OCTOB e R issue

WHO We aRe

The Tribal Art Society features an online catalogue every month listing quality works of Asian art that have been thoroughly vetted by our select members, who are the in-house experts.

By bringing together a group of trusted dealers specializing in Tribal art, our platform offers a unique collection of works of art that collectors will not find anywhere else online. To ensure the highest standards, gallery membership is by invitation only and determined by a selection committee.

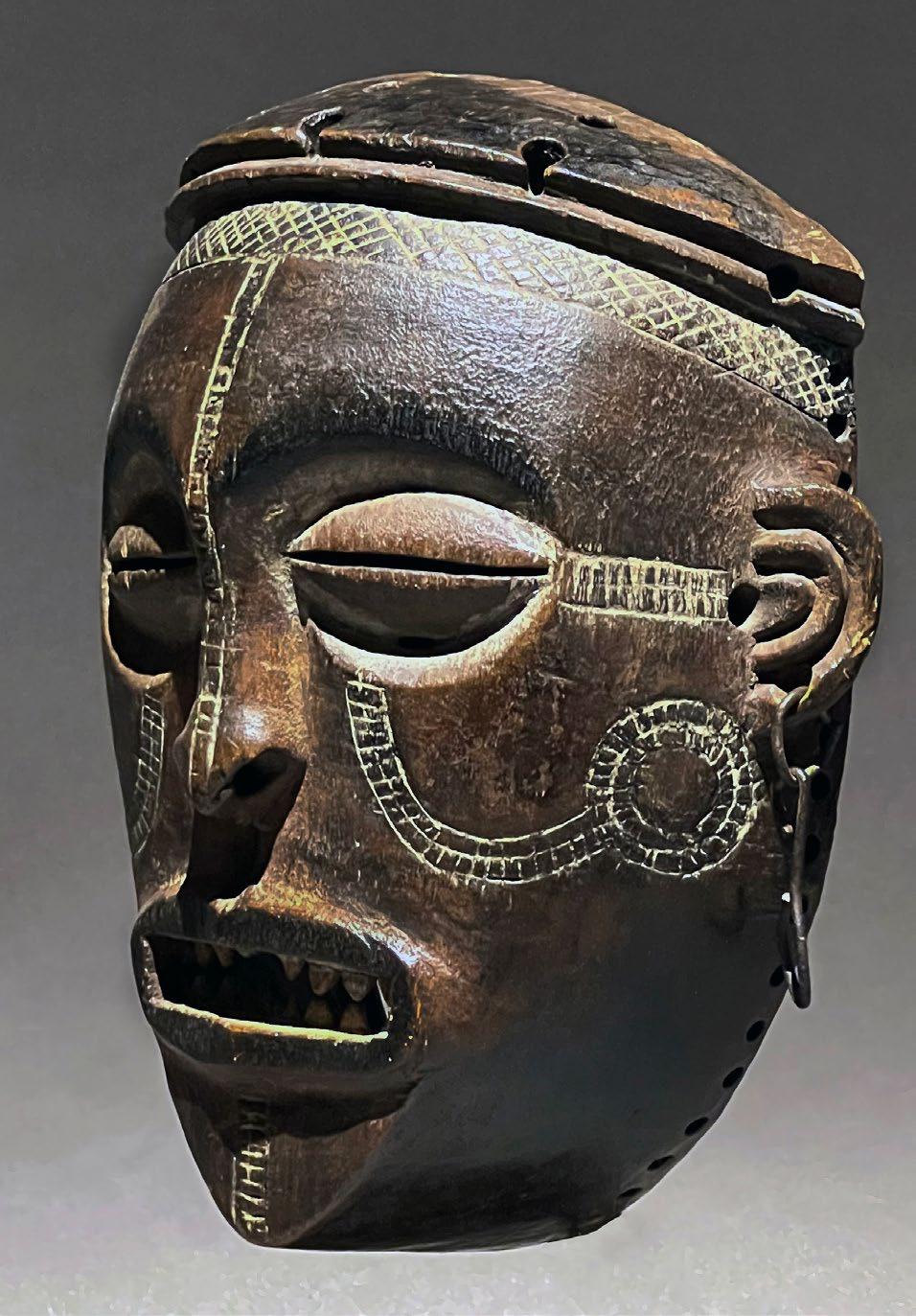

Cover image: Himalayan mask. Presented by David Serra on p. 40 /TribalArtSociety

OCTOB e R a RTWORK s

Pieces are published and changed each month. The objects are presented with a full description and corresponding dealer’s contact information. Unlike auction sites or other platforms, we empower collectors to interact directly with the member dealers for enquiries and purchases by clicking on the e-mail adress.

In order to guarantee the quality of pieces available in the catalogues, objects are systematically validated by all our select mebers, who are the inhouse experts. Collectors are therefore encouraged to decide and buy with complete confidence. In addition to this, the Tribal Art Society proposes a seven-day full money back return policy should the buyer not feel totally satisfied with a purchase.

Feel free to ask the price if the artwork is listed with a price on request.

a CO lle CT i O n O f

Bus H man O s TR i CH egg CO n Taine R s

Egg containers

South Africa

19th and 20th century

Provenance: U.K. collection

Price on request

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y: Adam Prout

T.: + 44 7725 689 801 E.: adam@adamprout.com W.: www.adamprout.com

m assim C lu B

Club

Massim

Trobriand Islands, P.N.G.

The blade with carved scroll decoration, and a zig-zag border to the handle, with an indistinct hand written label

Length: 73 cm

Provenance:

Frank Hurley, Australia (1885 – 1962) photographer, filmmaker, adventurer. Price on request

Hurley worked on Shackleton’s Antarctic expedition of 1914 – 1917, photographing the Endurance whilst being marooned with the rest of the crew. In the 1920s he mounted various expeditions to Papua New Guinea, which involved film making and collecting on behalf of the Australian museum and himself. He stored a number of artefacts in a log cabin at Whale Beach, which became an exotic setting for Sydney’s glitterati attending raucous parties there in the 1930s. Selling the property after the war, he left the contents of the cabin, of which this was kept by the new owners, who moved to London in 1959.

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y: Adam Prout

T.: + 44 7725 689 801

E.: adam@adamprout.com

W.: www.adamprout.com

s e P i K 'Panggal' sag O s PaTH e OR TR ee

B a RK Pain T ing O f an an C es TR al figu R e

Painting

Keram River, East-Sepik Province, P.N.G.

Early 20th century 139 cm (h) x 111 cm (w)

Provenance:

Georg Hölker between 1934 and 1938 for the collection of The Divine World Missionaries, founded at Steyl near Venlo in the Netherlands in 1875 Price on request

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Zebregs&Röell

+31 6 207 43671

dickie@zebregsroell.com www.zebregsroell.com

"The painting in non-binded pigment on sago spathe, bark of a sago palm, depicts an ancestral figure surrounded by a saw fish, two masks and several floral and seed motives.

Sago spathe is a protective, often fibrous or woody sheath that encloses the flower cluster (inflorescence) of the sago palm, particularly Metroxylon sagu. The spathe is also a large bract that shields the palm's developing flowers and seeds until they are mature. In traditional practices, the spathe of the sago palm is sometimes harvested for its material, which can be used for various purposes, including crafting containers, tools, or decorative items. The sago palm is mainly valued for the starchy pith within its trunk, which is processed into sago, a staple food in many parts of Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands.

The original mission house in Steyl, where the Society of the Divine Word (SVD) was founded in 1875, is now home to the Missiemuseum Steyl, founded in 1931. Items like the present panggal were brought back by missionaries from all corners of the globe, particularly Asia, Africa, and Latin America. They served to educate apprentice missionaries about what they would encounter on a mission. The museum's exhibits, which include taxidermy, cultural artefacts, Indigenous art, and items related to the everyday life of people in mission areas, offer a global perspective on the history of missionary work and the intercultural encounters that were part of the SVD’s mission. Visitors can explore displays that illustrate the interaction between European missionaries and the cultures they engaged with, offering perspectives on both controversial and positive aspects of missionary work. However contentious, one could be thankful the missionaries decided to collect, preserve and exhibit all these objects instead of burning, throwing them in lakes or destroying them in the name of our Good Lord.

A very fine and powerfully carved ancestor figure with an elongated nose reaching to the pubis. The forehead is decorated with a stylized splayed animal.

Ramu figu R e

Ancestor Figure

Ramu River Delta or Manam Island, P.N.G., Melanesia 19/20th century

Wood with dark brown and dry patina of age

Height: 21 cm

Provenance: Maurice Bonnefoy, D’Arcy Galleries, New York

Private collection, Switzerland

Private collection, the Netherlands

Exhibition:

N° 9 of the exhibition The SURREAL in a collection of 20th century European drawings and in the Early Art of New Guinea, Parcours des Mondes 2024

Price : 12.500 euros

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y: Anthony J.P. Meyer

T.: +33 (0) 6 80 10 80 22

E.: ajpmeyer@gmail.com

W.: www.meyeroceanic.art

C HOKW e mas K

Mask Mwana pwo Chokwe/Tshokwe

Angola

Height: 21,5cm

Wood, pigmants and metal

Provennance:

Pierre Dartevelle, Brussels, 2006

Peter Michael Boyd, Seattle, 2010

Private collection

Price on request

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Mark Eglinton

M.: +1 646-675-7150

E.: markeglinton@icloud.com

IG.: @markeglintontribalart

d ivinaT i O n OB je CT/ Anyedo P endan T

Pendant Kulango

Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Ghana

Early Voltaic (19th century or before)

Copper alloy

Height: 5,5 cm

Provenance:

Private collection, Spain

Price: 2.500 euros

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y: David Serra

T.: +34 (0) 667525597

E.: galeria@davidserra.es

W.: www.davidserra.es

es K im O H un T ing im P lemen T

Float element

Old Bering Sea or Punuk

Archaic Eskimo, Alaska

Prior to 800 A.D.

Walrus tooth Height: 5 cm

Provenance:

Christie’s New York, 13 January 2003, lot 207

Private collection, USA

Galerie Flak, Paris

Private collection, Nice, France, acquired from the above in 2006

Guy Porré & Nathalie Chaboche

Tas exclusive price: 7.000 euros

Throughout history, Eskimo cultures have shared the belief that all things in the physical world are imbued with a living spirit, “yua” or “inua”. In order to gain favor with the spirits controlling the animals, a hunter had to approach his prey in a respectful manner. It was believed that decorated objects, through their beauty, attracted the prey and at the same time honored its spirit.

The implement presented here was affixed to a float. As noted by Ann Fiend-Riordan in "Yup'ik Elders at the Ethnologisches Museum Berlin, Fieldwork Turned on Its Head", pages 54-55, "this device is put into the leather edges of the hole with the help of strong seal straps, which are gathered and tied and therefore make the hole air-tight."

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Julien Flak

M.: +33 6 84 52 81 36

E.: contact@galerieflak.com

W.: www.galerieflak.com

fang Ha RP

Harp (bow-harp) / Chordophone

Lumbo(Loumbo/Lumbu) or Fang Gabon, Estuarie region

Height: 63cm

Wood, pigment, glass, hide/leather/ skin, metal, plant fiber

Provenance:

Ex Michael Averes collection, NYC

Ex Greta Schreyer collection, NYC

Publication:

Die Phangwe, Gunter Tessmann, Berlin 1913

Price on request

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Mark Eglinton

M.: +1 646-675-7150

E.: markeglinton@icloud.com

IG.: @markeglintontribalart

Himalayan mas K

Mask

Himalaya

Early 20th century or before

Wood and metal

Height: 27 cm

Provenance: F. Pannier, France

Gustavo Gili

Rosa Amorós, Spain (acquired in 2001)

Publications:

Expo. Cat.: Enigmas de las Montañas. Màscaras Tribales del Himalaya. Fundación Antonio Pérez. Cuenca 2005. Centre Culturel de Guyancourt. França. 2006. PP. 58-59. No 11. Price on request

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

David Serra

T.: +34 (0) 667525597

E.: galeria@davidserra.es

W.: www.davidserra.es

Bamana mas K

Hyena mask suruku

Bamana, Kore society

Wood, sacrificial patina

Provenance:

Milton Sikes gallery, Palo Alto, 1960´s

John and Dianne Anderson

Price: 4.500 euros

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Adrian Schlag

T.: +34 617 666 098

E.: adrian@schlag.net

W.: www.tribalartclassics.com

K aT sina d O ll

Katsina doll

Carved by Hopi Chief Wilson Tawaquaptewa, Oraibi (1873-1960)

Arizona, USA

Circa 1930

Carved wood (cottonwood), natural pigments, feathers

Height: 17,5 cm

Provenance:

Michael Higgins, USA

Private collection, Paris, France

Tas exclusive price: 7.000 euros

Katsina dolls (or Kachinas) represent spirits or gods from the pantheon of the Pueblo peoples in the American Southwest. Given to children, Katsina dolls constituted a pedagogical tool allowing them to familiarize themselves with the spiritual world and perpetuating knowledge of the founding myths on which their society was based.

This doll is the work of a Hopi master carver, Wilson Tawaquaptewa (1873-1960).

The color palette on this doll is typical of this artist's carvings.

Oraibi chief Wilson Tawaquaptewa (was both a prominent a spiritual and political Hopi leader; he is also celebrated as the greatest Hopi kachina doll carver. For more information about Katsina dolls and Tawaquaptewa, please refer to the new publication “L’Appel des Kachinas - Katsina Calling”: https://www.galerieflak.com/publications/

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Julien Flak

M.: +33 6 84 52 81 36

E.: contact@galerieflak.com

W.: www.galerieflak.com

KOngO figuRe

Nkisi statuette

Kongo

D.R. of the Congo

Early 20th century

Carved wood, glass and pigments

Height: 18 cm

Provenance:

Richard de Saint Alphonse, Paris. Christine Valluet & Yann Ferrandin, Paris

Chambers, USA, acquired from Galerie Valluet in 1999

Price on request

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Julien Flak

M.: +33 6 84 52 81 36

E.: contact@galerieflak.com

W.: www.galerieflak.com

Kongo power figures rank among the iconic genres of African art.

An embodiment of power and beauty, Nkisi statuettes are ""ambivalent and multifunctional, [they] threaten as much as they protect and heal"" (see ML Felix, “Art & Kongos”, 1995, p. 67).

14

KORW a R amule T

Amulet

Cenderawasih Bay (Geelvinck baai), Korwar Area, Vogelkop Peninsula, Indonesian New Guinea, Melanesia 19/20th century

Dark wood with a good patina of age and wear

Height: 23,5 cm

Provenance:

Field collected by, and acquired from, Koos Knol & Paula van den Berg, Wormerveer

Publication:

Galerie Meyer - Oceanic & Eskimo art, TEFAF 2010

The Art of Korwar, Fig. 7

Exhibition: N° 3 of the exhibition The SURREAL in a collection of 20th century European drawings and in the Early Art of New Guinea, Parcours des Mondes 2024

Price: 8.500 euros

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y: Anthony J.P. Meyer

T.: +33 (0) 6 80 10 80 22 E.: ajpmeyer@gmail.com W.: www.meyeroceanic.art

A powerfully carved Korwar amulet depicting a squatting ancestor behind a decorative shield. These amulets were worn individually or in groups on necklaces as portable charms. Strings passed through the openwork under the figure’s head, avoiding piercing the head or base. The uncarved wood sections were often wrapped in red or blue trade cloth, with necklaces adorned with colored glass beads and other magical elements.

Reference: De Clercq, Frederik S.A. & Schmeltz, Johannes D.E.: ETHNOGRAPHISCHE BESCHRIJVING VAN DE WEST-EN NOORDKUST VAN NEDERLANDSCH NIEUW-GUINEA. Leyde, P.W.M. Trap, 1893. Greub, S. (ed.): ART OF NORTH WEST NEW GUINEA. New York, Rizzoli International Publications. 1992. Van Baaren, Th. P.: KORWARS AND KORWAR STYLE. Mouton and Co., The Hague-Paris 1968.

K OTa Knife

Knife Musede/Musele/Onzil

Kota

Gabon

Steel, wood and brass

30 x 29.5cm

Provenance:

Ex Jeff Hobbs, Wellington, NZ

Robert Bourden collection, Vermont, US

Norman Hurst, Cambridge, Mass

Price on request

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Mark Eglinton

M.: +1 646-675-7150

E.: markeglinton@icloud.com

IG.: @markeglintontribalart SOLD

lOB i figu R e

Figure

Lobi Burkina Faso 19th century

Wood Height: 78 cm

Provenance: Private collection, France

Renaud Vanuxem, France

Price: 4.500 euros

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Guilhem Montagut

T.: + 34 931 414 319

E.: monica@galeriamontagut.com

W.: www.galeriamontagut.com

Length:

M A go mas K

Mask

Maou

Northwest Region, Ivory Coast

Early 20th century

Wood Height: 25 cm

Provenance: Private collection, United Kingdom (acquired by descendance)

Price: 1.900 euros

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

David Serra

T.: +34 (0) 667525597

E.: galeria@davidserra.es

W.: www.davidserra.es

ne W guinea H ig H lands s H ield

War shield

Wahgi Valley, Highlands, P.N.G.

Early 20th century

Carved wood, pigments and rattan

Height: 146 cm

Provenance:

Collection of the Catholic Mission, Minj since the 1950s

Acquired from the Catholic Mission by Chris Boylan, 1978-1979

Private collection, Europe

Price on request

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Julien Flak

M.: +33 6 84 52 81 36

E.: contact@galerieflak.com

W.: www.galerieflak.com

Warfare has been at the center of Highlands life since immemorial times. The shield has always been considered an extension of the warrior himself.

When warfare was expected, warriors repainted their shields to ensure that the colors shone brilliantly against the sun to dazzle and threaten the opposing side. In the western Pacific, shields bore the name of warriors, and possessed a life force, or spirit, that connected them to their ancestors.

The example shown here is a superb, early example of Highlands war shield.

s enufO mas K

Mask Senufo Ivory Coast Wood Height: 34 cm

Provenance: Franco Monti, Milano Price on request

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y: Adrian Schlag

T.: +34 617 666 098

E.: adrian@schlag.net

W.: www.tribalartclassics.com

se P i K dagge R

KORR igane

Dagger

Iatmul

Middle Sepik Region, P.N.G., Melanesia

19th/20th century

Cassowary bone (Casuarius casuarius) (tibiotarsus) with a beautiful patina of age and use

Length: 39 cm

Provenance: Collected during the Voyage of the Korrigane (1934/1936)

Comte & Comtesse de Ganay, Charles and Régine van den Broek, and Jean Ratisbonne; a collection of 2500 objects gathered on the expedition of the ""Korrigane.""

Jean Fernand Gabriel Marie Ratisbonne (1908 - 1993), photographer of the expedition

Philippe or René Ratisbonne, Paris

Auction by Rennes Enchères, May 31, 2010, Lot 32, Oceanic Collection from the Voyage of the Korrigane, Jean Roudillon Expert Jean Ratisbonne

Daniel Vigne, Filmmaker, Paris/Uzès

Exhibition: N° 23 of the exhibition

The SURREAL in a collection of 20th century European drawings and in the Early Art of New Guinea, Parcours des Mondes 2024

Price: 6.500 euros

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Anthony J.P. Meyer

T.: +33 (0) 6 80 10 80 22

E.: ajpmeyer@gmail.com

W.: www.meyeroceanic.art

A very fine and early fighting dagger adorned with two large ancestral faces above a register of geometric or floral motifs. These weapons were primarily used in two ways : one as a close combat weapon for man-to-man fighting, and the other as a “coup de grâce” against a wounded enemy. The attack generally targeted the base of the neck. This weapon was also used for assassination.

Tiv figu R e

Standing figure

Tiv Nigeria

Height: 97 cm

Wood

Provenance:

Martien Coppens (1908-1986)

Geldrop John Tenney, s

́Hertogenbosch, 2007

Jacobus Bakkers (1947-2020), Wehl

Publication:

Coppens (Martien), Negerplastiek, fotografisch benaders (Negro sculpture, a photographic approach)

Eindhoven, private edition, 1975, page 157-158

Price on request

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y:

Adrian Schlag

T.: +34 617 666 098

E.: adrian@schlag.net

W.: www.tribalartclassics.com

v uvi mas K

Mask

Vuvi Gabon 19th century Wood, pigments, fibers

Height: 24 cm

Provenance: Private collection, France Price: 2.500 euros

O B je CT P R esen T ed B y: Guilhem Montagut

T.: + 34 931 414 319 E.: monica@galeriamontagut.com W.: www.galeriamontagut.com