche of The Adventures of Bob Hope as drawn by Owen Fitzgerald, is a litany of anecdotes about film director Alfred Hitchcock, vignettes whether true or apocryphal. Like Gropius, there’s a variety of story formats — full- and half-pagers, faux strips both Sunday and daily, even a double-page splash (of movie set personnel all in agony over a gleeful Hitch spouting atrocious puns). But the content is based on Tim’s revealing, deep research into the iconic filmmaker (and associated folks, from wife Alma Reville on down the production chain), rendered on the page in styles reminiscent of Milt Gross and others, with Hitch drawn throughout to look like a grown-up Tubby from Little Lulu

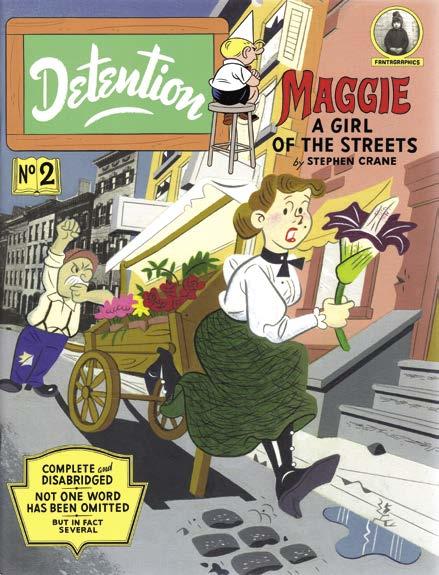

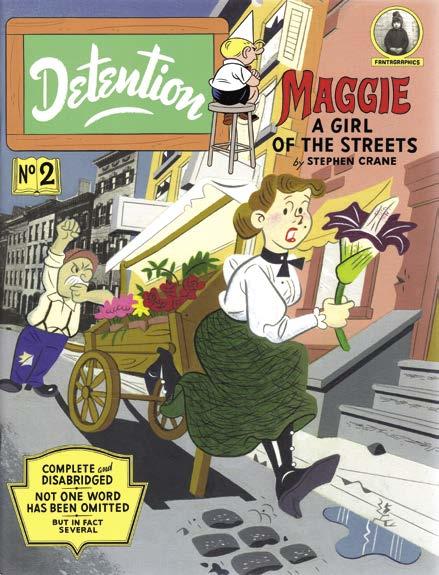

Another oversize production, Detention #2 [2022], is Tim’s latest, and it’s a wild — and yet still faithful — adaptation of Stephen Crane’s 1893 novella, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets,

This page: Above left is panel detail of the title character from Tim Hensley’s first graphic novel, Wally Gropius [2010]. Above is the cover of his latest, “drawn during the Plague Years” (says the indicia), Detention No. 2, a Classics Illustrated pastiche adapting Stephen Crane’s novella, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets. At left is Chris Diaz’s photo of Tim at the 2012 Alternative Press Expo.

#35 • Summer 2024 • COMIC BOOK CREATOR

Wally Gropius, Detention TM & © Tim Hensley.

Photo of Tim Hensley © and courtesy of Chris Anthony Diaz.

34

Portrait by Chris Anthony Diaz

of all trades

Ye Ed talks with horror storyteller Jack Butterworth about his eclectic comics-related careers jack

The Diverse Mr. Butterworth

Above:

first published piece, a one-page requiem for EC Comics, appeared when he was a young teen, in the fanzine, International Youngfan #1, circa 1957. Below: This photo of a 30-something Jack appeared in the Warren Publications “Vampi’s Vault” profile, Vampirella #30 [Jan. 1974]. (See pg. 41.) The pic was taken by Jack’s first wife, Karin Wells, sometime in 1973.

Conducted by JON B. COOKE

[We’ve been meaning to connect for, like, forever since Jack Butterworth introduced himself at San Diego Comic-Con, in 2004. If and when a new edition of The Warren Companion would be in the works, he agreed to talk about his days as a scripter for Creepy and Eerie. And, while Jack was always there in the dark recesses of my noggin, I discovered he was far more than a writer of horror stories (good as he was!). He was among the first to showcase Marvel’s appeal to college students, chronicler of the history of Warren in the ’70s, writer for Steve Bissette’s Taboo, premier comic art expert and comics dealer, Classics Illustrated historian, and even a (sort-of) guest in Tomb of Dracula! — so I just had to interview him for a forthcoming new history of Warren Publications and for CBC! That chat occurred via phone in 2022 and, last December, I visited his Massachusetts digs to meet in person, take some pix, and admire his amazing art collection! Fair warning to everyone that I will not be including here much talk about Warren, as I’m saving that for the book, which will include a stunning amount of memos and related paperwork he saved, plus Jack’s vivid account of the fabled banquet hosted by James Warren that celebrated Rich Corben, Will Eisner, and Archie Goodwin. That’s enough from me… — Ye Ed.]

Comic Book Creator: If you don’t mind, we can just go chronologically. You were born in Boston, Jack?

Jack Butterworth: Yes. I grew up in Belmont, which is a suburb. If I can do a quick resume: 1951, I read my first issue of Tales from the Crypt on a newsstand, flipping through it quickly before somebody yelled, “Hey, kid, this ain’t a library!” And just got totally hooked from the beginning. I became an EC Fan-Addict. The Comics Code came along, comic books got really bland really fast, and I switched to being a science fiction fan in the mid-’50s. And then, in 1961, I got back to comics again because of Marvel. Stan Lee looked at super-heroes and asked himself what I think is the basic question for any writer: “What if this stuff happened to real people in a real world? What would that be like?” And he looked at super-heroes that way and it was revolutionary.

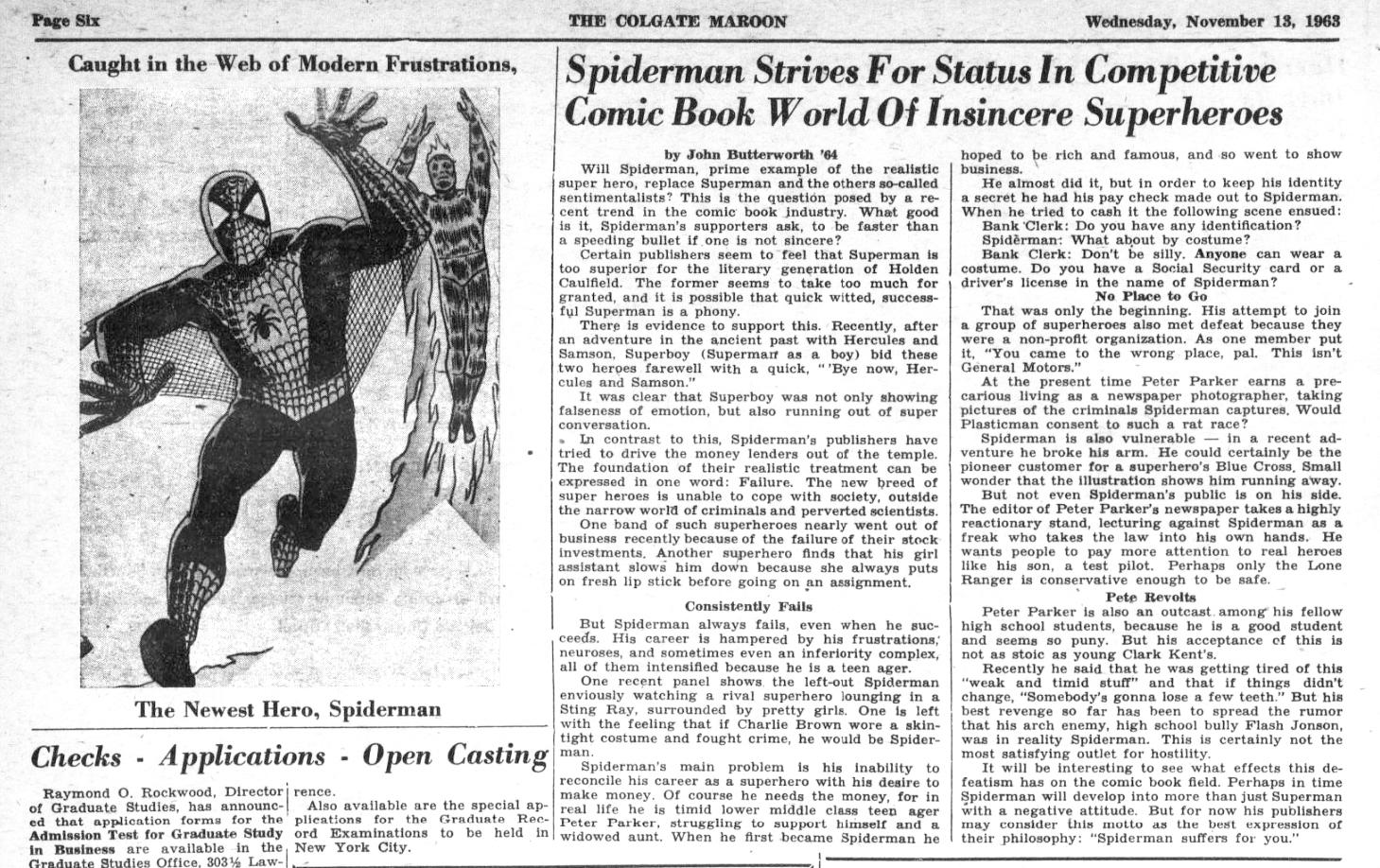

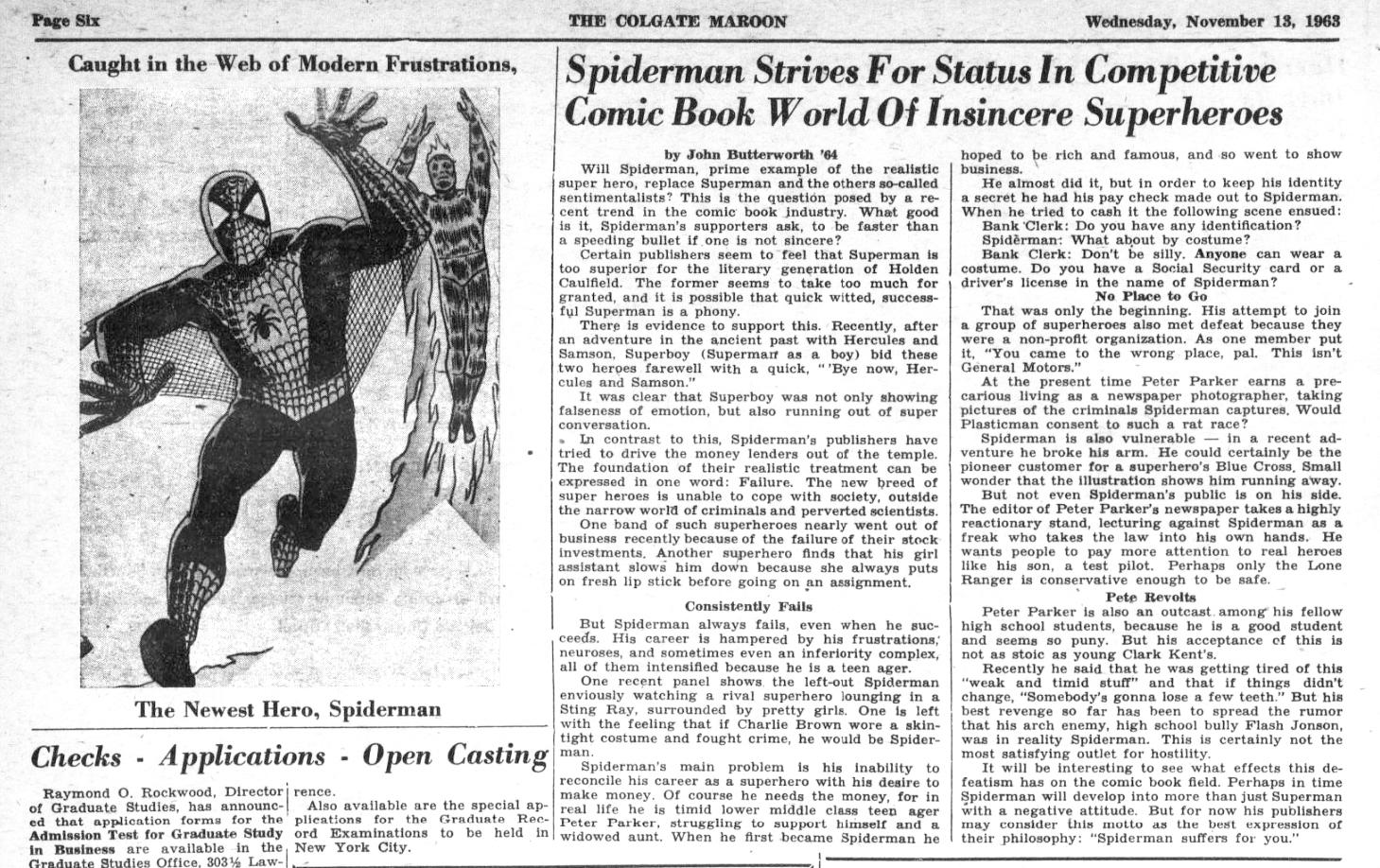

In 1963, I was a total Marvel fan. I wrote an article for my college newspaper, The

Colgate Maroon, about Superman and Spider-Man, comparing them, and saying that it looked like Superboy might be running out of super-conversation. And then, to describe Spider-Man, I came up with the line, “If Charlie Brown wore a skin-tight costume and fought crime, he would be Spider-Man.” And I thought, you know, that’s a pretty good description. Well, it turned out, first of all, they quoted it in an article in the New York Herald Tribune Sunday magazine that was devoted to comics, with an eight-page “Spirit” story by Will Eisner about the Spirit becoming involved with the 1966 mayoral election.

CBC: Can we just back up a bit? Were you an only child?

Jack: I was. Having not much in the way of other kids in the house, usually I had a lot of free time.

CBC: Did your parents read?

Jack: Not that much. I remember my father looking at a list of stuff I wanted for Christmas and he said, “This is all books.” He read paperback Western novels when he had to take a plane somewhere. They were fairly short and fairly simple, and weren’t that challenging, as far as plot twists.

CBC: What was his job?

Jack: He was a shoe salesman.

CBC: Did he serve in World War II?

Jack: No. He was looking into getting into one of the branches of the service toward the end, but he never did. I was born November 12, 1941. I was his draft deferment.

CBC: Did your mom have any creative bent?

Jack: My mother tried painting for a while in the 1950s. Basically, she went to a painting class and painted copies of greeting card artwork, landscapes… And I still have all of those paintings. My wife, Lyssa Andersson, really had a wonderful relationship with my mother. She loved the paintings. They stayed with us.

CBC: So did you show a predilection to write as a youngster?

Jack: Yes, I did. The first story that really impressed me, although I was an EC fan — their stuff was really adult and it was beyond my ability to comprehend — I found myself entranced by Stan Lee’s stories in the Atlas horror comics, and there was this one story, in Strange Tales [#20, July 1953] called “Wilbur.” It’s a story about this guy who’s trying to inherit his uncle’s wealth. His uncle has come back from Africa and has left everything to someone named Wilbur. The nephew doesn’t know who this is, but he will inherit everything if Wilbur dies. The guy has a knife and goes downstairs in the basement in the dark, looking for Wilbur. Then there are screams and we can’t see what’s going on, but the last panel reveals that Wilbur is a lion and the guy’s been eaten. And this really impressed me as something I could maybe recreate. So I did a story about a kid that had a pet lion named Wilbur. A friend did four or five illustrations. We were in fifth or sixth grade. That was my first attempt at a short story.

CBC: A total swipe!

Jack: Absolutely. We call it “un hommage.” You know, if you say it in French, it sounds so much nicer… Oh, that sentence about “Charlie Brown fighting crime,” that wound up on the back cover of the first Spider-Man story collection, published as

38 #35 • Summer 2024 • COMIC BOOK CREATOR

Jack Butterworth’s

Photo by Karin Wells and appears courtesy of Jack Butterworth.

a paperback by Lancer [Spider-Man Collector’s Album, 1966]. I saw this paperback on the rack. “Oh, great Spider-Man stories! I want this.” And then I looked at the back cover and there was my line! It was attributed to The Colgate Maroon because everybody had heard of Colgate, and certainly nobody had ever heard of John Butterworth. But that was really amazing, very encouraging, when I saw that.

CBC: That article has got to be one of the earliest mentions outside fanzines of the Marvel super-heroes. Certainly of Spider-Man. This was even before the assassination of JFK.

Jack: Yes. And it was in mass media, in the Herald Tribune. I met Eisner later on and we were laughing about having been in that same issue, because the Herald Tribune folded within a year of that appearance. And Eisner said, “Well, we killed the Herald Tribune, didn’t we?”

CBC: Yeah. And you had a letter in the letter column in the earliest issue of Amazing Spider-Man that I own, #15 [Aug. ’64].

Jack: Right, the first appearance of Kraven the Hunter. I have to write to Colgate, to their alumni magazine, at some point and say that we were the first college to try to recruit Peter Parker, also known as Spider-Man, or at least suggested…

CBC: Did you write in school? When you wrote that short story, “Wilbur,” how old were you?

Jack: I was in fifth grade, so 11, probably.

CBC: Did you continue writing? Did your teachers encourage…

Jack: They liked it. I wrote a tall tale that was about six paragraphs that was published in the local weekly newspaper, something that we did for a library book club group. I was listening to Suspense radio shows and watching the Alfred Hitchcock Presents program and seeing how the stories were constructed. What really surprised and scared me in a TV story was “The Gentleman from America” episode on Alfred Hitchcock

Presents, one of the first things I found that really was scary as far as a ghost story. I realized that basically what scared me was not necessarily a twist ending, the way EC twist endings would shock me, but a “twist middle,” where this twist was in the middle of the story, and then you’re trying to figure out what’s going to happen next. That kind of thing.

CBC: Did you consider writing for a living at all?

Jack: I thought, “Gee, I really like telling stories. I want to try to be a writer.” But my parents, of course, responded the way middle-class parents would. They said, “Well, that’s wonderful, dear, and maybe you could teach.” Have a day job, basically, is what they were concerned about. They were afraid of having me living in their basement in my 20s trying to sell stories.

CBC: Did you collect ECs when you first picked one up?

Jack: Well, no. The “new trend” ECs published after the Comics Code took hold, I bought some of those — Impact, Valor, and Psychoanalysis, of course, which was totally mind-bending and people are still talking about that title. They actually did a comic book about

seeing a psychiatrist… Wow!

39 C OMIC BOOK CREATOR • Summer 2024 • #35

people

&

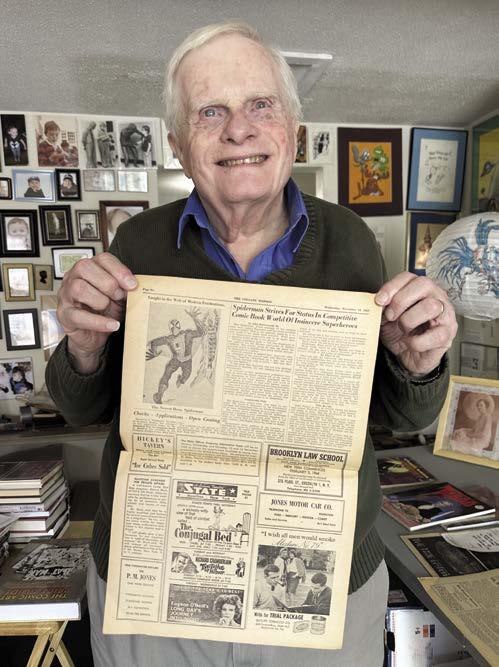

Above: Clipping from the college paper by Jack, The Colgate Maroon, from November 13, 1963, a very early article about the burgeoning Marvel Age. Below: Jack poses with the paper during Ye Ed.’s December 2023 visit.

Spider-Man, Human Torch TM

© Marvel Characters, Inc.

DENNY O’NEIL Saving the World, One Story at a Time

#35 • Summer 2024 • COMIC BOOK CREATOR 54

Dennis O’Neil portrait © Ken Meyer, Jr.

FROM THE EDITOR: In the spirit of Comic Book Creator’s increased focus on writers as of late, plans were set in motion last summer to devote an issue to Bob Brodsky’s favorite scribe, Dennis Joseph O’Neil [1939–2020], one of the finest talents in the history of American comics. Bob, whose fanzine from 1999–2004, The O’Neil Observer, was mostly devoted

Denny O’Neil was comics’ first truly great modern writer.

The scribe was passionate about his work, erudite, and articulate, and his best stories employed a journalist’s feel for telling tales in ways that enlighten as well as entertain.

And while the field’s best scribes, including superb creators Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Garth Ennis, have perhaps crafted stories and concepts beyond Denny’s scope, none of their work would have happened without his groundbreaking influence.

In popular music, Bob Dylan’s songs bequeathed a new way of songwriting, breaking free from, the “moon and June” rules of the craft skillfully practiced by classic Tin Pan Alley contributors to the “Great American Songbook,” like Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, and George and Ira Gershwin.

While Dylan’s work, beginning in the early 1960s, was very different from that of great songwriters to come, e.g., Pete Townshend, Nick Cave, and Tom Waits, it was Dylan who kicked down the walls, and bushwacked the conventions, of what popular song could express and convey.

Dylan gave songwriters the freedom to follow their own creative path. Townshend’s songs are nothing like Dylan’s, but he needed Bob for permission, if you will, to write them.

The Dylan analogy works for Denny O’Neil and the great comic book writers to follow.

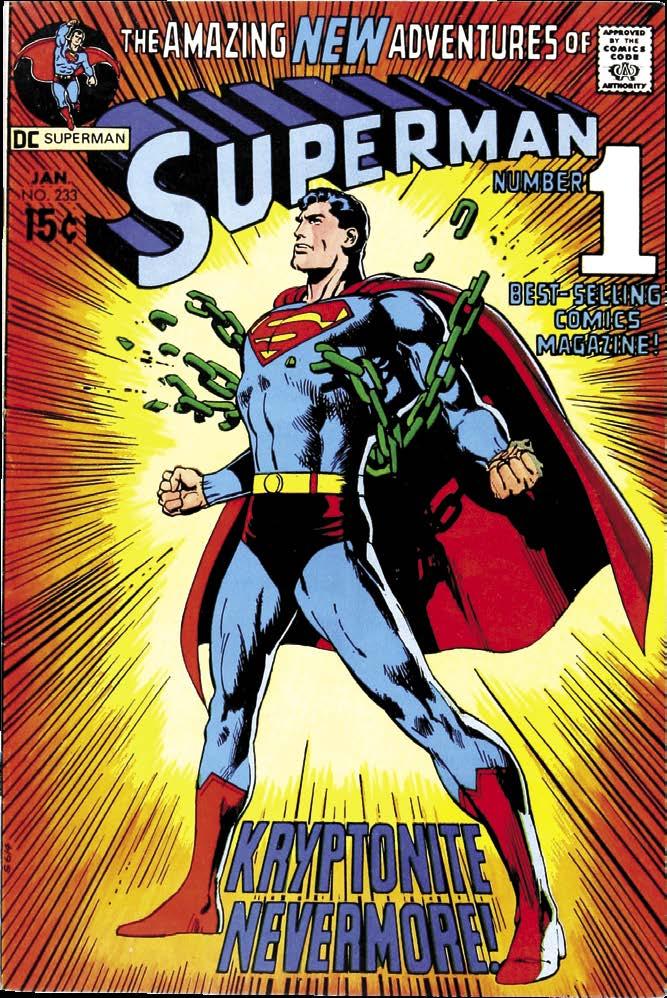

“Kryptonite Nevermore,” indeed.

to the Missouri-born wordsmith, toiled on this issue’s main feature into the new year, but he became sidelined before it was due. Thus yours truly has promptly jumped in to complete the section, doing my best to retain Bob’s rightfully — and righteously! — biased opinion regarding his idol’s abilities. So offer all bouquets to B.B. and save any brickbats for — YE ED.

In an industry where the artists tend to get more recognition, Denny’s best work stands as testament to the power of great comic book writing. He broadened and deepened the parameters of what a good comic book could be.

Denny’s work at DC of that period — especially on the sagas of Batman, Wonder Woman, Superman, and Green Lantern/Green Arrow — elevated comics to new, unprecedented levels of creativity, and gave his readers (with and without oft-creative partner Neal Adams’ superb artwork) some of the greatest stories in the history of comics.

Denny was the adult in the room, the professional who broke the rules, replaced them with something better, and elevated comic book writing to a more creative and expressive place. During his peak creative years of roughly 1968–73, his work influenced, awed, and inspired both his contemporaries and the creators to come.

Denny’s best work was intelligent and well-crafted, with a tight narrative, and rich dialogue, and characterization. There is also a nth element that’s harder to pin down — an elegance, really, in the way the man writes a story.

Denny’s best work taught and inspired not only Moore, Gaiman, and Ellis, but also the great young writers immediately following him in the early 1970s, such as Steve Englehart, Don McGregor, and Steve Gerber.

To this day, the astonishing early 1970s work of Denny and Jack Kirby’s Fourth World stand as the twin pillars of the DC Universe (Multiverse?).

While Kirby was surely comics’ most exciting, important, and influential artist, O’Neil’s work, primarily at DC during the “relevance years’” from roughly 1967 to 1973, continues to influence, impress, and inspire new generations.

One goal here is to revisit those amazing late ’60s/early ’70s years when Denny’s characters and stories often meshed with the times in which they were created. Whenever possible, you will hear Denny in his own voice.

Walk into any comic-book store today, and you will see evidence of O’Neil’s importance on the “new this week” racks. Though often mutated beyond original conception, Denny’s characters and concepts continue to entertain and engage 21st Century comic book fans.

by Bob Brodsky with Jon B. Cooke Portrait by Ken Meyer, Jr.

55 C OMIC BOOK CREATOR • Summer 2024 • #35

Justice League of America TM & © DC

Comics.

Without Denny, there would be no return to Batman’s dark avenger roots, no Green Lantern/Green Arrow, Ra’s al Ghul, Talia, Damon Wayne, Lady Shiva, Richard Dragon, “New” Wonder Woman, homicidal Joker, Leslie Hopkins, Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, Santa Prisca, Crime Alley, or Lazarus Planet, not to mention “Matches” Malone!

At his peak, Denny’s skill as a writer was unsurpassed in the field. His gift for characterization and ability to make his characters real was beyond that of most of his contemporaries, except perhaps Stan Lee. Denny took characters drawn flat on a page and stuffed them with humanity. His captions were elegant Haiku, his dialogue could be as dramatic or conversational as needed. Denny’s best work stretched the boundaries of what a comic book story could express and convey.

This quiet and private man turned bland, perennial second banana Green Arrow into a fiery orator for social justice, while bringing Batman’s conflicted and tragedy-induced personality to prominence.

Denny’s best stories were always ambitious. With the eye of the journalist and the skill of a novelist, his stories and characters were truly “real” in ways rarely portrayed in comic books.

His passing on July 11, 2020, followed by the death of his most important collaborator, Neal Adams, in the spring of 2022, was an unfathomable loss for comics and popular culture while remaining stark reminders of their impact on generations of readers.

Denny was a master craftsman. His finest work stands with the greatest writers from any medium. His stories had grace, elegance, and, yes, beauty. Always a true professional, Denny approached comic book writing from an “outside looking in” perception.

Unlike the next generation of great comic book writers like Englehart, who worked from an “inside looking out” vantagepoint, Denny kept a professional distance from his work. If Denny was Bob Dylan, then Steve was Neil Young. Englehart could tell you who inked one of his stories back in 1973, while Denny maintained a different perspective on his work.

Partly F. Scott Fitzgerald, with a dash of Chandler and a touch of Tom Wolfe, Denny was all about respect for both his characters and his readers. He was a professional writer, who met his deadlines, understood his obligation to his readers and editors, and created amazing work within those confines.

AN AGE OF RELEVANCE

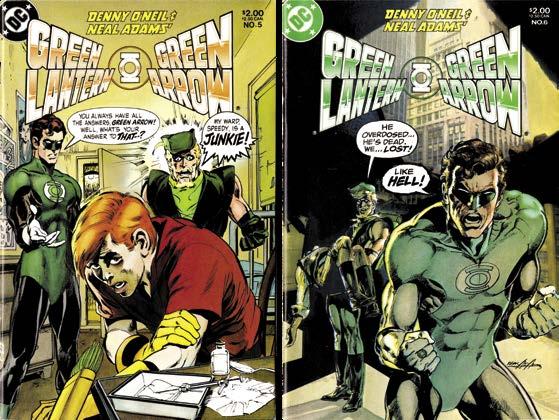

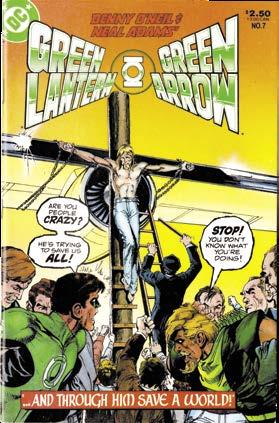

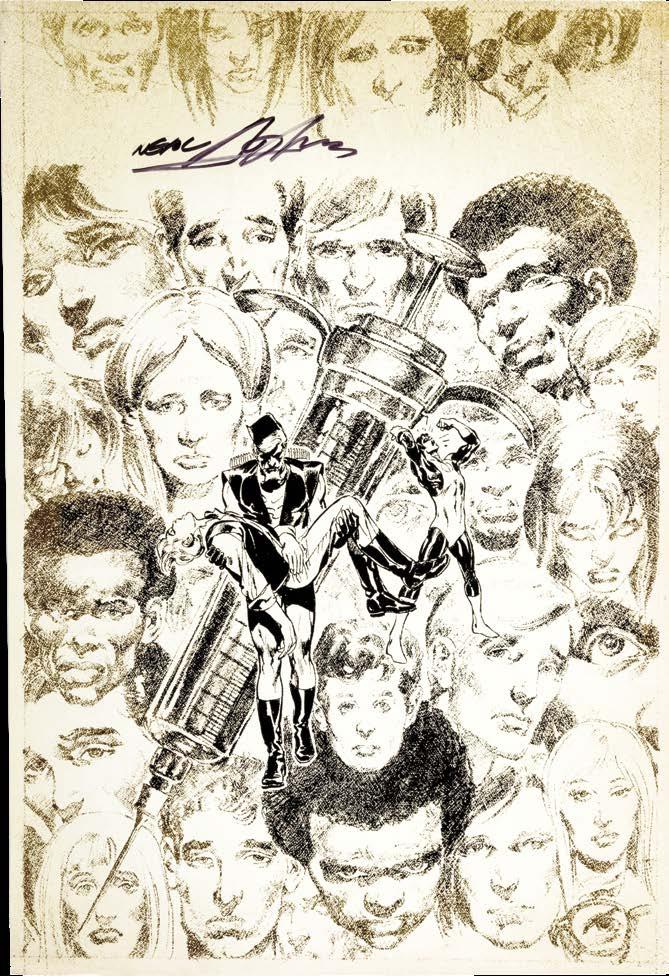

Denny O’Neil was, if you will, the Stan Lee of DC Comics and, while his creations were canonical, his recreations were even more important, whether the “New” Wonder Woman, his “Sandman series” in Superman, the return of The Batman, reappearance of The Joker as an insane killer, and, of course, his and Neal Adams’ magnificent Green Lantern/Green Arrow run of the early 1970s, which ushered in a new epoch.

Beginning in the late 1960s, Denny reconstructed decadesold characters and made them real. In the scribe’s work, his “universe” continues to be a pivot-point for today’s comic book creators.

Like Dylan going electric, Denny stood at the center of a firestorm that elevated an oft-ridiculed medium to a place where even The New York Times and Newsweek paid attention. In fact, decades later, the Times’ respective obituaries for Denny and Neal were detailed and reverential, acknowledging their contribution to popular culture beyond comics.

Tagged to their time, DC’s and (to a lesser extent) Marvel’s “relevant” stories of the late ’60s and early ’70s became a genre onto itself. Of course, like all genres, the good and bad co-existed, as lesser creative hands took their shot at the trend. “Relevance” turned out to be also a fad of sorts, with quality ranging from the sublime to the not-so-hot, with most “relevant” comics falling in between. (In truth, while Denny and Neal were the main conveyors of the best of the relevance era, other creators, and creations, played a role in the movement’s development, success, and failure, and they deserve our recognition, as well.)

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, I had the privilege of editing The O’Neil Observer,* a fanzine “dedicated to the storytelling of Denny O’Neil and the craft of comic book writing.”

This article incorporates material from The O’Neil Observer’s five issue run [1998–2004], as well as a feature piece on Denny by Kevin Hanley and myself that was published in Comic Book Marketplace #56 [Feb. 1998]. Except when noted, all interviews were conducted by me (and a few by Ye Ed.) and, whenever possible, you will hear Denny in his own voice.

In addition are a few excerpts from a 1970 group interview with Denny taped by then 15-year-old fan Walt Jaschek. Walt was a member of the Graphic Fantasy Society of St. Louis (“GARFAN”), a comic book club located in Denny’s hometown.

#35 • Summer 2024 • COMIC BOOK CREATOR

* Affectionately abbreviated by fans as O’NO. — Y.E.

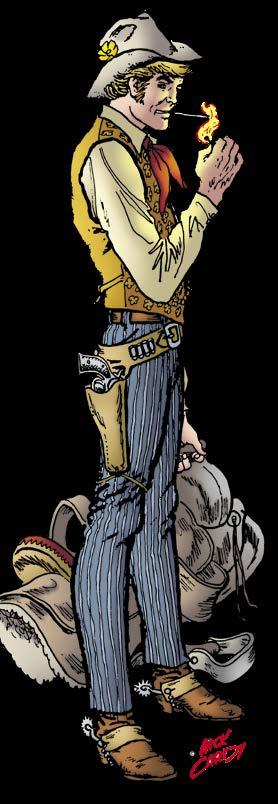

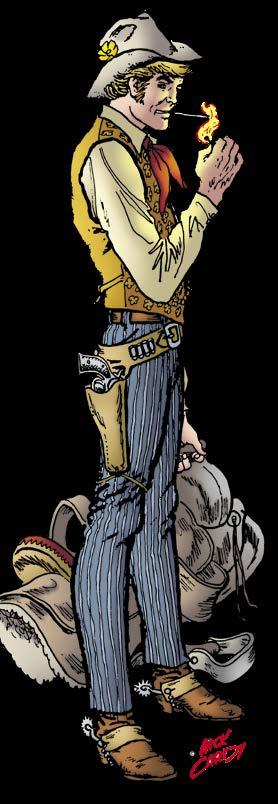

Wonder Woman, Bat Lash TM & © DC Comics. Bat Lash colors by Glenn Whitmore.

The writer, then somewhat new to comics, chatted with club members regarding his work at DC, and other related topics. At that time, Denny was on a creative high and his discussion with the club shows his insights, wit, and honesty.*

On a personal note, getting to know a writer whose work meant so much to me since childhood and discovering what great people he and his second wife, Marifran, who passed away in 2017, are among the great joys of my life.

“Relevance,” in relation to comics anyway, meant more than covering the super-charged issues of the late ’60s and early ’70s in graphic form, no matter how dramatic or important. Like all genres, relevance was a genre unto itself, as mentioned, and quality varied from book to book and story to story.

In many ways, as the newspaper headlines that fueled it faded from collective memory, relevance proved to be a fad, with quality ranging from the sublime to the mundane — Hal and Ollie: meet Brother Power, the Geek.

I suppose the closest comparison in Top 40 music was the “Great Pop Protest Craze of 1965.” For every great song like the Byrds’ #1 hit version of Pete Seeger’s adaptation of Ecclesiastes 3:1–8 “Turn, Turn, Turn,” there were 10 cheap knockoffs like Barry McGuire’s so bad, it’s good, “Eve of Destruction.”

Denny’s work during the relevant years fused his liberal beliefs and Catholic Worker background with his experience as a writer, combining his talent for fiction, including characterization, dialogue, and plotting, with the skills of a journalist, especially his excellent diction and eye for detail. And his finest stories could also be quite cinematic. Like his peer, the great writer/editor, Archie Goodwin, he often drew thumbnail sketches on his scripts for the artist to follow. Though not an artist, Denny always remembered that comics were a visual medium.

THE GOOD CATHOLIC BOY

Denny grew up “a good Catholic kid” in St. Louis, Missouri. “As a kid I was a devoted comic book reader,” Denny told me during our first interview for CBM, in 1997. “A little ritual after Sunday Mass: my father would stop at the local store and he would get milk and eggs, and what we needed for breakfast, and he would usually buy me a comic book. Later, my grandfather did something similar, so I was a stone fan before there were such things.

“I have very pleasant memories of being sprawled out on the front porch reading comics on a summer afternoon. I just loved the stuff. I didn’t know I loved it, but looking back I can see I was a stone comics lover. I remember Batman and Superman, but I also remember loving the Vigilante and Green Arrow. But then, as I went into high school, there were a lot of other things to claim my attention.

“Also, I now know that comics just weren’t around to be bought anymore. The little stores, like the one that my father and I stopped at, went out of business after the end of the war. The stores that survived found that, if they used their space for paperback books instead of comic books, they would make a lot more money per sale.”

(In a Comics Journal talk with fellow writer Matt Fraction, Denny said his was, “Not a terrible childhood — nobody beat me — but the nun did lock me in the convent basement every night in eighth grade. It was not a great environment for someone

* The full conversation between Denny and the members of GARFAN, along with a copy of Denny’s script for the book-length Green Lantern adventure “This is the Way the World Ends,” #63 [Sept. 1968], and more, are collected in his one-of-a-kind book, The Denny O’Neil Tapes [WALTNOW Studios, 2023]. The book is available in hard copy as well as PDF at amazon.com. It comes highly recommended. — B.B.

with my limitations and someone with my proclivities and, dare I use the word, talent. The arts were not encouraged, even less so when I went to a Christian military high school — talk about bad casting!”)

Denny graduated from St. Louis University, in 1961, with an English literature major and minors in creative writing and philosophy. He served two years in the U.S. Navy, getting “some practical handson journalistic experience, and a lot of experience mopping floors.” He also participated in the blockade of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis, in October, 1962.

“I came out of the Navy, taught school for a year and decided that I wanted to write in some way.” Denny answered

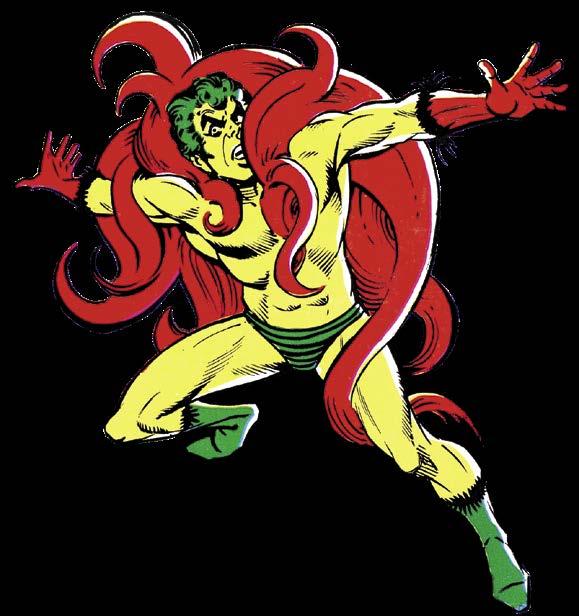

Superman , The Creeper TM & © DC Comics. 57 C OMIC BOOK CREATOR • Summer 2024 • #35

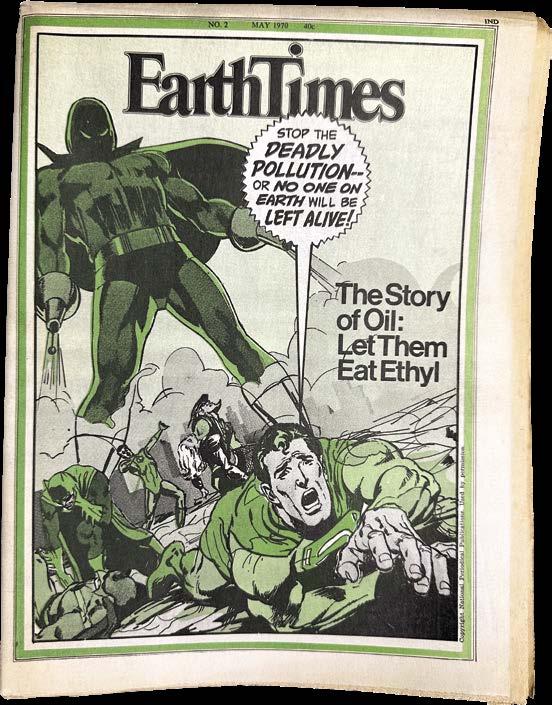

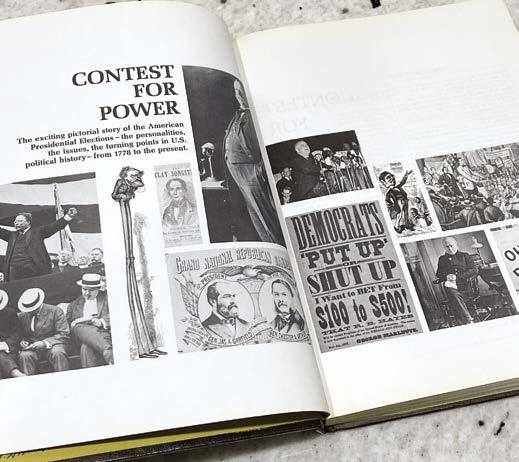

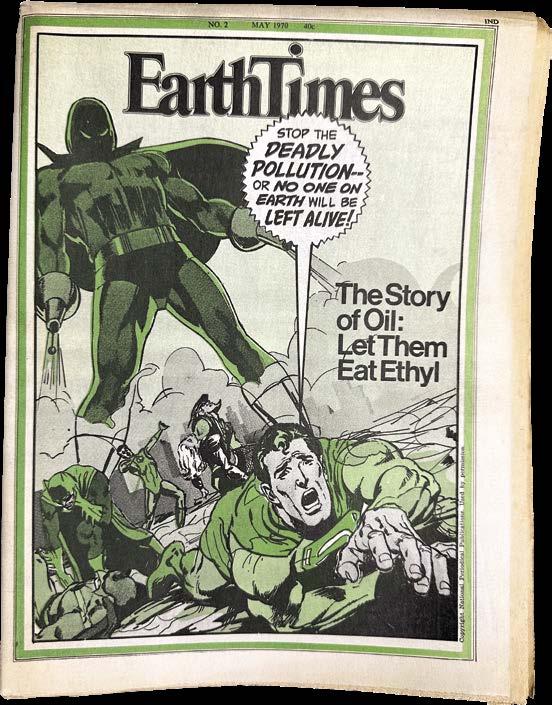

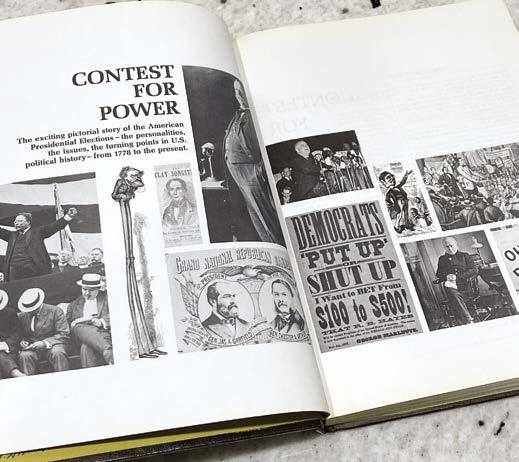

Page 55: Cover art of Justice League of America #79 [Mar. ’70] graces the cover of Earth Times #2 [May ’70], a San Francisco-based ecology tabloid monthly. Previous spread: Covers of Wonder Woman #178 [Oct. ’68] and Superman #233 [Jan. ’71], and Bat Lash illo by Nick Cardy and Beware the Creeper #2 [Aug. ’68] cover detail. Inset right: Marvel writer’s test sheet, an unlettered page, Fantastic Four Annual #2 [Oct. ’64]. Opposite page: Denny’s first article on comics, Southeast Missourian, May 17, 1965. Below: Contest for Power [’68] spread, an assignment that got Denny through 1967.

an ad for a beat reporter from a newspaper in Cape Girardeau, a Mississippi River port town located near St. Louis. As a smalltown journalist, he would, according to a colleague at The Southeast Missourian, participate in story ideas, sometimes outof-this-world story ideas — including covering the “Buck Nelson Flying Saucer Convention” out in the wilds of the Ozarks — and sometimes hip (for 1965) ideas, such as having a photographer gauge a teen audience’s reaction while watching the Beatles’ movie, Help! Or so remembered fellow Missourian reporter Ken Steinhoff, who called Denny, “One of the most talented writers I ever worked with,” and who replaced him as “district news editor” when Denny left town in a hurry. What prompted that sudden departure was the result of the ambitious scribe making a connection that altered the trajectory of his career.

“As a reporter,” Denny said, ”I was on the road a lot — spending time in bus stations and drug stores — and I noticed comics were back. I suddenly realized that I hadn’t seen these things in about 10 years, so I bought some and found I really enjoyed them. I then did some rudimentary reporting and found that comics were, in fact, in the middle of a renaissance. I did two articles on the return of comic books, and then Roy Thomas got in touch with me — his parents subscribed to the paper.” This was all happening in May of 1965.

Thomas, then an English teacher at Fox High School outside of St. Louis, had already accepted an offer to go to New York and join the professional comics realm to become editor Mort Weisinger’s assistant on the Superman line of comic books.

“So I did a third article, [this one] on Roy. I went over to his apartment on a Sunday afternoon and bored my girlfriend silly as I sat and talked with Roy. I was really turned on by the conversation and the chance to write the piece.

“About a month later, I got a call from Roy asking if I would be interested

in the Marvel writer’s test. He had moved to New York, worked with Mort for about two weeks, and then took a job with Stan Lee.

“I got this test and ‘why not?’ — it was four pages of Fantastic Four without copy and it seemed like an amusing thing to do for 20 minutes. So I did it, sent it to Roy, and, about a week after that, a whole lot of things happened in one afternoon, the culmination of which was that I accepted an offer to come to New York and be Stan Lee’s second assistant.”

Anything seemed possible in 1965 and now, in his mid20s, married and father of a young son, Denny moved his new family to the center of comic book publishing, New York City, and joined the Marvel Bullpen.

THE HOUSE OF STAN

“It was mostly too goofy a thing not to do. I thought I’ll certainly give this a year, I’ll get some stories to tell and then I’ll probably come back to what I considered to be my real profession, which was small town journalism. I somehow never got back to that paper.”

Replacing fellow writer Steve Skeates (who, by his own admission, was let go due to poor proofreading skills), O’Neil worked as a Marvel staffer for about six months before giving up a steady check for the star-crossed life of freelance writer. One of his major projects during those early years in New York

occurred well outside comics.

“I wrote a book on presidential elections that first couple of years. It was a coffee table book called Contest For Power [Year, Inc., 1968], and I’m sure it’s totally unavailable now. It was not a bad project and it got my wife, infant child, and me through a summer that would have been virtually penniless without it.” (Alas, Denny was correct as I’ve not been able to find a single copy of his book.) [But Ye Ed did! See pic at left. — Y.E.]

During his first stint at Marvel in 1965 and ’66 — he would return in the early 1980s as an important senior writer/editor — Denny wrote assorted humor and Western stories, including Two-Gun Kid, Millie the Model, and five or so issues of the “Doctor Strange” strip, in Strange Tales

“My assignment on ‘Doc Strange’ came about because

58 #35 • Summer 2024 • COMIC BOOK CREATOR

Above: Discovered at onetime Southeast Missourian photographer Ken Steinhoff’s website devoted to Cape Girardeau, a photo of Denny O’Neil and fellow staffers at a co-worker’s apartment.

Photo by and © Ken Steinhoff. All Rights Reserved. Used with Permission. Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc.

Marvel was in the process of exploding and Stan, who had written everything, could not keep up with it all. Roy was already kind of full up, so neither of them, for whatever reason, wanted to do ‘Doc Strange,’ and I was the other warm body in the office.

“My job was simple, I had to imitate Stan Lee. Success was judged by how indistinguishable my work was from his and I do not have one word of complaint about that now. Lee’s style was unique, and it was what was making Marvel happen.

“I think every young writer starting out with a new craft must imitate somebody — whether consciously or unconsciously. Well, for me, it was all nicely spelled out: ‘Imitate Stan Lee.’

“Which I did and, of course, there were things I might have done differently… but I’m very grateful for the fact that, those first six months, I knew what I was supposed to do and, if I did it with reasonable competence, I was successful. That’s a much bigger break than most writers get starting out.”

Stan Lee aside, O’Neil’s brief “Doctor Strange” run, in Strange Tales [#145–149, June–October 1966] holds up well on its own. Reading them today, one can sense a new talent feeling his way. Still, we’d have to wait a few more months for Denny to write a more traditional super-hero title.

Ironically, Denny’s most important story during his first tenure at Marvel is not well-remembered today: Daredevil #18 [July 1966], “There Shall Come a Gladiator.” Denny completed the last 13 pages of the story for a vacation ing Stan Lee — talk about putting on the pressure!

Penciled by the late, great John Romita, Sr., and inked by Frank Giacoia, Denny seamlessly completes a sequence started by Stan, featuring Daredevil hitching a ride on a helicopter by hanging on a rope from the outside, tailing Foggy Nelson and Karen Page, who are passengers in a New York taxicab.

The issue also marks the debut of the Gladiator, a frustrated tailor (we don’t even get to learn his name), who makes copies of super-hero and super-villain costumes for the masses. He’s mad-angry at the world, and especially the costumed crowd, for getting the glory that should be his and… well, you know the rest. Actually, the Gladiator is close to being Marvel’s

59 C OMIC BOOK CREATOR • Summer 2024 • #35

SOCIAL JUSTICE LEAGUERS

A glimmer of the socially relevant comics to come could be found in Denny’s JLA run [#66–83, Nov. ’68–Sept. ’70], along with Wonder Woman, his first regular assignment, if mostly because of characterization he instilled into team members and specific developments made to some heroes’ lives. In his first year as scripter, Wonder Woman quits, Black Canary joins, Snapper Carr turns traitor, they get a new, off-planet headquarters, and the absence of J’onn J’onzz, the Martian Manhunter, is resolved. But these changes are minor in comparison to the historic revision of Green Arrow in JLA #75 [Nov. ’69].

Some readers felt that previous JLA writer Gardner Fox’s stories had become formulaic, making the title less relevant by late ’60s standards. Further, many wanted more characterization… while Gardner put more emphasis on story and plot. “I don’t think I was ever aware that I wanted to shake things up for the sake of shaking them up,” Denny said. “Certain things about the series weren’t working for me, didn’t make sense to me.” Under Julie’s assured guidance, Denny’s JLA work was beginning to show flashes of future brilliance. Part-satire, part-social commentary, he seemed to be having fun, while

adding depth to staid characters like Arrow and Manhunter. Did handling so many diverse heroes pose a problem for the writer? “It was very difficult — especially since there were some arbitrary rules. A certain percentage of them had to be on stage in every issue, and you were supposed to at least try to give them all equal time in the spotlight. It was impossible to do, but you were aware that was what you were supposed to do,” Denny remembered. “The main problem though is, Jesus, you’ve got three versions of God — Flash, Green Lantern, and Superman at one end of the spectrum , and then you’ve got the Atom, who can make himself real little, and Batman who’s real smart, at the other end. So how do you come up with an antagonist that answers the needs of all of those diverse characters?”

By early 1970, Denny had expanded the stakes and given a preview of his work about to debut in another title edited by Julie, with a two-part story that pitted the super-team against aliens bent on destruction of the Earth’s environment [#78–79, Feb.–Mar. ’70]. The tale concluded with the scribe’s somber reminder that, though the JLA may have saved the Earth this time, even they could not protect the planet from any fate resulting from mankind’s continuous polluting ways.

Ironically, the greatest legacy of O’Neil‘s work on an ensemble of characters that included headliner heroes, Superman and Batman, was his remaking of the motivation and personality of a previously third-rate persona, Green Arrow. Neal’s visual remake of the archer into a goatee’d, modern-day Robin Hood occurred two months earlier, in a Bob Haney-authored Batman team-up, in The Brave and the Bold [#85 Sept. ’69]. With JLA #75 [Nov. ’69], it was Denny who stripped Arrow alter ego Oliver Queen of his wealth and thrust him out into the “real world.” Suddenly, this perpetually minor character was replaced by a passionate man who spoke out in the tenor of his time. (Notably, it was also Denny who introduced the Black Canary into modern DC continuity and… umm… made her an actual widow and thus available for Ollie’s amorous advances.)

In the end, Denny told Michael Eury, “[JLA] was one of the few assignments that I walked out of. I’ve been fired off of any number of them, but that and Superman, I walked away from. Real hubris for someone who was as new at the game as I was, just because of the technical difficulties writing it.”

GREEN DAYS

When Michael Eury suggested to Denny that he imbued godlike JLA members with human characteristics, he replied, “I think I probably imported that from my year/year-and-a-half of working with Stan. Sometimes his plots were fairly rudimentary, but people talked differently and they had interpersonal conflicts. Stan Lee taught us that characterization can be more important than plot; his first, I think, huge contribution.”

With all due respect to Stan’s “hero with hang-ups” motif, while assuredly a master of characterization, Denny added a new dimension to the super-hero comic book. Call it “realism,” or “relevance,” his characters thrived against a consistent backdrop that made sense. The authentic context he created would include people, places, motivations, dialogue, and conflict. Be it “Square” John Stewart, Ollie Queen, or Diana Prince, his best characters began to operate within a consistent set of rules. And nowhere is there a better example than in his and Neal’s Green Lantern/Green Arrow series, where the two top comics creators of the late ’60s found common ground, deploying their considerable artistic abilities to make great comic books designed to mirror the turbulent times and, in the process, compose a truly important American graphic novel, chapter by chapter.

“Getting real” was the core essence of Marvel’s success in

68 #35 • Summer 2024 • COMIC BOOK CREATOR

Justice League of America, World’s Finest Comics TM & © DC Comics.

This page: Denny touched upon social and environmental issues during his runs on Justice League of America (above, #79 [Mar. ’70] and World’s Finest Comics (below, #204 [Aug. ’71]). Covers by Neal.

the ’60s — Spider-Man’s home was in Queens and he worked in Manhattan, Iron Man’s origin happened in Vietnam, the X-Men were schooled in Westchester — but any talk of the politics of the period tended to be superficial and vaguely reactionary, despite token nods to Black power, environmental concerns, and women’s liberation (though, tellingly, the war in Southeast Asia was almost never central to any story.).

“I was peripherally involved in those issues, a non-distinction I shared with millions of liberal, vaguely well-meaning people of middle-class origin,” Denny wrote in an introduction to a 1983 reprinting of his and Neal’s Green Lantern issues. “I signed petitions. I went on marches. I argued against the war and supported Martin Luther King. I subscribed to Ramparts and The Catholic Worker. I lived in the East Village and consorted with some of the headline makers — David Miller, Daniel and Philip Berrigan, Dorothy Day, Paul Krassner — and, I would have insisted, I shared their aspirations. But I was not like them. I lacked their capacity for involvement. I was not a leader. I had the charisma of library paste. I was skinny, shy, self-effacing, with some killer shark personal problems I had yet to recognize. However, I was getting published, every month, in comic books. And suddenly, I was being asked to revamp Green Lantern. It was an opportunity to stop lurking at the edges of the social movements I admired and participate by dramatizing their concerns.”

The revamp was do or die, Denny recalled. “My understanding was that they were going to cancel the book, that the book had no place to go but up… So I came in one day and Julie said, ‘Do you have any ideas for this character? Is there anything you’d like to do with Green Lantern?’ I thought, ‘Well, I’d done a couple of stories that had vaguely socially relevant themes.’ ‘Children of Doom’ was one. It was an anti-war book, which was unheard of at the time.”

He continued, “I was still doing journalism [for News Front], and I was involved in the peace movement, and the civil rights movement — not much involved, I went on a few marches and I fed people occasionally — but it was a chance to maybe take a shot at combining my two professional identities, as a journalist and as a comic book writer. We were aware that we were pushing the envelope, doing things stuff that had not exactly ever been done before.”

Denny explained, “I think it was at that point that Neal and I were both getting very confident in what we could do. We spoke the language of comics well by that time. The other thing is that those stories were about something, and that had very often not been true. I think about that a lot now. Mostly there was no real heart and soul to a lot of comic book stories.”

PRODUCT OF ITS TIME

Green Lantern #76 was put on sale in late February, 1970, the same month when Jack Kirby, the backbone of the Marvel Age of Comics, signed a contract with DC Comics, a coup of epic proportions in the publisher’s fight to hold back the growing threat of Stan Lee and company gaining market share. But ever more important than the creative renaissance at DC were the real-life events of that period. That issue was cover-dated April 1970, the actual month U.S. President Nixon announced the nation had expanded the war in Southeast Asia by invading Cambodia. The subsequent protest resulted in Ohio National Guardsmen killing four unarmed students at Kent State, a watershed event in turning the tide of public sentiment against the Vietnam War.

The “Hard-Traveling Heroes” saga may have lasted for less than three years and 13 issues of Green Lantern (plus a threepart back-up serial in The Flash), its contemporaneous cultural

impact was huge and it remains a unique artifact of a mainstream corporate entity trying to make a sincere and authentic difference during tremendously polarized times.

As Gerard Jones and Will Jacobs wrote in their history, The Comic Book Heroes: “Where DC outdid Marvel was not in introducing social relevance or even an open political bias — although O’Neil did advertise his liberalism in bigger neon letters than anyone at Marvel — but in making them the conscious focus of the entire series. Although action and adventure were still the bulk of every story, the point of the story was the political message. [Steve Englehart’s] Captain America might broaden the scope of super-hero adventures, but Green Lantern/Green Arrow suggested a fundamental new approach to them. Even Steve Ditko hadn’t tried such ripped-from-theheadlines topicality. Here was a comic that would have to press the medium into a radical self-appraisal, a reevaluation of its purposes, just as the old man’s ‘How come?’ had pressed Green Lantern. It seemed inescapable now that the comics community — and the world at large — would have to grapple with the full potential of the medium.”

This page: The original art for the game-changing cover of Green Lantern #76 [Apr. ’70] by Neal Adams was auctioned, with his blessing, for an eye-popping $442,150 in 2015.

COMIC BOOK CREATOR • Summer 2024 • #35 69

Green Lantern TM & © DC Comics.

When Y.E. asked if Green Lantern was at risk of becoming an “Issue of the Month” comic book at the time, the writer replied, “The women’s lib issue was the only one that I did not feel passionately concerned about as a citizen and as a father. We did two stories about the environment and it’s still an issue I give the most to. And racial equality, which is just survival — we have to clean up that act. The American Indian thing I was not close to emotionally, but I think that we got lucky and the story works anyway. Basically that stuff was the same material I would have covered if I were writing magazine articles or novels rather than comic books, because I was honestly, genuinely concerned about those issues.”

Pushing the envelope with the Comics Code Authority as an iconoclast wasn’t much of a concern to the writer, despite his work, in part, being an impetus for a subsequent major rewrite of its rules. Still, the duo drew creative energy by playing “kick the can” with the Comics Code: