Volume Issue 28 April 2023 the 05 SELF-PORTRAIT WITH EYES TURNED INWARD, PROVIDENCE 11 60 FEET, 6,000 MILES 13 “LET THE BEAT FUCK YOU” THE SENSATIONAL ISSUE The College Hill Independent * 46 09

From the Editors

A pair of swans have built their nest in the lee of the rusted bridge on the western bank of the Seekonk. Walking by a few nights ago, I saw one float to the shore and grab a stick, loft it toward the nest, and drop it in the water about a foot away. This happened a couple of times. I often gather the things I like around me, without really meaning to use them; at the center of concentric rings of books I have thieved from various shelves is the desk where I rarely read them. At about 4 p.m. the next day, on the other side of College Hill, a guy was feeding robins crumbs from a loaf of brown bread on the large stone steps that descend to the Providence river. In a fairytale moment, one of the birds landed on his shoulder and leaned forward on its pencil-like stilts to peck morsels out of his hand, while the guy just walked along like some jowly quartermaster. On the other side of the steps, though, sat his green backpack, and, one safe and respectful foot away, a swan. Its silly-straw neck arched over the distance and poked its head into the bag, pulling out a book.

Masthead*

MANAGING EDITORS

Zachary Braner

Lucia Kan-Sperling

Ella Spungen

WEEK IN REVIEW

Karlos Bautista

Morgan Varnado

ARTS

Kian Braulik

Corinne Leong

Charlie Medeiros

EPHEMERA

Ayça Ülgen

Livia Weiner

FEATURES

Madeline Canfield

Jane Wang

LITERARY

Ryan Chuang

Evan Donnachie

Anabelle Johnston

METRO

Jack Doughty

Rose Houglet

Sacha Sloan

SCIENCE + TECH

Eric Guo

Angela Qian

Katherine Xiong

WORLD

Everest Maya-Tudor

Lily Seltz

X

Claire Chasse

DEAR INDY

Annie Stein

BULLETIN BOARD

Mark Buckley

Kayla Morrison

SENIOR EDITORS

Sage Jennings

Anabelle Johnston

Corinne Leong

Isaac McKenna

Sacha Sloan

Jane Wang

STAFF WRITERS

Tanvi Anand

Cecilia Barron

Graciela Batista

Mariana Fajnzylber

Saraphina Forman

Keelin Gaughan

Sarah Goldman

Jonathan Green

Sarah Holloway

Anushka Kataruka

Roza Kavak

Nicole Konecke

Cameron Leo

Abani Neferkara

Justin Scheer

Julia Vaz

Kathy/Siqi Wang

Madeleine Young

COPY CHIEF

Addie Allen

COPY EDITORS / FACT-CHECKERS

Qiaoying Chen

Veronica Dickstein

Eleanor Dushin

Aidan Harbison

Doren Hsiao-Wecksler

Jasmine Li

Rebecca Martin-Welp

Kabir Narayanan

Eleanor Peters

Angelina Rios-Galindo

Taleen Sample

Angela Sha

Jean Wanlass

Michelle Yuan

DEVELOPMENT COORDINATOR

Angela Lian

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Jolie Barnard

Kian Braulik

Angela Lian

Natalie Mitchell

WEB MANAGER

Isaac McKenna

WEB EDITORS

Hadley Dalton

Arman Deendar

Ash Ma

GAMEMAKERS

Alyscia Batista

Anna Wang

*Our Beloved Staff

Mission Statement

COVER COORDINATOR

Zora Gamberg

DESIGN EDITORS

Anna Brinkhuis

Sam Stewart

DESIGNERS

Nicole Ban

Ri Choi

Ashley Guo

Kira Held

Xinyu/Sara Hu

Gina Kang

Amy/Youjin Lim

Andrew Liu

Ash Ma

Tanya Qu

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Anna Wang

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Sophie Foulkes

Izzy Roth-Dishy

ILLUSTRATORS

Sylvie Bartusek

Lucy Carpenter

Bethenie Carriaga

Julia/Shuo Yun Cheng

Avanee Dalmia

Michelle Ding

Nicholas Edwards

Jameson Enriquez

Lillyanne Fisher

Haimeng Ge

Jacob Gong

Ned Kennedy

Elisa Kim

Sarosh Nadeem

Hannah Park

Luca Suarez

Yanning Sun

Anna Wang

Camilla Watson

Iris Wright

Nor Wu

Celine Yeh

Jane Zhou

MVP

Justin

The College Hill Independent is printed by TCI in Seekonk, MA

The CollegeHillIndependent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and selfcritical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

01 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT 00 NEW STANDARD TIME Isabel Yang 02 WEEK IN YAS Charlie Medeiros & Corinne Leong 03 SHARE THE FANTASY Justin Scheer 05 SELF-PORTRAIT WITH EYES TURNED INWARD, PROVIDENCE Anabelle Johnston 08 “FIFTEEN BUCKS IS NOT ENOUGH” Li Ding & Sarah Mann

BALLET RECITAL (FLIPBOOK) Joshua Koolik

A SMALL HOUSE IN SOUTH JERSEY Evan Donnachie

60 FEET, 6,000 MILES Caleb Stutman-Shaw

“LET THE BEAT FUCK YOU” Kolya Shields

THE GHOST IN THE RECORD(ING) Eric Guo 17 ROOMS Camilla Watson 18 LINKEDINDIE Annie Stein

BULLETIN Mark Buckley & Kayla Morrison This Issue

09

10

11

13

15

19

46 09 04.28

-ZB

Letters to the editor are welcome; scan the QR code here or email us at theindy@gmail.com!

in YAS

The Plot Chickens

Yas Chicken. Y-A-S Chicken… When my edi tor-in-crime Corinne first told me the name of the new restaurant on Thayer Street where she was getting dinner, I made her repeat herself. “YAS Chicken.” I kept saying the name to myself over and over for the rest of the night. Like some kind of psychic mantra, I felt the power of those three syllables course through me every time I dared to invoke Providence’s newest fried chicken spot. YAS Chicken. I texted my bff studying abroad:

12 hours and eight minutes later, he responded:

Even across the Atlantic Ocean, he could feel the seismic ripples of YAS Chicken, the sheer gravitas of its name leaving him “ .”

The next morning I texted Corinne:

without that long, stretched cheese-pull I had been seeing in the news and the media.

Corinne and I enjoyed our meals on the steps of the now-defunct Blue State Coffee. Sitting pensively over parmesan-covered fries (would recommend), I thought about the volatile ecosystem of Thayer Street, of all of the businesses that have come and gone. While some establishments are bound to stay open far past the end-times (Urban Outfitters, Sneaker Junkies, etc.), many of our local spots disappear just as quickly as they pop up. Allow me to light a metaphorical candle for the fallen stores of Thayer-past… RIP Tealuxe, By Chloe (killed by Beatnic), old Ceremony, that Army/Navy Surplus Store, CBD American Shaman, Pie in the Sky, Subway, and so many others.

Will YAS Chicken be YAS enough to withstand the sands of time? Or will it meet the same tragic fate as many which have come before: an empty storefront, a demolished building, being bought out by Pokeworks? While I may be hopeful for many YAS years ahead of us, I probably shouldn’t count my YAS eggs before they hatch.

–CM

–CM

Love Me Tender

Four hours and 46 minutes later, she emphasized my message.

I went to YAS Chicken twice this week. First with my friend/roommate, illustrious Indy designer Sam Stewart :3, and later with Corinne.

When Sam and I went, I asked him to take a picture of me in front of YAS Chicken. I leaned my body against their towering sign. Smile. Click YAS.

Inside, I ordered the Number 9 YAS Meal: three piece chicken tenders, parmesan fries, and a soda of my choice. I got Pepsi . The woman working the counter asked if I wanted YAS sauce (she also said that she liked my hair but let’s not dwell on that). Of course I wanted YAS sauce. “Yes!” I responded confidently, leaving the register to go wait for my food by the trash cans.

The food was…good! The chicken—good; the fries—good; the Pepsi—good. Good job YAS Chicken.

Sam got the Cheesy Chick: a fried chicken sandwich stuffed with “oozing pepper jack cheese,” as described by YAS Chicken’s website. He liked it.

Three days later, I went back to YAS Chicken with Corinne. Round Two. YAS Chicken: All Stars. I knew I had to change it up, give all the Indy-nators at home something different to read about—something fresh.

I ordered the Korean corn dog. Korean corn dogs have definitely been having a cultural moment as the Instagramable street food du jour. In fact, food magazine Bon Appétit even called 2021 “The Year of the Korean Corn Dog.” I first heard of them through infamous Youtuber Trisha Paytas, who has made (according to my rough count) 17 videos reviewing Korean corn dogs from her car.

My corn dog was…devastatingly…just okay The breading was soft, failing to give me that crisp crunch I expected. Inside the corn dog, there just wasn’t enough cheese, leaving me

Because I don’t quite possess the Emojional lexicon necessary to describe my first YAS Meal as Charlie so -ly did, I instead invoke anoth er image: the YAS chicken. In my search for a portrait of reference from which to describe her sublime visage, I find her elusive, fleetingly vis ible only on every 11th @yaschicken Instagram Reels thumbnail, or else painted upon the walls of the YAS Palace itself. Look into her glossy eyes, gazing beyond all we can hope to compre hend. Parse the benign expression on her face. Pure impotence. Wings flung to the wind with cherubic abandon. She seems, to me, to repre sent all of us in the face of Thayer Street’s latest Grand Restaurant Opening (located in the brick fortress that also houses Soban, another chicky relic): helpless, awestruck, alive.

Whispers of the birth of this humbling chicken paradise surfaced with the same inten sity as those about the resident Good-Looking Guy at another Thayer-adjacent grand-opener, which sells cookies. (Stripped of all identify ing features in the hopes that his employer’s competitor Insomnia Cookies will not be able to put out a hit on this man’s poor, “really friendly, so nice, confident in a cocky, appealing way” soul, I can only tell you what I’ve been told by many: He is “really friendly, so nice, confident in a cocky, appealing way.”) I feel that Charlie has adequately covered the kind of pre-verbal, gleefully catatonic state that merely hearing the establishment’s name induces, so I will focus on the surrounding buzz. Friends told me that the line for YAS Chicken wrapped around the block. That, in an experience reminiscent of each College Hill Independent issue launch party, they waited two hours and still couldn’t get in.

I bit into my first Yasville Hot about a month after the restaurant’s Yoors (YAS doors) opened, on a freezing walk back to my dorm. I did this because, within the restaurant, bodies were packed wall to wall. Fighting my way to the register, I felt I had submitted myself to a current that was certain to thrust me from this mortal coil. Tears studded my big brown eyes as the LED menu bobbed in and out of vision, barking item names that registered like

imperatives: “YA HOT N YA COLD,” “MAC ZADDY,” and “THE SUFFERING.” The crowd was populated by people young and old, often shrouded in locks of colorful hair. That first bite in 30-degree weather was everything I had imagined it to be. Sumptuous, complex, demanding replication.

When Charlie and I returned to YAS Chicken for field research outside of peak hours, the place was remarkably empty. Biting into my latest in a series of Yasville Hots outside the carcass of Blue State Coffee, I shared his unfortunate sentiments. Devastatingly…just okay. A GCal notification sprang from my phone. A pressing reminder to “YAS Charlie (4 – 4:30 pm).”

Staring into the restaurant’s empty windows, I found myself yearning for the chaos I’d experienced upon my first encounter with YAS Chicken. All that organic human contact: Meeting the lifeless eyes of ticket number 132 after her sandwich fell with a wet thud, shredded lettuce scattering across the floor like precious pearls. A stranger holding the door open for me. That same stranger immediately letting the door go, allowing it to pop me square in the face.

I thought about something a professor had told me about their time visiting Duke. Near the university, there was a gated housing complex built for Durham’s nascent Google bros. It’s like tech Disneyland, they spat. In addition to the apartments, there were conference rooms, squash courts, wave pools. All to manufacture interaction. When they mentioned that the complex possessed in-building printers, their eyes glazed over a little, like they had finally found the monstrosity’s one unimpeachable element.

Twin pastry flames Zinneken’s Waffles and Feed the Cheeks boasted pristine storefronts just two blocks from where we sat. For a while I had struggled to identify what gave YAS Chick-

02 VOLUME 46 ISSUE 09 WEEK IN REVIEW

TEXT CHARLIE MEDEIROS & CORINNE LEONG DESIGN TANYA QU ILLUSTRATION HAIMENG GE

A fragrance is a slippery commodity. After somewhere between five minutes and an hour of exposure to the same smell, we stop being able to detect it due to olfactory fatigue, also called olfactory adaptation (apparently scientists disagree on whether to deride the body for getting tired or commend its survival instincts), so wearing a fragrance is for the most part not for the person wearing it but for those they pass throughout the day. It’s sold on a shelf next to other cosmetics, and the store next door probably sells clothes or shoes; it is among a set of adornments that, for the last century, marketing strategists and consumer culture at large have regarded as means of individuation and ‘self expression.’ So-and-so’s shoes and pants tell you something about their inner character, and supposedly so does their fragrance.

The only problem is that fragrance stimulates via smell, a sense that, unlike the others, casts doubt on any claim to self-expression. Smelling something means a number of molecules of that thing has bonded chemically to olfactory receptor proteins, and thus has seeped into the neurons extending from the brain. If you smell something, it is in you and, chemically speaking, almost indistinguishable from ‘you.’ Consequently, smell, unlike the other four basic senses, calls into question the perceptual framework by which we consign certain things to the ‘outside world,’ and other things to the category of ‘self’ or ‘inside.’ To smell something is to detect the presence of that something in the air. The scent stimulus is unable in itself to plot the source of the smell in time or space, and so it fails to orient the smeller with respect to the source and as distinct from the source. (True, smelling repeatedly while moving through space might reveal a source by way of some cognitive effort and other sensory clues, but the smell itself has no direction.) By contrast, sight, sound, and touch all work, in one way or another, toward delimiting objects in the field of perception and, in turn, delimiting the self with respect to those objects. Taste is a bit ambiguous in this regard, but it doesn’t blur boundaries to the extent that smell does. Further still, because something only gives off a smell if it is somehow shedding its molecules into the air, in a very literal sense, to smell something is to deny the invariance and finitude of the smelled object.

I think this might have something to do with the startling power of smell to evoke memory. This sort of memory is not just an image of a past thing pulled into present awareness, but rather has the property of transporting the smeller back to a scene—a memory that insists on a fluid arrangement of environment, body, and space. This hypothesis is probably better left to neuroscience. But as a student of the humanities, the best I can do is a close reading of the madeleine episode from Marcel Proust’s

What Your Fragrance Can’t Say About You

In Search of Lost Time. To be clear, this essay isn’t about Proust (I haven’t read any Proust besides the madeleine excerpt from a Wikipedia page, so take my reading with a grain of salt), but the madeleine episode does a remarkably good job of illustrating a peculiar feature of smell vis-avis memory: its decomposition of forms.

In this passage the narrator sips tea with madeleine crumbs and is overcome with an “exquisite pleasure,” which after some interrogation gives way to a childhood memory. The narrator attributes this flashback to a particular “taste,” which I take to mean a particular value in the full olfactory palette of taste and smell. After all, human taste receptors can detect only five rudimentary tastes—salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and umami. The depth, nuance and complexity of flavor derives from an interaction of taste with smell—a sense capable of detecting between an estimated 80 million to 1 trillion

what is that something? It is an “essence,” and it bears no trace of an origin, no attachment to an external object. It is no more outside than it is inside. It cannot be assigned a source—it is all around and throughout. He is then identical to and, thus, coextensive with the essence.

The second stage of the flashback:

And suddenly the memory revealed itself … Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom, my aunt Léonie used to give me [a madeleine]...the sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted [and smelled] it.

The image of the moment is conjured as a consequence of the first stage. But the image is

unique scents. After sipping the tea, the narrator has a sort of two-stage flashback experience. He’s first overcome with sensation and an “essence.” He then recalls not some particular thing or person out of context but a scene; more precisely, the memory is an occupation of the remembered scene (of his aunt giving him a madeleine in her bedroom), a fleeting inhabitation of a past self, in a past environment.

The first stage of the flashback goes like this: “An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached with no suggestion of its origin … filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me,

not a two-dimensional field placed before his mind’s eye, not just a photographic rendering of his aunt, or the tea, or even the complete set of objects in their positions around the room; the account has no particular interest in objects but transports to and immerses in the remembered environment. The narrator recalls this scene in the first person and in the imperfect tense, a voice suggesting that the memory is not entirely stuck in the past and complete, but somehow persisting. He is there, surrounded by the scene; its time is not fixed but mobile, not finished but indefinite.

Smell does not map to objects but pervades

03 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT ARTS TEXT JUSTIN SCHEER DESIGN SAM STEWART ILLUSTRATION ZORA GAMBERG

and shades a space along with all of its contents, contesting their boundaries. It makes sense, then, that a smell-induced memory does not set its focus on any particular object, if it can be said to wield focus at all. The memory is of an ambience—as in ambient musician Brian Eno’s definition: “an atmosphere, or a surrounding influence: a tint”—and so is deeply committed to space. But it is also of a deeply internal condition, not just surrounding but permeating, inside and out. “My memory is there, which conveys something of the past into the present,” writes philosopher Henri Bergson. The past lives and persists into the present; one’s present mental state “is continually swelling with the duration which it accumulates,” where “duration” here is something like lived time— consciousness existing in and through continuous time and not differentiable or reducible to discrete instants. For Bergson, the degree of this swelling depends on the sort of states perceived through time. For instance, one swells more “with states more deeply internal [e.g. emotions, feelings, thoughts] … which do not correspond, like a simple visual perception, to an unvarying external object,” and so the smell-induced memory swells more. It persists more powerfully. But it retains space, a destratified space, and swells with that space.

It is because of these properties of smell and smell-induced memory that self-expression (let alone individuation) seems like an impossible demand to make of fragrance, at least by comparison to all of the other (primarily visual) self-expressing adornments for sale. If expressing myself means externalizing some quality of mine—otherwise stored up and hidden inside—so that others can perceive it as belonging to me, then I would think scent is hardly the appropriate medium. Smell is the least capable among the senses of revealing sources or rendering objects, whereas my self-expression depends critically on others being able to attribute their impressions to me and my ‘inner character’ as a well-defined entity, distinct from themselves and delimited in the world.

someone’s fragrance triggers the memory or is present in the memory triggered by another smell—or, more radically, if we understand memory, as Bergson does, to persist constantly in present perception––the smell-memory melts away forms, and the process of self-expression melts away with them.

seat. “In other words,” Dichter writes, “what impressed the buyer was not only the quality of the car but the dramatic realization of what the car would do for the buyer.” The mirror, itself a sort of screen, shows an ideal prospective reality in which the shopper owns the car. For Dichter, the work of successful advertising, or the mode of partial possession enabled by advertising, in large part lies in the viewer’s identification with an ideal version of themselves in the world offered by the advertisement—a projection into that world. The purchase of the commodity for sale, then, is the supposed entryway to that ideal.

If Proust is at all instructive, then memory makes the task of self-expression via scent even murkier. The smell-memory, according to Proust, begins with a pervasion of the smelling subject by an essence which has no origin and to which the subject becomes identical. This absence of origin and process of identification would, I think, derail the process of expression entirely. The smell-memory then transports, summoning a past environment and ambience which bleed into the present. One loses one’s bearings entirely, consciousness sublimated into multiple spaces and times at once. In a word, the smell-memory is gaseous. Whether

+++

A fragrance is a slippery commodity, and fragrance advertising only loosens our grip. Perfume commercials always face a critical challenge: scent cannot be transmitted through a screen. Many ads contain no reference to the quality of the smell itself, often set entirely in an urban or indoor location with no allusion to the natural source of the scent (no bergamot oranges or sandalwood are shown). They appear to drift so far from the objective of advertising the actual product that they are mocked as absurd, occasionally earning an SNL parody. Such was the case with Richard Avedon’s 1985 Calvin Klein “Obsession” campaign, a narrated series of surreal ballets choreographed around a devastating romance and a game of chess, set in an M. C. Escher-esque heap of white staircases and doorways. Fragrance ads tend to convey themes of sex, luxury, elegance, wealth, sophistication, mystique, fantasy, passion, and desire in some sort of narrative space, waiting until the very end to refer explicitly to the fragrance for sale (e.g. a logo or a shot of a perfume bottle). And so they are what’s left of an advertisement stripped of its object. Ads tend to superimpose all kinds of affects and images onto the product it sells; the fragrance ad retains those affects and images, but often loses the product, and all that’s left over are impossible promises. Maybe they’re so ridiculous precisely because they expose the work of advertising.

The perfume commercial is not alone in the challenge—impossibility, really—of transmitting the thing it ultimately aims to sell. No commercial actually lets you have the thing it’s selling, not simply out of a technological limitation but almost by definition; if the advertisement gave you the thing advertised then you wouldn’t have to buy it. And surely the purpose of advertising is to make the viewer buy the advertised thing; or, rather, make the viewer want to buy the advertised thing. More precisely still, in its signification of the thing advertised, the advertisement teases, enabling a partial possession—a having that remains just beyond arm’s reach.

In his book The Strategy of Desire, Ernest Dichter—a revolutionary in the field of advertising for his application of psychoanalysis to corporate marketing, often referred to as the “the Freud of Madison Avenue”—expands on this partial possession as a self-projection into a prospective reality. He recounts that when Chrysler Corporation contracted his firm to improve car showroom sales strategies, his studies determined that shoppers were more readily willing to buy a car if it was positioned near a large mirror in the showroom such that they could see a reflection of themselves in the driver’s

The ideal world on display in the perfume commercial is clearly one of expression without fragrance. Consider L’invitation au rêve - Le Jardin, a 1982 commercial for Chanel No. 5 directed by Ridley Scott (also the director of Blade Runner, Alien, and the landmark 1984 Macintosh Super Bowl ad). Le Jardin opens with a sequence of images, similar in form but unrelated in content, fading into each other: first an English garden, the lawn transforming into an impossibly stretched-out piano keyboard, keys playing automatically between lines of trees; a symmetrical shot of three train tracks extending to the horizon, a passenger train on the leftmost track speeding past the camera; finally, a low angle shot up the side of an office building, an airplane passing in the window reflections. After this sequence, a scene of a woman walking seductively toward a man, who dissolves into nothing. We see her face in close-up from where the man stood, her demeanor intent and unphased. The ad fades to an aerial shot of a skyscraper as the shadow of an airplane glides up and over its exterior, then back to the closeup of the woman as she closes her eyes and tilts her head back, her mouth slightly open in a countenance of sexual satisfaction, as a narrator tells us to “share the fantasy.” It finally fades to a shot of the No. 5 bottle on a featureless blue-and-white background—that is, an image of the product with no context, outside the ad’s primary diegesis, the latter having nothing to do with the fragrance and which, of course, does not have a smell.

Le Jardin speaks through an amalgam of slow fades, extravagant settings, extreme angles, far-fetched imagery, intense gazes and slight smiles. To me, it speaks of dreaminess and fantasy, of a strange kind of classy lust, of power and dynamism. It could be said to speak, by way of surreal illogic, of spontaneity and free-spiritedness. Le Jardin hardly tries to tether these qualities to the bottle of fragrance it’s selling, and only retroactively at that. It certainly can’t tie them to a smell. The presiding logic, then, resembles the (phenomeno)logic of smell, in that a weave of qualities do not trace back to a source or a core. And it is this resemblance that ultimately betrays the speciousness of the original proposition one might expect a fragrance ad to reaffirm—that one can express these qualities through fragrance.

The fragrance commercial fashions an ideal world in which the ostensible function of the commodity for sale is possible precisely without that commodity. Resembling the scent-induced memory, the ideal world into which the viewer self-projects can never be grasped. The perfume advertisement lays bare the contradiction animating consumer capitalism in general: prospective realities promised to follow—but not actually following—from ‘self-expression’ through commodities. Dichter affectionately calls this the “constructive discontent” of a receding goal. When finally, and paradoxically, the commercial cuts to a shot of the perfume bottle: “buy X,” it seems to say, “and the ideal world where X doesn’t need to exist will materialize around you.”

JUSTIN SCHEER B’23 signing off.

04 VOLUME 46 ISSUE 09 ARTS

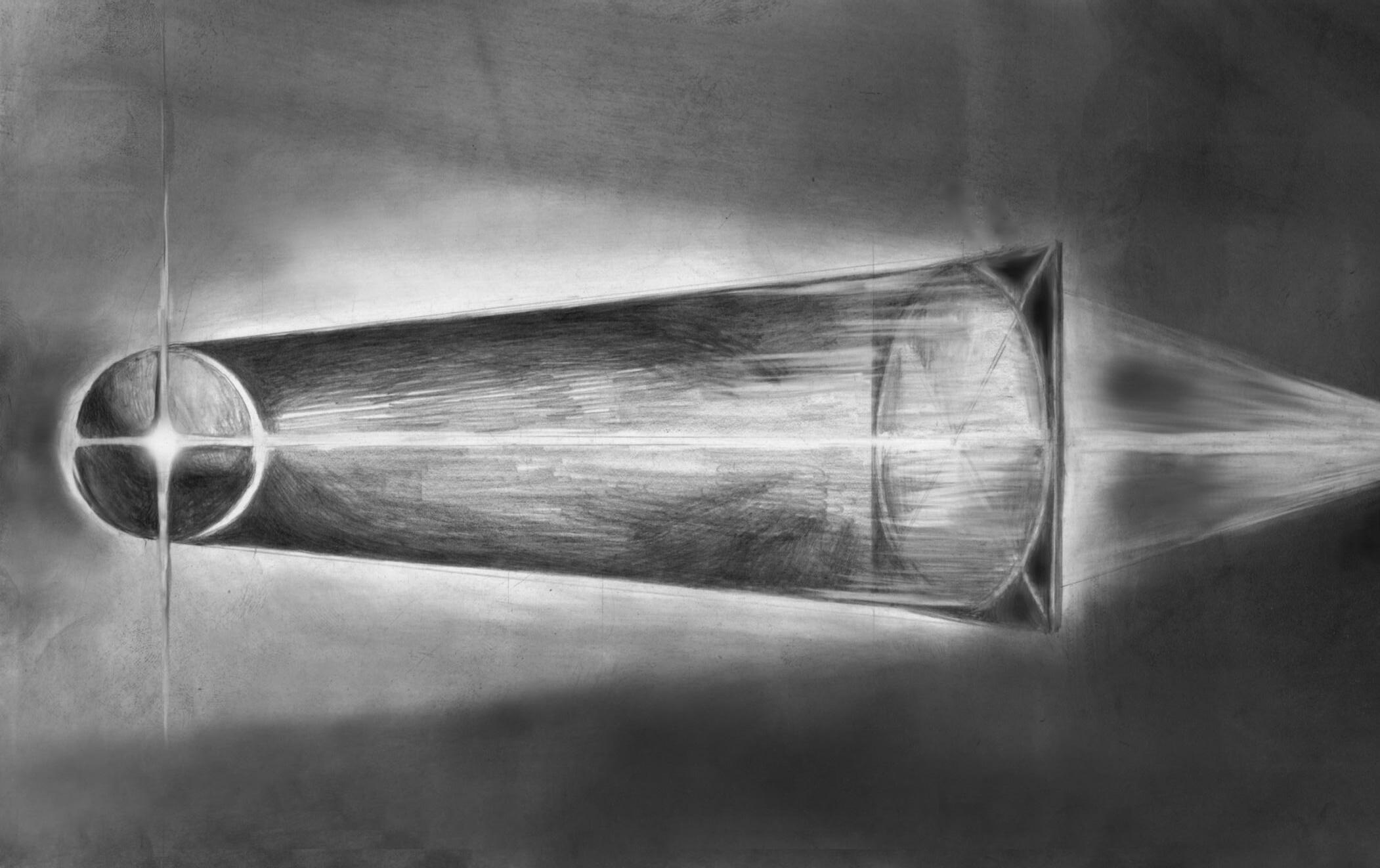

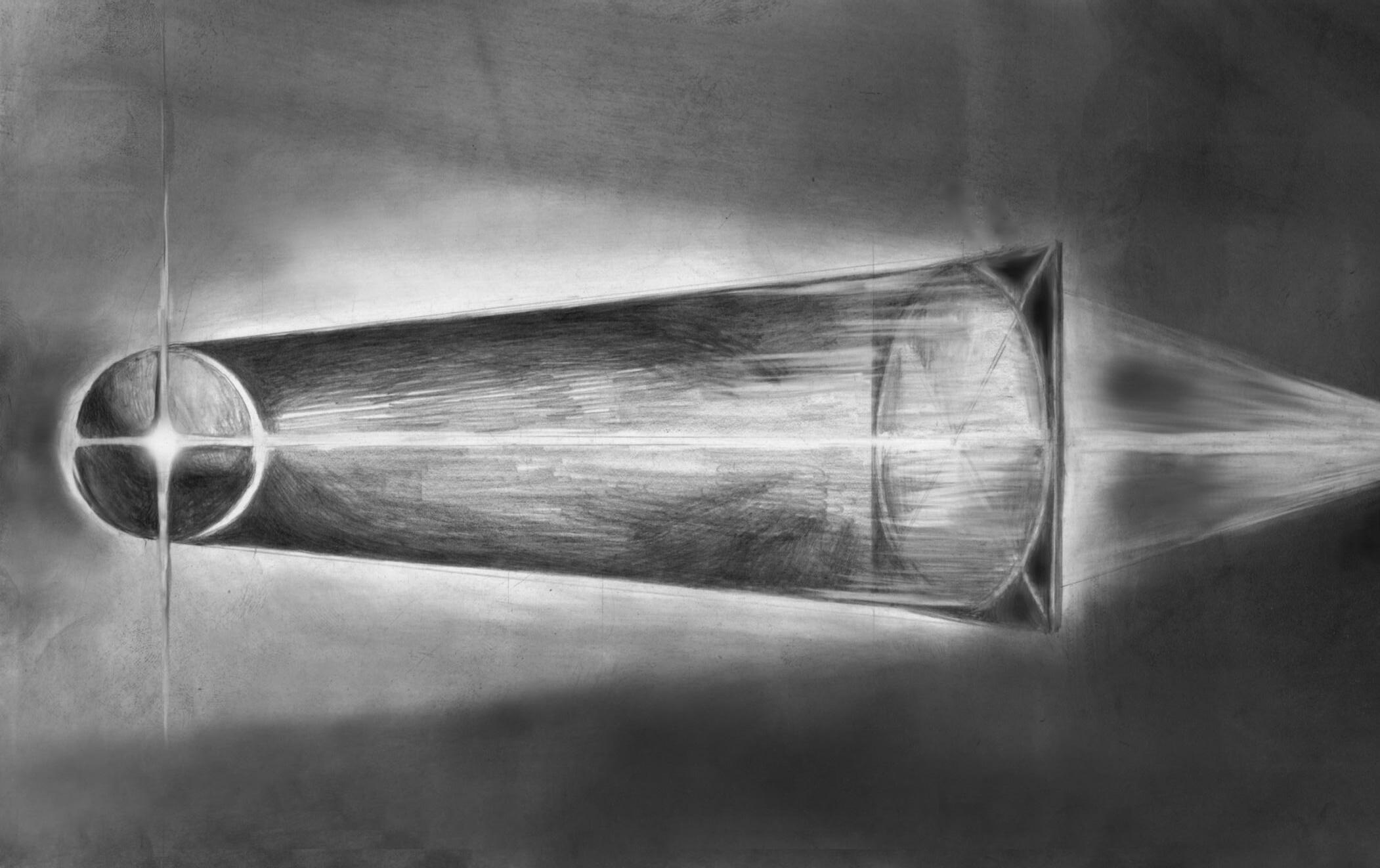

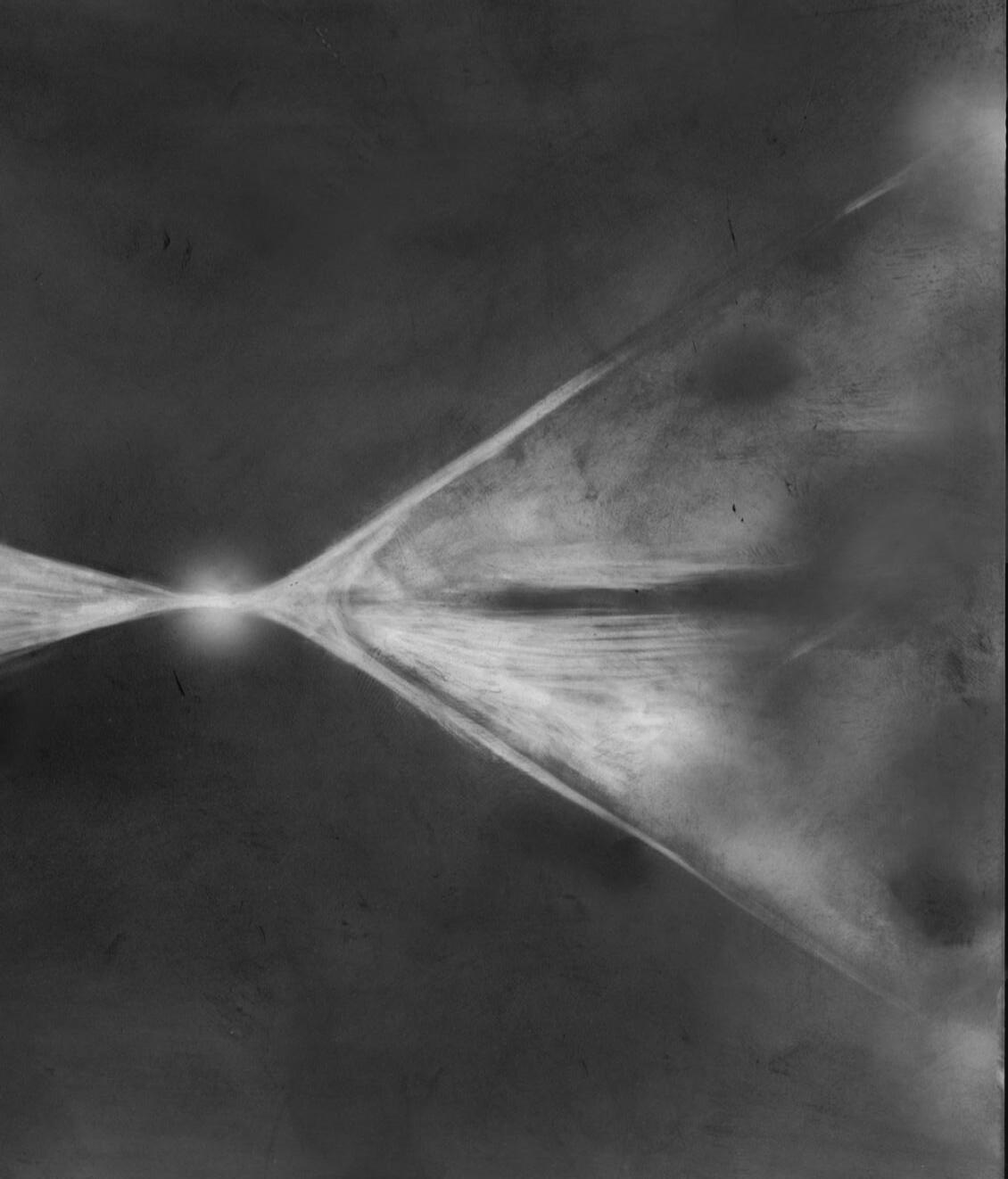

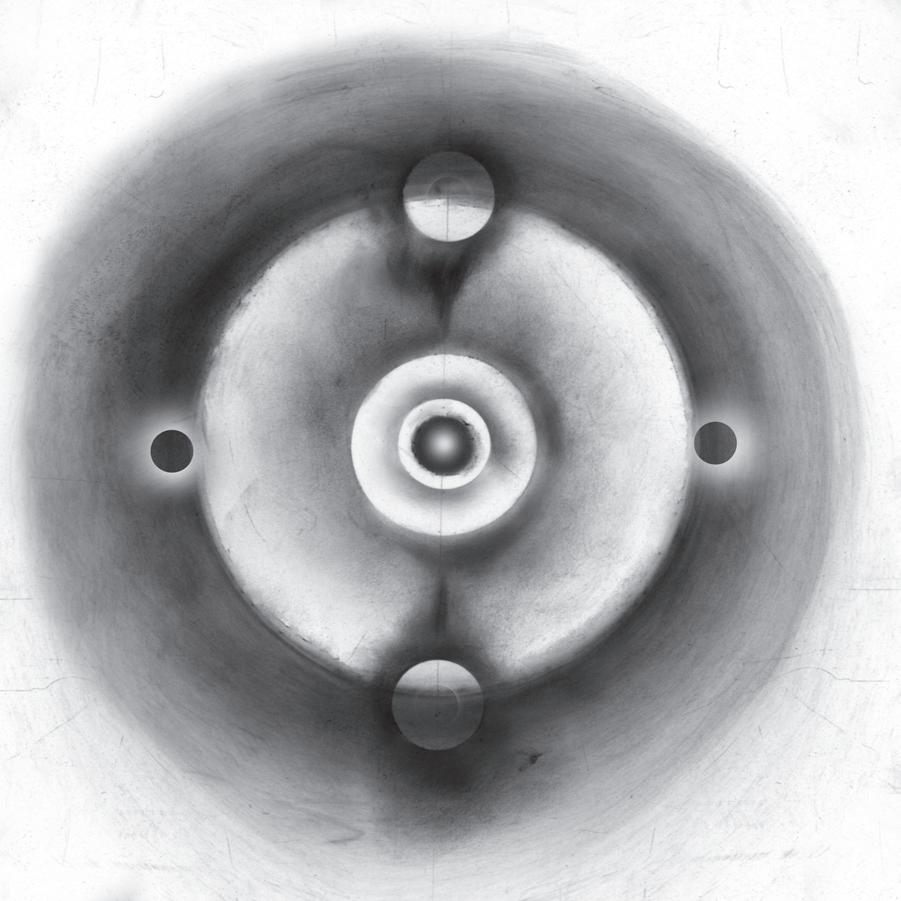

Self-portrait with eyes turned

Notes on My Strange Addiction

I had tested the immune response theory and failed. The affliction was lodged somewhere between food poisoning (it’s not food if it’s from the floor! my aunt had teased) and a stomach bug, broadly defined. Whatever the cause, I was left alternating between the austere bathroom tiling and the couch, which, at five years my senior, molded around my fetal position. Time pooled between trips to the toilet. All the while, TLC1 raged on.

Hardly able to concentrate on the lights flashing on the television before me, I almost missed it when, around hour three, my Say Yes To The Dress marathon gave way to a series of staged confessionals and interventions, with a soundtrack reminiscent of NCIS: New Orleans or Law and Order: SVU. The brainchild of Jason Bolicki,2 My Strange Addiction (MSA) exhibits masochists as they encase themselves in casts, sniff gasoline, chew dirty diapers. Undergo plastic surgery, suck their thumb, self tan. Ingest cleanser, ingest detergent, ingest cushions, ingest glass, ingest laxatives.3 Although few of the subjects endure medically diagnosable addiction,4 many struggle with a host of other disorders. (An incomplete index: Alzheimer’s disease, body dysmorphic disorder, dermatillomania, exercise bulimia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, paraphilia, pica, psychosis, schizophrenia, trichotillomania. And, of course, pure unadulterated fetish.) This catalog of unconventional afflictions extended from 2010 to 2015, though in my dehydration-induced reverie, I only viewed eight episodes, drifting between sleep and 16 sadistic stories.5 I couldn’t look away.

I was obsessed with obsession.

Each story follows roughly the same format: TITLE CARD EXPLAINING THE ‘ADDICTION’ AT HAND, talking head (stoic), close shots of our masochist in action, AD BREAK, talking head (still stoic), more action shots, AD BREAK, talking head (tearful), jarring transition music likely lifted from Dateline, talking head (professional), more jarring transition music, more action shots—this time demonstrating an intimate knowledge of the object of obsession, AD BREAK, staged intervention, TITLE CARD: WHERE ARE THEY NOW? This plot is cut and spliced against a complementary story so the entire episode rounds out to a solid 22 minutes, plus ads.6

An advantage for those inclined toward repetition: the series promises no surprises. In the 11-minute segment devoted to each antihero, the addict is introduced and re-introduced upon appearance, such that any bystander can wander into the episode without reaching for backstory. Inadvertently, perhaps, this is the most honest depiction of addiction that the show offers; addiction as an ongoing process, chronic and ever present. Applying Barthes’ hermeneutic code,7 we return nothing: MSA promises no resolution, no catharsis, no sublimation of disease. Much of the attention is devoted to cataloging the struggles of the participants, who are overwhelmingly lower-income Middle Americans. In a telling 2020 interview with Variety, TLC president Howard Lee boasted that on other networks, “a lot of people are really very West Coast/East Coast. More glamorous. And we don’t have to do that here.” Like much of the channel’s programming, the show caricatures American life. Strangeness demands an us that looks at them from a perch and attempts comprehension. Socioeconomic distance between the participants and their viewers is then essential to our complacency.8 And so, although we devour Selling Sunset (or the entirety of the Real Housewives franchise) hoping to see a glimmer of our own distress, or a confirmation that no amount of affluence could smooth the creases of life until it billows beautifully as a linen sheet hung to dry in late spring, our interest in MSA takes on a different texture. By and large, the

‘stars’ are underpaid and overexploited, remembered only (if ever)9 for their addictions.

Here, abject suffering is the point.

Of course, sadistic voyeurism is the backbone of TLC, a network, at least according to Lee, that preys on the misunderstood. “‘Please understand me’ or ‘please understand my family’: That comes across in our programming.” This plea is met not with compassion but disdain. With harsh lighting, quick cuts, and that insipid score, the program regards its participants with a combination of pity and disgust that, in my sleep-addled state, swept me in. Just as 90-Day Fiancé (melodrama), Dr. Pimple Popper (body horror), and Milf Manor (pornography) lay bare the genres of excess10 to entertain through dismay, MSA plays no pretense about our interests as viewers: we want to watch others struggle against what they want. We recall our own vices. We compare our own private shame. How vindicated we feel watching another endure that familiar trial so publicly, so ridiculously, how smug we sit assured that we know better than to sleep with a blow dryer or digest toilet paper. Watching the same sequences ad nauseum, we intrude upon another’s private obsessions without the obligation to understand. The show fixates on intimate settings, rendering the bedroom and bathroom as sites of intrigue. These behaviors are so often relegated to the private realm that they amass fear and shame, even when we understand the source. Looking (or perhaps more accurately, peering in) itself is then emphasized as the source of pleasure. Our onscreen counterparts simultaneously suffer as we suffer and suffer as we never will.

A quick detour to the realm of high art: a visit to my favorite room in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the glass-lined space that housed the Egyptian Temple of Dendur.

The room in question belonged to the since-renamed Sackler Wing, and was one of the many11 artistic and educational institutions emblazoned with the disgraced family’s name. While the moguls have long operated in the pharmaceutical advertising business, they rose to infamy during heavily-publicized trials in 2007 and 2020, which resulted in an (up to) six billion dollar national settlement for their role in the opioid crisis.

1. Formerly known as The Learning Channel. While the proper name fell away as the network overprogrammed reality television, TLC maintains that it provides “insightful programming that transports viewers into the authentic lives of real-life extraordinary characters you can learn from.”

2. Also responsible for the hit 2004 film, Twenty Gay Stereotypes Confirmed

3. Across the five years on air, My Strange Addiction remained preoccupied with consumption to no end. This proved difficult for my already compromised digestive tract.

4. Here, I suppose I’ll perform the obligatory etymological breakdown. Addiction, from the Latin addictionem: an awarding, a delivering up. In the Early Modern Period, simply, to attach. Morphs, in 17th century English, into tendency, inclination, penchant. What distinguishes the MSA afflictions from medical addiction then lies somewhere other than language.

5. In the age of binge-watching, TLC has perfected the formula, by stacking episodes of a single series back to back.

6. An entire ethnography could be devoted to the advertising potential of the concentrated audience. An unverified Comcast marketing one-sheet characterizes TLC’s viewers as 1) overwhelmingly female, 2) largely over the age of 35, 3) relatively economically well off, 4) 66 percent homeowners, and 5) often living in a household with children.

7. The major structuring principle that drives suspense in a narrative. In fact I’ve never read S/Z but once Ira Glass mentioned it as a staple in his semiotics education.

8. Vague studies produced by The Addiction Center report that addiction rates are twice as high among unemployed Americans. Careful to describe correlation, not causation, the Center notes that substance abuse often coincides with troubles performing at work and drives job loss, which compounds the cumulative cost of maintaining the habit over time. Increased insurance rates, legal bills, and medical bills are sprinkled as salt in the wound. Combined with the outstanding cost of rehabilitation and other treatments, the fiscal cocktail may be fatal.

9. Save for Trisha Paytas, Youtube celebrity and former self-tanning ‘addict’ (S1E1), who has since described her daily sunbed sitting as a choice, thank you very much.

10. Theorized by critic Linda Williams as “the spectacle of a body caught in the grip of intense sensation or emotion.”

The current opioid epidemic began in the mid-1990s, when FDA-approved OxyContin was promoted by Purdue Pharma and massively overprescribed by medical practitioners across the country, courtesy of an intense and influential “pain advocacy campaign” that encouraged “increased pain management” and misrepresented the risk of addiction. Purdue deployed a fleet of sales representatives to physicians across the country, suggesting OxyContin be prescribed not only for severe short-term pain but also for long-term conditions. The Sacklers successfully generated a widespread user base: hundreds of thousands addicted to legally-prescribed pain medication. Around 2010, the second wave of the crisis swelled as regulations made prescriptions more difficult to obtain, yet addiction treatment remained largely inaccessible. In place of institutional support, heroin increased in popularity as a cheaper, widely available, and potent alternative. The third wave followed a sharp uptick in the number of drug-related deaths resulting from fentanyl-lacing in drugs around 2013, a crisis that continues to this day. Of course, each iteration does not belong to its own temporal compartment. The strains bleed into each other, beget one another. OxyContin is the foundation of the contemporary opioid crisis in the United States, which, over every formulation, has taken approximately one million lives since 1999.12 Many victims, like my Nana or Nan Goldin, begin with a simple prescription.

11. The Sackler Educational Laboratory (American Museum of Natural History), The Sackler Center for Arts Education (Guggenheim), The Sackler Museum (Harvard), The Sackler Wing (the Louvre), The Sackler Keeper of Antiquities (Oxford—props to the name on this one),The Sackler Gallery (Washington)... Alternatively: the Sackler Institute (Columbia, Cornell, King’s College London, NYU, Tufts, Yale…)

12. Also the year that Queen Elizabeth presented Mortimer Sackler with an honorary knighthood for his contribution to the arts.

In Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, love and death share a bed. I fell in love with Goldin’s work as a catalog of exchanges. It was not just her attunement to the everyday but the vibrancy of it that won “Heart-Shaped Bruise” a pin on the corkboard above my desk in high school. In the background of suburbia, where life appeared anything but extreme, I was fascinated with the masochistic entanglement of pain and joy Goldin espoused. (Never mind her struggle with heroin addiction or the extreme poverty she photographed. Beneath her flash, the extreme was beautiful.) Her work descended into my world as an affirmation of the intensity with which I experienced every day. Every embrace mapped out a blueprint on how to live. Like any young person with too much time and not enough direction,13 I wallowed in my own vices, desires I fell at the mercy of rather than controlled.14 The object of my attention rotated but the intensity remained. Smoking, running, psychedelics, calorie counts, some girl, some guy. I worshiped each with equal fervor, assuming the position of hackneyed devotee that amateur

+++

+++

FEATS 05 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT TEXT ANABELLE JOHNSTON DESIGN ZOE RUDOLPH-LARREA ILLUSTRATION AVANEE DALMIA

turned inward, Providence

psychologists (friends with a shared affinity for Meyers-Briggs and psychoanalysis) diagnosed as an addictive personality.15 I grew solipsistic in my own afflictions, convinced that no one else survived feeling this way.

In what I would later declare as my hedonistic years,16 I relentlessly pursued transcendence. I wanted feelings to puddle in a manner antithetical to language. This want bordered on need, pulled me outside of my skin, which was exactly the intention. Although the substances rarely proved chemically addictive,17 I spent months on the cusp of revelation. Vertiginous, extraordinary. For the first time, everything was an epiphany. The jangle of keys in my hand suddenly felt as precious as the plastic gems my younger sister hoarded as a child. Meaning was made in the act. One bump and I realized I had never known what my knees felt like—not the sensation on skin but the act of inhabitance. Suddenly I wondered if I had merely subsisted on my body for so many years because it rarely demanded acknowledgement. The first time I dropped acid, I blabbed endlessly about the cycles While others touted psychedelics as tools for dismantling the boundaries erected between thoughts, mine circled the same themes like pennies down the drain. Even a simple cigarette became a cause for meditation.

Over the course of 700 photographs, The Ballad chronicles intimate scenes of love and loss, ecstasy and pain. From the relative comfort of the university, I admired the fervor with which Goldin lived and documented her life. Like MSA’s primetime audience, I was drawn to the spectacle of self-destruction. Beside me, friends descended into their own intense embodiment, yet we could not bridge the gap between our sensations. The ecosystem cannibalized itself. We were reckless, but within the bounds of acceptable delusion. Publicly, compassion was afforded to us as a function of our standing in a status system we claimed to reject but, ultimately, always benefited from. Running laps around the university track, we could grow tired of turning corners but rarely fully deviated. Those were benders, not lifestyles. This was, after all, what it meant to be young.

13. In the 1960s, Arthur Sackler made a fortune marketing the tranquilizers Librium and Valium to physicians. One targeted ad: an image of a young woman carrying textbooks, suggesting Librium “to help free her of excessive anxiety.”

14. Of the condition, Marco Roth writes, “addictions are also attitudes; at first a fact of the body, they become a perspective on the world.”

15. American Addiction Centers rejects the notion of a generic addictive personality, for those inquiring.

16. Recognizing, of course, the improbability that at 21 I set myself permanently on the straight and narrow.

17. In the kitchen, my roommates discussed the drug scheduling, on which my habits ran the range from Schedule I to Schedule V.

Concerned by my laissez-faire attitude toward my body, and thus my life, my dad sat me down with a warning. We sat side-by-side on my twin bed, facing the newly barren wall on the far end of my childhood bedroom. He wore the same faded quarter zip he did every day, with torn hemming my mom hates. I was convinced of my own intelligence in the way only newly minted young adults are. He spoke in platitudes—his family struggled with addiction to a myriad of substances, and he didn’t want to see me wander down the same path. I shrugged him off. I was in control of the situation. I rejected the notion there even was a Situation. Mostly, I liked leaving parties but didn’t like going home.

My dad turned toward pathos. A couple years after I was born, my grandmother recovered from knee surgery, alone, in a townhouse across the country. As I took my first steps, she remained largely immobile from the pain. Her doctor prescribed her OxyContin.

I never knew my Nana before her surgery. I do know that in her Western Pennsylvania high school, she was the swim team secretary. That she moved with my father’s father to Dallas, Texas, where he was stationed, and then to Los Angeles the following year in the wake of their divorce. Once, after my father disappeared for a day with a band of older boys, she chased him through the streets of El Monte with a wooden

spoon. When he was young, she cleaned their apartment complex to make rent and after finishing her associate degree, always organized the holiday office party. Later, when she moved to Monterey, she ornamented her desk with bobble-head Dodgers players. She smoked Marlboro Golds and drank Diet Coke, enjoyed true crime and mildly-true gossip. She never raised her voice and kept the fridge stocked with egg salad and laughed like the fry of a boombox out the window—the sound simply escaped her. I know that OxyContin stole her time, body, and confidence, and even as she thumbed through People magazine in the daylight or snuck us chocolate frosted Entenmann's donuts at night, she was mourning, always, for herself.

Losing her was gradual, my dad cautioned. It wasn’t her fault but it happened a little bit every day. I nodded and blew smoke out my window as soon as he left.

+++

Having lost loved ones to AIDS and years of her life to opiods, Goldin published “Crushing Oxy on My Bed, Berlin, 2015.” A blurry pill box, with its faded lettering, holds small white tablets. Behind it sits a circular slab, dusted in OxyContin. Nan Goldin’s photograph, like her seminal works of 1980s bohemia, indulges few charades. Laid bare is the truth of addiction. Sullen afternoons sacrificed to the twin anvils of agony and numbness. I behold Goldin’s photographs and flinch. “Dope on My Rug, New York, 2016” presents an overhead menagerie of lighters, pill bottles, cigarettes,18 and that purplecapped Sharpie that no matter the lighting, always produces a line much closer to brown. The collection is damning and devoid of subject. Somehow both entirely of Goldin and completely beyond. I was struck by how intensely she presents objects as action. Spelled out on the floor, the doing is implied.

Goldin started taking OxyContin in 2014 to help alleviate wrist pain. “I was originally prescribed for surgery. Though I took it as directed I got addicted overnight,” she writes for ArtForum. After maxing out on her prescription,

06 FEATS

+++

VOLUME 46 ISSUE 09

Goldin turned to heroin, and, in 2017, nearly overdosed from a mixture of heroin and fentanyl. She went to rehab. She published her personal photographs. She recognized her struggle as a part of a larger legacy of overprescription. On March 10, 2018, Nan Goldin forced the Met to acknowledge its inheritance. With her newly formed Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (P.A.I.N.),19 Goldin staged a die-in, launching hundreds of pill bottles into the reflecting pool beneath the temple. The water was freckled with labels that read “Prescribed to you by the Sackler Family.” One protestor bore a sign with the ACT UP logo, SILENCE = DEATH. The art world, previously content with the public distinction between Purdue Pharma and its board, was forced into acknowledgement. In December 2021, the Met dropped the Sackler name and refused further donation. Of the decision they wrote, “The Museum and the families of Dr. Mortimer Sackler and Dr. Raymond Sackler have mutually agreed to take this action to allow The Met to further its core mission.”

In Laura Poitras’ 2022 documentary All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, Goldin draws a parallel between the AIDS and opioid epidemics. Both are instances of government oversight and social stigma further isolating those who are suffering. In both instances, Goldin leveraged her own life not to shock but to move. Aware of our scopophilic tendencies, Goldin portrays suffering against want. Look at this, she demands. Watch me bare my pain for you. At a loss for words, I borrow Sontag’s, regarding the pain of others. “No moral charge attaches to the representation of these cruelties. Just the provocation: can you look at this? There is the satisfaction of being able to look at the image without flinching. There is the pleasure of flinching.”

18.

19.

narrowly escaped. I went from the darkness and ran full speed into The World. I was isolated, but I realized I wasn’t alone.”

There is little to say about my Nana’s recovery. It was painful, and harrowing, and entirely incomplete. Her body transformed beyond her comprehension and she retreated from it until her skin, too, was as foreign as her needs. Sat before the television, I spent many afternoons combing her hair, thin and soft in my palms. We watched cop dramas abound with terrible things happening to young women. She scratched my back as I drifted off and I still sleep best with someone tracing figure eights around my spine. Addiction is not spectacular or disgusting or shameful or romantic. It just is, over and over and over again.

+++

These days, I am studying the pursuit of pleasure and routine deviations from the course.20 Case study: “Eats Toilet Paper/Blow Dryer.”

“I’m absolutely addicted to sleeping with my blow dryer,” Lori confesses at the start of the episode. If not dire, her situation is bleak. Cleanly packaged in a 40-second montage: Lori tucked in with her blow dryer before bed, Lori cuddling her daughter below the heat, Lori blowing hot air at her toes. The experts are called in, a therapist delivers the radical wisdom that “people often try to soothe themselves.” Her friends worry about the burns on her arms. Her ex-husband admits the blow dryer is in part responsible for their divorce. Her three-year-old curls up beside the hot air before bed, and a halfhearted gesture is made toward the dangers of impressionable youth. In turn, Lori wanders the aisles of a dimly lit beauty store to demonstrate expertise. She points to various boxed blow dryers under the auspice of purchase, but money never changes hands.21 All this backstory is established in four minutes. The remaining seven will repeat these scenes, gloating over her suffering.

Cut to: Kesha, who began eating toilet paper when she moved in with her grandmother and auntie in sixth grade. Here, the psychiatrist notes that girls at this age need to be nurtured through

the process of self-development. If nothing else, the statement establishes the caliber of the medical advice Kesha will receive. After a commercial break, she sits through a staged confrontation. “I’m going to meet Jennifer. She’s trying to convince me to stop eating toilet paper so I’ll see how it goes,” Kesha explains outside the diner. Inside, the pleasantries are elided. The pair sits at a grisly booth, a mountain of breakfast food between them. “Did you know you’ve been eating toilet tissue for 23 years? You never thought about it?” demands her sister. In between bits of corned beef hash, Kesha tears herself a square of toilet paper.

TLC uploaded the episode to YouTube in full, as a part of a series of clickbait titles: “What Happens When You Eat 8 Beds?,” “Addicted To Ventriloquism/Cats,” “Sex with a Car,”22 “Glow In The Dark Boobs,” “Addicted to Being Together,” “Hairless Rat Love”… The virtual museum of curiosities posits human beings as specimens, and I move from exhibit to exhibit in a haze. Each scene assuages my fear of addiction-as-concept: look at this freakshow, the program demands. How unserious this dependency beyond chemical. In every story, suspense is developed through increasingly heavy percussion and erratic editing. Scenes are so obviously choreographed yet leave elliptic plot holes.23 There is no gesture toward treatment. On-screen family members express concern, in the hollowest sense of the term. Everyone is fixated on identification, as if patterns once named suddenly grow afraid of their semantic shadow. As if the apathetic rhythms of MSA fall out of time when we understand the origin. Our sadistic impulses become a study in our own indifference. After all, what distinguishes one form of compulsive self harm from another? Perhaps it is only social reinforcement that stands between me and the funhouse of obsession depicted in MSA. The distinction lies not in the action but the gaze. I watch Kesha’s nearly tearful admission, “She doesn’t understand that I’ve tried and I can’t stop,” and recall the rhetoric of addiction. With its intent on blame, the language often obfuscates the fundamental battle, that internal wrestling with yourself. You are the aggressor and the victim, take the knockout shot and fall bloody in the ring. There is predisposition: genetic inheritance, socioeconomic conditions. There is inevitability: chemical processes, daily desires. And then, there is you.

20. Apropos of Barthes, “No object is in a constant relationship with pleasure (Lacan, apropos of Sade).”

21. At least, this is the only rationale I can offer for this scene. Lori’s insider knowledge is in fact largely intuitive, even for those of us who neglect to sleep beneath a constant stream of hot air—I, myself, keep my window open in all seasons—but for those unfamiliar: it is best to sleep with a blow dryer with multiple heat and power settings, so claims the expert.

22. On the subject of obsession and the myopic worldbuilding of David Cronenberg’s Crash, a girl in my film class lamented that such fidelity to any object is inherently isolating. I tried to counteroffer evangelical church or at least a sweaty mosh pit but the conversation was quickly derailed by a personal anecdote about the first time our classmate viewed porn. (“I just kept thinking, this couldn’t be right.”)

23. "With the help of meditation, Lori has overcome her addiction. She still craves her blow dryer and admits to using it sometimes during the day,” proclaims a title card at the end of the episode. Meanwhile, Kesha is “fighting her addiction.”

End scene.

It boils down to control, having and losing, living with and without. Nowadays, I fear most drugs because they return me to my body and remind me that I’m the only one in there. I am in the process of unraveling myself from my obsessions. In the most fundamental sense, I remain the same. I retain the frightening immediacy of addiction, inhabiting each moment with the plea: let this be the last and only thing that matters to me. But the days pass different. When I wake up the sun is still fixed along the horizon and I am no longer a liability to love. Television bores instead of assuages. My Strange Addiction returns to my life as a one-off in a Maggie Millner poem. “There was no joy depicted—just decrepitude, abjection, musty rooms.” I mop my floor. I let my hair air-dry, except in February. I take up poetry and have less to apologize for. While on the phone with my dad, I watch the mechanical arm of a forest-green garbage truck extend into the street to lift waste into its impossible stomach. He updates me on our dog’s digestive health and the most recent episodes of This American Life; I describe the collection route. The truck lingers at every house on my block to take the trash in heaps without complaint. It stops. It starts. It is dirty and it is cleaning and it keeps driving.

ANABELLE JOHNSTON B’23 just is.

+++

+++

FEATS 07 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT TEXT ANABELLE JOHNSTON DESIGN ZOE RUDOLPH-LARREA ILLUSTRATION AVANEE DALMIA

Like Joni Mitchell, it seems Goldin smokes Yellow Spirits.

Announcing her group, Goldin writes, “I survived the opioid crisis. I

“FIFTEEN BUCKS IS NOT ENOUGH”

Interviews from the RISD picket line

These interviews were edited for length and clarity. Colorful posters adorn the bricks of the Providence Washington Building, better known as Prov-Wash. It’s a hub for RISD students, but more importantly, it houses the office of RISD President Crystal Williams. That’s why, this afternoon, more than 100 RISD community members are picketing outside.

“Fifteen bucks is not enough” and “honk your horns for worker’s rights” echo from a megaphone. Students bang on improvised instruments, beating empty buckets and milk crates with sticks. Musicians have armed themselves with cymbals, drums, and beat-up amplifiers, while sculpture majors bang sheets of scrap metal. Thankfully, a jar of earplugs sits among shared supplies, along with water bottles, energy bars, and an impromptu button-making station. Strikers are proudly adorned with pins reading “UNION STRONG” and “SUPPORT 251 LOCAL.”

The RISD Teamsters (short for the International Brotherhood of Teamsters) stand tall with signs hanging off their shoulders. Across the street, students are printing more graphics to add to the collage. Perhaps the most arresting object—a two-story-tall inflatable pig—stares into the offices of school administrators from its perch on a large flatbed truck.

After drawing the support of students, faculty, and local politicians, the union reached an agreement with RISD on April 18, ending the strike. The following interviews, conducted with picketers on April 7, illustrate the feelings of frustration and solidarity that brought a community together. +++

Interview with anonymous picketing RISD student

The College Hill Independent: What made you decide to join the picket line?

Student: These people are working their asses off every single day, they love their jobs too, just wonderful human beings. I was talking to this one guy, he’s been working here for 20 years, and he gets paid like $19.50 [an hour]. It’s ridiculous that Crystal Williams is being paid $600k [a year]. That’s fucking disgraceful. I don’t know. I’m pissed off!

Indy: What do you see for the future of the strike?

Student: A ton of work. Because we’re going to fuck their shit up. We’re going to make their pockets hurt. We are organizing, we’re getting better at organizing.

Indy: Do you have a message for the RISD administration?

Student: Yeah, fuck you!

Indy: Do you have a message for the custodial and dining staff?

Student: We love you so much. You are supporting us every single day, and you get treated like shit, and it’s bullshit. We are on your side.

+++

The union of RISD’s custodians, movers, and groundskeepers started negotiating a contract with the school’s administration on June 13, 2022. Organizers sought to boost salaries, which were as low as $15.25 an hour, to at least $20. According to Teamster leadership, the union was ready to strike last year, but were advised to wait until February’s negotiations. After months of talks, though, RISD had barely budged. When the administration remained obdurate even with a federal mediator present, the union planned a strike. It started slowly: students received vague email updates from the school, while workers stood in front of buildings with flyers and signs. Once negotiations continued to stall and the strike shifted to “indefinite,” students sprang into action. Most departments took it upon themselves to handle their own cleaning. The architecture department, though, took the trash produced by student projects and filled their lobby with it, in a show of solidarity.

+++

Interview with anonymous striking RISD worker

Indy: What made you decide to strike?

Worker: The school, they never give a cent. No offers, anything. We try, you know—yesterday, we met with the school, the union, and it was the same thing.

Indy: What do you see for the future of the strike?

Worker: I think the guys did a very good job, the students did a very good job. But yesterday, when we [were] at the table, talking about all this, the one speaking for the school said, “The students [are] not good. The only thing they do is printing and photography. Nothing else.” I was getting so mad. The guy was sitting next to me. I was just so mad, I want[ed] to yell. When they talk about the students like that, I get mad.

Indy: Do you have a message for the administration?

Worker: Just give us a raise. That’s it. We just need a raise. Give us a raise, we come back to work tomorrow.

Indy: Do you have a message for your fellow workers? And your staff?

Worker: Well, I keep telling them, don’t give up. Be strong. We’re going to win this. We are family. Together, nobody stops us. We have to be strong. To the end. +++

On April 6, amid mounting fervor, RISD and the Teamsters met once more to negotiate, but RISD sent just one person—Director of Labor Relations Michael Fitzpatrick Jr.—to the table. Fitzpatrick Jr. dismissed student efforts and continued to deny the union’s requests, according to Teamsters present.

The news got out. Frustration snowballed into action, including a faculty walk-out, departmental statements of support, and an April 10 letter from the Providence City Council expressing solidarity with the union. +++

Indy: What made you decide to join the picket line?

Student: It was the emails that the administration kept sending, saying that the union was being unfair and unreasonable, which was a lie. Just talking to the workers and seeing the general environment, it just didn’t make sense.

Indy: And the fact that they haven’t been negotiating with the union.

Student: No, they haven’t. They’re basically just lying. At first I just kind of chalked it up to corporate talk, but after talking with the Teamster people, and just talking to more people, it’s like no, they’re just fucking lying.

Indy: Do you have a message for the administration?

Student: Go fuck yourself.

Indy: Do you have a message for the workers?

Student: You guys are doing great, you guys are heroes, you guys can do this. The student body stands behind you. You have our full support.

+++

RISD students organized a rally on April 14, with hundreds of RISD community members in attendance. Students marched around campus hanging up posters and blaring every kind of noise-maker an art student could imagine, wearing red and white to show support.

On Monday, April 17, RISD met for the last time with union leadership. Organizers said that the administration was eager to end the strike, and had a lawyer on the phone during the meeting. The next day, union members met at the Teamsters’ hall in East Providence to vote on the contract. Organizers went through the new contract proposal point by point, translating in Spanish and Portuguese. Custodians, movers, and groundskeepers would make at least $20 if they’d worked at RISD for more than one year. Their vote to support the new contract was unanimous, and the strike was over.

+++

Interview with anonymous professor making posters with their class outside Prov-Wash

Indy: What made you decide to strike? Or be involved with the strike?

Professor: Well, technically we’re having class. This is the silkscreen workshop in graphic design. This is our third week out of four. This is our class—a very regular class.

Indy: You have no obligation to answer this question, but I heard RISD professors are banned from striking, is that correct?

Professor: In the part-time faculty union contract, we are banned from sympathy striking, so we are teaching class today.

Indy: What do you see for the future of the strike?

Professor: I have no idea. I just hope it gets resolved, and I hope they come back to negotiate.

Indy: Do you have a message for the workers?

Professor: I graduated [from RISD] in 2010, and just remember everyone being so nice and taking care of us, so I really want to be out here showing support, and trying to take care of them.

LI DING R’26 will continue to scrutinize RISD’s financial priorities.

SARAH MANN MID’26 will continue facilitating difficult conversations.

08 LIT

Interview with anonymous picketing RISD student

TEXT LI DING &

DESIGN GINA KANG ILLUSTRATION MICHELLE DING VOLUME 46 ISSUE 09

SARAH MANN

SINKING TOO DEEP INTO THE ROLE OF THE ARTIST-PERFORMER Everyone look at me. I am doing something beautiful.

09 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT X

Joshua Koolik B’24

Ballet Recital (flipbook) Stills from video documentation of my performance: ‘Ballet Recital’ [15:38]

eighty-inch TV astrology books

swampy couch security cameras

’80s computers exposed wiring

A Small House in

Items from my grandfather’s house

My dad tells my older brother and me that if we get hit, we hit back harder. We practice punching the palm of his hand in the kitchen after dinner. Jab jab, cross. Jab jab, cross. He says nice one every time I punch with my left fist. I tell everyone at school I punch harder with my left.

On Sunday mornings, we iron our clothes while my dad finishes writing his sermon. He has a way with words, and maybe a way with God. After service, people line up at the altar to talk to him. Sometimes they tell him he changed their life. Sometimes they tell him he’s a genius. I wait patiently in the front pew, flipping through old hymnals. Sometimes they tell me how lucky I am, that my father is such a godly man. I agree; I feel lucky.

my fourth-grade hands fashion a rope for delicate sprout

corduroy recliner

canned vegetables

gas fireplace

After church, my dad races eighty miles an hour through the backroads on our way home. My brother and I laugh with adrenaline. My dad puts on “Wake Up” by Arcade Fire, turns the volume up so much my ears start to sting, tells us to listen to the words and look out the window. I watch the telephone cable ripple between poles, the sun flash behind the trees. I like how it feels, to feel things I can’t name.

how can light start to bloom in sanctuaries where shadows angle so violently on children’s bare, pink skin

wood paneling

diet root beer

Nick’s pizza

When it’s unbearably hot, my dad takes my brother and me to Adventure Highway, an abandoned road on the side of Neversink Mountain. The asphalt is cracked all the way down the middle, the pavement glowing with graffiti cuss words and dicks. We walk for hours along the road as my dad tells us lurid stories from his childhood. I find the stories hard to believe, but they’re too tempting not to.

words come out green and flutter in my stomach, leaves me with a dull nausea or else a sharp pain I drown out in motion sickness

landscape paintings

fluorescent kitchen light

dark dining room table

On winter holidays we go to my great aunt’s house. My dad and his brothers sit in a circle of folding chairs in the dimly lit living room, playing guitar and banjo and singing about God and Appalachian coal. They harmonize from their chests effortlessly, with the same vocal cords, the same body, till they’re all red and sweaty. I stand by the kitchen doorway and watch. My dad asks me to sing with him, but I’m too shy.

pieces of lyrics you sang to me hang in trees by my bedroom window, limp in the night wind translucent and blue as I sleep, cradling myself behind glass

creaky stairs

old American smell photos of you on your motorcycle

My dad tells my brother to be careful around theater boys. My brother auditions for the middle school play without telling anyone and gets the big part. My dad doesn’t say anything. He shows us a video of a man playing the same part, how feminine he’s acting. My dad asks my brother if this is who he wants to be. My brother says no and runs upstairs. I laugh at the video.

I wake up with stones in my hands, my window freshly stained. I embrace the glass figures and they shatter in every color

dead grass

half a dozen brokendown cars

rotted treehouse

My dad has always loved the idea of going to an Ivy League school. He likes Princeton the best. He would take me and tell me to pretend I was a student as I wandered the campus, to see what it felt like. He loved telling me about the time he was there while they were shooting A Beautiful Mind, and Jennifer Connelly checked him out. Now he loves telling people he’s an Ivy League Dad.

the shards gather to an omen, a headstone, a memory I can’t properly trace my steps back to

box fan on the patio

red tinted glasses

button-up shirt and jeans

My dad started working out a lot since I left. His stomach contracts, his arms grow. My brother jokes he’s going through his midlife crisis. When I call him, he asks me if I’ve been working out. I don’t say much but tell him he looks younger. When I hang up, I suddenly feel out of place in my own dorm room. I take out a book and do class readings at my desk until the feeling goes away.

empty cigarette tins

Holy Bible

leather belt

Every other week or so, a book about Jesus comes in the mail. I keep them in a drawer I feel guilty everytime I open. One night, alone in my dorm room, I can’t take it; I pick one out at random and read half a chapter, my eyes dry as a breeze blows in. For a moment, some pointed hunger in my body feels quiet. I watch a tree quiver in the wind and close the book. I feel beautiful and inadequate. I turn off the lights and sleep by the open window.

I run my hand through your hair one more time, thick and greasy, before we duck our heads trains run past us in gray; I dip my hand in the mud, held in the noise, smear my chest and cast it across

10 LIT South Jersey

EVAN DONNACHIE B’24 really likes the stromboli from Nick’s Pizza.

TEXT EVAN DONNACHIE DESIGN SAM STEWART ILLUSTRATION NICHOLAS EDWARDS

VOLUME 46 ISSUE 09

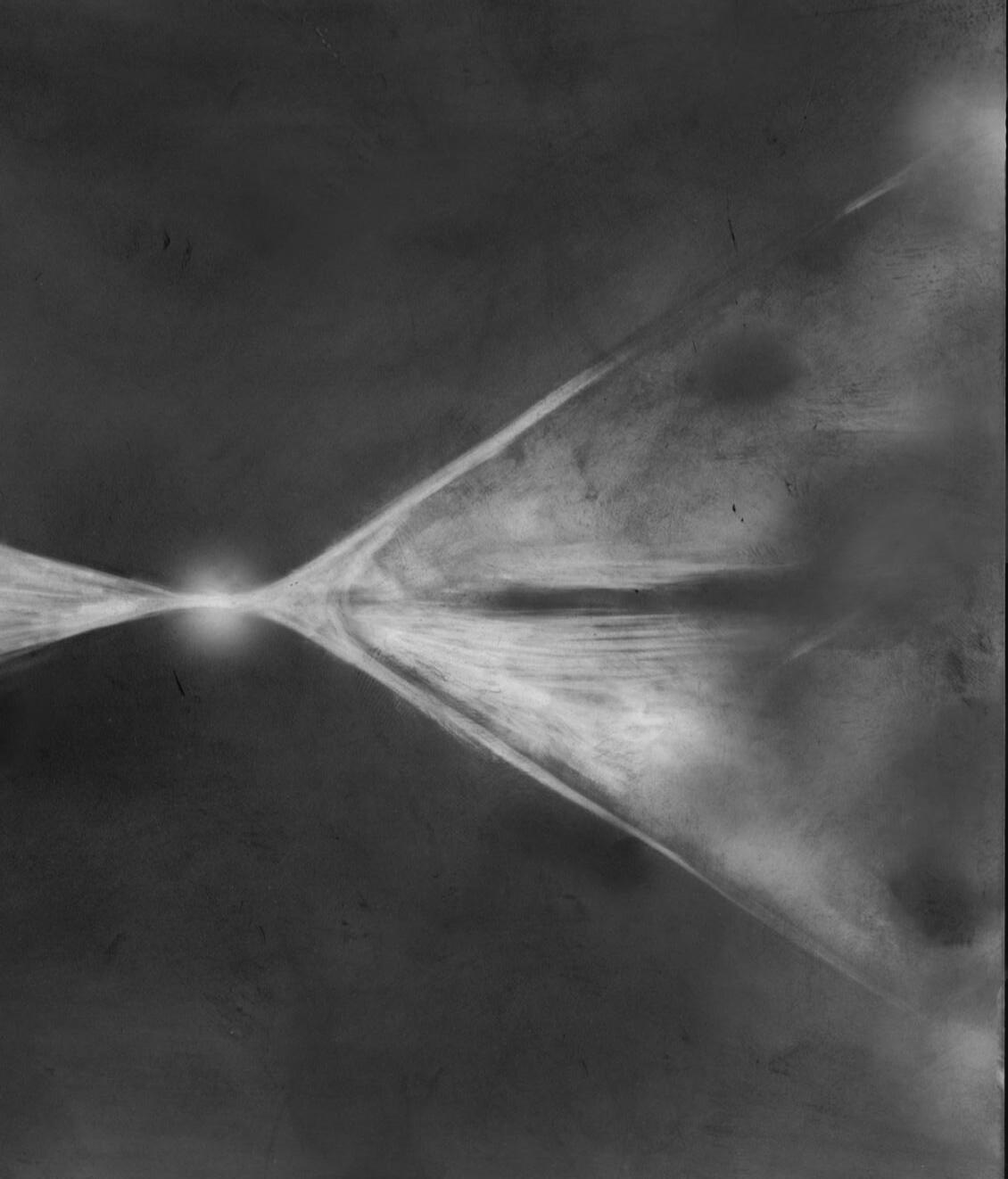

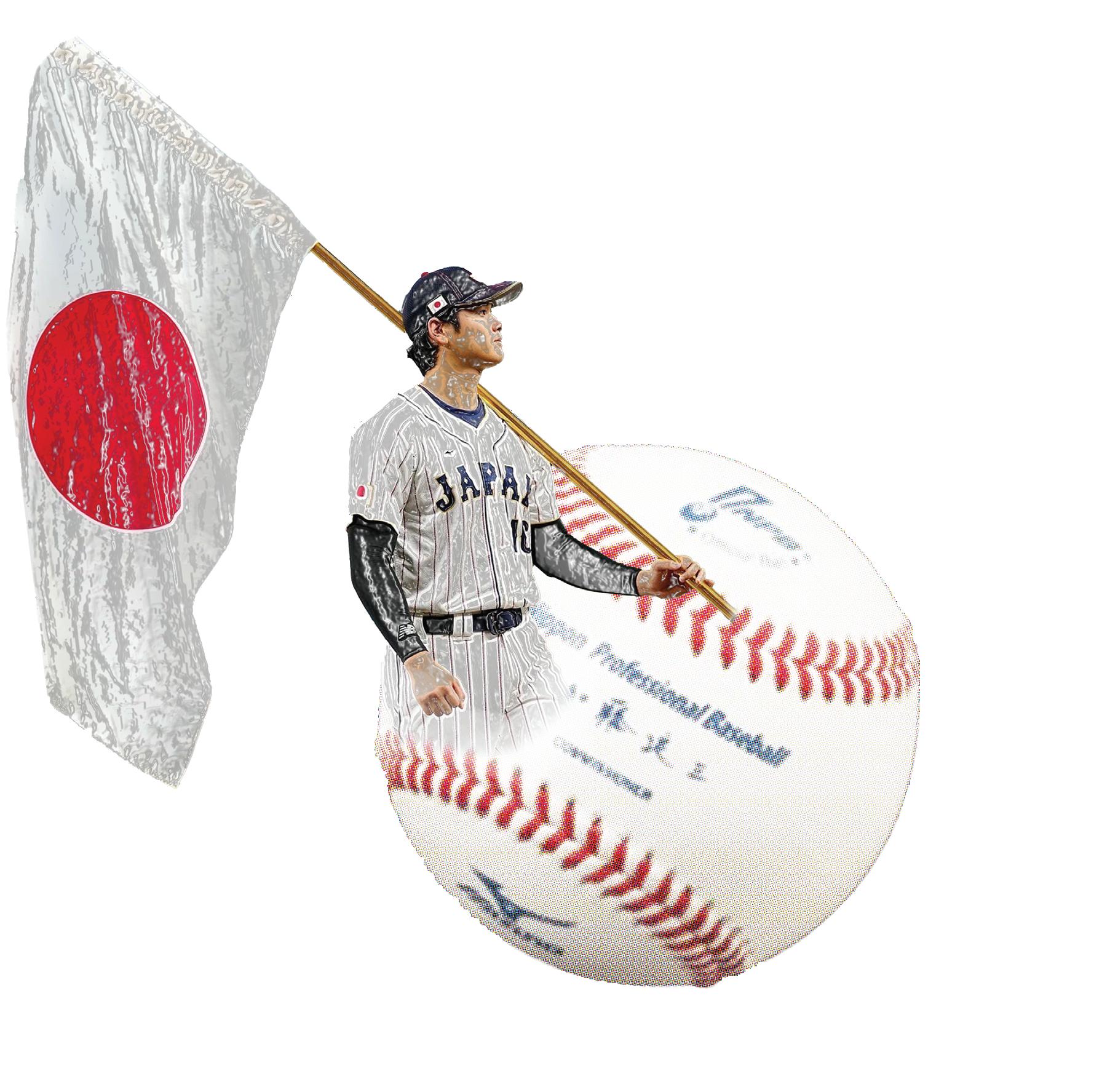

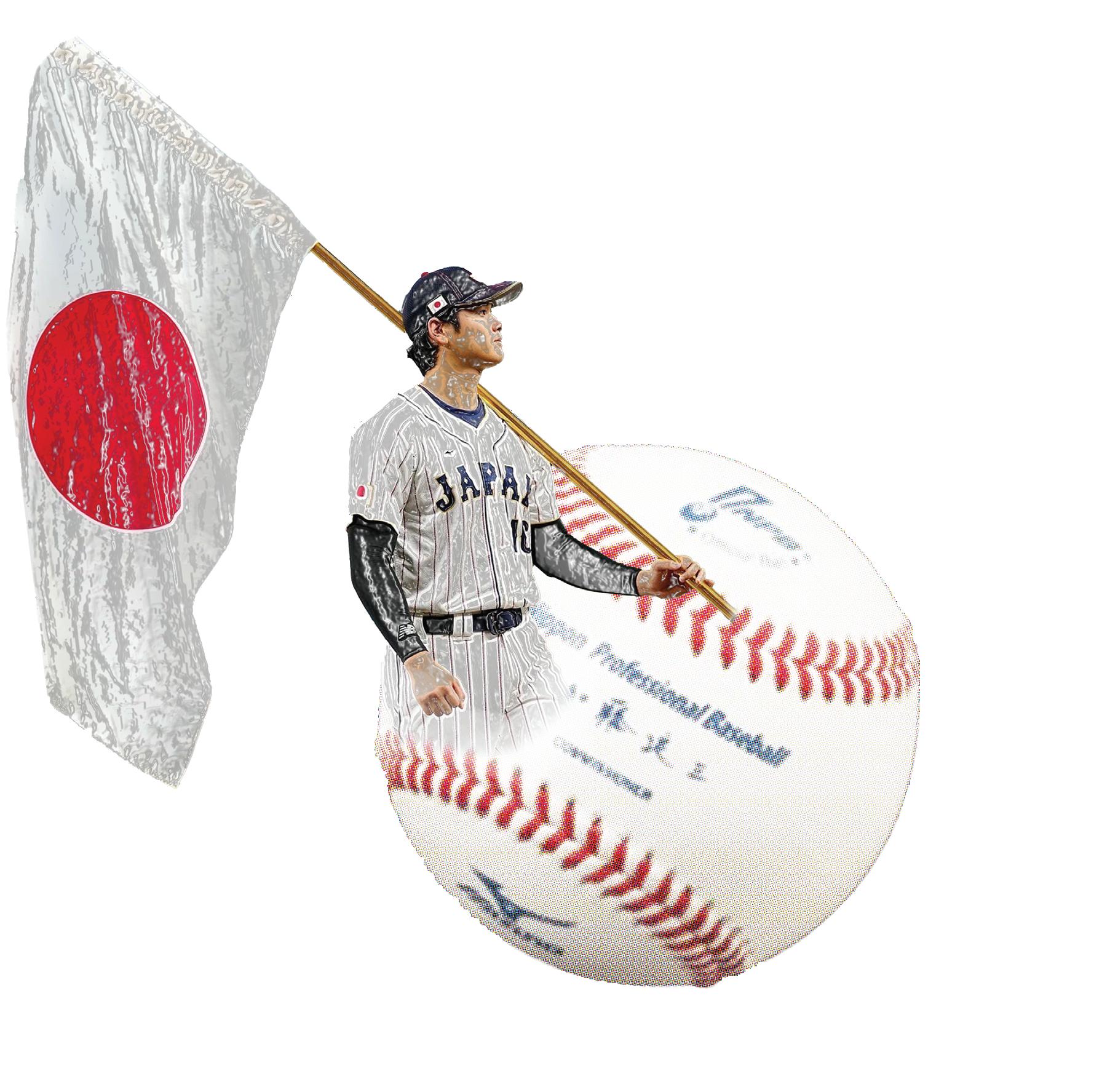

60 FEET, 6,000

Imperialism at the World

into the ‘future’ by encouraging the uptake of Western influences, also drove the adoption of this U.S.-born sport.

by a crack of

The world sits on edge as Michael Nelson Trout, the 31-year-old center fielder from Vineland, New Jersey, walks slowly to the batter’s box. He swings his bat once, twice, feeling its weight in his hands. He nods to himself, smacks his gum, and takes a deep breath. Having settled into the moment, as he’s done thousands of times before, Trout looks forward—60 feet and six inches forward—into the eyes of his transitory foe. On the pitcher’s mound stands Shohei Ohtani, the 28-year-old do-it-all unicorn from Ōshū, Japan. This inning, Ohtani had walked the first batter before forcing the next into a double play, bringing up Mike Trout with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning of the final game of the 2023 World Baseball Classic. This at bat will have a near-deciding impact on the outcome of this premier global sporting event. If Ohtani wins this matchup, then Japan takes home the trophy. But if Trout reigns victorious, the USA has a fighting chance against its longtime rival. From the press box high above loanDepot Park in Miami, Florida, sportscaster Joe Davis speaks to the six million tuned in around the world: “And now… theater. Impossible theater.”

The World Baseball Classic is an international baseball tournament, held every four years since 2006 (baseball was removed as an Olympic sport in 2005). The tournament was the brainchild of Major League Baseball (MLB) and the MLB players’ union, and was modeled after soccer’s World Cup. The tournament has garnered international adoration over its four previous installments. Representing one’s nation often elicits intense emotions of honor and allegiance—both for players and their devoted fans. In many East Asian and Central and South American countries, this tournament is considered the nation’s most popular sporting event, akin to Canadian ice hockey or Brazilian soccer.

Of course, it wasn’t solely homeland pride that drew eyes to this matchup: many simply wanted to witness two of the greatest baseball players of all time face off. Trout is one of the most feared hitters in baseball history, and has been near or at the top of almost every statistical ranking since entering the league in 2011, winning American League MVP three times. Meanwhile, Ohtani can pitch and hit with the best of them—a Babe Ruth analog who might just do everything better than The Babe.

These two gods of the sport have also, incredibly, found themselves on the same MLB team. When this tournament is over, they will return to sunny Los Angeles, California, to play for the somehow perpetually middling LA Angels. For now, though, they stand confidently on opposite sides of the infield, adorned with the colors of their countries. Behind Trout’s shoulder, someone in the crowd lifts the stars and stripes; on his left, a group boasts the Hinomaru, the Rising Sun Flag. Both players, in this heavy-weighted moment, seem remarkably poised.

But a complex history floats over the moment, weaves its way through the crowd, follows the path of the five ounce red-striped ball as it zips back and forth between pitcher

this awe-inspiring showdown between two of the greatest to ever play the game. Ohtani nods at his catcher, lifts his left leg to his chest, reaches his right arm way, way back, and fires.

+++

The telling of baseball’s origin story has its own contested history. Many theories as to the timing, location, and credit for the game’s invention have circled the U.S., the most famous being the Abner Doubleday theory. In 1905, the famed baseball player and executive Albert Spalding brought seven of baseball’s earliest officials together to establish the Mills Commission, tasked with investigating the origins of the sport. The group eventually determined that Doubleday, later a Union general in the Civil War, wrote the rules of the game in Cooperstown, New York in 1839.

Here’s the catch: the general was likely not in Cooperstown this year, if he ever visited this town at all. There is, in fact, a preponderance of evidence directly refuting the Doubleday theory; critics began publishing rebuttals as soon as a year after the claim was made. But the damage had been done, and the theory’s intensely patriotic undertones carried it to prominence (the Baseball Hall of Fame has been the main draw of Cooperstown since its founding there in 1936).

On the Mills Commission sat seven men, two of whom were U.S. senators, all of whom had reason to desire baseball to be an all-American ballgame, invented in a small rural town by the man who fired the first shot of the Civil War. In all likelihood, the sport is a derivative of European historical ball games related to rounders and cricket (much to the dismay of the blue-blooded patriots of the time; at the aforementioned dinner, clinks of forks and knives were often drowned out by chants of “No rounders! No rounders!”).

Regardless of the specifics of its invention, baseball was undeniably one of the most important sports in the early United States. Baseball clubs formed across the 1840s, and it was in the following decade, even before the creation of professional teams, that baseball earned the moniker of “national pastime.” The nation’s devotion to this sport, however, was soon to be matched, if not overtaken, by a peer country across the globe.

The rise of baseball in Japan has a much clearer history than in the sport’s home country. Baseball was introduced by Horace Wilson, a professor of English at Kaisei Gakko (now Tokyo University) in 1872. American missionaries and teachers were responsible for its growth in popularity over the next few years, aided in large part by the boom in global mail and telegraph communication capacity. The Meiji-era Westernization movement, in which the Japanese government sought to steer the country

Even as the Meiji regime attempted to ‘Westernize’ the nation, it still placed importance on the maintenance of Japanese identity. Baseball was thus intentionally linked to the idea of Bushido, the code of ethics of the samurai. Bushido takes influence from Confucianism, Buddhism, and Shinto, and is imbued with a deep nationalist pride.

Unlike in America, baseball was popularized in Japan primarily through youth leagues. Throughout the early 20th century, high school, college, and university games drew enormous crowds and continue to today; the annual Summer Koshien high-school tournament draws teams from each of Japan’s prefectures and is nationally televised. Baseball training is considered an integral part of a Japanese high-schooler’s education: it is at once a physical, emotional, and spiritual exercise. High schools across the country are revered for their strong baseball teams and player commitment decisions are considered with the same vigilance as college decisions in the U.S.

In 1936, the Japanese Baseball League, the first professional league in the country, was established. The Tokyo Kyojin (now Yomiuri Giants) and The Osaka Tigers, the two oldest professional teams in Japan, were dominant in this early league. These two teams had split 11 straight championships (7–4 respectfully) until the league was forced to shut down for the 1945 season as the country turned its focus toward war.

Over the previous several decades, the nationalist pride so strongly connected with baseball’s rise in Japan had been marshaled toward the nation’s own violent, imperial project—culminating in its eventual alliance with Nazi forces during World War II.

+++

The first pitch of the at bat, an 88-mph slider, swings just low of the strike zone for a ball. As each player gets reset in body and mind, Joe Davis comments on the tournament’s global appeal: no matter the outcome of this at bat, “Baseball’s already won.”